- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Presentations

How to Prepare a Paper Presentation

Last Updated: October 4, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Patrick Muñoz . Patrick is an internationally recognized Voice & Speech Coach, focusing on public speaking, vocal power, accent and dialects, accent reduction, voiceover, acting and speech therapy. He has worked with clients such as Penelope Cruz, Eva Longoria, and Roselyn Sanchez. He was voted LA's Favorite Voice and Dialect Coach by BACKSTAGE, is the voice and speech coach for Disney and Turner Classic Movies, and is a member of Voice and Speech Trainers Association. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 368,833 times.

A paper is bad enough, but presentations are even more nerve-wracking. You've got the writing down, but how do you turn it into a dynamic, informative, enjoyable presentation? Why, here's how!

Guidelines and Audience

- Know how long the speech must be.

- Know how many points you're required to cover.

- Know if you must include sources or visuals.

- If you're presenting to people you know, it'll be easy to know what to break down and what to gloss over. But if you're presenting to unknown stockholders or faculty, for instance, you need to know about them and their knowledge levels, too. You may have to break your paper down into its most basic concepts. Find out what you can about their backgrounds.

- Does the facility have a computer and projector screen?

- Is there a working WiFi connection?

- Is there a microphone? A podium?

- Is there someone who can assist you in working the equipment before your presentation?

Script and Visuals

- Only have one point per notecard -- that way you won't end up searching the notecard for your information. And don't forget to number the cards in case you get mixed up! And the points on your cards shouldn't match your paper; instead of regurgitating information, discuss why the key points of your paper are important or the different points of view on this topic within the field.

- As you go through this outline, remove any jargon if it may not be understood.

- If you won't have access to the proper technology, print visual aids on poster board or foam-core board.

- If using presentation software, use words sparingly, but enough to get your point across. Think in phrases (and pictures!), not sentences. Acronyms and abbreviations are okay on the screen, but when you talk, address them fully. And remember to use large fonts -- not everyone's vision is fantastic. [7] X Research source

- It's okay to be a bit repetitive. Emphasizing important ideas will enhance comprehension and recall. When you've gone full circle, cycle back to a previous point to lead your audience to the right conclusion.

- Minimize the unnecessary details (the procedure you had to go through, etc.) when highlighting the main ideas you want to relay. You don't want to overload your audience with fluff, forcing them to miss the important stuff.

- Show enthusiasm! A very boring topic can be made interesting if there is passion behind it.

Practice, Practice, and More Practice

- If you can grab a friend who you think has a similar knowledge level to your audience, all the better. They'll help you see what points are foggier to minds with less expertise on the topic.

- It'll also help you with volume. Some people get rather timid when in the spotlight. You may not be aware that you're not loud enough!

- Do the same with your conclusion. Thank everyone for their time and open the floor for any questions, if allowed.

- Make eye contact with people in the audience to help build your connection with them.

What Is The Best Way To Start a Presentation?

Community Q&A

- Most people get nervous while public speaking. [10] X Research source You are not alone. [11] X Trustworthy Source Mayo Clinic Educational website from one of the world's leading hospitals Go to source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 1

- Visual aids not only help the audience, but they can help jog your memory if you forget where you are in your presentation. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Rehearse in front of a mirror before your presentation. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Answer questions only if it is related to your presentation. Keep these to the end of your talk. Thanks Helpful 76 Not Helpful 14

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://theihs.org/blog/prepare-for-a-paper-presentation-at-an-academic-conference/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/conference-papers/

- ↑ https://www.ncsl.org/legislators-staff/legislative-staff/legislative-staff-coordinating-committee/tips-for-making-effective-powerpoint-presentations.aspx

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4qZMPW5g-v8

- ↑ https://twp.duke.edu/sites/twp.duke.edu/files/file-attachments/paper-to-talk.original.pdf

- ↑ http://www.cs.swarthmore.edu/~newhall/presentation.html

- ↑ https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgebradt/2014/09/10/big-presentation-dont-do-it-have-a-conversation-instead/#6d56a3f23c4b

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/smashing-the-brainblocks/201711/why-are-we-scared-public-speaking

- ↑ https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/specific-phobias/expert-answers/fear-of-public-speaking/faq-20058416

About This Article

To prepare a paper presentation, create an outline of your content, then write your script on note cards or slides using software like PowerPoint. Be sure to stick to one main point per card or slide! Next, design visual aids like graphics, charts, and bullet points to illustrate your content and help the audience follow along. Then, practice giving your presentation in front of friends and family until you feel ready to do it in class! For tips on creating an outline and organizing your information, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Vignesh Sanjeevi

Mar 8, 2016

Did this article help you?

Pulicheri Gunasri

Mahesh Prajapati

Sep 14, 2017

Geraldine Jean Michel

Oct 25, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

- Google Slides Presentation Design

- Pitch Deck Design

- Powerpoint Redesign

- Other Design Services

- Guide & How to's

- How to present a research paper in PPT: best practices

A research paper presentation is frequently used at conferences and other events where you have a chance to share the results of your research and receive feedback from colleagues. Although it may appear as simple as summarizing the findings, successful examples of research paper presentations show that there is a little bit more to it.

In this article, we’ll walk you through the basic outline and steps to create a good research paper presentation. We’ll also explain what to include and what not to include in your presentation of research paper and share some of the most effective tips you can use to take your slides to the next level.

Research paper PowerPoint presentation outline

Creating a PowerPoint presentation for a research paper involves organizing and summarizing your key findings, methodology, and conclusions in a way that encourages your audience to interact with your work and share their interest in it with others. Here’s a basic research paper outline PowerPoint you can follow:

1. Title (1 slide)

Typically, your title slide should contain the following information:

- Title of the research paper

- Affiliation or institution

- Date of presentation

2. Introduction (1-3 slides)

On this slide of your presentation, briefly introduce the research topic and its significance and state the research question or objective.

