- Bibliography

- More Referencing guides Blog Automated transliteration Relevant bibliographies by topics

- Automated transliteration

- Relevant bibliographies by topics

- Referencing guides

The use of mobile applications in higher education classes: a comparative pilot study of the students’ perceptions and real usage

- David Manuel Duarte Oliveira ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8763-6997 1 ,

- Luís Pedro 1 &

- Carlos Santos 1

Smart Learning Environments volume 8 , Article number: 14 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

6 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper was developed within the scope of a PhD thesis that intends to characterize the use of mobile applications by the students of the University of Aveiro during class time. The main purpose of this paper is to present the results of an initial pilot study that aimed to fine-tune data collection methods in order to gather data that reflected the practices of the use of mobile applications by students in a higher education institution during classes. In this paper we present the context of the pilot, its technological settings, the analysed cases and the discussion and conclusions carried out to gather mobile applications usage data logs from students of an undergraduate degree on Communication Technologies.

Our study gathered data from 77 participants, taking theoretical classes in the Department of Communication and Arts at the University of Aveiro. The research was based on the Grounded Theory method approach aiming to analyse the logs from the access points of the University. With the collected data, a profile of the use of mobile devices during classes was drawn.

The preliminary findings suggest that the use of apps during the theoretical classes of the Department of Communication and Art is quite high and that the most used apps are Social networks like Facebook and Instagram. During this pilot the accesses during theoretical classes corresponded to approximately 11,177 accesses per student. We also concluded that the students agree that accessing applications can distract them during these classes and that they have a misperception about their use of online applications during classes, as the usage time is, in fact, more intensive than what participants reported.

Introduction

The use of mobile devices by higher education students has grown in the last years (GMI, 2019 ). Technological advancements are also pushing society with consequent rapidly changing environments. Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are not exempted from these technological changes and advancements, and it is compulsory that they follow this technological evolution so that the teaching-learning process is improved and enriched.

HEI’s are trying to integrate digital devices such as mobile phones and tablets, and informal learning situations, assuming that the use of these technologies may result in a different learning approach and increase students’ motivation and proficiency (Aagaard, 2015 ).

In a study by Magda, & Aslanian ( 2018 ), students report that they access course documents and communicate with the faculty via their mobile devices, such as smartphones. Over 40% say they perform searches for reports and access institutions E-Learning systems via mobile devices (Magda, & Aslanian, 2018 ). The EDUCAUSE Horizon Report - 2019 Higher Education Edition (Alexander et al., 2019 ) also mentions M-Learning as the main development in the use of technology in higher education. However, teachers believe students use their gadgets less than they actually do, and mobile devices also challenge teaching practices. Students use devices for off-task (Jesse, 2015 ) or parallel activities and there may be inaccurate references to their actual use of mobile devices.

Mobile device users have very different usage habits of their devices and their applications, and it is important to study and characterize these behaviours in different contexts, as explained below. The reports that usually support these studies are made with questions directed to the users themselves asking them questions about the apps they have on the devices and the reasons for using them. However, Gerpott & Thomas ( 2014 ) argue that other types of studies are needed to properly support this type of research.

Studies are usually conducted in organizations, based on the opinion of the participants, and cannot be replicated and generalized, for example, regarding the use of the internet or mobile applications by the general public, because these devices, unlike desktop devices, can be used anywhere and at any time (Gerpott & Thomas, 2014 ).

Furthermore, in mobile contexts, it becomes difficult for people to remember what they have used, because mobile applications can be used for various tasks, in various contexts, whether professional or personal, and the variety of applications, the use made, the periods of use are usually so wide and differentiated, that it can become difficult for users to refer which services or applications they have used, under which circumstances and how often. (Boase & Ling, 2013 ).

Thus, it is relevant, for several areas and especially for this research area, to have studies that cross-reference reported usage with actual usage. One of the ways to achieve this is with the use of logs of the use of mobile devices and applications, as mentioned by De Reuver & Bouwman ( 2015 ):

Using this approach this pilot study aims to create and validate a methodology:

i) to show the profile of these users,

ii) to reveal the kind of applications they use in the classroom and when they are in the institutions,

iii) and also, to compare the users’ perceptions with the real use of mobile applications.

Knowing the real usage and the usage students mention may provide valuable insights to teachers and HEIs and use this data for decision making about institutional applications to support students and teachers in their teaching and learning activities. Such information can also bring insights on the integration of M-Learning strategies, promoting interaction, communication, access to courses and the completion of assignments using students’ devices.

The central focus of this study is, therefore, to show preliminary results of the use of applications by students in class time during theoretical classes, through logs collected during class time.

The paper is divided into five parts. In the first part, relevant theoretical considerations are addressed, having in mind the current state of the art in terms of the literature and empirical work in this field. The second part outlines the study methodology. In the third part, the technological setting is highlighted. The cases and the results of the data analysis are described in the fourth part. Lastly, the results are interpreted, connected and crossed with the preliminary considerations.

Literature review

The massive use of mobile devices has created new forms of social interaction, significantly reducing the spatial difficulties that could exist, and today people can be reached and connected anytime and anywhere (Monteiro et al., 2017 ). This also applies to the school environment, where students bring small devices (smartphones, tablets and e-book readers) with them, which, thanks to easy access to an Internet connection, keep them permanently connected, even during classes.

In HEIs there is also a growing tendency among members of the academic community to use mobile devices in their daily activities (Oliveira et al., 2017 ), and students expect these devices to be an integral part of their academic tasks, too (Dobbin et al., 2011 ). A great number of users take advantage of mobile devices to search information and, since they do not always have computers available, these devices allow them an easy access to academic and institutional information (Vicente, 2013 ).

One of the challenges educational institutions face today has to do with the ubiquitous character of these devices and with finding ways in which they can be useful for learning, thus approaching a new educational paradigm: Mobile Learning (M-Learning) (Ryu & Parsons, 2008 ).

M-learning allows learning to take place in multiple places, in several ways and when the learner wants to learn. As learning does not necessarily have to occur within school buildings and schedules, M-Learning reduces the limitations of learning confined to the classroom (Sharples, M., Corlett, D. & Westmancott, 2002 ), leading UNESCO to consider that M-Learning, in fact, increases the reach of education and may promote equality in education (UNESCO, 2013 ). The EDUCAUSE Horizon Report - 2019 Higher Education Edition (Alexander et al., 2019 ) also mentions M-Learning as the main development in the use of technology in higher education and, therefore, it becomes increasingly relevant to rethink learning spaces in a more open perspective, both physically and methodologically, namely through mobile learning that places the student at the centre of the learning process.

Quite often studies that intend to determine the use of mobile applications focus on general questions, but the most common ones are related to the frequency and duration of the use of these devices, for example, questions such as “how many SMS or calls are made?” or “how often do you use the device?”

In fact, instruments like questionnaires are widely used in this type of studies. However, since mobile devices are completely integrated in our daily life and we use them quite extensively, it is difficult to retain and define with plausible accuracy the actual use that we make of them.

It is therefore relevant to effectively understand how these students use these devices, more specifically the applications installed on them. To this end, most studies have been based on designs that are focused on the users’ perceptions and based are on these reports.

Thus, it was important to understand if what users report using corresponds to what they actually use, and if this use does not occur for distraction or entertainment, for example.

Considering the above, some studies have focused on the validity of the use of these instruments. One of these first studies, carried out by Parslow et al. ( 2003 ), aimed at determining the number of calls made and received in the days, weeks or months preceding the date of the questionnaire, and their duration. The answers were compared with the logs of the operators and it was concluded that self-report questionnaires do not always represent the actual pattern of use.

Finally, in self-report instruments, which refer to questions of daily activity on mobile devices, this activity may not represent a general pattern of activity, since from individual to individual the patterns of daily use may vary considerably and thus reflect a very irregular use.

In a study by Boase & Ling ( 2013 ), the authors mentioned that about 40% of studies on mobile device use, based on articles published in journals (41 articles between 2003 and 2010), are based on questionnaires.

The questions asked aim to estimate how long or what type of use they have made of their devices on a daily basis, and sometimes aim to know about time periods of several days. In most of these studies, 40% of papers use at least one measure of frequency of use and 27% a measure of duration of use that users make. Another factor that is mentioned is that users do not always report their usage completely accurately. On the other hand, the same study mentions that users may over or under report the use they make for reasons of sociability (Boase & Ling, 2013 ).

Given the moderate correlation between self-report instruments and data from records or logs (Boase & Ling, 2013 ), the author considers that researchers can significantly improve the results if they use, together with other instruments, data from logs to make their studies more accurate and rigorous. Another suggestion would be the use of mobile applications that record these usage behaviours (Raento et al., 2009 ).

Indeed, this kind of instrument is widely used in this type of studies. However, given that mobile devices are fully integrated into our daily lives and we use them quite extensively, it becomes difficult to retain and define with plausible accuracy the use we make of them. In addition to the factors mentioned in the previous paragraph, it is important that these types of studies are validated with other methods, such as the use of logs, as presented in this study. The logs in this study refer to the capture records of the mobile device traffic made by the students.

This article therefore aims to present preliminary results with an approach that uses cross-checking of log data with questionnaire results.

Methodology

This article intends to present and discuss preliminary results of a study that aims to characterize the use of mobile applications at the University of Aveiro through collected logs, crossing its results with questionnaires answered by students during the classes, and also with an observation grid with data from the analysed class and questions to teachers related to what teachers recommend regarding the use of mobile phones during class time.

The research question that motivated this article is: which digital applications/services are most frequently used on mobile devices by the students of the University of Aveiro during their classes?

The study was composed of 40 students, that answered the questionnaires.

The research was based on the Grounded Theory method aiming to analyse the logs from the access points of the University. With the collected data, a usage profile of mobile devices during classes was drawn.

