How the quality of school lunch affects students’ academic performance

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, michael l. anderson , mla michael l. anderson associate professor of agricultural and resource economics - university of california, berkeley justin gallagher , and jg justin gallagher assistant professor of economics - case western reserve university elizabeth ramirez ritchie err elizabeth ramirez ritchie ph.d. graduate student - university of california-berkeley, department of agricultural and resource economics.

May 3, 2017

In 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. The main goal of the law was to raise the minimum nutritional standards for public school lunches served as part of the National School Lunch Program. The policy discussion surrounding the new law centered on the underlying health reasons for offering more nutritious school lunches, in particular, concern over the number of children who are overweight. The Centers for Disease Control estimates that one in five children in the United States is obese.

Surprisingly, the debate over the new law involved very little discussion as to whether providing a more nutritious school lunch could improve student learning. A lengthy medical literature examines the link between diet and cognitive development, and diet and cognitive function. The medical literature focuses on the biological and chemical mechanisms regarding how specific nutrients and compounds are thought to affect physical development (e.g., sight), cognition (e.g., concentration, memory), and behavior (e.g., hyperactivity). Nevertheless, what is lacking in the medical literature is direct evidence on how nutrition impacts educational achievement.

We attempt to fill this gap in a new study that measures the effect of offering healthier public school lunches on end of year academic test scores for public school students in California. The study period covers five academic years (2008-2009 to 2012-2013) and includes all public schools in the state that report test scores (about 9,700 schools, mostly elementary and middle schools). Rather than focus on changes in national nutrition standards, we instead focus on school-specific differences in lunch quality over time. Specifically, we take advantage of the fact that schools can choose to contract with private companies of varying nutritional quality to prepare the school lunches. About 12 percent of California public schools contract with a private lunch company during our study period. School employees completely prepare the meals in-house for 88 percent of the schools.

To determine the quality of different private companies, nutritionists at the Nutrition Policy Institute analyzed the school lunch menus offered by each company. The nutritional quality of the menus was scored using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI). The HEI is a continuous score ranging from zero to 100 that uses a well-established food component analysis to determine how well food offerings (or diets) match the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The HEI is the Department of Agriculture’s preferred measure of diet quality, and the agency uses it to “examine relationships between diet and health-related outcomes, and to assess the quality of food assistance packages, menus, and the US food supply.” The average HEI score for the U.S. population is 63.8, while the median HEI score in our study is 59.9. In other words, the typical private company providing public school lunch in CA is a bit less healthy than the average American diet.

We measure the relationship between having a lunch prepared by a standard (below median HEI) or healthy (above median HEI) company relative to in-house preparation by school staff. Our model estimates the effect of lunch quality on student achievement using year-to-year changes between in-house preparation of school meals and outside vendors of varying menu quality, within a given school . We control for grade, school, and year factors, as well as specific student and school characteristics including race, English learner, low family income, school budget, and student-to-teacher ratios.

We find that in years when a school contracts with a healthy lunch company, students at the school score better on end-of-year academic tests. On average, student test scores are 0.03 to 0.04 standard deviations higher (about 4 percentile points). Not only that, the test score increases are about 40 percent larger for students who qualify for reduced-price or free school lunches. These students are also the ones who are most likely to eat the school lunches.

Moreover, we find no evidence that contracting with a private company to provide healthier meals changes the number of school lunches sold. This is important for two reasons. First, it reinforces our conclusion that the test score improvements we measure are being driven by differences in food quality, and not food quantity. A number of recent studies have shown that providing (potentially) hungry kids with greater access to food through the National School Lunch Program can lead to improved test scores. We are among the very few studies to focus on quality, rather than food quantity (i.e., calories). Second, some critics of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act worried that by raising the nutritional standards of school lunches that fewer children would eat the food, thereby unintentionally harming the students that the law was designed to help. Our results provide some reassurance that this is not likely to be the case.

Finally, we also examine whether healthier school lunches lead to a reduction in the number of overweight students. We follow previous literature and use whether a student’s body composition (i.e. body fat) is measured to be outside the healthy zone on the Presidential Fitness Test . We find no evidence that having a healthier school lunch reduces the number of overweight students. There are a few possible interpretations of this finding, including that a longer time period may be necessary to observe improvements in health, the measure of overweight is too imprecise, or that students are eating the same amount of calories due to National School Lunch Program calorie meal targets.

Education researchers have emphasized the need and opportunity for cost-effective education policies . While the test score improvements are modest in size, providing healthier school lunches is potentially a very cost-effective way for a school to improve student learning. Using actual meal contract bid information we estimate that it costs approximately an additional $80 per student per year to contract with one of the healthy school lunch providers relative to preparing the meals completely in-house.

While this may seem expensive at first, compare the cost-effectiveness of our estimated test score changes with other policies. A common benchmark is the Tennessee Star experiment , which found a large reduction in the class size of grades K-3 by one-third correlated with a 0.22 standard deviation test score increase. This reduction cost over $2,000 when the study was published in 1999, and would be even more today. It is (rightfully) expensive to hire more teachers, but scaling this benefit-cost ratio to achieve a bump in student learning gains equal to our estimates, we find class-size increases would be at least five times more expensive than healthier lunches.

Thus, increasing the nutritional quality of school meals appears to be a promising, cost-effective way to improve student learning. The value of providing healthier public school lunches is true even without accounting for the potential short- and long-term health benefits, such as a reduction in childhood obesity and the development of healthier lifelong eating habits. Our results cast doubt on the wisdom of the recently announced proposal by Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue to roll back some of the school lunch health requirements implemented as part of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act.

Related Content

Krista Ruffini

February 11, 2021

Lauren Bauer, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach

April 29, 2016

Michele Leardo

August 29, 2016

Education Access & Equity K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Adam Looney, Constantine Yannelis

September 17, 2024

Brad Olsen, Molly Curtiss Wyss, Maya Elliott

September 16, 2024

Magdalena Rodríguez Romero

September 10, 2024

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Public Health Nutrition

- > Volume 20 Issue 9

- > School lunches in Japan: their contribution to healthier...

Article contents

- Conclusions

Materials and methods

Supplementary material, school lunches in japan: their contribution to healthier nutrient intake among elementary-school and junior high-school children.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 March 2017

- Supplementary materials

The role of school lunches in diet quality has not been well studied. Here, we aimed to determine the contribution of school lunches to overall nutrient intake in Japanese schoolchildren.

The study was conducted nationwide under a cross-sectional design. A non-consecutive, three-day diet record was performed on two school days and a non-school day separately. The prevalence of inadequate nutrient intake was estimated for intakes on one of the school days and the non-school day, and for daily habitual intake estimated by the best-power method. The relationship between food intake and nutrient intake adequacy was examined.

Fourteen elementary and thirteen junior high schools in Japan.

Elementary-school children ( n 629) and junior high-school children ( n 281).

Intakes between the school and non-school days were significantly different for ≥60 % of nutrients. Almost all inadequacies were more prevalent on the non-school day. Regarding habitual intake, a high prevalence of inadequacy was observed for fat (29·9–47·7 %), dietary fibre (18·1–76·1 %) and salt (97·0–100 %). Inadequate habitual intake of vitamins and minerals (except Na) was infrequent in elementary-school children, but was observed in junior high-school children, particularly boys.

