Consumer Research in Social Media: Guidelines and Recommendations

Series: Methods and Protocols in Food Science > Book: Consumer Research Methods in Food Science

Overview | DOI: 10.1007/978-1-0716-3000-6_14

- Firmenich & Cie SAS, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

- Independent Consultant, Digital Data Intelligence, Geneva, Switzerland

This chapter focuses on understanding the general practices and some applications of social mediamediaresearchresearches in the food and beverage domain. The first part of the chapter is intended to give a general introduction and define what social

This chapter focuses on understanding the general practices and some applications of social mediamediaresearchresearches in the food and beverage domain. The first part of the chapter is intended to give a general introduction and define what social media is versus other types of media (mainstream media, reviews, etc.). It also explores the human relationship with social media as an extended “digital self,” and why the use of social media has exploded. An additional point is covered with the legal and ethical considerations required to perform researchresearches by using social media monitoring tools. The second and third parts of this chapter focus on general applications of social media researchresearches (exploratory studies, trend watch, netnography, and other applications) and then provide a detailed view of how to perform social media studies step-by-step: from the basic Boolean search formula to natural language processingNatural language processing (NLP) and human analysis. Finally, two case studies are shared to compare the results of social media researchresearches versus online quantitative tests. The objective of this comparison is to explain the strengths and limitations of each research and how they can be complementary, as they are usually compared in both academic and industrial applications.

Figures ( 0 ) & Videos ( 0 )

Experimental specifications, other keywords.

- Lunardo R, Jaud DA, Corsi AM (2021) The narcissistic wine consumer: how social attractiveness associated with wine prompts narcissists to engage in wine consumption. Food Qual Prefer 88:104107

- Arellano-Covarrubias A, Gómez-Corona C, Varela P, Escalona-Buendía HB (2019) Connecting flavors in social media: a cross cultural study with beer pairing. Food Res Int 115:303–310

- Simeone M, Scarpato D (2020) Sustainable consumption: how does social media affect food choices? J Clean Prod 277:124036

- Khan S, Umer R, Umer S, Naqvi S (2021) Antecedents of trust in using social media for E-government services: an empirical study in Pakistan. Technol Soc 64:101400

- Simmel G, Wolff KH (1964) The sociology of Georg Simmel. Free Press, Glencoe

- Lewis K, Kaufman J, Gonzalez M, Wimmer A, Christakis N (2008) Tastes, ties, and time: a new social network dataset using Facebook.com. Soc Networks 30(4):330–342

- Sibilia P (2017) La intimidad como espectáculo. FCE, Ciudad de Mexico

- Vidal L, Ares G, Jaeger SR (2018) Application of social media for consumer research. In: Ares G, Varela P (eds) Methods in consumer research. New approaches to classic methods, vol 1. Woodhead Publishing, UK

- Pittman M, Reich B (2016) Social media and loneliness: why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Comput Hum Behav 62:155–167

- McKee R (2013) Ethical issues in using social media for health and health care research. Health Policy 110:298–301

- Kaplan AM, Haenlein M (2010) Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus Horiz 53:59–68

- Edosomwan S, Prakasan SK, Kouame D, Watson J, Seymour T (2011) The history of social media and its impact on business. J Appl Manag Entrep 16(3):79–91

- Stillerman J (2015) The sociology of consumption. A global approach. POLITY, Cambridge

- Prada JM (2018) El ver y las imágenes en el tiempo de internet. AKAL/Estudios Visuales, Madrid

- Toubia O, Stephen AT (2013) Intrinsic vs. image-related utility in social media: why do people contribute content to Twitter? Mark Sci 32(3):368–392

- Balbi G, Magaudda P (2018) A history of digital media: an intermedia and global perspective. Routledge, New York

- Ko MC, Huang HH, Chen HH (2017, August) Paid review and paid writer detection. In: Proceedings of the international conference on web intelligence, pp 637–645

- Choi J, Yoon J, Chung J, Coh BY (2020) Social media analytics and business intelligence research: a systematic review. Inf Process Manag 57:102279

- Kaufman J (2008) Tastes, ties, and time: Facebook data release. Retrieved from: . March 2021 https://cyber.harvard.edu/node/94446

- Zimmer M (2008) More on the “anonymity” of the Facebook dataset – It’s Harvard College (Updated). Retrieved from: . March 2021 https://michaelzimmer.org/2008/10/03/more-on-the-anonymity-of-the-facebook-dataset-its-harvard-college/

- Zimmer M (2010) “But the data is already public”: on the ethics of research in Facebook. Ethics Inf Technol 12:313–325

- Liptak A (2018) The US government alleges Facebook enabled housing ad discrimination. The Verge

- Michaelidou N, Micevski M, Cadogan JHW (2021) Users’ ethical perceptions of social media research: conceptualisation and measurement. J Bus Res 124:684–694

- AOIR – Association of Internet Researchers (2019) Internet research: ethical guidelines 3.0. Retrieved from: . March 2021 https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf

- GDPR, General Data Protection Regulation (2021) General data protection regulation. Retrieved from: . November 2021 https://gdpr-info.eu/

- Hama Kareem JA, Rashid WN, Abdulla DF, Mahmood OK (2016) Social media and consumer awareness toward manufactured food. Cogent Bus Manag 3(1):1266786

- Hawkins LK, Farrow C, Thomas JM (2020) Do perceived norms of social media users’ eating habits and preferences predict our own food consumption and BMI? Appetite 149:104611

- Beaudoin CE, Hong T (2021) Emotions in the time of coronavirus: antecedents of digital and social media use among Millennials. Comput Hum Behav 123:106876

- Jackson M, Brennan L, Parker L (2021) The public health community’s use of social media for policy advocacy: a scoping review and suggestions to advance the field. Public Health 198:146–155

- Ferdenzi C, Delplanque S, Barbosa P, Court K, Guinard JX, Guo T et al (2013) Affective semantic space of scents. Towards a universal scale to measure self-reported odor-related feelings. Food Qual Prefer 30(2):128–138

- Vrontis D, Makrides A, Christofi M, Thrassou A (2020) Social media influencer marketing: a systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. Int J Consum Stud 00:1–28

- Tuikka AM, Chau N, Kimppa KK (2017) Ethical questions related to using netnography as research method. ORBIT J 1(2):1–11

- Kozinets R (1998) On netnography: initial reflections on consumer research investigations of cyberculture. Adv Consum Res 26:366–371

- Valentin D, Gomez-Corona C (2018) Using ethnography in consumer research. In: Ares G, Varela P (eds) Methods in consumer research. New approaches to classic methods, vol 1. Woodhead Publishing, UK

- Spiro ES (2016) Research opportunities at the intersection of social media and survey data. Curr Opin Psychol 9:67–71

- Thanh TV, Kirova V (2018) Wine tourism experience: a netnography study. J Bus Res 83:30–37

- Mkono M, Markwell K, Wilson E (2013) Applying Quan and Wang’s structural model of the tourist experience: a Zimbabwean netnography of food tourism. Tour Manag Perspect 5:68–74

- Irwansyah I, Triputra P (2016) Indonesia gastronomy brand: Netnography on virtual culinary community. Soc Sci 11(19):4585–4588

- Ang L (2011) Community relationship management and social media. J Database Mark Cust Strategy Manag 18(1):31–38

- Dessart L (2017) Social media engagement: a model of antecedents and relational outcomes. J Mark Manag 33(5–6):375–399

- Frants VI, Shapiro J, Taksa I, Voiskunskii VG (1999) Boolean search: current state and perspectives. J Am Soc Inf Sci 50(1):86–95

- Aliyu MB (2017) Efficiency of Boolean search strings for information retrieval. Am J Eng Res 6(11):216–222

- Reinert M (1990) Alceste une méthodologie d’analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurelia De Gerard De Nerval. Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 26(1):24–54

- Vidal L, Ares G, Machín L, Jaeger SR (2015) Using Twitter data for food-related consumer research: a case study on “what people say when tweeting about different eating situations”. Food Qual Prefer 45:58–69

- Laguna L, Fiszman S, Puerta P, Chaya C, Tárrega A (2020) The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on food priorities. Results from a preliminary study using social media and an online survey with Spanish consumers. Food Qual Prefer 86:104028

- Kuttschreuter M, Rutsaert P, Hilverda F, Regan Á, Barnett J, Verbeke W (2014) Seeking information about food-related risks: the contribution of social media. Food Qual Prefer 37:10–18

- Firmenich SA (2021) COVID-19 consumer behavior survey: wave 3

- Schmoyer JR, Brain J, Koza E (2021) Never average a crisis Better understanding of COVID 19’s impact on food drink behaviors through emotional clustering. In: Poster presented at 14th pangborn sensory science symposium, online, 9–12 August 2021

