Review articles: purpose, process, and structure

- Published: 02 October 2017

- Volume 46 , pages 1–5, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Robert W. Palmatier 1 ,

- Mark B. Houston 2 &

- John Hulland 3

241k Accesses

487 Citations

64 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many research disciplines feature high-impact journals that are dedicated outlets for review papers (or review–conceptual combinations) (e.g., Academy of Management Review , Psychology Bulletin , Medicinal Research Reviews ). The rationale for such outlets is the premise that research integration and synthesis provides an important, and possibly even a required, step in the scientific process. Review papers tend to include both quantitative (i.e., meta-analytic, systematic reviews) and narrative or more qualitative components; together, they provide platforms for new conceptual frameworks, reveal inconsistencies in the extant body of research, synthesize diverse results, and generally give other scholars a “state-of-the-art” snapshot of a domain, often written by topic experts (Bem 1995 ). Many premier marketing journals publish meta-analytic review papers too, though authors often must overcome reviewers’ concerns that their contributions are limited due to the absence of “new data.” Furthermore, relatively few non-meta-analysis review papers appear in marketing journals, probably due to researchers’ perceptions that such papers have limited publication opportunities or their beliefs that the field lacks a research tradition or “respect” for such papers. In many cases, an editor must provide strong support to help such review papers navigate the review process. Yet, once published, such papers tend to be widely cited, suggesting that members of the field find them useful (see Bettencourt and Houston 2001 ).

In this editorial, we seek to address three topics relevant to review papers. First, we outline a case for their importance to the scientific process, by describing the purpose of review papers . Second, we detail the review paper editorial initiative conducted over the past two years by the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science ( JAMS ), focused on increasing the prevalence of review papers. Third, we describe a process and structure for systematic ( i.e. , non-meta-analytic) review papers , referring to Grewal et al. ( 2018 ) insights into parallel meta-analytic (effects estimation) review papers. (For some strong recent examples of marketing-related meta-analyses, see Knoll and Matthes 2017 ; Verma et al. 2016 ).

Purpose of review papers

In their most general form, review papers “are critical evaluations of material that has already been published,” some that include quantitative effects estimation (i.e., meta-analyses) and some that do not (i.e., systematic reviews) (Bem 1995 , p. 172). They carefully identify and synthesize relevant literature to evaluate a specific research question, substantive domain, theoretical approach, or methodology and thereby provide readers with a state-of-the-art understanding of the research topic. Many of these benefits are highlighted in Hanssens’ ( 2018 ) paper titled “The Value of Empirical Generalizations in Marketing,” published in this same issue of JAMS.

The purpose of and contributions associated with review papers can vary depending on their specific type and research question, but in general, they aim to

Resolve definitional ambiguities and outline the scope of the topic.

Provide an integrated, synthesized overview of the current state of knowledge.

Identify inconsistencies in prior results and potential explanations (e.g., moderators, mediators, measures, approaches).

Evaluate existing methodological approaches and unique insights.

Develop conceptual frameworks to reconcile and extend past research.

Describe research insights, existing gaps, and future research directions.

Not every review paper can offer all of these benefits, but this list represents their key contributions. To provide a sufficient contribution, a review paper needs to achieve three key standards. First, the research domain needs to be well suited for a review paper, such that a sufficient body of past research exists to make the integration and synthesis valuable—especially if extant research reveals theoretical inconsistences or heterogeneity in its effects. Second, the review paper must be well executed, with an appropriate literature collection and analysis techniques, sufficient breadth and depth of literature coverage, and a compelling writing style. Third, the manuscript must offer significant new insights based on its systematic comparison of multiple studies, rather than simply a “book report” that describes past research. This third, most critical standard is often the most difficult, especially for authors who have not “lived” with the research domain for many years, because achieving it requires drawing some non-obvious connections and insights from multiple studies and their many different aspects (e.g., context, method, measures). Typically, after the “review” portion of the paper has been completed, the authors must spend many more months identifying the connections to uncover incremental insights, each of which takes time to detail and explicate.

The increasing methodological rigor and technical sophistication of many marketing studies also means that they often focus on smaller problems with fewer constructs. By synthesizing these piecemeal findings, reconciling conflicting evidence, and drawing a “big picture,” meta-analyses and systematic review papers become indispensable to our comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon, among both academic and practitioner communities. Thus, good review papers provide a solid platform for future research, in the reviewed domain but also in other areas, in that researchers can use a good review paper to learn about and extend key insights to new areas.

This domain extension, outside of the core area being reviewed, is one of the key benefits of review papers that often gets overlooked. Yet it also is becoming ever more important with the expanding breadth of marketing (e.g., econometric modeling, finance, strategic management, applied psychology, sociology) and the increasing velocity in the accumulation of marketing knowledge (e.g., digital marketing, social media, big data). Against this backdrop, systematic review papers and meta-analyses help academics and interested managers keep track of research findings that fall outside their main area of specialization.

JAMS’ review paper editorial initiative

With a strong belief in the importance of review papers, the editorial team of JAMS has purposely sought out leading scholars to provide substantive review papers, both meta-analysis and systematic, for publication in JAMS . Many of the scholars approached have voiced concerns about the risk of such endeavors, due to the lack of alternative outlets for these types of papers. Therefore, we have instituted a unique process, in which the authors develop a detailed outline of their paper, key tables and figures, and a description of their literature review process. On the basis of this outline, we grant assurances that the contribution hurdle will not be an issue for publication in JAMS , as long as the authors execute the proposed outline as written. Each paper still goes through the normal review process and must meet all publication quality standards, of course. In many cases, an Area Editor takes an active role to help ensure that each paper provides sufficient insights, as required for a high-quality review paper. This process gives the author team confidence to invest effort in the process. An analysis of the marketing journals in the Financial Times (FT 50) journal list for the past five years (2012–2016) shows that JAMS has become the most common outlet for these papers, publishing 31% of all review papers that appeared in the top six marketing journals.

As a next step in positioning JAMS as a receptive marketing outlet for review papers, we are conducting a Thought Leaders Conference on Generalizations in Marketing: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses , with a corresponding special issue (see www.springer.com/jams ). We will continue our process of seeking out review papers as an editorial strategy in areas that could be advanced by the integration and synthesis of extant research. We expect that, ultimately, such efforts will become unnecessary, as authors initiate review papers on topics of their own choosing to submit them to JAMS . In the past two years, JAMS already has increased the number of papers it publishes annually, from just over 40 to around 60 papers per year; this growth has provided “space” for 8–10 review papers per year, reflecting our editorial target.