School lunches appear to improve total diet quality, particularly intake of most vitamins and minerals in Japanese children. However, excess intakes of fat and salt and insufficient intake of dietary fibre were major problems in this population. The contribution of school lunches to improving the intakes of these three nutrients was considered insufficient.

Diet is closely associated with growth in children ( Reference Emmett and Jones 1 ) and an unfavourable dietary intake in childhood causes several non-communicable diseases ( Reference Kaikkonen, Mikkila and Raitakari 2 ) in adulthood. Improving the quality of children’s diet is therefore a critical public health issue with lifelong benefits.

Many countries have implemented school lunch programmes, based on the idea that these can be an effective intervention for better dietary intake among children ( Reference Stallings and West Suitor 3 , Reference Adamson, Spence and Reed 4 ) . School lunches in Japan have a history of more than 100 years, with the first provided in 1889 at a private elementary school in Yamagata Prefecture ( 5 ) . This programme was recorded as relief work for children in poverty by Buddhists. The Ministry of Education began the financial subsidization of school lunches in 1932 and efforts to provide foods for as many children as possible were continued even in World War II. The nutritional status of schoolchildren just after the war was severely downgraded, and the nationwide school lunch programme was restarted in 1947 with relief supplies from the Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia, UNICEF and others. Today, school lunches are provided in 99·2 % of elementary schools and 87·9 % of junior high schools in Japan (data from Gakkou Kyushoku Jissi Jyoukyou tou Chousa (Survey for the School Lunch Program) by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2014) based on the School Lunch Act. The mean monthly cost of school lunches in 2014 was approximately 4300 Japanese yen ($US 39·1; $US 1=110 JP¥) for children in public elementary schools and 4882 Japanese yen ($US 44·4) for those in public junior high schools. Low-income families can receive financial support for school lunches from the local or national government.

Under the Japanese programme, the same lunch menu is provided to all children of a school, including a staple food, main dish, side dish, drink and dessert (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Fig. 1), except for special cases such as children with food allergy. This fixed menu is a unique characteristic of Japanese school lunches, because the same menu, including ‘healthy’ foods such as vegetables or fruits, are mandatorily provided to all the children in the school and no choices (e.g. to choose only pizza and French fries at a cafeteria) are permitted. Children are taught not to leave any food on their plate and the percentage of waste food is 6·9 % on average (survey on food loss in school lunches, performed by the Ministry of the Environment, 2014). Since the nutrient content of school lunches is regulated by the Gakkou Kyushoku Jissi Kijyun (Standards for the School Lunch Program), the provision of school lunches has likely improved the overall nutrient intakes of Japanese children. However, this beneficial aspect of school lunches has not been evaluated in detail.

Here, to demonstrate the contribution of school lunches to healthier nutrient intake in Japanese children, we first evaluated the difference in nutrient intake on school days and non-school days in elementary-school and junior high-school children. To clarify the problem of overall nutrient intake in this generation, we then estimated the habitual nutrient intake. Finally, we also estimated the total adequacy of nutrient intake and its relationship with food intake.

Study participants

Recruitment of study participants was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and the local boards of education at both the prefectural and municipal level. Twelve prefectures (Aomori, Yamagata, Ibaraki, Tochigi, Toyama, Shiga, Shimane, Ehime, Kochi, Fukuoka, Saga and Kagoshima) were chosen as study areas in consideration of geographical condition (e.g. north or south, rural or urban) and study feasibility. Schools with experienced nutrition teachers (dietitians) were selected for the study and these dietitians supported the dietary assessment. The unit of recruitment was the class, with a minimum of thirty students. From each area, ninety children (thirty children in each of third and fifth grade in elementary school and thirty children in second grade in junior high school) on average were recruited by teachers in the schools. When a class contained fewer than thirty students, an additional class (or school) was recruited. All children in classes selected for the survey received a written document to explain the survey and recording sheets for the diet record. Finally, a total of 1190 children (389 third graders and 392 fifth graders from fourteen elementary schools, and 409 second graders from thirteen junior high schools) were recruited.

Semi-weighed diet record

Study items in the present study were dietary assessment by diet record (DR) and measurement of height and weight at school. Each school set the period for the non-consecutive, three-day DR and conducted the measurement of height and weight within one month of that period. All records were collected by the study centre at the researcher’s university and checked by the researchers, who confirmed any unclear points with the participating children and/or their guardians through the schools. The dietitians or teachers who managed the survey at each school had a correspondence table which linked the children’s names and identification numbers for the survey, but the researchers did not have access to this information.

Guardians of the participating children were asked to complete a three-day, non-consecutive DR of their children’s dietary intake, of whom 915 complied (participation rate: 76·9 %). The three recording days for the DR consisted of two school days with a school lunch and one weekend day without a school lunch all within the same week (e.g. Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday within one week). Initially, each school set two survey days for the recording of school lunches in November or December 2014. Days without special events were chosen for the survey. These two days and one weekend day were also set as the survey days for dietary intake at home. The participants were able to choose either a Saturday or Sunday, again without special plans, as survey day according to their private schedule.

Dietary intake from the school lunch was recorded as follows. Before cooking, the dietitians at the school weighed all ingredients in all dishes for the participating children. They then measured the total weight of the cooked foods within each bulk cooking pot before serving. Using weights before and after cooking, the dietitians prepared conversion charts to estimate the weight of each ingredient consumed by a participating child from the weight of the cooked dish actually consumed by that child, with the weight of cooked foods consumed by each child measured in the classroom by a dietitian or the child under the dietitian’s support with a cooking scale. Beverages and processed foods provided without cooking were weighed in the same manner. Leftover food for each child was weighed after the lunch to estimate the net weight of consumed foods.

Dietary intake at home was recorded by the guardian who was the main preparer of meals for the participating child. All foods and beverages consumed out of school were recorded on the same two days set for the school lunch survey and also on the one weekend (non-school) day. The guardians were provided a manual for the DR and recording sheets. The school dietitians explained the recording methods to the guardians and supported them throughout the survey. The guardians weighed the ingredients in dishes, in the prepared dishes after cooking and in all drinks, whenever possible. If participants ate out and weighing was difficult, they recorded the restaurant’s name, name of dishes and whether any food was left uneaten. The main items recorded on the DR sheets were: (i) names of dishes; (ii) names of foods and any ingredients in dishes; (iii) approximate amount of foods consumed (amount measured by measuring spoon or measuring cup, or number of consumed foods (e.g. two strawberries)); (iv) measured weight of each ingredient, food and/or dish; and (v) whether the meal was consumed under usual conditions or at a special event. In addition, the guardians were asked to submit the packaging of processed foods or snacks with the recording sheet for estimation of ingredients.

The recording sheets for each survey day were handed directly to the school dietitian immediately after recording and then checked by the school dietitian as soon as possible. If missing or unclear information was recorded by a guardian, the research dietitian questioned the guardian directly. After this confirmation process, food item numbers ( 6 ) were assigned to all recorded foods and beverages, and if necessary, consumed weight was estimated as precisely as possible utilizing the information recorded for the approximate amount of food, website of the restaurant or manufacturer, or nutrition facts on the food package. Recorded food items and weights were then reconfirmed by two research dietitians at the central office of the study. The weight of each food and ingredient included in the school lunch was estimated at the office based on the weight of consumed dishes and the conversion charts prepared by the school dietitians. The data for the lunch and the other meals were combined and the nutritional values were calculated. All calculations were performed with the statistical software package SAS version 9.4.