3. Research questions or hypothesis (1 slide)

This slide should emphasize the objectives of your research or present the hypothesis.

4. Literature review (1 slide)

Your literature review has to provide context for your research by summarizing relevant literature. Additionally, it should highlight gaps or areas where your research contributes.

5. Methodology and data collection (1-2 slides)

This slide of your research paper PowerPoint has to explain the research design, methods, and procedures. It must also Include details about participants, materials, and data collection and emphasize special equipment you have used in your work.

6. Results (3-5 slides)

On this slide, you must present the results of your data analysis and discuss any trends, patterns, or significant findings. Moreover, you should use charts, graphs, and tables to illustrate data and highlight something novel in your results (if applicable).

7. Conclusion (1 slide)

Your conclusion slide has to summarize the main findings and their implications, as well as discuss the broader impact of your research. Usually, a single statement is enough.

8. Recommendations (1 slide)

If applicable, provide recommendations for future research or actions on this slide.

9. References (1-2 slides)

The references slide is where you list all the sources cited in your research paper.

10. Acknowledgments (1 slide)

On this presentation slide, acknowledge any individuals, organizations, or funding sources that contributed to your research.

11. Appendix (1 slide)

If applicable, include any supplementary materials, such as additional data or detailed charts, in your appendix slide.

The above outline is just a general guideline, so make sure to adjust it based on your specific research paper and the time allotted for the presentation.

Steps to creating a memorable research paper presentation

Creating a PowerPoint presentation for a research paper involves several critical steps needed to convey your findings and engage your audience effectively, and these steps are as follows:

Step 1. Understand your audience:

- Identify the audience for your presentation.

- Tailor your content and level of detail to match the audience’s background and knowledge.

Step 2. Define your key messages:

- Clearly articulate the main messages or findings of your research.

- Identify the key points you want your audience to remember.

Step 3. Design your research paper PPT presentation:

- Use a clean and professional design that complements your research topic.

- Choose readable fonts, consistent formatting, and a limited color palette.

- Opt for PowerPoint presentation services if slide design is not your strong side.

Step 4. Put content on slides:

- Follow the outline above to structure your presentation effectively; include key sections and topics.

- Organize your content logically, following the flow of your research paper.

Step 5. Final check:

- Proofread your slides for typos, errors, and inconsistencies.

- Ensure all visuals are clear, high-quality, and properly labeled.

Step 6. Save and share:

- Save your presentation and ensure compatibility with the equipment you’ll be using.

- If necessary, share a copy of your presentation with the audience.

By following these steps, you can create a well-organized and visually appealing research paper presentation PowerPoint that effectively conveys your research findings to the audience.

What to include and what not to include in your presentation

In addition to the must-know PowerPoint presentation recommendations, which we’ll cover later in this article, consider the following do’s and don’ts when you’re putting together your research paper presentation:

- Focus on the topic.

- Be brief and to the point.

- Attract the audience’s attention and highlight interesting details.

- Use only relevant visuals (maps, charts, pictures, graphs, etc.).

- Use numbers and bullet points to structure the content.

- Make clear statements regarding the essence and results of your research.

Don’ts:

- Don’t write down the whole outline of your paper and nothing else.

- Don’t put long, full sentences on your slides; split them into smaller ones.

- Don’t use distracting patterns, colors, pictures, and other visuals on your slides; the simpler, the better.

- Don’t use too complicated graphs or charts; only the ones that are easy to understand.

- Now that we’ve discussed the basics, let’s move on to the top tips for making a powerful presentation of your research paper.

8 tips on how to make research paper presentation that achieves its goals

You’ve probably been to a presentation where the presenter reads word for word from their PowerPoint outline. Or where the presentation is cluttered, chaotic, or contains too much data. The simple tips below will help you summarize a 10 to 15-page paper for a 15 to 20-minute talk and succeed, so read on!

Tip #1: Less is more

You want to provide enough information to make your audience want to know more. Including details but not too many and avoiding technical jargon, formulas, and long sentences are always good ways to achieve this.

Tip #2: Be professional

Avoid using too many colors, font changes, distracting backgrounds, animations, etc. Bullet points with a few words to highlight the important information are preferable to lengthy paragraphs. Additionally, include slide numbers on all PowerPoint slides except for the title slide, and make sure it is followed by a table of contents, offering a brief overview of the entire research paper.

Tip #3: Strive for balance

PowerPoint slides have limited space, so use it carefully. Typically, one to two points per slide or 5 lines for 5 words in a sentence are enough to present your ideas.

Tip #4: Use proper fonts and text size

The font you use should be easy to read and consistent throughout the slides. You can go with Arial, Times New Roman, Calibri, or a combination of these three. An ideal text size is 32 points, while a heading size is 44.

Tip #5: Concentrate on the visual side

A PowerPoint presentation is one of the best tools for presenting information visually. Use graphs instead of tables and topic-relevant illustrations instead of walls of text. Keep your visuals as clean and professional as the content of your presentation.

Tip #6: Practice your delivery

Always go through your presentation when you’re done to ensure a smooth and confident delivery and time yourself to stay within the allotted limit.

Tip #7: Get ready for questions

Anticipate potential questions from your audience and prepare thoughtful responses. Also, be ready to engage in discussions about your research.

Tip #8: Don’t be afraid to utilize professional help

If the mere thought of designing a presentation overwhelms you or you’re pressed for time, consider leveraging professional PowerPoint redesign services . A dedicated design team can transform your content or old presentation into effective slides, ensuring your message is communicated clearly and captivates your audience. This way, you can focus on refining your delivery and preparing for the presentation.

