Advertisement

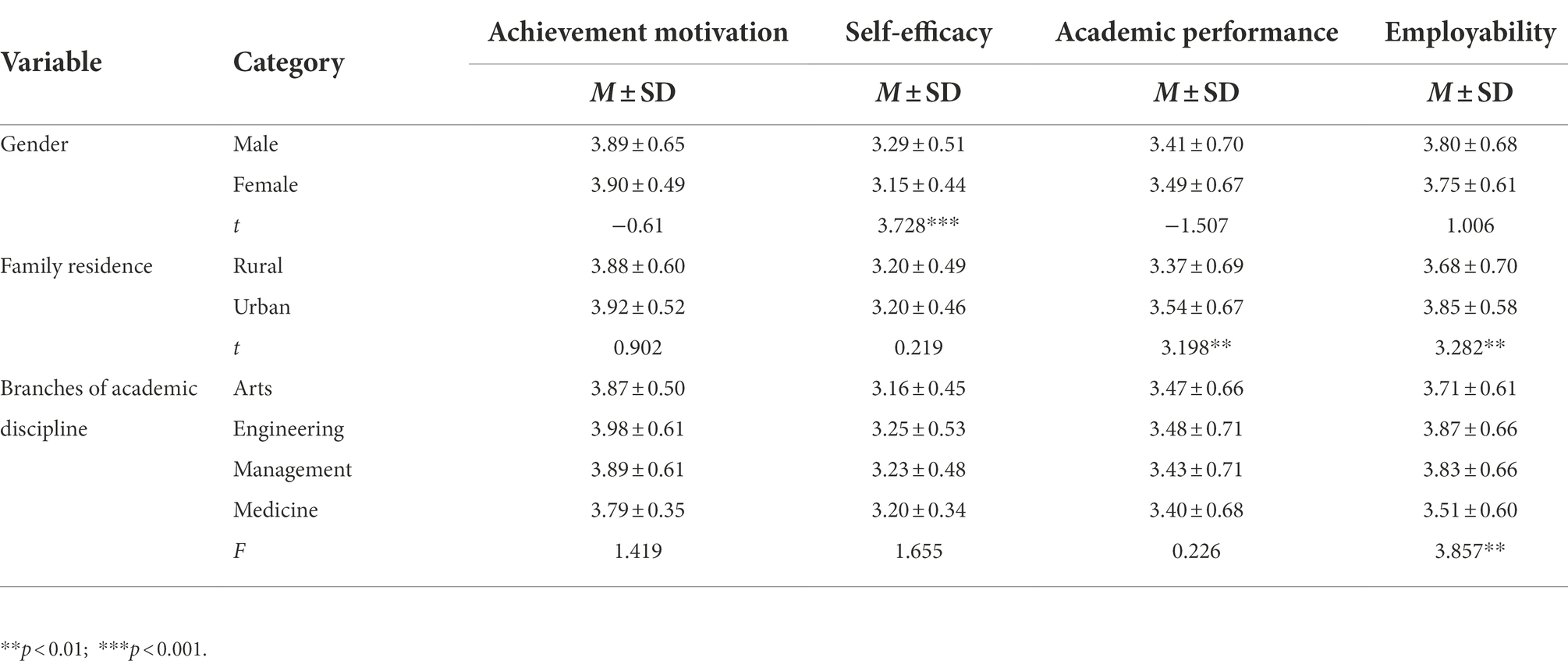

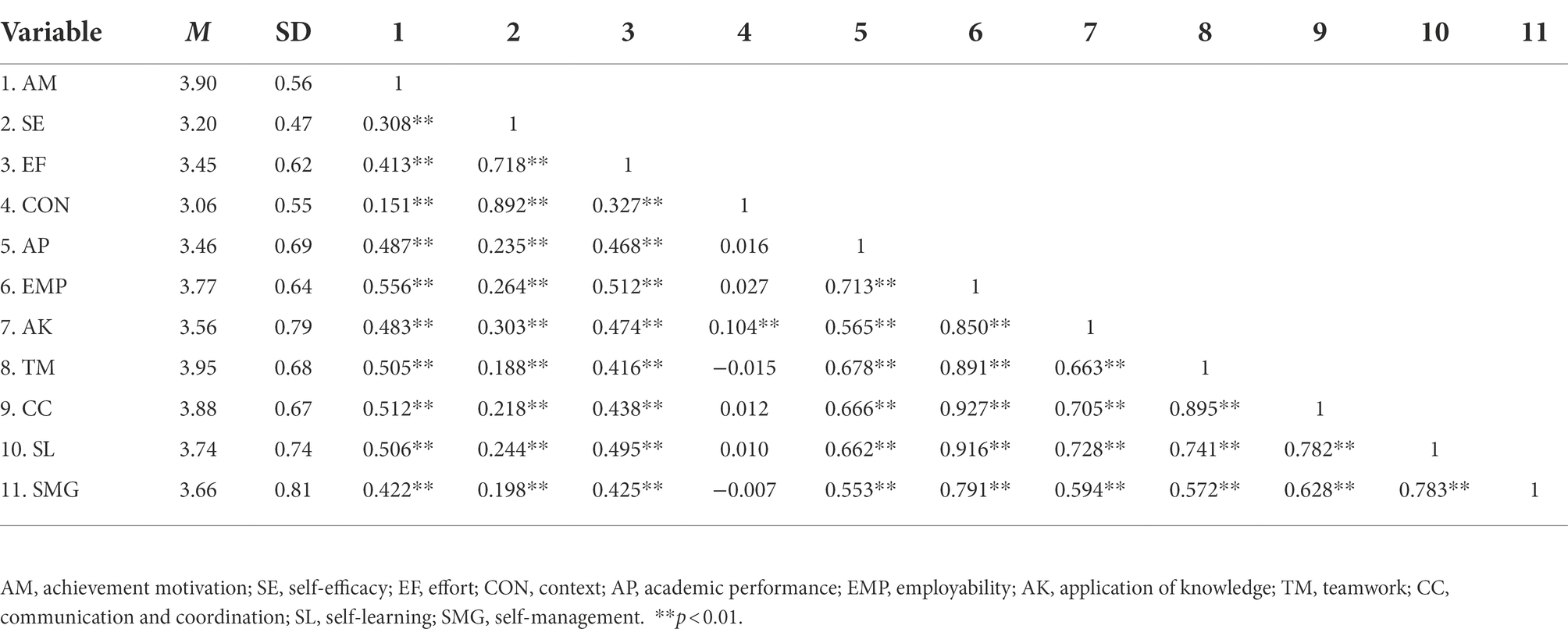

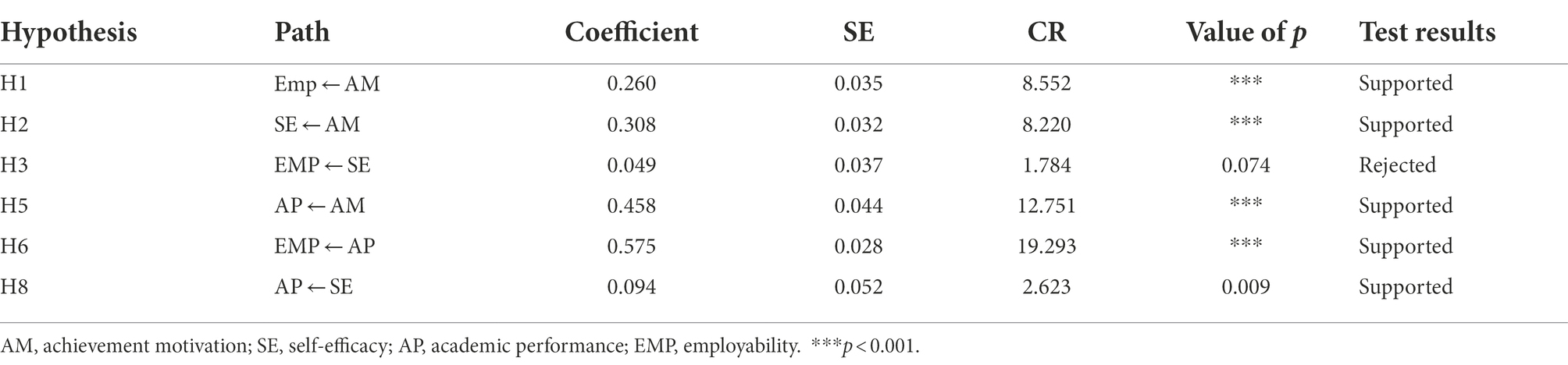

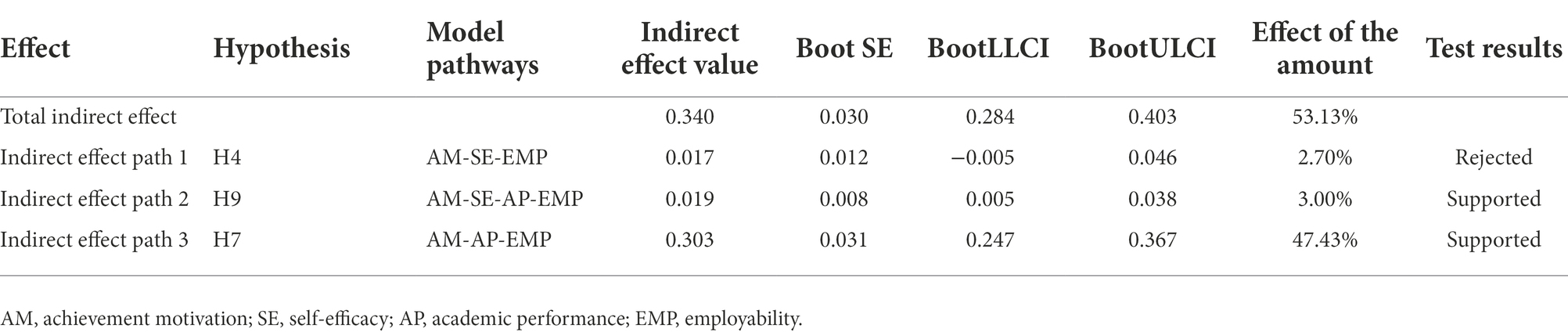

Theories of Motivation in Education: an Integrative Framework

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 30 March 2023

- Volume 35 , article number 45 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Detlef Urhahne ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7709-0011 1 &

