- Find My GCO

- IACUC applications (Cayuse Animal Management System)

- IBC Applications (eMUA)

- IRB Applications (RASS-IRB) External

- Institutional Profile & DUNS

- Rates and budgets

- Report external interests (COI)

- Join List Servs

- Ask EHS External

- Research Development Services

- Cornell Data Services External

- Find Your Next Funding Opportunity

- Travel Registry External

- RASS (Formerly Form 10 and NFA) External

- International research activities External

- Register for Federal and Non-Federal Systems

- Disclose Foreign Collaborations and Support

- Web Financials (WebFin2) External

- PI Dashboard External

- Research metrics & executive dashboards

- Research Financials (formerly RA Dashboard) External

- Subawards in a Proposal

- Proposal Development, Review, and Submission

- Planning for Animals, Human Participants, r/sNA, Hazardous Materials, Radiation

- Budgets, Costs, and Rates

- Collaborate with Weill Cornell Medicine

- Award Negotiation and Finalization

- Travel and International Activities

- Project Finances

- Project Modifications

- Research Project Staffing

- Get Confidential Info, Data, Equipment, or Materials

- Managing Subawards

- Animals, Human Participants, r/sNA, Hazardous Materials, Radiation

- Project Closeout Financials

- Project Closeout

- End a Project Early

- Protecting an Invention, Creation, Discovery

- Entrepreneurial and Startup Company Resources

- Gateway to Partnership Program

- Engaging with Industry

- Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR)

- Export Controls

- Research with Human Participants

- Research Security

- Work with Live Vertebrate Animals

- Research Safety

- Regulated Biological Materials in Research

- Financial Management

- Conflicts of Interest

- Search

IRB Consent Form Templates

A collection of informed consent, assent, and debriefing templates that can be used for your human participant research study.

General Consent Form Templates

Social and Behavioral Research Projects (last updated 03/16/2023)

Biomedical Research Projects (last updated 07/18/2022)

Consent Form Templates for Specific Biomedical Procedures

MRI and fMRI

Blood Collection by Finger Stick

Blood Collection by Venipuncture

Oral Consent Template

Guidance for Protocols Involving Oral Consent

Debriefing Template

Guidance and Template for Debriefing Participants

Studies Involving Children (Assent/Permission Forms)

Parent-Guardian Permission for Studies Involving Children

Sample Parental Notification Form

Sample Child Assent Form

Performance Release for Minors

Performance Releases

Performance Release for Adults

Why use it?

This template includes key information that you should provide to get consent from people participating in your research interviews or focus groups. Before you use this template, check out the getting consent guide for more information.

Interview/Focus group consent form

I ….............................................................(name), being over the age of 18 years, hereby consent to participate as requested in the [focus group/interview] for the research project held on …………………………………… (date).

- Details of the focus group have been explained to my satisfaction.

- I agree to audio recording of my information and participation.

- I may not directly benefit from taking part in this research.

- I am free to withdraw from the project at any time and am free to decline to answer particular questions.

- While the information gained in this study will be published as explained, I will not be identified and individual information will remain confidential.

- Whether I participate or not, or withdraw after participating, will have no effect on any treatment or service that is being provided to me.

- I may ask that the recording/observation be stopped at any time, and that I may withdraw at any time from the session or the research without disadvantage.

- I understand that I can contact either the researcher or [insert organisation] with questions about this research via the contact details below.

Name, Role – Organisation

Email and phone number

Participant’s signature: ………………………………………

Date: ……………………………………………………………………

Date of birth: ………………………………………………………

As the nation’s largest public research university, the Office of the Vice President for Research (OVPR) aims to catalyze, support and safeguard U-M research and scholarship activity.

The Office of the Vice President for Research oversees a variety of interdisciplinary units that collaborate with faculty, staff, students and external partners to catalyze, support and safeguard research and scholarship activity.

ORSP manages pre-award and some post-award research activity for U-M. We review contracts for sponsored projects applying regulatory, statutory and organizational knowledge to balance the university's mission, the sponsor's objectives, and the investigator's intellectual pursuits.

Ethics and compliance in research covers a broad range of activity from general guidelines about conducting research responsibly to specific regulations governing a type of research (e.g., human subjects research, export controls, conflict of interest).

eResearch is U-M's site for electronic research administration. Access: Regulatory Management (for IRB or IBC rDNA applications); Proposal Management (eRPM) for the e-routing, approval, and submission of proposals (PAFs) and Unfunded Agreements (UFAs) to external entities); and Animal Management (for IACUC protocols and ULAM).

Sponsored Programs manages the post-award financial activities of U-M's research enterprise and other sponsored activities to ensure compliance with applicable federal, state, and local laws as well as sponsor regulations. The Office of Contract Administration (OCA) is also part of the Office of Finance - Sponsored Programs.

Ethics & Compliance

- eResearch IRB NextGen Project

- Class Assignments & IRB Approval

- Operations Manual (OM)

- Authorization Agreement Process

- ORCR Policies and Procedures

- Self-Assessment Tools

- Resources and Web Links

- Single IRB-of-Record (sIRB) Process

- Certificate of Confidentiality Process

- HRPP Education Resources

- How to Register a Clinical Trial

- Maintaining and Updating ClinicalTrial.gov Records

- How to Report Clinical Trial Results

- Research Study Participation - FAQ

- International Research

- Coordinated Services & Practices (CSP)

- Collaborative Research: IRB-HSBS sIRB Process

- Data Security Guidelines

- Research Incentive Guidelines

- Routine fMRI Study Guidelines

- IRB-HSBS Website Directory and Guidance

- Waivers of Informed Consent Guidelines

- IRB Review Process

- IRB Amendment Process

- Continuing Review Process

- Incident Reporting (AE/ORIO)

- IRB Repository Application

- IRB-HSBS Education

- Newsletter Archive

You are here

- Human Subjects

- IRB Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences (HSBS)

Informed Consent Guidelines & Templates

U-m hrpp informed consent information.

See the HRPP Operations Manual, Part 3, Section III, 6 e .

The human subjects in your project must participate willingly , having been adequately informed about the research.

- If the human subjects are part of a vulnerable population (e.g., prisoners, cognitively impaired individuals, or children), special protections are required.

- If the human subjects are children , in most cases you must first obtain the permission of parents in addition to the consent of the children.

Contact the IRB Office for more information .

See the Waiver Guidelines for information about, and policies regarding, waivers for informed consent or informed consent documentation.

See the updated Basic Informed Consent Elements document for a list of 2018 Common Rule basic and additional elements.

Informed Consent Process

Informed consent is the process of telling potential research participants about the key elements of a research study and what their participation will involve. The informed consent process is one of the central components of the ethical conduct of research with human subjects. The consent process typically includes providing a written consent document containing the required information (i.e., elements of informed consent) and the presentation of that information to prospective participants.

In most cases, investigators are expected to obtain a signature from the participant on a written informed consent document (i.e., to document the consent to participate) unless the IRB has waived the consent requirement or documentation (signature) requirement .

- Projects which collect biospecimens for genetic analysis must obtain documented (signed) informed consent.

- It is an ethical best practice to include an informed consent process for most exempt research . IRB-HSBS reviews, as applicable, the IRB application for exempt research, but not the informed consent document itself. A suggested consent template for exempt research can be found below under the References and Resources section. A companion protocol template for exempt research may be found in the feature box, Related Information (top right).

