Presentation Punishment and Removal Punishment

Examples include spanking, dirty looks, and being yelled at. An example of presentation punishment: Melissa throws a fit when she has to go to bed, and her mom spanks her in order to stop her from crying. The next time Melissa is sent to bed, she might not cry because she doesn’t want to get spanked.

Removal punishment is the removal of a previously existing stimulus in response to a behavior. Removal can mean the loss of privilege or freedom (grounding…).

For instance, Bob keeps making fun of his brother, so his mom takes away his nintendo. The next time Bob thinks he wants to make fun of his brother, he might decide not to in order to avoid the removal punishment.

Others are Reading

- Print Article

People Who Read This Also Read:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Prove You\'re Human * nine + 7 =

The use of unpleasant or displeasing stimuli to reduce the reoccurrence of a particular behavior by causing an individual to avoid the behavior in the future.

- Stumbleupon

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

You must be logged in to post a comment.

New membership are not allowed.

- Our Mission

- Section A: Philosophical Underpinnings

- Section B: Concepts and Principles

- Section C: Measurement, Data Display, and Interpretation

- Section D: Experimental Design

- Section E: Ethics

- Section F: Behavior Assessment

- Section G: Behavior Change Procedures

- Section H: Selecting and Implementing Interventions

- Section I: Personnel Supervision and Management

- Section A: Behaviorism and Philosophical Foundations

- Section E: Ethical and Professional Issues

- Section G: Behavior-Change Procedures

- Downloadable Products

- Grad School Review Study Course

- Continuing Education Courses

- Free Practitioner Resources

- Misc. Study Resources

- Section A (Philosophical Underpinnings) Quiz

- Section B (Concepts and Principles) Quiz

- Section C (Measurement, Data Display, and Interpretation) Quiz

- Section D (Experimental Design) Quiz

- Section F (Behavior Assessment) Quiz

- Section G (Behavior Change Procedures) Quiz

B-6: Define and provide examples of positive and negative punishment contingencies ©

Want this as a downloadable pdf click here.

Target Terms: Positive Punishment, Negative Punishment

Positive Punishment

Definition : The presentation of a stimulus (punishment) follows a response, which then results in a decrease in the future frequency of the behavior.

Example in an everyday context: Your cat jumps up onto the counter which they are not supposed to do. You spray your cat with water from a spray bottle and say, “No!” You never see your cat jump up onto the counter again. The introduction of the spray bottle and saying “no” immediately following the behavior of jumping up on the counter resulted in a decrease in that behavior.

Example in clinical context : During an art activity, a client becomes aggressive toward a staff member on the unit. The staff member physically restrains the client and takes them to the seclusion room. The presentation of the restraint and seclusion procedure decreased the future frequency of the client engaging in aggression during art time, which indicates that restraint/seclusion functioned as punishment.

Example in supervision context: A supervisor conducts an observation of a teacher in their classroom. The supervisor tells the teacher that their instructional methods were “horrible” and heavily criticized their performance. The teacher no longer uses those instructional methods. The presentation of the verbal reprimand decreased the future frequency of the teacher using those instructional methods.

Why it matters: Positive punishment should be used as a last resort (i.e., reinforcement-based interventions have been or are likely to be ineffective ) when designing intervention and treatment. It is extremely important to understand that punishment may yield to unwanted side effects, such as avoidance of the person delivering punishment, as well as emotional and aggressive responding beyond what was previously seen. It is also important to be thoroughly familiar with federal and state laws regarding the use of aversives, restraints, and seclusion procedures.

Negative Punishment

Definition : The removal of a stimulus (punishment) follows a response, which then results in a decrease in the future frequency of the behavior.

Example in everyday context: You are at a restaurant by yourself and eating at a table. You get up to use the restroom. While you are gone, your server removes your plate of food. You return from the restroom to find that your plate of food is gone. In the future, you will be less likely to leave your food before you are done.

Example in clinical context : A client really likes country music and is permitted to listen to it during leisure time. The client is working on keeping their hands in a respectful place (away from their crotch) when in common areas of the milieu. Staff members turn off the music (remove stimulus) when the client puts their hands on their crotch, which decreases the frequency of that behavior in the future.

Why it matters: Some considerations regarding positive punishment also apply to negative punishment. One additional consideration when using negative punishment is that the client should also have plenty of opportunities to earn reinforcers, because otherwise it can become relatively easy to “take things away” until there is nothing left to lose.

Click here for a free quiz on Section B content!

Share this:.

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- Members Newsfeed

What is a Presentation Punishment?

- Behavior Management

This is the act of using unpalatable stimuli to decrease the frequent occurrence of a behavior. This causes such an individual to not want to engage in such behaviors to avoid the consequence in the future. This is adding something to the mix that’ll lead to an unpleasant consequence. Using a presentation punishment might be beneficial in particular circumstances, but it’s just one part of the equation. Guiding the kids toward more appropriate, alternative behaviors is also needed.

All actions have consequences, and presentation punishment can only be a natural consequence of a particular action. For instance, if kids touch a hot oven, they’ll burn their hands. If they consume whipped cream that has spoiled as they hid it below their bed, they’ll have a stomachache. While these experiences are unpleasant, they serve as important teaching moments. Just as one would, kids may be inclined to modify their behavior to keep away from the consequence. When selecting a punishment, parents should consider punishing the behavior, not the kid.

Some examples of common presentation punishments include:

Writing: This method is often utilized in schools. The kids are obligated to write an essay on their behavior or write the same sentence many times.

Grabbing or hand slapping: This might instinctively occur at the moment. The parents might lightly slap a kid’s hand, reaching for a container of boiling water on the oven, or who’s pulling a sibling’s hair. The parents may forcefully pull or grab a kid who’s about to encounter traffic.

Chores: Many parents use chores as a method of punishment. A kid who smears all over the table or scribbles on the wall might be asked to clean it up or carry out other household tasks.

Rules: Few individuals crave more rules. Incorporating additional rules may be the incentive to modify behavior for the kid who frequently misbehaves.

According to a 2016 review of 50 years of research, the more the parents spank kids, the more likely they’re to disobey them. It might increase aggression and antisocial behavior. It might also contribute to mental and cognitive health problems. When it comes to hitting with a ruler, spanking, or other types of physical punishment, they aren’t recommended. Children are pretty good at discovering loopholes. They tend to discover equally undesired behaviors unless parents teach them alternative ones.

Positive punishment is when the parents add a consequence to undesired behavior to make it less attractive. An example of this is adding more household tasks to the list when the kids neglect their responsibilities. The objective is to motivate the kids to manage their daily chores to avoid a growing list.

It’s important to note that positive punishment is different from positive reinforcement. Positive punishment adds an unwanted consequence following an undesirable behavior. Positive reinforcement is providing a reward when the kids behave well. If parents give the kids an allowance for doing particular chores, that’s positive reinforcement. The objective is to improve the probability of continuing good behavior. These strategies can help the kids develop associations between behaviors and their consequences when used together.

Related Articles

Perfectionism in students can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it…

Separation anxiety is a common challenge faced by teachers, particularly in younger…

Mystery and intrigue aren't just for detective novels – they're also fantastic…

Pedagogue is a social media network where educators can learn and grow. It's a safe space where they can share advice, strategies, tools, hacks, resources, etc., and work together to improve their teaching skills and the academic performance of the students in their charge.

If you want to collaborate with educators from around the globe, facilitate remote learning, etc., sign up for a free account today and start making connections.

Pedagogue is Free Now, and Free Forever!

- New? Start Here

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Registration

Don't you have an account? Register Now! it's really simple and you can start enjoying all the benefits!

We just sent you an Email. Please Open it up to activate your account.

I allow this website to collect and store submitted data.

| You might be using an unsupported or outdated browser. To get the best possible experience please use the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Microsoft Edge to view this website. |

What Is Extortion? Punishment, Types And Meaning

Published: Jul 31, 2024, 9:40am

Table of Contents

What is extortion, types of extortion, extortion vs. blackmail, extortion: state-by-state differences, legal defenses against extortion charges, punishments for extortion, extortion statutes, frequently asked questions (faqs) about extortion.

