| | | | | |  Parts of SpeechWhat are the parts of speech, a formal definition. Table of Contents The Part of Speech Is Determined by the Word's FunctionAre there 8 or 9 parts of speech, the nine parts of speech, (1) adjective, (3) conjunction, (4) determiner, (5) interjection, (7) preposition, (8) pronoun, why the parts of speech are important, video lesson.  - You need to dig a well . (noun)

- You look well . (adjective)

- You dance well . (adverb)

- Well , I agree. (interjection)

- My eyes will well up. (verb)

- red, happy, enormous

- Ask the boy in the red jumper.

- I live in a happy place.

- I caught a fish this morning! I mean an enormous one.

- happily, loosely, often

- They skipped happily to the counter.

- Tie the knot loosely so they can escape.

- I often walk to work.

- It is an intriguingly magic setting.

- He plays the piano extremely well.

- and, or, but

- it is a large and important city.

- Shall we run to the hills or hide in the bushes?

- I know you are lying, but I cannot prove it.

- my, those, two, many

- My dog is fine with those cats.

- There are two dogs but many cats.

- ouch, oops, eek

- Ouch , that hurt.

- Oops , it's broken.

- Eek! A mouse just ran past my foot!

- leader, town, apple

- Take me to your leader .

- I will see you in town later.

- An apple fell on his head .

- in, near, on, with

- Sarah is hiding in the box.

- I live near the train station.

- Put your hands on your head.

- She yelled with enthusiasm.

- she, we, they, that

- Joanne is smart. She is also funny.

- Our team has studied the evidence. We know the truth.

- Jack and Jill went up the hill, but they never returned.

- That is clever!

- work, be, write, exist

- Tony works down the pit now. He was unemployed.

- I will write a song for you.

- I think aliens exist .

Are you a visual learner? Do you prefer video to text? Here is a list of all our grammar videos . Video for Each Part of Speech The Most Important Writing IssuesThe top issue related to adjectives. | Don't write... | Do write... |

|---|

| very happy boy | delighted boy | | very angry | livid | | extremely posh hotel | luxurious hotel | | really serious look | stern look | The Top Issue Related to Adverbs- Extremely annoyed, she stared menacingly at her rival.

- Infuriated, she glared at her rival.

The Top Issue Related to Conjunctions - Burger, Fries, and a shake

- Fish, chips and peas

The Top Issue Related to Determiners The Top Issue Related to InterjectionsThe top issue related to nouns, the top issue related to prepositions, the top issue related to pronouns, the top issue related to verbs. | Unnatural (Overusing Nouns) | Natural (Using a Verb) |

|---|

| They are in agreement that he was in violation of several regulations. | They agree he violated several regulations. | | She will be in attendance to present a demonstration of how the weather will have an effect on our process. | She will attend to demonstrate how the weather will affect our process. | - Crack the parts of speech to help with learning a foreign language or to take your writing to the next level.

This page was written by Craig Shrives . You might also like...Help us improve....  Was something wrong with this page?  Use #gm to find us quicker .  Create a QR code for this, or any, page.  mailing list  grammar forum teachers' zoneConfirmatory test. This test is printable and sendable  expand to full page  show as slides  download as .doc  print as handout  send as homework  display QR code The 9 Parts of Speech: Definitions and Examples- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

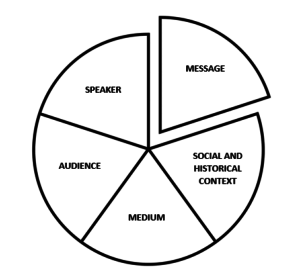

A part of speech is a term used in traditional grammar for one of the nine main categories into which words are classified according to their functions in sentences, such as nouns or verbs. Also known as word classes, these are the building blocks of grammar. Every sentence you write or speak in English includes words that fall into some of the nine parts of speech. These include nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections. (Some sources include only eight parts of speech and leave interjections in their own category.) Parts of Speech- Word types can be divided into nine parts of speech:

- prepositions

- conjunctions

- articles/determiners

- interjections

- Some words can be considered more than one part of speech, depending on context and usage.

- Interjections can form complete sentences on their own.