Informed consent documents

An informed consent document is typically used to provide subjects with the information they need to make a decision to volunteer for a research study. Federal regulations ( 45 CFR 46.116 ) provide the framework for the type of information (i.e., the "elements") that must be included as part of the consent process. New with the revised 2018 Common Rule is the requirement that the consent document begin with a "concise and focused" presentation of key information that will help potential participants understand why they might or might not want to be a part of a research study.

Key Information Elements

The image below displays the five elements identified in the preamble to the revised Final Rule as suggested key information.

Note: Element number 5 (alternative procedures) applies primarily to clinical research.

General Information & Tips for Preparing a Consent Document

Reading level.

Informed consent documents should be written in plain language at a level appropriate to the subject population, generally at an 8th grade reading level . A best practice is to have a colleague or friend read the informed consent document for comprehension before submission with the IRB application. Always:

For guidance on using plain language, examples, and more, visit: http://www.plainlanguage.gov/

- Tailor the document to the subject population.

- Avoid technical jargon or overly complex terms.

- Use straightforward language that is understandable.

Writing tips

The informed consent document should succinctly describe the research as it has been presented in the IRB application.

- Use the second (you) or third person (he/she) to present the study details. Avoid use of the first person (I).

- Include a statement of agreement at the conclusion of the informed consent document.

- The consent doucment must be consistent with what is described in the IRB application.

Document Formating for Uploading into eResearch

- Remove "track changes" or inserted comments from the consent documentation prior to uploading the document into the IRB application (Section 10-1) for review.

- Use a consistent, clearly identified file naming convention for multiple consent/assent documents.

Informed Consent Templates

IRB-HSBS strongly recommends that investigators use one of the informed consent templates developed to include the required consent elements (per 45 CFR 46.116 ), as well as other required regulatory and institutional language. The templates listed below include the new consent elements outlined in the 2018 Common Rule.

References and Resources

PDF. Lists the basic and additional elements required for inclusion or to be included, as appropriate to the research, in the informed consent documentation, along with the citiation number [e.g., _0116(b)(1)] within the revised Common Rule. New elements associated with the 2018 Common Rule are indicated in bold text.

Strongly recommended for studies that involve the collection of biospecimens and/or genetic or genomic analysis, particularly federally sponsored clinical trials that are required to post a consent document on a public website. Last updated: 04/10/2024.

Informed Consent documents are not reviewed by the IRB for Exempt projects. However, researchers are ethically bound to conduct a consent process with subjects. This template is suggested for use with Exempt projects. Last updated 4/17/24

(Word) Blank template with 2018 revised Common Rule key information and other required informed consent elements represented as section headers; includes instructions and recommended language. It is strongly advised that you modify this template to draft a project-specific informed consent document for your study for IRB review and approval. Last updated: 04/10/2024

(Word) General outline to create and post a flyer seeking participation in a human subjects study. Includes instructions.

(Word) Two sample letters for site approval cooperation between U-M and other institutions, organizations, etc. Letters of cooperation must be on U-M letterhead and signed by an appropriate official. These letters are uploaded into the Performance Site section of the eResearch IRB application.

For use by U-M Dearborn faculty, staff, and students conducting non-exempt human subjects research using subject pools. Last updated 4/10/24

For use by U-M Dearborn faculty, staff, and students conducting exempt human subjects research using subject pools

Researchers who will conduct data collection that is subject to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) must use this template in tandem with a general consent for participation template/document.

- Child assent ages 3-6

- Child assent 7-11

- Parent permission

- Brief protocol for exempt research including data management and security questionnaire

- Child assent 12-14

- Introductory psychology subject pool general consent template

- Introductory psychology subject pool exempt consent template

IRB-Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences (IRB-HSBS)

Phone: (734) 936-0933 Fax: (734) 936-1852 [email protected]

- Human Subjects Protections

- Privacy Policy

Home » Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates and Examples

Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates and Examples

Table of Contents

Informed Consent in Research

Informed consent is a process of communication between a researcher and a potential participant in which the researcher provides adequate information about the study, its risks and benefits, and the participant voluntarily agrees to participate. It is a cornerstone of ethical research involving human subjects and is intended to protect the rights and welfare of participants.

Types of Informed Consent in Research

There are different types of informed consent in research , which may vary depending on the nature of the study, the type of participants, and the context. Some of the common types of informed consent in research include:

Written Consent

This is the most common type of informed consent, where participants are provided with a written document that explains the study and its requirements. The document typically includes information about the purpose of the study, procedures involved, risks and benefits, confidentiality, and participant rights. Participants are asked to sign the document as an indication of their willingness to participate.

Oral Consent

In some cases, oral consent may be used when a written document is not practical or feasible. Oral consent involves explaining the study and its requirements to participants verbally and obtaining their consent. This method may be used for studies with illiterate or visually impaired participants or when conducting research remotely.

Implied Consent

Implied consent is used in studies where participants’ actions are taken as an indication of their willingness to participate. For example, a participant may be considered to have given implied consent if they show up for a scheduled appointment for the study.

Opt-out Consent

This method is used when participants are given the opportunity to decline participation in a study. Participants are provided with information about the study and are given the option to opt-out if they do not wish to participate. This method is commonly used in population-based studies or surveys.

Assent is used in studies involving minors or participants who are unable to provide informed consent due to cognitive impairment or disability. Assent involves obtaining the agreement of the participant to participate in the study, along with the consent of a legally authorized representative.

Informed Consent Format in Research

Here’s a basic format for informed consent that can be customized for specific research studies:

- Introduction : Begin by introducing yourself and the purpose of the study. Clearly state that participation is voluntary and that participants can withdraw at any time without penalty.

- Study Overview : Provide a brief overview of the study, including its purpose, methods, and expected outcomes.

- Procedures : Describe the procedures involved in the study in clear, concise language. Include information about the types of data that will be collected, how they will be collected, and how long the study will take.

- Risks and Benefits : Outline the potential risks and benefits of participating in the study. Be honest and upfront about any discomfort, inconvenience, or potential harm that may be involved, as well as any potential benefits.

- Confidentiality and Privacy : Explain how participant data will be collected, stored, and used, and what measures will be taken to ensure confidentiality and privacy.

- Voluntary Participation: Emphasize that participation is voluntary and that participants can withdraw at any time without penalty. Explain how to withdraw from the study and who to contact if participants have questions or concerns.

- Compensation and Incentives: If applicable, explain any compensation or incentives that will be offered to participants for their participation.

- Contact Information: Provide contact information for the researcher or a representative from the research team who can answer questions and address concerns.

- Signature : Ask participants to sign and date the consent form to indicate their voluntary agreement to participate in the study.

Informed Consent Templates in Research

Here is an example of an informed consent template that can be used in research studies:

Introduction

You are being invited to participate in a research study. Before you decide whether or not to participate, it is important for you to understand why the research is being done, what your participation will involve, and what risks and benefits may be associated with your participation.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is [insert purpose of study].

If you agree to participate, you will be asked to [insert procedures involved in the study].

Risks and Benefits

There are several potential risks and benefits associated with participation in this study. Some of the risks include [insert potential risks of participation]. Some of the benefits include [insert potential benefits of participation].

Confidentiality

Your participation in this study will be kept confidential to the extent allowed by law. All data collected during the study will be stored in a secure location and only accessed by authorized personnel. Your name and other identifying information will not be included in any reports or publications resulting from this study.

Voluntary Participation

Your participation in this study is completely voluntary. You have the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. If you choose not to participate or if you withdraw from the study, there will be no negative consequences.