- Lisette Wijnia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7395-839X 2

117k Accesses

21 Citations

22 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Several major theories have been established in research on motivation in education to describe, explain, and predict the direction, initiation, intensity, and persistence of learning behaviors. The most commonly cited theories of academic motivation include expectancy-value theory, social cognitive theory, self-determination theory, interest theory, achievement goal theory, and attribution theory. To gain a deeper understanding of the similarities and differences among these prominent theories, we present an integrative framework based on an action model (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). The basic model is deliberately parsimonious, consisting of six stages of action: the situation, the self, the goal, the action, the outcome, and the consequences. Motivational constructs from each major theory are related to these determinants in the course of action, mainly revealing differences and to a lesser extent commonalities. In the integrative model, learning outcomes represent a typical indicator of goal-directed behavior. Associated recent meta-analyses demonstrate the empirical relationship between the motivational constructs of the six central theories and academic achievement. They provide evidence for the explanatory value of each theory for students’ learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Motivation to Learn and Achievement

The Other Half of the Story: the Role of Social Relationships and Social Contexts in the Development of Academic Motivation

Overview of the Educational Motivation Theory: A Historical Perspective

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Motivation is one of the most studied psychological constructs in educational psychology (Koenka, 2020 ). The term is derived from the Latin word “movere,” which means “to move,” as motivation provides the necessary energy to people’s actions (Eccles et al., 1998 ; T. Jansen et al., 2022 ). In the scientific literature, motivation is often defined as “a process in which goal-directed activity is instigated and sustained” (Schunk et al., 2014 , p. 5). Research on academic motivation focuses on explaining why students behave the way they do and how this affects learning and performance (Schunk et al., 2014 ).

Several major theories have been established in research on motivation in education to describe, explain and predict the direction, initiation, intensity, and persistence of learning behaviors (cf. Linnenbrink-Garcia & Patall, 2016 ). Each theory has its own terms and concepts to designate aspects of motivated behavior, contributing to a certain inaccessibility of the field of motivation theories. In addition, motivation researchers create their own terminology, differentiate, and extend existing theoretical conceptions, making it difficult to draw precise boundaries between the models (Murphy & Alexander, 2000 ; Schunk, 2000 ). This leads to the question of whether it would be possible to consider the most important theories of academic motivation against a common background to gain a deeper understanding of the similarities and differences among these prominent theories.

In the past, several researchers have worked to provide an integrative meta-theoretical framework for classifying motivational processes. Hyland’s ( 1988 ) motivational control theory used a system of hierarchically organized control loops to explain the direction and intensity of goal-orientated behavior. Locke ( 1997 ) postulated an integrated model for theories of work motivation, starting from needs, values and personality, and environmental incentives through goal choice and mediating goal and efficacy mechanisms to performance, outcomes, satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Murphy and Alexander ( 2000 ) classified achievement motivation terms into the four domains of goal, interest, intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation, and self-schema. De Brabander and Martens ( 2014 ) tried to predict a person’s readiness for action primarily from positive and negative, affective and cognitive valences in their unified model of task-specific motivation. Linnenbrink-Garcia and Wormington ( 2019 ) proposed perceived competence, task values, and achievement goals as essential categories to study person-oriented motivation from an integrative perspective. Hattie et al. ( 2020 ) grouped various models of motivation around the essential components of person factors (subdivided into self, social, and cognitive factors), task attributes, goals, perceived costs, and benefits. Finally, Fong ( 2022 ) developed the motivation within changing culturalized contexts model to account for instructional, social, future-oriented, and sociocultural dynamics affecting student motivation in a pandemic context.

In this contribution, we present an integrative framework for theories of motivation in education based on an action model (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). The action model is a further development of an idea by Urhahne ( 2008 ) to classify the most commonly cited theories focusing on academic motivation, including expectancy-value theory, social cognitive theory, self-determination theory, interest theory, achievement goal theory, and attribution theory, into a common frame (Schunk et al., 2014 ). We begin with introducing the basic motivational model and then sort the main concepts and terms of the prominent motivation theories into the action model. Associated recent meta-analyses will illustrate the empirically documented value of each theory in explaining academic achievement.

The Basic Motivational Model

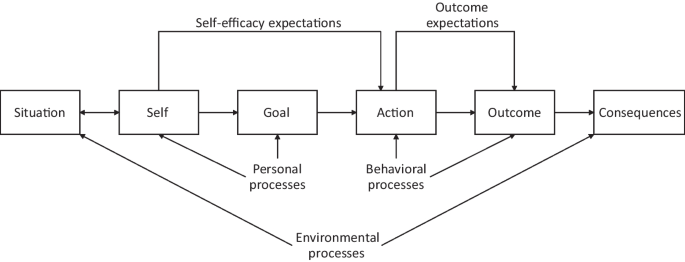

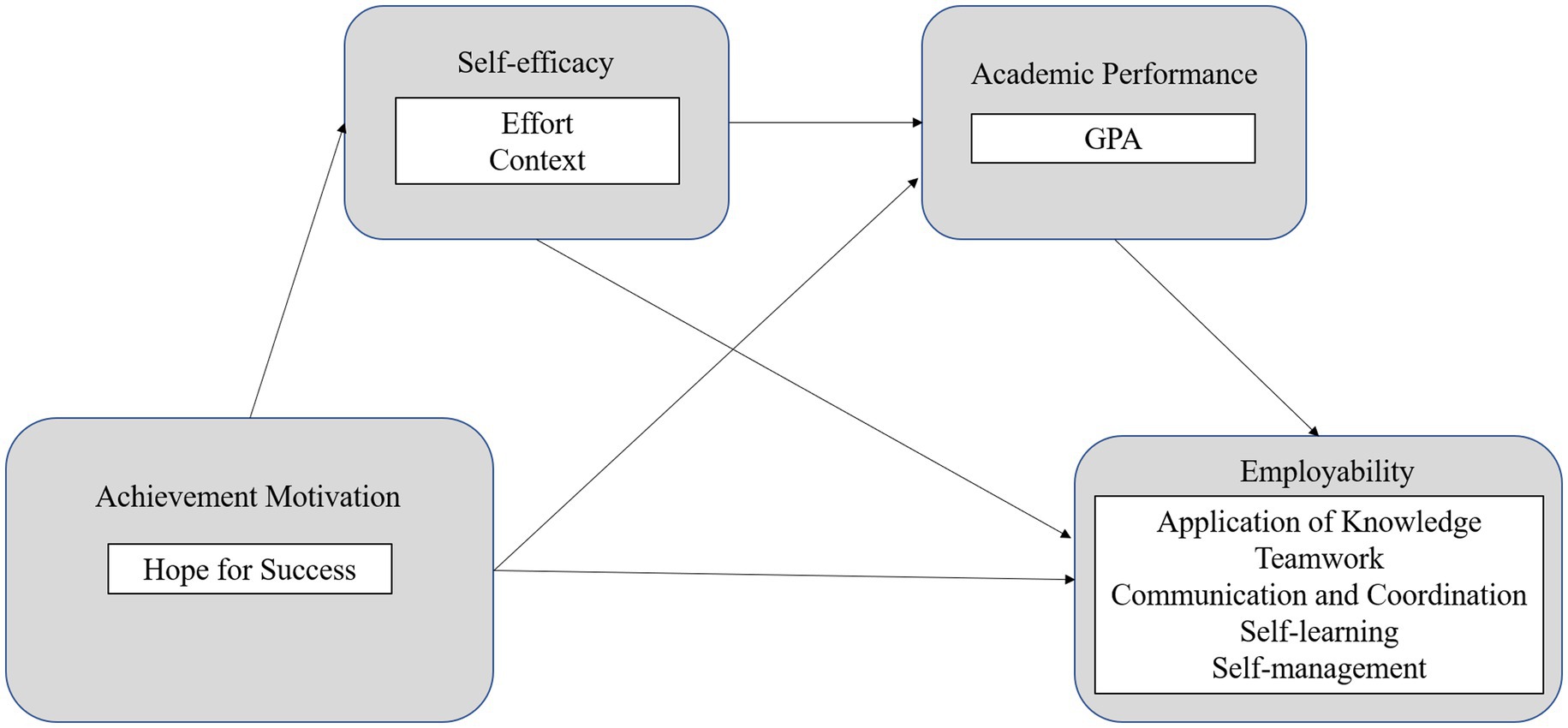

The basic motivational model in Fig. 1 shows the determinants and course of motivated action. The model is grounded on the general model of motivation by Heckhausen and Heckhausen ( 2018 , p. 4) to introduce the universal characteristics of motivated human action. Heckhausen ( 1977 ) had worked early on to organize constructs from different theories into a cognitive model of motivation. The initial model differentiated four types of expectations attached to four different stages in a sequence of events and helped group intrinsic and extrinsic incentive values of an action as well (Heckhausen, 1977 ). Later, Heckhausen and Gollwitzer ( 1987 ) extended the model to the Rubicon model of action phases to define clear boundaries between phases of motivational and volitional mindsets (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2018 ; Gollwitzer et al., 1990 ). The four phases of the Rubicon model can be described as follows: In the predecisional phase of motivation, individuals select or set a goal for action on the basis of their wishes and desires. The postdecisional phase of volition is a time of preparation and planning to translate the goal into action. This is followed by the actional phase of volition that involves the actual process of action. Once the action is completed or abandoned, the postactional phase of evaluating the outcome and its consequences has begun (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). Since the Rubicon model depicts the entire action process from an emerging desire to the final evaluation of the action outcome, it provides a broad basis for classifying various current motivational theories.