Lastly, remember that even experienced presenters get nervous before delivering research paper PowerPoint presentations in front of the audience. You cannot know everything; some things can be beyond your control, which is completely fine. You are at the event not only to share what you know but also to learn from others. So, no matter what, dress appropriately, look straight into the audience’s eyes, try to speak and move naturally, present your information enthusiastically, and have fun!

If you need help with slide design, get in touch with our dedicated design team and let qualified professionals turn your research findings into a visually appealing, polished presentation that leaves a lasting impression on your audience. Our experienced designers specialize in creating engaging layouts, incorporating compelling graphics, and ensuring a cohesive visual narrative that complements content on any subject.

#ezw_tco-2 .ez-toc-widget-container ul.ez-toc-list li.active::before { background-color: #ededed; } Table of contents

- Presenting techniques

- 50 tips on how to improve PowerPoint presentations in 2022-2023 [Updated]

- Present financial information visually in PowerPoint to drive results

- Keynote VS PowerPoint

- Design Tips

8 rules of effective presentation

- Business Slides

Employee training and onboarding presentation: why and how

How to structure, design, write, and finally present executive summary presentation?

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

- Presenting the Research Paper

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Writing the Research Paper

Writing an Abstract

Oral presentation, compiling a powerpoint.

Abstract : a short statement that describes a longer work.

- Indicate the subject.

- Describe the purpose of the investigation.

- Briefly discuss the method used.

- Make a statement about the result.

Oral presentations usually introduce a discussion of a topic or research paper. A good oral presentation is focused, concise, and interesting in order to trigger a discussion.

- Be well prepared; write a detailed outline.

- Introduce the subject.

- Talk about the sources and the method.

- Indicate if there are conflicting views about the subject (conflicting views trigger discussion).

- Make a statement about your new results (if this is your research paper).

- Use visual aids or handouts if appropriate.

An effective PowerPoint presentation is just an aid to the presentation, not the presentation itself .

- Be brief and concise.

- Focus on the subject.

- Attract attention; indicate interesting details.

- If possible, use relevant visual illustrations (pictures, maps, charts graphs, etc.).

- Use bullet points or numbers to structure the text.

- Make clear statements about the essence/results of the topic/research.

- Don't write down the whole outline of your paper and nothing else.

- Don't write long full sentences on the slides.

- Don't use distracting colors, patterns, pictures, decorations on the slides.

- Don't use too complicated charts, graphs; only those that are relatively easy to understand.

- << Previous: Writing the Research Paper

- Last Updated: Aug 22, 2024 3:43 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

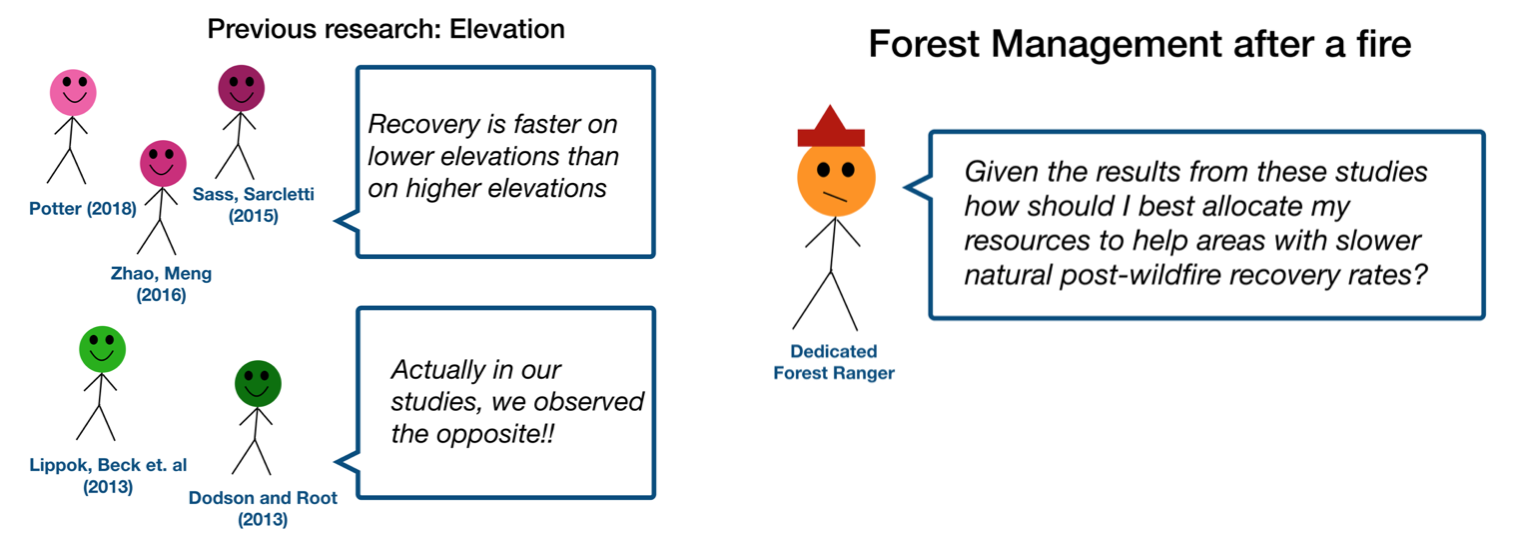

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

- 4 minute read

- 141.4K views

Table of Contents

A research paper presentation is often used at conferences and in other settings where you have an opportunity to share your research, and get feedback from your colleagues. Although it may seem as simple as summarizing your research and sharing your knowledge, successful research paper PowerPoint presentation examples show us that there’s a little bit more than that involved.

