- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Design

Definition:

Research design refers to the overall strategy or plan for conducting a research study. It outlines the methods and procedures that will be used to collect and analyze data, as well as the goals and objectives of the study. Research design is important because it guides the entire research process and ensures that the study is conducted in a systematic and rigorous manner.

Types of Research Design

Types of Research Design are as follows:

Descriptive Research Design

This type of research design is used to describe a phenomenon or situation. It involves collecting data through surveys, questionnaires, interviews, and observations. The aim of descriptive research is to provide an accurate and detailed portrayal of a particular group, event, or situation. It can be useful in identifying patterns, trends, and relationships in the data.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational research design is used to determine if there is a relationship between two or more variables. This type of research design involves collecting data from participants and analyzing the relationship between the variables using statistical methods. The aim of correlational research is to identify the strength and direction of the relationship between the variables.

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to investigate cause-and-effect relationships between variables. This type of research design involves manipulating one variable and measuring the effect on another variable. It usually involves randomly assigning participants to groups and manipulating an independent variable to determine its effect on a dependent variable. The aim of experimental research is to establish causality.

Quasi-experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is similar to experimental research design, but it lacks one or more of the features of a true experiment. For example, there may not be random assignment to groups or a control group. This type of research design is used when it is not feasible or ethical to conduct a true experiment.

Case Study Research Design

Case study research design is used to investigate a single case or a small number of cases in depth. It involves collecting data through various methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. The aim of case study research is to provide an in-depth understanding of a particular case or situation.

Longitudinal Research Design

Longitudinal research design is used to study changes in a particular phenomenon over time. It involves collecting data at multiple time points and analyzing the changes that occur. The aim of longitudinal research is to provide insights into the development, growth, or decline of a particular phenomenon over time.

Structure of Research Design

The format of a research design typically includes the following sections:

- Introduction : This section provides an overview of the research problem, the research questions, and the importance of the study. It also includes a brief literature review that summarizes previous research on the topic and identifies gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Research Questions or Hypotheses: This section identifies the specific research questions or hypotheses that the study will address. These questions should be clear, specific, and testable.

- Research Methods : This section describes the methods that will be used to collect and analyze data. It includes details about the study design, the sampling strategy, the data collection instruments, and the data analysis techniques.

- Data Collection: This section describes how the data will be collected, including the sample size, data collection procedures, and any ethical considerations.

- Data Analysis: This section describes how the data will be analyzed, including the statistical techniques that will be used to test the research questions or hypotheses.

- Results : This section presents the findings of the study, including descriptive statistics and statistical tests.

- Discussion and Conclusion : This section summarizes the key findings of the study, interprets the results, and discusses the implications of the findings. It also includes recommendations for future research.

- References : This section lists the sources cited in the research design.

Example of Research Design

An Example of Research Design could be:

Research question: Does the use of social media affect the academic performance of high school students?

Research design:

- Research approach : The research approach will be quantitative as it involves collecting numerical data to test the hypothesis.

- Research design : The research design will be a quasi-experimental design, with a pretest-posttest control group design.

- Sample : The sample will be 200 high school students from two schools, with 100 students in the experimental group and 100 students in the control group.

- Data collection : The data will be collected through surveys administered to the students at the beginning and end of the academic year. The surveys will include questions about their social media usage and academic performance.

- Data analysis : The data collected will be analyzed using statistical software. The mean scores of the experimental and control groups will be compared to determine whether there is a significant difference in academic performance between the two groups.

- Limitations : The limitations of the study will be acknowledged, including the fact that social media usage can vary greatly among individuals, and the study only focuses on two schools, which may not be representative of the entire population.

- Ethical considerations: Ethical considerations will be taken into account, such as obtaining informed consent from the participants and ensuring their anonymity and confidentiality.

How to Write Research Design

Writing a research design involves planning and outlining the methodology and approach that will be used to answer a research question or hypothesis. Here are some steps to help you write a research design:

- Define the research question or hypothesis : Before beginning your research design, you should clearly define your research question or hypothesis. This will guide your research design and help you select appropriate methods.

- Select a research design: There are many different research designs to choose from, including experimental, survey, case study, and qualitative designs. Choose a design that best fits your research question and objectives.

- Develop a sampling plan : If your research involves collecting data from a sample, you will need to develop a sampling plan. This should outline how you will select participants and how many participants you will include.

- Define variables: Clearly define the variables you will be measuring or manipulating in your study. This will help ensure that your results are meaningful and relevant to your research question.

- Choose data collection methods : Decide on the data collection methods you will use to gather information. This may include surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, or secondary data sources.

- Create a data analysis plan: Develop a plan for analyzing your data, including the statistical or qualitative techniques you will use.

- Consider ethical concerns : Finally, be sure to consider any ethical concerns related to your research, such as participant confidentiality or potential harm.

When to Write Research Design

Research design should be written before conducting any research study. It is an important planning phase that outlines the research methodology, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques that will be used to investigate a research question or problem. The research design helps to ensure that the research is conducted in a systematic and logical manner, and that the data collected is relevant and reliable.

Ideally, the research design should be developed as early as possible in the research process, before any data is collected. This allows the researcher to carefully consider the research question, identify the most appropriate research methodology, and plan the data collection and analysis procedures in advance. By doing so, the research can be conducted in a more efficient and effective manner, and the results are more likely to be valid and reliable.

Purpose of Research Design

The purpose of research design is to plan and structure a research study in a way that enables the researcher to achieve the desired research goals with accuracy, validity, and reliability. Research design is the blueprint or the framework for conducting a study that outlines the methods, procedures, techniques, and tools for data collection and analysis.

Some of the key purposes of research design include:

- Providing a clear and concise plan of action for the research study.

- Ensuring that the research is conducted ethically and with rigor.

- Maximizing the accuracy and reliability of the research findings.

- Minimizing the possibility of errors, biases, or confounding variables.

- Ensuring that the research is feasible, practical, and cost-effective.

- Determining the appropriate research methodology to answer the research question(s).

- Identifying the sample size, sampling method, and data collection techniques.

- Determining the data analysis method and statistical tests to be used.

- Facilitating the replication of the study by other researchers.

- Enhancing the validity and generalizability of the research findings.

Applications of Research Design

There are numerous applications of research design in various fields, some of which are:

- Social sciences: In fields such as psychology, sociology, and anthropology, research design is used to investigate human behavior and social phenomena. Researchers use various research designs, such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and correlational designs, to study different aspects of social behavior.

- Education : Research design is essential in the field of education to investigate the effectiveness of different teaching methods and learning strategies. Researchers use various designs such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and case study designs to understand how students learn and how to improve teaching practices.

- Health sciences : In the health sciences, research design is used to investigate the causes, prevention, and treatment of diseases. Researchers use various designs, such as randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies, to study different aspects of health and healthcare.

- Business : Research design is used in the field of business to investigate consumer behavior, marketing strategies, and the impact of different business practices. Researchers use various designs, such as survey research, experimental research, and case studies, to study different aspects of the business world.

- Engineering : In the field of engineering, research design is used to investigate the development and implementation of new technologies. Researchers use various designs, such as experimental research and case studies, to study the effectiveness of new technologies and to identify areas for improvement.

Advantages of Research Design

Here are some advantages of research design:

- Systematic and organized approach : A well-designed research plan ensures that the research is conducted in a systematic and organized manner, which makes it easier to manage and analyze the data.

- Clear objectives: The research design helps to clarify the objectives of the study, which makes it easier to identify the variables that need to be measured, and the methods that need to be used to collect and analyze data.

- Minimizes bias: A well-designed research plan minimizes the chances of bias, by ensuring that the data is collected and analyzed objectively, and that the results are not influenced by the researcher’s personal biases or preferences.

- Efficient use of resources: A well-designed research plan helps to ensure that the resources (time, money, and personnel) are used efficiently and effectively, by focusing on the most important variables and methods.

- Replicability: A well-designed research plan makes it easier for other researchers to replicate the study, which enhances the credibility and reliability of the findings.

- Validity: A well-designed research plan helps to ensure that the findings are valid, by ensuring that the methods used to collect and analyze data are appropriate for the research question.

- Generalizability : A well-designed research plan helps to ensure that the findings can be generalized to other populations, settings, or situations, which increases the external validity of the study.

Research Design Vs Research Methodology

| Research Design | Research Methodology |

|---|---|

| The plan and structure for conducting research that outlines the procedures to be followed to collect and analyze data. | The set of principles, techniques, and tools used to carry out the research plan and achieve research objectives. |

| Describes the overall approach and strategy used to conduct research, including the type of data to be collected, the sources of data, and the methods for collecting and analyzing data. | Refers to the techniques and methods used to gather, analyze and interpret data, including sampling techniques, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques. |

| Helps to ensure that the research is conducted in a systematic, rigorous, and valid way, so that the results are reliable and can be used to make sound conclusions. | Includes a set of procedures and tools that enable researchers to collect and analyze data in a consistent and valid manner, regardless of the research design used. |

| Common research designs include experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational, and descriptive studies. | Common research methodologies include qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods approaches. |

| Determines the overall structure of the research project and sets the stage for the selection of appropriate research methodologies. | Guides the researcher in selecting the most appropriate research methods based on the research question, research design, and other contextual factors. |

| Helps to ensure that the research project is feasible, relevant, and ethical. | Helps to ensure that the data collected is accurate, valid, and reliable, and that the research findings can be interpreted and generalized to the population of interest. |

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and...

Data Analysis – Process, Methods and Types

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Leave a comment x.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

5 Classic Psychology Research Designs

- By Cliff Stamp, BS Psychology, MS Rehabilitation Counseling

- Published November 10, 2019

- Last Updated November 17, 2023

- Read Time 6 mins

Posted November 2019 by Clifton Stamp, B.S. Psychology; M.A. Rehabilitation Counseling, M.A. English; 10 updates since. Reading time: 5 min. Reading level: Grade 11+. Questions on psychology research designs? Email Toni at: [email protected] .