- Adams MJ, Umbach PD (2012) Nonresponse and online student evaluations of teaching: understanding the influence of salience, fatigue, and academic environments. Res High Educ 53(5):576–591

- DeMaio TJ (1984) Social desirability and survey. Surv Subj Phenom 2:257

- Huang HM (2006) Do print and Web surveys provide the same results? Comput Hum Behav 22(3):334–350

Advertisement

Customer engagement in social media: a framework and meta-analysis

- Review Paper

- Published: 27 May 2020

- Volume 48 , pages 1211–1228, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Fernando de Oliveira Santini 1 ,

- Wagner Junior Ladeira 1 ,

- Diego Costa Pinto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4418-9450 2 ,

- Márcia Maurer Herter 3 ,

- Claudio Hoffmann Sampaio 4 &

- Barry J. Babin 5

36k Accesses

230 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

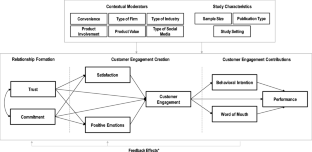

This research examines customer engagement in social media (CESM) using a meta-analytic model of 814 effect sizes across 97 studies involving 161,059 respondents. Findings reveal that customer engagement is driven by satisfaction, positive emotions, and trust, but not by commitment. Satisfaction is a stronger predictor of customer engagement in high (vs. low) convenience, B2B (vs. B2C), and Twitter (vs. Facebook and Blogs). Twitter appears twice as likely as other social media platforms to improve customer engagement via satisfaction and positive emotions. Customer engagement is also found to have substantial value for companies, directly impacting firm performance, behavioral intention, and word-of-mouth. Moreover, hedonic consumption yields nearly three times stronger customer engagement to firm performance effects vis-à-vis utilitarian consumption. However, contrary to conventional managerial wisdom, word-of-mouth does not improve firm performance nor does it mediate customer engagement effects on firm performance. Contributions to customer engagement theory, including an embellishment of the customer engagement mechanics definition, and practical implications for managers are discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Customer engagement and performance in social media: a managerial perspective

The Companies We Keep: Social Networks, Customer Service, and the Coming Corporate Challenges

Customer engagement: the construct, antecedents, and consequences, explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

We did examine an alternative model allowing direct effects of trust and commitment on firm performance, behavioral intention and WOM. The chi-square difference between the CESM model and the alternative is 19.9 with 4 df ( p = .00052). The CFI suggests a slight improvement in fit to 0.98 versus 0.97. The improvement in fit is due largely due to a positive, significant, and nontrivial trust-performance relationship. More importantly, the addition of the direct paths does not affect the parameter estimates to any large degree as the correlation between the CESM estimates and the alternative model is r = 0.922. The parameter stability further provides evidence of a lack of bias due to interpretational confounding.

Aggarwal, R., Gopal, R., Gupta, A., & Singh, H. (2012). Putting money where the mouths are: The relation between venture financing and electronic word-of-mouth. Information Systems Research , 23 (3-part-2), 976-992.

Agrawal, N., Menon, G., & Aaker, J. L. (2007). Getting emotional about health. Journal of Marketing Research, 44 (1), 100–113.

Article Google Scholar

Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U. M., & Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. Journal of Marketing, 69 (3), 19–34.

Ashley, C., & Tuten, T. (2015). Creative strategies in social media marketing: An exploratory study of branded social content and consumer engagement. Psychology & Marketing, 32 (1), 15–27.

Babić-Rosario, A., Sotgiu, F., De Valck, K., & Bijmolt, T. H. (2016). The effect of electronic word of mouth on sales: A meta-analytic review of platform, product, and metric factors. Journal of Marketing Research, 53 (3), 297–318.

Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20 (4), 644–656.

Badrinarayanan, V. A., Sierra, J. J., & Martin, K. M. (2015). A dual identification framework of online multiplayer video games: The case of massively multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPGs). Journal of Business Research, 68 (5), 1045–1052.

Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M., & Nyer, P. U. (1999). The role of emotions in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27 , 184–206.

Baldus, B. J., Voorhees, C., & Calantone, R. (2015). Online brand community engagement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research, 68 (5), 978–985.

Beckers, S. F. M., van Doorn, J., & Verhoef, P. C. (2018). Good, better, engaged? The effect of company-initiated customer engagement behavior on shareholder value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (3), 366–383.

Bijmolt, T. H. A., Leeflang, P. S. H., Block, F., Eisenbeiss, M., Hardie, B. G. S., Lemmens, A., & Saffert, P. (2010). Analytics for customer engagement. Journal of Service Research, 13 (3), 341–356.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2019). Introduction to meta-analysis . UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Google Scholar

Bowden, J. L. H. (2009a). The process of customer engagement: A conceptual framework. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 17 (1), 63–74.

Bowden, J. L. H. (2009b). Customer engagement: A framework for assessing customer-brand relationships: The case of the restaurant industry. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18 (6), 574–596.

Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Jurić, B., & Ilić, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research, 14 (3), 252–271.

Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A., Juric, B., & Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Business Research, 66 (1), 105–114.

Brown, L. G. (1990). Convenience in services marketing. Journal of Services Marketing, 4 (1), 53–59.

Calder, B. J., Malthouse, E. C., & Schaedel, U. (2009). An experimental study of the relationship between online engagement and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23 (4), 321–331.

Cheung, M. W. (2015). Meta analysis: A structural equation modeling approach . Wiley.

Cheung, M. W., & Chan, W. (2005). Meta-analytic structural equation modeling: A two-stage approach. Psychological Methods, 10 (1), 40–64.

Cheung, C. M., Shen, X. L., Lee, Z. W., & Chan, T. K. (2015). Promoting sales of online games through customer engagement. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 14 (4), 241–250.

Chu, S. C., & Kim, Y. (2011). Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. International Journal of Advertising, 30 (1), 47–75.

Claffey, E., & Brady, M. (2017). Examining consumers’ motivations to engage in firm-hosted virtual communities. Psychology & Marketing, 34 (4), 356–375.

Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2015). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24 (1), 28–42.

Dutot, V., & Mosconi, E. (2016). Understanding factors of disengagement within a virtual community: An exploratory study. Journal of Decision Systems, 25 (3), 227–243.

Eisend, M. (2017). The third-person effect in advertising: A meta-analysis. Journal of Advertising, 46 (3), 377–394.

Fischer, E., & Reuber, A. R. (2011). Social interaction via new social media:(how) can interactions on twitter affect effectual thinking and behavior? Journal of Business Venturing, 26 (1), 1–18.

Forbes. (2015). How To Sell Intangibles . Retrieved July 1 st , 2019 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/larrymyler/2015/08/15/how-to-sell-intangibles/#572772477a0a

Forbes. (2018a). Want to Improve Your Social Media Strategy? Avoid These 14 Faux Pas . Retrieved July 1 st , 2019 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2018/04/27/want-to-improve-your-social-media-strategy-avoid-these-14-faux-pas/#4178216574d6

Forbes. (2018b). Social Media is Increasing Brand Engagement and Sales . Retrieved July 1 st , 2019 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/tjmccue/2018/06/26/social-media-is-increasing-brand-engagement-and-sales/#35a844717cb3

Forbes. (2018c). Facebook Engagement Sharply Drops 50% Over Last 18 Months . Retrieved July 1 st , 2019 https://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanerskine/2018/08/13/study-facebook-engagement-sharply-drops-50-over-last-18-months/#58a6828b94e8

Forbes (2019). Creating a Marketing Budget for 2020. Retrieved April 1st, 2020 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2019/12/19/creating-a-marketing-budget-for-2020/

Forbes (2020a). Why 2020 is a Critical Global Tipping Point for Social Media . Retrieved April 1st, 2020 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2020/02/18/why-2020-is-a-critical-global-tipping-point-for-social-media/

Forbes (2020b). Top Ten Results from the February 2020 CMO Survey . Retrieved April 1st, 2020 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinemoorman/2020/02/26/top-ten-results-from-the-february-2020-cmo-survey/

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J. B. E., & Kumar, N. (1999). A meta-analysis of satisfaction in marketing channel relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 36 (2), 223–238.

Geyskens, I., Krishnan, R., Steenkamp, J. B. E., & Cunha, P. V. (2009). A review and evaluation of meta-analysis practices in management research. Journal of Management, 35 (2), 393–419.

Grewal, D., Puccenelli, N., & Monroe, K. B. (2018). Meta-analysis: Integrating accumulated knowledge. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 , 9–30.

