University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Blackboard Learn

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

- University of Arkansas

Literature Reviews

- Qualitative or Quantitative?

- Getting Started

- Finding articles

- Primary sources? Peer-reviewed?

- Review Articles/ Annual Reviews...?

- Books, ebooks, dissertations

Qualitative researchers TEND to:

Researchers using qualitative methods tend to:

- t hink that social sciences cannot be well-studied with the same methods as natural or physical sciences

- feel that human behavior is context-specific; therefore, behavior must be studied holistically, in situ, rather than being manipulated

- employ an 'insider's' perspective; research tends to be personal and thereby more subjective.

- do interviews, focus groups, field research, case studies, and conversational or content analysis.

Image from https://www.editage.com/insights/qualitative-quantitative-or-mixed-methods-a-quick-guide-to-choose-the-right-design-for-your-research?refer-type=infographics

Qualitative Research (an operational definition)

Qualitative Research: an operational description

Purpose : explain; gain insight and understanding of phenomena through intensive collection and study of narrative data

Approach: inductive; value-laden/subjective; holistic, process-oriented

Hypotheses: tentative, evolving; based on the particular study

Lit. Review: limited; may not be exhaustive

Setting: naturalistic, when and as much as possible

Sampling : for the purpose; not necessarily representative; for in-depth understanding

Measurement: narrative; ongoing

Design and Method: flexible, specified only generally; based on non-intervention, minimal disturbance, such as historical, ethnographic, or case studies

Data Collection: document collection, participant observation, informal interviews, field notes

Data Analysis: raw data is words/ ongoing; involves synthesis

Data Interpretation: tentative, reviewed on ongoing basis, speculative

Quantitative researchers TEND to:

Researchers using quantitative methods tend to:

- think that both natural and social sciences strive to explain phenomena with confirmable theories derived from testable assumptions

- attempt to reduce social reality to variables, in the same way as with physical reality

- try to tightly control the variable(s) in question to see how the others are influenced.

- Do experiments, have control groups, use blind or double-blind studies; use measures or instruments.

Quantitative Research (an operational definition)

Quantitative research: an operational description

Purpose: explain, predict or control phenomena through focused collection and analysis of numberical data

Approach: deductive; tries to be value-free/has objectives/ is outcome-oriented

Hypotheses : Specific, testable, and stated prior to study

Lit. Review: extensive; may significantly influence a particular study

Setting: controlled to the degree possible

Sampling: uses largest manageable random/randomized sample, to allow generalization of results to larger populations

Measurement: standardized, numberical; "at the end"

Design and Method: Strongly structured, specified in detail in advance; involves intervention, manipulation and control groups; descriptive, correlational, experimental

Data Collection: via instruments, surveys, experiments, semi-structured formal interviews, tests or questionnaires

Data Analysis: raw data is numbers; at end of study, usually statistical

Data Interpretation: formulated at end of study; stated as a degree of certainty

This page on qualitative and quantitative research has been adapted and expanded from a handout by Suzy Westenkirchner. Used with permission.

Images from https://www.editage.com/insights/qualitative-quantitative-or-mixed-methods-a-quick-guide-to-choose-the-right-design-for-your-research?refer-type=infographics.

- << Previous: Books, ebooks, dissertations

- Last Updated: Sep 5, 2024 4:04 PM

- URL: https://uark.libguides.com/litreview

- See us on Instagram

- Follow us on Twitter

- Phone: 479-575-4104

About Systematic Reviews

Are Systematic Reviews Qualitative or Quantitative?

Automate every stage of your literature review to produce evidence-based research faster and more accurately.

A systematic review is designed to be transparent and replicable. Therefore, systematic reviews are considered reliable tools in scientific research and clinical practice. They synthesize the results using multiple primary studies by using strategies that minimize bias and random errors. Depending on the research question and the objectives of the research, the reviews can either be qualitative or quantitative. Qualitative reviews deal with understanding concepts, thoughts, or experiences. Quantitative reviews are employed when researchers want to test or confirm a hypothesis or theory. Let’s look at some of the differences between these two types of reviews.

To learn more about how long it takes to do a systematic review , you can check out the link to our full article on the topic.

Differences between Qualitative and Quantitative Reviews

The differences lie in the scope of the research, the methodology followed, and the type of questions they attempt to answer. Some of these differences include:

Research Questions

As mentioned earlier qualitative reviews attempt to answer open-ended research questions to understand or formulate hypotheses. This type of research is used to gather in-depth insights into new topics. Quantitative reviews, on the other hand, test or confirm existing hypotheses. This type of research is used to establish generalizable facts about a topic.

Type of Sample Data

The data collected for both types of research differ significantly. For qualitative research, data is collected as words using observations, interviews, and interactions with study subjects or from literature reviews. Quantitative studies collect data as numbers, usually from a larger sample size.

