10 Grounded Theory Examples (Qualitative Research Method)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Grounded theory is a qualitative research method that involves the construction of theory from data rather than testing theories through data (Birks & Mills, 2015).

In other words, a grounded theory analysis doesn’t start with a hypothesis or theoretical framework, but instead generates a theory during the data analysis process .

This method has garnered a notable amount of attention since its inception in the 1960s by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (Corbin & Strauss, 2015).

Grounded Theory Definition and Overview

A central feature of grounded theory is the continuous interplay between data collection and analysis (Bringer, Johnston, & Brackenridge, 2016).

Grounded theorists start with the data, coding and considering each piece of collected information (for instance, behaviors collected during a psychological study).

As more information is collected, the researcher can reflect upon the data in an ongoing cycle where data informs an ever-growing and evolving theory (Mills, Bonner & Francis, 2017).

As such, the researcher isn’t tied to testing a hypothesis, but instead, can allow surprising and intriguing insights to emerge from the data itself.

Applications of grounded theory are widespread within the field of social sciences . The method has been utilized to provide insight into complex social phenomena such as nursing, education, and business management (Atkinson, 2015).

Grounded theory offers a sound methodology to unearth the complexities of social phenomena that aren’t well-understood in existing theories (McGhee, Marland & Atkinson, 2017).

While the methods of grounded theory can be labor-intensive and time-consuming, the rich, robust theories this approach produces make it a valuable tool in many researchers’ repertoires.

Real-Life Grounded Theory Examples

Title: A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology

Citation: Weatherall, J. W. A. (2000). A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology. Educational Gerontology , 26 (4), 371-386.

Description: This study employed a grounded theory approach to investigate older adults’ use of information technology (IT). Six participants from a senior senior were interviewed about their experiences and opinions regarding computer technology. Consistent with a grounded theory angle, there was no hypothesis to be tested. Rather, themes emerged out of the analysis process. From this, the findings revealed that the participants recognized the importance of IT in modern life, which motivated them to explore its potential. Positive attitudes towards IT were developed and reinforced through direct experience and personal ownership of technology.

Title: A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study

Citation: Jacobson, N. (2009). A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study. BMC International health and human rights , 9 (1), 1-9.

Description: This study aims to develop a taxonomy of dignity by letting the data create the taxonomic categories, rather than imposing the categories upon the analysis. The theory emerged from the textual and thematic analysis of 64 interviews conducted with individuals marginalized by health or social status , as well as those providing services to such populations and professionals working in health and human rights. This approach identified two main forms of dignity that emerged out of the data: “ human dignity ” and “social dignity”.

Title: A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose

Citation: Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research , 27 (1), 78-109.

Description: This study explores the development of noble youth purpose over time using a grounded theory approach. Something notable about this study was that it returned to collect additional data two additional times, demonstrating how grounded theory can be an interactive process. The researchers conducted three waves of interviews with nine adolescents who demonstrated strong commitments to various noble purposes. The findings revealed that commitments grew slowly but steadily in response to positive feedback, with mentors and like-minded peers playing a crucial role in supporting noble purposes.

Title: A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users

Citation: Pace, S. (2004). A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users. International journal of human-computer studies , 60 (3), 327-363.

Description: This study attempted to understand the flow experiences of web users engaged in information-seeking activities, systematically gathering and analyzing data from semi-structured in-depth interviews with web users. By avoiding preconceptions and reviewing the literature only after the theory had emerged, the study aimed to develop a theory based on the data rather than testing preconceived ideas. The study identified key elements of flow experiences, such as the balance between challenges and skills, clear goals and feedback, concentration, a sense of control, a distorted sense of time, and the autotelic experience.

Title: Victimising of school bullying: a grounded theory

Citation: Thornberg, R., Halldin, K., Bolmsjö, N., & Petersson, A. (2013). Victimising of school bullying: A grounded theory. Research Papers in Education , 28 (3), 309-329.

Description: This study aimed to investigate the experiences of individuals who had been victims of school bullying and understand the effects of these experiences, using a grounded theory approach. Through iterative coding of interviews, the researchers identify themes from the data without a pre-conceived idea or hypothesis that they aim to test. The open-minded coding of the data led to the identification of a four-phase process in victimizing: initial attacks, double victimizing, bullying exit, and after-effects of bullying. The study highlighted the social processes involved in victimizing, including external victimizing through stigmatization and social exclusion, as well as internal victimizing through self-isolation, self-doubt, and lingering psychosocial issues.

Hypothetical Grounded Theory Examples

Suggested Title: “Understanding Interprofessional Collaboration in Emergency Medical Services”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Coding and constant comparative analysis

How to Do It: This hypothetical study might begin with conducting in-depth interviews and field observations within several emergency medical teams to collect detailed narratives and behaviors. Multiple rounds of coding and categorizing would be carried out on this raw data, consistently comparing new information with existing categories. As the categories saturate, relationships among them would be identified, with these relationships forming the basis of a new theory bettering our understanding of collaboration in emergency settings. This iterative process of data collection, analysis, and theory development, continually refined based on fresh insights, upholds the essence of a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “The Role of Social Media in Political Engagement Among Young Adults”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Open, axial, and selective coding

Explanation: The study would start by collecting interaction data on various social media platforms, focusing on political discussions engaged in by young adults. Through open, axial, and selective coding, the data would be broken down, compared, and conceptualized. New insights and patterns would gradually form the basis of a theory explaining the role of social media in shaping political engagement, with continuous refinement informed by the gathered data. This process embodies the recursive essence of the grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Transforming Workplace Cultures: An Exploration of Remote Work Trends”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Constant comparative analysis

Explanation: The theoretical study could leverage survey data and in-depth interviews of employees and bosses engaging in remote work to understand the shifts in workplace culture. Coding and constant comparative analysis would enable the identification of core categories and relationships among them. Sustainability and resilience through remote ways of working would be emergent themes. This constant back-and-forth interplay between data collection, analysis, and theory formation aligns strongly with a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Persistence Amidst Challenges: A Grounded Theory Approach to Understanding Resilience in Urban Educators”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Iterative Coding

How to Do It: This study would involve collecting data via interviews from educators in urban school systems. Through iterative coding, data would be constantly analyzed, compared, and categorized to derive meaningful theories about resilience. The researcher would constantly return to the data, refining the developing theory with every successive interaction. This procedure organically incorporates the grounded theory approach’s characteristic iterative nature.

Suggested Title: “Coping Strategies of Patients with Chronic Pain: A Grounded Theory Study”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Line-by-line inductive coding

How to Do It: The study might initiate with in-depth interviews of patients who’ve experienced chronic pain. Line-by-line coding, followed by memoing, helps to immerse oneself in the data, utilizing a grounded theory approach to map out the relationships between categories and their properties. New rounds of interviews would supplement and refine the emergent theory further. The subsequent theory would then be a detailed, data-grounded exploration of how patients cope with chronic pain.

