We need your support today

Independent journalism is more important than ever. Vox is here to explain this unprecedented election cycle and help you understand the larger stakes. We will break down where the candidates stand on major issues, from economic policy to immigration, foreign policy, criminal justice, and abortion. We’ll answer your biggest questions, and we’ll explain what matters — and why. This timely and essential task, however, is expensive to produce.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

5 moving, beautiful essays about death and dying

by Sarah Kliff

It is never easy to contemplate the end-of-life, whether its own our experience or that of a loved one.

This has made a recent swath of beautiful essays a surprise. In different publications over the past few weeks, I’ve stumbled upon writers who were contemplating final days. These are, no doubt, hard stories to read. I had to take breaks as I read about Paul Kalanithi’s experience facing metastatic lung cancer while parenting a toddler, and was devastated as I followed Liz Lopatto’s contemplations on how to give her ailing cat the best death possible. But I also learned so much from reading these essays, too, about what it means to have a good death versus a difficult end from those forced to grapple with the issue. These are four stories that have stood out to me recently, alongside one essay from a few years ago that sticks with me today.

My Own Life | Oliver Sacks

As recently as last month, popular author and neurologist Oliver Sacks was in great health, even swimming a mile every day. Then, everything changed: the 81-year-old was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. In a beautiful op-ed , published in late February in the New York Times, he describes his state of mind and how he’ll face his final moments. What I liked about this essay is how Sacks describes how his world view shifts as he sees his time on earth getting shorter, and how he thinks about the value of his time.

Before I go | Paul Kalanithi

Kalanthi began noticing symptoms — “weight loss, fevers, night sweats, unremitting back pain, cough” — during his sixth year of residency as a neurologist at Stanford. A CT scan revealed metastatic lung cancer. Kalanthi writes about his daughter, Cady and how he “probably won’t live long enough for her to have a memory of me.” Much of his essay focuses on an interesting discussion of time, how it’s become a double-edged sword. Each day, he sees his daughter grow older, a joy. But every day is also one that brings him closer to his likely death from cancer.

As I lay dying | Laurie Becklund

Becklund’s essay was published posthumonously after her death on February 8 of this year. One of the unique issues she grapples with is how to discuss her terminal diagnosis with others and the challenge of not becoming defined by a disease. “Who would ever sign another book contract with a dying woman?” she writes. “Or remember Laurie Becklund, valedictorian, Fulbright scholar, former Times staff writer who exposed the Salvadoran death squads and helped The Times win a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the 1992 L.A. riots? More important, and more honest, who would ever again look at me just as Laurie?”

Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat | Liz Lopatto

Dorothy Parker was Lopatto’s cat, a stray adopted from a local vet. And Dorothy Parker, known mostly as Dottie, died peacefully when she passed away earlier this month. Lopatto’s essay is, in part, about what she learned about end-of-life care for humans from her cat. But perhaps more than that, it’s also about the limitations of how much her experience caring for a pet can transfer to caring for another person.

Yes, Lopatto’s essay is about a cat rather than a human being. No, it does not make it any easier to read. She describes in searing detail about the experience of caring for another being at the end of life. “Dottie used to weigh almost 20 pounds; she now weighs six,” Lopatto writes. “My vet is right about Dottie being close to death, that it’s probably a matter of weeks rather than months.”

Letting Go | Atul Gawande

“Letting Go” is a beautiful, difficult true story of death. You know from the very first sentence — “Sara Thomas Monopoli was pregnant with her first child when her doctors learned that she was going to die” — that it is going to be tragic. This story has long been one of my favorite pieces of health care journalism because it grapples so starkly with the difficult realities of end-of-life care.

In the story, Monopoli is diagnosed with stage four lung cancer, a surprise for a non-smoking young woman. It’s a devastating death sentence: doctors know that lung cancer that advanced is terminal. Gawande knew this too — Monpoli was his patient. But actually discussing this fact with a young patient with a newborn baby seemed impossible.

"Having any sort of discussion where you begin to say, 'look you probably only have a few months to live. How do we make the best of that time without giving up on the options that you have?' That was a conversation I wasn't ready to have," Gawande recounts of the case in a new Frontline documentary .

What’s tragic about Monopoli’s case was, of course, her death at an early age, in her 30s. But the tragedy that Gawande hones in on — the type of tragedy we talk about much less — is how terribly Monopoli’s last days played out.

- Health Care

Most Popular

- A thousand pigs just burned alive in a barn fire

- Who is Ryan Wesley Routh? The suspect in the Trump Florida assassination attempt, explained.

- Sign up for Vox’s daily newsletter

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

- The new followup to ChatGPT is scarily good at deception

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Politics

The US has often singled out Haitian immigrants. GOP attacks are the latest example.

Republicans know exactly what they’re doing.

Trump’s increasingly close ties to the “proud Islamophobe” expose some ugly truths his allies would rather keep hidden.

If the race to stop a spill in the Red Sea fails, it would be one of the worst in history.

The right thinks that hot girls can “kill woke.” What?

The industry is spending huge sums of cash to convince everyone it’s not a flop.

May 3, 2023

Contemplating Mortality: Powerful Essays on Death and Inspiring Perspectives

The prospect of death may be unsettling, but it also holds a deep fascination for many of us. If you're curious to explore the many facets of mortality, from the scientific to the spiritual, our article is the perfect place to start. With expert guidance and a wealth of inspiration, we'll help you write an essay that engages and enlightens readers on one of life's most enduring mysteries!

Death is a universal human experience that we all must face at some point in our lives. While it can be difficult to contemplate mortality, reflecting on death and loss can offer inspiring perspectives on the nature of life and the importance of living in the present moment. In this collection of powerful essays about death, we explore profound writings that delve into the human experience of coping with death, grief, acceptance, and philosophical reflections on mortality.

Through these essays, readers can gain insight into different perspectives on death and how we can cope with it. From personal accounts of loss to philosophical reflections on the meaning of life, these essays offer a diverse range of perspectives that will inspire and challenge readers to contemplate their mortality.

The Inevitable: Coping with Mortality and Grief

Mortality is a reality that we all have to face, and it is something that we cannot avoid. While we may all wish to live forever, the truth is that we will all eventually pass away. In this article, we will explore different aspects of coping with mortality and grief, including understanding the grieving process, dealing with the fear of death, finding meaning in life, and seeking support.

Understanding the Grieving Process

Grief is a natural and normal response to loss. It is a process that we all go through when we lose someone or something important to us. The grieving process can be different for each person and can take different amounts of time. Some common stages of grief include denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. It is important to remember that there is no right or wrong way to grieve and that it is a personal process.

Denial is often the first stage of grief. It is a natural response to shock and disbelief. During this stage, we may refuse to believe that our loved one has passed away or that we are facing our mortality.

Anger is a common stage of grief. It can manifest as feelings of frustration, resentment, and even rage. It is important to allow yourself to feel angry and to express your emotions healthily.

Bargaining is often the stage of grief where we try to make deals with a higher power or the universe in an attempt to avoid our grief or loss. We may make promises or ask for help in exchange for something else.

Depression is a natural response to loss. It is important to allow yourself to feel sad and to seek support from others.

Acceptance is often the final stage of grief. It is when we come to terms with our loss and begin to move forward with our lives.

Dealing with the Fear of Death

The fear of death is a natural response to the realization of our mortality. It is important to acknowledge and accept our fear of death but also to not let it control our lives. Here are some ways to deal with the fear of death:

Accepting Mortality

Accepting our mortality is an important step in dealing with the fear of death. We must understand that death is a natural part of life and that it is something that we cannot avoid.