Learning the names of the parts of speech probably won't make you witty, healthy, wealthy, or wise. In fact, learning just the names of the parts of speech won't even make you a better writer. However, you will gain a basic understanding of sentence structure and the English language by familiarizing yourself with these labels. Open and Closed Word ClassesThe parts of speech are commonly divided into open classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) and closed classes (pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections). Open classes can be altered and added to as language develops, and closed classes are pretty much set in stone. For example, new nouns are created every day, but conjunctions never change. In contemporary linguistics , parts of speech are generally referred to as word classes or syntactic categories. The main difference is that word classes are classified according to more strict linguistic criteria. Within word classes, there is the lexical, or open class, and the function, or closed class. The 9 Parts of SpeechRead about each part of speech below, and practice identifying each. Nouns are a person, place, thing, or idea. They can take on a myriad of roles in a sentence, from the subject of it all to the object of an action. They are capitalized when they're the official name of something or someone, and they're called proper nouns in these cases. Examples: pirate, Caribbean, ship, freedom, Captain Jack Sparrow. Pronouns stand in for nouns in a sentence . They are more generic versions of nouns that refer only to people. Examples: I, you, he, she, it, ours, them, who, which, anybody, ourselves. Verbs are action words that tell what happens in a sentence. They can also show a sentence subject's state of being ( is , was ). Verbs change form based on tense (present, past) and count distinction (singular or plural). Examples: sing, dance, believes, seemed, finish, eat, drink, be, became. Adjectives describe nouns and pronouns. They specify which one, how much, what kind, and more. Adjectives allow readers and listeners to use their senses to imagine something more clearly. Examples: hot, lazy, funny, unique, bright, beautiful, poor, smooth. Adverbs describe verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs. They specify when, where, how, and why something happened and to what extent or how often. Many adjectives can be turned into adjectives by adding the suffix - ly . Examples: softly, quickly, lazily, often, only, hopefully, sometimes. PrepositionPrepositions show spatial, temporal, and role relations between a noun or pronoun and the other words in a sentence. They come at the start of a prepositional phrase , which contains a preposition and its object. Examples: up, over, against, by, for, into, close to, out of, apart from. ConjunctionConjunctions join words, phrases, and clauses in a sentence. There are coordinating, subordinating, and correlative conjunctions. Examples: and, but, or, so, yet. Articles and DeterminersArticles and determiners function like adjectives by modifying nouns, but they are different than adjectives in that they are necessary for a sentence to have proper syntax. Articles and determiners specify and identify nouns, and there are indefinite and definite articles. Examples of articles: a, an, the ; examples of determiners: these, that, those, enough, much, few, which, what. Some traditional grammars have treated articles as a distinct part of speech. Modern grammars, however, more often include articles in the category of determiners , which identify or quantify a noun. Even though they modify nouns like adjectives, articles are different in that they are essential to the proper syntax of a sentence, just as determiners are necessary to convey the meaning of a sentence, while adjectives are optional. InterjectionInterjections are expressions that can stand on their own or be contained within sentences. These words and phrases often carry strong emotions and convey reactions. Examples: ah, whoops, ouch, yabba dabba do! How to Determine the Part of SpeechOnly interjections ( Hooray! ) have a habit of standing alone; every other part of speech must be contained within a sentence and some are even required in sentences (nouns and verbs). Other parts of speech come in many varieties and may appear just about anywhere in a sentence. To know for sure what part of speech a word falls into, look not only at the word itself but also at its meaning, position, and use in a sentence. For example, in the first sentence below, work functions as a noun; in the second sentence, a verb; and in the third sentence, an adjective: - Bosco showed up for work two hours late.

- The noun work is the thing Bosco shows up for.

- He will have to work until midnight.

- The verb work is the action he must perform.

- His work permit expires next month.

- The attributive noun (or converted adjective) work modifies the noun permit .

Learning the names and uses of the basic parts of speech is just one way to understand how sentences are constructed. Dissecting Basic SentencesTo form a basic complete sentence, you only need two elements: a noun (or pronoun standing in for a noun) and a verb. The noun acts as a subject, and the verb, by telling what action the subject is taking, acts as the predicate. In the short sentence above, birds is the noun and fly is the verb. The sentence makes sense and gets the point across. You can have a sentence with just one word without breaking any sentence formation rules. The short sentence below is complete because it's a verb command with an understood "you" noun. Here, the pronoun, standing in for a noun, is implied and acts as the subject. The sentence is really saying, "(You) go!" Constructing More Complex SentencesUse more parts of speech to add additional information about what's happening in a sentence to make it more complex. Take the first sentence from above, for example, and incorporate more information about how and why birds fly. - Birds fly when migrating before winter.

Birds and fly remain the noun and the verb, but now there is more description. When is an adverb that modifies the verb fly. The word before is a little tricky because it can be either a conjunction, preposition, or adverb depending on the context. In this case, it's a preposition because it's followed by a noun. This preposition begins an adverbial phrase of time ( before winter ) that answers the question of when the birds migrate . Before is not a conjunction because it does not connect two clauses. - What Are Word Blends?

- Figure of Speech: Definition and Examples

- Definition and Examples of Adjectives

- Subjects, Verbs, and Objects

- What Is a Rhetorical Device? Definition, List, Examples

- What Is The Speech Act Theory: Definition and Examples

- A List of Exclamations and Interjections in English

- What Is Nonverbal Communication?

- Linguistic Variation

- Examples and Usage of Conjunctions in English Grammar

- Definition and Examples of Jargon

- Definition and Examples of Interjections in English

- Understanding the Types of Verbs in English Grammar

- Complementary vs. Complimentary: How to Choose the Right Word

- Basic Grammar: What Is a Diphthong?

- Subordinating Conjunctions

Have a language expert improve your writingRun a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free. - Knowledge Base

- Parts of speech

The 8 Parts of Speech | Chart, Definition & Examples A part of speech (also called a word class ) is a category that describes the role a word plays in a sentence. Understanding the different parts of speech can help you analyze how words function in a sentence and improve your writing. The parts of speech are classified differently in different grammars, but most traditional grammars list eight parts of speech in English: nouns , pronouns , verbs , adjectives , adverbs , prepositions , conjunctions , and interjections . Some modern grammars add others, such as determiners and articles . Many words can function as different parts of speech depending on how they are used. For example, “laugh” can be a noun (e.g., “I like your laugh”) or a verb (e.g., “don’t laugh”). Table of contents- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