Grounded theory is an innovative way to gather qualitative data that can help introduce new thoughts, theories, and ideas into academic literature. While it has its strength in allowing the “data to do the talking”, it also has some key limitations – namely, often, it leads to results that have already been found in the academic literature. Studies that try to build upon current knowledge by testing new hypotheses are, in general, more laser-focused on ensuring we push current knowledge forward. Nevertheless, a grounded theory approach is very useful in many circumstances, revealing important new information that may not be generated through other approaches. So, overall, this methodology has great value for qualitative researchers, and can be extremely useful, especially when exploring specific case study projects . I also find it to synthesize well with action research projects .

Atkinson, P. (2015). Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: Valid qualitative research strategies for educators. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 6 (1), 83-86.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . London: Sage.

Bringer, J. D., Johnston, L. H., & Brackenridge, C. H. (2016). Using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software to develop a grounded theory project. Field Methods, 18 (3), 245-266.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . Sage publications.

McGhee, G., Marland, G. R., & Atkinson, J. (2017). Grounded theory research: Literature reviewing and reflexivity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29 (3), 654-663.

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2017). Adopting a Constructivist Approach to Grounded Theory: Implications for Research Design. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 13 (2), 81-89.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Privacy Policy

Home » Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Grounded Theory

Definition:

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research methodology that aims to generate theories based on data that are grounded in the empirical reality of the research context. The method involves a systematic process of data collection, coding, categorization, and analysis to identify patterns and relationships in the data.

The ultimate goal is to develop a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, which is based on the data collected and analyzed rather than on preconceived notions or hypotheses. The resulting theory should be able to explain the phenomenon in a way that is consistent with the data and also accounts for variations and discrepancies in the data. Grounded Theory is widely used in sociology, psychology, management, and other social sciences to study a wide range of phenomena, such as organizational behavior, social interaction, and health care.

History of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory was first introduced by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s as a response to the limitations of traditional positivist approaches to social research. The approach was initially developed to study dying patients and their families in hospitals, but it was soon applied to other areas of sociology and beyond.

Glaser and Strauss published their seminal book “The Discovery of Grounded Theory” in 1967, in which they presented their approach to developing theory from empirical data. They argued that existing social theories often did not account for the complexity and diversity of social phenomena, and that the development of theory should be grounded in empirical data.

Since then, Grounded Theory has become a widely used methodology in the social sciences, and has been applied to a wide range of topics, including healthcare, education, business, and psychology. The approach has also evolved over time, with variations such as constructivist grounded theory and feminist grounded theory being developed to address specific criticisms and limitations of the original approach.

Types of Grounded Theory

There are two main types of Grounded Theory: Classic Grounded Theory and Constructivist Grounded Theory.

Classic Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Glaser and Strauss, and emphasizes the discovery of a theory that is grounded in data. The focus is on generating a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, without being influenced by preconceived notions or existing theories. The process involves a continuous cycle of data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories and subcategories that are grounded in the data. The categories and subcategories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that explains the phenomenon.

Constructivist Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Charmaz, and emphasizes the role of the researcher in the process of theory development. The focus is on understanding how individuals construct meaning and interpret their experiences, rather than on discovering an objective truth. The process involves a reflexive and iterative approach to data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories that are grounded in the data and the researcher’s interpretations of the data. The categories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that accounts for the multiple perspectives and interpretations of the phenomenon being studied.

Grounded Theory Conducting Guide

Here are some general guidelines for conducting a Grounded Theory study:

- Choose a research question: Start by selecting a research question that is open-ended and focuses on a specific social phenomenon or problem.

- Select participants and collect data: Identify a diverse group of participants who have experienced the phenomenon being studied. Use a variety of data collection methods such as interviews, observations, and document analysis to collect rich and diverse data.

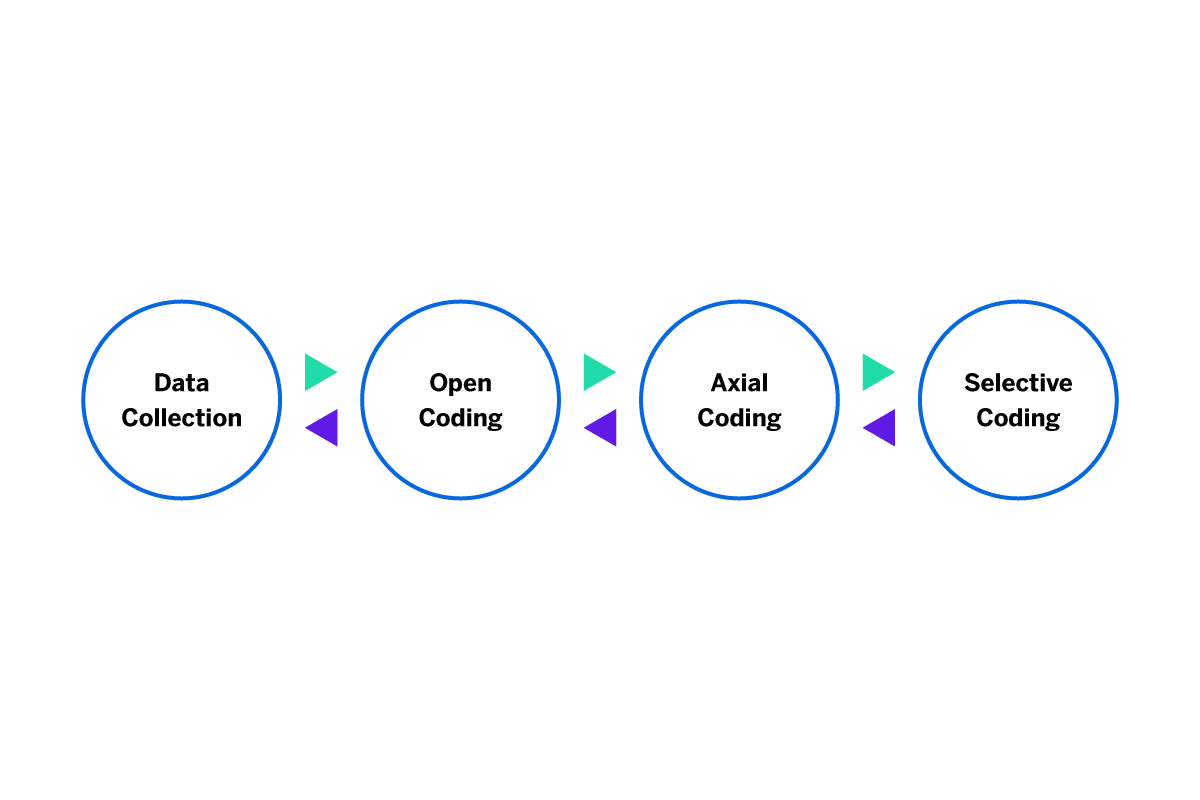

- Analyze the data: Begin the process of analyzing the data using constant comparison. This involves comparing the data to each other and to existing categories and codes, in order to identify patterns and relationships. Use open coding to identify concepts and categories, and then use axial coding to organize them into a theoretical framework.