Data Collection Methods

To collect data as words for a qualitative study, researchers can employ tools such as interviews, recorded observations, focused groups, videos, or by collecting literature reviews on the same subject. For quantitative studies, data from primary sources is collected as numbers using rating scales and counting frequencies. The data for these studies can also be collected as measurements of variables from a well-designed experiment carried out under pre-defined, monitored conditions.

Data Analysis Methods

Data by itself cannot prove or demonstrate anything unless it is analyzed. Qualitative data is more challenging to analyze than quantitative data. A few different approaches to analyzing qualitative data include content analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. The goal of all of these approaches is to carefully analyze textual data to identify patterns, themes, and the meaning of words or phrases.

Quantitative data, since it is in the form of numbers, is analyzed using simple math or statistical methods. There are several software programs that can be used for mathematical and statistical analysis of numerical data.

Presentation of Results

Learn more about distillersr.

(Article continues below)

Final Takeaway – Qualitative or Quantitative?

3 reasons to connect.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 8, 2024 11:22 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Types of Literature Reviews

What Makes a Systematic Review Different from Other Types of Reviews?

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

- Creating the Search

- Search Filters and Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing and Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

| Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or mode | Seeks to identify most significant items in the field | No formal quality assessment. Attempts to evaluate according to contribution | Typically narrative, perhaps conceptual or chronological | Significant component: seeks to identify conceptual contribution to embody existing or derive new theory | |

| Generic term: published materials that provide examination of recent or current literature. Can cover wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness. May include research findings | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Mapping review/ systematic map | Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints | No formal quality assessment | May be graphical and tabular | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. May identify need for primary or secondary research |

| Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching. May use funnel plot to assess completeness | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/ exclusion and/or sensitivity analyses | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | Numerical analysis of measures of effect assuming absence of heterogeneity | |

| Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies | Requires either very sensitive search to retrieve all studies or separately conceived quantitative and qualitative strategies | Requires either a generic appraisal instrument or separate appraisal processes with corresponding checklists | Typically both components will be presented as narrative and in tables. May also employ graphical means of integrating quantitative and qualitative studies | Analysis may characterise both literatures and look for correlations between characteristics or use gap analysis to identify aspects absent in one literature but missing in the other | |

| Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics | May or may not include comprehensive searching (depends whether systematic overview or not) | May or may not include quality assessment (depends whether systematic overview or not) | Synthesis depends on whether systematic or not. Typically narrative but may include tabular features | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies | May employ selective or purposive sampling | Quality assessment typically used to mediate messages not for inclusion/exclusion | Qualitative, narrative synthesis | Thematic analysis, may include conceptual models | |

| Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research | Completeness of searching determined by time constraints | Time-limited formal quality assessment | Typically narrative and tabular | Quantities of literature and overall quality/direction of effect of literature | |

| Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research) | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints. May include research in progress | No formal quality assessment | Typically tabular with some narrative commentary | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. Attempts to specify a viable review | |

| Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives | Aims for comprehensive searching of current literature | No formal quality assessment | Typically narrative, may have tabular accompaniment | Current state of knowledge and priorities for future investigation and research | |

| Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesis research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/exclusion | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; uncertainty around findings, recommendations for future research | |

| Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis’ | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Minimal narrative, tabular summary of studies | What is known; recommendations for practice. Limitations | |

| Attempt to include elements of systematic review process while stopping short of systematic review. Typically conducted as postgraduate student assignment | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; uncertainty around findings; limitations of methodology | |

| Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results | Identification of component reviews, but no search for primary studies | Quality assessment of studies within component reviews and/or of reviews themselves | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; recommendations for future research |

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Planning Your Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 23, 2024 3:40 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/systematicreviews

Archer Library

Quantitative research: literature review .

- Archer Library This link opens in a new window

- Research Resources handout This link opens in a new window

- Locating Books

- Library eBook Collections This link opens in a new window

- A to Z Database List This link opens in a new window

- Research & Statistics

- Literature Review Resources

- Citations & Reference

Exploring the literature review

Literature review model: 6 steps.

Adapted from The Literature Review , Machi & McEvoy (2009, p. 13).

Your Literature Review

Step 2: search, boolean search strategies, search limiters, ★ ebsco & google drive.

1. Select a Topic

"All research begins with curiosity" (Machi & McEvoy, 2009, p. 14)

Selection of a topic, and fully defined research interest and question, is supervised (and approved) by your professor. Tips for crafting your topic include:

- Be specific. Take time to define your interest.

- Topic Focus. Fully describe and sufficiently narrow the focus for research.

- Academic Discipline. Learn more about your area of research & refine the scope.

- Avoid Bias. Be aware of bias that you (as a researcher) may have.

- Document your research. Use Google Docs to track your research process.

- Research apps. Consider using Evernote or Zotero to track your research.

Consider Purpose

What will your topic and research address?

