- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The History of Computing: A Very Short Introduction

Author webpage

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This book describes the central events, machines, and people in the history of computing, and traces how innovation has brought us from pebbles used for counting, to the modern age of the computer. It has a strong historiographical theme that offers a new perspective on how to understand the historical narratives we have constructed, and examines the unspoken assumptions that underpin them. It describes inventions, pioneers, milestone systems, and the context of their use. It starts with counting, and traces change through calculating aids, mechanical calculation, and automatic electronic computation, both digital and analogue. It shows how four threads—calculation, automatic computing, information management, and communications—converged to create the ‘information age’. It examines three master narratives in established histories that are used as aids to marshal otherwise unmanageable levels detail. The treatment is rooted in the principal episodes that make up canonical histories of computing.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 7 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 6 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 4 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| January 2023 | 2 |

| January 2023 | 1 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 1 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 1 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 2 |

| February 2023 | 5 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| February 2023 | 6 |

| February 2023 | 12 |

| March 2023 | 15 |

| March 2023 | 1 |

| March 2023 | 5 |

| March 2023 | 6 |

| March 2023 | 6 |

| March 2023 | 10 |

| March 2023 | 5 |

| March 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| April 2023 | 5 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 4 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 3 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| June 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| July 2023 | 6 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 8 |

| August 2023 | 3 |

| August 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 5 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 11 |

| August 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 8 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 4 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 4 |

| November 2023 | 3 |

| November 2023 | 2 |

| December 2023 | 6 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 1 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 4 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 5 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 3 |

| February 2024 | 3 |

| February 2024 | 5 |

| February 2024 | 6 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 4 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 4 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 4 |

| April 2024 | 6 |

| April 2024 | 6 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 4 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 2 |

| April 2024 | 3 |

| April 2024 | 4 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 2 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| May 2024 | 4 |

| May 2024 | 1 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 10 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 7 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 3 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 4 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

| July 2024 | 4 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 4 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

External resource

- In the OUP print catalogue

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

IEEE Account

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

- Corpus ID: 14354044

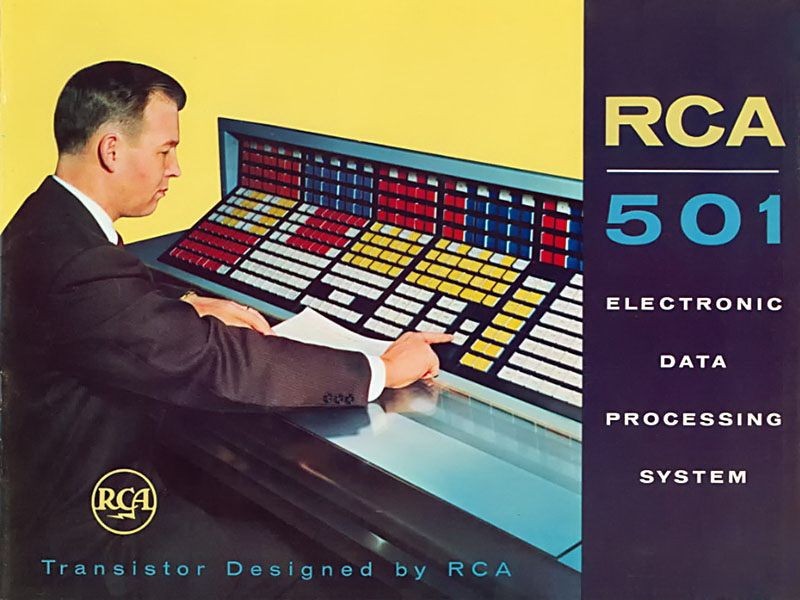

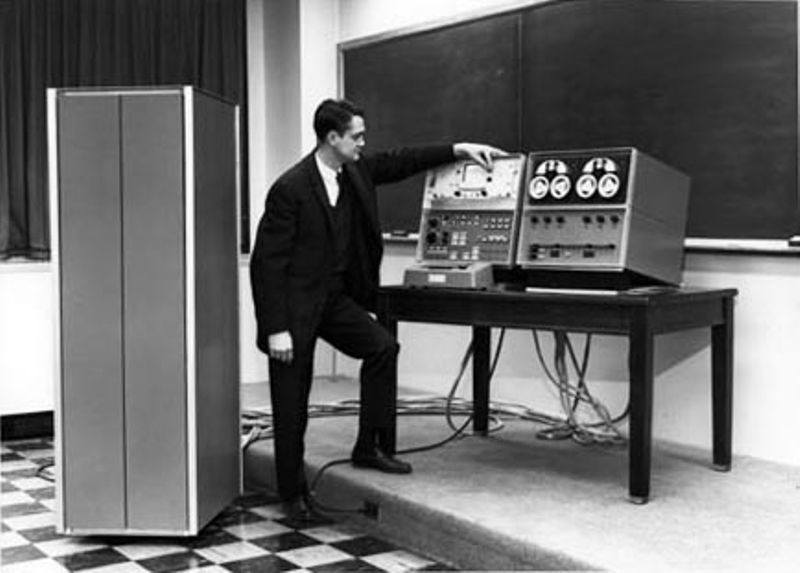

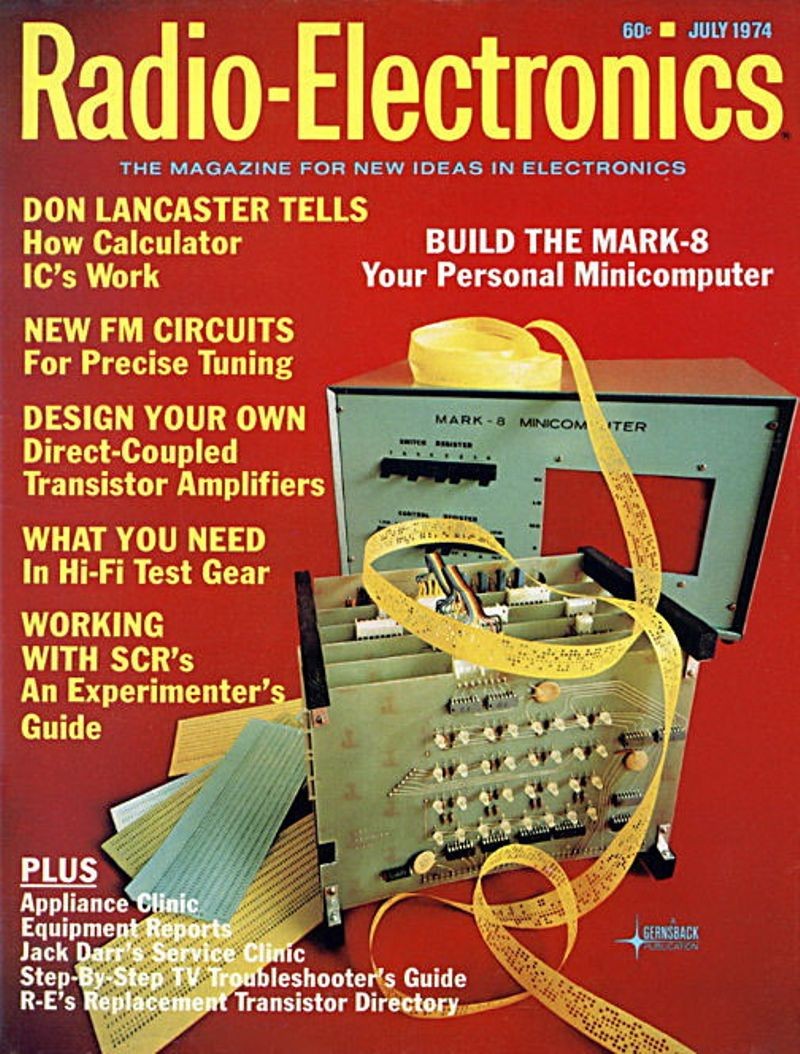

The History of Digital Computers

- Published 1974

- Computer Science, History

11 Citations

An annotated bibliography on the origins of digital computers.

- Highly Influenced

- 12 Excerpts

Sustainable Digital Environments: What Major Challenges Is Humankind Facing?

Digital applications in the energy sector-a review, honesty in history, introduction: automation, autonomy and artificial intelligence, the evolution of an x86 virtual machine monitor, studying history as it unfolds, part 1: creating the history of information technologies, review and categorization of digital applications in the energy sector, surgical robotics through a keyhole: from today's translational barriers to tomorrow's “disappearing” robots, digital energy management amid the covid-19 pandemic in mauritius, 2 references, rechnen mit maschinen : eine bildgeschichte der rechentechnik, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

The Evolution of Computers

Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communication and Information Processing (ICCIP)- 2023

9 Pages Posted: 9 Jan 2024

Sudarshan Kakad

Nutan college of engineering and research, vishnupuri, talegaon dabhade, pune – 410507, india., vaibhav kale, atharv kakare, aditya kalokhe, archana yewale.