Contact Information

If you have any questions or concerns about the study, you can contact the investigator(s) at [insert contact information]. If you have questions about your rights as a research participant, you may contact [insert name of institutional review board and contact information].

Statement of Consent

By signing below, you acknowledge that you have read and understood the information provided in this consent form and that you freely and voluntarily consent to participate in this study.

Participant Signature: _____________________________________ Date: _____________

Investigator Signature: ____________________________________ Date: _____________

Examples of Informed Consent in Research

Here’s an example of informed consent in research:

Title : The Effects of Yoga on Stress and anxiety levels in college students

Introduction :

We are conducting a research study to investigate the effects of yoga on stress and anxiety levels in college students. We are inviting you to participate in this study.

If you agree to participate, you will be asked to attend four yoga classes per week for six weeks. Before and after the six-week period, you will be asked to complete surveys about your stress and anxiety levels. Additionally, we will measure your heart rate variability at the beginning and end of the six-week period.

Risks and Benefits:

There are no known risks associated with participating in this study. However, the benefits of practicing yoga may include decreased stress and anxiety levels, increased flexibility and strength, and improved overall well-being.

Confidentiality:

All information collected during this study will be kept strictly confidential. Your name will not be used in any reports or publications resulting from this study.

Voluntary Participation:

Participation in this study is completely voluntary. You are free to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

Contact Information:

If you have any questions or concerns about this study, you may contact the principal investigator at (phone number/email address).

By signing this form, I acknowledge that I have read and understood the above information and agree to participate in this study.

Participant Signature: ___________________________

Date: ___________________________

Researcher Signature: ___________________________

Importance of Informed Consent in Research

Here are some reasons why informed consent is important in research:

- Protection of participants’ rights : Informed consent ensures that participants understand the nature and purpose of the research, the risks and benefits of participating, and their rights as participants. It empowers them to make an informed decision about whether to participate or not.

- Ethical responsibility : Researchers have an ethical responsibility to respect the autonomy of participants and to protect them from harm. Informed consent is a crucial way to uphold these principles.

- Legality : Informed consent is a legal requirement in most countries. It is necessary to protect researchers from legal liability and to ensure that research is conducted in accordance with ethical standards.

- Trust : Informed consent helps build trust between researchers and participants. When participants understand the research process and their role in it, they are more likely to trust the researchers and the study.

- Quality of research : Informed consent ensures that participants are fully informed about the research and its purpose, which can lead to more accurate and reliable data. This, in turn, can improve the quality of research outcomes.

Purpose of Informed Consent in Research

Informed consent is a critical component of research ethics, and it serves several important purposes, including:

- Respect for autonomy: Informed consent respects an individual’s right to make decisions about their own health and well-being. It recognizes that individuals have the right to choose whether or not to participate in research, based on their own values, beliefs, and preferences.

- Protection of participants : Informed consent helps protect research participants from potential harm or risks that may arise from their involvement in a study. By providing participants with information about the study, its risks and benefits, and their rights, they are able to make an informed decision about whether to participate.

- Transparency: Informed consent promotes transparency in the research process. It ensures that participants are fully informed about the research, including its purpose, methods, and potential outcomes, which helps to build trust between researchers and participants.

- Legal and ethical requirements: Informed consent is a legal and ethical requirement in most research studies. It ensures that researchers obtain voluntary and informed agreement from participants to participate in the study, which helps to protect the rights and welfare of research participants.

Advantages of Informed Consent in Research

The advantages of informed consent in research are numerous, and some of the most significant benefits include:

- Protecting participants’ autonomy: Informed consent allows participants to exercise their right to self-determination and make decisions about whether to participate in a study or not. It also ensures that participants are fully informed about the risks, benefits, and implications of participating in the study.

- Promoting transparency and trust: Informed consent helps build trust between researchers and participants by providing clear and accurate information about the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential outcomes. This transparency promotes open communication and a positive research experience for all parties involved.

- Reducing the risk of harm: Informed consent ensures that participants are fully aware of any potential risks or side effects associated with the study. This knowledge enables them to make informed decisions about their participation and reduces the likelihood of harm or negative consequences.

- Ensuring ethical standards are met : Informed consent is a fundamental ethical requirement for conducting research involving human participants. By obtaining informed consent, researchers demonstrate their commitment to upholding ethical principles and standards in their research practices.

- Facilitating future research : Informed consent enables researchers to collect high-quality data that can be used for future research purposes. It also allows participants to make an informed decision about whether they are willing to participate in future studies.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing...

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and...

Research Approach – Types Methods and Examples

The Compass for SBC

Helping you Implement Effective Social and Behavior Change Projects

CAPACITY STRENGTHENING TOOL

Home > All Tools > Informed Consent Form Template for Qualitative Studies

More Resources

Informed consent form template for qualitative studies.

This template is for research interventions that use questionnaires, in-depth interviews or focus group discussions. The form consists of two parts: the information sheet and the consent certificate

Last modified: April 13, 2020

Language: English

- Social Media Use Among Most At Risk Populations in Jamaica

Share this Article

Informed Consent and Consent Forms for Research Participants

Informed consent is a communication process by which researchers reach agreement with people about whether they wish to participate in research. Confusing informed consent with a signed consent form may violate the ethical intent of informed consent, which is to communicate clearly and respectfully, to foster trust, comprehension, and good decision making, and to ensure that participation is voluntary.

Consent forms are often written in “legalese” and are long, complex, and often inappropriate to the culture or language of the potential subject, insulting, and virtually impossible for most people to comprehend. They convey to some the impression that signing such a formal-looking document commits them to participation. Among subjects who willingly sign documents, most sign the consent form without reading it.

How has this come to pass? Early concern with ethics of human research was about biomedical research and focused on the necessity of obtaining informed consent. Over the decades, the elements of informed consent have grown in number, as has the idea that informed consent is a form that is to be signed by the subject. According to the Federal Regulation of Human Research 46.117(a):

Except as provided in paragraph (c) of this section, informed consent shall be documented by the use of a written consent form approved by the IRB and signed by the subject or the subject’s legally authorized representative. A copy shall be given to the person signing the form.

However, many researchers and the Institutional Review Boards that govern their research fail to recognize that 46.117(c) provides for a waiver of signed consent forms:

(c) An IRB may waive the requirement for the investigator to obtain a signed consent form for some or all subjects if it finds either: (1) That the only record linking the subject and the research would be the consent document and the principal risk would be potential harm resulting from a breach of confidentiality. Each subject will be asked whether the subject wants documentation linking the subject with the research, and the subject’s wishes will govern, or (2) That the research presents no more than minimal risk of harm to subjects and involves no procedures for which written consent is normally required outside of the research context.

The reason for obtaining a signed consent form has always been much more to protect the researcher and the institution than to serve the interests of the research subject. In case the subject claims later that consent was inadequate or omitted, the researcher can counter by showing the form. Recently, the Office of Human Research Protection has imposed highly publicized and costly sanctions against a few research institutions. Understandably, IRBs and research administrators consider it in their self-interest to make highly conservative decisions. Since IRBs must take steps to justify waiving documentation of informed consent by deeming the research to be minimal risk, many consider it safer not to do so, fearing that such an action might leave them open to questions by the OHRP. Thus, the reason for obtaining a signed consent form is typically to protect the institution, not the subject. Researchers, science, institutions, subjects, and IRBs would all be better off if they made intelligent interpretations of the requirements of the Common Rule.