Finding Meaning in Life

Finding meaning in life can help us cope with the fear of death. It is important to pursue activities and goals that are meaningful and fulfilling to us.

Seeking Support

Seeking support from friends, family, or a therapist can help us cope with the fear of death. Talking about our fears and feelings can help us process them and move forward.

Finding meaning in life is important in coping with mortality and grief. It can help us find purpose and fulfillment, even in difficult times. Here are some ways to find meaning in life:

Pursuing Passions

Pursuing our passions and interests can help us find meaning and purpose in life. It is important to do things that we enjoy and that give us a sense of accomplishment.

Helping Others

Helping others can give us a sense of purpose and fulfillment. It can also help us feel connected to others and make a positive impact on the world.

Making Connections

Making connections with others is important in finding meaning in life. It is important to build relationships and connections with people who share our values and interests.

Seeking support is crucial when coping with mortality and grief. Here are some ways to seek support:

Talking to Friends and Family

Talking to friends and family members can provide us with a sense of comfort and support. It is important to express our feelings and emotions to those we trust.

Joining a Support Group

Joining a support group can help us connect with others who are going through similar experiences. It can provide us with a safe space to share our feelings and find support.

Seeking Professional Help

Seeking help from a therapist or counselor can help cope with grief and mortality. A mental health professional can provide us with the tools and support we need to process our emotions and move forward.

Coping with mortality and grief is a natural part of life. It is important to understand that grief is a personal process that may take time to work through. Finding meaning in life, dealing with the fear of death, and seeking support are all important ways to cope with mortality and grief. Remember to take care of yourself, allow yourself to feel your emotions, and seek support when needed.

The Ethics of Death: A Philosophical Exploration

Death is an inevitable part of life, and it is something that we will all experience at some point. It is a topic that has fascinated philosophers for centuries, and it continues to be debated to this day. In this article, we will explore the ethics of death from a philosophical perspective, considering questions such as what it means to die, the morality of assisted suicide, and the meaning of life in the face of death.

Death is a topic that elicits a wide range of emotions, from fear and sadness to acceptance and peace. Philosophers have long been interested in exploring the ethical implications of death, and in this article, we will delve into some of the most pressing questions in this field.

What does it mean to die?

The concept of death is a complex one, and there are many different ways to approach it from a philosophical perspective. One question that arises is what it means to die. Is death simply the cessation of bodily functions, or is there something more to it than that? Many philosophers argue that death represents the end of consciousness and the self, which raises questions about the nature of the soul and the afterlife.

The morality of assisted suicide

Assisted suicide is a controversial topic, and it raises several ethical concerns. On the one hand, some argue that individuals have the right to end their own lives if they are suffering from a terminal illness or unbearable pain. On the other hand, others argue that assisting someone in taking their own life is morally wrong and violates the sanctity of life. We will explore these arguments and consider the ethical implications of assisted suicide.

The meaning of life in the face of death

The inevitability of death raises important questions about the meaning of life. If our time on earth is finite, what is the purpose of our existence? Is there a higher meaning to life, or is it simply a product of biological processes? Many philosophers have grappled with these questions, and we will explore some of the most influential theories in this field.

The role of death in shaping our lives

While death is often seen as a negative force, it can also have a positive impact on our lives. The knowledge that our time on earth is limited can motivate us to live life to the fullest and to prioritize the things that truly matter. We will explore the role of death in shaping our values, goals, and priorities, and consider how we can use this knowledge to live more fulfilling lives.

The ethics of mourning

The process of mourning is an important part of the human experience, and it raises several ethical questions. How should we respond to the death of others, and what is our ethical responsibility to those who are grieving? We will explore these questions and consider how we can support those who are mourning while also respecting their autonomy and individual experiences.

The ethics of immortality

The idea of immortality has long been a fascination for humanity, but it raises important ethical questions. If we were able to live forever, what would be the implications for our sense of self, our relationships with others, and our moral responsibilities? We will explore the ethical implications of immortality and consider how it might challenge our understanding of what it means to be human.

The ethics of death in different cultural contexts

Death is a universal human experience, but how it is understood and experienced varies across different cultures. We will explore how different cultures approach death, mourning, and the afterlife, and consider the ethical implications of these differences.

Death is a complex and multifaceted topic, and it raises important questions about the nature of life, morality, and human experience. By exploring the ethics of death from a philosophical perspective, we can gain a deeper understanding of these questions and how they shape our lives.

The Ripple Effect of Loss: How Death Impacts Relationships

Losing a loved one is one of the most challenging experiences one can go through in life. It is a universal experience that touches people of all ages, cultures, and backgrounds. The grief that follows the death of someone close can be overwhelming and can take a significant toll on an individual's mental and physical health. However, it is not only the individual who experiences the grief but also the people around them. In this article, we will discuss the ripple effect of loss and how death impacts relationships.

Understanding Grief and Loss

Grief is the natural response to loss, and it can manifest in many different ways. The process of grieving is unique to each individual and can be affected by many factors, such as culture, religion, and personal beliefs. Grief can be intense and can impact all areas of life, including relationships, work, and physical health.

The Impact of Loss on Relationships

Death can impact relationships in many ways, and the effects can be long-lasting. Below are some of how loss can affect relationships:

1. Changes in Roles and Responsibilities

When someone dies, the roles and responsibilities within a family or social circle can shift dramatically. For example, a spouse who has lost their partner may have to take on responsibilities they never had before, such as managing finances or taking care of children. This can be a difficult adjustment, and it can put a strain on the relationship.

2. Changes in Communication

Grief can make it challenging to communicate with others effectively. Some people may withdraw and isolate themselves, while others may become angry and lash out. It is essential to understand that everyone grieves differently, and there is no right or wrong way to do it. However, these changes in communication can impact relationships, and it may take time to adjust to new ways of interacting with others.

3. Changes in Emotional Connection

When someone dies, the emotional connection between individuals can change. For example, a parent who has lost a child may find it challenging to connect with other parents who still have their children. This can lead to feelings of isolation and disconnection, and it can strain relationships.

4. Changes in Social Support

Social support is critical when dealing with grief and loss. However, it is not uncommon for people to feel unsupported during this time. Friends and family may not know what to say or do, or they may simply be too overwhelmed with their grief to offer support. This lack of social support can impact relationships and make it challenging to cope with grief.

Coping with Loss and Its Impact on Relationships

Coping with grief and loss is a long and difficult process, but it is possible to find ways to manage the impact on relationships. Below are some strategies that can help:

1. Communication

Effective communication is essential when dealing with grief and loss. It is essential to talk about how you feel and what you need from others. This can help to reduce misunderstandings and make it easier to navigate changes in relationships.

2. Seek Support

It is important to seek support from friends, family, or a professional if you are struggling to cope with grief and loss. Having someone to talk to can help to alleviate feelings of isolation and provide a safe space to process emotions.

3. Self-Care

Self-care is critical when dealing with grief and loss. It is essential to take care of your physical and emotional well-being. This can include things like exercise, eating well, and engaging in activities that you enjoy.

4. Allow for Flexibility

It is essential to allow for flexibility in relationships when dealing with grief and loss. People may not be able to provide the same level of support they once did or may need more support than they did before. Being open to changes in roles and responsibilities can help to reduce strain on relationships.

5. Find Meaning

Finding meaning in the loss can be a powerful way to cope with grief and loss. This can involve creating a memorial, participating in a support group, or volunteering for a cause that is meaningful to you.

The impact of loss is not limited to the individual who experiences it but extends to those around them as well. Relationships can be greatly impacted by the death of a loved one, and it is important to be aware of the changes that may occur. Coping with loss and its impact on relationships involves effective communication, seeking support, self-care, flexibility, and finding meaning.