Date Written: June 9, 2023

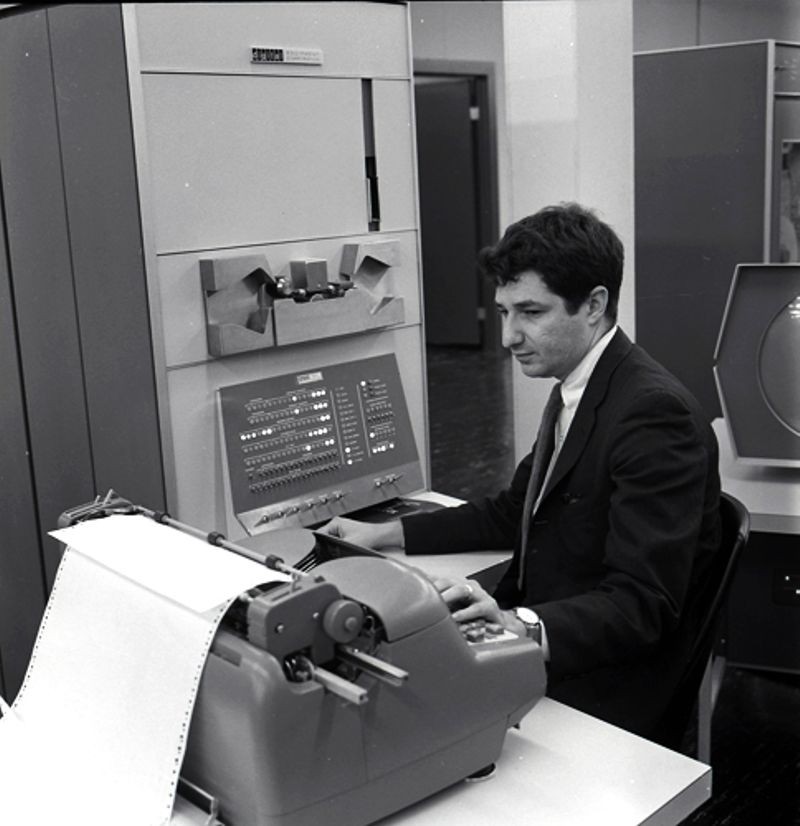

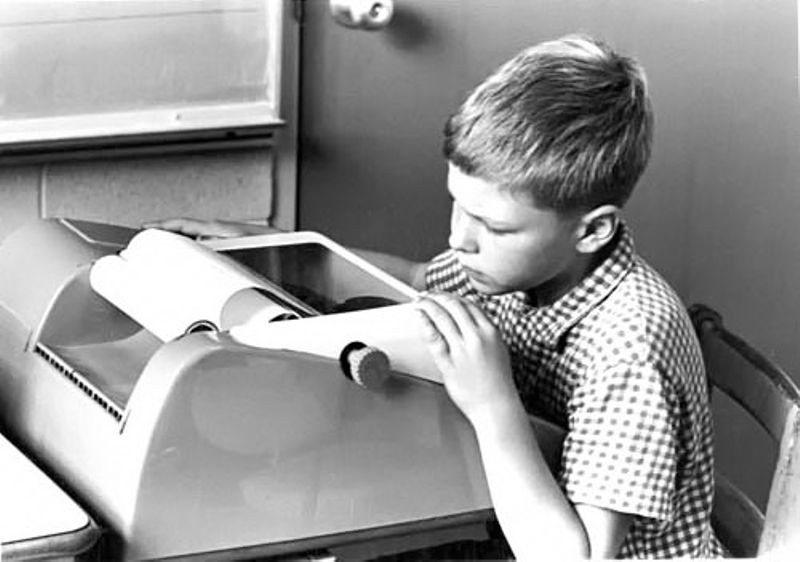

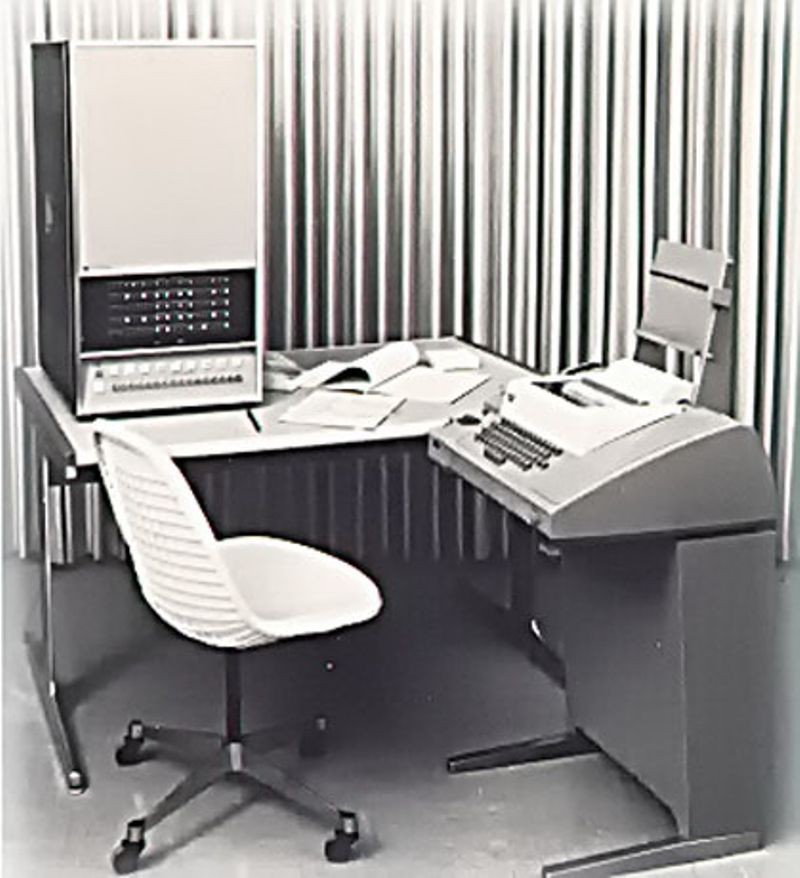

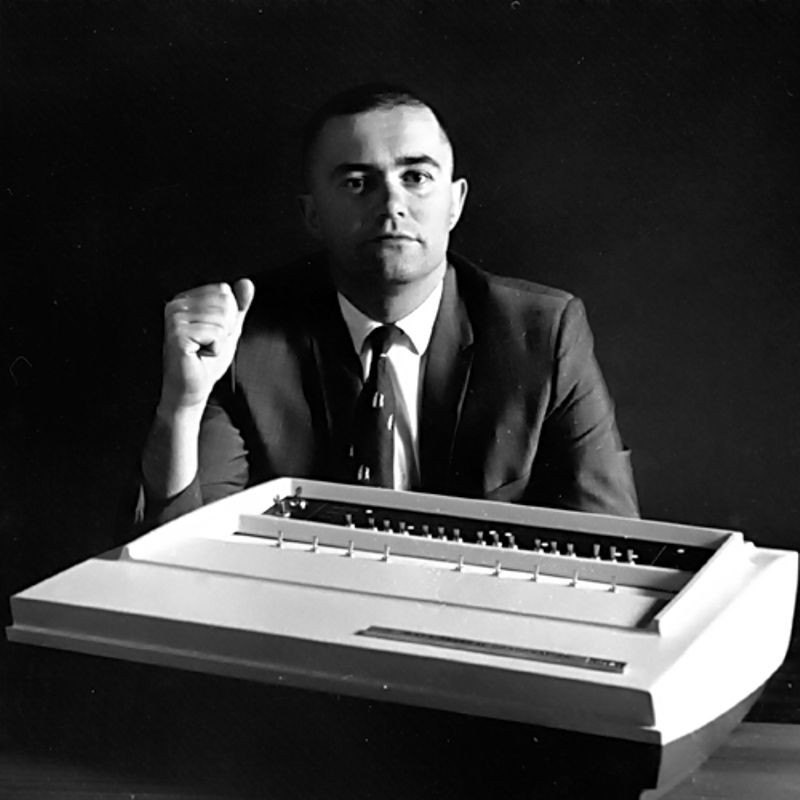

The evolution of computers has been one of the most transformative journeys in human history. This review paper provides a comprehensive examination of the development of computers from their early beginnings to the present day, shedding light on the major milestones, technological breakthroughs, and their profound implications on society. The paper commences with an exploration of the origins of computers, starting from the mechanical calculators of the 19th century to the emergence of early electronic computers in the mid-20th century. It highlights significant contributions by pioneers such as Charles Babbage, Alan Turing, and John von Neumann, who laid the foundations for the digital computing era. The subsequent sections focus on the revolutionary advancements that have shaped the evolution of computers. This includes the advent of transistors and integrated circuits, leading to the development of smaller, faster, and more powerful computers. The rise of personal computers in the 1970s and 1980s democratized computing, empowering individuals and businesses alike. The review also delves into the progression of computer architectures, the mainframe and minicomputer. Overall, this review paper provides a comprehensive overview of the evolution of computers, capturing the key milestones, technological advancements, and societal implications. It serves as a valuable resource for researchers, educators, and technology enthusiasts seeking to understand the transformative journey of computers.

Keywords: computers, evolution, history, inventions

JEL Classification: C0

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Archana Yewale (Contact Author)

Nutan college of engineering and research, vishnupuri, talegaon dabhade, pune – 410507, india. ( email ), do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on ssrn, paper statistics, related ejournals, information theory & research ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

History of Science & Environment eJournal

5th international conference on communication & information processing (iccip) 2023.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

History of computers: A brief timeline

The history of computers began with primitive designs in the early 19th century and went on to change the world during the 20th century.

- 2000-present day

Additional resources

The history of computers goes back over 200 years. At first theorized by mathematicians and entrepreneurs, during the 19th century mechanical calculating machines were designed and built to solve the increasingly complex number-crunching challenges. The advancement of technology enabled ever more-complex computers by the early 20th century, and computers became larger and more powerful.

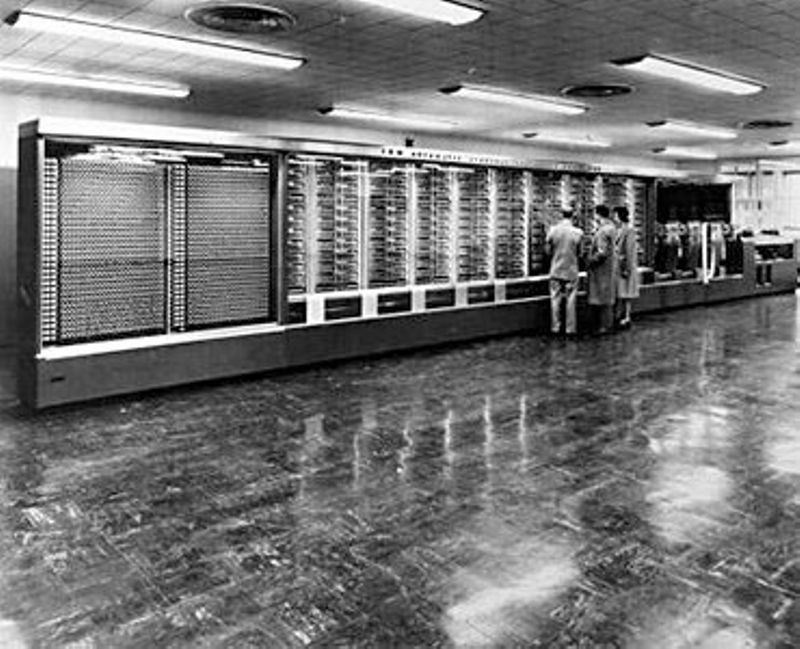

Today, computers are almost unrecognizable from designs of the 19th century, such as Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine — or even from the huge computers of the 20th century that occupied whole rooms, such as the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator.

Here's a brief history of computers, from their primitive number-crunching origins to the powerful modern-day machines that surf the Internet, run games and stream multimedia.

19th century

1801: Joseph Marie Jacquard, a French merchant and inventor invents a loom that uses punched wooden cards to automatically weave fabric designs. Early computers would use similar punch cards.

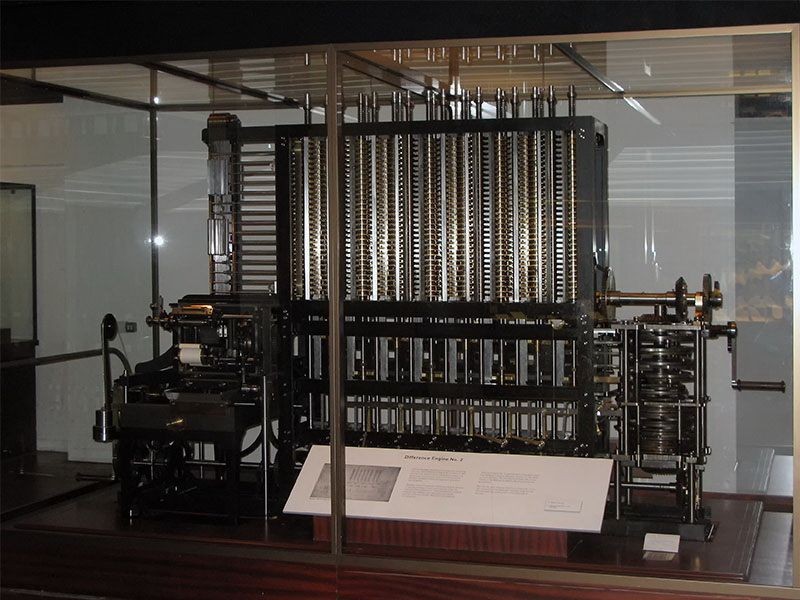

1821: English mathematician Charles Babbage conceives of a steam-driven calculating machine that would be able to compute tables of numbers. Funded by the British government, the project, called the "Difference Engine" fails due to the lack of technology at the time, according to the University of Minnesota .

1848: Ada Lovelace, an English mathematician and the daughter of poet Lord Byron, writes the world's first computer program. According to Anna Siffert, a professor of theoretical mathematics at the University of Münster in Germany, Lovelace writes the first program while translating a paper on Babbage's Analytical Engine from French into English. "She also provides her own comments on the text. Her annotations, simply called "notes," turn out to be three times as long as the actual transcript," Siffert wrote in an article for The Max Planck Society . "Lovelace also adds a step-by-step description for computation of Bernoulli numbers with Babbage's machine — basically an algorithm — which, in effect, makes her the world's first computer programmer." Bernoulli numbers are a sequence of rational numbers often used in computation.

1853: Swedish inventor Per Georg Scheutz and his son Edvard design the world's first printing calculator. The machine is significant for being the first to "compute tabular differences and print the results," according to Uta C. Merzbach's book, " Georg Scheutz and the First Printing Calculator " (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1977).

1890: Herman Hollerith designs a punch-card system to help calculate the 1890 U.S. Census. The machine, saves the government several years of calculations, and the U.S. taxpayer approximately $5 million, according to Columbia University Hollerith later establishes a company that will eventually become International Business Machines Corporation ( IBM ).

Early 20th century

1931: At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Vannevar Bush invents and builds the Differential Analyzer, the first large-scale automatic general-purpose mechanical analog computer, according to Stanford University .

1936: Alan Turing , a British scientist and mathematician, presents the principle of a universal machine, later called the Turing machine, in a paper called "On Computable Numbers…" according to Chris Bernhardt's book " Turing's Vision " (The MIT Press, 2017). Turing machines are capable of computing anything that is computable. The central concept of the modern computer is based on his ideas. Turing is later involved in the development of the Turing-Welchman Bombe, an electro-mechanical device designed to decipher Nazi codes during World War II, according to the UK's National Museum of Computing .

1937: John Vincent Atanasoff, a professor of physics and mathematics at Iowa State University, submits a grant proposal to build the first electric-only computer, without using gears, cams, belts or shafts.

1939: David Packard and Bill Hewlett found the Hewlett Packard Company in Palo Alto, California. The pair decide the name of their new company by the toss of a coin, and Hewlett-Packard's first headquarters are in Packard's garage, according to MIT .

1941: German inventor and engineer Konrad Zuse completes his Z3 machine, the world's earliest digital computer, according to Gerard O'Regan's book " A Brief History of Computing " (Springer, 2021). The machine was destroyed during a bombing raid on Berlin during World War II. Zuse fled the German capital after the defeat of Nazi Germany and later released the world's first commercial digital computer, the Z4, in 1950, according to O'Regan.

1941: Atanasoff and his graduate student, Clifford Berry, design the first digital electronic computer in the U.S., called the Atanasoff-Berry Computer (ABC). This marks the first time a computer is able to store information on its main memory, and is capable of performing one operation every 15 seconds, according to the book " Birthing the Computer " (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016)