The basic motivational model

Specifically, our model proposes that motivated behavior arises from the interaction between the person and the environment (Murray, 1938 ). In Fig. 1 , possible incentives such as the prospect of rewards and opportunities of the situation stimulate the motives, needs, wishes, and emotions of a person’s self, which come to life through generating an action goal (Dweck et al., 2003 ; Roeser & Peck, 2009 ). A person’s current goal is translated into an action at a suitable opportunity. The action is carried out, and the action’s outcome indicates whether and to what extent the intended goal has been achieved. The outcome has to be distinguished from the consequences of the action, which may consist of self- and other evaluations, rewards and punishments, achievement emotions, or effects of the outcome on long-term goals (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). The basic model is intentionally parsimonious and somewhat reflects considerations by Hattie et al. ( 2020 ) on integrating theories of motivation that distinguish between self, goals, task (action), and costs and benefits (consequences) as major dimensions of motivation. Similarities also emerge to Locke ( 1997 ), who bases the integrative model of work motivation theories on a comparable action sequence. The specificities of each component of the basic motivational model are now explained in more detail.

The situation represents the social, cultural, and environmental context in which individuals perform motivated actions (Ford, 1992 ). Recently, there has been a trend within motivation research to place greater emphasis on situating motivation (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ; Nolen, 2020 ; Nolen et al., 2015 ; Pekrun & Marsh, 2022 ; Wentzel & Skinner, 2022 ). Researchers want to better account for the social and cultural differences between persons (Usher, 2018 ) or take note of the embeddedness of individuals in multiple contexts (Nolen et al., 2015 ). The basic motivational model includes these extensions of current motivation theories and refers to the situatedness of motivation. The situation represents the overarching context for the complete action sequence, even though it is depicted in the basic motivational model by only one box. The situation and the person’s self are intimately interwoven, and motivation can be regarded as a result of their interaction (Roeser & Peck, 2009 ). The situation evokes motivational tendencies in the self, and the self contains experiences about the motivation to avoid or master certain situations (King & McInerney, 2014 ).

The self has not played a major role in motivation research for a long time (Weiner, 1990 ). This was partly due to Freud’s psychoanalytic theories, which recognized the id rather than the ego as the motivational driver of behavior. Moreover, behavioristic approaches that characterized motivation and learning as fully controllable from the outside also neglected mental constructs such as the self (McCombs, 1991 ). It was only with the greater prevalence of cognitive and social-cognitive theories that the self found its way back to motivational research (Weiner, 1990 ). The self is now frequently addressed in hypothetical constructs such as self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977 ), self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 1985 ), self-regulation (Bandura, 1988 ), self-theories (Dweck, 1999 ), ego orientation (Nicholls, 1989 ), self-based goals (Elliot et al., 2011 ), self-serving bias (McAllister, 1996 ; Miller & Ross, 1975 ), and identity (Eccles, 2009 ).

In our model, the self is the starting point of motivated action. It enables people to select goals, initiate behaviors, and sustain them until goals are accomplished (Baumeister, 2010 ; McCombs & Marzano, 1990 ; Osborne & Jones, 2011 ). Thus understood, the self is an active agent that translates a person’s basic psychological needs, motives, feelings, values, and beliefs into volitional actions (McCombs, 1991 ; Roeser & Peck, 2009 ). James ( 1999 ) referred to this part of the self as the “I-self,” the thinking and acting person itself, to distinguish it from the “Me-self,” the reflection of oneself through its physical and mental attributes. The “Me-self” is central to constructs such as self-concept, self-worth, or self-esteem (Harter, 1988 ) and remains important in depicting different motivational constructs in the course of action. However, in the basic motivational model, the “I-self” is recognized as the repository of motivational tendencies and the energizer of motivated action (King & McInerney, 2014 ).

This view of the self corresponds with insights from neuroscientific research. In Northoff’s ( 2016 ) basis model of self-specificity, the self, and in particular self-specificity, is viewed as the most fundamental function of the brain. Self-specificity and self-relatedness refers to “the degree to which internal or external stimuli are related to the self” (Hidi et al., 2019 , p. 15) and references the I-self, the self as subject and agent (Christoff et al., 2011 ). Self-specificity involves spontaneous brain activity—the resting state of the brain and independent of specific tasks or stimuli external to the brain—and is viewed as fundamental in influencing basic and higher-order functions, such as perception, the processing of reward, emotion, memory, and decision-making (Hidi et al., 2019 ; Northoff, 2016 ). Furthermore, Sui and Humphreys ( 2015 ) indicated that self-related information processing functions as an “integrative glue” that influences the integration of different stages of processing, such as linking attention to decision-making. Neuroscientific findings, therefore, seem to support the view of the self as the starting point of motivated behavior.

The goal contains the cognitive representation of an action’s anticipated incentives and consequences. Goals are the basis of all motivated behavior (cf. Elliot & Fryer, 2008 ). This view is consistent with Schunk et al. ( 2014 ), who defined motivation as a process to instigate and sustain goal-directed behavior. Cognitive theories on motivation place special emphasis on the goals that people pursue (Elliot & Hulleman, 2017 ). Goals are intentional rather than impulsive, consciously or unconsciously represented, and guide an individual’s behavior. People are not always aware of the various influences on their goals. Sensations, perceptions, thoughts, beliefs, and emotions that affect goal pursuit are potentially experiential, but typically not consciously perceived (Bargh & Gollwitzer, 2023 ; Dweck et al., 2023 ). Goals are closely related to the person’s self. In line with Dweck et al. ( 2003 , p. 239), we assume that “contents of the self—self-defining beliefs and values—come to life through people’s goals.”

The action is carried out to either approach or avoid an anticipatory goal state (Beckmann & Heckhausen, 2018 ). Thus, motivated behavior can be directed to either approach a positive event or avoid a negative one (Elliot & Covington, 2001 ). An action can be brief or extended over a longer period. If an action goal is considered unattainable, it is devalued, and the action is directed toward other more attractive goals (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018 ). The action may or may not be visible to an observer. Thus, to act is to engage in any form of noticeable or indiscernible behavior, especially cognitive behavior, to reach a desired or avoid an undesired goal state.

The outcome is any physical, affective, or social result of an individual’s behavior. The action outcome is an important indicator of mastering a standard of excellence (Heckhausen, 1991 ). It is often accompanied by intrinsic valences such as feelings of self-worth, self-actualization, or appropriate accomplishment (Mitchell & Albright, 1972 ).

The consequences of an action are far more varied than the mere outcome. Vroom’s ( 1964 ) instrumentality theory considered the outcome of an action as instrumental for reaching subsequent consequences. Vroom ( 1964 ) suggested that the valence of an outcome depends on the valence of the consequences. For example, the value of school grades should depend on how the students themselves, classmates, and parents evaluate the grades achieved, what rewards, punishments, and achievement emotions are associated with the school grades, and whether the grades help achieve long-term goals such as moving up to the next grade level. The consequences of an action are often accompanied by extrinsic valences such as authority, prestige, security, promotion, or recognition (Mitchell & Albright, 1972 ).

In addition, the manifold consequences of an action affect the design of future situations and the goals that can be pursued within these situations. New possibilities to act open up and novel incentives of the situation start to interact with the self. A new action sequence, as shown in Fig. 1 , has begun.

In the following sections, we will use the action model to explain and classify six central motivation theories. Motivated action in the educational context serves to attain academic achievement, and we will make use of meta-analyses to underline what is currently known about the predictive strength of the major theoretical models. Academic achievement is certainly not the only reportable variable related to motivation. However, this visible evidence of learning is an appropriate indicator to convince individuals of the theory’s nature and value (Hattie, 2009 ). The role of affective factors in the action model is explained in more detail in the discussion.

Expectancy-Value Theory

Grounded on the research by Tolman ( 1932 ) and Lewin ( 1951 ), expectancy-value theories depict motivation as the result of the feasibility and desirability of an anticipated action (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2018 ; Schnettler et al., 2020 ). The expectancy is usually triggered by the incentives of the situation and expresses the subjective probability of the feasibility of the current action (Atkinson, 1957 ). The value indicates the desirability of an action which is determined by the incentives of the situation and the anticipated consequences of the action. In Atkinson’s ( 1957 ) achievement motivation theory, expectancy and value were assumed to be inversely related. The greater the desirability, the more difficult the feasibility of an action and vice versa. Thus, knowing the subjective probability of success was regarded as sufficient to determine the incentive value of a task. However, it turned out that the assumption of a negative correlation between expectancy and value was not tenable (Wigfield & Eccles, 1992 ). In a more modern view, expectancy and value beliefs are assumed to jointly predict achievement-related choices and performance (Eccles et al., 1983 ; Trautwein et al., 2012 ).

Situated expectancy-value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000 ) is a modern theoretical framework for explaining and predicting achievement-related choices and behavior. Expectancy of success and subjective task values are regarded as proximal explanatory factors determined by a person’s goals and self-schemas. These, in turn, are shaped by the individual’s perception and interpretation of their developmental history and sociocultural background. Eccles and Wigfield ( 2020 ) refer to their theory as situated to highlight the importance of the underlying influences on currently held expectancy and value beliefs.

