- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How Venture Capitalists Make Decisions

- Paul Gompers,

- Will Gornall,

- Steven N. Kaplan,

- Ilya A. Strebulaev

For decades now, venture capitalists have played a crucial role in the economy by financing high-growth start-ups. While the companies they’ve backed—Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and more—are constantly in the headlines, very little is known about what VCs actually do and how they create value. To pull the curtain back, Paul Gompers of Harvard Business School, Will Gornall of the Sauder School of Business, Steven N. Kaplan of the Chicago Booth School of Business, and Ilya A. Strebulaev of Stanford Business School conducted what is perhaps the most comprehensive survey of VC firms to date. In this article, they share their findings, offering details on how VCs hunt for deals, assess and winnow down opportunities, add value to portfolio companies, structure agreements with founders, and operate their own firms. These insights into VC practices can be helpful to entrepreneurs trying to raise capital, corporate investment arms that want to emulate VCs’ success, and policy makers who seek to build entrepreneurial ecosystems in their communities.

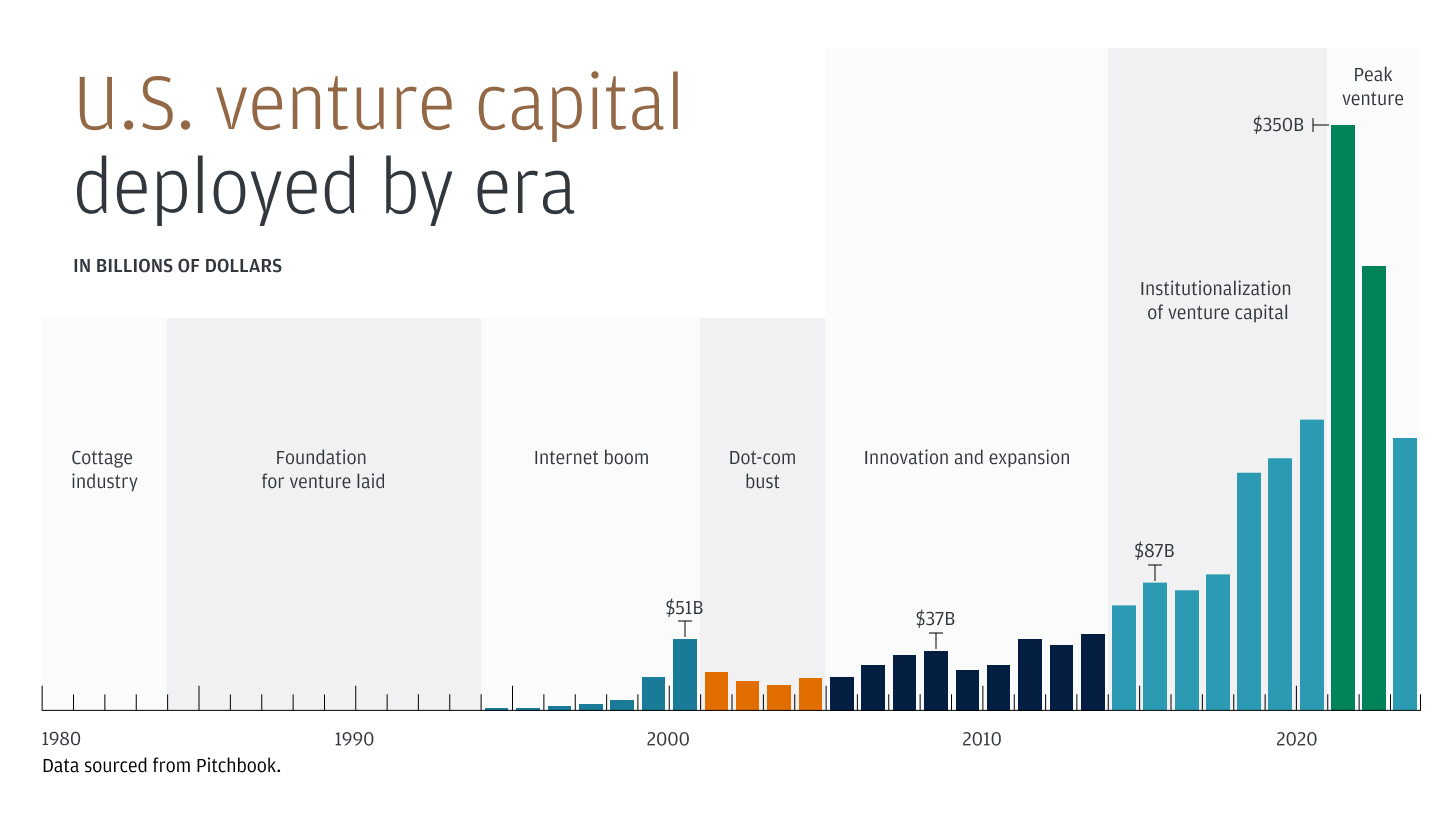

An inside look at an opaque process

Over the past 30 years, venture capital has been a vital source of financing for high-growth start-ups. Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Gilead Sciences, Google, Intel, Microsoft, Whole Foods, and countless other innovative companies owe their early success in part to the capital and coaching provided by VCs. Venture capital has become an essential driver of economic value. Consider that in 2015 public companies that had received VC backing accounted for 20% of the market capitalization and 44% of the research and development spending of U.S. public companies.

- PG Paul Gompers is the Eugene Holman Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

- WG Will Gornall is an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia Sauder School of Business.

- SK Steven N. Kaplan is the Neubauer Family Professor of Entrepreneurship and Finance and the Kessenich E.P. Faculty Director of the Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship at the University of Chicago.

- IS Ilya A. Strebulaev is the David S. Lobel Professor of Private Equity and a professor of finance at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He is also the founder of the Stanford GSB Venture Capital Initiative and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Partner Center

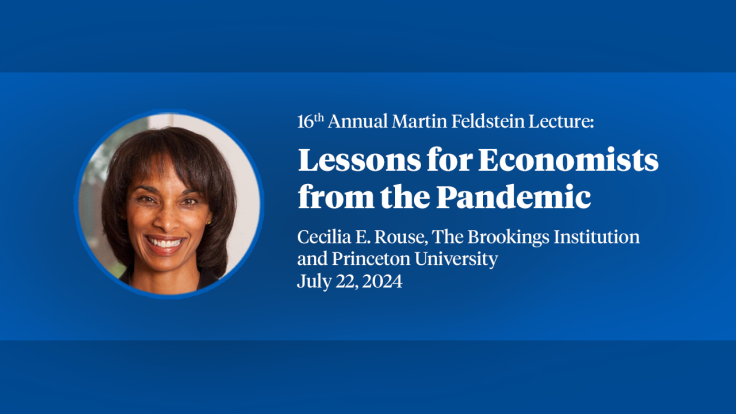

16 research papers every VC should know

Posted by Shaun Gold | October 10, 2022

Understanding venture capital is more than reading decks and tweaking your fund’s investment thesis. It requires an edge that comes from knowledge. Here are thirteen of the best research papers on VC to help you obtain that edge.

Table of Contents

1. many of the largest u.s. companies owe a vc.

VC powers the U.S. economy

Will Gornall (University of British Columbia (UBC) - Sauder School of Business) and Ilya A. Strebulaev (Stanford University - Graduate School of Business; National Bureau of Economic Research) showcase that Venture capital-backed companies account for 41% of total US market capitalization and 62% of US public companies’ R&D spending. Among public companies founded within the last fifty years, VC-backed companies account for half in number, three quarters by value, and more than 92% of R&D spending and patent value. This only transpired after the 1970s ERISA reforms. The paper further shows that US VC industry is causally responsible for the rise of one-fifth of the current largest 300 US public companies and that three-quarters of the largest US VC-backed companies would not have existed or achieved their current scale without an active VC industry.

2. Geographic Concentration of VC Investors in a Syndicate is Correlated to Deal Structure, Board Representation, Follow-On Rounds, and Exit Performance

Geographic concentration of venture capital investors, corporate monitoring, and firm performance.

A May 2019 Dartmouth paper by Jun-Koo Kang, Yingxiang Li, and Seungjoon Oh finds that compared to VC investors that are geographically dispersed, those that are geographically concentrated use less intensive staged financing and fewer convertible securities in their investments, are less likely to have board representation in their portfolio firms, and are more likely to form successive syndicates in follow-up rounds. Moreover, their firms experience a greater likelihood of successful exits, lower IPO underpricing, and higher IPO valuation.

3. VC firms that lack diversity perform 11%-30% lower on average

VC firms that lack diversity pay a higher cost

A 2017 paper from Paul A. Gompers and Sophie Q. Wang of Harvard documents the patterns of labor market participation by women and ethnic minorities in venture capital firms and as founders of venture capital-backed startups. If the partners of the VC firm are from the same school, the fund has a lower performance of 11%. If the partners have the same ethnicity, the fund has a lower performance of 30%. If the fund is all men, there is a 20% lower performance.

4. Venture Capital infusion harms non-VC backed industries in communities

The Silicon Valley Syndrome

A 2019 paper from Doris Kwon and Olav Sorenson of Yale University demonstrates that an infusion of venture capital in a region actually is more harmful than beneficial. The paper illustrates that VC infusion in a region is associated with declines in entrepreneurship, employment, and average incomes in other industries in the tradable sector while at the same time an increase in entrepreneurship and employment in the non-tradable sector and income equality overall in the region.

For example, the boom of Silicon Valley caused real estate prices in the Bay Area to rise which priced out low-salaried workers in the non technology sector. This caused other firms to lose talent to a handful of Silicon Valley technology companies. This is similar to the Netherlands in the 1960s after the discovery of natural gas which led to booming petroleum exports and the value of the Dutch currency to rise. Yet this also caused harm to other firms due to rising operating costs and to them losing workers to the natural gas extraction industry. The economy was left more vulnerable overall.This became known as “Dutch Disease.”