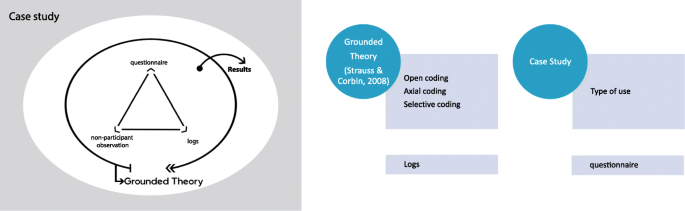

Figure 1 presents a diagrammatic representation of the created methodological process.

General diagram of the study

Therefore 3 instruments were used for the data collection: a questionnaire, an observation grid and logs collected through mobile traffic in the wi-fi network of the university.

The questionnaire allowed for a quantitative assessment of the profile of the participants and collected data on the use that participants claimed to make of their mobile devices. The observation grid served as a guide for the implementation of the study, allowing to record data on the classes where the collections took place and to verify whether certain items were present, such as permission to use mobile devices or planning to use them by teachers. The observation grid would also serve to make the link between use and content in class, but in this pilot, it was not possible to make this link between the class content and the usage of mobile applications, because the author could not observe the applications used by students.

The database containing the usage records enabled the analysis of the logs, resulting in the quantification and verification of the type of activity that each (anonymous) participant made of their device.

The 3 instruments used aimed to i) determine which application(s) students were really using during the classes, through the analysis of the data logs collected from the Wi-Fi network of the University; ii) identify the participants’ representations of their activities by means of several questions regarding mobile usage during class time; iii) observe students’ behaviour and focus via an observation grid that was used by the researcher/observer when he was attending the classes.

The group who participated in this pilot study was selected in accordance with the professors and classes available, so it is considered a convenience sample. The group was constituted by students of undergraduate classes from the Communication and Arts Department of the University of Aveiro.

Table 1 summarizes the schedule of the pilots carried out, the curricular units where they took place, their duration and the instruments used. For ease of management, all the pilots took place in the same department of the University.

The Table 2 summarizes the collected data from questionnaires and logs.

This pilot aimed to build an approach to data analysis, close to the Grounded Theory methodology, in which a provisional theory is built based on the observed and analysed data (Alves et al., 2017 ; Long et al., 1993 ). The data collected in this pilot will serve to define a more complete methodology to be used in a larger study.

This chapter is divided into three parts: context, technological setting and cases analysed. In the context part, the classes which are part of the study will be described, relating the answers from the questionnaires with the teachers’ recommendations about the use of mobile devices. In the technological scenario section, it is intended to describe the technological background underlying the collection process of the logs and in the last part, analysed cases, the objective was to validate if the data to be collected matched the outlined objectives.

In the questionnaire, the questions were divided into two main groups: aspects related to the participant’s profile and aspects directly related to the use of the applications. Aspects related to participants were intended to characterize them. Regarding the use of applications, we aimed to find out the students’ perception of the applications they use in their daily routine, inside and outside of the classroom, and how they do it. Data were collected using a Google Forms form and processed using Microsoft Excel.

In this subchapter, through the data collected from the students’ answers to the questionnaires, and by crossing this information with the data collected from the teachers in the observation grid, we try to describe the context of the pilot.

All of the teachers stated that they allowed their students to use mobile phones during class time, but that they did not plan that use. They also stated that in most part of the classes several students use their mobile phones and apps to search for class related materials. The teachers also showed curiosity about knowing, with more detail, the mobile phone use their students actually have.

In the three classes analysed (Aesthetics, Scriptwriting and Music in History and Culture), when asked about the possibility of using mobile applications as a pedagogical complementary resource 43%, 47% and 55% of students fully agreed that these should be used. In these three classes, 31%, 44%, and 67% of students showed a more moderate opinion: they agreed (but not in such an assertive way) that these should be used.

Another conclusion is that most of the students used a smartphone (88,9%, 75%, 52%) during class time, but many of them also used a computer (66,7%, 100%, 84%). The percentage use of tablets is much lower (11,1%, 0%, 15%).

In the analysed scenario, the majority of the students used the android operating system and 94% also agreed that mobile applications could help to manage the academic tasks, except in the case of the “Aesthetics Curricular Unit”.

When it comes to the time of use, per week, in classes, 53%, 58%, and 22% of the students answered they used these devices between 4 to 5 days a week and 15%, 40% and 70% said they used them between 1 to 3 days a week.

Students were also asked about how frequently they accessed mobile applications during class time and, in all, 77% of the respondents reported accessing apps at least between 1 to 5 times per class. About 20% referred they accessed apps from 6 to 10 times per class.

As for the purposes of accessing apps during classes, most students mentioned categories related i) to support the class / to research (70%, 100%, 77,8%), ii) to access institutional platforms (47.4%, 66.7%, 89, 9%), iii) to access to information (47.4%, 50%, 66.7%) and iv) to work (36.8%, 50%, 44.4%).

Interestingly, the categories communication (52.6%, 41.7%, 22.3%), collaboration (10.5%, 16.7%, 0%), access to institutional services (5.3%, 0% 0%) and “I do not use them” (10.5%, 0%, 0%) presented very low percentages, namely the last one.

When questioned about the use of mobile devices that did not include academic reasons, many students referred to the categories “to be linked/connected” or “to be updated” (42.1%, 66.7%, 33.3%), “to communicate” (57.7% 75.7%, 66.7%), “to share and access content” (31.6%, 58.3%, 33.3%), but few mentioned “for entertainment” (26.3%, 16.7%, 22.2%), “as a habit or routine” (10.5%, 41.7%, 11.1%) and “I do not use them” (10.5%, 0%, 11.1%).

When asked about which mobile applications are most used in an academic context, the most relevant category was “to research / to study” (73.7%, 58.3%, 89.9%), “to check the calendar” (31.6%, 25%, 66.7% %) and “to surf the web” (47.4%, 50%, 55.6%). Again, categories such as “to work” (36.8%, 33.3%, 33.3%), “to take notes” (26,2%, 33.3%, 55.6%) and “to create content” (31.6%, 25%, 11.1%) presented relatively low percentages. It should also be noted that the respondents presented answers that created categories which were not expected such as “to watch films” (10.5%, 8.3%, 0%), “to listen to music” (31.6%, 33.3%, 33.3%), “to take photos” (10.5%, 0%, 0%) and “to play games” (5.3%, 0%, 0%) All the students said that they used applications during classes in at least one of the categories. In fact, in the three courses no one stated “not to use them” (0% in all).

When asked about the teachers’ permission to use the mobile devices in the classroom, most of the students said that teachers allowed free use (52.6%, 100%, 77.8%). Only a few stated that teachers allowed using them specifically when planned (41, 1%, 0%, 22.2%). The respondents of one course stated that teachers did not allow the use of devices (Aesthetics - 5.3%). Finally, when asked about the usefulness of integrating mobile applications in class, there was an overwhelming majority of respondents (100%, 78,9%, 100%) saying they believed that such integration could be enriching and useful.

Below is presented a table describing the most used mobile apps during class activities. It should be noted that only the two answers with the greatest relevance for each category were considered.

Table 3 systematizes what the results have been showing until now: there is an important part of students that use mobile phones during their classes and, even when teachers advise them not to use them, they ignore the recommendations and use them anyway. The main purposes stated were: to be in contact with others through social networking but also to access different kinds of information in browsers. Moreover, the classes where the use of devices is not recommended by the teachers seems to be the one where some applications are most used.

Technological setting

In this section we intend to describe the technological background underlying the process of collecting the logs. The first goal was to register and capture logs from the wi-fi network of the university, which consists of a wireless network that users can access using their universal user credentials.

In order to do that a meeting was scheduled with the university’s technology services, as our main concern was the anonymization of the data collected in order (i) to confer more neutrality to the data treatment, and (ii) to comply with European data protection legislation. Another issue for discussion was the need of powerful machines so that they could process the large amount of data collected.

In this meeting the necessary steps were agreed in order to guarantee the users’ privacy, the authorization of the university’s central services to do the study and the registration method of the logs. The overall procedure demanded several experiences of data collection to fine-tune the final pilot, which works as the basis capture setting for all the main study.

The Wi-Fi traffic capture software (Wireshark) was selected to work both with Android and IOS devices and it was possible to understand the functionalities of the software.

The pilot also helped to understand and solve additional problems that appeared during the previous tests, related to the anonymization of the users’ data. It was necessary to ensure that the users’ personal data were not identifiable, which was a commitment: in fact, only HTTPS Footnote 1 traffic was captured, being all the other information encrypted.

After the first tests, an initial data collection pilot took place in a classroom context. A specific capture system was created to allow the capture of mobile application logs used only by a certain group of students, from a designated Curricular Unit. A specific scenario was set up to ensure that only those students communicating through the IP Footnote 2 defined for the scenario and during that class time were considered and treated under the scope of this study:

If the traffic of the concerned student is communicating through one of the APs (Access Points) covering the room, then the device will be assigned a “Room network” IP;

If the student’s traffic is not communicating through one of the APs covering the room, then the device will be assigned a “Non Room network” IP;

If the student traffic does not belong to the group to be analysed and the device in question is communicating through one of the APs covering the room, then the device will be assigned an IP from a “normal eduroam network”;

In the final steps we resolved the IP’s in Wireshark (software used for the capture) and the unsolved IP’s where filtered in a PHP Footnote 3 script, through the gethostbyaddr method where the unsolved ones are incrementally added.

Finally, using an IP list, we performed a comparison to resolve any unresolved names;

This step allowed to fine tune the process and to make the final test.

