The Guide to Thematic Analysis

- What is Thematic Analysis?

- Advantages of Thematic Analysis

- Disadvantages of Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Analysis Examples

- How to Do Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Coding

- Collaborative Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Analysis Software

- Thematic Analysis in Mixed Methods Approach

- Abductive Thematic Analysis

- Deductive Thematic Analysis

- Inductive Thematic Analysis

- Reflexive Thematic Analysis

- Thematic Analysis in Observations

- Thematic Analysis in Surveys

- Thematic Analysis for Interviews

- Thematic Analysis for Focus Groups

- Thematic Analysis for Case Studies

- Thematic Analysis of Secondary Data

- Introduction

What is a thematic literature review?

Advantages of a thematic literature review, structuring and writing a thematic literature review.

- Thematic Analysis vs. Phenomenology

- Thematic vs. Content Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Grounded Theory

- Thematic Analysis vs. Narrative Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Discourse Analysis

- Thematic Analysis vs. Framework Analysis

- Thematic Analysis in Social Work

- Thematic Analysis in Psychology

- Thematic Analysis in Educational Research

- Thematic Analysis in UX Research

- How to Present Thematic Analysis Results

- Increasing Rigor in Thematic Analysis

- Peer Review in Thematic Analysis

Thematic Analysis Literature Review

A thematic literature review serves as a critical tool for synthesizing research findings within a specific subject area. By categorizing existing literature into themes, this method offers a structured approach to identify and analyze patterns and trends across studies. The primary goal is to provide a clear and concise overview that aids scholars and practitioners in understanding the key discussions and developments within a field. Unlike traditional literature reviews , which may adopt a chronological approach or focus on individual studies, a thematic literature review emphasizes the aggregation of findings through key themes and thematic connections. This introduction sets the stage for a detailed examination of what constitutes a thematic literature review, its benefits, and guidance on effectively structuring and writing one.

A thematic literature review methodically organizes and examines a body of literature by identifying, analyzing, and reporting themes found within texts such as journal articles, conference proceedings, dissertations, and other forms of academic writing. While a particular journal article may offer some specific insight, a synthesis of knowledge through a literature review can provide a comprehensive overview of theories across relevant sources in a particular field.

Unlike other review types that might organize literature chronologically or by methodology , a thematic review focuses on recurring themes or patterns across a collection of works. This approach enables researchers to draw together previous research to synthesize findings from different research contexts and methodologies, highlighting the overarching trends and insights within a field.

At its core, a thematic approach to a literature review research project involves several key steps. Initially, it requires the comprehensive collection of relevant literature that aligns with the review's research question or objectives. Following this, the process entails a meticulous analysis of the texts to identify common themes that emerge across the studies. These themes are not pre-defined but are discovered through a careful reading and synthesis of the literature.

The thematic analysis process is iterative, often involving the refinement of themes as the review progresses. It allows for the integration of a broad range of literature, facilitating a multidimensional understanding of the research topic. By organizing literature thematically, the review illuminates how various studies contribute to each theme, providing insights into the depth and breadth of research in the area.

A thematic literature review thus serves as a foundational element in research, offering a nuanced and comprehensive perspective on a topic. It not only aids in identifying gaps in the existing literature but also guides future research directions by underscoring areas that warrant further investigation. Ultimately, a thematic literature review empowers researchers to construct a coherent narrative that weaves together disparate studies into a unified analysis.

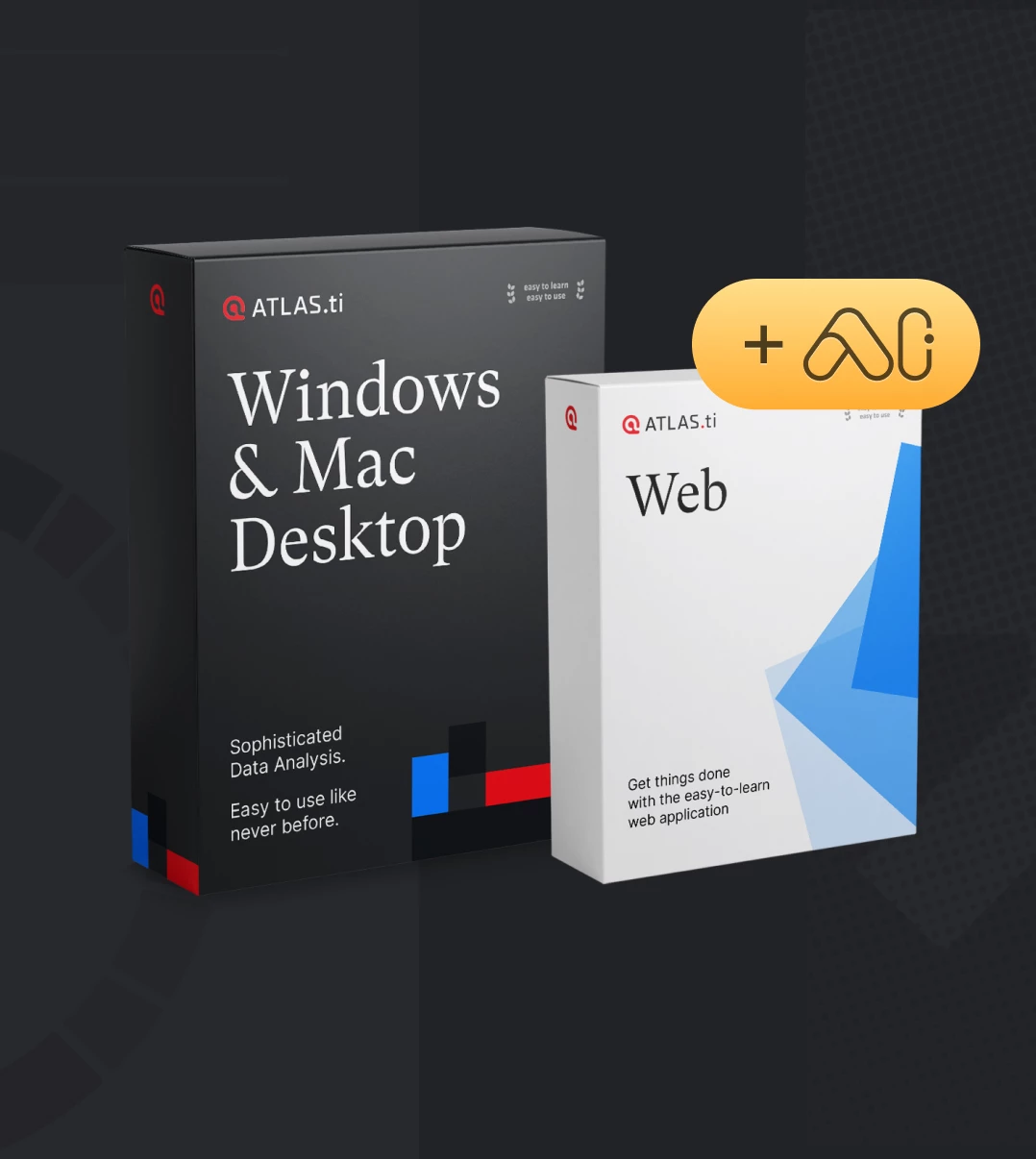

Organize your literature search with ATLAS.ti

Collect and categorize documents to identify gaps and key findings with ATLAS.ti. Download a free trial.

Conducting a literature review thematically provides a comprehensive and nuanced synthesis of research findings, distinguishing it from other types of literature reviews. Its structured approach not only facilitates a deeper understanding of the subject area but also enhances the clarity and relevance of the review. Here are three significant advantages of employing a thematic analysis in literature reviews.