Psychology research is carried out by a variety of methods, all of which are intended to increase the fund of knowledge we have concerning human behavior. Research is a formalized, systematic way of deriving accurate and reproducible results. Research designs are the particular methods and procedures used to generate, collect and analyze information.

Research can be carried out in many different ways, but can broadly be defined as qualitative or quantitative. Quantitative psychological research refers to research that yields outcomes that derive from statistics or mathematical modeling. Quantitative research is centered around testing objective hypotheses . It is based on empiricism and attempts to show the accuracy of a hypothesis.

Qualitative psychological research attempts to understand behavior within its natural context and setting. Qualitative psychological research uses observation, interviews, focus groups and participant observation as its most common methods.

Classic Psychology Research Designs

Research is typically focused on finding a particular answer or answers to a question or problem, logically enough called the research question. A research design is a formalized means of finding answers to a research question. Research designs create a framework for gathering and collecting information in a structured, orderly way. Five of the most common psychology research designs include descriptive, correlational, semi-experimental, experimental, review and meta-analytic designs.

Descriptive Research Designs

- Case study . Case study research involves researchers conduction a close-up look at an individual, a phenomenon, or a group in its real-world naturalistic environment. Case studies are more intrusive than naturalistic observational studies.

- Naturalistic observation . Naturalistic observation , a kind of field research, involves observing research subjects in their own environment, without any introduced external factors. Naturalistic observation has a high degree of external validity .

- Surveys . Everyone has taken a survey at one time or another. Surveys sample a group of individuals that are chosen to be representative of a larger population. Surveys naturally cannot research every individual in a population, thus a great deal of study is conducted to ensure that samples truly represent the populations they’re supposed to describe. Polls about public opinion, market-research surveys, public-health surveys, and government surveys are examples of mass spectrum surveys.

Correlational Research Designs

In correlational research designs, groups are studied and compared, but researchers cannot introduce variables or manipulate independent variables.

- Case-control study . A case-control study is a comparison between two groups, one of which experienced a condition while the other group did not . Case-control studies are retrospective; that is, they observe a situation that has already happened. Two groups exist that are as similar as possible, save that a hypothesized agent affected the case group. This hypothesized agent, condition or singular difference between groups is said to correlate with differences in outcomes.

- Observational study . Observational studies allow researchers to make some inferences from a group sample to an overall population. In an observational study, the independent variable cannot be controlled or modified directly. Consider a study that compares the outcomes of fetal alcohol exposure on the development of psychological disorders. It would be unethical to cause a group of fetuses to be exposed to alcohol in vivo. Thus, two groups of individuals, as alike as possible are compared. The difference is that one group has been selected due to their exposure to alcohol during their fetal development. Researchers are not manipulating the measure of the independent variable, but they are attempting to measure its effect by group to group comparison .

Semi-Experimental Research Design

- Field experiment . A field experiment occurs in the everyday environment of the research subjects. In a field experiment, researchers manipulate an independent variable and measure changes in the tested, dependent variable. Although field experiments generalize extremely well, it’s not possible to eliminate extraneous variables. This can limit the usefulness of any conclusions.

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research is a major component of experimental psychology. In experimental psychology, researchers perform tightly controlled laboratory experiments that eliminate external, erroneous variables. This high level of control allows experimental results to have a high degree of internal validity. Internal validity refers to the degree to which an experiment’s outcomes come from manipulations of the independent variable. On the other hand, highly controlled lab experiments may not generalize to the natural environment, precisely due to the presence of many external variables.

Review Designs and Meta-Analysis

- Literature review . A literature review is a paper examining other experiments or research into a particular subject. Literature reviews examine research published in academic and other scholarly journals. All research starts with a search for research similar, or at least fundamentally similar, to the research question in question.

- Systematic review . A systematic review examines as much published, verified research that matches the researchers’ guidelines for a particular line of research. Systematic review involves multiple and exhaustive literature reviews. After conducting a systematic review of all other research on a topic that meets criteria, psychology researchers conduct a meta-analysis.

- Meta-analyses. Meta-analyses involve complex statistical analysis of former research to answer an overall research question.

Literature reviews and systematic reviews and meta-analyses all work together to provide psychology researchers with a big-picture view of the body of study they are investigating.

Descriptive, Correlational and Experimental Designs

All research may be thought of as having descriptive or inferential value, although there are usually aspects of both present in all research projects. Descriptive research often comes before experimental research, as examining what’s been discovered about a research topic helps guide and refine experimental research, which has a high inferential value.

Descriptive research designs include literature reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses. They’re able to assess and evaluate what the state of a body of knowledge is, but no experimentation is conducted. Correlational designs investigate the strength of the relationship between or among variables. Correlational studies are good for pointing out possible relationships but cannot establish causation, or a cause-and-effect relationship among variables. This leaves experimental designs. which do allow inferences to be made about cause-and-effect. Experimental designs are the most scientifically, mathematically rigorous, but that fine level of control doesn’t always extrapolate well to the world outside the lab.

More Articles of Interest:

- How Do Psychology Researchers Find Funding?

- What Makes Psychology Research Ethical?

- How is the Field of Psychology Changing?

- The Human Connectome Project

- How Is Technology Changing The Study Of Psychology?

- What are the Best TV Shows About Psychology?

Trending now

Understanding Research Design: Its Definition and Importance

Table of Contents

Have you ever wondered how data -tooltip="Professionals studying the mind and behavior">psychologists uncover the mysteries of the human mind? The answer lies within the realm of research design , the scaffold that structures the entire research process. Think of it as the blueprint for a house; without it, the structure would lack foundation and direction. Diving into the world of research design, we quickly find that it’s more than just a plan; it’s the strategic framework that guides the collection, measurement, and analysis of data in psychological research.

What is Research Design?

Research design is often described as a set of guidelines that help researchers navigate the process of conducting a study. It’s the master plan that specifies the methods and procedures for collecting and analyzing the necessary information. This systematic approach is essential for ensuring that the research question is answered as accurately as possible.

Historical Perspectives on Research Design

Renowned scholars like Winner \(1971\) and Myers \(1980\) have likened research design to an architect’s blueprint, emphasizing its critical role in research planning and structure. This comparison underscores the meticulous attention to detail and forethought required in research, similar to that needed when designing a building.

The Components of Research Design

Let’s break down the research design into its core components:

- Plan: This is the overall scheme or the roadmap for the research. It outlines what the study aims to achieve and the steps required to get there.

- Structure: Often referred to as the detailed outline of operations, structure dictates the ‘how’ of the plan. It covers the specifics of data collection, such as surveys or experiments.

- Strategy: Strategy is all about the methods for data gathering and analysis. It involves choosing the appropriate statistical techniques and tools to interpret the collected data meaningfully.

Why is Research Design Important?

Quality research design serves multiple purposes in the study of psychology. It not only facilitates the efficient achievement of research objectives but also provides a way to tackle problems encountered during the research process effectively. Thyer (1993) and Matheson (1970) have both highlighted the importance of a well-structured research design, noting that it is pivotal for the validity and reliability of a study’s findings.

Ensuring Validity and Reliability

Two of the most critical aspects of any research are its validity and reliability:

- Validity refers to the accuracy of the findings or the extent to which the research truly measures what it intends to measure.

- Reliability is about the consistency of the results. A reliable study is one that can be replicated under similar conditions with the same outcomes.

A robust research design guarantees that these aspects are thoroughly considered and addressed.

The Role of Research Design in Psychology

In the field of psychology, where the subject matter can often be abstract and complex, the importance of research design is magnified. Kerlinger \(1986\) asserted that a well-thought-out research design is the foundation upon which the entire inquiry is built. The design influences the choice of research methods, the type of data collected, and the way that data is interpreted.

Types of Research Design in Psychology

Psychological research can take many forms, each with its unique design:

- Experimental Designs : These are used to determine cause-and-effect relationships by manipulating one or more variables while controlling others.

- Correlational Designs : These designs explore the relationships between two or more variables without manipulation.

- Descriptive Designs : These include observational studies, case studies, and surveys, and are used to describe phenomena without manipulating the study environment.

Challenges in Research Design

No research design is without its challenges. Researchers must anticipate and plan for potential issues that could affect the integrity of their results. This proactive approach can include considering ethical implications, managing biases, and ensuring a representative sample.

Anticipating and Overcoming Obstacles

Effective research design involves not only planning for what is expected but also preparing for the unexpected. This could involve creating contingency plans for data collection or considering alternative interpretations of the data.

The meticulous nature of crafting a research design can be daunting, yet it is an indispensable stage in the research process. By understanding the ins and outs of research design, psychologists and researchers are better equipped to unveil the intricacies of human behavior and mental processes, contributing valuable knowledge to the field.

What do you think? How might the principles of research design apply to other areas of study? Can you think of a situation where a strong research design could make a difference in the outcome of a study?