- Generate categories and codes: Generate categories and codes that describe the phenomenon being studied. Make sure that they are grounded in the data and that they accurately reflect the experiences of the participants.

- Refine and develop the theory: Use theoretical sampling to identify new data sources that are relevant to the developing theory. Use memoing to reflect on insights and ideas that emerge during the analysis process. Continue to refine and develop the theory until it provides a comprehensive explanation of the phenomenon.

- Validate the theory: Finally, seek to validate the theory by testing it against new data and seeking feedback from peers and other researchers. This process helps to refine and improve the theory, and to ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Write up and disseminate the findings: Once the theory is fully developed and validated, write up the findings and disseminate them through academic publications and presentations. Make sure to acknowledge the contributions of the participants and to provide a detailed account of the research methods used.

Data Collection Methods

Grounded Theory Data Collection Methods are as follows:

- Interviews : One of the most common data collection methods in Grounded Theory is the use of in-depth interviews. Interviews allow researchers to gather rich and detailed data about the experiences, perspectives, and attitudes of participants. Interviews can be conducted one-on-one or in a group setting.

- Observation : Observation is another data collection method used in Grounded Theory. Researchers may observe participants in their natural settings, such as in a workplace or community setting. This method can provide insights into the social interactions and behaviors of participants.

- Document analysis: Grounded Theory researchers also use document analysis as a data collection method. This involves analyzing existing documents such as reports, policies, or historical records that are relevant to the phenomenon being studied.

- Focus groups : Focus groups involve bringing together a group of participants to discuss a specific topic or issue. This method can provide insights into group dynamics and social interactions.

- Fieldwork : Fieldwork involves immersing oneself in the research setting and participating in the activities of the participants. This method can provide an in-depth understanding of the culture and social dynamics of the research setting.

- Multimedia data: Grounded Theory researchers may also use multimedia data such as photographs, videos, or audio recordings to capture the experiences and perspectives of participants.

Data Analysis Methods

Grounded Theory Data Analysis Methods are as follows:

- Open coding: Open coding is the process of identifying concepts and categories in the data. Researchers use open coding to assign codes to different pieces of data, and to identify similarities and differences between them.

- Axial coding: Axial coding is the process of organizing the codes into broader categories and subcategories. Researchers use axial coding to develop a theoretical framework that explains the phenomenon being studied.

- Constant comparison: Grounded Theory involves a process of constant comparison, in which data is compared to each other and to existing categories and codes in order to identify patterns and relationships.

- Theoretical sampling: Theoretical sampling involves selecting new data sources based on the emerging theory. Researchers use theoretical sampling to collect data that will help refine and validate the theory.

- Memoing : Memoing involves writing down reflections, insights, and ideas as the analysis progresses. This helps researchers to organize their thoughts and develop a deeper understanding of the data.

- Peer debriefing: Peer debriefing involves seeking feedback from peers and other researchers on the developing theory. This process helps to validate the theory and ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Member checking: Member checking involves sharing the emerging theory with the participants in the study and seeking their feedback. This process helps to ensure that the theory accurately reflects the experiences and perspectives of the participants.

- Triangulation: Triangulation involves using multiple sources of data to validate the emerging theory. Researchers may use different data collection methods, different data sources, or different analysts to ensure that the theory is grounded in the data.

Applications of Grounded Theory

Here are some of the key applications of Grounded Theory:

- Social sciences : Grounded Theory is widely used in social science research, particularly in fields such as sociology, psychology, and anthropology. It can be used to explore a wide range of social phenomena, such as social interactions, power dynamics, and cultural practices.

- Healthcare : Grounded Theory can be used in healthcare research to explore patient experiences, healthcare practices, and healthcare systems. It can provide insights into the factors that influence healthcare outcomes, and can inform the development of interventions and policies.

- Education : Grounded Theory can be used in education research to explore teaching and learning processes, student experiences, and educational policies. It can provide insights into the factors that influence educational outcomes, and can inform the development of educational interventions and policies.

- Business : Grounded Theory can be used in business research to explore organizational processes, management practices, and consumer behavior. It can provide insights into the factors that influence business outcomes, and can inform the development of business strategies and policies.

- Technology : Grounded Theory can be used in technology research to explore user experiences, technology adoption, and technology design. It can provide insights into the factors that influence technology outcomes, and can inform the development of technology interventions and policies.

Examples of Grounded Theory

Examples of Grounded Theory in different case studies are as follows:

- Glaser and Strauss (1965): This study, which is considered one of the foundational works of Grounded Theory, explored the experiences of dying patients in a hospital. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of dying, and that was grounded in the data.

- Charmaz (1983): This study explored the experiences of chronic illness among young adults. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained how individuals with chronic illness managed their illness, and how their illness impacted their sense of self.

- Strauss and Corbin (1990): This study explored the experiences of individuals with chronic pain. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the different strategies that individuals used to manage their pain, and that was grounded in the data.

- Glaser and Strauss (1967): This study explored the experiences of individuals who were undergoing a process of becoming disabled. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of becoming disabled, and that was grounded in the data.

- Clarke (2005): This study explored the experiences of patients with cancer who were receiving chemotherapy. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the factors that influenced patient adherence to chemotherapy, and that was grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory Research Example

A Grounded Theory Research Example Would be:

Research question : What is the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process?

Data collection : The researcher conducted interviews with first-generation college students who had recently gone through the college admission process. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis: The researcher used a constant comparative method to analyze the data. This involved coding the data, comparing codes, and constantly revising the codes to identify common themes and patterns. The researcher also used memoing, which involved writing notes and reflections on the data and analysis.

Findings : Through the analysis of the data, the researcher identified several themes related to the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process, such as feeling overwhelmed by the complexity of the process, lacking knowledge about the process, and facing financial barriers.

Theory development: Based on the findings, the researcher developed a theory about the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process. The theory suggested that first-generation college students faced unique challenges in the college admission process due to their lack of knowledge and resources, and that these challenges could be addressed through targeted support programs and resources.

In summary, grounded theory research involves collecting data, analyzing it through constant comparison and memoing, and developing a theory grounded in the data. The resulting theory can help to explain the phenomenon being studied and guide future research and interventions.

Purpose of Grounded Theory

The purpose of Grounded Theory is to develop a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, process, or interaction. This theoretical framework is developed through a rigorous process of data collection, coding, and analysis, and is grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory aims to uncover the social processes and patterns that underlie social phenomena, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these processes and patterns. It is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings, and is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

The ultimate goal of Grounded Theory is to generate a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, and that can be used to explain and predict social phenomena. This theoretical framework can then be used to inform policy and practice, and to guide future research in the field.

When to use Grounded Theory

Following are some situations in which Grounded Theory may be particularly useful:

- Exploring new areas of research: Grounded Theory is particularly useful when exploring new areas of research that have not been well-studied. By collecting and analyzing data, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the social processes and patterns underlying the phenomenon of interest.

- Studying complex social phenomena: Grounded Theory is well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that involve multiple social processes and interactions. By using an iterative process of data collection and analysis, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the complexity of the social phenomenon.