The expectancy component in the situated model (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ) is called expectation of success (Atkinson, 1957 ; Tolman, 1932 ). It represents individuals’ belief about how well they will do on an upcoming task, targeting the anticipated outcome of an action. The expectancy component of Eccles’ motivation theory shows some similarity to self-concept of ability and self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977 ; Harter, 2015 ; Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2016 ; Schunk & Pajares, 2009 ). However, the expectation of success does not focus on the present ability (Bong & Skaalvik, 2003 ) but the future (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000 ), and it targets the perceived chances of success rather than the perceived probability of performing an action which may lead to success (Bandura, 1977 ; Muenks et al., 2018 ).

The value component of the situated model is divided into three types of value beliefs and three types of costs that contribute to approaching or avoiding certain tasks (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). The three value beliefs are attainment value, intrinsic value, and utility value. The three types of costs are named opportunity costs, effort costs, and emotional costs (cf. Flake et al., 2015 ; Jiang et al., 2018 ).

Attainment value represents the importance of doing well on a task (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). This belief is strongly associated with the person’s self, as aspects of one’s identity are touched upon during performing an important task (Wigfield et al., 2016 ). Intrinsic value is the enjoyment a person gets from doing a task. Intrinsic value is considered a counterpart to intrinsic motivation in self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2009 ) and interest in person-object theory (Krapp, 1999 ). However, enjoyment and interest should not be viewed as synonyms, making differentiations necessary (Ainley & Hidi, 2014 ; Reeve, 1989 ). Utility value is derived from the meaning of a task in achieving current and future goals (Wigfield et al., 2006 ). Accomplishing the task is only a means to an end; therefore, utility value can be considered a form of extrinsic motivation. Utility value is derived from the meaning of a task in achieving current and future goals (Wigfield et al., 2006 ) in social, educational, professional, or everyday contexts (Gaspard et al., 2015 ).

Opportunity costs arise because the time invested in a task is no longer available for other valued activities. Especially in the case of learning, conflicts with other interests threaten learners’ self-regulation, and opportunity costs can be high (Grund & Fries, 2012 ). Effort costs address the perceived effort in pursuing a task and whether it is worthwhile to finish the task at hand (Eccles, 2005 ). Emotional costs include the perceived affective consequences of participating in an academic activity, such as fear of failure or other negative emotional states (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ; Wigfield et al., 2017 ).

Central constructs of the situated expectancy-value framework (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ) can be placed within the basic motivational model (see Fig. 2 ). Expectation of success, a person’s subjective estimate of the chances of obtaining a particular outcome, can be represented as a directed link between self and outcome. The expectation of achieving a future outcome with a certain probability is formed in the self and is directed on the desired outcome of the prospective action. This view of expectancy of success is consistent with Skinner’s ( 1996 ) classification of agent-ends relations as individuals’ beliefs about how well they will do on an upcoming task.

Integrating situated expectancy-value theory into the basic motivational model

Figure 2 further shows that the three task values are linked to different processes in the action model. The attainment value of a task is related to the personal significance of the outcome (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). The higher the relative personal importance of the outcome, the higher the attainment value. More recent analyses show that the attainment value can be divided and measured as the importance of achievement and personal importance related to one’s identity (Gaspard et al., 2015 , 2018 , 2020 ). The self, however, is not the valued object but the importance of accomplishing a task to an individual’s identity (Perez et al., 2014 ). In classifying this construct, we chose to focus more on the importance of the outcome and less on the reference to the self. At this point, however, a different mode of presentation is also conceivable. The intrinsic value of the task is linked to the positive aspects of the action. The more pleasurable the action, the higher the intrinsic value. Eccles and Wigfield ( 2020 ) conceptualized the intrinsic value as the anticipated enjoyment of doing a particular task as well as the experienced enjoyment when performing the task. The utility value of a task is linked to the consequences. The more positive the anticipated consequences of an action, the higher the perceived usefulness. As a form of extrinsic motivation, the utility value does not result from performing the task, but from the anticipated consequences of an action to fulfill an individual’s present or future plans (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ).

The three types of costs also become relevant at different stages in the action process (see Fig. 2 ). Opportunity costs occur when a decision has been made in favor of a certain action. Alternative courses of action are ruled out as soon as a person is committed to a goal (Locke et al., 1988 ). Opportunity costs are consequently linked to the goal of the action. The person’s time and skills, which from now on are put into the pursuit of intentions, are no longer available for other activities (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). Effort costs are tied to the action itself and are based on the anticipated effort of conducting the task. Effort costs rise with the duration and intensity of an action so that the person needs to anticipate whether the desired action is worth the effort required (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ). Finally, emotional costs such as anticipated fear of failure or negative emotional states are connected to the anticipated consequences of an action. These costs arise when the action does not go as desired and are therefore considered as the “perceptions of the negative emotional or psychological consequences in pursuing a task” (Rosenzweig et al., 2019 , p. 622).

Eccles’ expectancy-value framework has often been used to investigate and understand gender differences in motivational beliefs, performance, and career choices, especially in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (Lesperance et al., 2022 ; Parker et al., 2020 ; Wan et al., 2021 ). In contrast, there has been less meta-analytic research as to whether constructs of the expectancy-value model can predict academic achievement. To not preempt other theoretical conceptions, we only report here findings with a clear relation to the Eccles model.

Generally, expectations of success compared to achievement values are stronger predictors of subsequent performance (cf. Wigfield et al., 2017 ). A meta-analysis by Pinquart and Ebeling ( 2020 ) found a moderate association of expectancies for success with both current ( r = .34) and future academic achievement ( r = .41). Conversely, however, past academic performance could also predict expectancies for success ( r = .35). Credé and Phillips ( 2011 ) reported small relationships for a combination of the three task values with GPA ( r = .12) and grades ( r = .17). The relations in meta-analyses were somewhat higher when individual task values were examined. Camacho-Morles et al. ( 2021 ) found an association of r = .27 between activity-related enjoyment represented in the intrinsic value and academic performance. Barroso et al. ( 2021 ) reported a meta-analytic relationship of r = − .28 between math anxiety, as a form of emotional costs, and mathematics achievement.

Social Cognitive Theory

Within the frame of social cognitive theory, Bandura ( 1977 , 1986 , 1997 ) extended the expectancy concept from achievement motivation theory (Atkinson, 1957 ). Expectancy of success, the subjective probability of attaining a particular outcome, was differentiated by means of two beliefs (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006 ; Usher, 2016 ). Competence beliefs take effect when learners consider means and processes to accomplish certain tasks (Skinner, 1996 ). Control beliefs signify the perceived extent to which the chosen means and processes lead to the desired outcomes (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006 ).

For competence beliefs, Bandura ( 1977 ) coined the term self-efficacy to express expectations about one’s capabilities to organize and execute courses of action to produce specific outcomes (Bandura, 1997 ; Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006 ). The belief in self-efficacy is regarded as an essential condition to initiate actions leading to academic success (Klassen & Usher, 2010 ). For control beliefs, Bandura ( 1977 ) used the term outcome expectations to express the perceived relations between possible actions and anticipated outcomes. While expectancy of success sometimes involves competence beliefs, sometimes control beliefs, and sometimes both (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2006 ), Bandura’s construct of self-efficacy has contributed to a necessary differentiation in the course of action and can be viewed as a central variable in research on motivation in education (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2016 ).

Social cognitive theory is much broader than self-efficacy and outcome expectations and assumes a system of interacting personal, behavioral, and environmental factors (Schunk & diBenedetto, 2021 ). The idea that human agency is neither completely autonomous nor completely mechanical, but is subject to reciprocal determinism, plays a decisive role (Linnenbrink-Garcia & Patall, 2016 ). Thus, personal factors such as perceived self-efficacy enable individuals to initiate and sustain behaviors that translate to effects on the environment. Thoughtful reflection on those actions and their impact feeds back to the person and can, in turn, influence their sense of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1989 ).

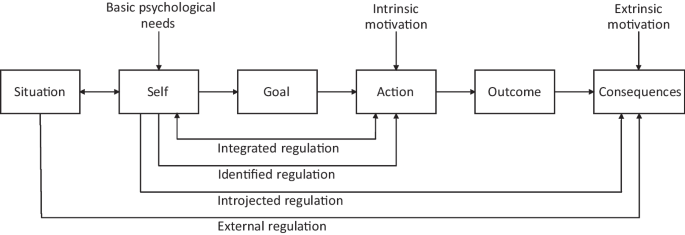

Figure 3 shows how the key components of social cognitive theory fit into the action model. The upper part of Fig. 3 is devoted to expectations. Self-efficacy expectations arise when the self has the necessary capabilities to organize and execute courses of action. Outcome expectations, in contrast, refer to the assessment of whether the anticipated action will lead to the desired outcome. The presentation of the two expectations is consistent with Skinner’s ( 1996 ) view in which self-efficacy expectations are referred to as agent-means relations and outcome expectations are referred to as means-ends relations. The lower part of Fig. 3 depicts the model of reciprocal interactions consisting of personal, behavioral, and environmental processes (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020 ). Personal processes, as described by Schunk and DiBenedetto ( 2020 ) in a publication on motivation and social cognitive theory, are primarily associated with the self and the goal. The self contains information on self-efficacy, values, expectations, attribution patterns and enables social comparison processes. The goal contains standards for self-evaluations of the action’s progress. Behavioral processes such as activity selection, effort, persistence, regulation, and achievement are closely related to action and outcome of the action model. Environmental processes such as acting of social models, providing instructions, or setting standards for action stem, on the one hand, from the situation, where they set the stage for action. Environmental processes are, on the other hand, located in the consequences, where feedback, opportunities for self-evaluation, and rewards indicate an action’s success or failure (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020 ). The listing of the individual components that make up the three interacting processes in reciprocal determinism is not always done in the same way. For example, Schunk and DiBenedetto ( 2021 ) referred to self-efficacy, cognitions, and emotions as personal factors; classroom attendance and task completion as behavioral factors; and classroom, teachers, peers, and classroom climate as environmental factors. However, this does not affect the representation of the three main classes of reciprocal determinism in the basic motivational model and opens up space for the classification of different components.