Consistent with JAMS ’ overall focus on managerially relevant and strategy-focused topics, all review papers should reflect this emphasis. For example, the domains, theories, and methods reviewed need to have some application to past or emerging managerial research. A good rule of thumb is that the substantive domain, theory, or method should attract the attention of readers of JAMS .

The efforts of multiple editors and Area Editors in turn have generated a body of review papers that can serve as useful examples of the different types and approaches that JAMS has published.

Domain-based review papers

Domain-based review papers review, synthetize, and extend a body of literature in the same substantive domain. For example, in “The Role of Privacy in Marketing” (Martin and Murphy 2017 ), the authors identify and define various privacy-related constructs that have appeared in recent literature. Then they examine the different theoretical perspectives brought to bear on privacy topics related to consumers and organizations, including ethical and legal perspectives. These foundations lead in to their systematic review of privacy-related articles over a clearly defined date range, from which they extract key insights from each study. This exercise of synthesizing diverse perspectives allows these authors to describe state-of-the-art knowledge regarding privacy in marketing and identify useful paths for research. Similarly, a new paper by Cleeren et al. ( 2017 ), “Marketing Research on Product-Harm Crises: A Review, Managerial Implications, and an Agenda for Future Research,” provides a rich systematic review, synthesizes extant research, and points the way forward for scholars who are interested in issues related to defective or dangerous market offerings.

Theory-based review papers

Theory-based review papers review, synthetize, and extend a body of literature that uses the same underlying theory. For example, Rindfleisch and Heide’s ( 1997 ) classic review of research in marketing using transaction cost economics has been cited more than 2200 times, with a significant impact on applications of the theory to the discipline in the past 20 years. A recent paper in JAMS with similar intent, which could serve as a helpful model, focuses on “Resource-Based Theory in Marketing” (Kozlenkova et al. 2014 ). The article dives deeply into a description of the theory and its underlying assumptions, then organizes a systematic review of relevant literature according to various perspectives through which the theory has been applied in marketing. The authors conclude by identifying topical domains in marketing that might benefit from additional applications of the theory (e.g., marketing exchange), as well as related theories that could be integrated meaningfully with insights from the resource-based theory.

Method-based review papers

Method-based review papers review, synthetize, and extend a body of literature that uses the same underlying method. For example, in “Event Study Methodology in the Marketing Literature: An Overview” (Sorescu et al. 2017 ), the authors identify published studies in marketing that use an event study methodology. After a brief review of the theoretical foundations of event studies, they describe in detail the key design considerations associated with this method. The article then provides a roadmap for conducting event studies and compares this approach with a stock market returns analysis. The authors finish with a summary of the strengths and weaknesses of the event study method, which in turn suggests three main areas for further research. Similarly, “Discriminant Validity Testing in Marketing: An Analysis, Causes for Concern, and Proposed Remedies” (Voorhies et al. 2016 ) systematically reviews existing approaches for assessing discriminant validity in marketing contexts, then uses Monte Carlo simulation to determine which tests are most effective.

Our long-term editorial strategy is to make sure JAMS becomes and remains a well-recognized outlet for both meta-analysis and systematic managerial review papers in marketing. Ideally, review papers would come to represent 10%–20% of the papers published by the journal.

Process and structure for review papers

In this section, we review the process and typical structure of a systematic review paper, which lacks any long or established tradition in marketing research. The article by Grewal et al. ( 2018 ) provides a summary of effects-focused review papers (i.e., meta-analyses), so we do not discuss them in detail here.

Systematic literature review process

Some review papers submitted to journals take a “narrative” approach. They discuss current knowledge about a research domain, yet they often are flawed, in that they lack criteria for article inclusion (or, more accurately, article exclusion), fail to discuss the methodology used to evaluate included articles, and avoid critical assessment of the field (Barczak 2017 ). Such reviews tend to be purely descriptive, with little lasting impact.

In contrast, a systematic literature review aims to “comprehensively locate and synthesize research that bears on a particular question, using organized, transparent, and replicable procedures at each step in the process” (Littell et al. 2008 , p. 1). Littell et al. describe six key steps in the systematic review process. The extent to which each step is emphasized varies by paper, but all are important components of the review.

Topic formulation . The author sets out clear objectives for the review and articulates the specific research questions or hypotheses that will be investigated.

Study design . The author specifies relevant problems, populations, constructs, and settings of interest. The aim is to define explicit criteria that can be used to assess whether any particular study should be included in or excluded from the review. Furthermore, it is important to develop a protocol in advance that describes the procedures and methods to be used to evaluate published work.

Sampling . The aim in this third step is to identify all potentially relevant studies, including both published and unpublished research. To this end, the author must first define the sampling unit to be used in the review (e.g., individual, strategic business unit) and then develop an appropriate sampling plan.

Data collection . By retrieving the potentially relevant studies identified in the third step, the author can determine whether each study meets the eligibility requirements set out in the second step. For studies deemed acceptable, the data are extracted from each study and entered into standardized templates. These templates should be based on the protocols established in step 2.