Other parts of speechInteresting language articles, frequently asked questions. A noun is a word that refers to a person, concept, place, or thing. Nouns can act as the subject of a sentence (i.e., the person or thing performing the action) or as the object of a verb (i.e., the person or thing affected by the action). There are numerous types of nouns, including common nouns (used to refer to nonspecific people, concepts, places, or things), proper nouns (used to refer to specific people, concepts, places, or things), and collective nouns (used to refer to a group of people or things). Ella lives in France . Other types of nouns include countable and uncountable nouns , concrete nouns , abstract nouns , and gerunds . Check for common mistakesUse the best grammar checker available to check for common mistakes in your text. Fix mistakes for free A pronoun is a word used in place of a noun. Pronouns typically refer back to an antecedent (a previously mentioned noun) and must demonstrate correct pronoun-antecedent agreement . Like nouns, pronouns can refer to people, places, concepts, and things. There are numerous types of pronouns, including personal pronouns (used in place of the proper name of a person), demonstrative pronouns (used to refer to specific things and indicate their relative position), and interrogative pronouns (used to introduce questions about things, people, and ownership). That is a horrible painting! A verb is a word that describes an action (e.g., “jump”), occurrence (e.g., “become”), or state of being (e.g., “exist”). Verbs indicate what the subject of a sentence is doing. Every complete sentence must contain at least one verb. Verbs can change form depending on subject (e.g., first person singular), tense (e.g., simple past), mood (e.g., interrogative), and voice (e.g., passive voice ). Regular verbs are verbs whose simple past and past participle are formed by adding“-ed” to the end of the word (or “-d” if the word already ends in “e”). Irregular verbs are verbs whose simple past and past participles are formed in some other way. “I’ve already checked twice.” “I heard that you used to sing .” Other types of verbs include auxiliary verbs , linking verbs , modal verbs , and phrasal verbs . An adjective is a word that describes a noun or pronoun. Adjectives can be attributive , appearing before a noun (e.g., “a red hat”), or predicative , appearing after a noun with the use of a linking verb like “to be” (e.g., “the hat is red ”). Adjectives can also have a comparative function. Comparative adjectives compare two or more things. Superlative adjectives describe something as having the most or least of a specific characteristic. Other types of adjectives include coordinate adjectives , participial adjectives , and denominal adjectives . An adverb is a word that can modify a verb, adjective, adverb, or sentence. Adverbs are often formed by adding “-ly” to the end of an adjective (e.g., “slow” becomes “slowly”), although not all adverbs have this ending, and not all words with this ending are adverbs. There are numerous types of adverbs, including adverbs of manner (used to describe how something occurs), adverbs of degree (used to indicate extent or degree), and adverbs of place (used to describe the location of an action or event). Talia writes quite quickly. Other types of adverbs include adverbs of frequency , adverbs of purpose , focusing adverbs , and adverbial phrases . A preposition is a word (e.g., “at”) or phrase (e.g., “on top of”) used to show the relationship between the different parts of a sentence. Prepositions can be used to indicate aspects such as time , place , and direction . I left the cup on the kitchen counter. A conjunction is a word used to connect different parts of a sentence (e.g., words, phrases, or clauses). The main types of conjunctions are coordinating conjunctions (used to connect items that are grammatically equal), subordinating conjunctions (used to introduce a dependent clause), and correlative conjunctions (used in pairs to join grammatically equal parts of a sentence). You can choose what movie we watch because I chose the last time. An interjection is a word or phrase used to express a feeling, give a command, or greet someone. Interjections are a grammatically independent part of speech, so they can often be excluded from a sentence without affecting the meaning. Types of interjections include volitive interjections (used to make a demand or request), emotive interjections (used to express a feeling or reaction), cognitive interjections (used to indicate thoughts), and greetings and parting words (used at the beginning and end of a conversation). Ouch ! I hurt my arm. I’m, um , not sure. The traditional classification of English words into eight parts of speech is by no means the only one or the objective truth. Grammarians have often divided them into more or fewer classes. Other commonly mentioned parts of speech include determiners and articles. A determiner is a word that describes a noun by indicating quantity, possession, or relative position. Common types of determiners include demonstrative determiners (used to indicate the relative position of a noun), possessive determiners (used to describe ownership), and quantifiers (used to indicate the quantity of a noun). My brother is selling his old car. Other types of determiners include distributive determiners , determiners of difference , and numbers . An article is a word that modifies a noun by indicating whether it is specific or general. - The definite article the is used to refer to a specific version of a noun. The can be used with all countable and uncountable nouns (e.g., “the door,” “the energy,” “the mountains”).

- The indefinite articles a and an refer to general or unspecific nouns. The indefinite articles can only be used with singular countable nouns (e.g., “a poster,” “an engine”).

There’s a concert this weekend. If you want to know more about nouns , pronouns , verbs , and other parts of speech, make sure to check out some of our language articles with explanations and examples. Nouns & pronouns - Common nouns

- Proper nouns

- Collective nouns

- Personal pronouns

- Uncountable and countable nouns

- Verb tenses

- Phrasal verbs

- Types of verbs

- Active vs passive voice

- Subject-verb agreement

A is an indefinite article (along with an ). While articles can be classed as their own part of speech, they’re also considered a type of determiner . The indefinite articles are used to introduce nonspecific countable nouns (e.g., “a dog,” “an island”). In is primarily classed as a preposition, but it can be classed as various other parts of speech, depending on how it is used: - Preposition (e.g., “ in the field”)

- Noun (e.g., “I have an in with that company”)

- Adjective (e.g., “Tim is part of the in crowd”)

- Adverb (e.g., “Will you be in this evening?”)

