- Ask a Librarian

Research: Overview & Approaches

- Getting Started with Undergraduate Research

- Planning & Getting Started

- Building Your Knowledge Base

- Locating Sources

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Creating a Literature Review

- Productivity & Organizing Research

- Scholarly and Professional Relationships

Introduction to Empirical Research

Databases for finding empirical research, guided search, google scholar, examples of empirical research, sources and further reading.

- Interpretive Research

- Action-Based Research

- Creative & Experimental Approaches

Your Librarian

- Introductory Video This video covers what empirical research is, what kinds of questions and methods empirical researchers use, and some tips for finding empirical research articles in your discipline.

- Guided Search: Finding Empirical Research Articles This is a hands-on tutorial that will allow you to use your own search terms to find resources.

- Study on radiation transfer in human skin for cosmetics

- Long-Term Mobile Phone Use and the Risk of Vestibular Schwannoma: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study

- Emissions Impacts and Benefits of Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles and Vehicle-to-Grid Services

- Review of design considerations and technological challenges for successful development and deployment of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles

- Endocrine disrupters and human health: could oestrogenic chemicals in body care cosmetics adversely affect breast cancer incidence in women?

- << Previous: Scholarly and Professional Relationships

- Next: Interpretive Research >>

- Last Updated: Aug 8, 2024 2:05 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.purdue.edu/research_approaches

Penn State University Libraries

Empirical research in the social sciences and education.

- What is Empirical Research and How to Read It

- Finding Empirical Research in Library Databases

- Designing Empirical Research

- Ethics, Cultural Responsiveness, and Anti-Racism in Research

- Citing, Writing, and Presenting Your Work

Contact the Librarian at your campus for more help!

Introduction: What is Empirical Research?

Empirical research is based on observed and measured phenomena and derives knowledge from actual experience rather than from theory or belief.

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

Key characteristics to look for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or phenomena being studied

- Description of the process used to study this population or phenomena, including selection criteria, controls, and testing instruments (such as surveys)

Another hint: some scholarly journals use a specific layout, called the "IMRaD" format, to communicate empirical research findings. Such articles typically have 4 components:

- Introduction : sometimes called "literature review" -- what is currently known about the topic -- usually includes a theoretical framework and/or discussion of previous studies

- Methodology: sometimes called "research design" -- how to recreate the study -- usually describes the population, research process, and analytical tools used in the present study

- Results : sometimes called "findings" -- what was learned through the study -- usually appears as statistical data or as substantial quotations from research participants

- Discussion : sometimes called "conclusion" or "implications" -- why the study is important -- usually describes how the research results influence professional practices or future studies

Reading and Evaluating Scholarly Materials

Reading research can be a challenge. However, the tutorials and videos below can help. They explain what scholarly articles look like, how to read them, and how to evaluate them:

- CRAAP Checklist A frequently-used checklist that helps you examine the currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, and purpose of an information source.

- IF I APPLY A newer model of evaluating sources which encourages you to think about your own biases as a reader, as well as concerns about the item you are reading.

- Credo Video: How to Read Scholarly Materials (4 min.)

- Credo Tutorial: How to Read Scholarly Materials

- Credo Tutorial: Evaluating Information

- Credo Video: Evaluating Statistics (4 min.)

- Credo Tutorial: Evaluating for Diverse Points of View

- Next: Finding Empirical Research in Library Databases >>

- Last Updated: Aug 8, 2024 4:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/emp

Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

Empirical research relies on gathering and studying real, observable data. The term ’empirical’ comes from the Greek word ’empeirikos,’ meaning ‘experienced’ or ‘based on experience.’ So, what is empirical research? Instead of using theories or opinions, empirical research depends on real data obtained through direct observation or experimentation.

Why Empirical Research?

Empirical research plays a key role in checking or improving current theories, providing a systematic way to grow knowledge across different areas. By focusing on objectivity, it makes research findings more trustworthy, which is critical in research fields like medicine, psychology, economics, and public policy. In the end, the strengths of empirical research lie in deepening our awareness of the world and improving our capacity to tackle problems wisely. 1,2

Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

There are two main types of empirical research methods – qualitative and quantitative. 3,4 Qualitative research delves into intricate phenomena using non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations, to offer in-depth insights into human experiences. In contrast, quantitative research analyzes numerical data to spot patterns and relationships, aiming for objectivity and the ability to apply findings to a wider context.

Steps for Conducting Empirical Research

When it comes to conducting research, there are some simple steps that researchers can follow. 5,6

- Create Research Hypothesis: Clearly state the specific question you want to answer or the hypothesis you want to explore in your study.

- Examine Existing Research: Read and study existing research on your topic. Understand what’s already known, identify existing gaps in knowledge, and create a framework for your own study based on what you learn.

- Plan Your Study: Decide how you’ll conduct your research—whether through qualitative methods, quantitative methods, or a mix of both. Choose suitable techniques like surveys, experiments, interviews, or observations based on your research question.

- Develop Research Instruments: Create reliable research collection tools, such as surveys or questionnaires, to help you collate data. Ensure these tools are well-designed and effective.

- Collect Data: Systematically gather the information you need for your research according to your study design and protocols using the chosen research methods.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the collected data using suitable statistical or qualitative methods that align with your research question and objectives.

- Interpret Results: Understand and explain the significance of your analysis results in the context of your research question or hypothesis.

- Draw Conclusions: Summarize your findings and draw conclusions based on the evidence. Acknowledge any study limitations and propose areas for future research.

Advantages of Empirical Research

Empirical research is valuable because it stays objective by relying on observable data, lessening the impact of personal biases. This objectivity boosts the trustworthiness of research findings. Also, using precise quantitative methods helps in accurate measurement and statistical analysis. This precision ensures researchers can draw reliable conclusions from numerical data, strengthening our understanding of the studied phenomena. 4

Disadvantages of Empirical Research

While empirical research has notable strengths, researchers must also be aware of its limitations when deciding on the right research method for their study.4 One significant drawback of empirical research is the risk of oversimplifying complex phenomena, especially when relying solely on quantitative methods. These methods may struggle to capture the richness and nuances present in certain social, cultural, or psychological contexts. Another challenge is the potential for confounding variables or biases during data collection, impacting result accuracy.

Tips for Empirical Writing

In empirical research, the writing is usually done in research papers, articles, or reports. The empirical writing follows a set structure, and each section has a specific role. Here are some tips for your empirical writing. 7

- Define Your Objectives: When you write about your research, start by making your goals clear. Explain what you want to find out or prove in a simple and direct way. This helps guide your research and lets others know what you have set out to achieve.

- Be Specific in Your Literature Review: In the part where you talk about what others have studied before you, focus on research that directly relates to your research question. Keep it short and pick studies that help explain why your research is important. This part sets the stage for your work.

- Explain Your Methods Clearly : When you talk about how you did your research (Methods), explain it in detail. Be clear about your research plan, who took part, and what you did; this helps others understand and trust your study. Also, be honest about any rules you follow to make sure your study is ethical and reproducible.