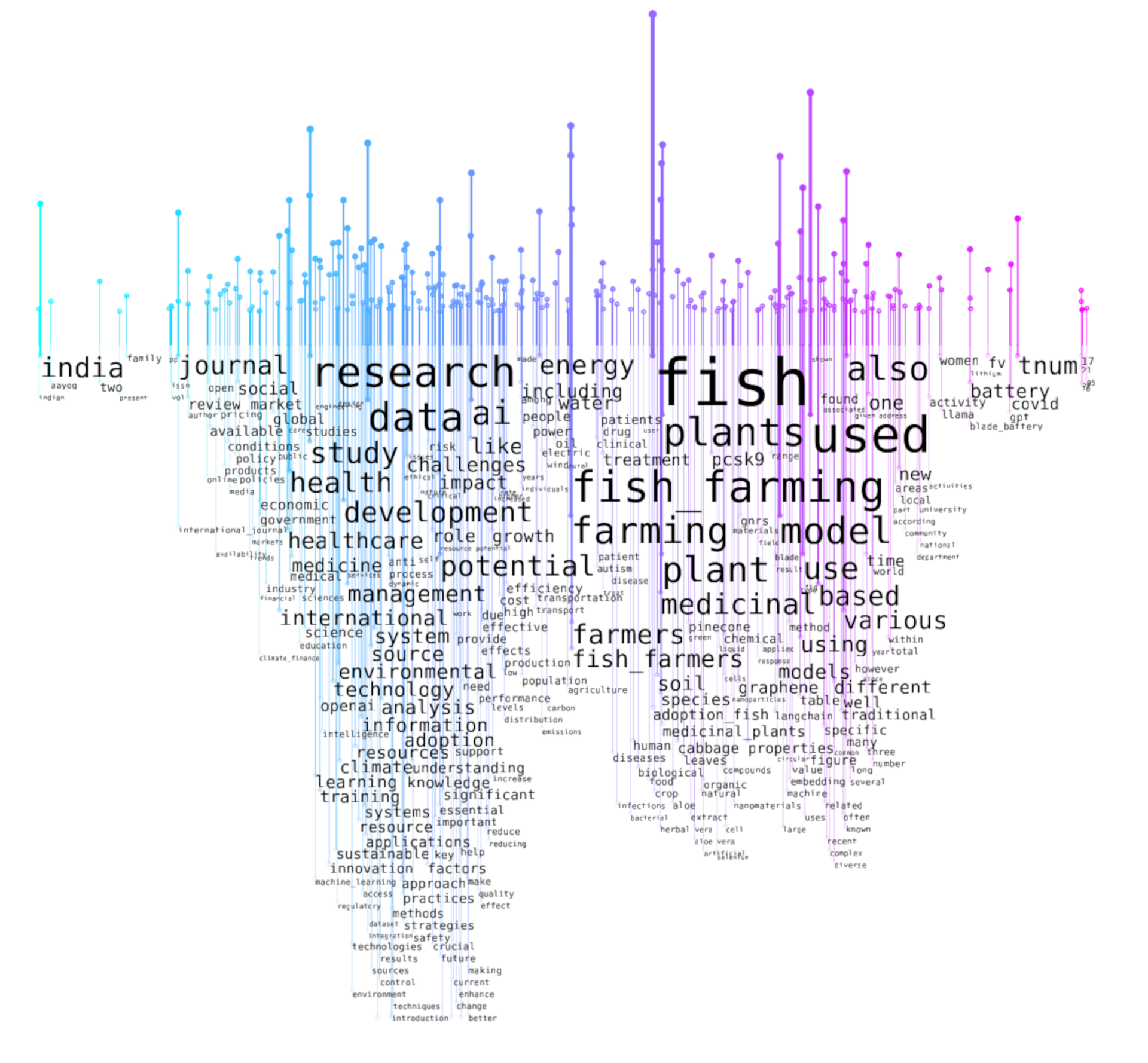

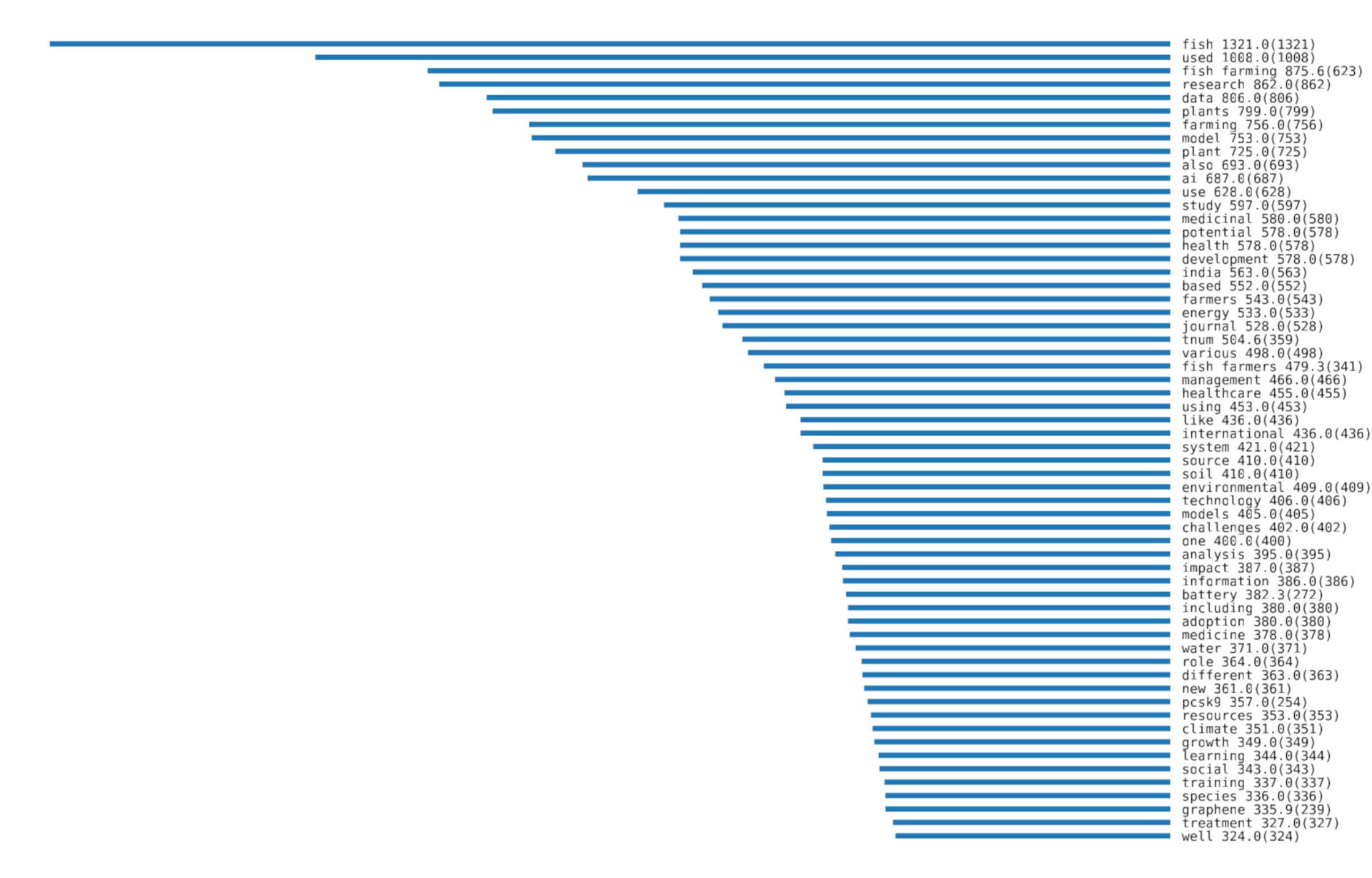

Data analysis . The degree and nature of the analyses used to describe and examine the collected data vary widely by review. Purely descriptive analysis is useful as a starting point but rarely is sufficient on its own. The examination of trends, clusters of ideas, and multivariate relationships among constructs helps flesh out a deeper understanding of the domain. For example, both Hult ( 2015 ) and Huber et al. ( 2014 ) use bibliometric approaches (e.g., examine citation data using multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis techniques) to identify emerging versus declining themes in the broad field of marketing.

