Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 30, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and...

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Qualitative Methods

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The word qualitative implies an emphasis on the qualities of entities and on processes and meanings that are not experimentally examined or measured [if measured at all] in terms of quantity, amount, intensity, or frequency. Qualitative researchers stress the socially constructed nature of reality, the intimate relationship between the researcher and what is studied, and the situational constraints that shape inquiry. Such researchers emphasize the value-laden nature of inquiry. They seek answers to questions that stress how social experience is created and given meaning. In contrast, quantitative studies emphasize the measurement and analysis of causal relationships between variables, not processes. Qualitative forms of inquiry are considered by many social and behavioral scientists to be as much a perspective on how to approach investigating a research problem as it is a method.

Denzin, Norman. K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Introduction: The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman. K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 3 rd edition. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005), p. 10.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Below are the three key elements that define a qualitative research study and the applied forms each take in the investigation of a research problem.

- Naturalistic -- refers to studying real-world situations as they unfold naturally; non-manipulative and non-controlling; the researcher is open to whatever emerges [i.e., there is a lack of predetermined constraints on findings].

- Emergent -- acceptance of adapting inquiry as understanding deepens and/or situations change; the researcher avoids rigid designs that eliminate responding to opportunities to pursue new paths of discovery as they emerge.

- Purposeful -- cases for study [e.g., people, organizations, communities, cultures, events, critical incidences] are selected because they are “information rich” and illuminative. That is, they offer useful manifestations of the phenomenon of interest; sampling is aimed at insight about the phenomenon, not empirical generalization derived from a sample and applied to a population.

The Collection of Data

- Data -- observations yield a detailed, "thick description" [in-depth understanding]; interviews capture direct quotations about people’s personal perspectives and lived experiences; often derived from carefully conducted case studies and review of material culture.

- Personal experience and engagement -- researcher has direct contact with and gets close to the people, situation, and phenomenon under investigation; the researcher’s personal experiences and insights are an important part of the inquiry and critical to understanding the phenomenon.

- Empathic neutrality -- an empathic stance in working with study respondents seeks vicarious understanding without judgment [neutrality] by showing openness, sensitivity, respect, awareness, and responsiveness; in observation, it means being fully present [mindfulness].

- Dynamic systems -- there is attention to process; assumes change is ongoing, whether the focus is on an individual, an organization, a community, or an entire culture, therefore, the researcher is mindful of and attentive to system and situational dynamics.

The Analysis

- Unique case orientation -- assumes that each case is special and unique; the first level of analysis is being true to, respecting, and capturing the details of the individual cases being studied; cross-case analysis follows from and depends upon the quality of individual case studies.

- Inductive analysis -- immersion in the details and specifics of the data to discover important patterns, themes, and inter-relationships; begins by exploring, then confirming findings, guided by analytical principles rather than rules.

- Holistic perspective -- the whole phenomenon under study is understood as a complex system that is more than the sum of its parts; the focus is on complex interdependencies and system dynamics that cannot be reduced in any meaningful way to linear, cause and effect relationships and/or a few discrete variables.

- Context sensitive -- places findings in a social, historical, and temporal context; researcher is careful about [even dubious of] the possibility or meaningfulness of generalizations across time and space; emphasizes careful comparative case study analysis and extrapolating patterns for possible transferability and adaptation in new settings.

- Voice, perspective, and reflexivity -- the qualitative methodologist owns and is reflective about her or his own voice and perspective; a credible voice conveys authenticity and trustworthiness; complete objectivity being impossible and pure subjectivity undermining credibility, the researcher's focus reflects a balance between understanding and depicting the world authentically in all its complexity and of being self-analytical, politically aware, and reflexive in consciousness.

Berg, Bruce Lawrence. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences . 8th edition. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2012; Denzin, Norman. K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Handbook of Qualitative Research . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000; Marshall, Catherine and Gretchen B. Rossman. Designing Qualitative Research . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Basic Research Design for Qualitative Studies