Integrating social cognitive theory into the basic motivational model

Several meta-analyses have shown that self-efficacy is moderately positively related to academic achievement (Multon et al., 1991 ; Robbins et al., 2004 ). Credé and Phillips ( 2011 ) examined several constructs of social cognitive theory based on the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990 ). Control beliefs showed small positive correlations with college GPA ( r = .12) and current semester grades ( r = .14). However, of all the constructs measured, self-efficacy showed the strongest associations with GPA ( r =. 18) and grades ( r = .30). Further meta-analyses with university students supported the significant but moderate relationship between academic self-efficacy and academic achievement with correlation coefficients of r = .31 (Richardson et al., 2012 ) and r = .33 (Honicke & Broadbent, 2016 ). Sitzmann and Ely ( 2011 ) reported meta-analytic correlations of r = .18 for pre-training self-efficacy and r = .29 for self-efficacy with learning.

To further clarify the direction of the relationship, Sitzmann and Yeo ( 2013 ) conducted an insightful meta-analysis. They were able to show that self-efficacy expectations are more likely to be a product of past performance ( r = .40) than a driver of future performance ( r = .23). Talsma et al. ( 2018 ) supported these findings with a meta-analytic cross-lagged panel study. They found that prior performance exerted a stronger effect on self-efficacy (β = .21) than existing self-efficacy on subsequent performance (β = .07).

Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory by Deci and Ryan ( 1985 , 2000 ) is macro-theory for understanding human motivation, personality, and well-being. The theory has its roots in early explorations of the concept of intrinsic motivation (Deci, 1971 , 1975 ; Ryan & Deci, 2019 ). Self-determination is regarded as the basis for explaining intrinsically motivated behavior where the action is experienced as autonomous and does not rely on controls and reinforcers (Deci & Ryan, 1985 ). Self-determination theory provides a counterweight to expectancy-value theory and social cognitive theory, where the external incentives such as expected or real rewards to motivate behavior are still visible.

The overarching framework of self-determination theory encompasses six mini-theories: basic psychological needs theory, cognitive evaluation theory, organismic integration theory, causality orientations theory, goal contents theory, and relationship motivation theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017 ). Each mini-theory explains specific motivational phenomena that have been tested empirically (Reeve, 2012 ; Ryan & Deci, 2017 ; Vansteenkiste et al., 2010 ; see also Ryan et al., in press ). In the following explanations, we focus on the first three sub-theories with the highest popularity.

Basic psychological needs theory argues that humans are intrinsically motivated and experience well-being when their three innate basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied (Conesa et al., 2022 ; Deci & Ryan, 1985 , 2000 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000a , 2000b , 2017 , 2020 ; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020 ). Autonomy refers to a sense of ownership and the need for behavior to emanate from the self. Competence concerns a person’s need to succeed, grow, and feel effective in their goal pursuits (Deci & Ryan, 2000 ; White, 1959 ). Finally, relatedness refers to establishing close emotional connections to others and a sense of belonging to significant others such as parents, teachers, or peers.

Cognitive evaluation theory describes how the social environment affects intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985 , 2000 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000b , 2017 , 2020 ). The mini-theory states that cognitive evaluation of external rewards impacts learners’ perception of their intrinsically motivated behavior. Rewards perceived as controlling weaken intrinsic motivation, whereas rewards providing informational feedback can strengthen acting on one’s own initiative (Deci et al., 1999 ).

Organismic integration theory focuses on the development of extrinsic motivation toward more autonomous or self-determined motivation through the process of internalization (Ryan & Deci, 2017 ). The mini-theory proposes a self-determination continuum that ranges from intrinsic motivation to amotivation, with several types of extrinsic motivation in between (Deci & Ryan, 1985 , 2000 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000a , 2000b , 2017 , 2020 ). The results from the meta-analysis by Howard et al. ( 2017 ) largely supported the continuum-like structure of self-determination theory. Intrinsically motivated individuals engage in activities because they are fun or interesting, whereas extrinsic motivation concerns all other reasons for engaging in activities. Four types of extrinsic motivation are distinguished, and two of these types are assumed to be higher in quality than the other two (Deci & Ryan, 2008 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000b ).

Integrated and identified regulations are considered high-quality autonomous, extrinsic motivation types characterized by volitional engagement in activities. Integrated regulation is the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation. People with integrated regulation recognize and identify with the activity’s value and find it congruent with their core values and interests (e.g., attending school because it is part of who you are; see Ryan & Deci, 2020 ). In identified regulation, people identify with or personally endorse the value of the activity (e.g., doing schoolwork to learn something from it) and, therefore, experience high degrees of volition.

The other two types of extrinsic motivation are forms of controlled motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2008 ; Ryan & Deci, 2000a , 2000b ). Introjected regulation concerns partially internalized extrinsic motivation; people’s behavior is regulated by an internal pressure to feel pride or self-esteem or to avoid feelings of anxiety, shame, or guilt. Extrinsic regulation refers to behavior regulated by externally imposed rewards and punishments, such as demands from parents or teachers.

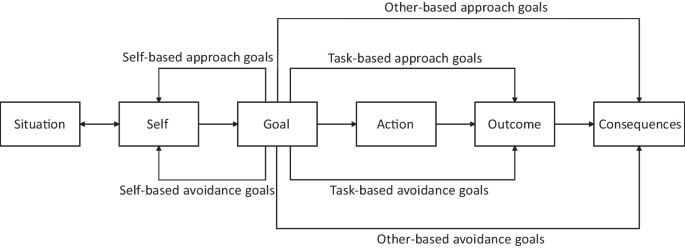

The action model in Fig. 4 shows how core concepts of the self-determination theory fit into the course of action. The three basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and social relatedness are an integral part of the self (Connell & Wellborn, 1991 ). Ryan and Deci ( 2019 ) regarded the self as responsible for assimilating and aligning a person’s internal needs, drives, and emotions to the external determinants of the sociocultural situation. Intrinsic motivation is part of the action when the activity itself is experienced as exciting, interesting, or intrinsically satisfying. On the other hand, extrinsic motivation is tied to an action’s consequences, as externally motivated learners seek pleasant consequences and try to avoid unpleasant ones.

Integrating self-determination theory into the basic motivational model

Forms of extrinsic motivation of the organismic integration theory can be distinguished according to the extent to which the action is integrated into the self. The more internalized the motivation, the more it becomes part of a learner’s identity (Ryan & Deci, 2020 ). In external regulation, there is no involvement of the self, as the person’s actions are entirely determined by the incentives of the situation and the action’s consequences (see Fig. 4 ). In introjected regulation, there is already some ego involvement: The self becomes involved with the consequences of one’s action to experience approval from oneself or others (Ryan & Deci, 2000a ). In identified regulation, the individual starts to value an activity consciously, and the self connects with the action. In integrated regulation, a congruence is established between the self and the self-initiated action (Ryan & Deci, 2000a ). Values and needs of the self are in balance with the autonomous and unconflicted action (see Fig. 4 ). As seen in Fig. 4 , identified and integrated regulation share overlap. In line with this presentation, the meta-analysis by Howard et al. ( 2017 ) showed that integrated regulation was hard to distinguish from intrinsic and identified regulation and called for a revision of the theory by either excluding integrated regulation or finding new ways to operationalize and conceptualize the hypothetical construct.

In line with basic psychological needs theory, the Bureau et al. ( 2022 ) meta-analysis confirmed that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs is positively associated with autonomous forms of motivation. Relative weight analysis showed that the need for competence most strongly predicted intrinsic and identified motivation, followed by the needs for autonomy and social relatedness.

Several meta-analyses investigated the association between the different motivation types and academic achievement, and some of these meta-analyses only reported the association between intrinsic motivation and school performance. For example, Cerasoli et al. ( 2014 ) reported a meta-analytic correlation between intrinsic motivation and school performance of ρ = .26, whereas Richardson et al. ( 2012 ) reported a small positive correlation of r = .17 with the GPA at college or university.

Taylor et al. ( 2014 ) and Howard et al. ( 2021 ) investigated the meta-analytic correlations of the different types of motivation with school performance. Concerning the autonomous motivation types, Taylor et al. ( 2014 ) reported positive associations of intrinsic motivation ( d = .27) and identified regulation ( d = .35) with school achievement. Howard et al. ( 2021 ) also found that both identified and intrinsic motivation were equally positively associated with school performance. However, higher associations were found for self-reported (intrinsic ρ = .32, identified ρ = .29) than for objective performance measures (intrinsic ρ = .13, identified ρ = .11).

Concerning the controlled motivation types, Taylor et al. ( 2014 ) reported weak but significant negative associations with academic achievement for introjected ( d = − .12) and external regulation ( d = − .22). In contrast, Howard et al. ( 2021 ) found that introjected and external regulation were not significantly related to self-reported (introjected ρ = .07, external ρ = − .02) or objective school performance (introjected ρ = − .01, external ρ = − .03).

Interest Theory

Interest stems from the Latin word “interesse” and etymologically indicates that there is something in between. Interest connects two entities that would otherwise be separated from each other. Dewey ( 1913 ) viewed interest as an engagement and absorption of the self with an objective subject matter. In today’s person-object theory (Krapp, 2002 ), interest is similarly understood as a relational concept that builds a connection between a person and an object. Objects of interest can be very diverse and may include tangible things, people, topics, abstract ideas, tasks, events but also activities such as sports (Hidi & Renninger, 2006 ). A prerequisite for interest to arise is an object in the real world and a person who has at least rudimentary but often considerable knowledge about this object (Alexander et al., 1994 ; Renninger & Wozniak, 1985 ; Rotgans & Schmidt, 2017 ). Interest is a unique motivational concept (Hidi, 2006 ) that establishes a link between the objective appearance and the subjective representation of an object and triggers actions with the object of interest.