Gummerus, J., Liljander, V., Weman, E., & Pihlström, M. (2012). Customer engagement in a Facebook brand community. Management Research Review, 35 (9), 857–877.

Gustafsson, A., Johnson, M. D., & Roos, I. (2005). The effects of customer satisfaction, relationship commitment dimensions, and triggers on customer retention. Journal of Marketing, 69 (4), 210–218.

Hagtvedt, H., & Patrick, V. M. (2009). The broad embrace of luxury: Hedonic potential as a driver of brand extendibility. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19 (4), 608–618.

Hair Jr., J. F., Babin, B. J., & Krey, N. (2017). Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the journal of advertising: Review and recommendations. Journal of Advertising, 46 (1), 163–177.

Halaszovich, T., & Nel, J. (2017). Customer–brand engagement and Facebook fan-page “like”-intention. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 26 (2), 120–134.

Han, D., Duhachek, A., & Agrawal, N. (2014). Emotions shape decisions through construal level: The case of guilt and shame. Journal of Consumer Research, 41 (4), 1047–1064.

Harmeling, C. M., Moffett, J. W., Arnold, M. J., & Carlson, B. D. (2017). Toward a theory of customer engagement marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (3), 312–335.

Harvard Business Review. (2018). The Basic Social Media Mistakes Companies Still Make . Retrieved July 1 st , 2018 from https://hbr.org/2018/01/the-basic-social-media-mistakes-companies-still-make

Harvard Business Review. (2019). Using Social Media to Connect With Your Most Loyal Customers . Retrieved January 15 th , 2020 from https://hbr.org/2019/12/using-social-media-to-connect-with-your-most-loyal-customers

Harvard Business Review. (2020). Four Questions to Boost Your Social Media Marketing . Retrieved January 15 th , 2020 from https://hbr.org/2020/01/4-questions-to-boost-your-social-media-marketing

Hauk, N., Hüffmeier, J., & Krumm, S. (2018). Ready to be a silver surfer? A meta-analysis on the relationship between chronological age and technology acceptance. Computers in Human Behavior, 84 , 304–319.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis . Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Qwinner, P. K., Walsh, G., & Gremler, D. D. (2004). Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18 , 38–52.

Higgins, E. T., & Scholer, A. A. (2009). Engaging the consumer: The science and art of the value creation process. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19 (2), 100–114.

Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46 , 92–101.

Hollebeek, L. (2011). Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 19 (7), 555–573.

Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28 (2), 149–165.

Hollebeek, L. D., Srivastava, R. K., & Chen, T. (2016). SD logic–informed customer engagement: Integrative framework, revised fundamental propositions, and application to CRM. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47 , 1–25.

Hopp, T., & Gallicano, T. D. (2016). Development and test of a multidimensional scale of blog engagement. Journal of Public Relations Research, 28 (3–4), 127–145.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings . SAGE Publications.

Jak, S. (2015). Meta-analytic structural equation modelling . Dordrecht, Neth: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Junco, R., Elavsky, C. M., & Heiberger, G. (2013). Putting twitter to the test: Assessing outcomes for student collaboration, engagement and success. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44 (2), 273–287.

Kim, Y., & Peterson, R. A. (2017). A meta-analysis of online trust relationships in E-commerce. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 38 , 44–54.

Kumar, V. (2013). Profitable customer engagement - concept . Metrics and Strategies: SAGE Publications.

Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2015). Measuring the benefits of employee engagement. MIT Sloan Management Review, 56 (4), 67.

Kumar, V., Aksoy, L., Donkers, B., Venkatesan, R., Wiesel, T., & Tillmanns, S. (2010). Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. Journal of Service Research, 13 (3), 297–310.

Kumar, V., Rajan, B., Gupta, S., & Pozza, I. D. (2019). Customer engagement in service. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47 (1), 138–160.

Labrecque, L. I. (2014). Fostering consumer–brand relationships in social media environments: The role of Parasocial interaction. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28 , 134–148.

Labroo, A., & Patrick, V. M. (2009). Why happiness helps you see the big picture. Journal of Consumer Research, 35 (5), 800–809.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis (Vol. 49). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Mano, H., & Oliver, R. L. (1993). Assessing the dimensionality and structure of the consumption experience: Evaluation, feeling, and satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 20 (3), 451–466.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6 (7), e1000097.

Mollen, A., & Wilson, H. (2010). Engagement, telepresence, and interactivity in online consumer experience: Reconciling scholastic and managerial perspectives. Journal of Business Research, 63 (9), 919–925.

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., & Zaltman, G. (1993). Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. Journal of Marketing, 57 (1), 81–101.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58 (3), 20–38.

Morgan, N. A., & Rego, L. L. (2006). The value of different customer satisfaction and loyalty metrics in predicting business performance. Marketing Science, 25 (5), 426–439.

Neale, M. C., Hunter, M. D., Pritikin, J. N., Zahery, M., Brick, T. R., Kirkpatrick, R. M., Estabrook, R., Bates, T. C., Maes, H. H., & Boker, S. M. (2016). OpenMx 2.0: Extended structural equation and statistical modeling. Psychometrika, 81 (2), 535–549.

Netbase Social Analytics. (2020). Social Media Rankings by Industry. Retrieved January 15 th , 2020 from https://www.netbase.com/social-media-rankings/

Obilo, O. O., Chefor, E., & Saleh, A. (2020). Revisiting the consumer brand engagement concept. Journal of Business Research, In Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.023 .

Pansari, A., & Kumar, V. (2017). Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (3), 294–311.

Park, C. W., & MacInnis, D. J. (2006). What's in and what's out: Questions on the boundaries of the attitude construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 33 (1), 16–18.

Paruthi, M., & Kaur, H. (2017). Scale development and validation for measuring online engagement. Journal of Internet Commerce, 16 (2), 127–147.

Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 (1), 175–181.

Rietveld, R., van Dolen, W., Mazloom, M., & Worring, M. (2020). What you feel, is what you like influence of message appeals on customer engagement on Instagram. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 49 , 20–53.

Rosenblad, A. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis by Michael Borenstein, Larry V. Hedges, Julian PT Higgins. Hannah R. Rothstein. International Statistical Review, 77 (3), 478–479.

Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86 (3), 638–642.

Rosenthal, R., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2001). Meta-analysis: Recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annual Review of Psychology, 52 (1), 59–82.

Rust, R. T., & Cooil, B. (1994). Reliability measures for qualitative data: Theory and implications. Journal of Marketing Research, 31 (1), 1–14.

Santini, F., Ladeira, W. J., Sampaio, C. H., & Pinto, D. C. (2018). The brand experience extended model: A meta-analysis. Journal of Brand Management, 25 , 519–535.

See-To, E. W., & Ho, K. K. (2014). Value co-creation and purchase intention in social network sites: The role of electronic word-of-mouth and trust–a theoretical analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 31 , 182–189.

Simon, F., & Tossan, V. (2018). Does brand-consumer social sharing matter? A relational framework of customer engagement to brand-hosted social media. Journal of Business Research, 85 , 175–184.

Smith, J. B., & Colgate, M. (2007). Customer value creation: A practical framework. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 15 (1), 7–23.

Sprott, D., Czellar, S., & Spangenberg, E. (2009). The importance of a general measure of brand engagement on market behavior: Development and validation of a scale. Journal of Marketing Research, 46 (1), 92–104.

Thomson, M., MacInnis, D. J., & Whan Park, C. (2005). The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15 (1), 77–91.

Trusov, M., Bucklin, R. E., & Pauwels, K. (2009). Effects of word-of-mouth versus traditional marketing: Findings from an internet social networking site. Journal of Marketing, 73 (5), 90–102.

Tsai, H. T., Huang, H. C., & Chiu, Y. L. (2012). Brand community participation in Taiwan: Examining the roles of individual-, group-, and relationship-level antecedents. Journal of Business Research, 65 (5), 676–684.

Van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of Service Research, 13 (3), 253–266.

Van Lange, P. A. M., Rusbult, C. E., Drigotas, S. M., & Arriaga, X. B. (1997). Willingness to sacrifice in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72 (6), 1373–1395.

Venkatesan, R. (2017). Executing on a customer engagement strategy. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 45 (3), 289–293.

Verhoef, P. C., Franses, P. H., & Hoekstra, J. C. (2002). The effect of relational constructs on customer referrals and number of services purchased from a multiservice provider: Does age of relationship matter? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30 (3), 202–216.

Verhoef, P. C., Reinartz, W. J., & Krafft, M. (2010). Customer engagement as a new perspective in customer management. Journal of Service Research, 13 (3), 247–252.

Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36 , 1–48.

Villanueva, J., Yoo, S., & Hanssens, D. M. (2008). The impact of marketing-induced versus word-of-mouth customer acquisition on customer equity growth. Journal of Marketing Research, 45 (1), 48–59.

Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., & Morgan, R. M. (2012). Customer engagement: Exploring customer relationships beyond purchase. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 20 (2), 122–146.

Wang, Z., & Kim, H. G. (2017). Can social media marketing improve customer relationship capabilities and firm performance? Dynamic capability perspective. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 39 , 15–26.

Wong, H. Y., & Merrilees, B. (2015). An empirical study of the antecedents and consequences of brand engagement. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33 (4), 575–591.

Yadav, M. S., & Pavlou, P. A. (2014). Marketing in computer-mediated environments: Research synthesis and new directions. Journal of Marketing, 78 (1), 20–40.

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12 (3), 341–352.

Zboja, J. J., & Voorhees, C. M. (2006). The impact of brand trust and satisfaction on retailer repurchase intentions. Journal of Services Marketing, 20 (6), 381–390.

Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). Problems and strategies in services marketing. Journal of Marketing, 49 (2), 33–46.

Zenith Media (2020). Social media overtakes print to become the third-largest advertising channel . Retrieved April 1st, 2020 from https://www.zenithmedia.com/social-media-overtakes-print-to-become-the-third-largest-advertising-channel/

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos (UNISINOS), Av. Unisinos, São Leopoldo, RS, 950, Brazil

Fernando de Oliveira Santini & Wagner Junior Ladeira

NOVA Information Management School|, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, Campus de Campolide, Lisbon, Portugal

Diego Costa Pinto

Universidade Europeia, Quinta do Bom Nome, Estr. Correia, 53, Lisbon, Portugal

Márcia Maurer Herter

Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUC/RS), Av. Ipiranga, Porto Alegre, RS, 6681, Brazil

Claudio Hoffmann Sampaio

University of Mississipi, P.O. Box 1848, University, MS, 38677, USA

Barry J. Babin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Diego Costa Pinto .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

John Hulland and Mark Houston served as editors for this article.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 59 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

de Oliveira Santini, F., Ladeira, W.J., Pinto, D. et al. Customer engagement in social media: a framework and meta-analysis. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 48 , 1211–1228 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00731-5

Download citation

Received : 17 August 2018

Accepted : 28 April 2020

Published : 27 May 2020

Issue Date : November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00731-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Customer engagement