- Share Your Results Clearly : After doing your empirical research, share what you found in a simple way. Use tables or graphs to make it easier for your audience to understand your research. Also, talk about any numbers you found and clearly state if they are important or not. Ensure that others can see why your research findings matter.

- Talk About What Your Findings Mean: In the part where you discuss your research results, explain what they mean. Discuss why your findings are important and if they connect to what others have found before. Be honest about any problems with your study and suggest ideas for more research in the future.

- Wrap It Up Clearly: Finally, end your empirical research paper by summarizing what you found and why it’s important. Remind everyone why your study matters. Keep your writing clear and fix any mistakes before you share it. Ask someone you trust to read it and give you feedback before you finish.

References:

- Empirical Research in the Social Sciences and Education, Penn State University Libraries. Available online at https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/emp

- How to conduct empirical research, Emerald Publishing. Available online at https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/how-to/research-methods/conduct-empirical-research

- Empirical Research: Quantitative & Qualitative, Arrendale Library, Piedmont University. Available online at https://library.piedmont.edu/empirical-research

- Bouchrika, I. What Is Empirical Research? Definition, Types & Samples in 2024. Research.com, January 2024. Available online at https://research.com/research/what-is-empirical-research

- Quantitative and Empirical Research vs. Other Types of Research. California State University, April 2023. Available online at https://libguides.csusb.edu/quantitative

- Empirical Research, Definitions, Methods, Types and Examples, Studocu.com website. Available online at https://www.studocu.com/row/document/uganda-christian-university/it-research-methods/emperical-research-definitions-methods-types-and-examples/55333816

- Writing an Empirical Paper in APA Style. Psychology Writing Center, University of Washington. Available online at https://psych.uw.edu/storage/writing_center/APApaper.pdf

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

Ethics in Science: Importance, Principles & Guidelines

Presenting research data effectively through tables and figures, you may also like, the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), five things authors need to know when using..., 7 best referencing tools and citation management software..., maintaining academic integrity with paperpal’s generative ai writing....

Identifying Empirical Research Articles

Identifying empirical articles.

- Searching for Empirical Research Articles

What is Empirical Research?

An empirical research article reports the results of a study that uses data derived from actual observation or experimentation. Empirical research articles are examples of primary research. To learn more about the differences between primary and secondary research, see our related guide:

- Primary and Secondary Sources

By the end of this guide, you will be able to:

- Identify common elements of an empirical article

- Use a variety of search strategies to search for empirical articles within the library collection

Look for the IMRaD layout in the article to help identify empirical research. Sometimes the sections will be labeled differently, but the content will be similar.

- I ntroduction: why the article was written, research question or questions, hypothesis, literature review

- M ethods: the overall research design and implementation, description of sample, instruments used, how the authors measured their experiment

- R esults: output of the author's measurements, usually includes statistics of the author's findings

- D iscussion: the author's interpretation and conclusions about the results, limitations of study, suggestions for further research

Parts of an Empirical Research Article

Parts of an empirical article.

The screenshots below identify the basic IMRaD structure of an empirical research article.

Introduction

The introduction contains a literature review and the study's research hypothesis.

The method section outlines the research design, participants, and measures used.

Results

The results section contains statistical data (charts, graphs, tables, etc.) and research participant quotes.

The discussion section includes impacts, limitations, future considerations, and research.

Learn the IMRaD Layout: How to Identify an Empirical Article

This short video overviews the IMRaD method for identifying empirical research.

- Next: Searching for Empirical Research Articles >>

- Last Updated: Nov 16, 2023 8:24 AM

CityU Home - CityU Catalog

- University of Memphis Libraries

- Research Guides

Empirical Research: Defining, Identifying, & Finding

Defining empirical research, what is empirical research, quantitative or qualitative.

- Introduction

- Database Tools

- Search Terms

- Image Descriptions

Calfee & Chambliss (2005) (UofM login required) describe empirical research as a "systematic approach for answering certain types of questions." Those questions are answered "[t]hrough the collection of evidence under carefully defined and replicable conditions" (p. 43).

The evidence collected during empirical research is often referred to as "data."

Characteristics of Empirical Research

Emerald Publishing's guide to conducting empirical research identifies a number of common elements to empirical research:

- A research question , which will determine research objectives.

- A particular and planned design for the research, which will depend on the question and which will find ways of answering it with appropriate use of resources.

- The gathering of primary data , which is then analysed.

- A particular methodology for collecting and analysing the data, such as an experiment or survey.

- The limitation of the data to a particular group, area or time scale, known as a sample [emphasis added]: for example, a specific number of employees of a particular company type, or all users of a library over a given time scale. The sample should be somehow representative of a wider population.

- The ability to recreate the study and test the results. This is known as reliability .

- The ability to generalize from the findings to a larger sample and to other situations.

If you see these elements in a research article, you can feel confident that you have found empirical research. Emerald's guide goes into more detail on each element.

Empirical research methodologies can be described as quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both (usually called mixed-methods).

Ruane (2016) (UofM login required) gets at the basic differences in approach between quantitative and qualitative research:

- Quantitative research -- an approach to documenting reality that relies heavily on numbers both for the measurement of variables and for data analysis (p. 33).

- Qualitative research -- an approach to documenting reality that relies on words and images as the primary data source (p. 33).

Both quantitative and qualitative methods are empirical . If you can recognize that a research study is quantitative or qualitative study, then you have also recognized that it is empirical study.

Below are information on the characteristics of quantitative and qualitative research. This video from Scribbr also offers a good overall introduction to the two approaches to research methodology:

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

Researchers test hypotheses, or theories, based in assumptions about causality, i.e. we expect variable X to cause variable Y. Variables have to be controlled as much as possible to ensure validity. The results explain the relationship between the variables. Measures are based in pre-defined instruments.

Examples: experimental or quasi-experimental design, pretest & post-test, survey or questionnaire with closed-ended questions. Studies that identify factors that influence an outcomes, the utility of an intervention, or understanding predictors of outcomes.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Researchers explore “meaning individuals or groups ascribe to social or human problems (Creswell & Creswell, 2018, p3).” Questions and procedures emerge rather than being prescribed. Complexity, nuance, and individual meaning are valued. Research is both inductive and deductive. Data sources are multiple and varied, i.e. interviews, observations, documents, photographs, etc. The researcher is a key instrument and must be reflective of their background, culture, and experiences as influential of the research.

Examples: open question interviews and surveys, focus groups, case studies, grounded theory, ethnography, discourse analysis, narrative, phenomenology, participatory action research.

Calfee, R. C. & Chambliss, M. (2005). The design of empirical research. In J. Flood, D. Lapp, J. R. Squire, & J. Jensen (Eds.), Methods of research on teaching the English language arts: The methodology chapters from the handbook of research on teaching the English language arts (pp. 43-78). Routledge. http://ezproxy.memphis.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=125955&site=eds-live&scope=site .

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

How to... conduct empirical research . (n.d.). Emerald Publishing. https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/how-to/research-methods/conduct-empirical-research .

