African Americans in the Civil War

Civil 29th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteers, U.S. Colored Troops, in formation near Beaufort, S.C., where Cooley lived and worked. It was Connecticut’s first African American regiment.

African Americans were freemen, freedmen, slaves, soldiers, sailors, laborers, and slaveowners during the Civil War. As a historian, I must be objective and discuss the facts based on my research. Some of our history may be different from how it has been previously taught and some of it is not very pretty.

In 1860, both the North and the South believed in slavery and white supremacy. Although many northerners talked about keeping the federal territories free land, they wanted those territories free for white men to work and not compete against slavery. The two parts of the country had two very different labor systems and slavery was the economic system of the South. Its four million slaves were valued between three and four billion dollars, in 1860.

The South seceded from the United States because they felt that their slave property was going to be taken away. When reading the secession documents , the primary reason for secession was to protect their slave property and expand slavery.

There were two broad categories of enslaved people at that time, agricultural slaves, and urban slaves. Most of us are familiar with agricultural slavery, the system of slavery on the farms and plantations. On the plantations, there were house servants and field hands, the house servants were usually better cared for, while field hands suffered more cruelty. Some slaveowners treated their slaves very well, some treated their slaves very cruelly and some were in between the extremes. Black slaveowners generally owned their own family members in order to keep their families together.

Field hands generally worked in the fields from sunrise to sunset and were generally watched by their slaveowners and or overseers. House servants were much closer to the families who owned them and in many cases were very loyal to their masters’ families. In some cases, the house servants were related to these families.

Slaves and free Blacks were often classified by their percentage of white blood. For example, mulattos are half-white, quadroons are one-fourth Black, and octoroons are one-eighth Black. The enslaved people in these categories were more valuable than those of pure African descent.

Urban slaves had much more freedom, as they lived and worked in the cities and towns. Although some plantation slaves had become craftsmen, most of the urban slaves were craftsmen and tradesmen. These slaves were rented by their slaveholders to others, usually for a year at a time. They worked in factories, stores, hotels, warehouses, in houses and for tradesmen. In some cases, these enslaved people would earn money for themselves, if they worked more hours or were more productive than their rental contract requirements. They were able to work with free Blacks and were able to learn the customs of white Americans.

There was a coalition of people, Black and white, Northerners and Southerners that formed a society to colonize free Blacks in Africa. The American Colonization Society (ACS) was able to keep this mixture of people together because the various factions had different reasons for wanting to achieve the goals of this society. They founded Liberia and by 1867, they had assisted approximately 13,000 Blacks to move to Liberia. Some of the ACS really wanted to help Blacks and thought that they would fare better in Africa than America, but the slaveholders thought free Blacks were a detriment to slavery and wanted them removed from this country. The ACS survived from 1816 until it formally dissolved in 1964. In fact, even President Abraham Lincoln believed that this would be a solution to the problem of Blacks being freed during the Civil War. He found out that this was not the solution to the problem after a failed colonization attempt in the Caribbean in 1864.

Abolitionists, a very vocal minority of the North, who were anti-slavery activists, pushed for the United States to end slavery. After the John Brown Harper’s Ferry raid of 1859 , Southerners thought that the majority of Northerners were abolitionists, so when moderate Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860, they felt that their slave property would be taken away.

In the pre-1800 North, free Blacks had nominal rights of citizenship; in some places, they could vote, serve on juries and work in skilled trades. As the need to justify slavery grew stronger and racism started to solidify, most of the northern states took away some of those rights. When the northwestern states came into being, Blacks suffered more severe treatment. In Ohio, Blacks could not live there without a certificate proving their free status. Illinois had harsh restrictions on Blacks entering the state and Indiana tried barring them altogether. There was mob violence against Blacks from the 1820s up to 1850, especially in Philadelphia where the worst and most frequent mob violence occurred. City officials refused to protect Blacks and blamed African Americans for their “uppity” behavior.

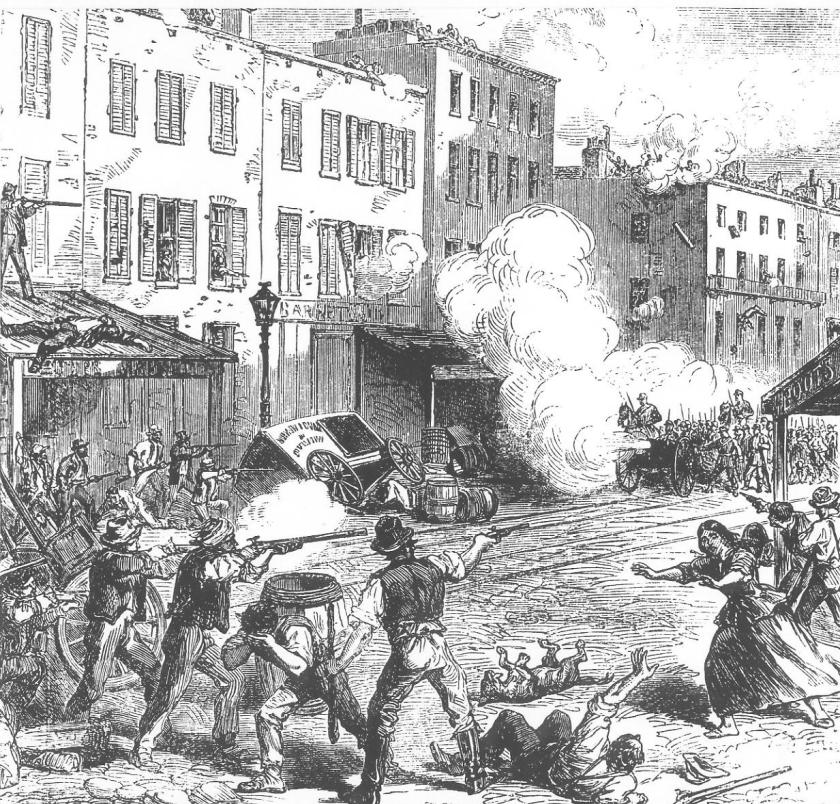

Free African Americans in the North and the South faced racism. White people, no matter how poor, knew that there were classes of people under them – namely Blacks and Native Americans. Most white Americans defended slavery as the natural condition of Blacks in this country. Most immigrants in the North did not want to compete with African Americans for jobs because their wages would be lowered. This created animosity between Blacks and immigrants, especially the Irish – who killed many Blacks in the draft riots in New York City in 1863.

African Americans and their white allies in the North, created Black schools, churches, and orphanages. They also created mutual aid societies to provide financial assistance to Blacks. The Underground Railroad aided many escaped enslaved people from the South to the North, who were able to get support from the abolitionists.

In the North, most white people thought about Blacks in the same way as people of the South. The many immigrants that entered the country for a better life, considered Blacks as their rivals for low paying jobs. Many of the northwestern states and the free territories did not want slavery in their areas. Not because they wanted freedom for Blacks, but they wanted to have free areas for white men, and exclude Blacks in those states and territories, altogether. Blacks would drive down the wages for free white men. Illinois and Kansas represent two such states.

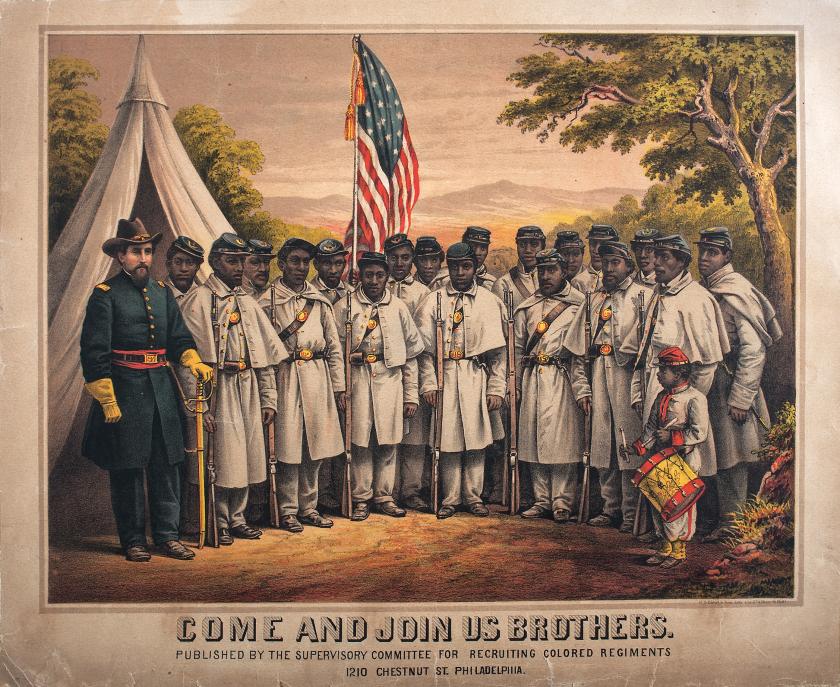

However, Blacks still wanted to fight for the Union army in the Civil War! Many wanted to prove their manhood, some wanted to prove their equality to white men, and many wanted to fight for the freedom of their people.

The North began to change its mind about Black soldiers in 1862, when in July Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Acts, allowing the army to use Blacks to serve with the army in any duties required. Some generals used this act to form the first Black regiments. President Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862 to take effect on January 1, 1863. The Emancipation allowed Blacks to serve in the army of the United States as soldiers. In May 1863, the Bureau of Colored Troops was formed, and all of the Black regiments were called United States Colored Troops .

More than 200,000 Black men serve in the United States Army and Navy. The USCT fought in 450 battle engagements and suffered more than 38,000 deaths. Significant battles were Nashville, Fort Fisher, Wilmington, Wilson’s Wharf, New Market Heights (Chaffin’s Farm), Fort Wagner, Battle of the Crater, and Appomattox.

I want to make a special point here, the Emancipation Proclamation did not free all of the slaves in the country, although many people even today believe that it did. It only freed slaves in the Southern states still in rebellion against the United States. So, the Border States and territory already captured by the Union army still had slavery. The 13 th Amendment freed all the slaves in the country in 1865.