Enhanced understanding of the research field

Thematic literature reviews allow for a detailed exploration of the research landscape, presenting themes that capture the essence of the subject area. By identifying and analyzing these themes, reviewers can construct a narrative that reflects the complexity and multifaceted nature of the field.

This process aids in uncovering underlying patterns and relationships, offering a more profound and insightful examination of the literature. As a result, readers gain an enriched understanding of the key concepts, debates, and evolutionary trajectories within the research area.

Identification of research gaps and trends

One of the pivotal benefits of a thematic literature review is its ability to highlight gaps in the existing body of research. By systematically organizing the literature into themes, reviewers can pinpoint areas that are under-explored or warrant further investigation.

Additionally, this method can reveal emerging trends and shifts in research focus, guiding scholars toward promising areas for future study. The thematic structure thus serves as a roadmap, directing researchers toward uncharted territories and new research questions .

Facilitates comparative analysis and integration of findings

A thematic literature review excels in synthesizing findings from diverse studies, enabling a coherent and integrated overview. By concentrating on themes rather than individual studies, the review can draw comparisons and contrasts across different research contexts and methodologies . This comparative analysis enriches the review, offering a panoramic view of the field that acknowledges both consensus and divergence among researchers.

Moreover, the thematic framework supports the integration of findings, presenting a unified and comprehensive portrayal of the research area. Such integration is invaluable for scholars seeking to navigate the extensive body of literature and extract pertinent insights relevant to their own research questions or objectives.

The process of structuring and writing a thematic literature review is pivotal in presenting research in a clear, coherent, and impactful manner. This review type necessitates a methodical approach to not only unearth and categorize key themes but also to articulate them in a manner that is both accessible and informative to the reader. The following sections outline essential stages in the thematic analysis process for literature reviews , offering a structured pathway from initial planning to the final presentation of findings.

Identifying and categorizing themes

The initial phase in a thematic literature review is the identification of themes within the collected body of literature. This involves a detailed examination of texts to discern patterns, concepts, and ideas that recur across the research landscape. Effective identification hinges on a thorough and nuanced reading of the literature, where the reviewer actively engages with the content to extract and note significant thematic elements. Once identified, these themes must be meticulously categorized, often requiring the reviewer to discern between overarching themes and more nuanced sub-themes, ensuring a logical and hierarchical organization of the review content.

Analyzing and synthesizing themes

After categorizing the themes, the next step involves a deeper analysis and synthesis of the identified themes. This stage is critical for understanding the relationships between themes and for interpreting the broader implications of the thematic findings. Analysis may reveal how themes evolve over time, differ across methodologies or contexts, or converge to highlight predominant trends in the research area. Synthesis involves integrating insights from various studies to construct a comprehensive narrative that encapsulates the thematic essence of the literature, offering new interpretations or revealing gaps in existing research.

Presenting and discussing findings

The final stage of the thematic literature review is the discussion of the thematic findings in a research paper or presentation. This entails not only a descriptive account of identified themes but also a critical examination of their significance within the research field. Each theme should be discussed in detail, elucidating its relevance, the extent of research support, and its implications for future studies. The review should culminate in a coherent and compelling narrative that not only summarizes the key thematic findings but also situates them within the broader research context, offering valuable insights and directions for future inquiry.

Gain a comprehensive understanding of your data with ATLAS.ti

Analyze qualitative data with specific themes that offer insights. See how with a free trial.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Write a Thematic Literature Review: A Beginner’s Guide

Literature reviews provide a comprehensive understanding of existing knowledge in a particular field, offer insights into gaps and trends, and ultimately lay the foundation for innovative research. However, when tackling complex topics spanning multiple issues, the conventional approach of a standard literature review might not suffice. Many researchers present a literature review without giving any thought to its organization or structure, but this is where a thematic literature review comes into play. In this article, we will explore the significance of thematic reviews, delve into how and when to undertake them, and offer invaluable guidance on structuring and crafting a compelling thematic literature review.

Table of Contents

What is a thematic literature review?

A thematic literature review, also known as a thematic review, involves organizing and synthesizing the existing literature based on recurring themes or topics rather than a chronological or methodological sequence. Typically, when a student or researcher works intensively on their research there are many sub-domains or associated spheres of knowledge that one encounters. While these may not have a direct bearing on the main idea being explored, they provide a much-needed background or context to the discussion. This is where a thematic literature review is useful when dealing with complex research questions that involve multiple facets, as it allows for a more in-depth exploration of specific themes within the broader context.

When to opt for thematic literature review?

It is common practice for early career researchers and students to collate all the literature reviews they have undertaken under one single broad umbrella. However, when working on a literature review that involves multiple themes, lack of organization and structure can slow you down and create confusion. Deciding to embark on a thematic literature review is a strategic choice that should align with your research objectives. Here are some scenarios where opting for a thematic review is advantageous:

- Broad Research Questions: When your research question spans across various dimensions and cannot be adequately addressed through a traditional literature review.

- Interdisciplinary Research: In cases where your research draws from multiple disciplines, a thematic review helps in synthesizing diverse literature cohesively.

- Emerging Research Areas: When exploring emerging fields or topics with limited existing literature, a thematic review can provide valuable insights by focusing on available themes.

- Complex Issues: Thematic reviews are ideal for dissecting complex issues with multiple contributing factors or dimensions.

Advantages of a Thematic Literature Review

With better comprehension and broad insights, thematic literature reviews can help in identifying possible research gaps across themes. A thematic literature review has several advantages over a general or broad-based approach, especially for those working on multiple related themes.

- It provides a comprehensive understanding of specific themes within a broader context, allowing for a deep exploration of relevant literature.

- Thematic reviews offer a structured approach to organizing and synthesizing diverse sources, making it easier to identify trends, patterns, and gaps.

- Researchers can focus on key themes, enabling a more detailed analysis of specific aspects of the research question.

- Thematic reviews facilitate the integration of literature from various disciplines, offering a holistic view of the topic.

- Researchers can provide targeted recommendations or insights related to specific themes, aiding in the formulation of research hypotheses.

Now that we know the benefits of a thematic literature review, what is the best way to arrange reviewed literature in a thematic format?

How to write a thematic literature review

To effectively structure and write a thematic literature review, follow these key steps:

- Define Your Research Question: Clearly define the overarching research question or topic you aim to explore thematically. When writing a thematic literature review, go through different literature review sections of published research work and understand the subtle nuances associated with this approach.

- Identify Themes: Analyze the literature to identify recurring themes or topics relevant to your research question. Categorize the bibliography by dividing them into relevant clusters or units, each dealing with a specific issue. For example, you can divide a topic based on a theoretical approach, methodology, discipline or by epistemology. A theoretical review of related literature for example, may also look to break down geography or issues pertaining to a single country into its different parts or along rural and urban divides.

- Organize the Literature: Group the literature into thematic clusters based on the identified themes. Each cluster represents a different aspect of your research question. It is up to you to define the different narratives of thematic literature reviews depending on the project being undertaken; there is no one formal way of doing this. You can weigh how specific areas stack up against others in terms of existing literature or studies and how many more aspects may need to be added or further looked into.

- Review and Synthesize: Within each thematic cluster, review and synthesize the relevant literature, highlighting key findings and insights. It is recommended to identify any theme-related strengths or weaknesses using an analytical lens.

- Integrate Themes: Analyze how the themes interact with each other, draw linkages between earlier studies and see how they contribute to your own research. A thematic literature review presents readers with a comprehensive overview of the literature available on and around the research topic.

- Provide a Framework: Develop a framework or conceptual model that illustrates the relationships between the themes. Present the most relevant part of the thematic review toward the end and study it in greater detail as it reflects the literature most relevant and directly related to the main research topic.