Analysed cases

After performing these tests, a scenario for this final pilot was set up to validate if the data to be collected matched the outlined objectives. In this final pilot, logs were collected in a classroom so that the scenario was as close to the desired collection as possible. In this pilot, it was possible to verify that the collected data fulfilled the requirements. At this point, in addition to the HTTPS traffic packets, the packets referring to DNS Footnote 4 traffic were also included. This option made the HTTPS traffic more easily understandable. Furthermore, the researcher could conclude that all authenticated devices belonged to separate accounts.

The results show that the pre-tests/pilots and the final pilot turned out very well and in a very reliable way since they allowed to verify the main problems that could occur and helped to certify that the traffic anonymity condition was respected. In fact, only the HTTPS was considered, and all other communication was encrypted with no risk of corruption of private data. Moreover, this option had an important justification: the fact that HTTPS traffic could be more easily understandable and the fact that it allowed certifying that all the authenticated devices of the wireless network belonged to separate accounts.

To process and create output visualization of the data, the choice was an integrated solution, both for the processing stage and for creating visualisations. Given the variety of tools available, several were tried out and Tableau Software® (Tableau Prep® and Tableau Desktop®) was chosen. Tableau Software is an interactive data processing and visualisation tool that belongs to the Salesforce company and, although it is paid software, it allows for an academic licence that was used in this project.

This solution, besides allowing working with a large amount of data, also allows for a very interactive data treatment and visualisation. This software also allows the importation of data from various sources, which in the case of this study was also an advantage.

This solution allowed us to work with large amounts of data but it also allowed for a very interactive data treatment and visualization. In the case of Tableau Prep, the file with the logs was imported in a CSV format Footnote 5 and treated iteratively in a dynamic way, being refined to the desired data in a second stage. As an example, we can mention the separation of the field “time duration” in hours, minutes and seconds fields; all the IPs were converted to a generic name “student”; all the destinations visited by the students were grouped in main categories, as for instance “Facebook”, as each application had numerous distinct destinations.

About 30 changes in data treatment and in data flow “cleaning” were performed, which were, later, exported to Tableau Desktop. Each file imported to Tableau Prep, in addition to the changes applied to the previous file, was refined with more changes, in an iterative process.

After treating the data on Tableau prep the generated data flow was imported to Tableau Desktop so that dynamic data visualizations were created. At this stage, dimensions, measurements, and filters were created according to the desired data visualization. The software has the big advantage of creating dynamic visualizations of the logs’ data which allows for a different and richer perspective on the data obtained, in order to deepen further studies about the same topic.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper aimed to describe the process of a pilot to carry out a larger study where we wanted to cross-reference actual usage data (logs) of mobile applications in the classroom with data from student questionnaires. In this article we also present the main results of this pilot, both from the point of view of the process of the pilot and from the point of view of the data of use of mobile applications by students in the classroom.

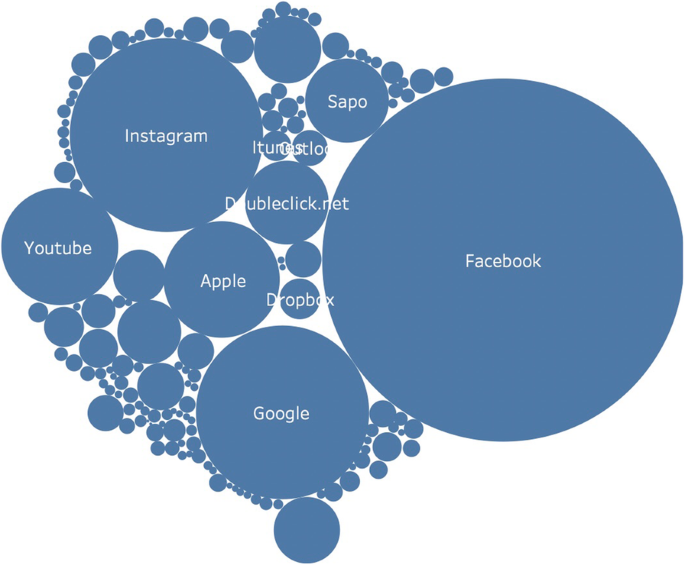

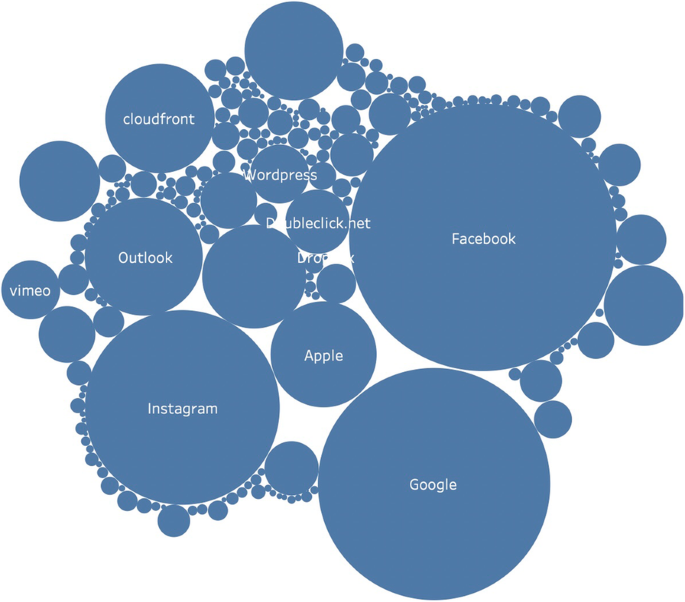

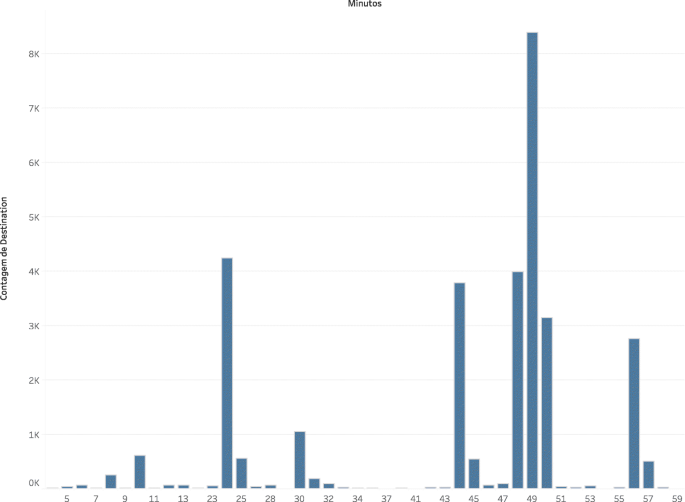

From the preliminary data analysis of this pilot, we can infer that the most used apps are Facebook, Google and Instagram, as we can see in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 , although some variations between the attendees of the courses were registered when it comes to other apps. For example, in the case of the Design course, there are alternative apps being used such as YouTube or Vimeo.

General use of applications in Scriptwriting class

General use of applications in Aesthetics classe

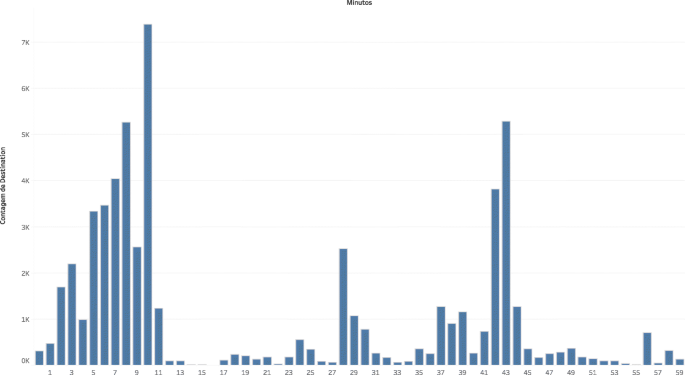

Another noticeable preliminary result is that students use Facebook more at the beginning of classes and Instagram is used more at the end, as we can see in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 .

Use of Facebook per hour in Scriptwriting class

Use of Instagram per hour in Scriptwriting class

In addition, the developed model was used in the main study with a bigger convenience sampling approach, which may provide a more accurate representation of the population of mobile-phone-users in the study field.

The visualizations created in a dynamic way during this study showed that the use of logs as a complementary data provider to other instruments, such as questionnaires, can be an added value for this research field.

On the other hand, this pilot contradicts (sometimes slightly, others considerably) the results of the questionnaires answered by the students and whose logs were collected and analysed. Logs show that:

there is a common use of mobile applications during the classes;

the purpose of the access is different: participants report that they use mobile applications mostly for academic reasons, but it can be noted that there is a general use of other mobile applications such as social networks and Youtube;

the usage time is much longer than what participants reported;

the frequency is also different: students stated that they use mobile applications in classes only 1–3 days a week, but we found that, in the analysed classes, there is an almost constant use of them, and finally

students report that they do not use social networks much in class, but the use is, in fact, massive.

The students’ perception of the “use of mobile devices and applications during lessons”, and as already mentioned, during a teaching activity - 70% of the students refer using the applications between 1 to 5 times, 22% between 6 to 10 times and 4% more than 10 times. It should also be noted, as previously mentioned, that only 4% mention not using them. With regards to the use during the week, 56% of the students refer using them between 4 to 5 days per week and 39% between 1 to 3 days per week. There is also a relatively low percentage of students mentioning that they use the devices during class more than ten times (4%).

However, analysis of the logs shows that this use appears to be much more intensive. We performed a calculation based on the average number of accesses, from which we removed 40% of potential automatic accesses and divided by the average number of accesses each application had in the initial test. The results present 6.6 accesses to the device per class/student in the class with the fewest accesses, and for the highest case, 313 accesses to the device per class/student.

This result is reinforced by results from other studies, such as the Mobile Survey Report, which states that students make regular use of laptops and smartphones during lessons (Seilhamer et al., 2018 ).

