- Meet Fatimah Datoo

- Why Choose Us

- Student Success Stories

- Dental Hygiene Courses

- Dental Hygiene Exam Guide

- Video Lectures

- Becoming a Dental Hygienist

Dental Hygiene Made Easy

Your Path to Dental Hygiene Success Begins Here

Hello, I’m Fatimah Datoo, and I’m here to guide you on your journey to success in the field of dental hygiene. With years of experience as a dental hygiene educator, I understand the challenges and aspirations of students like you. Our mission is clear: To make dental hygiene education easy, accessible, effective, and fun

Meet Fatimah Datoo, RDH, BDScDH, MEd., EdD(c)

Hello, I’m Fatimah Datoo , and I’m here to guide you on your journey to success in the field of dental hygiene. With years of experience as a dental hygiene educator, I understand the challenges and aspirations of students like you. Our mission is clear: To make dental hygiene education easy, accessible, effective, and fun.

Master Complex Case Studies

Becoming a proficient dental hygienist means mastering case studies and problem-solving. Our immersive "Dental Hygiene Case Study Sessions" course is your ticket to sharpening your analytical skills, gaining clinical insights, and excelling in solving complex dental hygiene case studies. Join a diverse group of motivated peers and learn from experienced dental hygiene professors

In-Depth Client Case Studies

A key feature of our course is using dental hygiene textbooks that review case studies. The case studies we use offer a thorough health history, radiographs, periodontal assessments, and more that we will examine together to ensure we can best answer the case study questions.

Expert Guidance

Our Dental and Oral Health Case Studies course offers more than just theoretical knowledge; it's a platform for real-world application. Students will collaborate in the classroom in solving these intricate case studies.

Dental Hygiene Articles

Insights and Advice on Dental Care and Careers

How to Find the Best Dental Hygiene Tutor: From a Highly Credentialed Educator

- March 16, 2024

Continue reading

Learning Dentistry and Dental Hygiene: A Comprehensive Guide for Aspiring Hygienists

- January 7, 2024

How to Study for the National Dental Hygiene Board Exam (NDHBE/NDHCE)

- December 12, 2023

Exploring the Various Career Paths in Dental Hygiene

Effective Strategies for Dental Hygiene Board Exam Success

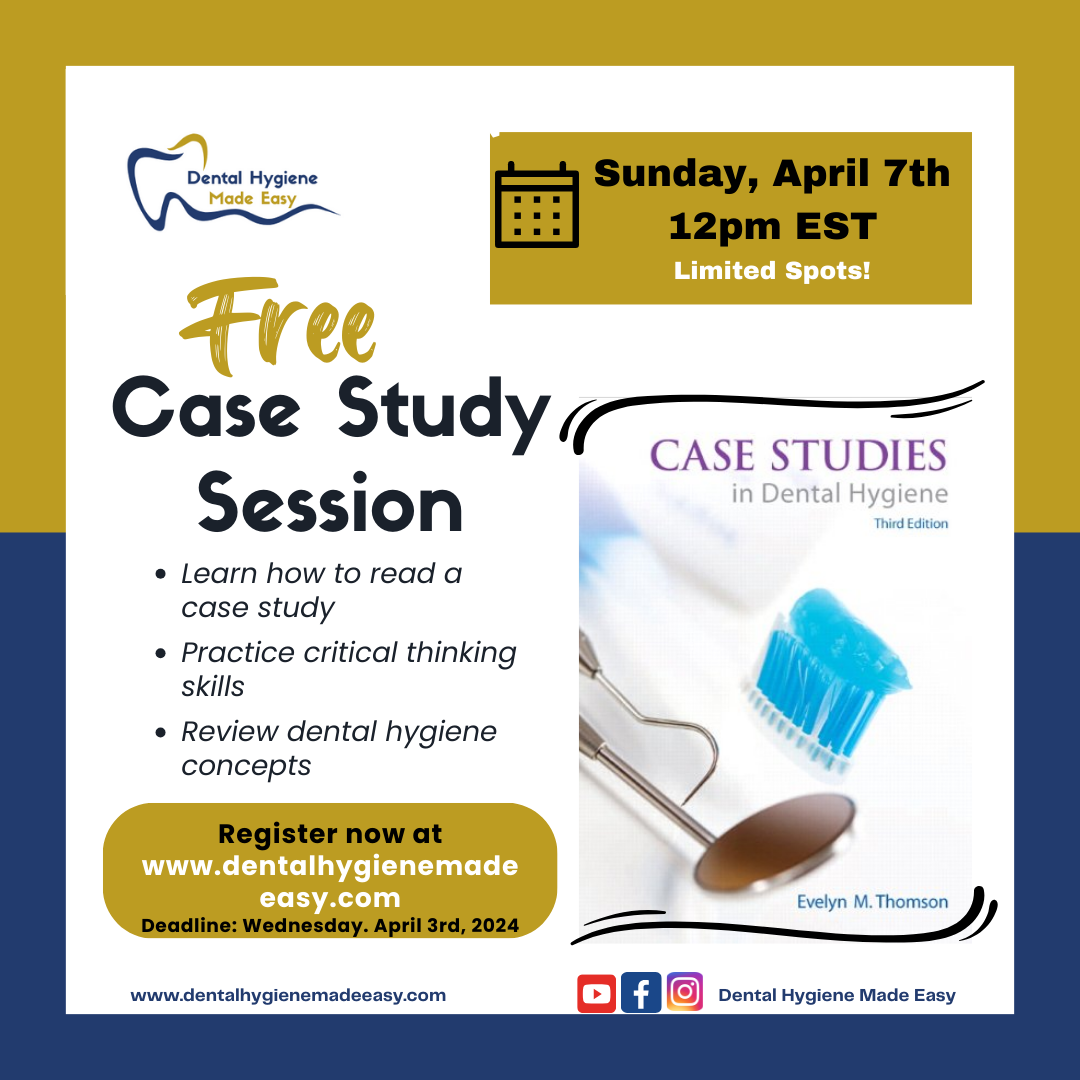

Free Case Study Session!

Unsure about signing up for our Dental Hygiene Made Easy board exam prep courses? Why not give our free case study session a try first and see if our teaching style suits you! During this session, we will thoroughly review a comprehensive case study and provide an opportunity to practice critical thinking skills when answering the questions. Don't miss out on this valuable FREE opportunity! Register now!