Unlike positivist or experimental research that utilizes a linear and one-directional sequence of design steps, there is considerable variation in how a qualitative research study is organized. In general, qualitative researchers attempt to describe and interpret human behavior based primarily on the words of selected individuals [a.k.a., “informants” or “respondents”] and/or through the interpretation of their material culture or occupied space. There is a reflexive process underpinning every stage of a qualitative study to ensure that researcher biases, presuppositions, and interpretations are clearly evident, thus ensuring that the reader is better able to interpret the overall validity of the research. According to Maxwell (2009), there are five, not necessarily ordered or sequential, components in qualitative research designs. How they are presented depends upon the research philosophy and theoretical framework of the study, the methods chosen, and the general assumptions underpinning the study. Goals Describe the central research problem being addressed but avoid describing any anticipated outcomes. Questions to ask yourself are: Why is your study worth doing? What issues do you want to clarify, and what practices and policies do you want it to influence? Why do you want to conduct this study, and why should the reader care about the results? Conceptual Framework Questions to ask yourself are: What do you think is going on with the issues, settings, or people you plan to study? What theories, beliefs, and prior research findings will guide or inform your research, and what literature, preliminary studies, and personal experiences will you draw upon for understanding the people or issues you are studying? Note to not only report the results of other studies in your review of the literature, but note the methods used as well. If appropriate, describe why earlier studies using quantitative methods were inadequate in addressing the research problem. Research Questions Usually there is a research problem that frames your qualitative study and that influences your decision about what methods to use, but qualitative designs generally lack an accompanying hypothesis or set of assumptions because the findings are emergent and unpredictable. In this context, more specific research questions are generally the result of an interactive design process rather than the starting point for that process. Questions to ask yourself are: What do you specifically want to learn or understand by conducting this study? What do you not know about the things you are studying that you want to learn? What questions will your research attempt to answer, and how are these questions related to one another? Methods Structured approaches to applying a method or methods to your study help to ensure that there is comparability of data across sources and researchers and, thus, they can be useful in answering questions that deal with differences between phenomena and the explanation for these differences [variance questions]. An unstructured approach allows the researcher to focus on the particular phenomena studied. This facilitates an understanding of the processes that led to specific outcomes, trading generalizability and comparability for internal validity and contextual and evaluative understanding. Questions to ask yourself are: What will you actually do in conducting this study? What approaches and techniques will you use to collect and analyze your data, and how do these constitute an integrated strategy? Validity In contrast to quantitative studies where the goal is to design, in advance, “controls” such as formal comparisons, sampling strategies, or statistical manipulations to address anticipated and unanticipated threats to validity, qualitative researchers must attempt to rule out most threats to validity after the research has begun by relying on evidence collected during the research process itself in order to effectively argue that any alternative explanations for a phenomenon are implausible. Questions to ask yourself are: How might your results and conclusions be wrong? What are the plausible alternative interpretations and validity threats to these, and how will you deal with these? How can the data that you have, or that you could potentially collect, support or challenge your ideas about what’s going on? Why should we believe your results? Conclusion Although Maxwell does not mention a conclusion as one of the components of a qualitative research design, you should formally conclude your study. Briefly reiterate the goals of your study and the ways in which your research addressed them. Discuss the benefits of your study and how stakeholders can use your results. Also, note the limitations of your study and, if appropriate, place them in the context of areas in need of further research.

Chenail, Ronald J. Introduction to Qualitative Research Design. Nova Southeastern University; Heath, A. W. The Proposal in Qualitative Research. The Qualitative Report 3 (March 1997); Marshall, Catherine and Gretchen B. Rossman. Designing Qualitative Research . 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999; Maxwell, Joseph A. "Designing a Qualitative Study." In The SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods . Leonard Bickman and Debra J. Rog, eds. 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2009), p. 214-253; Qualitative Research Methods. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Yin, Robert K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish . 2nd edition. New York: Guilford, 2015.

Strengths of Using Qualitative Methods

The advantage of using qualitative methods is that they generate rich, detailed data that leave the participants' perspectives intact and provide multiple contexts for understanding the phenomenon under study. In this way, qualitative research can be used to vividly demonstrate phenomena or to conduct cross-case comparisons and analysis of individuals or groups.

Among the specific strengths of using qualitative methods to study social science research problems is the ability to:

- Obtain a more realistic view of the lived world that cannot be understood or experienced in numerical data and statistical analysis;

- Provide the researcher with the perspective of the participants of the study through immersion in a culture or situation and as a result of direct interaction with them;

- Allow the researcher to describe existing phenomena and current situations;

- Develop flexible ways to perform data collection, subsequent analysis, and interpretation of collected information;

- Yield results that can be helpful in pioneering new ways of understanding;

- Respond to changes that occur while conducting the study ]e.g., extended fieldwork or observation] and offer the flexibility to shift the focus of the research as a result;

- Provide a holistic view of the phenomena under investigation;

- Respond to local situations, conditions, and needs of participants;

- Interact with the research subjects in their own language and on their own terms; and,

- Create a descriptive capability based on primary and unstructured data.