Extortion is a criminal offense that is usually classified as a property crime. It involves obtaining any items of value, such as money or property, through threats or force.

Extortion is illegal under state statutes across the country. Federal law also prohibits extorting behaviors that impact interstate or foreign commerce.

This guide will explain the offense, common penalties and defenses against the crime.

Extortion is a crime in which a defendant uses force or threats to:

- force a victim to give up something of value

- force a victim to perform an official act the victim has no legal obligation to perform

- force a victim to consent to performing an official act or giving something of value

You may be guilty of this crime simply for intending to force a victim to do any of these things, even if they do not do them.

For example, if you threaten that you will kidnap someone’s child if they don’t give you money, you could still be found guilty of extortion even if they didn’t provide you with a payment.

Legal Definition

The federal government prohibits extortion involving interstate commerce or foreign commerce through a law called the Hobbs Act, while each state has its own statute defining the crime and imposing penalties.

While the law can vary slightly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, generally, the elements of the offense include:

- obtaining, or attempting to obtain, property or other valuable items from someone else or causing, or trying to cause, someone else to perform an official act

- inducing the desired behavior through the wrongful use of force or fear or by pretending you have an official right to force them to act. This can include threats against the individual, their business, their family or their reputation, such as threatening to accuse them of a crime.

The penalty is often determined based on the value of the extorted property. Depending on the value, the offense could be either a misdemeanor or a felony.

Meaning of Extortion

The meaning of extortion is simple. Defendants commit extortion if they engage in threatening behavior or use force to make someone do an official act or give them something valuable. This can include threats against the victim or threats to harm the victim’s friends, family or business.

This offense can take different forms. Here are some different types of illegal extorting behavior.

Blackmail can sometimes be prosecuted under extortion statutes or as a separate offense.

It involves a threat to reveal private or sensitive information, a threat to falsely accuse someone of a crime or a threat to report someone’s involvement in a crime. The blackmailer says they will release this damaging information if the victim doesn’t perform some action or provide something of value.

Cyberextortion

Cyberextortion can involve using ransomware to encrypt a victim’s files and refuse to release them until the victim pays a ransom. Criminals often target big businesses with these schemes.

Protection involves promising to prevent or protect someone from harm in exchange for receiving valuable items. The promise carries the implicit threat that harm will befall the victim if protection isn’t purchased. An example would be if the leader of a street gang promises to protect a business from becoming a gang target if the owner gives them a percentage of profits.

Blackmail is sometimes treated as a form of extortion and is sometimes treated as a separate offense.

The key distinguishing feature is that blackmail involves a threat to reveal sensitive or damaging information or to make false accusations of criminal activity or wrongdoing. This threat is used to convince someone to provide something of value or take a specific action. Extortion uses threats of violence to accomplish the same purpose.

State laws can differ in their definition of extortion and the penalties imposed for the crime. Let’s look at some examples.

Virginia defines the offense as doing any of the following to extort money, property or other items of value:

- threatening injury to the character, person, or property of another

- accusing someone of an offense

- threatening to report someone as being illegally in the United States

- destroying, hiding, confiscating or withholding anyone’s immigration documents or government IDs (or threatening to do so)

Engaging in these wrongful behaviors is a class five felony.

In West Virginia, on the other hand, extortion is defined as engaging in any of the following behaviors to obtain anything of value:

- threatening injury to the character, person or property of another person or their spouse or child

- threatening to accuse someone of a criminal offense

If the extortion works and the victim provides something of value, the defendant who engaged in the threats is guilty of a felony in West Virginia. If the victim does not provide something of value and the defendant fails in the extortion, the defendant would be convicted of a misdemeanor.

Because the law is so varied, it is important to speak with a local criminal defense attorney if you have been accused of extortion.

A defendant accused of this crime could raise many possible defenses, including the following.

Insufficient Evidence

A prosecutor must prove every element of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt. If they fail to do so, you cannot be convicted.

Mistake of Fact

If you can show the police or prosecutors made an error, you shouldn’t be convicted.

Lack of Intent

This crime is an intent crime. A defendant must have engaged in threatening behavior with the goal of extorting something from the victim. If a defendant shows that their goal wasn’t to threaten to convince the victim to provide valuable items or to take certain actions, then they should not be found guilty of extortion.

Punishments for extortion vary by state and can be impacted by the value of the items extorted. The crime could be a misdemeanor offense or a felony, and penalties could include:

- victim restitution

- community service

The U.S. government prohibits extortion affecting foreign or interstate commerce in the Hobbs Act . The act is often used to prosecute street crimes, criminals, public corruption and corruption involving members of labor unions.

Individual states have their statutes within their penal codes. A local criminal defense attorney can provide insight into what laws apply to prohibit this crime in your jurisdiction.

What are threats of extortion?

Any threat against an individual or against that person’s family, reputation or business could potentially be considered extortion if the goal of the threat is to convince the victim to take some type of action they aren’t obligated to or to provide money or any other items of value.

What is an example of extortion?

An example of extortion would be a criminal gang leader telling a store owner they must pay protection to avoid becoming a target of gang violence. The key elements of extortion include a threat to the victim or the victim’s family, business or reputation to compel the victim to take some action, including providing money or property.

Is extortion ever legal?

It is never legal to use threats of harm against a person, their reputation or their property to try to force them to act in a certain way or to force them to provide items of value to you. The specifics of the crime vary by state, however—in some cases, you could be charged with a misdemeanor and in others, you could face felony charges.

- New York City Personal Injury Lawyers

- Los Angeles Personal Injury Lawyers

- Houston Personal Injury Lawyers

- Atlanta Personal Injury Lawyers

- Chicago Personal Injury Lawyers

- Dallas Personal Injury Lawyers

- Los Angeles Car Accident Lawyers

- Philadelphia Car Accident Lawyers

- NYC Car Accident Lawyers

- Houston Car Accident Lawyers

- Atlanta Car Accident Lawyers

- Houston Truck Accident Lawyers

- Los Angeles Motorcycle Accident Lawyers

- Phoenix Motorcycle Accident Lawyers

- How to File for Divorce

- Divorce Papers & Forms

- How Much Does A Divorce Cost?

- What Is A Divorce Settlement Agreement?

- What Is An Uncontested Divorce?

- Legal Separation Vs. Divorce

- How Does Alimony Work?

- What Is A Prenup?

- Blood Alcohol Level Chart

- First Offense DUI

- Second Offense DUI

- California DUI Laws

- How Much Does A DUI Cost

- What Happens When You Get A DUI?

- DUI Resulting In Death

- DWI Vs. DUI

- OWI Vs. DUI

- Open Container Law

- Implied Consent Law

- 3M Earplug Lawsuit Update

- Roundup Lawsuit Update

- Paraquat Lawsuit Update

- Mirena IUD Lawsuit Update

- Talcum Powder Lawsuit Update

- Juul Lawsuit Update

- Essure Lawsuit Update

- Paragard Lawsuit Update

What Is An Arraignment Hearing? 2024 Guide

What Is Insurance Fraud? Legal Definition And Basics

What Is Perjury? Definition, Elements And Examples

Best Criminal Defense Lawyers Arlington, TX Of 2024

Best Criminal Defense Lawyers Albuquerque, NM Of 2024

What Is Petty Theft? Punishment, Types And Meaning

Christy Bieber has a JD from UCLA School of Law and began her career as a college instructor and textbook author. She has been writing full time for over a decade with a focus on making financial and legal topics understandable and fun. Her work has appeared on Forbes, CNN Underscored Money, Investopedia, Credit Karma, The Balance, USA Today, and Yahoo Finance, among others.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.2 Changing Behavior Through Reinforcement and Punishment: Operant Conditioning

Learning objectives.

- Outline the principles of operant conditioning.

- Explain how learning can be shaped through the use of reinforcement schedules and secondary reinforcers.

In classical conditioning the organism learns to associate new stimuli with natural, biological responses such as salivation or fear. The organism does not learn something new but rather begins to perform in an existing behavior in the presence of a new signal. Operant conditioning , on the other hand, is learning that occurs based on the consequences of behavior and can involve the learning of new actions. Operant conditioning occurs when a dog rolls over on command because it has been praised for doing so in the past, when a schoolroom bully threatens his classmates because doing so allows him to get his way, and when a child gets good grades because her parents threaten to punish her if she doesn’t. In operant conditioning the organism learns from the consequences of its own actions.