In this article, we’ll highlight how to make a PowerPoint presentation from a research paper, and what to include (as well as what NOT to include). We’ll also touch on how to present a research paper at a conference.

Purpose of a Research Paper Presentation

The purpose of presenting your paper at a conference or forum is different from the purpose of conducting your research and writing up your paper. In this setting, you want to highlight your work instead of including every detail of your research. Likewise, a presentation is an excellent opportunity to get direct feedback from your colleagues in the field. But, perhaps the main reason for presenting your research is to spark interest in your work, and entice the audience to read your research paper.

So, yes, your presentation should summarize your work, but it needs to do so in a way that encourages your audience to seek out your work, and share their interest in your work with others. It’s not enough just to present your research dryly, to get information out there. More important is to encourage engagement with you, your research, and your work.

Tips for Creating Your Research Paper Presentation

In addition to basic PowerPoint presentation recommendations, which we’ll cover later in this article, think about the following when you’re putting together your research paper presentation:

- Know your audience : First and foremost, who are you presenting to? Students? Experts in your field? Potential funders? Non-experts? The truth is that your audience will probably have a bit of a mix of all of the above. So, make sure you keep that in mind as you prepare your presentation.

Know more about: Discover the Target Audience .

- Your audience is human : In other words, they may be tired, they might be wondering why they’re there, and they will, at some point, be tuning out. So, take steps to help them stay interested in your presentation. You can do that by utilizing effective visuals, summarize your conclusions early, and keep your research easy to understand.

- Running outline : It’s not IF your audience will drift off, or get lost…it’s WHEN. Keep a running outline, either within the presentation or via a handout. Use visual and verbal clues to highlight where you are in the presentation.

- Where does your research fit in? You should know of work related to your research, but you don’t have to cite every example. In addition, keep references in your presentation to the end, or in the handout. Your audience is there to hear about your work.

- Plan B : Anticipate possible questions for your presentation, and prepare slides that answer those specific questions in more detail, but have them at the END of your presentation. You can then jump to them, IF needed.

What Makes a PowerPoint Presentation Effective?

You’ve probably attended a presentation where the presenter reads off of their PowerPoint outline, word for word. Or where the presentation is busy, disorganized, or includes too much information. Here are some simple tips for creating an effective PowerPoint Presentation.

- Less is more: You want to give enough information to make your audience want to read your paper. So include details, but not too many, and avoid too many formulas and technical jargon.

- Clean and professional : Avoid excessive colors, distracting backgrounds, font changes, animations, and too many words. Instead of whole paragraphs, bullet points with just a few words to summarize and highlight are best.

- Know your real-estate : Each slide has a limited amount of space. Use it wisely. Typically one, no more than two points per slide. Balance each slide visually. Utilize illustrations when needed; not extraneously.

- Keep things visual : Remember, a PowerPoint presentation is a powerful tool to present things visually. Use visual graphs over tables and scientific illustrations over long text. Keep your visuals clean and professional, just like any text you include in your presentation.

Know more about our Scientific Illustrations Services .

Another key to an effective presentation is to practice, practice, and then practice some more. When you’re done with your PowerPoint, go through it with friends and colleagues to see if you need to add (or delete excessive) information. Double and triple check for typos and errors. Know the presentation inside and out, so when you’re in front of your audience, you’ll feel confident and comfortable.

How to Present a Research Paper

If your PowerPoint presentation is solid, and you’ve practiced your presentation, that’s half the battle. Follow the basic advice to keep your audience engaged and interested by making eye contact, encouraging questions, and presenting your information with enthusiasm.

We encourage you to read our articles on how to present a scientific journal article and tips on giving good scientific presentations .

Language Editing Plus

Improve the flow and writing of your research paper with Language Editing Plus. This service includes unlimited editing, manuscript formatting for the journal of your choice, reference check and even a customized cover letter. Learn more here , and get started today!

Know How to Structure Your PhD Thesis

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

You may also like.

What is a Good H-index?

What is a Corresponding Author?

How to Submit a Paper for Publication in a Journal

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.17(12); 2021 Dec

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

Kristen m. naegle.

Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway

It is very difficult to stay focused on a presentation, especially if it is long or if it is part of a longer series of talks at a conference. Audience members may get distracted by an important email, or they may start dreaming of lunch. So, it’s important to look at your slide and ask “If they heard nothing I said, will they understand the key concept of this slide?” The other rules are set up to help with this, including clarity of the single point of the slide (Rule 1), titling it with a major conclusion (Rule 3), and the use of figures (Rule 6) and short text redundant to your verbal description (Rule 7). However, with each slide, step back and ask whether its main conclusion is conveyed, even if someone didn’t hear your accompanying dialog. Importantly, ask if the information on the slide is at the right level of abstraction. For example, do you have too many details about the experiment, which hides the conclusion of the experiment (i.e., breaking Rule 1)? If you are worried about not having enough details, keep a slide at the end of your slide deck (after your conclusions and acknowledgments) with the more detailed information that you can refer to during a question and answer period.