These conclusions lead us to some very serious insights on this subject. Apparently, even older students have a misperception of their use of online applications during classes. There is a serious discrepancy and incongruency between the behaviours that they claim to adopt and those they actually engage in during the classes. There are authors, who argue for the need for other types of studies that support this type of approach (Gerpott & Thomas, 2014 ), because the perception reported by users may not correspond to the actual use. It means that this gap deserves a deeper reflection. Why does it happen? Are students not motivated in higher education? Is the world offered online more interesting than the one in the physical campus? We will try to answer these questions in the main study.

Availability of data and materials

Some of the visualizations created are publicly available at https://public.tableau.com/profile/davidoliveiraua

HTTPS It is a protocol used for secure communication over a computer network, and is widely used on the Internet

IP is the s a numerical label assigned to each device connected to a computer network that uses the Internet Protocol for communication

PHP is a general-purpose scripting language especially suited to web development

DNS is naming system for computers, services, or other resources connected to the Internet

Unformatted file where values are separated by commas

Abbreviations

Higher Education Institutions

Access Points

Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure

Internet Protocol

Hypertext Preprocessor

Domain Name System

Comma-separated values

Aagaard, J. (2015). Drawn to distraction: A qualitative study of off-task use of educational technology, Computers & Education, Elsevier

Alexander, B., Ashford-Rowe, K., Barajas-Murphy, N., Dobbin, G., Knott, J., McCormack, M., Pomerantz, J., Seilhamer, R., & Weber, N. (2019). EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: 2019 Higher Education Edition. https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2019/4/2019horizonreport.pdf?la=en&hash=C8E8D444AF372E705FA1BF9D4FF0DD4CC6F0FDD1

Alves, A. G., Martins, C. A., Pinho, E. S., & Tobias, G. C. (2017). A Teoria Fundamentada em dados como ferramenta de análise em pesquisa qualitativa. 6o Congresso Ibero-Americano Em Investigação Qualitativa - CIAIQ2017, 1, 499–507

Boase, J., & Ling, R. (2013). Measuring Mobile phone use: Self-report versus log data. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 18 (4), 508–519 https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12021 .

Article Google Scholar

De Reuver, M., & Bouwman, H. (2015). Dealing with self-report bias in mobile internet acceptance and usage studies. Information Management , 52 (3), 287–294 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.12.002 .

Dobbin, G., Dahlstrom, E., Arroway, P., & Sheehan, M. C. (2011). Mobile IT in higher education. Educause , 1–33.

Gerpott, T. J. and Thomas, S. (2014) Empirical research on mobile internet usage: A meta- analysis of the literature, telecommunications policy, 38 (3): 291-310. 2014. [online]. Available: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030859611300175Accessed on: Dec., 20, 2016.

GMI. (2019). Mobile Learning Market Size | Global Growth Statistics 2020–2026. https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/mobile-learning-market

Jesse, G. R. (2015). Smartphone and app usage among college students: Using smartphones effectively for social and educational needs. Proceedings of the EDSIG Conference , 2015 , 1–13 http://proc.iscap.info/2015/pdf/3424.pdf

Long, D. R., Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1993). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. The Modern Language Journal , 77(2), 235 https://doi.org/10.2307/328955

Magda, A. J., & Aslanian, C. B. (2018). Online college students 2018. Comprehensive Data on Demands and Preferences. https://www.learninghouse.com/knowledge-center/research-reports/ocs2018/

Monteiro, A., Bento, M., Lencastre, J., Pereira, M., Ramos, A., Osório, A. J., & Silva, B. (2017). Challenges of mobile learning – A comparative study on use of mobile devices in six European schools: Italy, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Turkey. Revista de Estudios e Investigación En Psicología y Educación , 13 , 352. https://doi.org/10.17979/reipe.2017.0.13.3229 –357.

Oliveira, D., Tavares, R., & Laranjeiro, D. (2017). Estudo de avaliação de aplicações móveis de instituições de ensino superior português. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307981176

Parslow, R. C., Hepworth, S. J., & McKinney, P. A. (2003). Recall of past use of mobile phone handsets. Radiat. Prot. Dosim., 106(3), pp. 233–240. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=14690324&site=ehost-live , DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006354

Raento, M., Oulasvirta, A., & Eagle, N. (2009). Smartphones: An emerging tool for social scientists. Sociological Methods & Research , 37 (3), 426–454 https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124108330005 .

Ryu, H., & Parsons, D. (2008). Innovative Mobile learning: Techniques and technologies. Information Science Reference - Imprint of: IGI Publishing.

Seilhamer, R., Chen, B., DeNoyelles, A., Raible, J., Bauer, S., & Salter, A. (2018). 2018 Mobile Survey Report. https://digitallearning.ucf.edu/msi/research/mobile/survey2018/

Sharples, M., Corlett, D. & Westmancott, O. (2002). The design and implementation of a mobile learning platform based on android. Proceedings - 2013 International Conference on Information Science and Cloud Computing Companion, ISCC-C 2013, 345–350. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCC-C.2013.136

UNESCO. (2013). Policy guidelines for mobile learning. In policy guidelines for mobile learning . https://doi.org/ISBN 978-92-3-001143-7. France

Vicente, F. (2013). WelcomeUA: Desenvolvimento de interface e avaliação da usabilidade. 136. https://ria.ua.pt/handle/10773/12403

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no funding in this project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Communication and Arts Department, Universidade de Aveiro, Campus Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193, Aveiro, Portugal

David Manuel Duarte Oliveira, Luís Pedro & Carlos Santos

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

DO wrote the introduction and discussion, and saw to the article structure, wrote the method section and conducted the data analysis. LP and CS conducted the literature review. All authors contributed to the discussion and conclusion sections, and the overall flow of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Manuel Duarte Oliveira .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Oliveira, D.M.D., Pedro, L. & Santos, C. The use of mobile applications in higher education classes: a comparative pilot study of the students’ perceptions and real usage. Smart Learn. Environ. 8 , 14 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-021-00159-6

Download citation

Received : 20 January 2021

Accepted : 16 July 2021

Published : 09 August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-021-00159-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mobile application

- Mobile usage

- Higher education

- Open access

- Published: 02 October 2023

Design and development of a mobile-based self-care application for patients with depression and anxiety disorders

- Khadijeh Moulaei 1 ,

- Kambiz Bahaadinbeigy 2 ,

- Esmat Mashoof 3 &

- Fatemeh Dinari 2

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making volume 23 , Article number: 199 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3134 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Background and Aim

Depression and anxiety can cause social, behavioral, occupational, and functional impairments if not controlled and managed. Mobile-based self-care applications can play an essential and effective role in controlling and reducing the effects of anxiety disorders and depression. The aim of this study was to design and develop a mobile-based self-care application for patients with depression and anxiety disorders with the goal of enhancing their mental health and overall well-being.

Materials and methods

In this study we designed a mobile-based application for self -management of depression and anxiety disorders. In order to design this application, first the education- informational needs and capabilities were identified through a systematic review. Then, according to 20 patients with depression and anxiety, this education-informational needs and application capabilities were approved. In the next step, the application was designed.

In the first step, 80 education-information needs and capabilities were identified. Finally, in the second step, of 80 education- informational needs and capabilities, 68 needs and capabilities with a mean greater than and equal to 3.75 (75%) were considered in application design. Disease control and management, drug management, nutrition and diet management, recording clinical records, communicating with physicians and other patients, reminding appointments, how to improve lifestyle, quitting smoking and reducing alcohol consumption, educational content, sedation instructions, introducing health care centers for depression and anxiety treatment and recording activities, personal goals and habits in a diary were the most important features of this application.

The designed application can encourage patients with depression and stress to perform self-care processes and access necessary information without searching the Internet.

Peer Review reports

Depressive and anxiety disorders are significant contributors to worldwide disability [ 1 ] affecting up to 25% of general practice patients [ 2 ]. Normally, these disorders may not be as “brain disorders,“ but they do interfere with normal cognitive, emotional, and self-reflective functions [ 3 ]. Brain disorders include any conditions or disabilities that affect the brain [ 4 , 5 ]. These disorders, caused by factors such as disease, genetics, or traumatic damage, encompass a range of conditions, including brain injuries, brain tumors, neurological diseases, as well as mental disorders like depression and anxiety [ 6 , 7 ]. Depression and anxiety due to their nature always cause social, occupational and functional harm [ 8 ]. Studies have shown that if depression and anxiety are not treated, controlled and / or managed, they can lead to poor quality of life [ 9 ], increased risk of suicide [ 10 , 11 ], job loss due to frequent absences [ 12 ], and premature mortality, persistent fatigue, sad and angry mood, decreased self-esteem and ability to perform daily activities, and increased risk of hospitalization [ 13 ]. On the other hand, due to the stigma associated with depressive and anxiety disorders, people are often reluctant to seek consultation and medication, which can hinder their access to effective psychological therapies [ 14 ]. One of the most effective ways to treat, control and / or manage these two disorders is self-care. Self-care as an independent factor can reduce the risk of disease complications [ 15 ].

Self-care processes help patients to control emotions, adhere to treatment, understand the treatment rationale, improve quality of life, reduce stress and anxiety, feel more secure, and increase life satisfaction. Also, these processes will ultimately maintain physical and mental health, reduce mortality, reduce health care costs, increase patient satisfaction and improve patients’ quality of life [ 16 ]. Mobile -based applications can be used as a platform for self-care services [ 17 ]. Mobile applications have become an all-encompassing tool for helping people to manage and control anxiety and depression symptoms [ 18 ], provide quick and easy access to health information, and improve interaction with therapists [ 19 ]. In other words, applications can aid people in managing their health, promoting a healthy lifestyle, and providing accurate information when and where it’s needed. Encouraging findings have been reported regarding the effectiveness of mobile-based applications for addressing depression and anxiety [ 20 ]. Lattie et al. [ 21 ] investigate the role of digital health interventions in improving depression and anxiety among students and concluded that applications are effective as computer, web, and virtual reality-based interventions in improving depression and anxiety. Almodovar et al. [ 22 ] also showed that mobile applications can increase self-confidence in coping skills and improve depressive and anxiety disorders.