The Social and Behavioral Sciences Working Group has made various recommendations based on the Common Rule, designed to guide social and behavioral researchers and IRBs out of such conundrums. The authors, both members of the Working Group, developed recommendations concerning informed consent, some of which are summarized here:

1. Informed consent should take the form of an open, easily understood communication process. Typically, this means a friendly verbal exchange between researcher and subject, with a written summary of the information for the subject to keep, as appropriate. (The copy for the subject to keep would be inappropriate if the written record of the subject’s participation could be damaging to the subject, as when the research is about domestic violence, or illegal behavior). Both the verbal and written discussion should be brief, and simply phrased at such a level that all of the subjects can understand it.

2. Subjects must receive enough easily understood, accurate information to judge whether the risk or inconvenience involved is at a level they can accept. The responsibility rests with the investigator to describe any risks accurately and understandably. There are many kinds of minor or everyday risks or inconveniences that most persons would gladly undertake if it were their choice to do so, but which they would not wish to have imposed upon them unilaterally. However, some may make a rational decision that the experience would be too stressful, risky, or unpleasant for some idiosyncratic reason that applies to them and not to other subjects.

3. Especially when the research procedure is long and complex, the researcher must make it quite clear that the subject is free to ask questions at any time. Informed consent, as a conversation (not a form), needs to be available throughout the research, as subjects do not necessarily develop questions or concerns about their participation until they are well into the research experience. For example, a discussion of confidentiality may not capture subjects’ attention or comprehension until they are asked some quite personal questions in the ensuing research experience.

4. When subjects can readily refuse to participate by hanging up the phone or tossing out a mailed survey, the informed consent can be extremely brief (a sentence or two). Courtesy and professionalism require that the identity of the researcher and research institution be mentioned, along with the nature and purpose of the research. However, if there are no risks, benefits, or confidentiality issues involved, these topics and the right to refuse to participate need not be mentioned, as such details would be gratuitous and might decrease participation by implying greater risk that actually exists. If the researcher has any connection with the institution at which the subjects receive health care or other essential services, it is necessary to mention the right of the research subject to refuse or withdraw without prejudice. Such rights may be honored implicitly by making it clear that you are asking their permission to involve them as research subjects.

5. Verbal informed consent need not be detailed and written consent is not appropriate when the research is not concerned with sensitive personal information and when subjects are peers or superiors of the researcher.

6. The cultural norms and life-styles of subjects should be considered when deciding how to approach informed consent. For example, research on homeless injection drug users should probably be preceded by a several week-long process of “hanging out” and talking with them. The resulting informal communication will raise issues they wish to discuss with the researcher. The conditions under which the research is conducted can then be negotiated orally between the researcher and the community members, as appropriate. Written documents and signed forms would expose subjects to risk of arrest and serve no redeeming purpose.

7. A wide range of media are appropriate for administering informed consent. Video tapes, brochures, group discussions, web sites, community newsletters, and the “grape vine” can be more appropriate ways of communicating with potential subjects than the potentially confusing formal consent forms that often are used.

8. When written or signed consent places subjects at risk, it must be waived. There are times when the written record is the only evidence that the subject has participated in a study in which there is acknowledgement or appearance of situations that would place the subject at risk.

9. When it is important to have some record of the informed consent but when written or signed consent would place the subject at risk or be difficult for the subject to read, one useful procedure is to have a trusted colleague witness the verbal consent.

10. Community consultation, or meeting with community leaders of the potential subjects, is a useful way to plan research that is likely to raise sensitive questions among those to be studied and members of their community. This is not a substitute for individual informed consent, but often clears the way for potential subjects to be ready to decide whether to participate.

11. In certain circumstances, persons are not in a position to decide whether to consent until immediately after their participation, e.g., in brief sidewalk interviews, which persons are likely to welcome.

12. Some research cannot validly be conducted if all details are disclosed at the outset. The alternatives to outright deception of subjects are to a) obtain permission to provide only a description of what the subject will experience, with an agreement that the full details of the study will be disclosed afterward; b) obtain permission to engage in concealment or deception with the understanding that pilot research has shown that peers of the subject do not find such concealment or deception objectionable and that a full explanation will follow their participation, c) explain that the subject might be enrolled in one of several possible conditions and to gain permission to disclose in which of these the subject was actually enrolled after his or her participation is completed.

Author’s Note: The Social and Behavioral Sciences Working Group (formerly a part of the National Human Research Protections Advisory Council but now an independent body) chaired by Felice Levine helped to develop these ideas.

Reference Melton, G., Levine, R. J., Koocher, G., Rosethal, R., & Thompson, W. (1988). Community Consultation in Socially Sensitive Research: Lessons from Clinical Trials on Treatments for AIDS. American Psychologist , 43, 573-581.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

About the Authors

Joan Sieber is professor of psychology at California State University, Hayward. She received her bachelor's, master's, and doctorate from the University of Delaware. Robert J. Levine is professor of medicine and co-chair of the interdisciplinary bioethics project at Yale University. He is also the founding editor of IRB: A Review of Human Subjects Research.

Making a Career Choice: Follow in Your Own Footsteps

In a guest column, APS Fellow Barbara Wanchisen shares observations and ideas on broadening career opportunities for psychological scientists.

Student Notebook: Finding Your Path in Psychological Science

Feeling unsure or overwhelmed as an early-career psychology student? Second-year graduate student Mariel Barnett shares advice to quell uncertainties.

Matching Psychology Training to Job Market Realities

APS President Wendy Wood discusses how graduate programs can change the habit of focusing on academic-career preparation.

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 5 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| at-rand | never | AddThis sets this cookie to track page visits, sources of traffic and share counts. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| uvc | 1 year 27 days | Set by addthis.com to determine the usage of addthis.com service. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_3507334_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loc | 1 year 27 days | AddThis sets this geolocation cookie to help understand the location of users who share the information. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

Research Interview Consent Form Template

Researcher/pi information, participant information, research details, authorization.

- I know that my participation is voluntary and that I can choose to withdraw from the research at any point.

- I know that my data is kept confidential and is used only for the purpose of this research study.

If you’re part of an organization that conducts research studies, you need the Research Interview Consent Form Template from WPForms.

The Research Interview Consent Form is the cornerstone of responsible research. By requiring the information on this form, you uphold ethical standards and ensure participants are informed and empowered.

The Functionality of the Research Interview Consent Form Template

To guarantee that you get the most out of this form template, we encourage you to edit this form to suit your needs. You might decide to include the risks and benefits of your specific research, for example, or you may want to change the language used for gathering consent.

In the meantime, we’ve included the essential elements on this form template to get you started. On our Research Interview Consent Form Template, you’ll find these vital components:

- Researcher’s Information : This form requires contact information for the researcher for queries and transparency.

- Participant’s Information : Gathering the participant’s name and the date of interview establishes a connection and helps to track progress.

- Research Details : Your form user will provide the name of the research, along with defining the ‘Purpose of the research’ and offering a ‘Description of the research’ to inform participants.

- Authorization : Research participants are assured of their right to withdraw from the research, along with the confidentiality of data, fostering trust and compliance. The form is then authenticated with a signature.

Utilize the Research Interview Consent Form on your website now to ensure that your research participants are informed and prepared. Signing up with WPForms grants you access to this and hundreds of other form templates.

Looking for something else?

