Research Paper

- Icon Calendar 11 June 2024

- Icon Page 2825 words

- Icon Clock 13 min read

A research paper is a product of seeking information, analysis, human thinking, and time. Basically, when scholars want to get answers to questions, they start to search for information to expand, use, approve, or deny findings. In simple words, research papers are results of processes by considering writing works and following specific requirements. Besides, scientists study and expand many theories, developing social or technological aspects of human science. However, in order to provide a quality product, they need to know the definition of such a work, its characteristics, type, structure, format, and how to write it in 7 steps.

What Is a Research Paper and Its Purpose

According to its definition, a research paper is a detailed and structured academic document that presents an individual’s analysis, interpretation, or argument based on existing knowledge and literature. The main purpose of writing a research paper is to contribute to existing literature, develop critical thinking and scientific skills, support academic and professional growth, share findings, demonstrate knowledge and competence, and encourage lifelong learning (Wankhade, 2018). Moreover, such a work is one of the types of papers where scholars analyze questions or topics, look for secondary sources, and write papers on defined themes. For example, if an assignment is to write about some causes of global warming or any other topic, a person must write a research proposal on it, analyzing important points and credible sources (Goodson, 2024). Although essays focus on personal knowledge, writing a scholarly document means analyzing sources by following academic standards. In turn, scientists must meet the strict structure of research papers (Busse & August, 2020). As such, writers need to analyze their topics, start to search for sources, cover key aspects, process credible articles, and organize final studies properly. However, a research paper’s length can vary significantly depending on its academic level and purpose.

- Length: Typically 2-10 pages.

- Word Count: Approximately 500-2,500 words.

- Length: Usually 10-30 pages.

- Word Count: Around 2,500-7,500 words.

- Length: Master’s theses are generally 40-80 pages, while doctoral dissertations can be 100-300 pages or more.

- Word Count: Master’s theses are typically 10,000-20,000 words, and doctoral dissertations can range from 20,000-100,000 words, depending on the discipline and complexity.

- Length: Generally 8-12 pages for short articles, but review articles and comprehensive studies can be longer.

- Word Count: Approximately 3,000-8,000 words.

- Length: Usually 5-10 pages.

- Word Count: Around 2,000-4,000 words.

- Length: Typically 6-12 pages.

- Word Count: Approximately 2,500-6,000 words.

- Length: Varies widely, often 20-100 pages.

- Word Count: Around 5,000-30,000 words.

- Length: Generally 5-15 pages.

- Word Count: Approximately 2,000-5,000 words.

- Length: Varies, usually 20-40 pages per chapter.

- Word Count: Around 5,000-10,000 words.

- Length: Typically 100-300 pages.

- Word Count: Approximately 30,000-100,000 words.

Research Characteristics

Any type of work must meet some standards. By considering a research paper, this work must be written accordingly. In this case, their main characteristics are the length, style, format, and sources (Graham & McCoy, 2014). Firstly, the study’s length defines the number of needed sources to be analyzed. Then, the style must be formal and cover impersonal and inclusive language (Graham & McCoy, 2014). Moreover, the format means academic standards of how to organize final works, including its structure and norms. Finally, sources and their number define works as research papers because of the volume of analyzed information (Graham & McCoy, 2014). Hence, these characteristics must be considered while writing scholarly documents. In turn, general formatting guidelines are:

- Use a standard font (e.g., Times New Roman, 12-point).

- Double-space the text.

- Include 1-inch margins on all sides.

- Indent the first line of each paragraph.

- Number all pages consecutively, usually in the upper right corner.

Types of Research Papers

In general, the length of assignments can be different because of instructions. For example, there are two main types of research papers, such as typical and serious works. Firstly, a typical research paper may include definitive, argumentative, interpretive, and other works (Goodson, 2024). In this case, typical papers are from 2 to 10 pages, where students analyze study questions or specific topics. Then, a serious research composition is the expanded version of typical works. In turn, the length of such a paper is more than 10 pages (Wankhade, 2018). Basically, such works cover a serious analysis with many sources. Therefore, typical and serious works are two types that scholars should consider when writing their documents.

Typical Research Works

Basically, typical research works depend on assignments, the number of sources, and the paper’s length. So, this composition is usually a long essay with the analyzed evidence. For example, students in high school and college get such assignments to learn how to research and analyze topics (Goodson, 2024). In this case, they do not need to conduct serious experiments with the analysis and calculation of data. Moreover, students must use the Internet or libraries in searching for credible secondary sources to find potential answers to specific questions. As a result, students gather information on topics and learn how to take defined sides, present unique positions, or explain new directions (Goodson, 2024). Hence, they require an analysis of primary and secondary sources without serious experiments or data.

Serious Research Studies

Although long papers require a lot of time for finding and analyzing credible sources, real experiments are an integral part of research work. Firstly, scholars at universities need to analyze the information from past studies to expand or disapprove of topics (Wankhade, 2018). Then, if scholars want to prove specific positions or ideas, they must get real evidence. In this case, experiments can be surveys, calculations, or other types of data that scholars do personally. Moreover, a dissertation is a serious research paper that young scientists write based on the analysis of topics, data from conducted experiments, and conclusions at the end of work (Wankhade, 2018). Thus, they are studies that take a lot of time, analysis of sources with gained data, and interpretation of results.

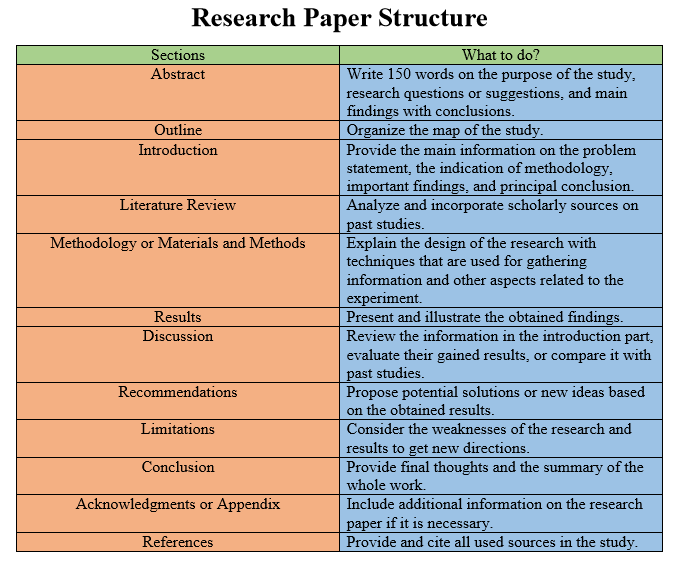

The structure and format of research papers depend on assignment requirements. In fact, when students get their assignments and instructions, they need to analyze specific research questions or topics, find reliable sources, and write final works. Basically, their structure and format consist of the abstract, outline, introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, recommendations, limitations, conclusion, acknowledgments, and references (Graham & McCoy, 2014). However, students may not include some of these sections because of assigned instructions that they have and specific types they must follow. For instance, if instructions are not supposed to conduct real experiments, the methodology section can be skipped because of the data’s absence. In turn, the structure of the final work consists of:

