5 Essays About Homelessness

Around the world, people experience homelessness. According to a 2005 survey by the United Nations, 1.6 billion people lack adequate housing. The causes vary depending on the place and person. Common reasons include a lack of affordable housing, poverty, a lack of mental health services, and more. Homelessness is rooted in systemic failures that fail to protect those who are most vulnerable. Here are five essays that shine a light on the issue of homelessness:

What Would ‘Housing as a Human Right’ Look Like in California? (2020) – Molly Solomon

For some time, activists and organizations have proclaimed that housing is a human right. This essay explores what that means and that it isn’t a new idea. Housing as a human right was part of federal policy following the Great Depression. In a 1944 speech introducing what he called the “Second Bill of Rights,” President Roosevelt attempted to address poverty and income equality. The right to have a “decent home” was included in his proposals. Article 25 of the Universal Declaration also recognizes housing as a human right. It describes the right to an “adequate standard of living.” Other countries such as France and Scotland include the right to housing in their constitutions. In the US, small local governments have adopted resolutions on housing. How would it work in California?

At KQED, Molly Solomon covers housing affordability. Her stories have aired on NPR’s All Things Considered, Morning Edition, and other places. She’s won three national Edward R. Murrow awards.

“What People Get Wrong When They Try To End Homelessness” – James Abro

In his essay, James Abro explains what led up to six weeks of homelessness and his experiences helping people through social services. Following the death of his mother and eviction, Abro found himself unhoused. He describes himself as “fortunate” and feeling motivated to teach people how social services worked. However, he learned that his experience was somewhat unique. The system is complicated and those involved don’t understand homelessness. Abro believes investing in affordable housing is critical to truly ending homelessness.

James Abro is the founder of Advocate for Economic Fairness and 32 Beach Productions. He works as an advocate for homeless rights locally and nationally. Besides TalkPoverty, he contributes to Rebelle Society and is an active member of the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness.

“No Shelter For Some: Street-Sleepers” (2019)

This piece (by an unknown author) introduces the reader to homelessness in urban China. In the past decades, a person wouldn’t see many homeless people. This was because of strict rules on internal migration and government-supplied housing. Now, the rules have changed. People from rural areas can travel more and most urban housing is privatized. People who are homeless – known as “street-sleepers” are more visible. This essay is a good summary of the system (which includes a shift from police management of homelessness to the Ministry of Civil Affairs) and how street-sleepers are treated.

“A Window Onto An American Nightmare” (2020) – Nathan Heller

This essay from the New Yorker focuses on San Francisco’s history with homelessness, the issue’s complexities, and various efforts to address it. It also touches on how the pandemic has affected homelessness. One of the most intriguing parts of this essay is Heller’s description of becoming homeless. He says people “slide” into it, as opposed to plunging. As an example, someone could be staying with friends while looking for a job, but then the friends decide to stop helping. Maybe someone is jumping in and out of Airbnbs, looking for an apartment. Heller’s point is that the line between only needing a place to stay for a night or two and true “homelessness” is very thin.

Nathan Heller joined the New Yorker’s writing staff in 2013. He writes about technology, higher education, the Bay Area, socioeconomics, and more. He’s also a contributing editor at Vogue, a former columnist for Slate, and contributor to other publications.

“Homelessness in Ireland is at crisis point, and the vitriol shown towards homeless people is just as shocking” (2020)#- Megan Nolan

In Ireland, the housing crisis has been a big issue for years. Recently, it’s come to a head in part due to a few high-profile incidents, such as the death of a young woman in emergency accommodation. The number of children experiencing homelessness (around 4,000) has also shone a light on the severity of the issue. In this essay, Megan Nolan explores homelessness in Ireland as well as the contempt that society has for those who are unhoused.

Megan Nolan writes a column for the New Statesman. She also writes essays, criticism, and fiction. She’s from Ireland but based in London.

You may also like

13 Facts about Child Labor

Environmental Racism 101: Definition, Examples, Ways to Take Action

11 Examples of Systemic Injustices in the US

Women’s Rights 101: History, Examples, Activists

What is Social Activism?