- Conclusion: Conclude your thematic literature review by summarizing the key findings and their implications for your research question. Be sure to highlight any gaps or areas requiring further investigation in this section.

- Cite and Reference: It is important to remember that a thematic review of literature for a PhD thesis or research paper lends greater credibility to the student or researcher. So ensure that you properly cite and reference all sources according to your chosen citation style.

- Edit and Proofread: Take some time to review your work, ensure proper structure and flow and eliminate any language, grammar, or spelling errors that could deviate reader attention. This will help you deliver a well-structured and elegantly written thematic literature review.

Thematic literature review example

In essence, a thematic literature review allows researchers to dissect complex topics into smaller manageable themes, providing a more focused and structured approach to literature synthesis. This method empowers researchers to gain deeper insights, identify gaps, and generate new knowledge within the context of their research.

To illustrate the process mentioned above, let’s consider an example of a thematic literature review in the context of sustainable development. Imagine the overarching research question is: “What are the key factors influencing sustainable urban planning?” Potential themes could include environmental sustainability, social equity, economic viability, and governance. Each theme would have a dedicated section in the review, summarizing relevant literature and discussing how these factors intersect and impact sustainable urban planning. Close with a strong conclusion that highlights research gaps or areas of investigation. Finally, review and refine the thematic literature review, adding citations and references as required.

In conclusion, when tackling multifaceted research questions, a thematic literature review proves to be an indispensable tool for researchers and students alike. By adopting this approach, scholars can navigate the intricate web of existing literature, unearth meaningful patterns, and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their respective fields. We hope the information in this article helps you create thematic reviews that illuminate your path to new discoveries and innovative insights.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What is Research Impact: Types and Tips for Academics

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Do Thematic Analysis | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

How to Do Thematic Analysis | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on September 6, 2019 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Thematic analysis is a method of analyzing qualitative data . It is usually applied to a set of texts, such as an interview or transcripts . The researcher closely examines the data to identify common themes – topics, ideas and patterns of meaning that come up repeatedly.

There are various approaches to conducting thematic analysis, but the most common form follows a six-step process: familiarization, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and writing up. Following this process can also help you avoid confirmation bias when formulating your analysis.

This process was originally developed for psychology research by Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke . However, thematic analysis is a flexible method that can be adapted to many different kinds of research.

Table of contents

When to use thematic analysis, different approaches to thematic analysis, step 1: familiarization, step 2: coding, step 3: generating themes, step 4: reviewing themes, step 5: defining and naming themes, step 6: writing up, other interesting articles.

Thematic analysis is a good approach to research where you’re trying to find out something about people’s views, opinions, knowledge, experiences or values from a set of qualitative data – for example, interview transcripts , social media profiles, or survey responses .

Some types of research questions you might use thematic analysis to answer:

- How do patients perceive doctors in a hospital setting?

- What are young women’s experiences on dating sites?

- What are non-experts’ ideas and opinions about climate change?

- How is gender constructed in high school history teaching?

To answer any of these questions, you would collect data from a group of relevant participants and then analyze it. Thematic analysis allows you a lot of flexibility in interpreting the data, and allows you to approach large data sets more easily by sorting them into broad themes.

However, it also involves the risk of missing nuances in the data. Thematic analysis is often quite subjective and relies on the researcher’s judgement, so you have to reflect carefully on your own choices and interpretations.

Pay close attention to the data to ensure that you’re not picking up on things that are not there – or obscuring things that are.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Once you’ve decided to use thematic analysis, there are different approaches to consider.

There’s the distinction between inductive and deductive approaches:

- An inductive approach involves allowing the data to determine your themes.

- A deductive approach involves coming to the data with some preconceived themes you expect to find reflected there, based on theory or existing knowledge.

Ask yourself: Does my theoretical framework give me a strong idea of what kind of themes I expect to find in the data (deductive), or am I planning to develop my own framework based on what I find (inductive)?

There’s also the distinction between a semantic and a latent approach:

- A semantic approach involves analyzing the explicit content of the data.

- A latent approach involves reading into the subtext and assumptions underlying the data.

Ask yourself: Am I interested in people’s stated opinions (semantic) or in what their statements reveal about their assumptions and social context (latent)?

After you’ve decided thematic analysis is the right method for analyzing your data, and you’ve thought about the approach you’re going to take, you can follow the six steps developed by Braun and Clarke .

The first step is to get to know our data. It’s important to get a thorough overview of all the data we collected before we start analyzing individual items.

This might involve transcribing audio , reading through the text and taking initial notes, and generally looking through the data to get familiar with it.

Next up, we need to code the data. Coding means highlighting sections of our text – usually phrases or sentences – and coming up with shorthand labels or “codes” to describe their content.

Let’s take a short example text. Say we’re researching perceptions of climate change among conservative voters aged 50 and up, and we have collected data through a series of interviews. An extract from one interview looks like this:

| Interview extract | Codes |

|---|---|

| Personally, I’m not sure. I think the climate is changing, sure, but I don’t know why or how. People say you should trust the experts, but who’s to say they don’t have their own reasons for pushing this narrative? I’m not saying they’re wrong, I’m just saying there’s reasons not to 100% trust them. The facts keep changing – it used to be called global warming. |

In this extract, we’ve highlighted various phrases in different colors corresponding to different codes. Each code describes the idea or feeling expressed in that part of the text.

At this stage, we want to be thorough: we go through the transcript of every interview and highlight everything that jumps out as relevant or potentially interesting. As well as highlighting all the phrases and sentences that match these codes, we can keep adding new codes as we go through the text.

After we’ve been through the text, we collate together all the data into groups identified by code. These codes allow us to gain a a condensed overview of the main points and common meanings that recur throughout the data.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Next, we look over the codes we’ve created, identify patterns among them, and start coming up with themes.

Themes are generally broader than codes. Most of the time, you’ll combine several codes into a single theme. In our example, we might start combining codes into themes like this:

| Codes | Theme |

|---|---|

| Uncertainty | |

| Distrust of experts | |

| Misinformation |

At this stage, we might decide that some of our codes are too vague or not relevant enough (for example, because they don’t appear very often in the data), so they can be discarded.

Other codes might become themes in their own right. In our example, we decided that the code “uncertainty” made sense as a theme, with some other codes incorporated into it.

Again, what we decide will vary according to what we’re trying to find out. We want to create potential themes that tell us something helpful about the data for our purposes.

Now we have to make sure that our themes are useful and accurate representations of the data. Here, we return to the data set and compare our themes against it. Are we missing anything? Are these themes really present in the data? What can we change to make our themes work better?

If we encounter problems with our themes, we might split them up, combine them, discard them or create new ones: whatever makes them more useful and accurate.

For example, we might decide upon looking through the data that “changing terminology” fits better under the “uncertainty” theme than under “distrust of experts,” since the data labelled with this code involves confusion, not necessarily distrust.

Now that you have a final list of themes, it’s time to name and define each of them.

Defining themes involves formulating exactly what we mean by each theme and figuring out how it helps us understand the data.

Naming themes involves coming up with a succinct and easily understandable name for each theme.

For example, we might look at “distrust of experts” and determine exactly who we mean by “experts” in this theme. We might decide that a better name for the theme is “distrust of authority” or “conspiracy thinking”.

Finally, we’ll write up our analysis of the data. Like all academic texts, writing up a thematic analysis requires an introduction to establish our research question, aims and approach.

We should also include a methodology section, describing how we collected the data (e.g. through semi-structured interviews or open-ended survey questions ) and explaining how we conducted the thematic analysis itself.

The results or findings section usually addresses each theme in turn. We describe how often the themes come up and what they mean, including examples from the data as evidence. Finally, our conclusion explains the main takeaways and shows how the analysis has answered our research question.