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

Research Methods in Psychology

1 Introduction to Psychological Research – Objectives and Goals, Problems, Hypothesis and Variables

- Nature of Psychological Research

- The Context of Discovery

- Context of Justification

- Characteristics of Psychological Research

- Goals and Objectives of Psychological Research

2 Introduction to Psychological Experiments and Tests

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Extraneous Variables

- Experimental and Control Groups

- Introduction of Test

- Types of Psychological Test

- Uses of Psychological Tests

3 Steps in Research

- Research Process

- Identification of the Problem

- Review of Literature

- Formulating a Hypothesis

- Identifying Manipulating and Controlling Variables

- Formulating a Research Design

- Constructing Devices for Observation and Measurement

- Sample Selection and Data Collection

- Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Hypothesis Testing

- Drawing Conclusion

4 Types of Research and Methods of Research

- Historical Research

- Descriptive Research

- Correlational Research

- Qualitative Research

- Ex-Post Facto Research

- True Experimental Research

- Quasi-Experimental Research

5 Definition and Description Research Design, Quality of Research Design

- Research Design

- Purpose of Research Design

- Design Selection

- Criteria of Research Design

- Qualities of Research Design

6 Experimental Design (Control Group Design and Two Factor Design)

- Experimental Design

- Control Group Design

- Two Factor Design

7 Survey Design

- Survey Research Designs

- Steps in Survey Design

- Structuring and Designing the Questionnaire

- Interviewing Methodology

- Data Analysis

- Final Report

8 Single Subject Design

- Single Subject Design: Definition and Meaning

- Phases Within Single Subject Design

- Requirements of Single Subject Design

- Characteristics of Single Subject Design

- Types of Single Subject Design

- Advantages of Single Subject Design

- Disadvantages of Single Subject Design

9 Observation Method

- Definition and Meaning of Observation

- Characteristics of Observation

- Types of Observation

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Observation

- Guides for Observation Method

10 Interview and Interviewing

- Definition of Interview

- Types of Interview

- Aspects of Qualitative Research Interviews

- Interview Questions

- Convergent Interviewing as Action Research

- Research Team

11 Questionnaire Method

- Definition and Description of Questionnaires

- Types of Questionnaires

- Purpose of Questionnaire Studies

- Designing Research Questionnaires

- The Methods to Make a Questionnaire Efficient

- The Types of Questionnaire to be Included in the Questionnaire

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaire

- When to Use a Questionnaire?

12 Case Study

- Definition and Description of Case Study Method

- Historical Account of Case Study Method

- Designing Case Study

- Requirements for Case Studies

- Guideline to Follow in Case Study Method

- Other Important Measures in Case Study Method

- Case Reports

13 Report Writing

- Purpose of a Report

- Writing Style of the Report

- Report Writing – the Do’s and the Don’ts

- Format for Report in Psychology Area

- Major Sections in a Report

14 Review of Literature

- Purposes of Review of Literature

- Sources of Review of Literature

- Types of Literature

- Writing Process of the Review of Literature

- Preparation of Index Card for Reviewing and Abstracting

15 Methodology

- Definition and Purpose of Methodology

- Participants (Sample)

- Apparatus and Materials

16 Result, Analysis and Discussion of the Data

- Definition and Description of Results

- Statistical Presentation

- Tables and Figures

17 Summary and Conclusion

- Summary Definition and Description

- Guidelines for Writing a Summary

- Writing the Summary and Choosing Words

- A Process for Paraphrasing and Summarising

- Summary of a Report

- Writing Conclusions

18 References in Research Report

- Reference List (the Format)

- References (Process of Writing)

- Reference List and Print Sources

- Electronic Sources

- Book on CD Tape and Movie

- Reference Specifications

- General Guidelines to Write References

Share on Mastodon

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.2 Research Designs in Psychology

Learning objectives.

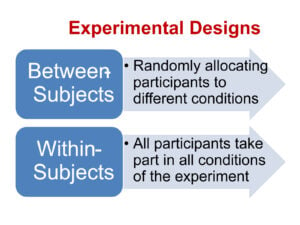

- Differentiate the goals of descriptive, correlational, and experimental research designs, and explain the advantages and disadvantages of each.

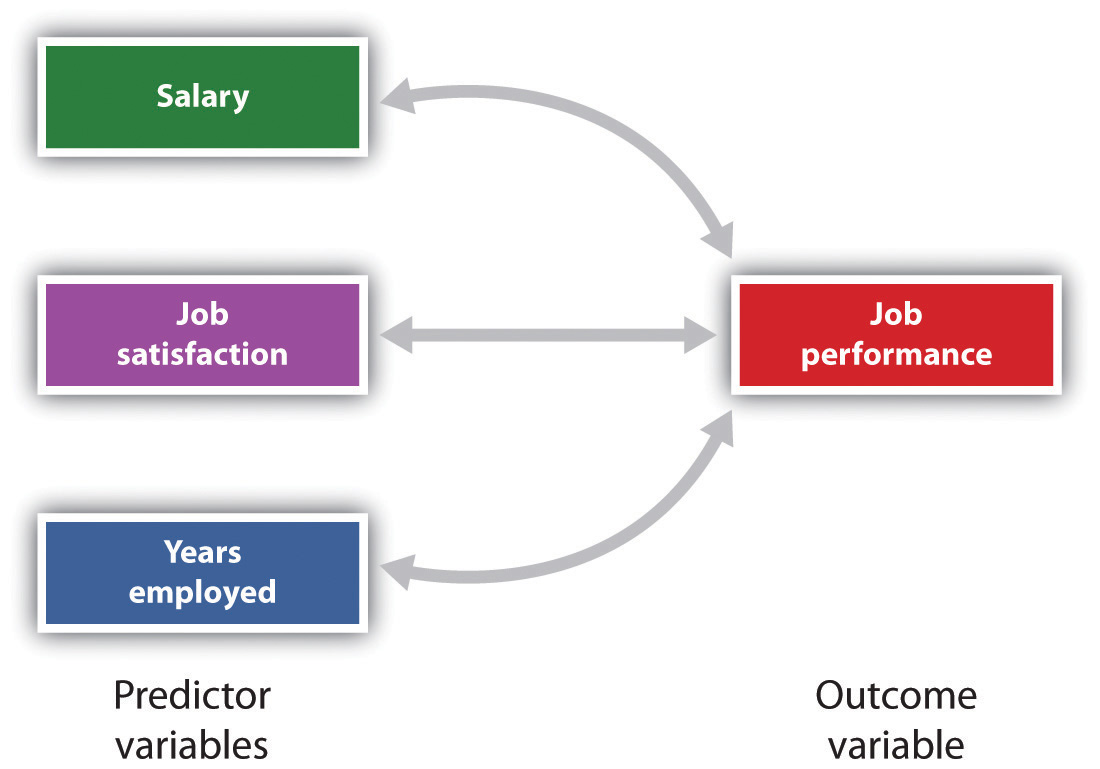

Psychologists agree that if their ideas and theories about human behaviour are to be taken seriously, they must be backed up by data. Researchers have a variety of research designs available to them in testing their predictions. A research design is the specific method a researcher uses to collect, analyze, and interpret data. Psychologists use three major types of research designs in their research, and each provides an essential avenue for scientific investigation. Descriptive research is designed to provide a snapshot of the current state of affairs. Correlational research is designed to discover relationships among variables. Experimental research is designed to assess cause and effect. Each of the three research designs has specific strengths and limitations, and it is important to understand how each differs. See the table below for a summary.

| Research Design | Goal | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive | To create a snapshot of the current state of affairs. | Provides a relatively complete picture of what is occurring at a given time. Allows the development of questions for further study. | Does not assess relationships among variables. Cannot be used to draw inferences about cause and effect. |

| Correlational | To assess the relationships between and among two or more variables. | Allows testing of expected relationships between and among variables and the making of predictions. Can assess these relationships in everyday life events. | Cannot be used to draw inferences about cause and effect. |

| Experimental | To assess the causal impact of one or more experimental manipulations on a dependent variable. | Allows conclusions to be drawn about the causal relationships among variables. | Cannot experimentally manipulate many important variables. May be expensive and time-consuming. |

| Data source: Stangor, 2011. | |||

Descriptive research: Assessing the current state of affairs

Descriptive research is designed to create a snapshot of the current thoughts, feelings, or behaviour of individuals. This section reviews four types of descriptive research: case studies, surveys and tests, naturalistic observation, and laboratory observation.

Sometimes the data in a descriptive research project are collected from only a small set of individuals, often only one person or a single small group. These research designs are known as case studies , which are descriptive records of one or more individual’s experiences and behaviour. Sometimes case studies involve ordinary individuals, as when developmental psychologist Jean Piaget used his observation of his own children to develop his stage theory of cognitive development. More frequently, case studies are conducted on individuals who have unusual or abnormal experiences or characteristics, this may include those who find themselves in particularly difficult or stressful situations. The assumption is that carefully studying individuals can give us results that tell us something about human nature. Of course, one individual cannot necessarily represent a larger group of people who were in the same circumstances.

Sigmund Freud was a master of using the psychological difficulties of individuals to draw conclusions about basic psychological processes. Freud wrote case studies of some of his most interesting patients and used these careful examinations to develop his important theories of personality. One classic example is Freud’s description of “Little Hans,” a child whose fear of horses was interpreted in terms of repressed sexual impulses and the Oedipus complex (Freud, 1909/1964).

Another well-known case study is of Phineas Gage, a man whose thoughts and emotions were extensively studied by cognitive psychologists after a railroad spike was blasted through his skull in an accident. Although there are questions about the interpretation of this case study (Kotowicz, 2007), it did provide early evidence that the brain’s frontal lobe is involved in emotion and morality (Damasio et al., 2005). An interesting example of a case study in clinical psychology is described by Milton Rokeach (1964), who investigated in detail the beliefs of and interactions among three patients with schizophrenia, all of whom were convinced they were Jesus Christ.

Research using case studies has some unique challenges when it comes to interpreting the data. By definition, case studies are based on one or a very small number of individuals. While their situations may be unique, we cannot know how well they represent what would be found in other cases. Furthermore, the information obtained in a case study may be inaccurate or incomplete. While researchers do their best to objectively understand one case, making any generalizations to other people is problematic. Researchers can usually only speculate about cause and effect, and even then, they must do so with great caution. Case studies are particularly useful when researchers are starting out to study something about which there is not much research or as a source for generating hypotheses that can be tested using other research designs.