Scribbr. (2019). Quantitative vs. qualitative: The differences explained [video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a-XtVF7Bofg .

Ruane, J. M. (2016). Introducing social research methods : Essentials for getting the edge . Wiley-Blackwell. http://ezproxy.memphis.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1107215&site=eds-live&scope=site .

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Identifying Empirical Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 11:25 AM

- URL: https://libguides.memphis.edu/empirical-research

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Empirical Research: Definition, Methods, Types and Examples

Content Index

Empirical research: Definition

Empirical research: origin, quantitative research methods, qualitative research methods, steps for conducting empirical research, empirical research methodology cycle, advantages of empirical research, disadvantages of empirical research, why is there a need for empirical research.

Empirical research is defined as any research where conclusions of the study is strictly drawn from concretely empirical evidence, and therefore “verifiable” evidence.

This empirical evidence can be gathered using quantitative market research and qualitative market research methods.

For example: A research is being conducted to find out if listening to happy music in the workplace while working may promote creativity? An experiment is conducted by using a music website survey on a set of audience who are exposed to happy music and another set who are not listening to music at all, and the subjects are then observed. The results derived from such a research will give empirical evidence if it does promote creativity or not.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

You must have heard the quote” I will not believe it unless I see it”. This came from the ancient empiricists, a fundamental understanding that powered the emergence of medieval science during the renaissance period and laid the foundation of modern science, as we know it today. The word itself has its roots in greek. It is derived from the greek word empeirikos which means “experienced”.

In today’s world, the word empirical refers to collection of data using evidence that is collected through observation or experience or by using calibrated scientific instruments. All of the above origins have one thing in common which is dependence of observation and experiments to collect data and test them to come up with conclusions.

LEARN ABOUT: Causal Research

Types and methodologies of empirical research

Empirical research can be conducted and analysed using qualitative or quantitative methods.

- Quantitative research : Quantitative research methods are used to gather information through numerical data. It is used to quantify opinions, behaviors or other defined variables . These are predetermined and are in a more structured format. Some of the commonly used methods are survey, longitudinal studies, polls, etc

- Qualitative research: Qualitative research methods are used to gather non numerical data. It is used to find meanings, opinions, or the underlying reasons from its subjects. These methods are unstructured or semi structured. The sample size for such a research is usually small and it is a conversational type of method to provide more insight or in-depth information about the problem Some of the most popular forms of methods are focus groups, experiments, interviews, etc.

Data collected from these will need to be analysed. Empirical evidence can also be analysed either quantitatively and qualitatively. Using this, the researcher can answer empirical questions which have to be clearly defined and answerable with the findings he has got. The type of research design used will vary depending on the field in which it is going to be used. Many of them might choose to do a collective research involving quantitative and qualitative method to better answer questions which cannot be studied in a laboratory setting.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Research Questions and Questionnaires

Quantitative research methods aid in analyzing the empirical evidence gathered. By using these a researcher can find out if his hypothesis is supported or not.

- Survey research: Survey research generally involves a large audience to collect a large amount of data. This is a quantitative method having a predetermined set of closed questions which are pretty easy to answer. Because of the simplicity of such a method, high responses are achieved. It is one of the most commonly used methods for all kinds of research in today’s world.

Previously, surveys were taken face to face only with maybe a recorder. However, with advancement in technology and for ease, new mediums such as emails , or social media have emerged.

For example: Depletion of energy resources is a growing concern and hence there is a need for awareness about renewable energy. According to recent studies, fossil fuels still account for around 80% of energy consumption in the United States. Even though there is a rise in the use of green energy every year, there are certain parameters because of which the general population is still not opting for green energy. In order to understand why, a survey can be conducted to gather opinions of the general population about green energy and the factors that influence their choice of switching to renewable energy. Such a survey can help institutions or governing bodies to promote appropriate awareness and incentive schemes to push the use of greener energy.

Learn more: Renewable Energy Survey Template Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research

- Experimental research: In experimental research , an experiment is set up and a hypothesis is tested by creating a situation in which one of the variable is manipulated. This is also used to check cause and effect. It is tested to see what happens to the independent variable if the other one is removed or altered. The process for such a method is usually proposing a hypothesis, experimenting on it, analyzing the findings and reporting the findings to understand if it supports the theory or not.

For example: A particular product company is trying to find what is the reason for them to not be able to capture the market. So the organisation makes changes in each one of the processes like manufacturing, marketing, sales and operations. Through the experiment they understand that sales training directly impacts the market coverage for their product. If the person is trained well, then the product will have better coverage.

- Correlational research: Correlational research is used to find relation between two set of variables . Regression analysis is generally used to predict outcomes of such a method. It can be positive, negative or neutral correlation.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

For example: Higher educated individuals will get higher paying jobs. This means higher education enables the individual to high paying job and less education will lead to lower paying jobs.

- Longitudinal study: Longitudinal study is used to understand the traits or behavior of a subject under observation after repeatedly testing the subject over a period of time. Data collected from such a method can be qualitative or quantitative in nature.

For example: A research to find out benefits of exercise. The target is asked to exercise everyday for a particular period of time and the results show higher endurance, stamina, and muscle growth. This supports the fact that exercise benefits an individual body.

- Cross sectional: Cross sectional study is an observational type of method, in which a set of audience is observed at a given point in time. In this type, the set of people are chosen in a fashion which depicts similarity in all the variables except the one which is being researched. This type does not enable the researcher to establish a cause and effect relationship as it is not observed for a continuous time period. It is majorly used by healthcare sector or the retail industry.

For example: A medical study to find the prevalence of under-nutrition disorders in kids of a given population. This will involve looking at a wide range of parameters like age, ethnicity, location, incomes and social backgrounds. If a significant number of kids coming from poor families show under-nutrition disorders, the researcher can further investigate into it. Usually a cross sectional study is followed by a longitudinal study to find out the exact reason.

- Causal-Comparative research : This method is based on comparison. It is mainly used to find out cause-effect relationship between two variables or even multiple variables.

For example: A researcher measured the productivity of employees in a company which gave breaks to the employees during work and compared that to the employees of the company which did not give breaks at all.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Some research questions need to be analysed qualitatively, as quantitative methods are not applicable there. In many cases, in-depth information is needed or a researcher may need to observe a target audience behavior, hence the results needed are in a descriptive analysis form. Qualitative research results will be descriptive rather than predictive. It enables the researcher to build or support theories for future potential quantitative research. In such a situation qualitative research methods are used to derive a conclusion to support the theory or hypothesis being studied.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

- Case study: Case study method is used to find more information through carefully analyzing existing cases. It is very often used for business research or to gather empirical evidence for investigation purpose. It is a method to investigate a problem within its real life context through existing cases. The researcher has to carefully analyse making sure the parameter and variables in the existing case are the same as to the case that is being investigated. Using the findings from the case study, conclusions can be drawn regarding the topic that is being studied.

For example: A report mentioning the solution provided by a company to its client. The challenges they faced during initiation and deployment, the findings of the case and solutions they offered for the problems. Such case studies are used by most companies as it forms an empirical evidence for the company to promote in order to get more business.

