Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Focus Group? | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

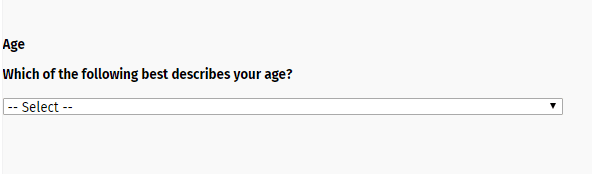

What is a Focus Group | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on December 10, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

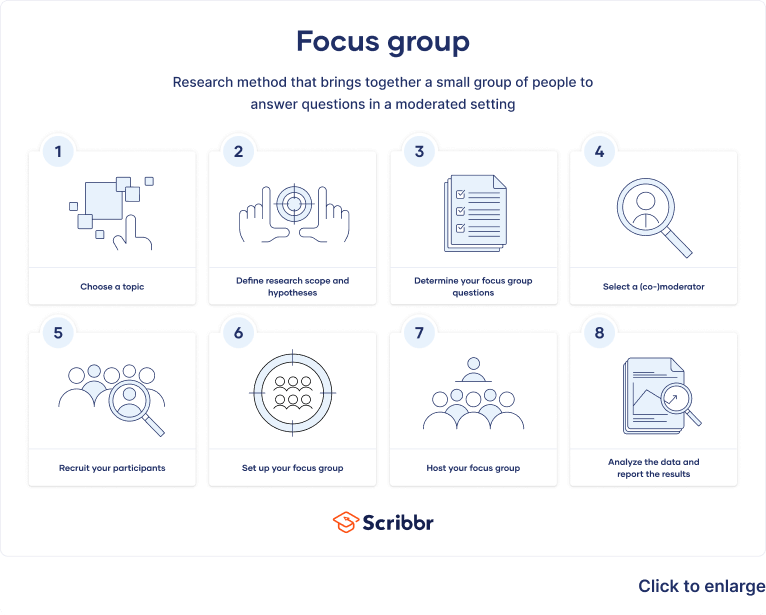

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest.

Table of contents

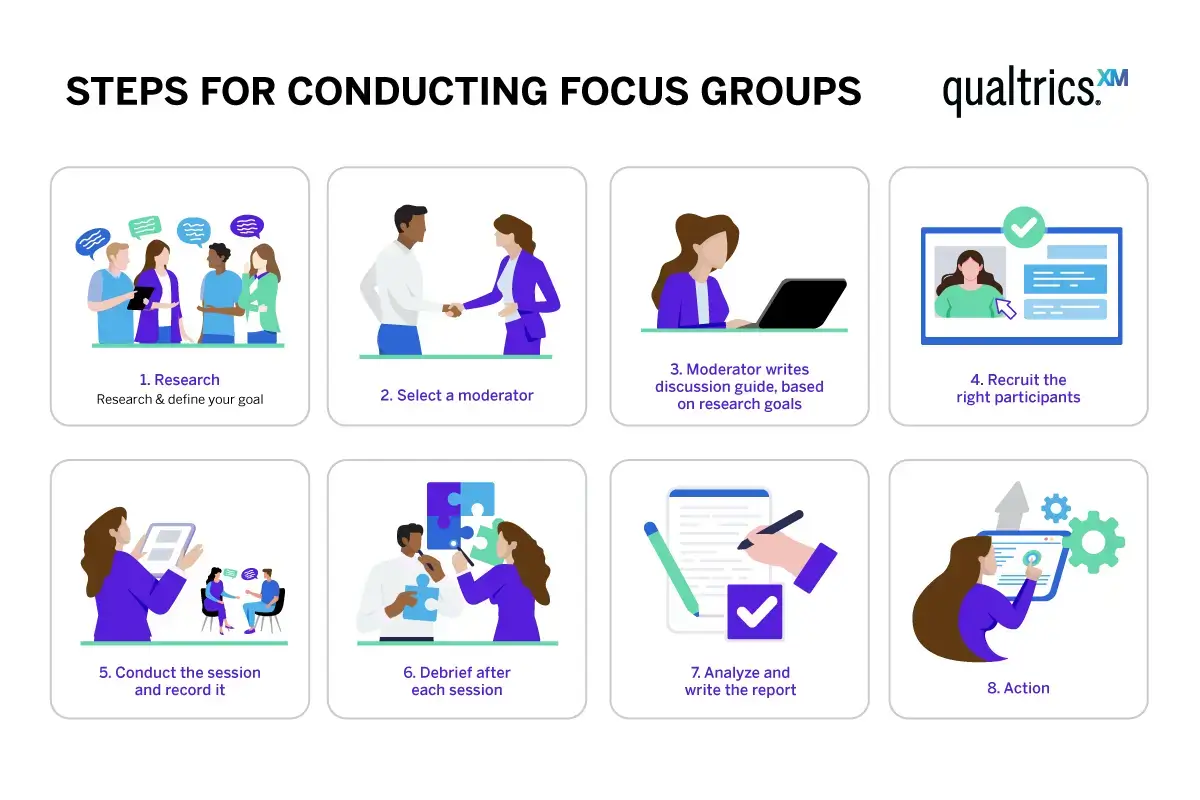

What is a focus group, step 1: choose your topic of interest, step 2: define your research scope and hypotheses, step 3: determine your focus group questions, step 4: select a moderator or co-moderator, step 5: recruit your participants, step 6: set up your focus group, step 7: host your focus group, step 8: analyze your data and report your results, advantages and disadvantages of focus groups, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about focus groups.

Focus groups are a type of qualitative research . Observations of the group’s dynamic, their answers to focus group questions, and even their body language can guide future research on consumer decisions, products and services, or controversial topics.

Focus groups are often used in marketing, library science, social science, and user research disciplines. They can provide more nuanced and natural feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organize than experiments or large-scale surveys .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Focus groups are primarily considered a confirmatory research technique . In other words, their discussion-heavy setting is most useful for confirming or refuting preexisting beliefs. For this reason, they are great for conducting explanatory research , where you explore why something occurs when limited information is available.

A focus group may be a good choice for you if:

- You’re interested in real-time, unfiltered responses on a given topic or in the dynamics of a discussion between participants

- Your questions are rooted in feelings or perceptions , and cannot easily be answered with “yes” or “no”

- You’re confident that a relatively small number of responses will answer your question

- You’re seeking directional information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

Differences between types of interviews

Make sure to choose the type of interview that suits your research best. This table shows the most important differences between the four types.

| Structured interview | Semi-structured interview | Unstructured interview | Focus group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed questions | ||||

| Fixed order of questions | ||||

| Fixed number of questions | ||||

| Option to ask additional questions |

Topics favorable to focus groups

As a rule of thumb, research topics related to thoughts, beliefs, and feelings work well in focus groups. If you are seeking direction, explanation, or in-depth dialogue, a focus group could be a good fit.

However, if your questions are dichotomous or if you need to reach a large audience quickly, a survey may be a better option. If your question hinges upon behavior but you are worried about influencing responses, consider an observational study .

- If you want to determine whether the student body would regularly consume vegan food, a survey would be a great way to gauge student preferences.

However, food is much more than just consumption and nourishment and can have emotional, cultural, and other implications on individuals.

- If you’re interested in something less concrete, such as students’ perceptions of vegan food or the interplay between their choices at the dining hall and their feelings of homesickness or loneliness, perhaps a focus group would be best.

Once you have determined that a focus group is the right choice for your topic, you can start thinking about what you expect the group discussion to yield.

Perhaps literature already exists on your subject or a sufficiently similar topic that you can use as a starting point. If the topic isn’t well studied, use your instincts to determine what you think is most worthy of study.

Setting your scope will help you formulate intriguing hypotheses , set clear questions, and recruit the right participants.

- Are you interested in a particular sector of the population, such as vegans or non-vegans?