- Firm performance

- Meta-analysis

- Online consumer behavior

- Social media

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Send us an email

6 ways social media impacts consumer behavior

Written by by Jamia Kenan

Published on November 30, 2023

Reading time 8 minutes

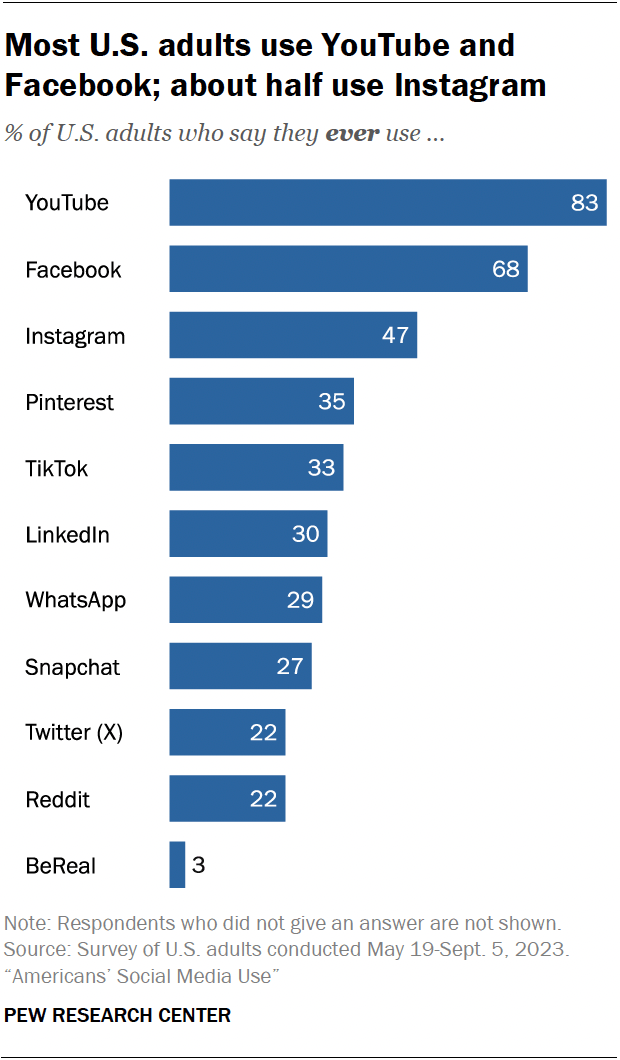

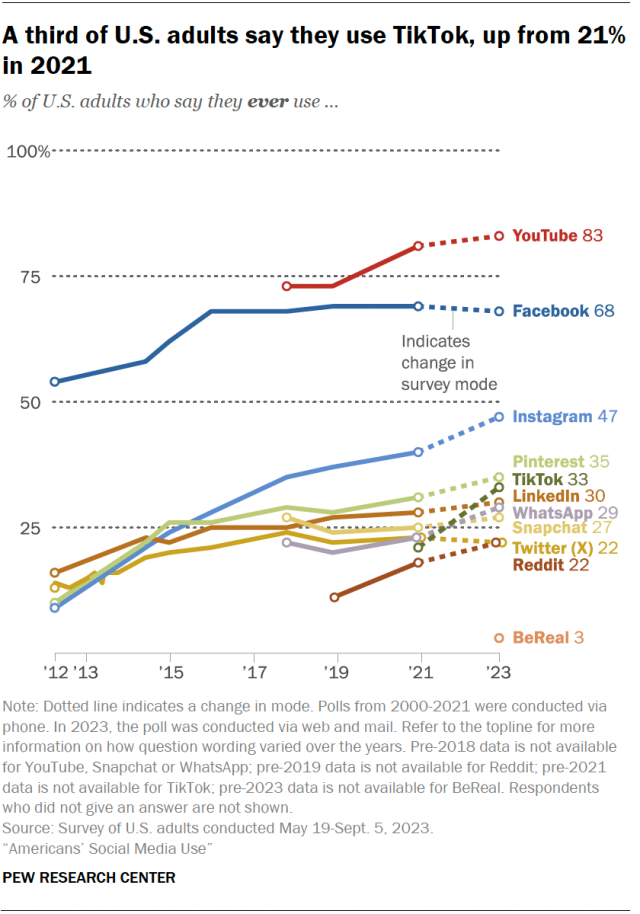

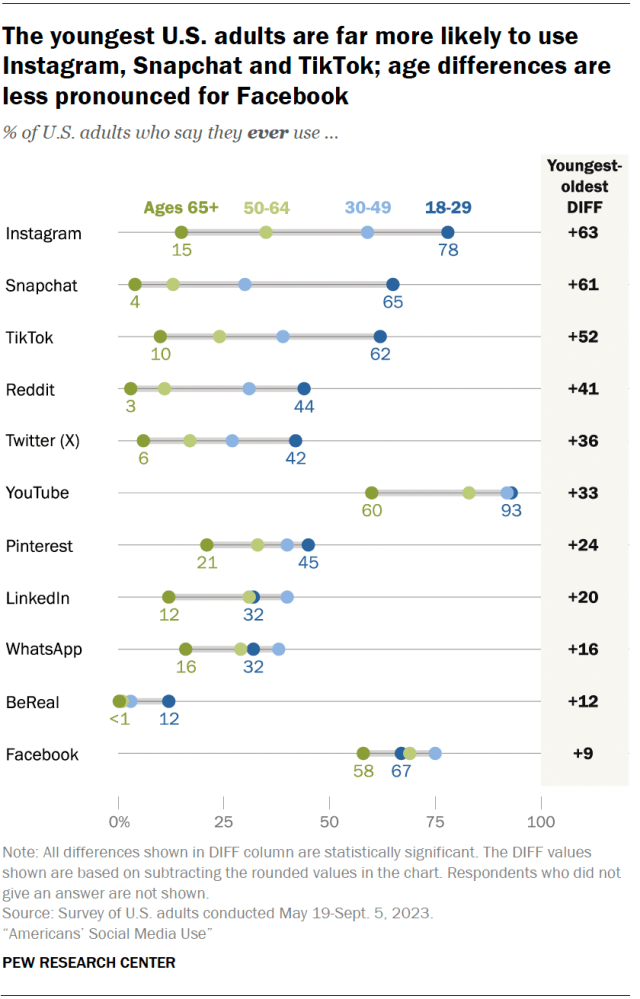

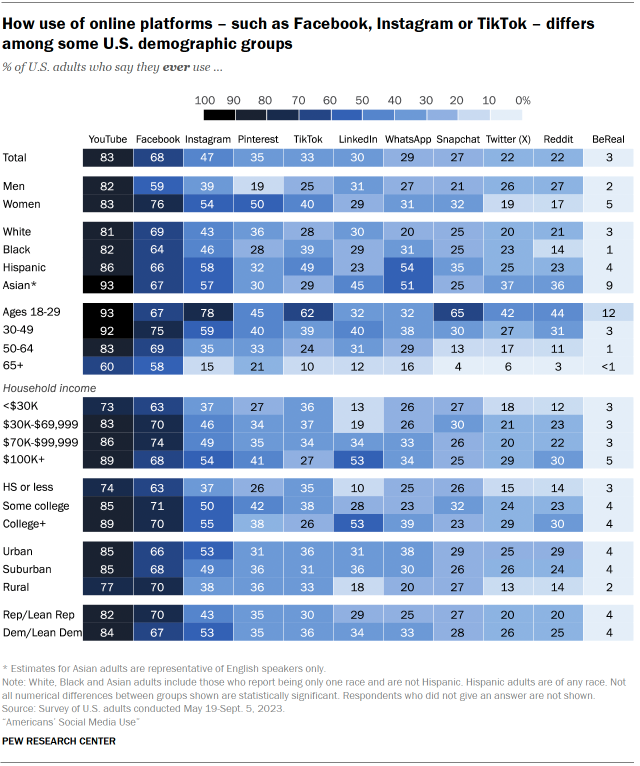

Whether consumers are laughing at their favorite brand’s infotainment content, buying products through live shopping or tuning into a try-on haul, social media is a daily staple in their lives. In The Sprout Social Index™ , we found 54% of consumers say their social media usage has been higher over the last two years than the previous two years.

With more people flocking to networks than ever before, social media and consumer behavior have evolved in lockstep, so understanding how to reach your target audience remains a necessity.

In this article, we’ll discuss the top six ways social media influences consumer behavior and what each means for your brand’s social strategy.

1. Consumers buy directly from social

Index data shows the top reason consumers follow brands on social media is to stay informed about new products/services, followed by getting access to exclusive deals and promotions.

But why is social commerce so popular? One reason is that it meets consumers where they already are. According to data from McKinsey , the majority of consumers use at least three channels for each purchase journey. For many, checking Facebook, Instagram or TikTok daily—whether they’re casually scrolling or searching for new products—has become as routine as brushing their teeth.

Networks continue to experiment with and formalize ecommerce capabilities to bring convenience to consumers and present brands with new revenue streams. For example, TikTok Shop launched in September 2023, enabling users to find and shop for items even more easily.

US annual social commerce sales per buyer are projected to double from $628 million to $1.224 billion in 2027, based on a forecast from Insider Intelligence.

How you can use this insight

Social commerce makes it infinitely easier for brands to deliver the seamless purchase experience buyers want. You can turn a casual scroller into a new customer in a couple of clicks. For example, if you’re a retail business and a holiday is coming up, you can create a shoppable Facebook ad or offer a limited time offer using Instagram Shops for your seasonal product lines.

If you’re not already, look into what social commerce functionality is available on the channels your audience spends the most time on. From TikTok to YouTube livestream shopping , there is a growing number of ways to connect with ready-to-buy consumers.

If you’re a Sprout user, take advantage of our integrations with Shopify and Facebook Shops by connecting your product catalogs with our platform—you can quickly add product links in your outbound posts and customer replies.

2. Consumers expect two-way engagement with brands

Social media adds another dimension to the brand-customer relationship. A brand is no longer a remote, faceless entity that we only learn about in publications, press releases or Google searches. Looking at a brand’s social networks helps you gauge their values, relevant news and offerings, and how they relate to their audience.

Social lets consumers engage and interact with businesses in a multitude of ways, from liking posts and following their accounts to sharing brand-related content, shouting out brand love or asking product questions. And of course, social shopping makes conversions faster.

Don’t be too shy to engage with your audience, jump on relevant trends, ask questions or run polls and Q&As. And don’t forget to respond to direct messages, comments and @-mentions.

The Index found 51% of consumers said the most memorable brands on social respond to customers. Across all age groups, consumers want to know they’re being heard.

Brand authenticity will drive a customer to choose you over a competitor—and stick with you. This means upholding your organization’s claimed values, listening to your audience, discussing what matters to them, anticipating their needs and delivering on the promises you make.

Engagement happens perpetually across multiple channels and formats. With a tool like Sprout’s Smart Inbox, you can set up rules to automatically tag and categorize inbound messages so you never miss an opportunity to engage.

Analyze trends and patterns across these conversations to gain a deeper understanding of your customers. What’s delightful and what’s frustrating them? What are they praising, and what are they criticizing? What are they sharing about your brand and your competitors with their own audiences?

Of course, brands should address complaints and negative inbound messages, but tools like Sprout can help brands get the answers to these questions so they can proactively engage versus reactively. For example, with social listening, you can uncover opportunities to surprise and delight your customers.

Elicit and listen to feedback and share it with your organization. Channel this feedback to your colleagues across the business from sales and marketing to product and operations to deliver more tailored customer experiences in the future.

3. Consumers turn to social media for customer service

The evolution of social media and consumer behavior has transformed customer service interactions. Before social, consumers could expect to interact with a brand by calling, emailing or visiting locations in person—complete with the infamous wait times to talk to a representative. Today, social is consumers’ preferred choice for sharing feedback and reaching out with a customer support issue or question.

The days of long telephone hold times punctuated by elevator music are dwindling. Consumers with a product question or order issue are much more inclined to reach out via a brand’s Facebook page, X (formerly known as Twitter) @-mention or Instagram direct message. But social media moves fast, which means customers expect faster answers.

Index data shows customer service isn’t just about responding quickly either. Although 76% of consumers value how quickly a brand can respond to their needs, 70% expect a company to provide personalized responses to customer service needs.

Regardless of whether it’s a busy season, customer service teams may already be spread thin or lack resources, which can result in missed messages, slower responses and suboptimal replies. Prevent frustration, reduce delays and improve communication by evolving your approach to social customer service .

Social customer care starts even before a customer reaches out to you. It means getting a clear understanding of what your customer wants from you, reducing room for error and building long-term relationships with your audience.

How can you create and maintain a social customer care strategy? Start by making it easy for customers to find you. Include relevant contact info on your organization’s social media profiles and bios. Make sure you’re monitoring Meta Messenger and direct messages on X, Instagram or TikTok (or consider recruiting a chatbot’s help) if that’s the communication channel your customers flock to most.

If your business has dedicated teams for social media and customer care, collaboration across departments is a must. Implementing a social customer relationship management (CRM ) tool gives you a single source of truth to provide customer service while getting a more holistic view of customer behavior.

Another critical step is proactive message management. If a customer feels like they’re being ignored, they’ll move on to a more attentive competitor. Do you have ways to centralize inbound support messages across different social networks? Can your social customer care agents easily access important client information via CRM or help desk integrations ? Do you have an efficient process for approving replies to customer questions on social?

If you answered “no” to any of these, don’t be afraid to turn to tools like Sprout to help your team work smarter and build stronger customer relationships .

4. Consumers demand authenticity in the age of AI

Index data shows authentic, non-promotional posts are ranked as the number one content type consumers don’t see enough of from brands on social. However, with limited bandwidth and resources, it can be difficult to consistently produce authentic, creative content at scale. Enter: artificial intelligence (AI).

And although 81% of marketers say AI has already had a positive impact on their work, consumers aren’t as eager to jump onto this technology wave. Over a third (42%) of consumers say they are slightly or very apprehensive about the use of AI in social media interactions.

So how does this impact your brand’s content strategy? Consider pulling back on trendjacking and prioritizing original content that’s true to your brand.

Shaping genuine connections and building community can’t be replicated by machines alone, but adding that golden human touch requires time. Leverage AI to handle manual, time-consuming tasks like social media reporting. If you use AI to create spreadsheets and reports, marketers can focus their energy and efforts into developing more impactful content and engagement strategies. Research and identify where to incorporate AI across your teams ’ tasks and workflows.