Join our satisfied customers who have received perfect papers from Wr1ter Team.

🔸 The First Part of a Research Study

Abstract or Executive Summary means the first section of a research paper that provides the study’s purpose, its questions or suggestions, and main findings with conclusions. Moreover, this paragraph of about 150 words should be written when the whole work is finished already (Graham & McCoy, 2014). Hence, abstract sections should describe key aspects of studies, including discussions about the relevance of findings.

Outline or Table of Contents serves as a clear map of the structure of a study.

Introduction provides the main information on problem statements, the indication of methodology, important findings, and principal conclusion. Basically, this section covers rationales behind the work or background research, explanation of the importance, defending its relevance, a brief description of experimental designs, defined study questions, hypotheses, or key aspects (Busse & August, 2020). Hence, scholars should provide a short overview of their studies.

🔸 Literature Review and Research or Experiment

Literature Review is needed for the analysis of past studies or scholarly articles to be familiar with research questions or topics. For example, this section summarizes and synthesizes arguments and ideas from scholarly sources without adding new contributions (Scholz, 2022). In turn, this part is organized around arguments or ideas, not sources.

Methodology or Materials and Methods covers explanations of research designs. Basically, techniques for gathering information and other aspects related to experiments must be described in a research paper. For instance, students and scholars document all specialized materials and general procedures (Turbek et al., 2016). In this case, individuals may use some or all of the methods in further studies or judge the scientific merit of the work. Moreover, scientists should explain how they are going to conduct their experiments.

Results mean the gained information or data after the study or experiment. Basically, scholars should present and illustrate their findings (Turbek et al., 2016). Moreover, this section may include tables or figures.

🔸 Analysis of Findings

Discussion is a section where scientists review the information in the introduction part, evaluate gained results, or compare it with past studies. In particular, students and scholars interpret gained data or findings in appropriate depth. For example, if results differ from expectations at the beginning, scientists should explain why that may have happened (Turbek et al., 2016). However, if results agree with rationales, scientists should describe theories that the evidence is supported.

Recommendations take their roots from a discussion section where scholars propose potential solutions or new ideas based on obtained results. In this case, if scientists have any recommendations on how to improve this research so that other scholars can use evidence in further studies, they must write what they think in this section (Graham & McCoy, 2014). Besides, authors can provide their suggestions for further investigation after their evaluations.

Limitations mean a consideration of research weaknesses and results to get new directions. For instance, if scholars find any limitations in their studies that may affect experiments, scholars must not use such knowledge because of the same mistakes (Busse & August, 2020). Moreover, scientists should avoid contradicting results, and, even more, they must write them in this section.

🔸 The Final Part of a Conducted Research

Conclusion includes final claims of a research paper based on findings. Basically, this section covers final thoughts and the summary of the whole work. Moreover, this section may be used instead of limitations and recommendations that would be too small by themselves (Wankhade, 2018). In this case, scientists do not need to use headings as recommendations and limitations.

Acknowledgments or Appendix may take different forms, from paragraphs to charts. In this section, scholars include additional information about what they did.

References mean a section where students, scholars, or scientists provide all used sources by following the format and academic rules.

How to Write a Research Paper in 7 Steps

Writing any research paper requires following a systematic process. Firstly, writers need to select a focused topic they want to analyze. To achieve this objective, comprehensive preliminary research must be conducted to gather credible and relevant sources (Scholz, 2022). After reviewing the existing literature, writers must develop a clear and concise thesis statement sentence to guide the direction of their studies. Then, organizing the main arguments and evidence into a detailed outline ensures a coherent structure. In turn, the initial draft should be started with a compelling introduction, proceeded with body paragraphs that substantiate the thesis through analysis, and ended with a conclusion that underscores the study’s importance (Turbek et al., 2016). Basically, concluding the work by summarizing the findings and emphasizing the significance of the study is crucial. Moreover, revising and editing for content, coherence, and clarity ensures quality (Busse & August, 2020). Finally, proofreading for grammatical accuracy and ensuring adherence to the required formatting guidelines is necessary before submitting the final paper. Hence, when starting a research paper, writers should do the next:

Step 1: Choose a Topic

- Select a Broad Subject: Begin by identifying a specific subject or theme of interest.

- Narrow Down Your Topic: Focus on a specific aspect of the subject or theme to make your examination more focused.

- Establish the Background: Do a preliminary analysis of sources to ensure there is enough information available and refine your topic further.

- Formulate a Research Question : Create a first draft of a clear, concise research question or thesis statement to guide your study.

Step 2: Conduct Preliminary Analysis

- Gather Credible Sources: Use books, academic journals, scholarly articles, reputable websites, and other primary and secondary sources.

- Choose Only Relevant Sources: Review chosen sources for their content and pick only relevant ones.

- Take Notes: Organize your notes, highlighting key points and evidence and how they relate to your initial thesis.

- Create an Annotated Bibliography: Summarize each source in one paragraph and note how it will contribute to your paper.

Step 3: Develop a Working Thesis Statement

- Be Specific: Revise your initial thesis, making it a working one, outlining the main argument or position of your paper.

- Make It Debatable: Ensure that your working thesis presents a viewpoint that others might challenge or debate.

- Be Concise: Write your working thesis statement in one or two sentences.

- Stay Focused: Your working thesis must be focused and specific.