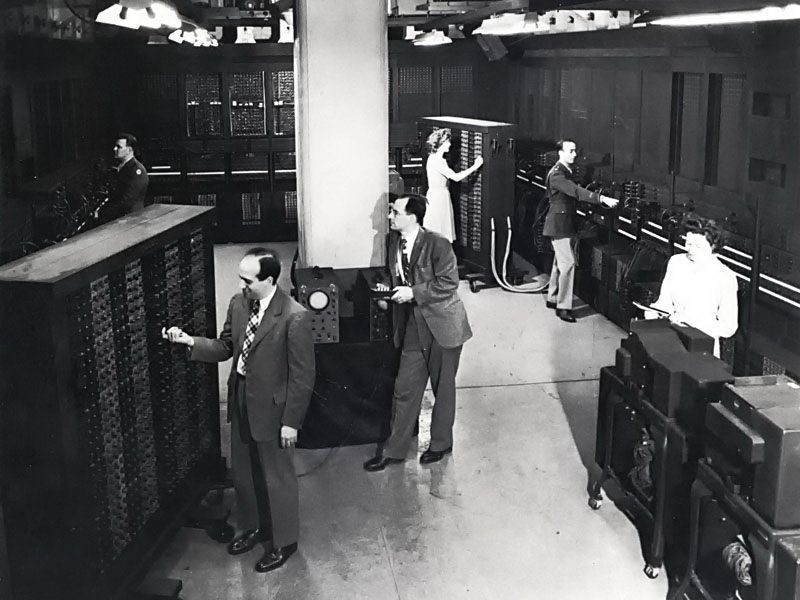

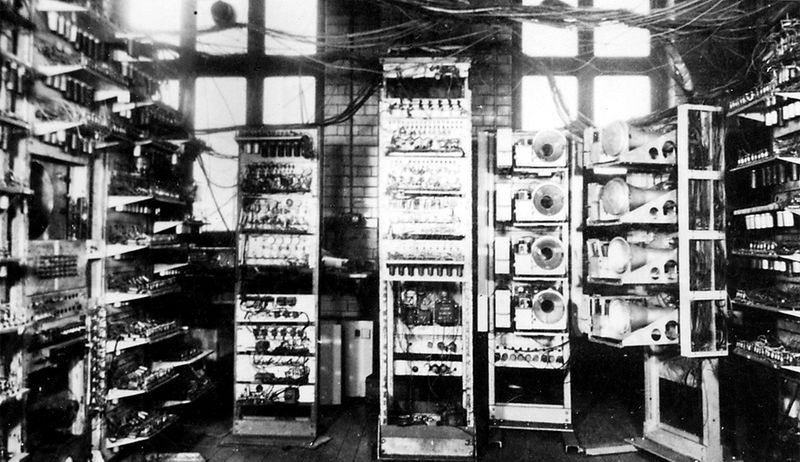

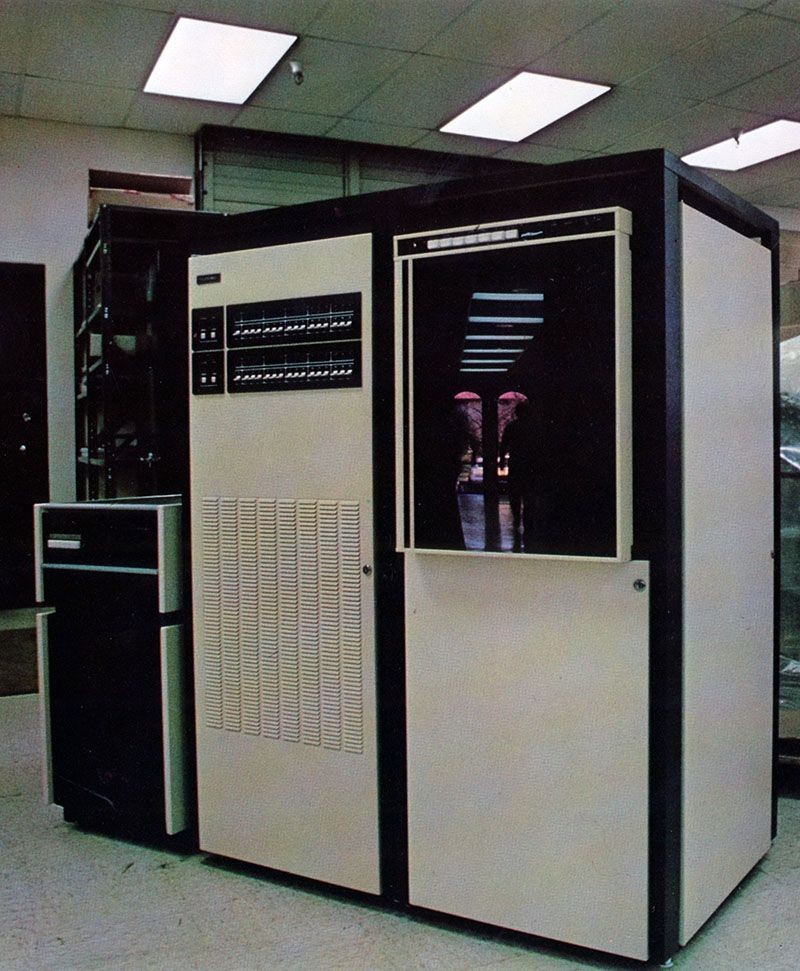

1945: Two professors at the University of Pennsylvania, John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, design and build the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator (ENIAC). The machine is the first "automatic, general-purpose, electronic, decimal, digital computer," according to Edwin D. Reilly's book "Milestones in Computer Science and Information Technology" (Greenwood Press, 2003).

1946: Mauchly and Presper leave the University of Pennsylvania and receive funding from the Census Bureau to build the UNIVAC, the first commercial computer for business and government applications.

1947: William Shockley, John Bardeen and Walter Brattain of Bell Laboratories invent the transistor . They discover how to make an electric switch with solid materials and without the need for a vacuum.

1949: A team at the University of Cambridge develops the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC), "the first practical stored-program computer," according to O'Regan. "EDSAC ran its first program in May 1949 when it calculated a table of squares and a list of prime numbers ," O'Regan wrote. In November 1949, scientists with the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), now called CSIRO, build Australia's first digital computer called the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research Automatic Computer (CSIRAC). CSIRAC is the first digital computer in the world to play music, according to O'Regan.

Late 20th century

1953: Grace Hopper develops the first computer language, which eventually becomes known as COBOL, which stands for COmmon, Business-Oriented Language according to the National Museum of American History . Hopper is later dubbed the "First Lady of Software" in her posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom citation. Thomas Johnson Watson Jr., son of IBM CEO Thomas Johnson Watson Sr., conceives the IBM 701 EDPM to help the United Nations keep tabs on Korea during the war.

1954: John Backus and his team of programmers at IBM publish a paper describing their newly created FORTRAN programming language, an acronym for FORmula TRANslation, according to MIT .

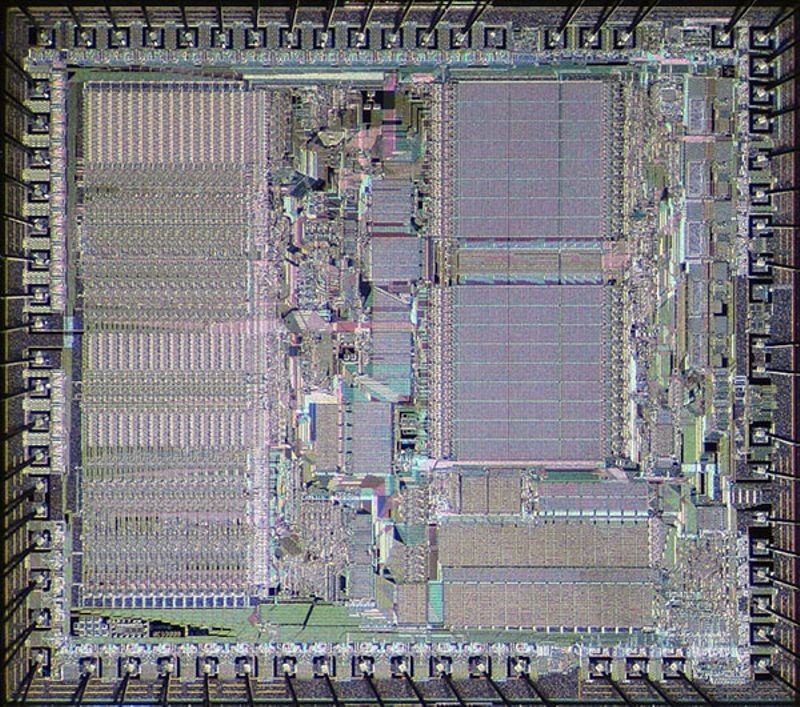

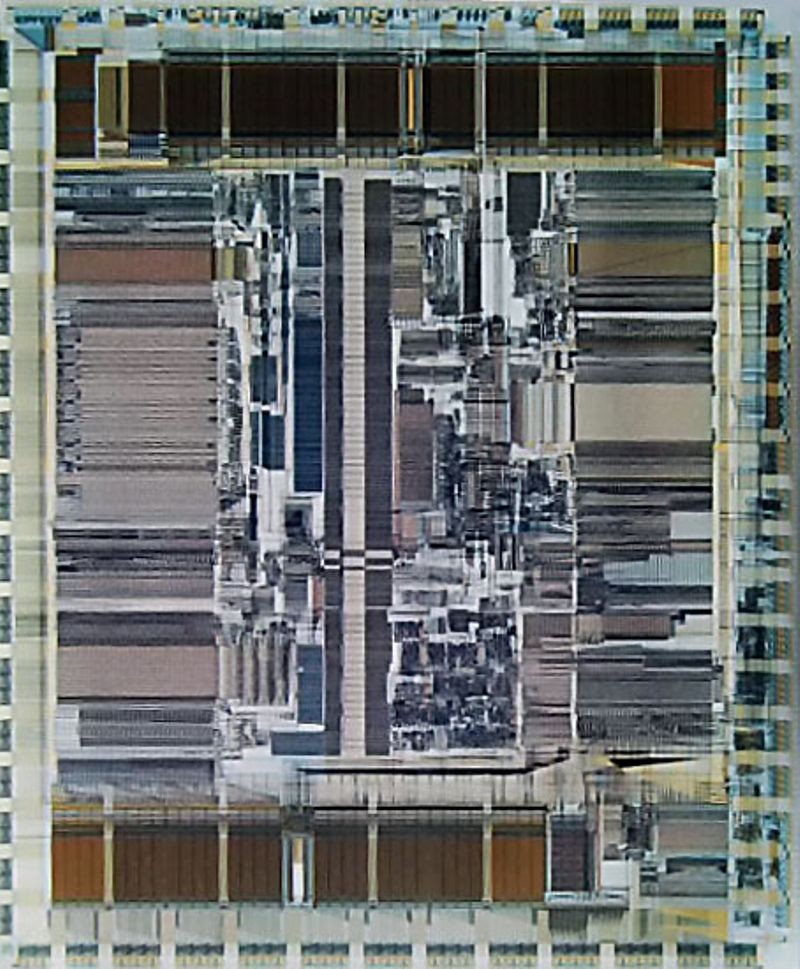

1958: Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce unveil the integrated circuit, known as the computer chip. Kilby is later awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work.

1968: Douglas Engelbart reveals a prototype of the modern computer at the Fall Joint Computer Conference, San Francisco. His presentation, called "A Research Center for Augmenting Human Intellect" includes a live demonstration of his computer, including a mouse and a graphical user interface (GUI), according to the Doug Engelbart Institute . This marks the development of the computer from a specialized machine for academics to a technology that is more accessible to the general public.

1969: Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie and a group of other developers at Bell Labs produce UNIX, an operating system that made "large-scale networking of diverse computing systems — and the internet — practical," according to Bell Labs .. The team behind UNIX continued to develop the operating system using the C programming language, which they also optimized.

1970: The newly formed Intel unveils the Intel 1103, the first Dynamic Access Memory (DRAM) chip.

1971: A team of IBM engineers led by Alan Shugart invents the "floppy disk," enabling data to be shared among different computers.

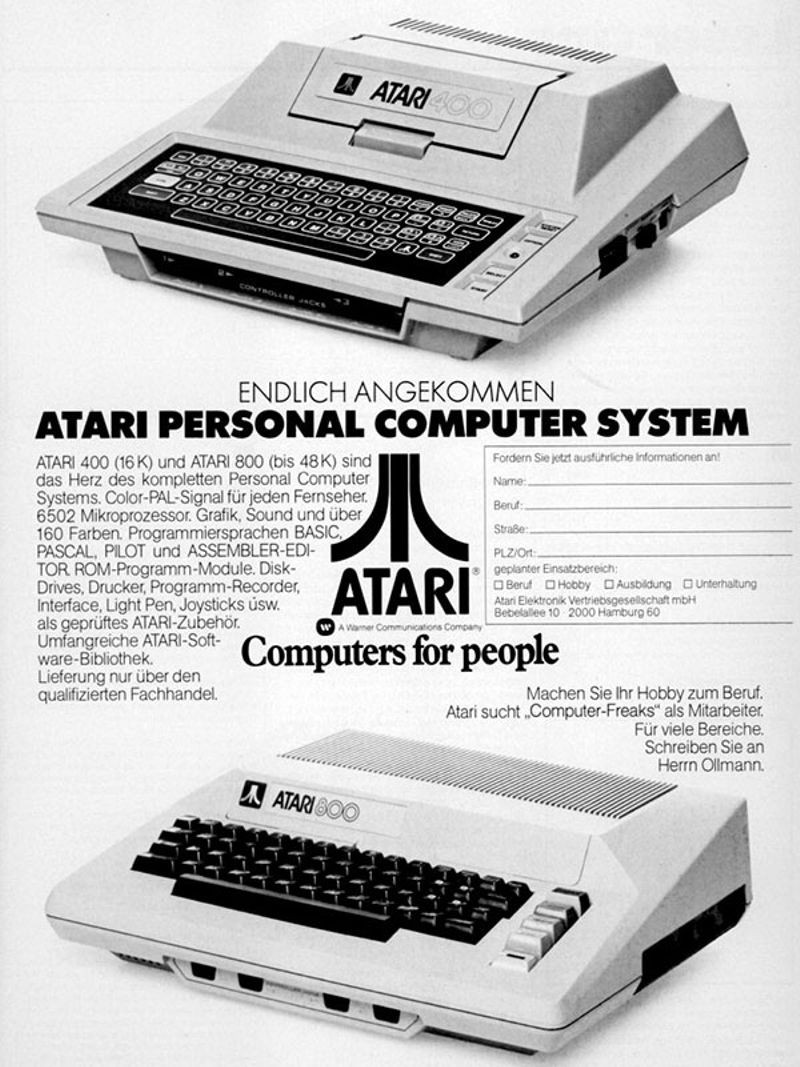

1972: Ralph Baer, a German-American engineer, releases Magnavox Odyssey, the world's first home game console, in September 1972 , according to the Computer Museum of America . Months later, entrepreneur Nolan Bushnell and engineer Al Alcorn with Atari release Pong, the world's first commercially successful video game.

1973: Robert Metcalfe, a member of the research staff for Xerox, develops Ethernet for connecting multiple computers and other hardware.