Some important African American people during the Civil War era were:

- Frederick Douglass was the son of a slave and a white man; since his mother was a slave – he was a slave. He became the most important African American of the Civil War era. He was both an urban and agricultural slave, who was treated fairly well in the city but cruelly on the plantation. Douglass learned to read and write, he learned a trade and escaped to freedom. He became an abolitionist lecturer, an author, a publisher, a recruiter for the United States Colored Troops, a marshal for the District of Columbia, and an ambassador to both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. He criticized President Lincoln and then became a friend of the President.

- Harriet Tubman , at 13 years old was struck in the head by an overseer; she had seizures or sleeping spells for the rest of her life. She is called “Moses,” and led many fellow slaves to freedom (100-300). During the Civil War, she served with the Union army as a scout, spy, nurse, cook, and laundress. She led Union raids in South Carolina, freeing slaves in those areas while assisting the USCT infantry.

- William Wells Brown was born into slavery on November 6, 1814, to a slave named Elizabeth and a white planter, George W. Higgins. He escaped in Ohio and added the adopted name of Wells Brown - the name of a Quaker friend who helped him. He became a conductor for the Underground Railroad, lecturer on the antislavery circuit in the United States and Europe, and a historian. He wrote his autobiography, which was a bestseller second only to Frederick Douglass’ autobiography. He also wrote The Negro in the American Rebellion (1867) which is recognized as the first book about Black soldiers in the Civil War.

- Elizabeth Keckley was the daughter of a slave and her white owner, she was considered a “privileged slave,” learning to read and write despite the fact that it was illegal for slaves to do so. She became a dressmaker, bought her freedom, and moved to Washington, D. C. In Washington, she made a dress for Mrs. Robert E. Lee; this sparked a rapid growth for her business. She made dresses for Mrs. Jefferson Davis and Mrs. Abraham Lincoln, becoming a loyal friend to Mary Todd Lincoln. Keckley also founded the Contraband Relief Association, an association that helped slaves freed during the Civil War.

- Charlotte Forten Grimke was born into a wealthy Black abolitionist family in Philadelphia, PA,. She was a well-educated writer and poet, who went to Sea Island South Carolina to teach the liberated slaves to read and write. She later married the mulatto half-brother of the famous abolitionists Grimke sisters.

- Sgt. Christian Fleetwood served in the 4 th USCT. On September 29 th during the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, he caught the American flag before it hit the ground, after the color bearer was shot down. He continued to carry the flag and rallied his men. His bravery earned him the Medal of Honor.

- Sgt. William Carney served in the 54 th Massachusetts Infantry . On July 18, 1863, at the Battle of Fort Wagner, he earned the Medal of Honor for saving the American flag, despite being severely wounded. He carried the flag all the way to the entrance of the fort before he retreated.

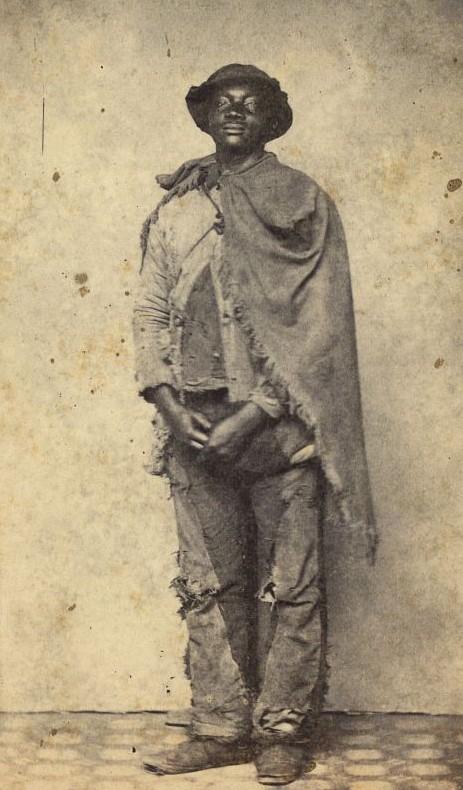

- Sergeant Nimrod Burke of the 23 rd USCT, started the war as a civilian teamster and scout for the 36 th Ohio Volunteer Infantry in April 1861. In 1864, he enlisted in the 23 rd United States Colored Troops. He was one of many Black men who served with the Union army in another capacity, then served with the United States Colored Troops.

African Americans were more than enslaved people during the Civil War. Many became productive citizens, including Congressmen, a senator, a governor, business owners, tradesmen and tradeswomen, soldiers, sailors, reporters, and historians. Research African American history in libraries and museums, to find out the contributions made during and after the Civil War.

Further Reading

- A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation By: David W. Blight

- A Brave Black Regiment: The History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry 1863-1865 By: Capt. Luis F. Emilio

- Slavery and the Making of America By: James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton

- Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era By: James M. McPherson

- The Negro's Civil War: How American Blacks Felt and Acted During the War for the Union By: James M. McPherson

Behind the Screen: Unveiling the Real Soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts

Charleston during the Civil War

Charleston Harbor

Related battles, you may also like.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Black Civil War Soldiers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: November 22, 2022 | Original: April 14, 2010

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation: “All persons held as slaves within any States…in rebellion against the United States,” it declared, “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” (The more than 1 million enslaved people in the loyal border states and in the Union-occupied parts of Louisiana and Virginia were not affected by this proclamation.) It also declared that “such persons [African American] of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States.” For the first time, Black soldiers could fight for the U.S. Army.

A 'White Man’s War'?

Black soldiers had fought in the Revolutionary War and—unofficially—in the War of 1812 , but state militias had excluded African Americans since 1792. The U.S. Army had never accepted Black soldiers. The U.S. Navy, on the other hand, was more progressive: There, African Americans had been serving as shipboard firemen, stewards, coal heavers and even boat pilots since 1861.

Did you know? Sixteen Black soldiers won the Congressional Medal of Honor for their brave service in the Civil War.

After the Civil War broke out, abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass argued that the enlistment of Black soldiers would help the North win the war and would be a huge step in the fight for equal rights: “Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket,” Douglass said, “and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.” However, this is just what President Lincoln was afraid of: He worried that arming African Americans, particularly former or escaped slaves, would push the loyal border states to secede. This, in turn, would make it almost impossible for the Union to win the war.

The Second Confiscation and Militia Act (1862)

However, after two grueling years of war, President Lincoln began to reconsider his position on Black soldiers. The war did not appear to be anywhere near an end, and the Union Army badly needed soldiers. White volunteers were dwindling in number, and African-Americans were more eager to fight than ever.

The Second Confiscation and Militia Act of July 17, 1862, was the first step toward the enlistment of African Americans in the Union Army. It did not explicitly invite Black people to join the fight, but it did authorize the president “to employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of this rebellion…in such manner as he may judge best for the public welfare.”

Some Black people took this as their cue to begin forming infantry units of their own. African Americans from New Orleans formed three National Guard units: the First, Second and Third Louisiana Native Guard. (These became the 73rd, 74th and 75th United States Colored Infantry.) The First Kansas Colored Infantry (later the 79th United States Colored Infantry) fought in the October 1862 skirmish at Island Mound, Missouri . And the First South Carolina Infantry, African Descent (later the 33rd United States Colored Infantry) went on its first expedition in November 1862. These unofficial regiments were officially mustered into service in January 1863.

The 54th Massachusetts

Early in February 1863, the abolitionist Governor John A. Andrew of Massachusetts issued the Civil War’s first official call for Black soldiers. More than 1,000 men responded. They formed the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the first Black regiment to be raised in the North. Many of the 54th soldiers did not even come from Massachusetts: one-quarter came from slave states, and some came from as far away as Canada and the Caribbean. To lead the 54th Massachusetts, Governor Andrew chose a young white officer named Robert Gould Shaw.

On July 18, 1863, the 54th Massachusetts stormed Fort Wagner, which guarded the Port of Charleston, in South Carolina. It was the first time in the Civil War that Black troops led an infantry attack. Unfortunately, the 600 men of the 54th were outgunned and outnumbered: 1,700 Confederate soldiers waited inside the fort, ready for battle. Almost half of the charging Union soldiers, including Colonel Shaw, were killed.

Confederate Threats

In general, the Union army was reluctant to use African American troops in combat. This was partly due to racism: There were many Union officers who believed that Black soldiers were not as skilled or as brave as white soldiers were. By this logic, they thought that African Americans were better suited for jobs as carpenters, cooks, guards, scouts and teamsters.

Black soldiers and their officers were also in grave danger if they were captured in battle. Confederate President Jefferson Davis called the Emancipation Proclamation “the most execrable measure in the history of guilty man” and promised that Black prisoners of war would be enslaved or executed on the spot. (Their white commanders would likewise be punished—even executed—for what the Confederates called “inciting servile insurrection.”) Threats of Union reprisal against Confederate prisoners forced Southern officials to treat Black soldiers who had been free before the war somewhat better than they treated Black soldiers who were formerly enslaved—but in neither case was the treatment particularly good. Union officials tried to keep their troops out of harm’s way as much as possible by keeping most Black soldiers away from the front lines.

The Fight for Equal Pay

Even as they fought to end slavery in the Confederacy, African American Union soldiers were fighting against another injustice as well. The U.S. Army paid Black soldiers $10 a month (minus a clothing allowance, in some cases), while white soldiers got $3 more (plus a clothing allowance, in some cases). Congress passed a bill authorizing equal pay for Black and white soldiers in 1864.

By the time the war ended in 1865, about 180,000 Black men had served as soldiers in the U.S. Army. This was about 10 percent of the total Union fighting force. Most—about 90,000—were former (or “contraband”) enslaved people from the Confederate states. About half of the rest were from the loyal border states, and the rest were free Black people from the North. Forty thousand Black soldiers died in the war: 10,000 in battle and 30,000 from illness or infection.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

African American Soldiers in the Civil War Research Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Challenges faced and contributions of african americans during the civil war.