- Are you interested in including vegetarians in your analysis?

- Perhaps not all students eat at the dining hall. Will your study exclude those who don’t?

- Are you only interested in students who have strong opinions on the subject?

A benefit of focus groups is that your hypotheses can be open-ended. You can be open to a wide variety of opinions, which can lead to unexpected conclusions.

The questions that you ask your focus group are crucially important to your analysis. Take your time formulating them, paying special attention to phrasing. Be careful to avoid leading questions , which can affect your responses.

Overall, your focus group questions should be:

- Open-ended and flexible

- Impossible to answer with “yes” or “no” (questions that start with “why” or “how” are often best)

- Unambiguous, getting straight to the point while still stimulating discussion

- Unbiased and neutral

If you are discussing a controversial topic, be careful that your questions do not cause social desirability bias . Here, your respondents may lie about their true beliefs to mask any socially unacceptable or unpopular opinions. This and other demand characteristics can hurt your analysis and lead to several types of reseach bias in your results, particularly if your participants react in a different way once knowing they’re being observed. These include self-selection bias , the Hawthorne effect , the Pygmalion effect , and recall bias .

- Engagement questions make your participants feel comfortable and at ease: “What is your favorite food at the dining hall?”

- Exploration questions drill down to the focus of your analysis: “What pros and cons of offering vegan options do you see?”

- Exit questions pick up on anything you may have previously missed in your discussion: “Is there anything you’d like to mention about vegan options in the dining hall that we haven’t discussed?”

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

It is important to have more than one moderator in the room. If you would like to take the lead asking questions, select a co-moderator who can coordinate the technology, take notes, and observe the behavior of the participants.

If your hypotheses have behavioral aspects, consider asking someone else to be lead moderator so that you are free to take a more observational role.

Depending on your topic, there are a few types of moderator roles that you can choose from.

- The most common is the dual-moderator , introduced above.

- Another common option is the dueling-moderator style . Here, you and your co-moderator take opposing sides on an issue to allow participants to see different perspectives and respond accordingly.

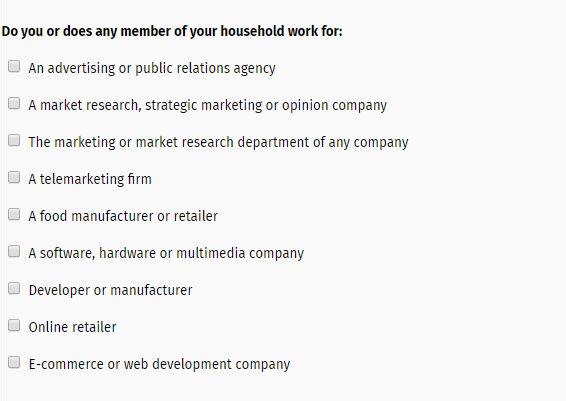

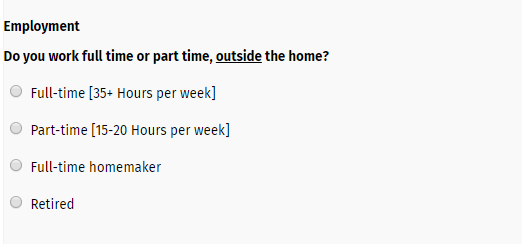

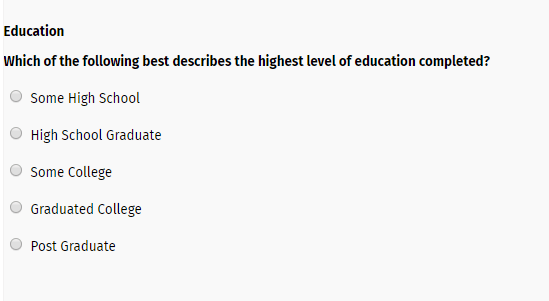

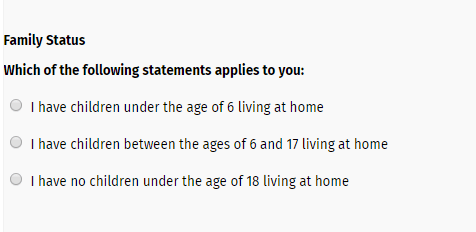

Depending on your research topic, there are a few sampling methods you can choose from to help you recruit and select participants.

- Voluntary response sampling , such as posting a flyer on campus and finding participants based on responses

- Convenience sampling of those who are most readily accessible to you, such as fellow students at your university

- Stratified sampling of a particular age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, or other characteristic of interest to you

- Judgment sampling of a specific set of participants that you already know you want to include

Beware of sampling bias and selection bias , which can occur when some members of the population are more likely to be included than others.

Number of participants

In most cases, one focus group will not be sufficient to answer your research question. It is likely that you will need to schedule three to four groups. A good rule of thumb is to stop when you’ve reached a saturation point (i.e., when you aren’t receiving new responses to your questions).

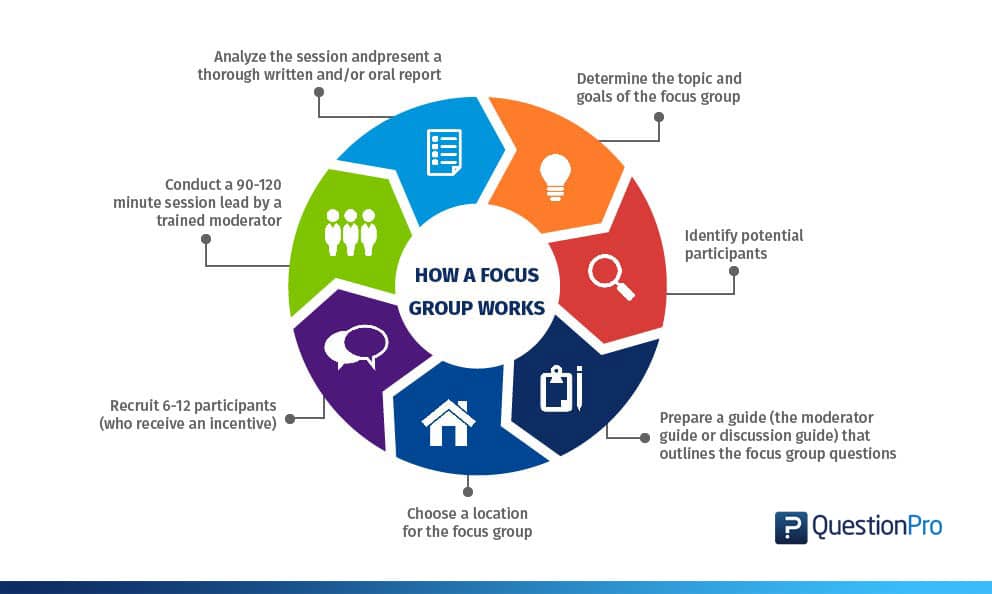

Most focus groups have 6–10 participants. It’s a good idea to over-recruit just in case someone doesn’t show up. As a rule of thumb, you shouldn’t have fewer than 6 or more than 12 participants, in order to get the most reliable results.

Lastly, it’s preferable for your participants not to know you or each other, as this can bias your results.

A focus group is not just a group of people coming together to discuss their opinions. While well-run focus groups have an enjoyable and relaxed atmosphere, they are backed up by rigorous methods to provide robust observations.

Confirm a time and date

Be sure to confirm a time and date with your participants well in advance. Focus groups usually meet for 45–90 minutes, but some can last longer. However, beware of the possibility of wandering attention spans. If you really think your session needs to last longer than 90 minutes, schedule a few breaks.

Confirm whether it will take place in person or online

You will also need to decide whether the group will meet in person or online. If you are hosting it in person, be sure to pick an appropriate location.

- An uncomfortable or awkward location may affect the mood or level of participation of your group members.