- Observational method: Observational method is a process to observe and gather data from its target. Since it is a qualitative method it is time consuming and very personal. It can be said that observational research method is a part of ethnographic research which is also used to gather empirical evidence. This is usually a qualitative form of research, however in some cases it can be quantitative as well depending on what is being studied.

For example: setting up a research to observe a particular animal in the rain-forests of amazon. Such a research usually take a lot of time as observation has to be done for a set amount of time to study patterns or behavior of the subject. Another example used widely nowadays is to observe people shopping in a mall to figure out buying behavior of consumers.

- One-on-one interview: Such a method is purely qualitative and one of the most widely used. The reason being it enables a researcher get precise meaningful data if the right questions are asked. It is a conversational method where in-depth data can be gathered depending on where the conversation leads.

For example: A one-on-one interview with the finance minister to gather data on financial policies of the country and its implications on the public.

- Focus groups: Focus groups are used when a researcher wants to find answers to why, what and how questions. A small group is generally chosen for such a method and it is not necessary to interact with the group in person. A moderator is generally needed in case the group is being addressed in person. This is widely used by product companies to collect data about their brands and the product.

For example: A mobile phone manufacturer wanting to have a feedback on the dimensions of one of their models which is yet to be launched. Such studies help the company meet the demand of the customer and position their model appropriately in the market.

- Text analysis: Text analysis method is a little new compared to the other types. Such a method is used to analyse social life by going through images or words used by the individual. In today’s world, with social media playing a major part of everyone’s life, such a method enables the research to follow the pattern that relates to his study.

For example: A lot of companies ask for feedback from the customer in detail mentioning how satisfied are they with their customer support team. Such data enables the researcher to take appropriate decisions to make their support team better.

Sometimes a combination of the methods is also needed for some questions that cannot be answered using only one type of method especially when a researcher needs to gain a complete understanding of complex subject matter.

We recently published a blog that talks about examples of qualitative data in education ; why don’t you check it out for more ideas?

Learn More: Data Collection Methods: Types & Examples

Since empirical research is based on observation and capturing experiences, it is important to plan the steps to conduct the experiment and how to analyse it. This will enable the researcher to resolve problems or obstacles which can occur during the experiment.

Step #1: Define the purpose of the research

This is the step where the researcher has to answer questions like what exactly do I want to find out? What is the problem statement? Are there any issues in terms of the availability of knowledge, data, time or resources. Will this research be more beneficial than what it will cost.

Before going ahead, a researcher has to clearly define his purpose for the research and set up a plan to carry out further tasks.

Step #2 : Supporting theories and relevant literature

The researcher needs to find out if there are theories which can be linked to his research problem . He has to figure out if any theory can help him support his findings. All kind of relevant literature will help the researcher to find if there are others who have researched this before, or what are the problems faced during this research. The researcher will also have to set up assumptions and also find out if there is any history regarding his research problem

Step #3: Creation of Hypothesis and measurement

Before beginning the actual research he needs to provide himself a working hypothesis or guess what will be the probable result. Researcher has to set up variables, decide the environment for the research and find out how can he relate between the variables.

Researcher will also need to define the units of measurements, tolerable degree for errors, and find out if the measurement chosen will be acceptable by others.

Step #4: Methodology, research design and data collection

In this step, the researcher has to define a strategy for conducting his research. He has to set up experiments to collect data which will enable him to propose the hypothesis. The researcher will decide whether he will need experimental or non experimental method for conducting the research. The type of research design will vary depending on the field in which the research is being conducted. Last but not the least, the researcher will have to find out parameters that will affect the validity of the research design. Data collection will need to be done by choosing appropriate samples depending on the research question. To carry out the research, he can use one of the many sampling techniques. Once data collection is complete, researcher will have empirical data which needs to be analysed.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

Step #5: Data Analysis and result

Data analysis can be done in two ways, qualitatively and quantitatively. Researcher will need to find out what qualitative method or quantitative method will be needed or will he need a combination of both. Depending on the unit of analysis of his data, he will know if his hypothesis is supported or rejected. Analyzing this data is the most important part to support his hypothesis.

Step #6: Conclusion

A report will need to be made with the findings of the research. The researcher can give the theories and literature that support his research. He can make suggestions or recommendations for further research on his topic.

A.D. de Groot, a famous dutch psychologist and a chess expert conducted some of the most notable experiments using chess in the 1940’s. During his study, he came up with a cycle which is consistent and now widely used to conduct empirical research. It consists of 5 phases with each phase being as important as the next one. The empirical cycle captures the process of coming up with hypothesis about how certain subjects work or behave and then testing these hypothesis against empirical data in a systematic and rigorous approach. It can be said that it characterizes the deductive approach to science. Following is the empirical cycle.

- Observation: At this phase an idea is sparked for proposing a hypothesis. During this phase empirical data is gathered using observation. For example: a particular species of flower bloom in a different color only during a specific season.

- Induction: Inductive reasoning is then carried out to form a general conclusion from the data gathered through observation. For example: As stated above it is observed that the species of flower blooms in a different color during a specific season. A researcher may ask a question “does the temperature in the season cause the color change in the flower?” He can assume that is the case, however it is a mere conjecture and hence an experiment needs to be set up to support this hypothesis. So he tags a few set of flowers kept at a different temperature and observes if they still change the color?

- Deduction: This phase helps the researcher to deduce a conclusion out of his experiment. This has to be based on logic and rationality to come up with specific unbiased results.For example: In the experiment, if the tagged flowers in a different temperature environment do not change the color then it can be concluded that temperature plays a role in changing the color of the bloom.

- Testing: This phase involves the researcher to return to empirical methods to put his hypothesis to the test. The researcher now needs to make sense of his data and hence needs to use statistical analysis plans to determine the temperature and bloom color relationship. If the researcher finds out that most flowers bloom a different color when exposed to the certain temperature and the others do not when the temperature is different, he has found support to his hypothesis. Please note this not proof but just a support to his hypothesis.

- Evaluation: This phase is generally forgotten by most but is an important one to keep gaining knowledge. During this phase the researcher puts forth the data he has collected, the support argument and his conclusion. The researcher also states the limitations for the experiment and his hypothesis and suggests tips for others to pick it up and continue a more in-depth research for others in the future. LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

There is a reason why empirical research is one of the most widely used method. There are a few advantages associated with it. Following are a few of them.

- It is used to authenticate traditional research through various experiments and observations.

- This research methodology makes the research being conducted more competent and authentic.

- It enables a researcher understand the dynamic changes that can happen and change his strategy accordingly.

- The level of control in such a research is high so the researcher can control multiple variables.

- It plays a vital role in increasing internal validity .

Even though empirical research makes the research more competent and authentic, it does have a few disadvantages. Following are a few of them.

- Such a research needs patience as it can be very time consuming. The researcher has to collect data from multiple sources and the parameters involved are quite a few, which will lead to a time consuming research.

- Most of the time, a researcher will need to conduct research at different locations or in different environments, this can lead to an expensive affair.