Other measurements

Body height and weight were measured to the nearest 0·1 cm and 0·1 kg, respectively, with the child wearing light clothing and no shoes. Measurement was done for the present study or as part of a routine health check-up by school nurses at each school. The prevalence of obesity in the children was evaluated by percentage of excess weight, which is defined using the formula: [(actual weight – standard weight)/standard weight]×100 (%). If percentage of excess weight was ≥20 %, the child was categorized as overweight, and if ≤−20 %, he/she was categorized as underweight. The standard weight was calculated using age- and sex-specific formulas which included actual height and coefficients ( Reference Ikiuo (Sawamura), Hashimoto and Murata 7 ) .

Statistical analysis

First, we determined energy and nutrient intakes on the first school survey day and the non-school day separately and then compared them using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. We used values on the first school day for this comparison because intake on the non-school day was measured for a single day only; if we had instead averaged intakes for the two school days, the distribution of intakes would have been narrower than those of the single non-school day due to the reduction in day-to-day variation by the averaging (i.e. outliers of intake were smoothed by averaging and the percentage of inadequacy became lower), which would have in turn hampered comparison of the inadequacy of nutrient intakes, as described below.

To compare the dietary intakes reported in the DR with the corresponding Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) values ( 8 ) , we adjusted the reported nutrient intakes to the energy-adjusted intakes on the assumption that each participant consumed his/her estimated energy requirement (EER) rather than his/her reported energy. Self-administered dietary assessment, including DR, cannot avoid reporting errors, particularly under- or over-reporting ( Reference Willett, Howe and Kushi 9 , Reference Murakami, Sasaki and Takahashi 10 ) . This may induce bias when the reported nutrient intake levels are compared with corresponding DRI values, because the latter do not consider this problem: the DRI values are set for an individual of the reference height and weight shown in the DRI ( 8 ) . The calculation method is as follows: Energy-adjusted nutrient intake (amount/d)=[reported nutrient intake (amount/d)×EER (kcal/d)]/[observed energy intake (kcal/d)]. The EER for each child was calculated based on sex and age in days. Physical activity level was fixed to level II (moderate) ( 8 ) in all participating children due to the absence of quantitative information about physical activity. For protein, fat and carbohydrate, %energy, i.e. the percentage of energy intake from protein, fat or carbohydrate to total energy intake, was used for comparison with DRI values. Inadequacy of nutrient intake was calculated by comparing the adjusted nutrient intake with each dietary reference value according to the Japanese DRI ( 8 ) . Of the total thirty-four nutrients presented in the DRI, five nutrients (biotin, Cr, Mo, Se, iodine) were excluded from analysis because of insufficient information about their contents in the food composition tables in Japan ( 6 ) . For nutrients with an Estimated Average Requirement (EAR), namely protein (g/d), vitamin A expressed as retinol activity equivalents, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B 6 , vitamin B 12 , folate, vitamin C, Ca, Mg, Fe (except for girls aged 13–14 years), Zn and Cu, energy-adjusted intake levels below the EAR were considered inadequate ( 8 ) . For Fe intake in girls aged 13–14 years, because the EAR cut-point method cannot be used due to the seriously skewed distribution of the requirement in menstruating girls, the probability approach was used instead ( 11 – 13 ) . Fe absorption rate was assumed to be 15 % ( 8 ) . In the Japanese DRI, a tentative dietary goal for preventing lifestyle-related diseases (DG) was given for protein (%energy), total fat, carbohydrate, dietary fibre, Na expressed as salt equivalent and K in children ( 8 ) . For these nutrients, energy-adjusted intake levels outside the range of the corresponding DG were considered inadequate. For nutrients with an Adequate Intake, the inadequacy of intake was not assessed.

Second, we estimated the distribution of habitual intake of energy and nutrients in this population by the best-power method using HabitDist, a software application developed to perform this method ( Reference Dodd, Guenther and Freedman 14 – Reference Yokoyama 16 ) . All three of the DR were used for this estimation. The inadequacy of nutrient intake was then calculated in the same manner as described above based on the estimated distribution of intakes.

Finally, the total adequacy of nutrient intake was categorized into four groups, which were used to describe food intake. Averages of the three-day intakes were used as the habitual nutrient intake of each child. The groups for nutrient intake adequacy were determined by combining the number of nutrients which met the EAR (maximum, 14) and the number which met the DG (maximum, 6), and named ‘Adequate’ (number of nutrients meeting the EAR is ≥12, number meeting the DG is ≥4), ‘Excess’ (≥12, ≤3; possibly a high-risk group for non-communicable diseases such as hypertension or CVD), ‘Deficient’ (≤11, ≥4; possibly a high-risk group for insufficiency/deficiency of vitamins and minerals) and ‘Inadequate’ (≤11, ≤3; possibly a high-risk group for both non-communicable diseases and insufficiency/deficiency). Definition of food groups is described elsewhere ( Reference Asakura, Uechi and Masayasu 17 ) . The vegetables group used in the present study included all types of vegetables. The ready-made foods group included retort-pouched beef curry, powdered corn cream soup, white fish for frying (frozen), Hamburg steak (frozen), hamburgers and fried chicken served at fast-food restaurants, etc. Food intake was represented by intake weight (grams) per energy intake of 4184 kJ (1000 kcal), and compared between the groups by the Kruskal–Wallis test and subsequent post hoc analysis (Dwass, Steel and Critchlow-Fligner method).

All analyses were performed with statistical software package SAS version 9.4. Statistical tests were two-sided and P values of <0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Among the 915 children who completed the three-day DR, 910 were included in the analysis. None brought a lunch from home. Two children were eliminated because their average daily energy intake in the survey period was less than 0·5 times the EER for a child of their corresponding age with the lowest physical activity level (EER I ( 8 ) ). Similarly, three children were eliminated because their daily energy intake on any day in the three survey days was less than 3138 kJ (750 kcal; 0·5 times the EER I for girls aged 8–9 years).

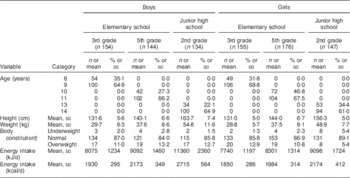

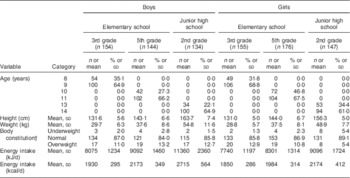

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1 . Each grade and sex stratum included approximately 150 children. About 10 % of children were overweight, but the percentage was low (5·4 %) in the girls in junior high schools.

Table 1 Characteristics of schoolchildren ( n 910) from fourteen elementary and thirteen junior high schools in twelve prefectures of Japan, 2014

Data are presented as n and % unless indicated otherwise.

† Body constitution was evaluated by percentage of excess weight, defined using the formula: [(actual weight – standard weight)/standard weight]×100 (%). If percentage of excess weight was ≥20 %, the child was categorized as overweight; if ≤−20 %, he/she was categorized as underweight.