In our example, we might argue that conspiracy thinking about climate change is widespread among older conservative voters, point out the uncertainty with which many voters view the issue, and discuss the role of misinformation in respondents’ perceptions.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, June 22). How to Do Thematic Analysis | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 13, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/thematic-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is qualitative research | methods & examples, inductive vs. deductive research approach | steps & examples, critical discourse analysis | definition, guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 10 July 2008

Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews

- James Thomas 1 &

- Angela Harden 1

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 8 , Article number: 45 ( 2008 ) Cite this article

396k Accesses

4536 Citations

104 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is a growing recognition of the value of synthesising qualitative research in the evidence base in order to facilitate effective and appropriate health care. In response to this, methods for undertaking these syntheses are currently being developed. Thematic analysis is a method that is often used to analyse data in primary qualitative research. This paper reports on the use of this type of analysis in systematic reviews to bring together and integrate the findings of multiple qualitative studies.

We describe thematic synthesis, outline several steps for its conduct and illustrate the process and outcome of this approach using a completed review of health promotion research. Thematic synthesis has three stages: the coding of text 'line-by-line'; the development of 'descriptive themes'; and the generation of 'analytical themes'. While the development of descriptive themes remains 'close' to the primary studies, the analytical themes represent a stage of interpretation whereby the reviewers 'go beyond' the primary studies and generate new interpretive constructs, explanations or hypotheses. The use of computer software can facilitate this method of synthesis; detailed guidance is given on how this can be achieved.

We used thematic synthesis to combine the studies of children's views and identified key themes to explore in the intervention studies. Most interventions were based in school and often combined learning about health benefits with 'hands-on' experience. The studies of children's views suggested that fruit and vegetables should be treated in different ways, and that messages should not focus on health warnings. Interventions that were in line with these suggestions tended to be more effective. Thematic synthesis enabled us to stay 'close' to the results of the primary studies, synthesising them in a transparent way, and facilitating the explicit production of new concepts and hypotheses.

We compare thematic synthesis to other methods for the synthesis of qualitative research, discussing issues of context and rigour. Thematic synthesis is presented as a tried and tested method that preserves an explicit and transparent link between conclusions and the text of primary studies; as such it preserves principles that have traditionally been important to systematic reviewing.

Peer Review reports

The systematic review is an important technology for the evidence-informed policy and practice movement, which aims to bring research closer to decision-making [ 1 , 2 ]. This type of review uses rigorous and explicit methods to bring together the results of primary research in order to provide reliable answers to particular questions [ 3 – 6 ]. The picture that is presented aims to be distorted neither by biases in the review process nor by biases in the primary research which the review contains [ 7 – 10 ]. Systematic review methods are well-developed for certain types of research, such as randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Methods for reviewing qualitative research in a systematic way are still emerging, and there is much ongoing development and debate [ 11 – 14 ].

In this paper we present one approach to the synthesis of findings of qualitative research, which we have called 'thematic synthesis'. We have developed and applied these methods within several systematic reviews that address questions about people's perspectives and experiences [ 15 – 18 ]. The context for this methodological development is a programme of work in health promotion and public health (HP & PH), mostly funded by the English Department of Health, at the EPPI-Centre, in the Social Science Research Unit at the Institute of Education, University of London in the UK. Early systematic reviews at the EPPI-Centre addressed the question 'what works?' and contained research testing the effects of interventions. However, policy makers and other review users also posed questions about intervention need, appropriateness and acceptability, and factors influencing intervention implementation. To address these questions, our reviews began to include a wider range of research, including research often described as 'qualitative'. We began to focus, in particular, on research that aimed to understand the health issue in question from the experiences and point of view of the groups of people targeted by HP&PH interventions (We use the term 'qualitative' research cautiously because it encompasses a multitude of research methods at the same time as an assumed range of epistemological positions. In practice it is often difficult to classify research as being either 'qualitative' or 'quantitative' as much research contains aspects of both [ 19 – 22 ]. Because the term is in common use, however, we will employ it in this paper).

When we started the work for our first series of reviews which included qualitative research in 1999 [ 23 – 26 ], there was very little published material that described methods for synthesising this type of research. We therefore experimented with a variety of techniques borrowed from standard systematic review methods and methods for analysing primary qualitative research [ 15 ]. In later reviews, we were able to refine these methods and began to apply thematic analysis in a more explicit way. The methods for thematic synthesis described in this paper have so far been used explicitly in three systematic reviews [ 16 – 18 ].

The review used as an example in this paper

To illustrate the steps involved in a thematic synthesis we draw on a review of the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating amongst children aged four to 10 years old [ 17 ]. The review was commissioned by the Department of Health, England to inform policy about how to encourage children to eat healthily in the light of recent surveys highlighting that British children are eating less than half the recommended five portions of fruit and vegetables per day. While we focus on the aspects of the review that relate to qualitative studies, the review was broader than this and combined answering traditional questions of effectiveness, through reviewing controlled trials, with questions relating to children's views of healthy eating, which were answered using qualitative studies. The qualitative studies were synthesised using 'thematic synthesis' – the subject of this paper. We compared the effectiveness of interventions which appeared to be in line with recommendations from the thematic synthesis with those that did not. This enabled us to see whether the understandings we had gained from the children's views helped us to explain differences in the effectiveness of different interventions: the thematic synthesis had enabled us to generate hypotheses which could be tested against the findings of the quantitative studies – hypotheses that we could not have generated without the thematic synthesis. The methods of this part of the review are published in Thomas et al . [ 27 ] and are discussed further in Harden and Thomas [ 21 ].

Qualitative research and systematic reviews

The act of seeking to synthesise qualitative research means stepping into more complex and contested territory than is the case when only RCTs are included in a review. First, methods are much less developed in this area, with fewer completed reviews available from which to learn, and second, the whole enterprise of synthesising qualitative research is itself hotly debated. Qualitative research, it is often proposed, is not generalisable and is specific to a particular context, time and group of participants. Thus, in bringing such research together, reviewers are open to the charge that they de-contextualise findings and wrongly assume that these are commensurable [ 11 , 13 ]. These are serious concerns which it is not the purpose of this paper to contest. We note, however, that a strong case has been made for qualitative research to be valued for the potential it has to inform policy and practice [ 11 , 28 – 30 ]. In our experience, users of reviews are interested in the answers that only qualitative research can provide, but are not able to handle the deluge of data that would result if they tried to locate, read and interpret all the relevant research themselves. Thus, if we acknowledge the unique importance of qualitative research, we need also to recognise that methods are required to bring its findings together for a wide audience – at the same time as preserving and respecting its essential context and complexity.

The earliest published work that we know of that deals with methods for synthesising qualitative research was written in 1988 by Noblit and Hare [ 31 ]. This book describes the way that ethnographic research might be synthesised, but the method has been shown to be applicable to qualitative research beyond ethnography [ 32 , 11 ]. As well as meta-ethnography, other methods have been developed more recently, including 'meta-study' [ 33 ], 'critical interpretive synthesis' [ 34 ] and 'metasynthesis' [ 13 ].

Many of the newer methods being developed have much in common with meta-ethnography, as originally described by Noblit and Hare, and often state explicitly that they are drawing on this work. In essence, this method involves identifying key concepts from studies and translating them into one another. The term 'translating' in this context refers to the process of taking concepts from one study and recognising the same concepts in another study, though they may not be expressed using identical words. Explanations or theories associated with these concepts are also extracted and a 'line of argument' may be developed, pulling corroborating concepts together and, crucially, going beyond the content of the original studies (though 'refutational' concepts might not be amenable to this process). Some have claimed that this notion of 'going beyond' the primary studies is a critical component of synthesis, and is what distinguishes it from the types of summaries of findings that typify traditional literature reviews [e.g. [ 32 ], p209]. In the words of Margarete Sandelowski, "metasyntheses are integrations that are more than the sum of parts, in that they offer novel interpretations of findings. These interpretations will not be found in any one research report but, rather, are inferences derived from taking all of the reports in a sample as a whole" [[ 14 ], p1358].