5. VC’s who’ve been fortunate to succeed once keep succeeding as initial success brings them quality deal flow

The persistent effect of initial success

A 2019 paper from Sampsa Samila (IESE Business School), Olav Sorenson (Yale), and Ramana Nanda (Harvard) illustrated that each additional initial public offering (IPO) among a VC firm’s first ten investments predicts as much as an 8% higher IPO rate on its subsequent investments, though this effect erodes with time. Successful outcomes result in large part from investing in the right places at the right times; VC firms do not persist in their ability to choose the right places and times to invest; but early success does lead to investing in later rounds and in larger syndicates. This pattern of results seems most consistent with the idea that initial success improves access to deal flow. That preferential access raises the quality of subsequent investments, perpetuating performance differences in initial investments. What does all this mean?

Get lucky once and everyone thinks you have the right stuff which results in more opportunities and quality deal flow.

6. Half of VC investments are predictably bad—based on information known at the time of investment

Predictably Bad Investments: Evidence from Venture Capitalists

Diag Davenport of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business argued in a 2022 paper that institutional investors fail to invest efficiently. By combining a novel dataset of over 16,000 startups (representing over $9 billion in investments) with machine learning methods to evaluate the decisions of early-stage investors, Davenport showed that approximately half of the investments were predictably bad. This was based on information known at the time of investment and that the predicted return of the investment was less than readily available outside options. Suggestive evidence also illustrated that an over-reliance on the founders’ background is one mechanism underlying these choices. The results suggest that high stakes and firm sophistication are not sufficient for efficient use of information in capital allocation decisions.

7. Getting funded by a reputable VC with a strong brand adds a lot of value

This paper by Darden pressor Ting Xu, Shai Bernstein of Harvard Business School, Kunal Mehta of AngelList LLC, and Richard Townsend of the University of California, San Diego analyzed a field experiment conducted on AngelList Talent. During the experiment, AngelList randomly informed job seekers of whether a startup was funded by a top-tier investor and/or was funded recently. Startups received more interest when information about top-tier investors was provided. Information that included the most recent funding amount had no effect. The effect of top-tier investors is not driven by low-quality candidates and is stronger for earlier-stage startups. Essentially, the potential employees cared about who funded it and not the amount. The results demonstrated that venture capitalists can add value passively, simply by attaching their names to startups.

8. VCs invest in the team rather than the product or technology

How do venture capitalists make decisions?

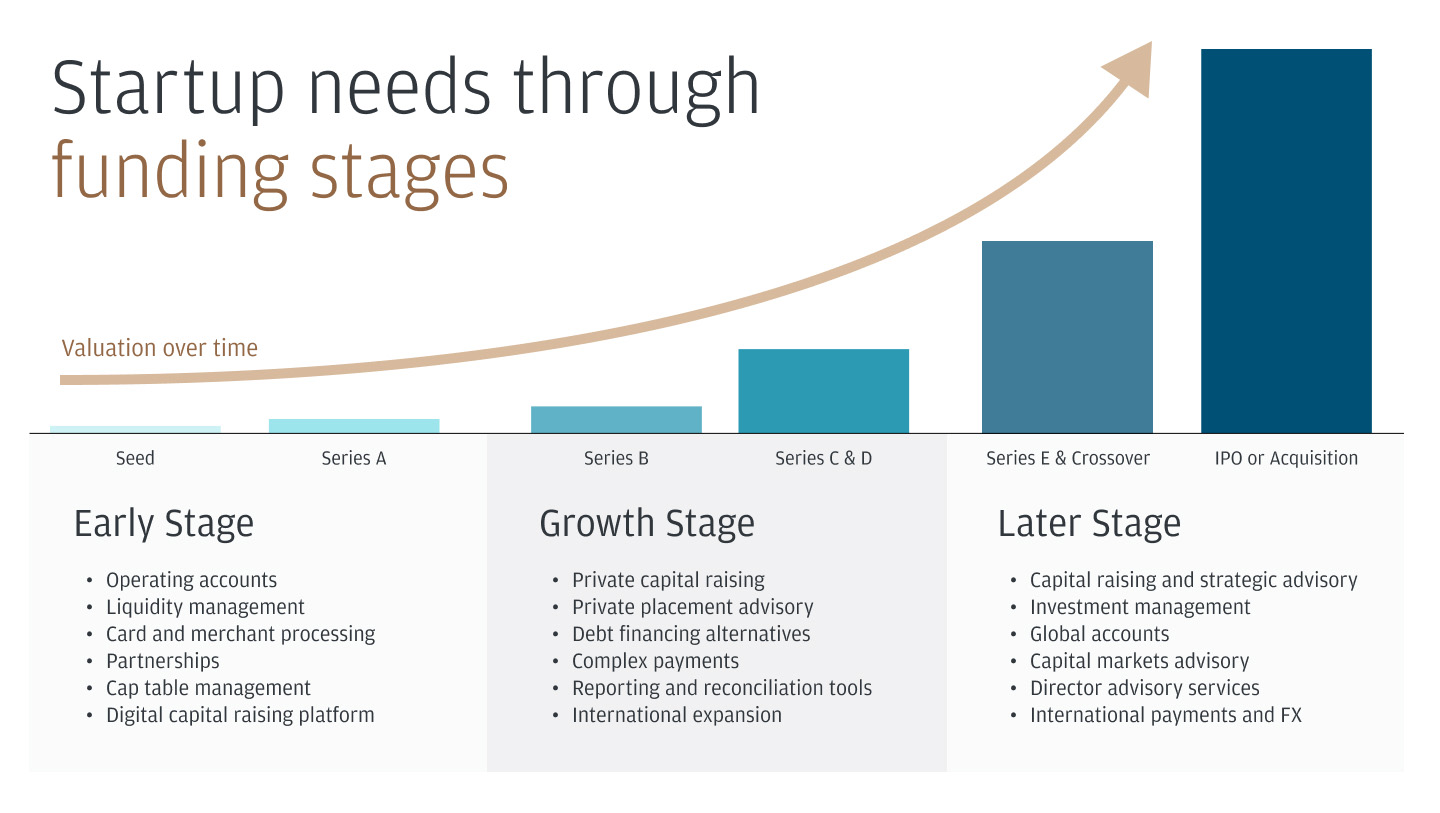

This paper was written by a rockstar team composed of Steven Kaplan, Neubauer Distinguished Service Professor of Entrepreneurship and Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and Kessenich E.P. Faculty Director of the Polsky Center, along with Paul Gompers at Harvard University Graduate School of Business; Will Gornall at the Sauder School of Business at the University of British Columbia; and Ilya Strebulaev at the Stanford University Graduate School of Business. They surveyed 885 institutional venture capitalists at 681 firms about practices in pre-investment screening, structuring investments, and post-investment monitoring and advising. The results showed that VCs see the management team as somewhat more important than business-related characteristics such as product or technology. VCs also view the team as more important than the business to the ultimate success or failure of their investments. The VCs rated deal selection as the most important factor contributing to value creation, more than deal sourcing or post-investment advising.

9. VC has real limitations in its ability to advance substantial technological change

Venture Capital’s Role in Financing Innovation: What We Know and How Much We Still Need to Learn

In this paper, Harvard professors Josh Lerner and Ramana Nanda argue that despite the growth VC brings into technology companies, there remain real limitations in regard to technological change. They are concerned about the very narrow band of technological innovations that fit the requirements of institutional venture capital investors; the relatively small number of venture capital investors who hold and shape the direction of a substantial fraction of capital that is deployed into financing radical technological change; and the relaxation in recent years of the intense emphasis on corporate governance by venture capital firms. They believe this may have ongoing and detrimental effects on the rate and direction of innovation in the broader economy.

10. More collaborative experience among VCs leads to M&A while less leads to an IPO

The Past Is Prologue? Venture-Capital Syndicates’ Collaborative Experience and Start-Up Exits

Dan Wang of Columbia, Emily Cox Pahnke of the University of Washington, and Rory McDonald of Harvard argue that as prior collaborative experience within a group of VCs increases, a jointly funded start-up is more likely to exit by acquisition (which they call a focused success); with less prior experience among the group of VCs, a jointly funded start-up is more likely to exit by initial public offering (which they term a broadcast success). This tested their hypotheses using data from Crunchbase on a sample of almost 11,000 U.S. start-ups backed by venture-capital (VC) firms, using the VCs’ previous collaborative experience to predict the type of success that the start-ups will experience.

11. Solo-founded startups are strongly associated with more rapid growth to unicorn status

In a paper by Greg Fisher, Suresh Kotha, and S. Joseph Chin, startups that have reached unicorn status are thoroughly examined. This is done through prior research on growth and valuation of unicorns as well as examining the dynamics to view the variations in which they reach a billion dollars in valuation. Ultimately, the paper demonstrates that the founder's age, gender, and affiliation with the Ivy League were not significantly related to the growth of unicorns. Furthermore, solo-founded startups are more associated with rapid growth to a unicorn valuation.

12. Warm introductions lead to 13x higher chance of funding

UK Venture Capital and Female Founders Report

Alice Hu Wagner, Calum Paterson, and Francesca Warner illustrate that startup decks that come in warm are far more likely to get funded. This rewards founders who have a great network and are connected but harms the multitude who lack these connections. If founders lack a network of investors, bankers, angels and other founders, fewer will be able to reach a proper VC.

13. Venture capitalists should stay in their lane

Venture capitalists are specialists.

Tyler J. Hull argues that VC performance is much better in the sub-industry they focus on rather than sub-industries where they have limited experience. And they underperform more the further outside their focus they go. Co-investing with another venture capitalist that has the same investment focus as the investment firm partially mitigates this effect. Additionally, the negative effect is shown to be more pronounced the greater the degree of difference between the venture capital’s preferred investment industry and the investment industry.

In other words, VCs should stay in their lane and make investments in their area of focus.

14. Data makes all the difference

Hatcher+ and need for data driven forecasting.

Hatcher+ is a globally diversified, multi-sector, early-stage technology investment fund founded in 2018. Based in Singapore, the managers use a combination of data science, modeling, workflow automation, and machine learning to execute a global venture investment strategy capable of unprecedented scale in terms of the number of investments. As a result, they produced a paper on venture capital transaction history to define and refine its approach to early stage investing. Via their own research, they discovered that data quality is actionable for a data-driven VC firm, accelerator rounds provide a strong opportunity for investment, deal flow is essential (especially for firms with large portfolios), large portfolios with follow on increases viability and adds round diversification, and that larger portfolios by investment count are key to early stage success.