How Reinforcement and Punishment Influence Behavior: The Research of Thorndike and Skinner

Psychologist Edward L. Thorndike (1874–1949) was the first scientist to systematically study operant conditioning. In his research Thorndike (1898) observed cats who had been placed in a “puzzle box” from which they tried to escape ( Note 7.21 “Video Clip: Thorndike’s Puzzle Box” ). At first the cats scratched, bit, and swatted haphazardly, without any idea of how to get out. But eventually, and accidentally, they pressed the lever that opened the door and exited to their prize, a scrap of fish. The next time the cat was constrained within the box it attempted fewer of the ineffective responses before carrying out the successful escape, and after several trials the cat learned to almost immediately make the correct response.

Observing these changes in the cats’ behavior led Thorndike to develop his law of effect , the principle that responses that create a typically pleasant outcome in a particular situation are more likely to occur again in a similar situation, whereas responses that produce a typically unpleasant outcome are less likely to occur again in the situation (Thorndike, 1911). The essence of the law of effect is that successful responses, because they are pleasurable, are “stamped in” by experience and thus occur more frequently. Unsuccessful responses, which produce unpleasant experiences, are “stamped out” and subsequently occur less frequently.

Video Clip: Thorndike’s Puzzle Box

(click to see video)

When Thorndike placed his cats in a puzzle box, he found that they learned to engage in the important escape behavior faster after each trial. Thorndike described the learning that follows reinforcement in terms of the law of effect.

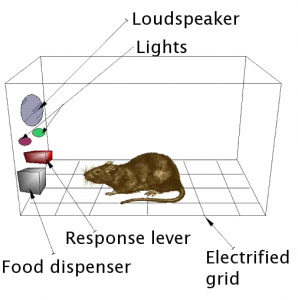

The influential behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) expanded on Thorndike’s ideas to develop a more complete set of principles to explain operant conditioning. Skinner created specially designed environments known as operant chambers (usually called Skinner boxes ) to systemically study learning. A Skinner box (operant chamber) is a structure that is big enough to fit a rodent or bird and that contains a bar or key that the organism can press or peck to release food or water. It also contains a device to record the animal’s responses .

The most basic of Skinner’s experiments was quite similar to Thorndike’s research with cats. A rat placed in the chamber reacted as one might expect, scurrying about the box and sniffing and clawing at the floor and walls. Eventually the rat chanced upon a lever, which it pressed to release pellets of food. The next time around, the rat took a little less time to press the lever, and on successive trials, the time it took to press the lever became shorter and shorter. Soon the rat was pressing the lever as fast as it could eat the food that appeared. As predicted by the law of effect, the rat had learned to repeat the action that brought about the food and cease the actions that did not.

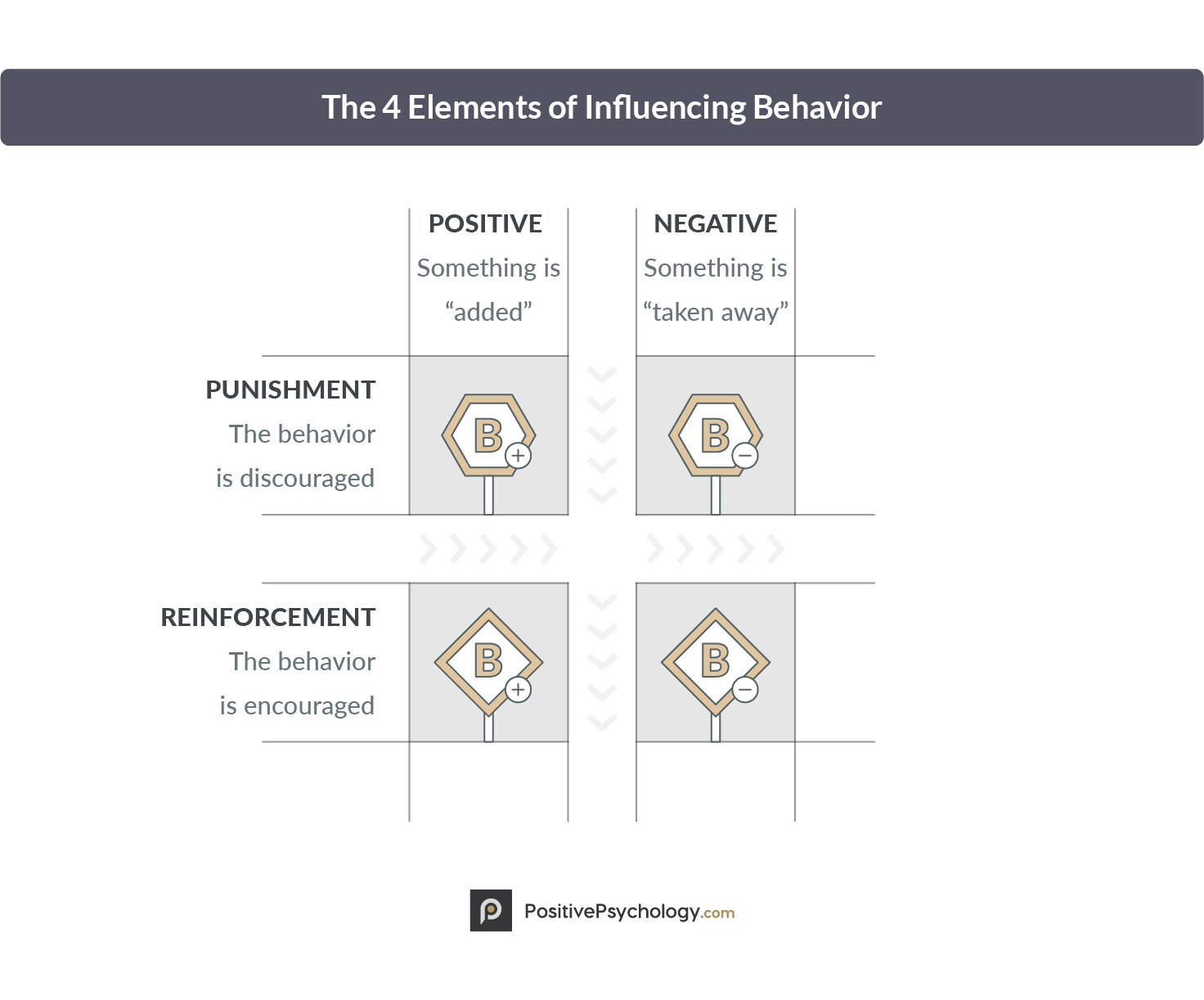

Skinner studied, in detail, how animals changed their behavior through reinforcement and punishment, and he developed terms that explained the processes of operant learning ( Table 7.1 “How Positive and Negative Reinforcement and Punishment Influence Behavior” ). Skinner used the term reinforcer to refer to any event that strengthens or increases the likelihood of a behavior and the term punisher to refer to any event that weakens or decreases the likelihood of a behavior . And he used the terms positive and negative to refer to whether a reinforcement was presented or removed, respectively. Thus positive reinforcement strengthens a response by presenting something pleasant after the response and negative reinforcement strengthens a response by reducing or removing something unpleasant . For example, giving a child praise for completing his homework represents positive reinforcement, whereas taking aspirin to reduced the pain of a headache represents negative reinforcement. In both cases, the reinforcement makes it more likely that behavior will occur again in the future.

Figure 7.6 Rat in a Skinner Box

B. F. Skinner used a Skinner box to study operant learning. The box contains a bar or key that the organism can press to receive food and water, and a device that records the organism’s responses.

Andreas1 – Skinner box – CC BY-SA 3.0.

