share this!

August 16, 2021

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in

by Sara M Moniuszko

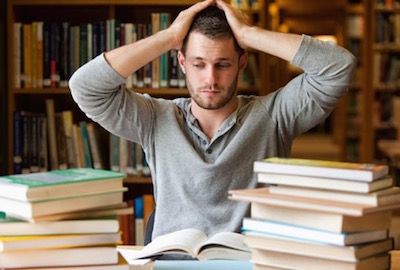

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide-range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas over workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework .

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy work loads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold, says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace, says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework causes, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high-achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school ," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely, but to be more mindful of the type of work students go home with, suggests Kang, who was a high-school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework, I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the last two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic, making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized... sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking assignments up can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

©2021 USA Today Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Nuclear rockets could travel to Mars in half the time, but designing the reactors that would power them isn't easy

12 hours ago

Limestone and iron reveal puzzling extreme rain in Western Australia 100,000 years ago

13 hours ago

Study of global primate populations reveals predictors of extinction risk

14 hours ago

Large radio bubble detected in galaxy NGC 4217

16 hours ago

Using AI to figure out the chemical composition of paints used in classical paintings

Phage cocktail shows promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Oct 4, 2024

Survey experiment reveals celebrities and politicians could be the 'missing link' to mitigate climate change

Innovative method targets removal of PFAS from wastewater

Solar flares may cause faint auroras across top of Northern Hemisphere

Better monitoring of mining remediation: Selenium isotopes are good gauge of clean-up efforts

Relevant physicsforums posts, how is physics taught without calculus.

Oct 2, 2024

Incandescent bulbs in teaching

Sep 27, 2024

Sources to study basic logic for precocious 10-year old?

How to explain ai to middle schoolers, how to explain bell's theorem to non-scientists.

Sep 19, 2024

Worksheets for Physics Experiments with Smartphones

More from STEM Educators and Teaching

Related Stories

Smartphones are lowering student's grades, study finds

Aug 18, 2020

Doing homework is associated with change in students' personality

Oct 6, 2017

Scholar suggests ways to craft more effective homework assignments

Oct 1, 2015

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Aug 29, 2019

How much math, science homework is too much?

Mar 23, 2015

Anxiety, depression, burnout rising as college students prepare to return to campus

Jul 26, 2021

Recommended for you

AI-generated college admissions essays tend to sound male and privileged, study finds

Learning mindset could be key to addressing medical students' alarming burnout

Researchers test ChatGPT, other AI models against real-world students

Sep 16, 2024

Virtual learning linked to rise in chronic absenteeism, study finds

Sep 5, 2024

AI tools like ChatGPT popular among students who struggle with concentration and attention

Aug 28, 2024

Researchers find academic equivalent of a Great Gatsby Curve in science mentorships

Aug 27, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School’s In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Credit: August de Richelieu

Does homework still have value? A Johns Hopkins education expert weighs in

Joyce epstein, co-director of the center on school, family, and community partnerships, discusses why homework is essential, how to maximize its benefit to learners, and what the 'no-homework' approach gets wrong.

By Vicky Hallett

The necessity of homework has been a subject of debate since at least as far back as the 1890s, according to Joyce L. Epstein , co-director of the Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships at Johns Hopkins University. "It's always been the case that parents, kids—and sometimes teachers, too—wonder if this is just busy work," Epstein says.

But after decades of researching how to improve schools, the professor in the Johns Hopkins School of Education remains certain that homework is essential—as long as the teachers have done their homework, too. The National Network of Partnership Schools , which she founded in 1995 to advise schools and districts on ways to improve comprehensive programs of family engagement, has developed hundreds of improved homework ideas through its Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program. For an English class, a student might interview a parent on popular hairstyles from their youth and write about the differences between then and now. Or for science class, a family could identify forms of matter over the dinner table, labeling foods as liquids or solids. These innovative and interactive assignments not only reinforce concepts from the classroom but also foster creativity, spark discussions, and boost student motivation.

"We're not trying to eliminate homework procedures, but expand and enrich them," says Epstein, who is packing this research into a forthcoming book on the purposes and designs of homework. In the meantime, the Hub couldn't wait to ask her some questions:

What kind of homework training do teachers typically get?

Future teachers and administrators really have little formal training on how to design homework before they assign it. This means that most just repeat what their teachers did, or they follow textbook suggestions at the end of units. For example, future teachers are well prepared to teach reading and literacy skills at each grade level, and they continue to learn to improve their teaching of reading in ongoing in-service education. By contrast, most receive little or no training on the purposes and designs of homework in reading or other subjects. It is really important for future teachers to receive systematic training to understand that they have the power, opportunity, and obligation to design homework with a purpose.

Why do students need more interactive homework?