- There are a few rules in which experiments can be performed and hence permissions are needed. Many a times, it is very difficult to get certain permissions to carry out different methods of this research.

- Collection of data can be a problem sometimes, as it has to be collected from a variety of sources through different methods.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

Empirical research is important in today’s world because most people believe in something only that they can see, hear or experience. It is used to validate multiple hypothesis and increase human knowledge and continue doing it to keep advancing in various fields.

For example: Pharmaceutical companies use empirical research to try out a specific drug on controlled groups or random groups to study the effect and cause. This way, they prove certain theories they had proposed for the specific drug. Such research is very important as sometimes it can lead to finding a cure for a disease that has existed for many years. It is useful in science and many other fields like history, social sciences, business, etc.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

With the advancement in today’s world, empirical research has become critical and a norm in many fields to support their hypothesis and gain more knowledge. The methods mentioned above are very useful for carrying out such research. However, a number of new methods will keep coming up as the nature of new investigative questions keeps getting unique or changing.

Create a single source of real data with a built-for-insights platform. Store past data, add nuggets of insights, and import research data from various sources into a CRM for insights. Build on ever-growing research with a real-time dashboard in a unified research management platform to turn insights into knowledge.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Product or Service: Which is More Important? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Aug 13, 2024

Life@QuestionPro: Thomas Maiwald-Immer’s Experience

Aug 9, 2024

Top 13 Reporting Tools to Transform Your Data Insights & More

Aug 8, 2024

Employee Satisfaction: How to Boost Your Workplace Happiness?

Aug 7, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Empirical Economics

Journal of the Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna, Austria

- Exemplary topics are treatment effect estimation, policy evaluation, forecasting, and econometric methods.

- Contributions may focus on the estimation of established relationships between economic variables or on the testing of hypotheses.

- Emphasizes the replicability of empirical results: replication studies may be published as short papers.

- Follows a single-blind review procedure (authors’ names are known to reviewers, but reviewers are anonymous to authors).

- Submissions that have poor chances of receiving positive reviews are routinely rejected without sending the papers for review.

This is a transformative journal , you may have access to funding.

- Robert M. Kunst

- Bertrand Candelon,

- Subal C. Kumbhakar,

- Arthur H. O. van Soest,

- Joakim Westerlund

Societies and partnerships

Latest issue

Volume 67, Issue 2

Latest articles

Pandemic, policy, and markets: insights and learning from covid-19’s impact on global stock behavior.

- Shuxin Yang

Import shock and local labour market outcomes: A Sino-Indian case study

- Feiyang Shi

Modelling green knowledge production and environmental policies with semiparametric panel data regression models

- Antonio Musolesi

- Davide Golinelli

- Massimiliano Mazzanti

Unconditional cash transfers and child schooling: a meta-analysis

- Zhi Zheng Chong

- Siew Yee Lau

How do climate policy uncertainty and renewable energy and clean technology stock prices co-move? evidence from Canada

- Seyed Alireza Athari

- Dervis Kirikkaleli

Journal updates

Lawrence r. klein award 2021/2022.

This biannual prize is awarded for the best paper published in the journal Empirical Economics.

The Empirical Economics prize was awarded for the fi rst time by Springer in 2006, and was renamed in honor of the Nobel prize winner Lawrence R. Klein in 2013.

Journal information

- ABS Academic Journal Quality Guide

- Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) Journal Quality List

- Engineering Village – GEOBASE

- Google Scholar

- Japanese Science and Technology Agency (JST)

- Norwegian Register for Scientific Journals and Series

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- Research Papers in Economics (RePEc)

- Social Science Citation Index

- TD Net Discovery Service

- UGC-CARE List (India)

Rights and permissions

Editorial policies

© Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

La Salle University

Connelly library, library main menu.

- Course Reserves

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Study Room Use & Reservations

- Technology & Printing

- Citation Guides

- Reserve Library Space

- Request Instruction

- Copyright Information

- Guides for Faculty

Special Collections

- University Archives

- Historical & Cultural Collections

- Rare Bibles & Prayer Books

- Historical Research Guides

- Information & Guidelines

- Staff Directory

- Meet with a Librarian

- Directions & Building Maps

Research Hub

Qualitative and quantitative research, what is "empirical research".

- empirical research

- Locating Articles in Cinahl and PsycInfo

- Locating Articles in PubMed

- Getting the Articles

Empirical research is based on observed and measured phenomena and derives knowledge from actual experience rather than from theory or belief.

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

Key characteristics to look for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or phenomena being studied

- Description of the process used to study this population or phenomena, including selection criteria, controls, and testing instruments (such as surveys)

Another hint: some scholarly journals use a specific layout, called the "IMRaD" format, to communicate empirical research findings. Such articles typically have 4 components:

- Introduction : sometimes called "literature review" -- what is currently known about the topic -- usually includes a theoretical framework and/or discussion of previous studies

- Methodology: sometimes called "research design" -- how to recreate the study -- usually describes the population, research process, and analytical tools

- Results : sometimes called "findings" -- what was learned through the study -- usually appears as statistical data or as substantial quotations from research participants

- Discussion : sometimes called "conclusion" or "implications" -- why the study is important -- usually describes how the research results influence professional practices or future studies

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Locating Articles in Cinahl and PsycInfo >>

Chat Assistance

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

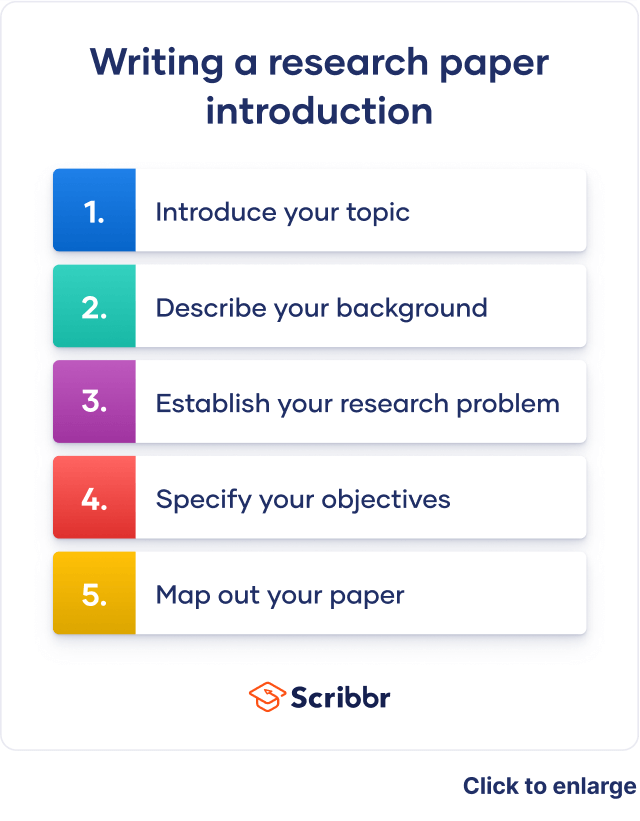

Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on September 24, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on March 27, 2023.