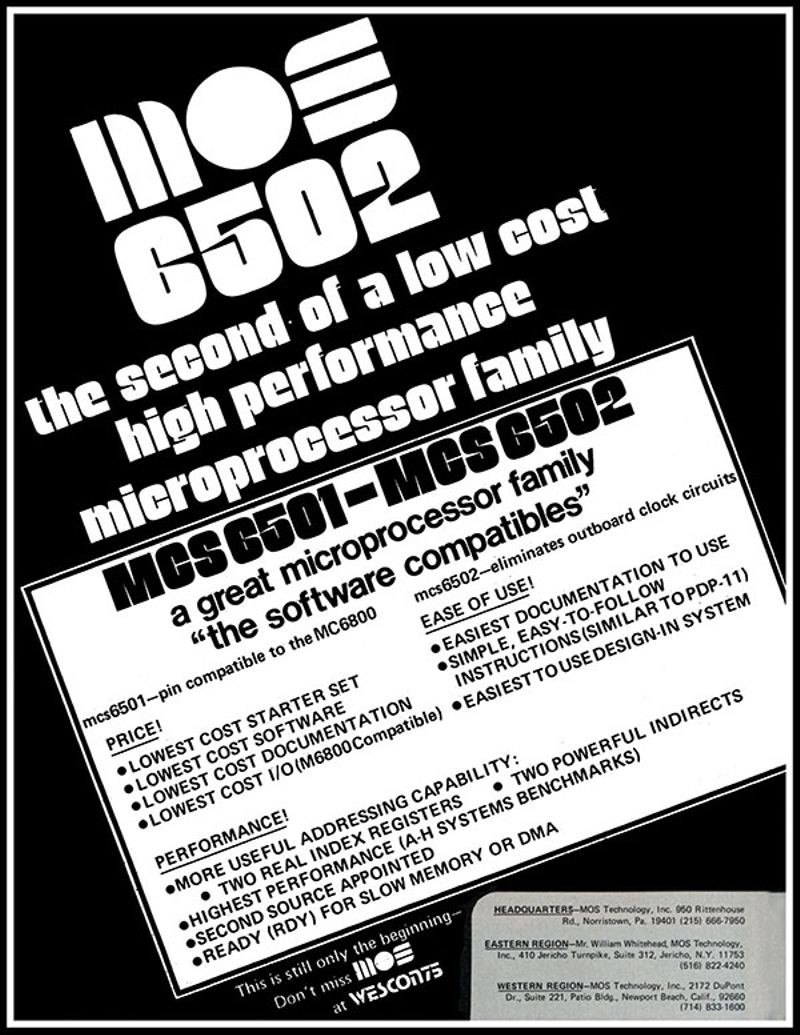

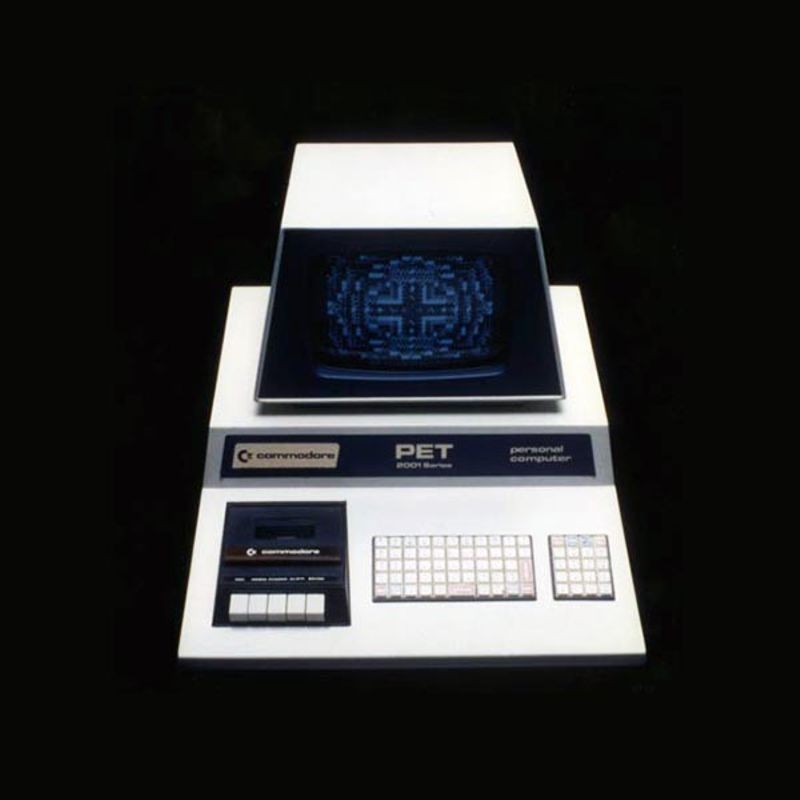

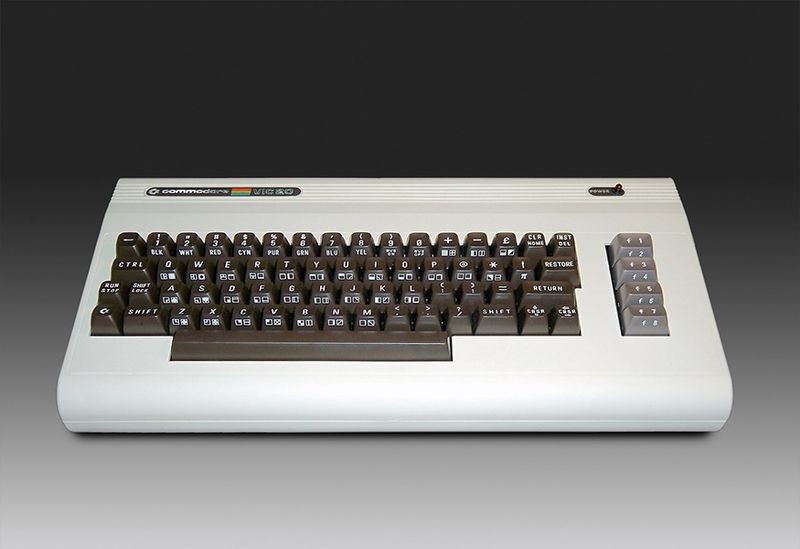

1977: The Commodore Personal Electronic Transactor (PET), is released onto the home computer market, featuring an MOS Technology 8-bit 6502 microprocessor, which controls the screen, keyboard and cassette player. The PET is especially successful in the education market, according to O'Regan.

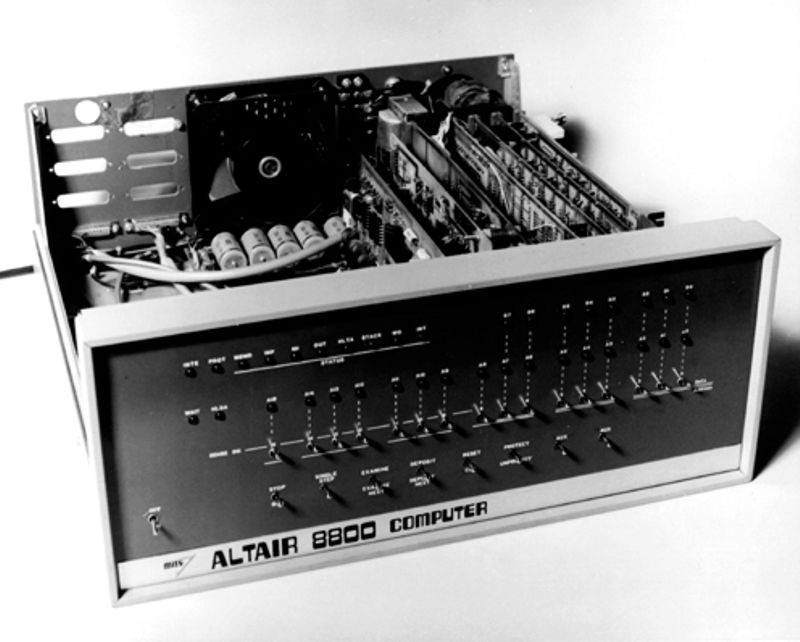

1975: The magazine cover of the January issue of "Popular Electronics" highlights the Altair 8080 as the "world's first minicomputer kit to rival commercial models." After seeing the magazine issue, two "computer geeks," Paul Allen and Bill Gates, offer to write software for the Altair, using the new BASIC language. On April 4, after the success of this first endeavor, the two childhood friends form their own software company, Microsoft.

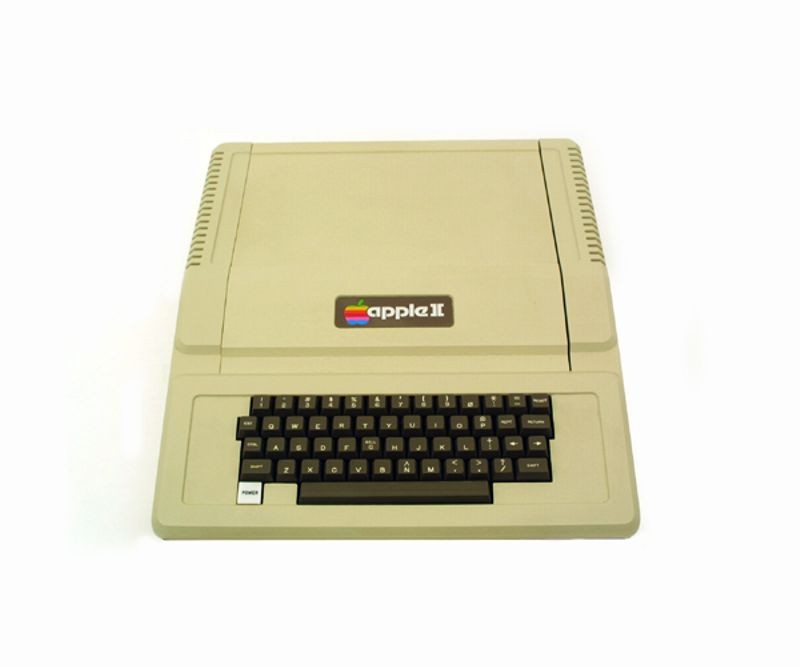

1976: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak co-found Apple Computer on April Fool's Day. They unveil Apple I, the first computer with a single-circuit board and ROM (Read Only Memory), according to MIT .

1977: Radio Shack began its initial production run of 3,000 TRS-80 Model 1 computers — disparagingly known as the "Trash 80" — priced at $599, according to the National Museum of American History. Within a year, the company took 250,000 orders for the computer, according to the book " How TRS-80 Enthusiasts Helped Spark the PC Revolution " (The Seeker Books, 2007).

1977: The first West Coast Computer Faire is held in San Francisco. Jobs and Wozniak present the Apple II computer at the Faire, which includes color graphics and features an audio cassette drive for storage.

1978: VisiCalc, the first computerized spreadsheet program is introduced.

1979: MicroPro International, founded by software engineer Seymour Rubenstein, releases WordStar, the world's first commercially successful word processor. WordStar is programmed by Rob Barnaby, and includes 137,000 lines of code, according to Matthew G. Kirschenbaum's book " Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing " (Harvard University Press, 2016).