If homework assignments are always the same—10 math problems, six sentences with spelling words—homework can get boring and some kids just stop doing their assignments, especially in the middle and high school years. When we've asked teachers what's the best homework you've ever had or designed, invariably we hear examples of talking with a parent or grandparent or peer to share ideas. To be clear, parents should never be asked to "teach" seventh grade science or any other subject. Rather, teachers set up the homework assignments so that the student is in charge. It's always the student's homework. But a good activity can engage parents in a fun, collaborative way. Our data show that with "good" assignments, more kids finish their work, more kids interact with a family partner, and more parents say, "I learned what's happening in the curriculum." It all works around what the youngsters are learning.

Is family engagement really that important?

At Hopkins, I am part of the Center for Social Organization of Schools , a research center that studies how to improve many aspects of education to help all students do their best in school. One thing my colleagues and I realized was that we needed to look deeply into family and community engagement. There were so few references to this topic when we started that we had to build the field of study. When children go to school, their families "attend" with them whether a teacher can "see" the parents or not. So, family engagement is ever-present in the life of a school.

My daughter's elementary school doesn't assign homework until third grade. What's your take on "no homework" policies?

There are some parents, writers, and commentators who have argued against homework, especially for very young children. They suggest that children should have time to play after school. This, of course is true, but many kindergarten kids are excited to have homework like their older siblings. If they give homework, most teachers of young children make assignments very short—often following an informal rule of 10 minutes per grade level. "No homework" does not guarantee that all students will spend their free time in productive and imaginative play.

Some researchers and critics have consistently misinterpreted research findings. They have argued that homework should be assigned only at the high school level where data point to a strong connection of doing assignments with higher student achievement . However, as we discussed, some students stop doing homework. This leads, statistically, to results showing that doing homework or spending more minutes on homework is linked to higher student achievement. If slow or struggling students are not doing their assignments, they contribute to—or cause—this "result."

Teachers need to design homework that even struggling students want to do because it is interesting. Just about all students at any age level react positively to good assignments and will tell you so.

Did COVID change how schools and parents view homework?

Within 24 hours of the day school doors closed in March 2020, just about every school and district in the country figured out that teachers had to talk to and work with students' parents. This was not the same as homeschooling—teachers were still working hard to provide daily lessons. But if a child was learning at home in the living room, parents were more aware of what they were doing in school. One of the silver linings of COVID was that teachers reported that they gained a better understanding of their students' families. We collected wonderfully creative examples of activities from members of the National Network of Partnership Schools. I'm thinking of one art activity where every child talked with a parent about something that made their family unique. Then they drew their finding on a snowflake and returned it to share in class. In math, students talked with a parent about something the family liked so much that they could represent it 100 times. Conversations about schoolwork at home was the point.

How did you create so many homework activities via the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program?

We had several projects with educators to help them design interactive assignments, not just "do the next three examples on page 38." Teachers worked in teams to create TIPS activities, and then we turned their work into a standard TIPS format in math, reading/language arts, and science for grades K-8. Any teacher can use or adapt our prototypes to match their curricula.

Overall, we know that if future teachers and practicing educators were prepared to design homework assignments to meet specific purposes—including but not limited to interactive activities—more students would benefit from the important experience of doing their homework. And more parents would, indeed, be partners in education.

Posted in Voices+Opinion

You might also like

News network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

Do Schools Give Out Too Much Homework Now? Yes, They Do, and it Needs to Stop

- By Emily Summers

- January 14, 2020

With more than 60% of students from high school and college seeking counseling for a variety of conditions ranging from general anxiety to clinical depression, all of which induced by school and studies, it’s safe to say that our country’s children are stressed out more than they should be. In fact, more and more students in the high school level are starting to report stress levels that rival that of adults working in officers, in some cases even exceeding those stress levels.

But what’s got them so riled up? The answer: Homework. Now, before you go full boomer and say “homework was more difficult back in my day!”, let’s make one thing clear: today’s educational system is far more advanced , complex, and even more difficult than it was a couple of decades ago.

Is There Too Much Homework in High School?

Of course, sometimes homework is necessary, but if it cuts into a child’s social, family, and down time, it borders on the cruel and unnecessary. Children should NOT be subjected to what-is-essentially training to be overworked in the corporate world. But how long does the average high school spend on homework? 3 hours a night. That’s 3 hours a night per class to complete, so it’s no wonder that our high school students are getting less than the National Sleep Foundation’s required 8 to 10 hours of sleep every night, with 68% of high school students reportedly getting less than 7 hours of sleep on the weekdays.

And that’s not even an exaggeration: in between a full day’s worth of school work, extracurricular activities, and homework, a high school student’s life is almost designed to be stressful. Sure, the point of all those activities is to turn them into an educated, well-balanced individual, but at what expense? A modern-day American student might know how to solve for X and throw a pigskin to the end zone, but what good is all of that if they’re haggard all the time and constantly deprived of sleep?