15. Founders can become VCs but that doesn’t guarantee success

Success and failure as a founder plays a role if a founder becomes a VC

Paul A. Gompers & Vladimir Mukharlyamov explore whether or not the experience as a founder of a venture capital-backed startup influences the performance of founders who become venture capitalists. They discovered that almost 7% of VCs were previously founders of a venture-backed startup. Having a successful exit (an acquisition or IPO) as well as being male and white increased the probability that a founder transitioned into a career in VC. Successful founder-VCs have investment success rates that are 6.5 percentage points higher than professional VCs while unsuccessful founder-VCs have investment success rates that are 4 percentage points lower than professional VCs. The primary benefit of a founder-VC is not deal flow but the value add that they provide to their portfolio companies.

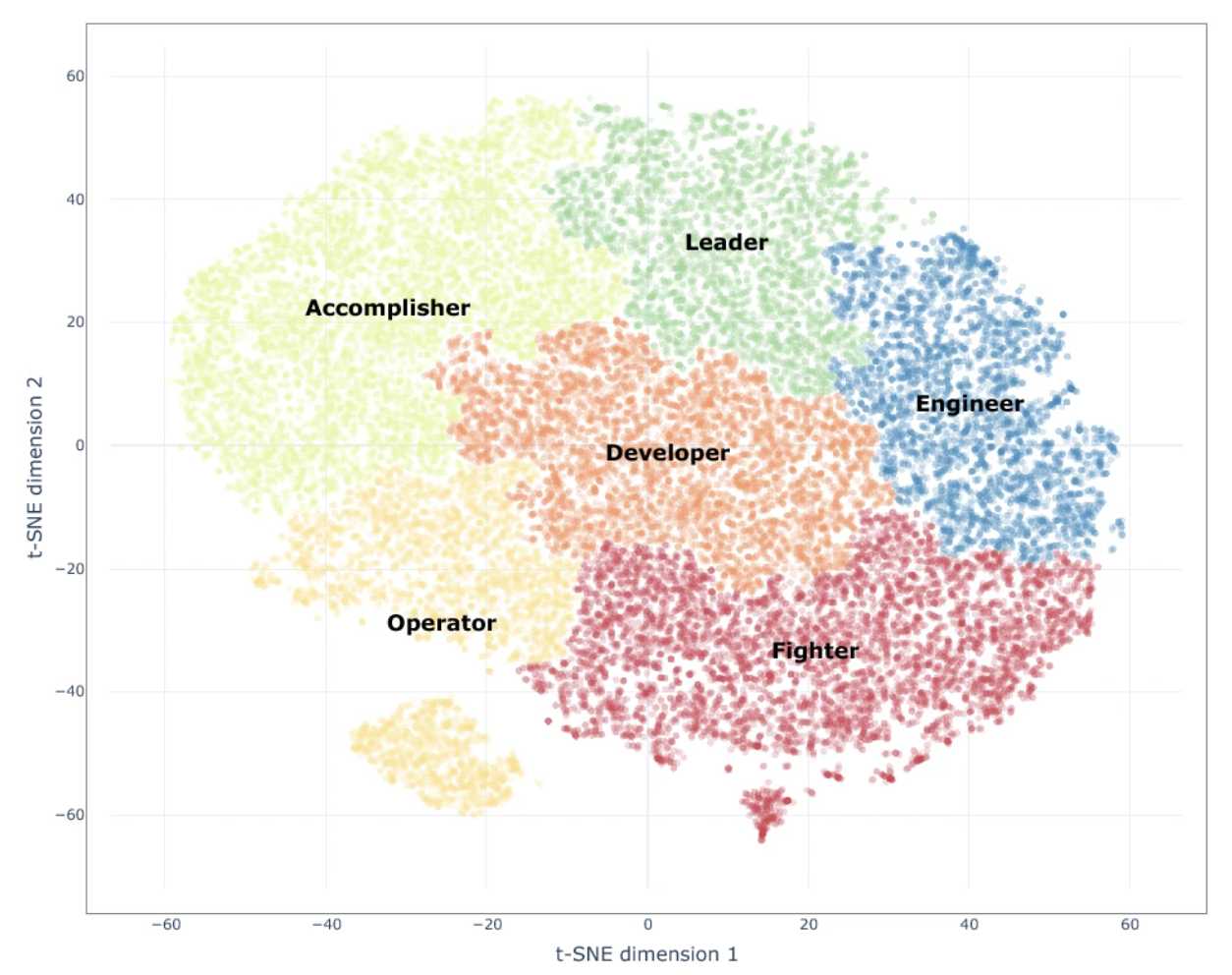

16. Successful founders have similar personality traits

The impact of founder personalities on startup success

Paul McCarty et alii. ran a large-scale study over 21,000 startups worldwide and found that personality traits of startup founders differ from that of the population at large. Successful entrepreneurs show high openness to adventure, like being the centre of attention, have higher activity levels. Six different personality types appear for founders: Accomplisher, Leader, Operator, Developer, Engineer, Fighter.

Venture capital is still a young industry and has more bragging rights than most realize. By effectively reading the research conducted by some of the leading academics at top universities, you can give yourself an edge and competitive advantage. This doesn’t cost but I promise you that it will pay.

Did we miss a great research paper that you think VCs should add to their arsenal of knowledge? Email me at [email protected] and I will add it.

OpenVC is a radically open platform that helps tech founders connect with the right investors.

POPULAR Posts

An LP take on VC portfolio construction

How to write a top 1% cold email to VCs

Pitch deck for startups - 9 templates compared

How to Model a Venture Capital Fund

How to whitelist OpenVC

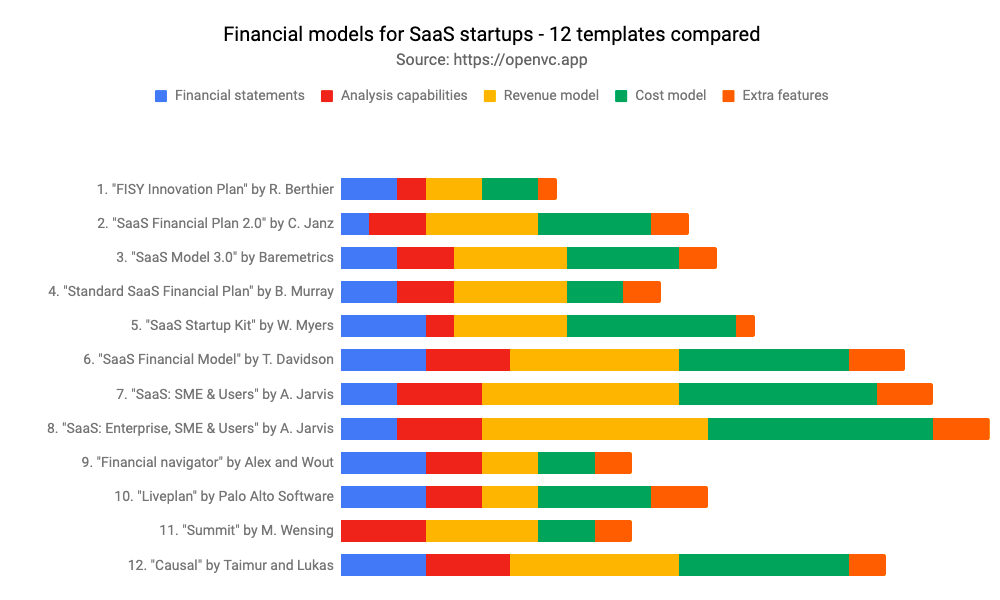

Startup financial models - 12 templates compared

You might also enjoy

Why Seed Funding Is a Pool Party

You might think you’re fundraising, but what you’re actually doing is throwing a pool party. Venture funding dynamics in the Seed Phase have evolved differently than venture capital at Series A and beyond. A Seed fund would almost never take the whole round, even if it could.

Launching a VC fund? Why not a FAST instead?

With more funds in the market than ever, managers need to stay relevant and develop new models. Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technology are coming to the forefront of the £10tn UK Asset Management industry. With that in mind, let me introduce you to FAST, a plug-and-play tokenized investment vehicle for hands-on syndicates and accelerators.

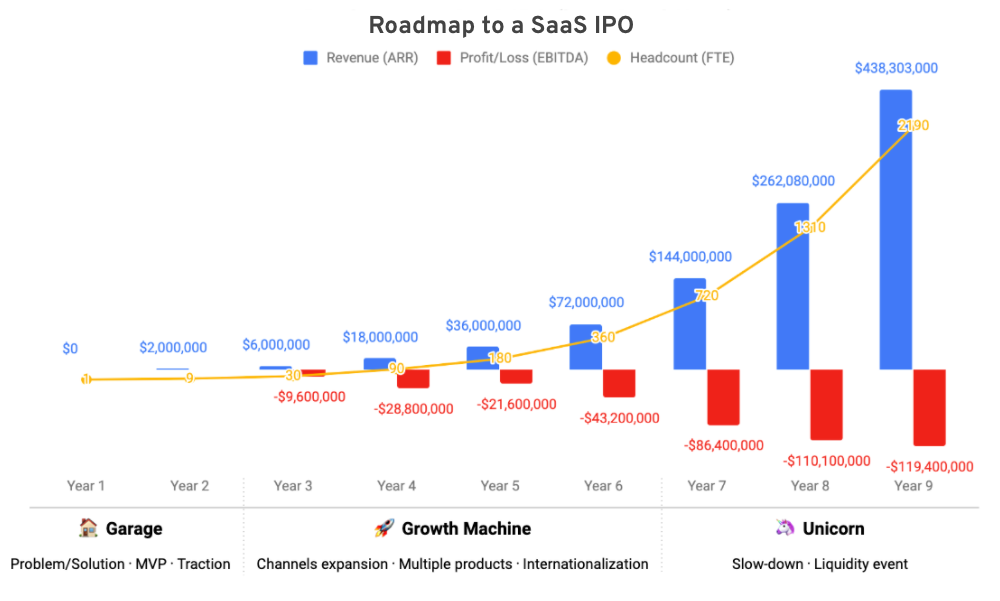

Roadmap to a SaaS IPO: how to unicorn your way to $100M revenue

Uncover 7 golden metrics leading to a SaaS IPO - timeframe, growth rate, EBITDA, funding, exit milestones, sales, and headcount.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

The role of venture capital investment in startups’ sustainable growth and performance: focusing on absorptive capacity and venture capitalists’ reputation.