Rule 9: Iteratively improve slide design through practice

Well-designed slides that follow the first 8 rules are intended to help you deliver the message you intend and in the amount of time you intend to deliver it in. The best way to ensure that you nailed slide design for your presentation is to practice, typically a lot. The most important aspects of practicing a new presentation, with an eye toward slide design, are the following 2 key points: (1) practice to ensure that you hit, each time through, the most important points (for example, the text guide posts you left yourself and the title of the slide); and (2) practice to ensure that as you conclude the end of one slide, it leads directly to the next slide. Slide transitions, what you say as you end one slide and begin the next, are important to keeping the flow of the “story.” Practice is when I discover that the order of my presentation is poor or that I left myself too few guideposts to remember what was coming next. Additionally, during practice, the most frequent things I have to improve relate to Rule 2 (the slide takes too long to present, usually because I broke Rule 1, and I’m delivering too much information for one slide), Rule 4 (I have a nonessential detail on the slide), and Rule 5 (I forgot to give a key reference). The very best type of practice is in front of an audience (for example, your lab or peers), where, with fresh perspectives, they can help you identify places for improving slide content, design, and connections across the entirety of your talk.

Rule 10: Design to mitigate the impact of technical disasters

The real presentation almost never goes as we planned in our heads or during our practice. Maybe the speaker before you went over time and now you need to adjust. Maybe the computer the organizer is having you use won’t show your video. Maybe your internet is poor on the day you are giving a virtual presentation at a conference. Technical problems are routinely part of the practice of sharing your work through presentations. Hence, you can design your slides to limit the impact certain kinds of technical disasters create and also prepare alternate approaches. Here are just a few examples of the preparation you can do that will take you a long way toward avoiding a complete fiasco:

- Save your presentation as a PDF—if the version of Keynote or PowerPoint on a host computer cause issues, you still have a functional copy that has a higher guarantee of compatibility.

- In using videos, create a backup slide with screen shots of key results. For example, if I have a video of cell migration, I’ll be sure to have a copy of the start and end of the video, in case the video doesn’t play. Even if the video worked, you can pause on this backup slide and take the time to highlight the key results in words if someone could not see or understand the video.

- Avoid animations, such as figures or text that flash/fly-in/etc. Surveys suggest that no one likes movement in presentations [ 3 , 4 ]. There is likely a cognitive underpinning to the almost universal distaste of pointless animations that relates to the idea proposed by Kosslyn and colleagues that animations are salient perceptual units that captures direct attention [ 4 ]. Although perceptual salience can be used to draw attention to and improve retention of specific points, if you use this approach for unnecessary/unimportant things (like animation of your bullet point text, fly-ins of figures, etc.), then you will distract your audience from the important content. Finally, animations cause additional processing burdens for people with visual impairments [ 10 ] and create opportunities for technical disasters if the software on the host system is not compatible with your planned animation.

Conclusions

These rules are just a start in creating more engaging presentations that increase audience retention of your material. However, there are wonderful resources on continuing on the journey of becoming an amazing public speaker, which includes understanding the psychology and neuroscience behind human perception and learning. For example, as highlighted in Rule 7, David JP Phillips has a wonderful TEDx talk on the subject [ 5 ], and “PowerPoint presentation flaws and failures: A psychological analysis,” by Kosslyn and colleagues is deeply detailed about a number of aspects of human cognition and presentation style [ 4 ]. There are many books on the topic, including the popular “Presentation Zen” by Garr Reynolds [ 11 ]. Finally, although briefly touched on here, the visualization of data is an entire topic of its own that is worth perfecting for both written and oral presentations of work, with fantastic resources like Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” [ 12 ] or the article “Visualization of Biomedical Data” by O’Donoghue and colleagues [ 13 ].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the countless presenters, colleagues, students, and mentors from which I have learned a great deal from on effective presentations. Also, a thank you to the wonderful resources published by organizations on how to increase inclusivity. A special thanks to Dr. Jason Papin and Dr. Michael Guertin on early feedback of this editorial.

Funding Statement

The author received no specific funding for this work.

How to Give a Good Academic Paper Presentation

- Post author By Maria Angel Ferrero

- Post date August 17, 2020

- No Comments on How to Give a Good Academic Paper Presentation

The art of pitching your academic research

So, you’re about to present your first academic paper? You are preparing to defend your thesis? You are about to present your research to a bunch of experts?

But, you don’t know where to start? or, how to start?

That’s ok, you are in the right place.

In this short post, I’m going to show you how to do a good academic research presentation so that your audience actually understands and appreciates it.

The main goal of an academic research presentation — like any other type of presentation — is to carry your audience through a story and grab their attention during the whole story. But no matter how good a story is, if it’s not told properly it’ll lose its audience at the very first words.

And every good story needs a good structure, otherwise, your audience will get lost in a dead-end.

To avoid getting into that dead-end and losing your audience, you should structure your presentation around 5 main questions:

- Who are you and what’s your story about?

- Why should your audience — or anyone — care about your story, and why is it relevant to tell that story now?

- How did you get to write your story? Who are the main characters?

- What happens in the story? What happens to the characters?

- So, What? Why this ending is better? Why should I wait for a new episode?

The order in which these questions are answered throughout your presentation can vary. Good stories might also start at the end and crawl back to its beginnings. Play with the order and see what suits best your story, only you know better what works for your research.

So let’s go now through each of the questions, shall we?

Who are you and what’s your research about?

Introduce yourself — unless you have already been introduced. Sometimes we are so impatience to give our presentation that we forget the basics.

Many times when we choose a book to read we ask ourselves about the human that wrote the book. And, as any writer researchers should include a short biography of themselves in the presentation.

And this is not to brag about yourself or your experience, but to give a human touch to the research itself. Before anyone wants to hear your story — your research — you need to tell them why they should be listening to you.

A short introduction of 30 seconds will do, your name, your background, why you are here in this room presenting and anything else that might be relevant to the research you are doing.

Give a context to your story, a kind of foreword to your research. State your thesis clearly and tell your audience why the topic you are going to address is relevant. And why they should care.