15 Inspiring Movies about Activism

15 Examples of Civil Disobedience

Academia in Times of Genocide: Why are Students Across the World Protesting?

Pinkwashing 101: Definition, History, Examples

15 Inspiring Quotes for Black History Month

10 Inspiring Ways Women Are Fighting for Equality

15 Trusted Charities Fighting for Clean Water

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

Permanent Supportive Housing: Evaluating the Evidence for Improving Health Outcomes Among People Experiencing Chronic Homelessness (2018)

Chapter: 9 conclusions and recommendations, 9 conclusions and recommendations.

Homelessness, and especially chronic homelessness, is a highly complex problem that communities across the country are struggling to address. Despite the diligent efforts of federal agencies and nonprofit and philanthropic organizations to develop and implement programs to address the challenges of homelessness, the large number of Americans who continue to experience homelessness makes clear that much remains to be done to solve this pressing societal problem.

Permanent supportive housing (PSH) is a housing model designed to primarily serve individuals and families experiencing chronic homelessness, a population having different needs from those individuals and families who experience acute episodic or temporary homelessness. This committee was charged to examine the connection between PSH and improved health outcomes, addressing the primary question, “To what extent have permanent supportive housing programs improved health outcomes and affected health care costs in people experiencing chronic homelessness?” This chapter offers the committee’s overall conclusions about the evidence on the effect of PSH on health outcomes, as well as research and policy recommendations.

CONCLUSIONS

Evaluating the impact of psh on health: assessment and limitations of the evidence.

During the course of the study, the committee examined the published and unpublished literature and conducted a variety of other data-gathering efforts, including site visits. The committee found that interpreting the research relevant to PSH and health outcomes was challenging because, as discussed in the report, common terms have different meanings within and between homelessness lexicons used by various agencies, nongovernmental organizations, researchers, and advocates ( USICH, 2011 ). The lack of precise definitions of the housing models

reported upon and the paucity of detail about the exact nature and extent of supportive services provided in different housing models and in control or comparison groups further complicated the interpretation of reported findings.

In addition, data about PSH programs are generally siloed, uncoordinated, and fragmented. There are multiple barriers to collecting and sharing these data across agencies or programs, and there is a need for much greater interoperability of the data. The paucity of comparable data available across agencies makes it difficult to assess a variety of outcomes, and complicates efforts to provide the array of housing and social services that may be needed by individuals experiencing homelessness ( Culhane, 2016 ). See Chapter 8 for an in-depth discussion of related research gaps.

On the basis of currently available studies, the committee found no substantial evidence that PSH contributes to improved health outcomes, notwithstanding the intuitive logic that it should do so and limited data showing that it does do so for persons with HIV/AIDS. There are significant limitations in the current research and evidentiary base on this topic. Most studies did not explicitly include people with serious health problems, who are the most likely to benefit from housing. Of the studies that were more rigorous, the committee found that, in general, housing increases the well-being of persons experiencing homelessness.

The committee found no substantial published evidence that PSH improves health; however, PSH increases an individual’s ability to remain housed and plausibly alleviates a number of conditions that negatively impact health. However, few randomized controlled trials or other methodologically rigorous studies have evaluated the role of PSH in producing improved health outcomes. Consistent data in this regard are presently lacking. While the committee recognizes that there are moral and ethical reasons that make it problematic to carry out randomized controlled trials with this population, an overarching finding of this study is that more rigorous research is needed to determine how health outcomes per se are influenced by PSH. Different types of studies might pose fewer ethical concerns, such as stepped-wedge study designs, which are increasingly being used in the evaluation of health care research ( Simmons et al., 2017 ).

Housing has long been acknowledged as a key social determinant of health, and extensive literature has accumulated over the past two centuries showing that housing is foundational for good health. The United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Paris in 1948 in response to the devastation of World War II, declaring that the right to housing was among the rights to which all humans should be entitled. The United States was among the 48 signatories of this declaration. More recently, safe housing was noted as fundamental to the health of populations by the World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health ( CSDH, 2008 ).