1. Introduction

2. background: the five stages of startup growth, 3. theory and hypotheses development, 3.1. signaling effects of venture capital investment on startups, 3.2. moderating effects of startups’ learning capability: absorptive capacity, 3.3. moderating effects of the reputation of vc companies, 4.2. variables, 6. discussion, author contributions, conflicts of interest.

- Barry, C.B.; Muscarella, C.J.; Peavy Iii, J.W.; Vetsuypens, M.R. The role of venture capital in the creation of public companies: Evidence from the going-public process. J. Financ. Econ. 1990 , 27 , 447–471. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kaplan, S.N.; Strömberg, P. Financial contracting theory meets the real world: An empirical analysis of venture capital contracts. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2003 , 70 , 281–315. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kortum, S.; Lerner, J. Assessing the contribution of venture capital to innovation. RAND J. Econ. 2000 , 31 , 674–692. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Hellmann, T.; Puri, M. Venture capital and the professionalization of start-up firms: Empirical evidence. J. Financ. 2002 , 57 , 169–197. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, H. Staged financing in venture capital: Moral hazard and risks. J. Corp. Financ. 2004 , 10 , 131–155. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gompers, P.; Lerner, J. The venture capital revolution. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001 , 15 , 145–168. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Byers, B. Relationship between venture capitalist and entrepreneur. In Pratt’s Guide to Venture Capital Sources ; Venture Economics: Wellesly Hills, MA, USA, 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bygrave, W.D.; Timmons, J.A. Venture Capital at the Crossroads ; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gompers, P.A. Optimal investment, monitoring, and the staging of venture capital. J. Financ. 1995 , 50 , 1461–1489. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Maula, M.; Murray, G. Complementary value-adding roles of corporate venture capital and independent venture capital investors. J. Biolaw Bus. 2001 , 5 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 1986 , 15 , 285–305. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Antarciuc, E.; Zhu, Q.; Almarri, J.; Zhao, S.; Feng, Y.; Agyemang, M. Sustainable venture capital investments: An enabler investigation. Sustainability 2018 , 10 , 1204. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Wang, G.; Li, L.; Jiang, X. Entrepreneurial business ties and new venture growth: The mediating role of resource acquiring, bundling and leveraging. Sustainability 2019 , 11 , 244. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Repullo, R.; Suarez, J. Venture capital finance: A security design approach. Rev. Financ. 2004 , 8 , 75–108. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wright, M.; Lockett, A. The structure and management of alliances: Syndication in the venture capital industry. J. Manag. Stud. 2003 , 40 , 2073–2102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gompers, P.; Lerner, J. An analysis of compensation in the US venture capital partnership. J. Financ. Econ. 1999 , 51 , 3–44. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jain, B.A.; Kini, O. Venture capitalist participation and the post-issue operating performance of IPO firms. Manag. Decis. Econ. 1995 , 16 , 593–606. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sapienza, H.J. When do venture capitalists add value? J. Bus. Ventur. 1992 , 7 , 9–27. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Burgel, O.; Fier, A.; Licht, G.; Murray, G.C. Internationalisation of high-tech start-ups and fast growth-evidence for UK and Germany. Zew-Discuss. Pap. 2000 , 00–35. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Manigart, S.; Van Hyfte, W. Post-investment evolution of Belgian venture capital backed companies: An empirical study. In Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 1999. Nineteenth Annual Entrepreneurship Research Conference ; Babson Center for Entrepreneurial Studies: Babson Park, MA, USA, 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anton, J.J.; Yao, D.A. Expropriation and inventions: Appropriable rents in the absence of property rights. Am. Econ. Rev. 1994 , 84 , 190–209. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Ritter, J.R. Innovation and communication: Signalling with partial disclosure. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1983 , 50 , 331–346. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ueda, M. Banks versus venture capital: Project evaluation, screening, and expropriation. J. Financ. 2004 , 59 , 601–621. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yosha, O. Information disclosure costs and the choice of financing source. J. Financ. Intermediation 1995 , 4 , 3–20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ruhnka, J.C.; Young, J.E. A venture capital model of the development process for new ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 1987 , 2 , 167–184. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Valentim, L.; Lisboa, J.V.; Franco, M. Knowledge management practices and absorptive capacity in small and medium-sized enterprises: Is there really a linkage? RD Manag. 2016 , 46 , 711–725. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ruhnka, J.C.; Young, J.E. Some hypotheses about risk in venture capital investing. J. Bus. Ventur. 1991 , 6 , 115–133. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baum, J.A.; Oliver, C. Institutional linkages and organizational mortality. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991 , 187–218. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cox Pahnke, E.; McDonald, R.; Wang, D.; Hallen, B. Exposed: Venture capital, competitor ties, and entrepreneurial innovation. Acad. Manag. J. 2015 , 58 , 1334–1360. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ueda, M. Bank versus venture capital. Upf Econ. Bus. Work. Pap. 2000 , 522. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Lukkarinen, A.; Teich, J.E.; Wallenius, H.; Wallenius, J. Success drivers of online equity crowdfunding campaigns. Decis. Support Syst. 2016 , 87 , 26–38. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S. Economic freedom and cross-border venture capital performance. J. Empir. Financ. 2012 , 19 , 26–50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Lyu, C. Exploratory orientation, business model innovation and new venture growth. Sustainability 2017 , 10 , 1–15. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ang, S.H. Country-of-origin effect of VC investment in biotechnology companies. J. Commer. Biotechnol. 2006 , 13 , 12–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bacon-Gerasymenko, V.; Eggers, J.P. The dynamics of advice giving by venture capital firms: Antecedents of managerial cognitive effort. J. Manag. 2019 , 45 , 1660–1688. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lounsbury, M.; Glynn, M.A. Cultural entrepreneurship: Stories, legitimacy, and the acquisition of resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001 , 22 , 545–564. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aldrich, H.; Auster, E.R. Even dwarfs started small: Liabilities of age and size and their strategic implications. Res. Organ. Behav. 1986 , 8 , 165–198. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rickne, A. Connectivity and performance of science-based firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2006 , 26 , 393–407. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pisano, G.P. Knowledge, integration, and the locus of learning: An empirical analysis of process development. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994 , 15 , 85–100. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Teece, D.J. Competition, cooperation, and innovation: Organizational arrangements for regimes of rapid technological progress. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1992 , 18 , 1–25. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Carter, R.; Manaster, S. Initial public offerings and underwriter reputation. J. Financ. 1990 , 45 , 1045–1067. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shan, W.; Walker, G.; Kogut, B. Interfirm cooperation and startup innovation in the biotechnology industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994 , 15 , 387–394. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Stuart, T.E.; Hoang, H.; Hybels, R.C. Interorganizational endorsements and the performance of entrepreneurial ventures. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999 , 44 , 315–349. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Stuart, T.E. Interorganizational alliances and the performance of firms: A study of growth and innovation rates in a high-technology industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000 , 21 , 791–811. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991 , 17 , 99–120. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gulati, R.; Higgins, M.C. Which ties matter when? The contingent effects of interorganizational partnerships on IPO success. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003 , 24 , 127–144. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Heeley, M.B.; Matusik, S.F.; Jain, N. Innovation, appropriability, and the underpricing of initial public offerings. Acad. Manag. J. 2007 , 50 , 209–225. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hsu, D.H.; Ziedonis, R.H. Resources as dual sources of advantage: Implications for valuing entrepreneurial-firm patents. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013 , 34 , 761–781. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bhatt, G.D. Organizing knowledge in the knowledge development cycle. J. Knowl. Manag. 2000 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996 , 17 , 109–122. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Prahaland, C.; Hamel, G. The core competence of the corporation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990 , 82–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990 , 35 , 128–152. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ben-Oz, C.; Greve, H.R. 2015. Short- and Long-Term Performance Feedback and Absorptive Capacity. J. Manag. 2015 , 41 , 1827–1853. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002 , 27 , 185–203. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Engelen, A.; Kube, H.; Schmidt, S.; Flatten, T.C. Entrepreneurial orientation in turbulent environments: The moderating role of absorptive capacity. Res. Policy 2014 , 43 , 1353–1369. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Volberda, H.W.; Foss, N.J.; Lyles, M.A. Perspective—Absorbing the concept of absorptive capacity: How to realize its potential in the organization field. Organ. Sci. 2010 , 21 , 931–951. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Bergh, D.D.; Lim, E.N.K. Learning how to restructure: Absorptive capacity and improvisational views of restructuring actions and performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008 , 29 , 593–616. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lane, P.J.; Koka, B.R.; Pathak, S. The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006 , 31 , 833–863. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Flatten, T.C.; Greve, G.I.; Brettel, M. Absorptive capacity and firm performance in SMEs: The mediating influence of strategic alliances. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2011 , 8 , 137–152. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Covin, J.G.; Lumpkin, G.T. Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflections on a needed construct. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011 , 35 , 855–872. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zott, C. Dynamic capabilities and the emergence of intraindustry differential firm performance: Insights from a simulation study. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003 , 24 , 97–125. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dierkens, N. Information asymmetry and equity issues. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1991 , 26 , 181–199. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rosenstein, J.; Bruno, A.V.; Bygrave, W.D.; Taylor, N.T. The CEO, venture capitalists, and the board. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993 , 8 , 99–113. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chahine, S.; Filatotchev, I.; Bruton, G.D.; Wright, M. “Success by Association”: The Impact of Venture Capital Firm Reputation Trend on Initial Public Offering Valuations. J. Manag. 2019 , 0149206319847265. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Croce, A.; Ughetto, E. The role of venture quality and investor reputation in the switching phenomenon to different types of venture capitalists. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2019 , 46 , 191–227. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chung, K.H.; Pruitt, S.W. A simple approximation of Tobin’s q. Financ. Manag. 1994 , 70–74. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Geroski, P.A. Understanding the implications of empirical work on corporate growth rates. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2005 , 26 , 129–138. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mowery, D.C.; Oxley, J.E.; Silverman, B.S. Strategic alliances and interfirm knowledge transfer. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996 , 17 , 77–91. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Tsai, W. Knowledge transfer in intraorganizational networks: Effects of network position and absorptive capacity on business unit innovation and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2001 , 44 , 996–1004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keller, W. Absorptive capacity: On the creation and acquisition of technology in development. J. Dev. Econ. 1996 , 49 , 199–227. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Veugelers, R. Internal R & D expenditures and external technology sourcing. Res. Policy 1997 , 26 , 303–315. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee, P.M.; Pollock, T.G.; Jin, K. The contingent value of venture capitalist reputation. Strat. Organ. 2011 , 9 , 33–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Vanhaverbeke, W. The influence of scope, depth, and orientation of external technology sources on the innovative performance of Chinese firms. Technovation 2011 , 31 , 362–373. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Agarwal, R.; Sarkar, M.; Echambadi, R. The conditioning effect of time on firm survival: An industry life cycle approach. Acad. Manag. J. 2002 , 45 , 971–994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper, A.C.; Gimeno-Gascon, F.J.; Woo, C.Y. Initial human and financial capital as predictors of new venture performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1994 , 9 , 371–395. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cooper, A.C.; Gascon, F.J.G. Entrepreneurs, processes of founding, and new-firm performance. The State of the Art of Entrepreneurship ; Sexton, D.L., Kasarda, J.D., Eds.; PWS-Kent: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 301–340. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bontis, N.; Wu, S.; Chen, M.C.; Cheng, S.J.; Hwang, Y. An empirical investigation of the relationship between intellectual capital and firms’ market value and financial performance. J. Intellect. Cap. 2005 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Beard, D.W.; Dess, G.G. Corporate-level strategy, business-level strategy, and firm performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1981 , 24 , 663–688. [ Google Scholar ]