What Lies Beyond Reflections on the Mystery of Death

Death is an inevitable part of life, and yet it remains one of the greatest mysteries that we face as humans. What happens when we die? Is there an afterlife? These are questions that have puzzled us for centuries, and they continue to do so today. In this article, we will explore the various perspectives on death and what lies beyond.

Understanding Death

Before we can delve into what lies beyond, we must first understand what death is. Death is defined as the permanent cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. This can occur as a result of illness, injury, or simply old age. Death is a natural process that occurs to all living things, but it is also a process that is often accompanied by fear and uncertainty.

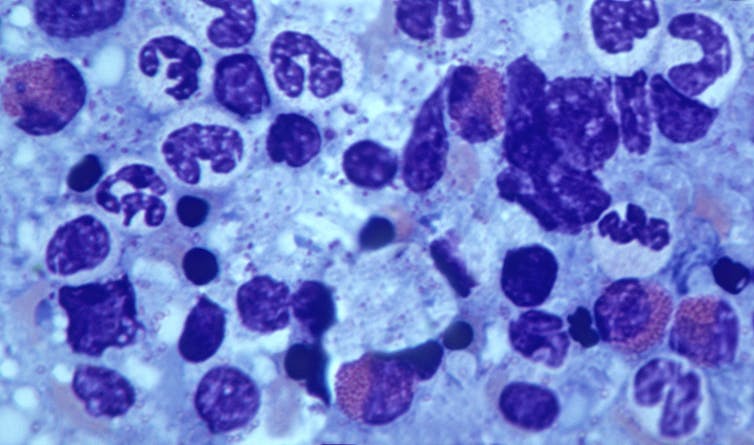

The Physical Process of Death

When a person dies, their body undergoes several physical changes. The heart stops beating, and the body begins to cool and stiffen. This is known as rigor mortis, and it typically sets in within 2-6 hours after death. The body also begins to break down, and this can lead to a release of gases that cause bloating and discoloration.

The Psychological Experience of Death

In addition to the physical changes that occur during and after death, there is also a psychological experience that accompanies it. Many people report feeling a sense of detachment from their physical body, as well as a sense of peace and calm. Others report seeing bright lights or visions of loved ones who have already passed on.

Perspectives on What Lies Beyond

There are many different perspectives on what lies beyond death. Some people believe in an afterlife, while others believe in reincarnation or simply that death is the end of consciousness. Let's explore some of these perspectives in more detail.

One of the most common beliefs about what lies beyond death is the idea of an afterlife. This can take many forms, depending on one's religious or spiritual beliefs. For example, many Christians believe in heaven and hell, where people go after they die depending on their actions during life. Muslims believe in paradise and hellfire, while Hindus believe in reincarnation.

Reincarnation

Reincarnation is the belief that after we die, our consciousness is reborn into a new body. This can be based on karma, meaning that the quality of one's past actions will determine the quality of their next life. Some people believe that we can choose the circumstances of our next life based on our desires and attachments in this life.

End of Consciousness

The idea that death is simply the end of consciousness is a common belief among atheists and materialists. This view holds that the brain is responsible for creating consciousness, and when the brain dies, consciousness ceases to exist. While this view may be comforting to some, others find it unsettling.

Death is a complex and mysterious phenomenon that continues to fascinate us. While we may never fully understand what lies beyond death, it's important to remember that everyone has their own beliefs and perspectives on the matter. Whether you believe in an afterlife, reincarnation, or simply the end of consciousness, it's important to find ways to cope with the loss of a loved one and to find peace with your mortality.

Final Words

In conclusion, these powerful essays on death offer inspiring perspectives and deep insights into the human experience of coping with mortality, grief, and loss. From personal accounts to philosophical reflections, these essays provide a diverse range of perspectives that encourage readers to contemplate their mortality and the meaning of life.

By reading and reflecting on these essays, readers can gain a better understanding of how death shapes our lives and relationships, and how we can learn to accept and cope with this inevitable part of the human experience.

If you're looking for a tool to help you write articles, essays, product descriptions, and more, Jenni.ai could be just what you need. With its AI-powered features, Jenni can help you write faster and more efficiently, saving you time and effort. Whether you're a student writing an essay or a professional writer crafting a blog post, Jenni's autocomplete feature, customized styles, and in-text citations can help you produce high-quality content in no time. Don't miss out on the opportunity to supercharge your next research paper or writing project – sign up for Jenni.ai today and start writing with confidence!

Start Writing With Jenni Today

Sign up for a free Jenni AI account today. Unlock your research potential and experience the difference for yourself. Your journey to academic excellence starts here.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Eat this. Take that. Get skinny. Trust us.

High doses of Adderall may increase psychosis risk

Breakthrough technique may help speed understanding, treatment of MD, ALS

Illustration by Tang Yau Hoong

How death shapes life

As global COVID toll hits 5 million, Harvard philosopher ponders the intimate, universal experience of knowing the end will come but not knowing when

Colleen Walsh

Harvard Staff Writer

Does the understanding that our final breath could come tomorrow affect the way we choose to live? And how do we make sense of a life cut short by a random accident, or a collective existence in which the loss of 5 million lives to a pandemic often seems eclipsed by other headlines? For answers, the Gazette turned to Susanna Siegel, Harvard’s Edgar Pierce Professor of Philosophy. Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Susanna Siegel

GAZETTE: How do we get through the day with death all around us?

SIEGEL: This question arises because we can be made to feel uneasy, distracted, or derailed by death in any form: mass death, or the prospect of our own; deaths of people unknown to us that we only hear or read about; or deaths of people who tear the fabric of our lives when they go. Both in politics and in everyday life, one of the worst things we could do is get used to death, treat it as unremarkable or as anything other than a loss. This fact has profound consequences for every facet of life: politics and governance, interpersonal relationships, and all forms of human consciousness.

When things go well, death stays in the background, and from there, covertly, it shapes our awareness of everything else. Even when we get through the day with ease, the prospect of death is still in some way all around us.

GAZETTE: Can philosophy help illuminate how death impacts consciousness?

SIEGEL: The philosophers Soren Kierkegaard and Martin Heidegger each discuss death, in their own ways, as a horizon that implicitly shapes our consciousness. It’s what gives future times the pressure they exert on us. A horizon is the kind of thing that is normally in the background — something that limits, partly defines, and sets the stage for what you focus on. These two philosophers help us see the ways that death occupies the background of consciousness — and that the background is where it belongs.

“Both in politics and in everyday life, one of the worst things we could do is get used to death, treat it as unremarkable or as anything other than a loss,” says Susanna Siegel, Harvard’s Edgar Pierce Professor of Philosophy.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

These philosophical insights are vivid in Rainer Marie Rilke’s short and stunning poem “Der Tod” (“Death”). As Burton Pike translates it from German, the poem begins: “There stands death, a bluish concoction/in a cup without a saucer.” This opening gets me every time. Death is standing. It’s standing in the way liquid stands still in a container. Sometimes cooking instructions tell you to boil a mixture and then let it stand, while you complete another part of the recipe. That’s the way death is in the poem: standing, waiting for you to get farther along with whatever you are doing. It will be there while you’re working, it will be there when you’re done, and in some way, it is a background part of those other tasks.

A few lines later, it’s suggested in the poem that someone long ago, “at a distant breakfast,” saw a dusty, cracked cup — that cup with the bluish concoction standing in it — and this person read the word “hope” written in faded letters on the side of mug. Hope is a future-directed feeling, and in the poem, the word is written on a surface that contains death underneath. As it stands, death shapes the horizon of life.

