- Motivation Techniques

- Motivation for Students

- Motivational Stories

- Financial Motivation

- Motivation for Fitness

- Motivation in the Workplace

- Motivational Quotes

- Parenting and Motivation

- Personal Development

- Productivity Hacks

- Health and Well-being

- Relationship Motivation

- Motivation for Entrepreneurs

- Privacy Policy

The Power of Employee Motivation: Case Studies and Success Stories

Employee motivation is a critical factor in the success of any organization. Motivated employees are more productive, engaged, and innovative, which can ultimately lead to increased profitability and growth. In this article, we’ll explore the power of employee motivation through real-life case studies and success stories, and examine the strategies and approaches that have been effective in motivating employees in different organizations.

Case Studies and Success Stories

Case Study 1: Google

Google is known for its exemplary employee motivation strategies, and one of the most renowned is its “20% time” policy. This policy allows employees to spend 20% of their work time on projects of their choosing. This has led to the development of some of Google’s most successful products, including Gmail and Google Maps. By giving employees autonomy and the freedom to pursue their passions, Google has created a culture of innovation and motivation that has propelled the company to success.

Case Study 2: Southwest Airlines

Southwest Airlines is another company that has excelled in motivating its employees. The company’s founder, Herb Kelleher, recognized the importance of creating a positive work environment and treating employees with respect. This has led to a strong company culture and high employee satisfaction, which in turn has contributed to Southwest’s success as a leading low-cost airline.

Case Study 3: Zappos

Zappos, an online shoe and clothing retailer, is known for its unique approach to employee motivation. The company offers new employees $2,000 to quit after completing their initial training. This may seem counterintuitive, but it has been effective in ensuring that only employees who are truly committed to the company’s values and culture remain. This has created a workforce that is highly motivated and aligned with the company’s mission and vision.

Strategies for Employee Motivation

From the case studies above, we can derive several strategies for motivating employees:

- Empowerment and autonomy: Giving employees the freedom to make decisions and pursue their interests can lead to greater motivation and innovation.

- Positive work culture: Creating a positive and supportive work environment can contribute to higher employee satisfaction and motivation.

- Alignment with company values: Ensuring that employees are aligned with the company’s mission and vision can foster a sense of purpose and motivation.

Success Stories

One success story that demonstrates the power of employee motivation is the story of Mark, a sales manager at a software company. Mark’s team was struggling to meet their sales targets, and morale was low. Mark decided to implement a recognition and rewards program to motivate his team. He started publicly acknowledging and rewarding top performers, and the results were remarkable. Sales increased, and his team’s motivation and engagement soared.

Another success story comes from a manufacturing company that was facing high turnover and low employee morale. The company implemented a mentorship program that paired newer employees with experienced mentors. This initiative helped new employees feel supported and engaged, leading to greater retention and improved overall morale within the organization.

Employee motivation is a crucial factor in the success of any organization. By learning from real-life case studies and success stories, we can see that strategies such as empowerment, positive work culture, and alignment with company values can lead to higher employee motivation and ultimately, greater success for the organization.

Why is employee motivation important?

Employee motivation is important because motivated employees are more productive, engaged, and innovative. They are also more likely to stay with the organization, reducing turnover and associated costs.

How can I motivate my employees?

You can motivate your employees by empowering them, creating a positive work culture, and ensuring alignment with the company’s values and mission. Recognition and rewards programs, mentorship initiatives, and opportunities for personal and professional growth can also be effective in motivating employees.

What are some signs of low employee motivation?

Some signs of low employee motivation include decreased productivity, high turnover, absenteeism, and lack of enthusiasm or engagement in the workplace.

Why Motivated Employees Stay: The Connection to Lower Turnover Rates

The science of personalized motivation: strategies for customizing approaches, from diversity to productivity: motivating a multicultural workforce, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Most Popular

Navigating the depths of self-love and relationships with stefanos sifandos, from dusk till dawn: productivity hacks for night owls, the link between emotional intelligence and motivation: strategies for success, stay inspired: daily motivation tips for fitness newcomers, recent comments, popular category.

- Productivity Hacks 996

- Health and Well-being 403

- Motivation Techniques 393

- Parenting and Motivation 392

- Motivation in the Workplace 392

- Motivational Quotes 386

- Relationship Motivation 383

- Motivation for Fitness 365

Contact us: [email protected]

© © Copyright - All Right Reserved By themotivationcompass.com

The Science of Improving Motivation at Work

The topic of employee motivation can be quite daunting for managers, leaders, and human resources professionals.

Organizations that provide their members with meaningful, engaging work not only contribute to the growth of their bottom line, but also create a sense of vitality and fulfillment that echoes across their organizational cultures and their employees’ personal lives.

“An organization’s ability to learn, and translate that learning into action rapidly, is the ultimate competitive advantage.”

In the context of work, an understanding of motivation can be applied to improve employee productivity and satisfaction; help set individual and organizational goals; put stress in perspective; and structure jobs so that they offer optimal levels of challenge, control, variety, and collaboration.

This article demystifies motivation in the workplace and presents recent findings in organizational behavior that have been found to contribute positively to practices of improving motivation and work life.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

Motivation in the workplace, motivation theories in organizational behavior, employee motivation strategies, motivation and job performance, leadership and motivation, motivation and good business, a take-home message.

Motivation in the workplace has been traditionally understood in terms of extrinsic rewards in the form of compensation, benefits, perks, awards, or career progression.

With today’s rapidly evolving knowledge economy, motivation requires more than a stick-and-carrot approach. Research shows that innovation and creativity, crucial to generating new ideas and greater productivity, are often stifled when extrinsic rewards are introduced.

Daniel Pink (2011) explains the tricky aspect of external rewards and argues that they are like drugs, where more frequent doses are needed more often. Rewards can often signal that an activity is undesirable.

Interesting and challenging activities are often rewarding in themselves. Rewards tend to focus and narrow attention and work well only if they enhance the ability to do something intrinsically valuable. Extrinsic motivation is best when used to motivate employees to perform routine and repetitive activities but can be detrimental for creative endeavors.

Anticipating rewards can also impair judgment and cause risk-seeking behavior because it activates dopamine. We don’t notice peripheral and long-term solutions when immediate rewards are offered. Studies have shown that people will often choose the low road when chasing after rewards because addictive behavior is short-term focused, and some may opt for a quick win.

Pink (2011) warns that greatness and nearsightedness are incompatible, and seven deadly flaws of rewards are soon to follow. He found that anticipating rewards often has undesirable consequences and tends to:

- Extinguish intrinsic motivation

- Decrease performance

- Encourage cheating

- Decrease creativity

- Crowd out good behavior

- Become addictive

- Foster short-term thinking

Pink (2011) suggests that we should reward only routine tasks to boost motivation and provide rationale, acknowledge that some activities are boring, and allow people to complete the task their way. When we increase variety and mastery opportunities at work, we increase motivation.

Rewards should be given only after the task is completed, preferably as a surprise, varied in frequency, and alternated between tangible rewards and praise. Providing information and meaningful, specific feedback about the effort (not the person) has also been found to be more effective than material rewards for increasing motivation (Pink, 2011).