- Erhardt, N.L.; Werbel, J.D.; Shrader, C.B. Board of director diversity and firm financial performance. Corp. Gov. 2003 , 11 , 102–111. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Shrader, R.C.; Simon, M. Corporate versus independent new ventures: Resource, strategy, and performance differences. J. Bus. Ventur. 1997 , 12 , 47–66. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Beatty, R.P.; Ritter, J.R. Investment banking, reputation, and the underpricing of initial public offerings. J. Financ. Econ. 1986 , 15 , 213–232. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Brainard, W.C.; Tobin, J. Pitfalls in financial model building. Am. Econ. Rev. 1968 , 58 , 99–122. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bertoni, F.; Colombo, M.G.; Quas, A. The role of governmental venture capital in the venture capital ecosystem: An organizational ecology perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019 , 43 , 611–628. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p |

| (Constant) | 5.672 | 0.000 | 6.067 | 0.000 | 6.091 | 0.000 | 5.88 | 0.000 | 6.073 | 0.000 |

| Total invested capital | −0.25 *** | 0.000 | −0.22 *** | 0.000 | −0.20 *** | 0.000 | −0.20 *** | 0.000 | −0.202 *** | 0.000 |

| Intangible assets | −0.099 * | 0.018 | −0.088 * | 0.038 | −0.086 * | 0.043 | −0.084 * | 0.049 | −0.088 * | 0.039 |

| Leverage ratio | −0.02 | 0.565 | −0.022 | 0.523 | −0.022 | 0.526 | −0.021 | 0.535 | −0.022 | 0.524 |

| Firm age | −0.066 † | 0.096 | −0.05 | 0.215 | −0.045 | 0.272 | −0.049 | 0.225 | −0.05 | 0.215 |

| Number of employees | 0.019 | 0.662 | 0.021 | 0.622 | 0.025 | 0.567 | 0.021 | 0.623 | 0.021 | 0.624 |

| ROA | −0.056 | 0.172 | −0.053 | 0.201 | −0.045 | 0.279 | −0.052 | 0.203 | −0.053 | 0.203 |

| Agriculture and mining industry | −0.047 | 0.193 | −0.064 † | 0.091 | −0.071 † | 0.006 | −0.06 | 0.119 | −0.064 † | 0.095 |

| Construction industry | −0.018 | 0.601 | −0.019 | 0.587 | −0.022 | 0.525 | −0.019 | 0.590 | −0.019 | 0.586 |

| Manufacturing industry | 0.008 | 0.849 | −0.049 | 0.366 | −0.065 | 0.235 | −0.029 | 0.635 | −0.05 | 0.381 |

| Transportation industry | −0.062 † | 0.096 | −0.088 * | 0.032 | −0.095 * | 0.021 | −0.08 † | 0.057 | −0.088 * | 0.036 |

| Wholesale and retail industry | −0.029 | 0.440 | −0.05 | 0.214 | −0.062 | 0.122 | −0.045 | 0.269 | −0.05 | 0.216 |

| Finance and insurance industry | −0.16 *** | 0.000 | −0.19 *** | 0.000 | −0.20 *** | 0.000 | −0.18 *** | 0.000 | −0.19 *** | 0.000 |

| Services industry | 0.157 *** | 0.000 | 0.11 * | 0.023 | 0.095 † | 0.05 | 0.125 * | 0.017 | 0.11 * | 0.029 |

| Public administration industry | −0.027 | 0.432 | −0.035 | 0.313 | −0.048 | 0.174 | −0.033 | 0.350 | −0.035 | 0.313 |

| Number of patents | −0.002 | 0.950 | 0.000 | 0.995 | 0.01 | 0.772 | 0.03 | 0.579 | 0.000 | 0.998 |

| Reputation | 0.027 | 0.463 | 0.019† | 0.600 | 0.014 | 0.715 | 0.021 | 0.566 | 0.023 | 0.765 |

| R&D expense | 0.225 *** | 0.000 | 0.221 *** | 0.000 | 0.363 *** | 0.000 | 0.225 *** | 0.000 | 0.221 *** | 0.000 |

| Initial invested round | −0.089 † | 0.086 | −0.117 * | 0.049 | −0.061 | 0.370 | −0.09 | 0.158 | ||

| R&D expense × Round | −0.162 * | 0.033 | ||||||||

| Patent × Round | −0.046 | 0.454 | ||||||||

| Reputation × Round | −0.004 | 0.961 | ||||||||

| F-value | 13.699 *** | 13.096 *** | 12.718 *** | 12.427 *** | 12.387 *** | |||||

| R-square | 0.272 | 0.275 | 0.28 | 0.275 | 0.275 | |||||

| Adjusted R-square | 0.252 | 0.254 | 0.258 | 0.253 | 0.252 | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p |

| (Constant) | 5.672 | 0.000 | 6.067 | 0.000 | 6.091 | 0.000 | 5.88 | 0.000 | 6.073 | 0.000 |

| Total invested capital | −0.25 *** | 0.000 | −0.22 *** | 0.000 | −0.20 *** | 0.000 | −0.20 *** | 0.000 | −0.202 *** | 0.000 |

| Intangible assets | −0.099 * | 0.018 | −0.088 * | 0.038 | −0.086 * | 0.043 | −0.084 * | 0.049 | −0.088 * | 0.039 |

| Leverage ratio | −0.02 | 0.565 | −0.022 | 0.523 | −0.022 | 0.526 | −0.021 | 0.535 | −0.022 | 0.524 |

| Firm age | −0.066 † | 0.096 | −0.05 | 0.215 | −0.045 | 0.272 | −0.049 | 0.225 | −0.05 | 0.215 |

| Number of employees | 0.019 | 0.662 | 0.021 | 0.622 | 0.025 | 0.567 | 0.021 | 0.623 | 0.021 | 0.624 |

| ROA | −0.056 | 0.172 | −0.053 | 0.201 | −0.045 | 0.279 | −0.052 | 0.203 | −0.053 | 0.203 |

| Agriculture and mining industry | −0.047 | 0.193 | −0.064 † | 0.091 | −0.071 † | 0.006 | −0.06 | 0.119 | −0.064 † | 0.095 |

| Construction industry | −0.018 | 0.601 | −0.019 | 0.587 | −0.022 | 0.525 | −0.019 | 0.590 | −0.019 | 0.586 |

| Manufacturing industry | 0.008 | 0.849 | −0.049 | 0.366 | −0.065 | 0.235 | −0.029 | 0.635 | −0.05 | 0.381 |

| Transportation industry | −0.062 † | 0.096 | −0.088 * | 0.032 | −0.095 * | 0.021 | −0.08 † | 0.057 | −0.088 * | 0.036 |

| Wholesale and retail industry | −0.029 | 0.440 | −0.05 | 0.214 | −0.062 | 0.122 | −0.045 | 0.269 | −0.05 | 0.216 |

| Finance and insurance industry | −0.16 *** | 0.000 | −0.19 *** | 0.000 | −0.20 *** | 0.000 | −0.18 *** | 0.000 | −0.19 *** | 0.000 |

| Services industry | 0.157 *** | 0.000 | 0.11 * | 0.023 | 0.095 † | 0.05 | 0.125 * | 0.017 | 0.11 * | 0.029 |

| Public administration industry | −0.027 | 0.432 | −0.035 | 0.313 | −0.048 | 0.174 | −0.033 | 0.350 | −0.035 | 0.313 |

| Number of patents | −0.002 | 0.950 | 0.000 | 0.995 | 0.01 | 0.772 | 0.03 | 0.579 | 0.000 | 0.998 |

| Reputation | 0.027 | 0.463 | 0.019 † | 0.600 | 0.014 | 0.715 | 0.021 | 0.566 | 0.023 | 0.765 |

| R&D expense | 0.225 *** | 0.000 | 0.221 *** | 0.000 | 0.363 *** | 0.000 | 0.225 *** | 0.000 | 0.221 *** | 0.000 |

| Initial invested round | −0.089 † | 0.086 | −0.117 * | 0.049 | −0.061 | 0.370 | −0.09 | 0.158 | ||

| R&D expense × Round | −0.162 * | 0.033 | ||||||||

| Patent × Round | −0.046 | 0.454 | ||||||||

| Reputation × Round | −0.004 | 0.961 | ||||||||

| F-value | 13.699 *** | 13.096 *** | 12.718 *** | 12.427 *** | 12.387 *** | |||||

| R-square | 0.272 | 0.275 | 0.28 | 0.275 | 0.275 | |||||

| Adjusted R-square | 0.252 | 0.254 | 0.258 | 0.253 | 0.252 | |||||

Share and Cite

Jeong, J.; Kim, J.; Son, H.; Nam, D.-i. The Role of Venture Capital Investment in Startups’ Sustainable Growth and Performance: Focusing on Absorptive Capacity and Venture Capitalists’ Reputation. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083447