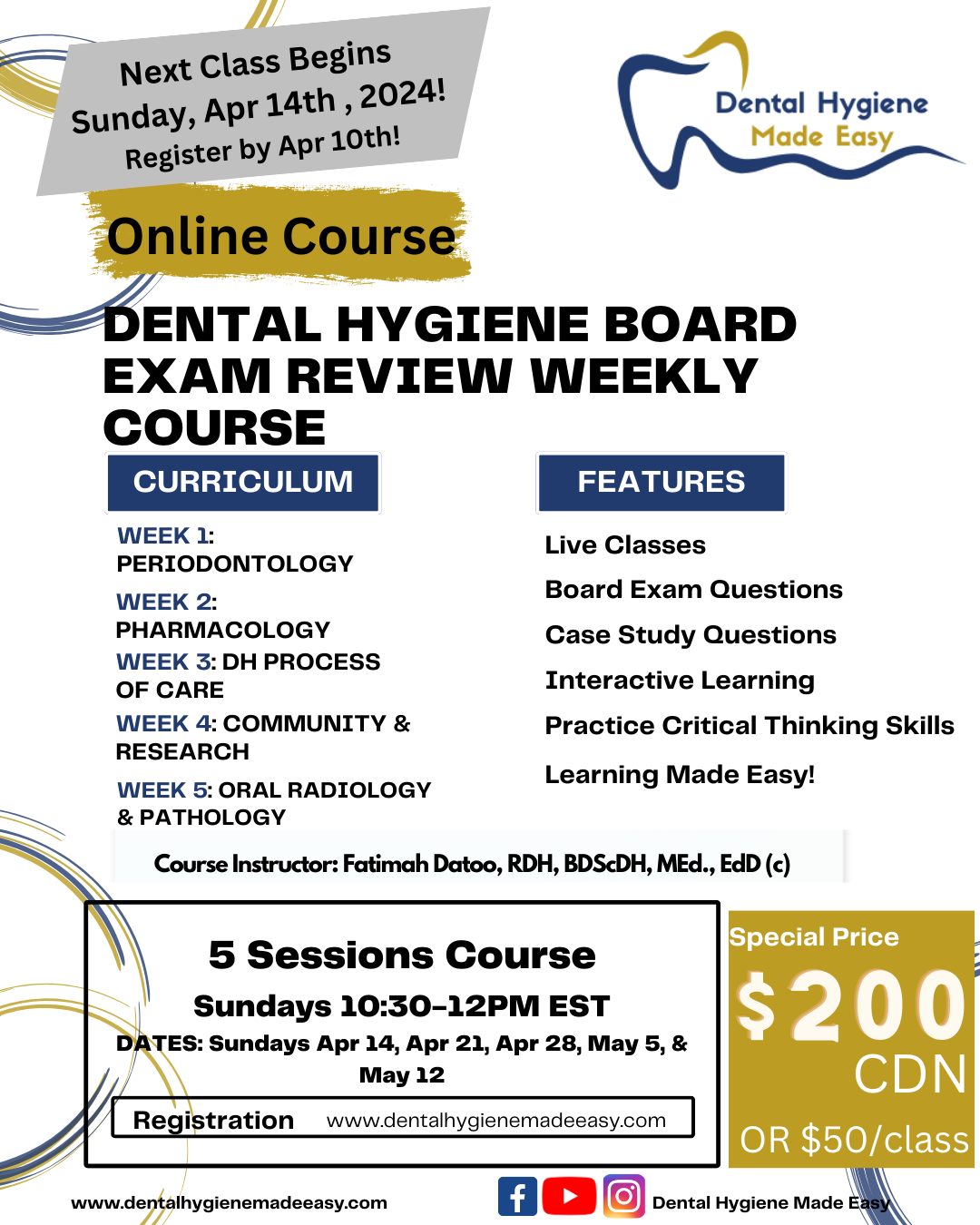

Mini-Board Exam Review Sessions

Elevate your dental hygiene board exam skills.

This course is strategically designed to elevate your capabilities in dental hygiene, whether you are approaching graduation or studying for the boards.

1. In-Depth Curriculum :

Master the critical concepts essential for excelling in the dental hygiene board exams.

2. Hands-On Learning

Engage in practical exercises involving board exam questions and case studies to apply your knowledge effectively.

3. Guided Expertise

Benefit from the tutelage of a seasoned dental hygiene educator committed to your success.

4. Resource-Rich Environment:

By registering for our affordably priced course, you’re taking a crucial step in securing your success in the upcoming Dental Hygiene Board Exam.

Case Study Sessions

This course is strategically designed to elevate your capabilities in dental hygiene, whether you are entering school or approaching graduation.

Affordable Board Exam Practice Online Sessions

Stressing over your Dental Hygiene Board Exam? Stop right there! We offer an incredibly affordable board exam review practice course at just $75 CDN.

Our course offers a thorough examination of key topics, ensuring you’re well-prepared for the Dental Hygiene Board Exam.

2. Engaging Interactive Sessions :

Benefit from study sessions that are not only informative but also interactive, making the learning process more effective.

3. Extensive Question Practice :

Get hands-on practice with questions that closely mirror those you’ll encounter on the board exam, giving you a competitive edge.

4. Invest in Your Future:

- Dental Hygiene

Cases for Online Study 2024

~ for Student Dental Hygienists

from MJ Fehrenbach, RDH, MS

- TOBACCO CESSATION

- ALL THINGS LA

- ORAL BIOLOGY POSTS

- ADHA Xerostomia with Hyposalivation Screening Tool Project

Basic Science and Oral Biology

Aleveolar Nerve

Anatomy Online

Anatomy MedlinePlus

Body National Georgraphic Vids

Cranial Nerves

DENTAL EDUCATION HUB

Facial Bone Anatomy

Gray's Anatomy Online

Gross Anatomy Practical Exam

Histology Lectures (OH MY!)

Lymph Nodes

Muscles in Action

Nerve Action

Neuroscience

Oral Biome (Nature)

Oral Examination

Oral Histology

Skull Practical Exam

Teach Me Anatomy: Head (see also Neck )

Visible Embryo

GO TO TOP OF PAGE

Classroom Activities, Community Dentistry & Public Health

Dental Care Page from Oral B and Crest

K-12 Oral Health Education Curriculum (PowerPoint Presentations)

Printables

Without Dental Care (PBS)

Instrumentation, Restorative,

Patient Care & Pain Management

A Lesson In Ease-Case Study

Describe and Doc Findings

Guideline on Behavior Guidance for the Pediatric Dental Patient

Matrix Placement

Oral Health Link (Mayo Clinic)

OPTIONS IN LOCAL ANESTHESIA

Remineralization for Children

General Cases in Dentistry

Case of the Month (not updated)

Dr. Galil's Gross Anatomy Related Cases

Forensic Dentistry

Free Library Case Study List

Google Dental Books

Google Scholar Dental Cases

Wisconsin Case Studies

YouTube Case Study Playlist

General Reference & Board Review

Canadian National Dental Hygiene Certification Board

Central Regional Dental Testing Service (CRDTS)

Clinical Practice Guidelines and Dental Evidence (ADA)

How to Read a Paper

Joint Commission on National Board Dental Hygiene Examination

Medical Encyclopedia

North East Regional Board (NERB)

Revised Standards ADHA

Western Regional Examining Board (WREB)

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics

Center for Science in the Public Interest

Eating Disorders (Nova)

Nutrition Center Links

Nutrition Links

Nutrition Science Trust

Overall Resource Page

Tracker MyPlate

Pathology & Periodontology

Abuse and Neglect

Ameloblastoma

CLASSIFICATIONS BY AAP

Blood Borne Pathogens

Child with Ectodermal Dysplasi a

Cranial Reconstruction

Color Atlas of Oral Pathology

Dental Hygiene Diagnosis

Dental Biofilm (Plaque) One and Two

Early Childhood Caries

First Aid Case Studies

Genetic Dental Abnormalities

HPV (Mayo Clinic)

Hyposalivation with Xerostomia Screening Tool (ADHA) and YouTube on How to Use It

Know Your Gums Lumps and Bumps

Medscape Cases / Medscape Dental (Registration)

Merck Manual for Dentistry

Microbiology Cases

Neurofibromatosis

Oral Pathology Lab

Oral Pathology Review YouTube

Osteoporosis and Bone Physiology

Oral Complications of Chemotherapy & Head/Neck Radiation

Oral Health Resources

Papillon-Lefevre Syndrome

Pathology Outlines

Screening Physical Exam (Go to Head, etc.)

Throat disorders

Tobacco Cessation Links

Pharmacology & Emergency Medicine

ASA Physical Status Classification System

Emergency Medicine Plus

Meth Mouth (ADA)

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

NLM - MedlinePlus

Premedication (ADA )

Top Drugs 2020

Cone Beam Discussion (FDA)

***Generate an Xray***

Guide to Dental Radiographs (ADA)

Know Your 'Rays YouTube

Label Tubehead / More Tubehead

MedPix (NIH)

Taking Digital Xrays YouTube

ADHA Research Page

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Refresher Clinical Research

SDHs' Case Studies

#1 YouTube Case from Georgian College

#2 YouTube Case from Georgian College

ETSU YouTube Case Study

Review With

Dental Anatomy Coloring Book, NEW

4th Edition from Elsevier, 2023

Studies also show that adult coloring is therapeutic, reducing stress similarly to meditation. The gentle and repetitive motion of your hand bringing color to paper helps quiet your mind, bringing your usual rapid-fire thoughts down to a much slower pace while leaving the fast-paced digital world behind.

Each page of the new edition contains a brief statement describing the body part featured and its orientation view, followed by a crisp easy-to-color illustration(s). Numbered leader lines clearly identify the structures to be colored and correspond to a numbered list appearing below the illustration.

This 4th edition fully delivers complete anatomic coverage of the head and neck. Beginning with an overview of body systems, and then moving on to specific regions of the head and neck as well as the oral cavity, the text follows the anatomic systems, including orofacial anatomy, dental anatomy, as well as the skeletal system, the muscular system, the vascular system, the nervous system, and much more! This book will help you to visually understand the various parts of the head and neck as well as the oral cavity and how they relate to each other. In addition, the final chapter on fasciae and spaces will give the reader a better overall regional feel for the anatomy of the head and neck.

Back-of-book multiple-choice test with answers and rationales enables you to gauge your mastery of dental anatomy. Access to online materials for Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck includes practice quizzes, Elsevier's online anatomy coloring book, and a skull bone identification interactive exercise.

AMAZON SALES

ARE HERE!!!

And see YouTube

YouTube ONLINE STUDY Videos

Cases for Online Study 2024 for SDHs

Dental Hygienists are a community of professionals devoted to the prevention of oral disease and the promotion and improvement of the public's health. Dental hygienists are preventive oral health professionals who provide educational, clinical, and therapeutic services to the public. As a healthcare professional, a dental hygienist is called on to know a wide range of information related to patient care. These links noted below only begin to show the range of information needed as a competent dental professional working within quality dental care.