Being in a state of interest is accompanied by certain intrinsic qualities (Krapp, 2002 ). Interest-driven activities need no external incentives or rewards to be initiated and sustained. Interest is a form of intrinsic motivation that is characterized by the three components of affect, knowledge, and value (Hidi & Renninger, 2006 ) and can thereby be distinguished from related constructs such as curiosity (Berlyne, 1960 ; Donnellan et al., 2022 ; Peterson & Hidi, 2019 ) or flow experience (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ). The affective component of interest is typically associated with a state of pleasant tension, an optimal level of arousal, and positive feelings in the engagement with the object of interest. The cognitive component shows itself in the epistemic tendency to want to learn about the object of interest (Hidi, 1990 ). The value component becomes evident in the object’s connection to the self through the attribution of personal significance (Schiefele, 1991 ).

The most important distinction in interest theory is between long-lasting individual interest and short-term situational interest (Hidi & Renninger, 2006 ; Rotgans & Schmidt, 2018 ). Individual interest describes a motivational disposition toward a particular domain. It resembles a temporally stable personality trait and is an important goal of education concerning developing subject-specific and vocational interests for life-long learning (Hoff et al., 2018 ). Situational interest arises from the stimulus conditions of the environment, without any individual interest of the person having to be simultaneously present. Situational interest provides favorable motivation for learning and leads to increased short-term attention and enhanced information processing (Hidi, 2006 ). This interested turn of the person to certain topics, tasks, or activities is due to favorable characteristics of environmental stimuli such as novelty, importance, or attractiveness and is considered to be well-studied in research on text comprehension (Schraw et al., 2001 ). The change and maintenance of short-term situational interest to long-term individual interest are explicitly described in the four-phase model of interest development (Hidi & Renninger, 2006 ).

It is important to note that both individual and situational interest can be associated with a psychological state of interest (Ainley, 2017 ; Hidi, 2006 ) that arises when individuals interact with the object of interest. This state can be promoted both by the individual interest that a person brings to the situation and situational interest due to salient environmental cues (Knogler, 2017 ). In this state of interest, the two basic components of interest complement and merge with each other (Krapp, 2002 ; Renninger et al., 1992 ).

Figure 5 shows the classification of the three central constructs of interest theory in the action model. Situational interest is triggered by environmental stimuli (Hidi & Renninger, 2006 ) and is thus associated with the situation. This fleeting and malleable psychological state needs support from others or through instructional design to not disappear right away (Renninger & Hidi, 2019 , 2022a ). Individual interest is a relatively enduring disposition of the person to re-engage particular content over time (Hidi & Renninger, 2006 ) and is thus a fixed characteristic of the self. This psychological predisposition is independent of the concrete content and represented as stored knowledge and stored value with relations to the self (Renninger & Hidi, 2022b ). “The self … may also provide an explanation of why interest, once triggered, is then maintained and continues to develop” (Hidi et al., 2019 , p. 28). The state of interest arises in interaction with the object of interest (Knogler, 2017 ) and is connected with the action in the model. This state of interest can be differentiated from a less-developed situational interest. While state of interest refers to an action-related, current experience (Knogler, 2017 ), less-developed situational interest marks the initial phase of a well-developed individual interest (Renninger & Hidi, 2022a ).

Integrating interest theory into the basic motivational model

Individual interest in content or subject matter is a stable predictor of academic achievement. Schiefele et al. ( 1992 ) determined a mean correlation coefficient of r = .31 between interest and academic achievement for studies in K-12 classes. In a more recent large-scale study, Lee and Stankov ( 2018 ) examined the relationship between mathematics interest and mathematics achievement in standardized tests. They found mean within-country correlations of r = .16 and r = .15 for data from PISA 2003 and PISA 2012, respectively. The effect of individual interest on academic achievement remained significant even when researchers controlled for students’ gender, nonverbal intelligence, or socio-economic status (M. Jansen et al., 2016 ). The strongest associations were found in the domains of mathematics and science (M. Jansen et al., 2016 ; Schiefele et al., 1992 ), which seem to be particularly suitable for initiating interventive measures (e.g., Crouch et al., 2018 ; Renninger et al., 2023 ). No meta-analyses are yet known for situational interest. However, Sundararajan and Adesope ( 2020 ) have analyzed how seductive details (i.e., interesting but irrelevant information) can affect learning outcomes. They found an average negative effect of g = − .33 for the relation between seductive details and recall or transfer of presented information.

Achievement Goal Theory

Anyone working as a teacher may have noticed that some students are very interested in learning something new, while others are motivated by obtaining good grades and avoiding poor ones (Eison, 1981 ; Eison et al., 1986 ). This fundamental distinction between individuals concentrating on the process of learning and individuals focusing on the external reasons for learning, can also be found in achievement goal theory (Elliot & Thrash, 2001 ). The theoretical framework has evolved steadily over four decades and is nowadays a key approach in motivation research (Elliot, 2005 ; Elliot & Hulleman, 2017 ; Urdan & Kaplan, 2020 ).

Achievement goals can be characterized by the intention to engage in competence-related behaviors (Elliot & Hulleman, 2017 ). In an attempt to further develop achievement motivation theory, Nicholls ( 1984 ); Nicholls & Dweck, 1979 ) called attention to two types of achievement behavior. Task-oriented individuals pursue the goal of developing high abilities. Ego-oriented learners care deeply about proving high abilities to themselves or others and avoid demonstrating low abilities. Later, the terms mastery goal and performance goal have been established to signify this basic distinction between the two achievement goals (Ames & Archer, 1988 ; Dweck, 1986 ; Elliot & Hulleman, 2017 ).

A first differentiation of the achievement goal theory has been made by including an approach and an avoidance component (Elliot, 1999 ). Research findings made clear that performance-approach goals were mainly associated with adaptive outcomes, whereas performance-avoidance goals were often associated with maladaptive outcomes (Harackiewicz et al., 2002 ). Originally, approach and avoidance components were assumed only for performance goals (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996 ). Later, researchers also addressed mastery avoidance goals, which concerns an individual’s striving to avoid mastering tasks worse than before or avoiding a decline in skills or knowledge (Elliot & McGregor, 2001 ; Van Yperen et al., 2009 ).

A second differentiation became necessary because competence-related behavior can be oriented toward very different standards (Elliot et al., 2011 ). Competencies may be reflected in whether certain tasks are fulfilled, performance is improved, or is better than the performance of others. The 3 × 2 achievement goal model by Elliot et al. ( 2011 ) incorporates the different aims of attaining competencies by differentiating between task-based, self-based, and other-based goals. Task-based goals are oriented toward the absolute demands of a task where the action’s outcome signals the attainment of an absolute standard. Self-based goals are a bit more complicated and require reference back to past performance anchored in the “Me-self” (Elliot et al., 2011 ). Competencies in terms of self-based goals refer to meeting or exceeding intrapersonal evaluation standards. Individuals with other-based goals, however, strive to meet interpersonal evaluation standards and to perform tasks better than others in a normative sense. The full 3 × 2 achievement goal model results from completely crossing absolute, intrapersonal, and interpersonal evaluation standards with approach and avoidance tendencies (Elliot et al., 2011 ).

Furthermore, the empirical distinction of performance goals into normative and appearance goals has gained a lot of popularity (Hulleman et al., 2010 ; Senko & Dawson, 2017 ; Urdan & Mestas, 2006 ). However, performance goals in the sense of seeking normative comparisons express the achievement goal concept of attaining competence much better than demonstrating ability to others (Elliot & Hulleman, 2017 ; Senko, 2019 ; Urdan & Kaplan, 2020 ). Therefore, we omit the distinction between normative and appearance goals in the model representation and report their effects only in the meta-analytic part.

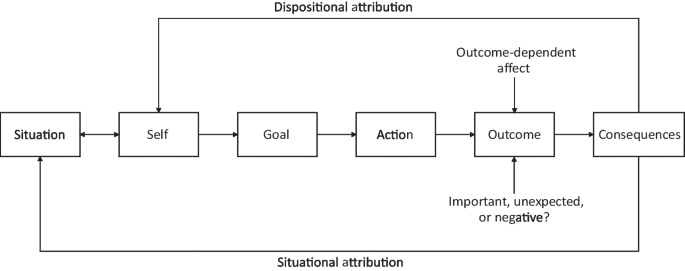

Figure 6 illustrates how the 3 × 2 achievement goal model (Elliot et al., 2011 ) can be placed within the basic motivational model. The arrows in the illustration point to the cognitively represented aim of the action in a particular goal state. In task-based goals, the focus is on striving for a desired outcome or avoiding not to attain a desired outcome (see Fig. 6 ). The conceptualization of task-based goals is consistent with the original idea of mastery goals of understanding the content and doing well (Ames & Archer, 1988 ). To represent mastery goals, however, a second arrow would be appropriate from the goal to the action and not just to the outcome of learning. Through the action and the continuous comparison of the current and intended outcome of the action, the individual can master the task, develop new competencies or enhance existing ones (Dweck, 1999 ; Grant & Dweck, 2003 ). We have chosen to present the 3 × 2 achievement goal model (Elliot et al., 2011 ) with task-based goals oriented to the standard of task accomplishment and with a clear focus on the outcome (cf. Senko & Tropiano, 2016 ). Also belonging to mastery goals are the newly added self-based goals (Elliot et al., 2011 ). In self-based goals, the focus is on being better or avoiding being worse than in the past or as it corresponds to one’s own potential. For this purpose, the agent’s view goes back to the abilities and skills of the self (see Fig. 6 ) before the person tries to expand their competencies or avoid the loss of competencies in the action process. Self-based goals use one’s own intraindividual trajectory as the standard for evaluation. Goal setting starts with a look at one’s past, but more important seems to be a look on one’s future potential (Elliot et al., 2015 ). In other-based goals, the course of action is dominated by the anticipated consequences (see Fig. 6 ). The aim of attaining competence is based on an interpersonal standard of being better than others or not being worse than others. This conceptualization of other-based goals coincides with the normative notion of performance goals (Dweck, 1986 ; Senko et al., 2011 ).