In other cases, the data from descriptive research projects come in the form of a survey , which is a measure administered through either an interview or a written questionnaire to get a picture of the beliefs or behaviours of a sample of people of interest. The people chosen to participate in the research, known as the sample , are selected to be representative of all the people that the researcher wishes to know about, known as the population . The representativeness of samples is enormously important. For example, a representative sample of Canadians must reflect Canada’s demographic make-up in terms of age, sex, gender orientation, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and so on. Research based on unrepresentative samples is limited in generalizability , meaning it will not apply well to anyone who was not represented in the sample. Psychologists use surveys to measure a wide variety of behaviours, attitudes, opinions, and facts. Surveys could be used to measure the amount of exercise people get every week, eating or drinking habits, attitudes towards climate change, and so on. These days, many surveys are available online, and they tend to be aimed at a wide audience. Statistics Canada is a rich source of surveys of Canadians on a diverse array of topics. Their databases are searchable and downloadable, and many deal with topics of interest to psychologists, such as mental health, wellness, and so on. Their raw data may be used by psychologists who are able to take advantage of the fact that the data have already been collected. This is called archival research .

Related to surveys are psychological tests . These are measures developed by psychologists to assess one’s score on a psychological construct, such as extroversion, self-esteem, or aptitude for a particular career. The difference between surveys and tests is really down to what is being measured, with surveys more likely to be fact-gathering and tests more likely to provide a score on a psychological construct.

As you might imagine, respondents to surveys and psychological tests are not always accurate or truthful in their replies. Respondents may also skew their answers in the direction they think is more socially desirable or in line with what the researcher expects. Sometimes people do not have good insight into their own behaviour and are not accurate in judging themselves. Sometimes tests have built-in social desirability or lie scales that attempt to help researchers understand when someone’s scores might need to be discarded from the research because they are not accurate.

Tests and surveys are only useful if they are valid and reliable . Validity exists when an instrument actually measures what you think it measures (e.g., a test of intelligence that actually measures how many years of education you have lacks validity). Demonstrating the validity of a test or survey is the responsibility of any researcher who uses the instrument. Reliability is a related but different construct; it exists when a test or survey gives the same responses from time to time or in different situations. For example, if you took an intelligence test three times and every time it gave you a different score, that would not be a reliable test. Demonstrating the reliability of tests and surveys is another responsibility of researchers. There are different types of validity and reliability, and there is a branch of psychology devoted to understanding not only how to demonstrate that tests and surveys are valid and reliable, but also how to improve them.

An important criticism of psychological research is its reliance on so-called WEIRD samples (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). WEIRD stands for Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. People fitting the WEIRD description have been over-represented in psychological research, while people from poorer, less-educated backgrounds, for example, have participated far less often. This criticism is important because in psychology we may be trying to understand something about people in general. For example, if we want to understand whether early enrichment programs can boost IQ scores later, we need to conduct this research using people from a variety of backgrounds and situations. Most of the world’s population is not WEIRD, so psychologists trying to conduct research that has broad generalizability need to expand their participant pool to include a more representative sample.

Another type of descriptive research is naturalistic observation , which refers to research based on the observation of everyday events. For instance, a developmental psychologist who watches children on a playground and describes what they say to each other while they play is conducting naturalistic observation, as is a biopsychologist who observes animals in their natural habitats. Naturalistic observation is challenging because, in order for it to be accurate, the observer must be effectively invisible. Imagine walking onto a playground, armed with a clipboard and pencil to watch children a few feet away. The presence of an adult may change the way the children behave; if the children know they are being watched, they may not behave in the same ways as they would when no adult is present. Researchers conducting naturalistic observation studies have to find ways to recede into the background so that their presence does not cause the behaviour they are watching to change. They also must find ways to record their observations systematically and completely — not an easy task if you are watching children, for example. As such, it is common to have multiple observers working independently; their combined observations can provide a more accurate record of what occurred.

Sometimes, researchers conducting observational research move out of the natural world and into a laboratory. Laboratory observation allows much more control over the situation and setting in which the participants will be observed. The downside to moving into a laboratory is the potential artificiality of the setting; the participants may not behave the same way in the lab as they would in the natural world, so the behaviour that is observed may not be completely authentic. Consider the researcher who is interested in aggression in children. They might go to a school playground and record what occurs; however, this could be quite time-consuming if the frequency is low or if the children are playing some distance away and their behaviour is difficult to interpret. Instead, the researcher could construct a play setting in a laboratory and attempt to observe aggressive behaviours in this smaller and more controlled context; for instance, they could only provide one highly desirable toy instead of one for each child. What they gain in control, they lose in artificiality. In this example, the possibility for children to act differently in the lab than they would in the real world would create a challenge in interpreting results.

Correlational research: Seeking relationships among variables

In contrast to descriptive research — which is designed primarily to provide a snapshot of behaviour, attitudes, and so on — correlational research involves measuring the relationship between two variables. Variables can be behaviours, attitudes, and so on. Anything that can be measured is a potential variable. The key aspect of correlational research is that the researchers are not asking some of their participants to do one thing and others to do something else; all of the participants are providing scores on the same two variables. Correlational research is not about how an individual scores; rather, it seeks to understand the association between two things in a larger sample of people. The previous comments about the representativeness of the sample all apply in correlational research. Researchers try to find a sample that represents the population of interest.

An example of correlation research would be to measure the association between height and weight. We should expect that there is a relationship because taller people have more mass and therefore should weigh more than short people. We know from observation, however, that there are many tall, thin people just as there are many short, overweight people. In other words, we would expect that in a group of people, height and weight should be systematically related (i.e., correlated), but the degree of relatedness is not expected to be perfect. Imagine we repeated this study with samples representing different populations: elite athletes, women over 50, children under 5, and so on. We might make different predictions about the relationship between height and weight based on the characteristics of the sample. This highlights the importance of obtaining a representative sample.

Psychologists make frequent use of correlational research designs. Examples might be the association between shyness and number of Facebook friends, between age and conservatism, between time spent on social media and grades in school, and so on. Correlational research designs tend to be relatively less expensive because they are time-limited and can often be conducted without much equipment. Online survey platforms have made data collection easier than ever. Some correlational research does not even necessitate collecting data; researchers using archival data sets as described above simply download the raw data from another source. For example, suppose you were interested in whether or not height is related to the number of points scored in hockey players. You could extract data for both variables from nhl.com , the official National Hockey League website, and conduct archival research using the data that have already been collected.