Jeong J, Kim J, Son H, Nam D-i. The Role of Venture Capital Investment in Startups’ Sustainable Growth and Performance: Focusing on Absorptive Capacity and Venture Capitalists’ Reputation. Sustainability . 2020; 12(8):3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083447

Jeong, Jihye, Juhee Kim, Hanei Son, and Dae-il Nam. 2020. "The Role of Venture Capital Investment in Startups’ Sustainable Growth and Performance: Focusing on Absorptive Capacity and Venture Capitalists’ Reputation" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083447

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Corporate Venture Capital Research: Literature Review and Future Directions

Management World

Posted: 9 Jan 2021

Gary Dushnitsky

London Business School; University of Pennsylvania - Management Department

Business School, Sun Yat-sen University; Peking University - Guanghua School of Management

Jiangyong Lu

Peking University

Date Written: November 4, 2020

The innovation and growth of entrepreneurial ventures rely heavily on the availability of both monetary and non-monetary resources. In such a background, corporate venture capital (CVC) has become an indispensable part of the entrepreneurial financing landscape. The rapid development of CVC practice has encouraged plenty of academic works from multiple perspectives. This article offers an integrated review of the current research on CVC in China as well as Europe and the US. To the best of knowledge, it is the first review that integrates findings not only based on CVC patterns in the Western world, but also in the large Chinese market. The review is based on 98 top journal papers published during 1980-2019. We discuss the key concepts and research topics of this group of literature and organize the key findings across five topics: (1) the drivers of corporate’s CVC investments, (2) CVC’s strategic effects on corporate, (3) CVC unit’s organization management, (4) the drivers of entrepreneurial ventures’ choice on CVC, and (5) CVC’s strategic effects on an entrepreneurial venture. By doing so, we identify the research gaps within each topic and discuss the future research opportunities in the Chinese context.

Keywords: Corporate Venture Capital, Venture Capital, Entrepreneurship, Innovation, China

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Gary Dushnitsky (Contact Author)

London business school ( email ).

Sussex Place Regent's Park London, London NW1 4SA United Kingdom

HOME PAGE: http://faculty.london.edu/gdushnitsky/index.html

University of Pennsylvania - Management Department ( email )

The Wharton School Philadelphia, PA 19104-6370 United States

Business School, Sun Yat-sen University ( email )

No. 66, Gongchang Rd., Guangming Dist. Shenzhen, Guangdong 518107 China

Peking University - Guanghua School of Management ( email )

Peking University Beijing, Beijing 100871 China

Peking University ( email )

No. 38 Xueyuan Road Haidian District Beijing, Beijing 100871 China

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, entrepreneurship & finance ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Econometric Modeling: Corporate Finance & Governance eJournal

Environment for innovation ejournal, innovation finance & accounting ejournal.

Venture Capital’s Role in Financing Innovation: What We Know and How Much We Still Need to Learn

Venture capital is associated with some of the most high-growth and influential firms in the world. Academics and practitioners have effectively articulated the strengths of the venture model. At the same time, venture capital financing also has real limitations in its ability to advance substantial technological change. Three issues are particularly concerning to us: 1) the very narrow band of technological innovations that fit the requirements of institutional venture capital investors; 2) the relatively small number of venture capital investors who hold, and shape the direction of, a substantial fraction of capital that is deployed into financing radical technological change; and 3) the relaxation in recent years of the intense emphasis on corporate governance by venture capital firms. While our ability to assess the social welfare impact of venture capital remains nascent, we hope that this article will stimulate discussion of and research into these questions.

Harvard Business School’s Division of Research provided funding for this work. Terrence Shu provided excellent research assistance. The ideas in this essay draw, among other sources, on those in Gompers and Lerner (2001a), Kerr, Nanda, and Rhodes-Kropf (2014), Lerner (2012), and Ivashina and Lerner (2019). We thank Gordon Hanson, Enrico Moretti, Tim Taylor, and Heidi Williams for valuable feedback. We owe a debt of gratitude to Paul Gompers, Bill Janeway, Steve Kaplan, Victoria Ivashina, Matthew Rhodes-Kropf, William Sahlman, and especially Felda Hardymon for many helpful conversations over the years. We thank Jeremy Greenwood for pointing out the Arrow interview. Lerner has received compensation from advising institutional investors in venture capital funds, venture capital groups, and governments designing policies relevant to venture capital. All errors are our own. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

Published Versions

Working groups, more from nber.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Advertisement

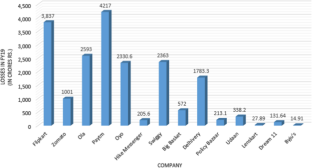

VC Funded Start-Ups in India: Innovation, Social Impact, and the Way Forward

- Perspective

- Published: 22 May 2022

- Volume 17 , pages 104–113, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Kshitija Joshi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2588-065X 1 ,

- Deepak Chandrashekar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9128-3418 2 ,

- Krishna Satyanarayana ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9577-0558 2 &

- Apoorva Srinivas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8937-0862 2

1017 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Venture Capital (VC) is regarded as one of the most powerful financial innovations of the twentieth century. Although in the initial years, the VC-funded start-ups in India faced challenges of scaling up, off-late, both Initial Public Offerings and Mergers and Acquisitions have emerged as viable options for growth and international expansion. Given this context, this paper tries to understand the overall impact of the valuations and VC funding on the components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem—and its repercussions on the overall economic situation in the country. Specifically, the paper examines the recent state of start-up valuations, losses being carried forward, and proposes some long-term implications emanating out of the current practices. It further contemplates on the influence of current business models followed by the VC-funded start-ups on the society and labor market, as well as examines the impact of VC funding on wealth creation at the Bottom of the Pyramid and on innovation. Based on the review of the above critical issues, it proposes pragmatic next steps to be taken by the policy-makers and practitioners to ensure a much more inclusive and equitable growth of the sector and economy.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Source: Dasgupta ( 2020 )

Similar content being viewed by others

Venture Capital Funding of Companies in the Context of Innovative Economic Development

Entrepreneurial Finance

Venture’s economic impact in australia.

Agarwal, S., Ghosh, P., Li, J., & Ruan, T. (2020). Digital payments and consumption: Evidence from the 2016 Demonetization in India. Available at SSRN 3641508 .

Aiginger, K., Bärenthaler-Sieber, S., & Vogel, J. (2013). Competitiveness under new perspectives (No. 44). WWW for Europe Working Paper .

Bain Consulting. (2014). India Private Equity Report. Retrieved from: http://www.bain.com/Images/BAIN_REPORT_India_Private_Equity_Report_2014.pdf . Accessesd 01 Dec 2021

Baum, J. A. (1989). Liabilities of newness, adolescence, and obsolescence: Exploring age dependence in the dissolution of organizational relationships and organizations. Proceedings of the Administrative Science Association of Canada, 10 (5), 1–10.

Google Scholar

Bernier, M., & Plouffe, M. (2019). Financial innovation, economic growth, and the consequences of macroprudential policies. Research in Economics, 73 (2), 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rie.2019.04.003

Article Google Scholar

Bottazzi, L., & Da Rin, M. (2002). Venture capital in Europe and the financing of innovative companies. Economic Policy , 17 (34), 229–270, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344676

Certo, S. T. (2003). Influencing initial public offering investors with prestige: Signaling with board structures. Academy of Management Review, 28 (3), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040731

Chatterji, A., Delecourt, S., Hasan, S., & Koning, R. (2019). When does advice impact startup performance? Strategic Management Journal, 40 (3), 331–356. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2987

Chemmanur, T. J., Loutskina, E., & Tian, X. (2014). Corporate venture capital, value creation, and innovation. The Review of Financial Studies, 27 (8), 2434–2473. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhu033

Cocca, T. D. (2005) What made the internet bubble burst? A butterfly flapping its wings, or how little things can make a big difference . Social Science Research Network (April 2005). Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com

Da Rin, M., Nicodano, G., & Sembenelli, A. (2006). Public policy and the creation of active venture capital markets. Journal of Public Economics, 90 (8–9), 1699–1723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2005.09.013

Dasgupta, R. (2020). These billion dollar Indian start-ups are losing over 200 crores rupees a year . Flop2hit.com. Retrieved from flop2hit.com/insights/loss-making-startups-india/. Accessed 01 Dec 2021

Dash, S. (2020). OYO founder Ritesh Agarwal admits the share buyback in 2019 was ‘bad timing’ . Business Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.in/business/startups/news/oyo-founder-ritesh-agarwal-admits-the-share-buyback-in-2019-was-bad-timing/articleshow/75125466.cms . Accessed 01 Dec 2021

DeLong, J. B., & Magin, K. (2006). A short note on the size of the dot-com bubble . National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper 12011. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w12011/w12011.pdf

Fehn, R., & Fuchs, T. (2003). Capital market institutions and venture capital: Do they affect unemployment and labor demand?. Available at SSRN 388642 .

Félix, E. G. S., Pires, C. P., & Gulamhussen, M. A. (2013). The determinants of venture capital in Europe—Evidence across countries. Journal of Financial Services Research, 44 (3), 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-012-0146-y

Fitzgibbon Jr., J. E. (1996). ‘‘Yahoo! Jumps 152% in Day One,’’ IPO Reporter, April 22, 1996. Retrieved from http://www.lexisnexis.com

Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2001). The venture capital revolution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15 (2), 145–168. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.2.145

Goodnight, G. T., & Green, S. (2010). Rhetoric, risk, and markets: The dot-com bubble. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 96 (2), 115–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335631003796669

Greenspan, A. (1996). Remarks by Chairman Alan Greenspan at the Annual Dinner and Francis Boyer Lecture of the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, DC. Federal Reserve Board , December 5, 1996.