In The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students , Ridley presents that literature reviews serve several purposes (2008, p. 16-17). Included are the following points:

- Historical background for the research;

- Overview of current field provided by "contemporary debates, issues, and questions;"

- Theories and concepts related to your research;

- Introduce "relevant terminology" - or academic language - being used it the field;

- Connect to existing research - does your work "extend or challenge [this] or address a gap;"

- Provide "supporting evidence for a practical problem or issue" that your research addresses.

★ Schedule a research appointment

At this point in your literature review, take time to meet with a librarian. Why? Understanding the subject terminology used in databases can be challenging. Archer Librarians can help you structure a search, preparing you for step two. How? Contact a librarian directly or use the online form to schedule an appointment. Details are provided in the adjacent Schedule an Appointment box.

2. Search the Literature

Collect & Select Data: Preview, select, and organize

Archer Library is your go-to resource for this step in your literature review process. The literature search will include books and ebooks, scholarly and practitioner journals, theses and dissertations, and indexes. You may also choose to include web sites, blogs, open access resources, and newspapers. This library guide provides access to resources needed to complete a literature review.

Books & eBooks: Archer Library & OhioLINK

| Books | |

Databases: Scholarly & Practitioner Journals

Review the Library Databases tab on this library guide, it provides links to recommended databases for Education & Psychology, Business, and General & Social Sciences.

Expand your journal search; a complete listing of available AU Library and OhioLINK databases is available on the Databases A to Z list . Search the database by subject, type, name, or do use the search box for a general title search. The A to Z list also includes open access resources and select internet sites.

Databases: Theses & Dissertations

Review the Library Databases tab on this guide, it includes Theses & Dissertation resources. AU library also has AU student authored theses and dissertations available in print, search the library catalog for these titles.

Did you know? If you are looking for particular chapters within a dissertation that is not fully available online, it is possible to submit an ILL article request . Do this instead of requesting the entire dissertation.

Newspapers: Databases & Internet

Consider current literature in your academic field. AU Library's database collection includes The Chronicle of Higher Education and The Wall Street Journal . The Internet Resources tab in this guide provides links to newspapers and online journals such as Inside Higher Ed , COABE Journal , and Education Week .

The Chronicle of Higher Education has the nation’s largest newsroom dedicated to covering colleges and universities. Source of news, information, and jobs for college and university faculty members and administrators

The Chronicle features complete contents of the latest print issue; daily news and advice columns; current job listings; archive of previously published content; discussion forums; and career-building tools such as online CV management and salary databases. Dates covered: 1970-present.

Offers in-depth coverage of national and international business and finance as well as first-rate coverage of hard news--all from America's premier financial newspaper. Covers complete bibliographic information and also subjects, companies, people, products, and geographic areas.

Comprehensive coverage back to 1984 is available from the world's leading financial newspaper through the ProQuest database.

Newspaper Source provides cover-to-cover full text for hundreds of national (U.S.), international and regional newspapers. In addition, it offers television and radio news transcripts from major networks.

Provides complete television and radio news transcripts from CBS News, CNN, CNN International, FOX News, and more.

Search Strategies & Boolean Operators

There are three basic boolean operators: AND, OR, and NOT.

Used with your search terms, boolean operators will either expand or limit results. What purpose do they serve? They help to define the relationship between your search terms. For example, using the operator AND will combine the terms expanding the search. When searching some databases, and Google, the operator AND may be implied.

Overview of boolean terms

| Search results will contain of the terms. | Search results will contain of the search terms. | Search results the specified search term. |

| Search for ; you will find items that contain terms. | Search for ; you will find items that contain . | Search for online education: you will find items that contain . |

| connects terms, limits the search, and will reduce the number of results returned. | redefines connection of the terms, expands the search, and increases the number of results returned. | excludes results from the search term and reduces the number of results. |

|

Adult learning online education: |

Adult learning online education: |

Adult learning online education: |

About the example: Boolean searches were conducted on November 4, 2019; result numbers may vary at a later date. No additional database limiters were set to further narrow search returns.

Database Search Limiters

Database strategies for targeted search results.

Most databases include limiters, or additional parameters, you may use to strategically focus search results. EBSCO databases, such as Education Research Complete & Academic Search Complete provide options to:

- Limit results to full text;

- Limit results to scholarly journals, and reference available;

- Select results source type to journals, magazines, conference papers, reviews, and newspapers

- Publication date

Keep in mind that these tools are defined as limiters for a reason; adding them to a search will limit the number of results returned. This can be a double-edged sword. How?

- If limiting results to full-text only, you may miss an important piece of research that could change the direction of your research. Interlibrary loan is available to students, free of charge. Request articles that are not available in full-text; they will be sent to you via email.

- If narrowing publication date, you may eliminate significant historical - or recent - research conducted on your topic.

- Limiting resource type to a specific type of material may cause bias in the research results.