And what of the parents? It’s not like they can just leave their kids to the wolves: most parents (the responsible ones, at least) will want to help their kids with the influx of work they’ll be doing once they hit 9 th grade, as if a full day’s work and commuting wasn’t enough. All to fulfill antiquated ideas of course fulfillments and state-mandated credit requirement.

But rather than focusing on busy work, why not focus on things that actually matter , like fulfilling learning standards while maintaining positive mental health?

Educators across the country need to rethink homework, why they need to give it and what kind of work they should be giving our children.

Is Homework Even Necessary?

With the amount of stress students go through, it’s tempting to curse the person who invented homework . But take note: it’s not all bad.

Homework now can seem like unnecessary busy work instead of actual learning materials, but before we get further into this topic, let’s be clear: some homework is necessary (although researchers are still waiting for conclusive evidence for homework’s necessity).

What researchers can agree on, however, is that any type of school work that is purposeful, appropriately challenging, and aligned with the student’s interest truly is beneficial: not only does it teach the lesson for that subject, it also improves study habits, establishes self-discipline, and develops independent problem-solving skills and critical thinking.

However, if homework is mind-numbingly tedious, without purpose (other than to fulfill a quota), and overwhelming, then it becomes detrimental: not only will it demotivate a student from learning, it can also affect the way they view school, negatively affect their learning retention, and eventually turn them off completely to that subject.

Unfortunately, many schools across the country use homework as a way of creating extra class time beyond what is mandated by the state. Not only is this inefficient, it’s needlessly cruel. If a teacher is using homework as an excuse to make your child do their job for them, you need to contact your child’s school and set up a meeting. Homework should be a tool that supplements lessons, not replace lessons as a whole.

How Can We Make Homework Better?

The National PTA suggests that high school students should have a maximum of 2 hours of homework per night , a far cry from cramming 18 hours’ worth of schoolwork into 4-5 hours after school. We can do better by demanding that schools revisit their requirements for students and reconsider lessening the amount of required homework they give students.

As for the teachers, it’s time to treat homework not as busywork but as actual tools to help students learn more about your subject. It doesn’t have to be fun per se, but it should be inspiring enough for your students to take a more active role in your class the next day. Homework should stoke the fires of creativity and instill a spirit of inquisitiveness; homework shouldn’t be a chore that students dread doing, nor should it be an impossible activity designed to confuse them or punish them.

Homework should include activities that reinforce what they learned throughout the class and not something that combines lessons for the next day with activities designed to test what they’ve learned on their own. Not only is that tedious and inefficient, it’s also a lazy way to teach.

For parents, get a better idea of what your child is going through by taking the time to sit down with them to listen to their concerns . Keep an open mind and avoid being dismissive; this is the best way for your teenage child to open up and is an opportunity for them to practice critical communication skills with people they can trust (i.e. their parents).

About the Author

Emily summers.

10 Careers to Pursue After High School if Youre a People Person

How Summer Camp Fosters Social Skills

6 reasons to read to your child regularly at home

Things to Know About Developmental Disability Services

Is the D Important in Pharmacy? Why Pharm.D or RPh Degrees Shouldn’t Matter

How to Email a Professor: Guide on How to Start and End an Email Conversation

Everything You Need to Know About Getting a Post-Secondary Education

Grammar Corner: What’s The Difference Between Analysis vs Analyses?

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Your content has been saved!

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

Overloading students with too much homework takes a toll on their mental health

By Angelina Halas October 15, 2019

Not all professors always take into consideration what students have going on outside the classroom and what they might be experiencing personally. This may affect their ability to excel with their assignments, inside and outside of class.

A study from Psychology Today found that 44.2 percent of college students named academics to be something traumatic in their life or something too hard to handle.

The site states “that number is 10 percent higher than any other stressor, including problems with finances or intimate relationships.”

Sophomore biology major Ash Angus finds that academics is a big stressor in her life, as professors don’t take into consideration what students have going on outside the classroom, like familial pressure.

“With parents, especially if your parents are not from America, they have very high expectations of you and they want you to aim higher and higher in life because they weren’t given the same opportunities that you were,” Angus said.

She continued on to explain her belief that professors don’t consider that students have other obligations than just classwork.

According to the American Psychology Association , 41.6 percent of college students have anxiety and 36.4 percent have depression. Angus believes that this could easily be linked to not having a good life balance of school work and outside activities.

“It is dependent on your major, but I feel like most professors pile on a lot of work,” she said. “They don’t even think about the other responsibilities you have like a job, other classes or clubs, a social life and trying to take care of your own mental health.”

Marianne Stenger , a freelance writer and journalist, found in a study that only six percent of college students find their homework to be useful in terms of preparation for tests, quizzes and projects.