- Generating hypotheses: Grounded Theory can be used to generate hypotheses about social processes and interactions that can be tested in future research. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for further research and hypothesis testing.

- Informing policy and practice : Grounded Theory can provide insights into the factors that influence social phenomena, and can inform policy and practice in a variety of fields. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for intervention and policy development.

Characteristics of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research method that is characterized by several key features, including:

- Emergence : Grounded Theory emphasizes the emergence of theoretical categories and concepts from the data, rather than preconceived theoretical ideas. This means that the researcher does not start with a preconceived theory or hypothesis, but instead allows the theory to emerge from the data.

- Iteration : Grounded Theory is an iterative process that involves constant comparison of data and analysis, with each round of data collection and analysis refining the theoretical framework.

- Inductive : Grounded Theory is an inductive method of analysis, which means that it derives meaning from the data. The researcher starts with the raw data and systematically codes and categorizes it to identify patterns and themes, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these patterns.

- Reflexive : Grounded Theory requires the researcher to be reflexive and self-aware throughout the research process. The researcher’s personal biases and assumptions must be acknowledged and addressed in the analysis process.

- Holistic : Grounded Theory takes a holistic approach to data analysis, looking at the entire data set rather than focusing on individual data points. This allows the researcher to identify patterns and themes that may not be apparent when looking at individual data points.

- Contextual : Grounded Theory emphasizes the importance of understanding the context in which social phenomena occur. This means that the researcher must consider the social, cultural, and historical factors that may influence the phenomenon of interest.

Advantages of Grounded Theory

Advantages of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Flexibility : Grounded Theory is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings. It is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

- Validity : Grounded Theory aims to develop a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, which enhances the validity and reliability of the research findings. The iterative process of data collection and analysis also helps to ensure that the research findings are reliable and robust.

- Originality : Grounded Theory can generate new and original insights into social phenomena, as it is not constrained by preconceived theoretical ideas or hypotheses. This allows researchers to explore new areas of research and generate new theoretical frameworks.

- Real-world relevance: Grounded Theory can inform policy and practice, as it provides insights into the factors that influence social phenomena. The theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be used to inform policy development and intervention strategies.

- Ethical : Grounded Theory is an ethical research method, as it allows participants to have a voice in the research process. Participants’ perspectives are central to the data collection and analysis process, which ensures that their views are taken into account.

- Replication : Grounded Theory is a replicable method of research, as the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be tested and validated in future research.

Limitations of Grounded Theory

Limitations of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Time-consuming: Grounded Theory can be a time-consuming method, as the iterative process of data collection and analysis requires significant time and effort. This can make it difficult to conduct research in a timely and cost-effective manner.

- Subjectivity : Grounded Theory is a subjective method, as the researcher’s personal biases and assumptions can influence the data analysis process. This can lead to potential issues with reliability and validity of the research findings.

- Generalizability : Grounded Theory is a context-specific method, which means that the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. This can limit the applicability of the research findings.

- Lack of structure : Grounded Theory is an exploratory method, which means that it lacks the structure of other research methods, such as surveys or experiments. This can make it difficult to compare findings across different studies.

- Data overload: Grounded Theory can generate a large amount of data, which can be overwhelming for researchers. This can make it difficult to manage and analyze the data effectively.

- Difficulty in publication: Grounded Theory can be challenging to publish in some academic journals, as some reviewers and editors may view it as less rigorous than other research methods.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Multidimensional Scaling – Types, Formulas and...

Descriptive Statistics – Types, Methods and...

Narrative Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Content Analysis – Methods, Types and Examples

Regression Analysis – Methods, Types and Examples

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Res Methodol

How to do a grounded theory study: a worked example of a study of dental practices

Alexandra sbaraini.

1 Centre for Values, Ethics and the Law in Medicine, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

2 Population Oral Health, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Stacy M Carter

R wendell evans, anthony blinkhorn, associated data.

Qualitative methodologies are increasingly popular in medical research. Grounded theory is the methodology most-often cited by authors of qualitative studies in medicine, but it has been suggested that many 'grounded theory' studies are not concordant with the methodology. In this paper we provide a worked example of a grounded theory project. Our aim is to provide a model for practice, to connect medical researchers with a useful methodology, and to increase the quality of 'grounded theory' research published in the medical literature.

We documented a worked example of using grounded theory methodology in practice.

We describe our sampling, data collection, data analysis and interpretation. We explain how these steps were consistent with grounded theory methodology, and show how they related to one another. Grounded theory methodology assisted us to develop a detailed model of the process of adapting preventive protocols into dental practice, and to analyse variation in this process in different dental practices.

Conclusions

By employing grounded theory methodology rigorously, medical researchers can better design and justify their methods, and produce high-quality findings that will be more useful to patients, professionals and the research community.

Qualitative research is increasingly popular in health and medicine. In recent decades, qualitative researchers in health and medicine have founded specialist journals, such as Qualitative Health Research , established 1991, and specialist conferences such as the Qualitative Health Research conference of the International Institute for Qualitative Methodology, established 1994, and the Global Congress for Qualitative Health Research, established 2011 [ 1 - 3 ]. Journals such as the British Medical Journal have published series about qualitative methodology (1995 and 2008) [ 4 , 5 ]. Bodies overseeing human research ethics, such as the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, and the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research [ 6 , 7 ], have included chapters or sections on the ethics of qualitative research. The increasing popularity of qualitative methodologies for medical research has led to an increasing awareness of formal qualitative methodologies. This is particularly so for grounded theory, one of the most-cited qualitative methodologies in medical research [[ 8 ], p47].

Grounded theory has a chequered history [ 9 ]. Many authors label their work 'grounded theory' but do not follow the basics of the methodology [ 10 , 11 ]. This may be in part because there are few practical examples of grounded theory in use in the literature. To address this problem, we will provide a brief outline of the history and diversity of grounded theory methodology, and a worked example of the methodology in practice. Our aim is to provide a model for practice, to connect medical researchers with a useful methodology, and to increase the quality of 'grounded theory' research published in the medical literature.

The history, diversity and basic components of 'grounded theory' methodology and method

Founded on the seminal 1967 book 'The Discovery of Grounded Theory' [ 12 ], the grounded theory tradition is now diverse and somewhat fractured, existing in four main types, with a fifth emerging. Types one and two are the work of the original authors: Barney Glaser's 'Classic Grounded Theory' [ 13 ] and Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin's 'Basics of Qualitative Research' [ 14 ]. Types three and four are Kathy Charmaz's 'Constructivist Grounded Theory' [ 15 ] and Adele Clarke's postmodern Situational Analysis [ 16 ]: Charmaz and Clarke were both students of Anselm Strauss. The fifth, emerging variant is 'Dimensional Analysis' [ 17 ] which is being developed from the work of Leonard Schaztman, who was a colleague of Strauss and Glaser in the 1960s and 1970s.