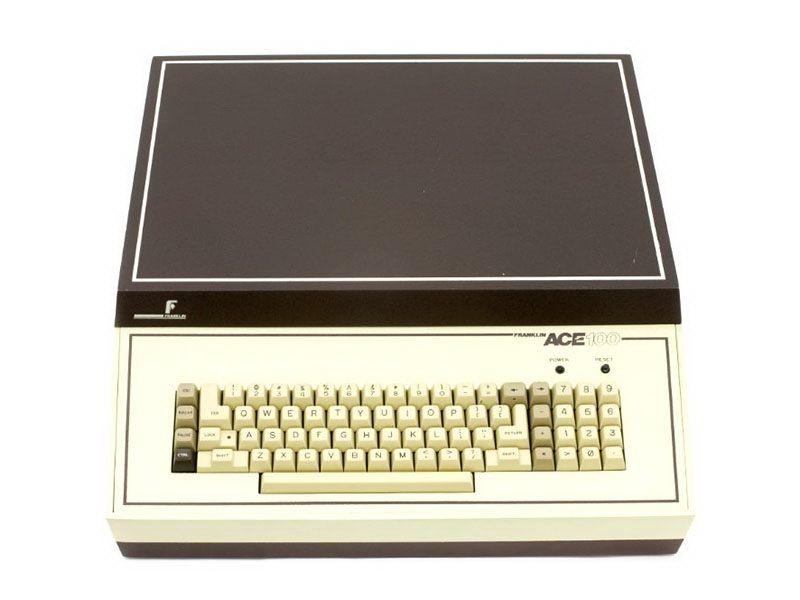

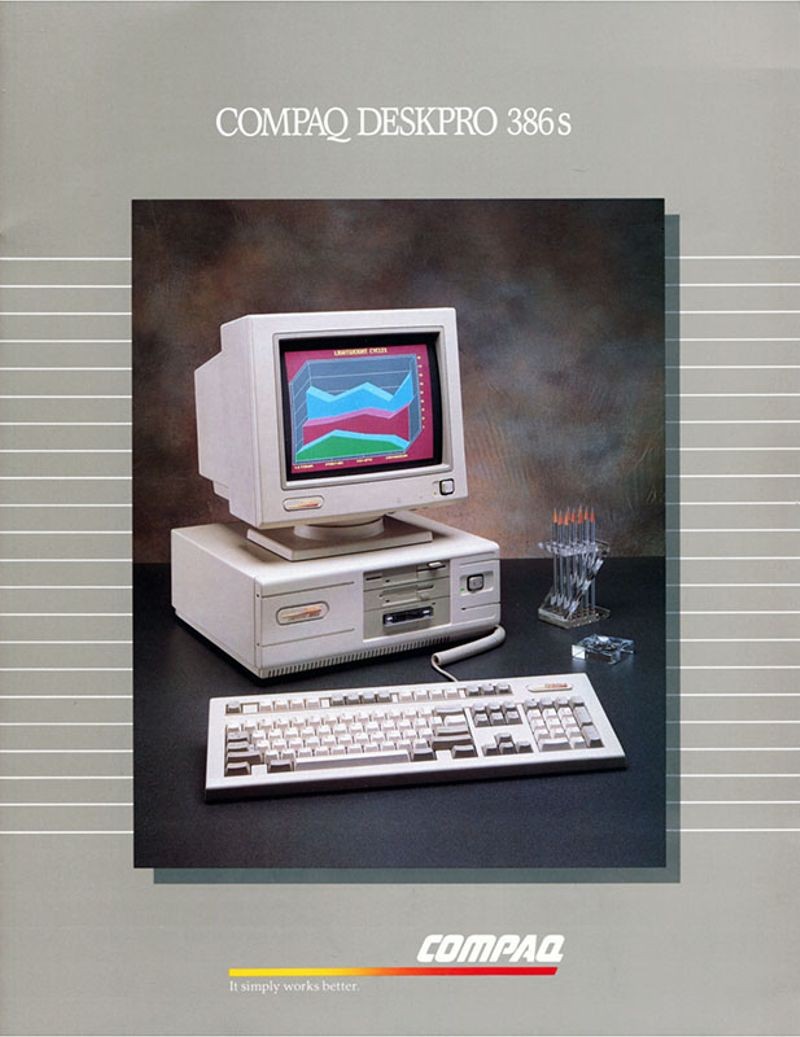

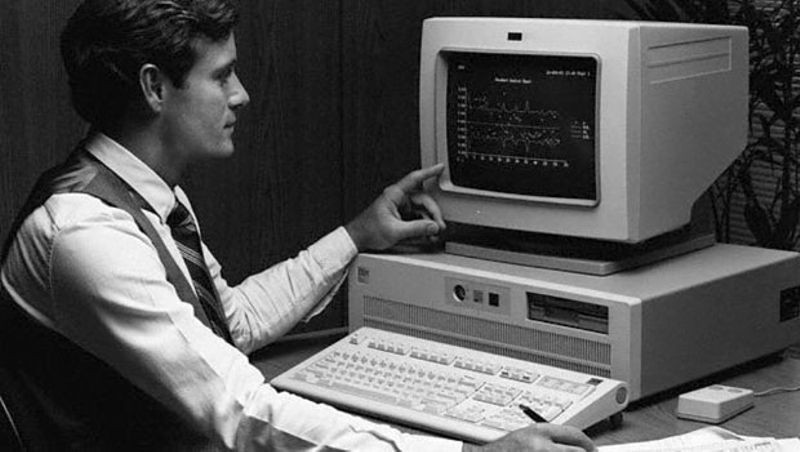

1981: "Acorn," IBM's first personal computer, is released onto the market at a price point of $1,565, according to IBM. Acorn uses the MS-DOS operating system from Windows. Optional features include a display, printer, two diskette drives, extra memory, a game adapter and more.

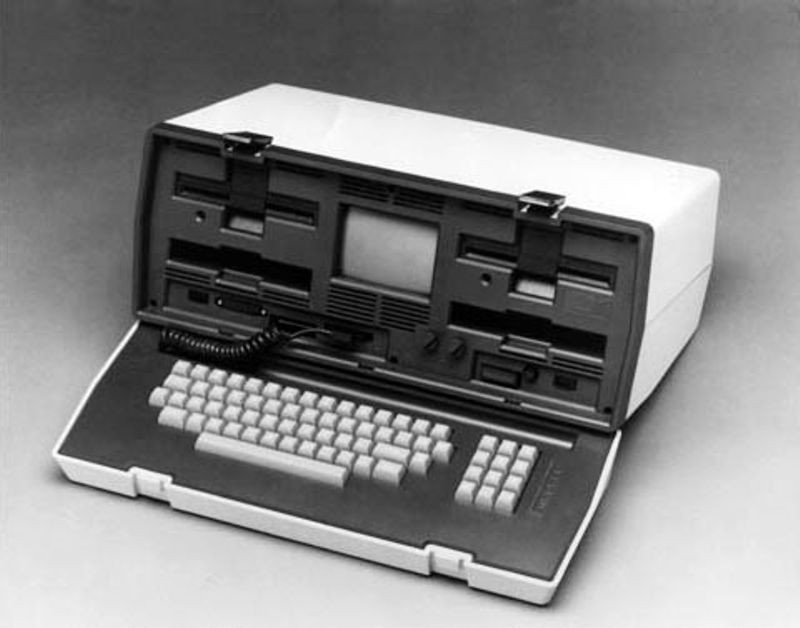

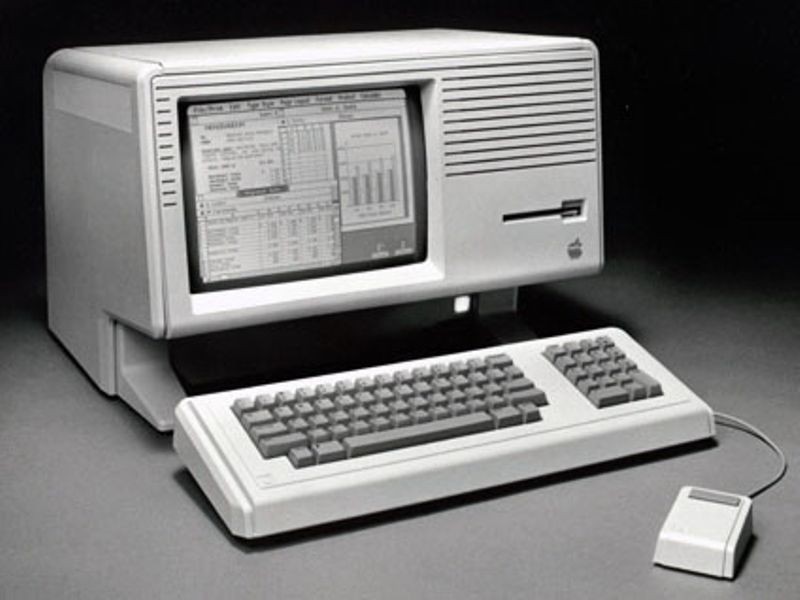

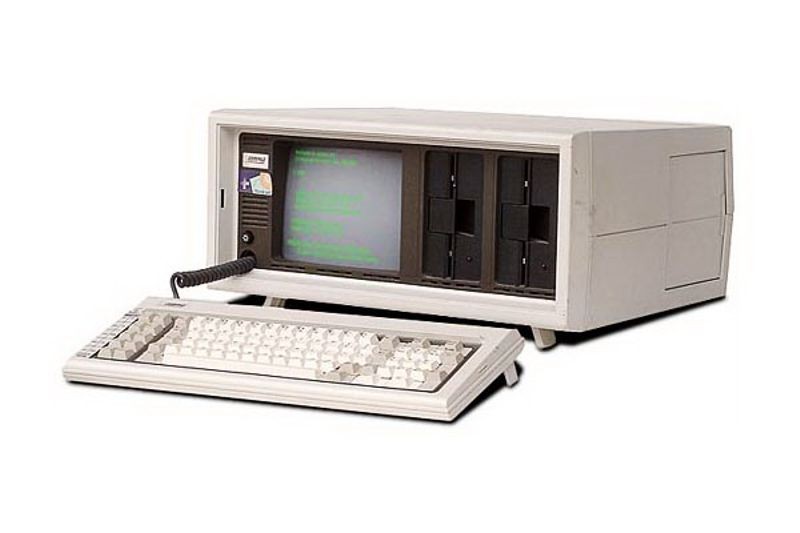

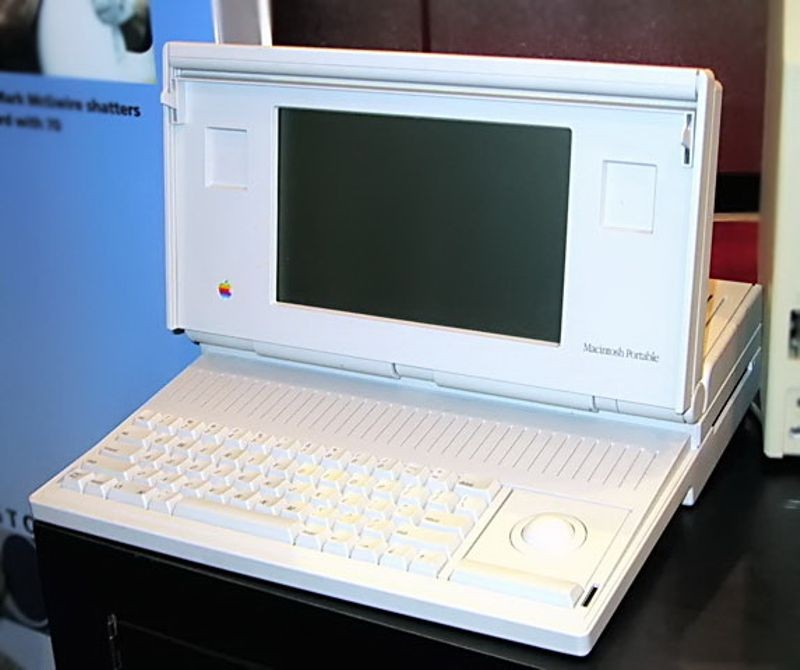

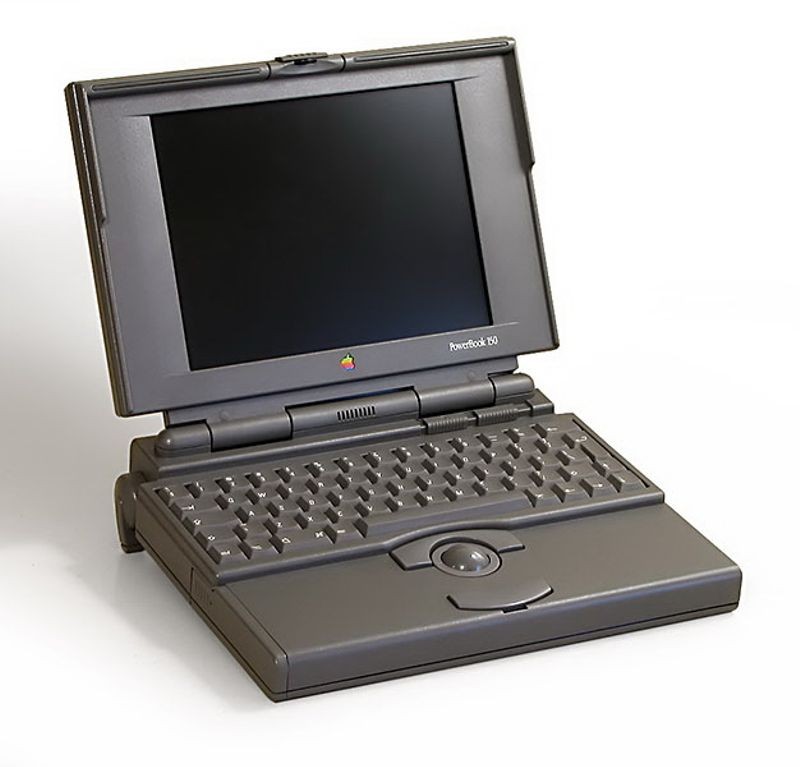

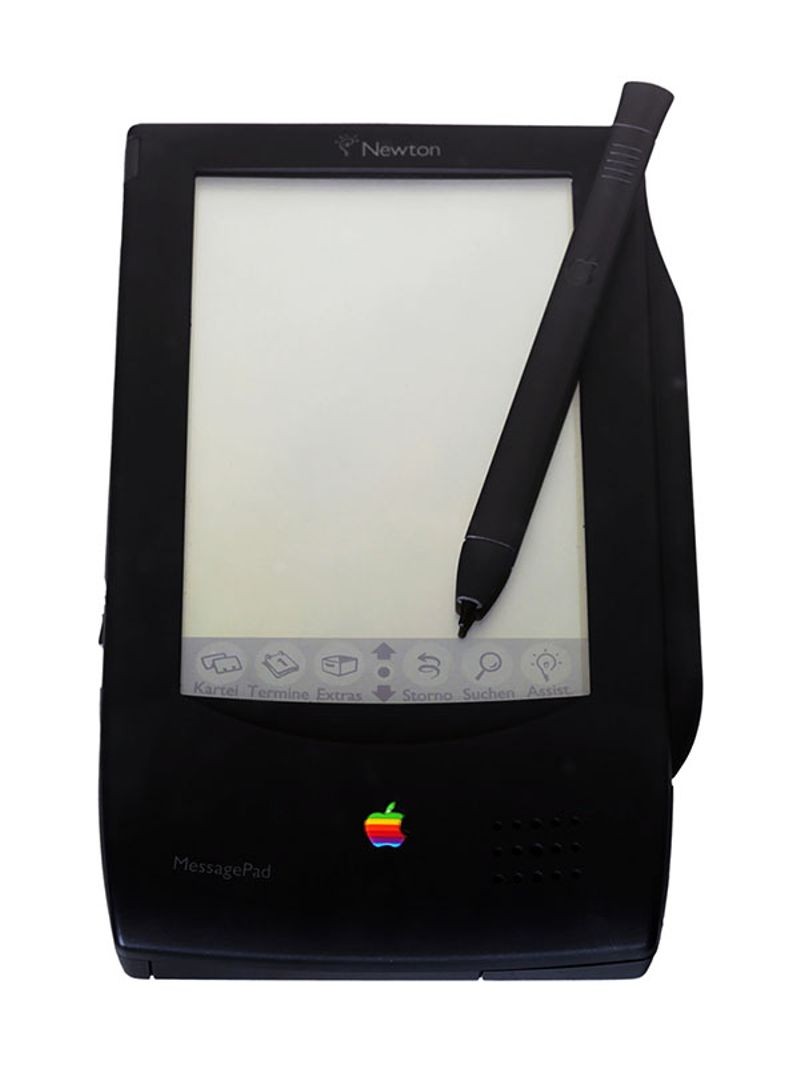

1983: The Apple Lisa, standing for "Local Integrated Software Architecture" but also the name of Steve Jobs' daughter, according to the National Museum of American History ( NMAH ), is the first personal computer to feature a GUI. The machine also includes a drop-down menu and icons. Also this year, the Gavilan SC is released and is the first portable computer with a flip-form design and the very first to be sold as a "laptop."

1984: The Apple Macintosh is announced to the world during a Superbowl advertisement. The Macintosh is launched with a retail price of $2,500, according to the NMAH.