Integrating the 3 × 2 achievement goal framework into the basic motivational model

Several meta-analyses have accumulated evidence on the empirical relationships of achievement goals with academic achievement (Baranik et al., 2010 ; Burnette et al., 2013 ; Huang, 2012 ; Hulleman et al., 2010 ; Murayama & Elliot, 2012 ; Richardson et al., 2012 ; Van Yperen et al., 2014 ; Wirthwein et al., 2013 ). The small but significant effects are remarkably consistent across different meta-analyses (for an overview, Scherrer et al., 2020 ). Mastery approach goals correlate between r = .10 (Baranik et al., 2010 ; Huang, 2012 ; Richardson et al., 2012 ) and r = .14 (Burnette et al., 2013 ; Van Yperen et al., 2014 ) with grades and test performance. Mastery avoidance goals show small negative relationships to academic achievement with correlations ranging from r = − .07 (Van Yperen et al., 2014 ) to r = − .12 (Hulleman et al., 2010 ). The correlation coefficients of performance approach goals to academic achievement are consistently positive, ranging from r = .06 (Hulleman et al., 2010 ) to r = .16 (Burnette et al., 2013 ). However, Hulleman et al. ( 2010 ) caveated that normative performance goals ( r = .14) were associated with significantly better performance outcomes than appearance performance goals ( r = − .14). Negative associations were also found between performance avoidance goals and academic achievement with values ranging from r = − .12 (Murayama & Elliot, 2012 ; Wirthwein et al., 2013 ) to r = -.22 (Burnette et al., 2013 ).

Attribution Theory

Attribution theory addresses the issue of how individuals make causal ascriptions about events in the environment (Graham & Taylor, 2016 ). Persons act like intuitive scientists searching for the perceived causes of success and failure (Stiensmeier-Pelster & Heckhausen, 2018 ). In the attribution process, the person tries to determine the cause of an outcome. Causal inferences are drawn based on the covariation of an observed effect with its possible causes (Kelley, 1973 ). The attributional process starts when the outcome of an event is considered important, unexpected, or negative (Graham, 2020 ), which is often accompanied by happiness in case of success or sadness and frustration in case of failure (Weiner, 1986 ).

The causes are then located in a three-dimensional space. The first fundamental dimension of the attribution theory is called the locus of causality (deCharms, 1968 ; Rotter, 1966 ; Weiner, 1986 ). It can be traced back to the pioneering ideas of Heider ( 1958 ), who found that people identify either the situation or dispositional characteristics of the person as the main reasons for people’s behavior. Individuals differentiate between external causes such as task characteristics or luck and internal causes such as ability or effort. The second causal dimension of attribution theory is entitled stability over time. Weiner ( 1971 ) distinguished between stable causes of outcomes such as ability or task characteristics and unstable causes such as effort or luck. Complete crossing of the locus and stability dimensions yielded a 2 × 2 classification scheme for the perceived causes of achievement outcomes. An outcome can be attributed either internally to the person or externally to circumstances. Furthermore, the cause of the outcome can be perceived as stable or variable over time. Finally, Weiner ( 1979 ) introduced a third causal dimension, controllability, as there was still considerable variability within the cells of the suggested classification scheme. For example, mood and effort are both internal and unstable causes, but effort is more subject to volitional control than mood. By combining two levels of locus with two levels of stability and two levels of control, Weiner ( 1979 ) extended the classification scheme to its current state of eight separable causes of success and failure.

The action model in Fig. 7 depicts the basic idea of attribution theory as stated by Heider ( 1958 ) and Weiner ( 1986 ). Attributions occur at the end of an action process. These causal ascriptions are elicited when the outcome is particularly important, unexpected, or negative (Weiner, 1985 ). Depending on the outcome, the person responds with positive affect in case of success or negative affect in case of failure. This front part of Fig. 7 coincides with current illustrations of the attributional theory of motivation (cf. Graham, 2020 ). Representing causal ascriptions and classifying reasons for success or failure on causal dimensions can only be done in a simplified manner in the basic motivational model. The action outcome is further attributed to dispositions of the self, such as perceived ability or effort, or the characteristics of the situation, such as task difficulty or chance (Stiensmeier-Pelster & Heckhausen, 2018 ). After ascribing the outcome to different causal dimensions, other emotions and future achievement strivings emerge as psychological and behavioral consequences of the attribution process (Weiner, 1986 ).

Integrating attribution theory into the basic motivational model

The three causal dimensions are linked to particular psychological and academic outcomes (Graham, 2020 ). Using meta-analytic structural equation modeling, Brun et al. ( 2021 ) found direct relationships between controllability and performance as well as mediated relationships of locus of causality, perceived competence, and performance. While the latter was most evident in the case of success, in the case of failure, the mediated relationship between the stability dimension, expectancy of success, and performance turned out to be significant. Further meta-analytic research showed that school children attribute success more to internal causes and failure more to external causes (Whitley Jr. & Frieze, 1985 ). This egotistic bias manifests in relating success to ability ( g = .56) and effort ( g = .29), and failure to task difficulty ( g = .45) but not to luck ( g = − .03). Fittingly, Fong et al. ( 2017 ) reported that greater internality and controllability of causal ascriptions are associated with better academic achievement among college students ( r = .14). In addition, Gordeeva et al. ( 2020 ) found that an optimistic attribution style, in which positive events are attributed to stable, internal, and global causes, is weakly related to academic performance ( r = .11). In contrast, a meta-analysis by Richardson et al. ( 2012 ) with university students did not reveal any relationships between academic performance and a pessimistic attribution style ( r =. 01).

The integrative model presented in this paper aims to provide a better overview of the most prominent motivation theories in education. The basic motivational model relies on the general model of motivation by Heckhausen and Heckhausen ( 2018 ) in its sequence of events and adopts considerations from Locke ( 1997 ) and Hattie et al. ( 2020 ) on the integration of motivation theories. The basic model allows for the classification of central motivation constructs into the course of action, highlighting in particular the differences between and within the six most popular motivation theories of our time. It makes us aware of the fact that the major theories cannot be easily merged into one another. Expectancy-value theory, social cognitive theory, self-determination theory, interest theory, achievement goal theory, and attribution theory have all shaped our understanding of why, when, and how individuals learn (Anderman, 2020 ). In the basic motivational model, learning outcomes represent a typical indicator of goal-directed behavior. Associated recent meta-analyses demonstrate the empirical relationship between the motivational constructs of the six central theories and academic achievement. They provide evidence for the explanatory value of each theory for students’ learning.

Particular features of the basic motivational model include parsimony (Hattie et al., 2020 ) and the role of situation, self, and goal as cornerstones of a modern conception for building motivation theories (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ; Graham, 2020 ; Liem & Senko, 2022 ; Ryan & Deci, 2020 ; Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2021 ; Urdan & Kaplan, 2020 ). Occam’s razor ensures to give preference to a model with fewer parameters over a more complex one. A theory with few variables in a clear, logical relationship to each other can be easily tested and can lead more quickly to unambiguous findings than a more expansive one. A basic motivational model should therefore be deliberately kept simple and specify only the decisive factors. This is what we have been trying to achieve. A closer look at current research on motivation in education shows that often only a particular set of constructs from much broader psychological theories is empirically investigated: self-efficacy expectations from social cognitive theory (Schunk & diBenedetto, 2020 ), expectancy and value beliefs from situated expectancy-value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ), or causal ascriptions from attribution theory (Graham, 2020 ). Therefore, for reasons of parsimony, it seems advisable not to try to represent the entire wealth of motivation theories in an integrative model, but only their most important constructs (cf. Anderman, 2020 ; Hattie et al., 2020 ).

While achievement motivation theory posits an interplay of incentives of the situation and motives of the person as the basis for all motivated behavior (Atkinson, 1957 ), social-cognitive and sociocultural theories have significantly altered views on motivation (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020 ; Graham & Weiner, 1996 ; Liem & Elliot, 2018 ; Roeser & Peck, 2009 ; Wigfield et al., 2015 ). We attempted to account for these changing views in our basic motivational model. First, rather than viewing the situation as limited to its potential incentives, we recognized the social, cultural, historical, and environmental context represented in the situation as having a significant impact on the opportunities for motivated action (Nolen, 2020 ). Second, by differentiating the person into self and goal, we could more accurately describe the process of motivated behavior. We mapped the person’s needs, motives, and wishes to the self-system (Roeser & Peck, 2009 ). Driven by its needs, motives, aspirations, and desires, the “I-self”, the consciously experiencing subject, takes influence on the selection of goals and decision-making (Dweck et al., 2003 ; Sui & Humphreys, 2015 ). The self offers the underlying reason for behavior, whereas the goal contains the concrete aim to guide behavior (cf. Elliot et al., 2011 ; Sommet & Elliot, 2017 ).