While safe, secure, and stable housing contributes to good health, there is extensive literature also showing it is not sufficient. The quality and location of housing make a difference. Robust public health studies have shown the untoward health consequences of inadequate housing, including asthma, the spread of communicable diseases, exposure to toxins such as lead and radon, injuries, childhood

malnutrition, mental health conditions, violence, and the harmful effects of air pollution. Population studies have also shown that a person’s neighborhood matters a great deal with regard to health outcomes, with safe streets, safe schools, and economic opportunity essential for good health and well-being.

The committee acknowledges the importance of housing in improving health in general, but it also believes that some persons experiencing homelessness have health conditions for which failure to provide housing would result in a significant worsening of their health. Said differently, notwithstanding that housing is good for health in general, the committee believes that stable housing has an especially important impact on the course and ability to care for certain specific conditions and, therefore, the health outcomes of persons with those conditions. The committee refers to these conditions as “housing-sensitive” conditions and recommends that high priority be given to conducting research to further explore whether there are health conditions that fall into this category and, if so, what those specific conditions are. The evidence of the impact of housing on HIV/AIDS in individuals experiencing chronic homelessness may serve as a basis for more fully examining this concept. Chapter 3 describes the current research and the concept of housing-sensitive conditions in more detail.

Scaling Up PSH: Policy and Program Barriers

As part of its charge, the committee was asked to identify the “key policy barriers and research gaps associated with developing programs to address the housing and health needs of homeless populations.” While the committee found no substantial published evidence that PSH improves health, the intervention increases an individual’s ability to remain housed and that plausibly alleviates a number of conditions that negatively impact health. Based on its position that PSH holds potential for reducing the number of persons experiencing chronic homelessness and for improving their health outcomes, the committee describes the key policy and program barriers to bringing PSH and other housing models to scale to meet the needs of those experiencing chronic homelessness (discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7 ).

There are many barriers to bringing PSH to scale to meet the current level of need. As is often the case with housing and social service providers generally, PSH programs operate in an environment of scarcity with often inadequate and unreliable funding. The siloed nature of the programs and funding streams for PSH is an important barrier to scaling up. PSH providers working at the ground level to fulfill an already challenging mission are further challenged by the need to pool or braid together funding from multiple agencies and levels of government, each with its own requirements.

Multiple barriers also exist at the local level in meeting the need for PSH. As highlighted in the committee’s site visits in Denver and San Jose (see Appendix D ), operationalizing PSH programs is a very complicated and lengthy process, often taking many years to complete single-site projects. The high capital costs

and long development process are a substantive barrier to the replicability of successful programs. In the case of single-site PSH developments, myriad local land-use, permitting, and other regulatory barriers, which may be undergirded by prejudicial stereotypes and neighborhood opposition, makes land unavailable, leads to protracted delays, drives up development costs by as much as 20-35 percent, and generally impairs the efficiency of government assistance programs (see, e.g., van den Berk-Clark, 2016 ). Experts and government officials across the political spectrum have long recognized these barriers, but few of the many recommendations over the years for eliminating unnecessary regulatory barriers, streamlining processes, and more vigorously enforcing anti-discrimination laws have been implemented. Until such recommendations are effectively implemented, single-site PSH will not be a sufficient answer to address the need.

Scattered-site approaches, which generally make use of Housing Choice Vouchers (HCV) to lease existing housing stock, avoid some of the barriers relevant to single-site PSH and appear to offer promise for scaling up PSH in a shorter time. But scattered-site programs also face challenges when operating in high-priced housing markets and markets where state and local laws allow property owners to refuse to accept vouchers. It also can be more difficult for residents to access supportive services when not directly available on-site. Moreover, federal funding for the HCV program has been at best stable and at worse declining, forcing PSH providers and clients to compete with others on long waiting lists for vouchers.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee developed the following recommendations based on its assessment of the evidence that it hopes will guide research and federal action on this issue. The recommendations flow from the specific questions posed to the committee in the statement of task, including research needs related to assessing PSH and health outcomes, the cost-effectiveness of PSH, and key policy and program barriers to bringing PSH and other housing models to scale to meet the needs of those experiencing chronic homelessness.