They have shaped the landscape of our understanding of organizational behavior and our approaches to employee motivation. We discuss a few of the most frequently applied theories of motivation in organizational behavior.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory

Frederick Herzberg’s (1959) two-factor theory of motivation, also known as dual-factor theory or motivation-hygiene theory, was a result of a study that analyzed responses of 200 accountants and engineers who were asked about their positive and negative feelings about their work. Herzberg (1959) concluded that two major factors influence employee motivation and satisfaction with their jobs:

- Motivator factors, which can motivate employees to work harder and lead to on-the-job satisfaction, including experiences of greater engagement in and enjoyment of the work, feelings of recognition, and a sense of career progression

- Hygiene factors, which can potentially lead to dissatisfaction and a lack of motivation if they are absent, such as adequate compensation, effective company policies, comprehensive benefits, or good relationships with managers and coworkers

Herzberg (1959) maintained that while motivator and hygiene factors both influence motivation, they appeared to work entirely independently of each other. He found that motivator factors increased employee satisfaction and motivation, but the absence of these factors didn’t necessarily cause dissatisfaction.

Likewise, the presence of hygiene factors didn’t appear to increase satisfaction and motivation, but their absence caused an increase in dissatisfaction. It is debatable whether his theory would hold true today outside of blue-collar industries, particularly among younger generations, who may be looking for meaningful work and growth.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory proposed that employees become motivated along a continuum of needs from basic physiological needs to higher level psychological needs for growth and self-actualization . The hierarchy was originally conceptualized into five levels:

- Physiological needs that must be met for a person to survive, such as food, water, and shelter

- Safety needs that include personal and financial security, health, and wellbeing

- Belonging needs for friendships, relationships, and family

- Esteem needs that include feelings of confidence in the self and respect from others

- Self-actualization needs that define the desire to achieve everything we possibly can and realize our full potential

According to the hierarchy of needs, we must be in good health, safe, and secure with meaningful relationships and confidence before we can reach for the realization of our full potential.

For a full discussion of other theories of psychological needs and the importance of need satisfaction, see our article on How to Motivate .

Hawthorne effect

The Hawthorne effect, named after a series of social experiments on the influence of physical conditions on productivity at Western Electric’s factory in Hawthorne, Chicago, in the 1920s and 30s, was first described by Henry Landsberger in 1958 after he noticed some people tended to work harder and perform better when researchers were observing them.

Although the researchers changed many physical conditions throughout the experiments, including lighting, working hours, and breaks, increases in employee productivity were more significant in response to the attention being paid to them, rather than the physical changes themselves.

Today the Hawthorne effect is best understood as a justification for the value of providing employees with specific and meaningful feedback and recognition. It is contradicted by the existence of results-only workplace environments that allow complete autonomy and are focused on performance and deliverables rather than managing employees.

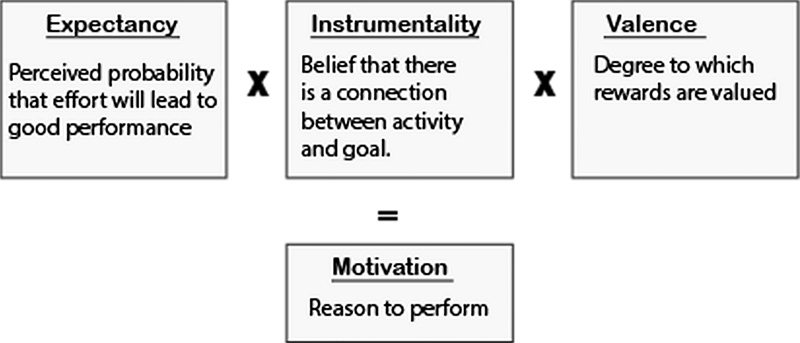

Expectancy theory

Expectancy theory proposes that we are motivated by our expectations of the outcomes as a result of our behavior and make a decision based on the likelihood of being rewarded for that behavior in a way that we perceive as valuable.

For example, an employee may be more likely to work harder if they have been promised a raise than if they only assumed they might get one.

Expectancy theory posits that three elements affect our behavioral choices:

- Expectancy is the belief that our effort will result in our desired goal and is based on our past experience and influenced by our self-confidence and anticipation of how difficult the goal is to achieve.

- Instrumentality is the belief that we will receive a reward if we meet performance expectations.

- Valence is the value we place on the reward.

Expectancy theory tells us that we are most motivated when we believe that we will receive the desired reward if we hit an achievable and valued target, and least motivated if we do not care for the reward or do not believe that our efforts will result in the reward.

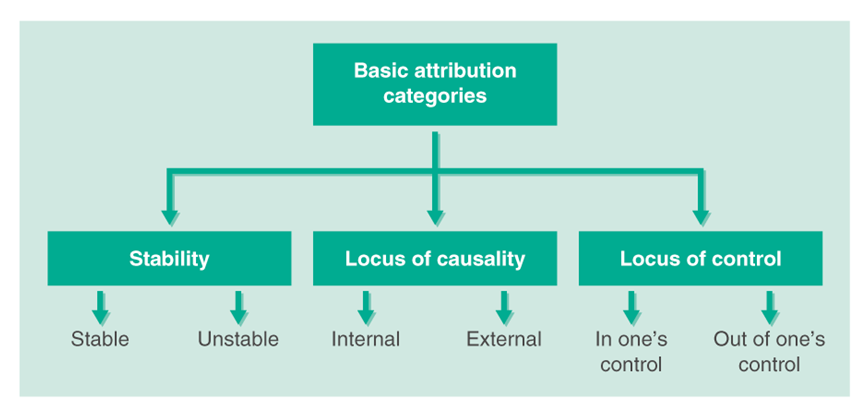

Three-dimensional theory of attribution

Attribution theory explains how we attach meaning to our own and other people’s behavior and how the characteristics of these attributions can affect future motivation.

Bernard Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution proposes that the nature of the specific attribution, such as bad luck or not working hard enough, is less important than the characteristics of that attribution as perceived and experienced by the individual. According to Weiner, there are three main characteristics of attributions that can influence how we behave in the future:

Stability is related to pervasiveness and permanence; an example of a stable factor is an employee believing that they failed to meet the expectation because of a lack of support or competence. An unstable factor might be not performing well due to illness or a temporary shortage of resources.

“There are no secrets to success. It is the result of preparation, hard work, and learning from failure.”

Colin Powell

According to Weiner, stable attributions for successful achievements can be informed by previous positive experiences, such as completing the project on time, and can lead to positive expectations and higher motivation for success in the future. Adverse situations, such as repeated failures to meet the deadline, can lead to stable attributions characterized by a sense of futility and lower expectations in the future.

Locus of control describes a perspective about the event as caused by either an internal or an external factor. For example, if the employee believes it was their fault the project failed, because of an innate quality such as a lack of skills or ability to meet the challenge, they may be less motivated in the future.

If they believe an external factor was to blame, such as an unrealistic deadline or shortage of staff, they may not experience such a drop in motivation.

Controllability defines how controllable or avoidable the situation was. If an employee believes they could have performed better, they may be less motivated to try again in the future than someone who believes that factors outside of their control caused the circumstances surrounding the setback.

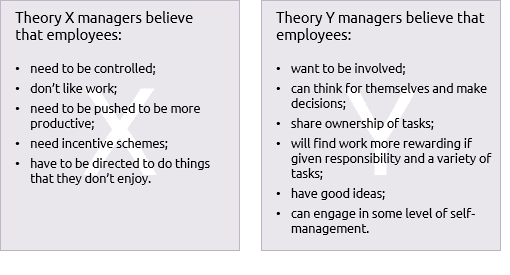

Theory X and theory Y

Douglas McGregor proposed two theories to describe managerial views on employee motivation: theory X and theory Y. These views of employee motivation have drastically different implications for management.