Thematic analysis has been identified as one of a range of potential methods for research synthesis alongside meta-ethnography and 'metasynthesis', though precisely what the method involves is unclear, and there are few examples of it being used for synthesising research [ 35 ]. We have adopted the term 'thematic synthesis', as we translated methods for the analysis of primary research – often termed 'thematic' – for use in systematic reviews [ 36 – 38 ]. As Boyatzis [[ 36 ], p4] has observed, thematic analysis is "not another qualitative method but a process that can be used with most, if not all, qualitative methods..." . Our approach concurs with this conceptualisation of thematic analysis, since the method we employed draws on other established methods but uses techniques commonly described as 'thematic analysis' in order to formalise the identification and development of themes.

We now move to a description of the methods we used in our example systematic review. While this paper has the traditional structure for reporting the results of a research project, the detailed methods (e.g. precise terms we used for searching) and results are available online. This paper identifies the particular issues that relate especially to reviewing qualitative research systematically and then to describing the activity of thematic synthesis in detail.

When searching for studies for inclusion in a 'traditional' statistical meta-analysis, the aim of searching is to locate all relevant studies. Failing to do this can undermine the statistical models that underpin the analysis and bias the results. However, Doyle [[ 39 ], p326] states that, "like meta-analysis, meta-ethnography utilizes multiple empirical studies but, unlike meta-analysis, the sample is purposive rather than exhaustive because the purpose is interpretive explanation and not prediction" . This suggests that it may not be necessary to locate every available study because, for example, the results of a conceptual synthesis will not change if ten rather than five studies contain the same concept, but will depend on the range of concepts found in the studies, their context, and whether they are in agreement or not. Thus, principles such as aiming for 'conceptual saturation' might be more appropriate when planning a search strategy for qualitative research, although it is not yet clear how these principles can be applied in practice. Similarly, other principles from primary qualitative research methods may also be 'borrowed' such as deliberately seeking studies which might act as negative cases, aiming for maximum variability and, in essence, designing the resulting set of studies to be heterogeneous, in some ways, instead of achieving the homogeneity that is often the aim in statistical meta-analyses.

However you look, qualitative research is difficult to find [ 40 – 42 ]. In our review, it was not possible to rely on simple electronic searches of databases. We needed to search extensively in 'grey' literature, ask authors of relevant papers if they knew of more studies, and look especially for book chapters, and we spent a lot of effort screening titles and abstracts by hand and looking through journals manually. In this sense, while we were not driven by the statistical imperative of locating every relevant study, when it actually came down to searching, we found that there was very little difference in the methods we had to use to find qualitative studies compared to the methods we use when searching for studies for inclusion in a meta-analysis.

Quality assessment

Assessing the quality of qualitative research has attracted much debate and there is little consensus regarding how quality should be assessed, who should assess quality, and, indeed, whether quality can or should be assessed in relation to 'qualitative' research at all [ 43 , 22 , 44 , 45 ]. We take the view that the quality of qualitative research should be assessed to avoid drawing unreliable conclusions. However, since there is little empirical evidence on which to base decisions for excluding studies based on quality assessment, we took the approach in this review to use 'sensitivity analyses' (described below) to assess the possible impact of study quality on the review's findings.

In our example review we assessed our studies according to 12 criteria, which were derived from existing sets of criteria proposed for assessing the quality of qualitative research [ 46 – 49 ], principles of good practice for conducting social research with children [ 50 ], and whether studies employed appropriate methods for addressing our review questions. The 12 criteria covered three main quality issues. Five related to the quality of the reporting of a study's aims, context, rationale, methods and findings (e.g. was there an adequate description of the sample used and the methods for how the sample was selected and recruited?). A further four criteria related to the sufficiency of the strategies employed to establish the reliability and validity of data collection tools and methods of analysis, and hence the validity of the findings. The final three criteria related to the assessment of the appropriateness of the study methods for ensuring that findings about the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating were rooted in children's own perspectives (e.g. were data collection methods appropriate for helping children to express their views?).

Extracting data from studies

One issue which is difficult to deal with when synthesising 'qualitative' studies is 'what counts as data' or 'findings'? This problem is easily addressed when a statistical meta-analysis is being conducted: the numeric results of RCTs – for example, the mean difference in outcome between the intervention and control – are taken from published reports and are entered into the software package being used to calculate the pooled effect size [ 3 , 51 ].

Deciding what to abstract from the published report of a 'qualitative' study is much more difficult. Campbell et al . [ 11 ] extracted what they called the 'key concepts' from the qualitative studies they found about patients' experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. However, finding the key concepts in 'qualitative' research is not always straightforward either. As Sandelowski and Barroso [ 52 ] discovered, identifying the findings in qualitative research can be complicated by varied reporting styles or the misrepresentation of data as findings (as for example when data are used to 'let participants speak for themselves'). Sandelowski and Barroso [ 53 ] have argued that the findings of qualitative (and, indeed, all empirical) research are distinct from the data upon which they are based, the methods used to derive them, externally sourced data, and researchers' conclusions and implications.

In our example review, while it was relatively easy to identify 'data' in the studies – usually in the form of quotations from the children themselves – it was often difficult to identify key concepts or succinct summaries of findings, especially for studies that had undertaken relatively simple analyses and had not gone much further than describing and summarising what the children had said. To resolve this problem we took study findings to be all of the text labelled as 'results' or 'findings' in study reports – though we also found 'findings' in the abstracts which were not always reported in the same way in the text. Study reports ranged in size from a few pages to full final project reports. We entered all the results of the studies verbatim into QSR's NVivo software for qualitative data analysis. Where we had the documents in electronic form this process was straightforward even for large amounts of text. When electronic versions were not available, the results sections were either re-typed or scanned in using a flat-bed or pen scanner. (We have since adapted our own reviewing system, 'EPPI-Reviewer' [ 54 ], to handle this type of synthesis and the screenshots below show this software.)

Detailed methods for thematic synthesis

The synthesis took the form of three stages which overlapped to some degree: the free line-by-line coding of the findings of primary studies; the organisation of these 'free codes' into related areas to construct 'descriptive' themes; and the development of 'analytical' themes.

Stages one and two: coding text and developing descriptive themes

In our children and healthy eating review, we originally planned to extract and synthesise study findings according to our review questions regarding the barriers to, and facilitators of, healthy eating amongst children. It soon became apparent, however, that few study findings addressed these questions directly and it appeared that we were in danger of ending up with an empty synthesis. We were also concerned about imposing the a priori framework implied by our review questions onto study findings without allowing for the possibility that a different or modified framework may be a better fit. We therefore temporarily put our review questions to one side and started from the study findings themselves to conduct an thematic analysis.