Recommendation 3-1: Research should be conducted to assess whether there are health conditions whose course and medical management are more significantly influenced than others by having safe and stable housing (i.e., housing-sensitive conditions ). This research should include prospective longitudinal studies, beyond 2 years in duration, to examine health and housing data that could inform which health conditions, or combinations of conditions, should be considered especially housing sensitive. Studies also should be undertaken to clarify linkages between the provision of both permanent housing and supportive services and specific health outcomes. (See Chapter 3 .)

Recommendation 3-2 : The Department of Health and Human Services, in collaboration with the Department of Housing and Urban Development, should call

for and support a convening of subject matter experts to assess how research and policy could be used to facilitate access to permanent supportive housing and ensure the availability of needed support services, as well as facilitate access to health care services. (See Chapter 3 .)

Recommendation 4-1: Incorporating current recommendations on cost-effectiveness analysis in health and medicine ( Sanders et al., 2016 ), standardized approaches should be developed to conduct financial analyses of the cost-effectiveness of permanent supportive housing in improving health outcomes. Such analyses should account for the broad range of societal benefits achieved for the costs, as is customarily done when evaluating other health interventions. (See Chapter 4 .)

Recommendation 4-2: Additional research should be undertaken to address current research gaps in cost-effectiveness analysis and the health benefits of permanent supportive housing. (See Chapter 4 .)

Recommendation 5-1: Agencies, organizations, and researchers who conduct research and evaluation on permanent supportive housing should clearly specify and delineate: (1) the characteristics of supportive services, (2) what exactly constitutes “usual services” (when “usual services” is the comparator), (3) which range of services is provided for which groups of individuals experiencing homelessness, and (4) the costs associated with those supportive services. Whenever possible, studies should include an examination of different models of permanent supportive housing, which could be used to elucidate important elements of the intervention. (See Chapter 5 .)

Recommendation 5-2: Based on what is currently known about services and housing approaches in permanent supportive housing (PSH), federal agencies, in particular the Department of Housing and Urban Development, should develop and adopt standards related to best practices in implementing PSH. These standards can be used to improve practice at the program level and guide funding decisions. (See Chapter 5 .)

Recommendation 7-1: The Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Health and Human Services should undertake a review of their programs and policies for funding permanent supportive housing with the goal of maximizing flexibility and the coordinated use of funding streams for supportive services, health-related care, housing-related services, the capital costs of housing, and operating funds such as Housing Choice Vouchers. (See Chapter 7 .)

Recommendation 7-2: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should clarify the policies and procedures for states to use to request reimbursement for allowable housing-related services, and states should pursue opportunities to ex-

pand the use of Medicaid reimbursement for housing-related services to beneficiaries whose medical care cannot be well provided without safe, secure, and stable housing. (See Chapter 7 .)

Recommendation 7-3: The Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, working with other concerned entities (e.g., nonprofit and philanthropic organizations and state and local governments) should make concerted efforts to increase the supply of PSH for the purpose of addressing both chronic homelessness and the complex health needs of this population. These efforts should include an assessment of the need for new resources for the components of PSH, such as health care, supportive services, housing-related services, vouchers, and capital for construction. (See Chapter 7 .)

Chronic homelessness and related health conditions are problems that require an appropriate multidimensional strategy and an ample menu of targeted interventions that are premised on a resolute commitment of resources. More precisely defined and focused research to refine the menu of needed interventions, and a materially increased supply of PSH are part of the multidimensional strategy. The committee hopes that this report will help to stimulate research and federal action to move the field forward and further efforts to address chronic homelessness and improved health in this country.

Chronic homelessness is a highly complex social problem of national importance. The problem has elicited a variety of societal and public policy responses over the years, concomitant with fluctuations in the economy and changes in the demographics of and attitudes toward poor and disenfranchised citizens. In recent decades, federal agencies, nonprofit organizations, and the philanthropic community have worked hard to develop and implement programs to solve the challenges of homelessness, and progress has been made. However, much more remains to be done. Importantly, the results of various efforts, and especially the efforts to reduce homelessness among veterans in recent years, have shown that the problem of homelessness can be successfully addressed.