Angus feels that she has no time to rest and has been only getting four or five hours of sleep because she’s always up doing homework.

Psychology professor Dr. Maya Gordon admits that she thinks about what students have going on outside the classroom and tries to give reasonable time and due dates, but she tends to think about it more when students come up to her individually.

“Just communicate with me,” Gordon said. “I understand things happen for whatever reason so just let me know. I know students juggle a lot.”

Gordon continued to explain that she presents herself in the classroom in a way that she hopes students feel encouraged to come to her if they are struggling. She also said that if she notices something is incomplete, she will reach out to that student herself to make sure everything is okay.

Gordon admits that because she is a psychologist, she might be more in tune to what students are internalizing and their emotional needs, so she structures her work around that.

“I don’t want students to have an assignment that stresses them and keeps them up at night,” Gordon said. “I don’t want them to not do their best work because they are stressed out.”

Gordon points out that she believes school should be fun and something exciting, not something that stresses students out.

“I don’t want work to take a toll on the health of a student,” she said. “That just takes away the value of an education.”

Gordon explains that within the Cabrini staff, there are a mix of teachers and some are not like her.

“Some professors aren’t as in tune into emotional states or pay as much attention. I think that’s because sometimes they forget, they’re so far removed from when they were a student. They forget what it’s like to be on the other side,” Gordon said.

Despite Gordon acknowledging students responsibilities outside the classroom, she does say that it’s up to the students to let her know if something needs to be changed to help them out.

“I don’t know if you don’t tell me. Just touch base with me. I have no problem adjusting the syllabus or getting rid of the textbook if it’s not helpful. But I only know that if students tell me,” she said.

Italian professor Tiziana Murray is on the same side as Gordon, accepting what students have going on outside of class when it comes to distributing homework.

“I give my students a whole week to do homework. I’m not very strict with the due dates,” Murray said.

Murray is also open to students coming to her if they need help. She said that now she has a more open schedule which allows for students to come see her more, whether that’s for an academic reason or just for support.

She continues to explain that she has a constant connection with her students because she’s always available through email and she will also reach out through there if it’s needed.

In her class, she gives students ways to deal with stress, along with supplying a PowerPoint.

“I want to be there for the mental and the physical support,” Murray said.

She allows for student feedback by asking them in class how they felt about the quizzes and the tests assigned.

“I’m open to change. Students should feel comfortable coming to me because I’m flexible enough. I will support a student if they want to be supported,” she said.

Even though professors are trying to accommodate with student’s mental health and outside activities, not all students know that the option is there to speak up and ask for help.

“They don’t take into consideration what I have going on unless I go to them first and talk to them about it,” Angus said. “I feel like they see you as just a student rather than a whole person. They see you as just a student with your letter grade or your GPA rather than a human being.”

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Angelina Halas

Click here to check out our latest edition!

Perspectives

A final reflection, growing up cabrini, eleven minds, one mission, special project, title ix redefined website, season 2, episode 3: celebrating cabrini and digging into its past.

- More Networks

Sport and Competition

Is too much homework unhealthy, a grassroots movement led by parents is backed by science..

Posted October 10, 2014

This is the question at the heart of the homework debate. The Washington Post education reporter Jay Mathews wrote a powerful article: “ Parents Saying No to Too Much Homework .” The story was inspired by a chapter in the new book, The Learning Habit: A Groundbreaking Approach to Homework and Parenting That Helps Our Children Succeed in School and Life . (Perigee, 2014)

The Learning Habit separates fact from fiction about homework and has started a grassroots movement led by parents. Instead of encouraging a homework revolt, it asks for parents to institute a regular, balanced homework routine . This includes having children stop doing academic homework after a reasonable amount of time. When children can’t understand the assignment, parents will not make the children sit for extended time and try to help them figure it out; they will write a note on the paper asking the teacher for extra help.

At the root of the movement is science. It’s not developmentally appropriate to ask a third grader to sit for 120 minutes and complete an academic assignment. It’s also not psychologically healthy to have a fourth grader in tears every night over homework. The focus on a "the whole child" approach is resonating with parents and administrators in school districts such as Barrington, Rhode Island.

So how much academic homework should a child have?

10 minutes per grade in school, and then children can move onto other activities. If they don’t understand the assignment or get frustrated, they should stop and read a book for the remaining time.

The facts are clear when it comes to academic homework . There is a point of diminishing returns, and it is anything over 10 minutes per grade. We now understand that the concept of “homework” involves balancing many opportunities that provide our kids with healthy learning experiences.. Activities such as neighborhood play, sports, dancing, family time, chores, and sleeping are equally important for whole-child enrichment. Additionally, children who participate in extra-curricular activities such as sports, dance, and clubs score higher on academic, social and emotional scales.

- All students work at a different pace.

- Think big picture. Forcing a child to complete a homework assignment, after they have spent a reasonable amount of time on it (10 minutes per grade), is not promoting balance.