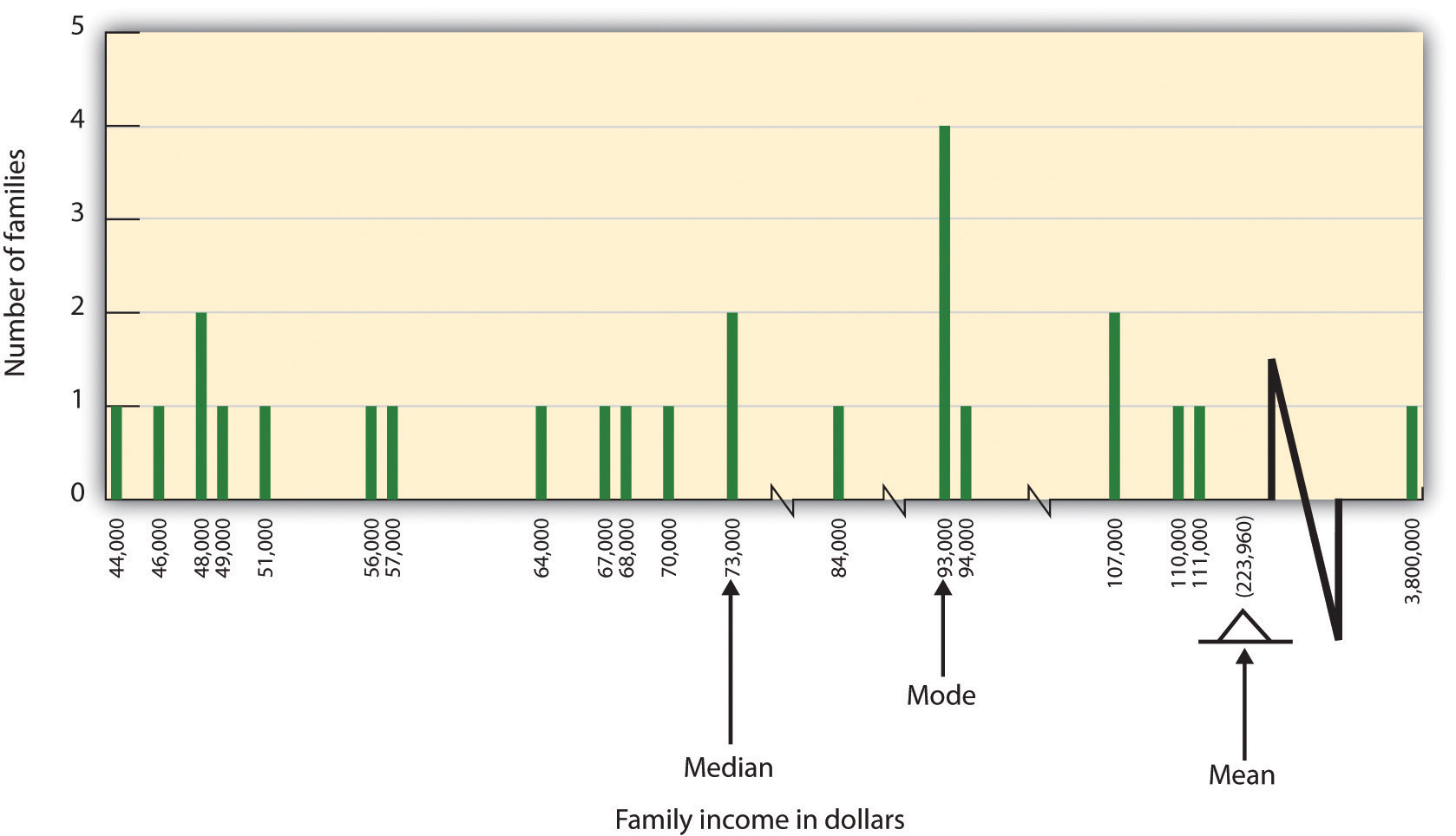

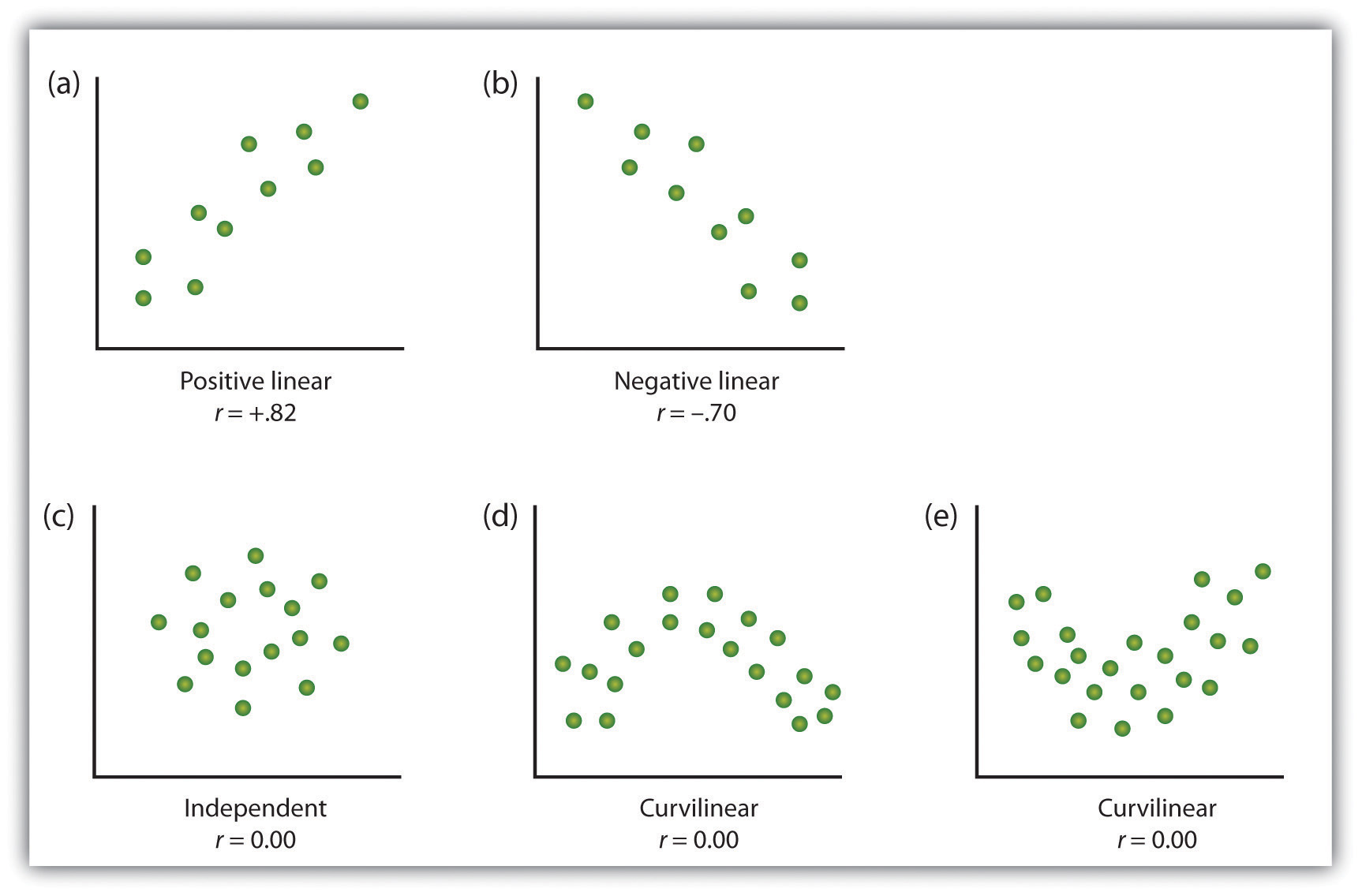

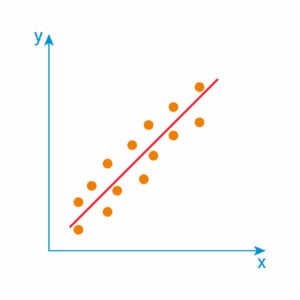

Correlational research designs look for associations between variables. A statistic that measures that association is the correlation coefficient. Correlation coefficients can be either positive or negative, and they range in value from -1.0 through 0 to 1.0. The most common statistical measure is the Pearson correlation coefficient , which is symbolized by the letter r . Positive values of r (e.g., r = .54 or r = .67) indicate that the relationship is positive, whereas negative values of r (e.g., r = –.30 or r = –.72) indicate negative relationships. The closer the coefficient is to -1 or +1, and the further away from zero, the greater the size of the association between the two variables. For instance, r = –.54 is a stronger relationship than r = .30, and r = .72 is a stronger relationship than r = –.57. Correlations of 0 indicate no relationship between the two variables.

Examples of positive correlation coefficients would include those between height and weight, between education and income, and between age and mathematical abilities in children. In each case, people who score higher, or lower, on one of the variables also tend to score higher, or lower, on the other variable. Negative correlations occur when people score high on one variable and low on the other. Examples of negative linear relationships include those between the age of a child and the number of diapers the child uses and between time practising and errors made on a learning task. In these cases, people who score higher on one of the variables tend to score lower on the other variable. Note that the correlation coefficient does not tell you anything about one specific person’s score.

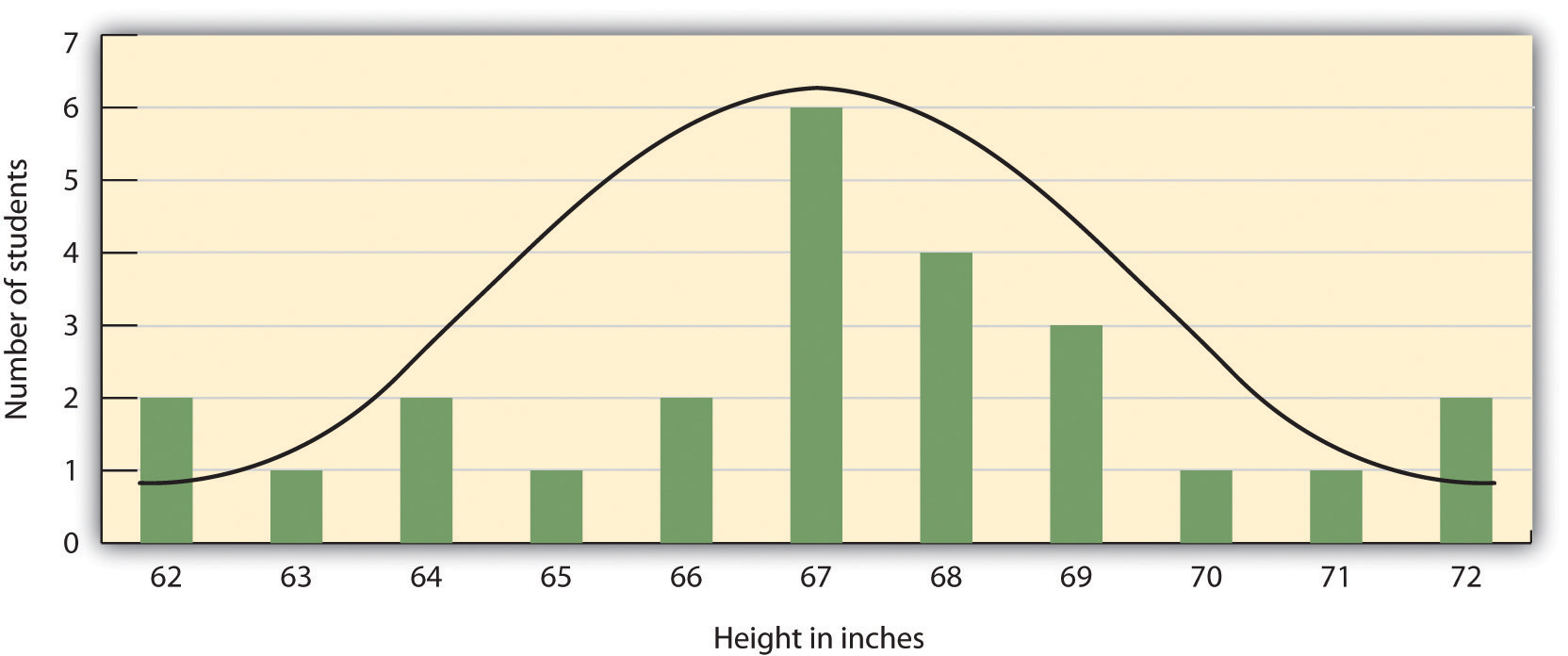

One way of organizing the data from a correlational study with two variables is to graph the values of each of the measured variables using a scatterplot. A scatterplot is a visual image of the relationship between two variables (see Figure 2.3 ). A point is plotted for each individual at the intersection of his or her scores for the two variables. In this example, data extracted from the official National Hockey League (NHL) website of 30 randomly picked hockey players for the 2017/18 season. For each of these players, there is a dot representing player height and number of points (i.e., goals plus assists). The slope or angle of the dotted line through the middle of the scatter tells us something about the strength and direction of the correlation. In this case, the line slopes up slightly to the right, indicating a positive but small correlation. In these NHL players, there is not much of relationship between height and points. The Pearson correlation calculated for this sample is r = 0.14. It is possible that the correlation would be totally different in a different sample of players, such as a greater number, only those who played a full season, only rookies, only forwards, and so on.

For practise constructing and interpreting scatterplots, see the following:

- Interactive Quiz: Positive and Negative Associations in Scatterplots (Khan Academy, 2018)

When the association between the variables on the scatterplot can be easily approximated with a straight line, the variables are said to have a linear relationship . We are only going to consider linear relationships here. Just be aware that some pairs of variables have non-linear relationships, such as the relationship between physiological arousal and performance. Both high and low arousal are associated with sub-optimal performance, shown by a U-shaped scatterplot curve.