He divided leaders into those who believe most employees avoid work and dislike responsibility (theory X managers) and those who say that most employees enjoy work and exert effort when they have control in the workplace (theory Y managers).

To motivate theory X employees, the company needs to push and control their staff through enforcing rules and implementing punishments.

Theory Y employees, on the other hand, are perceived as consciously choosing to be involved in their work. They are self-motivated and can exert self-management, and leaders’ responsibility is to create a supportive environment and develop opportunities for employees to take on responsibility and show creativity.

Theory X is heavily informed by what we know about intrinsic motivation and the role that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs plays in effective employee motivation.

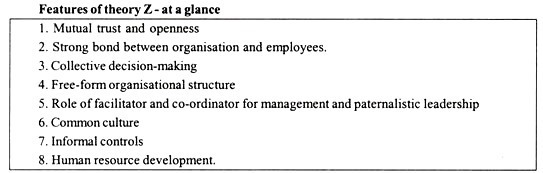

Taking theory X and theory Y as a starting point, theory Z was developed by Dr. William Ouchi. The theory combines American and Japanese management philosophies and focuses on long-term job security, consensual decision making, slow evaluation and promotion procedures, and individual responsibility within a group context.

Its noble goals include increasing employee loyalty to the company by providing a job for life, focusing on the employee’s wellbeing, and encouraging group work and social interaction to motivate employees in the workplace.

There are several implications of these numerous theories on ways to motivate employees. They vary with whatever perspectives leadership ascribes to motivation and how that is cascaded down and incorporated into practices, policies, and culture.

The effectiveness of these approaches is further determined by whether individual preferences for motivation are considered. Nevertheless, various motivational theories can guide our focus on aspects of organizational behavior that may require intervening.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory , for example, implies that for the happiest and most productive workforce, companies need to work on improving both motivator and hygiene factors.

The theory suggests that to help motivate employees, the organization must ensure that everyone feels appreciated and supported, is given plenty of specific and meaningful feedback, and has an understanding of and confidence in how they can grow and progress professionally.

To prevent job dissatisfaction, companies must make sure to address hygiene factors by offering employees the best possible working conditions, fair pay, and supportive relationships.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs , on the other hand, can be used to transform a business where managers struggle with the abstract concept of self-actualization and tend to focus too much on lower level needs. Chip Conley, the founder of the Joie de Vivre hotel chain and head of hospitality at Airbnb, found one way to address this dilemma by helping his employees understand the meaning of their roles during a staff retreat.

In one exercise, he asked groups of housekeepers to describe themselves and their job responsibilities by giving their group a name that reflects the nature and the purpose of what they were doing. They came up with names such as “The Serenity Sisters,” “The Clutter Busters,” and “The Peace of Mind Police.”

These designations provided a meaningful rationale and gave them a sense that they were doing more than just cleaning, instead “creating a space for a traveler who was far away from home to feel safe and protected” (Pattison, 2010). By showing them the value of their roles, Conley enabled his employees to feel respected and motivated to work harder.

The Hawthorne effect studies and Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution have implications for providing and soliciting regular feedback and praise. Recognizing employees’ efforts and providing specific and constructive feedback in the areas where they can improve can help prevent them from attributing their failures to an innate lack of skills.

Praising employees for improvement or using the correct methodology, even if the ultimate results were not achieved, can encourage them to reframe setbacks as learning opportunities. This can foster an environment of psychological safety that can further contribute to the view that success is controllable by using different strategies and setting achievable goals .

Theories X, Y, and Z show that one of the most impactful ways to build a thriving organization is to craft organizational practices that build autonomy, competence, and belonging. These practices include providing decision-making discretion, sharing information broadly, minimizing incidents of incivility, and offering performance feedback.

Being told what to do is not an effective way to negotiate. Having a sense of autonomy at work fuels vitality and growth and creates environments where employees are more likely to thrive when empowered to make decisions that affect their work.

Feedback satisfies the psychological need for competence. When others value our work, we tend to appreciate it more and work harder. Particularly two-way, open, frequent, and guided feedback creates opportunities for learning.

Frequent and specific feedback helps people know where they stand in terms of their skills, competencies, and performance, and builds feelings of competence and thriving. Immediate, specific, and public praise focusing on effort and behavior and not traits is most effective. Positive feedback energizes employees to seek their full potential.

Lack of appreciation is psychologically exhausting, and studies show that recognition improves health because people experience less stress. In addition to being acknowledged by their manager, peer-to-peer recognition was shown to have a positive impact on the employee experience (Anderson, 2018). Rewarding the team around the person who did well and giving more responsibility to top performers rather than time off also had a positive impact.

Stop trying to motivate your employees – Kerry Goyette

Other approaches to motivation at work include those that focus on meaning and those that stress the importance of creating positive work environments.

Meaningful work is increasingly considered to be a cornerstone of motivation. In some cases, burnout is not caused by too much work, but by too little meaning. For many years, researchers have recognized the motivating potential of task significance and doing work that affects the wellbeing of others.

All too often, employees do work that makes a difference but never have the chance to see or to meet the people affected. Research by Adam Grant (2013) speaks to the power of long-term goals that benefit others and shows how the use of meaning to motivate those who are not likely to climb the ladder can make the job meaningful by broadening perspectives.

Creating an upbeat, positive work environment can also play an essential role in increasing employee motivation and can be accomplished through the following:

- Encouraging teamwork and sharing ideas

- Providing tools and knowledge to perform well

- Eliminating conflict as it arises

- Giving employees the freedom to work independently when appropriate

- Helping employees establish professional goals and objectives and aligning these goals with the individual’s self-esteem

- Making the cause and effect relationship clear by establishing a goal and its reward

- Offering encouragement when workers hit notable milestones

- Celebrating employee achievements and team accomplishments while avoiding comparing one worker’s achievements to those of others

- Offering the incentive of a profit-sharing program and collective goal setting and teamwork

- Soliciting employee input through regular surveys of employee satisfaction

- Providing professional enrichment through providing tuition reimbursement and encouraging employees to pursue additional education and participate in industry organizations, skills workshops, and seminars

- Motivating through curiosity and creating an environment that stimulates employee interest to learn more

- Using cooperation and competition as a form of motivation based on individual preferences

Sometimes, inexperienced leaders will assume that the same factors that motivate one employee, or the leaders themselves, will motivate others too. Some will make the mistake of introducing de-motivating factors into the workplace, such as punishment for mistakes or frequent criticism, but negative reinforcement rarely works and often backfires.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

There are several positive psychology interventions that can be used in the workplace to improve important outcomes, such as reduced job stress and increased motivation, work engagement, and job performance. Numerous empirical studies have been conducted in recent years to verify the effects of these interventions.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Psychological capital interventions

Psychological capital interventions are associated with a variety of work outcomes that include improved job performance, engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors (Avey, 2014; Luthans & Youssef-Morgan 2017). Psychological capital refers to a psychological state that is malleable and open to development and consists of four major components:

- Self-efficacy and confidence in our ability to succeed at challenging work tasks

- Optimism and positive attributions about the future of our career or company

- Hope and redirecting paths to work goals in the face of obstacles

- Resilience in the workplace and bouncing back from adverse situations (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017)