As a part of speech, and is classed as a conjunction . Specifically, it’s a coordinating conjunction . And can be used to connect grammatically equal parts of a sentence, such as two nouns (e.g., “a cup and plate”), or two adjectives (e.g., “strong and smart”). And can also be used to connect phrases and clauses. Is this article helpful?Other students also liked, what is a collective noun | examples & definition. - What Is an Adjective? | Definition, Types & Examples

- Using Conjunctions | Definition, Rules & Examples

More interesting articles- Definite and Indefinite Articles | When to Use "The", "A" or "An"

- Ending a Sentence with a Preposition | Examples & Tips

- What Are Prepositions? | List, Examples & How to Use

- What Is a Determiner? | Definition, Types & Examples

- What Is an Adverb? Definition, Types & Examples

- What Is an Interjection? | Examples, Definition & Types

Get unlimited documents corrected✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts Instantly enhance your writing in real-time while you type. With LanguageTool Get started for free Understanding the Parts of Speech in EnglishYes, the parts of speech in English are extensive and complex. But we’ve made it easy for you to start learning them by gathering the most basic and essential information in this easy-to-follow and comprehensive guide.  Parts of Speech: Quick SummaryParts of speech assign words to different categories. There are eight different types in English. Keep in mind that a word can belong to more than one part of speech. Learn About:- Parts of Speech

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

Using the Parts of Speech Correctly In Your WritingKnowing the parts of speech is vital when learning a new language. When it comes to learning a new language, there are several components you should understand to truly get a grasp of the language and speak it fluently. It’s not enough to become an expert in just one area. For instance, you can learn and memorize all the intricate grammar rules, but if you don’t practice speaking or writing colloquially, you will find it challenging to use that language in real time. Conversely, if you don’t spend time trying to learn the rules and technicalities of a language, you’ll also find yourself struggling to use it correctly. Think of it this way: Language is a tasty, colorful, and nutritious salad. If you fill your bowl with nothing but lettuce, your fluency will be bland, boring, and tasteless. But if you spend time cultivating other ingredients for your salad—like style, word choice, and vocabulary— then it will become a wholesome meal you can share with others. In this blog post, we’re going to cover one of the many ingredients you’ll need to build a nourishing salad of the English language—the parts of speech. Let’s get choppin’!  What Are the Parts of Speech in English?The parts of speech refer to categories to which a word belongs. In English, there are eight of them : verbs , nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, and interjections. Many English words fall into more than one part of speech category. Take the word light as an example. It can function as a verb, noun, or adjective. Verb: Can you please light the candles? Noun: The room was filled with a dim, warm light . Adjective: She wore a light jacket in the cool weather. The parts of speech in English are extensive. There’s a lot to cover in each category—much more than we can in this blog post. The information below is simply a brief overview of the basics of the parts of speech. Nevertheless, the concise explanations and accompanying example sentences will help you gain an understanding of how to use them correctly.  What Are Verbs?Verbs are the most essential parts of speech because they move the meaning of sentences along. A verb can show actions of the body and mind ( jump and think ), occurrences ( happen or occur ), and states of being ( be and exist ). Put differently, verbs breathe life into sentences by describing actions or indicating existence. These parts of speech can also change form to express time , person , number , voice , and mood . There are several verb categories. A few of them are: - Regular and irregular verbs