There has been some discussion in the literature about what characteristics a grounded theory study must have to be legitimately referred to as 'grounded theory' [ 18 ]. The fundamental components of a grounded theory study are set out in Table Table1. 1 . These components may appear in different combinations in other qualitative studies; a grounded theory study should have all of these. As noted, there are few examples of 'how to do' grounded theory in the literature [ 18 , 19 ]. Those that do exist have focused on Strauss and Corbin's methods [ 20 - 25 ]. An exception is Charmaz's own description of her study of chronic illness [ 26 ]; we applied this same variant in our study. In the remainder of this paper, we will show how each of the characteristics of grounded theory methodology worked in our study of dental practices.

Fundamental components of a grounded theory study

| COMPONENT | STAGE | DESCRIPTION | SOURCES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | Throughout the study | Grounded theory methodology emphasises inductive analysis. Deduction is the usual form of analytic thinking in medical research. Deduction moves from the general to the particular: it begins with pre-existing hypotheses or theories, and collects data to test those theories. In contrast, induction moves from the particular to the general: it develops new theories or hypotheses from many observations. Grounded theory particularly emphasises induction. This means that grounded theory studies tend to take a very open approach to the process being studied. The emphasis of a grounded theory study may evolve as it becomes apparent to the researchers what is important to the study participants. | [ ] p1-3, 15,16,43- 46 [ ] p2-6 [ ] p4-21 |

| Analysing immediately | Analysis and data collection | In a grounded theory study, the researchers do not wait until the data are collected before commencing analysis. In a grounded theory study, analysis must commence as soon as possible, and continue in parallel with data collection, to allow (see below). | [ ] p12,13, 301 [ ] p102 [ ] p20 |

| Coding and comparing | Analysis | Data analysis relies on - a process of breaking data down into much smaller components and labelling those components - and - comparing data with data, case with case, event with event, code with code, to understand and explain variation in the data. are eventually combined and related to one another - at this stage they are more abstract, and are referred to as or . | [ ] p80,81, 265-289 [ ] p101-115 [ ] p42-71 |

| Memo-writing (sometimes also drawing diagrams) | Analysis | The analyst writes many memos throughout the project. Memos can be about events, cases, categories, or relationships between categories. Memos are used to stimulate and record the analysts' developing thinking, including the made (see above). | [ ] p245-264,281, 282,302 [ ] p108,112 [ ] p72-95 |

| Theoretical sampling | Sampling and data collection | Theoretical sampling is central to grounded theory design. A theoretical sample is informed by . Theoretical sampling is designed to serve the developing . Analysis raises questions, suggests relationships, highlights gaps in the existing data set and reveals what the researchers do not yet know. By carefully selecting and by modifying the asked in data collection, the researchers fill gaps, clarify uncertainties, test their interpretations, and build their emerging theory. | [ ] p304, 305, 611 [ ] p45-77 [ ] p96-122 |

| Theoretical saturation | Sampling, data collection and analysis | Qualitative researchers generally seek to reach 'saturation' in their studies. Often this is interpreted as meaning that the researchers are hearing nothing new from participants. In a grounded theory study, theoretical saturation is sought. This is a subtly different form of saturation, in which all of the concepts in the substantive theory being developed are well understood and can be substantiated from the data. | [ ] p306, 281,611 [ ] p111-113 [ ] p114, 115 |

| Production of a substantive theory | Analysis and interpretation | The results of a grounded theory study are expressed as a substantive theory, that is, as a set of concepts that are related to one another in a cohesive whole. As in most science, this theory is considered to be fallible, dependent on context and never completely final. | [ ] p14,25 [ ] p21-43 [ ] p123-150 |

Study background

We used grounded theory methodology to investigate social processes in private dental practices in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. This grounded theory study builds on a previous Australian Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) called the Monitor Dental Practice Program (MPP) [ 27 ]. We know that preventive techniques can arrest early tooth decay and thus reduce the need for fillings [ 28 - 32 ]. Unfortunately, most dentists worldwide who encounter early tooth decay continue to drill it out and fill the tooth [ 33 - 37 ]. The MPP tested whether dentists could increase their use of preventive techniques. In the intervention arm, dentists were provided with a set of evidence-based preventive protocols to apply [ 38 ]; control practices provided usual care. The MPP protocols used in the RCT guided dentists to systematically apply preventive techniques to prevent new tooth decay and to arrest early stages of tooth decay in their patients, therefore reducing the need for drilling and filling. The protocols focused on (1) primary prevention of new tooth decay (tooth brushing with high concentration fluoride toothpaste and dietary advice) and (2) intensive secondary prevention through professional treatment to arrest tooth decay progress (application of fluoride varnish, supervised monitoring of dental plaque control and clinical outcomes)[ 38 ].

As the RCT unfolded, it was discovered that practices in the intervention arm were not implementing the preventive protocols uniformly. Why had the outcomes of these systematically implemented protocols been so different? This question was the starting point for our grounded theory study. We aimed to understand how the protocols had been implemented, including the conditions and consequences of variation in the process. We hoped that such understanding would help us to see how the norms of Australian private dental practice as regards to tooth decay could be moved away from drilling and filling and towards evidence-based preventive care.

Designing this grounded theory study

Figure Figure1 1 illustrates the steps taken during the project that will be described below from points A to F.

Study design . file containing a figure illustrating the study design.

A. An open beginning and research questions

Grounded theory studies are generally focused on social processes or actions: they ask about what happens and how people interact . This shows the influence of symbolic interactionism, a social psychological approach focused on the meaning of human actions [ 39 ]. Grounded theory studies begin with open questions, and researchers presume that they may know little about the meanings that drive the actions of their participants. Accordingly, we sought to learn from participants how the MPP process worked and how they made sense of it. We wanted to answer a practical social problem: how do dentists persist in drilling and filling early stages of tooth decay, when they could be applying preventive care?

We asked research questions that were open, and focused on social processes. Our initial research questions were:

• What was the process of implementing (or not-implementing) the protocols (from the perspective of dentists, practice staff, and patients)?

• How did this process vary?

B. Ethics approval and ethical issues

In our experience, medical researchers are often concerned about the ethics oversight process for such a flexible, unpredictable study design. We managed this process as follows. Initial ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Sydney. In our application, we explained grounded theory procedures, in particular the fact that they evolve. In our initial application we provided a long list of possible recruitment strategies and interview questions, as suggested by Charmaz [ 15 ]. We indicated that we would make future applications to modify our protocols. We did this as the study progressed - detailed below. Each time we reminded the committee that our study design was intended to evolve with ongoing modifications. Each modification was approved without difficulty. As in any ethical study, we ensured that participation was voluntary, that participants could withdraw at any time, and that confidentiality was protected. All responses were anonymised before analysis, and we took particular care not to reveal potentially identifying details of places, practices or clinicians.

C. Initial, Purposive Sampling (before theoretical sampling was possible)

Grounded theory studies are characterised by theoretical sampling, but this requires some data to be collected and analysed. Sampling must thus begin purposively, as in any qualitative study. Participants in the previous MPP study provided our population [ 27 ]. The MPP included 22 private dental practices in NSW, randomly allocated to either the intervention or control group. With permission of the ethics committee; we sent letters to the participants in the MPP, inviting them to participate in a further qualitative study. From those who agreed, we used the quantitative data from the MPP to select an initial sample.