Bibliography

The African American soldiers faced adverse racial discrimination during the Civil War. Despite President Lincoln opening doors for the black people to join the Union Army in 1862, these members were segregated on the basis of their skin color. They faced humiliation in terms of duties and privileges that were evident during the battle. There were many problems that the African American group confronted during the fighting then due to the prejudice that was done to them by their white counterparts. These victims of racial injustice were assigned to undertake non-combat laborers and cook duties. In addition, they were only paid $10 per month with $3 as a deduction for clothing. The whites were paid $13, where the aspect of disparity came along. Thus, black soldiers never received any special honor for the hard tasks due to racial discrimination. Rather, their problems continued further, making it clear that the US military administration did not offer equality. African American soldiers contributed in the War by undertaking non-combat tasks and support services but were humiliated due to prejudice, brutality and segregation that were done to them by the white troops.

There were many problems that black troops faced during the Civil War. Due to racial prejudice, they were not allowed to command any army section. Rather, they were non-commissioned officers under the command of white soldiers. There were severe punishments for the African American soldiers when the War had become intense. In hands of the Confederate Army, the black affiliated military personnel handled a significant peril. The intensity of the War led to the collisions that led to the enslavement of many black soldiers until President Lincoln had to pass a General Order 233, which barred any threat that would lead to slavery to the black troops. During the battle, the war-concentrated zones were depicted by African American soldiers as the frontline group that was less armed than white soldiers.

The black captives who were prisoners of War (POW) received harsh treatment compared to white captives. For example, the Confederate Army shot to death African American soldiers who served under the then Union Army after they were captured in Fort Pillow in 1864. That matter sparked a raft of reactions, with President Lincoln facing sanctions from the interest group parties in favor of the affected people. Therefore, from the above elements, it is true that African Americans were humiliated by the white soldiers during the War.

From the records of the Civil War, many African American soldiers served the country. Close to 300,000 black men participated in the battle, all of whom were taken as second-class citizens. It is more significant to be inconsiderate to the black troops than to disregard their efforts to assist in the affairs of the War. In 1863, the Civil War had risen notably in all the affected regions of North and Southern America that the government had to incorporate the black soldiers. However, the majority did not see the essence of recognizing them by treating them fairly.

Part of the reasons why the Civil War escalated was because there was no unity in terms of resources and deployment aspects to soldiers. About 60% of the total black men who served in the military during the Civil War were former slaves. Thus, the ideology of treating people of color unfairly continued during the Civil War. It is important to mention that whenever one seemed to resist the rule under the army, they were taken to prison or killed without any legal process. During the 19 th century, black people were considered inferior to whites, which is why the Civil War was characterized by racial prejudice.

The contributions of the African Americans during the Civil War comprised a raft of duties assigned to them by the white commanders. Firstly, the black men served in the artillery, and they backed the military in areas where non-combat techniques were required. In other words, the African American soldiers were like assistant troops to most white soldiers then. For example, it was the duty of African American military personnel to cook for the groups during the War. Secondly, these minority groups served as carpenters, cooks, nurses, scouts, and other specializations that formed skeleton services required during the War. Spies, surgeons, and guards were mainly given to the black people. Only a few black commissioned officers were given the high rank, with black women taking nursing roles. For example, Harriet Tubman was a popular scout during the Civil War then who scouted for the volunteers of the South during the battle.

In addition to the duties mentioned previously, there are examples of black men who extensively formed part of the combat team during the War then. The black infantrymen fought heatedly at Milliken’s Bend, Los Angeles, Nashville, TN, among other phenomenal areas. In 1863, the 54 th Volunteers lost about 66% of the officers during the assault of Fort Wagner. Therefore, it is indisputably that African American soldiers had shown significant valor in the War that deserved honor and not mistreatments. The active involvement of black troops in the War made it far less likely to say African Americans were to remain in slavery after the battle. It is essential to mention that black military personnel got involved in the War due to the threats made against their lives. Many black men were killed and others imprisoned during the execution of the threats by the Confederate government.

During the Civil War, African American soldiers faced battles of discrimination in terms of wages, promotions, and medical rights. Despite the promise by the administration to have equality, it was hard for the black men to survive in a white-centered military that perceived them as lesser individuals who would bring a negligible impact on the War. There was the poor provision of services and equipment whereby the victims were subjected to unhealthy foods and inferior allowances. The white soldiers were paid and given cloth allowance while the black personnel would be deducted money to pay for their clothes. In this case, one would wonder what was the line of argument when these discriminatory policies were passed? However, the African American soldiers pressed further to ensure they gave a hand in the War as one way of starting a journey of revolution against racial discrimination.

Additionally, black troops were given menial jobs that proved the humiliations from the majority of white soldiers. Most of the black men kept doing fatigue work, which affected their productivity. The white soldiers whipped the black troops or tied them by their thumbs. As depicted earlier, if captured by the Confederates, there was no negotiation but to execute them. These are various factors that prove to the modern world that racism did not start the other day but rather during the ancient times before even the 20 th and 21 st centuries. One of the Union line leaders gave a picture of the importance of black soldiers getting involved in the War. The captain said that it was necessary to condemn the brutal degradation done to the African American groups that fought during the War.

As a result of the humiliations that were done by the white military personal, African American soldiers confronted extensive constraints that led to the loss of lives, permanent disability, and psychological torture that developed a negative heritage in terms of racism matters. Despite the vision that Fredrick Douglas had concerning the reinforcement brought along the black troops, the white soldiers did not give any honor to them until 1865, when some members started getting fair treatment. Therefore, the inclusion of black troops in the Civil War benefited the country but posed a threat to racial freedom, more so to the black men.

The African American soldiers were involved in the Civil War by President Lincoln. However, these military personnel never received equal treatment despite their indisputable contributions to the War. The black troops were underpaid and deducted on clothing. They did not get major benefits such as allowances and healthcare privileges. The white soldier would whip the soldiers of African descent. The Confederates executed other black men. The fact that African American soldiers were given menial jobs and disregarded in the battle shows high rates of racial discrimination. Therefore, the racial segregation that is seen today was witnessed before. There is a need to fight for a society that respects the racial affiliation of members to ensure there is equality. When racial prejudice is reduced within the society, humanitarian rights will be upheld hence, improving the dignity for individuals.

Foner, Eric. “Rights and the Constitution in Black Life During the Civil War and Reconstruction”. The Journal of American History 74, no. 3 (1987).

Lovett, Bobby. “African Americans, Civil War, and Aftermath in Arkansas.” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 54, no. 3 (1995): 304-358. Web.

Mammina, Laura. “In The Midst of Fire and Blood: Union Soldiers, Unionist Women, Military Policy, and Intimate Space During the American Civil War”. Civil War History 64, no. 2 (2018): 146-174.

Reid, Richard M. Freedom for Themselves: North Carolina’s Black Soldiers in the Civil War Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Shaffer, Donald R. “African American Civil War Soldiers”. Journal of American History 105, no. 4 (2019): 1101-1103.

Williams, George Washington. A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865. New York: Fordham University Press, 2012.

- Africa’s Colonization and Alien Races’ Contribution

- Du Bois on Black Reconstruction in America

- Abraham Lincoln: The Great Emancipator

- The Removal of Confederate Statues

- Abraham Lincoln Against Slavery

- African-American Press in Development Context

- The African American Struggle to Sustain Wealth

- The National Museum of African-American History and Culture Digital Archive

- The Flatbush African Burial Ground's History

- The Rise to the “New Negro” Movement

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, April 10). African American Soldiers in the Civil War. https://ivypanda.com/essays/african-american-soldiers-in-the-civil-war/

"African American Soldiers in the Civil War." IvyPanda , 10 Apr. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/african-american-soldiers-in-the-civil-war/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'African American Soldiers in the Civil War'. 10 April.

IvyPanda . 2023. "African American Soldiers in the Civil War." April 10, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/african-american-soldiers-in-the-civil-war/.

1. IvyPanda . "African American Soldiers in the Civil War." April 10, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/african-american-soldiers-in-the-civil-war/.

IvyPanda . "African American Soldiers in the Civil War." April 10, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/african-american-soldiers-in-the-civil-war/.

- Berry College

- Berry History

Freemantown Research Guide

- African Americans in the U.S. Civil War

- Thomas Freeman & Henrietta Freeman

- Mead Freeman & Elizabeth

- Sanford P. Freeman & Susan Cathey

- Essex Freeman & Hannah Montgomery

- Nick Freeman & Susan Finley

- Other Families

- Primary Documents

- Thomas Freeman's Unit

- Sources on African Americans in the Civil War

- A Side Note: Dr. A.J. Higginbotham

- Early Black Schools in Floyd County

- Photo Galleries

Thomas Freeman's Unit, the 44th U.S. Colored Infantry

In 1862 the Union had begun to enlist Black men in military service. After the 1 Jan 1863 Emancipation Proclamation freed all those enslaved in Confederate territory, recruitment was extended. During the Atlanta campaign of May-September 1864, the enrollment of Black soldiers began in occupied areas of northwestern Georgia under authority granted to Colonel Ruben D. Mussey, the Nashville, Tennessee-based commissioner for the Organization of U.S. Colored Troops in the Department of the Cumberland. From July to September 1864, the 44th U.S. Colored Infantry was stationed in Rome, for recruiting purposes. By late summer the 44th USCI contained some 800 Black enlisted men, including Thomas Freeman, who enlisted in Company I on 30 June 1864. The unit was commanded by Colonel Lewis Johnson, who was white.

Organized at Chattanooga, Tenn., April 7, 1864. Attached to District of Chattanooga, Dept. of the Cumberland, to November, 1864. Unattached, District of the Etowah, Dept. of the Cumberland, to December, 1864. 1st Colored Brigade. District of the Etowah, Dept. of the Cumberland, to January, 1865. Unattached, District of the Etowah, to March, 1865. 1st Colored Brigade, Dept. of the Cumberland, to July, 1865. 2nd Brigade, 4th Division, District of East Tennessee, July, 1865. Dept. of the Cumberland and Dept. of Georgia to April, 1866.