Use limiters with care. When starting a search, consider opting out of limiters until the initial literature screening is complete. The second or third time through your research may be the ideal time to focus on specific time periods or material (scholarly vs newspaper).

★ Truncating Search Terms

Expanding your search term at the root.

Truncating is often referred to as 'wildcard' searching. Databases may have their own specific wildcard elements however, the most commonly used are the asterisk (*) or question mark (?). When used within your search. they will expand returned results.

Asterisk (*) Wildcard

Using the asterisk wildcard will return varied spellings of the truncated word. In the following example, the search term education was truncated after the letter "t."

| Original Search | |

| adult education | adult educat* |

| Results included: educate, education, educator, educators'/educators, educating, & educational |

Explore these database help pages for additional information on crafting search terms.

- EBSCO Connect: Basic Searching with EBSCO

- EBSCO Connect: Searching with Boolean Operators

- EBSCO Connect: Searching with Wildcards and Truncation Symbols

- ProQuest Help: Search Tips

- ERIC: How does ERIC search work?

★ EBSCO Databases & Google Drive

Tips for saving research directly to Google drive.

Researching in an EBSCO database?

It is possible to save articles (PDF and HTML) and abstracts in EBSCOhost databases directly to Google drive. Select the Google Drive icon, authenticate using a Google account, and an EBSCO folder will be created in your account. This is a great option for managing your research. If documenting your research in a Google Doc, consider linking the information to actual articles saved in drive.

EBSCO Databases & Google Drive

EBSCOHost Databases & Google Drive: Managing your Research

This video features an overview of how to use Google Drive with EBSCO databases to help manage your research. It presents information for connecting an active Google account to EBSCO and steps needed to provide permission for EBSCO to manage a folder in Drive.

About the Video: Closed captioning is available, select CC from the video menu. If you need to review a specific area on the video, view on YouTube and expand the video description for access to topic time stamps. A video transcript is provided below.

- EBSCOhost Databases & Google Scholar

Defining Literature Review

What is a literature review.

A definition from the Online Dictionary for Library and Information Sciences .

A literature review is "a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works" (Reitz, 2014).

A systemic review is "a literature review focused on a specific research question, which uses explicit methods to minimize bias in the identification, appraisal, selection, and synthesis of all the high-quality evidence pertinent to the question" (Reitz, 2014).

Recommended Reading

About this page

EBSCO Connect [Discovery and Search]. (2022). Searching with boolean operators. Retrieved May, 3, 2022 from https://connect.ebsco.com/s/?language=en_US

EBSCO Connect [Discover and Search]. (2022). Searching with wildcards and truncation symbols. Retrieved May 3, 2022; https://connect.ebsco.com/s/?language=en_US

Machi, L.A. & McEvoy, B.T. (2009). The literature review . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press:

Reitz, J.M. (2014). Online dictionary for library and information science. ABC-CLIO, Libraries Unlimited . Retrieved from https://www.abc-clio.com/ODLIS/odlis_A.aspx

Ridley, D. (2008). The literature review: A step-by-step guide for students . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Archer Librarians

Schedule an appointment.

Contact a librarian directly (email), or submit a request form. If you have worked with someone before, you can request them on the form.

- ★ Archer Library Help • Online Reqest Form

- Carrie Halquist • Reference & Instruction

- Jessica Byers • Reference & Curation

- Don Reams • Corrections Education & Reference

- Diane Schrecker • Education & Head of the IRC

- Tanaya Silcox • Technical Services & Business

- Sarah Thomas • Acquisitions & ATS Librarian

- << Previous: Research & Statistics

- Next: Literature Review Resources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 11:19 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ashland.edu/quantitative

Archer Library • Ashland University © Copyright 2023. An Equal Opportunity/Equal Access Institution.

- Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research

Research can be quantitative or qualitative or both:

- A quantitative systematic review will include studies that have numerical data.

- A qualitative systematic review derives data from observation, interviews, or verbal interactions and focuses on the meanings and interpretations of the participants. It may include focus groups, interviews, observations and diaries.

Video source: UniversityNow: Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research

For more information on searching for qualitative evidence see:

Booth, A. (2016). Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: A structured methodological review. Systematic Reviews, 5 (1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13643-016-0249-X/TABLES/5

- << Previous: Study Types & Terminology

- Next: Assess for Quality and Bias of Studies >>

- Adelphi University Libraries

- Common Review Types

- Integrative Reviews

- Scoping Reviews

- Rapid Reviews

- Meta-Analysis/Meta-Synthesis

- Selecting a Review Type

- Types of Questions

- Key Features and Limitations

- Is a Systematic Review Right for Your Research?