Step 4: Create an Outline

- Beginning: Outline your opening paragraph, including your working thesis statement.

- Middle Sections : Separate your body into sections with headings for each main point or argument and include sub-points and supporting evidence.

- Ending: Plan your concluding section to summarize your findings and restate your thesis in the light of the evidence presented.

- The List of Sources: Finish your outline by providing citation entries of your sources.

Step 5: Write the First Draft

- Introduction: Start with an engaging opening, provide background information, and state your thesis.

- Body Section: Each body paragraph should focus on a single idea and start with a specific topic sentence, followed by evidence and analysis that supports your thesis.

- Conclusion: Summarize your arguments, restate the importance of your topic, and suggest further investigation, analysis, examination, or possible implications.

- Reference Page: Include the list of references used in your first draft.

Step 6: Revise and Edit

- Content Review: Check for clarity, coherence, and whether each part supports your thesis.

- Structure and Flow: Ensure logical flow of ideas between sections and paragraphs.

- Grammar and Style: Correct grammatical errors, improve sentence structure, and refine your writing style.

- Citations: Ensure all sources are correctly cited in your chosen citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, Harvard, etc.).

Step 7: Finalize Your Paper

- Proofread: Carefully proofread for any remaining errors or typos.

- Format: Ensure your paper adheres to the required format, including title page, headers, font, and margins.

- Reference List: Double-check your bibliography, reference, or works cited page for accuracy.

- Submit: Make sure to submit your paper by the deadline.

In conclusion, a research paper is a formal academic document designed to provide a detailed analysis, interpretation, or argument based on in-depth study. Its structured format includes providing opening components, such as the abstract, outline, and introduction; study aspects, such as literature review, methodology, and results; analysis of findings, such as discussion, recommendations, and limitations; and final parts, such as conclusion, acknowledgments, appendices, and references. Understanding the essential elements and adhering to academic standards ensures the creation of a well-organized and meaningful research paper.

Busse, C., & August, E. (2020). How to write and publish a research paper for a peer-reviewed journal. Journal of Cancer Education , 36 (5), 909–913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Goodson, P. (2024). Becoming an academic writer: 50 exercises for paced, productive, and powerful writing . Sage.

Graham, L., & McCoy, I. (2014). How to write a great research paper: A step-by-step handbook. Incentive Publications by World Book.

Scholz, F. (2022). Writing and publishing a scientific paper. ChemTexts , 8 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40828-022-00160-7

Turbek, S. P., Chock, T. M., Donahue, K., Havrilla, C. A., Oliverio, A. M., Polutchko, S. K., Shoemaker, L. G., & Vimercati, L. (2016). Scientific writing made easy: A step‐by‐step guide to undergraduate writing in the Biological Sciences. The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America , 97 (4), 417–426. https://doi.org/10.1002/bes2.1258

Wankhade, L. (2018). How to write and publish a research paper: A complete guide to writing and publishing a research paper . Independent Published.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Research Paper

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Research Paper

There will come a time in most students' careers when they are assigned a research paper. Such an assignment often creates a great deal of unneeded anxiety in the student, which may result in procrastination and a feeling of confusion and inadequacy. This anxiety frequently stems from the fact that many students are unfamiliar and inexperienced with this genre of writing. Never fear—inexperience and unfamiliarity are situations you can change through practice! Writing a research paper is an essential aspect of academics and should not be avoided on account of one's anxiety. In fact, the process of writing a research paper can be one of the more rewarding experiences one may encounter in academics. What is more, many students will continue to do research throughout their careers, which is one of the reasons this topic is so important.

Becoming an experienced researcher and writer in any field or discipline takes a great deal of practice. There are few individuals for whom this process comes naturally. Remember, even the most seasoned academic veterans have had to learn how to write a research paper at some point in their career. Therefore, with diligence, organization, practice, a willingness to learn (and to make mistakes!), and, perhaps most important of all, patience, students will find that they can achieve great things through their research and writing.

The pages in this section cover the following topic areas related to the process of writing a research paper:

- Genre - This section will provide an overview for understanding the difference between an analytical and argumentative research paper.

- Choosing a Topic - This section will guide the student through the process of choosing topics, whether the topic be one that is assigned or one that the student chooses themselves.

- Identifying an Audience - This section will help the student understand the often times confusing topic of audience by offering some basic guidelines for the process.

- Where Do I Begin - This section concludes the handout by offering several links to resources at Purdue, and also provides an overview of the final stages of writing a research paper.

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

Can you help me with a full paper template for this Abstract:

Background: Energy and sports drinks have gained popularity among diverse demographic groups, including adolescents, athletes, workers, and college students. While often used interchangeably, these beverages serve distinct purposes, with energy drinks aiming to boost energy and cognitive performance, and sports drinks designed to prevent dehydration and replenish electrolytes and carbohydrates lost during physical exertion.

Objective: To assess the nutritional quality of energy and sports drinks in Egypt.

Material and Methods: A cross-sectional study assessed the nutrient contents, including energy, sugar, electrolytes, vitamins, and caffeine, of sports and energy drinks available in major supermarkets in Cairo, Alexandria, and Giza, Egypt. Data collection involved photographing all relevant product labels and recording nutritional information. Descriptive statistics and appropriate statistical tests were employed to analyze and compare the nutritional values of energy and sports drinks.

Results: The study analyzed 38 sports drinks and 42 energy drinks. Sports drinks were significantly more expensive than energy drinks, with higher net content and elevated magnesium, potassium, and vitamin C. Energy drinks contained higher concentrations of caffeine, sugars, and vitamins B2, B3, and B6.

Conclusion: Significant nutritional differences exist between sports and energy drinks, reflecting their intended uses. However, these beverages’ high sugar content and calorie loads raise health concerns. Proper labeling, public awareness, and responsible marketing are essential to guide safe consumption practices in Egypt.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Saudi J Anaesth

- v.13(Suppl 1); 2019 Apr

Writing the title and abstract for a research paper: Being concise, precise, and meticulous is the key

Milind s. tullu.