5. Consumers want more transparency and less performative activism

A few years ago, consumers wanted brands to take a stand on important causes. The latest Index shows only 25% of consumers think brands must speak out on causes and news relevant to their values to be memorable on social.

Consumers want brands to share more about their business values and practices, and how their products are made/sourced—but they aren’t necessarily looking for them to “take a stand” on larger issues. Due to the rise of performative activism, some efforts read as disingenuous and inauthentic. In other words, consumers don’t just want brands to talk about their values, they must walk the walk too.

This slight shift in consumer behavior is an opportunity for social teams to collaborate with colleagues beyond marketing. Work to develop messaging around your company’s supply chain, operations, labor practices and culture that will resonate on social. Consider featuring more employees in your social content such as a behind-the-scenes series, or connect with C-suite executives to refine their social presence and thought leadership on platforms like LinkedIn. And to amplify those efforts even more, implement employee advocacy into your content strategy.

6. Consumers are heavily influenced by social media reviews

Social media is a living document for social proof —which is increasingly a make-or-break factor for buying decisions.

Data from the Yale Center for Customer Insights shows almost 90% of`consumers trust online reviews as much as they trust personal recommendations. And half of consumers 18-54 look for online reviews before deciding to visit a local business.

Even the most dazzling, high-budget television ads can’t always deliver what social media offers for free: authenticity. Consumers take to channels like X and review hubs like Yelp and Google Reviews to praise, champion and criticize different products and businesses. Buyers are more likely to trust this unfiltered peer feedback from people who have already tried a product or engaged with a brand.

From a brand perspective, reviews are key for audience growth and reputation management . Every review post, comment and @-mention is either an opportunity to reflect on ways your business can improve—or a glowing testimonial worth sharing more broadly with your audience.

Online review management is tricky, but it’s a must for maintaining a positive reputation. It’s hard to distill review data from disparate sources into a quantifiable metric. With a social listening tool like Sprout’s, you can easily analyze the sentiment of messages that mention your brand so you can dig into positive, neutral and negative feedback.

Sprout’s review management capabilities ensure you never miss a message (or a chance to engage) by centralizing reviews from Facebook, Glassdoor, Google My Business, TripAdvisor, Yelp, Google Play Store and Apple App Store in one place.

You can also conduct sentiment analysis in Sprout’s Smart Inbox and Reviews feed. Sprout will automatically assign sentiment to messages in your Smart Inbox and Reviews, but you can dig in further by adding filters and custom views.

Social media and consumer behavior: An ongoing transformation

Social media leveled the playing field between buyers and brands. Consumers can learn about and engage with brands more easily, and vice versa. Brands can listen to what matters to their audience at the most individual level and help solve problems faster.

Thanks to social, consumers expect much more from the businesses they support. With the right tools, organizations of any size can rise to the challenge.

Looking to learn more about social media and consumer behavior and the right next steps? Learn more data insights in The Sprout Social Index™ .

- Community Management

- Social Media Engagement

How to craft an effective social media moderation plan in 2024

- Social Media Strategy

7 strategies to boost your social media traffic

- Social Listening

Social mentions: How to protect your brand while nurturing community

- Customer Care

How to apply conversational marketing to your business

- Now on slide

Build and grow stronger relationships on social

Sprout Social helps you understand and reach your audience, engage your community and measure performance with the only all-in-one social media management platform built for connection.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 May 2024

Exploring the dynamics of consumer engagement in social media influencer marketing: from the self-determination theory perspective

- Chenyu Gu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6059-0573 1 &

- Qiuting Duan 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 587 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

3248 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Cultural and media studies

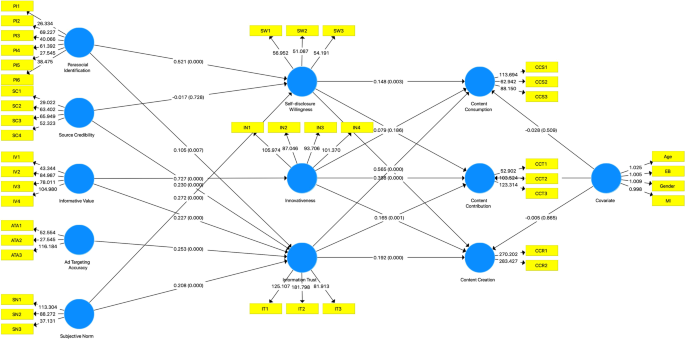

Influencer advertising has emerged as an integral part of social media marketing. Within this realm, consumer engagement is a critical indicator for gauging the impact of influencer advertisements, as it encompasses the proactive involvement of consumers in spreading advertisements and creating value. Therefore, investigating the mechanisms behind consumer engagement holds significant relevance for formulating effective influencer advertising strategies. The current study, grounded in self-determination theory and employing a stimulus-organism-response framework, constructs a general model to assess the impact of influencer factors, advertisement information, and social factors on consumer engagement. Analyzing data from 522 samples using structural equation modeling, the findings reveal: (1) Social media influencers are effective at generating initial online traffic but have limited influence on deeper levels of consumer engagement, cautioning advertisers against overestimating their impact; (2) The essence of higher-level engagement lies in the ad information factor, affirming that in the new media era, content remains ‘king’; (3) Interpersonal factors should also be given importance, as influencing the surrounding social groups of consumers is one of the effective ways to enhance the impact of advertising. Theoretically, current research broadens the scope of both social media and advertising effectiveness studies, forming a bridge between influencer marketing and consumer engagement. Practically, the findings offer macro-level strategic insights for influencer marketing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the effects of audience and strategies used by beauty vloggers on behavioural intention towards endorsed brands

COBRAs and virality: viral campaign values on consumer behaviour

Exploring the impact of beauty vloggers’ credible attributes, parasocial interaction, and trust on consumer purchase intention in influencer marketing

Introduction.

Recent studies have highlighted an escalating aversion among audiences towards traditional online ads, leading to a diminishing effectiveness of traditional online advertising methods (Lou et al., 2019 ). In an effort to overcome these challenges, an increasing number of brands are turning to influencers as their spokespersons for advertising. Utilizing influencers not only capitalizes on their significant influence over their fan base but also allows for the dissemination of advertising messages in a more native and organic manner. Consequently, influencer-endorsed advertising has become a pivotal component and a growing trend in social media advertising (Gräve & Bartsch, 2022 ). Although the topic of influencer-endorsed advertising has garnered increasing attention from scholars, the field is still in its infancy, offering ample opportunities for in-depth research and exploration (Barta et al., 2023 ).

Presently, social media influencers—individuals with substantial follower bases—have emerged as the new vanguard in advertising (Hudders & Lou, 2023 ). Their tweets and videos possess the remarkable potential to sway the purchasing decisions of thousands if not millions. This influence largely hinges on consumer engagement behaviors, implying that the impact of advertising can proliferate throughout a consumer’s entire social network (Abbasi et al., 2023 ). Consequently, exploring ways to enhance consumer engagement is of paramount theoretical and practical significance for advertising effectiveness research (Xiao et al., 2023 ). This necessitates researchers to delve deeper into the exploration of the stimulating factors and psychological mechanisms influencing consumer engagement behaviors (Vander Schee et al., 2020 ), which is the gap this study seeks to address.

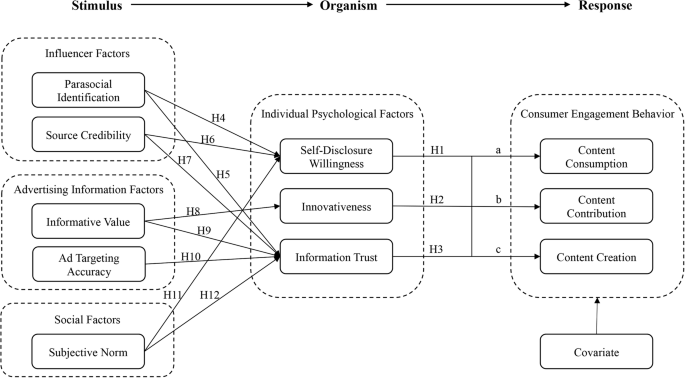

The Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework has been extensively applied in the study of consumer engagement behaviors (Tak & Gupta, 2021 ) and has been shown to integrate effectively with self-determination theory (Yang et al., 2019 ). Therefore, employing the S-O-R framework to investigate consumer engagement behaviors in the context of influencer advertising is considered a rational approach. The current study embarks on an in-depth analysis of the transformation process from three distinct dimensions. In the Stimulus (S) phase, we focus on how influencer factors, advertising message factors, and social influence factors act as external stimuli. This phase scrutinizes the external environment’s role in triggering consumer reactions. During the Organism (O) phase, the research explores the intrinsic psychological motivations affecting individual behavior as posited in self-determination theory. This includes the willingness for self-disclosure, the desire for innovation, and trust in advertising messages. The investigation in this phase aims to understand how these internal motivations shape consumer attitudes and perceptions in the context of influencer marketing. Finally, in the Response (R) phase, the study examines how these psychological factors influence consumer engagement behavior. This part of the research seeks to understand the transition from internal psychological states to actual consumer behavior, particularly how these states drive the consumers’ deep integration and interaction with the influencer content.