- Guidelines for Student Researchers

- Training Resources

- Register Your Protocol

- Handbooks & Manuals

- Reporting Guidelines

- PRESS 2015 Guidelines

- Search Strategies

- Selected Databases

- Grey Literature

- Handsearching

- Citation Searching

- Screening Studies

- Study Types & Terminology

- Reducing Bias

- Quality Assessment/Risk of Bias Tools

- Tools for Specific Study Types

- Data Collection/Extraction

- Broad Functionality Programs & Tools

- Search Strategy Tools

- Deduplication Tools

- Screening Tools

- Data Extraction & Management Tools

- Meta Analysis Tools

- Books on Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Review Articles in the Databases

- Systematic Review Journals

- More Resources

- Evidence-Based Practice Research in Nursing This link opens in a new window

- Citation Management Programs

- Last Updated: Sep 3, 2024 11:43 AM

- URL: https://libguides.adelphi.edu/Systematic_Reviews

How to write a Literature Review: Quantitative vs qualitative method

- Literature review process

- Purpose of a literature review

- Evaluating sources

- Managing sources

- Request a literature search

- Selecting the approach to use

Quantitative vs qualitative method

- Summary of different research methodologies

- Research design vs research methodology

- Diagram: importance of research

- Attributes of a good research scholar

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

| Reliability | Same findings upon replication? Test-retest & interrater reliability | Dependability; Trustworthiness; Consistency | Similar context yields similar findings? Inquiry audit |

| Internal validity | Measured what intention was? Experimental control; statistical triangulation | Credibility | Compatibility between respondents’ and reported perceptions? Prolonged engagement; member checks; quality record; narrative triangulation |

| External validity | Generalisability to population? Random sampling | Transferability | Applicable to other cases and contexts? Purposive sampling; detailed descriptions of process |

| ‘Objectivity’ | Reflecting own views? Control over subjective factors | Confirmability | Findings not function of biases of researcher? Audit trail; trust & rapport with subject; intersubjectivity |

| Replicability | Can next researcher replicate the study? Peer reviewed publication | Replicability | Clear description of procedures? Appropriate peer-reviewed publication |

Source : Golafshani, 2003

- << Previous: Selecting the approach to use

- Next: Summary of different research methodologies >>

- Last Updated: Aug 22, 2024 3:46 PM

- URL: https://libguides.unisa.ac.za/literature_review

Faculty / Staff Search

Department / unit search.

- Student Services

- Catalogue & Collections

- Research Support

- My Library Account

- Videos and How-Tos

- typesofliteraturereviews

Videos & How-Tos

- YouTube Playlist

- Email us about Videos & How-Tos

Literature Reviews, Introduction to Different Types of

There are many different types of literature reviews, each with its own approach, analysis, and purpose. To confuse matters, these types aren't named consistently. The following are some of the more common types of literature reviews.

These are more rigorous, with some level of appraisal:

- The Systematic Review is important to health care and medical trials, and other subjects where methodology and data are important. Through rigorous review and analysis of literature that meets a specific criteria, the systematic review identifies and compares answers to health care related questions. The systematic review may include meta-analysis and meta-synthesis, which leads us to...

- The Quantitative or Qualitative Meta-analysis Review can both make up the whole or part of systematic review(s). Both are thorough and comprehensive in condensing and making sense of a large body of research. The quantitative meta-analysis reviews quantitative research, is objective, and includes statistical analysis. The qualitative meta-analysis reviews qualitative research, is subjective (or evaluative, or interpretive), and identifies new themes or concepts.

These don't always include a formal assessment or analysis:

- The Literature Review (see our Literature Review video) or Narrative Review often appears as a chapter in a thesis or dissertation. It describes what related research has already been conducted, how it informs the thesis, and how the thesis fits into the research in the field. (See https://student.unsw.edu.au/writing-critical-review for more information.)

- The Critical Review is like a literature review, but requires a more detailed examination of the literature, in order to compare and evaluate a number of perspectives.

- The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation or research proposal. It is conducted before the research begins, and sets the stage for this research by highlighting gaps in the literature, and explaining the need for the research about to be conducted, which is presented in the remainder of the article.

- The Conceptual Review groups articles according to concepts, or categories, or themes. It identifies the current 'understanding' of the given research topic, discusses how this understanding was reached, and attempts to determine whether a greater understanding can be suggested. It provides a snapshot of where things are with this particular field of research.

- The State-of-the-Art Review is conducted periodically, with a focus on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic, and highlights where are there still disagreements.

Source: Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26 (2), 91-108. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Contact us for more assistance

1151 Richmond Street London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 3K7 Tel: 519-661-2111 Privacy | Web Standards | Terms of Use | Accessibility

About the Libraries

Library Accessibility

Library Privacy Statement

Land Acknowledgement

Support the Libraries

How to Operate Literature Review Through Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis Integration?