Table 7.1 How Positive and Negative Reinforcement and Punishment Influence Behavior

| Operant conditioning term | Description | Outcome | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive reinforcement | Add or increase a pleasant stimulus | Behavior is strengthened | Giving a student a prize after he gets an A on a test |

| Negative reinforcement | Reduce or remove an unpleasant stimulus | Behavior is strengthened | Taking painkillers that eliminate pain increases the likelihood that you will take painkillers again |

| Positive punishment | Present or add an unpleasant stimulus | Behavior is weakened | Giving a student extra homework after she misbehaves in class |

| Negative punishment | Reduce or remove a pleasant stimulus | Behavior is weakened | Taking away a teen’s computer after he misses curfew |

Reinforcement, either positive or negative, works by increasing the likelihood of a behavior. Punishment, on the other hand, refers to any event that weakens or reduces the likelihood of a behavior . Positive punishment weakens a response by presenting something unpleasant after the response , whereas negative punishment weakens a response by reducing or removing something pleasant . A child who is grounded after fighting with a sibling (positive punishment) or who loses out on the opportunity to go to recess after getting a poor grade (negative punishment) is less likely to repeat these behaviors.

Although the distinction between reinforcement (which increases behavior) and punishment (which decreases it) is usually clear, in some cases it is difficult to determine whether a reinforcer is positive or negative. On a hot day a cool breeze could be seen as a positive reinforcer (because it brings in cool air) or a negative reinforcer (because it removes hot air). In other cases, reinforcement can be both positive and negative. One may smoke a cigarette both because it brings pleasure (positive reinforcement) and because it eliminates the craving for nicotine (negative reinforcement).

It is also important to note that reinforcement and punishment are not simply opposites. The use of positive reinforcement in changing behavior is almost always more effective than using punishment. This is because positive reinforcement makes the person or animal feel better, helping create a positive relationship with the person providing the reinforcement. Types of positive reinforcement that are effective in everyday life include verbal praise or approval, the awarding of status or prestige, and direct financial payment. Punishment, on the other hand, is more likely to create only temporary changes in behavior because it is based on coercion and typically creates a negative and adversarial relationship with the person providing the reinforcement. When the person who provides the punishment leaves the situation, the unwanted behavior is likely to return.

Creating Complex Behaviors Through Operant Conditioning

Perhaps you remember watching a movie or being at a show in which an animal—maybe a dog, a horse, or a dolphin—did some pretty amazing things. The trainer gave a command and the dolphin swam to the bottom of the pool, picked up a ring on its nose, jumped out of the water through a hoop in the air, dived again to the bottom of the pool, picked up another ring, and then took both of the rings to the trainer at the edge of the pool. The animal was trained to do the trick, and the principles of operant conditioning were used to train it. But these complex behaviors are a far cry from the simple stimulus-response relationships that we have considered thus far. How can reinforcement be used to create complex behaviors such as these?

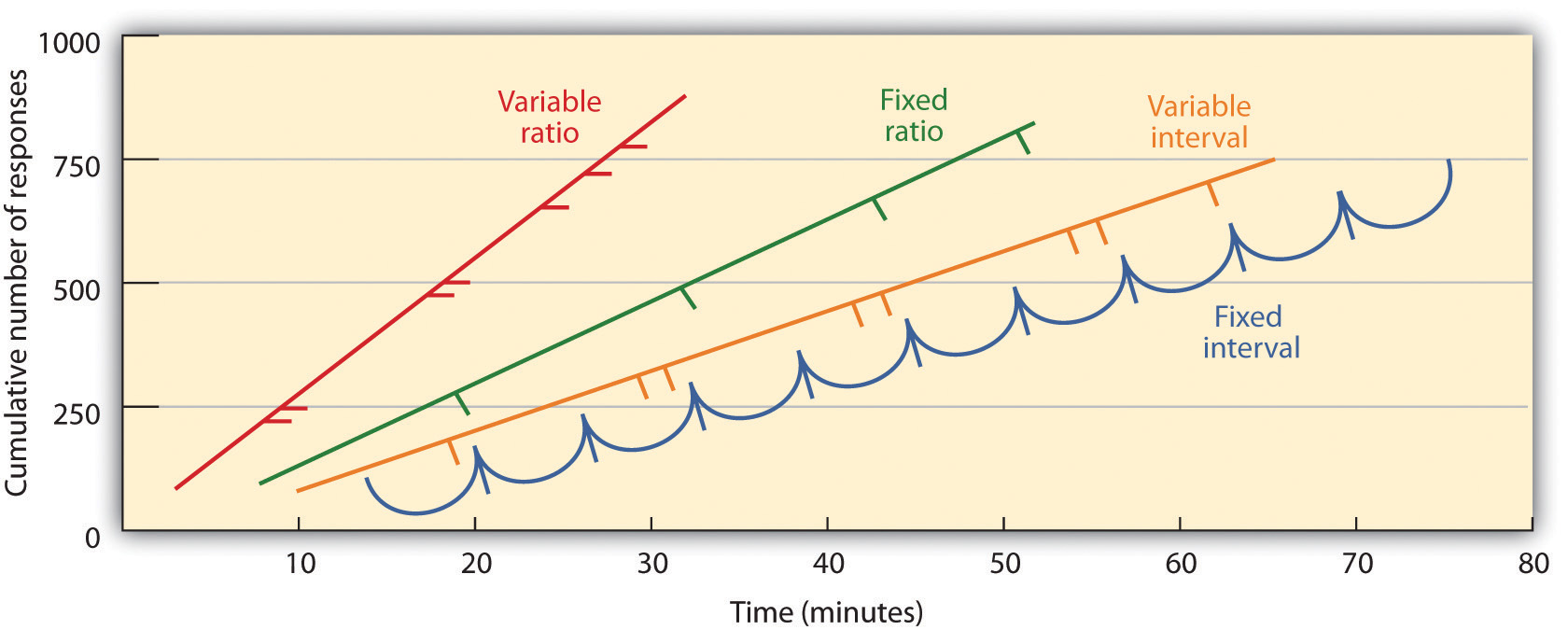

One way to expand the use of operant learning is to modify the schedule on which the reinforcement is applied. To this point we have only discussed a continuous reinforcement schedule , in which the desired response is reinforced every time it occurs ; whenever the dog rolls over, for instance, it gets a biscuit. Continuous reinforcement results in relatively fast learning but also rapid extinction of the desired behavior once the reinforcer disappears. The problem is that because the organism is used to receiving the reinforcement after every behavior, the responder may give up quickly when it doesn’t appear.

Most real-world reinforcers are not continuous; they occur on a partial (or intermittent) reinforcement schedule — a schedule in which the responses are sometimes reinforced, and sometimes not . In comparison to continuous reinforcement, partial reinforcement schedules lead to slower initial learning, but they also lead to greater resistance to extinction. Because the reinforcement does not appear after every behavior, it takes longer for the learner to determine that the reward is no longer coming, and thus extinction is slower. The four types of partial reinforcement schedules are summarized in Table 7.2 “Reinforcement Schedules” .

Table 7.2 Reinforcement Schedules

| Reinforcement schedule | Explanation | Real-world example |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed-ratio | Behavior is reinforced after a specific number of responses | Factory workers who are paid according to the number of products they produce |

| Variable-ratio | Behavior is reinforced after an average, but unpredictable, number of responses | Payoffs from slot machines and other games of chance |

| Fixed-interval | Behavior is reinforced for the first response after a specific amount of time has passed | People who earn a monthly salary |

| Variable-interval | Behavior is reinforced for the first response after an average, but unpredictable, amount of time has passed | Person who checks voice mail for messages |

Partial reinforcement schedules are determined by whether the reinforcement is presented on the basis of the time that elapses between reinforcement (interval) or on the basis of the number of responses that the organism engages in (ratio), and by whether the reinforcement occurs on a regular (fixed) or unpredictable (variable) schedule. In a fixed-interval schedule , reinforcement occurs for the first response made after a specific amount of time has passed . For instance, on a one-minute fixed-interval schedule the animal receives a reinforcement every minute, assuming it engages in the behavior at least once during the minute. As you can see in Figure 7.7 “Examples of Response Patterns by Animals Trained Under Different Partial Reinforcement Schedules” , animals under fixed-interval schedules tend to slow down their responding immediately after the reinforcement but then increase the behavior again as the time of the next reinforcement gets closer. (Most students study for exams the same way.) In a variable-interval schedule , the reinforcers appear on an interval schedule, but the timing is varied around the average interval, making the actual appearance of the reinforcer unpredictable . An example might be checking your e-mail: You are reinforced by receiving messages that come, on average, say every 30 minutes, but the reinforcement occurs only at random times. Interval reinforcement schedules tend to produce slow and steady rates of responding.