- Online sessions are convenient, as participants can join from home, but they can also lessen the connection between participants.

As a general rule, make sure you are in a noise-free environment that minimizes distractions and interruptions to your participants.

Consent and ethical considerations

It’s important to take into account ethical considerations and informed consent when conducting your research. Informed consent means that participants possess all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate in the research before it starts. This includes information about benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

Participants should also sign a release form that states that they are comfortable with being audio- or video-recorded. While verbal consent may be sufficient, it is best to ask participants to sign a form.

A disadvantage of focus groups is that they are too small to provide true anonymity to participants. Make sure that your participants know this prior to participating.

There are a few things you can do to commit to keeping information private. You can secure confidentiality by removing all identifying information from your report or offer to pseudonymize the data later. Data pseudonymization entails replacing any identifying information about participants with pseudonymous or false identifiers.

Preparation prior to participation

If there is something you would like participants to read, study, or prepare beforehand, be sure to let them know well in advance. It’s also a good idea to call them the day before to ensure they will still be participating.

Consider conducting a tech check prior to the arrival of your participants, and note any environmental or external factors that could affect the mood of the group that day. Be sure that you are organized and ready, as a stressful atmosphere can be distracting and counterproductive.

Starting the focus group

Welcome individuals to the focus group by introducing the topic, yourself, and your co-moderator, and go over any ground rules or suggestions for a successful discussion. It’s important to make your participants feel at ease and forthcoming with their responses.

Consider starting out with an icebreaker, which will allow participants to relax and settle into the space a bit. Your icebreaker can be related to your study topic or not; it’s just an exercise to get participants talking.

Leading the discussion

Once you start asking your questions, try to keep response times equal between participants. Take note of the most and least talkative members of the group, as well as any participants with particularly strong or dominant personalities.

You can ask less talkative members questions directly to encourage them to participate or ask participants questions by name to even the playing field. Feel free to ask participants to elaborate on their answers or to give an example.

As a moderator, strive to remain neutral . Refrain from reacting to responses, and be aware of your body language (e.g., nodding, raising eyebrows) and the possibility for observer bias . Active listening skills, such as parroting back answers or asking for clarification, are good methods to encourage participation and signal that you’re listening.

Many focus groups offer a monetary incentive for participants. Depending on your research budget, this is a nice way to show appreciation for their time and commitment. To keep everyone feeling fresh, consider offering snacks or drinks as well.

After concluding your focus group, you and your co-moderator should debrief, recording initial impressions of the discussion as well as any highlights, issues, or immediate conclusions you’ve drawn.

The next step is to transcribe and clean your data . Assign each participant a number or pseudonym for organizational purposes. Transcribe the recordings and conduct content analysis to look for themes or categories of responses. The categories you choose can then form the basis for reporting your results.

Just like other research methods, focus groups come with advantages and disadvantages.

- They are fairly straightforward to organize and results have strong face validity .

- They are usually inexpensive, even if you compensate participant.

- A focus group is much less time-consuming than a survey or experiment , and you get immediate results.

- Focus group results are often more comprehensible and intuitive than raw data.

Disadvantages

- It can be difficult to assemble a truly representative sample. Focus groups are generally not considered externally valid due to their small sample sizes.

- Due to the small sample size, you cannot ensure the anonymity of respondents, which may influence their desire to speak freely.

- Depth of analysis can be a concern, as it can be challenging to get honest opinions on controversial topics.

- There is a lot of room for error in the data analysis and high potential for observer dependency in drawing conclusions. You have to be careful not to cherry-pick responses to fit a prior conclusion.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest. It is one of 4 types of interviews .

As a rule of thumb, questions related to thoughts, beliefs, and feelings work well in focus groups. Take your time formulating strong questions, paying special attention to phrasing. Be careful to avoid leading questions , which can bias your responses.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Every dataset requires different techniques to clean dirty data , but you need to address these issues in a systematic way. You focus on finding and resolving data points that don’t agree or fit with the rest of your dataset.

These data might be missing values, outliers, duplicate values, incorrectly formatted, or irrelevant. You’ll start with screening and diagnosing your data. Then, you’ll often standardize and accept or remove data to make your dataset consistent and valid.

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

It’s impossible to completely avoid observer bias in studies where data collection is done or recorded manually, but you can take steps to reduce this type of bias in your research .

Scope of research is determined at the beginning of your research process , prior to the data collection stage. Sometimes called “scope of study,” your scope delineates what will and will not be covered in your project. It helps you focus your work and your time, ensuring that you’ll be able to achieve your goals and outcomes.

Defining a scope can be very useful in any research project, from a research proposal to a thesis or dissertation . A scope is needed for all types of research: quantitative , qualitative , and mixed methods .

To define your scope of research, consider the following:

- Budget constraints or any specifics of grant funding

- Your proposed timeline and duration

- Specifics about your population of study, your proposed sample size , and the research methodology you’ll pursue

- Any inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Any anticipated control , extraneous , or confounding variables that could bias your research if not accounted for properly.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What is a Focus Group | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/focus-group/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is qualitative research | methods & examples, explanatory research | definition, guide, & examples, data collection | definition, methods & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

7 focus group examples for your next qualitative research project

Last updated

9 March 2023

Reviewed by

Jean Kaluza

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Qualitative research is a fact-finding method for exploring and understanding people's beliefs, attitudes, experiences, and behaviors.

It involves collecting and analyzing data for insights into complex phenomena and social issues.

Researchers take this detailed data and analyze it using techniques such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory to identify patterns and themes in the data.

Qualitative research can inform policies, design interventions, or improve services.

Analyze focus group sessions

Dovetail streamlines focus group research to help you understand the responses and find patterns faster

- What is a focus group?

A focus group is a qualitative fact-finding method involving a small group of five to 10 people discussing a specific topic or issue. A moderator leads the group, poses open-ended questions, and encourages participant discussion and interaction.

A focus group aims to gain insights into participants' opinions, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors about the discussed topic.

Marketing research, product development, and social sciences use focus groups to understand consumer behavior, attitudes, and preferences. They can also explore social issues, gather feedback on new ideas, or evaluate the effectiveness of a program or intervention.

You can conduct in-person or online focus groups and record and transcribe the sessions for analysis. You use thematic or content analysis to analyze the data and identify patterns in the participants' responses.

- Why do researchers use focus groups?

Researchers use focus groups for various reasons, primarily to gain qualitative insights and opinions from people with similar characteristics.

Here are other reasons for focus groups:

Understand consumer behavior

Focus groups are ideal in marketing research for gathering insights into consumer preferences and behavior. Researchers can better understand what motivates their target audience, needs, wants, and what drives their purchasing decisions.

Gather feedback on new ideas

Focus groups can gather feedback on new products, services, or ideas. Researchers can present a new concept to a focus group and ask for their opinions to see how well they receive the idea. They can also learn what changes might be necessary and the potential market.

Evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions

Focus groups can help evaluate the effectiveness of a program or intervention. Researchers can ask participants to share their experiences and opinions to gain insights into their experience with the program. They can determine what aspects of the program work well, what could be improved, and its impact on participants.

Explore social issues

Focus groups can help explore social issues, such as attitudes toward a particular topic or the impact of a social program. Bringing together a diverse group of people can help researchers gain a more nuanced understanding of the issue and identify potential solutions or interventions.

Focus groups are a helpful tool for gaining qualitative insights and opinions from people with shared attributes. You can use these groups in different settings, and they’re handy for exploring complex issues that require in-depth understanding.

When should you use a focus group?