Reporting . Three key aspects of this final step are common across systematic reviews. First, the results from the fifth step need to be presented, clearly and compellingly, using narratives, tables, and figures. Second, core results that emerge from the review must be interpreted and discussed by the author. These revelatory insights should reflect a deeper understanding of the topic being investigated, not simply a regurgitation of well-established knowledge. Third, the author needs to describe the implications of these unique insights for both future research and managerial practice.

A new paper by Watson et al. ( 2017 ), “Harnessing Difference: A Capability-Based Framework for Stakeholder Engagement in Environmental Innovation,” provides a good example of a systematic review, starting with a cohesive conceptual framework that helps establish the boundaries of the review while also identifying core constructs and their relationships. The article then explicitly describes the procedures used to search for potentially relevant papers and clearly sets out criteria for study inclusion or exclusion. Next, a detailed discussion of core elements in the framework weaves published research findings into the exposition. The paper ends with a presentation of key implications and suggestions for the next steps. Similarly, “Marketing Survey Research Best Practices: Evidence and Recommendations from a Review of JAMS Articles” (Hulland et al. 2017 ) systematically reviews published marketing studies that use survey techniques, describes recent trends, and suggests best practices. In their review, Hulland et al. examine the entire population of survey papers published in JAMS over a ten-year span, relying on an extensive standardized data template to facilitate their subsequent data analysis.

Structure of systematic review papers

There is no cookie-cutter recipe for the exact structure of a useful systematic review paper; the final structure depends on the authors’ insights and intended points of emphasis. However, several key components are likely integral to a paper’s ability to contribute.

Depth and rigor

Systematic review papers must avoid falling in to two potential “ditches.” The first ditch threatens when the paper fails to demonstrate that a systematic approach was used for selecting articles for inclusion and capturing their insights. If a reader gets the impression that the author has cherry-picked only articles that fit some preset notion or failed to be thorough enough, without including articles that make significant contributions to the field, the paper will be consigned to the proverbial side of the road when it comes to the discipline’s attention.

Authors that fall into the other ditch present a thorough, complete overview that offers only a mind-numbing recitation, without evident organization, synthesis, or critical evaluation. Although comprehensive, such a paper is more of an index than a useful review. The reviewed articles must be grouped in a meaningful way to guide the reader toward a better understanding of the focal phenomenon and provide a foundation for insights about future research directions. Some scholars organize research by scholarly perspectives (e.g., the psychology of privacy, the economics of privacy; Martin and Murphy 2017 ); others classify the chosen articles by objective research aspects (e.g., empirical setting, research design, conceptual frameworks; Cleeren et al. 2017 ). The method of organization chosen must allow the author to capture the complexity of the underlying phenomenon (e.g., including temporal or evolutionary aspects, if relevant).

Replicability

Processes for the identification and inclusion of research articles should be described in sufficient detail, such that an interested reader could replicate the procedure. The procedures used to analyze chosen articles and extract their empirical findings and/or key takeaways should be described with similar specificity and detail.

We already have noted the potential usefulness of well-done review papers. Some scholars always are new to the field or domain in question, so review papers also need to help them gain foundational knowledge. Key constructs, definitions, assumptions, and theories should be laid out clearly (for which purpose summary tables are extremely helpful). An integrated conceptual model can be useful to organize cited works. Most scholars integrate the knowledge they gain from reading the review paper into their plans for future research, so it is also critical that review papers clearly lay out implications (and specific directions) for research. Ideally, readers will come away from a review article filled with enthusiasm about ways they might contribute to the ongoing development of the field.

Helpful format

Because such a large body of research is being synthesized in most review papers, simply reading through the list of included studies can be exhausting for readers. We cannot overstate the importance of tables and figures in review papers, used in conjunction with meaningful headings and subheadings. Vast literature review tables often are essential, but they must be organized in a way that makes their insights digestible to the reader; in some cases, a sequence of more focused tables may be better than a single, comprehensive table.

In summary, articles that review extant research in a domain (topic, theory, or method) can be incredibly useful to the scientific progress of our field. Whether integrating the insights from extant research through a meta-analysis or synthesizing them through a systematic assessment, the promised benefits are similar. Both formats provide readers with a useful overview of knowledge about the focal phenomenon, as well as insights on key dilemmas and conflicting findings that suggest future research directions. Thus, the editorial team at JAMS encourages scholars to continue to invest the time and effort to construct thoughtful review papers.

Barczak, G. (2017). From the editor: writing a review article. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 34 (2), 120–121.

Article Google Scholar

Bem, D. J. (1995). Writing a review article for psychological bulletin. Psychological Bulletin, 118 (2), 172–177.

Bettencourt, L. A., & Houston, M. B. (2001). Assessing the impact of article method type and subject area on citation frequency and reference diversity. Marketing Letters, 12 (4), 327–340.

Cleeren, K., Dekimpe, M. G., & van Heerde, H. J. (2017). Marketing research on product-harm crises: a review, managerial implications. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (5), 593–615.

Grewal, D., Puccinelli, N. M., & Monroe, K. B. (2018). Meta-analysis: error cancels and truth accrues. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1).

Hanssens, D. M. (2018). The value of empirical generalizations in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1).

Huber, J., Kamakura, W., & Mela, C. F. (2014). A topical history of JMR . Journal of Marketing Research, 51 (1), 84–91.

Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H., & Smith, K. M. (2017). Marketing survey research best practices: evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0532-y .

Hult, G. T. M. (2015). JAMS 2010—2015: literature themes and intellectual structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43 (6), 663–669.

Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2017). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: a meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (1), 55–75.

Kozlenkova, I. V., Samaha, S. A., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Resource-based theory in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42 (1), 1–21.

Littell, J. H., Corcoran, J., & Pillai, V. (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis . New York: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Martin, K. D., & Murphy, P. E. (2017). The role of data privacy in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (2), 135–155.