Anderson, Claire. “Presenting and Evaluating Qualitative Research.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 74 (2010): 1-7; Denzin, Norman. K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Handbook of Qualitative Research . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Limitations of Using Qualitative Methods

It is very much true that most of the limitations you find in using qualitative research techniques also reflect their inherent strengths . For example, small sample sizes help you investigate research problems in a comprehensive and in-depth manner. However, small sample sizes undermine opportunities to draw useful generalizations from, or to make broad policy recommendations based upon, the findings. Additionally, as the primary instrument of investigation, qualitative researchers are often embedded in the cultures and experiences of others. However, cultural embeddedness increases the opportunity for bias generated from conscious or unconscious assumptions about the study setting to enter into how data is gathered, interpreted, and reported.

Some specific limitations associated with using qualitative methods to study research problems in the social sciences include the following:

- Drifting away from the original objectives of the study in response to the changing nature of the context under which the research is conducted;

- Arriving at different conclusions based on the same information depending on the personal characteristics of the researcher;

- Replication of a study is very difficult;

- Research using human subjects increases the chance of ethical dilemmas that undermine the overall validity of the study;

- An inability to investigate causality between different research phenomena;

- Difficulty in explaining differences in the quality and quantity of information obtained from different respondents and arriving at different, non-consistent conclusions;

- Data gathering and analysis is often time consuming and/or expensive;

- Requires a high level of experience from the researcher to obtain the targeted information from the respondent;

- May lack consistency and reliability because the researcher can employ different probing techniques and the respondent can choose to tell some particular stories and ignore others; and,

- Generation of a significant amount of data that cannot be randomized into manageable parts for analysis.

Research Tip

Human Subject Research and Institutional Review Board Approval

Almost every socio-behavioral study requires you to submit your proposed research plan to an Institutional Review Board. The role of the Board is to evaluate your research proposal and determine whether it will be conducted ethically and under the regulations, institutional polices, and Code of Ethics set forth by the university. The purpose of the review is to protect the rights and welfare of individuals participating in your study. The review is intended to ensure equitable selection of respondents, that you have met the requirements for obtaining informed consent , that there is clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university [read: no lawsuits!], and that privacy and confidentiality are maintained throughout the research process and beyond. Go to the USC IRB website for detailed information and templates of forms you need to submit before you can proceed. If you are unsure whether your study is subject to IRB review, consult with your professor or academic advisor.

Chenail, Ronald J. Introduction to Qualitative Research Design. Nova Southeastern University; Labaree, Robert V. "Working Successfully with Your Institutional Review Board: Practical Advice for Academic Librarians." College and Research Libraries News 71 (April 2010): 190-193.

Another Research Tip

Finding Examples of How to Apply Different Types of Research Methods

SAGE publications is a major publisher of studies about how to design and conduct research in the social and behavioral sciences. Their SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases database includes contents from books, articles, encyclopedias, handbooks, and videos covering social science research design and methods including the complete Little Green Book Series of Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences and the Little Blue Book Series of Qualitative Research techniques. The database also includes case studies outlining the research methods used in real research projects. This is an excellent source for finding definitions of key terms and descriptions of research design and practice, techniques of data gathering, analysis, and reporting, and information about theories of research [e.g., grounded theory]. The database covers both qualitative and quantitative research methods as well as mixed methods approaches to conducting research.

SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases

NOTE : For a list of online communities, research centers, indispensable learning resources, and personal websites of leading qualitative researchers, GO HERE .

For a list of scholarly journals devoted to the study and application of qualitative research methods, GO HERE .

- << Previous: 6. The Methodology

- Next: Quantitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: Aug 30, 2024 10:02 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on 4 April 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 30 January 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analysing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analysing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, and history.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organisation?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography, action research, phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasise different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organisations to understand their cultures. | |

| Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. | |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves ‘instruments’ in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analysing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organise your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorise your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analysing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasise different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorise common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analysing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analysing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalisability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalisable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labour-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organisation to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organise your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, January 30). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/introduction-to-qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Subject Research

- Qualitative Research Resources

- Writing Up Your Research

Qualitative Research Resources: Writing Up Your Research

Created by health science librarians.

- What is Qualitative Research?