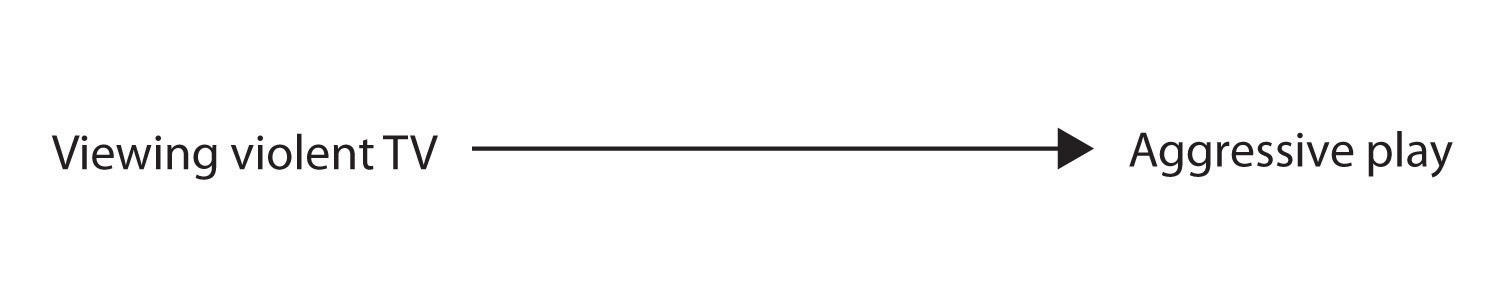

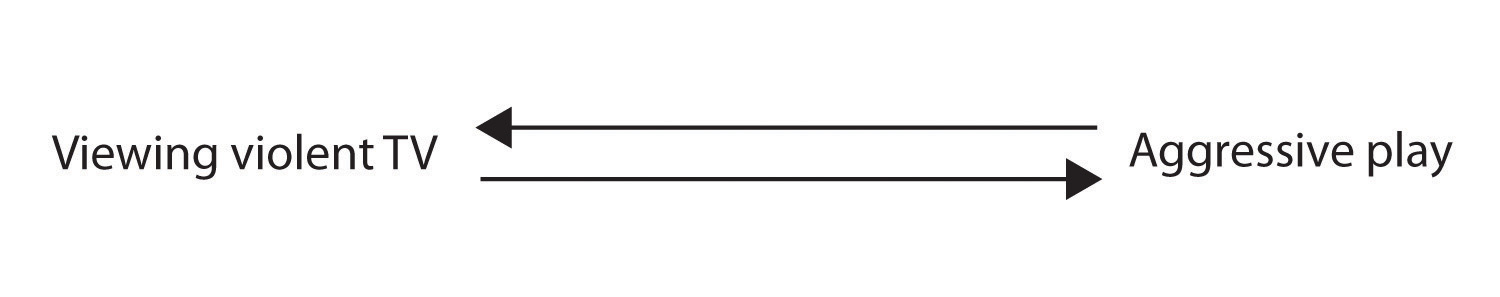

The most important limitation of correlational research designs is that they cannot be used to draw conclusions about the causal relationships among the measured variables; in other words, we cannot know what causes what in correlational research. Consider, for instance, a researcher who has hypothesized that viewing violent behaviour will cause increased aggressive play in children. The researcher has collected, from a sample of Grade 4 children, a measure of how many violent television shows each child views during the week as well as a measure of how aggressively each child plays on the school playground. From the data collected, the researcher discovers a positive correlation between the two measured variables.

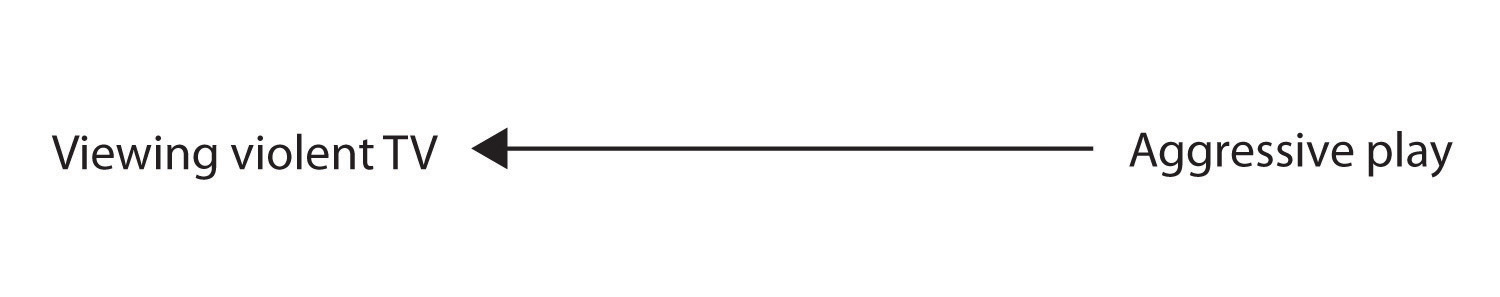

Although this positive correlation appears to support the researcher’s hypothesis, it cannot be taken to indicate that viewing violent television causes aggressive behaviour. Although the researcher is tempted to assume that viewing violent television causes aggressive play, there are other possibilities. One alternative possibility is that the causal direction is exactly opposite of what has been hypothesized; perhaps children who have behaved aggressively at school are more likely to prefer violent television shows at home.

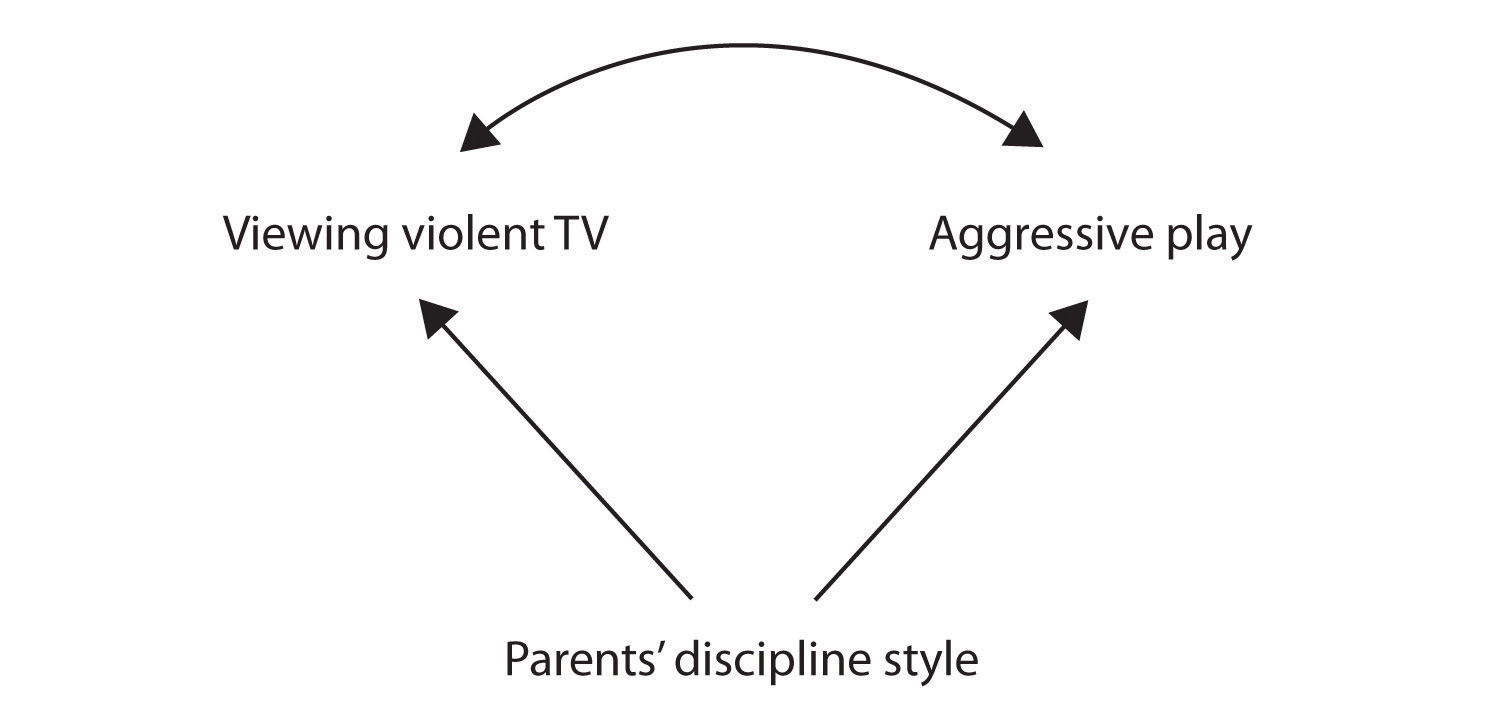

Still another possible explanation for the observed correlation is that it has been produced by a so-called third variable , one that is not part of the research hypothesis but that causes both of the observed variables and, thus, the correlation between them. In our example, a potential third variable is the discipline style of the children’s parents. Parents who use a harsh and punitive discipline style may allow children to watch violent television and to behave aggressively in comparison to children whose parents use less different types of discipline.

To review, whenever we have a correlation that is not zero, there are three potential pathways of cause and effect that must be acknowledged. The easiest way to practise understanding this challenge is to automatically designate the two variables X and Y. It does not matter which is which. Then, think through any ways in which X might cause Y. Then, flip the direction of cause and effect, and consider how Y might cause X. Finally, and possibly the most challenging, try to think of other variables — let’s call these C — that were not part of the original correlation, which cause both X and Y. Understanding these potential explanations for correlational research is an important aspect of scientific literacy. In the above example, we have shown how X (i.e., viewing violent TV) could cause Y (i.e., aggressive behaviour), how Y could cause X, and how C (i.e., parenting) could cause both X and Y.