Hart, S. L., & Christensen, C. M. (2002). The great leap: Driving innovation from the base of the pyramid. MIT Sloan Management Review, 44 (1), 51.

Huggins, R., & Izushi, H. (2015). The competitive advantage of Nations: Origins and journey. Competitiveness Review, 25 (5), 458–470. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-06-2015-0044

Huggins, R., & Thompson, P. (2017). Introducing regional competitiveness and development: Contemporary theories and perspectives . Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783475018

Book Google Scholar

Impact Investors Council Report. (2020). 2020 in Retrospect. India Impact Investment Trends. Retrieved from https://iiic.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IIC-2020-in-Retrospect-Final.pdf . Accessed 14 Dec 2021

Indo-Asian News Service. (2021). Unicorns flipping to avoid Indian regulations. Retrieved from https://www.mid-day.com/technology/article/unicorns-flipping-to-avoid-indian-regulations-23190090 . Accessed 03 Mar 2022

Venture Intelligence. (2020). Database on private company financials, transactions & valuations for India . Retrieved from http://www.ventureintelligence.com

Joshi, K. (2018). Emergence and persistence of high-tech start-up clusters: An empirical study of Six Indian clusters. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness, 13 (1), 15–34.

Joshi, K. (2020). The economics of venture capital firm operations in India . Cambridge University Press.

Joshi, K. A., & Bala Subrahmanya, M. H. (2014). What drives Venture Capital fundraising in India: An empirical analysis of systematic and non-systematic factors. In 2014 IEEE international conference on management of innovation and technology (pp. 35–40). IEEE.

Joshi, K., & Chandrashekar, D. (2018). IPO/M&A exits by venture capital in India: Do agency risks matter? Asian Journal of Innovation and Policy, 7 (3), 534–563. https://doi.org/10.7545/ajip.2018.7.3.534

Kenney, R. F. M., & Florida, R. (2000). Silicon valley and route 128 won’t save us. California Management Review, 33 (1), 68–88.

Leo, L. (2021). PharmEasy buys 66% stake in Thyrocare. Livemint.com. Retrieved from https://www.livemint.com/companies/news/pharmeasy-buys-66-stake-in-thyrocare-11624644197444.html . Accessed 01 Dec 2021.

Lerner, J. (2012). The architecture of innovation: The economics of creative organizations . Harvard Business Press.

Miloud, T., Aspelund, A., & Cabrol, M. (2012). Startup valuation by venture capitalists: An empirical study. Venture Capital, 14 (2–3), 151–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2012.667907

Momaya, K. S. (2018). Innovation capabilities and firm competitiveness performance: Thinking differently about future. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness, 13 (1), 3–9.

Momaya, K. S. (2019). The past and the future of competitiveness research: A review in an emerging context of innovation and EMNEs. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness, 14 , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42943-019-00002-3

Mustafa, R., & Werthner, H. (2011). Business models and business strategy—Phenomenon of explicitness. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness, 6 (1), 14–29.

NASSCOM—Zinnov Start-up Report. (2020). Indian Tech Start-up Ecosystem—On march to a trillion dollar digital economy . NASSCOM, New Delhi, India.

NASSCOM—Zinnov Start-up Report. (2019). Indian tech start-up ecosystem—Leading tech in the 20s . NASSCOM, New Delhi, India.

MoneyControl News. (2021). Zomato IPO listing | Food delivery giant makes a stellar debut with nearly 66% premium, at Rs 125.85. Retrieved from https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/ipo/zomato-ipo-listing-food-delivery-giant-crosses-rs-1-lakh-crore-m-cap-after-stellar-debut-with-nearly-53-premium-7210471.html . Accessed 01 Dec 2021.

Nielsen, (2019) Connected Commerce. The Neilson Company (US) LLC. https://www.nielsen.com/wpcontent/uploads/sites/3/2019/04/connected-commerce-report.pdf . Accessed 16 May 2022.

Novet, J. (2021). Amazon’s cloud division reports 32% revenue growth . CNBC.com. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/29/aws-earnings-q1-2021.html . Accessed 01 Dec 2021.

Ozmel, U., Reuer, J. J., & Gulati, R. (2013). Signals across multiple networks: How venture capital and alliance networks affect interorganizational collaboration. Academy of Management Journal, 56 (3), 852–866. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0549

PNGrowth. (2016). A 3-day bootcamp for software product entrepreneurs, iSPIRT Foundation, Bangalore, India. Retrieved from https://pn.ispirt.in/tag/pngrowth/

Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nation . The Free Press.

Rajan, A. T., Koserwal, P., & Keerthana, S. (2014). The Global epicenter of impact investing: An analysis of social venture investments in India. The Journal of Private Equity, 17 (2), 37–50.

Ravi, S., Gustafsson-Wright, E., Sharma, P., & Boggild-Jones, I. (2019). The promise of impact investing in India . Brookings India Research Paper No. 072019.

Romain, A., van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2004). The economic impact of venture capital. Working paper: WP-CEB04/14, Centre Emile Bernheim, Research Institute in Management Studies, Solvay Business School, Bruxelles, Belgium

Samila, S., & Sorenson, O. (2011). Venture capital, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93 (1), 338–349.

Schwienbacher, A. (2008). Innovation and venture capital exits. The Economic Journal, 118 (533), 1888–1916. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02195.x

SEBI. (2015). Alternate capital raising platform . Retrieved from http://www.sebi.gov.in/cms/sebi_data/attachdocs/1427713523817.pdf . Accessed 01 Dec 2021

SEBI. (2019). Framework for issuance of Differential Voting Rights (DVR) Shares . Retrieved from https://www.sebi.gov.in/sebi_data/meetingfiles/aug-2019/1565346231044_1.pdf . Accessed 01 Dec 2021

Shah, S., & Peermohamed, A. (2021). Byju's acquires Aakash Educational Services in nearly $1-billion deal . The Economic Times. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/startups/byjus-to-acquire-aakash-educational-services-in-700-million-deal/articleshow/81910598.cms . Accessed 01 Dec 2021

Sharma, S., Singh, A. K., & Singh, A. P. (2020). Innovation at the bottom of the pyramid: Empowering rickshaw pullers. South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases, 9 (2), 168–177.

Subbaraman, K., & Mishra, P. (2014). With $1 billion in a year, team India is just fabulous: Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/services/retail/with-1-billion-in-a-year-team-india-is-just-fabulous-amazon-ceo-jeff-bezos/articleshow/43756389.cms . Accessed 03 Mar 2022

The Indian Express. (2021). Byju’s list of acquisitions: Great Learning, Epic, Aakash Educational Services, WhiteHat Jr and more . Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/business/startups/byjus-list-of-aquisitions-great-learning-epic-aakash-educational-services-toppr-whitehat-jr-and-more-7424898/ . Accessed 01 Dec 2021.

Tornikoski, E. T., & Newbert, S. L. (2007). Exploring the determinants of organizational emergence: A legitimacy perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 22 (2), 311–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.12.003

World Bank. (2018). Retrieved from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/629571528745663168/pdf/Volumes-1-AND-2-India-SCD-Realising-the-promise-of-prosperity-31MAY-06062018.pdf

Zhao, W., Wang, A., Chen, Y., & Liu, W. (2021). Investigating inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem through the lens of bottom of the pyramid (BOP) theory: Case study of Taobao village in China. Chinese Management Studies, 15 (3), 613–640. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-05-2020-0210

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge and thank all the anonymous reviewers and the editors in particular for their valuable and detailed feedback which has enabled the authors to significantly improve the quality of the paper.

There has been no funding received from any sources toward the creation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nomura International, London, UK

Kshitija Joshi

Indian Institute of Management Bangalore, Bangalore, India

Deepak Chandrashekar, Krishna Satyanarayana & Apoorva Srinivas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KJ and DC conceptualized the study. KJ prepared the draft of the article. While DC and KS revised the article, AS assisted DC and KS with material facts and review inputs. All the authors have read the article, and concurred on the content in the article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Krishna Satyanarayana .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest, including financial and non-financial interests, or competing interests to declare that are relevant to this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Joshi, K., Chandrashekar, D., Satyanarayana, K. et al. VC Funded Start-Ups in India: Innovation, Social Impact, and the Way Forward. JGBC 17 , 104–113 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42943-022-00055-x

Download citation

Received : 18 December 2021

Accepted : 28 April 2022

Published : 22 May 2022

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s42943-022-00055-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Venture capital

- Labor contracts

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

A Systems View Across Time and Space

- Open access

- Published: 05 March 2022

Empirical examination of relationship between venture capital financing and profitability of portfolio companies in Uganda

- Ahmed I. Kato ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1811-6138 1 &

- Chiloane-Phetla E. Germinah 1

Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship volume 11 , Article number: 30 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5535 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