Figure 7.7 Examples of Response Patterns by Animals Trained Under Different Partial Reinforcement Schedules

Schedules based on the number of responses (ratio types) induce greater response rate than do schedules based on elapsed time (interval types). Also, unpredictable schedules (variable types) produce stronger responses than do predictable schedules (fixed types).

Adapted from Kassin, S. (2003). Essentials of psychology . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Retrieved from Essentials of Psychology Prentice Hall Companion Website: http://wps.prenhall.com/hss_kassin_essentials_1/15/3933/1006917.cw/index.html .

In a fixed-ratio schedule , a behavior is reinforced after a specific number of responses . For instance, a rat’s behavior may be reinforced after it has pressed a key 20 times, or a salesperson may receive a bonus after she has sold 10 products. As you can see in Figure 7.7 “Examples of Response Patterns by Animals Trained Under Different Partial Reinforcement Schedules” , once the organism has learned to act in accordance with the fixed-reinforcement schedule, it will pause only briefly when reinforcement occurs before returning to a high level of responsiveness. A variable-ratio schedule provides reinforcers after a specific but average number of responses . Winning money from slot machines or on a lottery ticket are examples of reinforcement that occur on a variable-ratio schedule. For instance, a slot machine may be programmed to provide a win every 20 times the user pulls the handle, on average. As you can see in Figure 7.8 “Slot Machine” , ratio schedules tend to produce high rates of responding because reinforcement increases as the number of responses increase.

Figure 7.8 Slot Machine

Slot machines are examples of a variable-ratio reinforcement schedule.

Jeff Kubina – Slot Machine – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Complex behaviors are also created through shaping , the process of guiding an organism’s behavior to the desired outcome through the use of successive approximation to a final desired behavior . Skinner made extensive use of this procedure in his boxes. For instance, he could train a rat to press a bar two times to receive food, by first providing food when the animal moved near the bar. Then when that behavior had been learned he would begin to provide food only when the rat touched the bar. Further shaping limited the reinforcement to only when the rat pressed the bar, to when it pressed the bar and touched it a second time, and finally, to only when it pressed the bar twice. Although it can take a long time, in this way operant conditioning can create chains of behaviors that are reinforced only when they are completed.

Reinforcing animals if they correctly discriminate between similar stimuli allows scientists to test the animals’ ability to learn, and the discriminations that they can make are sometimes quite remarkable. Pigeons have been trained to distinguish between images of Charlie Brown and the other Peanuts characters (Cerella, 1980), and between different styles of music and art (Porter & Neuringer, 1984; Watanabe, Sakamoto & Wakita, 1995).

Behaviors can also be trained through the use of secondary reinforcers . Whereas a primary reinforcer includes stimuli that are naturally preferred or enjoyed by the organism, such as food, water, and relief from pain , a secondary reinforcer (sometimes called conditioned reinforcer ) is a neutral event that has become associated with a primary reinforcer through classical conditioning . An example of a secondary reinforcer would be the whistle given by an animal trainer, which has been associated over time with the primary reinforcer, food. An example of an everyday secondary reinforcer is money. We enjoy having money, not so much for the stimulus itself, but rather for the primary reinforcers (the things that money can buy) with which it is associated.

Key Takeaways

- Edward Thorndike developed the law of effect: the principle that responses that create a typically pleasant outcome in a particular situation are more likely to occur again in a similar situation, whereas responses that produce a typically unpleasant outcome are less likely to occur again in the situation.

- B. F. Skinner expanded on Thorndike’s ideas to develop a set of principles to explain operant conditioning.

- Positive reinforcement strengthens a response by presenting something that is typically pleasant after the response, whereas negative reinforcement strengthens a response by reducing or removing something that is typically unpleasant.

- Positive punishment weakens a response by presenting something typically unpleasant after the response, whereas negative punishment weakens a response by reducing or removing something that is typically pleasant.

- Reinforcement may be either partial or continuous. Partial reinforcement schedules are determined by whether the reinforcement is presented on the basis of the time that elapses between reinforcements (interval) or on the basis of the number of responses that the organism engages in (ratio), and by whether the reinforcement occurs on a regular (fixed) or unpredictable (variable) schedule.

- Complex behaviors may be created through shaping, the process of guiding an organism’s behavior to the desired outcome through the use of successive approximation to a final desired behavior.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Give an example from daily life of each of the following: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, negative punishment.

- Consider the reinforcement techniques that you might use to train a dog to catch and retrieve a Frisbee that you throw to it.

Watch the following two videos from current television shows. Can you determine which learning procedures are being demonstrated?

- The Office : http://www.break.com/usercontent/2009/11/the-office-altoid- experiment-1499823

- The Big Bang Theory : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JA96Fba-WHk

Cerella, J. (1980). The pigeon’s analysis of pictures. Pattern Recognition, 12 , 1–6.

Porter, D., & Neuringer, A. (1984). Music discriminations by pigeons. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 10 (2), 138–148;

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Thorndike, E. L. (1911). Animal intelligence: Experimental studies. New York, NY: Macmillan. Retrieved from http://www.archive.org/details/animalintelligen00thor

Watanabe, S., Sakamoto, J., & Wakita, M. (1995). Pigeons’ discrimination of painting by Monet and Picasso. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 63 (2), 165–174.

Introduction to Psychology Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Positive Punishment and Operant Conditioning

Positive punishment is a concept employed in B.F. Skinner's theory of operant conditioning . But how exactly does the positive punishment process work? The goal of any type of punishment is to decrease the behavior that it follows. Positive punishment involves presenting an unfavorable outcome or event following an undesirable behavior.

When the subject performs an unwanted action, some type of negative outcome is purposefully applied. For example, if you are training your dog to stop chewing on your favorite slippers, you may scold the animal every time you catch them gnawing on your footwear. Because the dog exhibited an unwanted behavior (chewing on your shoes), you applied an aversive outcome (giving the dog a verbal scolding).

The concept of positive punishment can be difficult to remember, especially because the name is contradictory. How can punishment be positive? The easiest way to remember this concept is to note that it involves an aversive stimulus that is added to the situation. For this reason, positive punishment is sometimes referred to as punishment by the application.

You will likely be able to notice positive punishment in your day-to-day life. For example:

- As a result of driving over the speed limit through a school zone, you get pulled over by a police officer and receive a ticket.

- As a result of your cell phone ringing in the middle of a class lecture, you are scolded by your teacher for not turning your phone off before class.

- As a result of wearing your baseball cap to class, you are reprimanded by your instructor for violating your school's dress code.

The teacher reprimanding you for breaking the dress code, the officer issuing the speeding ticket, and the teacher scolding you for not turning off are examples of aversive stimuli that are meant to decrease the behavior that they follow.

In all of the examples above, positive punishment is purposely administered by another person. However, positive punishment can also occur as a natural consequence of a behavior. Because you experienced a negative outcome as a result of your behavior, you become less likely to engage in those actions again in the future.

Spanking as Positive Punishment

While positive punishment can be effective in some situations, B.F. Skinner noted that its use must be weighed against any potential negative effects. One of the best-known examples of positive punishment is spanking, defined as striking a child across the buttocks with an open hand. According to a nationwide poll, 72% of adults reported that it was “OK to spank a child.”

Some researchers have suggested mild, occasional spanking is not harmful, especially when used along with other forms of discipline. However, in one large 2013 meta-analysis of previous research, psychologist Elizabeth Gershoff found that spanking was associated with poor parent-child relationships as well as with increases in antisocial behavior, delinquency, and aggressiveness. More recent studies that controlled for a variety of confounding variables also found similar results.

While positive punishment has its uses, many experts suggested that other methods of operant conditioning are often more effective for changing behaviors in the short-term and long-term. Perhaps most importantly, many of these other methods come without the potentially negative consequences of positive punishment.

Taylor CA, Manganello JA, Lee SJ, Rice JC. Mothers' spanking of 3-year-old children and subsequent risk of children's aggressive behavior . Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1057-65.