The introduction to a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your topic and get the reader interested

- Provide background or summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Detail your specific research problem and problem statement

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The introduction looks slightly different depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument by engaging with a variety of sources.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: introduce your topic, step 2: describe the background, step 3: establish your research problem, step 4: specify your objective(s), step 5: map out your paper, research paper introduction examples, frequently asked questions about the research paper introduction.

The first job of the introduction is to tell the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening hook.

The hook is a striking opening sentence that clearly conveys the relevance of your topic. Think of an interesting fact or statistic, a strong statement, a question, or a brief anecdote that will get the reader wondering about your topic.

For example, the following could be an effective hook for an argumentative paper about the environmental impact of cattle farming:

A more empirical paper investigating the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues in adolescent girls might use the following hook:

Don’t feel that your hook necessarily has to be deeply impressive or creative. Clarity and relevance are still more important than catchiness. The key thing is to guide the reader into your topic and situate your ideas.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

This part of the introduction differs depending on what approach your paper is taking.

In a more argumentative paper, you’ll explore some general background here. In a more empirical paper, this is the place to review previous research and establish how yours fits in.

Argumentative paper: Background information

After you’ve caught your reader’s attention, specify a bit more, providing context and narrowing down your topic.

Provide only the most relevant background information. The introduction isn’t the place to get too in-depth; if more background is essential to your paper, it can appear in the body .

Empirical paper: Describing previous research

For a paper describing original research, you’ll instead provide an overview of the most relevant research that has already been conducted. This is a sort of miniature literature review —a sketch of the current state of research into your topic, boiled down to a few sentences.

This should be informed by genuine engagement with the literature. Your search can be less extensive than in a full literature review, but a clear sense of the relevant research is crucial to inform your own work.

Begin by establishing the kinds of research that have been done, and end with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to respond to.

The next step is to clarify how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses.

Argumentative paper: Emphasize importance

In an argumentative research paper, you can simply state the problem you intend to discuss, and what is original or important about your argument.

Empirical paper: Relate to the literature

In an empirical research paper, try to lead into the problem on the basis of your discussion of the literature. Think in terms of these questions:

- What research gap is your work intended to fill?

- What limitations in previous work does it address?

- What contribution to knowledge does it make?

You can make the connection between your problem and the existing research using phrases like the following.

| Although has been studied in detail, insufficient attention has been paid to . | You will address a previously overlooked aspect of your topic. |

| The implications of study deserve to be explored further. | You will build on something suggested by a previous study, exploring it in greater depth. |

| It is generally assumed that . However, this paper suggests that … | You will depart from the consensus on your topic, establishing a new position. |

Now you’ll get into the specifics of what you intend to find out or express in your research paper.

The way you frame your research objectives varies. An argumentative paper presents a thesis statement, while an empirical paper generally poses a research question (sometimes with a hypothesis as to the answer).

Argumentative paper: Thesis statement

The thesis statement expresses the position that the rest of the paper will present evidence and arguments for. It can be presented in one or two sentences, and should state your position clearly and directly, without providing specific arguments for it at this point.

Empirical paper: Research question and hypothesis

The research question is the question you want to answer in an empirical research paper.

Present your research question clearly and directly, with a minimum of discussion at this point. The rest of the paper will be taken up with discussing and investigating this question; here you just need to express it.

A research question can be framed either directly or indirectly.

- This study set out to answer the following question: What effects does daily use of Instagram have on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls?

- We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls.

If your research involved testing hypotheses , these should be stated along with your research question. They are usually presented in the past tense, since the hypothesis will already have been tested by the time you are writing up your paper.

For example, the following hypothesis might respond to the research question above:

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

The final part of the introduction is often dedicated to a brief overview of the rest of the paper.

In a paper structured using the standard scientific “introduction, methods, results, discussion” format, this isn’t always necessary. But if your paper is structured in a less predictable way, it’s important to describe the shape of it for the reader.

If included, the overview should be concise, direct, and written in the present tense.

- This paper will first discuss several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then will go on to …

- This paper first discusses several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then goes on to …

Full examples of research paper introductions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

Are cows responsible for climate change? A recent study (RIVM, 2019) shows that cattle farmers account for two thirds of agricultural nitrogen emissions in the Netherlands. These emissions result from nitrogen in manure, which can degrade into ammonia and enter the atmosphere. The study’s calculations show that agriculture is the main source of nitrogen pollution, accounting for 46% of the country’s total emissions. By comparison, road traffic and households are responsible for 6.1% each, the industrial sector for 1%. While efforts are being made to mitigate these emissions, policymakers are reluctant to reckon with the scale of the problem. The approach presented here is a radical one, but commensurate with the issue. This paper argues that the Dutch government must stimulate and subsidize livestock farmers, especially cattle farmers, to transition to sustainable vegetable farming. It first establishes the inadequacy of current mitigation measures, then discusses the various advantages of the results proposed, and finally addresses potential objections to the plan on economic grounds.

The rise of social media has been accompanied by a sharp increase in the prevalence of body image issues among women and girls. This correlation has received significant academic attention: Various empirical studies have been conducted into Facebook usage among adolescent girls (Tiggermann & Slater, 2013; Meier & Gray, 2014). These studies have consistently found that the visual and interactive aspects of the platform have the greatest influence on body image issues. Despite this, highly visual social media (HVSM) such as Instagram have yet to be robustly researched. This paper sets out to address this research gap. We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls. It was hypothesized that daily Instagram use would be associated with an increase in body image concerns and a decrease in self-esteem ratings.

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, March 27). Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, writing a research paper conclusion | step-by-step guide, research paper format | apa, mla, & chicago templates, what is your plagiarism score.

Free APA Journals ™ Articles

Recently published articles from subdisciplines of psychology covered by more than 90 APA Journals™ publications.

For additional free resources (such as article summaries, podcasts, and more), please visit the Highlights in Psychological Research page.

- Basic / Experimental Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Core of Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology, School Psychology, and Training

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology & Medicine

- Industrial / Organizational Psychology & Management

- Neuroscience & Cognition

- Social Psychology & Social Processes

- Moving While Black: Intergroup Attitudes Influence Judgments of Speed (PDF, 71KB) Journal of Experimental Psychology: General February 2016 by Andreana C. Kenrick, Stacey Sinclair, Jennifer Richeson, Sara C. Verosky, and Janetta Lun

- Recognition Without Awareness: Encoding and Retrieval Factors (PDF, 116KB) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition September 2015 by Fergus I. M. Craik, Nathan S. Rose, and Nigel Gopie

- The Tip-of-the-Tongue Heuristic: How Tip-of-the-Tongue States Confer Perceptibility on Inaccessible Words (PDF, 91KB) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition September 2015 by Anne M. Cleary and Alexander B. Claxton

- Cognitive Processes in the Breakfast Task: Planning and Monitoring (PDF, 146KB) Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology / Revue canadienne de psychologie expérimentale September 2015 by Nathan S. Rose, Lin Luo, Ellen Bialystok, Alexandra Hering, Karen Lau, and Fergus I. M. Craik