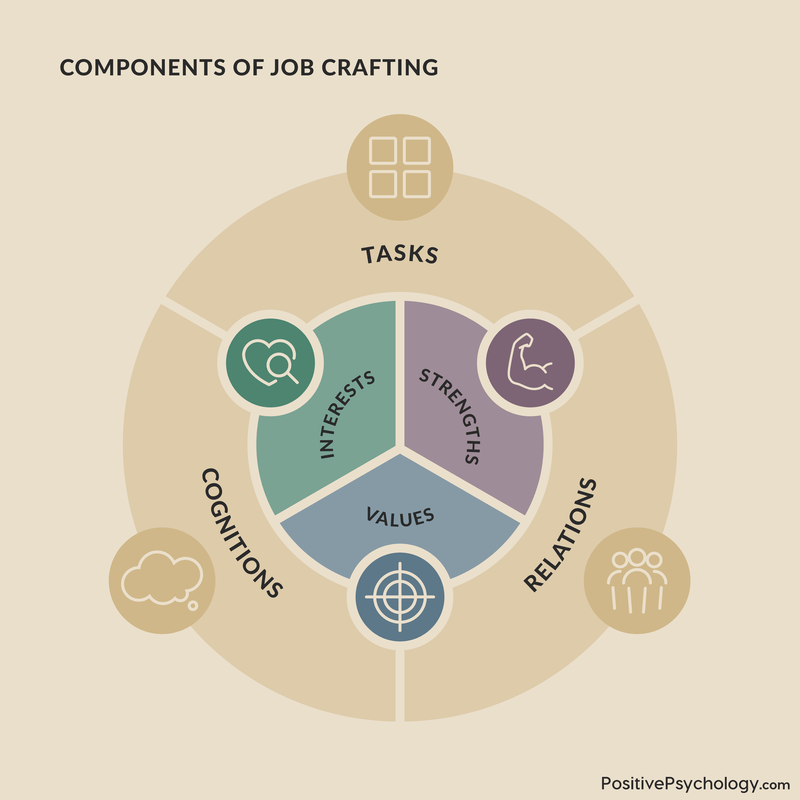

Job crafting interventions

Job crafting interventions – where employees design and have control over the characteristics of their work to create an optimal fit between work demands and their personal strengths – can lead to improved performance and greater work engagement (Bakker, Tims, & Derks, 2012; van Wingerden, Bakker, & Derks, 2016).

The concept of job crafting is rooted in the jobs demands–resources theory and suggests that employee motivation, engagement, and performance can be influenced by practices such as (Bakker et al., 2012):

- Attempts to alter social job resources, such as feedback and coaching

- Structural job resources, such as opportunities to develop at work

- Challenging job demands, such as reducing workload and creating new projects

Job crafting is a self-initiated, proactive process by which employees change elements of their jobs to optimize the fit between their job demands and personal needs, abilities, and strengths (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

Today’s motivation research shows that participation is likely to lead to several positive behaviors as long as managers encourage greater engagement, motivation, and productivity while recognizing the importance of rest and work recovery.

One key factor for increasing work engagement is psychological safety (Kahn, 1990). Psychological safety allows an employee or team member to engage in interpersonal risk taking and refers to being able to bring our authentic self to work without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career (Edmondson, 1999).

When employees perceive psychological safety, they are less likely to be distracted by negative emotions such as fear, which stems from worrying about controlling perceptions of managers and colleagues.

Dealing with fear also requires intense emotional regulation (Barsade, Brief, & Spataro, 2003), which takes away from the ability to fully immerse ourselves in our work tasks. The presence of psychological safety in the workplace decreases such distractions and allows employees to expend their energy toward being absorbed and attentive to work tasks.

Effective structural features, such as coaching leadership and context support, are some ways managers can initiate psychological safety in the workplace (Hackman, 1987). Leaders’ behavior can significantly influence how employees behave and lead to greater trust (Tyler & Lind, 1992).

Supportive, coaching-oriented, and non-defensive responses to employee concerns and questions can lead to heightened feelings of safety and ensure the presence of vital psychological capital.

Another essential factor for increasing work engagement and motivation is the balance between employees’ job demands and resources.

Job demands can stem from time pressures, physical demands, high priority, and shift work and are not necessarily detrimental. High job demands and high resources can both increase engagement, but it is important that employees perceive that they are in balance, with sufficient resources to deal with their work demands (Crawford, LePine, & Rich, 2010).

Challenging demands can be very motivating, energizing employees to achieve their goals and stimulating their personal growth. Still, they also require that employees be more attentive and absorbed and direct more energy toward their work (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014).

Unfortunately, when employees perceive that they do not have enough control to tackle these challenging demands, the same high demands will be experienced as very depleting (Karasek, 1979).

This sense of perceived control can be increased with sufficient resources like managerial and peer support and, like the effects of psychological safety, can ensure that employees are not hindered by distraction that can limit their attention, absorption, and energy.

The job demands–resources occupational stress model suggests that job demands that force employees to be attentive and absorbed can be depleting if not coupled with adequate resources, and shows how sufficient resources allow employees to sustain a positive level of engagement that does not eventually lead to discouragement or burnout (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001).

And last but not least, another set of factors that are critical for increasing work engagement involves core self-evaluations and self-concept (Judge & Bono, 2001). Efficacy, self-esteem, locus of control, identity, and perceived social impact may be critical drivers of an individual’s psychological availability, as evident in the attention, absorption, and energy directed toward their work.

Self-esteem and efficacy are enhanced by increasing employees’ general confidence in their abilities, which in turn assists in making them feel secure about themselves and, therefore, more motivated and engaged in their work (Crawford et al., 2010).

Social impact, in particular, has become increasingly important in the growing tendency for employees to seek out meaningful work. One such example is the MBA Oath created by 25 graduating Harvard business students pledging to lead professional careers marked with integrity and ethics:

The MBA oath

“As a business leader, I recognize my role in society.

My purpose is to lead people and manage resources to create value that no single individual can create alone.

My decisions affect the well-being of individuals inside and outside my enterprise, today and tomorrow. Therefore, I promise that:

- I will manage my enterprise with loyalty and care, and will not advance my personal interests at the expense of my enterprise or society.

- I will understand and uphold, in letter and spirit, the laws and contracts governing my conduct and that of my enterprise.

- I will refrain from corruption, unfair competition, or business practices harmful to society.

- I will protect the human rights and dignity of all people affected by my enterprise, and I will oppose discrimination and exploitation.

- I will protect the right of future generations to advance their standard of living and enjoy a healthy planet.

- I will report the performance and risks of my enterprise accurately and honestly.

- I will invest in developing myself and others, helping the management profession continue to advance and create sustainable and inclusive prosperity.

In exercising my professional duties according to these principles, I recognize that my behavior must set an example of integrity, eliciting trust, and esteem from those I serve. I will remain accountable to my peers and to society for my actions and for upholding these standards. This oath, I make freely, and upon my honor.”

Job crafting is the process of personalizing work to better align with one’s strengths, values, and interests (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Any job, at any level can be ‘crafted,’ and a well-crafted job offers more autonomy, deeper engagement and improved overall wellbeing.

There are three types of job crafting:

- Task crafting involves adding or removing tasks, spending more or less time on certain tasks, or redesigning tasks so that they better align with your core strengths (Berg et al., 2013).

- Relational crafting includes building, reframing, and adapting relationships to foster meaningfulness (Berg et al., 2013).

- Cognitive crafting defines how we think about our jobs, including how we perceive tasks and the meaning behind them.

If you would like to guide others through their own unique job crafting journey, our set of Job Crafting Manuals (PDF) offer a ready-made 7-session coaching trajectory.

Prosocial motivation is an important driver behind many individual and collective accomplishments at work.

It is a strong predictor of persistence, performance, and productivity when accompanied by intrinsic motivation. Prosocial motivation was also indicative of more affiliative citizenship behaviors when it was accompanied by motivation toward impression management motivation and was a stronger predictor of job performance when managers were perceived as trustworthy (Ciulla, 2000).