Here are some situations where a focus group might be appropriate:

If you’re launching a new product or service and want to gather feedback on your concept, features, and branding

To better understand your target audience's behavior, attitudes, and partiality by helping you identify patterns and trends in their decision-making

When you want to evaluate the effectiveness of a program or intervention by understanding the participant's experiences and opinions

If you want to develop effective marketing strategies with insights into what resonates with your target audience

When you want to explore social issues, such as the impact of a social program, and gain a deeper understanding of the issue at hand

Focus groups are less useful for situations where you need quantitative data or a representative sample of the broader population. It's essential to carefully plan your focus group, including selecting willing participants, choosing a moderator, and developing a discussion guide to achieve your research goals.

- 7 examples of focus groups

Researchers can use focus groups in different settings to gather feedback and opinions on products, services, or topics. Here are some examples of focus groups:

1. Product testing

Marketers can use a focus group to test a new product. For example, a company plans to launch a new line of skincare products and wants to get feedback from potential customers before the launch. The company organizes focus groups with participants who match their target market demographic and supplies a moderator with a discussion guide.

The moderator asks the focus group participants to try the products and provide feedback on the product's packaging, scent, texture, effectiveness, and overall appeal.

They question participants about their current skincare routine, what products they use, and what they look for in skincare products.

The company changes the product packaging, ingredients, and pricing based on feedback. This ensures the product meets the needs and preferences of the target market.

Now, the company can launch the new skincare line with confidence that its target market will love the product.

2. Advertising campaigns

Focus groups can test the success of advertising campaigns. Participants provide feedback on the ad's messaging, visuals, and tone, helping a company refine the campaign before launch.

For example, a brand organizes a focus group with participants who match their target demographic before launching their new advertising campaign.

If the focus group participants find the ad's message too complicated or unclear, the company can simplify the message based on feedback. This makes the ad more attractive and digestible for its target audience.

3. Political campaigns

Political participants can use focus groups to gather information about:

What issues are most important to voters

How voters feel about the candidate and their message

How the candidate can improve their message and campaign strategy

For example, a political campaign might convene a focus group of voters from a particular demographic, such as suburban women or young adults.

The leader might ask the focus group questions about their feelings and attitudes towards the candidate, the issues they care about most, and how they perceive the candidate's stance.

4. Market research

Marketers can use focus groups to gather information about consumers' likes and dislikes about a particular product or service. They can use this information to guide product development, marketing, and advertising strategies.

For example, a company forms a focus group to gather feedback on a new product concept, such as a new type of food packaging.

The moderator asks the focus group questions about their perceptions of the product, the likelihood of purchasing it, and any suggestions they have for improving it.

5. Product development

Focus groups can gather qualitative data from potential users or customers to understand their needs, preferences, and experiences with the product.

Companies can use focus groups at different stages, from the initial concept development to the testing and refinement of prototypes.

For example, a business gathers a focus group to provide feedback on a new music streaming service app, and participants answer questions about:

Their experiences with their current music streaming experiences

Preferences for layout

Impressions of the new streaming service

Product development teams can use this feedback to ensure the product meets the needs and expectations of the target market.

6. Healthcare

Healthcare focus groups can gather feedback and insights from patients, healthcare providers, and other stakeholders.

Healthcare providers can use focus groups to gather qualitative data on various topics, including patient experiences, healthcare delivery, policies, and products.

For example, a provider uses a focus group to gather feedback on a new healthcare policy related to access to care. Participants answer questions about their experiences accessing healthcare, opinions on the policy, and any suggestions for improvements.

7. Education

Educators can use focus groups to get insights into student experiences and preferences to improve the quality of education and student engagement.

Focus groups can also collect feedback from teachers and parents on issues such as teaching methods, parental involvement, and student performance.

Decision-makers can use this feedback to improve curriculum development, teaching methods, school policies, and educational products to meet the needs of students and educators.

- The pros and cons of focus groups

Focus groups are a popular research method to gather feedback and opinions from small, diverse groups. While focus groups can provide valuable insights, they also have drawbacks.

Provides in-depth insights

Focus groups allow in-depth discussions and more comprehensive insights into a topic. Participants can provide detailed feedback and share their opinions, attitudes, and experiences.

Encourages group dynamics

Focus groups encourage participants to interact and discuss the topic with each other, generating new ideas and insights. Participants can build on each other's thoughts and ideas, leading to a more extensive and nuanced discussion.

Cost-effective

Conducting a focus group can be less expensive than other research methods, such as one-on-one interviews or surveys . It can be more cost-effective to gather a group in one location rather than travel to different locations to conduct individual interviews.

Can be used to test ideas

Focus groups can test new ideas, products, or services before they launch. It allows companies to gather feedback from potential customers, enabling more informed decisions.

Flexibility

Researchers can adapt focus groups to various topics and settings, from academic research to market research.

The moderator can conduct focus groups quickly, making them a valuable tool for gathering data in a short amount of time.

Small sample size

Focus groups usually involve a small number of participants. The opinions of a focus group may not represent the broader population.

Potential bias

Group dynamics can influence the opinions and attitudes of a focus group, so they may not reflect the opinions of individual participants.

Limited scope

Focus groups may only provide insights into a specific topic or product instead of broader insights into consumer behavior or attitudes.

Time-consuming

Conducting a focus group can be time-consuming, as it requires organizing and scheduling participants, setting up a location, and analyzing the data.

Interpretation

The interpretation of focus group data can be subjective and dependent on the researcher's perspective and biases.

Researchers should use focus groups and other research methods to ensure comprehensive and accurate findings.

- How do you run a focus group?

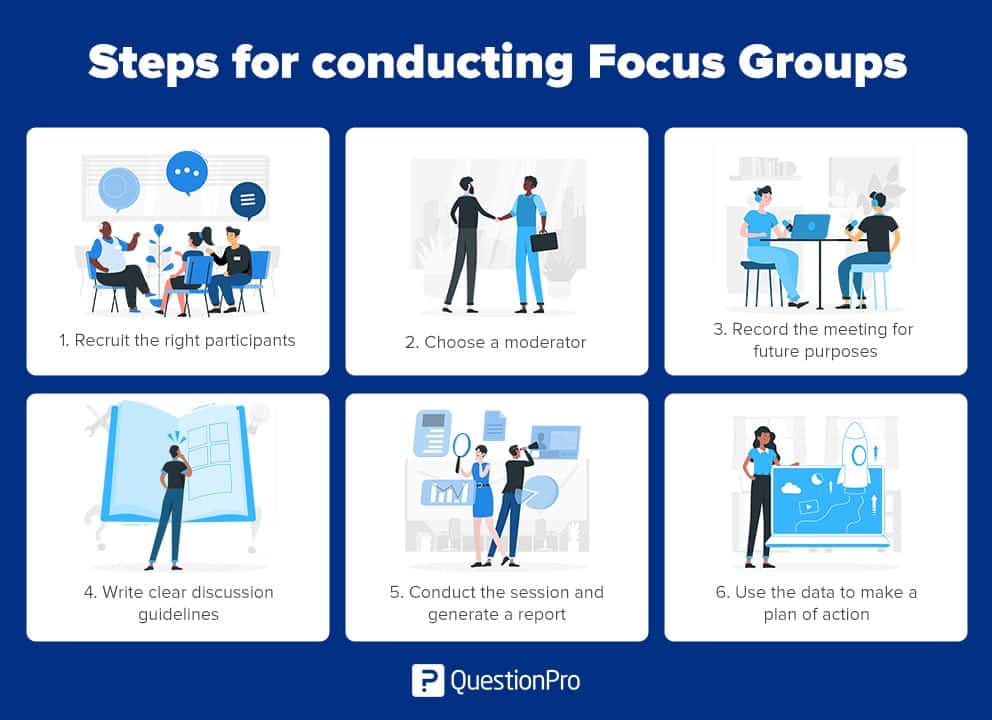

Here are some steps to follow when running a focus group:

Before planning your focus group, define your research objectives and determine what you hope to achieve through the focus group.

Determine your target audience by categorizing them with common characteristics to provide the necessary insights.