Department of Pediatrics, Seth G.S. Medical College and KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

This article deals with formulating a suitable title and an appropriate abstract for an original research paper. The “title” and the “abstract” are the “initial impressions” of a research article, and hence they need to be drafted correctly, accurately, carefully, and meticulously. Often both of these are drafted after the full manuscript is ready. Most readers read only the title and the abstract of a research paper and very few will go on to read the full paper. The title and the abstract are the most important parts of a research paper and should be pleasant to read. The “title” should be descriptive, direct, accurate, appropriate, interesting, concise, precise, unique, and should not be misleading. The “abstract” needs to be simple, specific, clear, unbiased, honest, concise, precise, stand-alone, complete, scholarly, (preferably) structured, and should not be misrepresentative. The abstract should be consistent with the main text of the paper, especially after a revision is made to the paper and should include the key message prominently. It is very important to include the most important words and terms (the “keywords”) in the title and the abstract for appropriate indexing purpose and for retrieval from the search engines and scientific databases. Such keywords should be listed after the abstract. One must adhere to the instructions laid down by the target journal with regard to the style and number of words permitted for the title and the abstract.

Introduction

This article deals with drafting a suitable “title” and an appropriate “abstract” for an original research paper. Because the “title” and the “abstract” are the “initial impressions” or the “face” of a research article, they need to be drafted correctly, accurately, carefully, meticulously, and consume time and energy.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] Often, these are drafted after the complete manuscript draft is ready.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 9 , 10 , 11 ] Most readers will read only the title and the abstract of a published research paper, and very few “interested ones” (especially, if the paper is of use to them) will go on to read the full paper.[ 1 , 2 ] One must remember to adhere to the instructions laid down by the “target journal” (the journal for which the author is writing) regarding the style and number of words permitted for the title and the abstract.[ 2 , 4 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 12 ] Both the title and the abstract are the most important parts of a research paper – for editors (to decide whether to process the paper for further review), for reviewers (to get an initial impression of the paper), and for the readers (as these may be the only parts of the paper available freely and hence, read widely).[ 4 , 8 , 12 ] It may be worth for the novice author to browse through titles and abstracts of several prominent journals (and their target journal as well) to learn more about the wording and styles of the titles and abstracts, as well as the aims and scope of the particular journal.[ 5 , 7 , 9 , 13 ]

The details of the title are discussed under the subheadings of importance, types, drafting, and checklist.

Importance of the title

When a reader browses through the table of contents of a journal issue (hard copy or on website), the title is the “ first detail” or “face” of the paper that is read.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 13 ] Hence, it needs to be simple, direct, accurate, appropriate, specific, functional, interesting, attractive/appealing, concise/brief, precise/focused, unambiguous, memorable, captivating, informative (enough to encourage the reader to read further), unique, catchy, and it should not be misleading.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 9 , 12 ] It should have “just enough details” to arouse the interest and curiosity of the reader so that the reader then goes ahead with studying the abstract and then (if still interested) the full paper.[ 1 , 2 , 4 , 13 ] Journal websites, electronic databases, and search engines use the words in the title and abstract (the “keywords”) to retrieve a particular paper during a search; hence, the importance of these words in accessing the paper by the readers has been emphasized.[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 12 , 14 ] Such important words (or keywords) should be arranged in appropriate order of importance as per the context of the paper and should be placed at the beginning of the title (rather than the later part of the title, as some search engines like Google may just display only the first six to seven words of the title).[ 3 , 5 , 12 ] Whimsical, amusing, or clever titles, though initially appealing, may be missed or misread by the busy reader and very short titles may miss the essential scientific words (the “keywords”) used by the indexing agencies to catch and categorize the paper.[ 1 , 3 , 4 , 9 ] Also, amusing or hilarious titles may be taken less seriously by the readers and may be cited less often.[ 4 , 15 ] An excessively long or complicated title may put off the readers.[ 3 , 9 ] It may be a good idea to draft the title after the main body of the text and the abstract are drafted.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]

Types of titles

Titles can be descriptive, declarative, or interrogative. They can also be classified as nominal, compound, or full-sentence titles.

Descriptive or neutral title

This has the essential elements of the research theme, that is, the patients/subjects, design, interventions, comparisons/control, and outcome, but does not reveal the main result or the conclusion.[ 3 , 4 , 12 , 16 ] Such a title allows the reader to interpret the findings of the research paper in an impartial manner and with an open mind.[ 3 ] These titles also give complete information about the contents of the article, have several keywords (thus increasing the visibility of the article in search engines), and have increased chances of being read and (then) being cited as well.[ 4 ] Hence, such descriptive titles giving a glimpse of the paper are generally preferred.[ 4 , 16 ]

Declarative title

This title states the main finding of the study in the title itself; it reduces the curiosity of the reader, may point toward a bias on the part of the author, and hence is best avoided.[ 3 , 4 , 12 , 16 ]

Interrogative title

This is the one which has a query or the research question in the title.[ 3 , 4 , 16 ] Though a query in the title has the ability to sensationalize the topic, and has more downloads (but less citations), it can be distracting to the reader and is again best avoided for a research article (but can, at times, be used for a review article).[ 3 , 6 , 16 , 17 ]

From a sentence construct point of view, titles may be nominal (capturing only the main theme of the study), compound (with subtitles to provide additional relevant information such as context, design, location/country, temporal aspect, sample size, importance, and a provocative or a literary; for example, see the title of this review), or full-sentence titles (which are longer and indicate an added degree of certainty of the results).[ 4 , 6 , 9 , 16 ] Any of these constructs may be used depending on the type of article, the key message, and the author's preference or judgement.[ 4 ]