On a day-to-day basis most jobs can’t fill the tall order of making the world better, but particular incidents at work have meaning because you make a valuable contribution or you are able to genuinely help someone in need.

J. B. Ciulla

Prosocial motivation was shown to enhance the creativity of intrinsically motivated employees, the performance of employees with high core self-evaluations, and the performance evaluations of proactive employees. The psychological mechanisms that enable this are the importance placed on task significance, encouraging perspective taking, and fostering social emotions of anticipated guilt and gratitude (Ciulla, 2000).

Some argue that organizations whose products and services contribute to positive human growth are examples of what constitutes good business (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004). Businesses with a soul are those enterprises where employees experience deep engagement and develop greater complexity.

In these unique environments, employees are provided opportunities to do what they do best. In return, their organizations reap the benefits of higher productivity and lower turnover, as well as greater profit, customer satisfaction, and workplace safety. Most importantly, however, the level of engagement, involvement, or degree to which employees are positively stretched contributes to the experience of wellbeing at work (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004).

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Daniel Pink (2011) argues that when it comes to motivation, management is the problem, not the solution, as it represents antiquated notions of what motivates people. He claims that even the most sophisticated forms of empowering employees and providing flexibility are no more than civilized forms of control.

He gives an example of companies that fall under the umbrella of what is known as results-only work environments (ROWEs), which allow all their employees to work whenever and wherever they want as long their work gets done.

Valuing results rather than face time can change the cultural definition of a successful worker by challenging the notion that long hours and constant availability signal commitment (Kelly, Moen, & Tranby, 2011).

Studies show that ROWEs can increase employees’ control over their work schedule; improve work–life fit; positively affect employees’ sleep duration, energy levels, self-reported health, and exercise; and decrease tobacco and alcohol use (Moen, Kelly, & Lam, 2013; Moen, Kelly, Tranby, & Huang, 2011).

Perhaps this type of solution sounds overly ambitious, and many traditional working environments are not ready for such drastic changes. Nevertheless, it is hard to ignore the quickly amassing evidence that work environments that offer autonomy, opportunities for growth, and pursuit of meaning are good for our health, our souls, and our society.

Leave us your thoughts on this topic.

Related reading: Motivation in Education: What It Takes to Motivate Our Kids

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

- Anderson, D. (2018, February 22). 11 Surprising statistics about employee recognition [infographic]. Best Practice in Human Resources. Retrieved from https://www.bestpracticeinhr.com/11-surprising-statistics-about-employee-recognition-infographic/

- Avey, J. B. (2014). The left side of psychological capital: New evidence on the antecedents of PsyCap. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21( 2), 141–149.

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (vol. 3). John Wiley and Sons.

- Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations , 65 (10), 1359–1378

- Barsade, S. G., Brief, A. P., & Spataro, S. E. (2003). The affective revolution in organizational behavior: The emergence of a paradigm. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 3–52). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104) . American Psychological Association.

- Ciulla, J. B. (2000). The working life: The promise and betrayal of modern work. Three Rivers Press.

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology , 95 (5), 834–848.

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2004). Good business: Leadership, flow, and the making of meaning. Penguin Books.

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology , 863) , 499–512.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly , 44 (2), 350–383.

- Grant, A. M. (2013). Give and take: A revolutionary approach to success. Penguin.

- Hackman, J. R. (1987). The design of work teams. In J. Lorsch (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 315–342). Prentice-Hall.

- Herzberg, F. (1959). The motivation to work. Wiley.

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits – self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability – with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology , 86 (1), 80–92.

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal , 33 (4), 692–724.

- Karasek, R. A., Jr. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (2), 285–308.

- Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., & Tranby, E. (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review , 76 (2), 265–290.

- Landsberger, H. A. (1958). Hawthorne revisited: Management and the worker, its critics, and developments in human relations in industry. Cornell University.

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4 , 339-366.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E. L., & Lam, J. (2013). Healthy work revisited: Do changes in time strain predict well-being? Journal of occupational health psychology, 18 (2), 157.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E., Tranby, E., & Huang, Q. (2011). Changing work, changing health: Can real work-time flexibility promote health behaviors and well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(4), 404–429.

- Pattison, K. (2010, August 26). Chip Conley took the Maslow pyramid, made it an employee pyramid and saved his company. Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/1685009/chip-conley-took-maslow-pyramid-made-it-employee-pyramid-and-saved-his-company

- Pink, D. H. (2011). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Penguin.

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2) , 1-9.

- Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 25) (pp. 115–191). Academic Press.

- von Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2016). A test of a job demands–resources intervention. Journal of Managerial Psychology , 31 (3), 686–701.

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26 (2), 179–201.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Good and helpful study thank you. It will help achieving goals for my clients. Thank you for this information

A lot of data is really given. Validation is correct. The next step is the exchange of knowledge in order to create an optimal model of motivation.

A good article, thank you for sharing. The views and work by the likes of Daniel Pink, Dan Ariely, Barry Schwartz etc have really got me questioning and reflecting on my own views on workplace motivation. There are far too many organisations and leaders who continue to rely on hedonic principles for motivation (until recently, myself included!!). An excellent book which shares these modern views is ‘Primed to Perform’ by Doshi and McGregor (2015). Based on the earlier work of Deci and Ryan’s self determination theory the book explores the principle of ‘why people work, determines how well they work’. A easy to read and enjoyable book that offers a very practical way of applying in the workplace.

Thanks for mentioning that. Sounds like a good read.

All the best, Annelé

Motivation – a piece of art every manager should obtain and remember by heart and continue to embrace.

Exceptionally good write-up on the subject applicable for personal and professional betterment. Simplified theorem appeals to think and learn at least one thing that means an inspiration to the reader. I appreciate your efforts through this contributive work.

Excelente artículo sobre motivación. Me inspira. Gracias

Very helpful for everyone studying motivation right now! It’s brilliant the way it’s witten and also brought to the reader. Thank you.

Such a brilliant piece! A super coverage of existing theories clearly written. It serves as an excellent overview (or reminder for those of us who once knew the older stuff by heart!) Thank you!

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

How to Encourage Clients to Embrace Change

Many of us struggle with change, especially when it’s imposed upon us rather than chosen. Yet despite its inevitability, without it, there would be no [...]

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Theory of Motivation

Motivation is vital to beginning and maintaining healthy behavior in the workplace, education, and beyond, and it drives us toward our desired outcomes (Zajda, 2023). [...]

SMART Goals, HARD Goals, PACT, or OKRs: What Works?

Goal setting is vital in business, education, and performance environments such as sports, yet it is also a key component of many coaching and counseling [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (55)

- Coaching & Application (59)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (27)

- Meditation (21)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (46)

- Optimism & Mindset (35)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (48)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (20)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (40)

- Self Awareness (22)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (33)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (38)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Goal Achievement Exercises Pack

5 Real-World Case Studies that Prove the Power of Intrinsic Motivation

The Call for Intrinsic Motivation

The way we think about motivation is changing, and as Learning & Development and HR professionals, it's our responsibility to adapt and guide this transformation. Traditional methods of carrot-and-stick motivation are increasingly viewed as obsolete, paving the way for a more nuanced approach focusing on intrinsic motivators like autonomy, mastery, and purpose. "Control leads to compliance; autonomy leads to engagement," as research has famously shown. Today, we'll delve into five real-world case studies to demonstrate the tangible impact of intrinsic motivation on organizational performance.