Student dental hygieniss can browse through the sites of interest as listed below. Be sure to check out DH Links for even more in-depth information on research, patient care, and dental professional associations. Also check out 2024 Updated ASA PHYSICAL STATUS CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM (referenced in Dental Section that is continually undergoing peer review, including Author as Referred Dental Science Editor in Wikipedia !).

Unless otherwise specified, the production group of this site is not responsible for the content of any of the outside sites linked to this webpage. The listing of this site's name with any of these sites should not be misconstrued as an endorsement of the information in them. The addresses of these web sites are subjected to change and may need updating over time and may contain advertising which is not in control of the author of this website.

Updated 10/1/2024

Production by Fehrenbach and Associates

Evolving Online Resources

(No Alpha Listing)

The Happy Flosser RDH

NIH Imaging Case s

Lesion Cases from Dentistry IQ

Path Pack from Dentistry IQ

Clinical Tips from Perio-Implant Advisory

Inside Dental Hygiene

Compendium of CE in Dentistry

Breakthrough Clinical

RDH Magazine Search Page (registration)

Oral Path RDH Magazine (registration)

Oral Cancer Screening Guide

Oral Path: Soul of Dentistry

Dental Hygiene with Richardson & Norrell

JADA Quick Check Monthly

Mental Dental YouTube

Dimensions of DH Categories / DDH Cases

Today'sRDH / Today'sRDH Cases / FB

Wiley Online Check

U of Minnesota Cases

Hygiene Edge

Mosby's Dental Dictionary

Dental Care Case Studies (registration)

Wiley on Perio and Systemic

Music for Study More Music for Study

Geeky Medics Plus

Real Time TMJ MRI Scan MRI TMJ

JADA for Patients

Microbiology Knowledge

E-Books in Dental Hygiene

Dentistry IQ Pathology Packs

RDH Magazine Oral Pathology

Oral Pathology and Medicine (Wiley)

YT STUDY ONLINE TOPICS

YoutTube LEARNING STRATEGIES

Legal & Ethical Concerns

Dental Litigation News

Dental Ethics Course

Research Ethics

Oasis Dental Library

One of the largest libraries of free dental books, journals and videos

Case Studies in Dental Hygiene 3rd Edition

- Evelyn M. Thomson

Description:

Case Studies in Dental Hygiene, Third Edition, is designed to guide the development of criti-cal-thinking skills and the application of theory to care at all levels of dental hygiene education–from beginning to advanced students. This textbook is designed to be used throughout the dental hygiene curriculum. Because the questions and decisions regarding treatment of each case span the dental hygiene sciences and clinical practice protocols, this book will find a place in enhanc-ing every course required of dental hygiene students. Introducing this text at the beginning of the educational experience may help the student realize early on the link between theory and patient care. Students then progress through the program with a heightened awareness of evidence-based practice.

Students also perceive an increase in confidence regarding preparation for board examina-tions when they have been given the opportunity to practice case-based decision making. Case Studies in Dental Hygiene, Third Edition, is a viable study guide to help students prepare for suc-cess on national, regional, and state examinations with a patient care focus. This revised edition also is an excellent review text for the graduating dental hygiene student who is preparing to take the National Board Dental Hygiene Examination.

ISBN: 978-0-13-291308-9

Published Date : 2013

Page Count: 337 , File Size: 8 Mb

Related Subjects

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

43 Journal Archives Get Premium

PUBLISHED YEAR

2024 2023 2022 2021 2020 2019

Latest Videos

Membership Login

- Atlas / Anatomy

- Basic Sciences

- Biomechanics & Biomaterials

- Cleft Lip and Palat

- Dental Instrument

- Dental Journals

- Journals Archive

- Dental Materials

- Dental Photography

- Dental Technician

- Emergencies and Traumatology

- Endodontics

- Esthetics Dentistry

- Ethics and Practice Management

- Exam Preparation

- Filler & Botox

- Forensic Dentistry

- General Dentistry

- Hygienist & Assistant

- Implantology

- Infection Control

- Lasers in Dentistry

- Medical Problems

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Oral Health and Researchs

- Oral Medicine and Pathology

- Oral Microbiology

- Orthodontics

- Pediatric Dentistry

- Periodontology

- Pharmacology

- Prosthodontics – Fixed

- Prosthodontics – Removable

- Restorative & Operative

- Salivary Gland

- TMJ & Occlusion

Publisher & YEAR

Get Membership

Contact us Terms of Use

Privacy Policy

OASIS DENTAL LIBRARY (2018-2024)

Prepare for the NBDHE ®

Getting ready for success with the nbdhe.

The National Board Dental Hygiene Examination is overseen by the Joint Commission on National Dental Examinations (JCNDE), an independent agency of the American Dental Association, in collaboration with the Department of Testing Services (DTS). Examinations are administered by Pearson VUE at authorized test centers across the country.

Below you will find helpful tools and resources that can assist you in preparing for your upcoming examination. For complete details on the examination, refer to the NBDHE Candidate Guide. Frequently asked questions are covered on the NBDHE home page.

View the NBDHE Candidate Guide (PDF)

View the Common Acronyms and Abbreviations (PDF)

Visit the NBDHE home page

More test preparation resources

Learn about updates to the NBDHE and other National Board Examinations in this brief webinar.

View now

You may also want to explore the Pearson VUE examination software to help you navigate the exam format more easily. Use this link to download and install the tutorial so you can become familiar with how it works.

Navigate the tutorial

This test day checklist is a useful resource as you prepare for your examination. It was created as a summary of the most frequent issues that create complications for examinees on the day of testing. The Department of Testing Services (DTS) encourages you to read the entire guidebook for the test you are taking and to call the DTS at 800.232.1694 with any questions.

- I am bringing two original, current (not expired) forms of identification (ID) to the testing center: one government-issued ID, with my photograph and signature (e.g., driver’s license or passport) and one ID with my signature (e.g., Social Security card, credit card, debit card or library card).

- The name on my application matches my IDs exactly. I will contact the DTS if there is any possibility of a mismatch. Examples of names that do NOT match: Joseph Anthony Smith and J. Anthony Smith, Joseph A. Smith, or Joseph Anthony Smith-Johnson.

- I will leave all non-essential items at home.

- I will store all personal items – cell phone, food, candy, beverages, pens, pencils, lip balm, wallets, keys, jackets, etc. – in the assigned locker at the testing center. I understand that I may not access these items during testing or an unscheduled break.

- I will double-check my pockets to ensure they are empty before I sign in to test.

- I will follow the instructions of the test administrator and the rules of the testing center.

- I know what to do if I encounter a problem at the testing center. If I experience a problem with testing conditions, I must notify the test administrator immediately.

- I have made arrangements for my ride or to notify my family or friends after I complete my test and have signed out of the test center. I will not use my cell phone or other electronic devices in the test center or during my testing session.

Download the checklist

This list shows which reference texts have been used in creating NBDHE questions. This may provide a helpful overview for candidates as well as others interested in NBDHE exam content.

View reference texts

- Medical Books

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Case Studies in Dental Hygiene 1st Edition

- ISBN-10 013018571X

- ISBN-13 978-0130185716

- Edition 1st

- Publisher Pearson

- Publication date January 1, 2003

- Language English

- Dimensions 8 x 0.25 x 10.5 inches

- Print length 200 pages

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

From the back cover.

Designed to guide the development of critical thinking skills at all levels of dental hygiene education, Case Studies in Dental Hygiene provides diverse scenarios that span the curriculum, applying theory to care. Patterned after the Dental Hygiene National Board Examination, it provides "snap-shots" of pediatric, periodontally involved, geriatric, special needs, and medical compromised cases.

- Unique! The only text solely devoted to case situations on the market.

- Concise, specifically defined case studies.

- A team of authors provide expertise for a variety of case study development.

- Case-based questions from basic to advanced encourage critical thinking.

- Encourages application of dental hygiene theory to client care.

- Incorporation of the Human Needs Conceptual Model to Dental Hygiene Practice as a reflective activity for each case.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Educators need case-based learning tools that may be integrated throughout the dental hygiene curriculum. Within the educational environment exists the goal to assist students in linking basic knowledge to dental hygiene care that is evidence-based and client-centered. With the constantly evolving knowledge base and changing technologies, dental hygiene faculty are challenged to incorporate educational technologies that exceed knowledge acquisition and focus on critical decision making. Case Studies in Dental Hygiene is a viable educational tool to help students learn to apply basic knowledge to client care and to prepare them for success on national, regional and state examinations which have a client care focus.