Rindfleisch, A., & Heide, J. B. (1997). Transaction cost analysis: past, present, and future applications. Journal of Marketing, 61 (4), 30–54.

Sorescu, A., Warren, N. L., & Ertekin, L. (2017). Event study methodology in the marketing literature: an overview. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (2), 186–207.

Verma, V., Sharma, D., & Sheth, J. (2016). Does relationship marketing matter in online retailing? A meta-analytic approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (2), 206–217.

Voorhies, C. M., Brady, M. K., Calantone, R., & Ramirez, E. (2016). Discriminant validity testing in marketing: an analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (1), 119–134.

Watson, R., Wilson, H. N., Smart, P., & Macdonald, E. K. (2017). Harnessing difference: a capability-based framework for stakeholder engagement in environmental innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12394 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Foster School of Business, University of Washington, Box: 353226, Seattle, WA, 98195-3226, USA

Robert W. Palmatier

Neeley School of Business, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX, USA

Mark B. Houston

Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA

John Hulland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert W. Palmatier .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Palmatier, R.W., Houston, M.B. & Hulland, J. Review articles: purpose, process, and structure. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 46 , 1–5 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0563-4

Download citation

Published : 02 October 2017

Issue Date : January 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0563-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Search

- CN (Chinese)

- DE (German)

- ES (Spanish)

- FR (Français)

- JP (Japanese)

- Open science

- Booksellers

- Peer Reviewers

- Springer Nature Group ↗

- Springer journals

- Nature Portfolio journals

- Adis journals

- Academic journals on nature.com

- Palgrave Macmillan journals

- Journal archives

- Open access journals

- eBook collections

- Book archives

- Open Access Books

- Proceedings

- Reference Modules

- Databases & Solutions

- AdisInsight

- Data Solutions

- protocols.io

- SpringerMaterials

- SpringerProtocols

- Springer Nature Experiments

- Corporate & Health

- Springer Nature Video

- Research Data Services

- Nature Masterclasses

- Products overview

- Academic, Government & Corporate

- Request a trial

- Request a demo

- Request a quote

- Corporate & Health solutions

- eBook and Journal collections

- Content on Demand (CoD)

- Quote, trial or demo

- Journals catalog

- Serials Update

- Publishing Model Changes

- Cessations & Transfers

- Licensing A-Z

- How it works

- Talk to a Licensing Manager

- Digital preservation

- Licensing overview

- Open Research

- Discovery at Springer Nature

- MARC Records

- Librarian Portal

- Remote Access

- Content Promotion

- Library Promotion

- Tutorials & User Guides

- Webinars & Podcasts

- White papers

- Support your users

- Account Development

- Usage reporting

- Tools & Services overview

- News & Initiatives

- System Updates

- Overview Page

- Stay informed

Nature Reviews

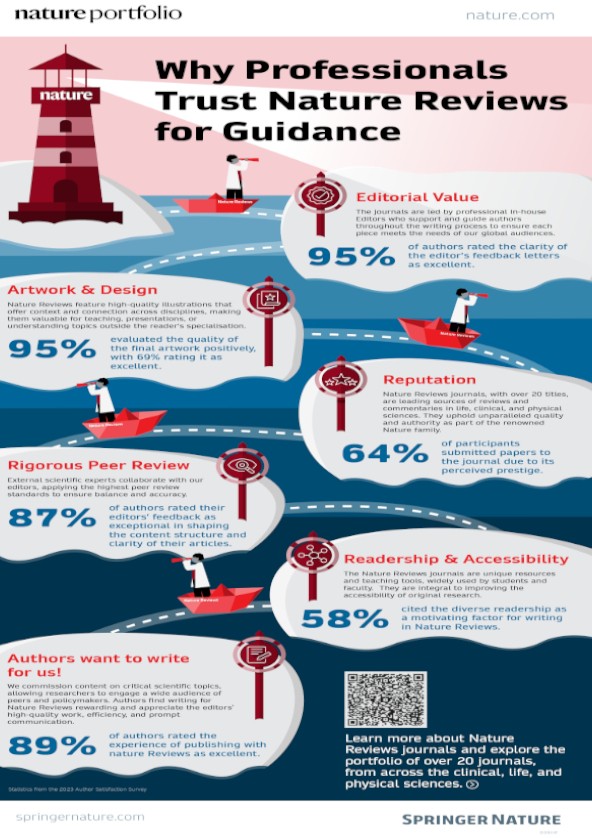

Research in perspective. Reviews, News & Opinion content, often referred to as non-primary content, plays a crucial part in enhancing science education, communication, and collaboration. By offering a diverse range of formats, this content bridges the gap between researchers, students, policymakers, and the broader public. This proprietary content — not available elsewhere — features:

- Review articles summarising the current state of understanding on a topic within a certain discipline.

- Perspectives, opinion, and commentary bringing original points of view to an issue and proposing a solution.

- Community-focused articles exploring community issues, such as career development, representation, sustainability, and more.

- Article summaries short , focused articles about recent scholarship.

- Feature articles giving depth and detail to a topical issue.

Licensing options

Help your users make their own discoveries

Filtering, enhancing & amplifying research

The Nature Reviews journals act as a filter to help busy students, researchers and clinicians keep up to date with the latest scientific literature. This carefully curated content educates and inspires future scientists, supports global collaboration, and addresses the world’s greatest challenges. It is widely read, acting as a catalyst for debate and change bringing about real-world benefits. Specialist Nature Reviews content includes:

- Technical Reviews that provide an outline of the scientific and technical challenges and opportunities in a certain field.

- Consensus Statements that give a comprehensive analysis and recommendations from a group of experts on a scientific or medical issue.

- Primer articles that provide introductions to diseases or disorders, or scientific methods.

Guiding researchers to important primary research beyond their immediate expertise

Why choose Reviews journals?

- Widely used by students and faculty for their educational value.

- Improves accessibility of original research by summarizing latest developments in various fields.

- Editors select leading experts to write on important and timely topics.

- Reviewed by expert peer reviewers.

“Review articles provide an overall picture of the topics that I bring up in lectures, as well as become material for discussion in our student groups.”

- Asst. Professor, Asia

“As research becomes more collaborative, our journals distill the diversity of perspectives to guide readers through the literature, providing researchers with the tools they need to push the boundary of discovery."

- Mina Razzak, Editorial Director, Nature Reviews

What authors have to say

What authors really think about publishing in Nature Reviews

Get an inside look at what authors really think about publishing in Nature Reviews journals. Hear firsthand about their experiences, from working with editors to navigating peer review.