Despite the inherent limitations of cross-sectional analysis in capturing the full temporal dynamics of consumer engagement, this study seeks to unveil the dynamic interplay between consumers’ psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—and their varying engagement levels in social media influencer marketing, grounded in self-determination theory. Through this lens, by analyzing factors related to influencers, content, and social context, we aim to infer potential dynamic shifts in engagement behaviors as psychological needs evolve. This approach allows us to offer a snapshot of the complex, multi-dimensional nature of consumer engagement dynamics, providing valuable insights for both theoretical exploration and practical application in the constantly evolving domain of social media marketing. Moreover, the current study underscores the significance of adapting to the dynamic digital environment and highlights the evolving nature of consumer engagement in the realm of digital marketing.

Literature review

Stimulus-organism-response (s-o-r) model.

The Stimulus-Response (S-R) model, originating from behaviorist psychology and introduced by psychologist Watson ( 1917 ), posits that individual behaviors are directly induced by external environmental stimuli. However, this model overlooks internal personal factors, complicating the explanation of psychological states. Mehrabian and Russell ( 1974 ) expanded this by incorporating the individual’s cognitive component (organism) into the model, creating the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework. This model has become a crucial theoretical framework in consumer psychology as it interprets internal psychological cognitions as mediators between stimuli and responses. Integrating with psychological theories, the S-O-R model effectively analyzes and explains the significant impact of internal psychological factors on behavior (Koay et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ), and is extensively applied in investigating user behavior on social media platforms (Hewei & Youngsook, 2022 ). This study combines the S-O-R framework with self-determination theory to examine consumer engagement behaviors in the context of social media influencer advertising, a logic also supported by some studies (Yang et al., 2021 ).

Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory, proposed by Richard and Edward (2000), is a theoretical framework exploring human behavioral motivation and personality. The theory emphasizes motivational processes, positing that individual behaviors are developed based on factors satisfying their psychological needs. It suggests that individual behavioral tendencies are influenced by the needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy. Furthermore, self-determination theory, along with organic integration theory, indicates that individual behavioral tendencies are also affected by internal psychological motivations and external situational factors.

Self-determination theory has been validated by scholars in the study of online user behaviors. For example, Sweet applied the theory to the investigation of community building in online networks, analyzing knowledge-sharing behaviors among online community members (Sweet et al., 2020 ). Further literature review reveals the applicability of self-determination theory to consumer engagement behaviors, particularly in the context of influencer marketing advertisements. Firstly, self-determination theory is widely applied in studying the psychological motivations behind online behaviors, suggesting that the internal and external motivations outlined within the theory might also apply to exploring consumer behaviors in influencer marketing scenarios (Itani et al., 2022 ). Secondly, although research on consumer engagement in the social media influencer advertising context is still in its early stages, some studies have utilized SDT to explore behaviors such as information sharing and electronic word-of-mouth dissemination (Astuti & Hariyawan, 2021 ). These behaviors, which are part of the content contribution and creation dimensions of consumer engagement, may share similarities in the underlying psychological motivational mechanisms. Thus, this study will build upon these foundations to construct the Organism (O) component of the S-O-R model, integrating insights from SDT to further understand consumer engagement in influencer marketing.

Consumer engagement

Although scholars generally agree at a macro level to define consumer engagement as the creation of additional value by consumers or customers beyond purchasing products, the specific categorization of consumer engagement varies in different studies. For instance, Simon and Tossan interpret consumer engagement as a psychological willingness to interact with influencers (Simon & Tossan, 2018 ). However, such a broad definition lacks precision in describing various levels of engagement. Other scholars directly use tangible metrics on social media platforms, such as likes, saves, comments, and shares, to represent consumer engagement (Lee et al., 2018 ). While this quantitative approach is not flawed and can be highly effective in practical applications, it overlooks the content aspect of engagement, contradicting the “content is king” principle of advertising and marketing. We advocate for combining consumer engagement with the content aspect, as content engagement not only generates more traces of consumer online behavior (Oestreicher-Singer & Zalmanson, 2013 ) but, more importantly, content contribution and creation are central to social media advertising and marketing, going beyond mere content consumption (Qiu & Kumar, 2017 ). Meanwhile, we also need to emphasize that engagement is not a fixed state but a fluctuating process influenced by ongoing interactions between consumers and influencers, mediated by the evolving nature of social media platforms and the shifting sands of consumer preferences (Pradhan et al., 2023 ). Consumer engagement in digital environments undergoes continuous change, reflecting a journey rather than a destination (Viswanathan et al., 2017 ).

The current study adopts a widely accepted definition of consumer engagement from existing research, offering operational feasibility and aligning well with the research objectives of this paper. Consumer engagement behaviors in the context of this study encompass three dimensions: content consumption, content contribution, and content creation (Muntinga et al., 2011 ). These dimensions reflect a spectrum of digital engagement behaviors ranging from low to high levels (Schivinski et al., 2016 ). Specifically, content consumption on social media platforms represents a lower level of engagement, where consumers merely click and read the information but do not actively contribute or create user-generated content. Some studies consider this level of engagement as less significant for in-depth exploration because content consumption, compared to other forms, generates fewer visible traces of consumer behavior (Brodie et al., 2013 ). Even in a study by Qiu and Kumar, it was noted that the conversion rate of content consumption is low, contributing minimally to the success of social media marketing (Qiu & Kumar, 2017 ).

On the other hand, content contribution, especially content creation, is central to social media marketing. When consumers comment on influencer content or share information with their network nodes, it is termed content contribution, representing a medium level of online consumer engagement (Piehler et al., 2019 ). Furthermore, when consumers actively upload and post brand-related content on social media, this higher level of behavior is referred to as content creation. Content creation represents the highest level of consumer engagement (Cheung et al., 2021 ). Although medium and high levels of consumer engagement are more valuable for social media advertising and marketing, this exploratory study still retains the content consumption dimension of consumer engagement behaviors.

Theoretical framework

Internal organism factors: self-disclosure willingness, innovativeness, and information trust.

In existing research based on self-determination theory that focuses on online behavior, competence, relatedness, and autonomy are commonly considered as internal factors influencing users’ online behaviors. However, this approach sometimes strays from the context of online consumption. Therefore, in studies related to online consumption, scholars often use self-disclosure willingness as an overt representation of autonomy, innovativeness as a representation of competence, and trust as a representation of relatedness (Mahmood et al., 2019 ).

The use of these overt variables can be logically explained as follows: According to self-determination theory, individuals with a higher level of self-determination are more likely to adopt compensatory mechanisms to facilitate behavior compared to those with lower self-determination (Wehmeyer, 1999 ). Self-disclosure, a voluntary act of sharing personal information with others, is considered a key behavior in the development of interpersonal relationships. In social environments, self-disclosure can effectively alleviate stress and build social connections, while also seeking societal validation of personal ideas (Altman & Taylor, 1973 ). Social networks, as para-social entities, possess the interactive attributes of real societies and are likely to exhibit similar mechanisms. In consumer contexts, personal disclosures can include voluntary sharing of product interests, consumption experiences, and future purchase intentions (Robertshaw & Marr, 2006 ). While material incentives can prompt personal information disclosure, many consumers disclose personal information online voluntarily, which can be traced back to an intrinsic need for autonomy (Stutzman et al., 2011 ). Thus, in this study, we consider the self-disclosure willingness as a representation of high autonomy.

Innovativeness refers to an individual’s internal level of seeking novelty and represents their personality and tendency for novelty (Okazaki, 2009 ). Often used in consumer research, innovative consumers are inclined to try new technologies and possess an intrinsic motivation to use new products. Previous studies have shown that consumers with high innovativeness are more likely to search for information on new products and share their experiences and expertise with others, reflecting a recognition of their own competence (Kaushik & Rahman, 2014 ). Therefore, in consumer contexts, innovativeness is often regarded as the competence dimension within the intrinsic factors of self-determination (Wang et al., 2016 ), with external motivations like information novelty enhancing this intrinsic motivation (Lee et al., 2015 ).