- Conference paper

- First Online: 05 May 2022

- Cite this conference paper

- Eduardo Amadeu Dutra Moresi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6058-3883 13 ,

- Isabel Pinho ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1714-8979 14 &

- António Pedro Costa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4644-5879 14

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems ((LNNS,volume 466))

Included in the following conference series:

- World Conference on Qualitative Research

542 Accesses

3 Citations

Usually, a literature review takes time and becomes a demanding step in any research project. The proposal presented in this article intends to structure this work in an organised and transparent way for all project participants and the structured elaboration of its report. Integrating qualitative and quantitative analysis provides opportunities to carry out a solid, practical, and in-depth literature review. The purpose of this article is to present a guide that explores the potentials of qualitative and quantitative analysis integration to develop a solid and replicable literature review. The paper proposes an integrative approach comprising six steps: 1) research design; 2) Data Collection for bibliometric analysis; 3) Search string refinement; 4) Bibliometric analysis; 5) qualitative analysis; and 6) report and dissemination of research results. These guidelines can facilitate the bibliographic analysis process and relevant article sample selection. Once the sample of publications is defined, it is possible to conduct a deep analysis through Content Analysis. Software tools, such as R Bibliometrix, VOSviewer, Gephi, yEd and webQDA, can be used for practical work during all collection, analysis, and reporting processes. From a large amount of data, selecting a sample of relevant literature is facilitated by interpreting bibliometric results. The specification of the methodology allows the replication and updating of the literature review in an interactive, systematic, and collaborative way giving a more transparent and organised approach to improving the literature review.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

On being ‘systematic’ in literature reviews

Literature Reviews: An Overview of Systematic, Integrated, and Scoping Reviews

Pritchard, A.: Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics? J. Doc. 25 (4), 348–349 (1969)

Google Scholar

Nalimov, V., Mulcjenko, B.: Measurement of Science: Study of the Development of Science as an Information Process. Foreign Technology Division, Washington DC (1971)

Hugar, J.G., Bachlapur, M.M., Gavisiddappa, A.: Research contribution of bibliometric studies as reflected in web of science from 2013 to 2017. Libr. Philos. Pract. (e-journal), 1–13 (2019). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2319

Verma, M.K., Shukla, R.: Library herald-2008–2017: a bibliometric study. Libr. Philos. Pract. (e-journal), 2–12 (2018). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1762

Pandita, R.: Annals of library and information studies (ALIS) journal: a bibliometric study (2002–2012). DESIDOC J. Libr. Inf. Technol. 33 (6), 493–497 (2013)

Article Google Scholar

Kannan, P., Thanuskodi, S.: Bibliometric analysis of library philosophy and practice: a study based on scopus database. Libr. Philos. Pract. (e-journal), 1–13 (2019). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2300/

Marín-Marín, J.-A., Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J., Dúo-Terrón, P., López-Belmonte, J.: STEAM in education: a bibliometric analysis of performance and co-words in Web of Science. Int. J. STEM Educ. 8 (1) (2021). Article number 41

Khalife, M.A., Dunay, A., Illés, C.B.: Bibliometric analysis of articles on project management research. Periodica Polytechnica Soc. Manag. Sci. 29 (1), 70–83 (2021)

Pech, G., Delgado, C.: Screening the most highly cited papers in longitudinal bibliometric studies and systematic literature reviews of a research field or journal: widespread used metrics vs a percentile citation-based approach. J. Informet. 15 (3), 101161 (2021)

Das, D.: Journal of informetrics: a bibliometric study. Libr. Philos. Pract. (e-journal), 1–15 (2021). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5495/

Schmidt, F.: Meta-analysis: a constantly evolving research integration tool. Organ. Res. Methods 11 (1), 96–113 (2008)

Zupic, I., Cater, T.: Bibliometric methods in management organisation. Organ. Res. Methods 18 (3), 429–472 (2014)

Noyons, E., Moed, H., Luwel, M.: Combining mapping and citation analysis for evaluative bibliometric purposes: a bibliometric study. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 50 , 115–131 (1999)

van Rann, A.: Measuring science. Capita selecta of current main issues. In: Moed, H., Glänzel, W., Schmoch, U. (eds.) Handbook of Quantitative Science and Technology Research, pp. 19–50. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht (2004)

Chapter Google Scholar

Garfield, E.: Citation analysis as a tool in journal evaluation. Science 178 , 417–479 (1972)

Hirsch, J.: An index to quantify an individuals scientific research output. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 102, pp. 16569–1657. National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC (2005)

Cobo, M., López-Herrera, A., Herrera-Viedma, E., Herrera, F.: Science mapping software tools: review, analysis and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 62 , 1382–1402 (2011)

Noyons, E., Moed, H., van Rann, A.: Integrating research perfomance analysis and science mapping. Scientometrics 46 , 591–604 (1999)

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., Lim, W.M.: How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 133 , 285–296 (2021)

Aria, M., Cuccurullo, C.: Bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informet. 11 (4), 959–975 (2017)

Aria, M., Cuccurullo, C.: Package ‘bibliometrix’. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/bibliometrix/bibliometrix.pdf . Accessed 10 July 2021