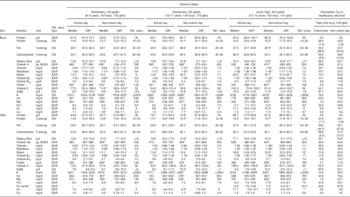

The difference in nutrient intake and prevalence of inadequacy between the first school day and non-school day are described in Table 2 . In all grade and sex strata, intake between the school and non-school days was significantly different for ≥60 % of nutrients. Since the intake data collected on one day were used for comparison, the estimated prevalence of inadequacy in Table 2 was relatively high for all nutrients. However, the difference between school and non-school days was still obvious, and all inadequacies were more prevalent on the non-school day, except for protein in grams and Cu among girls, for which prevalence was zero on both the school and non-school days.

Table 2 Difference in nutrient intake and inadequacy between school and non-school days by grade and sex among schoolchildren ( n 910) from fourteen elementary and thirteen junior high schools in twelve prefectures of Japan, 2014

Ref. value, reference value; IQR, interquartile range; w/m, with menstruation; %energy, percentage of energy; RAE, retinol activity equivalents; EAR, Estimated Average Requirement; DG, tentative dietary goal for preventing lifestyle-related diseases; EER, estimated energy requirement.

Nutrient intake of each day was energy-adjusted based on the assumption that every participant consumed the same amount of energy as his/her EER. Nutrient intake on school days was the value observed on the first day of the three-day diet record.

* P < 0·05 (the comparison between intakes on school and non-school days was performed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

† Prevalence of inadequacy shows the percentage of participants whose nutrient intake on the survey day did not meet the reference value. If a reference value is shown as a range, the percentage of participants whose intake was above the reference range is shown in parentheses. This estimation was performed by the EAR cut-point method.

‡ Retinol activity equivalent.

§ Sodium chloride equivalent.

|| Prevalence of inadequacy for Fe was estimated by the EAR cut-point method. In addition, the probability method was applied for estimation in girls aged 13–14 years using the EAR of Fe for girls with menstruation.

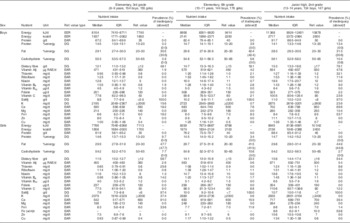

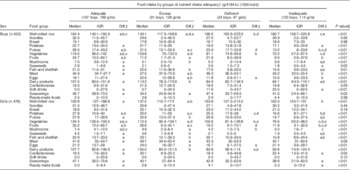

Table 3 shows habitual energy and nutrient intake and the prevalence of inadequacy for the nutrients with an EAR or DG. A high prevalence (more than 30 %) of inadequacy was observed for fat, total dietary fibre and salt in most grade and sex strata. Inadequacy of Ca and Fe intake was high in girls in the third grade of elementary school and in all children in junior high school. The relationship between the total adequacy of nutrient intake and food intake is summarized in Table 4 . Of the seventeen food groups assessed, thirteen food intakes in boys and twelve in girls differed significantly among the four nutrient adequacy groups. In the ‘Adequate’ group, intakes of pulses, vegetables, fruits, mushrooms and seaweeds were higher than in the other groups. The ‘Excess’ group was characterized by high intakes of fish, meat, eggs and dairy products. The ‘Deficient’ group had the fewest children, and their intake of well-milled rice was highest among the four groups. Characteristics of the ‘Inadequate’ group were opposite to those of the ‘Adequate’ group; this group had the lowest intakes of pulses, vegetables and fruits and the highest intake of ready-made foods, and boys in this group had the highest intake of soft drinks.

Table 3 Habitual energy intake and habitual nutrient intake with energy adjustment by grade and sex among schoolchildren ( n 910) from fourteen elementary and thirteen junior high schools in twelve prefectures of Japan, 2014

Ref. value, reference value; IQR, interquartile range; w/m, with menstruation; %energy, percentage of energy; RAE, retinol activity equivalents; EER, estimated energy requirement; EAR, Estimated Average Requirement; DG, tentative dietary goal for preventing lifestyle-related diseases.

Habitual intake was calculated by the best-power method using a three-day diet record. Nutrient intake of each day was energy-adjusted based on the assumption that every participant consumed the same amount of energy as his/her EER.

† Prevalence of inadequacy shows the percentage of participants whose habitual intake did not meet the reference value. If a reference value is shown as a range, the percentage of participants whose habitual intake was above the range is shown in parentheses. This estimation was performed by the EAR cut-point method.

|| Prevalence of inadequacy for Fe was estimated by the EAR cut-point method. In addition, the probability method was applied for the estimation in girls aged 13–14 years using the EAR of Fe for girls with menstruation.

Table 4 Relationship between adequacy of nutrient intake and food intake among schoolchildren ( n 910) from fourteen elementary and thirteen junior high schools in twelve prefectures of Japan, 2014

IQR, interquartile range; diff, significance of between-group difference; DRI, Dietary Reference Intake.

† Groups of nutrient intake adequacy were defined by the number of nutrients that met the reference value in the Japanese DRI ( 8 ) .

Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) is set for fourteen nutrients, and tentative dietary goal for preventing lifestyle-related diseases (DG) is set for six nutrients in the DRI values.

Adequate: number of nutrients which met EAR in the DRI is ≥12, and those which met DG is ≥4.

Excessive: number of nutrients which met EAR in the DRI is ≥12, and those which met DG is ≤3.

Deficient: number of nutrients which met EAR in the DRI is ≤11, and those which met DG is ≥4.

Inadequate: number of nutrients which met EAR in the DRI is ≤11, and those which met DG is ≤3.

‡ The corresponding letters show that there were statistically significant differences in food intake between two groups of nutrient intake adequacy. This comparison for each group was performed as a post hoc analysis (Dwass, Steel and Critchlow-Fligner method) of the Kruskal–Wallis tests.

§ The P value shows the result of Kruskal–Wallis tests to compare food intakes between groups of nutrient intake adequacy.

In this comparison of nutrient intake on school and non-school days in Japanese schoolchildren, we found that the prevalence of inadequate nutrient intake was clearly higher on the non-school day for almost all nutrients. These findings suggest that the school lunch programme in Japan is an effective and powerful intervention in improving nutrient intake in Japanese children. The present study is the first to compare nutrient intakes between school and non-school days in Japan.

The contribution of school lunch programmes has been assessed in other countries. For example, the school lunch standard has gradually been improved in the UK ( Reference Adamson, Spence and Reed 4 ) . Stevens et al . showed that while school lunches generally had a healthier nutrient profile than packed lunches ( Reference Stevens, Nicholas and Wood 18 ) , they nevertheless did not provide the balance of nutrients required to meet nutrient-based standards. Since they collected data for lunch only, it was not possible to compare diet quality between school and non-school days within individuals. Evans et al . reported that children taking a packed lunch to school consumed a lower-quality diet over the whole day than children having a school meal ( Reference Evans, Mandl and Christian 19 ) . Spence et al . also reported that the implementation of school food policy standards in the UK was associated with a significant improvement in the diet of children aged 4–7 years ( Reference Spence, Delve and Stamp 20 ) , but not in children aged 11–12 years ( Reference Spence, Delve and Stamp 21 ) . These authors suggested that school lunches might also be useful in preventing inequity in children’s dietary intake due to the socio-economic status of their family ( Reference Spence, Matthews and White 22 ) . This effect is also expected in the USA ( Reference Huang and Barnidge 23 , Reference Longacre, Drake and Titus 24 ) .