- Keep academic homework time balanced and consistent. On nights children don’t have schoolwork, they will read. Reading is important for both ELA and Mathematics.

- No tears policy: When kids feel frustrated or don’t understand an academic assignment, they can choose to read a book instead and ask the teacher for extra help the next day.

GET THE FACTS ON HOMEWORK: Fact Sheet Balanced Homework Habit

For more information on The Learning Habit (Perigee) click HERE

Rebecca Jackson is a neuropsychological educator and the co-author of The Learning Habit

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

| |

- 10 Top Tips

- Better Meetings

- Get Organized

- GYWD E-Book

- Plan Your Week

- Time at Work

- Using Email

- College Q & A

- Messy Desk?

- Procrastination

- Study Success

- Time for Teachers

- GMTS! Ebook

- Why it Matters

- Activities to Try

- Daily Planners

- Essential Tools

- Set Your Goals

- Use a System

- Work Life Balance

- Bang for Buck

- Best Strategies

- Do What Matters

- Expert Interviews

- More Articles...

Too Much Homework? Here’s What To Do

Whatever their age , most students complain that they have too much homework.

But is that really the case?

Over the last 20 years as a teacher, I’ve heard all sorts of excuses about why homework hasn’t been done.

In years gone by, a household pet was often blamed for eating it. Now it’s the ubiquitous ‘faulty printer’ that seems to prevent homework coming in on time. :)

Of course, there are also plenty of valid reasons for not getting it done.

Sometimes there genuinely is too much homework to do in the time allocated.

Many students struggle to do what’s asked of them for want of somewhere quiet to work, or because they have too many other commitments that can’t be avoided.

But it’s also true that virtually everyone could reduce the stress associated with homework by applying some simple time management skills.

What 'Too Much Homework' Really Means

Each time we get given work to do with a deadline, our ability to manage time is tested. This can take many forms, but the bottom line is simply that...

Work didn’t get done because other things took priority.

Something else was more important, more appealing or just plain easier to do. Homework gets left until, all of a sudden, there is too much to do in not enough time.

The good news is that time management skills can always be learnt and improved. There are plenty of tips and techniques for overcoming procrastination on this site, but the following ideas may also be helpful if you feel you have too much homework.

7 Tips For Coping With Too Much Homework

1. Accept it

The starting point for dealing with too much homework is to accept responsibility for getting it done. It’s yours to do, and yours alone.

Let’s be honest. For most people, homework is a chore. Until there’s a massive change in attitudes towards home learning, it’s here to stay.

With that in mind, the best thing is to adopt a positive ‘get it done’ attitude. If you accept that it has to be done (rather than the consequences of not doing it), you only have to decide when and how to do it.

2. Write it down

This may seem an obvious point, but writing down exactly what you have to do and when you have to do it for is an important step to take for getting organized with homework.

Use a simple planner and keep it open at the current page you’re using so that you can remind yourself what you need to do.

3. C reate a workspace

Not everyone has somewhere to work. If you do, how easy is it to use?

Whether it’s a kitchen table or a place in your own room, you’ll do more if you've got somewhere that you can use regularly. You’ll do even better if you tidy up a messy desk .

Make sure you’ve got everything that you need to hand so you can find it quickly when you want it. Get into the habit of putting things back after you’ve used them.

4. Do it the day after you get it

This is a great way to stay on top of your work. The temptation is to leave things until the last minute because that’s when doing it really matters.

Unfortunately, that’s also when it is most stressful, and there’s no margin for error.

Next time you get given a project, assignment or piece of work, start it on the day after you get it. You don’t have to finish it; just do as much as you feel like doing.

Whatever you don’t get done, you carry on with the next day.

This ‘little and often’ approach has three benefits:

- You have a day to ‘relax’ before you start it

- You do it without feeling overwhelmed because you can stop whenever you feel like it.

- More work will get done before the day it’s due to be handed in

5. Think 80-20 - don’t do it too well

The 80-20 rule states that, in life, we get 80% of our results from 20% of what we do.

This is really useful if you feel you have too much homework. Why? Well, it could be that you are doing some things too well.

Obviously some things are either done or they’re not. But often, it’s easy to spend too long on something just with very little to show for your efforts.

I’m not saying that you should produce poor quality work. But do be aware of perfectionism. Try to get better at knowing when your absolute best effort really is necessary, and when good enough is good enough.

6. Reduce your resistance to doing it

Sometimes, ‘too much homework’ means " I’ve left it too late, and now I’ve got too much to do ".

This can be avoided if you start it the day after you get it. And the best way to do that? Make it as easy as you need to.

Can’t face all of it? Time box half an hour. Or 10 minutes. Even 2 minutes if that’s all you can cope with.

How much you do is less important than the fact that you actually do something.