1. Google's 20% Time: Autonomy in Action

The initiative.

Google's 20% Time allows employees to spend a fifth of their working hours on projects they're passionate about, unrelated to their primary job responsibilities.

The Results

This policy has led to the development of some of Google's most successful products, like Gmail and Google News. By granting autonomy, Google has managed to foster innovation, job satisfaction, and exceptional performance.

Lessons for L&D and HR Professionals

Use similar "innovation time" projects in your organization to build a culture of autonomy. Even if it's not 20%, giving employees some time to work on what engages them can pay off significantly.

2. Zappos: Delivering Happiness Through Purpose

Zappos's core purpose goes beyond selling shoes and clothing. They aim to "deliver happiness."

Zappos has one of the most loyal customer bases, boasting a retention rate of 75%. Employees are more engaged because they see a higher purpose to their work beyond just selling products.

Work to identify and communicate the higher purpose of your company. Make this purpose a central part of your onboarding and training processes to instill intrinsic motivation.

3. Atlassian’s ShipIt Days: Mastering Skills in 24 Hours

Atlassian has a quarterly event called "ShipIt Day" where employees have 24 hours to complete a project of their choice.

This has not only resulted in valuable new product features but has also boosted employee morale and job satisfaction.

Consider short-term, intensive "hackathons" or skill-building events that allow your team to express their skills and creativity in a non-traditional setting.

4. Adobe's Check-in System: Shifting Away from Control

Adobe has replaced annual performance reviews with regular "check-ins," where the emphasis is on feedback and development, not ratings or promotions.

Voluntary attrition decreased by 30% after the implementation of the system, and internal surveys showed increased employee engagement.

Traditional performance reviews often focus on extrinsic rewards like promotions or raises. Shift the focus towards growth and development to boost intrinsic motivation.

5. Spotify’s Squads: Small Teams, Big Autonomy

Spotify organizes its engineers into "squads," small cross-functional teams that operate like mini-startups.

This enables rapid innovation and high employee engagement. Squads have the autonomy to decide what to build, how to build it, and how to work together while building it.

Autonomy can exist within a framework. Small, empowered teams can execute strategy more quickly and effectively than larger, more bureaucratic structures.

Conclusion: The Road to Intrinsic Motivation

These case studies show us that intrinsic motivation is not just a theoretical concept; it has practical implications that can significantly boost your organization's performance. Whether through granting autonomy, fostering a sense of purpose, or facilitating mastery, intrinsic motivation can be a driving force behind business success.

To deepen your understanding of how intrinsic motivation can prepare your organization for any challenge, including economic downturns, check out this asset: Practical Strategies L&D Leaders Can Use to “Recession-Proof” Their Companies and Teams . It provides L&D professionals with actionable insights to cultivate resilient, exceptional leaders and teams.

About the author

Pedro is the content manager of BookClub's Bookshelf Blog. With over a decade in EdTech, Pedro's become the go-to guy for transforming the best of books into engaging blog content. Not only does he have a knack for curating fantastic book lists that keep our readers hooked, but he also has the unique talent of bringing the essence of each book alive on our blog. Pedro might not be a writer by trade, and yes, but don't let that fool you. Having surfed the internet waves since the days before Google existed, he has an unparalleled eye for what makes content truly great. Join Pedro on the Bookshelf Blog as he continues to share book lists, insights, and treasures he finds along his journey.

Stay Up to Date

Your go-to resource for avid readers! Discover a wealth of information on non-fiction business books aimed at boosting your professional development.

Related articles

We’ve partnered with ATD

Making Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Accessible through Book Clubs

Creating a Culture of Wellness: 9 Essential Reads on Workplace Mental Health

A CASE STUDY ON EMPLOYEE MOTIVATION IN AN ORGANISATION

- February 2022

- Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Viswa Mahavidyalaya University

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- . S Pavan Mr

- B E Student

- Sannapaneni Anand

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Behav Sci (Basel)

Work Motivation: The Roles of Individual Needs and Social Conditions

Thuy thi diem vo.

1 Department of Business Administration, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, No. 43, Section 4, Keelung Road, Da’an District, Taipei City 106335, Taiwan; wt.ude.tsutn.liam@31880701d (T.T.D.V.); wt.ude.tsutn.liam@nehcwc (C.-W.C.)

Kristine Velasquez Tuliao

2 Graduate Institute of Human Resource Management, National Central University, No. 300, Zhongda Road, Zhongli District, Taoyuan City 320317, Taiwan

Chung-Wen Chen

Associated data.

The data that support this study are publicly available.

Work motivation plays a vital role in the development of organizations, as it increases employee productivity and effectiveness. To expand insights into individuals’ work motivation, the authors investigated the influence of individuals’ competence, autonomy, and social relatedness on their work motivation. Additionally, the country-level moderating factors of those individual-level associations were examined. Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was used to analyze data from 32,614 individuals from 25 countries, obtained from the World Values Survey (WVS). Findings showed that autonomy and social relatedness positively impacted work motivation, while competence negatively influenced work motivation. Moreover, the individual-level associations were moderated by the country-level religious affiliation, political participation, humane orientation, and in-group collectivism. Contributions, practical implications, and directions for further research were then discussed.

1. Introduction

Work motivation is considered an essential catalyst for the success of organizations, as it promotes employees’ effective performance. To achieve an organization’s objectives, the employer depends on the performance of their employees [ 1 ]. However, insufficiently motivated employees perform poorly despite being skillful [ 1 , 2 ]. Employers, therefore, need their employees to work with complete motivation rather than just showing up at their workplaces [ 3 ]. Work motivation remains a vital factor in organizational psychology, as it helps explain the causes of individual conduct in organizations [ 4 ]. Consequently, studies on the factors that encourage work motivation can contribute to the theoretical underpinnings on the roots of individual and practical social conditions that optimize individuals’ performance and wellness [ 5 ].

Several decades of research have endeavored to explain the dynamics that initiate work-related behavior. The primary factor examining this aspect is motivation, as it explains why individuals do what they do [ 6 ]. The basic psychological needs have represented a vital rationalization of individual differences in work motivation. Psychological needs are considered natural psychological nutrients and humans’ inner resources. They have a close relationship with individual conduct and have a strong explicit meaning for work performance [ 7 , 8 ]. Different needs are essential drivers of individual functioning due to the satisfaction derived from dealing with them [ 9 ]. In addition to individual-level antecedents, the social context has also been regarded to have implications for work motivation. Social exchange and interaction among individuals accentuate the importance of work motivation as something to be studied with consideration of contextual factors [ 10 ].

Significant contributions have been made to the socio-psychological perspective of work motivation ( Table 1 ). However, current literature shows three deficiencies. First, over 150 papers utilize the key approaches of psychological needs to justify motivational processes in the workplace [ 11 ], which justifies the vital role of psychological needs in interpreting individual work motivation. The association between psychological needs and work motivation has often been implicitly assumed; however, the influence of psychological needs on work motivation has been inadequately tested [ 8 ]. The verification of the extent and the direction of influence will provide a better understanding of, and offer distinct implications for, the facilitation of work motivation. In examining the influence of psychological needs on work motivation, this paper mainly focuses on the intrinsic aspect of motivation. The study of Alzahrani et al. (2018) [ 12 ] argued that although intrinsic motivation is more efficient than extrinsic motivation, researchers have mostly neglected it.