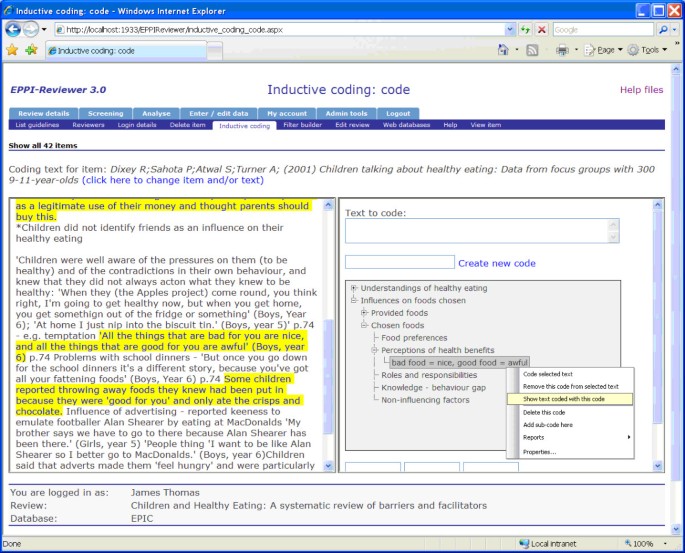

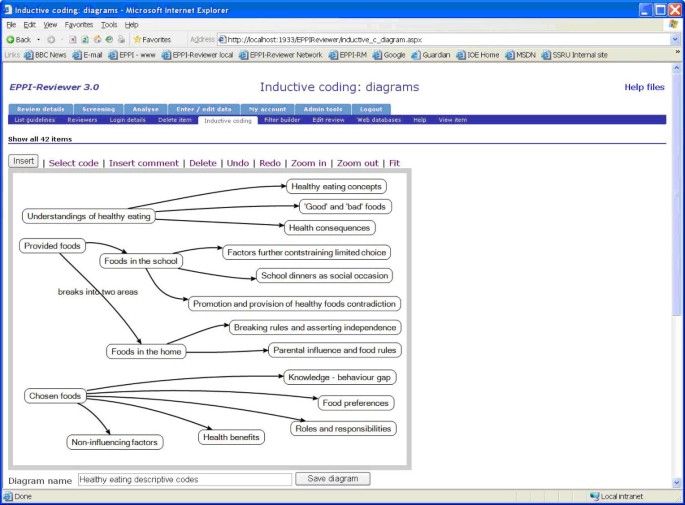

There were eight relevant qualitative studies examining children's views of healthy eating. We entered the verbatim findings of these studies into our database. Three reviewers then independently coded each line of text according to its meaning and content. Figure 1 illustrates this line-by-line coding using our specialist reviewing software, EPPI-Reviewer, which includes a component designed to support thematic synthesis. The text which was taken from the report of the primary study is on the left and codes were created inductively to capture the meaning and content of each sentence. Codes could be structured, either in a tree form (as shown in the figure) or as 'free' codes – without a hierarchical structure.

line-by-line coding in EPPI-Reviewer.

The use of line-by-line coding enabled us to undertake what has been described as one of the key tasks in the synthesis of qualitative research: the translation of concepts from one study to another [ 32 , 55 ]. However, this process may not be regarded as a simple one of translation. As we coded each new study we added to our 'bank' of codes and developed new ones when necessary. As well as translating concepts between studies, we had already begun the process of synthesis (For another account of this process, see Doyle [[ 39 ], p331]). Every sentence had at least one code applied, and most were categorised using several codes (e.g. 'children prefer fruit to vegetables' or 'why eat healthily?'). Before completing this stage of the synthesis, we also examined all the text which had a given code applied to check consistency of interpretation and to see whether additional levels of coding were needed. (In grounded theory this is termed 'axial' coding; see Fisher [ 55 ] for further discussion of the application of axial coding in research synthesis.) This process created a total of 36 initial codes. For example, some of the text we coded as "bad food = nice, good food = awful" from one study [ 56 ] were:

'All the things that are bad for you are nice and all the things that are good for you are awful.' (Boys, year 6) [[ 56 ], p74]

'All adverts for healthy stuff go on about healthy things. The adverts for unhealthy things tell you how nice they taste.' [[ 56 ], p75]

Some children reported throwing away foods they knew had been put in because they were 'good for you' and only ate the crisps and chocolate . [[ 56 ], p75]

Reviewers looked for similarities and differences between the codes in order to start grouping them into a hierarchical tree structure. New codes were created to capture the meaning of groups of initial codes. This process resulted in a tree structure with several layers to organize a total of 12 descriptive themes (Figure 2 ). For example, the first layer divided the 12 themes into whether they were concerned with children's understandings of healthy eating or influences on children's food choice. The above example, about children's preferences for food, was placed in both areas, since the findings related both to children's reactions to the foods they were given, and to how they behaved when given the choice over what foods they might eat. A draft summary of the findings across the studies organized by the 12 descriptive themes was then written by one of the review authors. Two other review authors commented on this draft and a final version was agreed.

relationships between descriptive themes.

Stage three: generating analytical themes

Up until this point, we had produced a synthesis which kept very close to the original findings of the included studies. The findings of each study had been combined into a whole via a listing of themes which described children's perspectives on healthy eating. However, we did not yet have a synthesis product that addressed directly the concerns of our review – regarding how to promote healthy eating, in particular fruit and vegetable intake, amongst children. Neither had we 'gone beyond' the findings of the primary studies and generated additional concepts, understandings or hypotheses. As noted earlier, the idea or step of 'going beyond' the content of the original studies has been identified by some as the defining characteristic of synthesis [ 32 , 14 ].

This stage of a qualitative synthesis is the most difficult to describe and is, potentially, the most controversial, since it is dependent on the judgement and insights of the reviewers. The equivalent stage in meta-ethnography is the development of 'third order interpretations' which go beyond the content of original studies [ 32 , 11 ]. In our example, the step of 'going beyond' the content of the original studies was achieved by using the descriptive themes that emerged from our inductive analysis of study findings to answer the review questions we had temporarily put to one side. Reviewers inferred barriers and facilitators from the views children were expressing about healthy eating or food in general, captured by the descriptive themes, and then considered the implications of children's views for intervention development. Each reviewer first did this independently and then as a group. Through this discussion more abstract or analytical themes began to emerge. The barriers and facilitators and implications for intervention development were examined again in light of these themes and changes made as necessary. This cyclical process was repeated until the new themes were sufficiently abstract to describe and/or explain all of our initial descriptive themes, our inferred barriers and facilitators and implications for intervention development.

For example, five of the 12 descriptive themes concerned the influences on children's choice of foods (food preferences, perceptions of health benefits, knowledge behaviour gap, roles and responsibilities, non-influencing factors). From these, reviewers inferred several barriers and implications for intervention development. Children identified readily that taste was the major concern for them when selecting food and that health was either a secondary factor or, in some cases, a reason for rejecting food. Children also felt that buying healthy food was not a legitimate use of their pocket money, which they would use to buy sweets that could be enjoyed with friends. These perspectives indicated to us that branding fruit and vegetables as a 'tasty' rather than 'healthy' might be more effective in increasing consumption. As one child noted astutely, 'All adverts for healthy stuff go on about healthy things. The adverts for unhealthy things tell you how nice they taste.' [[ 56 ], p75]. We captured this line of argument in the analytical theme entitled 'Children do not see it as their role to be interested in health'. Altogether, this process resulted in the generation of six analytical themes which were associated with ten recommendations for interventions.

Six main issues emerged from the studies of children's views: (1) children do not see it as their role to be interested in health; (2) children do not see messages about future health as personally relevant or credible; (3) fruit, vegetables and confectionery have very different meanings for children; (4) children actively seek ways to exercise their own choices with regard to food; (5) children value eating as a social occasion; and (6) children see the contradiction between what is promoted in theory and what adults provide in practice. The review found that most interventions were based in school (though frequently with parental involvement) and often combined learning about the health benefits of fruit and vegetables with 'hands-on' experience in the form of food preparation and taste-testing. Interventions targeted at people with particular risk factors worked better than others, and multi-component interventions that combined the promotion of physical activity with healthy eating did not work as well as those that only concentrated on healthy eating. The studies of children's views suggested that fruit and vegetables should be treated in different ways in interventions, and that messages should not focus on health warnings. Interventions that were in line with these suggestions tended to be more effective than those which were not.