Then, we selected the practice in which the most dramatic results had been achieved in the MPP study (Dental Practice 1). This was a purposive sampling strategy, to give us the best possible access to the process of successfully implementing the protocols. We interviewed all consenting staff who had been involved in the MPP (one dentist, five dental assistants). We then recruited 12 patients who had been enrolled in the MPP, based on their clinically measured risk of developing tooth decay: we selected some patients whose risk status had gotten better, some whose risk had worsened and some whose risk had stayed the same. This purposive sample was designed to provide maximum variation in patients' adoption of preventive dental care.

Initial Interviews

One hour in-depth interviews were conducted. The researcher/interviewer (AS) travelled to a rural town in NSW where interviews took place. The initial 18 participants (one dentist, five dental assistants and 12 patients) from Dental Practice 1 were interviewed in places convenient to them such as the dental practice, community centres or the participant's home.

Two initial interview schedules were designed for each group of participants: 1) dentists and dental practice staff and 2) dental patients. Interviews were semi-structured and based loosely on the research questions. The initial questions for dentists and practice staff are in Additional file 1 . Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. The research location was remote from the researcher's office, thus data collection was divided into two episodes to allow for intermittent data analysis. Dentist and practice staff interviews were done in one week. The researcher wrote memos throughout this week. The researcher then took a month for data analysis in which coding and memo-writing occurred. Then during a return visit, patient interviews were completed, again with memo-writing during the data-collection period.

D. Data Analysis

Coding and the constant comparative method.

Coding is essential to the development of a grounded theory [ 15 ]. According to Charmaz [[ 15 ], p46], 'coding is the pivotal link between collecting data and developing an emergent theory to explain these data. Through coding, you define what is happening in the data and begin to grapple with what it means'. Coding occurs in stages. In initial coding, the researcher generates as many ideas as possible inductively from early data. In focused coding, the researcher pursues a selected set of central codes throughout the entire dataset and the study. This requires decisions about which initial codes are most prevalent or important, and which contribute most to the analysis. In theoretical coding, the researcher refines the final categories in their theory and relates them to one another. Charmaz's method, like Glaser's method [ 13 ], captures actions or processes by using gerunds as codes (verbs ending in 'ing'); Charmaz also emphasises coding quickly, and keeping the codes as similar to the data as possible.

We developed our coding systems individually and through team meetings and discussions.

We have provided a worked example of coding in Table Table2. 2 . Gerunds emphasise actions and processes. Initial coding identifies many different processes. After the first few interviews, we had a large amount of data and many initial codes. This included a group of codes that captured how dentists sought out evidence when they were exposed to a complex clinical case, a new product or technique. Because this process seemed central to their practice, and because it was talked about often, we decided that seeking out evidence should become a focused code. By comparing codes against codes and data against data, we distinguished the category of "seeking out evidence" from other focused codes, such as "gathering and comparing peers' evidence to reach a conclusion", and we understood the relationships between them. Using this constant comparative method (see Table Table1), 1 ), we produced a theoretical code: "making sense of evidence and constructing knowledge". This code captured the social process that dentists went through when faced with new information or a practice challenge. This theoretical code will be the focus of a future paper.

Coding process

| Raw data | Initial coding | Focused coding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q. What did you take into account when you decided to buy this new technology? What did we... we looked at cost, we looked at reliability and we sort of, we compared a few different types, talked to some people that had them. Q. When you say you talked to some people who were they? Some dental colleagues. There's a couple of internet sites that we talked to some people... people had tried out some that didn't work very well. Q. So in terms of materials either preventive materials or restorative materials; what do you take in account when you decide which one to adopt? Well, that's a good question. I don't know. I suppose we [laughs] look at reliability. I suppose I've been looking at literature involved in it so I quite like my own little research about that, because I don't really trust the research that comes with the product and once again what other dentists are using and what they've been using and they're happy with. I'm finding the internet, some of those internet forums are actually quite good for new products. | Deciding to buy based on cost, reliability Talking to dental colleagues on internet sites Comparing their experiences Looking at literature Doing my own little research Not trusting research that comes with commercial products Talking to other dentists about their experiences | |

Memo-writing

Throughout the study, we wrote extensive case-based memos and conceptual memos. After each interview, the interviewer/researcher (AS) wrote a case-based memo reflecting on what she learned from that interview. They contained the interviewer's impressions about the participants' experiences, and the interviewer's reactions; they were also used to systematically question some of our pre-existing ideas in relation to what had been said in the interview. Table Table3 3 illustrates one of those memos. After a few interviews, the interviewer/researcher also began making and recording comparisons among these memos.

Case-based memo

| This was quite an eye opening interview in the sense that the practice manager was very direct, practical and open. In his accounts, the bottom line is that this preventive program is not profitable; dentists will do it for giving back to the community, not to earn money from it. I am so glad we had this interview; otherwise I am not sure if someone would be so up front about it. So, my question really is, is that the reason why dentists have not adopted it in other practices? And what about other patients who come here, who are not enrolled in the research program, does the dentist-in-charge treat them all as being part of the program or it was just an impression from the interview and what I saw here during my time in the practice... or will the dentist continue doing it in the next future? |

| I definitely learned that dentistry in private practice is a business, at the end of the day a target has to be achieved, and the dentist is driven by it. During the dentist's interview, there was a story about new patients being referred to the practice because the way they were treating patients now; but right now I am just not sure; I really need to check that... need to go back and ask the dentist about it, were there any referrals or not? Because this would create new revenue for the practice and the practice manager would surely be happy about it. On the other hand, it is interesting that the practice manager thinks that having a hygienist who was employed few months ago is the way to adopt the preventive program; she should implement it, freeing the dentist to do more complex work. But in reality, when I interviewed the hygienist I learned that she does not want to change to adopt the program, she is really focused on what she has been doing for a while and trust her experience a lot! So I guess, the dentist in charge might be going through a new changing process, different from what happen when the MPP protocols were first tried in this practice; this is another point to check on the next interview with the dentist. I just have this feeling that somehow the new staff (hygienist) is really important for this practice to regain and maintain profit throughout the adoption of preventive protocols but there are some personality clashes happening along the way. |

We also wrote conceptual memos about the initial codes and focused codes being developed, as described by Charmaz [ 15 ]. We used these memos to record our thinking about the meaning of codes and to record our thinking about how and when processes occurred, how they changed, and what their consequences were. In these memos, we made comparisons between data, cases and codes in order to find similarities and differences, and raised questions to be answered in continuing interviews. Table Table4 4 illustrates a conceptual memo.