1985 : As a response to the Apple Lisa's GUI, Microsoft releases Windows in November 1985, the Guardian reported . Meanwhile, Commodore announces the Amiga 1000.

1989: Tim Berners-Lee, a British researcher at the European Organization for Nuclear Research ( CERN ), submits his proposal for what would become the World Wide Web. His paper details his ideas for Hyper Text Markup Language (HTML), the building blocks of the Web.

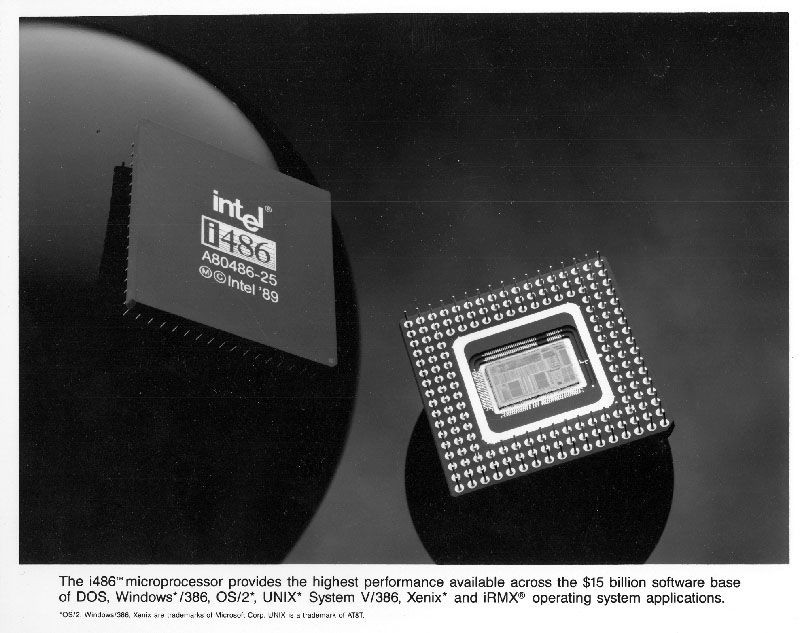

1993: The Pentium microprocessor advances the use of graphics and music on PCs.

1996: Sergey Brin and Larry Page develop the Google search engine at Stanford University.

1997: Microsoft invests $150 million in Apple, which at the time is struggling financially. This investment ends an ongoing court case in which Apple accused Microsoft of copying its operating system.

1999: Wi-Fi, the abbreviated term for "wireless fidelity" is developed, initially covering a distance of up to 300 feet (91 meters) Wired reported .

21st century

2001: Mac OS X, later renamed OS X then simply macOS, is released by Apple as the successor to its standard Mac Operating System. OS X goes through 16 different versions, each with "10" as its title, and the first nine iterations are nicknamed after big cats, with the first being codenamed "Cheetah," TechRadar reported.

2003: AMD's Athlon 64, the first 64-bit processor for personal computers, is released to customers.

2004: The Mozilla Corporation launches Mozilla Firefox 1.0. The Web browser is one of the first major challenges to Internet Explorer, owned by Microsoft. During its first five years, Firefox exceeded a billion downloads by users, according to the Web Design Museum .

2005: Google buys Android, a Linux-based mobile phone operating system

2006: The MacBook Pro from Apple hits the shelves. The Pro is the company's first Intel-based, dual-core mobile computer.

2009: Microsoft launches Windows 7 on July 22. The new operating system features the ability to pin applications to the taskbar, scatter windows away by shaking another window, easy-to-access jumplists, easier previews of tiles and more, TechRadar reported .

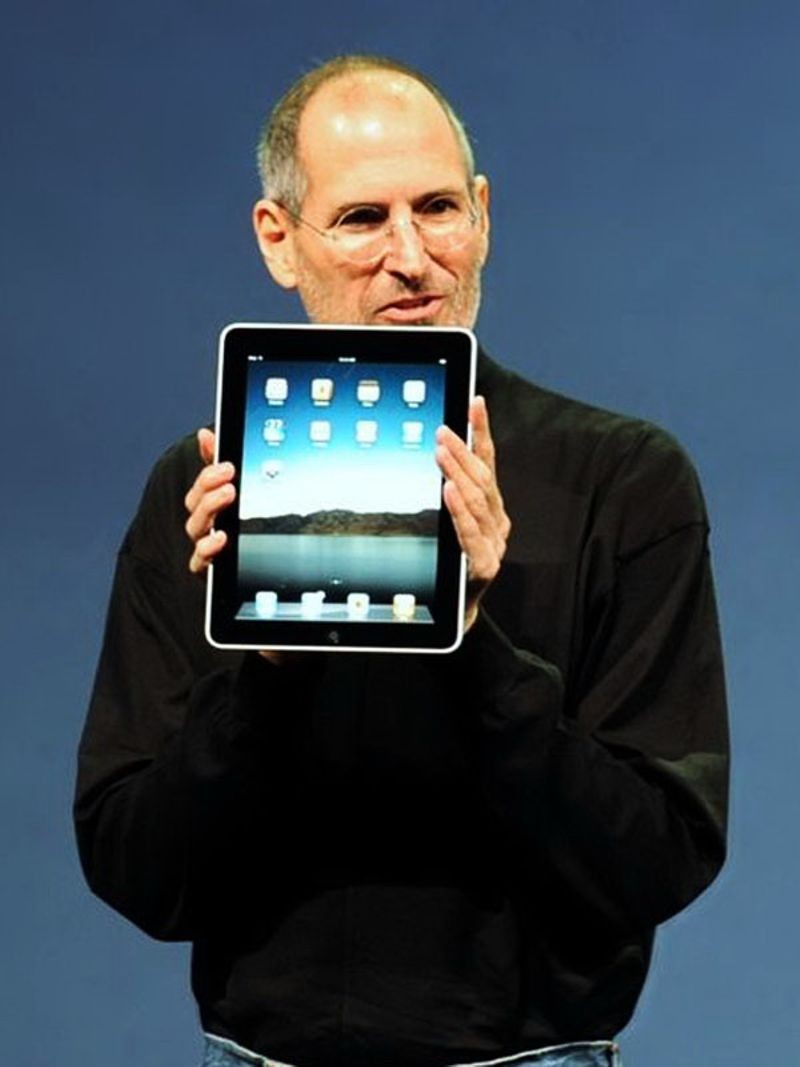

2010: The iPad, Apple's flagship handheld tablet, is unveiled.

2011: Google releases the Chromebook, which runs on Google Chrome OS.

2015: Apple releases the Apple Watch. Microsoft releases Windows 10.

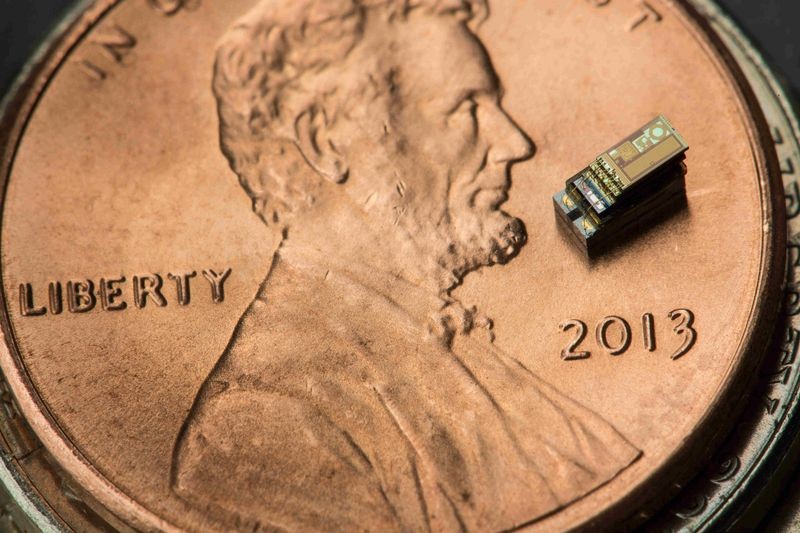

2016: The first reprogrammable quantum computer was created. "Until now, there hasn't been any quantum-computing platform that had the capability to program new algorithms into their system. They're usually each tailored to attack a particular algorithm," said study lead author Shantanu Debnath, a quantum physicist and optical engineer at the University of Maryland, College Park.

2017: The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is developing a new "Molecular Informatics" program that uses molecules as computers. "Chemistry offers a rich set of properties that we may be able to harness for rapid, scalable information storage and processing," Anne Fischer, program manager in DARPA's Defense Sciences Office, said in a statement. "Millions of molecules exist, and each molecule has a unique three-dimensional atomic structure as well as variables such as shape, size, or even color. This richness provides a vast design space for exploring novel and multi-value ways to encode and process data beyond the 0s and 1s of current logic-based, digital architectures."

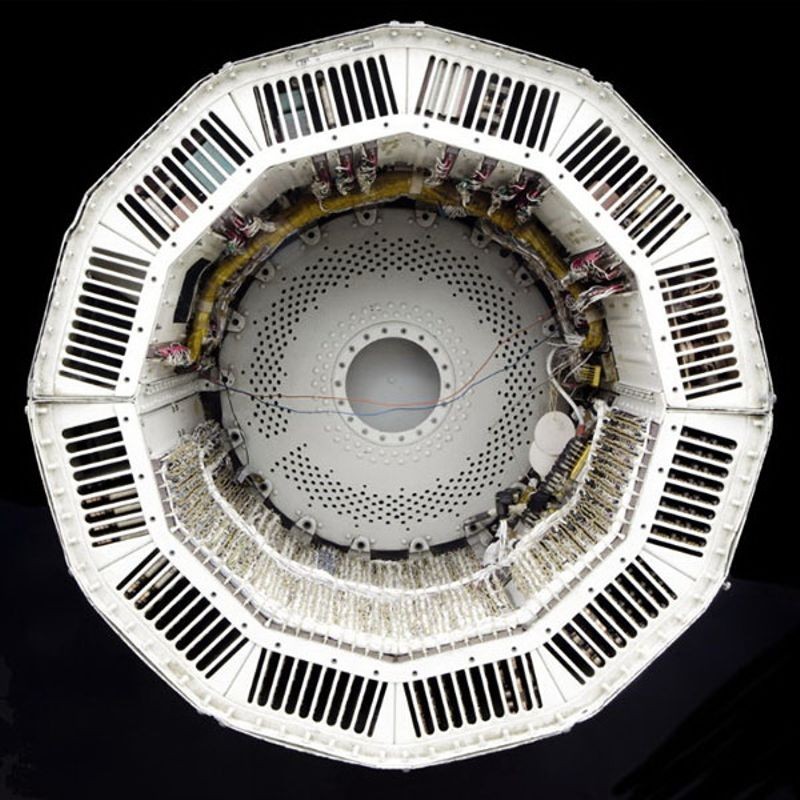

2019: A team at Google became the first to demonstrate quantum supremacy — creating a quantum computer that could feasibly outperform the most powerful classical computer — albeit for a very specific problem with no practical real-world application. The described the computer, dubbed "Sycamore" in a paper that same year in the journal Nature . Achieving quantum advantage – in which a quantum computer solves a problem with real-world applications faster than the most powerful classical computer — is still a ways off.

2022: The first exascale supercomputer, and the world's fastest, Frontier, went online at the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF) in Tennessee. Built by Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) at the cost of $600 million, Frontier uses nearly 10,000 AMD EPYC 7453 64-core CPUs alongside nearly 40,000 AMD Radeon Instinct MI250X GPUs. This machine ushered in the era of exascale computing, which refers to systems that can reach more than one exaFLOP of power – used to measure the performance of a system. Only one machine – Frontier – is currently capable of reaching such levels of performance. It is currently being used as a tool to aid scientific discovery.

What is the first computer in history?

Charles Babbage's Difference Engine, designed in the 1820s, is considered the first "mechanical" computer in history, according to the Science Museum in the U.K . Powered by steam with a hand crank, the machine calculated a series of values and printed the results in a table.

What are the five generations of computing?

The "five generations of computing" is a framework for assessing the entire history of computing and the key technological advancements throughout it.

The first generation, spanning the 1940s to the 1950s, covered vacuum tube-based machines. The second then progressed to incorporate transistor-based computing between the 50s and the 60s. In the 60s and 70s, the third generation gave rise to integrated circuit-based computing. We are now in between the fourth and fifth generations of computing, which are microprocessor-based and AI-based computing.

What is the most powerful computer in the world?

As of November 2023, the most powerful computer in the world is the Frontier supercomputer . The machine, which can reach a performance level of up to 1.102 exaFLOPS, ushered in the age of exascale computing in 2022 when it went online at Tennessee's Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF)

There is, however, a potentially more powerful supercomputer waiting in the wings in the form of the Aurora supercomputer, which is housed at the Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) outside of Chicago. Aurora went online in November 2023. Right now, it lags far behind Frontier, with performance levels of just 585.34 petaFLOPS (roughly half the performance of Frontier), although it's still not finished. When work is completed, the supercomputer is expected to reach performance levels higher than 2 exaFLOPS.

What was the first killer app?

Killer apps are widely understood to be those so essential that they are core to the technology they run on. There have been so many through the years – from Word for Windows in 1989 to iTunes in 2001 to social media apps like WhatsApp in more recent years

Several pieces of software may stake a claim to be the first killer app, but there is a broad consensus that VisiCalc, a spreadsheet program created by VisiCorp and originally released for the Apple II in 1979, holds that title. Steve Jobs even credits this app for propelling the Apple II to become the success it was, according to co-creator Dan Bricklin .

- Fortune: A Look Back At 40 Years of Apple

- The New Yorker: The First Windows

- " A Brief History of Computing " by Gerard O'Regan (Springer, 2021)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Timothy is Editor in Chief of print and digital magazines All About History and History of War . He has previously worked on sister magazine All About Space , as well as photography and creative brands including Digital Photographer and 3D Artist . He has also written for How It Works magazine, several history bookazines and has a degree in English Literature from Bath Spa University .