Case Studies in Dental Hygiene is designed to guide the development of critical thinking skills and the application of theory to care at all levels of dental hygiene educationfrom beginning to advanced students. Additionally, during the course of their formal education, dental hygiene students can be exposed only to a small spectrum of cases they might encounter in the real world. The diversity of the cases in this text provides an avenue for simulating experiences students might not encounter in their education. This text is designed to cover a broad array of topics, to be adaptable for use in a variety of courses, and to be used across student knowledge and skill levels.

This text is designed to be utilized throughout the dental hygiene curriculum. Because the questions and decisions regarding treatment of each case span the dental hygiene sciences and clinical practice protocols, this text will find a place in enhancing each and every course required of dental hygiene students. It is expected that Case Studies in Dental Hygiene would be introduced at the beginning of the student's educational experience and be utilized throughout the program of study. As the students' knowledge base develops, the answers to the more complex questions would become apparent. If the text were introduced early in the program, students would realize the link between theory and client care immediately. Once exposed to the cases, students progress through the program with a heightened awareness, a "need to know," a's new material is introduced which can be applied to answer case-based questions. Additionally, Case Studies in Dental Hygiene makes an excellent review text for graduating dental hygiene students preparing to take the Dental Hygiene National Board Examination.

Case Studies in Dental Hygiene presents oral health case situations representing a variety of clients that would typically be encountered in clinical settings. There are 10 cases, 2 each representing the following client types: pediatric, adult periodontally involved, geriatric, special needs, and medically compromised. Each case contains a medical history, dental history, vital signs (including blood pressure, pulse, and respiratory rates), radiographs, dental and periodontal charting, intraoral photographs, and photographs of study models, where applicable. Additionally, learning objectives and multiple-choice questions are identified for each case. Questions are subdivided into the following categories: assessing client characteristics, obtaining and interpreting dental radiographs, planning and managing dental hygiene care; performing periodontal procedures, using preventive agents, and providing supportive treatment services. Each question is clearly identified as "basic" or "complex," further guiding educators and students to use each case to maximum benefit. Students will be challenged to seek answers and select appropriate care for the clients in each case scenario. Correct answers and rationales for incorrect responses are provided for all questions. Providing descriptive rationales for incorrect answers further enhances learning. Reflective activities and a section incorporating the Human Needs Conceptual Model to Dental Hygiene Practice guide the instructor in developing additional learning activities for the student. The rapidly increasing, constantly changing knowledge base and technologies associated with clinical practice mandate that dental hygiene professionals be prepared to provide oral care that meets the needs of the whole client. The Human Needs Conceptual Model to Dental Hygiene Practice has been established as a means of linking oral care with the general health of an individual. Although many dental hygiene programs have incorporated the Human Needs Conceptual Model into their curriculum, others are in need of educational tools which assist with this incorporation. Case Studies in Dental Hygiene, provides educators with a bank of ready-made cases with which to guide students to integrate client needs or deficits with dental hygiene care planning. Each case lists suggestions for creating decision-making opportunities for the students, regarding client care and treatment recommendations that promote oral health and prevent oral diseases.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

Each chapter contains one case scenario, making it a stand-alone module that may be introduced in any order and at any time during the curriculum. While there are a variety of ways in which to utilize the case studies, educators may benefit from the suggestions listed here. Cases C and D, The Periodontally Involved Adult Client, could be used as required reading for the preclinical student to introduce the dental hygiene process of care. Because each case contains questions that are knowledge-based as well as complex decision-making questions, the beginning student may be directed to answer the "basic" questions. During theory class, a discussion of these answers may help to increase the incidence of critical thinking skills and can reinforce and facilitate learning in a dynamic, stimulating manner motivating the student to more fully participate in the learning process. Because the questions for each case are subdivided into client assessment, radiographic services, planning and management of care, periodontal procedures, and supplemental services, instructors of basic dental hygiene sciences may easily identify those questions which supplement learning in their disciplines. The radiology instructor may utilize the "basic" questions of all the cases, directing the beginning student to those questions under the subdivision "obtaining and interpreting dental radiographs" while the pharmacology instructor may use Cases I and J, The Medically Compromised Client, to provide a realistic setting to assist students in linking drug interactions which may contraindicate dental hygiene care with planning and managing treatment. Cases A and B, The Pediatric Client, may provide an opportunity for the student to identify eruption patterns, learned in head and neck anatomy or tooth and root morphology courses. Applying theory and knowledge gained in the basic dental hygiene sciences to solve problems encountered through case-based questioning allows the student to become actively involved in the learning process. After all, the challenge of case-based instruction is to maximize students' synthesis of theoretical material and provide a link between science, theory, and clinical practice. Case Studies in Dental Hygiene may compliment and enhance material learned in other texts. For example, students learning instrument design from a theory book may link application of this knowledge when challenged by case photographs and charts to choose an appropriate instrument for scaling a specific area. Radiographic problem solving skills are further enhanced by examination of the case radiographs when the student is challenged not only to identify technique and processing errors, but also to recommend corrective action.

In addition to basic questions, each case contains complex questions that challenge advanced students to develop improved clinical reasoning that will assist them in real-world clinical practice. As students progress through the curriculum, the same cases may be revisited through the use of complex questions. Students usually respond favorably to the opportunity to apply knowledge gained in the classroom to fictional cases. The ability to plan treatment and simulate implementation through case study provides the student with a stress-free environment in which to make decisions. Students report increased confidence when faced with treatment planning and implementation decisions regarding clients in the clinical setting. Students also perceive an increase in confidence regarding preparation for national and regional board examinations when they have been given the opportunity to practice decision making.

In case-based teaching, a frequent faculty complaint is that students and faculty have difficulty integrating information from various courses within the discipline to the case-based format. Healthcare educators are fully cognizant that effective clinical judgment only comes from experience, since it is the use of real life situations which encourages student analysis and decision making in areas relevant to professional practice. However, most faculty do not consider themselves experts on all dimensions of a problem, and as a result may be limited in their use of case studies. To overcome the limited use of case studies to specific disciplines, Case Studies in Dental Hygiene was written by several authors, each an expert in a specific aspect of dental hygiene care. This multi-author approach to the development of the cases contained in this book, is intended to provide other dental hygiene educators with a ready-made bank of cases upon which to build meaningful learning activities' for the student. Additionally, the authors hope that the format and content of Case Studies in Dental Hygiene will provide students with an opportunity to practice critical decision-making skills and reinforce and facilitate learning in a dynamic, stimulating manner, thereby motivating students to more fully participate in the learning process. This book was designed specifically to encourage dental hygiene students to base client care decisions on knowledge gained in theory, thus fostering in students an appreciation of the link between theory and clinical practice.

Product details

- Publisher : Pearson; 1st edition (January 1, 2003)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 200 pages

- ISBN-10 : 013018571X

- ISBN-13 : 978-0130185716

- Item Weight : 13.6 ounces

- Dimensions : 8 x 0.25 x 10.5 inches

- #75 in Dental Hygiene (Books)

- #257 in Preventive Dentistry

About the author

Evelyn m. thomson.

Evelyn Thomson, BSDH, MS, served 20 years as educator at Old Dominion University's Gene W. Hirschfeld School of Dental Hygiene in Norfolk, Virginia, receiving awards for Faculty Excellence; Continuing Education Teaching & Leadership; Outstanding Author; and Distinguished Alumni. In addition to teaching in the undergraduate dental hygiene program and mentoring graduate students in the master’s degree program, Thomson developed and taught numerous continuing professional education courses; served as a consultant to the Virginia Board of Dentistry; and conducted seminars for the American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Thomson’s expertise has been validated by membership in the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology, and with an appointment on the National Board Dental Hygiene II Test Construction Committee by the Joint Commission on National Dental Examinations. Thomson is author and co-author of three textbooks: Exercises in Oral Radiographic Techniques: A Laboratory Manual; Case Studies in Dental Hygiene; and Essentials of Dental Radiography for Dental Assistants and Hygienists and has published numerous manuscripts in peer-reviewed dental hygiene journals. Evie lives at the Virginia Beach oceanfront with her husband Hu Odom.

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 34% 31% 0% 0% 36% 34%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 34% 31% 0% 0% 36% 31%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 34% 31% 0% 0% 36% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 34% 31% 0% 0% 36% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 34% 31% 0% 0% 36% 36%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Dental hygiene diagnosis: A qualitative descriptive study of dental hygienists

Darlene j swigart.