In the USA, the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) was authorized as a permanent programme in 1946 ( Reference Hirschman and Chriqui 25 ) . School food policy in the USA has improved over the past several decades ( Reference Hirschman and Chriqui 25 ) and its effectiveness has been examined. Based on data collected in 2010, Smith and Cunningham-Sabo showed that relatively few students met the NSLP lunch standards, due to the relatively low intake of vegetables at lunch ( Reference Smith and Cunningham-Sabo 26 ) . The Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, the most recent nutrition standards for the NSLP and the School Breakfast Program, took effect at the beginning of the 2012/13 school year. Johnson et al . reported that the nutritional quality of foods chosen by students improved significantly following enforcement of the Act ( Reference Johnson, Podrabsky and Rocha 27 ) , but did not weigh the foods consumed by each child and did not evaluate the quality of total dietary intake, including breakfast and dinner. Cullen et al . showed that intake of fruit, 100 % fruit juice, vegetables and whole grains among elementary-school pupils increased after the new act, but at the same time expressed concern over the low absolute consumption of fruit and vegetables even under the new act ( Reference Cullen, Chen and Dave 28 ) . Given the recent change in school lunch standards and relatively low proportion of children taking school lunches in the UK and USA ( Reference Adamson, Spence and Reed 4 , Reference Hirschman and Chriqui 25 ) , the effect of current school lunches in these countries requires further evaluation. If the proportion of children who take school lunches is low, a beneficial effect of school lunches on total nutrient intake cannot impact schoolchildren even if the standards for school lunches are appropriately established. Increasing the uptake rate of school lunches requires improvements in school meal quality and financial support (if necessary).

A few studies have examined the effectiveness of school lunch programmes in other countries. For example, Dubuisson et al . reported both beneficial and deleterious effects of the school lunch in France ( Reference Dubuisson, Lioret and Dufour 29 ) . Free school lunches are provided to every child in the compulsory school system in Sweden and improvement of the school meal quality was reported after the introduction of new legislation ( Reference Patterson and Elinder 30 ) . Other groups reported that the association between family environment and dietary intake was stronger in countries without free school lunches (Germany and the Netherlands) than in those with them (Sweden and Finland) ( Reference Ray, Roos and Brug 31 ) . These results suggest that school lunches may affect overall diet quality in children.

A unique characteristic of the Japanese school lunch is its fixed menu. Children do not have any choice; the same menu is provided to all students in a school and is usually eaten in the home classroom. The Gakkou Kyushoku-hou (Law for School Lunches) stipulates that school lunches are an integral component of the education programme, and not simply an interval between classes or relaxation or break time. While allowing for cultural differences between countries, improving children’s diet quality using school lunches may require a certain degree of restriction. In England, Day et al . summarized staff and pupil perceptions of school meal provision ( Reference Day, Sahota and Christian 32 ) and found that while some children stated that healthier options in the school lunch were preferable, too much freedom over the selection of foods was potentially detrimental. If school lunch menus do offer choices, these should aim to eliminate less healthful choices and be offered with appropriate instructions about how to select healthy foods. Another distinctive feature of the Japanese school lunch is the low percentage of waste food (e.g. 6·9 % in 2014). This ensures the sufficiency of nutrient intake from school lunches. School dietitians provide a monthly menu for a school and children enjoy various dishes over the one-month period. Also, since all children in a classroom take the same menu, the children may feel pressure to eat everything on their plate like their friends.

Regarding habitual nutrient intake, the inadequacy of most vitamins and minerals was quite low, except for Na. The contribution of school lunches to improving the intake of these items was considered to be sufficient. However, higher fat and salt intakes and lower dietary fibre intake than those provided in the DRI were apparent in both boys and girls in all age groups. Although nutrient levels in school lunches are already regulated by the Standards for the School Lunch Program, achieving the recommended values requires more diligent compliance. Indeed, compliance policies may require revision. Intakes of Ca and Fe were not sufficient in girls in the youngest (8–9 years) group or in children in junior high school. Intakes of these minerals in junior high-school students might not have increased to meet the increased requirements of the growth spurt at this age. On the other hand, it is possible that the reference values are not appropriate for children in certain age groups. For example, the EAR for Ca in girls aged 8–9 years is higher than that for boys of the same age. Because intake data for children are generally lacking, reference values in children are usually established by extrapolating the values for adults. The suitability of reference values for each sex and each age group warrants reassessment using more appropriate dietary assessment data. Further studies to describe dietary intake in children are necessary to improve the DRI in Japan.

Food intake differed significantly by the total adequacy of nutrient intake. Children in the ‘Adequate’ group consumed more plant foods than others, except for cereals. Abundant intake of these foods led to adequate intakes of vitamins and minerals. The ‘Excess’ group was characterized by higher intake of animal foods and lower intake of well-milled rice. This group contained three times more children than the ‘Deficient’ group, implying that inadequate intake of nutrients such as fat or salt, which are associated with CVD ( Reference Kaikkonen, Mikkila and Raitakari 2 ) , is more problematic than nutrient deficiency in Japanese schoolchildren. Characteristics of the ‘Deficient’ group were less clear. The word ‘deficient’ here means that a number of intakes of nutrients with an EAR (i.e. nutrients which can cause deficiency) were inappropriate, whereas intakes of nutrients with a DG (i.e. nutrients which can cause non-communicable diseases such as CVD) were relatively appropriate. The ‘Deficient’ group had higher intakes of well-milled rice and seasonings and lower intakes of eggs and dairy products. Children in this group might have had higher consumption of staple foods (mostly well-milled rice) and lower consumption of main and side dishes than others. The balance between the amount of staple foods and main dishes may be important to maintaining appropriate macronutrient balance. Children in the ‘Inadequate’ group consumed less plant foods except for cereals and relatively less animal foods, but more ready-made foods, soft drinks and confectioneries. Their intake of well-milled rice was second highest among the four groups. These results conclusively demonstrate that increased intakes of fruits and vegetables will improve the nutrient intakes of schoolchildren, and that school lunches should be diligently planned to include them. In contrast, main dishes, which chiefly include meats, fish or eggs, should be selected with care even in school lunches. In addition, the intakes of these animal foods among children in the ‘Inadequate’ group were low, but only a small number of nutrients met the DG. Cooking methods that do not use much oil/fat and a reduced use of seasonings are recommended. The intakes of fat and salt should also be decreased by avoiding the intake of confectioneries. Regarding dietary fibre intake, higher intakes of not only vegetables and fruits but also unrefined cereals can be recommended. The mean daily intake of brown or half-milled rice in this study population was less than 10 g (data not shown). Some schools participating in the study provided rice cooked with barley for lunch; this is also an effective means of increasing dietary fibre intake in children.

The present study was a school-based, nationwide study and the participation rate was relatively high (76·9 %). We therefore consider that the generalizability of the results is sufficient. Additional strengths of the study were its quantitative assessment of dietary intake on both school and non-school days, and use of a three-day DR, which allowed us to estimate the habitual intake of each nutrient in the analysed population. Further, all children in the present study routinely had school lunches irrespective of their nutrient intake or socio-economic status. Since reverse causality (e.g. children in low socio-economic status tend to have school lunches) was very unlikely, it was possible to directly observe the contribution of school lunches to overall nutrient intake in the children.