Test your understanding with each example below. Find three different interpretations of cause and effect using the procedure outlined above. In each case, identify variables X, Y, and C:

- A positive correlation between dark chocolate consumption and health

- A negative correlation between sleep and smartphone use

- A positive correlation between children’s aggressiveness and time spent playing video games

- A negative association between time spent exercising and consumption of junk food

In sum, correlational research designs have both strengths and limitations. One strength is that they can be used when experimental research is not possible or when fewer resources are available. Correlational designs also have the advantage of allowing the researcher to study behaviour as it occurs in everyday life. We can also use correlational designs to make predictions, such as predicting the success of job trainees based on their test scores during training. They are also excellent sources of suggested avenues for further research, but we cannot use such correlational information to understand cause and effect. For that, researchers rely on experiments.

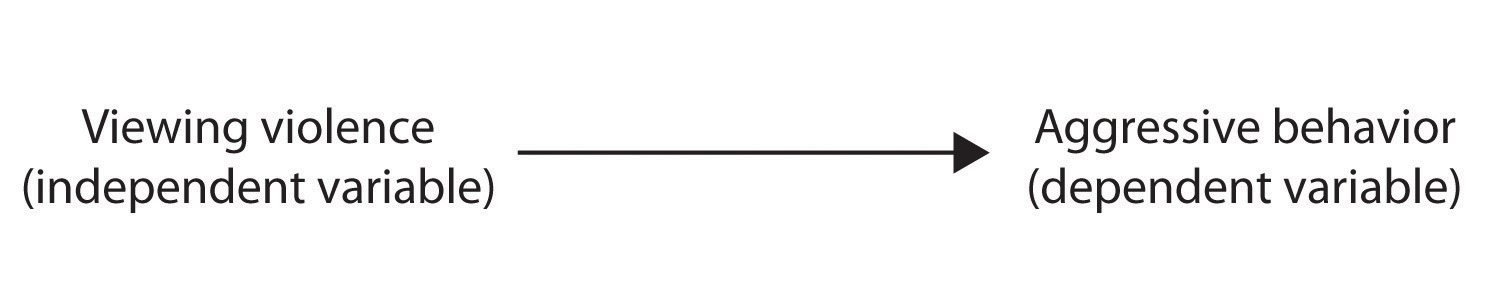

Experimental research: Understanding the causes of behaviour

The goal of experimental research design is to provide definitive conclusions about the causal relationships among the variables in the research hypothesis. In an experimental research design, there are independent variables and dependent variables. The independent variable is the one manipulated by the researchers so that there is more than one condition. The dependent variable is the outcome or score on the measure of interest that is dependent on the actions of the independent variable. Let’s consider a classic drug study to illustrate the relationship between independent and dependent variables. To begin, a sample of people with a medical condition are randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In one condition, they are given a drug over a period of time. In the other condition, a placebo is given for the same period of time. To be clear, a placebo is a type of medication that looks like the real thing but is actually chemically inert, sometimes referred to as a”sugar pill.” After the testing period, the groups are compared to see if the drug condition shows better improvement in health than the placebo condition.

While the basic design of experiments is quite simple, the success of experimental research rests on meeting a number of criteria. Some important criteria are:

- Participants must be randomly assigned to the conditions so that there are no differences between the groups. In the drug study example, you could not assign the males to the drug condition and the females to the placebo condition. The groups must be demographically equivalent.

- There must be a control condition. Having a condition that does not receive treatment allows experimenters to compare the results of the drug to the results of placebo.

- The only thing that can change between the conditions is the independent variable. For example, the participants in the drug study should receive the medication at the same place, from the same person, at the same time, and so on, for both conditions. Experiments often employ double-blind procedures in which neither the experimenter nor the participants know which condition any participant is in during the experiment. In a single-blind procedure, the participants do not know which condition they are in.

- The sample size has to be large and diverse enough to represent the population of interest. For example, a pharmaceutical company should not use only men in their drug study if the drug will eventually be prescribed to women as well.

- Experimenter effects should be minimized. This means that if there is a difference in scores on the dependent variable, they should not be attributable to something the experimenter did or did not do. For example, if an experiment involved comparing a yoga condition with an exercise condition, experimenters would need to make sure that they treated the participants exactly the same in each condition. They would need to control the amount of time they spent with the participants, how much they interacted verbally, smiled at the participants, and so on. Experimenters often employ research assistants who are blind to the participants’ condition to interact with the participants.

As you can probably see, much of experimental design is about control. The experimenters have a high degree of control over who does what. All of this tight control is to try to ensure that if there is a difference between the different levels of the independent variable, it is detectable. In other words, if there is even a small difference between a drug and placebo, it is detected. Furthermore, this level of control is aimed at ensuring that the only difference between conditions is the one the experimenters are testing while making correct and accurate determinations about cause and effect.

Research Focus

Video games and aggression

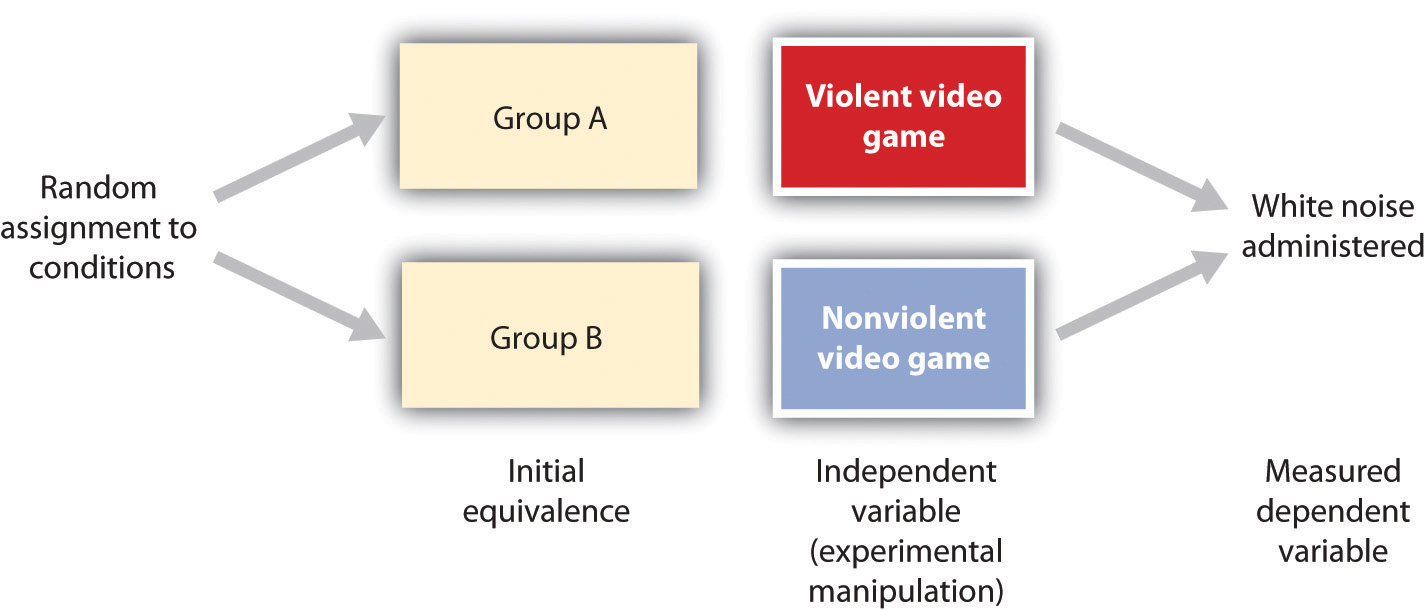

Consider an experiment conducted by Craig Anderson and Karen Dill (2000). The study was designed to test the hypothesis that viewing violent video games would increase aggressive behaviour. In this research, male and female undergraduates from Iowa State University were given a chance to play with either a violent video game (e.g., Wolfenstein 3D) or a nonviolent video game (e.g., Myst). During the experimental session, the participants played their assigned video games for 15 minutes. Then, after the play, each participant played a competitive game with an opponent in which the participant could deliver blasts of white noise through the earphones of the opponent. The operational definition of the dependent variable (i.e., aggressive behaviour) was the level and duration of noise delivered to the opponent. The design of the experiment is shown below (see Figure 2.4 ).

There are two strong advantages of the experimental research design. First, there is assurance that the independent variable, also known as the experimental manipulation , occurs prior to the measured dependent variable; second, there is creation of initial equivalence between the conditions of the experiment, which is made possible by using random assignment to conditions.

Experimental designs have two very nice features. For one, they guarantee that the independent variable occurs prior to the measurement of the dependent variable. This eliminates the possibility of reverse causation. Second, the influence of common-causal variables is controlled, and thus eliminated, by creating initial equivalence among the participants in each of the experimental conditions before the manipulation occurs.

The most common method of creating equivalence among the experimental conditions is through random assignment to conditions, a procedure in which the condition that each participant is assigned to is determined through a random process, such as drawing numbers out of an envelope or using a random number table. Anderson and Dill first randomly assigned about 100 participants to each of their two groups: Group A and Group B. Since they used random assignment to conditions, they could be confident that, before the experimental manipulation occurred, the students in Group A were, on average, equivalent to the students in Group B on every possible variable, including variables that are likely to be related to aggression, such as parental discipline style, peer relationships, hormone levels, diet — and in fact everything else.

Then, after they had created initial equivalence, Anderson and Dill created the experimental manipulation; they had the participants in Group A play the violent game and the participants in Group B play the nonviolent game. Then, they compared the dependent variable (i.e., the white noise blasts) between the two groups, finding that the students who had viewed the violent video game gave significantly longer noise blasts than did the students who had played the nonviolent game.