GAZETTE: What are the ethical consequences of these philosophical views?

SIEGEL: We’re familiar with the ways that making the prospect of death salient can unnerve, paralyze, or derail a person. An extreme example is shown by people with Cotard syndrome , who report feeling that they have already died. It is considered a “monothematic” delusion, because this odd reaction is circumscribed by the sufferers’ other beliefs. They freely acknowledge how strange it is to be both dead and yet still there to report on it. They are typically deeply depressed, burdened with a feeling that all possibilities of action have simply been shut down, closed off, made unavailable. Robbed of a feeling of futurity, seemingly without affordances for action, it feels natural to people in this state to describe it as the state of being already dead.

Cotard syndrome is an extreme case that illustrates how bringing death into the foreground of consciousness can feel utterly disempowering. This observation has political consequences, which are evident in a culture that treats any kind of lethal violence as something we have to expect and plan for. A glaring example would be gun violence, with its lockdown drills for children, its steady stream of the same types of events, over and over — as if these deaths could only be met with a shrug and a sigh, because they are simply part of the cost of other people exercising their freedom.

It isn’t just depressing to bring death into the foreground of consciousness by creating an atmosphere of violence — it’s also dangerous. Any political arrangement that lets masses of people die thematizes death, by making lethal violence perceptible, frequent, salient, talked-about, and tolerated. Raising death to salience in this way can create and then leverage feelings of existential precarity, which in turn emotionally equip people on a mass, nationwide scale to tolerate violence as a tool to gain political power. It’s now a regular occurrence to ram into protestors with vehicles, intimidate voters and poll workers, and prepare to attack government buildings and the people inside. This atmosphere disparages life, and then promises violence as defense against such cheapening, and a means of control.

GAZETTE: When we read about an accidental death in the newspaper, it can be truly unnerving, even though the victim is a stranger. And we’ve been hearing about a steady stream of deaths from COVID-19 for almost two years, to the point where the death count is just part of the daily news. Why is the process of thinking about these losses important?

SIEGEL: It might not seem directly related to politics, but when you react to a life cut short by thinking, “If this terrible thing could happen to them, then it could happen to me,” that reaction is a basic form of civic regard. It’s fragile, and highly sensitive to how deaths are reported and rendered in public. The passing moment of concern may seem insignificant, but it gets supplanted by something much worse when deaths are rendered in ways likely to prompt such questions as “What did they do to get in trouble?” or such suspicions as “They probably had it coming,” or such callous resignations as “They were going to die anyway.” We have seen some of those reactions during the pandemic. They are refusals to recognize the terribleness of death.

Deaths can seem even more haunting when they’re not recognized as a real loss, which is why it’s so important how deaths are depicted by governments and in mass communication. The genre of the obituary is there to present deaths as a loss to the public. The movement for Black lives brought into focus for everyone what many people knew and felt all along, which was that when deaths are not rendered as losses to the public, then they are depicted in a way that erodes civic regard.

When anyone dies from COVID, our political representatives should acknowledge it in a way that does justice to the gravity of that death. Recognizing COVID deaths as a public emergency belongs to the kind of governance that aims to keep the blue concoction where it belongs.

Share this article

You might like.

Popularity of newest diet drugs fuel ‘dumpster fire’ of risky knock-offs, questionable supplements, food products, experts warn

Among those who take prescription amphetamines, 81% of cases of psychosis or mania could have been eliminated if they were not on the high dose, findings suggest

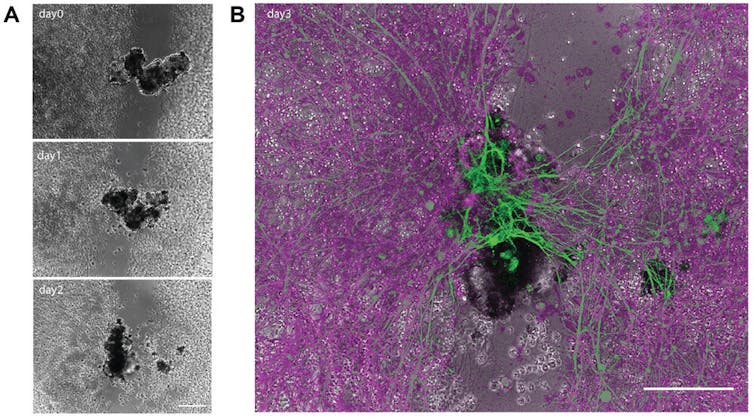

3D organoid system can generate millions of adult skeletal-muscle stem cells

Harvard releases race data for Class of 2028

Cohort is first to be impacted by Supreme Court’s admissions ruling

Parkinson’s may take a ‘gut-first’ path

Damage to upper GI lining linked to future risk of Parkinson’s disease, says new study

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Definition of Death

The philosophical investigation of human death has focused on two overarching questions: (1) What is human death? and (2) How can we determine that it has occurred? The first question is ontological or conceptual. An answer to this question will consist of a definition (or conceptualization ). Examples include death as the irreversible cessation of organismic functioning and human death as the irreversible loss of personhood . The second question is epistemological. A complete answer to this question will furnish both a general standard (or criterion ) for determining that death has occurred and specific clinical tests to show whether the standard has been met in a given case. Examples of standards for human death are the traditional cardiopulmonary standard and the whole-brain standard . Insofar as clinical tests are primarily a medical concern, the present entry will address them only in passing.

The philosophical issues concerning the correct definition and standard for human death are closely connected to other questions. How does the death of human beings relate to the death of other living things? Is human death simply an instance of organismic death, ultimately a matter of biology? If not, on what basis should it be defined? Whatever the answers to these questions, does death or at least human death have an essence—either de re or de dicto —entailing necessary and jointly sufficient conditions? Or do the varieties of death reveal only “family resemblance” relations? Are life and death exhaustive categories of those things that are ever animated, or do some individuals fall into an ontological neutral zone between life and death? Finally, how do our deaths relate, conceptually, to our essence and identity as human persons?

For the most part, such questions did not clamor for public attention until well into the twentieth century. (For historical background, see Pernick 1999 and Capron 1999, 120–124.) Sufficient destruction of the brain, including the brainstem, ensured respiratory failure leading quickly to terminal cardiac arrest. Conversely, prolonged cardiopulmonary failure inevitably led to total, irreversible loss of brain function. With the invention of mechanical respirators in the 1950s, however, it became possible for a previously lethal extent of brain damage to coexist with continued cardiopulmonary functioning, sustaining the functioning of other organs. Was such a patient alive or dead? The widespread dissemination in the 1960s of such technologies as mechanical respirators and defibrillators to restore cardiac function highlighted the possibility of separating cardiopulmonary and neurological functioning. Quite rapidly the questions of what constituted human death and how we could determine its occurrence had emerged as issues both philosophically rich and urgent.

Various practical concerns provided further impetus for addressing these issues. (Reflecting these concerns is a landmark 1968 report published by a Harvard Medical School committee led by physician Henry Beecher (Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School 1968).) Soaring medical expenditures provoked concerns about prolonged, possibly futile treatment of patients who presented some but not all of the traditionally recognized indicators of death. Certainly, it would be permissible to discontinue life-supports if these patients were dead. Concurrent interest in the evolving techniques of organ transplantation motivated physicians not to delay unnecessarily in determining that a patient had died. Removing vital organs as quickly as possible would improve the prospect of saving lives. But removing vital organs of living patients would cause their deaths, violating both laws against homicide and the widely accepted moral principle prohibiting the intentional killing of innocent human beings (see the entry on doing vs. allowing harm ). To be sure, there were—as there are now—individuals who held that procuring organs from, thereby killing, irreversibly unconscious patients who had consented to donate is a legitimate exception to this moral principle (see the entry on voluntary euthanasia ), but this judgment strikes many as a radical departure from common morality. In any event, in view of concerns about the possibility of killing in the course of organ procurement, physicians wanted clear legal guidance for determining when someone had died.