- Transitive and intransitive verbs

- Auxiliary verbs

A few examples of verbs include sing (an irregular action verb), have (which can be a main verb or auxiliary verb), be , which is a state of being verb, and would (another auxiliary verb). My little sister loves to sing . I have a dog and her name is Sweet Pea. I will be there at 5 P.M. I would like to travel the world someday. Again, these are just the very basics of English verbs. There’s a lot more that you should learn to be well-versed in this part of speech, but the information above is a good place to start. What Are Nouns?Nouns refer to people ( John and child ), places ( store and Italy ), things ( firetruck and pen ), and ideas or concepts ( love and balance ). There are also many categories within nouns. For example, proper nouns name a specific person, place, thing, or idea. These types of nouns are always capitalized. Olivia is turning five in a few days. My dream is to visit Tokyo . The Supreme Court is the highest court in the United States. Some argue that Buddhism is a way of life, not a religion. On the other hand, common nouns are not specific to any particular entity and are used to refer to any member of a general category. My teacher is the smartest, most caring person I know! I love roaming around a city I’ve never been to before. This is my favorite book , which was recommended to me by my father. There’s nothing more important to me than love . Nouns can be either singular or plural. Singular nouns refer to a single entity, while plural nouns refer to multiple entities. Can you move that chair out of the way, please? (Singular) Can you move those chairs out of the way, please? (Plural) While many plural nouns are formed by adding an “–s” or “–es,” others have irregular plural forms, meaning they don’t follow the typical pattern. There was one woman waiting in line. There were several women waiting in line. Nouns can also be countable or uncountable . Those that are countable refer to nouns that can be counted as individual units. For example, there can be one book, two books, three books, or more. Uncountable nouns cannot be counted as individual units. Take the word water as an example. You could say I drank some water, but it would be incorrect to say I drank waters. Instead, you would say something like I drank several bottles of water. What Are Pronouns?A pronoun is a word that can take the place of other nouns or noun phrases. Pronouns serve the purpose of referring to nouns without having to repeat the word each time. A word (or group of words) that a pronoun refers to is called the antecedent . Jessica went to the store, and she bought some blueberries. In the sentence above, Jessica is the antecedent, and she is the referring pronoun. Here’s the same sentence without the proper use of a pronoun: Jessica went to the store, and Jessica bought some blueberries. Do you see how the use of a pronoun improves the sentence by avoiding repetitiveness? Like all the other parts of speech we have covered, pronouns also have various categories. Personal pronouns replace specific people or things: I, me, you, he, she, him, her, it, we, us, they, them. When I saw them at the airport, I waved my hands up in the air so they could see me . Possessive pronouns indicate ownership : mine, ours, yours, his, hers, theirs, whose. I think that phone is hers . Reflexive pronouns refer to the subject of a sentence or clause. They are used when the subject and the object of a sentence refer to the same person or thing: myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves. The iguanas sunned themselves on the roof of my car. Intensive pronouns have the same form as reflexive pronouns and are used to emphasize or intensify the subject of a sentence. I will take care of this situation myself . Indefinite pronouns do not refer to specific individuals or objects but rather to a general or unspecified person, thing, or group. Some examples include someone, everybody, anything, nobody, each, something, and all. Everybody enjoyed the party. Someone even said it was the best party they had ever attended. Demonstrative pronouns are used to identify or point to specific pronouns: this, that, these, those. Can you pick up those pens off the floor? Interrogative pronouns are used to ask questions and seek information: who, whom, whose, which, what. Who can help move these heavy boxes? Relative pronouns connect a clause or a phrase to a noun or pronoun: who, whom, whose, which, that, what, whoever, whichever, whatever. Christina, who is the hiring manager, is the person whom you should get in touch with. Reciprocal pronouns are used to refer to individual parts of a plural antecedent. They indicate a mutual or reciprocal relationship between two or more people or things: each other or one another. The cousins always giggle and share secrets with one another . What Are Adjectives?Adjectives modify nouns or pronouns, usually by describing, identifying, or quantifying them. They play a vital role in adding detail, precision, and imagery to English, allowing us to depict and differentiate the qualities of people, objects, places, and ideas. The blue house sticks out compared to the other neutral-colored ones. (Describes) That house is pretty, but I don’t like the color. (Identifies) There were several houses I liked, but the blue one was unique. (Quantifies) We should note that identifying or quantifying adjectives are also referred to as determiners. Additionally, articles ( a, an, the ) and numerals ( four or third ) are also used to quantify and identify adjectives. Descriptive adjectives have other forms (known as comparative and superlative adjectives ) that allow for comparisons. For example, the comparative of the word small is smaller, while the superlative is smallest. Proper adjectives (which are derived from proper nouns) describe specific nouns. They usually retain the same spelling or are slightly modified, but they’re always capitalized. For example, the proper noun France can be turned into the proper adjective French. What Are Adverbs?Adverbs are words that modify or describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, or entire clauses. Although many adverbs end in “–ly,” not all of them do. Also, some words that end in “–ly” are adjectives, not adverbs ( lovely ). She dances beautifully . In the sentence above, beautifully modifies the verb dances. We visited an extremely tall building. Here, the adverb extremely modifies the adjective tall. He had to run very quickly to not miss the train. The adverb very modifies the adverb quickly. Interestingly , the experiment yielded unexpected results that left us baffled. In this example, the word interestingly modifies the independent clause that comprises the rest of the sentence (which is why they’re called sentence adverbs ). Like adjectives, adverbs can also have other forms when making comparisons. For example: strongly, more strongly, most strongly, less strongly, least strongly What Are Prepositions?Prepositions provide context and establish relationships between nouns, pronouns, and other words in a sentence. They indicate time, location, direction, manner, and other vital information. Prepositions can fall into several subcategories. For instance, on can indicate physical location, but it can also be used to express time. Place the bouquet of roses on the table. We will meet on Monday. There are many prepositions. A few examples include: about, above, across, after, before, behind, beneath, beside, during, except, for, from, in, inside, into, like, near, of, off, onto, past, regarding, since, through, toward, under, until, with, without. Prepositions can contain more than one word, like according to and with regard to. What Are Conjunctions?Conjunctions are words that join words, phrases, or clauses together within a sentence and provide information about the relationship between those words. There are different types of conjunctions. Coordinating conjunctions connect words, phrases, or clauses of equal importance: and, but, for, not, or, so, yet. I like to sing, and she likes to dance. Correlative conjunctions come in pairs and join balanced elements of a sentence: both…and, just as…so, not only…but also, either…or, neither…nor, whether…or. You can either come with us and have fun, or stay at home and be bored. Subordinating conjunctions connect dependent clauses to independent clauses. A few examples include: after, although, even though, since, unless, until, when , and while. They had a great time on their stroll, even though it started raining and they got soaked. Conjunctive adverbs are adverbs that function as conjunctions, connecting independent clauses or sentences. Examples of conjunctive adverbs are also, anyway, besides, however, meanwhile, nevertheless, otherwise, similarly, and therefore . I really wanted to go to the party. However , I was feeling sick and decided to stay in. I really wanted to go to the party; however , I was feeling sick and decided to stay in. What Are Interjections?Interjections are words that express strong emotions, sudden reactions, or exclamations. This part of speech is usually a standalone word or phrase, but even when it is part of a sentence, it does not relate grammatically to the rest of . There are several interjections. Examples include: ahh, alas, bravo, eww, hello, please, thanks, and oops. Ahh ! I couldn’t believe what was happening. When it comes to improving your writing skills, understanding the parts of speech is as important as adding other ingredients besides lettuce to a salad. The information provided above is indeed extensive, but it’s critical to learn if you want to write effectively and confidently. LanguageTool—a multilingual writing assistant—makes comprehending the parts of speech easy by detecting errors as you write. Give it a try—it’s free!  Unleash the Professional Writer in You With LanguageToolGo well beyond grammar and spell checking. Impress with clear, precise, and stylistically flawless writing instead. Works on All Your Favorite Services- Thunderbird

- Google Docs

- Microsoft Word

- Open Office

- Libre Office

We Value Your FeedbackWe’ve made a mistake, forgotten about an important detail, or haven’t managed to get the point across? Let’s help each other to perfect our writing. - Words With Friends Cheat