Conceptual memo

| In these dental practices the adaptation to preventive protocols was all about believing in this new approach to manage dental caries and in themselves as professionals. New concepts were embraced and slowly incorporated into practice. Embracing new concepts/paradigms/systems and abandoning old ones was quite evident during this process (old concepts = dentistry restorative model; new concepts = non-surgical approach). This evolving process involved feelings such as anxiety, doubt, determination, confidence, and reassurance. The modification of practices was possible when dentists-in-charge felt that perhaps there was something else that would be worth doing; something that might be a little different from what was done so far. The responsibility to offer the best available treatment might have triggered this reasoning. However, there are other factors that play an important role during this process such as dentist's personal features, preconceived notions, dental practice environment, and how dentists combine patients' needs and expectations while making treatment decisions. Finding the balance between preventive non-surgical treatment (curing of disease) and restorative treatment (making up for lost tissues) is an every moment challenge in a profitable dental practice. Regaining profit, reassessing team work and surgery logistics, and mastering the scheduling art to maximize financial and clinical outcomes were important practical issues tackled in some of these practices during this process. |

| These participants talked about learning and adapting new concepts to their practices and finally never going back the way it was before. This process brought positive changes to participants' daily activities. Empowerment of practice staff made them start to enjoy more their daily work (they were recognized by patients as someone who was truly interested in delivering the best treatment for them). Team members realized that there were many benefits to patients and to staff members in implementing this program, such as, professional development, offering the best care for each patient and job satisfaction. |

At the end of our data collection and analysis from Dental Practice 1, we had developed a tentative model of the process of implementing the protocols, from the perspective of dentists, dental practice staff and patients. This was expressed in both diagrams and memos, was built around a core set of focused codes, and illustrated relationships between them.

E. Theoretical sampling, ongoing data analysis and alteration of interview route

We have already described our initial purposive sampling. After our initial data collection and analysis, we used theoretical sampling (see Table Table1) 1 ) to determine who to sample next and what questions to ask during interviews. We submitted Ethics Modification applications for changes in our question routes, and had no difficulty with approval. We will describe how the interview questions for dentists and dental practice staff evolved, and how we selected new participants to allow development of our substantive theory. The patients' interview schedule and theoretical sampling followed similar procedures.

Evolution of theoretical sampling and interview questions

We now had a detailed provisional model of the successful process implemented in Dental Practice 1. Important core focused codes were identified, including practical/financial, historical and philosophical dimensions of the process. However, we did not yet understand how the process might vary or go wrong, as implementation in the first practice we studied had been described as seamless and beneficial for everyone. Because our aim was to understand the process of implementing the protocols, including the conditions and consequences of variation in the process, we needed to understand how implementation might fail. For this reason, we theoretically sampled participants from Dental Practice 2, where uptake of the MPP protocols had been very limited according to data from the RCT trial.

We also changed our interview questions based on the analysis we had already done (see Additional file 2 ). In our analysis of data from Dental Practice 1, we had learned that "effectiveness" of treatments and "evidence" both had a range of meanings. We also learned that new technologies - in particular digital x-rays and intra-oral cameras - had been unexpectedly important to the process of implementing the protocols. For this reason, we added new questions for the interviews in Dental Practice 2 to directly investigate "effectiveness", "evidence" and how dentists took up new technologies in their practice.

Then, in Dental Practice 2 we learned more about the barriers dentists and practice staff encountered during the process of implementing the MPP protocols. We confirmed and enriched our understanding of dentists' processes for adopting technology and producing knowledge, dealing with complex cases and we further clarified the concept of evidence. However there was a new, important, unexpected finding in Dental Practice 2. Dentists talked about "unreliable" patients - that is, patients who were too unreliable to have preventive dental care offered to them. This seemed to be a potentially important explanation for non-implementation of the protocols. We modified our interview schedule again to include questions about this concept (see Additional file 3 ) leading to another round of ethics approvals. We also returned to Practice 1 to ask participants about the idea of an "unreliable" patient.

Dentists' construction of the "unreliable" patient during interviews also prompted us to theoretically sample for "unreliable" and "reliable" patients in the following round of patients' interviews. The patient question route was also modified by the analysis of the dentists' and practice staff data. We wanted to compare dentists' perspectives with the perspectives of the patients themselves. Dentists were asked to select "reliable" and "unreliable" patients to be interviewed. Patients were asked questions about what kind of services dentists should provide and what patients valued when coming to the dentist. We found that these patients (10 reliable and 7 unreliable) talked in very similar ways about dental care. This finding suggested to us that some deeply-held assumptions within the dental profession may not be shared by dental patients.

At this point, we decided to theoretically sample dental practices from the non-intervention arm of the MPP study. This is an example of the 'openness' of a grounded theory study potentially subtly shifting the focus of the study. Our analysis had shifted our focus: rather than simply studying the process of implementing the evidence-based preventive protocols, we were studying the process of doing prevention in private dental practice. All participants seemed to be revealing deeply held perspectives shared in the dental profession, whether or not they were providing dental care as outlined in the MPP protocols. So, by sampling dentists from both intervention and control group from the previous MPP study, we aimed to confirm or disconfirm the broader reach of our emerging theory and to complete inductive development of key concepts. Theoretical sampling added 12 face to face interviews and 10 telephone interviews to the data. A total of 40 participants between the ages of 18 and 65 were recruited. Telephone interviews were of comparable length, content and quality to face to face interviews, as reported elsewhere in the literature [ 40 ].

F. Mapping concepts, theoretical memo writing and further refining of concepts

After theoretical sampling, we could begin coding theoretically. We fleshed out each major focused code, examining the situations in which they appeared, when they changed and the relationship among them. At time of writing, we have reached theoretical saturation (see Table Table1). 1 ). We have been able to determine this in several ways. As we have become increasingly certain about our central focused codes, we have re-examined the data to find all available insights regarding those codes. We have drawn diagrams and written memos. We have looked rigorously for events or accounts not explained by the emerging theory so as to develop it further to explain all of the data. Our theory, which is expressed as a set of concepts that are related to one another in a cohesive way, now accounts adequately for all the data we have collected. We have presented the developing theory to specialist dental audiences and to the participants, and have found that it was accepted by and resonated with these audiences.

We have used these procedures to construct a detailed, multi-faceted model of the process of incorporating prevention into private general dental practice. This model includes relationships among concepts, consequences of the process, and variations in the process. A concrete example of one of our final key concepts is the process of "adapting to" prevention. More commonly in the literature writers speak of adopting, implementing or translating evidence-based preventive protocols into practice. Through our analysis, we concluded that what was required was 'adapting to' those protocols in practice. Some dental practices underwent a slow process of adapting evidence-based guidance to their existing practice logistics. Successful adaptation was contingent upon whether (1) the dentist-in-charge brought the whole dental team together - including other dentists - and got everyone interested and actively participating during preventive activities; (2) whether the physical environment of the practice was re-organised around preventive activities, (3) whether the dental team was able to devise new and efficient routines to accommodate preventive activities, and (4) whether the fee schedule was amended to cover the delivery of preventive services, which hitherto was considered as "unproductive time".

Adaptation occurred over time and involved practical, historical and philosophical aspects of dental care. Participants transitioned from their initial state - selling restorative care - through an intermediary stage - learning by doing and educating patients about the importance of preventive care - and finally to a stage where they were offering patients more than just restorative care. These are examples of ways in which participants did not simply adopt protocols in a simple way, but needed to adapt the protocols and their own routines as they moved toward more preventive practice.