Several investigated predictors of work motivation in general and intrinsic motivation in particular.

| Predictors of Work Motivation | Authors |

|---|---|

| Personal factors (age, gender, educational level, living setting, health status, and family support) | Lin, 2020 [ ] |

| Emotional intelligence | Bechter et al., 2021 [ ] |

| Interpersonal relationship quality | |

| Social exchange | Hinsz, 2008 [ ] |

| Interaction among individuals | |

| Contextual factors | |

| Cultures | Bhagat et al., 1995 [ ]; Erez, 1994/1997/2008 [ , , ] |

| Social situations | Deci & Ryan, 2012 [ ] |

| Psychological needs (but inadequacy) | Olafsen et al., 2018 [ ] |

Second, there is no study examining the country-level moderating effects of social conditions and national cultures on individual relationships between psychological needs and work motivation. Pinder (2014) [ 20 ] argued that contextual practices could influence variables at the individual level. Culture is a crucial factor influencing motivation [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Researchers (e.g., [ 19 ]) have further suggested that both the proximal social situations (e.g., workgroup) and the distal social situations (e.g., cultural values) in which humans operate influence their need for satisfaction and their motivation type. Intrinsic motivation interacts with prosocial motivation in judging work performance [ 21 ]. By including the social conditions in the framework, prosocial motivation is considered. Prosocial motivation refers to the desire to help and promote the welfare of others [ 22 , 23 ]. The study of Shao et al. (2019) [ 24 ] proposed that prosocial motivation promotes employee engagement in particular organizational tasks. Researchers often consider prosocial motivation as a pattern of intrinsic motivation [ 23 ]. This implies that when intrinsic motivation is investigated, prosocial motivation should be examined together to obtain a comprehensive understanding.

Third, there are few studies using a considerable number of cross-national samples to investigate factors influencing work motivation. A cross-cultural analysis makes the findings more objective by minimizing individual bias towards any particular culture. Therefore, the examination of the study is crucial to expanding insights on the influence of social situations on the individual associations between psychological needs and work motivation.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. work motivation: a conceptual background.

Work motivation is considered “a set of energetic forces that originate both within as well as beyond an individual’s being, to initiate work-related behavior, and to determine its form direction intensity and duration” [ 20 ]. Nicolescu and Verboncu (2008) [ 25 ] argued that work motivation contributes directly and indirectly to employees’ performance. Additionally, research (e.g., [ 26 ]) has postulated that work motivation could be seen as a source of positive energy that leads to employees’ self-recognition and self-fulfillment. Therefore, work motivation is an antecedent of the self-actualization of individuals and the achievement of organizations.

Literature has identified several models of work motivation. One of the primary models is Maslow’s (1954) [ 27 ] need hierarchy theory, which proposes that humans fulfill a set of needs, including physiological, safety and security, belongingness, esteem, and self-actualization. Additionally, Herzberg’s (1966) [ 28 ] motivation-hygiene theory proposed that work motivation is mainly influenced by the job’s intrinsic challenge and provision of opportunities for recognition and reinforcement. More contemporary models also emerged. For instance, the study of Nicolescu and Verboncu (2008) [ 25 ] has categorized the types of motivation into four pairs, including positive-negative, intrinsic-extrinsic, cognitive-affective, and economic-moral spiritual. Additionally, Ryan and Deci [ 29 ] focused on intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation.

With the existence of numerous factors that relate to work motivation, this paper mainly focuses on intrinsic motivation. Previous research found that emotional intelligence and interpersonal relationship quality predict individuals’ intrinsic motivation [ 14 ]. Additionally, the study of Lin (2020) [ 13 ] argued that personal factors, including age, gender, educational level, living setting, health status, and family support, impact people’s intrinsic motivation. To understand more about intrinsic motivation, the authors examined individuals’ psychological needs. Fulfillment of the basic needs is related to wellness and effective performance [ 7 ]. Since intrinsic motivation results in high-quality creativity, recognizing the factors influencing intrinsic motivation is important [ 5 ].

Although a significant number of important contributions have been made regarding intrinsic motivation, self-determination theory is of particular significance for this study. Self-determination theory (SDT) postulates that all humans possess a variety of basic psychological needs. One of the primary crucial needs is the need for competence [ 30 , 31 ], which makes individuals feel confident and effective in their actions. Additionally, the need for autonomy [ 32 ] is one of the important psychological needs, which makes people satisfied with optimal wellness and good performance obtained as a result of their own decisions. Moreover, SDT proposed the crucial importance of interpersonal relationships and how social forces can influence thoughts, emotions, and behaviors [ 33 ]. This means that the psychological need for social relatedness [ 34 ] also plays a significant role in human’s psychological traits. Individuals need to be cared for by others and care for others to perceive belongingness. The need for relatedness can motivate people to behave more socially [ 35 ].

Prior research (e.g., [ 36 ]) has explored self-determination theory and related theories as approaches to work motivation and organizational behavior. The study of Van den Broeck et al. (2010) [ 37 ] emphasized grasping autonomy, competence, and relatedness at workplaces. This paper contributes to the exhaustive understanding of intrinsic work motivation influenced by further examining the impact of these three factors on work motivation as well as the moderating effects of social contexts.

2.2. Main Effect

2.2.1. individuals’ competence and work motivation.

Competence is “the collective learning in the organization, especially how to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technologies” [ 38 ]. The study of Hernández-March et al. (2009) [ 39 ] argued that a stronger competence was commonly found in university graduates rather than those without higher education. Competence has been considered a significant factor of work motivation that enhances productivity and profits. Harter’s (1983) [ 40 ] model of motivation proposed that competence enhances motivation because competence promotes flexibility for individuals [ 41 ]. Likewise, Patall et al. (2014) [ 42 ] indirectly argued that competence positively affects work motivation. Individuals become more engaged in activities that demonstrate their competence [ 6 ]. When people perceive that they are competent enough to attain goals, they generally feel confident and concentrate their efforts on achieving their objectives as soon as possible for their self-fulfillment.

Individuals’ competence positively relates to their work motivation.

2.2.2. Individuals’ Autonomy and Work Motivation

Autonomy is viewed as “self-determination, self-rule, liberty of rights, freedom of will and being one’s own person” [ 43 ]. Reeve (2006) [ 44 ] argued that autonomy is a primary theoretical approach in the study of human motivation and emotion. Autonomy denotes that certain conduct is performed with a sense of willingness [ 30 ]. Several researchers (e.g., [ 45 ]) investigated the positive relationship between individuals’ autonomy and work motivation. When humans are involved in actions because of their interest, they fully perform those activities volitionally [ 36 ]. Dickinson (1995) [ 46 ] also proposed that autonomous individuals are more highly motivated, and autonomy breeds more effective outcomes. Moreover, when individuals have a right to make their own decisions, they tend to be more considerate and responsible for those decisions, as they need to take accountability for their actions. Bandura (1991) [ 47 ] has argued that humans’ ability to reflect, react, and direct their actions motivates them for future purposes. Therefore, autonomy motivates individuals to work harder and overcome difficulties to achieve their objectives.

Individuals’ autonomy positively relates to their work motivation.