7. When you do it, give it 100% attention

Phones, friends and social media will stretch out the time you spend working. We all have to be aware of wasting time online , so the less you do it, the quicker you can complete your work.

The amount of homework you have varies from week to week, but the tips above may just be the answer. If so, you’ll have learned some valuable skills and turned too much homework into a manageable amount.

Having said that, it can get to the point at which you feel that there really is too much to do, and not just at the moment. If and when you reach the point at which, despite your best efforts, you consistently feel you have too much homework, tell someone.

They say a problem shared is a problem halved, and it’s true. Talking to someone will help. Talking to someone who is in a position to help you do something about it is even better.

In terms of getting things done, developing good study habits can make a massive difference, but sometimes there’s just too much to do. This can be a real problem unless you tell someone, so don’t keep it inside -- get some support.

Do you need to get a better balance in your life? Click below to check out the Time Management Success e-book!

- Good Study Habits

- Too Much Homework

Copyright © 2009-2024 Time Management Success. All Rights Reserved.

Time Management Success does not collect or sell personal information from visitors.

Privacy Policy

Shop TODAY-exclusive savings on an 8-in-1 cooker, Clarks boots, more fall finds

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

- TODAY Plaza

Too much homework: Is it reality or a myth?

How long do your kids spend each night hitting the books? If they are complaining about being buried by a growing mountain of homework, not so fast.

A report from the Brookings Institution released Tuesday suggests that despite stories about stressed out kids having too much homework, the amount has not changed much in 30 years and rarely tops more than two hours a night.

"It still doesn't look like kids are overworked," researcher Tom Loveless, a former math teacher who conducted the study, told USA Today . "The percentage who are overworked is really small."

The TODAY anchors weighed in Tuesday, with Matt Lauer and Carson Daly saying they don’t quite remember being overburdened.

“I don’t remember doing two hours of homework a night,” Lauer said. “Me neither,” Daly added.

Natalie Morales said she thinks homework loads vary by school, and added, “I think nowadays, kids are on their devices.”

In the report, “Homework In America, ” Loveless analyzed several previous surveys, including the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Kids ages 9, 13 and 17 were asked how much time they spent on homework a day earlier.

For the 17-year-olds, the percentage of kids doing the most homework — more than two hours a night — stayed the same at 13 percent from 1984 to 2012. The percentage spending one to two hours a night dropped from 27 percent to 23 percent in that time period and the kids who did less than an hour — 26 percent — was the same as well.

The percentage of 13-year-olds with the heaviest workload, more than two hours, dropped from 9 percent to 7 percent in 2012, and those spending one to two hours on homework also went down.

TODAY’s Savannah Guthrie said she thought it was the younger kids who have been getting more homework lately. “Isn’t the complaint that it’s the little kids, the little ones in elementary school who have homework until 10 at night?

The Brookings report concluded that “the homework load has remained remarkably stable since 1984,” with one exception: 9-year-olds.

The percentage of 9-year-olds with no homework fell from 35 percent in 1984 to 22 percent in 2012, while the percentage of those doing less than an hour rose from 41 percent o 57 percent in the same time period.

Lauer said his elementary school-aged kids spend 45 minutes to an hour on homework.

Another survey, by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that the percentage of college freshmen who recalled having at least six hours a week of homework during their last year of high school dropped from 50 percent in 1986 to 38 percent in 2012, USA Today said.

The Brookings report comes as some parents have complained about their kids being stressed out from too much homework. Some district are considering time limits on homework or making homework optional.

The report noted that major magazines ran cover stories on the evils of homework from 1998 until 2003. More recently, it noted a 2011 front-page New York Times story about the nightly homework grind stressing out kids and an article in The Atlantic in September headlined “My Daughter’s Homework Is Killing Me,” that describes a man doing his daughter’s homework every night for a week.

The Brookings report says most parents think their kids are getting the right amount of homework, and that “homework horror stories” need proper perspective.

“They seem to originate from the very personal discontents of a small group of parents,” the report said. “They do not reflect the experience of the average family with a school-age child.”

Mike Petrilli of the education think tank Thomas B. Fordham Institute said the amount of homework varies for different kinds of students. Those hoping to attend elite colleges "probably are doing too much homework and are stressed out about it," he told USA Today.

But the rest of the students, he said, "are not being pushed to do a lot of homework at all."

Is homework a necessary evil?

After decades of debate, researchers are still sorting out the truth about homework’s pros and cons. One point they can agree on: Quality assignments matter.

By Kirsten Weir

March 2016, Vol 47, No. 3

Print version: page 36

- Schools and Classrooms

Homework battles have raged for decades. For as long as kids have been whining about doing their homework, parents and education reformers have complained that homework's benefits are dubious. Meanwhile many teachers argue that take-home lessons are key to helping students learn. Now, as schools are shifting to the new (and hotly debated) Common Core curriculum standards, educators, administrators and researchers are turning a fresh eye toward the question of homework's value.