- Searching for Explanations: How the Internet Inflates Estimates of Internal Knowledge (PDF, 138KB) Journal of Experimental Psychology: General June 2015 by Matthew Fisher, Mariel K. Goddu, and Frank C. Keil

- Client Perceptions of Corrective Experiences in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Motivational Interviewing for Generalized Anxiety Disorder: An Exploratory Pilot Study (PDF, 62KB) Journal of Psychotherapy Integration March 2017 by Jasmine Khattra, Lynne Angus, Henny Westra, Christianne Macaulay, Kathrin Moertl, and Michael Constantino

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Developmental Trajectories Related to Parental Expressed Emotion (PDF, 160KB) Journal of Abnormal Psychology February 2016 by Erica D. Musser, Sarah L. Karalunas, Nathan Dieckmann, Tara S. Peris, and Joel T. Nigg

- The Integrated Scientist-Practitioner: A New Model for Combining Research and Clinical Practice in Fee-For-Service Settings (PDF, 58KB) Professional Psychology: Research and Practice December 2015 by Jenna T. LeJeune and Jason B. Luoma

- Psychotherapists as Gatekeepers: An Evidence-Based Case Study Highlighting the Role and Process of Letter Writing for Transgender Clients (PDF, 76KB) Psychotherapy September 2015 by Stephanie L. Budge

- Perspectives of Family and Veterans on Family Programs to Support Reintegration of Returning Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PDF, 70KB) Psychological Services August 2015 by Ellen P. Fischer, Michelle D. Sherman, Jean C. McSweeney, Jeffrey M. Pyne, Richard R. Owen, and Lisa B. Dixon

- "So What Are You?": Inappropriate Interview Questions for Psychology Doctoral and Internship Applicants (PDF, 79KB) Training and Education in Professional Psychology May 2015 by Mike C. Parent, Dana A. Weiser, and Andrea McCourt

- Cultural Competence as a Core Emphasis of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy (PDF, 81KB) Psychoanalytic Psychology April 2015 by Pratyusha Tummala-Narra

- The Role of Gratitude in Spiritual Well-Being in Asymptomatic Heart Failure Patients (PDF, 123KB) Spirituality in Clinical Practice March 2015 by Paul J. Mills, Laura Redwine, Kathleen Wilson, Meredith A. Pung, Kelly Chinh, Barry H. Greenberg, Ottar Lunde, Alan Maisel, Ajit Raisinghani, Alex Wood, and Deepak Chopra

- Nepali Bhutanese Refugees Reap Support Through Community Gardening (PDF, 104KB) International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation January 2017 by Monica M. Gerber, Jennifer L. Callahan, Danielle N. Moyer, Melissa L. Connally, Pamela M. Holtz, and Beth M. Janis

- Does Monitoring Goal Progress Promote Goal Attainment? A Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Evidence (PDF, 384KB) Psychological Bulletin February 2016 by Benjamin Harkin, Thomas L. Webb, Betty P. I. Chang, Andrew Prestwich, Mark Conner, Ian Kellar, Yael Benn, and Paschal Sheeran

- Youth Violence: What We Know and What We Need to Know (PDF, 388KB) American Psychologist January 2016 by Brad J. Bushman, Katherine Newman, Sandra L. Calvert, Geraldine Downey, Mark Dredze, Michael Gottfredson, Nina G. Jablonski, Ann S. Masten, Calvin Morrill, Daniel B. Neill, Daniel Romer, and Daniel W. Webster

- Supervenience and Psychiatry: Are Mental Disorders Brain Disorders? (PDF, 113KB) Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology November 2015 by Charles M. Olbert and Gary J. Gala

- Constructing Psychological Objects: The Rhetoric of Constructs (PDF, 108KB) Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology November 2015 by Kathleen L. Slaney and Donald A. Garcia

- Expanding Opportunities for Diversity in Positive Psychology: An Examination of Gender, Race, and Ethnicity (PDF, 119KB) Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne August 2015 by Meghana A. Rao and Stewart I. Donaldson

- Racial Microaggression Experiences and Coping Strategies of Black Women in Corporate Leadership (PDF, 132KB) Qualitative Psychology August 2015 by Aisha M. B. Holder, Margo A. Jackson, and Joseph G. Ponterotto

- An Appraisal Theory of Empathy and Other Vicarious Emotional Experiences (PDF, 151KB) Psychological Review July 2015 by Joshua D. Wondra and Phoebe C. Ellsworth

- An Attachment Theoretical Framework for Personality Disorders (PDF, 100KB) Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne May 2015 by Kenneth N. Levy, Benjamin N. Johnson, Tracy L. Clouthier, J. Wesley Scala, and Christina M. Temes

- Emerging Approaches to the Conceptualization and Treatment of Personality Disorder (PDF, 111KB) Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne May 2015 by John F. Clarkin, Kevin B. Meehan, and Mark F. Lenzenweger

- A Complementary Processes Account of the Development of Childhood Amnesia and a Personal Past (PDF, 585KB) Psychological Review April 2015 by Patricia J. Bauer

- Terminal Decline in Well-Being: The Role of Social Orientation (PDF, 238KB) Psychology and Aging March 2016 by Denis Gerstorf, Christiane A. Hoppmann, Corinna E. Löckenhoff, Frank J. Infurna, Jürgen Schupp, Gert G. Wagner, and Nilam Ram

- Student Threat Assessment as a Standard School Safety Practice: Results From a Statewide Implementation Study (PDF, 97KB) School Psychology Quarterly June 2018 by Dewey Cornell, Jennifer L. Maeng, Anna Grace Burnette, Yuane Jia, Francis Huang, Timothy Konold, Pooja Datta, Marisa Malone, and Patrick Meyer

- Can a Learner-Centered Syllabus Change Students’ Perceptions of Student–Professor Rapport and Master Teacher Behaviors? (PDF, 90KB) Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology September 2016 by Aaron S. Richmond, Jeanne M. Slattery, Nathanael Mitchell, Robin K. Morgan, and Jared Becknell

- Adolescents' Homework Performance in Mathematics and Science: Personal Factors and Teaching Practices (PDF, 170KB) Journal of Educational Psychology November 2015 by Rubén Fernández-Alonso, Javier Suárez-Álvarez, and José Muñiz

- Teacher-Ready Research Review: Clickers (PDF, 55KB) Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology September 2015 by R. Eric Landrum

- Enhancing Attention and Memory During Video-Recorded Lectures (PDF, 83KB) Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology March 2015 by Daniel L. Schacter and Karl K. Szpunar

- The Alleged "Ferguson Effect" and Police Willingness to Engage in Community Partnership (PDF, 70KB) Law and Human Behavior February 2016 by Scott E. Wolfe and Justin Nix

- Randomized Controlled Trial of an Internet Cognitive Behavioral Skills-Based Program for Auditory Hallucinations in Persons With Psychosis (PDF, 92KB) Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal September 2017 by Jennifer D. Gottlieb, Vasudha Gidugu, Mihoko Maru, Miriam C. Tepper, Matthew J. Davis, Jennifer Greenwold, Ruth A. Barron, Brian P. Chiko, and Kim T. Mueser