* Assistant professor, Department of Dental Hygiene, Oregon Institute of Technology, Klamath Falls, OR, USA

JoAnn R Gurenlian

§ Professor and graduate program director, Department of Dental Hygiene, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID, USA

Ellen J Rogo

‡ Professor, Department of Dental Hygiene, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID, USA

The purpose of this qualitative descriptive study was to explore dental hygiene diagnosis (DHDx) to gain an understanding of how dental hygienists experience this phenomenon while providing dental hygiene care.

A qualitative descriptive research design was employed using purposive sampling. Data were collected from semi-structured interviews with 10 dental hygienists actively practising in California, Oregon or Colorado. The interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed verbatim, and verified for accuracy. Data analysis included open coding and axial coding to determine larger, related segments of data called categories providing an overall descriptive summary of DHDx. Two independent peer examinations and member checks established validity of the data analysis.

Four categories emerged from the study: expertise and confidence; client communication; dental hygiene care plan; and dentists’ trust. Participants revealed that expertise and confidence in performing the DHDx was gained through clinical practice. During client care, discussing the DHDx with clients helped to make them aware of their health condition. The development of the dental hygiene care plan was based on the results of the assessment data and the DHDx. Participants stated that their employer/dentist trusted them to diagnose.

Conclusions

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted to summarize dental hygienists’ experiences with DHDx in 3 US states; 4 categories emerged. The DHDx informs the client, increases understanding, and engages the client in the decision-making process. Further study is warranted to identify a more contemporary definition of DHDx and to compare how DHDx is utilized by dental hygienists in other countries.

Le but de cette étude descriptive et qualitative était d’explorer le diagnostic d’hygiène dentaire (DxHD) pour bien comprendre comment les hygiénistes dentaires vivent ce phénomène, tout en fournissant des soins d’hygiène dentaire.

Méthodologie

Une méthodologie de recherche descriptive et qualitative a été employée au moyen d’un échantillonnage choisi à dessein. Les données ont été recueillies à partir d’entrevues semi-structurées avec 10 hygiénistes dentaires qui exercent activement en Californie, en Oregon ou au Colorado. Un enregistrement sonore des entrevues a été effectué et les entretiens ont été transcrits textuellement et leur exactitude a été vérifiée. L’analyse des données comprenait un codage ouvert et un codage axial pour déterminer les segments de données plus volumineux et connexes appelés catégories, produisant un résumé descriptif global du DxHD. Deux examens indépendants effectués par les pairs et des vérifications effectuées par les membres ont permis d’établir la validité de l’analyse des données.

Résultats

Quatre catégories sont ressorties de l’étude : expertise et confiance, communication avec le client, plan de soins d’hygiène dentaire, et confiance des dentistes. Les participants ont révélé que l’expertise et la confiance dans la performance du DxHD ont été acquises par l’exercice clinique. Au cours des soins du client, le fait de discuter du DxHD avec les clients a aidé à leur faire prendre conscience de leur état de santé. L’élaboration du plan de soins d’hygiène dentaire a été fondée sur les résultats des données d’évaluation et sur le DxHD. Les participants ont déclaré que leur employeur ou dentiste leur faisait confiance pour poser un diagnostic.

Une étude descriptive et qualitative a été menée pour résumer les expériences de DxHD des hygiénistes dentaires dans 3 états américains et 4 catégories en sont ressorties. Le DxHD guide le client, augmente la compréhension, et incite le client à participer au processus de prise de décisions. Une étude plus approfondie permettrait de cibler une définition plus contemporaine du DxHD et pour comparer comment le DxHD est utilisé parmi les hygiénistes dentaires dans d’autres pays.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THIS RESEARCH

- Dental hygiene diagnosis is an essential step in the dental hygiene process of care and guides the creation of dental hygiene care plans.

- Graduates of entry-level programs develop expertise and confidence in implementing the dental hygiene diagnosis through clinical care experiences.

- Dentists trust dental hygienists to perform a dental hygiene diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Diagnosis refers to the identification of a disease based on the presentation of signs and symptoms. 1 Health care professionals in all fields use diagnosis as a means to identify and discuss diseases with patients and formulate a plan for treatment. Dental hygienists incorporate diagnosis, specifically called dental hygiene diagnosis (DHDx), into clinical practice to assist in the prevention and treatment of oral diseases. 2

Historically, various models of DHDx began to appear in dental hygiene textbooks in the early 1990s. Gurenlian 3 introduced a model for dental hygiene diagnostic decision making in 1993, which was followed in 1995 by the first method for formulating a DHDx by Mueller-Joseph and Peterson. 4 At that same time, Darby and Walsh presented a DHDx model based on the Human Needs Conceptual Model. 5 This version of the DHDx has appeared in subsequent editions of their textbook. Swigart and Gurenlian proposed a practical approach for integrating the DHDx for clinical care. 6 , 7

American Dental Hygienists’ Association: Standard 2

|

|

| The ADHA defines dental hygiene diagnosis as the identification of an individual's health behaviors, attitudes, and oral health care needs for which a dental hygienist is educationally qualified and licensed to provide. The dental hygiene diagnosis requires evidence-based critical analysis and interpretation of assessments in order to reach conclusions about the patient's dental hygiene treatment needs. The dental hygiene diagnosis provides the basis for the dental hygiene care plan. Multiple dental hygiene diagnoses may be made for each patient or client. Only after recognizing the dental hygiene diagnosis can the dental hygienist formulate a care plan that focuses on dental hygiene education, patient self-care practices, prevention strategies, and treatment and evaluation protocols to focus on patient or community oral health needs. |

| I. Analyze and interpret all assessment data. |

| II. Formulate the dental hygiene diagnosis or diagnoses. |

| III. Communicate the dental hygiene diagnosis with patients or clients. |

| IV. Determine patient needs that can be improved through the delivery of dental hygiene care. |

| V. Identify referrals needed within dentistry and other health care disciplines based on dental hygiene diagnoses. |

Source: American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for clinical dental hygiene practice. Rev. ed. Chicago (IL): ADHA; 2016 [cited 2018 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf

Both the Canadian Dental Hygienists Association (CDHA) and the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) have included DHDx in their respective standards of practice for dental hygienists. 8 , 9 The CDHA reference to DHDx is found in Standard 2: “Dental Hygiene Process: Assessment.” Item 2.5 states, “Analyze all information to formulate a decision or dental hygiene diagnosis” 8 p.9 . The ADHA standard for DHDx appears in Table 1. 9 Table 2 displays the similarities in DHDx definitions between these 2 associations; both require the dental hygienist to think critically about assessment data and formulate conclusions to address clients’ needs. 10 , 11 A DHDx is paramount to providing individualized, appropriate client education, dental hygiene care planning, disease prevention, and therapeutic and re-evaluation procedures. 6

In health care globally, there has been a focus on person-centred care, which is an individualized, holistic approach to care where the decision making is shared by the clinician and the client, and at times, includes the client’s family or caregiver. 12 , 13 Instead of viewing the client as a collection of symptoms, person-centred care fosters communication to take into consideration the client’s values and goals. 12 , 13 Dental hygienists have an ethical responsibility to provide opportunities for clients to make informed decisions about their treatment. 14 Communicating the DHDx to the client is part of that responsibility. 9

In 2018, Gurenlian, Sanderson, Garland, and Swigart surveyed dental hygiene clinic coordinators in the United States to ascertain opinions regarding the importance of a DHDx and to understand how the DHDx is incorporated into educational programs. 15 Of 188 survey respondents, 98% confirmed that the DHDx is a necessary component of dental hygiene care and determines dental hygiene interventions. 15 Program administrators consider a DHDx a valuable and necessary element of client care.

Health care professionals in other disciplines recognize the importance of the DHDx to client overall health and collaborative care. In 2012, Jones and Boyd investigated whether a dental hygienist would be a valuable member of an interdisciplinary pediatric feeding team by assessing the importance of the dental hygiene process of care, advocacy, and health education and promotion. 16 Team members surveyed included registered dietitians, speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists, registered nurses, and advanced registered nurse practitioners. The 4 areas pertaining to DHDx in the study were 1) identifying existing or potential oral problems associated with teeth, 2) periodontal disease, 3) oral lesions, and 4) sensor,y disorders. All team members rated the role of the dental hygienist on the pediatric feeding team as “very important/most relevant.” 16

Canadian and American DHDx definitions

|

|

|

| Canada (Canadian Dental Hygienists Association) | "A dental hygiene diagnosis involves the use of critical thinking skills to reach conclusions about clients" dental hygiene needs based on all available assessment data." |

| United States (American Dental Hygienists' Association) | "The identification of an individual's health behaviors, attitudes, and oral health care needs for which a dental hygienist is educationally qualified and licensed to provide. The dental hygiene diagnosis requires evidence-based critical analysis and interpretation of assessments in order to reach conclusions about the patient's dental hygiene treatment needs. The dental hygiene diagnosis provides the basis for the dental hygiene care plan." |

Even though dental hygienists are ethically responsible for and qualified to recognize oral diseases and use the DHDx to formulate an appropriate individualized dental hygiene care plan, 9 , 11 no research has been conducted to understand the process of the DHDx as performed by dental hygienists in practice. The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the DHDx in order to gain an in-depth understanding of how dental hygienists currently licensed and practising in the US experience this phenomenon. The following research questions guided the conduct of this study: 1) How do dental hygienists learn to value the DHDx? 2) How do dental hygienists perform the DHDx in clinical practice? 3) Why do dental hygienists perform the DHDx in clinical practice? 4) How do dental hygienists create a dental hygiene care plan based on the DHDx?