But when it comes to deciphering the research literature on the subject, homework is anything but an open book.

The 10-minute rule

In many ways, homework seems like common sense. Spend more time practicing multiplication or studying Spanish vocabulary and you should get better at math or Spanish. But it may not be that simple.

Homework can indeed produce academic benefits, such as increased understanding and retention of the material, says Duke University social psychologist Harris Cooper, PhD, one of the nation's leading homework researchers. But not all students benefit. In a review of studies published from 1987 to 2003, Cooper and his colleagues found that homework was linked to better test scores in high school and, to a lesser degree, in middle school. Yet they found only faint evidence that homework provided academic benefit in elementary school ( Review of Educational Research , 2006).

Then again, test scores aren't everything. Homework proponents also cite the nonacademic advantages it might confer, such as the development of personal responsibility, good study habits and time-management skills. But as to hard evidence of those benefits, "the jury is still out," says Mollie Galloway, PhD, associate professor of educational leadership at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. "I think there's a focus on assigning homework because [teachers] think it has these positive outcomes for study skills and habits. But we don't know for sure that's the case."

Even when homework is helpful, there can be too much of a good thing. "There is a limit to how much kids can benefit from home study," Cooper says. He agrees with an oft-cited rule of thumb that students should do no more than 10 minutes a night per grade level — from about 10 minutes in first grade up to a maximum of about two hours in high school. Both the National Education Association and National Parent Teacher Association support that limit.

Beyond that point, kids don't absorb much useful information, Cooper says. In fact, too much homework can do more harm than good. Researchers have cited drawbacks, including boredom and burnout toward academic material, less time for family and extracurricular activities, lack of sleep and increased stress.

In a recent study of Spanish students, Rubén Fernández-Alonso, PhD, and colleagues found that students who were regularly assigned math and science homework scored higher on standardized tests. But when kids reported having more than 90 to 100 minutes of homework per day, scores declined ( Journal of Educational Psychology , 2015).

"At all grade levels, doing other things after school can have positive effects," Cooper says. "To the extent that homework denies access to other leisure and community activities, it's not serving the child's best interest."

Children of all ages need down time in order to thrive, says Denise Pope, PhD, a professor of education at Stanford University and a co-founder of Challenge Success, a program that partners with secondary schools to implement policies that improve students' academic engagement and well-being.

"Little kids and big kids need unstructured time for play each day," she says. Certainly, time for physical activity is important for kids' health and well-being. But even time spent on social media can help give busy kids' brains a break, she says.

All over the map

But are teachers sticking to the 10-minute rule? Studies attempting to quantify time spent on homework are all over the map, in part because of wide variations in methodology, Pope says.

A 2014 report by the Brookings Institution examined the question of homework, comparing data from a variety of sources. That report cited findings from a 2012 survey of first-year college students in which 38.4 percent reported spending six hours or more per week on homework during their last year of high school. That was down from 49.5 percent in 1986 ( The Brown Center Report on American Education , 2014).

The Brookings report also explored survey data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which asked 9-, 13- and 17-year-old students how much homework they'd done the previous night. They found that between 1984 and 2012, there was a slight increase in homework for 9-year-olds, but homework amounts for 13- and 17-year-olds stayed roughly the same, or even decreased slightly.

Yet other evidence suggests that some kids might be taking home much more work than they can handle. Robert Pressman, PhD, and colleagues recently investigated the 10-minute rule among more than 1,100 students, and found that elementary-school kids were receiving up to three times as much homework as recommended. As homework load increased, so did family stress, the researchers found ( American Journal of Family Therapy , 2015).

Many high school students also seem to be exceeding the recommended amounts of homework. Pope and Galloway recently surveyed more than 4,300 students from 10 high-achieving high schools. Students reported bringing home an average of just over three hours of homework nightly ( Journal of Experiential Education , 2013).

On the positive side, students who spent more time on homework in that study did report being more behaviorally engaged in school — for instance, giving more effort and paying more attention in class, Galloway says. But they were not more invested in the homework itself. They also reported greater academic stress and less time to balance family, friends and extracurricular activities. They experienced more physical health problems as well, such as headaches, stomach troubles and sleep deprivation. "Three hours per night is too much," Galloway says.

In the high-achieving schools Pope and Galloway studied, more than 90 percent of the students go on to college. There's often intense pressure to succeed academically, from both parents and peers. On top of that, kids in these communities are often overloaded with extracurricular activities, including sports and clubs. "They're very busy," Pope says. "Some kids have up to 40 hours a week — a full-time job's worth — of extracurricular activities." And homework is yet one more commitment on top of all the others.