Drafting a suitable title

A stepwise process can be followed to draft the appropriate title. The author should describe the paper in about three sentences, avoiding the results and ensuring that these sentences contain important scientific words/keywords that describe the main contents and subject of the paper.[ 1 , 4 , 6 , 12 ] Then the author should join the sentences to form a single sentence, shorten the length (by removing redundant words or adjectives or phrases), and finally edit the title (thus drafted) to make it more accurate, concise (about 10–15 words), and precise.[ 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 9 ] Some journals require that the study design be included in the title, and this may be placed (using a colon) after the primary title.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 14 ] The title should try to incorporate the Patients, Interventions, Comparisons and Outcome (PICO).[ 3 ] The place of the study may be included in the title (if absolutely necessary), that is, if the patient characteristics (such as study population, socioeconomic conditions, or cultural practices) are expected to vary as per the country (or the place of the study) and have a bearing on the possible outcomes.[ 3 , 6 ] Lengthy titles can be boring and appear unfocused, whereas very short titles may not be representative of the contents of the article; hence, optimum length is required to ensure that the title explains the main theme and content of the manuscript.[ 4 , 5 , 9 ] Abbreviations (except the standard or commonly interpreted ones such as HIV, AIDS, DNA, RNA, CDC, FDA, ECG, and EEG) or acronyms should be avoided in the title, as a reader not familiar with them may skip such an article and nonstandard abbreviations may create problems in indexing the article.[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 9 , 12 ] Also, too much of technical jargon or chemical formulas in the title may confuse the readers and the article may be skipped by them.[ 4 , 9 ] Numerical values of various parameters (stating study period or sample size) should also be avoided in the titles (unless deemed extremely essential).[ 4 ] It may be worthwhile to take an opinion from a impartial colleague before finalizing the title.[ 4 , 5 , 6 ] Thus, multiple factors (which are, at times, a bit conflicting or contrasting) need to be considered while formulating a title, and hence this should not be done in a hurry.[ 4 , 6 ] Many journals ask the authors to draft a “short title” or “running head” or “running title” for printing in the header or footer of the printed paper.[ 3 , 12 ] This is an abridged version of the main title of up to 40–50 characters, may have standard abbreviations, and helps the reader to navigate through the paper.[ 3 , 12 , 14 ]

Checklist for a good title

Table 1 gives a checklist/useful tips for drafting a good title for a research paper.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 12 ] Table 2 presents some of the titles used by the author of this article in his earlier research papers, and the appropriateness of the titles has been commented upon. As an individual exercise, the reader may try to improvise upon the titles (further) after reading the corresponding abstract and full paper.

Checklist/useful tips for drafting a good title for a research paper

| The title needs to be simple and direct |

| It should be interesting and informative |

| It should be specific, accurate, and functional (with essential scientific “keywords” for indexing) |

| It should be concise, precise, and should include the main theme of the paper |

| It should not be misleading or misrepresentative |

| It should not be too long or too short (or cryptic) |

| It should avoid whimsical or amusing words |

| It should avoid nonstandard abbreviations and unnecessary acronyms (or technical jargon) |

| Title should be SPICED, that is, it should include Setting, Population, Intervention, Condition, End-point, and Design |

| Place of the study and sample size should be mentioned only if it adds to the scientific value of the title |

| Important terms/keywords should be placed in the beginning of the title |

| Descriptive titles are preferred to declarative or interrogative titles |

| Authors should adhere to the word count and other instructions as specified by the target journal |

Some titles used by author of this article in his earlier publications and remark/comment on their appropriateness

| Title | Comment/remark on the contents of the title |

|---|---|

| Comparison of Pediatric Risk of Mortality III, Pediatric Index of Mortality 2, and Pediatric Index of Mortality 3 Scores in Predicting Mortality in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit | Long title (28 words) capturing the main theme; site of study is mentioned |

| A Prospective Antibacterial Utilization Study in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of a Tertiary Referral Center | Optimum number of words capturing the main theme; site of study is mentioned |

| Study of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit | The words “study of” can be deleted |

| Clinical Profile, Co-Morbidities & Health Related Quality of Life in Pediatric Patients with Allergic Rhinitis & Asthma | Optimum number of words; population and intervention mentioned |

| Benzathine Penicillin Prophylaxis in Children with Rheumatic Fever (RF)/Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD): A Study of Compliance | Subtitle used to convey the main focus of the paper. It may be preferable to use the important word “compliance” in the beginning of the title rather than at the end. Abbreviations RF and RHD can be deleted as corresponding full forms have already been mentioned in the title itself |

| Performance of PRISM (Pediatric Risk of Mortality) Score and PIM (Pediatric Index of Mortality) Score in a Tertiary Care Pediatric ICU | Abbreviations used. “ICU” may be allowed as it is a commonly used abbreviation. Abbreviations PRISM and PIM can be deleted as corresponding full forms are already used in the title itself |

| Awareness of Health Care Workers Regarding Prophylaxis for Prevention of Transmission of Blood-Borne Viral Infections in Occupational Exposures | Slightly long title (18 words); theme well-captured |

| Isolated Infective Endocarditis of the Pulmonary Valve: An Autopsy Analysis of Nine Cases | Subtitle used to convey additional details like “autopsy” (i.e., postmortem analysis) and “nine” (i.e., number of cases) |

| Atresia of the Common Pulmonary Vein - A Rare Congenital Anomaly | Subtitle used to convey importance of the paper/rarity of the condition |

| Psychological Consequences in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Survivors: The Neglected Outcome | Subtitle used to convey importance of the paper and to make the title more interesting |

| Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease: Clinical Profile of 550 patients in India | Number of cases (550) emphasized because it is a large series; country (India) is mentioned in the title - will the clinical profile of patients with rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease vary from country to country? May be yes, as the clinical features depend on the socioeconomic and cultural background |

| Neurological Manifestations of HIV Infection | Short title; abbreviation “HIV” may be allowed as it is a commonly used abbreviation |

| Krabbe Disease - Clinical Profile | Very short title (only four words) - may miss out on the essential keywords required for indexing |

| Experience of Pediatric Tetanus Cases from Mumbai | City mentioned (Mumbai) in the title - one needs to think whether it is required in the title |

The Abstract

The details of the abstract are discussed under the subheadings of importance, types, drafting, and checklist.