Context and rigour in thematic synthesis

The process of translation, through the development of descriptive and analytical themes, can be carried out in a rigorous way that facilitates transparency of reporting. Since we aim to produce a synthesis that both generates 'abstract and formal theories' that are nevertheless 'empirically faithful to the cases from which they were developed' [[ 53 ], p1371], we see the explicit recording of the development of themes as being central to the method. The use of software as described can facilitate this by allowing reviewers to examine the contribution made to their findings by individual studies, groups of studies, or sub-populations within studies.

Some may argue against the synthesis of qualitative research on the grounds that the findings of individual studies are de-contextualised and that concepts identified in one setting are not applicable to others [ 32 ]. However, the act of synthesis could be viewed as similar to the role of a research user when reading a piece of qualitative research and deciding how useful it is to their own situation. In the case of synthesis, reviewers translate themes and concepts from one situation to another and can always be checking that each transfer is valid and whether there are any reasons that understandings gained in one context might not be transferred to another. We attempted to preserve context by providing structured summaries of each study detailing aims, methods and methodological quality, and setting and sample. This meant that readers of our review were able to judge for themselves whether or not the contexts of the studies the review contained were similar to their own. In the synthesis we also checked whether the emerging findings really were transferable across different study contexts. For example, we tried throughout the synthesis to distinguish between participants (e.g. boys and girls) where the primary research had made an appropriate distinction. We then looked to see whether some of our synthesis findings could be attributed to a particular group of children or setting. In the event, we did not find any themes that belonged to a specific group, but another outcome of this process was a realisation that the contextual information given in the reports of studies was very restricted indeed. It was therefore difficult to make the best use of context in our synthesis.

In checking that we were not translating concepts into situations where they did not belong, we were following a principle that others have followed when using synthesis methods to build grounded formal theory: that of grounding a text in the context in which it was constructed. As Margaret Kearney has noted "the conditions under which data were collected, analysis was done, findings were found, and products were written for each contributing report should be taken into consideration in developing a more generalized and abstract model" [[ 14 ], p1353]. Britten et al . [ 32 ] suggest that it may be important to make a deliberate attempt to include studies conducted across diverse settings to achieve the higher level of abstraction that is aimed for in a meta-ethnography.

Study quality and sensitivity analyses

We assessed the 'quality' of our studies with regard to the degree to which they represented the views of their participants. In doing this, we were locating the concept of 'quality' within the context of the purpose of our review – children's views – and not necessarily the context of the primary studies themselves. Our 'hierarchy of evidence', therefore, did not prioritise the research design of studies but emphasised the ability of the studies to answer our review question. A traditional systematic review of controlled trials would contain a quality assessment stage, the purpose of which is to exclude studies that do not provide a reliable answer to the review question. However, given that there were no accepted – or empirically tested – methods for excluding qualitative studies from syntheses on the basis of their quality [ 57 , 12 , 58 ], we included all studies regardless of their quality.

Nevertheless, our studies did differ according to the quality criteria they were assessed against and it was important that we considered this in some way. In systematic reviews of trials, 'sensitivity analyses' – analyses which test the effect on the synthesis of including and excluding findings from studies of differing quality – are often carried out. Dixon-Woods et al . [ 12 ] suggest that assessing the feasibility and worth of conducting sensitivity analyses within syntheses of qualitative research should be an important focus of synthesis methods work. After our thematic synthesis was complete, we examined the relative contributions of studies to our final analytic themes and recommendations for interventions. We found that the poorer quality studies contributed comparatively little to the synthesis and did not contain many unique themes; the better studies, on the other hand, appeared to have more developed analyses and contributed most to the synthesis.

This paper has discussed the rationale for reviewing and synthesising qualitative research in a systematic way and has outlined one specific approach for doing this: thematic synthesis. While it is not the only method which might be used – and we have discussed some of the other options available – we present it here as a tested technique that has worked in the systematic reviews in which it has been employed.

We have observed that one of the key tasks in the synthesis of qualitative research is the translation of concepts between studies. While the activity of translating concepts is usually undertaken in the few syntheses of qualitative research that exist, there are few examples that specify the detail of how this translation is actually carried out. The example above shows how we achieved the translation of concepts across studies through the use of line-by-line coding, the organisation of these codes into descriptive themes, and the generation of analytical themes through the application of a higher level theoretical framework. This paper therefore also demonstrates how the methods and process of a thematic synthesis can be written up in a transparent way.

This paper goes some way to addressing concerns regarding the use of thematic analysis in research synthesis raised by Dixon-Woods and colleagues who argue that the approach can lack transparency due to a failure to distinguish between 'data-driven' or 'theory-driven' approaches. Moreover they suggest that, "if thematic analysis is limited to summarising themes reported in primary studies, it offers little by way of theoretical structure within which to develop higher order thematic categories..." [[ 35 ], p47]. Part of the problem, they observe, is that the precise methods of thematic synthesis are unclear. Our approach contains a clear separation between the 'data-driven' descriptive themes and the 'theory-driven' analytical themes and demonstrates how the review questions provided a theoretical structure within which it became possible to develop higher order thematic categories.

The theme of 'going beyond' the content of the primary studies was discussed earlier. Citing Strike and Posner [ 59 ], Campbell et al . [[ 11 ], p672] also suggest that synthesis "involves some degree of conceptual innovation, or employment of concepts not found in the characterisation of the parts and a means of creating the whole" . This was certainly true of the example given in this paper. We used a series of questions, derived from the main topic of our review, to focus an examination of our descriptive themes and we do not find our recommendations for interventions contained in the findings of the primary studies: these were new propositions generated by the reviewers in the light of the synthesis. The method also demonstrates that it is possible to synthesise without conceptual innovation. The initial synthesis, involving the translation of concepts between studies, was necessary in order for conceptual innovation to begin. One could argue that the conceptual innovation, in this case, was only necessary because the primary studies did not address our review question directly. In situations in which the primary studies are concerned directly with the review question, it may not be necessary to go beyond the contents of the original studies in order to produce a satisfactory synthesis (see, for example, Marston and King, [ 60 ]). Conceptually, our analytical themes are similar to the ultimate product of meta-ethnographies: third order interpretations [ 11 ], since both are explicit mechanisms for going beyond the content of the primary studies and presenting this in a transparent way. The main difference between them lies in their purposes. Third order interpretations bring together the implications of translating studies into one another in their own terms, whereas analytical themes are the result of interrogating a descriptive synthesis by placing it within an external theoretical framework (our review question and sub-questions). It may be, therefore, that analytical themes are more appropriate when a specific review question is being addressed (as often occurs when informing policy and practice), and third order interpretations should be used when a body of literature is being explored in and of itself, with broader, or emergent, review questions.

This paper is a contribution to the current developmental work taking place in understanding how best to bring together the findings of qualitative research to inform policy and practice. It is by no means the only method on offer but, by drawing on methods and principles from qualitative primary research, it benefits from the years of methodological development that underpins the research it seeks to synthesise.

Chalmers I: Trying to do more good than harm in policy and practice: the role of rigorous, transparent and up-to-date evaluations. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2003, 589: 22-40. 10.1177/0002716203254762.

Article Google Scholar

Oakley A: Social science and evidence-based everything: the case of education. Educ Rev. 2002, 54: 277-286. 10.1080/0013191022000016329.