To our knowledge, various studies have been done on the design and development of mobile apps to manage and control anxiety and depression. These applications have different capabilities, including patient monitoring, symptom tracking, emotional support, telecounseling, online training, medication reminders, BMI calculator, reporting and meditation management [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. It should be noted that: none of these applications have all the features introduced in our study and only have some of these characteristics [ 23 , 24 , 25 ], for example, the 7 Cups of Tea application does not provide the possibility of interacting with the health care provider [ 26 ], and the language of these applications is not Farsi. Therefore, Iranian patients with stress and anxiety could not use these applications. Therefore, in the present study, we designed and developed a mobile-based self-care application for patients with depression and anxiety disorders. In this study, we answer the following three questions:

What are the necessary capabilities and educational-informational needs of patients for designing a mobile-based self-care application through a literature review?

What are the capabilities and educational-informational needs of patients for designing a mobile-based self-care application, considering the perspectives and opinions of patients with depression and anxiety?

How is the application designed and what features does it have?

The present study is a developmental-applied study that was conducted in the following three stages.

Stage 1: identify the capabilities and education- information needs of patients to design the application

According to various studies [ 17 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ], the first step in designing a mobile-based application is to identify information needs and necessary capabilities. These information needs and capabilities can be identified through a literature review [ 17 , 29 , 31 ], holding a panel of experts [ 28 ], focus groups with the end users [ 30 ], or interviewing target users [ 27 ]. In the first step of our study, patients’ information-educational needs and application capabilities were identified by literature review on January 1, 2022, from PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus databases. For this purpose, the following search strategy was used.

(Depression OR anxiety) AND (mobile-Based self-care application OR mobile-based Self-management application).

Inclusion criteria consisted of articles published in English, having access to the full text, and containing relevant information on the required information-educational needs and capabilities for designing the application. Exclusion criteria encompassed articles that did not provide clear information about self-care for anxiety and depression disorders through applications. The study excluded books, book chapters, letters to the editor, and conference abstracts.

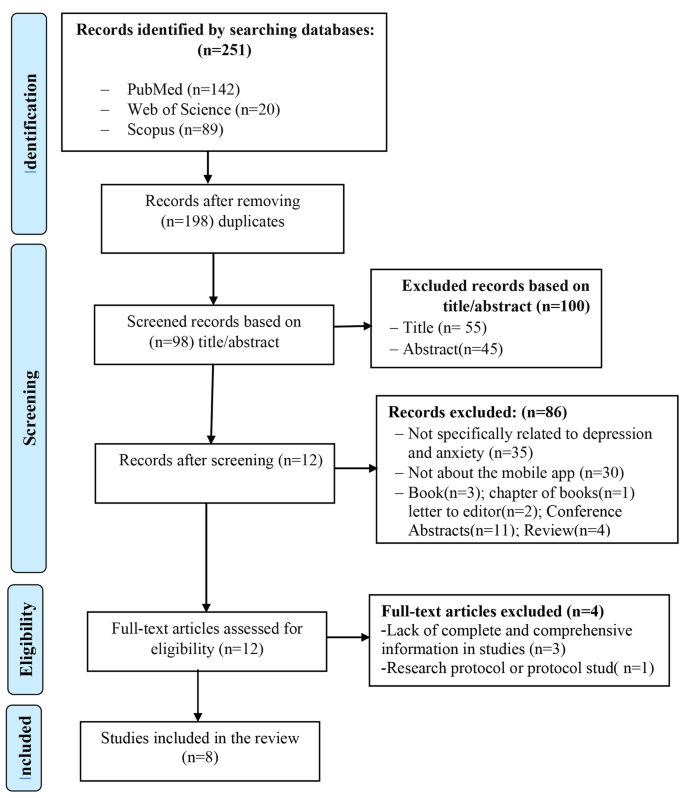

Related articles were retrieved from the three introduced databases and entered into Endnote software. Two hundred and fifty-one articles were extracted from three databases: PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus. One hundred and forty-two studies from PubMed, 89 studies from Scopus and 20 study from Web of Science were retrieved. Four duplicate articles were excluded from the study. Then, 98 remaining sources were carefully examined and compared with inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, the titles, abstracts and keywords of all articles were studied. Finally, 8 articles were included in the study (Fig. 1 ) [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. We studied the full text of these articles and extracted the necessary data elements for designing and developing applications. Data collection was carried out using a data extraction form, and its validity was confirmed based on the opinions of two medical informatics and two psychiatric specialists.

Selection of studies based on the PRISMA flowchart

Stage 2: confirm the capabilities and education- informational needs to design the application

At this stage, the data collection tool was a questionnaire designed based on the educational information needs and capabilities identified in the previous stage. The questionnaire consisted of six parts, with the first part focusing on demographic information (4 questions). The second part: education-informational needs and capabilities in six parts: user profile (8 questions), clinical history (9 questions), lifestyle (14 questions), disease management and control (28 questions), sedation instructions (10 questions), and application capabilities (16 questions). Also, for each part of the questionnaire, an open-ended question was mentioned under the heading “Other cases”. The Content Validity Ratio (CVR) was employed to assess the questionnaire’s content validity. Two medical informatics and three psychiatric specialists completed the questionnaire to calculate the CVR. These people had the experience of conducting various researches in the field of anxiety and stress and collaborating in the design of self-care applications. In order to calculate the CVR, the expert panel was instructed to rate each question using a three-point scale: “essential,“ “helpful but not essential,“ and “not essential” [ 17 , 40 ]. Afterward, the CVR was determined utilizing the subsequent formula:

n represents the count of experts choosing the “essential” option, while N represents the total number of experts.

As per Lawshe’s criteria for CVR, when the expert panel consists of five members, the minimum acceptable value for each item is 0.99 [ 40 ]. In this research, the minimum acceptable CVR value for each question, as determined by the experts, was 1.00. Additionally, the overall CVR ratio was computed as 1.00.

Moreover, the reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated by Cronbach’s alpha and was confirmed with a value of 0.902 (Appendix A). Sampling was not performed at this stage, and all patients with depression and anxiety (40 patients) referred to the Hamzeh Medical Center affiliated to Fasa University of Medical Sciences (Fasa city, Iran) from December 2021-December 2022 were included in the study. It should be noted that during this period of time, 510 patients with psychiatric disorders had referred to this center, 40 of them were suffering from depression and anxiety. In order to participate, an invitation was sent to all of these patients. Thirty people accepted the invitation and finally 20 people entered the study according to the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were:

At least 18 years old.

Having a smart mobile phone literacy.

Declare informed consent to participate in the study.

Do not suffer from acute cognitive and mental disorders except depression and anxiety.

The questionnaire was electronically designed, and its link was sent to patients on January 12, 2022. All questionnaires were completed by January 20. It is worth mentioning that to incentivize participation, each participant received a gift card worth 1,000,000 Iranian Rials for a local grocery store in Fasa city.

The results obtained from the questioner were analyzed by SPSS 23.0. The answers “completely unnecessary”, “unnecessary”, “neutral”, “necessary”, and “completely necessary” with scores from 1 to 5 was given. Also, descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, and standard deviation (SD) were used. In accordance with the opinion of the research team and several psychiatrists, information-educational needs and application capabilities with a mean greater than and equal to 3.75 (75%) were considered to design and develop the application. A cut-off score of 3.75 or higher indicates that only items rated as “necessary”, and “completely necessary” by patients are included in the application design. Other studies [ 17 , 31 , 41 ] related to application design showed that by considering mean greater than and equal to 3.75 (75%) as a cutoff, more important and necessary information-educational needs and capabilities will be selected for application design. As a result, the application will be more efficient and useful.

Stage 3: design and development a prototype of the mobile-based application

At this stage, based on the education-informational needs and capabilities approved in the previous stage, the prototype was designed with the Java programming language in an Android Studio programming environment. SQLite DB was used to design the database. After entering the information and saving it by the patients, the mobile application sends the information to the application database. After the information is saved, they can access stored information, edit it or add new information. Finally, patients can report the information stored in PDF format and send the report to their physicians via social networks or email. During the study, the use of the application was free for patients. Moreover, it should be noted that we did not design a user interface for physicians, and the patient’s communication with physicians will be through social networks and email.

Given the popularity of the Android operating system in Iran, the prototype of this application was specifically designed for Android OS version 4.4 KitKat and higher. Notably, both the application and its database were developed by a Mobile App Design company, ensuring that only the patient can access and share the information stored in the application’s database with their therapist.

Ethical considerations

The code of ethics with the number IR.KMU.REC.1399.025 was obtained from the ethics committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences on March 18, 2020. Patients’ informed consent was obtained before participating in the study. The participation of physicians and patients in the study was also completely voluntary and it was possible for them to leave the study at any time.

Stage one: identify the education- informational needs and capabilities to design the application

An overview of selected studies is presented in Table 1 . Moreover, Fig. 1 shows the search results and the study selection process.

Table 2 shows the demographic information of patient’s participant in stage two of the study. The majority of participants (60%) were female. Most age groups were 31–40 years old. Also, the majority of participants (80%) were suffering from depression and anxiety.