Although a number of programs have been developed to meet the needs of persons experiencing homelessness, this report focuses on one particular type of intervention: permanent supportive housing (PSH). Permanent Supportive Housing focuses on the impact of PSH on health care outcomes and its cost-effectiveness. The report also addresses policy and program barriers that affect the ability to bring the PSH and other housing models to scale to address housing and health care needs.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

- Arts & Humanities

Homelessness: Conclusion Study

15 Jan 2023

- Arts & Humanities

Format: MLA

Academic level: High School

Paper type: Essay (Any Type)

Downloads: 0

- Homelessness Essays

Homelessness is a social problem that requires a national approach for it to have a lasting solution. Although many societal and public policy approaches have been enacted to address the problem, it remains a major social issue that the United States is struggling to address. Despite the efforts by government agencies and non-profit organizations working hard towards the eradication of the problem with notable results, the problem remains strong. However, homelessness has been effectively managed among veterans, and the same can be replicated in other groups that are dealing with homelessness. Every society has its unique reasons or issues that result in people becoming homeless, although some of them are common. One of the standard solutions to the problem of homelessness needs to be the provision of housing for those who are genuine.

Homelessness cannot be defined based on only one factor. There is a complex mixture of societal and individual factors that contribute to homelessness. Some of the individual factors associated with homelessness have an impact on a substantial percentage of the population. Some of these factors are related to mental illness, substance abuse, and addition. Any attempt to deal with the problem of homelessness has to first deal with individual factors. The analysis shows that there are people who are not genuinely homeless, as they have attained the status because of individual choices that reduce their productivity in society. In regards to societal causes, some of the ways that society has affected homelessness revolves around the increase in house prices and a decrease in funding. Another problem that escalates the problem and affects any attempt to eradicate the problem is public opinion. When public opinion shifts, polices and media follows reading to the varying response from the stakeholders. The shifting of public opinion may lead to resistance or acceptance of the proposed solutions. Solutions to homelessness do not have to be worth many funds as they can be community-based before expansion to cover larger audiences. Starting with a community gives room for evaluation and effective alteration to increase the chances of success.

Delegate your assignment to our experts and they will do the rest.

There needs to be a multi-sector approach to attaining long-term solutions for homelessness. The first step is to prevent homeless by reducing the risk of housing crises in the first place. Families living in shelters or in makeshift places face barriers to functioning as families. Strategies to reduce the risk of homelessness should be done to ensure adequate and secure housing in order for families to function as a family. These strategies should mainly focus on the strengths as well as the participation of the families. Federal housing programs for homeless individuals have been proven to be one of the most effective methods in managing homelessness. The strategy’s focus ranges from landlord engagement, affordable housing, rapid re-housing, and supportive housing. The provision of health care is another solution that helps in reducing the risk of homelessness. People with chronic health usually affect the ability of individuals to remain housed. Having comprehensive health care deals with the risk of homelessness for those with chronic health issues. The government and other organizations need to focus on building career pathways as people are assisted in moving from homelessness to permanent housings. Job training and employment ensures that individuals make a living that reduces the chances of them returning to homelessness. Children of homeless individuals are more prone to facing challenges such as lagging behind in education, and fostering education should be an integral part of the strategy.

- The United States has the world's largest prison population

- Come out of the Wilderness Reflection

Select style:

StudyBounty. (2023, September 14). Homelessness: Conclusion Study . https://studybounty.com/homelessness-conclusion-study-essay

Hire an expert to write you a 100% unique paper aligned to your needs.

Related essays

We post free essay examples for college on a regular basis. Stay in the know!

The Downfalls of Oedipus and Othello

Words: 1402

Why I Want To Become a Physician

The perception of death in the play "everyman".

Words: 1464

How to Reverse Chronic Pain in 5 Simple Steps

Words: 1075

“Boyz n the Hood” director and Auteur Theory paper

Free college and university education in the united kingdom, running out of time .