- Qualitative Research Basics

- Special Topics

- Training Opportunities: UNC & Beyond

- Help at UNC

- Qualitative Software for Coding/Analysis

- Software for Audio, Video, Online Surveys

- Finding Qualitative Studies

- Assessing Qualitative Research

About this Page

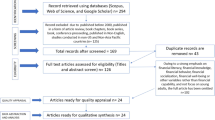

Writing conventions for qualitative research, sample size/sampling:.

- Integrating Qualitative Research into Systematic Reviews

- Publishing Qualitative Research

- Presenting Qualitative Research

- Qualitative & Libraries: a few gems

- Data Repositories

Why is this information important?

- The conventions of good writing and research reporting are different for qualitative and quantitative research.

- Your article will be more likely to be published if you make sure you follow appropriate conventions in your writing.

On this page you will find the following helpful resources:

- Articles with information on what journal editors look for in qualitative research articles.

- Articles and books on the craft of collating qualitative data into a research article.

These articles provide tips on what journal editors look for when they read qualitative research papers for potential publication. Also see Assessing Qualitative Research tab in this guide for additional information that may be helpful to authors.

Belgrave, L., D. Zablotsky and M.A. Guadagno.(2002). How do we talk to each other? Writing qualitative research for quantitative readers . Qualitative Health Research , 12(10),1427-1439.

Hunt, Brandon. (2011) Publishing Qualitative Research in Counseling Journals . Journal of Counseling and Development 89(3):296-300.

Fetters, Michael and Dawn Freshwater. (2015). Publishing a Methodological Mixed Methods Research Article. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 9(3): 203-213.

Koch, Lynn C., Tricia Niesz, and Henry McCarthy. (2014). Understanding and Reporting Qualitative Research: An Analytic Review and Recommendations for Submitting Authors. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 57(3):131-143.

Morrow, Susan L. (2005) Quality and Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology ; Journal of Counseling Psychology 52(2):250-260.

Oliver, Deborah P. (2011) "Rigor in Qualitative Research." Research on Aging 33(4): 359-360.

Sandelowski, M., & Leeman, J. (2012). Writing usable qualitative health research findings . Qual Health Res, 22(10), 1404-1413.

Schoenberg, Nancy E., Miller, Edward A., and Pruchno, Rachel. (2011) The qualitative portfolio at The Gerontologist : strong and getting stronger. Gerontologist 51(3): 281-284.

Weaver-Hightower, M. B. (2019). How to write qualitative research . [e-book]

Sidhu, Kalwant, Roger Jones, and Fiona Stevenson (2017). Publishing qualitative research in medical journals. Br J Gen Pract ; 67 (658): 229-230. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp17X690821 PMID: 28450340

- This article is based on a workshop on publishing qualitative studies held at the Society for Academic Primary Care Annual Conference, Dublin, July 2016.

Smith, Mary Lee.(1987) Publishing Qualitative Research. American Educational Research Journal 24(2): 173-183.

Tong, Allison, Sainsbury, Peter, Craig, Jonathan ; Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups , International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 19, Issue 6, 1 December 2007, Pages 349–357, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 .

Tracy, Sarah. (2010) Qualitative Quality: Eight 'Big-Tent' Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qualitative Inquiry 16(10):837-51.

Because reviewers are not always familiar with qualitative methods, they may ask for explanation or justification of your methods when you submit an article. Because different disciplines,different qualitative methods, and different contexts may dictate different approaches to this issue, you may want to consult articles in your field and in target journals for publication. Additionally, here are some articles that may be helpful in thinking about this issue.

Bonde, Donna. (2013). Qualitative Interviews: When Enough is Enough . Research by Design.

Guest, Greg, Arwen Bunce, and Laura Johnson. (2006) How Many Interviews are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 18(1): 59-82.

Hennink, Monique and Bonnie N. Kaiser. (2022) Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests . Social Science & Medicine 292:114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523. Epub 2021 Nov 2. PMID: 34785096.

Morse, Janice M. (2015) "Data Were Saturated..." Qualitative Health Research 25(5): 587-88 . doi:10.1177/1049732315576699.

Nelson, J. (2016) "Using Conceptual Depth Criteria: Addressing the Challenge of Reaching Saturation in Qualitative Research." Qualitative Research, December. doi:10.1177/1468794116679873.

Patton, Michael Quinn. (2015) "Chapter 5: Designing Qualitative Studies, Module 30 Purposeful Sampling and Case Selection. In Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, Fourth edition, pp. 264-72. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc. ISBN: 978-1-4129-7212-3

Small, Mario Luis. (2009) 'How Many Cases Do I Need?': On Science and the Logic of Case-Based Selection in Field-Based Research. Ethnography 10(1): 538.

Search the UNC-CH catalog for books about qualitative writing . Selected general books from the catalog are listed below. If you are a researcher at another institution, ask your librarian for assistance locating similar books in your institution's catalog or ordering them via InterLibrary Loan.

Oft quoted and food for thought

- Morse, J. M. (1997). " Perfectly healthy, but dead": the myth of inter-rater reliability. DOI:10.1177/104973239700700401 Editorial

- Silberzahn, R., Uhlmann, E. L., Martin, D. P., Anselmi, P., Aust, F., Awtrey, E., ... & Carlsson, R. (2018). Many analysts, one data set: Making transparent how variations in analytic choices affect results. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychologi

- << Previous: Assessing Qualitative Research

- Next: Integrating Qualitative Research into Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2024 4:11 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/qual

Qualitative Research Essay Examples

A qualitative research essay describes non-numerical findings of an idea, opinion, or process. These data are usually obtained through in-depth interviews, observation, or focus group discussions. Besides, you should indicate the selected research method. It is a short paper format, so don’t be tempted to go into unnecessary details.

For example, if your topic is Apple performance management, you should focus on the long-term efficiency of the company rather than its annual indexes. Leave the figures for a quantitative research project.

Check our qualitative research essay examples to get an idea of what the task requires from you. Here the topics range from psychology and linguistics to sociology and economics.

163 Best Qualitative Research Essay Examples

Evolution of amazon business model.

- Subjects: Business Company Analysis

- Words: 2080

Physical Education Curriculum

- Subjects: Curriculum Development Education

- Words: 5011

Cause and Effect of Cell Phone Usage Among High School Students from U.S. and Middle East

- Subjects: Education Writing & Assignments

- Words: 1218

Impact of Employee Motivation in Organizational Performance

- Subjects: Business Management

- Words: 1490

Epidemiological Studies of Tuberculosis

- Subjects: Epidemiology Health & Medicine

- Words: 1357

Jewel Production and Its Purpose

- Words: 2435

Training programs for semiliterate and illiterate populations in Swaziland

- Subjects: Health & Medicine Healthcare Institution

- Words: 4727

Air Care Gap Analysis

- Subjects: Consumer Science Economics

- Words: 1691

The Removal of the Compulsory Retirement Age to Employ People Between the Ages of 65 and 80

- Subjects: Labor Law Law

- Words: 1257

Relationship Between Sleep and Depression in Adolescence

- Subjects: Psychological Issues Psychology

- Words: 2186

Improving Customer Service in a Nigerian Musical Instrument Company

- Subjects: Business E-Commerce

- Words: 6393

Child Behavior Today and Ten Years Ago

- Subjects: Sociological Theories Sociology

- Words: 1391

Research Methods in Linguistics

- Subjects: Language Use Linguistics

Washback Effect of School-Based Assessment on Teaching and Learning in Hong Kong

- Subjects: Education Education Theories

- Words: 2258

The Real World of Management

- Words: 3925

Effects of Transnational Organized Crime on Foreign Politics

- Subjects: Literature World Literature

- Words: 1934

The Concept of Product Development

- Words: 1428

Risk Analysis Process

- Words: 2108

Qualitative Research Method Analysis

- Subjects: Math Sciences

- Words: 1766

Mobile Marketing: The Hotelier’s Point of View

- Subjects: Business Marketing

- Words: 6940

Enterprise Resource Planning System’s Role in an Organization

- Subjects: Business Logistics

- Words: 3598

Virgin Australia Airline Quality Management System

- Subjects: Business Strategy

- Words: 4273

Critical Success Factors for the Implementation of System in the State of Qatar

- Words: 2159

Multicultural Training of Counselors Increases Competency

- Words: 3396

Relationship between Mood and Opinion

- Words: 1439

Development of Training and Mentoring Program

- Words: 1068

Gender and Education: Australian Single-Sex Schools

- Subjects: Education Education Perception

- Words: 3022

Managing Challenges in Schools

- Words: 1658

Law Enforcement Race and Domestic Calls

- Subjects: Law Enforcement Politics & Government

- Words: 4150

Phenomenology and Hermeneutics Research Methodologies

- Words: 2980

Operational Management Effectiveness

- Words: 3220

Free News and Readers Preferences Correlation

- Subjects: Entertainment & Media World News

- Words: 4752

The High Infant and Perinatal Mortality Rates in Chicago

- Subjects: Health & Medicine Healthcare Research

Spirituality in the Workplace

- Subjects: Business Business Ethics

- Words: 2495

L1 and L2 Glosses in Vocabulary Retention and Memorisation

- Subjects: Linguistics Teaching

Social Media and Older Australians

- Subjects: Entertainment & Media Social Media Advertising

- Words: 1397

Conflict in Syria: Opportunity for Future Democratisation?