Findings related to education-informational needs and capabilities required for application design included six categories include: user profiles, clinical records, lifestyle, disease management and control, relaxation instructions, and application capabilities (Table 3 ). The importance of each of these education-informational needs and capabilities is presented in Table 3 . Of 80 education-informational needs and capabilities, 68 education-informational needs and capabilities with a larger mean and equal to 3.75 (75%) were considered for application design.

In the user profile, national code, age, weight, education, address and contact number with a mean of less than 3.75 were not included in the application design. In the lifestyle category, underlying diseases and in the application capabilities category, BMI calculation, lectures, relaxing music and games and intellectual puzzles were excluded from the study and were not considered for designing the application.

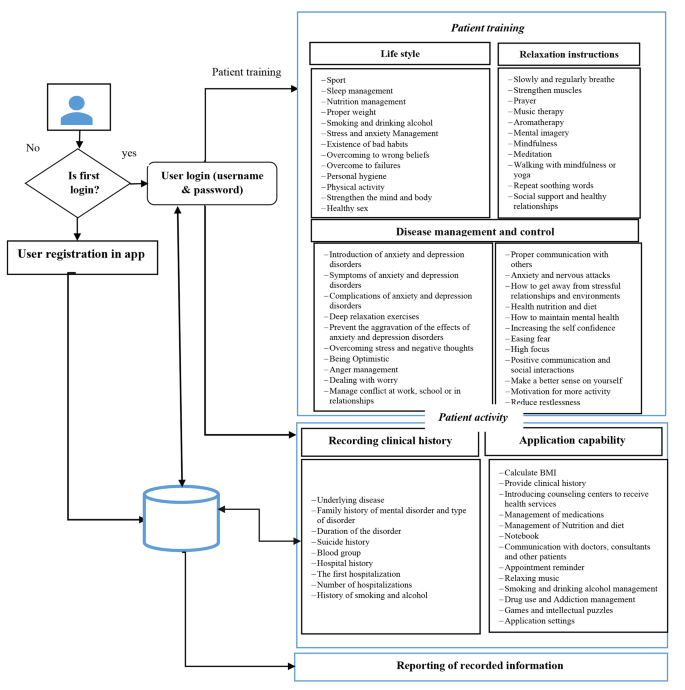

According to the results obtained in the needs assessment stage, a mobile-based self-care application for patients with anxiety and stress disorders was designed with the Java programming language in the Android Studio environment. The architecture of this self -care app is shown in Fig. 2 .

The architecture of the designed mobile self-care application

This application has six main sections namely user profiles, clinical records, lifestyle, disease management and control, relaxation instructions, and application capabilities on the main page of the application (Fig. 3 ). By clicking on each of the icons of these sections, a subset of their related features will be displayed. In total, this application has 20 pages for features of each section: user profiles (1 page), clinical records (2 page), lifestyle (3 page), disease management and control (10 page), relaxation instructions (2 page), and application capabilities (2 page). In the following, each of these sections is described.

In the user profile section, the patient can register after entering the application and by entering a username and password enter the application.

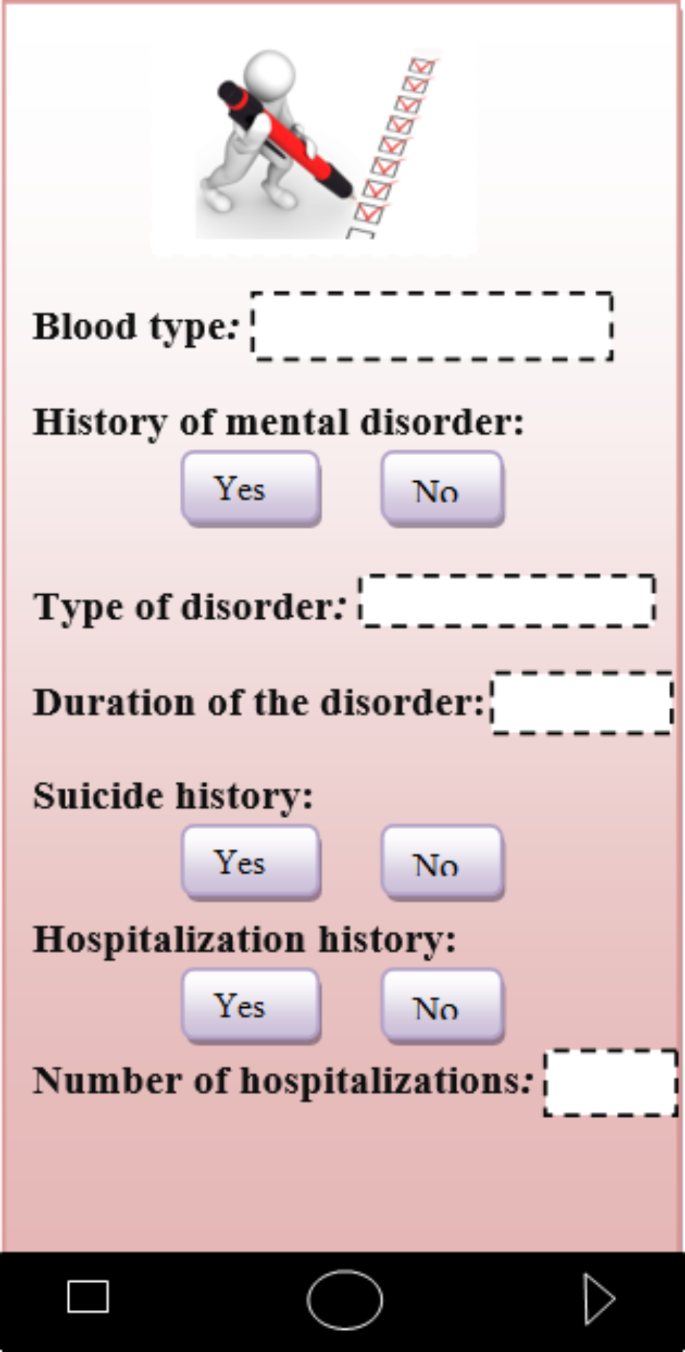

In the clinical history category, the patients can save various information about blood group, family history of mental disorder and type of disorder, duration of the disorder, history of suicide, history of hospitalization, time of first hospitalization, number of hospitalizations and history of smoking and alcohol consumption on their mobile phone and send them to his/her doctor as a pdf file (Fig. 4 ).

In the lifestyle category, educational information in the form of videos and texts related to exercise, sleep, proper nutrition, proper weight, smoking and alcohol, stress and anxiety management, healthy bad habits, how to overcome wrong beliefs, how to overcome failures, personal health, physical activity, mind and body strengthening, healthy sex, social support and healthy relationships are provided.

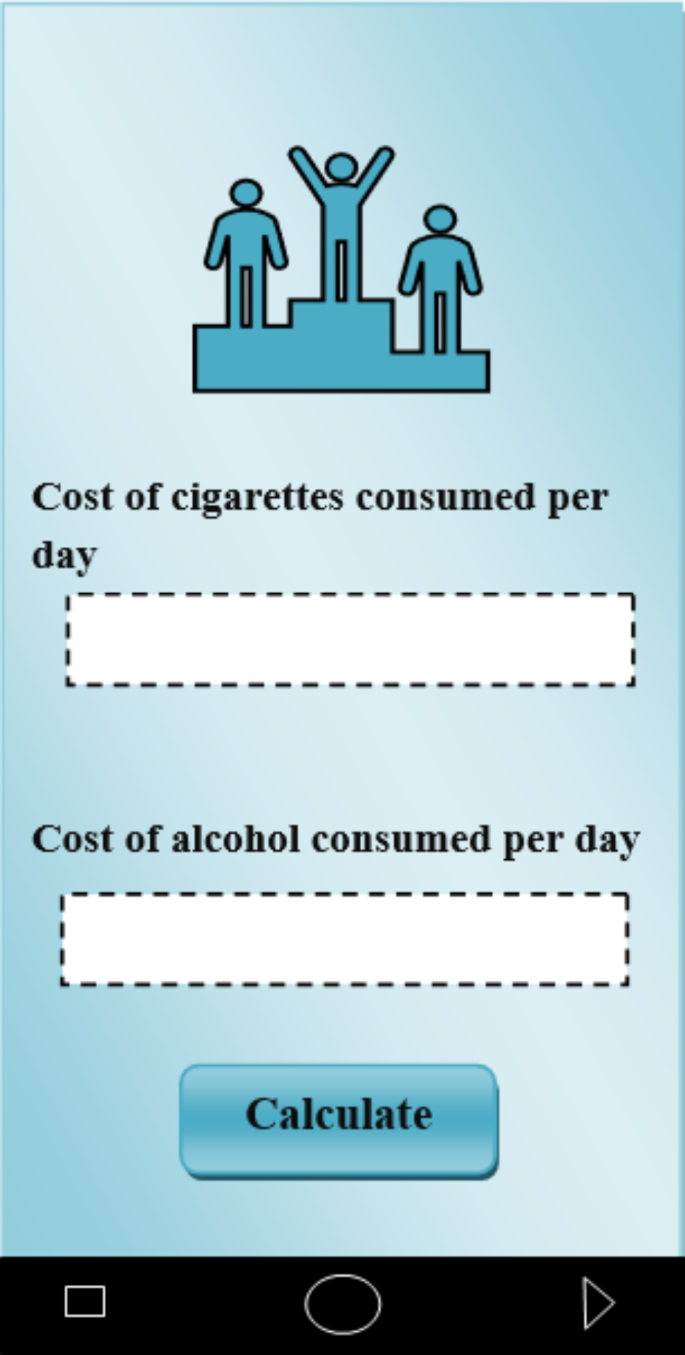

In the disease management and control category, the complications caused by depression and anxiety can be controlled and managed. As an example, part of this application is intended for quitting smoking and alcohol. The patient can enter the days he does not smoke or drink alcohol in the application. Also, enter the cost of cigarettes and alcohol consumed per day and number of cigarettes smoked daily in the application. Then, by clicking on “calculate”, the app tells the patient how much money you have saved by not buying cigarettes so far, as well as how many days you have been clean and how many cigarettes you have not smoked so far. Seeing statistics can give patients positive energy and make it easier to quit smoking or drinking (Fig. 5 ). Moreover, in order to get rid of addiction and drugs, patients can send their current history to their therapists on a daily basis through social networks in the form of text, audio, video or PDF files. Then, the therapists will provide them with the necessary guidance and recommendations.