The remainder of this entry takes a dialectical form, focusing primarily on ideas and arguments rather than on history and individuals. It begins with an approach that nearly achieved consensus status after these issues came under the spotlight in the twentieth century: the whole-brain approach . (Most of what are here referred to as “approaches” include a standard and a corresponding definition of death; a few offer more radical suggestions for how to understand human death.) The discussion proceeds, in turn, to the higher-brain approach , to an updated cardiopulmonary approach , and to several more radical approaches. The discussion of each approach examines its chief assertions, its answers to questions identified above, leading arguments in its favor, and its chief difficulties. The entry as a whole is intended to identify the main philosophical issues connected with the definition and determination of human death, leading approaches that have been developed to address these issues, and principal strengths and difficulties of these visions viewed as competitors.

1. The Current Mainstream View: The Whole-Brain Approach

2.1 appeals to the essence of human persons, 2.2 appeals to personal identity, 2.3 the claim that the definition of death is a moral issue, 2.4 the appeal to prudential value.

- 3. A Proposed Return To Tradition: An Updated Cardiopulmonary Approach

4.1 Death as a Process, Not a Determinate Event

4.2 death as a cluster concept not amenable to classical definition, 4.3 death as separable from moral concerns, references cited, other important works, other internet resources, related entries.

According to the whole-brain standard, human death is the irreversible cessation of functioning of the entire brain, including the brainstem . This standard is generally associated with an organismic definition of death (as explained below). Unlike the older cardiopulmonary standard, the whole-brain standard assigns significance to the difference between assisted and unassisted respiration. A mechanical respirator can enable breathing, and thereby circulation, in a “brain-dead” patient—a patient whose entire brain is irreversibly nonfunctional. But such a patient necessarily lacks the capacity for unassisted respiration. On the old view, such a patient counted as alive so long as respiration of any sort (assisted or unassisted) occurred. But on the whole-brain account, such a patient is dead. The present approach also maintains that someone in a permanent (irreversible) vegetative state is alive because a functioning brainstem enables spontaneous respiration and circulation as well as certain primitive reflexes. [ 1 ]

Before turning to arguments for and against the whole-brain standard, it may be helpful to review some basic facts about the human brain, “whole-brain death” (total brain failure), and other states of permanent (irreversible) unconsciousness. (The most important terms for our purposes appear in italics.) We may think of the brain as comprising two major portions: (1) the “ higher brain ,” consisting of both the cerebrum , the primary vehicle of conscious awareness, and the cerebellum, which is involved in the coordination and control of voluntary muscle movements; and (2) the “ lower brain ” or brainstem . The brainstem includes the medulla , which controls spontaneous respiration, the reticular activating system , a sort of on/off switch that enables consciousness without affecting its contents (the latter job belonging to the cerebrum), as well as the midbrain and pons.

With these basic concepts in view, it may be easier to contrast various states of permanent unconsciousness. (For a helpful overview, see Cranford 1995.) “Whole-brain death” or total brain failure involves the destruction of the entire brain, both the higher brain and the brainstem. By contrast, in a permanent ( irreversible ) vegetative state (PVS), while the higher brain is extensively damaged, causing irretrievable loss of consciousness, the brainstem is largely intact. Thus, as noted earlier, a patient in a PVS is alive according to the whole-brain standard. Retaining brainstem functions, PVS patients exhibit some or all of the following: unassisted respiration and heartbeat; wake and sleep cycles (made possible by an intact reticular activating system, though destruction to the cerebrum precludes consciousness); pupillary reaction to light and eyes movements; and such reflexes as swallowing, gagging, and coughing. A rare form of unconsciousness that is distinct from PVS and tends to lead fairly quickly to death is permanent ( irreversible ) coma . This state, in which patients never appear to be awake, involves partial brainstem functioning. Permanently comatose patients, like PVS patients, can maintain breathing and heartbeat without mechanical assistance.

With this background, we turn to the advantages and disadvantages of the whole-brain approach. First, what considerations favor this approach over the traditional focus on cardiopulmonary function in determining death? The most prominent and arguably the most powerful case for the whole-brain standard appeals to two considerations: (1) the organismic definition of death and (2) an emphasis on the brain's role as the primary integrator of overall bodily functioning. (Some who regard a general definition of death as unnecessary have focused on consideration (2) in defending the whole-brain standard. Some others, as discussed later, have retained consideration (1) but dropped consideration (2).) An additional consideration that has been influential, yet is logically separable from the other two, is (3) the thesis that the whole-brain standard updates, without replacing, the traditional approach to defining death.

According to the organismic definition, death is the irreversible loss of functioning of the organism as a whole (Becker 1975; Bernat, Culver, and Gert 1981). Proponents of this approach emphasize that death is a biological occurrence common to all organisms. Although individual cells and organs live and die, organisms are the only entities that literally do so without being parts of larger biological systems. (Ideas, cultures, and machines live and die only figuratively; cells and tissues are literally alive but are parts of larger biological systems.) So an adequate definition of death must be adequate in the case of all organisms. What happens when a paramecium, clover, tree, mosquito, rabbit, or human dies? The organism stops functioning as an integrated unit and breaks down, turning what was once a dynamic object that took energy from the environment to maintain its own structure and functioning into an inert piece of matter subject to disintegration and decay. In the case of humans, no less than other organisms, death involves the collapse of integrated bodily functioning.

The whole-brain standard does not follow straightforwardly from the organismic conception of death. One might insist, after all, that a human organism's death occurs upon irreversible loss of cardiopulmonary function. Why think the brain so important? According to the mainstream whole-brain approach, the human brain plays the crucial role of integrating major bodily functions so only the death of the entire brain is necessary and sufficient for a human being's death (Bernat, Culver, and Gert 1981). Although heartbeat and breathing normally indicate life, they do not constitute life. Life involves integrated functioning of the whole organism. Circulation and respiration are centrally important, but so are maintenance of body temperature, hormonal regulation, and various other functions—as well as, in humans and other higher animals, consciousness. The brain makes all of these vital functions possible. Their integration within the organism is due to a central integrator, the brain.

This leading case for the whole-brain standard, then, consists in an organismic conception of death coupled with a view of the brain as the chief integrator of interdependent bodily functions. Another consideration sometimes advanced in favor of the whole-brain standard positions it as a part of time-honored tradition rather than a departure from tradition. (The argument may be understood either as an appeal to the authority of tradition or as an appeal to the practicality of not departing radically from tradition.) The claim is that the traditional focus on cardiopulmonary function is part and parcel of the whole-brain approach, that the latter does not revise our understanding of death but merely updates it with a more comprehensive picture that highlights the brain's crucial role:

Three organs—the heart, lungs, and brain—assume special significance … because their interrelationship is close and the irreversible cessation of any one very quickly stops the other two and consequently halts the integrated functioning of the organism as a whole. Because they were easily measured, circulation and respiration were traditionally the basic “vital signs.” But [they] are simply used as signs—as one window for viewing a deeper and more complex reality: a triangle of interrelated systems with the brain at its apex. [T]he traditional means of diagnosing death actually detected an irreversible cessation of integrated functioning among the interdependent bodily systems. When artificial means of support mask this loss of integration as measured by the old methods, brain-oriented criteria and tests provide a new window on the same phenomena (President's Commission 1981, 33).