Dive into the world of scientific publishing alongside the authors themselves and read the blog post written by Editorial Director, Mina Razzak.

Download the Infographic

All Reviews journals by subject area

Clinical Medicine | Life Sciences | Physical Sciences | Social Sciences | Multi-disciplinary |

Find the right journals for your users

The complete journal list.

Nature Portfolio includes a wide selection of journals covering clinical, life, physical, social and earth scientists.

Nature – Science journalism at its best

Essential science news, reviews and insights into developments affecting research communities globally.

Stay up to date

Here to foster information exchange with the library community

Springer Nature's LibraryZone is a community developed to foster sharing of information with the library community. Enjoy!

Connect with us on LinkedIn and stay up to date with news and development.

News, information on our forthcoming books, author content and discounts.

- Tools & Services

- Sales and account contacts

- Professional

- Press office

- Locations & Contact

We are a world leading research, educational and professional publisher. Visit our main website for more information.

- © 2024 Springer Nature

- General terms and conditions

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Your Privacy Choices / Manage Cookies

- Accessibility

- Legal notice

- Help us to improve this site, send feedback.

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary

About the journal.

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary (RRIJM) is an international Double-blind peer-reviewed [refereed] open access online journal. Too often a journal’s decision to publish a paper is dominated by what the editor/s think is interesting and will gain greater readership-both of which are subjective judgments and lead to decisions which are frustrating and delay the publication of your work. RRIJM will rigorously peer-review your submissions and publish all papers that are judged to be technically sound. Judgments about the importance of any particular paper are then made after publication by the readership (who are the most qualified to determine what is of interest to them).

Most conventional journals publish papers from tightly defined subject areas, making it more difficult for readers from other disciplines to read them. RRIJM has no such barriers, which helps your research reach the entire scientific community.

- Title: RESEARCH REVIEW International Multidisciplinary Research Journal

- ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online)

- Impact Factor: 6.849

- Crossref DOI: 10.31305/rrijm

- Frequency of Publication: Monthly [12 issues per year]

- Languages: English/Hindi/Gujarat [Multiple Languages]

- Accessibility: Open Access

- Peer Review Process: Double Blind Peer Review Process

- Subject: Multidisciplinary

- Plagiarism Checker: Turnitin (License)

- Publication Format: Online

- Contact No.: +91- 99784 40833

- Email: [email protected]

- Old Website: https://old.rrjournals.com/

- New Website: https://rrjournals.com/

- Address: 15, Kalyan Nagar, Shahpur, Ahmedabad, Gujarat 380001

Key Features of RRIJM

- Journal was listed in UGC with Journal No. 44945 (Till 14-06-2019)

- Journal Publishes online every month

- Online article submission

- Standard peer review process

Current Issue

Industrialization and Economic Prosperity: The Strategic Vision of Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya

The final check: a strategy of patient engagement, are prospective teachers prepared for the new normal- reflections from bihar, india, elementary education among muslims in india: current status and policy implications, the gold market and covid-19: an indian perspective, a comparative analysis of modern and traditional herbal health care systems in the tribal dominated landscapes of pithoragarh district, uttarakhand, study on e-commerce growth and impact on indian economic development, a study on consumer buying behavior towards cosmetics products with respect to social media users, evaluating the impact and awareness of the ayushman bharat scheme in bihar, a comparative study of the adjustment of athlete and non-athlete police officers ખેલાડી અને બિન ખેલાડી પોલીસ ભાઈઓના સમાયોજનનો તુલનાત્મક અભ્યાસ, information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Make a Submission

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Click here to go to Old Website

International Journal of Research and Review

International Journal of Research and Review (IJRR)

Issn: 2349-9788 (online) issn: 2454-2237 (print).

International Journal of Research and Review (E-ISSN: 2349-9788; P-ISSN: 2454-2237)is a double-blind, Indexed peer-reviewed, open access international journal dedicated to promotion of research in multidisciplinary areas. We define Open Access-journals as journals that use a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. From the BOAI definition of "Open Access" users shall have the right to "read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link" to the full texts of articles. The journal publishes original research article from broad areas like Accountancy, Agriculture, Anthropology, Anatomy, Architecture, Arts, Biochemistry, Bioinformatics, Biology, Bioscience, Biostatistics, Biotechnology, Botany, Chemistry, Commerce, Computer Science, Dairy Technology, Dentistry, Ecology, Economics, Education, Engineering, Environmental Science, Food & Nutrition, Forensic Science, Forestry, Geology, Geography, Health Sciences, History, Home Science, Journalism & Mass Communication, Language, Law, Life Science, Literature, Management, Marine Science, Mathematics, Medical Science, Microbiology, Pathology, Paramedical Science, Pharmacy, Philosophy, Physical Education, Physiotherapy, Physics, Political Science, Public Health, Psychology, Science, Social Science, Sociology, Sports Medicine, Statistics, Tourism, Veterinary Science & Animal Husbandry, Yoga, Zoology etc.

The International Journal of Research and Review (IJRR) provides rapid publication of articles in all areas of research.

Frequency: Monthly Language: English

Scope of Journal

International Journal of Research and Review (IJRR) is a double-blind Indexed peer-reviewed open access journal which publishes original articles, reviews and short communications that are not under consideration for publication elsewhere. The journal publishes papers based on original research that are judged by critical reviews, to make a substantial contribution in the field. It aims at rapid publication of high quality research results while maintaining rigorous review process. The Journal welcomes the submission of manuscripts that meet the general criteria of significance and academic excellence. Papers are published approximately one month after acceptance.

IJRR is dedicated to promote high quality research work in multidisciplinary field.

Index Copernicus Value (ICV) for 2022: 100.00; ICV 2021: 100.00; ICV 2020: 100.00; ICV 2019: 96.58; ICV 2018: 95.79; ICV 2017: 85.08; ICV 2016: 67.22; ICV 2015: 73.64; ICV 2014: 52.85

Salient features of our journal.

✵ Journal is indexed with Index Copernicus and other indexing agencies.

✵ Print version (hard copy) with P-ISSN number is available.

✵ Fast Publication Process.

✵ Free e-Certificate of Publication on author's request.

How to Submit Manuscript:

Thesis publication, research articles.