Study design and participant recruitment

A qualitative descriptive approach was adopted to facilitate the in-depth exploration of dental hygienists’ experiences with DHDx in clinical practice. This research design is appropriate to explore phenomena where little theoretical or practical knowledge exists. 17 Based on the limited knowledge of the implementation of DHDx during clinical care, this qualitative approach was used to gain an understanding of this aspect of the dental hygiene process of care and provides a foundation on which other investigations are conducted. The study design underwent full IRB review from the University’s Human Subjects Committee and received approval (IRB-FY2017-252).

Purposive sampling is commonly implemented as the sampling plan for a qualitative descriptive study. 17 The recruitment of individuals who have experiences with the phenomenon (DHDx) and are able to inform data collection are important considerations of purposive sampling. 18 Participants were initially recruited through personal networking by the researchers who emailed an IRB-approved announcement to colleagues in California, Oregon, and Colorado. These states were selected because the dental hygiene scope of practice includes direct access to dental hygiene care. Additionally, in Oregon and Colorado, DHDx is specifically identified in the practice act as a procedure for dental hygienists. 19 Furthermore, the snowball sampling method 18 was implemented to gain referrals of other dental hygiene colleagues who could be recruited for the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were dental hygienists who were actively practising at least 16 hours a week and had a minimum of 1 year of experience. Exclusion criteria eliminated dental hygienists who were currently or previously employed as educators in dental hygiene programs or worked less than 16 hours per week. When potential participants were identified, a screening questionnaire was completed to establish who met the inclusion criteria and determine procedures they completed during client care.

Participant selection

The 10 dental hygienists selected were those who collected assessment data, evaluated risk factors for oral disease, and determined dental hygiene treatment based on the assessment data and client risk factors. Additionally, demographic questions were asked on the questionnaire to establish maximum variation in the sample.

Maximum variation was implemented to gain diversity within the sample 18 based on demographic (gender, age, years in practice) and type of practice (general private practice, direct access practice, corporate practice) variables. Using maximum variation in a qualitative descriptive inquiry provides researchers with the opportunity to explore similar and unique experiences across varied contexts. 17 During the interview process, saturation determined the final sample size. Saturation involves increasing the sample size until no new information surfaces during the interviews. 18

Data collection and data analysis

The 4 research questions directed the development of the interview guide as depicted in Table 3. The guide included major questions and subordinate questions to elicit additional detail in responses. The content validity of the questions was established by using the Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice of the ADHA and previous DHDx research. 9 , 15 Using the guide ensured that all topics were covered in a valid and reliable manner during each interview. 18 Two members of the research team conducted a pilot interview to determine whether the major and subordinate questions would collect data to answer the research questions as a validation process. The interview guide was sent to participants at least 1 week prior to the interview to help them formulate responses.

Written informed consent was obtained prior to interviews being conducted by the principal investigator through an audiorecorded phone interview. Interviews were conducted with semi-structured methodology allowing for additional follow-up questions to collect more in-depth data or new data. The conversation was audiorecorded using the Olympus WS-300M 256 MB Digital Voice Recorder and Music Player. All audiorecordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist. Participant pseudonyms were used during the interview and on the interview transcript to protect confidentiality and ensure anonymity. The principal investigator listened to the audiorecorded interviews to verify the accuracy of the transcriptions.

Data regarding the DHDx generated from the interviews were analysed simultaneously with data collection; both processes reciprocally influenced each other. 17 The data analysis method of choice for qualitative descriptive studies is qualitative content analysis. 17 The result of this analysis is a descriptive summary of the data, which is less interpretive than data analysis other qualitative approaches use. 17

Interview guide

|

|

|

1. In what type of practice are you currently employed? 2. What other types of practices have you had experience? |

| ? 3. How would you define a DHDx? 4. Tell me about your typical day at work with your patient? 5. What assessment data do you collect on your patients? 6. Does the dentist in your practice do a clinical exam at every dental hygiene appointment? If not, how often? 7. In your practice, are you expected to report suspicious oral lesions, caries lesions, and/or periodontal disease to the dentist? If yes, how do you report or discuss your findings with the dentist? 8. How do you perform a DHDx? Can you give an example? |

|

9. How were you taught DHDx in the dental hygiene program where you attended? 10. What conditions were you taught to diagnosis? 11. How do you feel performing the DHDx benefits a patient? |

|

12. In your practice, do you create the dental hygiene care plan for the treatment you would perform for the patient? a. What types of procedures, education, or referrals might be included? 13. How is the dental hygiene care plan discussed with the patient? a. Can you give an example of this discussion? 14. Is the DHDx discussed with the patient? a. Can you give an example of how the DHDx is discussed? 15. Do you document the DHDx in the patient record? If yes, how do you document the DHDx in the patient record? If no, what are your reasons for not documenting the DHDx? 16. Do you feel the DHDx improves patient outcomes? If yes, can you explain how the DHDx improves patient outcomes? If no, why do you feel the DHDx does not improve patient outcomes? |

|

17. How do you feel you learned to value a DHDx? 18. When you graduated, did you value DHDx as a part of care? 19. As you have been practicing, how do you value your ability to perform a DHDx? 20. What barriers or hindrances do you encounter with the DHDx? |

|

21. Do you have any other thoughts or comments about your experience with the DHDx? 22. Is there anything else you would like to tell me about DHDx? |

Transcripts were read numerous times by the investigators to become familiar with the data and to develop a contextual understanding of factors related to perceptions of DHDx. Open coding deconstructed the data into manageable one-word or short phrases describing the participants’ experiences relevant to answering the research questions. 18 During the next phase—axial coding—open codes were combined to form larger segments of data indicated as categories. Each research team member coded the same interview, compared and discussed findings until consensus was reached. Common categories were then analysed and organized to summarize the data, following Merriam and Tisdell’s 18 recommendation that categories should be responsive to the purpose of the research, exhaustive, mutually exclusive, sensitizing, and conceptually congruent.

Establishing rigour

Two research team members conducted an independent peer examination of the data analysis to ensure validity. Another procedure used for validity was respondent validation. 18 Member checks by participants evaluated the preliminary findings and provided feedback on the accuracy of the researchers’ interpretation of the data. All 10 participants reported they agreed with the analysis.

Study participants

Demographic data for the 10 participants were analysed using descriptive statistics and are presented in Table 4. Six dental hygienists from California, 2 from Oregon, and 2 from Colorado participated in the study. The majority of participants were between the ages of 34 and 44 years, female, and had over 13 years of experience. Eight participants worked in private practice under the supervision of a dentist; 2 worked in independent practices without the supervision of a dentist. These independent practitioners provided care in long-term care facilities, at a senior citizen centre, and with a mobile dental clinic.

Four categories emerged from the study: expertise and confidence; client communication; dental hygiene care plan; and dentists' trust.

Expertise, and confidence

Participants revealed that, while foundational learning of the DHDx began in dental hygiene education, expertise and confidence in performing the DHDx was gained through clinical practice. Most participants reported learning to perform the DHDx in their dental hygiene education program. Hannah described being taught in a clinical setting, with a client present, and under the guidance of the dental hygiene faculty. She learned to diagnose periodontal case types and elaborated on her oral pathology education, stating:

We were always encouraged to look out for unusual findings in the mouth. If we did see anything, we were to describe it, to actually measure it, and write it down.

Mike stated, “we’re really good at diagnosing periodontal disease,” and detailed also being taught to diagnose bruxism, wear patterns, abfractions, dental caries risk, and dental caries on radiographs. Mia explained how she was educated to assess for dental caries and determine the dental caries classification. Jane confirmed learning to diagnose not only dental caries, but also radiolucencies around tooth apices. Nikki discussed that her postgraduate advanced practitioner training developed her use of the DHDx because she would be working in independent practice without a dentist present.