- Post and garrison duty at Chattanooga, Tennessee until November, 1864.

- Action at Dalton, Georgia, October 13, 1864.

- Battle of Nashville, Tennessee, December 15-16, 1864.

- Pursuit of Hood to the Tennessee River, December 17-28, 1864

- Post and garrison duty at Chattanooga, Tennessee, in District of East Tennessee and in the Dept. of Georgia until April, 1866.

- Mustered out April 30, 1866.

- African-American soldiers in the Civil War by Robert Scott Davis. Chattanooga Times Free Press , April 7, 2013.

- Battle Unit Details (National Park Service)

- Black Troops in Civil War Georgia by Clarence L. Mohr. New Georgia Encyclopedia , December 10, 2008.

- Freedom earned: Marker recalls role of black soldiers in Civil War. Dalton Daily Citizen . The dedication of a new historical marker on Fort Hill, the site of the only Civil War battle involving black soldiers to take place in Georgia.

- He found freedom, then risked it to fight for others by Jeremy Redmond. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution , February 18, 2024.

- Honoring 44th U.S. Colored Troops: From Slaves to Union Warriors. The Civil War Picket , October 4, 2010.

- Roster, 44th U.S. Colored Troops Infantry

- Story of an African-American Civil War Regiment by Robert Scott Davis. Chattanooga Times Free Press , April 21, 2013.

- What Happened to Private Pryor and the 44th US Colored Infantry? by Angela Y. Walton-Raji. USCT Chronicle , February 10, 2011

- White and Black in Blue: The Recruitment of Federal Units in Civil War North Georgia by Robert S. Davis. Georgia Historical Quarterly 85, no. 3 (2001): 347-74. "The new black regiment moved to Rome, Georgia, in the middle of July 1864. Wagon trains of mixed white and black recruiting parties fanned out across the countryside in search of enlistees. To the disdain of white Georgians, Johnson quickly raised the minimum number needed for a regiment, some eight hundred men total, from fugitive slaves from Alabama and North Georgia. Muster records do not survive for the Forty-fourth to show place of residence, but a partial list of the former slaves indicates that they escaped from plantations and farms throughout northwest Georgia ... Colonel Mussey, formerly captain in the Nineteenth United States Infantry, wrote of his new soldiers: "For raiders in the enemy's country, these Colored Troops will prove superior, they are good riders - have quick eyes at night . . . know all the byways."

- “This Is the Point on Which the Whole Matter Hinges”: Locating Black Voices in Civil War Prisons by Caroline Wood Newhall. Thesis, University of North Carolina, 2016.

- The 44th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment and the Dalton Fort by E Raymond Evans and David Scott

Books on African Americans in the U.S. Civil War

A few sources to get started on learning more about what Thomas Freeman's military life might have been like, as well as the history and politics of Black men's service during the Civil War.

- Find more books on African Americans in the U.S. Civil War

- << Previous: Other Resources

- Next: A Side Note: Dr. A.J. Higginbotham >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 11:28 AM

- URL: https://libguides.berry.edu/freemantown

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

In Their Own Words

“A salute fired early from Fort Duane in honor of the reported capture of Charleston & Columbia S.C. The Colored troops reported to have taken quite an active part in the Capture of Charleston which I hope is true as it will be the means of showing Genl Sherman that colored troops can & will fight.” –Lt. John Freeman Shorter, 55th Massachusetts Infantry, February 20, 1865

“friction between the races. though the colored troops are not equipped with guns, according to all reports, they behaved themselves most bravely and pluckily against the marines.” –cpl. roy plummer, 506th;engineers, december 19, 1918.

Diaries and letters written by members of the military give a glimpse into the everyday lives of servicemembers and reveal a more personal view of the military experience. These records often capture first-hand details of service and war that might otherwise be forgotten. For African Americans serving in a segregated military, writing in diaries and sending letters often helped them cope with difficult issues including trauma experienced both in battle and as African Americans in the military.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture has objects in its collection relating to African Americans in the military from the American Revolution through the War on Terror, including several personal diaries and letters from the Civil War and World War I eras. Many of these diaries and letters have been transcribed by the public and are now searchable and easy to read online. Below are examples of some of these transcribed objects from the NMAAHC collection.

2nd Lt. John Freeman Shorter’s Civil War Diary

In 2016, volunteers in the Smithsonian Transcription Center transcribed a diary written by Civil War soldier John Freeman Shorter . This diary, written from January 1–September 30, 1865, details Shorter’s experiences as an African American soldier and officer during the final days of the Civil War. Shorter’s diary entries often focus on the weather, everyday activities, and his recuperation from a leg injury sustained during the Battle of Honey Hill. Other entries describe significant national and personal events such as the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and Shorter’s commissioning as a second lieutenant.

The rising sun betokens fair weather & a tolerable warm day. The Detail again left the Hospital & this time was more successful. taken with a chill in the morning & confined to bed all day. a report circulated that Maj Genl Sheridan had arrived at the Head also that arrangements were being made for peace. immediately. Lt. John Freeman Shorter, entry from April 21, 1865

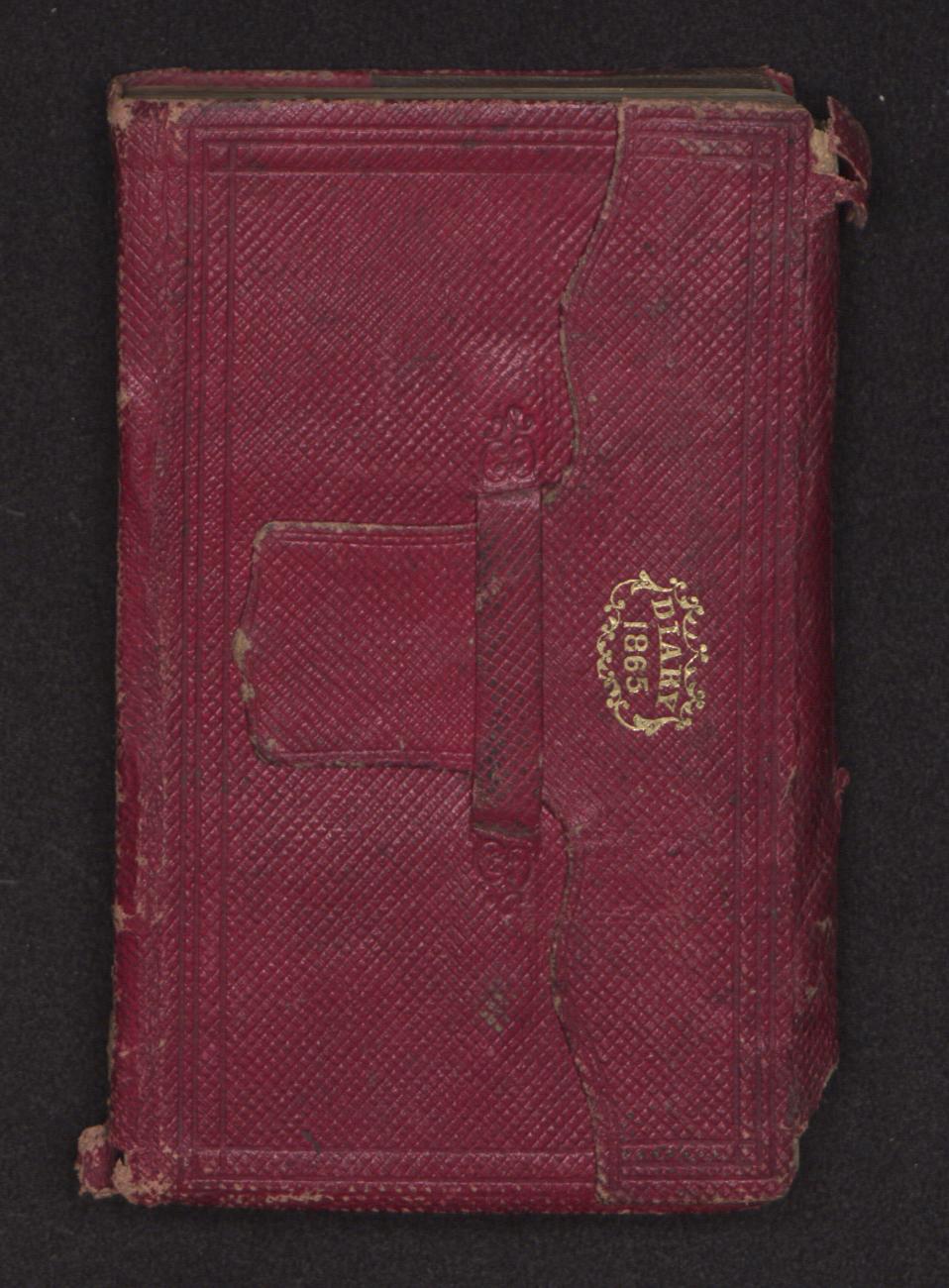

Diary of Lt. John Freeman Shorter, 1865.

2nd Lt. John Freeman Shorter (1842–1865) was a great-great-grandson of Elizabeth Hemings, the matriarch of the Hemings family enslaved at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Shorter was raised as a free man in Washington, D.C., before moving to Ohio. In 1863, he traveled to Boston to enlist in the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, one of the first African American volunteer regiments created after the enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation.

In March 1864, Shorter became the first enlisted soldier in the 55th Massachusetts to be promoted to the rank of an officer and one of only three fully commissioned black officers in the regiment. The other two black officers in the 55th Massachusetts were James Monroe Trotter and William H. Dupree. Despite their promotions, because of their race, the Army did not formally commission or recognize these three men as officers until the summer of 1865, after the war had ended. The chaplain of the 55th Massachusetts called Shorter, Trotter, and Dupree, “three as worthy men as ever carried a gun.”