Börner, K., Chen, C., Boyack, K.: Visualisingg knowledge domains. Ann. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 37 , 179–255 (2003)

Morris, S., van der Veer Martens, B.: Mapping research specialities. Ann. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 42 , 213–295 (2008)

Zitt, M., Ramanana-Rahary, S., Bassecoulard, E.: Relativity of citation performance and excellence measures: from cross-field to cross-scale effects of field-normalisation. Scientometrics 63 (2), 373–401 (2005)

Li, L.L., Ding, G., Feng, N., Wang, M.-H., Ho, Y.-S.: Global stem cell research trend: bibliometric analysis as a tool for mapping trends from 1991 to 2006. Scientometrics 80 (1), 9–58 (2009)

Ebrahim, A.N., Salehi, H., Embi, M.A., Tanha, F.H., Gholizadeh, H., Motahar, S.M.: Visibility and citation impact. Int. Educ. Stud. 7 (4), 120–125 (2014)

Canas-Guerrero, I., Mazarrón, F.R., Calleja-Perucho, C., Pou-Merina, A.: Bibliometric analysis in the international context of the “construction & building technology” category from the web of science database. Constr. Build. Mater. 53 , 13–25 (2014)

Gaviria-Marin, M., Merigó, J.M., Baier-Fuentes, H.: Knowledge management: a global examination based on bibliometric analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 140 , 194–220 (2019)

Heradio, R., Perez-Morago, H., Fernandez-Amoros, D., Javier Cabrerizo, F., Herrera-Viedma, E.: A bibliometric analysis of 20 years of research on software product lines. Inf. Softw. Technol. 72 , 1–15 (2016)

Furstenau, L.B., et al.: Link between sustainability and industry 4.0: trends, challenges and new perspectives. IEEE Access 8 , 140079–140096 (2020). Article 9151934

van Eck, N.J., Waltman, L.: VOSviewer manual. Universiteit Leiden, Leiden (2021)

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., Jacomy, M.: Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In: Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference, pp. 361–362. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, San Jose CA (2009)

Chen, C.: How to use CiteSpace. Leanpub, Victoria, British Columbia, CA (2019)

yWorks.: yEd Graph Editor Manual. https://yed.yworks.com/support/manual/index.html . Accessed 13 July 2020

Moresi, E.A.D., Pierozzi Júnior, I.: Representação do conhecimento para ciência e tecnologia: construindo uma sistematização metodológica. In: 16th International Conference on Information Systems and Technology Management, TECSI, São Paulo SP (2019). Article 6275

Moresi, E.A.D., Pinho, I.: Proposta de abordagem para refinamento de pesquisa bibliográfica. New Trends Qual. Res. 9 , 11–20 (2021)

Moresi, E.A.D., Pinho, I.: Como identificar os tópicos emergentes de um tema de investigação? New Trends Qual. Res. 9 , 46–55 (2021)

Chen, Y.H., Chen, C.Y., Lee, S.C.: Technology forecasting of new clean energy: the example of hydrogen energy and fuel cell. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 4 (7), 1372–1380 (2010)

Ernst, H.: The use of patent data for technological forecasting: the diffusion of CNC-technology in the machine tool industry. Small Bus. Econ. 9 (4), 361–381 (1997)

Chen, C.: Science mapping: a systematic review of the literature. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2 (2), 1–40 (2017)

Prabhakaran, T., Lathabai, H.H., Changat, M.: Detection of paradigm shifts and emerging fields using scientific network: a case study of information technology for engineering. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 91 , 124–145 (2015)

Klavans, R., Boyack, K.W.: Identifying a better measure of relatedness for mapping science. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 57 (2), 251–263 (2006)

Kauffman, J., Kittas, A., Bennett, L., Tsoka, S.: DyCoNet: a Gephi plugin for community detection in dynamic complex networks. PLoS ONE 9 (7), e101357 (2014)

Grant, M.J., Booth, A.: A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 26 (2), 91–108 (2009)

Costa, A.P., Soares, C.B., Fornari, L., Pinho, I.: Revisão da Literatura com Apoio de Software - Contribuição da Pesquisa Qualitativa. Ludomedia, Aveiro Portugal (2019)

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., Smart, P.: Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 14 (3), 207–222 (2003)

Costa, A.P., Amado, J.: Content Analysis Supported by Software. Ludomedia, Oliveira de Azeméis - Aveiro - Portugal (2018)

Pinho, I., Leite, D.: Doing a literature review using content analysis - research networks review. In: Atas CIAIQ 2014 - Investigação Qualitativa em Ciências Sociais, vol. 3, pp. 377–378. Ludomedia, Aveiro Portugal (2014)

White, M.D., Marsh, E.E.: Content analysis: a flexible methodology. Libr. Trends 55 (1), 22–45 (2006)

Souza, F.N., Neri, D., Costa, A.P.: Asking questions in the qualitative research context. Qual. Rep. 21 (13), 6–18 (2016)