According to this view, when the entire brain is nonfunctional but cardiopulmonary function continues due to a respirator and perhaps other life-supports, the mechanical assistance presents a false appearance of life, concealing the absence of integrated functioning in the organism as a whole.

The whole-brain approach clearly enjoys advantages. First, whether or not the whole-brain standard really incorporates, rather than replacing, the traditional cardiopulmonary standard, the former is at least fairly continuous with traditional practices and understandings concerning human death. Indeed, current law in the American states incorporates both standards into disjunctive form, most states adopting the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) while others have embraced similar language (Bernat 2006, 40). The UDDA states that “… an individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem, is dead,” (President's Commission 1981, 119). Similar legal developments have occurred in Canada (Law Reform Commission of Canada 1981; Canadian Congress Committee on Brain Death 1988). The close pairing of the whole-brain and cardiopulmonary standards in the law suggests that the whole-brain standard does not depart radically from tradition.

The present approach offers other advantages as well. For one, the whole-brain standard is prima facie plausible as a specification of the organismic definition of death in the case of human beings. Moreover, acceptance of whole-brain criteria for death facilitates organ transplantation by permitting a declaration of death and retrieval of still-viable organs while respiration and circulation continue, with mechanical assistance, in a “brain-dead” body. Another practical advantage is permitting, without an advance directive or proxy consent, discontinuation of costly life-support measures on patients who have incurred total brain failure. While most proponents of the whole-brain approach insist that such practical advantages are merely fortunate consequences of the biological facts about death, one might regard these advantages as part of the justification for a standard whose defense requires more than appeals to biology (see subsection 4.2 below).

The advantages proffered by this approach contributed to its widespread social acceptance and legal adoption in the last few decades of the 20 th century. As mentioned, every American state has legally adopted the whole-brain standard alongside the cardiopulmonary standard as in the UDDA. It is worth noting, however, that a close cousin to the whole-brain standard, the brainstem standard , was adopted by the United Kingdom and various other nations. According to the brainstem standard—which has the practical advantage of requiring fewer clinical tests—human death occurs at the irreversible cessation of brainstem function. One might wonder whether a person's cerebrum could function—enabling consciousness—while this standard is met, but the answer is no. Since the brainstem includes the reticular activating system, the on/off switch that makes consciousness possible (without affecting its contents), brainstem death entails irreversible loss not only of unassisted respiration and circulation but also of the capacity for consciousness. Importantly, outside the English-speaking world, many or most nations, including virtually all developed countries, have legally adopted either whole-brain or brainstem criteria for the determination of death (Wijdicks 2002). Moreover, most of the public, to the extent that it is aware of the relevant laws, appears to accept such criteria for death (ibid). Opponents commonly fall within one of two main groups. One group consists of religious conservatives—and, recently, a growing number of secular academics—who favor the cardiopulmonary standard, according to which one can be brain-dead yet alive if (assisted) cardiopulmonary function persists. The other group consists of those liberal intellectuals who favor the higher-brain standard (to be discussed), which, notably, has not been adopted by any jurisdiction.

The widespread acceptance in the U.S. of the whole-brain standard and the broader international acceptance of some sort of “brain death” criteria—whether whole-brain or brainstem—are remarkable considering the subtlety of issues surrounding the definition and determination of death. Yet this near-consensus has been broader than it is deep. Increasingly, both in academic and clinical circles, doubts about “brain death” are being voiced. Following are several major challenges to the whole-brain standard—and, implicitly, to the brainstem standard. (Several additional challenges are implicit in arguments supporting the higher-brain approach.)

The first challenge is directed at proponents of the whole-brain approach who claim that its standard merely updates, without replacing, the traditional cardiopulmonary standard. A major contention that motivates this thesis is that irreversible cessation of brain function will quickly lead to irreversible loss of cardiopulmonary function (and vice versa). But extended maintenance on respirators of patients with total brain failure has removed this component of the case for the whole-brain standard (PCB 2008, 90). The remaining challenges to the whole-brain approach are not specifically directed to those who assert that its standard merely updates the traditional cardiopulmonary standard.

First, in the case of at least some members of our species, total brain failure is not necessary for death. After all, human embryos and early fetuses can die although, lacking brains, they cannot satisfy whole-brain criteria for death (Persson 2002, 22–23). An advocate could respond by introducing a modified definition: In the case of any human being in possession of a functioning brain , death is the irreversible cessation of functioning of the entire brain. While this may be practically useful in the world as we know it for the foreseeable future, this definition is not conceptually satisfactory if it is possible in principle for some human beings with brains (that is, who have functioning brains at any point in their existence) to die without destruction of their brains. The “in principle” is important here, for this is not possible in our world currently. But suppose we develop the ability to transplant brains. (The thought-experiment that follows appears in McMahan 2002, 429.) Recall that the whole-brain standard is generally thought to receive support from an organismic definition of death. But such a conception of human death, one could argue, only makes sense on the assumption that we are essentially human organisms (see discussion of the essence of human persons in section 2.1)—as some proponents explicitly acknowledge (see, e.g., Olson 1997). According to the present critique, the brain is merely a part of the organism. Suppose the brain were removed from one of us, and kept intact and functioning, perhaps by being transplanted into another, de-brained body. Bereft of mechanical assistance, the body from which the brain was removed would surely die. But this body was the living organism, one of us. So, although the original brain continues to function, the human being, one of us, would have died. Total brain failure, then, is not strictly necessary for human death. A possible rebuttal to this challenge from one who accepts that we are essentially organisms is to argue that the existence of a functioning brain is sufficient for the continued existence of the organism (van Inwagen 1990, 173–174, 180–181). If so, then in the imagined scenario the original human being would survive the brain transplant in a new body. Thus, the rebuttal concludes, it is false that a human being could die although her brain continued to live.

Perhaps more threatening to the whole-brain approach is the growing empirical evidence that total brain failure is not sufficient for human death —assuming the latter is construed, as whole-brain advocates generally construe it, as the breakdown of integrated organismic functioning mediated by the brain. Many of our integrative functions, according to the challenge, are not mediated by the brain and can therefore persist in individuals who meet whole-brain criteria for death by standard clinical tests. Such somatically integrating functions include homeostasis, assimilation of nutrients, detoxification and recycling of cellular wastes, elimination, wound healing, fighting of infections, and cardiovascular and hormonal stress responses to unanesthetized incisions (for organ procurement); in a few cases, brain-dead bodies have even gestated a fetus, matured sexually, or grown in size (Shewmon 2001; Potts 2001). It has been argued that most brain functions commonly cited as integrative merely sustain an existing functional integration, suggesting that the brain is more an enhancer than an indispensable integrator of bodily functions (Shewmon 2001). Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that most patients diagnosed as brain dead continue to exhibit some brain functions including the regulated secretion of vasopressin, a hormone critical to maintaining a body's balance of salt and fluid (Halevy 2001). This hormonal regulation is a brain function that represents an integrated function of the organism as a whole (Miller and Truog 2010).

Another, related problem for the sufficiency of total brain failure for human death arises from reflection on locked-in syndrome . People with locked-in syndrome are conscious, and therefore alive, but completely paralyzed with the possible exception of their eyes. With intensive medical support they can live. The interesting fact for our purposes is that some patients with this syndrome exhibit no more somatic functioning integrated by the brain than some brain-dead individuals. Whatever integration of bodily functions remains is maintained by external supports and by bodily systems other than the brain, which merely preserves consciousness (Bartlett and Youngner 1988, 205–6). If total brain failure is supposed to be sufficient for death, and if this is true only because the former entails the loss of somatic functioning integrated by the brain, then the loss of those functions should also be sufficient for death. But these patients, who are clearly alive, show that this is not so. Either the whole-brain definition must be rejected or this particular reason for accepting the whole-brain approach must be rejected and some other good reason for accepting it found.