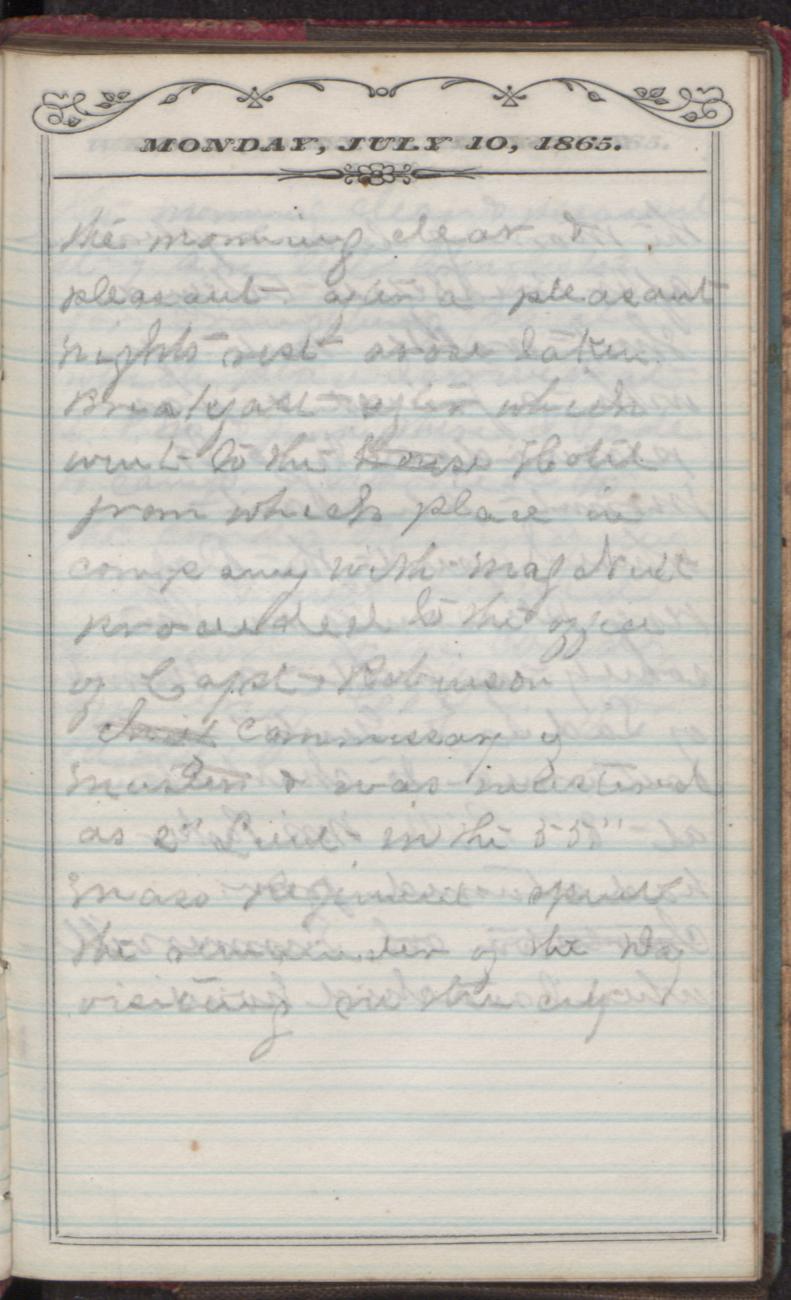

Entry from July 10, 1865:

the morning clear & pleasant after a pleasant nights rest arose taken Breakfast after which went to the Hotel from which place in company with Maj Nutt proceeded to the office of Capt Robinson Commissary of Musters & was mustered as 2nd Lieut in the 55" mass Regiment spent the remainder of the Day visiting in the city

View full transcription.

When the Massachusetts regiments were formed, African American soldiers were promised equal pay to that of all other soldiers. However, African American soldiers only received around half of the pay that their white counterparts received. Most soldiers in the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantries chose to forgo their pay until they were paid the same as their white counterparts. Shorter became a leader in the fight for equal pay and by October 1864 (almost eighteen months later) the War Department intervened, and the soldiers were provided full pay.

In November 1864, Lieutenant Shorter was “severely wounded in his right knee and hip by a musketball [sic]” during the Battle of Honey Hill and sent to a hospital. Although disabled by his leg wound, he stayed with his regiment throughout the remainder of the war. In August 1865, Shorter was honorably discharged and headed home to Ohio to marry his fiancé. Sadly, Shorter succumbed to smallpox, dying shortly before arriving home.

Entries from February 19–20, 1865, discussing the role of African American troops in capturing Charleston and Columbia, SC.

Entries from April 18–19, 1865, describing reports of the assassination of President Lincoln.

Entries from June 11–12, 1865, commenting on the weather and the disappointment in not receiving a letter from home.

Letters from Col. Charles Young to Sgt. Oscar W. Price

Mentorship is an important aspect for any young service member looking to advance in rank and obtain leadership positions in the military. For African Americans serving in the military in the early 20th century, the lack of black officers made finding these mentorship opportunities especially difficult. Sgt. Oscar W. Price found a mentor and friend in the highest-ranking African American officer of the era, Col. Charles Young.

In 2016, volunteers transcribed a series of letters that Young sent to Price , which highlight the support and advice that Young gave to Price as a young soldier looking to advance in the military. This collection of letters and documents also tells the story of Colonel Young, who was denied the command of troops during World War I due to health reasons and set out to prove to military leaders that he was, in fact, fit for duty.

Charles Young (1864–1922) was born enslaved in Kentucky in 1864. In 1889, he graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point, becoming the third African American—and last until 1936—to graduate from West Point. Throughout his career, Young served in the 9th U.S. Calvary; on the staff at Wilberforce University; as a major of the 9 th Ohio Infantry Regiment during the Spanish-American War; as superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant national parks; as a military attaché in Haiti and Liberia; and as a major in the 10 th U.S. Calvary during the 1916 Punitive Expedition, where he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

In 1917, Lt. Col. Charles Young was selected by a military board for promotion to colonel. As the highest-ranking African American Regular Army officer, many believed he would command troops when the United States entered the war and eventually become a general. However, Young was forced into retirement at the rank of lieutenant colonel because of a medical condition. Young spent the next year trying to prove that he was fit to command troops in battle. In June 1918, he rode 497 miles in 16 days on horseback from Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C., to prove his fitness. Young was eventually reinstated at the rank of colonel on November 6, 1918, five days before the armistice ending World War I.

Col. Charles Young as a cadet at West Point, 1889.

![black soldiers in the civil war essay Black typewritten text printed on yellowed paper, at the top is [ITINERARY OF COL. CHARLES YOUNG.] At the bottom is [Total number of miles 497. / Rest one day, trip 16 days. / Walked 15 min. out of each hr. / Average 31 miles.]](https://nmaahc.si.edu/sites/default/files/styles/max_1300x1300/public/images/captioned/2010_39_3_001_main.png?itok=Dc7gccZC)

Itinerary for Col. Charles Young’s trip from Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C., enclosed in a letter sent to Oscar Price on August 14, 1918.

View full transcription here.

Oscar Wendell Price (1893–1970) was born in Cedarville, Ohio. He attended nearby Wilberforce University where, in 1918, he became acquainted with Col. Charles Young, who after being forcibly retired was serving as the head of Wilberforce’s military science department. Price enlisted in the U.S. Army on October 18, 1917, and in early 1918 was training as a sergeant at Camp Sherman in Ohio.