- Word Finder

- Crossword Top Picks

- Anagram Solver

- Word Descrambler

- Word Unscrambler

- Scrabble Cheat

- Unscrambler

- Scrabble Word Finder

- Word Scramble

- Scrabble Go Word Finder

- Word Solver

- Jumble Solver

- Blossom Answer Finder

- Crossword Solver

- NYT Spelling Bee Answers

- Wordscapes Answers

- Word Cookies Answers

- Words Of Wonders

- 4 Pics 1 Word

- Word Generator

- Anagramme Expert

- Apalabrados Trucos

- Today's NYT Wordle Answer

- Today's NYT Connections Answers

- Today's Connections Hints

- Today's NYT Mini Crossword Answers

- Today's NYT Spelling Bee Answers

- Today's Contexto Answer

- Today's NYT Strands Answer

- Grammar Rules And Examples

- Misspellings

- Confusing Words

- Scrabble Dictionary

- Words With Friends Dictionary

- Words Ending In

- Words By Length

- Words With Letters

- Words Start With

- 5-letter Words With These Letters

- 5-letter Words Start With

- 5-letter Words Ending In

- All Consonant Words

- Vowel Words

- Words With Q Without U

- Username Generator

- Password Generator

- Random Word Generator

- Word Counter

Parts Of Speech: Breaking Them Down With ExamplesAuthor: sarah perowne, more content, why understanding parts of speech is important , the 8 parts of speech: definitions, examples, and rules, 2. pronouns, 3. adjectives, 6. prepositions, 7. conjunctions, 8. articles, takeaways - tips. Parts of speech are like Legos. Instead of being made into houses or spaceships, they’re the building blocks we use to form written and spoken language. Every word you speak or write is a part of speech. In the English language, there are 8 parts of speech: nouns , pronouns , adjectives , verbs , adverbs , prepositions , conjunctions , and articles (determiners). These parts of speech represent categories of words according to their grammatical function.  Having a basic understanding of the parts of speech in the English language gives you a specific terminology and classification system to talk about language. It can help you correctly punctuate a sentence, capitalize the right words, and even understand how to form a complete sentence to avoid grammatical errors. | Part Of Speech | Function | Example Vocabulary | Example Sentences |

|---|

| Part Of Speech Noun | Function is a person or thing. | Example Vocabulary Birthday, cake, Paris, flat | Example Sentences Today is my birthday. I like cake. I have a flat; It's in Paris. | | Part Of Speech Pronoun | Function is a noun substitute. | Example Vocabulary I, you, she, her, him, some, and them. | Example Sentences Susan is my neighbor; She is charming. | | Part Of Speech Adjective | Function describes the noun in a sentence. | Example Vocabulary Happy, small, cozy, hungry, and warm. | Example Sentences She lives in a small cottage. Her home is cozy and warm. | | Part Of Speech Verb | Function is an action word or state of being. | Example Vocabulary Run, jump, sleep, can, do, (to) be, or like | Example Sentences The teacher is happy; she likes her students. | | Part Of Speech Adverb | Function describes a verb, adverb, or adjective. | Example Vocabulary Merrily, slowly, softly, or quickly | Example Sentences The girl spoke softly. She walked away slowly. | | Part Of Speech Preposition | Function connects a noun or pronoun to another word. Shows the direction, location, or movement. | Example Vocabulary In, on, at, to, after. | Example Sentences We left by bus in the morning. Conjunction,"connects words, sentences, or clauses. | | Part Of Speech Article | Function shows whether a specific identity is known or unknown. | Example Vocabulary A, an, and the. | Example Sentences A man called today. The cat is on the table; get it off! |

Still with us? Now, we will break down each of these English grammar categories and give some examples. Nouns are words that name a person, place, thing, or idea. They can be further classified into different types of nouns . Proper Nouns Vs. Common NounsThere are some nouns we can count and others we cannot. Take a look at this table. | Type Of Noun | Definition | Examples |

|---|

| Type Of Noun Proper Nouns | Definition Name a specific person, place, or thing. Always start with a capital letter. | Examples Egypt, Paul, Eiffel Tower, Chicago | | Type Of Noun Common Nouns | Definition Don’t name a specific person, place, or thing. Don’t start with a capital letter unless they are placed at the beginning of a sentence. | Examples dog, houses, sleep, homes, cup |

Concrete Nouns Vs. Abstract Nouns| Type Of Noun | Definition | Examples |

|---|

| Type Of Noun Concrete Nouns | Definition Identify material things. | Examples apple, boy, clock, table, window | | Type Of Noun Abstract Nouns | Definition Express a characteristic or idea. | Examples happiness, tranquility, war, danger, friendship |

Singular Nouns Vs. Plural Nouns| Rule | Add | Singular Noun Examples | Plural Noun Examples |

|---|

| Rule For most common nouns… | Add -s | Singular Noun Examples Chair | Plural Noun Examples Chairs | | Rule For nouns that end in -ch, -s, -ch, or x… | Add -es | Singular Noun Examples Teach | Plural Noun Examples Teaches | | Rule For nouns ending with -y and a vowel… | Add -s | Singular Noun Examples Toy | Plural Noun Examples Toys | | Rule For nouns ending with -y and a consonant… | Add Remove -y and add -ies | Singular Noun Examples Lady | Plural Noun Examples Ladies | | Rule For nouns ending in -o and a vowel… | Add -es or -s | Singular Noun Examples Tomato | Plural Noun Examples Tomatoes | | Rule For nouns ending in -f or -fe… | Add Remove -fe or -f and add -v and -es | Singular Noun Examples Leaf | Plural Noun Examples Leaves | | Rule For nouns ending in o- and consonant… | Add -es | Singular Noun Examples Echo | Plural Noun Examples Echoes |