Here are some other Education form templates

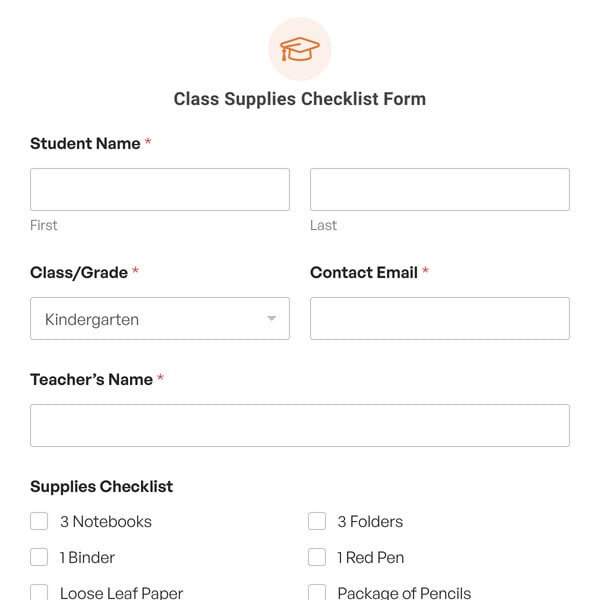

Class Supplies Checklist Form

An essential tool for simplifying the back-to-school preparation process.

Course Waitlist Registration Form

A form to help you better manage course demand.

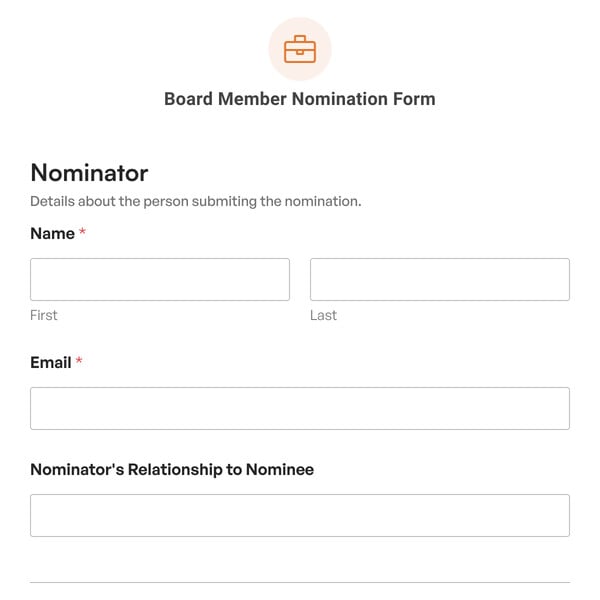

Board Member Nomination Form

Receive detailed, relevant information that will help you make informed decisions.

Telemedicine Appointment Request Form

Provide a seamless experience for patients seeking virtual healthcare services.

Nutrition Consultation Intake Form

Streamline your intake process and provide top-notch nutrition services.

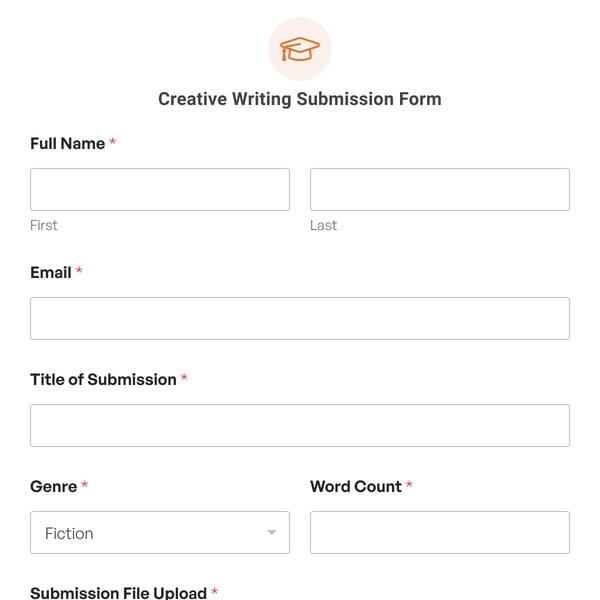

Creative Writing Submission Form

Simplifies the process of collecting and managing submissions from writers.

Our form templates let you create any kind of WordPress form in a few clicks.

Import any template with 1 click.

Ready to get started? Import any form template and start customizing it right away.

Add or Remove Fields

Use our simple drag and drop form builder to add fields, delete them, or move them around.

Customize Notification Settings

It’s easy to edit the notification emails on any template with your own text or smart tags.

Change the Confirmation Message

Easily display a custom message after submission – or forward your visitor to another page.

Change the Field Labels

Click on a field and change the text to collect the exact information you need.

Change the Notification Email

Add CCed recipients and multiple notifications so you never miss an entry.

Customize the Submit Button

Adapt the words on the button and change the color so that it matches your theme.

Publish Your Form With Ease

Hit publish — that's it! WPForms makes it easy to get your forms online without writing code.

Get Instant Form Insights

Track form submissions with our built-in analytics to see how your forms perform.

- Testimonials

- FTC Disclosure

- Online Form Builder

- Conditional Logic

- Conversational Forms

- Form Landing Pages

- Entry Management

- Form Abandonment

- Form Notifications

- Form Templates

- File Uploads

- Calculation Forms

- Geolocation Forms

- Multi-Page Forms

- Newsletter Forms

- Payment Forms

- Post Submissions

- Signature Forms

- Spam Protection

- Surveys and Polls

- User Registration

- HubSpot Forms

- Mailchimp Forms

- Brevo Forms

- Salesforce Forms

- Authorize.Net

- PayPal Forms

- Square Forms

- Stripe Forms

- Documentation

- Plans & Pricing

- WordPress Hosting

- Start a Blog

- Make a Website

- WordPress Forms for Nonprofits

Sample Consent Forms

Consent form templates.

These consent form templates have been posted for your reference. When completing and IRB submission in IRBIS, please fill in the application and use the consent form builder specific to your project. For more information, please find instructions here .

Summary of Changes to the Regulations for Informed Consent: Revised Common Rule Changes to Informed Consent and Waiver Requirements

Summary of Changes to Consent Documents:

- Informed Consent Documents – Version 2.0 Summary of Changes

- Informed Consent Documents – Version 2.1 Summary of Changes

- Informed Consent Documents – 10/26/2020 Summary of Changes

- Informed Consent Documents – 4/10/2023 Summary of Changes

| 2023-07-14 | |

| 2020-01-17 | |

| 2020-01-17 | |

| 2020-01-17 | |

| 2023-04-10 | |

| 2023-06-27 | |

| 2023-04-10 | |

| The following documents are samples. IRBIS does NOT generate these documents with application-specific information. | |

| 2017-10-30 | |

| 2024-08-09 | |

| 2017-04-17 | |

| 2018-04-19 | |

Concise Summary examples can be found here .

Guidance on the use of plain language in consent forms:

- Clinical Research Glossary

- Webinar: The Promise of Plain Language: Launching a Glossary to Support Participant Understanding of Clinical Research – Recording & Slides

There are a few additional forms that are not provided online and may be accessed below. As needed, these should be completed and uploaded to your IRB application.

Foreign Language Consent Forms

COVID-19 Related Forms:

- Spanish-IRB-COVID Information Sheet

- Spanish COVID Consent Letter v2

- Spanish COVID Informational Sheet Translation Certificate

Informed Consent Short Form (for a single subject who may be illiterate, or otherwise unable to read the consent form — used when full consent form has to be read or translated for subject).