Importance of the abstract

The abstract is a summary or synopsis of the full research paper and also needs to have similar characteristics like the title. It needs to be simple, direct, specific, functional, clear, unbiased, honest, concise, precise, self-sufficient, complete, comprehensive, scholarly, balanced, and should not be misleading.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 17 ] Writing an abstract is to extract and summarize (AB – absolutely, STR – straightforward, ACT – actual data presentation and interpretation).[ 17 ] The title and abstracts are the only sections of the research paper that are often freely available to the readers on the journal websites, search engines, and in many abstracting agencies/databases, whereas the full paper may attract a payment per view or a fee for downloading the pdf copy.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 ] The abstract is an independent and stand-alone (that is, well understood without reading the full paper) section of the manuscript and is used by the editor to decide the fate of the article and to choose appropriate reviewers.[ 2 , 7 , 10 , 12 , 13 ] Even the reviewers are initially supplied only with the title and the abstract before they agree to review the full manuscript.[ 7 , 13 ] This is the second most commonly read part of the manuscript, and therefore it should reflect the contents of the main text of the paper accurately and thus act as a “real trailer” of the full article.[ 2 , 7 , 11 ] The readers will go through the full paper only if they find the abstract interesting and relevant to their practice; else they may skip the paper if the abstract is unimpressive.[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 13 ] The abstract needs to highlight the selling point of the manuscript and succeed in luring the reader to read the complete paper.[ 3 , 7 ] The title and the abstract should be constructed using keywords (key terms/important words) from all the sections of the main text.[ 12 ] Abstracts are also used for submitting research papers to a conference for consideration for presentation (as oral paper or poster).[ 9 , 13 , 17 ] Grammatical and typographic errors reflect poorly on the quality of the abstract, may indicate carelessness/casual attitude on part of the author, and hence should be avoided at all times.[ 9 ]

Types of abstracts

The abstracts can be structured or unstructured. They can also be classified as descriptive or informative abstracts.

Structured and unstructured abstracts

Structured abstracts are followed by most journals, are more informative, and include specific subheadings/subsections under which the abstract needs to be composed.[ 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 17 , 18 ] These subheadings usually include context/background, objectives, design, setting, participants, interventions, main outcome measures, results, and conclusions.[ 1 ] Some journals stick to the standard IMRAD format for the structure of the abstracts, and the subheadings would include Introduction/Background, Methods, Results, And (instead of Discussion) the Conclusion/s.[ 1 , 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 17 , 18 ] Structured abstracts are more elaborate, informative, easy to read, recall, and peer-review, and hence are preferred; however, they consume more space and can have same limitations as an unstructured abstract.[ 7 , 9 , 18 ] The structured abstracts are (possibly) better understood by the reviewers and readers. Anyway, the choice of the type of the abstract and the subheadings of a structured abstract depend on the particular journal style and is not left to the author's wish.[ 7 , 10 , 12 ] Separate subheadings may be necessary for reporting meta-analysis, educational research, quality improvement work, review, or case study.[ 1 ] Clinical trial abstracts need to include the essential items mentioned in the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) guidelines.[ 7 , 9 , 14 , 19 ] Similar guidelines exist for various other types of studies, including observational studies and for studies of diagnostic accuracy.[ 20 , 21 ] A useful resource for the above guidelines is available at www.equator-network.org (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research). Unstructured (or non-structured) abstracts are free-flowing, do not have predefined subheadings, and are commonly used for papers that (usually) do not describe original research.[ 1 , 7 , 9 , 10 ]

The four-point structured abstract: This has the following elements which need to be properly balanced with regard to the content/matter under each subheading:[ 9 ]

Background and/or Objectives: This states why the work was undertaken and is usually written in just a couple of sentences.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 ] The hypothesis/study question and the major objectives are also stated under this subheading.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 ]

Methods: This subsection is the longest, states what was done, and gives essential details of the study design, setting, participants, blinding, sample size, sampling method, intervention/s, duration and follow-up, research instruments, main outcome measures, parameters evaluated, and how the outcomes were assessed or analyzed.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 ]

Results/Observations/Findings: This subheading states what was found, is longer, is difficult to draft, and needs to mention important details including the number of study participants, results of analysis (of primary and secondary objectives), and include actual data (numbers, mean, median, standard deviation, “P” values, 95% confidence intervals, effect sizes, relative risks, odds ratio, etc.).[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 ]

Conclusions: The take-home message (the “so what” of the paper) and other significant/important findings should be stated here, considering the interpretation of the research question/hypothesis and results put together (without overinterpreting the findings) and may also include the author's views on the implications of the study.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 ]

The eight-point structured abstract: This has the following eight subheadings – Objectives, Study Design, Study Setting, Participants/Patients, Methods/Intervention, Outcome Measures, Results, and Conclusions.[ 3 , 9 , 18 ] The instructions to authors given by the particular journal state whether they use the four- or eight-point abstract or variants thereof.[ 3 , 14 ]

Descriptive and Informative abstracts

Descriptive abstracts are short (75–150 words), only portray what the paper contains without providing any more details; the reader has to read the full paper to know about its contents and are rarely used for original research papers.[ 7 , 10 ] These are used for case reports, reviews, opinions, and so on.[ 7 , 10 ] Informative abstracts (which may be structured or unstructured as described above) give a complete detailed summary of the article contents and truly reflect the actual research done.[ 7 , 10 ]

Drafting a suitable abstract

It is important to religiously stick to the instructions to authors (format, word limit, font size/style, and subheadings) provided by the journal for which the abstract and the paper are being written.[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 13 ] Most journals allow 200–300 words for formulating the abstract and it is wise to restrict oneself to this word limit.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 22 ] Though some authors prefer to draft the abstract initially, followed by the main text of the paper, it is recommended to draft the abstract in the end to maintain accuracy and conformity with the main text of the paper (thus maintaining an easy linkage/alignment with title, on one hand, and the introduction section of the main text, on the other hand).[ 2 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 ] The authors should check the subheadings (of the structured abstract) permitted by the target journal, use phrases rather than sentences to draft the content of the abstract, and avoid passive voice.[ 1 , 7 , 9 , 12 ] Next, the authors need to get rid of redundant words and edit the abstract (extensively) to the correct word count permitted (every word in the abstract “counts”!).[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 13 ] It is important to ensure that the key message, focus, and novelty of the paper are not compromised; the rationale of the study and the basis of the conclusions are clear; and that the abstract is consistent with the main text of the paper.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 , 22 ] This is especially important while submitting a revision of the paper (modified after addressing the reviewer's comments), as the changes made in the main (revised) text of the paper need to be reflected in the (revised) abstract as well.[ 2 , 10 , 12 , 14 , 22 ] Abbreviations should be avoided in an abstract, unless they are conventionally accepted or standard; references, tables, or figures should not be cited in the abstract.[ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 ] It may be worthwhile not to rush with the abstract and to get an opinion by an impartial colleague on the content of the abstract; and if possible, the full paper (an “informal” peer-review).[ 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 17 ] Appropriate “Keywords” (three to ten words or phrases) should follow the abstract and should be preferably chosen from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) list of the U.S. National Library of Medicine ( https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov/search ) and are used for indexing purposes.[ 2 , 3 , 11 , 12 ] These keywords need to be different from the words in the main title (the title words are automatically used for indexing the article) and can be variants of the terms/phrases used in the title, or words from the abstract and the main text.[ 3 , 12 ] The ICMJE (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors; http://www.icmje.org/ ) also recommends publishing the clinical trial registration number at the end of the abstract.[ 7 , 14 ]