I really probably learned [DHDx] through the training I received at my postgraduate AP [advanced practitioner] class. They really stressed that on us, more so than my bachelor degree dental hygiene class twenty-four years ago. A lot has changed and because we’re seeing these patients independently, you get better at evaluating things and being confident in your evaluation and referrals.

Other ways participants learned DHDx were through reading articles in professional journals and attending continuing education courses.

In contrast, Michele and Leah specifically acknowledged they did not learn to determine the DHDx during their dental hygiene education. Michele was educated to recognize different levels of periodontal disease and discuss the findings with the supervising dentist who would provide the diagnosis and referrals. Furthermore, Michele expressed, “I like the fact that I don’t have the legal responsibility of diagnosis because that is left to the doctor’s hands.” Leah stated, “We weren’t specifically taught a DHDx and how to write that up, with that title.” She explained how she was taught to do an oral assessment, oral cancer screening, and to recognize abnormal oral conditions to be diagnosed by the dentist. Even without specific terminology for the DHDx, Leah was expected to identify dental caries, both clinically and radiographically, in addition to decalcification and root caries.

Developing confidence in and appreciating the value of conducting a DHDx occurred through clinical experiences in practice. All participants confirmed that their increased confidence in diagnosing improved communication skills regarding the DHDx and strengthened the value they place on DHDx. Jane specifically credited the dentist by whom she is employed for increasing her knowledge of diagnosing and motivating her to perform the DHDx.

I had a lot of good foundational knowledge and then was able to apply it [DHDx] to all the many patients in clinical practice. It just expands upon what you’ve already learned. I’ve also learned a lot from the dentist I work for. I feel like he’s taught me a lot. I do have a lot more confidence in saying yes, this is what I think this is and explaining that to the patient. And I think that would come with time.

Multiple participants confirmed that the more years they were in practice and performing the DHDx, the more confident they became in their diagnosis. As Elizabeth explained:

When I was first out of school, if I got hesitation [about recommendations] from a patient, it would make me feel uncomfortable and make me second guess whether my diagnosis was correct or not. And now that I’ve been practicing so long, I know what my diagnosis is and it’s MY job to help the patient understand why I’m making that diagnosis. I’m not going to be talked out of what I’m recommending for a patient.

Additional supporting quotations illustrating how DHDx expertise and confidence develop through clinical experiences are presented in Table 5.

Participant demographic data

|

|

|

| California | 6 (60%) |

| Oregon | 2 (20%) |

| Colorado | 2 (20%) |

|

|

|

| 28 to 33 | 3 (30%) |

| 34 to 44 | 4 (40%) |

| 45 to 53 | 3 (30%) |

|

|

|

| Male | 2 (20%) |

| Female | 8 (80%) |

|

|

|

| 1 to 6 | 2 (20%) |

| 7 to 13 | 2 (20%) |

| Over 13 | 6 (60%) |

|

|

|

| Associate | 3 (30%) |

| Bachelor | 6 (60%) |

| Master | 0 (0%) |

| Doctorate | 1 (10%) |

|

|

|

| General private practice | 6 (60%) |

| Independent/Direct access practice | 2 (20%) |

| Corporate practice | 1 (10%) |

| Certified advanced practitioner working in private practice | 1 (10%) |

Supporting quotations for category 1

|

|

| I think with anything, it [DHDx) gets better with time. The more you do it, the better you become with it and the more varied the mouths are that you've been exposed to, you learn something new all the time. So I think I value it more because my-the education in practice-has always been more valuable than the education at school. (Michele) |

| [DHDx has] definitely gotten better over time. I wouldn't say that in the first year, second year, I was that confident. But I feel very confident about it now. Without having a dentist present I could still make that diagnosis. (Mia) |

| Definitely, I feel like I'm more competent now than seventeen years ago and more confident in making the diagnosis and not second-guessing myself. (Mary) |

| I am much more confident in my diagnoses now. I know what I am saying is truthful and I can back it with information and my own experience. (Hannah) |

Patient communication

The DHDx helps to make clients aware of their health condition and provides the dental hygienist with an opportunity to explain the DHDx to the client. Albert, Hannah, and Mary each described how they present the DHDx to their clients.

An example of how I take a DHDx. I had a patient in her 60s. She had several missing teeth, crowns, and very large fillings. She had failing restored margins, pockets, clinical attachment loss, radiographic evidence of bone loss, heavy plaque, and debris on the gingival surface of those teeth. She stated disappointment with failing treatment that she attributed to herbs by her previous dentist. And she said (quote), “Dr. Oz said I don’t need fluoride.” She was on several medications for hypertension and diabetes. Her DHDx was generalized mild to moderate chronic periodontitis, high caries risk, restorative needs requiring a dentist’s attention, anxiety, high risk of perceived or actual failure of treatment, high risk of oral systemic complications, pockets of deficits related to effects of treatment, fluoride and personal health habits, affective deficits related to interaction with health professionals and sources of information, and psychomotor deficits related to home care habits. (Albert)

To the patient I described earlier, I explained that because she had problems with her dental treatment in the past, I would like to have her release prior records to us before I begin providing treatment. To the event, to prevent the same pitfalls from happening again. I also asked her to have Dr. Oz send his diagnostic and treatment notes so I could understand why he did not think she needed fluoride. I explained the effects of fluoride on dental health, the characteristics of her periodontitis and treatments. I also explained the treatment I recommended for her would help the longevity of her restoration and interact positively with her systemic health. (Albert)

I need to feel I’m doing the best possible thing for my patient. There needs to be honesty between the hygienist and the patient which will develop trust. The DHDx is a true representation to the best of my knowledge of the patient’s condition which is the baseline which I work from to perform the best possible care, and I value that. Because periodontal disease can have no symptoms, many people don’t realize they have it. Explaining to the patient the diagnosis is educational and they should know if there is a problem so it can be addressed as soon as possible. (Hannah)

I would sit the patient up and we usually take photographs and radiographs and show the patient in their own mouth what’s going on. Explain to them how their systemic condition relates to their oral health. Explain to them what we’re finding as far as pocketing and bleeding and calculus and let them know what their options are for treatment. (Mary)

In some cases, participants divulged that clients are not always informed of their oral health status. Michele, Mike, Elizabeth, and Mia reported occasions when clients had been shocked to learn their DHDx because they had never previously been told of their disease state.

I’ve had patients that are shocked. They have been going to their office and seen routinely for care, and all of a sudden, they come in, they see me for the first time, and when I tell them what the diagnosis is and the treatment plan, they are shocked. They’ll ask questions why or how did this happen? Or what do I do to prevent it? (Mia)

Participants reported the significance of educating the client while informing them of the DHDx. When clients are made aware of their disease status through the DHDx, they are more likely to accept dental hygiene ,treatment. Mike explained, “By telling the patient and educating them, you’ll get a lot better results. They’re a lot more aware and so they’ll take more action.”

Leah discussed how dental hygienists back up the DHDx with “a lot of information for the patient to make sure the patient understands.” She further detailed her direct access practice at a senior citizen centre, stating that some clients she treated would not seek oral care at a dental office. The only care some clients were willing to have involved dental hygiene procedures completed at the senior citizen centre. Leah stressed that referrals were made to dental offices, but clients did not always follow through with them. In one case, she informed a client of an abscess. By helping the client understand the diagnosis, she was able to convince the client to seek treatment. Furthermore, Leah called a clinic to schedule an appointment, thus fulfilling the role of a case manager of oral health care to ensure the spread of infection did not affect systemic health. Additional supporting quotations for this category appear in Table 6.

Dental hygiene care plans

A dental hygiene care plan consists of formulating conclusions about dental hygiene treatment based on the results of the assessment data and the DHDx. Participants described how they relate the dental hygiene care plan to the DHDx.