Pinho, I., Pinho, C., Rosa, M.J.: Research evaluation: mapping the field structure. Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior (Campinas) 25 , 546–574 (2020)

Costa, A., Moreira, A. de Souza, F.: webQDA - Qualitative Data Analysis (2019). www.webqda.net

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Catholic University of Brasília, Brasília, DF, 71966-700, Brazil

Eduardo Amadeu Dutra Moresi

University of Aveiro, 3810-193, Aveiro, Portugal

Isabel Pinho & António Pedro Costa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eduardo Amadeu Dutra Moresi .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Education and Psychology, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

António Pedro Costa

António Moreira

Department Didactics, Organization and Research Methods, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

Maria Cruz Sánchez‑Gómez

Adventist University of Africa, Nairobi, Kenya

Safary Wa-Mbaleka

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Moresi, E.A.D., Pinho, I., Costa, A.P. (2022). How to Operate Literature Review Through Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis Integration?. In: Costa, A.P., Moreira, A., Sánchez‑Gómez, M.C., Wa-Mbaleka, S. (eds) Computer Supported Qualitative Research. WCQR 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 466. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04680-3_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04680-3_13

Published : 05 May 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-04679-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-04680-3

eBook Packages : Intelligent Technologies and Robotics Intelligent Technologies and Robotics (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Systematic & scoping reviews

Systematic reviews.

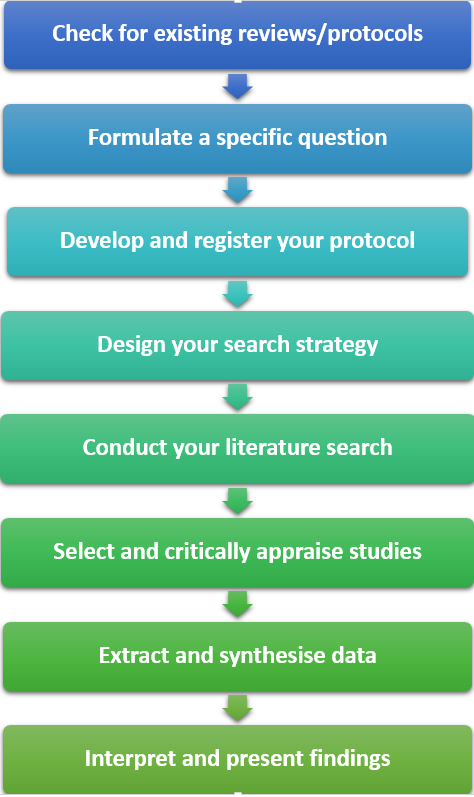

From Munn et al (2018): “Systematic reviews can be broadly defined as a type of research synthesis that are conducted by review groups with specialized skills, who set out to identify and retrieve international evidence that is relevant to a particular question or questions and to appraise and synthesize the results of this search to inform practice, policy and in some cases, further research. .. Systematic reviews follow a structured and pre-defined process that requires rigorous methods to ensure that the results are both reliable and meaningful to end users. .. A systematic review may be undertaken to confirm or refute whether or not current practice is based on relevant evidence, to establish the quality of that evidence, and to address any uncertainty or variation in practice that may be occurring. .. Conducting a systematic review may also identify gaps, deficiencies, and trends in the current evidence and can help underpin and inform future research in the area. .. Indications for systematic reviews are:

- Uncover the international evidence

- Confirm current practice/ address any variation/ identify new practices

- Identify and inform areas for future research

- Identify and investigate conflicting results

- Produce statements to guide decision-making”

Scoping reviews

From Munn et al (2018): “Scoping reviews are an ideal tool to determine the scope or coverage of a body of literature on a given topic and give clear indication of the volume of literature and studies available as well as an overview (broad or detailed) of its focus. Scoping reviews are useful for examining emerging evidence when it is still unclear what other, more specific questions can be posed and valuably addressed by a more precise systematic review. They can report on the types of evidence that address and inform practice in the field and the way the research has been conducted. The general purpose for conducting scoping reviews is to identify and map the available evidence . Purposes for conducting a scoping review:

- To identify the types of available evidence in a given field

- To clarify key concepts/ definitions in the literature

- To examine how research is conducted on a certain topic or field

- To identify key characteristics or factors related to a concept

- As a precursor to a systematic review

- To identify and analyse knowledge gaps”

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology , 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Reviews can be quantitative or qualitative

A quantitative review will include studies that have numerical data. A qualitative review derives data from observation, interviews, or verbal interactions and focuses on the meanings and interpretations of the participants. It will include focus groups, interviews, observations and diaries. See the qualitative research section for more information.

PRISMA Statement

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

The PRISMA 2020 statement was published in 2021 and comprises a 27-item checklist addressing the introduction, methods, results and discussion sections of a systematic review report. It is intended to be accompanied by the PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration document .