At the same time, several limitations of the study warrant mention. First, since most analyses were performed with stratification by sex and age, the number of children in each stratum was approximately 150. Although this might appear small for the estimation of average intakes and exact distributions, results across strata regarding the adequacy of nutrient intake were similar and could be interpreted. Second, as schools with experienced nutrition teachers (dietitians) were selected for the survey, the beneficial aspect of school lunches may have been emphasized due to better menus and less leftovers. However, as described before, the nutrient content of school lunches is regulated by the national standards and the percentage of waste food is 6·9 % on average, even in the national survey. Third, a three-day DR might be too short to allow habitual intake to be estimated with precision. In addition, to ensure that our comparison of the prevalence of nutrient intake inadequacy between school and non-school days was valid, prevalence had to be calculated using only one of the two school-day DR, to prevent the confounding that would have been introduced by averaging over the two days, as noted above. However, the difference in prevalence between the school and non-school days was obvious, and the results were clear. Since dietary assessment by DR places a heavy burden on participants, a period longer than 3d was not considered feasible. Finally, the DR at home was performed by the guardians of the participating children. Since this was the first experience with a DR for most, the accuracy of the record might be less than would be obtained by a trained dietitian. To ensure the quality of the DR, the guardians were provided with a detailed survey manual and were supported by their school dietitian.

In conclusion, the present study found that school lunches in Japan appear to improve nutrient intakes in Japanese schoolchildren. The improvement in intake for most vitamins and minerals provided by the school lunch may be sufficient for schoolchildren to overcome deficiencies in the diet received at home, when this is inadequate. On the other hand, the excess intakes of fat and salt and insufficient intake of dietary fibre were major problems in this population. The contribution of the school lunch to improving the intakes of these three nutrients was considered insufficient.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the dietitians, school nurses and teachers who supported this research in each school, and the staff of the municipal government in each study area for their valuable contribution. Financial support: This work was financially supported by a Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant (number H26-Jyunkankitou (seisaku)-shitei-001) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: Author contributions are follows: S.S designed and directed the study. K.A. supported field establishment and recruitment for the study. S.S. and K.A. supported the collection of dietary data. K.A. arranged the data collected from each school. K.A. performed the statistical analyses and drafted the paper. Both authors contributed to the development of the submitted manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo, Faculty of Medicine (approval number 10653, approval date 3 October 2014). Participants (children) and their guardians were informed about the study verbally and by a written document before answering the questionnaire, and responding to the questionnaire was regarded as consent for study participation. Since no personally identifiable information such as name or mailing address was collected, all collected data were anonymous.

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000374

Asakura supplementary material

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 20, Issue 9

- Keiko Asakura (a1) (a2) and Satoshi Sasaki (a2)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000374

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Status | |

| Version | |

| Ad File | |

| Disable Ads Flag | |

| Environment | |

| Moat Init | |

| Moat Ready | |

| Contextual Ready | |

| Contextual URL | |

| Contextual Initial Segments | |

| Contextual Used Segments | |

| AdUnit | |

| SubAdUnit | |

| Custom Targeting | |

| Ad Events | |

| Invalid Ad Sizes |

- Submit Member Login

Access provided by

Student Perception of Healthfulness, School Lunch Healthfulness, and Participation in School Lunch: The Healthy Communities Study

Download started

- Add to Mendeley

Conclusions and Implications

- nutrition policy

- school lunch participation

- school meals

Get full text access

Log in, subscribe or purchase for full access.

Article metrics

Related articles.

- Download Hi-res image

- Download .PPT

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Articles In Press

- Current Issue

- List of Issues

- Supplements

- For Authors

- Author Guidelines

- Submit Your Manuscript

- Statistical Methods

- Guidelines for Authors of Educational Material Reviews

- Permission to Reuse

- About Open Access

- Researcher Academy

- For Reviewers

- General Guidelines

- Methods Paper Guidelines

- Qualitative Guidelines

- Quantitative Guidelines

- Questionnaire Methods Guidelines

- Statistical Methods Guidelines

- Systematic Review Guidelines

- Perspective Guidelines

- GEM Reviewing Guidelines

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Disclosures

- Abstracting/Indexing

- Impact/Metrics

- Contact Information

- Editorial Staff and Board

- Info for Advertisers

- Member Access Instructions

- New Content Alerts

- Sponsored Supplements

- Statistical Reviewers

- Reviewer Appreciation

- New Resources

- New Resources for Nutrition Educators

- Submit New Resources for Review

- Guidelines for Writing Reviews of New Resources for Nutrition Educators

- Podcast/Webinars

- New Resources Podcasts

- Press Release & Other Podcasts

- Collections

- Society News

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

Society Member Access

SNEB Members, full access to the journal is a member benefit. Login via the SNEB Website to access all journal content and features.

- Institutional Access: Log in to ScienceDirect

- Existing Subscriber: Log in

- New Subscriber: Claim access with activation code. New subscribers select Claim to enter your activation code.

Academic & Personal

Corporate r&d professionals.

- Full online access to your subscription and archive of back issues

- Table of Contents alerts

- Access to all multimedia content, e.g. podcasts, videos, slides

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Student Perception of Healthfulness, School Lunch Healthfulness, and Participation in School Lunch: The Healthy Communities Study

Affiliations.

- 1 Nutrition Policy Institute, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California, Berkeley, CA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Nutrition Policy Institute, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California, Berkeley, CA.

- 3 School of Nutrition and Health Promotion, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ.

- PMID: 30850302

- PMCID: PMC6662582

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jneb.2019.01.014

Objective: To increase understanding about the healthfulness of school lunch and participation, this study measured 3 school lunch variables, students' perception of healthfulness, objective healthfulness, and participation, and examined associations between each pair of variables (3 associations).

Methods: Multilevel models were used for a secondary analysis of data from the Healthy Communities Study, a 2013-2015 observational study of schools (n = 423) and children (n = 5,106) from 130 US communities.

Results: Students who reported that school lunches were sometimes, often, or very often healthy ate school lunches more frequently per week (β = .71; P < .001) than did students who responded never or rarely. No associations were found with objective school lunch healthfulness.

Conclusions and implications: Student perception of healthfulness of school lunch is positively associated with participation but not with objective school lunch healthfulness. Understanding how student perception is associated with participation can inform effective communications to students to increase participation in the school lunch program.

Keywords: nutrition policy; perception; school lunch participation; school meals; students.

Copyright © 2019 Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Perceived reactions of elementary school students to changes in school lunches after implementation of the United States Department of Agriculture's new meals standards: minimal backlash, but rural and socioeconomic disparities exist. Turner L, Chaloupka FJ. Turner L, et al. Child Obes. 2014 Aug;10(4):349-56. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0038. Epub 2014 Jul 21. Child Obes. 2014. PMID: 25045934 Free PMC article.

- Disparities in the Healthfulness of School Food Environments and the Nutritional Quality of School Lunches. Bardin S, Washburn L, Gearan E. Bardin S, et al. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 8;12(8):2375. doi: 10.3390/nu12082375. Nutrients. 2020. PMID: 32784416 Free PMC article.