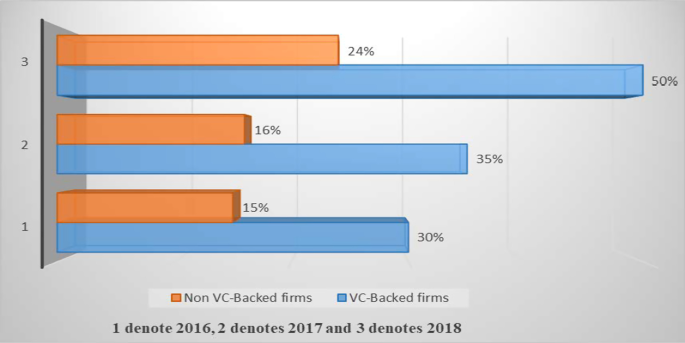

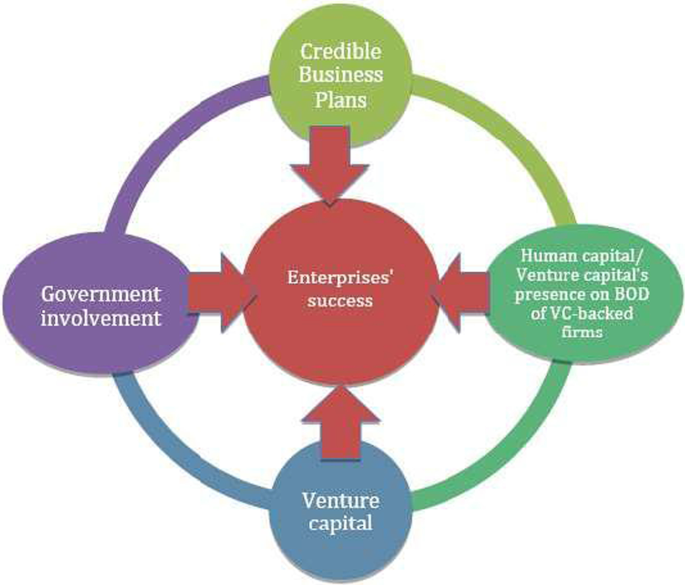

In recent times, venture capital (VC) financing has evolved as an alternative feasible funding model for young innovative companies. Existing studies focus on whether VC enhances profitability. While helpful, this body of work does not address a critical question: whether VC firms are more profitable than non-VC firms. The co-existence of both VC and non VC firms in Africa provides an opportunity to address this question. Accordingly, this paper sought to extend the understanding of the relationship between VC financing and the profitability of portfolio companies in Uganda, a rapidly growing VC market. We utilised a mixed methods approach, which involved quantitative data collected from 68 key VC stakeholders, and qualitative data collected from 16 semi-structured face-to-face interviews. The results confirm the superior performance of VC-financed enterprises when compared to non-VC-financed enterprises. The study makes a vital contribution by offering a diversified framework for enterprise success. The framework will assist VC firms in evaluating and customising funding programmes that can propel early-stage firms’ success in Uganda, and in similar emerging economies. Secondly, our results contribute to extant knowledge about recent developments in Uganda’s VC industry and how it influences the profitability trends of SMEs, also in similar emerging economies.

Introduction

In recent times, venture capital (VC) financing has evolved as the most feasible funding model for young innovative companies. VC firms provide the needed capital in exchange for equity shares in the portfolio companies (Amornsiripanitch et al., 2019 ; Gompers & Lerner, 1999 , Gompers et al., 2020 ; Hirukawa & Ueda, 2008 ; Kato & Tsoka, 2020 ; KPMG & EAVCA, 2019 ; Li & Zahra, 2012 ; SAVCA, 2011 ). Seen from a different standpoint, the contribution of VC to the profitability of early-stage enterprises has not been extensively deliberated among scholars in developing countries, therefore, inadequate evidence is available to acknowledge its impact on the growth of small firms (Ernst & Young, 2016 ; Shanthi et al., 2018 ). In this context, this paper sought to extend the understanding of the role VC in boosting the profitability of portfolio companies in Uganda.

Tykvova ( 2018 ) disclosed that the VC finance framework is not a one-size-fits-all framework. Venture capitalists (VCs) select only companies with high growth potential, and consequently, only a few start-up firms qualify for VC investment. While several studies highlight the benefit of VC investment to young companies, the relationship between VC financing and the profitability of the portfolio companies has been under-researched. As a result, a review of previous research offers inadequate conclusions to account for these differences in performance, moreover, many of these studies focused mainly on developed economies.

VC firms and practitioners typically utilise profitability as the principal financial measure to project the success of the portfolio companies (Emerah & Abomeh, 2020 ). However, some scholars criticise this approach to measuring business performance, because it is restricted to past performance. In addition, it is regarded as an unrealistic technique of treating depreciation and amortisation as part of the company expenses, yet it does not involve direct cash outflows. That said, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with demonstrated profits find it easy to inspire VC investors that are experienced in financing high-risk entrepreneurial firms. VCs make investments in portfolio companies in which they earn returns of between 20 and 30% from the invested capital (Gompers & Lerner, 1999 ). Nevertheless, the concept of VC financing has remained misunderstood in Uganda, despite the vital role it can play in the country’s economy.

Although VC has surged globally in the last 20 years, in, for instance, the United States of America (US), Europe, Canada and China, it has largely focused on the technological sectors, with a nominal allotment of funds to the manufacturing and agro-business sectors that form a colossal share of the SME ecosystem, especially in developing economies, such as Uganda (AVCA, 2020 ; Kato & Tsoka, 2020 ; SAVCA, 2014 ). Thus, only a few portfolio companies have the opportunity to be financed by VC investors, hence, widening the financing gap. Likewise, Ekanem et al. ( 2019 ) observed that VCs transplanted the Silicon Valley model to emerging markets without making meticulous adjustments to reflect the needs of their business environment. This VC myopia has been identified as hampering SMEs’ growth.

Furthermore, few empirical studies have engaged the mixed technique for data collection, moreover, a significant number of empirical studies were conducted 20 years into the past (Gompers & Lerner, 1999 ; Lerner, 2010 ). Prior literature suggests that most of the research assessing the impact of VC on the performance of SMEs essentially engaged business owners/ managers as the key respondents (Biney, 2018 ; Kwame, 2017 ). Therefore, the present study is distinct as it focuses on all the key players in the VC market. The research adopted a mixed method approach and presents a current understanding of the impact of VC on the profitability of the portfolio companies in the public domain. Worse still, these studies largely present results from advanced economies, henceforth, widening the literature gap that compels demand for future research in Africa. In addition, Uganda’s VC market is under-explored, with little evidence to explain how VC financing has influenced SMEs’ performance (Kato & Tsoka, 2020 ; UIA, 2016 ).

Therefore, we reviewed the current literature to identify existing gaps in our current understanding that may provide a foundation for this study. We also reviewed the successful experiences of the VC landscape from developed economies, and conflicting experiences of duplications globally. The paper was guided by two fundamental research questions:

Does venture capital financing spur the profitability growth of the portfolio companies?

How does the venture capitalists’ involvement influence the success of the portfolio companies?

This paper makes four major contributions: firstly, the paper highlights the demand for government to enhance VC supply to early-stage firms, as well as to create a favourable investment environment which will inspire foreign VC firms to invest in the country. This may involve government support to reduce the taxes levied on capital gains on the disposal of business assets during initial public offerings (IPOs) or trade sales. Secondly, the results from this study will benefit the VCs in their efforts to make ideal investment decisions to enhance VC market development. Thirdly, the study makes a vital contribution to knowledge by offering a diversified framework for enterprise success in emerging economies. The framework is expected to benefit the key players in the VC market in their efforts to evaluate and customise sufficient funding programmes that can propel the success of early-stage firms. Finally, this paper also extends our knowledge about recent developments in the VC industry and how it influences the profitability trends of SMEs in emerging economies, such as in Uganda.

The rest of the article is divided into five sections. The next section presents the theoretical literature review, while " Empirical literature review and hypotheses development " section discusses the empirical literature review and hypotheses development. " Research design " section describes the research design. Finally, " Empirical results and discussion " section presents the empirical results.

The theoretical literature review

Agency theory demonstrates the nexus between the VCs who are the principals in the VC contract and the business entrepreneurs (agents), delegated to work on behalf of the VCs. The principal–agent relationship (VC contract) is established when the entrepreneurs agree with VCs to invest in the start-up firms in exchange for equity shares (Bertoni et al., 2019 ; Cumming et al., 2017 ).

Hα1: The venture capitalists’ involvement in the portfolio companies influences their success

The principal–agent problem postulates interrelated conflicts of interest which could emerge in the execution of the contract. This often arises at the time when VCs exit the company through either trade sale or initial public offerings (IPOs), leading the agents into divergence from the best interests of the principal. However, VCs are aware of such barriers that may have behaviour or outcome-based impediments to their interests. Therefore, VC investors insist on stringent control measures and monitoring aspects to guard their business interests through secure minority seats on SMEs’ board of directors (BOD). They maintain a sound business and add value to portfolio companies to recover worthy return on investment (ROE) shares (Cumming & Johan, 2016 ). It is well documented that misunderstandings usually emerge at the exit of the VCs, particularly if this is not well managed from the inception stage. There is noticeable principal–agent conflict that emanates from information asymmetries and fear of the business owner losing control over their investments (Amit et al., 1998 ).

That being said, the VC contract is vital to guard against eventual disputes between the portfolio managers and VCs. The VC financing concept resonates well with the agency theory (Hellmann & Puri, 2002 . This certainly requires SMEs to agree with VCs in order to access the financing needed for their growth and expansion, thus, enforcing VC contracts to protect the interests of both parties.

Hα1: Venture capital financing model spurs the profitability growth of the portfolio companies

The principal–agent relationship concept has been proven to stimulate SMEs’ performance in terms of sales revenue profitability, return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA). This theory provides a firm foundation for our research hypothesis. However, imperfections in the market indicate that this assumption is not fully valid. Pragmatic evidence has disclosed that start-up firms seek external financing sources only if their retained earnings are insufficient to meet their business needs (Myers & Majluf, 1984 ). In addition, some entrepreneurs may not welcome VCs in their business because it compromises their control power, hence they are compelled to depend on retained earnings although they may not sufficient to foster the SME’s growth. Therefore, it is not usually accurate for VCs to assume that the entrepreneur may not abide by the VC contract, and therefore, it may be unnecessary to set the stringent rules in VC contracts. That seemingly appears to be biased, having no consideration for the fears of the entrepreneurs, specifically in the appropriation of profits.

Empirical literature review and hypotheses development

This section delivers a detailed review of the extant literature that underwrites the relationship between VC finance and the profitability of portfolio companies to inform and elucidate our insights. The paper primarily describes the central concepts of VC and the theoretical framework underlying its influence on the performance of VC-financed companies, which provides the foundation for the study.

Venture capital and the profitability growth of portfolio companies

One of the very first studies assessing VC-financed enterprises’ performance, was piloted by the Venture Economics Incorporation for the US General Accounting Office in 1982. The study disclosed that VC-backed companies realised tremendous growth in sales turnover, employment creation, and tax payments, if compared to other companies. In line with the benefits of VC financing, the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) ( 2021 ) discovered that the VC-backed companies grew faster than their national industry counterparts in terms of employment, sales, and wages. Similar results were also obtained in Europe (KPMG & EAVCA, 2019 ), where venture-backed companies achieved a yearly sales growth of 35%, compared to the 14% of other associated European public firms, and employment grew 30.5%. Therefore, such mixed conclusions necessitate a novel empirical study that would be able to fill these literature gaps.