Cooper H, Hedges L: The Handbook of Research Synthesis. 1994, New York: Russell Sage Foundation

Google Scholar

EPPI-Centre: EPPI-Centre Methods for Conducting Systematic Reviews. 2006, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, [ http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=89 ]

Higgins J, Green S, (Eds): Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6. 2006, Updated September 2006. Accessed 24th January 2007, [ http://www.cochrane.org/resources/handbook/ ]

Petticrew M, Roberts H: Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A practical guide. 2006, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Book Google Scholar

Chalmers I, Hedges L, Cooper H: A brief history of research synthesis. Eval Health Prof. 2002, 25: 12-37. 10.1177/0163278702025001003.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Juni P, Altman D, Egger M: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001, 323: 42-46. 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mulrow C: Systematic reviews: rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994, 309: 597-599.

White H: Scientific communication and literature retrieval. The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Edited by: Cooper H, Hedges L. 1994, New York: Russell Sage Foundation

Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, Britten N, Pill R, Morgan M, Donovan J: Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med. 2003, 56: 671-684. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00064-3.

Dixon-Woods M, Bonas S, Booth A, Jones DR, Miller T, Sutton AJ, Shaw RL, Smith JA, Young B: How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qual Res. 2006, 6: 27-44. 10.1177/1468794106058867.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J: Handbook for Synthesising Qualitative Research. 2007, New York: Springer

Thorne S, Jensen L, Kearney MH, Noblit G, Sandelowski M: Qualitative meta-synthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual Health Res. 2004, 14: 1342-1365. 10.1177/1049732304269888.

Harden A, Garcia J, Oliver S, Rees R, Shepherd J, Brunton G, Oakley A: Applying systematic review methods to studies of people's views: an example from public health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004, 58: 794-800. 10.1136/jech.2003.014829.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harden A, Brunton G, Fletcher A, Oakley A: Young People, Pregnancy and Social Exclusion: A systematic synthesis of research evidence to identify effective, appropriate and promising approaches for prevention and support. 2006, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, [ http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=674 ]

Thomas J, Sutcliffe K, Harden A, Oakley A, Oliver S, Rees R, Brunton G, Kavanagh J: Children and Healthy Eating: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators. 2003, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, accessed 4 th July 2008, [ http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=246 ]

Thomas J, Kavanagh J, Tucker H, Burchett H, Tripney J, Oakley A: Accidental Injury, Risk-Taking Behaviour and the Social Circumstances in which Young People Live: A systematic review. 2007, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, [ http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=1910 ]

Bryman A: Quantity and Quality in Social Research. 1998, London: Unwin

Hammersley M: What's Wrong with Ethnography?. 1992, London: Routledge

Harden A, Thomas J: Methodological issues in combining diverse study types in systematic reviews. Int J Soc Res Meth. 2005, 8: 257-271. 10.1080/13645570500155078.

Oakley A: Experiments in Knowing: Gender and methods in the social sciences. 2000, Cambridge: Polity Press

Harden A, Oakley A, Oliver S: Peer-delivered health promotion for young people: a systematic review of different study designs. Health Educ J. 2001, 60: 339-353. 10.1177/001789690106000406.

Harden A, Rees R, Shepherd J, Brunton G, Oliver S, Oakley A: Young People and Mental Health: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators. 2001, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, [ http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=256 ]

Rees R, Harden A, Shepherd J, Brunton G, Oliver S, Oakley A: Young People and Physical Activity: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators. 2001, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, [ http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=260 ]

Shepherd J, Harden A, Rees R, Brunton G, Oliver S, Oakley A: Young People and Healthy Eating: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators. 2001, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, [ http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=258 ]

Thomas J, Harden A, Oakley A, Oliver S, Sutcliffe K, Rees R, Brunton G, Kavanagh J: Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews: an example from public health. BMJ. 2004, 328: 1010-1012. 10.1136/bmj.328.7446.1010.

Davies P: What is evidence-based education?. Br J Educ Stud. 1999, 47: 108-121. 10.1111/1467-8527.00106.

Newman M, Thompson C, Roberts AP: Helping practitioners understand the contribution of qualitative research to evidence-based practice. Evid Based Nurs. 2006, 9: 4-7. 10.1136/ebn.9.1.4.

Popay J: Moving Beyond Effectiveness in Evidence Synthesis. 2006, London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

Noblit GW, Hare RD: Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. 1988, Newbury Park: Sage

Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R: Using meta-ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002, 7: 209-215. 10.1258/135581902320432732.

Paterson B, Thorne S, Canam C, Jillings C: Meta-Study of Qualitative Health Research. 2001, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, Katbamna S, Olsen R, Smith L, Riley R, Sutton AJ: Conducting a critical interpretative synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006, 6: 35-10.1186/1471-2288-6-35.

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A: Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005, 10: 45-53. 10.1258/1355819052801804.

Boyatzis RE: Transforming Qualitative Information. 1998, Sage: Cleveland

Braun V, Clarke V: Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006, 3: 77-101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [ http://science.uwe.ac.uk/psychology/drvictoriaclarke_files/thematicanalysis%20.pdf ]

Silverman D, Ed: Qualitative Research: Theory, method and practice. 1997, London: Sage

Doyle LH: Synthesis through meta-ethnography: paradoxes, enhancements, and possibilities. Qual Res. 2003, 3: 321-344. 10.1177/1468794103033003.

Barroso J, Gollop C, Sandelowski M, Meynell J, Pearce PF, Collins LJ: The challenges of searching for and retrieving qualitative studies. Western J Nurs Res. 2003, 25: 153-178. 10.1177/0193945902250034.

Walters LA, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB, Hedges Team: Developing optimal search strategies for retrieving clinically relevant qualitative studies in EMBASE. Qual Health Res. 2006, 16: 162-8. 10.1177/1049732305284027.

Wong SSL, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB: Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in Medline. Medinfo. 2004, 11: 311-314.

Murphy E, Dingwall R, Greatbatch D, Parker S, Watson P: Qualitative research methods in health technology assessment: a review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 1998, 2 (16):

Seale C: Quality in qualitative research. Qual Inq. 1999, 5: 465-478.

Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, Dillon L: Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. 2003, London: Cabinet Office

Boulton M, Fitzpatrick R, Swinburn C: Qualitative research in healthcare II: a structured review and evaluation of studies. J Eval Clin Pract. 1996, 2: 171-179. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.1996.tb00041.x.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Cobb A, Hagemaster J: Ten criteria for evaluating qualitative research proposals. J Nurs Educ. 1987, 26: 138-143.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mays N, Pope C: Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ. 1995, 311: 109-12.

Medical Sociology Group: Criteria for the evaluation of qualitative research papers. Med Sociol News. 1996, 22: 68-71.

Alderson P: Listening to Children. 1995, London: Barnardo's

Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman D: Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in context. 2001, London: BMJ Publishing

Sandelowski M, Barroso J: Finding the findings in qualitative studies. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002, 34: 213-219. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00213.x.

Sandelowski M: Using qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2004, 14: 1366-1386. 10.1177/1049732304269672.

Thomas J, Brunton J: EPPI-Reviewer 3.0: Analysis and management of data for research synthesis. EPPI-Centre software. 2006, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education

Fisher M, Qureshi H, Hardyman W, Homewood J: Using Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews: Older people's views of hospital discharge. 2006, London: Social Care Institute for Excellence

Dixey R, Sahota P, Atwal S, Turner A: Children talking about healthy eating: data from focus groups with 300 9–11-year-olds. Nutr Bull. 2001, 26: 71-79. 10.1046/j.1467-3010.2001.00078.x.

Daly A, Willis K, Small R, Green J, Welch N, Kealy M, Hughes E: Hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007, 60: 43-49. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014.

Popay J: Moving beyond floccinaucinihilipilification: enhancing the utility of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005, 58: 1079-80. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.08.004.