- Community eligibility and other provisions for universal free meals at school: impact on student breakfast and lunch participation in California public schools. Turner L, Guthrie JF, Ralston K. Turner L, et al. Transl Behav Med. 2019 Oct 1;9(5):931-941. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz090. Transl Behav Med. 2019. PMID: 31328770

- Do Parental Perceptions of the Nutritional Quality of School Meals Reflect the Food Environment in Public Schools? Martinelli S, Acciai F, Yedidia MJ, Ohri-Vachaspati P. Martinelli S, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Oct 14;18(20):10764. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010764. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. PMID: 34682510 Free PMC article.

- Effect of school wellness policies and the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act on food-consumption behaviors of students, 2006-2016: a systematic review. Mansfield JL, Savaiano DA. Mansfield JL, et al. Nutr Rev. 2017 Jul 1;75(7):533-552. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux020. Nutr Rev. 2017. PMID: 28838082 Review.

- Purchasing Behavior, Setting, Pricing, Family: Determinants of School Lunch Participation. Sobek C, Ober P, Abel S, Spielau U, Kiess W, Meigen C, Poulain T, Igel U, Vogel M, Lipek T. Sobek C, et al. Nutrients. 2021 Nov 24;13(12):4209. doi: 10.3390/nu13124209. Nutrients. 2021. PMID: 34959761 Free PMC article.

- Students' perceptions of school sugar-free, food and exercise environments enhance healthy eating and physical activity. Liu CH, Chang FC, Niu YZ, Liao LL, Chang YJ, Liao Y, Shih SF. Liu CH, et al. Public Health Nutr. 2021 Dec 22;25(7):1-9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021004961. Online ahead of print. Public Health Nutr. 2021. PMID: 34933694 Free PMC article.

- The Challenging Task of Measuring Home Cooking Behavior. Raber M, Wolfson J. Raber M, et al. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2021 Mar;53(3):267-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2020.11.012. Epub 2021 Jan 14. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2021. PMID: 33454197 Free PMC article.

- Parental Perceptions of the Nutritional Quality of School Meals and Student Meal Participation: Before and After the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act. Martinelli S, Acciai F, Au LE, Yedidia MJ, Ohri-Vachaspati P. Martinelli S, et al. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020 Nov;52(11):1018-1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2020.05.003. Epub 2020 Jul 9. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020. PMID: 32654886 Free PMC article.

- USDA Food and Nutrition Service. National School Lunch Program: Participation and Lunches Served 2018; https://fnsprod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/pd/slsummar.pdf Accessed November 15, 2018.

- Au LE, Gurzo K, Gosliner W, Webb KL, Crawford PB, Ritchie LD. Eating School Meals Daily Is Associated with Healthier Dietary Intakes: The Healthy Communities Study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2018;118(8):1474–1481.e1471. - PMC - PubMed

- Robinson-O’Brien R, Burgess-Champoux T, Haines J, Hannan PJ, Neumark-Sztainer D. Associations between school meals offered through the National School Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program and fruit and vegetable intake among ethnically diverse, low-income children. The Journal of school health 2010;80(10):487–492. - PMC - PubMed

- Institute of Medicine. Committee on Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools: Leading the Way Toward Healthier Youth; Washington, DC: 2007.

- Moore Q, Hulsey L, Ponza M. Factors Associated with School Meal Participation and the Relationship Between Different Participation Measures. IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEc 2009.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Grants and funding

- K01 HL131630/HL/NHLBI NIH HHS/United States

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- ClinicalKey

- Elsevier Science

- Europe PubMed Central

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- PubMed Central

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

How school lunch quality affects student achievement

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 was intended to improve student health and reduce childhood obesity by increasing the minimum nutritional standards that schools must meet. Despite its good intentions, the changes mandated by this act were met with immediate backlash . In response to the criticism and as part of its commitment to repeal a host of Obama-era regulations, the Trump administration recently put a stop to some of the new standards .

But could returning to the days of anything-goes in school cafeterias negatively impact student achievement? The results from a recent NBER study suggest it’s possible. In the past, analyses of school meals have been limited to examinations of whether providing meals can increase test scores (it does). This study is unique because it investigates whether the nutritional quality of meals can boost test scores.

The researchers examined a dataset of California public elementary, middle, and high schools that report state test results. From there, they determined whether these schools had a contract with a private meal provider. In total, approximately 143 districts overseeing 1,188 schools—12 percent of California’s public schools—did so, contracting with a total of forty-five different vendors. The remaining 88 percent of California’s public schools utilized “in-house” staff to prepare meals.

Next, trained nutritionists from the Nutrition Policy Institute determined the quality of vendors’ school lunches by using a modified version of the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), a measure of diet quality that’s used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to determine relationships between diet and health-related outcomes. Vendors with an HEI score above the median vendor score were labeled healthy vendors, while those with below median HEI scores were labeled standard vendors.

For student achievement data, researchers used California’s Standardized Testing and Reporting (STAR) assessment, which was the statewide test until 2013-14. STAR was administered to all students in grades two through eleven each spring, and covered the four core subject areas as well as a set of end-of-course high school exams. Researchers used these data to create a single composite test score for each year and each school grade.

After controlling for various factors, results show that contracting with a healthy vendor increased student test scores by .03 to .04 standard deviations on average relative to in-school meal preparation. In laymen’s terms, that's a boost of about 4 percentile points . The findings also show modest evidence of larger effects for economically disadvantaged students than for non-disadvantaged students. Healthy cafeteria vendors did not cost dramatically more than in-house preparation. Researchers also found that switching from in-house meal prep to a healthy lunch vendor would raise a student’s test score by 0.1 standard deviations for only $258 per year. By comparison, the Tennessee STAR experiment —which reduced class size in grades K-3—cost $1,368 per year to raise a student’s test score by the same amount.

Aside from increased student achievement and low cost, the report offers a few additional data points. First, it found no evidence that hiring a vendor to serve healthier meals led to a change in the number of lunches sold. Second, healthy meal vendors did not reduce the percentage of students who are overweight, although the researchers note that “a longer time period may be necessary to observe improvements in health.” For schools looking to increase student achievement without spending a fortune, investing in healthy meals seems like a cost-effective solution.

SOURCE: Michael L. Anderson, Justin Gallagher, Elizabeth Ramirez Ritchie, “School Lunch Quality and Academic Performance ,” National Bureau of Economic Research (April 2017).

Jessica Poiner joined the Thomas B. Fordham Institute in 2014 as an education policy analyst. Prior to joining the Fordham team, she was a Teach For America corps member who worked as a high school English teacher in Memphis, Tennessee. She writes regularly for Fordham’s blog, the Ohio Gadfly Daily ,…

- (888) 506-6011

- Current Students

- Main Campus

- Associate Degrees

- Bachelor’s Degrees

- Master’s Degrees

- Post-Master’s Degrees

- Certificates & Endorsements

- View All Degrees

- Communications

- Computer Science

- Criminal Justice

- Humanities, Arts, and Sciences

- Ministry & Theology

- Social Work

- Teaching & Education

- Admission Process

- Academic Calendar

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Military Education Benefits

- Transfer Students

- Tuition & Costs

- Financial Aid

- Financial Aid FAQ

- Online Student Testimonials

- Student Services

- Resource Type

- Program Resources

- Career Outcomes

- Infographics

- Articles & Guides

- Get Started

Healthy Body, Healthy Mind: The Impact of School Lunch on Student Performance

By now, it is no mystery that what people eat has an effect on their daily physical and mental health. When people keep themselves well-nourished, they can participate more fully and effectively in a wide variety of activities. Of course, nutrition has an impact on K-12 students as well, from their academic performance to their behavior in the classroom.