- Informed Consent Short Form Guidance

- Simplified Chinese

HIPAA Templates

- Sample HIPAA Authorization Template

- Sample HIPAA Authorization Template in Spanish ( Certification )

Create, share, and e-sign documents in minutes using Jotform Sign.

- Integrations

- Legality Guide

- Signature Creator

- Real Estate

- See all solutions

Automatically create polished, designed documents

- PDF Templates

- Fillable PDF Forms

- Sign Up for Free

Interview Consent Agreement

Gather interview consent forms online. Can be filled out and signed on any device. Converts to a PDF instantly. Easy drag-and-drop customization.

- Consent Agreement

Whether you’re interviewing someone about music, art, or for scientific research, you’ll need an Interview Consent Agreement. With Jotform Sign , you can send out agreements and collect signatures from interviewees on any device! Just personalize the template design, share it via email, and enjoy a finalized document once all fields have been filled in and all signatures collected.

Feel free to make changes to this Interview Consent Agreement template by dragging and dropping elements. Add a logo, change fonts and text colors, update terms and conditions, and more with no coding required. You can even set up a signing order to receive signatures in a specific order! Save time by switching from paper forms to online forms with this free Interview Consent Agreement from Jotform. Take your signing process online with Jotform Sign .

Doctors Note Template

Provide your clinic or private practice’s patients with doctor’s notes they can send to their employers or professors. With this Doctor’s Note Template from Jotform Sign, it’s easy to create and customize professional doctor’s notes for any and all occasions. Include diagnosis, dates they won’t be attending work or school, contact info, and other important data.If you need to make some changes to your Doctor’s Note Template, all you need to do is open up our simple online form builder and drag and drop to personalize. Edit form fields to reflect new policies and contact information, upload branding and logos, create automated signing orders, and more. Get your patients on the mend quickly with this Doctor’s Note Template from Jotform Sign.

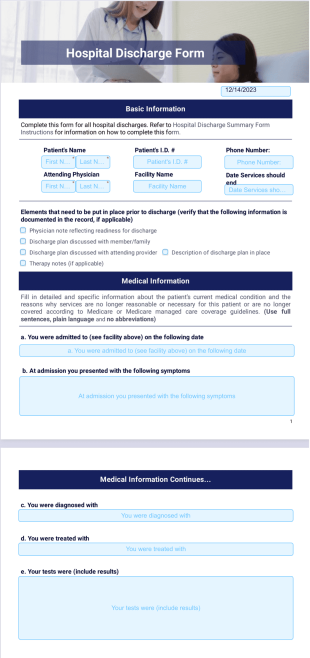

Hospital Discharge Template

It is a good practice to always crosscheck and make sure that everything is in order before discharging a patient. In order to ensure this, hospital management usually has a form which they fill and check in before discharging a patient. In our world today where people are using less of paper, this hospital discharge template is one PDF document you can use to save patient discharge information.The essence is that you can easily check the information saved in the PDF document to ensure a patient can be discharged. The hospital discharge letter template here can be modified to suit your taste.

Rent Ledger Template

A rent ledger template is a document that shows a record of rental payments made by an individual in exchange for using a rental property. Jotform Sign’s Rent Ledger template lets you fill out the names and contact information of the tenant and landlord, as well as a full transaction history. This transaction history table includes the payment dates, amount to be paid, late fees, previous fee, payment method, and the total amount. Share this ledger via email to collect e-signatures from any device.Making changes to this Rent Ledger template is a snap with our drag-and-drop form builder. You can do things like add or edit form fields, include more signature fields if there are additional participants, change fonts and colors, and make other cosmetic changes in seconds. Keep track of your rental payments with this Rent Ledger from Jotform Sign.

NonProfit Donation Consent Template

A nonprofit donation consent form is used by nonprofit or charity organizations to gather consent and manage incoming donations. Jotform Sign’s free Nonprofit Donation Consent template is easy to fully customize and share with signers to seamlessly collect e-signatures. Once both parties have signed your consent form, you’ll automatically receive a finalized PDF for your records.Make this Nonprofit Donation Consent template your own without any coding with Jotform’s powerful online builder. Simply drag and drop to add or edit form fields, include additional signature fields, change fonts and colors, include your organization’s unique branding, and more. Streamline your donation collection process and gather consent from donors in no time with Jotform Sign.

Online Therapy Consent Template

Whether you’re a therapist, psychiatrist, or psychologist — gathering a patient’s informed consent is a must. Our Online Therapy Consent template makes it easy to quickly and securely collect a patient’s consent in order to authorize online therapy treatment. Share your electronic consent form with patients via email, which they can then fill out and sign using any device. Once submitted, their finalized document is automatically sent back to you, which you can share and download as a PDF.Obtaining informed consent involves more than a signature. For consent to be informed, you need to provide patients with all relevant information regarding their therapy. Jotform Sign allows you to fully customize this template to fit your practice’s specific needs. Drag and drop to add your practice’s branding, modify the text to define the treatment, explain possible benefits and risks, describe possible alternatives, and inform patients of their right to withdraw consent at any time. You can also upgrade to unlock HIPAA compliance features for your Online Therapy Consent form.

Release of Information Template

A release of information document is a document signed by the authorizing person, allowing the recipient or holder of information to disclose or use the information through the consent of the owner. With Jotform’s free Release of Information template, you can create your own document and share it via email to securely gather an e-signature from the authorizing person. Once signed, you’ll automatically receive a finalized PDF — ready to download, print, and share.You can update this Release of Information template in a few easy clicks using Jotform’s intuitive form builder. Drag and drop to add or remove text and signature fields, change fonts and colors, edit the document’s wording, and personalize automated emails. By streamlining your signature process with Jotform Sign, you can save time better spent elsewhere.

These templates are suggested forms only. If you're using a form as a contract, or to gather personal (or personal health) info, or for some other purpose with legal implications, we recommend that you do your homework to ensure you are complying with applicable laws and that you consult an attorney before relying on any particular form.

Revised Short Form Consent Guidance & Policy

University of washington office of research, or support offices.

- Human Subjects Division (HSD)

- Office of Animal Welfare (OAW)

- Office of Research (OR)

- Office of Research Information Services (ORIS)

- Office of Sponsored Programs (OSP)

OR Research Units

- Applied Physics Laboratory (APL-UW)

- WA National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC)

Research Partner Offices

- Corporate and Foundation Relations (CFR)

- Enivronmental Health and Safety (EH&S)

- Grant and Contract Accounting (GCA)

- Institute of Translational Health Sciences (ITHS)

- Management Accounting and Analysis (MAA)

- Post Award Fiscal Compliance (PAFC)

Collaboration

- Centers and Institutes

- Collaborative Proposal Development Resources

- Research Fact Sheet

- Research Annual Report

- Stats and Rankings

- Honors and Awards

- Office of Research

© 2024 University of Washington | Seattle, WA

- Campus Crime Stats

- Message from the VP

- Leadership & Staff

- Organizational Chart

- Centers & Institutes

- Council on Research

- Strategic Plan

- Special Initiatives

- Sponsored Programs (OSP)

- Research Advancement

- Research Engagement

- Compliance & Integrity

- Industry Engagement

- LSU Innovation

- Board of Regents

- Federal Agencies

- Limited Submissions

- Crowdsourcing Research

- SPIN Grants Database

- Big Idea Grant Program

- Collaboration in Action Program

- Provost and SEC Travel Support Programs

- Research and Creative Activity Support

- Seminar/Collaborator Support Fund

- Equipment Repair & Acquisition Fund

- Internal Grants Portal

Faculty Awards

- Distinguished Research Masters

- Rainmaker Awards

- Center for Advanced Microstructures & Devices (CAMD)