Nitin V Vichare, Rakesh Maggon

Smita Deshkar, Niranjan Patil, Pranali Balmiki

Ashish Choudhary, Riyaz Farooq, Aamir Rashid Purra, Fayaz Ahmed Ahangar

Joshi Medhavi H., Desai Devangi S, Singh Lalli M, Joshi Vaibhavi A

Jasvir Singh

Mariya Thomas Chacko, Tima Babu, Jenin Vincent Parambi, Irene T. Ivan, Sheik Haja Sherief

Click Here to Read more...

Anwar Sholeh, Alwi Thamrin Nasution, Radar Radius Tarigan

Arnaldi Fernando, Dairion Gatot, Yan Indra Fajar Sitepu

Iji Clement O, Age Terungwa James

Varsha S. Dhage, Pratibha Chougule

Uzma Khan, Arindam Ghosh

Dr. Uzma Khan, Dr. Arindam Ghosh, Dr. John Pramod

Our Journals

Visit Website

International Journal of Science and Healthcare Research

Galore International Journal of Health Sciences and Research

Galore International Journal of Applied Sciences and Humanities

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Writing a good review article

- 3 minute read

- 95.9K views

Table of Contents

As a young researcher, you might wonder how to start writing your first review article, and the extent of the information that it should contain. A review article is a comprehensive summary of the current understanding of a specific research topic and is based on previously published research. Unlike research papers, it does not contain new results, but can propose new inferences based on the combined findings of previous research.

Types of review articles

Review articles are typically of three types: literature reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

A literature review is a general survey of the research topic and aims to provide a reliable and unbiased account of the current understanding of the topic.

A systematic review , in contrast, is more specific and attempts to address a highly focused research question. Its presentation is more detailed, with information on the search strategy used, the eligibility criteria for inclusion of studies, the methods utilized to review the collected information, and more.

A meta-analysis is similar to a systematic review in that both are systematically conducted with a properly defined research question. However, unlike the latter, a meta-analysis compares and evaluates a defined number of similar studies. It is quantitative in nature and can help assess contrasting study findings.

Tips for writing a good review article

Here are a few practices that can make the time-consuming process of writing a review article easier:

- Define your question: Take your time to identify the research question and carefully articulate the topic of your review paper. A good review should also add something new to the field in terms of a hypothesis, inference, or conclusion. A carefully defined scientific question will give you more clarity in determining the novelty of your inferences.

- Identify credible sources: Identify relevant as well as credible studies that you can base your review on, with the help of multiple databases or search engines. It is also a good idea to conduct another search once you have finished your article to avoid missing relevant studies published during the course of your writing.

- Take notes: A literature search involves extensive reading, which can make it difficult to recall relevant information subsequently. Therefore, make notes while conducting the literature search and note down the source references. This will ensure that you have sufficient information to start with when you finally get to writing.

- Describe the title, abstract, and introduction: A good starting point to begin structuring your review is by drafting the title, abstract, and introduction. Explicitly writing down what your review aims to address in the field will help shape the rest of your article.

- Be unbiased and critical: Evaluate every piece of evidence in a critical but unbiased manner. This will help you present a proper assessment and a critical discussion in your article.

- Include a good summary: End by stating the take-home message and identify the limitations of existing studies that need to be addressed through future studies.

- Ask for feedback: Ask a colleague to provide feedback on both the content and the language or tone of your article before you submit it.

- Check your journal’s guidelines: Some journals only publish reviews, while some only publish research articles. Further, all journals clearly indicate their aims and scope. Therefore, make sure to check the appropriateness of a journal before submitting your article.

Writing review articles, especially systematic reviews or meta-analyses, can seem like a daunting task. However, Elsevier Author Services can guide you by providing useful tips on how to write an impressive review article that stands out and gets published!

What are Implications in Research?

How to Write the Results Section: Guide to Structure and Key Points

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Scholarly Sources: What are They and Where can You Find Them?

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Insights blog

What is a review article?

Learn how to write a review article.

What is a review article? A review article can also be called a literature review, or a review of literature. It is a survey of previously published research on a topic. It should give an overview of current thinking on the topic. And, unlike an original research article, it will not present new experimental results.

Writing a review of literature is to provide a critical evaluation of the data available from existing studies. Review articles can identify potential research areas to explore next, and sometimes they will draw new conclusions from the existing data.

Why write a review article?

To provide a comprehensive foundation on a topic.

To explain the current state of knowledge.

To identify gaps in existing studies for potential future research.

To highlight the main methodologies and research techniques.

Did you know?

There are some journals that only publish review articles, and others that do not accept them.

Make sure you check the aims and scope of the journal you’d like to publish in to find out if it’s the right place for your review article.

How to write a review article

Below are 8 key items to consider when you begin writing your review article.

Check the journal’s aims and scope

Make sure you have read the aims and scope for the journal you are submitting to and follow them closely. Different journals accept different types of articles and not all will accept review articles, so it’s important to check this before you start writing.

Define your scope

Define the scope of your review article and the research question you’ll be answering, making sure your article contributes something new to the field.

As award-winning author Angus Crake told us, you’ll also need to “define the scope of your review so that it is manageable, not too large or small; it may be necessary to focus on recent advances if the field is well established.”

Finding sources to evaluate

When finding sources to evaluate, Angus Crake says it’s critical that you “use multiple search engines/databases so you don’t miss any important ones.”

For finding studies for a systematic review in medical sciences, read advice from NCBI .

Writing your title, abstract and keywords

Spend time writing an effective title, abstract and keywords. This will help maximize the visibility of your article online, making sure the right readers find your research. Your title and abstract should be clear, concise, accurate, and informative.

For more information and guidance on getting these right, read our guide to writing a good abstract and title and our researcher’s guide to search engine optimization .

Introduce the topic

Does a literature review need an introduction? Yes, always start with an overview of the topic and give some context, explaining why a review of the topic is necessary. Gather research to inform your introduction and make it broad enough to reach out to a large audience of non-specialists. This will help maximize its wider relevance and impact.

Don’t make your introduction too long. Divide the review into sections of a suitable length to allow key points to be identified more easily.

Include critical discussion

Make sure you present a critical discussion, not just a descriptive summary of the topic. If there is contradictory research in your area of focus, make sure to include an element of debate and present both sides of the argument. You can also use your review paper to resolve conflict between contradictory studies.

What researchers say

Angus Crake, researcher

As part of your conclusion, include making suggestions for future research on the topic. Focus on the goal to communicate what you understood and what unknowns still remains.