Gershoff ET. Spanking and Child Development: We Know Enough Now To Stop Hitting Our Children . Child Dev Perspect . 2013;7(3):133‐137. doi:10.1111/cdep.12038

Sege RD, Siegel BS; COUNCIL ON CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT; COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH. Effective Discipline to Raise Healthy Children . Pediatrics . 2018;142(6):e20183112. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3112

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

You may also check your understanding of the material on the Ablongman web site. Click on the Publisher Help Site button.

Presentation of Theoretical Construct

Lecture Information : Types of Consequences

| Behavior Encouraged | Behavior Suppressed | |

| Stimulus Presented | Positive Reinforcement - Reward | Presentation Punishment - Aversive |

|

|

| |

| Stimulus Removed | Negative Reinforcement - Escape | Removal Punishment - Take away a privilege |

|

|

|

Negative Reinforcement: One of the most common mistakes concerning the different types of behaviorism's consequences is to confuse "Negative Reinforcement" with "Punishment. Even though the term has the word "Negative" in the title, it is still a reward for the actor. You are in fact subtracting an annoyance from their environment. In this way it is very much like the old mathematical rule of a "Negative" times a "Negative" is a positive. This is a mistake that many practicing teachers make as well.

Authority Figure Intentions: The second topic of concern for any discussion of rewards and punishments from a behavioral point of view is the fact that it does not matter one wit what you, as the authority figure, intend to accomplish; it only matters how it is taken by the receiver of the consequence. As a teacher you can fully intend to punish a student with a huge tongue-lashing, a vein-in-the-forehead-popping tirade, only to have the students be rather amused by the outburst. They are very likely to try and get your goat again. In other words, you just accidentally reinforced that exact behavior that you wanted to quell.

The opposite is also true. You can point out to the whole class how well Suzy has organized her desk to perform the project calling everybody's attention to her and her beautiful desk. She then turns bright red in the face and slinks to the back of the with her hand over her mouth. You have just punished her behavior. She is now less likely be organized next time. My point in this is that it is very, very easy to make a mistake with rewards and punishments. You can only be sure of a success by the impact on the behavior.

Back to Lesson 8 Index

Reinforcement and Punishment

Learning objectives.

- Explain the difference between reinforcement and punishment (including positive and negative reinforcement and positive and negative punishment)

- Define shaping

- Differentiate between primary and secondary reinforcers

In discussing operant conditioning, we use several everyday words—positive, negative, reinforcement, and punishment—in a specialized manner. In operant conditioning, positive and negative do not mean good and bad. Instead, positive means you are adding something, and negative means you are taking something away. Reinforcement means you are increasing a behavior, and punishment means you are decreasing a behavior. Reinforcement can be positive or negative, and punishment can also be positive or negative. All reinforcers (positive or negative) increase the likelihood of a behavioral response. All punishers (positive or negative) decrease the likelihood of a behavioral response. Now let’s combine these four terms: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment (Table 1).

| Something is to the likelihood of a behavior. | Something is to the likelihood of a behavior. | |

| Something is to the likelihood of a behavior. | Something is to the likelihood of a behavior. |

Reinforcement

The most effective way to teach a person or animal a new behavior is with positive reinforcement. In positive reinforcement , a desirable stimulus is added to increase a behavior.

For example, you tell your five-year-old son, Jerome, that if he cleans his room, he will get a toy. Jerome quickly cleans his room because he wants a new art set. Let’s pause for a moment. Some people might say, “Why should I reward my child for doing what is expected?” But in fact we are constantly and consistently rewarded in our lives. Our paychecks are rewards, as are high grades and acceptance into our preferred school. Being praised for doing a good job and for passing a driver’s test is also a reward. Positive reinforcement as a learning tool is extremely effective. It has been found that one of the most effective ways to increase achievement in school districts with below-average reading scores was to pay the children to read. Specifically, second-grade students in Dallas were paid $2 each time they read a book and passed a short quiz about the book. The result was a significant increase in reading comprehension (Fryer, 2010). What do you think about this program? If Skinner were alive today, he would probably think this was a great idea. He was a strong proponent of using operant conditioning principles to influence students’ behavior at school. In fact, in addition to the Skinner box, he also invented what he called a teaching machine that was designed to reward small steps in learning (Skinner, 1961)—an early forerunner of computer-assisted learning. His teaching machine tested students’ knowledge as they worked through various school subjects. If students answered questions correctly, they received immediate positive reinforcement and could continue; if they answered incorrectly, they did not receive any reinforcement. The idea was that students would spend additional time studying the material to increase their chance of being reinforced the next time (Skinner, 1961).

In negative reinforcement , an undesirable stimulus is removed to increase a behavior. For example, car manufacturers use the principles of negative reinforcement in their seatbelt systems, which go “beep, beep, beep” until you fasten your seatbelt. The annoying sound stops when you exhibit the desired behavior, increasing the likelihood that you will buckle up in the future. Negative reinforcement is also used frequently in horse training. Riders apply pressure—by pulling the reins or squeezing their legs—and then remove the pressure when the horse performs the desired behavior, such as turning or speeding up. The pressure is the negative stimulus that the horse wants to remove.

Link to Learning

Watch this clip from The Big Bang Theory to see Sheldon Cooper explain the commonly confused terms of negative reinforcement and punishment.

Many people confuse negative reinforcement with punishment in operant conditioning, but they are two very different mechanisms. Remember that reinforcement, even when it is negative, always increases a behavior. In contrast, punishment always decreases a behavior. In positive punishment, you add an undesirable stimulus to decrease a behavior. An example of positive punishment is scolding a student to get the student to stop texting in class. In this case, a stimulus (the reprimand) is added in order to decrease the behavior (texting in class). In negative punishment , you remove a pleasant stimulus to decrease a behavior. For example, when a child misbehaves, a parent can take away a favorite toy. In this case, a stimulus (the toy) is removed in order to decrease the behavior.

Punishment, especially when it is immediate, is one way to decrease undesirable behavior. For example, imagine your four year-old son, Brandon, hit his younger brother. You have Brandon write 50 times “I will not hit my brother” (positive punishment). Chances are he won’t repeat this behavior. While strategies like this are common today, in the past children were often subject to physical punishment, such as spanking. It’s important to be aware of some of the drawbacks in using physical punishment on children. First, punishment may teach fear. Brandon may become fearful of the hitting, but he also may become fearful of the person who delivered the punishment—you, his parent. Similarly, children who are punished by teachers may come to fear the teacher and try to avoid school (Gershoff et al., 2010). Consequently, most schools in the United States have banned corporal punishment. Second, punishment may cause children to become more aggressive and prone to antisocial behavior and delinquency (Gershoff, 2002). They see their parents resort to spanking when they become angry and frustrated, so, in turn, they may act out this same behavior when they become angry and frustrated. For example, because you spank Margot when you are angry with her for her misbehavior, she might start hitting her friends when they won’t share their toys.

While positive punishment can be effective in some cases, Skinner suggested that the use of punishment should be weighed against the possible negative effects. Today’s psychologists and parenting experts favor reinforcement over punishment—they recommend that you catch your child doing something good and reward her for it.

Make sure you understand the distinction between negative reinforcement and punishment in the following video:

You can view the transcript for “Learning: Negative Reinforcement vs. Punishment” here (opens in new window) .

Still confused? Watch the following short clip for another example and explanation of positive and negative reinforcement as well as positive and negative punishment.

You can view the transcript for “Operant Conditioning” here (opens in new window) .

In his operant conditioning experiments, Skinner often used an approach called shaping. Instead of rewarding only the target behavior, in shaping , we reward successive approximations of a target behavior. Why is shaping needed? Remember that in order for reinforcement to work, the organism must first display the behavior. Shaping is needed because it is extremely unlikely that an organism will display anything but the simplest of behaviors spontaneously. In shaping, behaviors are broken down into many small, achievable steps. The specific steps used in the process are the following: Reinforce any response that resembles the desired behavior. Then reinforce the response that more closely resembles the desired behavior. You will no longer reinforce the previously reinforced response. Next, begin to reinforce the response that even more closely resembles the desired behavior. Continue to reinforce closer and closer approximations of the desired behavior. Finally, only reinforce the desired behavior.