Exceptions To The Rule Some nouns are irregular, and it’s a case of learning their plural form as they don’t always follow specific rules. Here are some examples: | Singular Irregular Noun | Plural Form |

|---|

| Singular Irregular Noun Man | Plural Form Men | | Singular Irregular Noun Woman | Plural Form Women | | Singular Irregular Noun Tooth | Plural Form Teeth | | Singular Irregular Noun Child | Plural Form Children | | Singular Irregular Noun Person | Plural Form People | | Singular Irregular Noun Buffalo | Plural Form Buffalo |

Countable Vs. Uncountable Nouns| Countable Nouns | Uncountable of Mass Nouns | Countable and Uncountable Nouns |

|---|

| Countable Nouns Singular and Plural | Uncountable of Mass Nouns Cannot be pluralized | Countable and Uncountable Nouns Depends on the context of the sentence | | Countable Nouns Table / Tables | Uncountable of Mass Nouns Hair | Countable and Uncountable Nouns Chicken / A chicken | | Countable Nouns Chair / Chairs | Uncountable of Mass Nouns Air | Countable and Uncountable Nouns Coffee / Two coffees | | Countable Nouns Dog / Dogs | Uncountable of Mass Nouns Information | Countable and Uncountable Nouns Paper / Sheet of paper | | Countable Nouns Quantifiers: some, many, a few, a lot, numbers | Uncountable of Mass Nouns Quantifiers: some, any, a piece, a lot of, much, a little | Countable and Uncountable Nouns |

Other Types of NounsPossessive nouns. Possessive nouns possess something and usually have ‘s or simply ‘ at the end. When the noun is singular, we add an ‘s. When the noun is plural, we add an apostrophe. Here are examples of possessive nouns : - David’s sister has a dog.

- His sister’s dog is named Max.

Collective NounsCollective nouns refer to a group or collection of things, people, or animals. Such as, - Choir of singers

- Herd of sheep

Noun PhrasesA noun phrase is two or more words that function as a noun in a sentence. It also includes modifiers that can come before or after the noun. Here are examples of noun phrases: - The little brown dog is mine.

- The market down the street has the best prices.

If you want to know where to find nouns in a sentence, look for the subject or a direct object, and they will stand right out. For example: - Mary ate chocolate cake and ice cream .

(Mary = Subject) (Chocolate cake, and ice cream = direct objects) This is an easy way to identify nouns in a sentence. Pronouns are words used in the place of a noun or noun phrase. They can be further classified into different types of pronouns , such as personal, reflexive, and possessive. Personal Pronouns| Subject | Person Pronoun | Examples |

|---|

| Subject 1st Person Singular | Person Pronoun I | Examples I am walking. | | Subject 2nd Person Singular | Person Pronoun You | Examples You are walking. | | Subject 3rd Person Singular | Person Pronoun She, He, and It | Examples It is walking. | | Subject 1st Person Plural | Person Pronoun We | Examples We are walking. | | Subject 2nd Person Plural | Person Pronoun You (all) | Examples You are walking. | | Subject 3rd Person Plural | Person Pronoun They | Examples They are walking. |

Reflexive PronounsSome examples of reflexive pronouns are myself, yourself, herself, and itself. Here are examples of reflexive pronouns in sentences: - I helped myself to an extra serving of gravy.

- She didn’t do the cooking herself.

- The word itself is pretty easy to spell but hard to pronounce.

Reflexive pronouns can also be used for emphasis, as in this sentence: - Joe himself baked the cake.

Possessive PronounsSome examples of possessive pronouns are my, mine, your, yours, his, hers, its, ours, and theirs. We use these words when we want to express possession. Such as, - Is this your car?

- No, it’s his .

- It’s not mine .

Mine, yours, and his are examples of the independent form of possessive pronouns , and when showing possession, these pronouns never need an apostrophe. Adjectives are words that describe nouns or pronouns. They make the meaning more definite. When we want to talk about what kind of a house we have, we can use adjectives to describe it, such as big, red, or lovely. We can use adjectives to precede the word it modifies, like this; - She wore a beautiful , blue dress.

Or we can use adjectives following the word they modify, like this; - The athlete, tall and thin , was ready to win the race.

There are many types of adjectives, one being possessive . The seven possessive adjectives are my, your, his, her, its, our, and their. These words modify a noun or pronoun and show possession. Such as, - Their dog is brown.

- How old is your brother?

- That was my idea.

Verbs are words that express an action or a state of being. All verbs help to make a complete statement. Action verbs express a physical action, for example: Other verbs express a mental action, for example: These can also be called lexical verbs . Lexical Verbs and Auxiliary VerbsSometimes lexical verbs need the help of another type of verb . That’s where helping verbs , or auxiliary verbs , come into action; they help to make a statement or express action. Examples of auxiliary verbs are am, are, is, has, can, may, will be, and might have. When we use more than one verb when writing or speaking to express an action or state of being, it’s a verbal phrase consisting of the main verb, lexical verb, and one or more auxiliary verbs. Some examples of verbal phrases: - Should have done

- Must have been broken

- Will be following

Here are examples of verbal phrases used in a sentence. - You should have gone to the concert last night. It was amazing!

- I may go to the concert next time if I have the money for a ticket.

- I might have missed out this time, but I certainly won’t next time.

Adverbs are used to describe an adjective, verb, or even another adverb . They can express how something is done, as in splendidly or poorly . Here are some examples of adverbs in use: - She was running extremely fast during that race .