Identify potential participants that fit your target audience, offer an incentive to encourage participation, and recruit them for the focus group.

Select a skilled moderator to facilitate the discussion and keep it focused. The moderator should understand qualitative research techniques and have good interpersonal skills.

Develop a discussion guide outlining the questions for the focus group. The questions should elicit insights and opinions from participants on the research objectives.

Hold the focus group in a comfortable, quiet location. Introduce the moderator and explain the purpose of the focus group. The moderator should guide the discussion, asking questions from the discussion guide and encouraging participation from everyone.

Record the discussion using audio or video recording equipment. Consider taking notes during the discussion to capture critical points.

Transcribe the audio or video recording and analyze the data to identify patterns and themes.

Use the data to draw conclusions and make recommendations based on the research objectives. Use techniques such as content analysis , thematic analysis , or grounded theory to identify patterns and themes in the data.

Prepare a report summarizing the findings of the focus group and provide recommendations based on the research objectives.

Follow these steps to conduct a successful focus group, uncover valuable insights, and achieve your research objectives.

- Five sample focus group questions

Here are some sample focus group questions that you could use in different research contexts avoiding leading questions and emphasizing open-ended questions:

1. Exploring a new product or service:

What are your first impressions of this product/service?

What do you like/dislike about the product/service?

How does this product/service compare to similar products/services?

What improvements could we make to the product/service?

2. Understanding consumer behavior:

What factors influence your decision to purchase a product/service?

How do you typically research products/services before making a purchase?

How do you feel about the pricing of products/services?

How do you use technology when shopping for products/services?

3. Evaluating the effectiveness of a program or intervention:

What do you think are the strengths of the program/intervention?

What challenges have you faced in participating in the program/intervention?

How has the program/intervention impacted your life?

What changes would you recommend to improve the program/intervention?

4. Developing marketing strategies:

What messages do you think would resonate with your target audience?

What channels do you think are most effective for reaching your target audience?

What motivates your target audience to make a purchase?

How do you think your target audience perceives your brand?

5. Exploring social issues:

What are your attitudes toward [topic]?

How has [topic] impacted your life or those you know?

What are some potential solutions to address [topic]?

What are some barriers to addressing [topic]?

These are just a few examples of questions that you could use in focus groups. Carefully design questions relevant to the research objectives that elicit meaningful participant insights.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Privacy Policy

Home » Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Focus Group

Definition:

A focus group is a qualitative research method used to gather in-depth insights and opinions from a group of individuals about a particular product, service, concept, or idea.

The focus group typically consists of 6-10 participants who are selected based on shared characteristics such as demographics, interests, or experiences. The discussion is moderated by a trained facilitator who asks open-ended questions to encourage participants to share their thoughts, feelings, and attitudes towards the topic.

Focus groups are an effective way to gather detailed information about consumer behavior, attitudes, and perceptions, and can provide valuable insights to inform decision-making in a range of fields including marketing, product development, and public policy.

Types of Focus Group

The following are some types or methods of Focus Groups:

Traditional Focus Group

This is the most common type of focus group, where a small group of people is brought together to discuss a particular topic. The discussion is typically led by a skilled facilitator who asks open-ended questions to encourage participants to share their thoughts and opinions.

Mini Focus Group

A mini-focus group involves a smaller group of participants, typically 3 to 5 people. This type of focus group is useful when the topic being discussed is particularly sensitive or when the participants are difficult to recruit.

Dual Moderator Focus Group

In a dual-moderator focus group, two facilitators are used to manage the discussion. This can help to ensure that the discussion stays on track and that all participants have an opportunity to share their opinions.

Teleconference or Online Focus Group

Teleconferences or online focus groups are conducted using video conferencing technology or online discussion forums. This allows participants to join the discussion from anywhere in the world, making it easier to recruit participants and reducing the cost of conducting the focus group.

Client-led Focus Group

In a client-led focus group, the client who is commissioning the research takes an active role in the discussion. This type of focus group is useful when the client has specific questions they want to ask or when they want to gain a deeper understanding of their customers.

The following Table can explain Focus Group types more clearly

| Type of Focus Group | Number of Participants | Duration | Types of Questions | Geographical Area | Analysis Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | 6-12 | 1-2 hours | Open-ended | Local | Thematic Analysis |

| Mini | 3-5 | 1-2 hours | Closed-ended | Local | Content Analysis |

| Dual Moderator | 6-12 | 1-2 hours | Combination of open- and closed-ended | Regional | Discourse Analysis |

| Teleconference/Online | 6-12 | 1-2 hours | Open-ended | National/International | Conversation Analysis |

| Client-Led | 6-12 | 1-2 hours | Combination of open- and closed-ended | Local/Regional | Thematic Analy |

How To Conduct a Focus Group

To conduct a focus group, follow these general steps:

Define the Research Question

Identify the key research question or objective that you want to explore through the focus group. Develop a discussion guide that outlines the topics and questions you want to cover during the session.

Recruit Participants

Identify the target audience for the focus group and recruit participants who meet the eligibility criteria. You can use various recruitment methods such as social media, online panels, or referrals from existing customers.

Select a Venue

Choose a location that is convenient for the participants and has the necessary facilities such as audio-visual equipment, seating, and refreshments.

Conduct the Session

During the focus group session, introduce the topic, and review the objectives of the research. Encourage participants to share their thoughts and opinions by asking open-ended questions and probing deeper into their responses. Ensure that the discussion remains on topic and that all participants have an opportunity to contribute.

Record the Session

Use audio or video recording equipment to capture the discussion. Note-taking is also essential to ensure that you capture all key points and insights.

Analyze the data

Once the focus group is complete, transcribe and analyze the data. Look for common themes, patterns, and insights that emerge from the discussion. Use this information to generate insights and recommendations that can be applied to the research question.

When to use Focus Group Method

The focus group method is typically used in the following situations:

Exploratory Research

When a researcher wants to explore a new or complex topic in-depth, focus groups can be used to generate ideas, opinions, and insights.

Product Development

Focus groups are often used to gather feedback from consumers about new products or product features to help identify potential areas for improvement.

Marketing Research

Focus groups can be used to test marketing concepts, messaging, or advertising campaigns to determine their effectiveness and appeal to different target audiences.

Customer Feedback

Focus groups can be used to gather feedback from customers about their experiences with a particular product or service, helping companies improve customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Public Policy Research

Focus groups can be used to gather public opinions and attitudes on social or political issues, helping policymakers make more informed decisions.

Examples of Focus Group

Here are some real-time examples of focus groups:

- A tech company wants to improve the user experience of their mobile app. They conduct a focus group with a diverse group of users to gather feedback on the app’s design, functionality, and features. The focus group consists of 8 participants who are selected based on their age, gender, ethnicity, and level of experience with the app. During the session, a trained facilitator asks open-ended questions to encourage participants to share their thoughts and opinions on the app. The facilitator also observes the participants’ behavior and reactions to the app’s features. After the focus group, the data is analyzed to identify common themes and issues raised by the participants. The insights gathered from the focus group are used to inform improvements to the app’s design and functionality, with the goal of creating a more user-friendly and engaging experience for all users.

- A car manufacturer wants to develop a new electric vehicle that appeals to a younger demographic. They conduct a focus group with millennials to gather their opinions on the design, features, and pricing of the vehicle.

- A political campaign team wants to develop effective messaging for their candidate’s campaign. They conduct a focus group with voters to gather their opinions on key issues and identify the most persuasive arguments and messages.

- A restaurant chain wants to develop a new menu that appeals to health-conscious customers. They conduct a focus group with fitness enthusiasts to gather their opinions on the types of food and drinks that they would like to see on the menu.

- A healthcare organization wants to develop a new wellness program for their employees. They conduct a focus group with employees to gather their opinions on the types of programs, incentives, and support that would be most effective in promoting healthy behaviors.