Give a hook. Start with a kind of provocation to instill curiosity and need. Try to think out of the box and talk about something your audience will found interesting. Use analogies too much known or simpler things that everyone in the room would be able to understand. Don’t talk to the experts, they already know it.

To give you an example, this is how I started one of my papers on overconfidence and innovation:

If you had to choose between The Joker and Batman, who would you want to be?

My paper was nothing to do with superheroes — at least not in a common way — but I wanted to talk about the dual personality innovators have, thus The Joker vs Batman analogy.

Once you have given your hook and presented yourself, give your audience an idea of what you are going to talk about and what awaits them during the following minutes.

Give them a roadmap of the talk, even if it seems redundant to you. This doesn’t mean you have to list your table of contents, just a prelude of your story.

In total, one minute and one slide are enough.

Why should your audience care about your Research, and why is it relevant now?

The next 2 or 3 slides should introduce the subject to the audience. Very briefly. Usually, research presentations last between 10 to 15 minutes, but many are shifting to the startup pitch format of 3 to 5 minutes. So being concise and direct to point is quite important.

Telling your audience why the topic you are researching about is important and relevant it’s essential, but should not take all time. This is just the introduction, you need to save time for the main story.

There are mainly 6 elements that make a good introduction:

- Define the Problem: Many speakers forget this simple point. No matter how difficult and technical the problem you are addressing is there is certainly a way to explain it concisely and clearly in less than one minute. Explain your problem as if your audience were 5 years old children, not because they are not smart or respectable, but because the simpler you get to explain a complex problem the more it shows your mastery and preparation. If the audience doesn’t understand the problem being attacked, then they won’t understand the rest of your talk, and you’ll lose them before you get to your great solution. For your slides, condense the problem into a very few carefully chosen words. An example here again from my research: Is being extremely confident in ourselves good or bad for innovation?

- Motivate the Audience: Explain why the problem is so important. How does the problem fit into the larger picture(e.g. entrepreneurship ecosystem, neuroscience,…)? What are its applications? What makes the problem nontrivial? If no one has done this research, why is it relevant now to do it? What are the circumstances that make it relevant now more than ever? Avoid broad statements such as “Innovation is what drives economic growth, but there are few innovative individuals, so how can we encourage people to become innovators?” Rather, focus on what really matters: “ universities are investing millions to develop entrepreneurship education program, still students graduating from these programs aren’t starting any venture.”

- Introduce Terminology: scientific jargon is boring and complex, it should be kept to a minimum. However, sometimes is almost impossible not to refer to specific scientific terms. Any complex jargon should be introduced at the beginning of the presentation or when each term is introduced for the first time during the presentation. To avoid losing time tot his, you can prepare a short document with all the terms and definitions to hand out to the participants in the audience.

- Discuss Earlier Work: Do your research, you are not reinventing the wheel. There is nothing more frustrating than listening to a talk that covers something that has already been published without making reference tot hose studies. It not only shows that you didn’t do your research and that you are underprepared, but it shows you don’t know how to conduct research. This doesn’t mean that you should have read and cited ALL the works and papers that talk about the topic of your research. This is only useful if you are doing a systematic review. But you have to be sure that you know, read and cite those that really matter. You have to explain why this work is different from past wor, or how you are improving or continuing the research.

- Emphasize the Contributions of the Paper: Make sure that you explicitly and succinctly state the contributions made by your paper. That is the so what?. Give just a quick glimpse of your contributions and implications for the research and the practice. The audience wants to know this. Often it is the only thing that they carry away from the talk.

- Consider putting your Conclusion in the Introduction : Be bold. Let everyone know from the start where you are headed so that the audience can focus on what matters.

How did you get to your results? How did you conduct your study?

There should be 1 or 2 methods slides that allow the audience to understand how the research was conducted. You might include a flow chart describing the main ingredients of the methods used. Do not put too many details, just what it’s needed to understand the study. Many of the details are appropriate for the manuscript but not for the presentation. If the audience wants to have more details on the methods they can always read your full paper, or you can prepare backup slides with this information to share during the Q&As session. For example, you could just say: “During 4 weeks we conducted semi-structured interviews with top managers and employees from different organizations. Our final sample was composed of 30 individuals, from which 10 were top managers and 15 were female and aged between 25 and 60 years.” Further details are presented in backup slides or in the manuscript.

What did you find, what happened?

The next 3 slides should show the main results obtained with your research. If appropriate, it is nice to start with a slide showing the basic phenomena being studied (e.G. the process of innovation and how). It reminds your audience about the variables used and manipulated and the role they have in the situation being studied.

Next, show figures, pictures, or graphs that clearly illustrate the main results. Do not show charts and tables of raw data. No one is able to read an excel table on a presentation, if only it gives the creeps. So instead of putting large and ugly tables, no one is going to read, use beautiful and meaningful graphs and figures.

You can use free infographic apps to build awesome visual representations of your data. Apps like Canva , Venngage , or Piktochart work great.

All figures should be clearly labeled. When showing figures, be sure to explain the figure axes before you talk about the data (e.g., “the X-axis shows time. The Y-axis shows economic profit).

When presenting the data try to be as simple as possible, this is the most complex part of your research. You might be an expert, but your audience probably is not and they need to understand your results if you want to convenience them with your research.

So, What? What are the outcomes, implications and future steps?

The last 2 slides are probably the most important section of your presentation. It’s the denouement of your story, and it should be good.

Nothing is more frustrating than reading or listening to a good story to arrive to a disappointing end. All the effort you did to tell the good story is lost if you don’t curate appropriately the ending.

Some people be distracted during the whole presentation and would only pay attention to your conclusions, so those conclusions better are good.

Before getting to your end, sum up what your study was about, your research questions and objectives, and then go to the conclusion. In this way, the lousy distracted audience will also get most of your research.