- Center for Computation & Technology

- Shared Instrumentation Facility (SIF)

Research Services

- Available Services

- Request Support

- Postdoctoral Research

- Undergraduate Research (LSU Discover)

- ORCID (LSU Libraries)

- CITI Online Training

- Summer Institute

Intellectual Property

- Innovation & Technology Commercialization

- Disclose a Technology

- Innovation Park

- Small Business Development Center

Research Compliance

- PM-11: Outside Employment

- Financial Conflicts of Interest

- Export Control

- Foreign Support

- Research Safety

- Online Training

- Research Misconduct

- Responsible Conduct of Research Workshops

- Cost Sharing

- Credit Distribution

- Data Management

- Lab Closeouts

- Human Subjects (IRB)

- Animal Subjects (IACUC)

- BioSafety and RDNA (IBRDSC)

- Radiation Safety

- Environmental Health & Safety

- Research Safety Council

- Ethics Hotline

- Research News

- Scholarship First Blog

- Arts & Cultural Events

- LSU Science Café

Publications

- Research Highlights Newsletter

- Research Magazine

- Working for Louisiana

- Subscribe to GeauxGrants Newsletter

- Login (LSU Users)

Consent Form Templates

Clinical Study Template is intended to help investigators construct documents that are as short as possible and written in plain language for clinical studies.

Non-Clinical Study Template is intended to help investigators construct documents that are as short as possible and written in plain language for non-clinical studies.

Parental Permission Template is intended to help investigator construct documents that contains all required elements of consent and required institutional language which meets the readability standards for 8th-grade reading level or lower.

Child Assent Template is intended for use with children ages ~6-12.

Institutional/School Administrator Consent Template is intended to help investigator construct documents that contains all required elements of consent and required institutional language.

Consent Script Template is an example of a verbal script and accompanying contact information card used to help investigator construct documents to obtain informed consent for participation in an research study

POPULAR SEARCHES:

Video Modal

- Methodology

- Open access

- Published: 22 August 2024

Patient and public involvement and engagement in the ASCEND PLUS trial: reflections from the design of a streamlined and decentralised clinical trial

- Muram El-Nayir 1 na1 ,

- Rohan Wijesurendra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8261-8343 1 na1 ,

- David Preiss 1 ,

- Marion Mafham 1 ,

- Leandros Tsiotos 1 ,

- Sadman Islam 1 ,

- Anne Whitehouse 1 ,

- Sophia Wilkinson 1 ,

- Hannah Freeman 1 ,

- Ryonfa Lee 1 ,

- Wojciech Brudlo 1 ,

- Genna Bobby 1 ,

- Bryony Jenkins 1 ,

- Robert Humphrey 1 ,

- Amy Mallorie 1 ,

- Andrew Toal 2 ,

- Elnora C. Barker 2 ,

- Dianna Moylan 2 ,

- Graeme Thomson 2 ,

- Firoza Davies 2 ,

- Hameed Khan 2 ,

- Ian Allotey 2 ,

- Susan Dickie 2 na1 &

- John Roberts 2 na1

Trials volume 25 , Article number: 554 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Introduction

ASCEND PLUS is a randomised controlled trial assessing the effects of oral semaglutide on the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in around 20,000 individuals with type 2 diabetes in the UK. The trial’s innovative design includes a decentralised direct-to-participant invitation, recruitment, and follow-up model, relying on self-completion of online forms or telephone or video calls with research nurses, with no physical sites. Extensive patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) was essential to the design and conduct of ASCEND PLUS.

To report the process and conduct of PPIE activity in ASCEND PLUS, evaluate effects on trial design, reflect critically on successes and aspects that could have been improved, and identify themes and learning relevant to implementation of PPIE in future trials.

PPIE activity was coordinated centrally and included six PPIE focus groups and creation of an ASCEND PLUS public advisory group (PAG) during the design phase. Recruitment to these groups was carefully considered to ensure diversity and inclusion, largely consisting of adults living with type 2 diabetes from across the UK. Two members of the PAG also joined the trial Steering Committee. Steering Committee meetings, focus groups, and PAG meetings were conducted online, with two hybrid workshops to discuss PPIE activity and aspects of the trial.

PPIE activity was critical to shaping the design and conduct of ASCEND PLUS. Key examples included supporting choice for participants to either complete the screening/consent process independently online, or during a telephone or video call interview with a research nurse. A concise ‘initial information leaflet’ was developed to be sent with the initial invitations, with the ‘full’ information leaflet sent later to those interested in joining the trial. The PAG reviewed the content and format of participant- and public-facing materials, including written documents, online screening forms, animated videos, and the trial website, to aid clarity and accessibility, and provided input into the choice of instruments to assess quality of life.

Conclusions

PPIE is integral in ASCEND PLUS and will continue throughout the trial. This involvement has been critical to optimising the trial design, successfully obtaining regulatory and ethical approval, and conducting the trial.

Peer Review reports

ASCEND PLUS is an ongoing randomised placebo-controlled trial assessing the effects of oral semaglutide on cardiovascular and other outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes and no history of heart attack or stroke (NCT05441267). ASCEND PLUS will recruit approximately 20,000 participants in the UK. Potential participants are sent an invitation by post and the trial requires no in-person visits. Study medication is mailed directly to participants’ homes. This design represents a shift from the traditional concept of face-to-face interaction between research staff and participants at a clinical site and has become more common in recent years, perhaps accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic [ 1 ]. Decentralised direct-to-participant designs, including that of ASCEND PLUS, offer the possibility to expand participation in clinical trials and increase the generalisability of results [ 1 ].

The ASCEND PLUS trial design was developed with extensive patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE), to ensure that the participant experience is as good as it can be, the safety and wellbeing of the participants is protected, recruitment to the trial is successful, and the engagement and adherence of participants is maintained. ASCEND PLUS commenced recruitment in March 2023, and the estimated primary completion date of the trial is 2028.

PPIE is increasingly recognised as a key element in the development of all research [ 2 ], including clinical trial proposals and protocols. PPIE can harness the valuable insights of those living with and affected by a disease or health condition, and ensure that the trial findings are relevant to the needs of patients, and their relatives and carers [ 3 ]. “Involvement” can be defined as activities and research carried out “with” or “by” members of the public or patients, rather than “to”, “about”, or “for” them. In this instance, this refers to the active involvement of patients and members of the public in the development of the trial design and the conduct of the trial [ 4 ]. In contrast, “engagement” focuses on how the trial findings can be shared with patients and the public in a two-way process that encourages communication and interactions with researchers [ 4 ]. Despite the recognition of the importance and potential value of PPIE in clinical trials, implementation remains variable at present with inconsistency between trials [ 5 ].

Here, we aim to report the process and details of PPIE activity during the planning and initiation of ASCEND PLUS, evaluate how this helped to shape the final trial design, reflect critically on successes and aspects that could have been improved, and draw out themes and learning relevant to the implementation of PPIE in future trials.

Methods and results

Theoretical considerations.

The revised Guidance for Reporting the Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP-2) long-form checklist [ 6 ] was used to guide the drafting of this report (see Supplementary Table 1).