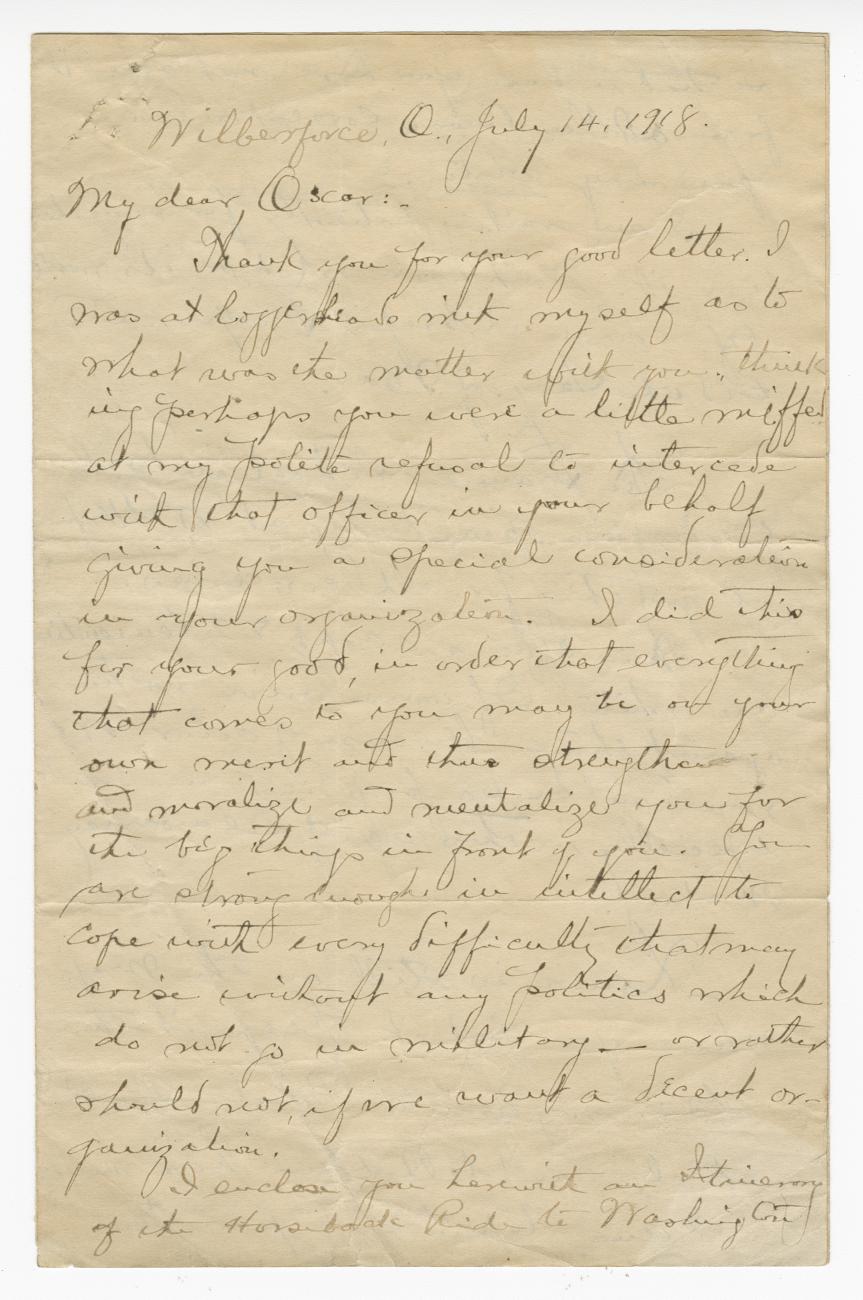

Price wanted to be an officer. He appealed to his friend and mentor, Young, to write a recommendation for him to attend Officer Training School. Young refused to write the recommendation stating in a letter on July 14, 1918, “I did this for your good, in order that everything that comes to you may be of your own merit and thus strengthen and moralize and neutralize you for the big things in front of you. You are strong enough in intellect to cope with every difficulty that may arise without any politics which do not go in military—or rather should not if we want a decent organization.”

Letter to Oscar W. Price from Colonel Charles Young, July 14, 1918, stating why Young wouldn’t write Price a letter of recommendation.

View full transcription here.

Price was eventually recommended for Officers’ Training School on his merits by the president of Wilberforce University. He attended Officers’ Training School at Camp Dodge, Iowa, and was commissioned a second lieutenant. Colonel Young’s letters kept by Lieutenant Price show how important the correspondence between the two men was from both a professional and personal standpoint.

Neither you nor anyother red-blooded black man wants to take an unfair advantage over our comrades in this goround. We want all that we have to come from merit, gain, hard work and the mercies of a good God. Col. Charles Young to Sgt. Oscar Price, August 14, 1918

Cpl. Roy Underwood Plummer’s World War I Diary

Roy Underwood Plummer (1896–1966) was born in Washington, D.C., and enlisted in the Army in 1917. After the war, Plummer returned to Washington, D.C., and graduated from Howard University School of Medicine in 1927. He practiced medicine in the District of Columbia for over 40 years.

Corporal Plummer served in Company C of the 506th Engineer Battalion. African American engineer battalions provided manual labor including the building of roads and railroads and construction of fortifications. The engineer battalions along with service/labor battalions, stevedore units, and pioneer infantry regiments were made up of approximately 160,000 African American soldiers serving as Services of Supply troops in France during the war. These Services of Supply units were essential to the war effort, allowing for the supply and movement of combat troops.

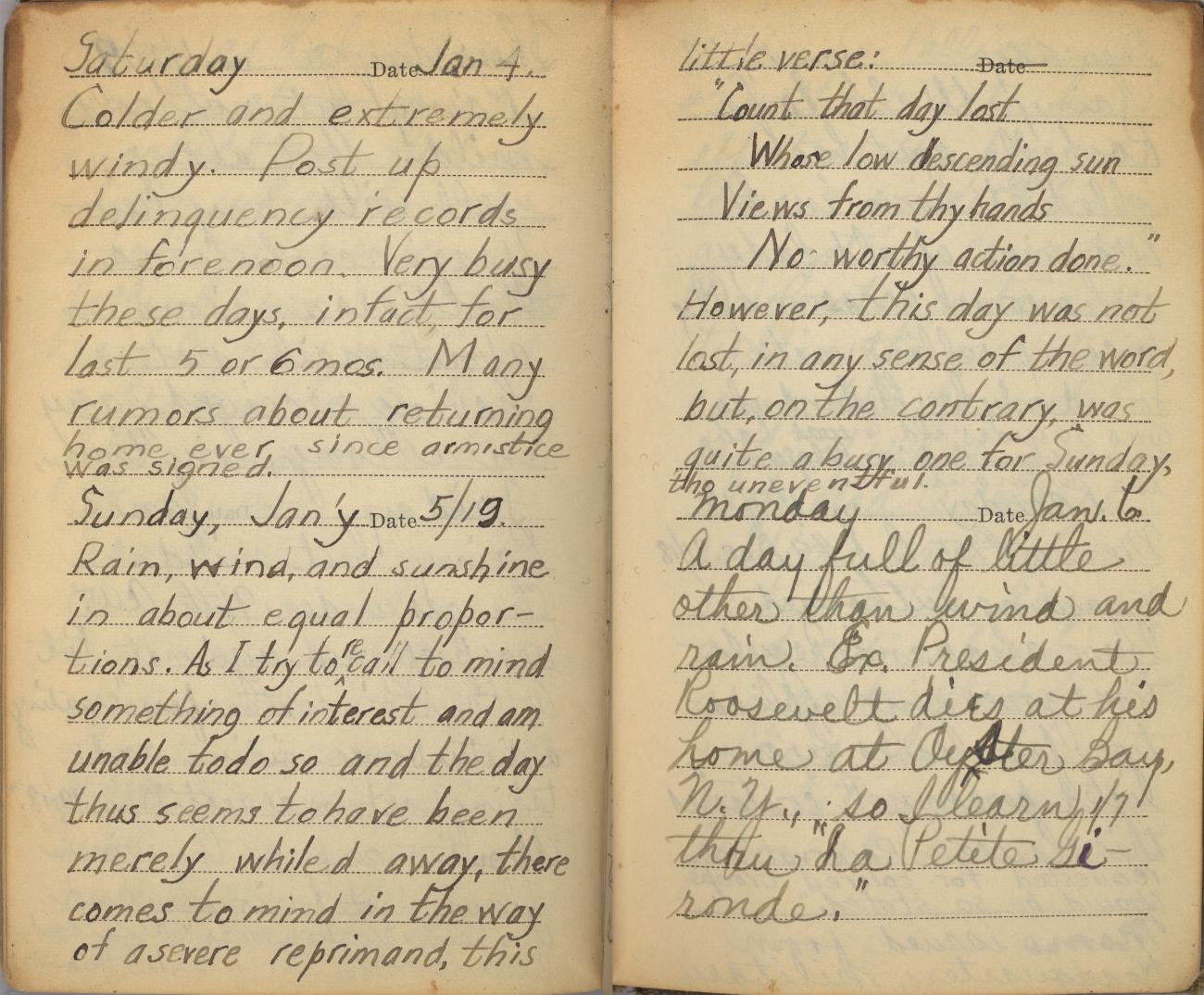

Diary entries for January 4–5, 1919, discussing “rumors about returning home,” a poem about a day being “whiled away,” and news of the death of former president Theodore Roosevelt.

Throughout the war, Plummer kept a diary ( view transcription ), which he received as a Christmas gift from his friend Albert L. Boddy in 1917. He began writing in it on December 15, 1917, just days before his regiment left for Europe. Plummer’s training as a clerk is evident throughout his diary and is shown through impeccable handwriting and clear descriptions of events and his surroundings. He regularly comments on various topics including the entertainment of troops, French citizens and towns, issues of race and violence perpetrated against African American soldiers in Europe, and even the impact of the Spanish Influenza of 1919 on his unit.

Still cold, and the epidemic still spreading, especially in Company “A.” Our company dons “Flu” masks as a preventive measure. Cpl. Roy Plummer writing in his diary about the Spanish Influenza, January 24, 1919

Plummer’s first diary entry, mentioning his selection as squad leader, December 15, 1917.

Entry from July 14, 1918, recounting a French Independence Day celebration.

Entry from September 30, 1918, noting that the "Epidemic of Spanish Influenza has been raging."

Entry from December 19, 1918, discussing “friction between the races.”

Entry from January 24, 1919, discussing the Spanish Influenza.

Whether written in a camp, barracks, hospital, or even a trench, diaries and letters provide first-hand accounts of historic events and give glimpses into the military and social culture of the time. However, many of these records are difficult to read and decipher and are not searchable online. Through transcription these records are now searchable, readable, and easily available to students, researchers, and anyone with a desire to learn more about the African American military experience.

Browse Documents and Diaries in the NMAAHC Collection Relating to African Americans in the Military

Written by Douglas Remley, Rights & Reproductions Specialist Published on May 18, 2020

We Return Fighting: The African American Experience in World War I

Lt. John Freeman Shorter

- Biography of John Freeman Shorter

- History of the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment

- Objects relating to the 55th Massachusetts Infantry in the NMAAHC collection

Col. Charles Young

- Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument in Wilberforce, Ohio

- Objects relating to Col. Charles Young in the NMAAHC collection

Cpl. Roy Underwood Plummer

- "Uncovering History, Day by Day" by Sue Anne Pressley. Washington Post. June 14, 2004.

- Combat and Construction: U.S. Army Engineers in World War I by Charles Hendricks. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 1993.

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- Exhibitions Home

- Current Exhibitions

- All Exhibitions

- Loan Procedures for Institutions

- Special Presentations

The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship The Civil War

Abraham Lincoln's election led to secession and secession to war. When the Union soldiers entered the South, thousands of African Americans fled from their owners to Union camps. The Union officers did not immediately receive an official order on how to manage this addition to their numbers. Some sought to return the slaves to their owners, but others kept the blacks within their lines and dubbed them “contraband of war.” Many “contrabands” greatly aided the war effort with their labor.

After Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which was effective on January 1, 1863, black soldiers were officially allowed to participate in the war. The Library of Congress holds histories and pictures of most of the regiments of the United States Colored Troops as well as manuscript and published accounts by African American soldiers and their white officers, documenting their participation in the successful Union effort. Both blacks and whites were outspoken about questions of race, civil rights, and full equality for the newly-freed population during the Civil War era.

Emancipated blacks were forced to begin their trek to full equality without the aid of “forty acres and a mule,” which many believed had been promised to them. The Library's collection records the new steps towards freedom on the part of the African American community, especially in the areas of employment, education, and politics. There is also an abundance of books, photographs, diaries, and manuscripts about many aspects of slave life and culture, such as the development of the “Negro Spiritual” and the role played by the United States Colored Troops in the South and the West.

“Contrabands of War”

A clergyman's diary on the eve of the civil war.

A.M.E. Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner, father of painter Henry Ossawa Tanner, was an important church leader in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In this diary he foresees with amazing accuracy some of the problems the nation would face in the upcoming Civil War. Its pages discuss the election of Abraham Lincoln, South Carolina's deliberations about secession, and the emerging war fervor.

Benjamin Tucker Tanner (A.M.E. bishop). Diary, 1860-1861. Holograph manuscript. Carter G. Woodson Papers, Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (4–12)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj1

“Contraband of War”—African American Fugitives To Union Lines

As Union armies moved into the South, thousands of slaves fled to their camps. Although some Union officers sent them back to their masters, others allowed them to remain with their troops, using them as a work force and dubbing them “contraband of war.”

Of this sketch, Waud, who photographed the “contrabands” and then prepared the drawing for the newspaper, wrote:

There is something very touching in seeing these poor people coming into camp—giving up all the little ties that cluster about home, such as it is in slavery, and trustfully throwing themselves on the mercy of the Yankees, in the hope of getting permission to own themselves and keep their children from the auction-block. This party evidently comprises a whole family from some farm . . . .

Alfred R. Waud. Contrabands Coming into Camp . Drawing. Chinese white on brown paper. Published in Harper's Weekly , January 31, 1863. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-6173/LC-USZ62-14189 (4–1)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj2

To Union Lines and Freedom

Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, this is an image of African Americans seeking to gain freedom behind Union lines. It was taken in the main eastern theater of the war during the second battle of Bull Run in 1862.

Timothy O'Sullivan. Fugitive African Americans Fording the Rappahannock River . Rappahannock, Virginia, August 1862. Copyprint. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-B8171-518 (4–4)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj3

“Contrabands” at the Nation's Capitol

Black slaves who fled to Union lines, or “contrabands,” often proved themselves extremely useful, even before the government enlisted them into service. A group of “contrabands” appear on this calling card. Calling cards, or cartes de visite, with photographs were popular during this era partly because photography was relatively new and the cards provided a means of sharing likenesses with friends and relatives. This one includes images of white officers of the 2nd Rhode Island Camp at Camp Brightwood in the District of Columbia. On the left is Capt. B. S. Brown. In the center is Lt. John P. Shaw, killed in action at the Wilderness, Virginia, May 5, 1864, and on the right is Lt. T. Fry. The “contrabands” with them are not named.

Contrabands, Camp Brightwood . Washington, D.C., ca. 1863. Carte de visite. Gladstone Collection, Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-6158 (4–9)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj4

Back to top

The Emancipation Proclamation

Lincoln's proclamation.

This print is based on David Gilmore Blythe's painting of Lincoln writing the Emancipation Proclamation. Blythe imagined the President in a cluttered study at work on the document near an open window draped with a flag. His left hand is placed on a Bible that rests on a copy of the Constitution in his lap. The scales of justice appear in the left corner, and a railsplitter's maul lies on the floor at Lincoln's feet.

After David G. Blythe. President Lincoln Writing the Proclamation of Freedom, January 1, 1863 . Cincinnati: Ehrgott and Forbriger, 1864. Lithograph. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-1425 (4–22)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj5

Freedom's Eve—Watch Night Meeting

On New Year's Eve many African American churches hold prayer and worship services from the late evening until midnight when they welcome the new year with praise, thanksgiving, prayer, and confession. These services are called watch night meetings. December 31, 1862, was a very special evening for the African American community, because it was the night before the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, freeing all the slaves in the Confederate states.

Heard and Moseley. Waiting for the hour [Emancipation], December 31, 1862 . Carte de visite. Washington, 1863. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-6160 (4–21a)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj6

Soldiers and Missionaries

29th regiment from connecticut.

African American volunteers were in readiness to serve in the Civil War when the Union called them. President Lincoln and Union leaders vacillated greatly on the question of the abolition of slavery and the employment of black troops. The Emancipation Proclamation put an end to these questions. Effective January 1, 1863, the Proclamation emancipated Confederate slaves and authorized the use of black soldiers by Union troops. By the end of the war about 186,000 African American men had enlisted.

29th Regiment from Connecticut at Beaufort, S.C. , 1864. Attributed to Sam A. Cooley. Copyprint. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-B82201-341 (4–5)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj7

Frederick Douglass—Recruiter Of Colored Troops

This letter, addressed to Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York, states:

Sir, I am instructed by the Secretary of War to direct you to proceed to Vicksburg, Mississippi, and on your arrival there to report in person to Brig'r General L. Thomas, Adjutant General, U. S. Army, to assist in recruiting colored troops.

Douglass served as a recruiter in several regions of the country.

C. W. Foster, U.S. War Department, to Frederick Douglass, August 13, 1863. Manuscript letter. Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (4–16)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj8

Douglass Recruits—His Sons Charles and Lewis

Among those Frederick Douglass recruited were his own sons, Charles and Lewis. Both enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts regiment. Charles, who wrote this letter from Camp Meigs in Readville, Massachusetts, relates an encounter with an Irishman while he was rejoicing over “the news that Meade had whipped the rebels [at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania].” Before a fight could begin between young Douglass and the heckler, a policeman led the Irishman away.

A letter from Charles Douglass (son) to Frederick Douglass, July 6, 1863. Frederick Douglass Papers, Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (4–17)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj9

Fighting for Freedom

His truth is marching on.

Julia Ward Howe, a white abolitionist, felt that there should be more positive lyrics to the tune of “John Brown's Body Lies A Moldering in the Grave,” so she wrote the words to the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” to be used with the same tune. Howe's hus band had entertained John Brown in their home. The Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments published this broadside with the lyrics.

Julia Ward Howe. “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Published by the Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments. Broadside. Rare Book and Special Collections Division , Library of Congress (4–20)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj10

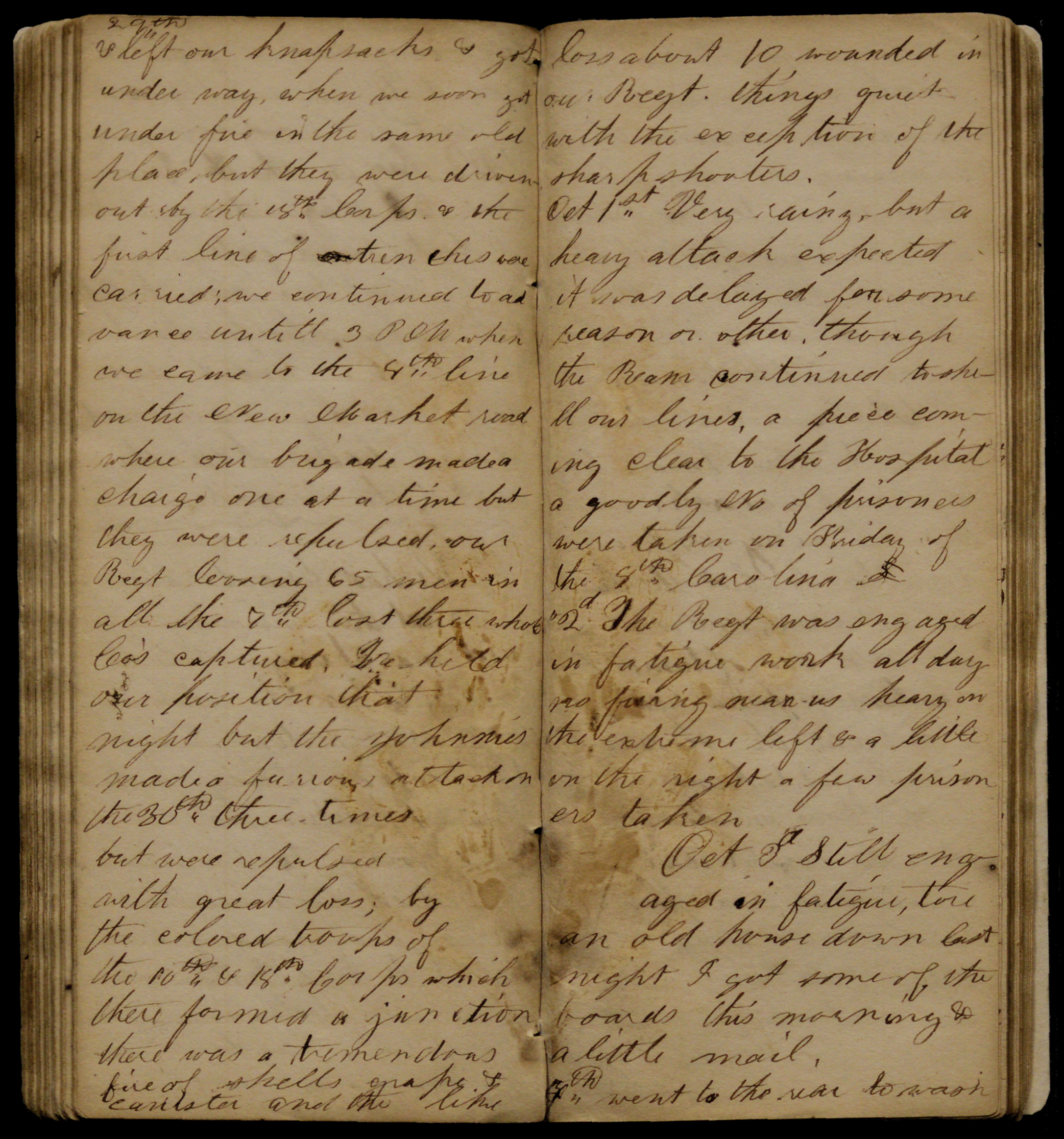

An African American Medal of Honor Winner

These pages of Christian Fleetwood's diary detail his actions during a battle at Chaffin's farm near Richmond, Virginia, on September 29, 1864, which led to his receipt of the Congressional Medal of Honor. Fleetwood was one of fourteen African American men who received the medal for meritorious service during the war.