In the category of relaxation instructions, different methods of relaxing the patient through slow and regular breathing, muscle strengthening, prayer, music therapy, aromatherapy, mental imagery, mindfulness, meditation, walking with mindfulness or yoga and repetition of soothing words is taught. These trainings were provided to the patient in the form of text, videos and voice.

It should be noted that the educational material featured in our application, which includes topics such as lifestyle guidance, relaxation instructions, and disease management and control, was meticulously curated from the websites of the Iranian Psychological Association ( https://iranpa.org/ ) and Iranian Psychiatrist Association ( http://www.psychiatrist.ir/main/ ). To ensure the accuracy and alignment of this content with recommended best practices in treatment, a rigorous review process was undertaken. Specifically, the content underwent evaluation and approval by two experienced psychiatrists who possess expertise in the field of mental health and have a deep understanding of evidence-based treatment approaches. This collaborative effort between medical professionals and our development team aimed to ensure that the educational content within our application adheres to the highest standards of quality and reliability, ultimately providing users with valuable and trustworthy information to support their mental health and well-being.

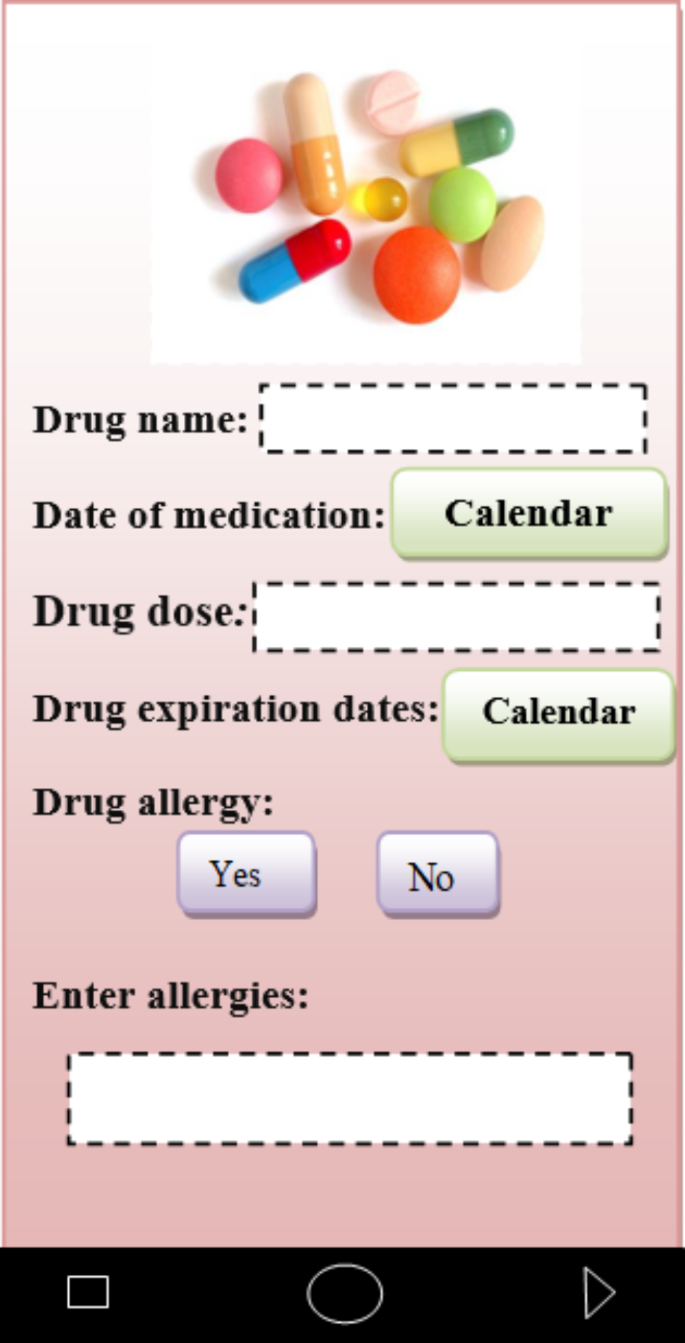

In the capabilities category, addresses and phone numbers of medical centers in Fars province (Iran) were introduced to patients to receive counseling services. Patients could contact these centers to get an appointment or go to these centers in person according to the addresses provided. In the field of drug management, nutrition and diet management, patients could set a diet plan for themselves. For example, in the drug management section, patients could enter the drug name, dosage, drug allergies, and drug use date. According to the time and date of use, the necessary reminders were given to the patient (Fig. 6 ). In the notebook section, patients can write down information about their mental health, relationships, mood or feelings. Also, record her/his activities, personal goals or habits.

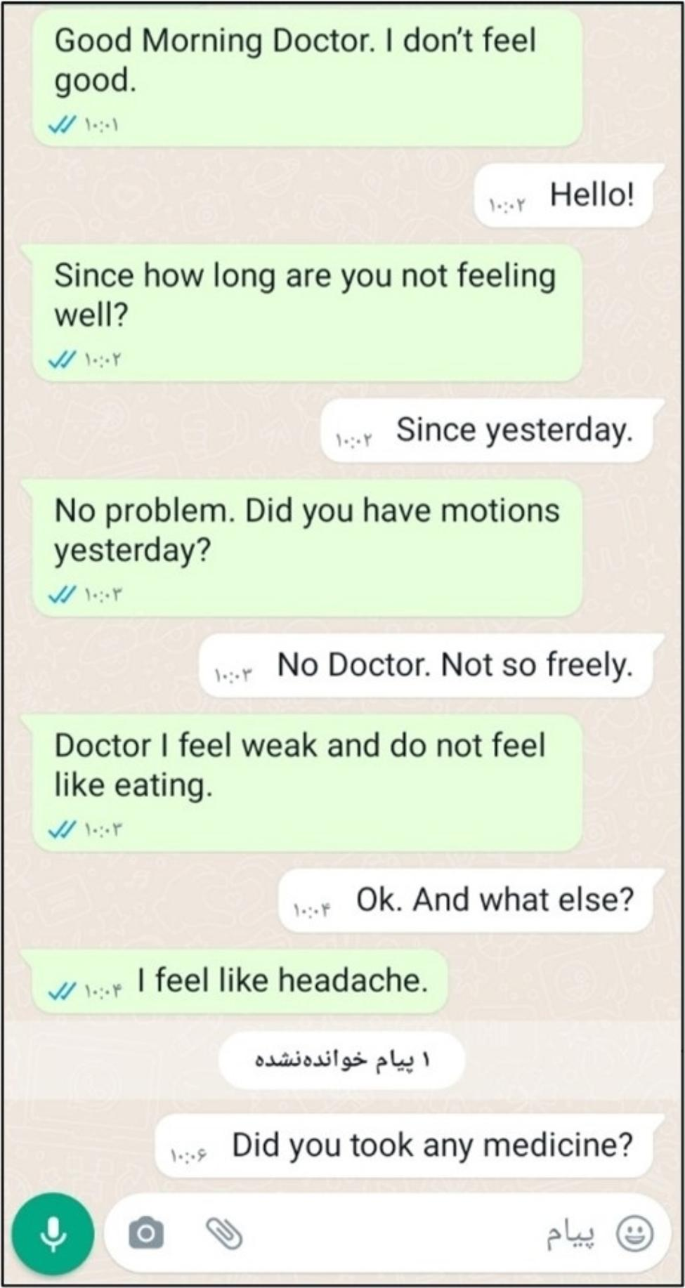

In the section of communication with doctors, consultants and other patients, a group was formed on WhatsApp and Telegram, patients could talk to doctors and consultants and other patients and share their experiences in this groups. Also, they could ask their questions. In the section of appointment reminder, patients could enter the time and date of appointment, doctor’s name and office address. Like other applications, patients can customize reminders based on physicians’ recommendations. For example, the patient needs to be advised by the doctor to take a medicine every day at 8 am, the patient can take his medicine on time by set a reminder for every day at 8 am. Based on the recorded time and date, reminders are provided to the patient automatically. It should be noted that reminders can act as guidance or messages to help facilitate behavior change and increase adherence to medication or treatment and patient attendance at appointments [ 49 ]. Moreover, reminders can reduce the need to memorize, reduce the number of missed drug doses, reduce treatment interruptions, avoid forgetting to take medications, and perform laboratory tests on time [ 49 , 50 ].

In the application settings, the user can change settings such as font and size, font color and themes.

It should be noted that after registering information in the application, patients can report them in PDF format and send them to their therapists via email or social networks. Patients could also talk to their therapist through social networks. Figure 7 shows an example of conversations between the patient and the therapist.