Trust refers to an individual’s willingness to rely on the opinions of others they believe in. From a social psychological perspective, trust indicates the willingness to assume the risk of being harmed by another party (McAllister, 1995 ). Widely applied in social media contexts for relational marketing, information trust has been proven to positively influence the exchange and dissemination of consumer information, representing a close and advanced relationship between consumers and businesses, brands, or advertising endorsers (Steinhoff et al., 2019 ). Consumers who trust brands or social media influencers are more willing to share information without fear of exploitation (Pop et al., 2022 ), making trust a commonly used representation of the relatedness dimension in self-determination within consumer contexts.

Construction of the path from organism to response: self-determination internal factors and consumer engagement behavior

Following the logic outlined above, the current study represents the internal factors of self-determination theory through three variables: self-disclosure willingness, innovativeness, and information trust. Next, the study explores the association between these self-determination internal factors and consumer engagement behavior, thereby constructing the link between Organism (O) and Response (R).

Self-disclosure willingness and consumer engagement behavior

In the realm of social sciences, the concept of self-disclosure willingness has been thoroughly examined from diverse disciplinary perspectives, encompassing communication studies, sociology, and psychology. Viewing from the lens of social interaction dynamics, self-disclosure is acknowledged as a fundamental precondition for the initiation and development of online social relationships and interactive engagements (Luo & Hancock, 2020 ). It constitutes an indispensable component within the spectrum of interactive behaviors and the evolution of interpersonal connections. Voluntary self-disclosure is characterized by individuals divulging information about themselves, which typically remains unknown to others and is inaccessible through alternative sources. This concept aligns with the tenets of uncertainty reduction theory, which argues that during interpersonal engagements, individuals seek information about their counterparts as a means to mitigate uncertainties inherent in social interactions (Lee et al., 2008 ). Self-disclosure allows others to gain more personal information, thereby helping to reduce the uncertainty in interpersonal relationships. Such disclosure is voluntary rather than coerced, and this sharing of information can facilitate the development of relationships between individuals (Towner et al., 2022 ). Furthermore, individuals who actively engage in social media interactions (such as liking, sharing, and commenting on others’ content) often exhibit higher levels of self-disclosure (Chu et al., 2023 ); additional research indicates a positive correlation between self-disclosure and online engagement behaviors (Lee et al., 2023 ). Taking the context of the current study, the autonomous self-disclosure willingness can incline social media users to read advertising content more attentively and share information with others, and even create evaluative content. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypothesis:

H1a: The self-disclosure willingness is positively correlated with content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H1b: The self-disclosure willingness is positively correlated with content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H1c: The self-disclosure willingness is positively correlated with content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Innovativeness and consumer engagement behavior

Innovativeness represents an individual’s propensity to favor new technologies and the motivation to use new products, associated with the cognitive perception of one’s self-competence. Individuals with a need for self-competence recognition often exhibit higher innovativeness (Kelley & Alden, 2016 ). Existing research indicates that users with higher levels of innovativeness are more inclined to accept new product information and share their experiences and discoveries with others in their social networks (Yusuf & Busalim, 2018 ). Similarly, in the context of this study, individuals, as followers of influencers, signify an endorsement of the influencer. Driven by innovativeness, they may be more eager to actively receive information from influencers. If they find the information valuable, they are likely to share it and even engage in active content re-creation to meet their expectations of self-image. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H2a: The innovativeness of social media users is positively correlated with content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H2b: The innovativeness of social media users is positively correlated with content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H2c: The innovativeness of social media users is positively correlated with content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Information trust and consumer engagement

Trust refers to an individual’s willingness to rely on the statements and opinions of a target object (Moorman et al., 1993 ). Extensive research indicates that trust positively impacts information dissemination and content sharing in interpersonal communication environments (Majerczak & Strzelecki, 2022 ); when trust is established, individuals are more willing to share their resources and less suspicious of being exploited. Trust has also been shown to influence consumers’ participation in community building and content sharing on social media, demonstrating cross-cultural universality (Anaya-Sánchez et al., 2020 ).

Trust in influencer advertising information is also a key predictor of consumers’ information exchange online. With many social media users now operating under real-name policies, there is an increased inclination to trust information shared on social media over that posted by corporate accounts or anonymously. Additionally, as users’ social networks partially overlap with their real-life interpersonal networks, extensive research shows that more consumers increasingly rely on information posted and shared on social networks when making purchase decisions (Wang et al., 2016 ). This aligns with the effectiveness goals of influencer marketing advertisements and the characteristics of consumer engagement. Trust in the content posted by influencers is considered a manifestation of a strong relationship between fans and influencers, central to relationship marketing (Kim & Kim, 2021 ). Based on trust in the influencer, which then extends to trust in their content, people are more inclined to browse information posted by influencers, share this information with others, and even create their own content without fear of exploitation or negative consequences. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H3a: Information trust is positively correlated with content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H3b: Information trust is positively correlated with content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H3c: Information trust is positively correlated with content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Construction of the path from stimulus to organism: influencer factors, advertising information factors, social factors, and self-determination internal factors

Having established the logical connection from Organism (O) to Response (R), we further construct the influence path from Stimulus (S) to Organism (O). Revisiting the definition of influencer advertising in social media, companies, and brands leverage influencers on social media platforms to disseminate advertising content, utilizing the influencers’ relationships and influence over consumers for marketing purposes. In addition to consumer’s internal factors, elements such as companies, brands, influencers, and the advertisements themselves also impact consumer behavior. Although factors like the brand image perception of companies may influence consumer behavior, considering that in influencer marketing, companies and brands do not directly interact with consumers, this study prioritizes the dimensions of influencers and advertisements. Furthermore, the impact of social factors on individual cognition and behavior is significant, thus, the current study integrates influencers, advertisements, and social dimensions as the Stimulus (S) component.

Influencer factors: parasocial identification

Self-determination theory posits that relationships are one of the key motivators influencing individual behavior. In the context of social media research, users anticipate establishing a parasocial relationship with influencers, resembling real-life relationships. Hence, we consider the parasocial identification arising from users’ parasocial interactions with influencers as the relational motivator. Parasocial interaction refers to the one-sided personal relationship that individuals develop with media characters (Donald & Richard, 1956 ). During this process, individuals believe that the media character is directly communicating with them, creating a sense of positive intimacy (Giles, 2002 ). Over time, through repeated unilateral interactions with media characters, individuals develop a parasocial relationship, leading to parasocial identification. However, parasocial identification should not be directly equated with the concept of social identification in social identity theory. Social identification occurs when individuals psychologically de-individualize themselves, perceiving the characteristics of their social group as their own, upon identifying themselves as part of that group. In contrast, parasocial identification refers to the one-sided interactional identification with media characters (such as celebrities or influencers) over time (Chen et al., 2021 ). Particularly when individuals’ needs for interpersonal interaction are not met in their daily lives, they turn to parasocial interactions to fulfill these needs (Shan et al., 2020 ). Especially on social media, which is characterized by its high visibility and interactivity, users can easily develop a strong parasocial identification with the influencers they follow (Wei et al., 2022 ).

Parasocial identification and self-disclosure willingness

Theories like uncertainty reduction, personal construct, and social exchange are often applied to explain the emergence of parasocial identification. Social media, with its convenient and interactive modes of information dissemination, enables consumers to easily follow influencers on media platforms. They can perceive the personality of influencers through their online content, viewing them as familiar individuals or even friends. Once parasocial identification develops, this pleasurable experience can significantly influence consumers’ cognitions and thus their behavioral responses. Research has explored the impact of parasocial identification on consumer behavior. For instance, Bond et al. found that on Twitter, the intensity of users’ parasocial identification with influencers positively correlates with their continuous monitoring of these influencers’ activities (Bond, 2016 ). Analogous to real life, where we tend to pay more attention to our friends in our social networks, a similar phenomenon occurs in the relationship between consumers and brands. This type of parasocial identification not only makes consumers willing to follow brand pages but also more inclined to voluntarily provide personal information (Chen et al., 2021 ). Based on this logic, we speculate that a similar relationship may exist between social media influencers and their fans. Fans develop parasocial identification with influencers through social media interactions, making them more willing to disclose their information, opinions, and views in the comment sections of the influencers they follow, engaging in more frequent social interactions (Chung & Cho, 2017 ), even if the content at times may be brand or company-embedded marketing advertisements. In other words, in the presence of influencers with whom they have established parasocial relationships, they are more inclined to disclose personal information, thereby promoting consumer engagement behavior. Therefore, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H4: Parasocial identification is positively correlated with consumer self-disclosure willingness.

H4a: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H4b: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H4c: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Parasocial identification and information trust