Fleetwood's regiment, the 4th U. S. Colored Infantry, saw action in Virginia. His diary also documents North Carolina campaigns and President Lincoln's visit to the front lines in June 1864.

Christian A. Fleetwood. Diary, September 24, 1864. Holograph manuscript. Christian A. Fleetwood Papers, Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (4–14)

Christian A. Fleetwood in uniform. Albumen print, carte de visite, 1884. Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (4–15)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj11

U.S. Colored Troops—Flags

In many of the stylized images of African Americans during the 1800s, freedom and justice are personified as a statuesque white woman in flowing robes. Behind the soldier in this image, liberated slaves are celebrating his accomplishments.

Regimental flags of the 6th U.S. Colored Troops . Carte de visite. Gladstone Collection, Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-6156 (4–7)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj12

U.S. Colored Troops—Wounded in Action

Although the United States Colored Troops did not see as much action as many of them wanted to, they did participate in many skirmishes and major battles. After an unspecified battle in Virginia, probably in 1864, these wounded soldiers recuperated at Aikens Landing, a site used mainly for supplies. Taunted by many detractors, African American soldiers were eager to demonstrate that they could be courageous under fire. Despite problems getting paid, lower wages than white soldiers when they finally were paid, segregated units, and high ranks for whites only, the U.S. Colored Troops displayed a tenacious loyalty to the Union cause.

Wounded Colored Troops at Aikens Landing . Stereograph. Gladstone Collection, Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-6157 (4–8)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj13

African Americans at Sea

This stereograph shows an African American, one of thousands of blacks who served at sea during the Civil War. The most famous of these was the Honorable Robert Smalls, later a Reconstruction congressman, who became the captain of a Confederate vessel that he commandeered and sailed into Union lines. Service records for over eighteen thousand African American Civil War seamen have now been identified by the Naval Historical Center at the Washington, D. C., Navy Yard.

Unidentified sailor . Carte de visite. Gladstone Collection, Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-6159 (4–10)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj14

Emancipation Celebration

The District of Columbia Emancipation Act, passed on April 19, 1862, abolished slavery in the nation's capital and provided up to $300 compensation to owners for each freed slave. The African American population in the District regularly celebrated this Emancipation Day with bands, parades, sermons and speeches.

This illustration from Harper's Weekly depicts the fourth anniversary of the District's Emancipation Act. On April 19, 1866, African American citizens of Washington, D.C., staged a huge celebration. Approximately 5,000 people marched up Pennsylvania Avenue, past 10,000 cheering spectators, to Franklin Square for religious services and speeches by prominent politicians. Two of the many black regiments that had gained distinction in the Civil War led the procession.

F. Deilman. Celebration of the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, by the colored people in Washington, April 19, 1866 . Wood engraving. From Harper's Weekly, May 12, 1866. Copyprint. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-33937 (4–11)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj15

Forever Free

The Emancipation Proclamation declared that all slaves in the Confederate states were “forever free.” Free blacks, forming their own communities even during the slavery era, owned homes, businesses, and churches like this one. This group of African Americans is standing before a church on Broad Street in Richmond after the city was taken by Union soldiers in 1865.

First African Church, Broad Street . Richmond, Virginia, 1865. Copyprint. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-B8171-3368 (4–3)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj16

“Behold the Shackles Fall”

Sojourner truth ministers to the colored troops.

Abolitionist and orator Sojourner Truth, who was illiterate, engaged her friend Euphemia Cockrane to write this letter to Mary R. Gale. Truth explains that she is communicating from Detroit, because she traveled there from Battle Creek to bring a donatio n of “good things” from the people of Michigan to the African American troops.

Truth states that when warmer weather comes she will go to visit the freedmen. She exults that “This is a great and glorious day!” and continues:

It is good to live in it & behold the shackles fall from the manacled limbs. Oh if I were ten years younger I would go down with these soldiers here & be the Mother of the Regiment!

Sojourner Truth (written by Cockrane) to Mary Gale, February 25, 1864. Letter concerning the emancipation of her children and her son's Civil War service. Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (4–13)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj17

The Spirituals: Early Publication

The long journey of the African American spiritual begins in slavery. It first emerges into print during the Civil War, when “contrabands” sang their songs to Northern musicians who transcribed and harmonized the melodies. “Down in the Lonesome Valley” and “Go Down, Moses” were two of the spirituals actually published with music during the Civil War. The sheet music for “Down in the Lonesome Valley” published four verses of the song as sung by the freedmen of Port Royal, with some additions written by the compiler. Through publication, the spiritual had already begun its journey from being a purely African American genre to a musical form appreciated by a wide audience.

"Down in the Lonesome Valley: A Shout Song of the Freedmen of Port Royal." Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1864. Music Division , Library of Congress (4–18)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj18

U.S. Colored Troops—Band

This view of the defenses of the Washington, D. C., area shows a group of twenty African American soldiers with musical instruments. Blacks served in various capacities in the Union army. At first Union leaders allowed no black men to be commissioned officers, but eventually they served as noncommissioned officers, doctors, and chaplains. The first African American field officer was Major Martin Delany.

107th U.S. Colored Infantry Band at Fort Corcoran . Arlington, Virginia, November 1865. Copyprint. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-B8171-7861 (4–6)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj19

Civil War Map of Virginia's Lower Peninsula

Prepared by Confederate engineers under the direction of Capt. Albert H. Campbell, this 1864 field map provides detailed geographic information about Richmond, Virginia, and vicinity, including that portion of the Lower Peninsula as far east as Williamsburg. Although this map's primary purpose was documenting military reconnaissance (especially topography), the transportation network, and fortifications, it also provides detailed information about the cultural settlement patterns. The most obvious settlement features depicted are the numerous plantations and farms. Depictions of these plantations include notations indicating the location of “quarters” and “overseer.” But more remarkable are numerous references to free black settlements.

Albert H. Campbell. Map of the Vicinity of Richmond and Part of the Peninsula . Department of Northern Virginia, Topographical Department, 1864. Baltimore: T. Swell Ball, 1891. Photolithograph facsimile reproduction. Geography and Map Division , Library of Congress (4–19)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj20

United States Colored Troops

Not until after the Emancipation Proclamation was in force as of January 1, 1863, did Union officers actively recruit African American soldiers, although some black men were unofficially part of segregated units in a few states. By the end of the Civil War, one out of every eight Union soldiers was a black man. This image is symbolic because the soldiers stand in front of a location where black slaves were held for auction, stripped, examined, and bought and sold before interested purchasers.

William R. Pywell. Slave Pen in Alexandria, Va . [1862]. Copyprint. Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-B8171-2296 (4–2)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/civil-war.html#obj21

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

Meet the 2024 History Teachers of the Year!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

A Black Soldier’s Civil War Diary

Posted by on wednesday, 02/10/2016.

Written by Stephanie Townrow and Mary Kate Kwasnik.

William Woodlin enlisted in the United States Colored Infantry 8th Regiment in October 1863 and kept a journal during his service. Woodlin’s entries describe camp life, his service with the regimental band as a horn player, several battles, the weather, equal pay with White soldiers, and the famous 54th Massachusetts Regiment, among many other topics.

In October 1864, Woodlin describes the bravery of Black troops in the Siege of Petersburg, Virginia, reporting that “the johnnies made furious attack on the 30th three times but were repulsed with great loss by the Colored troops of the 10th and 18th Corps . . . there was a tremendous fire of shells, grape and canister and the like.”

Listen to a reading of this excerpt from Woodlin’s diary:

Woodlin’s diary is one of the Gilder Lehrman Collection’s most unique resources because it gives us an idea of what Union service was like for an African American soldier in his own words. From the dullness of everyday camp chores to the hurried retelling of battles and skirmishes, Woodlin’s words describe the war in a way that essays or historians cannot. The Gilder Lehrman Institute has used the diary in a number of digital projects, including exhibitions on Abraham Lincoln , African Americans in the Military , and the Civil War .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Home — Essay Samples — History — Civil War — African Americans during the Civil War

African Americans During The Civil War

- Categories: African American American History Civil War

About this sample

Words: 1197 |

Published: Nov 19, 2018

Words: 1197 | Pages: 3 | 6 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1060 words

3 pages / 1536 words

3 pages / 1526 words

3 pages / 1286 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Civil War

The aftermath of the American Civil War was intended to be a time of hope and unity. As both the North and South had the opportunity to recover from the colossal casualties caused by the war, there was huge political pressure to [...]

The Civil War, fought between 1861 and 1865, was a defining moment in American history. Understanding the causes of this conflict is crucial for comprehending the development of the United States as a nation. This essay will [...]

The Civil War, which took place from 1861 to 1865, is a pivotal event in American history that significantly shaped American society and solidified the national identity of the United States. While the primary cause of the war [...]

Harriet Tubman's greatest achievement lies in her ability to inspire hope and instill a sense of agency in those who had been stripped of their humanity by the institution of slavery. Her unwavering commitment to freedom and [...]

“War is what happens when language fails” said Margaret Atwood. Throughout history and beyond, war has been contemplated differently form one nation to another, or even, one person to another. While some people believe in what [...]

When Confederate General Robert Lee E. announced his formal surrender more than 150 years ago, the Civil War was brought to an end. Preoccupied with the challenges of the present moment, America citizens will continue to place [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.