List the conclusions in clear, easy to understand language. You can read them to the audience. Also give one or two sentences about what this likely means — your interpretation — for the big picture, go back to the context and motives of your research. Explain how your results improve our understanding and contribute to theory and practice.

Don’t be afraid to talk about the flaws and limitations of your study. Not only this shows you are humble but that you are prepared enough and that you are aware that things can be improved. Remember that having contradictory results to what you expected is not a bad thing, they are still results, you need to find an explanation to this.

Once you know your limitations, tell your audience how can this be improved in future research. How can other scholars address the problems and flaws, what are the next steps, and what future research should focus on?

Your job as a presenter is to not only present the paper but also lead a discussion with your audience about your research. Talk about its strengths, weaknesses, and broader implications. To help focus the class discussion, end your presentation with a list of approximately three major questions/issues worthy of further discussion.

Please finalize your presentation with at least two or three major things that should be discussed. Discussion with the audience should be especially encouraged at this point, but you should be prepared to foster this by raising these issues.

So, when preparing your presentation think like one of the people in your audience. Think about what they would ask? What would they like to discuss further? What are the points that might trigger confusion or disagreement?

If you have these questions in mind you can prepare to give appropriate answers and be less stressed out by the uncertainty of your audience reaction. You can then prepare a couple of backup slides that will help you give responses to the questions being asked and that will help you make your point.

Final thoughts

Reading and understanding academic research papers can be a tough assignment, especially because it can be very specific and you might not know or understand many terms, methodologies, or even statistical models and analysis. So preparing a presentation of an academic paper, whether is yours or others’ work, takes time and must be taken seriously.

When you are preparing your draft for the presentation, keep in mind that your audience will rely on listening comprehension, not reading comprehension. That means that your ideas need to be clear and to the point, and organized in a way that makes it possible for your audience to follow you.

And since understanding was difficult for you who had the time to read and discuss the paper with your team, you can imagine how difficult it might be for an audience that hasn’t read the paper and moreover has no expertise (or not much) on the research topic you are presenting.

So you have to be very careful about how you present your article so that your audience understands what you are saying, feel involved and curious, and off course don’t sleep while you talk.

Scientific oral presentations are not simply readings of scientific manuscripts, so being in front of an audience reading scientific terms and statistical models and equations is out of the picture. You need to provoke curiosity and engagement so that at the end of your presentation people want to know more about your research.

Don’t forget that time is precious, and not everyone is ready to give their time to listen to things they don’t find amusing or intriguing. Being concise and simple is not an easy exercise, but is crucial for passing by a message.

Follow simple presentation rules:

- 1 slide takes 1 minute to present, so if you have 10 minutes to present don’t do more than 10 slides.

- Don’t use small size fonts, the minimum readable size is 20pt.

- Don’t use text when you don’t need it, the text should be only be used to highlight things that you want your audience to remember

- Use pictures whenever you can but don’t overuse them. Pictures have to be relevant to your speech.

- Be careful with grammar and errors. Read your slides thoroughly a couple of times before submitting them for a presentation. And ask someone else to read them also, they are more likely to find mistakes than you are as they are less biased and less attached to your topic.

- Finally, prepare, prepare, and prepare. Mastery is only possible through training. No matter how good you are at improvising, preparing for a presentation is key for succeeding at it.

And that’s it. Good luck!

- Tags Research , Research Paper , Science , Scientific Paper

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Presentations

How to Create a Powerful Research Presentation

Written by: Raja Mandal

Have you ever had to create a research presentation?

If yes, you know how difficult it is to prepare an effective presentation that perfectly explains your research.

Since it's a visual representation of your papers, a large chunk of its preparation goes into designing.

No one knows your research paper better than you. So, only you can create the presentation to communicate the core message perfectly.

We've developed a practical, step-by-step guide to help you prepare a stellar research presentation. Before we dive in, here's a reminder that you don't have to be an expert to make one. With Visme's presentation maker and rich selection of presentation templates , you can create memorable research presentations in a few minutes.

Table of Contents

What is a research presentation, purpose of a research presentation, how to prepare an effective research presentation, research presentation design best practices, research presentation faqs.

- A research presentation visually showcases systematic investigation findings and allows presenters to get feedback. It's commonly used in academic settings, such as Higher Degree Research students presenting their papers.

- The purpose of a research presentation is to explain the significance of your research, clearly state your findings and methodology, get valuable feedback and make the audience learn more about your work or read your research paper.

- To prepare an effective research presentation, decide on your presentation’s goal, know your audience, create an outline, limit the amount of text on your slides, and spend more time explaining your research than summarizing old work.

- Some research presentation design tips include using an attractive background, utilizing a variety of layouts, using colors wisely, using font hierarchy and including high-quality images.

- Visme can help you create all kinds of research, corporate and creative presentations. Browse thousands of presentation templates , import a PowerPoint , whip up a custom presentation design using our AI presentation maker or create a slide deck from scratch using our drag-and-drop presentation software .

A research presentation is a visual representation of an individual's or organization's systematic investigation of a subject. It helps the presenter obtain feedback on their proposed research. For example, educational establishments require Higher Degree Research (HDR) students to present their research papers in a research presentation.

The purpose of a research presentation is to share the findings with the world. When done well, it helps achieve significant levels of impact in front of groups of people. Delivering the research paper as a presentation also communicates the subject matter in powerful ways.

A beautifully designed research presentation should:

- Explain the significance of your research.

- Clearly state your findings and the method of analysis.

- Get valuable feedback from others in your community to strengthen your research.

- Make the audience learn more about your work or read your research paper.