"Homework has perennially acted as a source of stress for students, so that piece of it is not new," Galloway says. "But especially in upper-middle-class communities, where the focus is on getting ahead, I think the pressure on students has been ratcheted up."

Yet homework can be a problem at the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum as well. Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, Internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs, says Lea Theodore, PhD, a professor of school psychology at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. They are less likely to have computers or a quiet place to do homework in peace.

"Homework can highlight those inequities," she says.

Quantity vs. quality

One point researchers agree on is that for all students, homework quality matters. But too many kids are feeling a lack of engagement with their take-home assignments, many experts say. In Pope and Galloway's research, only 20 percent to 30 percent of students said they felt their homework was useful or meaningful.

"Students are assigned a lot of busywork. They're naming it as a primary stressor, but they don't feel it's supporting their learning," Galloway says.

"Homework that's busywork is not good for anyone," Cooper agrees. Still, he says, different subjects call for different kinds of assignments. "Things like vocabulary and spelling are learned through practice. Other kinds of courses require more integration of material and drawing on different skills."

But critics say those skills can be developed with many fewer hours of homework each week. Why assign 50 math problems, Pope asks, when 10 would be just as constructive? One Advanced Placement biology teacher she worked with through Challenge Success experimented with cutting his homework assignments by a third, and then by half. "Test scores didn't go down," she says. "You can have a rigorous course and not have a crazy homework load."

Still, changing the culture of homework won't be easy. Teachers-to-be get little instruction in homework during their training, Pope says. And despite some vocal parents arguing that kids bring home too much homework, many others get nervous if they think their child doesn't have enough. "Teachers feel pressured to give homework because parents expect it to come home," says Galloway. "When it doesn't, there's this idea that the school might not be doing its job."

Galloway argues teachers and school administrators need to set clear goals when it comes to homework — and parents and students should be in on the discussion, too. "It should be a broader conversation within the community, asking what's the purpose of homework? Why are we giving it? Who is it serving? Who is it not serving?"

Until schools and communities agree to take a hard look at those questions, those backpacks full of take-home assignments will probably keep stirring up more feelings than facts.

Further reading

- Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001

- Galloway, M., Connor, J., & Pope, D. (2013). Nonacademic effects of homework in privileged, high-performing high schools. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81 (4), 490–510. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2012.745469

- Pope, D., Brown, M., & Miles, S. (2015). Overloaded and underprepared: Strategies for stronger schools and healthy, successful kids . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

- Visit Campus

- Request Information

5 Tips for Dealing with “Too Much” Homework

In the case of unreasonable “commitments,” you’re procrastinating doing your homework, but of course, there are people who genuinely are overwhelmed by their homework. With that in mind, how do you manage your time to get it all done? The following are five tips for any student (current or prospective) who’s struggling with getting their workload completed on time.

1. Don’t be a perfectionist

There’s an old principle of Pareto’s that’s been adapted to business (specifically management) called the 80-20 rule. The idea is that 80% of your results, come from 20% of your efforts. Think about that. When you tackle an assignment for school, are you trying to make everything perfect? Remember that you’re a student, no one is expecting you to be perfect, you’re in school to get better; you’re supposed to be a work in progress.

As a result, what may feel like “too much” homework, might really be you tackling assignments “too well.” For instance, there’s a reason “speed reading” is a skill that’s encouraged. A textbook is not a work of literature where every sentence means something, it’s okay to skim or, in some cases, skip whole paragraphs – the last paragraph just recaps what you read anyway.

Moreover, many schools or classes curve their grades. So an 80% could be a 100% in your class.

2. Do your homework as soon as it’s assigned to you

Due to the nature of college schedules, students often have classes MWF and different classes on Tuesday and Thursday. As a result, they do their MWF homework on Sunday, Tuesday and Thursday in preparation for the following day. Rather than do that. Do your Monday homework, Monday; Tuesday homework, Tuesday; Wednesday homework, Wednesday and so on.

The reason for this is manifold. First of all, the class and the assignment are fresh in your mind – this is especially critical for anything math related to those who are less math-minded. So do the assignment after the class. Chances are, it’ll be much easier to complete.

The second reason is because if you have a question about Monday’s homework and you’re working on it on Monday night, then guess what? You can contact your professor (or a friend) Tuesday for help or clarification. Whereas if you’re completing Monday’s homework on a Tuesday night, you’re out of luck. This can assuage a lot of the stress that comes from too much homework.

This flows into the third reason which is that, rather than having a chunk of homework to do the day before its due, you’re doing a little at a time frequently. This is a basic time management tactic where, if you finish tasks as they’re assigned instead of letting them pile up, you avoid that mental blockade of feeling like there’s “too much” for you to do in the finite amount of time given.

3. Eliminate distractions

All too often, students sit down to do homework and then receive a text, and then another, and then hop on Facebook, and then comment on something, and then take a break. Before they’re aware of it, hours have passed.