Checklist for a good abstract

Table 3 gives a checklist/useful tips for formulating a good abstract for a research paper.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 , 22 ]

Checklist/useful tips for formulating a good abstract for a research paper

| The abstract should have simple language and phrases (rather than sentences) |

| It should be informative, cohesive, and adhering to the structure (subheadings) provided by the target journal. Structured abstracts are preferred over unstructured abstracts |

| It should be independent and stand-alone/complete |

| It should be concise, interesting, unbiased, honest, balanced, and precise |

| It should not be misleading or misrepresentative; it should be consistent with the main text of the paper (especially after a revision is made) |

| It should utilize the full word capacity allowed by the journal so that most of the actual scientific facts of the main paper are represented in the abstract |

| It should include the key message prominently |

| It should adhere to the style and the word count specified by the target journal (usually about 250 words) |

| It should avoid nonstandard abbreviations and (if possible) avoid a passive voice |

| Authors should list appropriate “keywords” below the abstract (keywords are used for indexing purpose) |

Concluding Remarks

This review article has given a detailed account of the importance and types of titles and abstracts. It has also attempted to give useful hints for drafting an appropriate title and a complete abstract for a research paper. It is hoped that this review will help the authors in their career in medical writing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Dr. Hemant Deshmukh - Dean, Seth G.S. Medical College & KEM Hospital, for granting permission to publish this manuscript.

What Should Be the Characteristics of a Good Research Paper?

by team@blp

In miscellaneous.

When people want to get answers to various issues, they search for information on the problems. From their findings, they expand them, aiming to agree or refute them. Research papers are common assignments in colleges.

They follow specific research and writing guidelines to answer particular questions or assigned topics . They look into the critical topic of credible research sources and argue their findings in an orderly manner. To be termed as good, the research paper must bear the following characteristics.

In this Article

Gives credit to previous research work on the topic

- It’s hooked on a relevant research question.

It must be based on appropriate, systematic research methods

- The information must be accurate and controlled.

- It must be verifiable and rigorous.

It must be clear and coherent.

It must be dealt with critical analysis., it must be original., it must possess ethical integrity., be careful with the topic you choose, decide the sources you want to use, create your thesis statement , plan your points, write your paper, characteristics of a good research paper.

Writing a research paper aims to discover new knowledge, but the knowledge must have a base. Its base is the research done previously by other scholars. The student must acknowledge the previous research and avoid duplicating it in their writing process.

A college student must engage in deep research work to create a credible research paper. This makes the process lengthy and complex when choosing your topic, selecting sources, and developing its design. In addition, it requires a great deal of knowledge to piece everything together. Fortunately, Studyclerk will give you professional help anytime you need it. If you do not have enough knowledge and time to write a paper on your own, you can ask for research paper help by StudyClerk, where experienced paper writers will write your paper in no time. You can trust their expert writers to handle your assignment well and get a well-written paper in a short time.

It’s hooked on a relevant research question .

All the time a student spends researching multiple sources is to answer a specific research question. The question must be relevant to the current needs. This question guides them into the information they use or the line of argument they take.

The methodology of research a student chooses will determine the value of the information they get or give. The methods must be valid and credible to provide reliable outcomes. Whether the student chooses a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed approach, they must all be valuable and relevant.

The information must be accurate and controlled .

A good research paper cannot be generalized information but specific, scientific information. That is why they must include references and record tests or information accurately. Moreover, they must keep the information controlled by staying within the topic from the first step of research to the last.

It must be verifiable and rigorous .

The student must use information or write arguments that can be verified. If it’s a test, it must be replicable by another researcher. The sources must be verifiable and accurate. Without rigorous deep research strategies , the paper cannot be good. They must put a lot of labor into both the writing and research processes to ensure the information is credible, clear, concise, original, and precise.

The paper should be written clearly, concisely with logical progression from one section to another. This includes having a well-structured introduction, body, and conclusion. Each section should be coherent and contribute directly to the reader’s understanding of the research question, findings, and implications.

A good research paper involves not just reporting facts and data, but also critically analyzing them. This means evaluating the strengths and limitations of the research, discussing the implications of findings, and situating the results within the broader field of study. The analysis should engage with different perspectives and theories, showing an awareness of the complexity of the topic.

While it builds on previous research, a good research paper offers new insights or approaches to the topic. This could be through presenting new findings, developing a novel theoretical approach, or offering a unique combination of existing knowledge. Originality, especially the research statement , is crucial for advancing knowledge and adding value to the field.

Ethical considerations are paramount in research. A good research paper adheres to ethical standards when it comes to data collection, reporting, and analysis. This includes obtaining necessary permissions for using data, respecting participant privacy in the case of human subjects, and being transparent about any conflicts of interest.

How to write a good research paper

To write a good research paper, you must first understand what kind of question you have been assigned. Then, you will choose the best topic that you will love to write about. The following points will help you write a good research paper.

You must select a topic you love. Go for a topic that will be easier to research, which will give you a broader area of study.

Your instructor doesn’t restrict you on the sources you must use. Broaden your mind so that you don’t limit yourself to specific sources of information. Sometimes you will get helpful information from sources you slightest thought as good.

Write your central statement to base your position on the research. Make it coherent contentious, and let it be a summary of your arguments.

Create an outline that will guide you when arguing your points

- Start with the most vital points and smooth the flow.

- Pay attention to paragraph structure and let your arguments be clear.

- Finish with a compelling conclusion, and don’t forget to cite your sources.