I begin explaining the assessment data, the implication of that data, and the diagnoses that emanate from that data. Then I explain the diagnoses and how the recommended treatment will address the diagnoses. (Albert)

After the initial therapy, we’ll be seeing the patient for a six-week evaluation appointment. That allows us to see what healing has occurred. It is a long-term commitment on their part because it requires them to come in every three to four months for at least the first year. If we see any inflammation, bleeding, pocketing remaining after one year, then we will keep them on a three- to four-month periodontal maintenance program. I explain the difference between periodontal maintenance and a prophylaxis. We typically go over recommendations for flossing. If they don’t like regular floss, we recommend soft picks or water flosser. We typically recommend using an electric toothbrush and tongue brushing. (Elizabeth)

Supporting quotations for category 2

|

|

| Oftentimes, their response is that they had never been explained exactly what was going on in their mouth before. (Michele) |

| If anyone's informed and knows what going on, the majority of people in this world will take actions to get better. When you go to your doctor, he tells you that you have high blood pressure. He explains the plan and meds, and how often to follow-up with him. It's the same thing with dental hygiene. (Mike) |

| I think that they have more trust and I see more respect for the dental profession because it not only improves their oral health, but the systemic link. Patients feel like we're looking out for all of them just not their mouths. So, I think it's a good thing. It builds trust. (Mia) |

| I think it would help them have a greater understanding of, "I do have periodontal disease." Maybe they didn't know that before. Or, "Oh, I didn't know I had a cavity there. It didn't hurt." Or, "Oh, yeah, I never noticed that lesion in my mouth." By me pointing those things out to them, it gives them information that's beneficial to them. So it is addressed and treated properly and doesn't go unnoticed. (Jane) |

| You don't want them to lose their teeth. If they have an aggressive form of periodontal disease, we need to help the patient understand this is serious. You're going to lose your teeth. I feel like that would be very beneficial to them. This is what's going on in my mouth, this is a serious thing, and I need to address it. If it was a cavity, we don't want it progressing from a small cavity to potentially a root canal. With a pathology, that could become oral cancer. There can be long-lasting effects. I think it's extremely beneficial that we, as hygienists, point this out to our patients. Now in these conversations. (Jane) |

| I just think it puts everybody on the same page and allows for better communication. Because there's so many different people involved a lot of times with a client's care, it kind of gets us all on the same page. (Nikki) |

Participants described many aspects of the dental hygiene treatment planning process, including the importance of the DHDx. The care plans included detailed information on what treatment, nutritional counseling, education, and referrals were recommended. Additionally, participants determined the number of appointments, length of each appointment, and what treatment would be included at each appointment. These dental hygienists proposed necessary referrals, discussed the cost of the treatment, and at times assigned insurance codes. Recommended re-evaluation and recare intervals were generally determined by the dental hygienist. This information was given to the dentist to get final approval for proposed treatment if needed, to the front office staff for financial considerations, and to the client to obtain informed consent.

Albert discussed how presenting an individualized dental hygiene treatment plan, based on the DHDx, to a client gave the client the necessary knowledge to accept or decline treatment. In regard to finances, clients gained “confidence that their money was going toward something worthwhile.” Michele emphasized that an important aspect of care planning was to explain to the client not only what treatment was recommended, but also why it was necessary. The goal of the care plan is to provide the best possible care and referrals to improve the client’s oral and overall health.

Further, participants discussed the referral of clients to medical and dental professionals in multiple disciplines as a necessary component of the care plan. Mike described interprofessional practice by referring clients to physicians to evaluate the status of diabetes, high blood pressure or medications. Jane referred to a dermatologist when a suspicious lesion was observed on a client’s face or lips. Elizabeth explained how the recognition of possible acid reflux, visible by lingual erosion, required further evaluation by a physician. She described to clients the importance of further evaluation by stating “this is a major concern because it puts you at a high risk for esophageal cancer and oral cancer, as well as eroding away the enamel.” Summing up her thoughts, Elizabeth stated, “The body is all interconnected and interlinked.”

Mia discussed the importance of referrals for emotional health and for alcohol dependency problems. She also explained the need for an interprofessional referral to a physician for a client who had excessive bleeding problems or for those who were not responding to appropriate dental hygiene treatment. She made clear to those clients that a medical examination was recommended to ascertain if a systemic problem existed. Nikki, in independent practice, stressed to the clients and to family members of cognitively impaired clients the importance of understanding the relationship between oral health and general health when recommending frequent dental hygiene visits. This recognition of the oral–systemic link confirmed the significance of including health factors when making care plan recommendations.

In addition to systemic conditions, many participants reported intraprofessional referrals to dental professionals, such as dentists, periodontists, orthodontists, endodontists, and maxillofacial surgeons. These dental hygienists recognized the need for a dentist or dental specialist referral. Intraprofessional practice was described by Elizabeth as “a partnership” between the dentist and the dental hygienists working to help one another and facilitate collaboration. Nikki, who works in independent practice, referred to a dentist or mobile dentist for conditions requiring a dental diagnosis and dental treatment. Supporting quotations pertaining to the referrals that participants make as part of the dental hygiene care plan appear in Table 7.

Dentists' trust

From the participants’ experience, dentists trust dental hygienists to diagnose. Participants related that the dentist does not perform an oral examination of the client at every dental hygiene appointment. In some cases, a dental examination is only performed once per year or if there is a chief complaint. Therefore, the dentist relies on the dental hygienist’s ability to diagnose oral conditions and inform them of relevant findings. Nikki, in independent practice, explained how the dentists rely on accurate dental hygiene diagnosing.

Supporting quotations for care plan referrals

|

|

| For referrals, most often the dentists or dental specialists, frequently physicians or other medical specialists. Occasionally, nurses, chiropractors, massage therapists. I've even recommended people to see exercise instructors. (Albert) |

| I refer them to their medical doctor. I've had patients who I've suspect have diabetes and so that's usually the referral to set up an appointment and I bug them at every appointment until they do it...I have given some referrals to some organizations like mental health, alcoholic programs. (Mia) |

| We typically refer to periodontists, orthodontists, endodontists, oral surgeons. Those are kind of our top four. We also work with a sleep study place to diagnose sleep apnea. We don't do any type of nutrition or smoking cessation of adults at all. If that's an issue, we usually refer them to their general doctor or general physician. (Elizabeth) |

| We refer out primarily to the endodontist, the periodontist, the orthodontist, and the oral surgeon. I've seen a couple abnormalities on someone's face or on their lips and I've suggested they see a dermatologist. (Jane) |

| I think it's [DHDx] pretty important because it allows you to be the bridge between the patient and the family and also the dentist of referral, if there are any dental issues. And it allows me to communicate to facilities that I visit via a written form creating an oral health record so that they can place that in their chart. It's good. It kind of creates a trail that they are getting taken care of and the need is being met with their oral care. And it allows me to better educate caretakers or the CNAs in areas that need improvement with daily care. (Nikki) |

| I saw signs of acid reflux, like a really red like soft palate and I saw a lot of inside lingual erosion on the teeth. I would ask the patient if you aware of any acid reflux or did you go through a period where you were throwing up a lot. This is a major concern because it puts you at a high risk for esophageal cancer and oral cancer as well as erosion of the enamel on your teeth. You need to get this under control. The medication required would be provided through your general practitioner. (Elizabeth) |

| If a patient has diabetes, I'll ask their HbA1c. You'd be surprised how many patients don't even know or don't even know the last time they did the test. I'll tell them they need to get it checked. The one on the high blood pressure medications, I'll ask the patient when's the last time you've seen your cardiologist or your physician regarding your blood pressure meds? If they said over a year, I'll tell them you should get that checked. (Mike) |

I feel that they [mobile dentists] count on us to diagnose correctly because they are making a trip based on the diagnosis that I see. And they base their treatment plan for that mobile visit based on what I see. They’re coming out [to treat the patient] with the knowledge and the anticipation that those are the lesions that they would be treating. (Nikki)

Leah described how communicating the DHDx to the dentist and then having the dentist reinforce the DHDx to the client “solidifies in the patient’s mind what is important.” This communication between the dental hygienist and the dentist ensured that the client received the necessary care.

Lastly, participants noted they have observed important findings to assist the dentist in performing a comprehensive diagnosis, and for the most part, the dentist has agreed with the DHDx. Specific quotations supporting these concepts are provided by Mia, Michele, and Jane.

There have been times where I brought a new patient, he’s done his exam, he’s diagnosing, and then they [patients] hop in my chair and then I find things that maybe he didn’t find. He’s thanked me on several occasions when these things have happened. The hygienist is a second pair of eyes for him. (Mia)

He [the dentist] makes my input seem valuable to the patient and that has given me a lot of confidence and makes me want to make sure my diagnosis is good and that I’m looking for those things and just not leaving it in his hands; 99 times out of a 100 my dentist does agree with what I’ve suggested for the patient. (Michele)

The dentist says, “Good job, Jane, that’s a good catch and good eye.” More times than not, he agrees with my diagnosis. That is a cavity. That is a problem. I trust you and 99% of the time he agrees with my diagnosis and my treating plans. (Jane)

This qualitative descriptive study explored DHDx in clinical practice and is a unique addition to the scientific body of knowledge. The findings from this investigation might expand the breadth of professional associations’ definitions of DHDx. Similarities between this study and current association definitions of DHDx exist in the areas of assessment findings determining the DHDx and the use of the DHDx to plan dental hygiene interventions.