During the 2012–2013 school year, more than 30 million students participated in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) , according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report. By providing healthy lunches, schools can help their students perform better in the classroom and improve their overall health.

The State of School Lunches

The School Nutrition Association (SNA) is the largest professional organization for school lunch providers in the country, with 55,000 members. The SNA offers a fact sheet of statistics about the current state of the National School Lunch Program.

Through the program, nearly 100,000 schools and institutions serve lunches each day. Of the total 30 million students served:

- 2 million are receiving free lunches (children from families with incomes at or below 130 percent of the poverty level are eligible)

- 5 million are receiving reduced-price lunches (children from families with incomes between 130 percent and 185 percent of the poverty level are eligible)

- 7 million pay full price (school districts set their own prices for paid meals)

Currently, 130 percent of the poverty level is $31,005 for a family of four, and 185 percent is $44,123.

This data points toward one of the major issues with school lunches in America. If 19.2 million students are receiving free lunches due to their socioeconomic status, school lunch could be their only opportunity for a nutritious meal each day.

Free Healthy Meals Activity

Download our free Healthy Meals activity for your elementary students!

School Lunch Legislation

In 1945, President Harry S. Truman signed into law the National School Lunch Act, which created the National School Lunch Program. In post-World War II America, Truman and Congress intended the bill to help absorb new farm surpluses.

When President Barack Obama was elected, first lady Michelle Obama sought to revitalize the National School Lunch Program as a part of her mission against childhood obesity. Nearly one in three American children are either overweight or obese , putting them at risk for chronic health problems related to obesity, such as heart disease, high blood pressure, cancer and asthma.

School lunches had reached a point where they were not providing the nutrients students needed to succeed and be healthy. With so many students relying on free school lunches as their primary meal for the day, reform became imperative.

In 2010, Congress passed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act . This bill made significant changes to school lunches for the first time in decades.

The most important change was the introduction of higher nutrition standards developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The bill also places emphasis on the utilization of local farms and gardens to provide students with fresh produce. It requires schools to be audited every three years to see if they have met the nutrition standards.

As the USDA worked on turning the guidelines into regulations, pushback came from several groups. Some members of Congress who had supported the legislation began to criticize government intrusion into schools, and food companies that became fearful of falling profits began to lobby for delaying the changes.

Nevertheless, the USDA regulations went into effect during the 2012-2013 school year. With every meal, schools are required to offer students fruits and vegetables, low-fat or fat-free milk, whole grains and lean protein , according to the Student Nutrition Association.

Some school districts have had to overcome challenges with implementing the USDA standards due to the increasing cost of feeding students. In school cafeterias, lunches must be easy to prepare and distribute in an efficient manner.

Impact of Nutrition on Students

For years, scientists have been studying the effect of nutrition on student performance. In 2008, a Journal of School Health study discovered that fifth-graders eating fast food scored worse on standardized literary assessments. A follow-up study of fifth-graders published in The Journal of Educational Research in 2012 linked eating fast food to declining math and reading scores. How exactly do these foods affect children?

Nutrition can affect students either directly or indirectly. A 2014 report, “Nutrition and Students’ Academic Performance,” summarizes research on these issues.

Direct Effects

There are several direct effects that involve the immediate impact of nutrition on the daily performance of a student. Mental and behavioral problems can be traced back to unhealthy nutrition and poor eating habits.

Nutritional deficiencies in zinc, B vitamins, Omega-3 fatty acids and protein have been shown to affect the cognitive development of children. There is also evidence to suggest that diets with high amounts of trans and saturated fats can have a negative impact on cognition. This will harm the ability of students to learn at a pace necessary for school success.

Scientists have also established a link between student behavior and nutrition. Access to proper nutrition can help students maintain psychosocial well-being and reduce aggression. This can have a positive effect on students by avoiding discipline and school suspension.

Indirect Effects

The indirect effects of poor nutrition can be severely detrimental to the performance of students over time. Students with unhealthy lifestyles are far more likely to become sick. These illnesses then have an effect on the amount of class time missed. By not attending classes, students are much more likely to fall behind. And when they are in class, they are more likely to have little energy and to have concentration issues.

The Future of School Lunch and Student Performance

Teachers know that school lunches are a key part of the school system. They have a daily impact on the well-being of students both inside and outside of school. If you’re a teacher interested in developing your leadership skills and expanding your knowledge of how to improve student academic performance, consider the online Master of Arts in Education from Campbellsville University. The fully online program can help you gain the credentials you need while maintaining your responsibilities. Learn more today!

- Bibliography

- More Referencing guides Blog Automated transliteration Relevant bibliographies by topics

- Automated transliteration

- Relevant bibliographies by topics

- Referencing guides

'The Asian Kid With The Stinky Lunch' Narrative Is A Pop Culture Trope, But It's Still Worth Telling

Senior Lifestyle Reporter, HuffPost

If you’re part of the Asian American community and very online, you’re no doubt familiar with the “ethnic stinky lunch” narrative.

If you’re not familiar, the “stinky lunch” trope goes a little something like this: A kid brings something into the cafeteria that’s a different than the standard PB&J or ham sandwich ― beef bulgogi in Tupperware, for instance, or Spam musubi ― and is met with quizzical stares from classmates.

Sometimes the stares are accompanied by mean comments: “That stinks,” someone will mutter under their breath. “ Gross .” Other kids will go straight for the jugular and say something like, “Ugh, looks like you’re eating dog food.”

“I got very self-conscious, and when the teacher wasn’t looking, I would discreetly throw my food out into the trash and proceeded to do this for a week.” - Aydin Quach, a Ph.D. student in American Studies at the University of Southern California

Reflecting on the experience years later, stories about stinky lunches usually end with the writer reclaiming the narrative and saying that now they’re proud of their cultural dishes: Sure, the smell was pungent, but their lunch tasted loads better than Kyle’s turkey and cheese Lunchable. Plus, in these post-Anthony Bourdain “No Reservations”-days, beef bulgogi is trendy and as commonplace as a Big Mac.

Many a personal essay has been written about overcoming the trauma of being the Asian kid with the stinky lunch. Eddie Huang devoted a whole episode of his sitcom “Fresh off the Boat” to the lead character wanting to bring in “white people lunch.”

Food-shaming along these lines is so common for Asian kids growing up in the U.S., that even homeschooled kids can’t escape it.

Jennifer LeMesurier is a Korean American who was adopted by white parents and though she was homeschooled most of her life, she still has a story.

LeMesurier ― an associate professor of writing and rhetoric at Colgate University in Hamilton, New York, and the author of “Inscrutable Eating: Asian Appetites and the Rhetorics of Racial Consumption” ― recalls going on a group trip with other homeschooled kids in first grade to Uwajimaya Asian Market in Seattle.

Though it was very much an “expand your horizons”-type of trip, LeMesurier said the minute the kids got to the tanks of live crabs and shellfish, the whole group erupted in a loud, collective squeal of “eww!”

“I remember I felt both confused as to why everyone else was being so rude, and embarrassed as the one Asian kid in the group,” she told HuffPost.

“Since I looked more like the people working behind the counter than my classmates, all of a sudden I didn’t know where my allegiance was supposed to be,” she said.