A research paper requires extensive research methods to get solid points for supporting your stand. First, the sources you use must be verifiable by any other researcher. You must ensure your research work is original for your paper to be credible. Third, each point should be coherent with each paragraph. Finally, your research findings must be tagged on the research question and provide answers that apply to the current society.

Author’s Bio

Helen Birk is an online freelance writer who holds an outstanding record of helping numerous students do their academic assignments. She is an expert in essays and thesis writing, and students simply love her for her high-quality work. In addition, she enjoys cycling, doing pencil sketching, and listening to spiritual podcasts in her free time.

7 Benefits of Pursuing a Degree in Education

Pursuing a degree in education can open many doors and provide a rewarding career path for those passionate about teaching and helping others. As the demand for qualified educators continues to grow, the benefits of obtaining an education degree become even more...

What Skills Are Gained from a Health Administration Degree?

Behind the scenes of healthcare, a skilled leader is at work. The smooth operation of hospitals, clinics, and other healthcare facilities depends on more than just medical expertise. It requires a strategic mind, a strong understanding of business, and a deep...

Scaling Tech Startups – From Idea to Global Expansion

The tech startup landscape is dynamic and filled with opportunities for rapid growth and innovation. Startups often begin with a groundbreaking idea, but turning that idea into a globally recognized brand requires strategic planning and execution. The process from a...

7 Main Benefits of Getting Your Master’s Degree In Education

Are you on the fence about studying further? Look, you’re not the only one, as there are a few contributing factors that make getting a postgraduate degree like your Master’s challenging. Studying can be a long, expensive, and sometimes tedious process, so it’s okay...

How to Build a Personal Development Plan for Career Success

How to Build a Personal Development Plan for Career Success I’ve been thinking a lot about career growth lately, and I wanted to share some thoughts on creating a killer personal development plan. Trust me, I’ve been there - feeling stuck and unsure of where my career...

Is A Communications Degree Worth It?

Are you considering doing a communications degree? You might have seen all these millionaire schemes on YouTube that say you don’t need to study to make millions, and they may work for some people. Still, the chances of this are one in a million. Getting a degree...

Take Your Networking Skills To The Next Level

Take Your Networking Skills To The Next Level One of the most valuable skills businessmen or entrepreneurs can learn is how to network effectively. In fact, networking is such a central component in the working world that it’s in almost every business deal. You might...

Discover How Much Homework To Expect In a College Literature Class

Explore How Much Homework To Expect In A College Literature Class Students who attend literature classes often seek help with literature homework. The reason for this necessity is that people are not accustomed to reading printed books anymore. Though literature helps...

Balancing Work and Study: 9 Things to Keep in Mind

Image Source Balancing work and study can be a tough challenge, especially when you're trying to excel in both. Whether you're a student working to support your education or a professional pursuing further studies, managing these responsibilities requires careful...

How to Study for an Online Master’s Degree in Education: 10 Tips

Image Source Pursuing a Master's in Education online can be a transformative experience that combines flexibility with a rigorous academic curriculum. This mode of learning allows you to advance your career in education without the constraints of traditional on-campus...

WANT MORE AMAZING CONTENT?

- Free GRE Practice Questions

- 100+ Personal Statement Templates

- 100+ Quotes to Kick Start Your Personal Statement

- 390 Adjectives to Use in a LOR

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

Glossary of research terms.

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

This glossary is intended to assist you in understanding commonly used terms and concepts when reading, interpreting, and evaluating scholarly research. Also included are common words and phrases defined within the context of how they apply to research in the social and behavioral sciences.

- Acculturation -- refers to the process of adapting to another culture, particularly in reference to blending in with the majority population [e.g., an immigrant adopting American customs]. However, acculturation also implies that both cultures add something to one another, but still remain distinct groups unto themselves.

- Accuracy -- a term used in survey research to refer to the match between the target population and the sample.

- Affective Measures -- procedures or devices used to obtain quantified descriptions of an individual's feelings, emotional states, or dispositions.

- Aggregate -- a total created from smaller units. For instance, the population of a county is an aggregate of the populations of the cities, rural areas, etc. that comprise the county. As a verb, it refers to total data from smaller units into a large unit.

- Anonymity -- a research condition in which no one, including the researcher, knows the identities of research participants.

- Baseline -- a control measurement carried out before an experimental treatment.

- Behaviorism -- school of psychological thought concerned with the observable, tangible, objective facts of behavior, rather than with subjective phenomena such as thoughts, emotions, or impulses. Contemporary behaviorism also emphasizes the study of mental states such as feelings and fantasies to the extent that they can be directly observed and measured.

- Beliefs -- ideas, doctrines, tenets, etc. that are accepted as true on grounds which are not immediately susceptible to rigorous proof.

- Benchmarking -- systematically measuring and comparing the operations and outcomes of organizations, systems, processes, etc., against agreed upon "best-in-class" frames of reference.

- Bias -- a loss of balance and accuracy in the use of research methods. It can appear in research via the sampling frame, random sampling, or non-response. It can also occur at other stages in research, such as while interviewing, in the design of questions, or in the way data are analyzed and presented. Bias means that the research findings will not be representative of, or generalizable to, a wider population.

- Case Study -- the collection and presentation of detailed information about a particular participant or small group, frequently including data derived from the subjects themselves.

- Causal Hypothesis -- a statement hypothesizing that the independent variable affects the dependent variable in some way.

- Causal Relationship -- the relationship established that shows that an independent variable, and nothing else, causes a change in a dependent variable. It also establishes how much of a change is shown in the dependent variable.

- Causality -- the relation between cause and effect.

- Central Tendency -- any way of describing or characterizing typical, average, or common values in some distribution.

- Chi-square Analysis -- a common non-parametric statistical test which compares an expected proportion or ratio to an actual proportion or ratio.

- Claim -- a statement, similar to a hypothesis, which is made in response to the research question and that is affirmed with evidence based on research.

- Classification -- ordering of related phenomena into categories, groups, or systems according to characteristics or attributes.

- Cluster Analysis -- a method of statistical analysis where data that share a common trait are grouped together. The data is collected in a way that allows the data collector to group data according to certain characteristics.

- Cohort Analysis -- group by group analytic treatment of individuals having a statistical factor in common to each group. Group members share a particular characteristic [e.g., born in a given year] or a common experience [e.g., entering a college at a given time].