Anderson and Dill had from the outset created initial equivalence between the groups. This initial equivalence allowed them to observe differences in the white noise levels between the two groups after the experimental manipulation, leading to the conclusion that it was the independent variable, and not some other variable, that caused these differences. The idea is that the only thing that was different between the students in the two groups was the video game they had played.

Sometimes, experimental research has a confound. A confound is a variable that has slipped unwanted into the research and potentially caused the results because it has created a systematic difference between the levels of the independent variable. In other words, the confound caused the results, not the independent variable. For example, suppose you were a researcher who wanted to know if eating sugar just before an exam was beneficial. You obtain a large sample of students, divide them randomly into two groups, give everyone the same material to study, and then give half of the sample a chocolate bar containing high levels of sugar and the other half a glass of water before they write their test. Lo and behold, you find the chocolate bar group does better. However, the chocolate bar also contains caffeine, fat and other ingredients. These other substances besides sugar are potential confounds; for example, perhaps caffeine rather than sugar caused the group to perform better. Confounds introduce a systematic difference between levels of the independent variable such that it is impossible to distinguish between effects due to the independent variable and effects due to the confound.

Despite the advantage of determining causation, experiments do have limitations. One is that they are often conducted in laboratory situations rather than in the everyday lives of people. Therefore, we do not know whether results that we find in a laboratory setting will necessarily hold up in everyday life. Do people act the same in a laboratory as they do in real life? Often researchers are forced to balance the need for experimental control with the use of laboratory conditions that can only approximate real life.

Additionally, it is very important to understand that many of the variables that psychologists are interested in are not things that can be manipulated experimentally. For example, psychologists interested in sex differences cannot randomly assign participants to be men or women. If a researcher wants to know if early attachments to parents are important for the development of empathy, or in the formation of adult romantic relationships, the participants cannot be randomly assigned to childhood attachments. Thus, a large number of human characteristics cannot be manipulated or assigned. This means that research may look experimental because it has different conditions (e.g., men or women, rich or poor, highly intelligent or not so intelligent, etc.); however, it is quasi-experimental . The challenge in interpreting quasi-experimental research is that the inability to randomly assign the participants to condition results in uncertainty about cause and effect. For example, if you find that men and women differ in some ability, it could be biology that is the cause, but it is equally likely it could be the societal experience of being male or female that is responsible.

Of particular note, while experiments are the gold standard for understanding cause and effect, a large proportion of psychology research is not experimental for a variety of practical and ethical reasons.

Key Takeaways

- Descriptive, correlational, and experimental research designs are used to collect and analyze data.

- Descriptive designs include case studies, surveys, psychological tests, naturalistic observation, and laboratory observation. The goal of these designs is to get a picture of the participants’ current thoughts, feelings, or behaviours.

- Correlational research designs measure the relationship between two or more variables. The variables may be presented on a scatterplot to visually show the relationships. The Pearson correlation coefficient is a measure of the strength of linear relationship between two variables. Correlations have three potential pathways for interpreting cause and effect.

- Experimental research involves the manipulation of an independent variable and the measurement of a dependent variable. Done correctly, experiments allow researchers to make conclusions about cause and effect. There are a number of criteria that must be met in experimental design. Not everything can be studied experimentally, and laboratory experiments may not replicate real-life conditions well.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- There is a negative correlation between how close students sit to the front of the classroom and their final grade in the class. Explain some possible reasons for this.

- Imagine you are tasked with creating a survey of online habits of Canadian teenagers. What questions would you ask and why? How valid and reliable would your test be?

- Imagine a researcher wants to test the hypothesis that participating in psychotherapy will cause a decrease in reported anxiety. Describe the type of research design the investigator might use to draw this conclusion. What would be the independent and dependent variables in the research?

Image Attributions

Figure 2.2. This Might Be Me in a Few Years by Frank Kovalchek is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 2.3. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 2.4. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Anderson, C. A., & Dill, K. E. (2000). Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 (4), 772–790.

Damasio, H., Grabowski, T., Frank, R., Galaburda, A. M., Damasio, A. R., Cacioppo, J. T., & Berntson, G. G. (2005). The return of Phineas Gage: Clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. In Social neuroscience: Key readings (pp. 21–28). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Freud, S. (1909/1964). Analysis of phobia in a five-year-old boy. In E. A. Southwell & M. Merbaum (Eds.), Personality: Readings in theory and research (pp. 3–32). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. (Original work published 1909)

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzaya, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33 , 61–83.

Kotowicz, Z. (2007). The strange case of Phineas Gage. History of the Human Sciences, 20 (1), 115–131.

Rokeach, M. (1964). The three Christs of Ypsilanti: A psychological study . New York, NY: Knopf.

Stangor, C. (2011). Research methods for the behavioral sciences (4th ed.) . Mountain View, CA: Cengage.

Psychology - 1st Canadian Edition Copyright © 2020 by Sally Walters is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Clin Res

- v.9(4); Oct-Dec 2018

Study designs: Part 1 – An overview and classification

Priya ranganathan.

Department of Anaesthesiology, Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Rakesh Aggarwal

1 Department of Gastroenterology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

There are several types of research study designs, each with its inherent strengths and flaws. The study design used to answer a particular research question depends on the nature of the question and the availability of resources. In this article, which is the first part of a series on “study designs,” we provide an overview of research study designs and their classification. The subsequent articles will focus on individual designs.

INTRODUCTION

Research study design is a framework, or the set of methods and procedures used to collect and analyze data on variables specified in a particular research problem.

Research study designs are of many types, each with its advantages and limitations. The type of study design used to answer a particular research question is determined by the nature of question, the goal of research, and the availability of resources. Since the design of a study can affect the validity of its results, it is important to understand the different types of study designs and their strengths and limitations.

There are some terms that are used frequently while classifying study designs which are described in the following sections.

A variable represents a measurable attribute that varies across study units, for example, individual participants in a study, or at times even when measured in an individual person over time. Some examples of variables include age, sex, weight, height, health status, alive/dead, diseased/healthy, annual income, smoking yes/no, and treated/untreated.

Exposure (or intervention) and outcome variables

A large proportion of research studies assess the relationship between two variables. Here, the question is whether one variable is associated with or responsible for change in the value of the other variable. Exposure (or intervention) refers to the risk factor whose effect is being studied. It is also referred to as the independent or the predictor variable. The outcome (or predicted or dependent) variable develops as a consequence of the exposure (or intervention). Typically, the term “exposure” is used when the “causative” variable is naturally determined (as in observational studies – examples include age, sex, smoking, and educational status), and the term “intervention” is preferred where the researcher assigns some or all participants to receive a particular treatment for the purpose of the study (experimental studies – e.g., administration of a drug). If a drug had been started in some individuals but not in the others, before the study started, this counts as exposure, and not as intervention – since the drug was not started specifically for the study.

Observational versus interventional (or experimental) studies

Observational studies are those where the researcher is documenting a naturally occurring relationship between the exposure and the outcome that he/she is studying. The researcher does not do any active intervention in any individual, and the exposure has already been decided naturally or by some other factor. For example, looking at the incidence of lung cancer in smokers versus nonsmokers, or comparing the antenatal dietary habits of mothers with normal and low-birth babies. In these studies, the investigator did not play any role in determining the smoking or dietary habit in individuals.

For an exposure to determine the outcome, it must precede the latter. Any variable that occurs simultaneously with or following the outcome cannot be causative, and hence is not considered as an “exposure.”

Observational studies can be either descriptive (nonanalytical) or analytical (inferential) – this is discussed later in this article.

Interventional studies are experiments where the researcher actively performs an intervention in some or all members of a group of participants. This intervention could take many forms – for example, administration of a drug or vaccine, performance of a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure, and introduction of an educational tool. For example, a study could randomly assign persons to receive aspirin or placebo for a specific duration and assess the effect on the risk of developing cerebrovascular events.

Descriptive versus analytical studies

Descriptive (or nonanalytical) studies, as the name suggests, merely try to describe the data on one or more characteristics of a group of individuals. These do not try to answer questions or establish relationships between variables. Examples of descriptive studies include case reports, case series, and cross-sectional surveys (please note that cross-sectional surveys may be analytical studies as well – this will be discussed in the next article in this series). Examples of descriptive studies include a survey of dietary habits among pregnant women or a case series of patients with an unusual reaction to a drug.

Analytical studies attempt to test a hypothesis and establish causal relationships between variables. In these studies, the researcher assesses the effect of an exposure (or intervention) on an outcome. As described earlier, analytical studies can be observational (if the exposure is naturally determined) or interventional (if the researcher actively administers the intervention).

Directionality of study designs

Based on the direction of inquiry, study designs may be classified as forward-direction or backward-direction. In forward-direction studies, the researcher starts with determining the exposure to a risk factor and then assesses whether the outcome occurs at a future time point. This design is known as a cohort study. For example, a researcher can follow a group of smokers and a group of nonsmokers to determine the incidence of lung cancer in each. In backward-direction studies, the researcher begins by determining whether the outcome is present (cases vs. noncases [also called controls]) and then traces the presence of prior exposure to a risk factor. These are known as case–control studies. For example, a researcher identifies a group of normal-weight babies and a group of low-birth weight babies and then asks the mothers about their dietary habits during the index pregnancy.

Prospective versus retrospective study designs

The terms “prospective” and “retrospective” refer to the timing of the research in relation to the development of the outcome. In retrospective studies, the outcome of interest has already occurred (or not occurred – e.g., in controls) in each individual by the time s/he is enrolled, and the data are collected either from records or by asking participants to recall exposures. There is no follow-up of participants. By contrast, in prospective studies, the outcome (and sometimes even the exposure or intervention) has not occurred when the study starts and participants are followed up over a period of time to determine the occurrence of outcomes. Typically, most cohort studies are prospective studies (though there may be retrospective cohorts), whereas case–control studies are retrospective studies. An interventional study has to be, by definition, a prospective study since the investigator determines the exposure for each study participant and then follows them to observe outcomes.