The adverb extremely modifies the adjective fast , expressing just how rapid the runner was. - I can hardly see it in the distance.

The adverb hardly modifies the verb see , expressing how much is visible, which in this case is not much at all. - It’s been surprisingly poorly cleaned.

The adverb surprisingly modifies the adverb poorly, expressing the surprise at how badly the car has been cleaned. They are used to show relationships between words, such as nouns or pronouns, with other words in the sentence. They can indicate spatial or time relationships. Some common prepositions are about, at, before, behind, but, in, off, on, to, and with. Here are some examples of common prepositions in sentences: - She sat behind me in class.

- Her mother was from Vietnam.

- The two of us worked together on the project.

Prepositions are followed by objects of prepositions, a noun, or a noun phrase that follows to give it meaning. - Julie goes to school with Mark . (With whom? Mark.)

Groups of words can also act as prepositions together, such as in spite of . - In spite of all the traffic, we arrived just on time.

Conjunctions link words or groups of words together. We often use them to create complex sentences. There are three types of conjunctions: coordinating conjunctions , correlative conjunctions , and subordinating conjunctions. Coordinating ConjunctionsExamples of coordinating conjunctions are and, but, or, nor, for, so, and yet. Such as: - He wanted apple pie and ice cream.

- She offered him fruit or cookies.

- He ate the fruit but still wanted apple pie.

Correlative ConjunctionsCorrelative conjunctions are used in pairs. Some examples are; Here is an example of the conjunctions above in use: - He wanted neither fruit nor cookies for dessert.

Subordinating ConjunctionsWe use subordinating conjunctions to begin subordinate clauses or sentences. Some examples of common subordinating conjunctions are after, before, then, when, provided, unless, so that, and while. Such as, - He left the house before it turned dark.

- He realized he had forgotten a gift when he arrived at the party.

- The party was better than he had imagined.

There are three articles in the English language: a, an, and the. Articles can indicate whether a specific identity is known or not. A and an are called indefinite articles and refer to a general group. Such as, - A woman is at the front door.

- She stood there for a minute.

- She had a book in her hand.

The is a definite article and refers to a specific thing or person. Such as, - The woman at the door is my friend Tracy.

- She’s returning the book she borrowed last week.

Getting these right to know if we’re talking about a specific item, person, or thing, in general, is important. How many parts of speech are there in the English language? Are there 8, 9, or 10?Many words can also be used as more than one part of speech.. Once you get the hang of it, identifying the various parts of speech in a sentence will be second nature, like riding a bike. And just think, it can help you craft stronger sentences! More Parts of Speech Topics:- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Popular Pages

- Top Searches

- External Resources

- Definitions

- WordFinderX

- Letter Solver

What part of speech is dangerous? The word dangerous is an adjective. The noun form is danger. Anonymous ∙ Add your answer: What part of speech is danger?Danger is a noun. Other words that come from danger are dangerous, which is an adjective, and dangerously, which is an adverb. What part of speech is hate?A noun, verb, or adjective:Hate is a dangerous vice. (noun, subject of the sentence)I hate him. (verb)He was arrested for his hate speech. (adjective, describes the noun 'speech') What part of speech is What part of speech is?What part of speech is camping. i want to know what part of speech is camping What part of speech is without?what part of speech is beneath  Top Categories  This tool allows you to find the grammatical word type of almost any word. - dangerous can be used as a adjective in the sense of "Full of danger."

Related SearchesWhat type of word is ~term~ . Unfortunately, with the current database that runs this site, I don't have data about which senses of ~term~ are used most commonly. I've got ideas about how to fix this but will need to find a source of "sense" frequencies. Hopefully there's enough info above to help you understand the part of speech of ~term~ , and guess at its most common usage. For those interested in a little info about this site: it's a side project that I developed while working on Describing Words and Related Words . Both of those projects are based around words, but have much grander goals. I had an idea for a website that simply explains the word types of the words that you search for - just like a dictionary, but focussed on the part of speech of the words. And since I already had a lot of the infrastructure in place from the other two sites, I figured it wouldn't be too much more work to get this up and running. The dictionary is based on the amazing Wiktionary project by wikimedia . I initially started with WordNet , but then realised that it was missing many types of words/lemma (determiners, pronouns, abbreviations, and many more). This caused me to investigate the 1913 edition of Websters Dictionary - which is now in the public domain. However, after a day's work wrangling it into a database I realised that there were far too many errors (especially with the part-of-speech tagging) for it to be viable for Word Type. Finally, I went back to Wiktionary - which I already knew about, but had been avoiding because it's not properly structured for parsing. That's when I stumbled across the UBY project - an amazing project which needs more recognition. The researchers have parsed the whole of Wiktionary and other sources, and compiled everything into a single unified resource. I simply extracted the Wiktionary entries and threw them into this interface! So it took a little more work than expected, but I'm happy I kept at it after the first couple of blunders. Special thanks to the contributors of the open-source code that was used in this project: the UBY project (mentioned above), @mongodb and express.js . Currently, this is based on a version of wiktionary which is a few years old. I plan to update it to a newer version soon and that update should bring in a bunch of new word senses for many words (or more accurately, lemma). Recent Queries  - Staff and Board

- Code of Conduct

- News Coverage

- Work With Us

- Publications

- What is Dangerous Speech?

- Dangerous Speech Examples

- What is Counterspeech?

Dangerous Speech: A Practical Guide- Dangerous Speech and the 2024 U.S. Election

- Global Research Initiative

- Third Party Resources

- South Sudan

- United States