- A clothing retailer wants to develop a new line of sustainable and eco-friendly clothing. They conduct a focus group with environmentally conscious consumers to gather their opinions on the design, materials, and pricing of the clothing.

Purpose of Focus Group

The key objectives of a focus group include:

Generating New Ideas and insights

Focus groups are used to explore new or complex topics in-depth, generating new ideas and insights that may not have been previously considered.

Understanding Consumer Behavior

Focus groups can be used to gather information on consumer behavior, attitudes, and perceptions to inform marketing and product development strategies.

Testing Concepts and Ideas

Focus groups can be used to test marketing concepts, messaging, or product prototypes to determine their effectiveness and appeal to different target audiences.

Gathering Customer Feedback

Informing decision-making.

Focus groups can provide valuable insights to inform decision-making in a range of fields including marketing, product development, and public policy.

Advantages of Focus Group

The advantages of using focus groups are:

- In-depth insights: Focus groups provide in-depth insights into the attitudes, opinions, and behaviors of a target audience on a specific topic, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the issues being explored.

- Group dynamics: The group dynamics of focus groups can provide additional insights, as participants may build on each other’s ideas, share experiences, and debate different perspectives.

- Efficient data collection: Focus groups are an efficient way to collect data from multiple individuals at the same time, making them a cost-effective method of research.

- Flexibility : Focus groups can be adapted to suit a range of research objectives, from exploratory research to concept testing and customer feedback.

- Real-time feedback: Focus groups provide real-time feedback on new products or concepts, allowing researchers to make immediate adjustments and improvements based on participant feedback.

- Participant engagement: Focus groups can be a more engaging and interactive research method than surveys or other quantitative methods, as participants have the opportunity to express their opinions and interact with other participants.

Limitations of Focus Groups

While focus groups can provide valuable insights, there are also some limitations to using them.

- Small sample size: Focus groups typically involve a small number of participants, which may not be representative of the broader population being studied.

- Group dynamics : While group dynamics can be an advantage of focus groups, they can also be a limitation, as dominant personalities may sway the discussion or participants may not feel comfortable expressing their true opinions.

- Limited generalizability : Because focus groups involve a small sample size, the results may not be generalizable to the broader population.

- Limited depth of responses: Because focus groups are time-limited, participants may not have the opportunity to fully explore or elaborate on their opinions or experiences.

- Potential for bias: The facilitator of a focus group may inadvertently influence the discussion or the selection of participants may not be representative, leading to potential bias in the results.

- Difficulty in analysis : The qualitative data collected in focus groups can be difficult to analyze, as it is often subjective and requires a skilled researcher to interpret and identify themes.

Characteristics of Focus Group

- Small group size: Focus groups typically involve a small number of participants, ranging from 6 to 12 people. This allows for a more in-depth and focused discussion.

- Targeted participants: Participants in focus groups are selected based on specific criteria, such as age, gender, or experience with a particular product or service.

- Facilitated discussion: A skilled facilitator leads the discussion, asking open-ended questions and encouraging participants to share their thoughts and experiences.

- I nteractive and conversational: Focus groups are interactive and conversational, with participants building on each other’s ideas and responding to one another’s opinions.

- Qualitative data: The data collected in focus groups is qualitative, providing detailed insights into participants’ attitudes, opinions, and behaviors.

- Non-threatening environment: Participants are encouraged to share their thoughts and experiences in a non-threatening and supportive environment.

- Limited time frame: Focus groups are typically time-limited, lasting between 1 and 2 hours, to ensure that the discussion stays focused and productive.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

Textual Analysis – Types, Examples and Guide

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Basic Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 05 October 2018

Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: an update for the digital age

- P. Gill 1 &

- J. Baillie 2

British Dental Journal volume 225 , pages 668–672 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

63 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Highlights that qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry. Interviews and focus groups remain the most common qualitative methods of data collection.

Suggests the advent of digital technologies has transformed how qualitative research can now be undertaken.

Suggests interviews and focus groups can offer significant, meaningful insight into participants' experiences, beliefs and perspectives, which can help to inform developments in dental practice.

Qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry, due to its potential to provide meaningful, in-depth insights into participants' experiences, perspectives, beliefs and behaviours. These insights can subsequently help to inform developments in dental practice and further related research. The most common methods of data collection used in qualitative research are interviews and focus groups. While these are primarily conducted face-to-face, the ongoing evolution of digital technologies, such as video chat and online forums, has further transformed these methods of data collection. This paper therefore discusses interviews and focus groups in detail, outlines how they can be used in practice, how digital technologies can further inform the data collection process, and what these methods can offer dentistry.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Interviews in the social sciences

Professionalism in dentistry: deconstructing common terminology

A review of technical and quality assessment considerations of audio-visual and web-conferencing focus groups in qualitative health research, introduction.

Traditionally, research in dentistry has primarily been quantitative in nature. 1 However, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in qualitative research within the profession, due to its potential to further inform developments in practice, policy, education and training. Consequently, in 2008, the British Dental Journal (BDJ) published a four paper qualitative research series, 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 to help increase awareness and understanding of this particular methodological approach.

Since the papers were originally published, two scoping reviews have demonstrated the ongoing proliferation in the use of qualitative research within the field of oral healthcare. 1 , 6 To date, the original four paper series continue to be well cited and two of the main papers remain widely accessed among the BDJ readership. 2 , 3 The potential value of well-conducted qualitative research to evidence-based practice is now also widely recognised by service providers, policy makers, funding bodies and those who commission, support and use healthcare research.

Besides increasing standalone use, qualitative methods are now also routinely incorporated into larger mixed method study designs, such as clinical trials, as they can offer additional, meaningful insights into complex problems that simply could not be provided by quantitative methods alone. Qualitative methods can also be used to further facilitate in-depth understanding of important aspects of clinical trial processes, such as recruitment. For example, Ellis et al . investigated why edentulous older patients, dissatisfied with conventional dentures, decline implant treatment, despite its established efficacy, and frequently refuse to participate in related randomised clinical trials, even when financial constraints are removed. 7 Through the use of focus groups in Canada and the UK, the authors found that fears of pain and potential complications, along with perceived embarrassment, exacerbated by age, are common reasons why older patients typically refuse dental implants. 7

The last decade has also seen further developments in qualitative research, due to the ongoing evolution of digital technologies. These developments have transformed how researchers can access and share information, communicate and collaborate, recruit and engage participants, collect and analyse data and disseminate and translate research findings. 8 Where appropriate, such technologies are therefore capable of extending and enhancing how qualitative research is undertaken. 9 For example, it is now possible to collect qualitative data via instant messaging, email or online/video chat, using appropriate online platforms.

These innovative approaches to research are therefore cost-effective, convenient, reduce geographical constraints and are often useful for accessing 'hard to reach' participants (for example, those who are immobile or socially isolated). 8 , 9 However, digital technologies are still relatively new and constantly evolving and therefore present a variety of pragmatic and methodological challenges. Furthermore, given their very nature, their use in many qualitative studies and/or with certain participant groups may be inappropriate and should therefore always be carefully considered. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a detailed explication regarding the use of digital technologies in qualitative research, insight is provided into how such technologies can be used to facilitate the data collection process in interviews and focus groups.

In light of such developments, it is perhaps therefore timely to update the main paper 3 of the original BDJ series. As with the previous publications, this paper has been purposely written in an accessible style, to enhance readability, particularly for those who are new to qualitative research. While the focus remains on the most common qualitative methods of data collection – interviews and focus groups – appropriate revisions have been made to provide a novel perspective, and should therefore be helpful to those who would like to know more about qualitative research. This paper specifically focuses on undertaking qualitative research with adult participants only.