Resourcing of PPIE activities

PPIE in ASCEND PLUS was organised by dedicated PPIE officers working within the communications team alongside the core trial team comprised of investigators, trial managers, and administrative staff at the Nuffield Department of Population Health at the University of Oxford (which sponsors the trial). An appropriate level of funding was available in the trial budget for PPIE activity, and all PPIE representatives were able to claim monetary compensation for their time, lived experience, and contribution, in line with guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) [ 7 ] and accepted best practice. Any out-of-pocket expenses (such as travel) incurred by PPIE representatives were reimbursed in full, and refreshments were provided at in-person meetings.

Format of PPIE activities

PPIE activity in ASCEND PLUS consisted of several linked components, beginning early in the design phase of the trial and is planned to continue through to trial completion and dissemination of the results.

Firstly, a series of six patient and public focus groups were convened to address specific issues. These focus group meetings largely involved people living with type 2 diabetes and included people from diverse backgrounds from across the UK.

Secondly, a trial-specific Public Advisory Group (PAG) was established. The PAG is responsible for providing feedback, advice, and opinions on many different aspects of ASCEND PLUS over the entire lifecycle of the trial.

Thirdly, in order to ensure patient involvement in the design and conduct of ASCEND PLUS at a strategic level, two members of the PAG who are individuals living with diabetes were also invited to join the Trial Steering Committee.

Steering Committee meetings, focus groups, and PAG meetings were largely conducted online using remote meeting software. Two in-person PPIE workshops were convened in Oxford. This combination of online and in-person meetings has been suggested to be favourable in a previous mixed methods study [ 8 ].

Recruitment and selection of focus groups and the PAG

The recruitment and selection of the focus groups and the PAG was carefully considered to ensure inclusivity and representation, for features including age, sex, and ethnicity. People living with type 2 diabetes were prioritised, given that ASCEND PLUS is a trial in this population.

The six focus groups were organised with support from the Nuffield Department of Population Health’s Public Advisory Group and four external organisations (Table 1 ). Each focus group was drawn from a specific geographic location (Leicester, Oxford, the north of England [two groups], Wales, and Scotland), to provide coverage of the areas of the UK in which ASCEND PLUS plans to recruit. The focus group based in Leicester was from the Centre for Ethnic Health Research and consisted of individuals of South Asian, Black Caribbean, and Black African ethnicity. The size of, and strategy used to achieve diverse representation within, each group was usually determined by the groups themselves.

Members of the PAG were invited from an existing departmental public advisory panel and the focus groups described above. The PAG was chosen to comprise a diverse group of patients and the public.

Involvement of PPIE panels and the PPIE advisory group in the research proposal

During the design phase of ASCEND PLUS, the six online PPIE focus groups (described above) were convened to address specific issues. Given the remote design of the trial with no in-person visits, the main topics discussed were the consent model and the recruitment/invitation methods. There was also discussion about other aspects of the trial design, including the active run-in, in which all participants receive the active drug prior to randomisation. These concepts were serially developed across the six focus groups, which took place between June and September 2021, with revisions made to the study design in response to the feedback received prior to the application for ethical approval.

Two people living with diabetes were next invited to join the Steering Committee. These individuals attended the first Steering Committee meeting in June 2021 and will continue to attend Steering Committee meetings until the completion of the trial. These patient and public contributors are members of the Steering Committee, contribute to discussions at meetings, and can vote on any decisions made by the Committee. They are also the joint senior authors of this publication (SD and JR).

The trial PAG was then assembled, including SD and JR amongst the members. The PAG contributed in detail to the design and review of all patient-facing study material, the online forms and videos used for the trial, and the trial website. This activity was organised through emails and online group meetings, as well as one face-to-face workshop in Oxford. The PAG will continue to contribute during the remainder of the trial, for example by reviewing planned patient newsletters and advising on local activities to aid recruitment. The PAG will also input on the interpretation of the trial results in due course, and specifically on their presentation and dissemination to patients and the public.

Impact of PPIE on ASCEND PLUS design and conduct

The six PPIE focus groups were critical to shaping the design and conduct of ASCEND PLUS. Full details of the composition and date of each of the six focus groups, the subjects discussed, and the feedback and impact are summarised in Table 1 .

Initially, it had been planned to invite all participants to complete self-directed online screening and consent, with an option of a telephone or video call if needed. A clear theme that emerged in the focus groups was support for choice in how participants interact with the trial: i.e. either online completion of study assessments on their own device (with the option to speak to a research nurse or study doctor at any time) or completion of study assessments during interviews with a research nurse. Therefore, recording of informed consent also needed to include both an online consent option (that can be completed by a participant independently) and the option to give consent during a telephone or video call with a research nurse. It was also felt to be important that participants can switch between these two methods of participation at any stage if they wish to. The exception to this concept was for non-English speakers, in whom a telephone or video call with a research nurse (aided by a translator) was recommended to ensure adequate understanding. In light of this feedback from the focus groups, the trial procedures were modified. The updated trial design now asks potential participants to indicate on the initial reply form which method (self-directed online versus telephone/video call with a research nurse) they prefer. Options have also been added to allow participants to change their trial interaction method during the course of the trial.

Another key impact on design and conduct of the trial resulted from feedback that the patient information leaflet was very long, due to the need to contain multiple items deemed mandatory by regulatory bodies. The focus group supported provision of an abbreviated “initial information leaflet” (rather than the “full” participant information leaflet) with the invitation letter, with the “full” patient information leaflet [ 9 ] subsequently supplied to those individuals who had declared interest in participating after reviewing the abbreviated leaflet.

The PPIE focus groups supported the proposed invitation method for ASCEND PLUS. In brief, this is conducted with the support of the NHS DigiTrials recruitment support service who undertake a search of electronic medical records to identify individuals who are potentially eligible (without individual patient consent at this stage). The name, address, and postcode of these individuals are then passed securely to a mailing house (who also handle patient letters for the NHS) who then send out study invitation letters. The details of potential participants are not disclosed to the ASCEND PLUS study team unless and until the participant returns the reply form, which includes the participant’s name and the details they add to it (such as telephone number, or email address). The reply form also contains a unique identifier which the ASCEND PLUS team send to NHS DigiTrials to obtain the participant’s name, address, sex, date of birth, NHS number, and GP surgery details from NHS records. The positive feedback from the PPI focus groups regarding the use of healthcare data in this way was cited in the application for regulatory approval. This recruitment method was supported by the Health Research Authority (HRA), who also followed advice from the Confidentiality Advisory Group (an independent body which provides expert advice on the use of confidential patient information). A separate data protection leaflet which is supplied to prospective participants covers all aspects of how data about ASCEND PLUS participants is processed [ 10 ].

The ASCEND PLUS PAG also undertook a detailed review of the three leaflets discussed above (initial information leaflet, full participant information leaflet, data protection leaflet), the trial invitation letter, and the study treatment information leaflets (one of which is included with each pack of study treatment mailed to a participant). Recommended text and content changes were made accordingly, ensuring that the text of each document remained consistent with trial processes. This extensive PPIE review and consultation process has resulted in documents which are easier to understand and more inclusive. This also included feedback about accommodating people with visual impairments. Examples of specific changes made to the text of study documents are shown in Fig. 1 .

Examples of specific changes made to the text of the ASCEND PLUS participant information leaflet after PPIE input

The PAG were then involved in co-developing an animated video to support the self-directed online consent process. The PAG initially contributed to the development of the script and then provided feedback on the images used in the storyboard, with many of the specific points raised implemented in the final version. For example, the images of potential participants in the video were updated to ensure greater diversity, and a border line was drawn on a map of the UK to highlight the geographical areas in which ASCEND PLUS plans to recruit.