Affective factors can be active in all phases of the motivation process and take influence on the course of action. At the beginning of the action process, there is typically an awareness of contextual cues or situational stimuli that can trigger emotions such as situational interest, curiosity, or surprise (Gendolla, 1997 ; Hidi & Renninger, 2019 ). Anchored in the self are emotional dispositions of the person such as hope for success, fear of failure, or individual interest. These activating emotions, aroused by situational incentives, are energizers of the action process (Atkinson, 1957 ; Pekrun et al., 2023 ; Renninger & Bachrach, 2015 ). Having goals and being oriented toward them, is also accompanied by emotional states (Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2002 ). Mastery approach goals are typically associated with the presence of positive emotions and performance avoidance goals with the presence of negative emotions, whereas performance approach goals show weak relations to both positive and negative emotions (Huang, 2011 ; Korn et al., 2019 ). Research within the frame of the 3 × 2 achievement goal model could confirm these findings (Lüftenegger et al., 2016 ; Thomas, 2022 ). Positive emotions such as enjoyment and the state of interest (Hidi & Baird, 1986 ; Krapp et al., 1992 ) or negative emotions such as boredom and anger are expressed in accomplishing the action (Pekrun et al., 2023 ). Other emotions are attached to the outcome of the action: Positive outcomes are related to feelings of happiness, and negative outcomes go along with feelings of frustration and sadness (Graham, 2020 ). As consequences of the action, emotions such as pride, relief, or gratitude are prevalent in the case of success, whereas emotions such as guilt, shame, or disappointment emerge in the case of failure (Pekrun et al., 2023 ; Weiner, 1986 ). Overall, each phase of the action process is accompanied by certain affective states, which makes us aware of the close relationship between motivation and emotion.

While we have limited ourselves in this contribution to the six most common theoretical approaches (cf. Linnenbrink-Garcia & Patall, 2016 ), there are considerations of how other theories of motivation in education fit into the basic motivational model. These theories have not been researched by the same amount of scientists as the theories presented. Nevertheless, constructs such as grit, flow, and social motivation also offer suitable explanations for understanding the reasons behind human action. Grit theory (Duckworth et al., 2007 ) holds two trait-like constructs responsible for high motivation during task engagement. Meta-analytic results show that grit ( r = .19) is a consistent predictor of academic achievement with its dimension perseverance of effort ( r = .21) being more strongly related to academic achievement than the dimension consistency of interest ( r = .08; Lam & Zhou, 2022 ). In the integrative model, these two personality traits would be associated with the self and constantly impact goal pursuit (Duckworth et al., 2007 ). Flow theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990 , 2000 ) focuses on experiencing an optimal state of simultaneous absorption, concentration, and enjoyment (Tse et al., 2022 ). As a form of intrinsic motivation (Rheinberg, 2020 ), flow experience would be assigned to the action of the integrative model. Social goals (Wentzel et al., 2018 ) are not located on an intrapersonal level but on an interpersonal level. Two basic motivational models arranged in parallel could be used to map, for example, motivation in teacher-student relationships (Wentzel, 2016 ). This would provide a simple way to represent the reciprocal interactions between the goals and actions of teachers and students.

The integrative model also facilitates an understanding of the interrelationships between different motivational constructs. Howard et al. ( 2021 ) examined in a meta-analysis the relations of different types of motivation from self-determination theory with achievement goals and self-efficacy. Intrinsic and identified motivation showed high correlations with mastery-approach goals, moderate correlations with self-efficacy, and low correlations with performance-approach goals. In contrast, introjected and external motivation showed a reserve pattern and lowly correlated with mastery-approach goals and self-efficacy but moderately with performance-approach goals. To explain these correlative patterns, it can be deduced from the integrative motivation model that intrinsic motivation, identified motivation, mastery-approach goals, and self-efficacy share a common focus on action. In contrast, introjected motivation, extrinsic motivation, and performance-approach goals share a common focus on the consequences of the action. While such post-hoc explanations are of modest scientific value, it may be possible in the future to derive and empirically test predictions about the relationships among motivational constructs based on the integrative model.

A future application of the integrative model is to combine it with neuroscientific research on motivation (Kim, 2013 ; Kim et al., 2017 ). Kim ( 2013 ) proposed a tentative neuroscientific model of motivation processes, in which—similar to the action model—motivation is viewed as a series of dynamic processes. An added value of neuroscientific research is that it can help determine if seemingly overlapping constructs from different theories are unique or similar by examining the patterns of neural activity that are triggered (Kim, 2013 ; Kim et al., 2017 ). It additionally allows for the investigation of unconscious aspects of motivation. Neuroscientific studies can further help identify the mechanism of motivational processes relating to the generation, maintenance, and regulation of motivation. The integrative model can help in identifying overlapping constructs and investigating the mechanisms of motivational processes.

Another application of the integrative model is in using a person-oriented approach to study motivation (Linnenbrink-Garcia & Wormington, 2019 ; Ratelle et al., 2007 ; Wormington & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2017 ). The person-oriented approach takes advantage of the fact that many motivational variables are often highly correlated with each other. Therefore, rather than singling out one motivational variable and analyzing its influences, it seems useful to create groups or profiles of students based on several different motivational variables. Thereby, it is recommended to use an integrative framework to relate the different motivational constructs: “A person-oriented approach can be particularly useful with an integrative theoretical perspective because it allows researchers to model the relations among motivation constructs across theoretical frameworks that may be conceptually related to one another” (Linnenbrink-Garcia & Wormington, 2019 , p. 748).

In the context of the integrative model, we have presented meta-analytic results on the relationship between motivation and academic achievement. Small to medium correlations emerged for the different types of motivation with students’ learning outcomes. Through its sequence of action stages, the integrative model suggests a causal order in which motivation is crucial for achieving academic outcomes. However, findings on the expectancy component show that the other direction may be considered equally probable, and academic achievement influences learners’ motivation (Pinquart & Ebeling, 2020 ; Sitzmann & Yeo, 2013 ). Therefore, the basic motivational model should also be understood as suggesting that prior academic achievement, cognitively represented in the self, helps shape motivation for new learning tasks.

Theories of motivation in education have increasingly expanded and differentiated over time (Schunk et al., 2014 ). Six major theories of motivation have been established (Linnenbrink-Garcia & Patall, 2016 ), which we have considered against the background of an integrative action model. The framework model is intended to contribute to a deeper understanding of the major theories of academic motivation and to show the focus of each theoretical conception. In this way, difficulties of understanding with which novices try to open up the field of academic motivation theories should be overcome to a certain extent. From the placement of the theories in the basic motivational model, it becomes clear that the various approaches to motivation cannot simply be merged into one another. Nonetheless, opportunities arise from the integrative model to reflect on the meta-analytic findings regarding the interrelations of motivational theories and constructs (Howard et al., 2021 ; Huang, 2016 ) and to speculate about the underlying mechanims of the connection. Similarly, possibilities arise to debate the changing understanding of motivational constructs or to situate new theories and constructs in the course of action to clarify their meaning.

Motivation in education is a very lively field of research with a variety of approaches and ideas to develop further beyond the basic theories. This includes a stronger inclusion of situational, social, and cultural characteristics in the explanatory context (Nolen, 2020 ), the use of findings from neuroscience to objectify assumptions about motivational processes (Hidi et al., 2019 ), the interaction of motivation and emotion in learning and performance (Pekrun & Marsh, 2022 ), the analysis of motivational profiles based on a person-centered approach (Linnenbrink-Garcia & Wormington, 2019 ), or the development of motivation interventions originating in sound theoretical approaches (Lazowski & Hulleman, 2016 ). To ensure that these developments in an increasingly broad field of research do not diverge, it is important to obtain a common understanding of the basic models and conceptions of motivation research. We hope to have made such a contribution by placing key theories and constructs of motivation within an integrative framework model.

Achtziger, A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2018). Motivation and volition in the course of action. In J. Heckhausen & H. Heckhausen (Eds.), Motivation and action (pp. 272–295). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65094-4_12

Chapter Google Scholar

Ainley, M. (2017). Interest: Knowns, unknowns, and basic processes. In P. A. O'Keefe & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), The science of interest (pp. 3–24). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55509-6_1

Ainley, M., & Hidi, S. (2014). Interest and enjoyment. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 205–227). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Google Scholar

Alexander, P. A., Kulikowich, J. M., & Jetton, T. L. (1994). The role of subject-matter knowledge and interest in the processing of linear and nonlinear texts. Review of Educational Research, 64 (2), 201–252. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170694

Article Google Scholar

Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80 (3), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.3.260

Anderman, E. M. (2020). Achievement motivation theory: Balancing precision and utility. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61 , 101864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101864

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64 , 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043445

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84 (2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory . Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Bandura, A. (1988). Self-regulation of motivation and action through goal systems. In V. Hamilton, G. H. Bower, & N. H. Frijda (Eds.), Cognitive perspectives on emotion and motivation (pp. 37–61). Springer . https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-2792-6_2

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44 (9), 1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co..

Baranik, L. E., Stanley, L. J., Bynum, B. H., & Lance, C. E. (2010). Examining the construct validity of mastery-avoidance achievement goals: A meta-analysis. Human Performance, 23 (3), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2010.488463

Bargh, J. A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2023). The unconscious sources of motivation and goals. In M. Bong, J. Reeve, & S. Kim (Eds.), Motivation science (pp. 175–182). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197662359.003.0030

Barroso, C., Ganley, C. M., McGraw, A. L., Geer, E. A., Hart, S. A., & Daucourt, M. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of the relation between math anxiety and math achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 147 (2), 134–168. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000307

Baumeister, R. F. (2010). The self. In R. F. Baumeister & E. J. Finkel (Eds.), Advanced social psychology: The state of the science (pp. 139–175). Oxford University Press.

Beckmann, J., & Heckhausen, H. (2018). Situational determinants of behavior. In J. Heckhausen & H. Heckhausen (Eds.), Motivation and action (pp. 113–162). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65094-4_4

Berlyne, D. E. (1960). Conflict, arousal, and curiosity . McGraw-Hill Book Company. https://doi.org/10.1037/11164-000

Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2003). Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educational Psychology Review, 15 (1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021302408382