Overview of qualitative research

Qualitative research is an approach that focuses on people and their experiences, behaviours and opinions. 10 , 11 The qualitative researcher seeks to answer questions of 'how' and 'why', providing detailed insight and understanding, 11 which quantitative methods cannot reach. 12 Within qualitative research, there are distinct methodologies influencing how the researcher approaches the research question, data collection and data analysis. 13 For example, phenomenological studies focus on the lived experience of individuals, explored through their description of the phenomenon. Ethnographic studies explore the culture of a group and typically involve the use of multiple methods to uncover the issues. 14

While methodology is the 'thinking tool', the methods are the 'doing tools'; 13 the ways in which data are collected and analysed. There are multiple qualitative data collection methods, including interviews, focus groups, observations, documentary analysis, participant diaries, photography and videography. Two of the most commonly used qualitative methods are interviews and focus groups, which are explored in this article. The data generated through these methods can be analysed in one of many ways, according to the methodological approach chosen. A common approach is thematic data analysis, involving the identification of themes and subthemes across the data set. Further information on approaches to qualitative data analysis has been discussed elsewhere. 1

Qualitative research is an evolving and adaptable approach, used by different disciplines for different purposes. Traditionally, qualitative data, specifically interviews, focus groups and observations, have been collected face-to-face with participants. In more recent years, digital technologies have contributed to the ongoing evolution of qualitative research. Digital technologies offer researchers different ways of recruiting participants and collecting data, and offer participants opportunities to be involved in research that is not necessarily face-to-face.

Research interviews are a fundamental qualitative research method 15 and are utilised across methodological approaches. Interviews enable the researcher to learn in depth about the perspectives, experiences, beliefs and motivations of the participant. 3 , 16 Examples include, exploring patients' perspectives of fear/anxiety triggers in dental treatment, 17 patients' experiences of oral health and diabetes, 18 and dental students' motivations for their choice of career. 19

Interviews may be structured, semi-structured or unstructured, 3 according to the purpose of the study, with less structured interviews facilitating a more in depth and flexible interviewing approach. 20 Structured interviews are similar to verbal questionnaires and are used if the researcher requires clarification on a topic; however they produce less in-depth data about a participant's experience. 3 Unstructured interviews may be used when little is known about a topic and involves the researcher asking an opening question; 3 the participant then leads the discussion. 20 Semi-structured interviews are commonly used in healthcare research, enabling the researcher to ask predetermined questions, 20 while ensuring the participant discusses issues they feel are important.

Interviews can be undertaken face-to-face or using digital methods when the researcher and participant are in different locations. Audio-recording the interview, with the consent of the participant, is essential for all interviews regardless of the medium as it enables accurate transcription; the process of turning the audio file into a word-for-word transcript. This transcript is the data, which the researcher then analyses according to the chosen approach.

Types of interview

Qualitative studies often utilise one-to-one, face-to-face interviews with research participants. This involves arranging a mutually convenient time and place to meet the participant, signing a consent form and audio-recording the interview. However, digital technologies have expanded the potential for interviews in research, enabling individuals to participate in qualitative research regardless of location.

Telephone interviews can be a useful alternative to face-to-face interviews and are commonly used in qualitative research. They enable participants from different geographical areas to participate and may be less onerous for participants than meeting a researcher in person. 15 A qualitative study explored patients' perspectives of dental implants and utilised telephone interviews due to the quality of the data that could be yielded. 21 The researcher needs to consider how they will audio record the interview, which can be facilitated by purchasing a recorder that connects directly to the telephone. One potential disadvantage of telephone interviews is the inability of the interviewer and researcher to see each other. This is resolved using software for audio and video calls online – such as Skype – to conduct interviews with participants in qualitative studies. Advantages of this approach include being able to see the participant if video calls are used, enabling observation of non-verbal communication, and the software can be free to use. However, participants are required to have a device and internet connection, as well as being computer literate, potentially limiting who can participate in the study. One qualitative study explored the role of dental hygienists in reducing oral health disparities in Canada. 22 The researcher conducted interviews using Skype, which enabled dental hygienists from across Canada to be interviewed within the research budget, accommodating the participants' schedules. 22

A less commonly used approach to qualitative interviews is the use of social virtual worlds. A qualitative study accessed a social virtual world – Second Life – to explore the health literacy skills of individuals who use social virtual worlds to access health information. 23 The researcher created an avatar and interview room, and undertook interviews with participants using voice and text methods. 23 This approach to recruitment and data collection enables individuals from diverse geographical locations to participate, while remaining anonymous if they wish. Furthermore, for interviews conducted using text methods, transcription of the interview is not required as the researcher can save the written conversation with the participant, with the participant's consent. However, the researcher and participant need to be familiar with how the social virtual world works to engage in an interview this way.

Conducting an interview

Ensuring informed consent before any interview is a fundamental aspect of the research process. Participants in research must be afforded autonomy and respect; consent should be informed and voluntary. 24 Individuals should have the opportunity to read an information sheet about the study, ask questions, understand how their data will be stored and used, and know that they are free to withdraw at any point without reprisal. The qualitative researcher should take written consent before undertaking the interview. In a face-to-face interview, this is straightforward: the researcher and participant both sign copies of the consent form, keeping one each. However, this approach is less straightforward when the researcher and participant do not meet in person. A recent protocol paper outlined an approach for taking consent for telephone interviews, which involved: audio recording the participant agreeing to each point on the consent form; the researcher signing the consent form and keeping a copy; and posting a copy to the participant. 25 This process could be replicated in other interview studies using digital methods.

There are advantages and disadvantages of using face-to-face and digital methods for research interviews. Ultimately, for both approaches, the quality of the interview is determined by the researcher. 16 Appropriate training and preparation are thus required. Healthcare professionals can use their interpersonal communication skills when undertaking a research interview, particularly questioning, listening and conversing. 3 However, the purpose of an interview is to gain information about the study topic, 26 rather than offering help and advice. 3 The researcher therefore needs to listen attentively to participants, enabling them to describe their experience without interruption. 3 The use of active listening skills also help to facilitate the interview. 14 Spradley outlined elements and strategies for research interviews, 27 which are a useful guide for qualitative researchers:

Greeting and explaining the project/interview

Asking descriptive (broad), structural (explore response to descriptive) and contrast (difference between) questions

Asymmetry between the researcher and participant talking

Expressing interest and cultural ignorance

Repeating, restating and incorporating the participant's words when asking questions

Creating hypothetical situations

Asking friendly questions

Knowing when to leave.

For semi-structured interviews, a topic guide (also called an interview schedule) is used to guide the content of the interview – an example of a topic guide is outlined in Box 1 . The topic guide, usually based on the research questions, existing literature and, for healthcare professionals, their clinical experience, is developed by the research team. The topic guide should include open ended questions that elicit in-depth information, and offer participants the opportunity to talk about issues important to them. This is vital in qualitative research where the researcher is interested in exploring the experiences and perspectives of participants. It can be useful for qualitative researchers to pilot the topic guide with the first participants, 10 to ensure the questions are relevant and understandable, and amending the questions if required.

Regardless of the medium of interview, the researcher must consider the setting of the interview. For face-to-face interviews, this could be in the participant's home, in an office or another mutually convenient location. A quiet location is preferable to promote confidentiality, enable the researcher and participant to concentrate on the conversation, and to facilitate accurate audio-recording of the interview. For interviews using digital methods the same principles apply: a quiet, private space where the researcher and participant feel comfortable and confident to participate in an interview.

Box 1: Example of a topic guide

Study focus: Parents' experiences of brushing their child's (aged 0–5) teeth

1. Can you tell me about your experience of cleaning your child's teeth?

How old was your child when you started cleaning their teeth?

Why did you start cleaning their teeth at that point?

How often do you brush their teeth?

What do you use to brush their teeth and why?

2. Could you explain how you find cleaning your child's teeth?

Do you find anything difficult?