- Preventing Unemployment and Disability Benefit Receipt Among People With Mental Illness: Evidence Review and Policy Significance (PDF, 134KB) Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal June 2017 by Bonnie O'Day, Rebecca Kleinman, Benjamin Fischer, Eric Morris, and Crystal Blyler

- Sending Your Grandparents to University Increases Cognitive Reserve: The Tasmanian Healthy Brain Project (PDF, 88KB) Neuropsychology July 2016 by Megan E. Lenehan, Mathew J. Summers, Nichole L. Saunders, Jeffery J. Summers, David D. Ward, Karen Ritchie, and James C. Vickers

- The Foundational Principles as Psychological Lodestars: Theoretical Inspiration and Empirical Direction in Rehabilitation Psychology (PDF, 68KB) Rehabilitation Psychology February 2016 by Dana S. Dunn, Dawn M. Ehde, and Stephen T. Wegener

- Feeling Older and Risk of Hospitalization: Evidence From Three Longitudinal Cohorts (PDF, 55KB) Health Psychology Online First Publication — February 11, 2016 by Yannick Stephan, Angelina R. Sutin, and Antonio Terracciano

- Anger Intensification With Combat-Related PTSD and Depression Comorbidity (PDF, 81KB) Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy January 2016 by Oscar I. Gonzalez, Raymond W. Novaco, Mark A. Reger, and Gregory A. Gahm

- Special Issue on eHealth and mHealth: Challenges and Future Directions for Assessment, Treatment, and Dissemination (PDF, 32KB) Health Psychology December 2015 by Belinda Borrelli and Lee M. Ritterband

- Posttraumatic Growth Among Combat Veterans: A Proposed Developmental Pathway (PDF, 110KB) Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy July 2015 by Sylvia Marotta-Walters, Jaehwa Choi, and Megan Doughty Shaine

- Racial and Sexual Minority Women's Receipt of Medical Assistance to Become Pregnant (PDF, 111KB) Health Psychology June 2015 by Bernadette V. Blanchfield and Charlotte J. Patterson

- An Examination of Generational Stereotypes as a Path Towards Reverse Ageism (PDF, 205KB) The Psychologist-Manager Journal August 2017 By Michelle Raymer, Marissa Reed, Melissa Spiegel, and Radostina K. Purvanova

- Sexual Harassment: Have We Made Any Progress? (PDF, 121KB) Journal of Occupational Health Psychology July 2017 By James Campbell Quick and M. Ann McFadyen

- Multidimensional Suicide Inventory-28 (MSI-28) Within a Sample of Military Basic Trainees: An Examination of Psychometric Properties (PDF, 79KB) Military Psychology November 2015 By Serena Bezdjian, Danielle Burchett, Kristin G. Schneider, Monty T. Baker, and Howard N. Garb

- Cross-Cultural Competence: The Role of Emotion Regulation Ability and Optimism (PDF, 100KB) Military Psychology September 2015 By Bianca C. Trejo, Erin M. Richard, Marinus van Driel, and Daniel P. McDonald

- The Effects of Stress on Prospective Memory: A Systematic Review (PDF, 149KB) Psychology & Neuroscience September 2017 by Martina Piefke and Katharina Glienke

- Don't Aim Too High for Your Kids: Parental Overaspiration Undermines Students' Learning in Mathematics (PDF, 164KB) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology November 2016 by Kou Murayama, Reinhard Pekrun, Masayuki Suzuki, Herbert W. Marsh, and Stephanie Lichtenfeld

- Sex Differences in Sports Interest and Motivation: An Evolutionary Perspective (PDF, 155KB) Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences April 2016 by Robert O. Deaner, Shea M. Balish, and Michael P. Lombardo

- Asian Indian International Students' Trajectories of Depression, Acculturation, and Enculturation (PDF, 210KB) Asian American Journal of Psychology March 2016 By Dhara T. Meghani and Elizabeth A. Harvey

- Cynical Beliefs About Human Nature and Income: Longitudinal and Cross-Cultural Analyses (PDF, 163KB) January 2016 Journal of Personality and Social Psychology by Olga Stavrova and Daniel Ehlebracht

- Annual Review of Asian American Psychology, 2014 (PDF, 384KB) Asian American Journal of Psychology December 2015 By Su Yeong Kim, Yishan Shen, Yang Hou, Kelsey E. Tilton, Linda Juang, and Yijie Wang

- Resilience in the Study of Minority Stress and Health of Sexual and Gender Minorities (PDF, 40KB) Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity September 2015 by Ilan H. Meyer

- Self-Reported Psychopathy and Its Association With Criminal Cognition and Antisocial Behavior in a Sample of University Undergraduates (PDF, 91KB) Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement July 2015 by Samantha J. Riopka, Richard B. A. Coupland, and Mark E. Olver

Journals Publishing Resource Center

Find resources for writing, reviewing, and editing articles for publishing with APA Journals™.

Visit the resource center

Journals information

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Journal statistics and operations data

- Special Issues

- Email alerts

- Copyright and permissions

Contact APA Publications

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Types of research papers

Analytical research paper

Argumentative or persuasive paper, definition paper, compare and contrast paper, cause and effect paper, interpretative paper, experimental research paper, survey research paper, frequently asked questions about the different types of research papers, related articles.

There are multiple different types of research papers. It is important to know which type of research paper is required for your assignment, as each type of research paper requires different preparation. Below is a list of the most common types of research papers.

➡️ Read more: What is a research paper?

In an analytical research paper you:

- pose a question

- collect relevant data from other researchers

- analyze their different viewpoints

You focus on the findings and conclusions of other researchers and then make a personal conclusion about the topic. It is important to stay neutral and not show your own negative or positive position on the matter.

The argumentative paper presents two sides of a controversial issue in one paper. It is aimed at getting the reader on the side of your point of view.

You should include and cite findings and arguments of different researchers on both sides of the issue, but then favor one side over the other and try to persuade the reader of your side. Your arguments should not be too emotional though, they still need to be supported with logical facts and statistical data.

Tip: Avoid expressing too much emotion in a persuasive paper.

The definition paper solely describes facts or objective arguments without using any personal emotion or opinion of the author. Its only purpose is to provide information. You should include facts from a variety of sources, but leave those facts unanalyzed.

Compare and contrast papers are used to analyze the difference between two:

Make sure to sufficiently describe both sides in the paper, and then move on to comparing and contrasting both thesis and supporting one.

Cause and effect papers are usually the first types of research papers that high school and college students write. They trace probable or expected results from a specific action and answer the main questions "Why?" and "What?", which reflect effects and causes.

In business and education fields, cause and effect papers will help trace a range of results that could arise from a particular action or situation.

An interpretative paper requires you to use knowledge that you have gained from a particular case study, for example a legal situation in law studies. You need to write the paper based on an established theoretical framework and use valid supporting data to back up your statement and conclusion.

This type of research paper basically describes a particular experiment in detail. It is common in fields like: