What do you mean by organizational structure? Acknowledging and harmonizing differences and commonalities in three prominent perspectives

- Point of View

- Open access

- Published: 11 October 2023

- Volume 13 , pages 1–11, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Daniel Albert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3888-1643 1

4980 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The organizational design literature stresses the importance of organizational structure to understand strategic change, performance, and innovation. However, prior studies diverge regarding the conceptualizations and operationalizations of structure. Organizational structure has been studied as an (1) arrangement of activities, (2) representation of decision-making, and (3) legal entities. In this point-of-view paper, the three prominent perspectives of organizational structure are discussed in terms of their commonalities, differences, and the need to study their relationship more thoroughly. Future research may not only wish to integrate these dimensions but also be more vocal about what type of organization structure is studied and why.

Similar content being viewed by others

Organization Theory

Organizations: Theoretical Debates and the Scope of Organizational Theory

Explore related subjects

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An important area of research in the organization design literature concerns the role of structure. Early research, including work by Chandler ( 1962 , 1991 ) and Burgelman ( 1983 ), has studied how strategy execution depends on a firm’s structure, and how that structure can influence future strategies. Moreover, prior work has explored organizational structure and its connection to strategic change (Gulati and Puranam 2009 ), performance (Csaszar 2012 ; Lee 2022 ), innovation (Eklund 2022 ; Keum and See 2017 ) and internal power dynamics (Bidwell 2012 ; Pfeffer 1981 ), among others.

What is surprising is the divergence in understanding what constitutes and defines organizational structure. This becomes particularly apparent when considering how structure has often been operationalized in prior studies. While there are a variety of conceptual and empirical approaches to organizational structure, this point of view paper focuses on three particularly prominent perspectives. Scholars of one stream of operationalization have argued that structure is how business activities are grouped and assessed in the form of distinct business units (or divisions) (Karim 2006 ; Mintzberg 1979 ), which may represent a company’s operating segments for internal and external reporting (Albert 2018 ). In another stream of operationalization, scholars argue that structure is inherent in the organizational chart, specifically, the chain of command and the allocation of decision-making responsibilities. Often, a simple yet powerful proxy has been to consider the roles assigned to the top management team members (Girod and Whittington 2015 ). Finally, a third type of operationalization of structure is the composition and arrangement of legal entities (Bethel and Liebeskind 1998 ; Zhou 2013 ), specifically, discrete subsidiaries constituting an organization’s business activities. This may be the most consequential understanding of structure as it relates to the containment of legal responsibilities.

These three perspectives overlap in some cases but may also characterize organizational structure differently in important ways. In a clear-cut case, a firm may consist of a top management team that perfectly reflects its business divisions and units, reported by consolidated but legally distinct entities. However, when examining the financial filings of different corporations, a different picture emerges as such clean alignment is often not the case. Not only are well-studied differences in the corporation's legal form (such as holding versus integrated) present, but top management responsibilities and reporting of business divisions often show that structure is indeed a multi-dimensional phenomenon in organizations.

To illustrate how different perspectives may lead to varying conclusions about organizational structure, two companies, the financial service firm Citigroup and the automotive company Ford Motor, are briefly discussed with respect to each perspective. Both Citigroup and Ford Motor are interesting cases, as they are large organizations with diversified business operations across various industry segments and a presence in multiple geographical markets. This complexity in business operations underscores the necessity of an organizational structure to implement and execute the firms' respective strategies.

The objective of this point of view is to emphasize and discuss the co-existence of fundamentally different measures and their underlying assumptions of organizational structure. These three perspectives highlight different aspects of organizational structure and can help reveal important nuances idiosyncratic to specific organizations. That is, complementing one perspective with one or two other perspectives can paint a more holistic picture of firm-specific structural designs. The “arrangement of activities” perspective provides generally a measure that captures sources of value creation, that is, the groupings of economic activities and knowledge. The “decision making representation” perspective provides generally a measure of hierarchical allocation of decision rights and has been likened to the level of centralization, that is, which responsibilities are specifically assigned to the highest level of decision-making. The “legal entities” perspective often captures decentralization as "truly" autonomous activities that can render integration more difficult and, therefore, imposes greater decentralization among such units.

A follow-up goal of this point of view paper is to discuss the implications and future research opportunities of clearly distinguishing between these perspectives in organizational design studies. A completely new area of research constitutes the inquiry of the relationships between these perspectives and whether and when alignment between the perspectives is enhancing or hindering performance, innovation, and strategic change. It is important to note that this point of view paper is not meant to provide an exhaustive list of perspectives of organizational structure, but to spark a constructive discussion around the theoretical and operational differences and commonalities between the arguably most prominent perspectives. Additional perspectives of organizational structure are discussed in the limitations section.

Three perspectives of structure

Structure as arrangement of activities.

This perspective suggests that groups of economic activities, managed and reviewed together, make up departments, units, and divisions that form the organizational structure (Joseph and Gaba 2020 ; Mintzberg 1979 ; Puranam and Vanneste 2016 ). In the middle of the twentieth century, Chandler ( 1962 ) observed that large American corporations not only diversified into a greater number of different business activities but also started to organize business activities into separately managed divisions, which are typically overseen by a corporate center unit. The organization of activities into compartments is often nested, that is, activities within a given compartment are further organized into subunits and so on. In a more general sense, such compartmentalization constitutes the division of labor (or specialization) in an organization, which can be organized along various dimensions. The most prevalent dimensions along which activities are organized into units include customer segments, products, geography, and functional domains, such as research and development, marketing, and sales activities (Puranam and Vanneste 2016 ).

The way activities are organized has been often related to archetypical designs, such as a more homogenous organization that is organized along functions and multi-divisional corporations that are more heterogenous in the activities making up business divisions (e.g., Raveendran 2020 ). The corporate center is often considered as a distinct unit of activities that holds the design rights of the organization, allowing it to organize these activities (Puranam 2018 ). The center may also play a coordinating role in the management of interdependencies between divisions to ensure alignment with corporate-level goals (Lawrence and Lorsch 1967 ) and foster value creation (Foss 1997 ).

Scholars of this perspective have studied how the arrangement of activities into compartments is associated with the propensity and type of reorganization (e.g., Karim 2006 ; Raveendran 2020 ), as well as its association with innovation outcomes (e.g., Karim and Kaul 2014 ). These two outcomes of interest are closely related, as compartments consist of employees and resources that constitute a source of knowledge that may be rearranged or combined with other units to address a (changing) market in novel and more efficient ways. Hence, this perspective may help to understand the sources of performance and innovation.

Illustration of arrangement of activities perspective

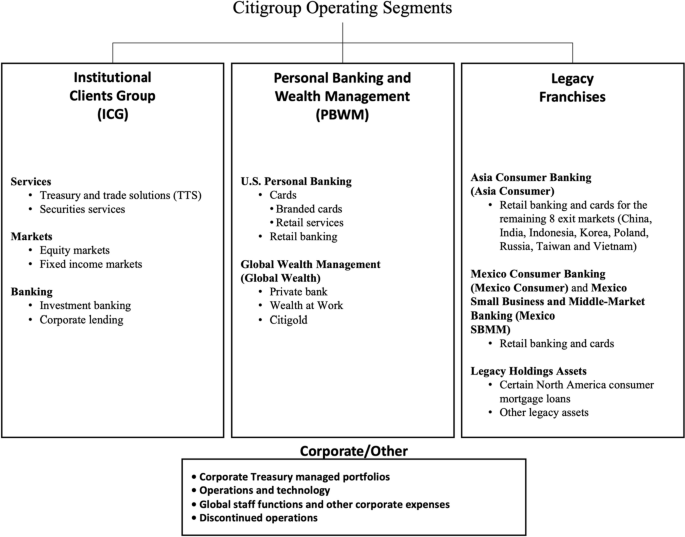

Figure 1 shows Citigroup’s operating business segments, which are in line with accounting regulations that require businesses to disclose operations in the way in which activities are managed internally and held accountable for cost and revenues (see Financial Accounting Standards No. 131). Accordingly, Citigroup operates three business segments, “Institutional Clients Group (ICG)”, “Personal Banking and Wealth Management (PBWM)” and “Legacy Franchises”, which are predominantly groupings of economic activities based on customer segments (i.e., institutional clients, private clients, and consumer clients). These groupings encompass various activities around this customer segment and the relevant product offerings. For example, the division Personal Banking encompasses activities for retail clients, such as Citibank’s physical retail network and online banking as well as private wealth operations for high-net-worth individuals. The respective segments may be understood as the organization’s business divisions, whereas further, nested, groupings exist within these divisions (e.g., U.S. Personal Banking constitutes a subunit with further subgroupings into Cards and Retail Banking operations). Supporting activities and operations that are not part of one of the three divisions are managed by the corporate center unit.

Citigroup’s operating business segments. This figure is the author’s own drawing but entirely based on Citigroup’s 2022 10-K report (page 2)

In Table 1 , the operating business segments are shown for the automotive company Ford. Accordingly, Ford operates six main segments (and one reconciliation of debt segment), “Ford Blue”, “Ford Model e”, “Ford Pro”, “Ford Next”, “Ford Credit”, and “Corporate Other”. These groupings encompass various product and customer segment activities, such as the “Ford Blue” legacy business of internal combustion engine automotives, under the Ford and Lincoln brands. Electric vehicle-related activities are grouped under “Ford Model e”, whereas “Ford Pro” groups activities to address corporate clients who seek to optimize and maintain fleets. Noteworthy is also the segment “Ford Next”, which is a grouping of investment activities into emerging business models. While these segments (i.e., divisions) encompass various activities, information is limited with respect to any nested groupings within these segments (or a potential lack thereof).

Structure as decision making representation

This perspective suggests that the job roles in the top management team (TMT) are reflective of the organizational structure, as executives are charged to oversee certain activities (Girod and Whittington 2015 ; Guadalupe et al. 2013 ). At first glance, this understanding is fairly similar to that of the arrangement of activities. At a closer look, however, the TMT structure perspective is more indicative of an information processing perspective. At the center of the information processing perspective lies hierarchy as a mechanism to cope with information uncertainty and resolve conflicts (Galbraith 1974 ). Moreover, information processing has long been considered as the way in which key decision-makers can ensure coordination and integration of units (Joseph and Gaba 2020 ). That is, the top management roles may in fact extend beyond the formal task structure and include the reintegration and coordination of activities more broadly.

The assignment of decision-making responsibilities can reveal how the organization “thinks” about interdependencies, such as the need to coordinate resources, the potential to leverage synergies and so forth. For example, roles that largely define autonomous areas of business allow managers to make decisions more independently from one another. In contrast, roles that are focused on dedicated functions, such as research and development, marketing, and finance often require greater coordination among managers (e.g., Hambrick et al. 2015 ). Hence, the decision-making representations in the top management team may be understood as a hierarchy mechanism to manage and even create interdependencies between activities. A case in point is the deliberate assignment of creating synergies between otherwise standalone units, for example, in the form of executives holding multiple roles that span several divisions.

While the assignment of decision-making responsibilities clearly relates to efforts of coordination and integration, it can also explain the emergence of internal power and politics dynamics (Cyert and March 1963 , Pfeffer 1981 ). For example, Romanelli and Tushman 9/14/2023 7:00:00 PM suggest that top management turnover is a measure of power dynamics in organizations and treat this as entirely distinct from organizational structure. Moreover, the upper echelons perspective has proposed that organizational choice and strategic outcomes are, at least in part, a direct reflection of the backgrounds of the leadership's individuals (Hambrick and Mason 1984 ), which suggests that design choices, such as organizational structure are decided under the auspice of the very same individuals (Puranam 2018 ) that researchers have used as a proxy to measure organizational structure. This emphasizes the importance of considering the TMT as a structure of decision-making representation rather than a measure of division of labor.

Perhaps it is this representational role of the TMT as a potential liaison between activity arrangements and decision-making, which Gaba and Joseph ( 2020 ) discuss as information processing, that has led some of the prior research argue that structure influences how decisions come about. Accordingly, decisions of reorganization and internal resource allocation are the result of a political negotiation process (Albert 2018 ; Bidwell 2012 ; Keum 2023 ; Pfeffer 1981 ; Pfeffer and Salancik 1974 ). Hence, this perspective may help understand the role of structure as a process that shapes decisions (Burgelman 1983 ).

Illustration of decision-making representation perspective

Table 2 shows Citigroup’s executive leadership team with each member’s specific job title that reflects the decision-making responsibilities. The team is made up of executives responsible for specific business divisions (e.g., one member carries the title CEO of Legacy Franchises), some members oversee particular geographical regions (e.g., one member carries the title CEO of Latin America), other members represent specific subsidiaries (e.g., one member carries the title CEO of Citibank N.A.), and again others are in charge of corporate functions (e.g., one member carries the title Head of Human Resources).

Table 3 shows Ford’s executive leadership team. The team is made up of executives responsible for business divisions, such as “President Ford Blue”, “CEO, Ford Pro” and “CEO, Ford Next”. In addition, executives represent particular activities of these divisions, such as “Chief Customer Officer, Ford Model e” and “Chief Customer Experience Officer, Ford Blue”. Similar to Citigroup, at Ford executives also represent geographical activities and various functional activities. Moreover, one executive represents a legal entity (Ford Next LLC), which is also a business segment (activity grouping).

Structure as legal entities

This perspective suggests that structure is delineated by legal boundaries, such as discrete subsidiaries that make up an organization’s operating units. This may constitute the most consequential understanding of structure as it relates to containment of legal responsibilities.

Thus, empirical studies have operationalized legal entities as a proxy for divisionalization in organizations (Argyres 1996 ; Zhou 2013 ) and degree of decentralization of research and development responsibilities (Arora et al. 2014 ). The way organizations are legally organized may be motivated by liability concerns, tax advantages, shareholder voting rights, as well as international law and compliance consideration (Bethel and Liebeskind 1998 ). Nevertheless, organizing into legally separate units can have important consequences for the management of the organization, such as limited economies of scope (see ibid.). For example, Monteiro et al. ( 2008 ) describe how subsidiaries in multinational corporations can become “isolated” from knowledge sharing with the rest of the organization. This isolation from intra-firm knowledge flows leads these subsidiaries to more likely underperform compared to less isolated subsidiaries.

It is important to note that legal structure is not always at the discretion of the organization. For example, the financial and economic crisis of 2007/8 has led legislators in some countries to introduce laws that require system-relevant banks to organize certain activities and assets into separate legal entities that contain losses and allow quicker resolvability in case the government decides to step in and take ownership stakes of affected units (Reuters 2014 ).

Legal structures, specifically in the context of multi-national organizations, have been studied with respect to decentralized decision-making, local market adaptation, and dynamics between subsidiaries and the headquarters (Bouquet and Birkinshaw 2008 ). Another aspect of studying legal entities in organizational design relates to internal reorganization. Legally separated activities are not only more straightforward to evaluate (i.e., greater transparency) as they typically maintain their own balance sheets and income statements, but they may also be easier to divest or spin-off, which provides the organization with greater flexibility. For example, the legal reorganization of Google into Alphabet in 2015 legally separated Google’s activities from all its “other bets”, which were run as their own legal organizations, with the goal for greater transparency and accountability (Zenger 2015 ). Moreover, the separation of activities into legal entities may also affect how easy or difficult it is for the organization to endorse cross-unit collaboration and execute internal reorganization without changing legal forms. Coordination cost between separate legal entities are greater, as more formal and legally binding contracts may need to be set.

Illustration of legal entities perspective

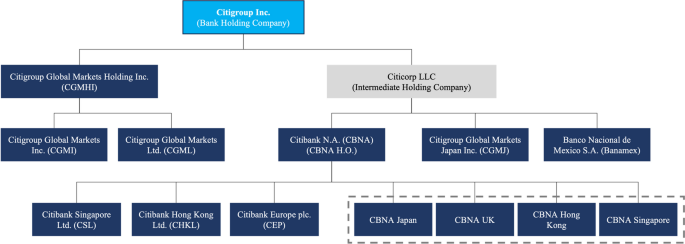

Figure 2 shows Citigroup’s legal structure. Accordingly, the organization is at the highest level a Bank Holding Company, which legally owns two (intermediate) holding entities, “Citigroup Global Markets Holdings Inc.” and “Citicorp LLC”. Each of these two entities owns additional subsidiaries, which are largely organized by region (these may hold additional subsidiaries). This structure is quite different from Citigroup’s management of operating activities as none of the business divisions is reflected in the legal structure.

Citigroup material legal entities. This figure is the author’s own drawing and a slight adaptation rom Citigroup’s publicly available presentation material via https://www.citigroup.com/rcs/citigpa/akpublic/storage/public/corp_struct.pdf , accessed on March 23, 2023. The dark blue boxed refer to operating material legal entities. The four boxes that are within the grey dashed rectangle are branches of Citibank N.A

Table 4 shows a list of legal entities reported by Ford in its annual report. Many of these subsidiaries are focused on regional activities and/or credit-related activities, which may be due to regulatory requirements of operating consumer financing activities. The legal entity Ford Next LLC is also its own business segment (i.e., an arrangement of activities reported as a managed division) and directly represented in the executive team. The Ford example does not provide much detail on the exact ownership structure among subsidiaries, which generally is indicative of a legal hierarchical structure of the respective legal entities. However, Ford European Holdings Inc. appears to own European subsidiaries, such as Ford Deutschland Holding GmbH, which in turn is the legal entity that owns subsidiaries in Germany and so on.

A path forward

The study of the commonalities , differences , and relationships between the three perspectives of organization structure—i.e., structure as arrangement of activities, decision-making representation, and legal entities—offers great potential for the field of organizational design. Previous research has often focused on one of these dimensions at a time to study organizational structure, but each perspective plays an important role in organizing and influencing decision-making.

Commonalities

All three perspectives share central ideas of organizational design. First, there is the notion that tasks are grouped and kept separate . The arrangement of activities perspective suggests that economic processes are managed and carried out together when these influence one another. Thus, this perspective stresses the grouping of tasks most forcefully of all the perspectives. However, the two other lines of research also reflect groupings of tasks. The decision-making representation perspective considers job titles and decision-making authority assigned to distinct members of the executive team to generally be related to how tasks are structured. Decision makers, therefore, oversee a particular task environment. The legal entity perspective proposes legal boundaries as delineations of responsibility and accountability. That is, legal separation and containment of financial accountability constitute somewhat binding modularity.

The three views also embrace the concept of hierarchy , albeit manifested differently. The arrangement of activities captures hierarchy by stressing that activity groups (i.e., units) can be nested, that is, a division is made up of several sub-units with own task responsibilities. Hierarchy in decision-making representation is captured by reporting lines and may be more focused on hierarchy as a means of conflict resolution and the diffusion of top-down ideas. The legal entity view shares similarity with the arrangement of activities perspective in that nested structures of subsidiaries can exist, but the “mechanism” of hierarchy is the ownership structure.

Differences

While the three perspectives have obvious similarities and overlap—after all, that is why scholars rely on one or the other perspectives to proxy organizational structure—these perspectives also capture distinct elements and, therefore, draw attention to different theoretical aspects of organization structure. The arrangement of activities perspective draws attention to the locus of value creation and innovation associated with structure. The grouping of activities influences whether synergies can be realized, goals achieved more quickly (Raveendran 2020 ) and whether knowledge can be recombined to seize innovation opportunities (Karim and Kaul 2014 ). The representation of decision-making perspectives draws attention to the top management team as structural authority to resolve conflicts between lower-level decision makers, and lobby for distinct operating activities in the organization. Moreover, top management plays a crucial role in the restructuring of the arrangement of activities and decisions with respect to changing the composition of legal entities. For example, political power of executives has been argued and shown to affect division reorganization decisions (Albert 2018 ) and allocation decisions of internal non-financial resources (Keum 2023 ). Finally, the legal entities perspective draws attention to structure as legal accountability and draws a sharp line between what is truly separate and what is more ‘loosely’ integrated. Consequently, arranging activities as legally separate entities often requires more costly coordination measures, such as formal contracts.

Theoretical and empirical questions around these differences may investigate the following claims.

A research focus on organizational structure as arrangement of activities may be of particular interest for the aim of understanding performance and innovation outcomes as economic activities are directly related to the process of value creation.

A research focus on organizational structure as decision-making representation may be of particular interest for the aim of understanding how strategic goals are formed, with respect to change and associated corporate reorganizations.

A research focus on organizational structure as legal entities may be of particular interest for the aim of understanding barriers to integration and realization of synergies as well as flexibility with respect to changes in corporate scope.

However, these preliminary statements about the different perspectives on organizational structure are not meant to encourage researchers to keep them strictly separate. Instead, future studies can explore these perspectives' theoretical relationships, offering wonderful opportunities for new insights, as will be discussed next.

Relationships

By investigating underlying connections between the different perspectives, future research may surface important insights about organizational design that can open up entirely new research programs. An essential theoretical question involves whether there are any directional relationships between specific perspectives. For example, when does top management team structure induce or follow other changes (in divisions and legal structure)? Karim and Williams ( 2012 ) show that changes in executives’ division responsibilities helps predict subsequent reorganizations in the respective units. Another question is how the legal structure may affect the arrangement of activities over time. The greater cost of integration of legally separate entities may imply that greater autonomy is more likely to follow, which future research may want to investigate.

Moreover, it would be useful for the field of organizational design to better understand when potential structural changes in divisions and legal entities trigger in turn a reorganization of leadership responsibilities. The legal structure may change much more slowly than the other two types, because of regulatory and other legal reasons. Nevertheless, the legal structure can play an essential role in how the organization lays out its strategic priorities, is internally managed, and evaluates its performance. At least, these appear to be the main reasons of notable reorganization that lead to an overhaul in legal structure. Recent examples include the already mentioned case of Google’s legal reorganization into contained group subsidiaries under the Alphabet umbrella, Facebook’s legal reorganization into the corporation Meta (Zuckerberg 2021 ), and Lego’s reorganization into the Lego Brand Group (LEGO Group 2016 ). The question remains whether the legal reorganization is a means to enable better top management and divisional structures or whether the top management structure, for example, motivated such legal changes for better alignment.

Finally, a completely novel question that acknowledges the multifaceted perspectives of organizational structure emerges. What are the performance, innovation, and strategic change consequences for organizations when these different perspectives are aligned or misaligned? Are there specific “archetypes” organizational structures along these dimensions?

Implications

It is important to stress that in some cases it may be necessary to draw upon two or all three to gain a more holistic picture of organizational structure and important nuances that may be highly specific to a particular organization. Whereas the arrangement of activities provides an overview of distinct operating units, such as divisions and subunits, this perspective alone does not capture complex interrelationships with respect to who reports to whom. This becomes most critical in cases of a matrix organization, where, for example, a segment is guided by a product goal as well as some geographical goals.

Moreover, a comparison of some of the organizational structure characteristics between Citigroup and Ford demonstrates how important, potentially strategy-influencing differences exist when consulting all three perspectives. For example, the fact that Ford’s executive team is in part made up of executives who represent a specific legal entity, which is its own reporting segment, suggests that legal structure, decision-making and value creation for certain parts of the organization go hand in hand. In contrast, Citigroup’s legal structure bears little to no resemblance to its operational structure. This may suggest that in Citigroup’s case legal entities play a very different role for organizational design purposes, such as containing legal regulatory requirements and legal containment of liability, whereas its management of value creating activities and decision-making responsibilities is guided across these legal boundaries. Concluding that the legal structure is a reflection of operational and strategic design may be somewhat misdirected with respect to product-market operations but more reflective of risk and geographical profiles in Citigroup’s case. Future research is encouraged to explore such differences in more detail.

Limitations

Before concluding this point of view paper, it is important to acknowledge that there are other important attributes of organizational design and structure that should be considered. For example, the leadership perspective of structure may be extended or complemented by considering the structure of corporate governance and its effects on organizational changes (Castañer and Kavadis 2013 ; Goranova et al. 2007 ). Moreover, the arrangement of activities into departments, units, and divisions determines the formal structure of the organization. Employees who belong to the same department (and work on the same task) often work in the same physical location and, therefore, are more likely to interact (including outside their formal task) and form (informal) networks with those close to them (Clement and Puranam 2018 ). As such, the structure of tasks can affect the emergence of networks in the organization. Organizational changes to the arrangement of activities may consequently conflict with the informal structure that has formed over time (Gulati and Puranam 2009 ). Informal networks in the organization may, therefore, constitute another “measure” of structure, but this paper takes the perspective that networks are a more likely to be a consequence of organizational structure (albeit one that may affect future structures).

Finally, organizational design can exceed a focal firm’s boundaries. Partnerships, such as alliances, joint ventures, and meta-organizations (Gulati et al. 2012 ), pose additional challenges in determining the actual structure of an organization. Future research is advised to study how different dimensions of organizational structure extend to and impact such boundary-spanning multi-organization designs.

The divergence in prior literature with respect to conceptualizing and operationalizing organizational structure reveals that this construct has more facets to it than sometimes acknowledged. Studying the alignment and divergence of these three characteristics of structure within organizations has potential to qualify and complement prior theories and generate new insights with respect to nuances of organizational design that we may have overlooked in prior work. It is important to consider that focusing only on one of these dimensions at a time for studying structure can indeed be sufficient. However, the field of organizational design may wish to be more concise in which perspective is chosen and why, when building, testing, and extending theory. Highlighting what is not measured following a particular perspective can already enrich our understanding of the role of organizational structure in novel and impactful ways.

Data availability

Data used in this manuscript are publicly accessible through regulatory filings and company Investor Relations websites.

Albert D (2018) Organizational module design and architectural inertia: evidence from structural recombination of business divisions. Organ Sci 29(5):890–911

Article Google Scholar

Argyres N (1996) Capabilities, technological diversification and divisionalization. Strateg Manag J 17(5):395–410

Arora A, Belenzon S, Rios LA (2014) Make, buy, organize: the interplay between research, external knowledge, and firm structure. Strateg Manag J 35(3):317–337

Bethel JE, Liebeskind JP (1998) Diversification and the legal organization of the firm. Organ Sci 9(1):49–67

Bidwell MJ (2012) Politics and firm boundaries: how organizational structure, group interests, and resources affect outsourcing. Organ Sci 23(6):1622–1642

Bouquet C, Birkinshaw J (2008) Managing power in the multinational corporation: How low-power actors gain influence. J Manage 34:477–508

Burgelman RA (1983) A model of the interaction of strategic behavior, corporate context, and the concept of strategy. Acad Manage Rev 8(1):61–70

Castañer X, Kavadis N (2013) Does good governance prevent bad strategy? A study of corporate governance, financial diversification, and value creation by French corporations, 2000–2006. Strateg Manag J 34(7):863–876

Chandler AD (1962) Strategy and structure. MIT Press, Cambridge

Google Scholar

Chandler AD Jr (1991) The functions of the HQ unit in the multibusiness firm. Strateg Manag J 12(S2):31–50

Citigroup Inc. Form 10-K 2022 Annual report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Clement J, Puranam P (2018) Searching for structure: formal organization design as a guide to network evolution. Manag Sci 64(8):3879–3895

Csaszar FA (2012) Organizational structure as a determinant of performance: evidence from mutual funds. Strateg Manag J 33(6):611–632

Cyert RM, March JG (1963) A behavioral theory of the firm. Oxford: Blackwell

Eklund JC (2022) The knowledge-incentive tradeoff: understanding the relationship between research and development decentralization and innovation. Strateg Manag J 43(12):2478–2509

Ford Motor Company Exhibit 21 in Form 10-K 2022 Annual report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Ford Motor Company Form 10-Q (Q2) Quarterly report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Foss NJ (1997) On the rationales of corporate headquarters. Ind Corp Change 6(2):313–338

Galbraith JR (1974) Organization design: an information processing view. Interfaces 4(3):28–36

Girod SJG, Whittington R (2015) Change escalation processes and complex adaptive systems: from incremental reconfigurations to discontinuous restructuring. Organ Sci 26(5):1520–1535

Goranova M, Alessandri TM, Brandes P, Dharwadkar R (2007) Managerial ownership and corporate diversification: a longitudinal view. Strateg Manag J 28(3):211–225

Guadalupe M, Li H, Wulf J (2013) Who lives in the C-Suite? Organizational structure and the division of labor in top management. Manag Sci 60(4):824–844

Gulati R, Puranam P (2009) Renewal through reorganization: the value of inconsistencies between formal and informal organization. Organ Sci 20(2):422–440

Gulati R, Puranam P, Tushman M (2012) Meta-organization design: rethinking design in interorganizational and community contexts. Strateg Manag J 33(6):571–586

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper echelons - the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad Manage Rev 9(2):193–206

Hambrick DC, Humphrey SE, Gupta A (2015) Structural interdependence within top management teams: a key moderator of upper echelons predictions. Strateg Manag J 36(3):449–461

Joseph J, Gaba V (2020) Organizational structure, information processing, and decision-making: a retrospective and road map for research. Acad Manag Ann 14(1):267–302

Karim S (2006) Modularity in organizational structure: the reconfiguration of internally developed and acquired business units. Strateg Manag J 27(9):799–823

Karim S, Kaul A (2014) Structural recombination and innovation: unlocking intraorganizational knowledge synergy through structural change. Organ Sci 26(2):439–455

Karim S, Williams C (2012) Structural knowledge: how executive experience with structural composition affects intrafirm mobility and unit reconfiguration. Strateg Manag J 33(6):681–709

Keum DD (2023) Managerial political power and the reallocation of resources in the internal capital market. Strateg Manag J 44(2):369–414

Keum DD, See KE (2017) The influence of hierarchy on idea generation and selection in the innovation process. Organ Sci 28(4):653–669

Lawrence PR, Lorsch JW (1967) Organization and environment: managing differentiation and integration. Harvard University Press, Boston

Lee S (2022) The myth of the flat start-up: reconsidering the organizational structure of start-ups. Strateg Manag J 43(1):58–92

LEGO Group (2016) New structure for active family ownership of the LEGO® brand. LEGO.com . Retrieved (July 28, 2023), https://www.lego.com/en-us/aboutus/news/2019/october/new-lego-brand-group-entity

Mintzberg H (1979) The structuring of organizations: a synthesis of research. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Monteiro LF, Arvidsson N, Birkinshaw J (2008) Knowledge flows within multinational corporations: explaining subsidiary isolation and its performance implications. Organ Sci 19(1):90–107

Pfeffer J (1981) Power in organizations. Pitman Publishing Inc., Marshfield

Pfeffer J, Salancik GR (1974) Organizational decision making as a political process - case of a university budget. Adm Sci Q 19(2):135–151

Puranam P (2018) The microstructure of organizations. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Book Google Scholar

Puranam P, Vanneste B (2016) Corporate strategy: tools for analysis and decision-making. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Raveendran M (2020) Seeds of change: how current structure shapes the type and timing of reorganizations. Strateg Manag J 41(1):27–54

Reuters (2014) UBS launches share-for-share exchange for new holding company. Reuters (September 29) https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-ubs-ag-holding-company-idUKKCN0HO0AH20140929

Zenger T (2015) Why Google Became Alphabet. Harvard Business Review (August 11) https://hbr.org/2015/08/why-google-became-alphabet

Zhou YM (2013) Designing for complexity: using divisions and hierarchy to manage complex tasks. Organ Sci 23:339–355

Article ADS Google Scholar

Zuckerberg M (2021) Founder’s Letter, 2021. Meta.

Download references

Acknowledgements

I appreciate the helpful comments and guidance provided by the handling editor-in-chief Marlo Raveendran and two anonymous reviewers. I also would like to thank all three editors-in-chief for supporting the publication of this point of view manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

LeBow College of Business, Drexel University, Philadelphia, USA

Daniel Albert

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel Albert .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Albert, D. What do you mean by organizational structure? Acknowledging and harmonizing differences and commonalities in three prominent perspectives. J Org Design 13 , 1–11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41469-023-00152-y

Download citation

Received : 30 March 2023

Accepted : 12 September 2023

Published : 11 October 2023

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41469-023-00152-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Organizational structure

- Operationalization

- Decision-making

- Legal entities

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Public Health

Organisational structures and processes for health and well-being: insights from work integration social enterprise

Andrew joyce.

1 Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology, Mail H25, Cnr John and Wakefield Streets, PO Box 218, Hawthorn, VIC 3122 Australia

Batool Moussa

Aurora elmes, perri campbell, roksolana suchowerska, fiona buick.

2 School of Business, University of New South Wales, Northcott Drive, Canberra, ACT 2600 Australia

Jo Barraket

3 Melbourne Social Equity Institute, University of Melbourne, Grattan Street, Parkville, VIC 3010 Australia

Gemma Carey

4 Centre for Social Impact, University of New South Wales, UNSW Sydney, 704, Level 7, Science Engineering Building, Sydney, NSW 2052 Australia

Associated Data

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available in raw form as part of the ethics requirements due to the small case sample size. Further information on the case studies are available at this link: https://www.csi.edu.au/research/project/improving-health-equity-young-people-role-social-enterprise/

Previous research on employee well-being for those who have experienced social and economic disadvantage and those with previous or existing mental health conditions has focused mainly on programmatic interventions. The purpose of this research was to examine how organisational structures and processes (such as policies and culture) influence well-being of employees from these types of backgrounds.

A case study ethnographic approach which included in-depth qualitative analysis of 93 semi-structured interviews of employees, staff, and managers, together with participant observation of four social enterprises employing young people.

The data revealed that young people were provided a combination of training, varied work tasks, psychosocial support, and encouragement to cultivate relationships among peers and management staff. This was enabled through the following elements: structure and space; funding, finance and industry orientation; organisational culture; policy and process; and fostering local service networks . . The findings further illustrate how organisational structures at these workplaces promoted an inclusive workplace environment in which participants self-reported a decrease in anxiety and depression, increased self-esteem, increased self-confidence and increased physical activity.

Conclusions

Replicating these types of organisational structures, processes, and culture requires consideration of complex systems perspectives on implementation fidelity which has implications for policy, practice and future research.

Introduction

Employment is considered one of the key determinants of health and well-being [ 1 ] and relates to other influential social conditions such as education, income, social status and material circumstances. Unemployment is associated with poverty, social isolation and worsened mental health outcomes [ 2 , 3 ] and exclusion from decent employment limits social participation and opportunities for skill development [ 4 ], which has multiple negative effects on the economic and health status of individuals and communities [ 5 ]. One potential avenue for inclusive employment opportunities is social enterprise (SE) – or businesses that trade to fulfil a social mission [ 6 ]. Work integration social enterprises (or WISEs) have a primary social purpose of creating meaningful employment opportunities or pathways to employment for people who are disadvantaged in the open labour market [ 7 ], particularly for people with disabilities. SE scholars have theorized that WISEs may provide a pathway to address the social and economic inequities that contribute to illness, through mechanisms such as creating employment, and increasing peoples’ access to economic and social resources [ 7 – 9 ].

A current gap in this literature is an understanding of the specific organizational processes, structures, and culture of the workplace environment that either support or hinder health and well-being [ 10 ]. Some scholars have argued that workplaces that are inclusive – that is, those that enable all employees to feel a sense of belonging while still being confident to express individual identity related to ethnicity, gender, sexuality and other domains – support health and well-being [ 11 ]. However, there is a lack of empirical research into whether young people from diverse backgrounds and those with diagnosed mental health conditions are able to feel a sense of connection and belonging in the workplace and what impact this has on their health and well-being. Even social enterprises, which are explicitly concerned with promoting inclusivity and social benefit, are only just starting to receive attention from researchers on how they promote health and wellbeing among stakeholders [ 10 ].

The aim of this research was to address these gaps in the literature by analyzing the organisational strategies that WISEs utilise to support the health and well-being of young people that have previously been excluded from the labour market. The focus on young people was due to their higher rates of unemployment and underemployment relative to general population [ 12 ], and where there is an opportunity to address risk factors which can have a positive impact on current and future mental health [ 13 ]. The main research question explored in this paper was: What are the organizational structures, processes, and culture that enable WISE to employ young people who have experienced economic and social disadvantage and how do these organisational elements impact on the health and well-being of these young people? This paper was part of a larger study examining how social enterprises redress social determinants of health inequities among young people.

The paper will outline previous research on the health benefits of employment and where there are gaps in relation to understanding how particular organisational strategies either promote or hinder positive well-being among employees. Through in-depth qualitative analysis of 93 semi-structured interviews and field note observations, the findings show how employees perceived a number of positive changes to their mental and physical health which they attributed to certain organisational strategies related to processes, structures, and culture. The paper will also present challenges for future research and practice on how to further develop and test the findings presented in this paper.

Employment as a Social Determinant of Health

While employment is considered a social determinant of health [ 14 ], there are mixed findings on whether employment itself has a positive effect on mental health [ 15 ]. This relationship between employment and mental health varies according to a number of factors such as job security, the quality of the work, the level of control of the work tasks, and whether it is meeting the individual’s personal needs [ 16 , 17 ]. Current social determinants of health models do not address this level of complexity and often present employment itself as a positive contributor to well-being wherein the reality is more nuanced [ 14 , 18 ]. The quality and nature of the employment is particularly important for young people (typically, classified as 15–24 years) as risk and protective factors for mental health at this point in someone’s life can have substantial impact on future health and well-being [ 19 ].

While the research is still emerging, there is some work to suggest that social enterprises are able to provide employment and training opportunities for people previously excluded from the labour market and that there is some benefit for their mental health and social capital [ 20 , 21 ]. There has been little research examining the impacts for young people although some studies have found that social enterprise interventions can have a positive effect on the mental health of young people [ 22 , 23 ]. What is currently lacking from this research is the specific organisational factors influencing these health gains [ 10 , 24 , 25 ] and the voices of young people themselves with the perspectives of social enterprise managers and funders currently dominating the research base [ 26 , 27 ]. One of the proposed mechanisms for how social enterprises enable positive mental health of employees is through providing an inclusive workplace environment [ 7 – 9 ].

Organisational Structures, and Health and Well-Being of Employees

Work integration social enterprises provide a useful organisational type to explore how organisations can, through the design of organisational structure, processes and culture, promote the health and wellbeing of people from disadvantaged backgrounds [ 7 ]. Social enterprises are organisations where one of the main goals is promoting social or environmental benefit while ensuring the business is profitable [ 28 ]. A systematic review conducted by Roy et al. [ 9 ] found some (albeit limited) evidence from Australia, Canada, Hong Kong and the USA of social enterprise activity positively impacting on health and well-being. Specifically, involvement in social enterprise improved people’s mental health, self-reliance/esteem and health behaviours, reduced stigmatization and built social capital. Scholars are starting to explore the organisational features of social enterprise that enable them to achieve these health and wellbeing outcomes [ 10 , 29 , 30 ].

Suchowerska et al. [ 10 ] theorise that organisations impact health equity and well-being through two distinct processes. Transformational processes, which are shaped by organisations’ leadership, culture and mission, put pressure on social structures and institutions that entrench health inequities. Transactional processes, which are shaped by the relational, structural and policy mechanisms of an organisation, can more rapidly shift the quality of life, wellbeing and self-efficacy of individuals within the organisation. This whole-of-organisation perspective contrasts with prior research that has tended to focus on how specific programs within organisations impact workplace inclusion and in turn, health equity [ 10 ].

The aims of this research were to examine in further depth how the structure, operation, and culture of an organization itself influences health and well-being outcomes. In doing so the intention is to illuminate the core features of good WISE practice that can explain how a WISE achieves social and health impact [ 31 ] and to offer suggestions for future workplace well-being practice and policy based on these findings. As both a topic that has received little research focus from an organizational perspective and a participant group that is more likely to feel disenfranchised, qualitative research was deemed important for giving ‘voice’ to this group and exploring organizational processes and strategies in more depth [ 32 – 34 ]. The research question that guided this study was: What are the organizational structures, processes, and culture that enable WISE to employ young people who have experienced economic and social disadvantage and how do they impact on their health and well-being?

The data presented in this paper is from a three-year research project funded by the Australian Research Council through its Linkage Scheme. The project focused on the health and well-being impacts of Australian WISE on young people aged 15 to 24 who have experienced some form of disadvantage related to education and employment opportunities [ 13 , 35 ]. This age group experiences higher rates of unemployment and lower rates of participation in the employment market relative to general population averages [ 36 ].

Case study research design

This study required exploration of specific features of workplace design and structure and how these features were experienced by young people and the perceived impact on their health and well-being. In order to understand and explore this particular type of workplace structure, it was important to examine it in situ and understand critical contextual factors, social processes and dynamics [ 37 , 38 ]. Thus, a case study approach was important in order to facilitate understanding and to provide a boundary around the subject of investigation [ 37 ].

Case studies were selected based on a paradigmatic case sampling approach [ 39 ], which seeks to include examples that demonstrate prototypical characteristics of the phenomena in question. The paradigm being explored is the interaction between SE operations and employment experience and health outcomes for young people [ 14 ]. The four WISEs selected were located in the Australian states of New South Wales (NSW) or Victoria and operated within or into areas experiencing locational disadvantage, as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics [ 40 ] SEIFA index. These States were selected because they have the highest concentration of SEs in Australia [ 6 ]. Each of the WISEs had been in operation longer than five years and were well-established in respect of organizational culture, structure and processes. The location and industry of each case study were:

- Case A: Inner-Metropolitan Melbourne, Hospitality

- Case B: Inner-South Sydney, Information technology and electronics

- Case C: Greater Melbourne, Construction

- Case D: South Coast New South Wales, Farming and Waste management

Young people participating in training or working at the WISE had diverse backgrounds. Three of the organisations had successfully engaged refugees and immigrants in their programs, and all organisations engaged young people with mental health issues. One of the WISEs recruited participants directly from local schools, while the others also included young people who had exited school. Given that the research problem being examined requires rich analysis of organizational factors and their effects, ethnographic data collection methods were used. Ethnographic research enables researchers to engage with participants in their natural environments and, in line with a realist approach, understand what works for whom under what conditions. This approach can develop rich insights through ‘thick description’ [ 41 ] and help reveal both intended and unintended effects of practice [ 42 ]. This is consistent with both public health and institutional scholars’ calls for understanding organizational effects at the ‘coalface’ of practice [ 42 , 43 ] and for more qualitative research to explore in-depth how organizational processes and dynamics are experienced by employees [ 32 ].

Thus a range of methods consistent with an ethnographic approach were undertaken, including: initial workshops with staff and directors on their perception of organizational processes and outcomes; 93 semi-structured interviews with young people, WISE managers, WISE funding and external organisations which were the key component of the data collection [ 44 ]; up to three weeks of participant observation within each WISE; collation of organizational documents; and concluding engagement workshops to share and make sense of the findings. To ensure qualitative research rigor, each of the steps in the process of sampling, data collection processes, and sequencing of analysis, are explained according to best practice guidelines and recommendations [ 33 ]. All participants provided informed consent and the study was approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of Swinburne University of Technology.

Data collection

Preliminary workshops.

The research team facilitated a 90-min Theory of Change workshop with staff and managers at each social enterprise. The purpose of the workshops was: (a) to identify how case study organizations delivered social impact and value by reviewing their organizational Theory of Change; and (b) to revise the organizations’ Theory of Change to guide measurement of social impact, test assumptions and support strategic planning activities. These workshops provided WISE staff and managers (young people did not participate in these workshops) with the opportunity to reflect on their understanding of organisational aims and goals, and also helped researchers to refine research questions to the specific case study. The workshops were recorded and minutes taken. They helped to shape the specific interview schedules for participant groups and shaped the field note observations but they were not included as part of the data that was coded.

Semi-structured interviews

Ninety-three semi-structured interviews were undertaken with participants to understand if, and how, the WISE workplace environment supported their health and well-being. Semi-structured interviews were used to ensure consistency across interviews and adherence to areas of interest while allowing sufficient flexibility for the participant to respond [ 45 ]. The questions for young people included overall experience, what skills they developed, what they thought of the different roles, what they thought of the support, whether they noticed any benefits to their health and well-being or any negative outcomes, and how they experienced the social environment of the workplace. The interview questions for staff and other stakeholders were similar, although they were asked to reflect on their perceptions of the benefits and challenges for young people, the extent to which organizational structures and processes supported these young people, and areas requiring organizational change and improvement. Interviews were audio recorded.

All members of each case study organization – young people who received services, managers and employees of the WISE – were invited to participate in the study via a group email sent by internal contacts. Thus, a convenience sample was used, as participants were those who volunteered to take part in the study. Additional participants were identified using a snowball sampling technique where, at the end of each interview, participants were asked to recommend other potential participants [ 46 ]. Overall, the sample comprised 27 young people, 12 managers, 7 partners, 19 staff, 15 representatives from external organizations and funders, 7 board members, and 6 executive staff.

Participant observation

Another key data collection strategy was participant observation within four case study organizations, which lasted an average of 13 business days for each case study organization. Due to the nature of on-site activities, researchers were limited to only 3.5 days of participant observation in one of the case studies. The researchers observed a range of activities, including training/ work programs and board meetings, and recorded notes of their experiences. For each organization, the same researcher was assigned for all of the observation period. Detailed field notes were written at the conclusion of each day in the form of a diary record focusing on organisational structures and processes that were engaging young people (or not engaging as the case may be) and any observations on the social relationships between young people and between young people and staff and managers (that is both bonding and bridging social capital) [ 44 , 47 ]. The field notes focused on: the roles of staff, the use of space, the activities undertaken and experiences of participants, and the atmosphere of the WISE. The notes provided a record of: key staff members roles, the spatial layout of the WISE, the ways in which staff and participants interacted with the spaces and when, the use of spaces and objects for training/work/other purposes, photographs of the WISE (rooms used, training tools), researcher interactions with staff members and participants, key events of the day as described by staff and participants, staff and participants responses to training and work throughout the day, researcher reflections on the atmosphere of the WISE and cultural norms of the WISE.

Data analysis

Interview and field note data was coded in NVivo 11 using open, axial and selective coding [ 48 ]. All the data sources were included in this coding process inclusive of interview data, workshop data, and field notes. To increase confidence that the findings accurately reflected the views of participants, triangulation approaches were used: methods and data source triangulation (using more than one method and data source); and researcher triangulation (two or more researchers involved in coding) [ 49 ].

Authors PC and RS undertook the process of an inductive open coding which involved the following steps: reading through the data line-by-line and segregating into parts; looking for areas of similarity and difference between the parts of the data; and creating thematic groups based on the data [ 50 ]. One of the researchers had been involved in field note observations and the other researcher had not been involved in observation, this helped to balance intimate knowledge of the context and some research distance [ 44 , 47 ]. These themes were then discussed as a research team and agreement reached on the preliminary set of themes. The next step was to conduct axial coding where different thematic segments were clustered together by authors PC and RS and broader themes related to the research questions were developed. This corresponds to a second order level of analysis from Gioia et al.’s [ 44 ] methodology approach the aim of which was to explore the organizational structures and processes that were in operation.

These themes were then tested through a number of supplementary checks to strengthen the credibility and integrity of the findings [ 33 ]. This involved a second round of 90 min workshops with staff and managers of each of the participating WISEs where the emergent findings were presented, and themes discussed. The purpose of these workshops was to provide organizations with insight into early findings and seek feedback about how to direct future analysis. A series of case study reports for each organization were produced as part of this process and a range of graphic presentations to illustrate the findings which were discussed with WISE members.

Lastly, a selective coding process [ 48 ], took place with authors AJ and PC coding the data on how the themes/concepts related to organizational strategies (developed in state 2) were related to perceived health and well-being outcomes. Concepts related to how organizational features might impact on health and well-being outcomes described in a previous theoretical paper guided this analysis [ 10 ]. Following an abductive research approach [ 51 ], the analysis focused on the perceptions of participants in how organisational processes and structures were influencing health and well-being outcomes.

The findings are structured according to the research question of the organizational features that enabled WISE to impact on health and well-being. The data analysis uncovered the following organizational features as being important in influencing health and well-being: structure and space; funding, finance and industry orientation; organisational culture; policy and process; and fostering local service networks.

Structure and space

There were a range of organisational structures through which psychosocial support and skill development occurred. The youth programs team in one of the cases provided an organisational structure for psychosocial support. In other cases where a team itself was not in place, this support was provided differently through policies and processes which will be covered later.

Participants across all of the case organizations reported a deliberate strategy of extending the skills of the young people and having them confront new situations – including developing new work skills, periodically changing work teams and venues, and engaging in diverse customer-facing roles – to increase their self-confidence. Being able to provide a range of different roles at different sites was considered important for their skill development and self-esteem. Young people and staff felt respected and valued within the workplace and training environment:

… I was very scared, so when I start with [WISE] they were very supportive, they were very helpful, so I feel secure, I feel like – how to say sometime when I need support … especially for something work here at first I didn’t know much how to do so if I did something wrong so they … explain to me clearly. So they show me not just explain to me, they show me how to do so that’s how I started to feel confident and so I start to improve other – like I know how to do other things and also after that when I apply for a job… so that’s how I start to build my confidence. (Case D, Young person 10) I think the biggest thing is when we finish the first containers and I’m standing there, ‘We can do it actually! We have done all of this!’ So I was proud. I can do it! So it gives me confidence. (Case C, Young Person 4)

The constant recognition and praise for developing skills was seen as critical for the development of self-confidence and self-esteem.

The spatial design of the case WISEs impacted positively on young people’s sense of well-being. Each of the WISEs used space differently to cater for the different mental health needs of the young people. There was one case study that had a significant amount of green space which was noted as beneficial for well-being:

When I’m at home the environment is a lot different. It’s a lot more stressful, a lot more work. Everything’s “Go, go, go, go, go.” When I come here for volunteer work it was come here, chill, do work. It’s quiet. You hear birds. You’re always surrounded by nature sort of thing, so it’s just awesome. (Case D, Young Person 6)

All case organizations included a number of hidden areas and lesser-used rooms which can help to reduce stress levels by providing a place for quiet and solitude when needed. Designated areas, like break rooms or games rooms created a more informal space for young people to interact. There was a sense that socializing was a key element of the work and education environment and this was actively encouraged as a means to build self confidence in young people. The sense of belonging and having a community to connect with was seen as beneficial for autistic people or those with previous experience of social isolation; and also, for people experiencing depression, anxiety, and general loneliness. These quotes reflected a common sentiment across the different organizations and young people who were interviewed:

Something tragic happened back in 2013 and that kind of like I was going through depression and stuff over it, so that set me back a lot with career things … I went into a bad depression … some places I’ve worked I’ve had like the best boss ever, but then some places I've had like people I just don’t want to work for and help out. But here is like, it's definitely up there. I haven’t met a single person here that I've not liked or gotten along with yet. Everyone is great and nice. They’ll answer any question you have. They won’t make you feel bad for asking questions. Just really supportive and motivated to help you and learn. (Case B, Young person 9) I suffer with severe anxiety, and I do get a little bit of deep depression. But since being here, that’s gone. I think it’s amazing. I’ve come here, and I’ve just got this role now where I want to be at work, I’m happy to be at work… I feel supported here. I can come here and I can have my little chats to people. (Case D, Young person 1)

Feeling that sense of connection with other people was one of the key factors that people felt was responsible for improving their mental health and reducing feelings of anxiety and depression.

Finance, Funding, and Industry Orientation

Providing these work and training opportunities within a flexible environment was made possible through a mix of revenue streams. This included commercial product offerings, internal investment through their parent organisation and/or grant funding through philanthropic and/or government partners. This was seen as constant challenge in operating this type of organizational model:

‘Access to finance is my ongoing challenge always. The challenges of trying to scale these things and getting access to the right type of capital… the market’s just too embryonic to have the things in place that you need to be able to access the capital at the right time’. (Leadership, Case A)

The sustainability of the organizations depended in large part on aligning within an industry supportive of this business type and being commercially competitive. One of the key focuses was aligning the social goals of the WISE with the chosen industry to ensure that there were employment opportunities in that industry in that region for young people. There were some concerns by staff though that the culture and gender norms of the industry in which two of the case studies operated may not be suitable for the young people involved in the WISE.

Interviewer: people write about hospitality as quite a male dominated industry. And this isn't specific for social enterprise but more hospitality in general. What's your take on that? Participants: … I think this is definitely one of the main workplaces where I see a little bit more equal in gender but everywhere else I've worked is I would say 80% male dominated for sure. (Case A, Young Person 11)

It was also noted in one of the case studies that industry norms around smoking was a point of connection between young people and staff which was a concern from a health perspective. As one staff member told us:

… we don’t have an area that separates the students from the staff. So, we all smoke but the thing is, we’ve only got one smoking area so it means that you’re out there having a smoke and all the students are out there having a smoke. (Case D, Program Staff 2)

In addition to the negative impact of smoking, accessible healthy food choices were a challenge in some industries due the location of the workplace. In some industrial settings there were no healthy food options available.

A point of consistency across the case studies was an acknowledgment of diversity was important to the WISEs which maybe atypical of industry norms:

It [Organization] is like a community, because at the first time when we started, the classmate that we had is all from different ethnic groups, like from different communities, different people, like the people who came from - they kicked out of school or they were on drugs and stuff, they’re disabled or something like that. You’re getting involved in a lot sort of people, you know, different sort of people. (Case C, Young Person 8)

There was strong recognition of diversity and as detailed thematically, a strong desire to validate people’s differences. From field notes recorded this was observed through strong visual cues – including posters, staff profiles of visible diversity around the WISEs; use of iconic symbolism – such as pride colours – in workplace design; and purposeful integration of visual, textual and auditory organisational health and safety materials to support participants of all abilities and linguistic diversity. While this was undoubtedly seen as valuable from the perspective of both the staff and young people, a consistent concern was that it created an unrealistic expectation of the realities of ‘normal’ workplaces:

We provide an environment here that is really rare in that people are just supported no matter what their identity is, what their background history. It’s a very supportive environment which in turn has its own unintended consequences down the track when it comes to putting them back out in the real world. (Case A, Leadership)

This highlights the need for broader workplace reform and change to ensure that workplace inclusion becomes more common.

Organisational culture

Organisational culture refers to the shared beliefs and values that influences the relationship interactions and practices within an organisation. It was made abundantly clear in the interviews that this sense of feeling comfortable and being able to be yourself was highly important to the staff and young people in the case organizations. There was a strong focus on people feeling safe to disclose any mental health conditions. In terms of authenticity, people felt comfortable being open about their mental health challenges and felt supported in doing so.

Yeah, and be safe, feel safe and supported and nurtured and know if there’s baggage and many times there are, that can be left at the gate and just come in and have that free open mind and not be judged or accountable for too much, that you would possibly spotlighted for in the community. (Case D, Program Staff 1)

Across the organizations there was a strong culture of mental health awareness and support. Staff challenged the stigma around mental health that many young people encountered in other workplaces and educational settings, with a focus on strengths-based approaches. In one of the WISEs there were specific tasks and workshops delivered on acceptance of differences and inclusivity, in all other cases these themes were observed in the operation and actions of staff. The message that young people encountered in all case studies is that everyone faces different mental health, family, background challenges and this is a place where you can be yourself. This creates a safe environment in which young people can feel supported to participate in group settings where different learning styles and ways of being are normalized. This level of acceptance was fostered throughout the organizations and was made explicit to new participants:

I bring them up and I introduce them to [Name], [Name] what do you do? Right, and particularly the young ladies on [our training program] … their ears prick up. Because they can see this young lady doing all this magnificent high precision soldering and component replacement, and you watch them and you see their eyes stare … I say [Name], what were you doing five, six years ago, and she tells them, she calls herself an alcoholic, whether she was or wasn’t, she had trouble with alcohol and stuff like that. Fought with her mother, didn’t see her father, no job, no prospects, and that’s when the penny drops. (Case B, Manager 2)

This authenticity was valued across the hierarchy of the case organizations. The senior staff were focused on providing a safe environment for young people where they could speak their mind and be open about any challenges they were facing. The most common approach employed was to ‘check in’ regularly:

There’s been times here before where people will say, ‘[Name], are you okay today?’ Like [Leadership staff], last week, she said to me, ‘Are you okay today?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, why’s that?’ And she’s like, ‘You’re not your happy, bubbly, like you want to be here - not saying you don’t want to be here, but are you sure you’re okay?’ … She definitely noticed [a difference]. And I’m like, ‘Yeah, I seem okay. I’m just a little – [Staff member] is leaving, and I’m just thinking a lot.’ She’s like, ‘Yeah, you’re just not your bright, bubbly’ - and I’m like, ‘Sorry. I don’t mean to be like that.’ And it really got me out of it. (Case D, Young person 1)

The young people interviewed indicated they felt confident to express their mental health challenges and felt secure in the approach taken by staff. There was acknowledgement of the empathy being provided and the young people clearly felt a strong sense of connection and safety in the workplace. This level of collegiality and acceptance of the young people was something the young people really valued.

It keeps you involved – to get involved with a community or to get involved at work, teamwork or in visually working. (Case C , Young person 8) Yeah, just for them to have our backs all the time, I feel really supported. (Case A , Young person 3)