What makes cleaning their teeth easier for you?

3. How has your experience of cleaning your child's teeth changed over time?

Has it become easier or harder?

Have you changed how often and how you clean their teeth? If so, why?

4. Could you describe how your child finds having their teeth cleaned?

What do they enjoy about having their teeth cleaned?

Is there anything they find upsetting about having their teeth cleaned?

5. Where do you look for information/advice about cleaning your child's teeth?

What did your health visitor tell you about cleaning your child's teeth? (If anything)

What has the dentist told you about caring for your child's teeth? (If visited)

Have any family members given you advice about how to clean your child's teeth? If so, what did they tell you? Did you follow their advice?

6. Is there anything else you would like to discuss about this?

Focus groups

A focus group is a moderated group discussion on a pre-defined topic, for research purposes. 28 , 29 While not aligned to a particular qualitative methodology (for example, grounded theory or phenomenology) as such, focus groups are used increasingly in healthcare research, as they are useful for exploring collective perspectives, attitudes, behaviours and experiences. Consequently, they can yield rich, in-depth data and illuminate agreement and inconsistencies 28 within and, where appropriate, between groups. Examples include public perceptions of dental implants and subsequent impact on help-seeking and decision making, 30 and general dental practitioners' views on patient safety in dentistry. 31

Focus groups can be used alone or in conjunction with other methods, such as interviews or observations, and can therefore help to confirm, extend or enrich understanding and provide alternative insights. 28 The social interaction between participants often results in lively discussion and can therefore facilitate the collection of rich, meaningful data. However, they are complex to organise and manage, due to the number of participants, and may also be inappropriate for exploring particularly sensitive issues that many participants may feel uncomfortable about discussing in a group environment.

Focus groups are primarily undertaken face-to-face but can now also be undertaken online, using appropriate technologies such as email, bulletin boards, online research communities, chat rooms, discussion forums, social media and video conferencing. 32 Using such technologies, data collection can also be synchronous (for example, online discussions in 'real time') or, unlike traditional face-to-face focus groups, asynchronous (for example, online/email discussions in 'non-real time'). While many of the fundamental principles of focus group research are the same, regardless of how they are conducted, a number of subtle nuances are associated with the online medium. 32 Some of which are discussed further in the following sections.

Focus group considerations

Some key considerations associated with face-to-face focus groups are: how many participants are required; should participants within each group know each other (or not) and how many focus groups are needed within a single study? These issues are much debated and there is no definitive answer. However, the number of focus groups required will largely depend on the topic area, the depth and breadth of data needed, the desired level of participation required 29 and the necessity (or not) for data saturation.

The optimum group size is around six to eight participants (excluding researchers) but can work effectively with between three and 14 participants. 3 If the group is too small, it may limit discussion, but if it is too large, it may become disorganised and difficult to manage. It is, however, prudent to over-recruit for a focus group by approximately two to three participants, to allow for potential non-attenders. For many researchers, particularly novice researchers, group size may also be informed by pragmatic considerations, such as the type of study, resources available and moderator experience. 28 Similar size and mix considerations exist for online focus groups. Typically, synchronous online focus groups will have around three to eight participants but, as the discussion does not happen simultaneously, asynchronous groups may have as many as 10–30 participants. 33

The topic area and potential group interaction should guide group composition considerations. Pre-existing groups, where participants know each other (for example, work colleagues) may be easier to recruit, have shared experiences and may enjoy a familiarity, which facilitates discussion and/or the ability to challenge each other courteously. 3 However, if there is a potential power imbalance within the group or if existing group norms and hierarchies may adversely affect the ability of participants to speak freely, then 'stranger groups' (that is, where participants do not already know each other) may be more appropriate. 34 , 35

Focus group management

Face-to-face focus groups should normally be conducted by two researchers; a moderator and an observer. 28 The moderator facilitates group discussion, while the observer typically monitors group dynamics, behaviours, non-verbal cues, seating arrangements and speaking order, which is essential for transcription and analysis. The same principles of informed consent, as discussed in the interview section, also apply to focus groups, regardless of medium. However, the consent process for online discussions will probably be managed somewhat differently. For example, while an appropriate participant information leaflet (and consent form) would still be required, the process is likely to be managed electronically (for example, via email) and would need to specifically address issues relating to technology (for example, anonymity and use, storage and access to online data). 32

The venue in which a face to face focus group is conducted should be of a suitable size, private, quiet, free from distractions and in a collectively convenient location. It should also be conducted at a time appropriate for participants, 28 as this is likely to promote attendance. As with interviews, the same ethical considerations apply (as discussed earlier). However, online focus groups may present additional ethical challenges associated with issues such as informed consent, appropriate access and secure data storage. Further guidance can be found elsewhere. 8 , 32

Before the focus group commences, the researchers should establish rapport with participants, as this will help to put them at ease and result in a more meaningful discussion. Consequently, researchers should introduce themselves, provide further clarity about the study and how the process will work in practice and outline the 'ground rules'. Ground rules are designed to assist, not hinder, group discussion and typically include: 3 , 28 , 29

Discussions within the group are confidential to the group

Only one person can speak at a time

All participants should have sufficient opportunity to contribute

There should be no unnecessary interruptions while someone is speaking

Everyone can be expected to be listened to and their views respected

Challenging contrary opinions is appropriate, but ridiculing is not.

Moderating a focus group requires considered management and good interpersonal skills to help guide the discussion and, where appropriate, keep it sufficiently focused. Avoid, therefore, participating, leading, expressing personal opinions or correcting participants' knowledge 3 , 28 as this may bias the process. A relaxed, interested demeanour will also help participants to feel comfortable and promote candid discourse. Moderators should also prevent the discussion being dominated by any one person, ensure differences of opinions are discussed fairly and, if required, encourage reticent participants to contribute. 3 Asking open questions, reflecting on significant issues, inviting further debate, probing responses accordingly, and seeking further clarification, as and where appropriate, will help to obtain sufficient depth and insight into the topic area.

Moderating online focus groups requires comparable skills, particularly if the discussion is synchronous, as the discussion may be dominated by those who can type proficiently. 36 It is therefore important that sufficient time and respect is accorded to those who may not be able to type as quickly. Asynchronous discussions are usually less problematic in this respect, as interactions are less instant. However, moderating an asynchronous discussion presents additional challenges, particularly if participants are geographically dispersed, as they may be online at different times. Consequently, the moderator will not always be present and the discussion may therefore need to occur over several days, which can be difficult to manage and facilitate and invariably requires considerable flexibility. 32 It is also worth recognising that establishing rapport with participants via online medium is often more challenging than via face-to-face and may therefore require additional time, skills, effort and consideration.

As with research interviews, focus groups should be guided by an appropriate interview schedule, as discussed earlier in the paper. For example, the schedule will usually be informed by the review of the literature and study aims, and will merely provide a topic guide to help inform subsequent discussions. To provide a verbatim account of the discussion, focus groups must be recorded, using an audio-recorder with a good quality multi-directional microphone. While videotaping is possible, some participants may find it obtrusive, 3 which may adversely affect group dynamics. The use (or not) of a video recorder, should therefore be carefully considered.

At the end of the focus group, a few minutes should be spent rounding up and reflecting on the discussion. 28 Depending on the topic area, it is possible that some participants may have revealed deeply personal issues and may therefore require further help and support, such as a constructive debrief or possibly even referral on to a relevant third party. It is also possible that some participants may feel that the discussion did not adequately reflect their views and, consequently, may no longer wish to be associated with the study. 28 Such occurrences are likely to be uncommon, but should they arise, it is important to further discuss any concerns and, if appropriate, offer them the opportunity to withdraw (including any data relating to them) from the study. Immediately after the discussion, researchers should compile notes regarding thoughts and ideas about the focus group, which can assist with data analysis and, if appropriate, any further data collection.