Create a stunning presentation in less time

- Hundreds of premade slides available

- Add animation and interactivity to your slides

- Choose from various presentation options

Sign up. It’s free.

Most research presentations can be boring, especially if your data is not presented in an engaging way. You should prepare your presentation in a way that attracts and persuades your audience while drawing attention to the main points.

Follow the steps below to do that.

Decide on Your Presentation’s Purpose

Beginning the design process without deciding on the purpose of your presentation is like crawling in the dark without knowing the destination. You should first know the purpose of your presentation before creating it.

The purpose of a research presentation can be defending a dissertation, an academic job interview, a conference, asking for funding, and various others. The rest of the process will depend on the purpose of your presentation.

Look at these 25 different presentation examples to get inspiration and find the one that best fits your needs.

Know Your Audience

You probably wouldn't speak to your lecturer like you talk to your friends. Creating a presentation is the same—you need to tailor your presentation's design, tone and content to make it appropriate for your audience.

To do that, you need to establish who your audience is. Your audience could be:

- Scientists/scholars in your field

- Graduate and undergraduate students

- Community members

Your target audience might be a mix of all of the above. In that case, it's better to have something for everyone. Once you know who your target audience is, ask yourself the following questions:

- Why are they here?

- What do they expect from your presentations?

- Are they willing to participate?

- What will keep them engaged?

- What do you want them to do and what's their part in your presentation?

- How do they prefer to receive information?

The answers to these questions will help you know your audience better and prepare your research presentation accordingly. Once you define your target audience, use these five traits of a highly engaging presentation to capture your audience's attention.

Create a Research Presentation Outline

Before crafting your presentation, it's crucial to create a presentation outline . Your outline will act as your guide to put your information in order and ensure you touch on all your major points.

Like other forms of academic writing, research presentations can be divided into several parts to make them more effective.

A research outline will:

- Guide you as you prepare your presentation

- Enable you to organize your ideas

- Present your research in a logical format

- Show the relationships among slides in your presentation

- Construct an order overview of your presentation

- Group ideas into main points

Though there is no universal formula for a research presentation outline, here's an example of what the outline should look like:

- Introduction and purpose

- Background and context

- Data and methodology

- Descriptive data

- Quantitative and qualitative analysis

- Future Research

Pro Tip: If your presentation needs to go through several rounds of edits or approvals, such as in the outline stage, streamline the process using Visme’s workflows . Instead of sending files back and forth, you can simply assign tasks and set up reviews or approvals.

Learn more about presentation structure to keep your audience engaged. Watch the video below for a better understanding.

Limit the Amount of Text on Your Slides

One of the most important things people often overlook is the amount of text on their presentation slides . Since the audience will be listening and watching, putting up a slide with lots of words will make them focus on reading instead of listening. As a result, they'll miss out on any critical points you are making.

The simpler you make your slides, the more your audience will grasp the meaning and retain the critical information. Here are a few ways to limit the amount of text on your slides.

1. Use Only Crucial Text on the Slides

Without making your point clear immediately, you will struggle to keep your audience's attention. Too much text can make your slides look cluttered and overwhelm the audience. Cut out waffle words, limiting content to the essentials.

If you’re struggling with summarizing your content or articulating your idea succinctly, use Visme’s AI Writer to create or shorten text into concise bullet points.

To avoid cognitive overload, combine text and images . Add animated graphics , icons , characters and gestures to bring your research presentation to life and capture your audience's attention.

2. Split up the Content Onto Multiple Slides

We recommend using one piece of information on a single slide. If you're talking about two or more topics, divide the topics into different slides to make your slides easily digestible and less daunting. The less information on each slide, the more your audience is likely to read.

3. Put Key Message Into the Heading

Use the slide headings of your presentation as a summary message. Think about the one key point you want the audience to take from each slide. And make the header short and impactful. This will ensure that your audience gets the main points immediately.

For example, you may have a statistic you want to really get across to your audience. Include that number in your heading so that it's the first point your audience reads.

But what if that statistic changes? Having to manually go back and update the number throughout your research presentation can be time-consuming.

With Visme's Dynamic Fields feature , updating important information throughout your presentation is a breeze. Take advantage of Dynamic Fields to ensure your data and research information is always up to date and accurate.

4. Visualize Data Instead of Writing Them

When adding facts and figures to your research presentation, harness the power of data visualization . Add charts and graphs to take out most of the text. You can also animate your charts and transform your slide deck into an interactive presentation .

Text with visuals causes a faster and stronger reaction than words alone, making your presentation more memorable. However, your data visualization should be straightforward to help create a narrative that further builds connections between information.

Have a look at these data visualization examples for inspiration. And here's an infographic explaining data visualization best practices.

Visme comes with a wide variety of charts and graphs templates you can use in your presentation.

5. Use Presenter Notes

Visme's Presenter Studio comes with a presenter notes feature that can help you keep your slides succinct. Use it to pull out any additional text that the audience needs to understand the content.

View your notes for each slide in the left sidebar of the presentation software to help you stay focused and on message throughout your presentation.

Explain Your Research

Some people spend nearly all of the presentation going over the existing research and giving background information on the particular case. Since you're preparing a research presentation, use more slides to explain the research papers you directly contributed to. This is also helpful to do when creating a grant proposal .

Your audience is there to learn about your new and exciting research, not to hear a summary of old work. So, if you create 20 slides for the presentation, spend at least 15 slides explaining your research, findings, and the key takeaways or recommendations.

Use Visme’s collaboration tools to work on your research presentation together with your team. This will help you create a well-rounded presentation that includes all the necessary points, even those that you did not work on directly.

Learn more about how to give a good presentation . This will help you explain your research more effectively.