- Subjects: Political Culture Politics & Government

- Words: 4486

Green Energy Brand Strategy

- Words: 4223

Homeland Security Department

- Subjects: Homeland Security Law

Cultural and Diversity Management Interview

- Subjects: Business Corporate Culture

- Words: 1384

Conflicts in Syria Present No Opportunity for Future Democratization

Mobile systems uses and impact on business.

- Words: 4162

Stop-and-Frisk Policy in New York

- Words: 2246

Recovering Energy from Waste

- Subjects: Environment Recycling

- Words: 1711

Cross Cultural Management and International Business

- Words: 2773

Peer Assessment as a Teaching Strategy

- Subjects: Education Pedagogical Approaches

- Words: 5585

How We Can Attract Higher Quality Volunteers

- Subjects: Sociological Issues Sociology

- Words: 1156

The Importance of Education During Early Childhood

- Subjects: Education Learning Challenges

- Words: 1806

Trends in Branding: Context and Application

- Words: 3118

Grounded Theory

- Subjects: Philosophy Philosophy of Science

Spatial Data Division of Abu Dhabi Municipality

- Subjects: Data Tech & Engineering

- Words: 3603

Branding Concept Development

- Subjects: Brand Management Business

- Words: 3042

Anti-Inflammatory Diet and IBD Management in Adults

- Subjects: Gastroenterology Health & Medicine

- Words: 3404

Reliability of Incremental Shuttle Walk Test

- Subjects: Health & Medicine Rehabilitation

- Words: 2291

Nypro Inc’s Innovation Model

- Words: 1296

Consolidated Model for Teaching Adults

- Subjects: Adult Education Education

- Words: 2587

How Can an Organization Implement an Enterprise Resource Planning System?

- Words: 8238

Leadership at KTG: Challenges and an Action Plan

- Words: 3312

Special Interest Disability and Personal Interview

- Words: 2317

Qatar’s Economic Diversification

- Subjects: Economics Political Economy Processes

- Words: 3569

The Impact of Social Media on Political Leaders

- Subjects: Political Communication Politics & Government

- Words: 3351

Secure Online Shopping System Model on Customer Behavior

- Words: 4384

Criteria Used in Assessing the Relative Success of a Family Business

- Subjects: Economics Microeconomics

- Words: 2564

Green Computing in Botswana

- Subjects: Other Technology Tech & Engineering

Security Laws in Stock Markets

- Subjects: Business & Corporate Law Law

Public’s Opinion on Alternative Sentencing

- Subjects: Criminal Law Law

- Words: 5092

Strategic HRM in a Multinational Firm

- Words: 3734

The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank

- Subjects: Economics Finance

- Words: 4996

The Strategic Management of IKEA for Furniture Company in UAE or Gulf Corporate Countries

- Subjects: Business

- Words: 3444

Response to Intervention and Assistive Technology

- Subjects: Education Special Education

- Words: 1199

History of Vietnamese Diaspora

- Words: 1393

Carbon Management Accounting

- Subjects: Environment Planet Protection

- Words: 2218

Alcohol Abuse by Quentin McCarthy

- Subjects: Psychology Psychology of Abuse

- Words: 2759

Fifth Grade Students’ Learning Level

- Words: 1400

Planning Psycho-educational Preliminary Tasks

- Subjects: Psychological Principles Psychology

- Words: 1484

LVMH in China’s Domestic Market

- Subjects: Business Case Study

- Words: 4859

Data Warehouse and Data Mining in Business

- Words: 4190

Sustaining a Culture in Multinational Corporations

- Words: 2264

Microfinance in developing economies

- Words: 2209

Air Pollution: Public Health Impact

- Subjects: Climate Change Environment

- Words: 1200

Knowledge Strategy Report from the Ting Shao Kuang Art Gallery: In Search for a Proper Management Strategy

- Words: 1639

Isolated Families – Australia

Corporate social responsibilities in russia.

- Words: 1113