Shaping is often used in teaching a complex behavior or chain of behaviors. Skinner used shaping to teach pigeons not only such relatively simple behaviors as pecking a disk in a Skinner box, but also many unusual and entertaining behaviors, such as turning in circles, walking in figure eights, and even playing ping pong; the technique is commonly used by animal trainers today. An important part of shaping is stimulus discrimination. Recall Pavlov’s dogs—he trained them to respond to the tone of a bell, and not to similar tones or sounds. This discrimination is also important in operant conditioning and in shaping behavior.

Here is a brief video of Skinner’s pigeons playing ping pong.

You can view the transcript for “BF Skinner Foundation – Pigeon Ping Pong Clip” here (opens in new window) .

It’s easy to see how shaping is effective in teaching behaviors to animals, but how does shaping work with humans? Let’s consider parents whose goal is to have their child learn to clean his room. They use shaping to help him master steps toward the goal. Instead of performing the entire task, they set up these steps and reinforce each step. First, he cleans up one toy. Second, he cleans up five toys. Third, he chooses whether to pick up ten toys or put his books and clothes away. Fourth, he cleans up everything except two toys. Finally, he cleans his entire room.

Primary and Secondary Reinforcers

Rewards such as stickers, praise, money, toys, and more can be used to reinforce learning. Let’s go back to Skinner’s rats again. How did the rats learn to press the lever in the Skinner box? They were rewarded with food each time they pressed the lever. For animals, food would be an obvious reinforcer.

What would be a good reinforce for humans? For your daughter Sydney, it was the promise of a toy if she cleaned her room. How about Joaquin, the soccer player? If you gave Joaquin a piece of candy every time he made a goal, you would be using a primary reinforcer. Primary reinforcers are reinforcers that have innate reinforcing qualities. These kinds of reinforcers are not learned. Water, food, sleep, shelter, sex, and touch, among others, are primary reinforcers . Pleasure is also a primary reinforcer. Organisms do not lose their drive for these things. For most people, jumping in a cool lake on a very hot day would be reinforcing and the cool lake would be innately reinforcing—the water would cool the person off (a physical need), as well as provide pleasure.

A secondary reinforcer has no inherent value and only has reinforcing qualities when linked with a primary reinforcer. Praise, linked to affection, is one example of a secondary reinforcer, as when you called out “Great shot!” every time Joaquin made a goal. Another example, money, is only worth something when you can use it to buy other things—either things that satisfy basic needs (food, water, shelter—all primary reinforcers) or other secondary reinforcers. If you were on a remote island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and you had stacks of money, the money would not be useful if you could not spend it. What about the stickers on the behavior chart? They also are secondary reinforcers.

Sometimes, instead of stickers on a sticker chart, a token is used. Tokens, which are also secondary reinforcers, can then be traded in for rewards and prizes. Entire behavior management systems, known as token economies, are built around the use of these kinds of token reinforcers. Token economies have been found to be very effective at modifying behavior in a variety of settings such as schools, prisons, and mental hospitals. For example, a study by Cangi and Daly (2013) found that use of a token economy increased appropriate social behaviors and reduced inappropriate behaviors in a group of autistic school children. Autistic children tend to exhibit disruptive behaviors such as pinching and hitting. When the children in the study exhibited appropriate behavior (not hitting or pinching), they received a “quiet hands” token. When they hit or pinched, they lost a token. The children could then exchange specified amounts of tokens for minutes of playtime.

Everyday Connection: Behavior Modification in Children

Parents and teachers often use behavior modification to change a child’s behavior. Behavior modification uses the principles of operant conditioning to accomplish behavior change so that undesirable behaviors are switched for more socially acceptable ones. Some teachers and parents create a sticker chart, in which several behaviors are listed (Figure 1). Sticker charts are a form of token economies, as described in the text. Each time children perform the behavior, they get a sticker, and after a certain number of stickers, they get a prize, or reinforcer. The goal is to increase acceptable behaviors and decrease misbehavior. Remember, it is best to reinforce desired behaviors, rather than to use punishment. In the classroom, the teacher can reinforce a wide range of behaviors, from students raising their hands, to walking quietly in the hall, to turning in their homework. At home, parents might create a behavior chart that rewards children for things such as putting away toys, brushing their teeth, and helping with dinner. In order for behavior modification to be effective, the reinforcement needs to be connected with the behavior; the reinforcement must matter to the child and be done consistently.

Time-out is another popular technique used in behavior modification with children. It operates on the principle of negative punishment. When a child demonstrates an undesirable behavior, she is removed from the desirable activity at hand (Figure 2). For example, say that Sophia and her brother Mario are playing with building blocks. Sophia throws some blocks at her brother, so you give her a warning that she will go to time-out if she does it again. A few minutes later, she throws more blocks at Mario. You remove Sophia from the room for a few minutes. When she comes back, she doesn’t throw blocks.

There are several important points that you should know if you plan to implement time-out as a behavior modification technique. First, make sure the child is being removed from a desirable activity and placed in a less desirable location. If the activity is something undesirable for the child, this technique will backfire because it is more enjoyable for the child to be removed from the activity. Second, the length of the time-out is important. The general rule of thumb is one minute for each year of the child’s age. Sophia is five; therefore, she sits in a time-out for five minutes. Setting a timer helps children know how long they have to sit in time-out. Finally, as a caregiver, keep several guidelines in mind over the course of a time-out: remain calm when directing your child to time-out; ignore your child during time-out (because caregiver attention may reinforce misbehavior); and give the child a hug or a kind word when time-out is over.

Think It Over

- Explain the difference between negative reinforcement and punishment, and provide several examples of each based on your own experiences.

- Think of a behavior that you have that you would like to change. How could you use behavior modification, specifically positive reinforcement, to change your behavior? What is your positive reinforcer?

CC licensed content, Original

- Modification and adaptation, addition of Big Bang Learning example. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Operant conditioning interactive. Authored by : Jessica Traylor for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Operant Conditioning. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/6-3-operant-conditioning . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

All rights reserved content

- BF Skinner Foundation – Pigeon Ping Pong Clip. Provided by : bfskinnerfoundation. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vGazyH6fQQ4 . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Learning: Negative Reinforcement vs. Punishment. Authored by : ByPass Publishing. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=imkbuKomPXI . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Operant Conditioning. Authored by : Dr. Mindy Rutherford. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSHJbIJK9TI . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

implementation of a consequence in order to increase a behavior

adding a desirable stimulus to increase a behavior

implementation of a consequence in order to decrease a behavior

adding an undesirable stimulus to stop or decrease a behavior

taking away a pleasant stimulus to decrease or stop a behavior

rewarding successive approximations toward a target behavior

has innate reinforcing qualities (e.g., food, water, shelter, sex)

has no inherent value unto itself and only has reinforcing qualities when linked with something else (e.g., money, gold stars, poker chips)

General Psychology Copyright © by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 24 July 2021

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Ricardo Pellón 3 &

- Per Holth 4

37 Accesses

Differential reinforcement of other behavior ; Omission training ; Penalty (not technical) ; Response-dependent aversive stimulation ; Response-initiated delays in reinforcement ; Time-out from reinforcement

According to the American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology, punishment is a noun that refers to (1) a physically or psychologically painful, unwanted, or undesirable event or circumstance imposed as a penalty on an actual or perceived wrongdoer; (2) in operant conditioning, the process in which the relationship, or contingency, between a response and some stimulus or circumstance results in the response becoming less probable. The punishing stimulus is called a punisher.

The characterization of events or circumstances as “physically or psychologically painful” is not useful unless the observational basis for these terms is spelled out. Therefore, the standard and most widespread definition of punishment in the behavior-analytic literature refers...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Apel, A. B., & Diller, J. W. (2017). Prison as punishment: A behavior-analytic evaluation of incarceration. The Behavior Analyst, 40 (1), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-016-0081-6 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Azrin, N. H., & Holz, W. C. (1966). Punishment. In W. K. Honig (Ed.), Operant behavior: Areas of research and application (pp. 213–270). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Google Scholar

Estes, W. K. (1944). An experimental study of punishment. Psychological Monographs, 57 (3), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093550 .

Article Google Scholar

Fantino, E. J., & Logan, C. A. (1979). The experimental analysis of behavior: A biological perspective . San Diego: Freeman.

Histed, M. H., Pasupathy, A., & Miller, E. K. (2009). Learning substrates in the primate prefrontal cortex and striatum: Sustained activity related to successful actions. Neuron, 63 (2), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.019 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lerman, D. C., & Vorndran, C. M. (2002). On the status of knowledge for using punishment: Implications for treating behavior disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 35 (4), 431–464. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2002.35-431 .

Pérez-Padilla, Á., & Pellón, R. (2007). Behavioural and pharmacological specificity of the effects of drugs on punished schedule-induced polydipsia. Behavioural Pharmacology, 18 (7), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282f00bdb .

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis . New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior . New York: Macmillan.

Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and dignity . Bungay, Suffolk: Pelican Books.

Thorndike, E. L. (1911). Animal intelligence: experimental studies . New York: Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Thorndike, E. L. (1932). The fundamentals of learning . New York: Teachers College.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Madrid, Spain

Ricardo Pellón

Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ricardo Pellón .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Jennifer Vonk

Department of Psychology, Oakland University Department of Psychology, Rochester, MI, USA

Todd Shackelford

Section Editor information

University of Chicago, Chicago, USA

Peggy Mason

Neurobiology, University of Chicago, Chicago, United States of America

Yuri Vieira Sugano

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Pellón, R., Holth, P. (2021). Punishment. In: Vonk, J., Shackelford, T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_1403-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_1403-1

Received : 11 May 2021

Accepted : 12 May 2021

Published : 24 July 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-47829-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-47829-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Punishment and Its Putative Fallout: A Reappraisal

In his book Coercion and Its Fallout Murray Sidman argued against the use of punishment based on concerns about its shortcomings and side effects. Among his concerns were the temporary nature of response suppression produced by punishment, the dangers of conditioned punishment, increases in escape and avoidance responses, punishment-induced aggression, and the development of countercontrol. This paper revisits Sidman’s arguments about these putative shortcomings and side effects by examining the available data. Although Sidman’s concerns are reasonable and should be considered when using any form of behavioral control, there appears to be a lack of strong empirical support for the notion that these potential problems with punishment are necessarily ubiquitous, long-lasting, or specific to punishment. We describe the need for additional research on punishment in general, and especially on its putative shortcomings and side effects. We also suggest the need for more effective formal theories of punishment that provide a principled account of how, why, and when lasting effects of punishment and its potential side effects might be expected to occur or not. In addition to being necessary for a complete account of behavior, such data and theories might contribute to improved interventions for problems of human concern.

Murray Sidman’s exceptional scientific contributions to the field of behavior analysis are widely recognized (e.g., Ahearn, 2011 ; Arntzen, 2010 ; Holth & Moore, 2010 ; Johnson et al., 2020 ; McIlvane, 2011 ). Among his many contributions, Sidman’s research has had a noteworthy impact on the understanding of aversive control (e.g., Sidman, 1953a , 1953b , 1966 , 1989 , 2000 ). Despite his extensive research in this area, Sidman firmly opposed the use of methods based on aversive control (i.e., coercion), advocating instead for the use of positive reinforcement ( Delprato, 1995 ; Sidman, 1993 , 2011 ). His opposition to the use of coercive methods was especially clear in his book Coercion and its fallout ( Sidman, 1989 / 2000 ), where he referred to negative reinforcement and punishment as the two major categories of coercive control. According to Sidman (1989 / 2000 ), negative reinforcement and punishment work in a complementary manner because a stimulus punishing a response also should increase behavior removing or avoiding that stimulus (i.e., negative reinforcement; e.g., Crosbie, 1998 ). This interdependence between punishment and negative reinforcement was noted by Sidman as one disadvantage of the use of coercive control, with the other being the dangerous side effects of such practices.

It appears that Sidman’s opposition to the use of aversive control and, more specifically to the use of punishment, may have impacted how punishment is viewed and used by both basic and applied behavior analysts (e.g., Ahearn, 2011 ; Holth, 2010 ). There has been an apparent decrease in interest in studying punishment, leaving several empirical and theoretical gaps in the literature (see Critchfield & Rasmussen, 2007 ; Horner, 2002 ; Lerman & Vorndran, 2002 ; Lydon et al., 2015 ; Todorov, 2001 , 2011 ). However, a similar decrease has not necessarily been observed with negative reinforcement (e.g., Baron & Galizio, 2005 , 2006 ; Magoon & Critchfield, 2008 ; Sidman, 2006 ; Thompson & Iwata, 2005 ).

Although Coercion and its fallout ( Sidman, 1989 / 2000 ) was focused broadly on the coercive nature of both punishment and negative reinforcement, the present paper focuses on Sidman’s concerns about the use of punishment. Sidman questioned the effectiveness of punishment in controlling behavior based on the transitory nature of the response suppression produced and he alerted his readers to the side effects of its use. Among these side effects were the dangers of conditioned punishment, an increase in escape and avoidance responses during punishment, the occurrence of punishment-induced aggression, and the development of countercontrol strategies.

Sidman’s (1989 / 2000 ) concerns are reasonable and highlight important aspects to be considered when using punishment. Despite his concerns and critiques, Sidman did not deny the relevance of punishment research and the need for a better understanding of punishment effects ( Holth, 2010 ). Accordingly, the goal of the present paper is to revisit Sidman’s arguments about the shortcomings and side effects of punishment and examine empirical data that corroborate or contradict these arguments. We hope that such a review improves our understanding of punishment and help to inform discussions about whether, when, and how punishment might be employed, and perhaps help to renew empirical and theoretical interest in punishment.

What is punishment and how does it work?

In Coercion and its fallout Sidman defines punishment as follows:

We define reinforcers, positive or negative, by their special effect on conduct; they increase the future likelihood of actions they follow. But we define punishment without appealing to any behavioral effect; punishment occurs whenever an action is followed either by a loss of positive or a gain of negative reinforcers. This definition says nothing about the effect of a punisher on the action that produces it. It says neither that punishment is the opposite of reinforcement nor that punishment reduces the future likelihood of punished actions. ( Sidman, 1989 / 2000 , p. 45)

This definition was first proposed by Thorndike (1932) and adopted by Skinner (1953) . According to this definition, reinforcement and punishment are assumed to be inherently different. Punishment refers to a procedure, while reinforcement is functionally defined, referring to both the procedure and a behavioral process (e.g., Holth, 2010 ; Sidman, 1993 , 2011 ).

Other underlying assumptions are included in this procedural definition of punishment. First, this definition assumes there is no symmetry between reinforcement and punishment, thus they affect behavior through different mechanisms (e.g., Carvalho Neto et al., 2017 ; Carvalho Neto & Mayer, 2011 ; Holth, 2005 ). Second, defining punishment as a procedure and not a process implies that punishment does not have a direct effect on behavior. Instead, the response suppression observed during punishment is assumed to result from other indirect processes, such as an increase in the frequency of other unpunished responses (i.e., escape and avoidance), or the occurrence of unconditioned emotional responses (e.g., freezing) that are incompatible with the punished response ( Hineline, 1984 ; Schuster & Rachlin, 1968 ). Thus, punishment is only effective in reducing behavior to the extent that it increases the frequency of competing unpunished responses ( Dinsmoor, 1954 ; 1955 ; Hineline, 1984 ; Solomon, 1964 ).

A different definition of punishment was proposed by Azrin and Holz (1966) , suggesting that punishment is a consequence (e.g., removal of an appetitive stimulus or presentation of an aversive stimulus) that reduces the probability of the behavior that produces it. This definition has been the most commonly used and accepted one (e.g., Hineline & Rosales-Ruiz, 2013 ; Holth, 2010 ; Lerman & Vorndran, 2002 ; Mallpress et al. 2012 ; see Sidman, 2006 for discussion). Here, punishment is defined functionally, similar to reinforcement, and punishment and reinforcement are considered symmetrical processes having similar effects on behavior, but in opposite directions ( Hake & Azrin, 1965 ). Furthermore, the Azrin and Holz (1966) definition does not attribute the effects of punishment to any observable or hypothesized competing response ( Carvalho Neto et al., 2017 ; Holth, 2005 ).