Use a critical friend

Always perform a final spell and grammar check of your article before submission.

You may want to ask a critical friend or colleague to give their feedback before you submit. If English is not your first language, think about using a language-polishing service.

Find out more about how Taylor & Francis Editing Services can help improve your manuscript before you submit.

What is the difference between a research article and a review article?

| Differences in... | ||

|---|---|---|

| Presents the viewpoint of the author | Critiques the viewpoint of other authors on a particular topic | |

| New content | Assessing already published content | |

| Depends on the word limit provided by the journal you submit to | Tends to be shorter than a research article, but will still need to adhere to words limit |

Before you submit your review article…

Complete this checklist before you submit your review article:

Have you checked the journal’s aims and scope?

Have you defined the scope of your article?

Did you use multiple search engines to find sources to evaluate?

Have you written a descriptive title and abstract using keywords?

Did you start with an overview of the topic?

Have you presented a critical discussion?

Have you included future suggestions for research in your conclusion?

Have you asked a friend to do a final spell and grammar check?

Expert help for your manuscript

Taylor & Francis Editing Services offers a full range of pre-submission manuscript preparation services to help you improve the quality of your manuscript and submit with confidence.

Related resources

How to edit your paper

Writing a scientific literature review

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

BP indicates bisphosphonate; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; and WJ-MSC, Wharton jelly–derived mesenchymal stem cell.

a Refers to the 4 prospective comparative studies.

A, Network plot of studies included in network meta-analysis on short-term pain management during activity. Circle size is proportional to the number of trials for each intervention, and the line thickness is proportional to the number of trials comparing the interventions. B, Network meta-analysis for short-term pain management during activity comparing pharmacological interventions with placebo. Data are presented as the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI for pain during activity. Values below 0 indicate that the treatment mentioned first (before the vs) is favored, whereas values above 0 indicate that the treatment mentioned last (after the vs) is favored. NSAID indicates nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

A, Network plot of studies included in network meta-analysis of pharmacological interventions regarding long-term pain management. Circle size is proportional to the number of trials for each intervention, and the line thickness is proportional to the number of trials comparing the interventions. B, Network meta-analysis for long-term pain management (nonspecified) comparing pharmacological interventions with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Data are presented as the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI for long-term pain outcomes. Values below 0 indicate that the treatment mentioned first (before the vs) is favored, whereas values above 0 indicate that the treatment mentioned last (after the vs) is favored.

A, Network plot of studies included in network meta-analysis of brace treatment regarding long-term pain management. Circle size is proportional to the number of trials for each intervention, and the line thickness is proportional to the number of trials comparing the interventions. B, Network meta-analysis for long-term pain management (nonspecified) comparing the treatment with various braces with no brace treatment. Data are presented as the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI for long-term pain. Values below 0 indicate that the treatment mentioned first (before the vs) is favored, whereas values above 0 indicate that the treatment mentioned last (after the vs) is favored regarding pain outcomes.

eAppendix . Supplemental methods

eTable 1. Search strategy

eTable 2. Inclusion criteria

eTable 3. Framework for the GRADE assessment

eTable 4. List of excluded studies

eTable 5. Characteristics of the included studies

eTable 6. Study quality of the included prospective, comparative studies

eTable 7. Estimates of effects and GRADE quality ratings for comparison of different pharmacological interventions for short-term pain during activity

eTable 8. Adverse events of the included studies

eFigure 1. Risk of bias assessment

eFigure 2. Node splitting: Short-term pain during activity

eFigure 3. P-score ranking: Short-term pain during activity

eFigure 4. Sensitivity analyses: Short-term pain during activity (walking and rising up)

eFigure 5. Sensitivity analyses: Short-term pain during activity (only walking)

eFigure 6. Node splitting: Pharmacological interventions (long-term pain)

eFigure 7. P-score ranking: Pharmacological interventions for long-term pain

eFigure 8. Node splitting: Braces (long-term pain)

eFigure 9. P-score ranking: Braces for long-term pain

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Alimy A , Anastasilakis AD , Carey JJ, et al. Conservative Treatments in the Management of Acute Painful Vertebral Compression Fractures : A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis . JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(9):e2432041. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.32041

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Conservative Treatments in the Management of Acute Painful Vertebral Compression Fractures : A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis

- 1 Department of Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

- 2 European Calcified Tissue Society Clinical Practice Action Group, Brussels, Belgium

- 3 Department of Endocrinology, 424 General Military Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece

- 4 Department of Rheumatology, Galway University Hospitals, Galway, Ireland

- 5 Interdisciplinary Department of Medicine, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy

- 6 Unit of Metabolic Bone and Thyroid Diseases, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Rome, Italy

- 7 Department of Rheumatology, MABLab ULR 4490, CHU Lille, University Lille, Lille, France

- 8 First Department of Propedeutic and Internal Medicine Centre of Expertise for Rare Endocrine Diseases, Medical School National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 9 Department of Rheumatology, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Question Which conservative treatment option is most beneficial regarding pain-related outcomes in acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (VCFs)?

Findings Using data from 20 trials involving 2102 patients, this systematic review and network meta-analysis evaluated conservative interventions, including bisphosphonates, calcitonin, teriparatide, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and braces, for the treatment of acute VCF. The short-term assessment indicated that calcitonin and NSAIDs were associated with decreased pain during activity, and the long-term assessment revealed that teriparatide was associated with lower pain levels compared with bisphosphonates.

Meaning These findings and currently established treatment strategies highlight the value of NSAIDs and teriparatide in managing pain in acute VCF, while emphasizing the need for further research.

Importance Osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) frequently cause substantial pain and reduced mobility, posing a major health problem. Despite the critical need for effective pain management to restore functionality and improve patient outcomes, the value of various conservative treatments for acute VCF has not been systematically investigated.

Objective To assess and compare different conservative treatment options in managing acute pain related to VCF.

Data Sources On May 16, 2023, 4 databases—PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and CINAHL—were searched. In addition, a gray literature search within Scopus and Embase was also conducted.

Study Selection Included studies were prospective comparative and randomized clinical trials that assessed conservative treatments for acute VCF.

Data Extraction and Synthesis Data extraction and synthesis were performed by 2 authors according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Network Meta-Analyses recommendations. A frequentist graph-theoretical model and a random-effects model were applied for the meta-analysis.

Main Outcomes and Measures Primary outcomes were short-term (4 weeks) pain during activity and long-term (latest available follow-up) nonspecified pain in patients with acute VCF.