Prototype quantum processor boasts record 99.9% qubit fidelity

China's upgraded light-powered 'AGI chip' is now a million times more efficient than before, researchers say

Radical quantum computing theory could lead to more powerful machines than previously imagined

Most Popular

- 2 Vikings in Norway were much more likely to die violent deaths than those in Denmark

- 3 Why are some people's mosquito bites itchier than others'? New study hints at answer

- 4 NASA's newly unfurled solar sail has started 'tumbling' end-over-end in orbit, surprising observations show

- 5 Over 40% of pet cats play fetch — but scientists aren't quite sure why

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Modern History of Computing

Historically, computers were human clerks who calculated in accordance with effective methods. These human computers did the sorts of calculation nowadays carried out by electronic computers, and many thousands of them were employed in commerce, government, and research establishments. The term computing machine , used increasingly from the 1920s, refers to any machine that does the work of a human computer, i.e., any machine that calculates in accordance with effective methods. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, with the advent of electronic computing machines, the phrase ‘computing machine’ gradually gave way simply to ‘computer’, initially usually with the prefix ‘electronic’ or ‘digital’. This entry surveys the history of these machines.

- Analog Computers

The Universal Turing Machine

Electromechanical versus electronic computation, turing's automatic computing engine, the manchester machine, eniac and edvac, other notable early computers, high-speed memory, other internet resources, related entries.

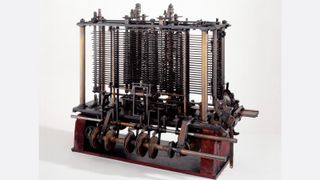

Charles Babbage was Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge University from 1828 to 1839 (a post formerly held by Isaac Newton). Babbage's proposed Difference Engine was a special-purpose digital computing machine for the automatic production of mathematical tables (such as logarithm tables, tide tables, and astronomical tables). The Difference Engine consisted entirely of mechanical components — brass gear wheels, rods, ratchets, pinions, etc. Numbers were represented in the decimal system by the positions of 10-toothed metal wheels mounted in columns. Babbage exhibited a small working model in 1822. He never completed the full-scale machine that he had designed but did complete several fragments. The largest — one ninth of the complete calculator — is on display in the London Science Museum. Babbage used it to perform serious computational work, calculating various mathematical tables. In 1990, Babbage's Difference Engine No. 2 was finally built from Babbage's designs and is also on display at the London Science Museum.

The Swedes Georg and Edvard Scheutz (father and son) constructed a modified version of Babbage's Difference Engine. Three were made, a prototype and two commercial models, one of these being sold to an observatory in Albany, New York, and the other to the Registrar-General's office in London, where it calculated and printed actuarial tables.

Babbage's proposed Analytical Engine, considerably more ambitious than the Difference Engine, was to have been a general-purpose mechanical digital computer. The Analytical Engine was to have had a memory store and a central processing unit (or ‘mill’) and would have been able to select from among alternative actions consequent upon the outcome of its previous actions (a facility nowadays known as conditional branching). The behaviour of the Analytical Engine would have been controlled by a program of instructions contained on punched cards connected together with ribbons (an idea that Babbage had adopted from the Jacquard weaving loom). Babbage emphasised the generality of the Analytical Engine, saying ‘the conditions which enable a finite machine to make calculations of unlimited extent are fulfilled in the Analytical Engine’ (Babbage [1994], p. 97).

Babbage worked closely with Ada Lovelace, daughter of the poet Byron, after whom the modern programming language ADA is named. Lovelace foresaw the possibility of using the Analytical Engine for non-numeric computation, suggesting that the Engine might even be capable of composing elaborate pieces of music.

A large model of the Analytical Engine was under construction at the time of Babbage's death in 1871 but a full-scale version was never built. Babbage's idea of a general-purpose calculating engine was never forgotten, especially at Cambridge, and was on occasion a lively topic of mealtime discussion at the war-time headquarters of the Government Code and Cypher School, Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, birthplace of the electronic digital computer.

Analog computers

The earliest computing machines in wide use were not digital but analog. In analog representation, properties of the representational medium ape (or reflect or model) properties of the represented state-of-affairs. (In obvious contrast, the strings of binary digits employed in digital representation do not represent by means of possessing some physical property — such as length — whose magnitude varies in proportion to the magnitude of the property that is being represented.) Analog representations form a diverse class. Some examples: the longer a line on a road map, the longer the road that the line represents; the greater the number of clear plastic squares in an architect's model, the greater the number of windows in the building represented; the higher the pitch of an acoustic depth meter, the shallower the water. In analog computers, numerical quantities are represented by, for example, the angle of rotation of a shaft or a difference in electrical potential. Thus the output voltage of the machine at a time might represent the momentary speed of the object being modelled.

As the case of the architect's model makes plain, analog representation may be discrete in nature (there is no such thing as a fractional number of windows). Among computer scientists, the term ‘analog’ is sometimes used narrowly, to indicate representation of one continuously-valued quantity by another (e.g., speed by voltage). As Brian Cantwell Smith has remarked:

‘Analog’ should … be a predicate on a representation whose structure corresponds to that of which it represents … That continuous representations should historically have come to be called analog presumably betrays the recognition that, at the levels at which it matters to us, the world is more foundationally continuous than it is discrete. (Smith [1991], p. 271)

James Thomson, brother of Lord Kelvin, invented the mechanical wheel-and-disc integrator that became the foundation of analog computation (Thomson [1876]). The two brothers constructed a device for computing the integral of the product of two given functions, and Kelvin described (although did not construct) general-purpose analog machines for integrating linear differential equations of any order and for solving simultaneous linear equations. Kelvin's most successful analog computer was his tide predicting machine, which remained in use at the port of Liverpool until the 1960s. Mechanical analog devices based on the wheel-and-disc integrator were in use during World War I for gunnery calculations. Following the war, the design of the integrator was considerably improved by Hannibal Ford (Ford [1919]).

Stanley Fifer reports that the first semi-automatic mechanical analog computer was built in England by the Manchester firm of Metropolitan Vickers prior to 1930 (Fifer [1961], p. 29); however, I have so far been unable to verify this claim. In 1931, Vannevar Bush, working at MIT, built the differential analyser, the first large-scale automatic general-purpose mechanical analog computer. Bush's design was based on the wheel and disc integrator. Soon copies of his machine were in use around the world (including, at Cambridge and Manchester Universities in England, differential analysers built out of kit-set Meccano, the once popular engineering toy).

It required a skilled mechanic equipped with a lead hammer to set up Bush's mechanical differential analyser for each new job. Subsequently, Bush and his colleagues replaced the wheel-and-disc integrators and other mechanical components by electromechanical, and finally by electronic, devices.

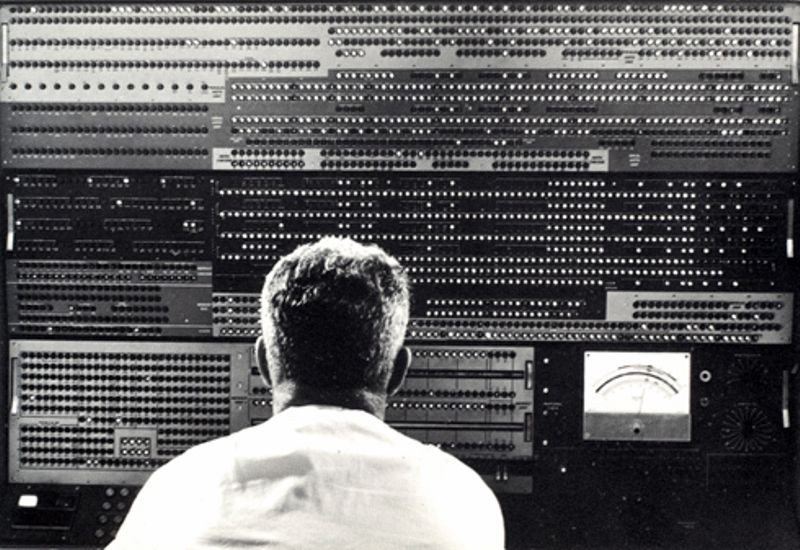

A differential analyser may be conceptualised as a collection of ‘black boxes’ connected together in such a way as to allow considerable feedback. Each box performs a fundamental process, for example addition, multiplication of a variable by a constant, and integration. In setting up the machine for a given task, boxes are connected together so that the desired set of fundamental processes is executed. In the case of electrical machines, this was done typically by plugging wires into sockets on a patch panel (computing machines whose function is determined in this way are referred to as ‘program-controlled’).

Since all the boxes work in parallel, an electronic differential analyser solves sets of equations very quickly. Against this has to be set the cost of massaging the problem to be solved into the form demanded by the analog machine, and of setting up the hardware to perform the desired computation. A major drawback of analog computation is the higher cost, relative to digital machines, of an increase in precision. During the 1960s and 1970s, there was considerable interest in ‘hybrid’ machines, where an analog section is controlled by and programmed via a digital section. However, such machines are now a rarity.

In 1936, at Cambridge University, Turing invented the principle of the modern computer. He described an abstract digital computing machine consisting of a limitless memory and a scanner that moves back and forth through the memory, symbol by symbol, reading what it finds and writing further symbols (Turing [1936]). The actions of the scanner are dictated by a program of instructions that is stored in the memory in the form of symbols. This is Turing's stored-program concept, and implicit in it is the possibility of the machine operating on and modifying its own program. (In London in 1947, in the course of what was, so far as is known, the earliest public lecture to mention computer intelligence, Turing said, ‘What we want is a machine that can learn from experience’, adding that the ‘possibility of letting the machine alter its own instructions provides the mechanism for this’ (Turing [1947] p. 393). Turing's computing machine of 1936 is now known simply as the universal Turing machine. Cambridge mathematician Max Newman remarked that right from the start Turing was interested in the possibility of actually building a computing machine of the sort that he had described (Newman in interview with Christopher Evans in Evans [197?].

From the start of the Second World War Turing was a leading cryptanalyst at the Government Code and Cypher School, Bletchley Park. Here he became familiar with Thomas Flowers' work involving large-scale high-speed electronic switching (described below). However, Turing could not turn to the project of building an electronic stored-program computing machine until the cessation of hostilities in Europe in 1945.

During the wartime years Turing did give considerable thought to the question of machine intelligence. Colleagues at Bletchley Park recall numerous off-duty discussions with him on the topic, and at one point Turing circulated a typewritten report (now lost) setting out some of his ideas. One of these colleagues, Donald Michie (who later founded the Department of Machine Intelligence and Perception at the University of Edinburgh), remembers Turing talking often about the possibility of computing machines (1) learning from experience and (2) solving problems by means of searching through the space of possible solutions, guided by rule-of-thumb principles (Michie in interview with Copeland, 1995). The modern term for the latter idea is ‘heuristic search’, a heuristic being any rule-of-thumb principle that cuts down the amount of searching required in order to find a solution to a problem. At Bletchley Park Turing illustrated his ideas on machine intelligence by reference to chess. Michie recalls Turing experimenting with heuristics that later became common in chess programming (in particular minimax and best-first).

Further information about Turing and the computer, including his wartime work on codebreaking and his thinking about artificial intelligence and artificial life, can be found in Copeland 2004.

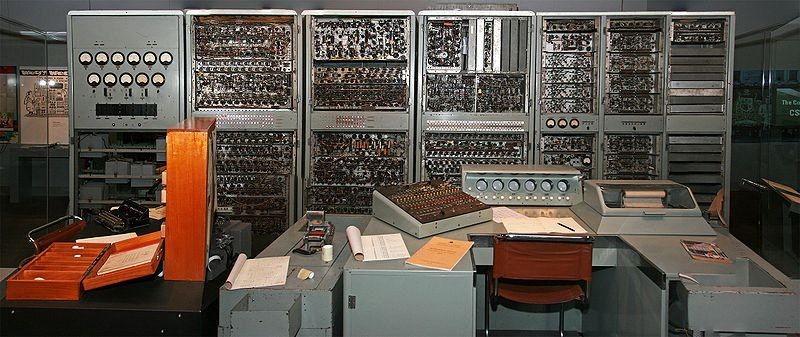

With some exceptions — including Babbage's purely mechanical engines, and the finger-powered National Accounting Machine - early digital computing machines were electromechanical. That is to say, their basic components were small, electrically-driven, mechanical switches called ‘relays’. These operate relatively slowly, whereas the basic components of an electronic computer — originally vacuum tubes (valves) — have no moving parts save electrons and so operate extremely fast. Electromechanical digital computing machines were built before and during the second world war by (among others) Howard Aiken at Harvard University, George Stibitz at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Turing at Princeton University and Bletchley Park, and Konrad Zuse in Berlin. To Zuse belongs the honour of having built the first working general-purpose program-controlled digital computer. This machine, later called the Z3, was functioning in 1941. (A program-controlled computer, as opposed to a stored-program computer, is set up for a new task by re-routing wires, by means of plugs etc.)

Relays were too slow and unreliable a medium for large-scale general-purpose digital computation (although Aiken made a valiant effort). It was the development of high-speed digital techniques using vacuum tubes that made the modern computer possible.

The earliest extensive use of vacuum tubes for digital data-processing appears to have been by the engineer Thomas Flowers, working in London at the British Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill. Electronic equipment designed by Flowers in 1934, for controlling the connections between telephone exchanges, went into operation in 1939, and involved between three and four thousand vacuum tubes running continuously. In 1938–1939 Flowers worked on an experimental electronic digital data-processing system, involving a high-speed data store. Flowers' aim, achieved after the war, was that electronic equipment should replace existing, less reliable, systems built from relays and used in telephone exchanges. Flowers did not investigate the idea of using electronic equipment for numerical calculation, but has remarked that at the outbreak of war with Germany in 1939 he was possibly the only person in Britain who realized that vacuum tubes could be used on a large scale for high-speed digital computation. (See Copeland 2006 for m more information on Flowers' work.)