2.2.3. Individuals’ Social Relatedness and Work Motivation

The psychological need for social relatedness occurs when an individual has a sense of being secure, related to, or understood by others in the social environment [ 48 ]. The relatedness need is fulfilled when humans experience the feeling of close relationships with others [ 49 ]. Researchers (e.g., [ 34 ]) have postulated that the need for relatedness reflects humans’ natural tendency to feel associated with others, such as being a member of any social groups, or to love and care as well as be loved and cared for. Prior studies have shown that social relatedness strongly impacts motivation [ 50 , 51 , 52 ]. Social relatedness offers people many opportunities to communicate with others, making them more motivated at the workplace, aligning them with the group’s shared objectives. Marks (1974) [ 53 ] suggested that social relatedness encourages individuals to focus on community welfare as a reference for their behavior, resulting in enhanced work motivation. Moreover, when individuals feel that they relate to and are cared for by others, their motivation can be maximized since their relatedness need is fulfilled [ 54 ]. Therefore, establishing close relationships with others plays a vital role in promoting human motivation [ 55 ]. When people perceive that they are cared for and loved by others, they tend to create positive outcomes for common benefits to deserve the kindness received, thereby motivating them to work harder.

Individuals’ social relatedness positively relates to their work motivation.

Aside from exploring the influence of psychological needs on work motivation, this paper also considers country-level factors. Previous research (e.g., [ 56 ]) has examined the influence of social institutions and national cultures on work motivation. However, the moderating effects of country-level factors have to be investigated, given the contextual impacts on individual needs, attitudes, and behavior. Although social conditions provide the most common interpretation for nation-level variance in individual work behaviors [ 57 ], few cross-national studies examine social conditions and individual work behaviors [ 56 ]. Hence, this paper investigates the moderating effects, including religious affiliation, political participation, humane orientation, and in-group collectivism, on the psychological needs-work motivation association.

A notable theory to explain the importance of contextual factors in work motivation that is customarily linked with SDT is the concept of prosocial motivation. Prosocial motivation suggests that individuals have the desire to expend efforts in safeguarding and promoting others’ well-being [ 58 , 59 ]. It is proposed that prosocial motivation strengthens endurance, performance, and productivity, as well as generates creativity that encourages individuals to develop valuable and novel ideas [ 21 , 60 ]. Prosocial motivation is found to interact with intrinsic motivation in influencing positive work outcomes [ 21 , 61 ]. However, there are few studies examining the effects of prosocial motivation on work motivation [ 62 ].

Utilizing the concept of prosocial motivation and examining it on a country-level, this paper suggests that prosocial factors promote basic psychological needs satisfaction that reinforces motivational processes at work. Therefore, prosocial behaviors and values may enhance the positive impact of individuals’ basic psychological needs, including competence, autonomy, and social relatedness, on work motivation.

2.3. Moderating Effects

2.3.1. religious affiliation.

Religions manifest values that are usually employed as grounds to investigate what is right and wrong [ 63 ]. Religious affiliation is considered prosocial because it satisfies the need for belongingness and upholds collective well-being through gatherings to worship, seek assistance, and offer comfort within religious communities. Hence, religious affiliation promotes the satisfaction of individuals’ psychological needs, which directs motivation at work and life in general. Research (e.g., [ 64 ]) has argued that religious affiliation is an essential motivational component given its impact on psychological processes. The study of Simon and Primavera (1972) [ 65 ] investigated the relationship between religious affiliation and work motivation. To humans characterized by competence, autonomy, and social relatedness, attachment to religious principles increases their motivation to accomplish organizational goals. Religious membership will increase the influence of psychological needs on work motivation. The tendency of individuals affiliated with any religion to be demotivated is lower compared to those who are not. Individuals with religious affiliations also tend to work harder as the virtue of hard work is aligned with religious principles. Accordingly, religious affiliation may enhance the positive association between individuals’ psychological needs and work motivation.

2.3.2. Political Participation

Political participation, indicated by people’s voting habits, plays a crucial role in ensuring citizens’ well-being and security [ 66 ]. Political participation encourages shared beliefs and collective goals among individuals [ 67 ]. The communication and interaction among people help them grasp the government’s developmental strategies, motivating them to work harder. Political participation is a collective pursuit that makes societal members feel more confident, socially related, and motivated at work to achieve communal targets. Increased political participation reinforces effective public policy to enhance its members’ welfare, congruent with the perspectives of prosocial motivation. The prosocial values and behaviors derived from political participation satisfy human needs and interact positively with intrinsic motivation. Therefore, political participation may strengthen the positive influence of individuals’ competence, autonomy, and social relatedness on work motivation. Conversely, poor political participation is perceived as a separation from the society that may lead to demotivation. In a society with poor political participation, an individualistic mentality is encouraged, thereby decreasing the desire to pursue cooperative endeavors.

2.3.3. Humane Orientation

GLOBE characterizes humane orientation as “the degree to which an organization or society encourages and rewards individuals for being fair, altruistic, generous, caring, and kind to others” [ 68 ]. Research (e.g., [ 69 , 70 ]) has argued that a high humane orientation encourages members to develop a strong sense of belonging, commit to fair treatment, and manifest benevolence. The desire to help others or enhance others’ well-being indicates prosocial values and behaviors [ 71 , 72 ]. Since humane orientation is correlated with philanthropy and promotes good relations, this cultural value may enhance work motivation. Fairness, which is derived from a humane-oriented society, is one of the most vital influences on work motivation [ 1 ]. Moreover, altruism, promoted by humane-oriented societies, encourages individuals to sacrifice individual interests for shared benefits. Altruism then encourages attachment to others’ welfare and increases resources needed for prosocial behaviors such as work [ 73 , 74 ]. Members of humane-oriented countries view work in a positive light—it is an opportunity for them to perform altruistic behaviors and engage in collective actions. Therefore, people are more likely to work harder for common interests in humane-oriented societies. In such conditions, individuals with competence, autonomy, and social relatedness will be more motivated to work. By contrast, a less humane-oriented society gives prominence to material wealth and personal enjoyment [ 75 ]. Although this may be perceived as a positive influence on the association between psychological needs and work motivation, such an individualistic mindset works against the prosocial factors that further motivate individuals.

2.3.4. In-Group Collectivism

House et al. (2004) [ 68 ] defined in-group collectivism as “the degree to which individuals express pride, loyalty, and cohesiveness in their organizations or families”. Collectivistic cultures indicate the need for individuals to rely on group membership for identification [ 76 ]. High collectivism enhances equity, solidarity, loyalty, and encouragement [ 77 , 78 ]. Humans living in a collectivist culture are interdependent and recognize their responsibilities towards each other [ 79 ]. In-group collectivism transfers the concepts of social engagement, interdependence with others, and care for the group over the self (e.g., [ 79 , 80 , 81 ], thereby motivating individuals to work harder for the common interests. Oyserman et al. (2002) [ 82 ] have further argued that individualistic values encourage an independent personality, whereas collectivistic values form an interdependent one. Therefore, in-group collectivism is a prosocial value that emphasizes the importance of reciprocal relationships and encourages people to work harder to benefit the group. By contrast, low collectivism promotes individual interests and personal well-being while neglecting the value of having strong relations with others [ 70 ]. Considering that in-group collectivism promotes individuals’ prosocial behaviors of individuals, people who are competent, autonomous, and socially related to collective societies are less likely to be demotivated at the workplace. Consequently, in-group collectivism may intensify the positive influence of individuals’ competence, autonomy, and social relatedness on their work motivation.

(a–d): The positive relationship between individuals’ competence and their work motivation is enhanced as religious affiliation (a), political participation (b), humane orientation (c), and in-group collectivism (d) increase.

(a–d): The positive relationship between individuals’ autonomy and their work motivation is enhanced as religious affiliation (a), political participation (b), humane orientation (c), and in-group collectivism (d) increase.

(a–d): The positive relationship between individuals’ social relatedness and their work motivation is enhanced as religious affiliation (a), political participation (b), humane orientation (c), and in-group collectivism (d) increase.

3.1. Sample