The quality of this grounded theory study

There are a number of important assurances of quality in keeping with grounded theory procedures and general principles of qualitative research. The following points describe what was crucial for this study to achieve quality.

During data collection

1. All interviews were digitally recorded, professionally transcribed in detail and the transcripts checked against the recordings.

2. We analysed the interview transcripts as soon as possible after each round of interviews in each dental practice sampled as shown on Figure Figure1. 1 . This allowed the process of theoretical sampling to occur.

3. Writing case-based memos right after each interview while being in the field allowed the researcher/interviewer to capture initial ideas and make comparisons between participants' accounts. These memos assisted the researcher to make comparison among her reflections, which enriched data analysis and guided further data collection.

4. Having the opportunity to contact participants after interviews to clarify concepts and to interview some participants more than once contributed to the refinement of theoretical concepts, thus forming part of theoretical sampling.

5. The decision to include phone interviews due to participants' preference worked very well in this study. Phone interviews had similar length and depth compared to the face to face interviews, but allowed for a greater range of participation.

During data analysis

1. Detailed analysis records were kept; which made it possible to write this explanatory paper.

2. The use of the constant comparative method enabled the analysis to produce not just a description but a model, in which more abstract concepts were related and a social process was explained.

3. All researchers supported analysis activities; a regular meeting of the research team was convened to discuss and contextualize emerging interpretations, introducing a wide range of disciplinary perspectives.

Answering our research questions

We developed a detailed model of the process of adapting preventive protocols into dental practice, and analysed the variation in this process in different dental practices. Transferring evidence-based preventive protocols into these dental practices entailed a slow process of adapting the evidence to the existing practices logistics. Important practical, philosophical and historical elements as well as barriers and facilitators were present during a complex adaptation process. Time was needed to allow dentists and practice staff to go through this process of slowly adapting their practices to this new way of working. Patients also needed time to incorporate home care activities and more frequent visits to dentists into their daily routines. Despite being able to adapt or not, all dentists trusted the concrete clinical evidence that they have produced, that is, seeing results in their patients mouths made them believe in a specific treatment approach.

Concluding remarks

This paper provides a detailed explanation of how a study evolved using grounded theory methodology (GTM), one of the most commonly used methodologies in qualitative health and medical research [[ 8 ], p47]. In 2007, Bryant and Charmaz argued:

'Use of GTM, at least as much as any other research method, only develops with experience. Hence the failure of all those attempts to provide clear, mechanistic rules for GTM: there is no 'GTM for dummies'. GTM is based around heuristics and guidelines rather than rules and prescriptions. Moreover, researchers need to be familiar with GTM, in all its major forms, in order to be able to understand how they might adapt it in use or revise it into new forms and variations.' [[ 8 ], p17].

Our detailed explanation of our experience in this grounded theory study is intended to provide, vicariously, the kind of 'experience' that might help other qualitative researchers in medicine and health to apply and benefit from grounded theory methodology in their studies. We hope that our explanation will assist others to avoid using grounded theory as an 'approving bumper sticker' [ 10 ], and instead use it as a resource that can greatly improve the quality and outcome of a qualitative study.

Abbreviations

GTM: grounded theory methods; MPP: Monitor Dental Practice Program; NSW: New South Wales; RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to conception and design of this study. AS carried out data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. SMC made substantial contribution during data collection, analysis and data interpretation. AS, SMC, RWE, and AB have been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/11/128/prepub

Supplementary Material

Initial interview schedule for dentists and dental practice staff . file containing initial interview schedule for dentists and dental practice staff.

Questions added to the initial interview schedule for dentists and dental practice staff . file containing questions added to the initial interview schedule

Questions added to the modified interview schedule for dentists and dental practice staff . file containing questions added to the modified interview schedule

Acknowledgements

We thank dentists, dental practice staff and patients for their invaluable contributions to the study. We thank Emeritus Professor Miles Little for his time and wise comments during the project.

The authors received financial support for the research from the following funding agencies: University of Sydney Postgraduate Award 2009; The Oral Health Foundation, University of Sydney; Dental Board New South Wales; Australian Dental Research Foundation; National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant 632715.

- Qualitative Health Research Journal. http://qhr.sagepub.com/ website accessed on 10 June 2011.

- Qualitative Health Research conference of The International Institute for Qualitative Methodology. http://www.iiqm.ualberta.ca/en/Conferences/QualitativeHealthResearch.aspx website accessed on 10 June 2011.

- The Global Congress for Qualitative Health Research. http://www.gcqhr.com/ website accessed on 10 June 2011. [ PubMed ]

- Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research: observational methods in health care settings. BMJ. 1995; 311 :182. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuper A, Reeves S, Levinson W. Qualitative research: an introduction to reading and appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008; 337 :a288. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a288. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Tri-Council Policy Statemen. Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans . 1998. http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/english/policystatement/introduction.cfm website accessed on 13 September 2011.

- The Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/e35syn.htm website accessed on 10 June 2011.

- Bryant A, Charmaz K, (eds.) Handbook of Grounded Theory. London: Sage; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Walker D, Myrick F. Grounded theory: an exploration of process and procedure. Qual Health Res. 2006; 16 :547–559. doi: 10.1177/1049732305285972. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbour R. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ. 2001; 322 :1115–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dixon-Woods M, Booth A, Sutton AJ. Synthesizing qualitative research: a review of published reports. Qual Res. 2007; 7 (3):375–422. doi: 10.1177/1468794107078517. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glaser BG. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Emergence vs Forcing. Mill Valley CA, USA: Sociology Press; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Corbin J, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clarke AE. Situational Analysis. Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowers B, Schatzman L. In: Developing Grounded Theory: The Second Generation. Morse JM, Stern PN, Corbin J, Bowers B, Charmaz K, Clarke AE, editor. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Left Coast Press; 2009. Dimensional Analysis; pp. 86–125. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morse JM, Stern PN, Corbin J, Bowers B, Charmaz K, Clarke AE, (eds.) Developing Grounded Theory: The Second Generation. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Left Coast Press; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter SM. In: Researching Practice: A Discourse on Qualitative Methodologies. Higgs J, Cherry N, Macklin R, Ajjawi R, editor. Vol. 2. Practice, Education, Work and Society Series. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers; 2010. Enacting Internal Coherence as a Path to Quality in Qualitative Inquiry; pp. 143–152. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wasserman JA, Clair JM, Wilson KL. Problematics of grounded theory: innovations for developing an increasingly rigorous qualitative method. Qual Res. 2009; 9 :355–381. doi: 10.1177/1468794109106605. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scott JW. Relating categories in grounded theory analysis: using a conditional relationship guide and reflective coding matrix. The Qualitative Report. 2004; 9 (1):113–126. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sarker S, Lau F, Sahay S. Using an adapted grounded theory approach for inductive theory about virtual team development. Data Base Adv Inf Sy. 2001; 32 (1):38–56. [ Google Scholar ]