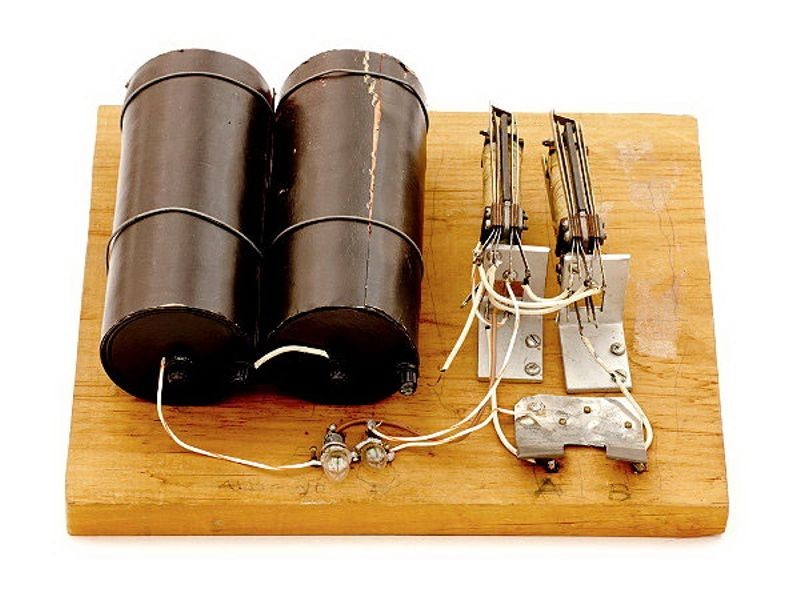

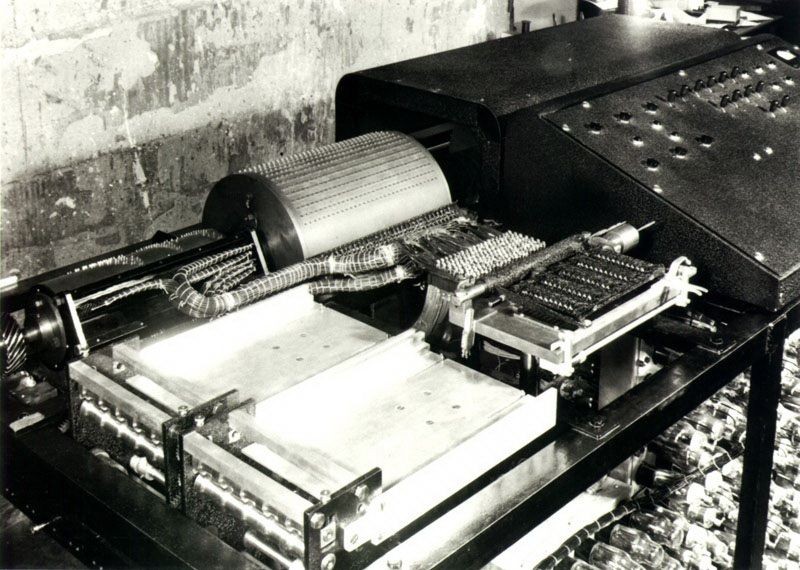

The earliest comparable use of vacuum tubes in the U.S. seems to have been by John Atanasoff at what was then Iowa State College (now University). During the period 1937–1942 Atanasoff developed techniques for using vacuum tubes to perform numerical calculations digitally. In 1939, with the assistance of his student Clifford Berry, Atanasoff began building what is sometimes called the Atanasoff-Berry Computer, or ABC, a small-scale special-purpose electronic digital machine for the solution of systems of linear algebraic equations. The machine contained approximately 300 vacuum tubes. Although the electronic part of the machine functioned successfully, the computer as a whole never worked reliably, errors being introduced by the unsatisfactory binary card-reader. Work was discontinued in 1942 when Atanasoff left Iowa State.

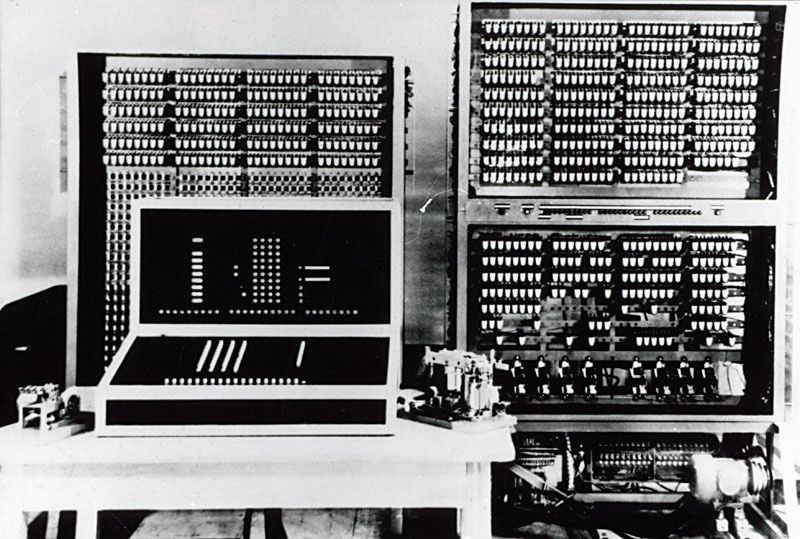

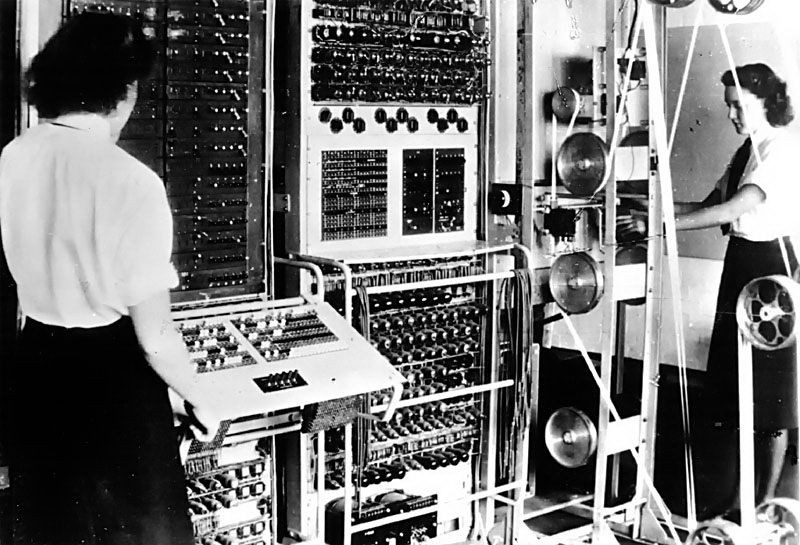

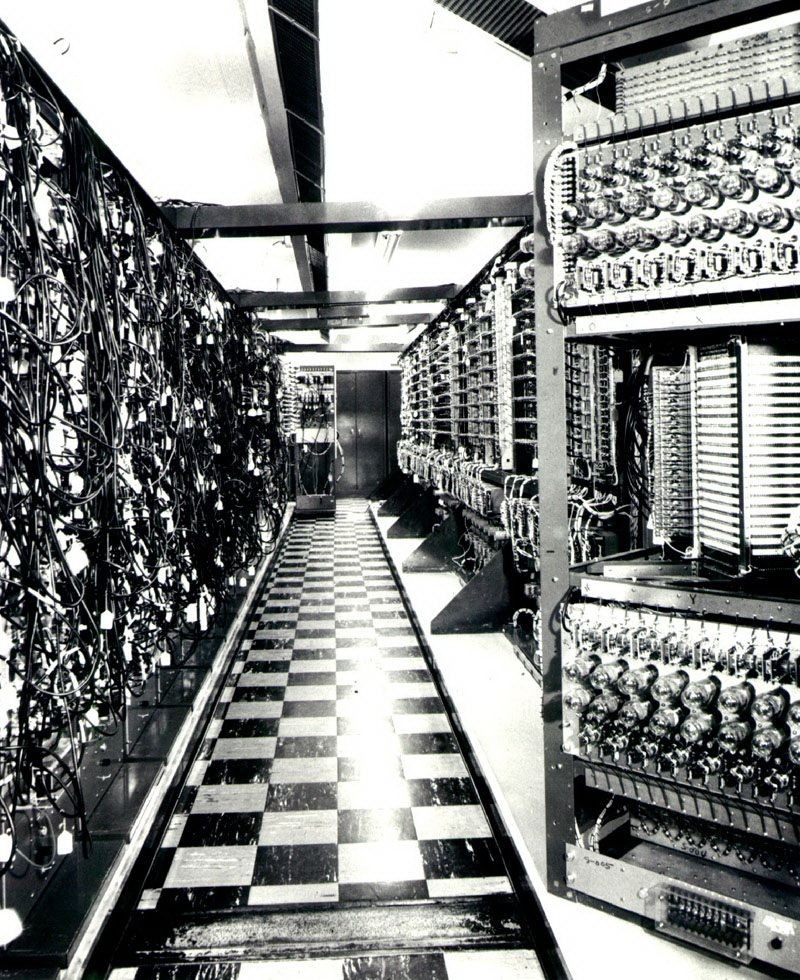

The first fully functioning electronic digital computer was Colossus, used by the Bletchley Park cryptanalysts from February 1944.

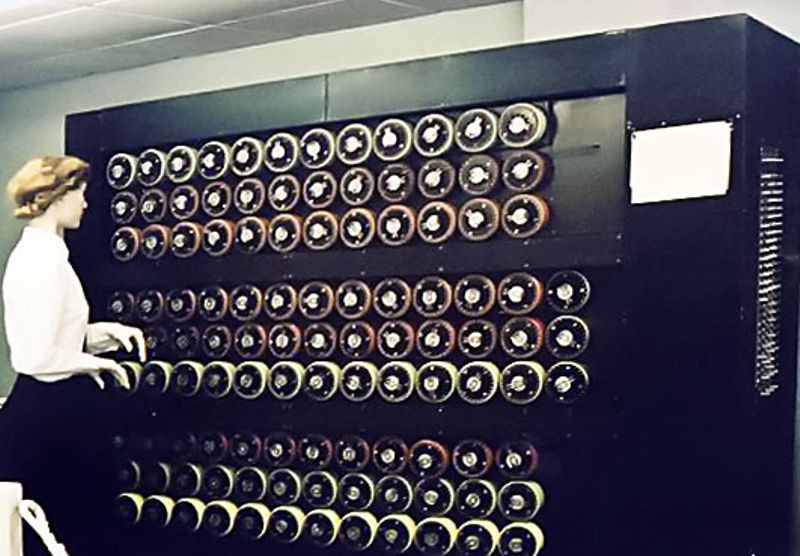

From very early in the war the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) was successfully deciphering German radio communications encoded by means of the Enigma system, and by early 1942 about 39,000 intercepted messages were being decoded each month, thanks to electromechanical machines known as ‘bombes’. These were designed by Turing and Gordon Welchman (building on earlier work by Polish cryptanalysts).

During the second half of 1941, messages encoded by means of a totally different method began to be intercepted. This new cipher machine, code-named ‘Tunny’ by Bletchley Park, was broken in April 1942 and current traffic was read for the first time in July of that year. Based on binary teleprinter code, Tunny was used in preference to Morse-based Enigma for the encryption of high-level signals, for example messages from Hitler and members of the German High Command.

The need to decipher this vital intelligence as rapidly as possible led Max Newman to propose in November 1942 (shortly after his recruitment to GC&CS from Cambridge University) that key parts of the decryption process be automated, by means of high-speed electronic counting devices. The first machine designed and built to Newman's specification, known as the Heath Robinson, was relay-based with electronic circuits for counting. (The electronic counters were designed by C.E. Wynn-Williams, who had been using thyratron tubes in counting circuits at the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, since 1932 [Wynn-Williams 1932].) Installed in June 1943, Heath Robinson was unreliable and slow, and its high-speed paper tapes were continually breaking, but it proved the worth of Newman's idea. Flowers recommended that an all-electronic machine be built instead, but he received no official encouragement from GC&CS. Working independently at the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill, Flowers quietly got on with constructing the world's first large-scale programmable electronic digital computer. Colossus I was delivered to Bletchley Park in January 1943.

By the end of the war there were ten Colossi working round the clock at Bletchley Park. From a cryptanalytic viewpoint, a major difference between the prototype Colossus I and the later machines was the addition of the so-called Special Attachment, following a key discovery by cryptanalysts Donald Michie and Jack Good. This broadened the function of Colossus from ‘wheel setting’ — i.e., determining the settings of the encoding wheels of the Tunny machine for a particular message, given the ‘patterns’ of the wheels — to ‘wheel breaking’, i.e., determining the wheel patterns themselves. The wheel patterns were eventually changed daily by the Germans on each of the numerous links between the German Army High Command and Army Group commanders in the field. By 1945 there were as many 30 links in total. About ten of these were broken and read regularly.

Colossus I contained approximately 1600 vacuum tubes and each of the subsequent machines approximately 2400 vacuum tubes. Like the smaller ABC, Colossus lacked two important features of modern computers. First, it had no internally stored programs. To set it up for a new task, the operator had to alter the machine's physical wiring, using plugs and switches. Second, Colossus was not a general-purpose machine, being designed for a specific cryptanalytic task involving counting and Boolean operations.

F.H. Hinsley, official historian of GC&CS, has estimated that the war in Europe was shortened by at least two years as a result of the signals intelligence operation carried out at Bletchley Park, in which Colossus played a major role. Most of the Colossi were destroyed once hostilities ceased. Some of the electronic panels ended up at Newman's Computing Machine Laboratory in Manchester (see below), all trace of their original use having been removed. Two Colossi were retained by GC&CS (renamed GCHQ following the end of the war). The last Colossus is believed to have stopped running in 1960.