Recently, a new rationale—distinct from the one that understands human death in terms of loss of organismic functioning mediated by the brain—has been advanced in support of the whole-brain standard (PCB 2008, ch. 4). According to this rationale, a human being dies upon irreversibly losing the capacity to perform the fundamental work of an organism, a loss that occurs with total brain failure. The fundamental work of an organism is characterized as follows: (1) receptivity to stimuli from the surrounding environment; (2) the ability to act upon the world to obtain, selectively, what the organism needs; and (3) the basic felt need that drives the organism to act as it must to obtain what it needs and what its receptivity reveals to be available (ibid, 61). According to a sympathetic reading of the ambiguous discussion in which this analysis is advanced, any patient who meets even one of these criteria is alive and therefore not dead. A patient with total brain failure meets none of these criteria, even if a respirator permits the continuation of cardiopulmonary function. By contrast, PVS patients meet at least the second criterion through spontaneous respiration (a kind of acting upon the world to obtain what is needed: oxygen); and locked-in patients meet the first criterion if they can see or experience bodily sensation and certainly meet the third insofar as they are conscious. One difficulty with this “fundamental work” rationale for the whole-brain standard, a rationale that is intended to capture “what distinguishes every organism from non-living things” (ibid), is that some present-day robots, which are certainly not alive, seem to satisfy the first two criteria. If one insisted, contrary to the reading deemed sympathetic, that a being must satisfy all three criteria—as robots do not since they lack felt needs—in order to qualify as living, the same may be asserted not only of insentient animal life but also of presentient human fetuses and of unconscious human beings of any age. Another difficulty of the “fundamental work” rationale for the whole brain standard is that it was intended to replace the idea that integrated functional unity within an organism is what constitutes life—but the latter idea is extremely plausible and helps to explain what any “fundamental work” would be working toward (cf. Thomas 2012, 105). Whether any variation or modification of the present rationale for the whole-brain standard can survive critical scrutiny remains an open question.

Some traditional defenders of the cardiopulmonary approach believe that the insufficiency of whole-brain criteria for death is evident not only in exceptional cases, such as those described earlier, but in all cases in which patients with total brain failure exhibit respirator-assisted cardiopulmonary function. Anyone who is breathing and whose heart functions cannot be dead, they claim. The champion of whole-brain criteria may retort that such a body is not really breathing and circulating blood; the respirator is doing the work. The traditionalist, in response, will likely contend that what is important is not who or what is powering the breathing and heartbeat, just that they occur. Even complete dependence on external support for vital functions cannot entail that one is dead, the traditionalist will continue, as is evident in the fact that living fetuses are entirely dependent on their mothers' bodies; nor can complete dependence on mechanical support entail that one is dead, as is evident in the fact that many living people are utterly dependent on pacemakers.

A third major criticism of the whole-brain approach—at least in its legally authoritative formulation in the United States—concerns its conceptual and clinical adequacy. The whole-brain standard, taken at its word, requires for human death permanent cessation of all brain functions. Yet many patients who meet routine clinical tests for this standard continue to have minor brain functions such as electroencephalographic activity, isolated nests of living neurons, and hypothalamic functioning (see, e.g., Potts 2001, 482; Veatch 1993, 18; Nair-Collins and Miller forthcoming). Indeed, the latter, which controls neurohormonal regulation, is indisputably an integrating function of the brain (Brody 1999, 73). Now one could maintain the coherence of the whole-brain approach by insisting that the individuals in question are not really dead and that physicians ought to use more thorough clinical tests before declaring death (see, e.g., Capron 1999, 130–131). But whole-brain theorists tend to agree that these individuals are dead—that the residual functions are too trivial to count against a judgment of death (see, e.g., President's Commission 1981, 28–29; Bernat 1992, 25)—suggesting that the problem lies with the formulation of the whole-brain standard rather than with its spirit.

Within this spirit and in response to this challenge, a leading proponent of the whole-brain approach has revised both (1) the organismic definition of death to “the permanent cessation of the critical functions of the organism as a whole” and (2) the corresponding standard to permanent cessation of the critical functions of the whole brain (Bernat 1998, 17). The organism's critical functions may be identified by reference to its emergent functions—that is, properties of the whole organism that are not possessed by any of its component parts—as follows: “The irretrievable loss of the organism's emergent functions produces loss of the critical functioning of the organism as a whole and therefore is the death of the organism,” (Bernat 2006, 38). The emphasis on critical functions, of course, allows one to declare dead those patients with only trivial brain functions. According to this revised whole-brain approach, the critical functions of the organism are (1) the vital functions of spontaneous breathing and autonomic circulation control, (2) integrating functions that maintain the organism's homeostasis, and (3) consciousness. A human being dies upon losing all three. Whether this or some similar modification of the whole-brain approach adequately addresses the present challenge is a topic of ongoing debate (see, e.g., Brody 1999, Bernat 2006). What seems reasonably clear is that not all functions of the brain will count equally in any cogent defense of the whole-brain approach.

The judgment that some brain functions are trivial in this context invites a reconsideration of what is most significant about what the human brain does. According to an alternative approach, what is far and away most significant about human brain function is consciousness.

2. A Progressive Alternative: The Higher-Brain Approach

According to the higher-brain standard, human death is the irreversible cessation of the capacity for consciousness . “Consciousness” here is meant broadly, to include any subjective experience, so that both wakeful and dreaming states count as instances. Reference to the capacity for consciousness indicates that individuals who retain intact the neurological hardware needed for consciousness, including individuals in a dreamless sleep or reversible coma, are alive. One dies on this view upon entering a state in which the brain is incapable of returning to consciousness. This implies, somewhat radically, that a patient in a PVS or irreversible coma is dead despite continued brainstem function that permits spontaneous cardiopulmonary function. Although no jurisdiction has adopted the higher-brain standard, it enjoys the support of many scholars (see, e.g., Veatch 1975; Engelhardt 1975; Green and Wikler 1980; Gervais 1986; Bartlett and Youngner 1988; Puccetti 1988; Rich 1997; and Baker 2000). These scholars conceptualize, or define, human death in different ways—though in each case as the irreversible loss of some property for which the capacity for consciousness is necessary. This discussion will consider four leading argumentative strategies in support of the higher-brain approach.

One strategy for defending the higher-brain approach is to appeal to the essence of human persons on the understanding that this essence requires the capacity for consciousness (see, e.g., Bartlett and Youngner 1988; Veatch 1993; Engelhardt 1996, 248; Rich 1997; and Baker 2000, 5). “Essence” here is intended in a strict ontological sense: that property or set of properties of an individual the loss of which would necessarily terminate the individual's existence. From this perspective, we human persons—more precisely, we individuals who are at any time human persons—are essentially beings with the capacity for consciousness such that we cannot exist at any time without having this capacity at that time. We go out of existence, it is assumed, when we die, so death involves the loss of what is essential to our existence.