Home page of depression and anxiety self-care application

Recording of medical and clinical records

Quitting drinking and smoking

Drug management

An example of a conversation between a patient and a therapist

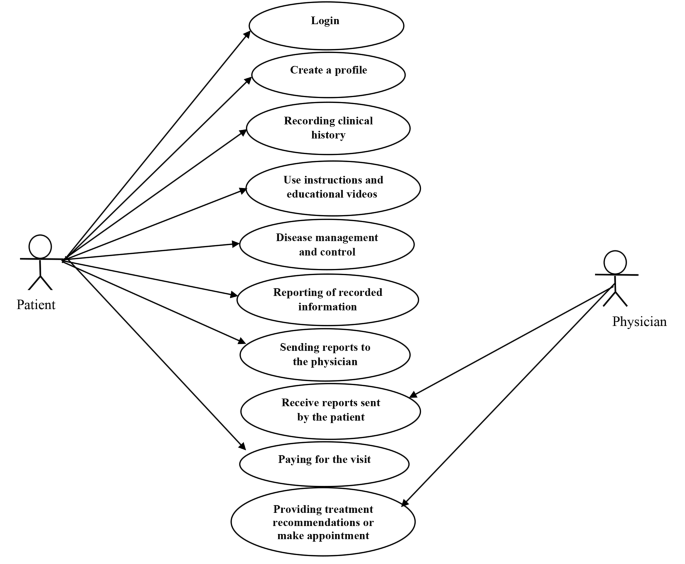

In order to better understand the capabilities of the designed application, we designed a use-case diagram for patients and physicians. The application allows patients to: (1) log into the system, (2) Create a profile, (3) record their clinical history, (4) View tutorials with self-care instructions, (5) Using the app’s capabilities to manage and control the disease, (6) reporting on recorded clinical information, (7) sending reports to physicians through social networks or email, and (8) paying for the visit (Fig. 8 ). All patient data is stored in the application database. Moreover, the application allows physicians to: (1) receive reports sent by the patient, and (2) provide treatment recommendations or make an appointment (Fig. 8 ).

Use Case diagram for patient and physician

In this study, a mobile-based self-care application was designed and developed for patients with depression and anxiety disorders. The designed application allows the patient to register and enter through a username and password and record their clinical history in PDF format and send it to the doctor. Also, this app can help to improve patients’ lifestyles by providing educational information on reducing and controlling anxiety and depression in the form of videos, text and voice. Moreover, management of medications dose and time of use, the ability to record activities, personal goals and habits in a diary, the introduction of depression and anxiety treatment centers, communication with other patients and doctors were other features of this application. Wasil R et al. [ 51 ] reviewed applications were designed for depressive and anxiety disorders in a review study. The most common features used in these applications included educational and self-assessment services to patients, how to gain calm, concentration and meditation. Also, in our study, educational services were provided to improve self-care processes and how to achieve relaxation, concentration and meditation. Instructions for concentration and relaxation let person to get rid of internal and external factors that bother him/her. These instructions can help people to return to a normal state and perform daily routine activities in the present [ 52 ] and reduce stress and anxiety in people with depressive and anxiety disorders [ 53 , 54 , 55 ].

Fuller-Tyszkiewicz et al. [ 56 ] also designed a self-monitoring application with name BlueWatch to improve the well-being of adults with depressive symptoms. This app is organized based on the principles of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) in six modules of psychological education about depression and an introduction to CBT, behavioral activation, cognitive reconstruction, problem-solving skills, assertiveness, and treatment methods to prevent Recurrence of disease. Blue Watch features also included short audio education activities, daily practice and self-monitoring functions (using daily mood recordings), short welcome video, training with the app and dashboard (to store patient activities and texts). The present study provides daily exercises in the form of relaxation instructions in the designed application. Patients by performing daily exercises such as calm and regular breathing, muscle strengthening, prayer, music therapy, aromatherapy, mental imagery, mindfulness, meditation, walking with mindfulness or yoga, repeating soothing words help themselves to reduce stress and anxiety.

Management of smoking, shisha, alcohol and drugs was another feature of the application designed in our study. Deady et al. [ 57 ] also were considered a section for managing of smoking, hookahs, alcohol, and drugs in their application, along with other information-educational needs and capabilities such as training programs (prevention of exacerbation of effects of anxiety and depression disorders, overcoming stress and negative thoughts, how to get away from relationships and stressful environments) relaxation instruction, sleep management, physical activity and exercise, and daily programming. Other studies [ 58 , 59 , 60 ] have shown that there is a direct link between depression and anxiety and smoking. They can increase the severity of anxiety and depression in these patients over the time. So, in self-care applications for these patients, it is better to allocate a section for smoking, shisha, alcohol management.

Patient management of medications was another feature of the application designed in the present study. This feature can help patients to enter the name of the drug, dosage, drug allergies and drug use date. In order to take the medicine, the necessary warnings were given to the patient according to the time and date of use. Philip Kaare Løventoft et al. [ 61 ] designed an application called life management to support patients with depression. This application has various capabilities for user registration, measuring the patient’s depression based on the WHO Major Depression Inventory (MDI) questionnaire, Mood, appetite and sleep registration, calendar and event types, location tracking and mapping (providing data on patient movement patterns for Predicting phases of depression) and routine management (to help users with daily tasks such as getting out of bed, taking a shower, and daily programming). Also, it had capabilities to record a list of drugs that could be edited by the user, reminding the use of drugs in the Medication management section.

In evaluating a mobile application, there are always problems, advantages and disadvantages, which will be analyzed in the following. Furthermore, Wei and et al. [ 62 ], underscored the significance of an interactive process that didn’t bewilder users or require numerous iterations for comprehension, as such hurdles hindered their sustained engagement with the application. For example, offering clear explanations of how the mHealth intervention operated, including guidance on what steps to take next, encouraged ongoing usage.

The unwillingness of patients [ 63 , 64 ] to cooperate in the evaluation process is one of the major issues with evaluating mobile applications. Patients’ lack of knowledge and awareness of the advantages and uses of these applications, as well as a lack of sufficient evidence regarding the effectiveness of anxiety and stress applications, may also contribute to their unwillingness to cooperate. Therefore, ways to encourage patient cooperation should be offered. One of these solutions is to give patients adequate information about the utility and efficacy of the application. The application’s adoption and use, as well as collaboration, can all be enhanced by this solution. Additionally, inviting patients from different races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and education statuses to a meeting of the research team to discuss this application and its advantages can be helpful [ 65 ]. If patients are made aware that self-care tools may aid in illness management and control. Then, it will be simpler for patients to embrace these apps since they would think that by following self-care the applications, their recovery will be substantially accelerated [ 64 , 66 , 67 ]. The team can highlight the advantages of an anxiety and depression self-care app, like better health information access [ 68 ], lower medical errors and treatment costs, improved coordination among healthcare providers, and reduced patient travel [ 69 ]. They can also inform patients that the app offers greater flexibility, enabling them to spend less time at treatment centers and more time on daily tasks [ 70 ].

Privacy concerns during patient evaluations are another issue that has been identified in prior research [ 71 , 72 , 73 ]. Designers of applications should strive to keep patient information private. Therefore, each patient must have a unique username and password for self-care applications. In addition, the research team should provide sufficient assurance to the patients that the information they enter will remain confidential while using the application. The ease of use of self-care applications is another patient concern [ 74 , 75 ]. This issue can be resolved by providing patients with the necessary training in the form of multiple training sessions, as well as by preparing educational files in the form of video and text regarding the use of the application for patients and doctors [ 24 ].

Another issue in mobile application evaluation is the availability of various evaluation tools (questionnaires such as mobile app rating scale (MARS) and system usability scale (SUS), heuristic evaluation, think aloud, etc.) and the lack of flexibility of these tools. For instance, Zhou et al. [ 76 ], argued that the SUS questionnaire, when applied to aspects unique to mobile apps, fails to yield the specific information required for evaluating mobile applications effectively, highlighting the need for tailored evaluation tools in the mobile app domain. To solve this issue, the primary objective of each research’s evaluation should be identified, and then the right tool should be chosen. The tool selected for evaluation should focus on various dimensions related to evaluation quality, readability and cultural sensitivity of content, usability and features of health applications [ 77 ]. Another drawback of application evaluation studies is the length of time needed to complete the evaluation. A mobile application may initially appeal to the patient and the therapist in a way that yields a positive initial evaluation result, but over time, the outcome changes. As a result, it is preferable to evaluate over time. It should be noted that imbalances in access to online health care systems that are a reflection of well-known socioeconomic disparities in access to online services. The same factor makes using mobile devices for remote service delivery to rely on patients who have more facilities and skills and may unjustly burden those who are less able with treatment using newer technologies [ 78 ]. One of the difficulties that evaluators encounter when assessing applications for anxiety and stress management programs is this disparity. In this case, researchers may decide to exclude study participants who lack smart phones, internet access, adequate bandwidth, a sufficient level of literacy, or the desire to take part in the study.

App evaluation can also have benefits. Different aspects of an application are examined in different ways during evaluations. For instance, the following three factors are taken into account and scrutinized during the usability evaluation: (1) Having greater usability, (2) more user satisfaction (meets the user’s expectations), and (3) easier learning (the operation can be learned very quickly by observation). Or, ten indicators are highlighted in Nielsen’s assessment: (1) display Visibility of system status, (2) consistency and standards, (3) user control and freedom, (4) error prevention, (5) recognition rather than recall, 6) flexibility and efficiency of use, (7) flexibility and efficiency of use, (8) aesthetic and minimalist design, (9) honesty in expressing mistakes and providing solutions - assisting users in identifying, analyzing, and resolving errors; and (10) assistance and documentation [ 79 , 80 ]. The design team will identify and address any issues with these dimensions after evaluating the application. A user-friendly application will subsequently be created for users. However, once all the issues are resolved, the patients’ continued use of the application will increase. Patients will be less satisfied and use these applications less if an application is not usable or does not have the necessary quality for the patient’s goals [ 81 ]. According to some studies [ 82 , 83 ], users will be dissatisfied with the application if there are potential delays in their response to the application, a lack of optimal speed for the information and content it contains, difficulty in learning and comprehending its features. So, the amount of use of the application with them decreases day by day.