Unfortunately, the use of terminology in these arguments can be confusing because the same term may be used in different ways and terms are frequently used without precise definition. It is sometimes claimed, for example, that we are essentially persons . But what, exactly, is a person? Some authors (e.g., Engelhardt 1996, Baker 2000) use the term to refer to beings with relatively complex psychological capacities such as self-awareness over time, reason, and moral agency. Then the claim that we are essentially persons implies that we die upon losing such advanced capacities. But this means that at some point during the normal course of progressive dementia the demented individual dies—upon losing complex psychological capacities, however these are defined— despite the fact that a patient remains, clearly alive, with the capacity for (basic) consciousness . This view is extraordinarily radical and appears inconsistent with the higher-brain approach, which equates death with the irreversible loss of the capacity for (any) consciousness. A proponent of the view that we are essentially persons in the present sense, however, may hold that practical considerations—such as the impossibility of drawing a clear line between sentient persons and sentient nonpersons, and the potential for abuse of the elderly—recommend the capacity for consciousness as the only safe line to draw, thereby vindicating the higher-brain view (Engelhardt 1996, 250). Meanwhile, other proponents of the view that we are essentially persons (e.g., Bartlett and Youngner 1988) apparently hold that any member of our species who retains the capacity for consciousness qualifies as a person. This view, unlike the previous one, straightforwardly supports the higher-brain standard. Still other authors (e.g., Veatch 1993) hold that we are essentially human beings where this term refers not to all members of our species but just to those judged to be persons by the previous group of authors: members of our species who have the capacity for consciousness. And some authors who defend the higher-brain standard (e.g., McMahan 2002) assert that we are essentially minds or minded beings , which is to say beings with the capacity for consciousness. In each case, an appeal to our essence is advanced to support the higher-brain standard.

Taking this collection of arguments together, the reasoning might be reconstructed as follows:

- For humans, the irreversible loss of the capacity for consciousness entails (is sufficient for) the loss of what is essential to their existence;

- For humans, loss of what is essential to their existence is (is necessary and sufficient for) death;

- For humans, irreversible loss of the capacity for consciousness entails (is sufficient for) death.

We have noted that various commentators who advance this reasoning hold that we are essentially persons in a sense requiring complex psychological capacities. We have noted that this implies that for those of us who become progressively demented, we die—go out of existence—at some point during the gradual slide to permanent unconsciousness. Even if practical considerations recommend safely drawing a line at irreversible loss of the capacity of consciousness for policy purposes, the implication that, strictly speaking, we go out of existence during progressive dementia will strike many as incredible. At the other end of life there is another problematic implication. For if we are essentially persons (in this sense), then inasmuch as human newborns lack the capacities that constitute personhood, each of us came into existence after what is ordinarily described as his or her birth.

For those attracted to the general approach of understanding our essence in terms of psychological capacities, a promising alternative thesis is that we are essentially beings with the capacity for at least some form of consciousness who die upon irreversibly losing that very basic capacity. Stated more simply, we are essentially minded beings, or minds, and we die when we completely “lose our minds.” (Note that this thesis is consistent with the claim that we are also essentially embodied.)

What, then, about the human organism associated with one of us minded beings? Surely the fetus that gradually developed prior to the emergence of sentience or the capacity for consciousness—that is, prior to the emergence of a mind—was alive. On the other end of life, a patient in a PVS who is spontaneously breathing, circulating blood, and exhibiting a full range of brainstem reflexes appears to be alive. Consider also anencephalic infants, who are born without cerebral hemispheres and never have the capacity for consciousness: They, too, seem to be living organisms, their grim prognosis notwithstanding. In response to this challenge, a proponent of the higher-brain approach may either (1) assert that the presentient fetus, PVS patient, and anencephalic infant are not alive despite appearances (Puccetti 1988) or (2) allow that these organisms are alive but are not of the same fundamental kind as we are: minded beings (McMahan 2002, 423–6). Insofar as life is a biological concept, and the organisms in question satisfy commonly accepted criteria for life, option (1) seems at best hyperbolic. At best, the claim is really that these organisms, though alive, are not alive in any state that matters much, so we may count them as dead or nonliving for our purposes. This claim, in turn, may be understood as depending on option (2), on which we may focus. This option implies that for each of us minded beings, there is a second, closely associated being: a human organism. The prospects of the present strategy for defending the higher-brain approach turn significantly on its ability to make sense of this picture of two closely associated beings: (1) the organism, which comes into existence at conception or shortly thereafter (perhaps after twinning is no longer possible) and dies when organismic functioning radically breaks down, and (2) the minded being, who comes into existence when sentience emerges and might—in the event of PVS or irreversible coma—die before the organism does. (For doubts on this score, see DeGrazia 2005, ch. 2).

Appealing to the authority of biologists and common sense, some philosophers (e.g., Olson 1997) charge as indefensible the claim that we (who are now) human persons were never presentient fetuses. One might also find puzzling the thesis that there is one definition of death, appealing to the capacity for consciousness, for human beings or persons and another definition, appealing to organismic functioning, for nonhuman animals and the human organisms associated with persons. It is open to the higher-brain theorist, however, to allow that there are also two closely associated beings in the case of sentient nonhuman animals—the minded being and the organism—with the death of, say, Lassie (the minded dog) occurring at her irreversible loss of consciousness (McMahan 2002, ch. 1). But some will find unattractive the failure to furnish a single conception of death that applies to all living things. To be sure, not everyone finds these objections compelling.

One of the most significant challenges confronting the present approach is to characterize cogently the relationship between one of us and the associated human organism. The relationship is clearly not identity —that is, being one and the same thing—because the organism originates before the mind, might outlive the mind, and therefore has different persistence conditions. This strongly suggests, perhaps surprisingly, that we human persons are not animals. If you are not identical to the human organism associated with you, then since there is at most one animal sitting in your chair, you are not she and are therefore not an animal (Olson 1997). Yet many consider it part of educated common sense that we are animals.

Might you be part of the organism associated with you—namely, the brain (more precisely, the portions of the brain associated with consciousness) (McMahan 2002, ch. 1)? But the brain seems capable of surviving death, when you are supposed to go out of existence. Are you then a functioning brain, which goes out of existence at the irreversible loss of consciousness? But it seems odd to identify the functioning brain—as distinct from the brain—as you. How could you be some organ only when it functions? Presumably you are a substance (see the entry on substance ), a bearer of properties, not a substance only when it has certain properties . One might reply that the functioning brain is itself a substance, a substance distinct from the brain, but that, too, strains credibility. Might you instead be not the brain, but the mind understood as the conscious properties of the brain? That would imply that you are a set of properties, rather than a substance, which is no less counterintuitive. Note that the charge of incredibility is not directed at the assertion that the mind is the functioning brain, or is a set of brain properties, and not a distinct substance—a thesis in good standing in the philosophy of mind (see the entries on identity theory of mind and functionalism ). The charge of incredibility is directed at the assertion that you are a set of properties and not a substance. [ 2 ]

Another possibility regarding the person/organism relationship is that the human organism constitutes the person it eventually comes to support (Baker 2000). One might even claim the legitimacy of saying—employing an “is” of constitution—that we are animals (or organisms), just as we can say that a statue constituted by a hunk of bronze, shaped in a particular way, is a hunk of bronze (ibid). Challenges to this reasoning includes doubts that we may legitimately speak of an “is” of constitution; if not, then the constitution view implies that we are not animals after all. Another challenge, which applies equally to the view that we minds are parts of organisms, concerns the counting of conscious beings. On either the constitution view or the part-whole view, you are essentially a being with the capacity for consciousness. Closely associated with you—without being (identical to) you, due to different persistence conditions—is a particular animal. But that animal, having a functioning brain, would also seem to be a conscious being. Either of these views, then, apparently suggests that for each of us there are two conscious beings, seemingly one too many. Despite such difficulties as these, the thesis that we are essentially minded beings remains a significant basis for the higher-brain approach to human death.