Entrust your assignment to proficient writers and receive TOP-quality paper before the deadline is over.

Why Homelessness Still Exists and How We Can End It

The Official Blog of the National Alliance to End Homelessness

By Jeff Olivet, Executive Director, U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness

When one person—even one—dies on the street, we as a society have failed them. When one family seeking safe housing and a stable school for their children is discriminated against by a landlord, we have failed them. When one young queer person of color ages out of foster care with no place to go, or when one person completes a sentence and leaves prison only to end up in a shelter, we have failed. When one Veteran returns from serving this country and ends up homeless, we have failed.

I believe we can do better.

Over the last several decades, our public policies have allowed homelessness to persist. We have created homelessness on a systemic level—a societal level—and on a scale we have not witnessed since the Great Depression. Yet we try to solve it at the individual level. And we have gotten very good at that part of the picture. Effective housing and service interventions like Housing First, Critical Time Intervention, and others have helped hundreds of thousands of people exit homelessness over the past decade.

So why does homelessness still exist? Is it because what we are doing isn’t working? Absolutely not.

We have developed systems that are increasingly efficient in helping people move from homelessness to the stability and connection of a permanent home. We see these success stories every day. It is what inspires us to continue in this challenging work.

So what are we not doing right?

One problem is that we haven’t scaled effective solutions to meet the demand. Another is that we haven’t held ourselves and our communities accountable to the goal of ending homelessness. We too often measure ourselves by outputs rather than outcomes. We haven’t gone upstream to stem the tide of people becoming newly homeless. And we haven’t yet figured out how to address the underlying root causes of homelessness, including the dual crises of housing affordability and eviction, and the persistent structural racism that drives disproportionately high rates of homelessness for people of color.

The result is that even as we see individual successes all the time—tens of thousands of people every year exiting homelessness, holding down jobs, reconnecting with family and friends, stepping strongly into courageous journeys of recovery from mental health and substance use issues— we have not solved homelessness systemically . It is time that we do just that.

A systemic end to homelessness will require:

- Leading with equity , so that even as we work for an end to all homelessness for all people, we use strategies specifically designed to eliminate racial disparities.

- Grounding our policy decisions in accurate, real-time data, and sound evidence , so that we are making the best use of the resources we have. Until we have a clearer picture of the scope of the problem, it is impossible to understand the scope of resources needed to solve it.

- Going upstream to stem inflow and prevent homelessness from ever happening in the first place. This will require focused, cross-sector collaboration at the federal, state, and local levels in a way that we have not done before.

- Strengthening our crisis response system to address unsheltered homelessness, encampments, and barriers to shelter, so that people stay alive long enough to get back into housing and supports.

- Scaling effective housing solutions , with the recognition that housing is the stable foundation from which individuals, families, young people, seniors, and Veterans can achieve health, wellness, and connection.

- Providing a broad range of supportive services —from mental health and substance use treatment to employment and educational supports to childcare and transportation to direct cash transfers—so that people can sustain themselves in permanent housing.

In the coming months, the team from the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) will release our federal strategic plan to guide the work of preventing and ending homelessness in the U.S. The plan will reflect what we heard from many of you through nearly 100 listening sessions that included many individuals who themselves have experienced the horrors of homelessness.

As we finalize the plan and roll it out, we will need your help putting it into action.

The work ahead will be difficult, but it will not be impossible. If we can imagine a better, more humane society , a society in which no one is left behind and no one is without a home, then we can build toward that vision. We must come together—housed and unhoused, Republicans and Democrats, government agencies and nonprofits, faith communities and corporations, people of all racial/ethnic backgrounds and all gender expressions and sexual orientations. We must come together to find common ground around the shared goal of ending homelessness once and for all.

We have a long road ahead. Remember to take care of yourselves and take care of each other. Find joy in the daily victories. Stay focused, stay strong, and stay engaged until homelessness is a relic of the past, a faded memory.

Privacy Overview

Homelessness - Free Essay Samples And Topic Ideas

Homelessness is a social issue characterized by individuals lacking stable, safe, and adequate housing. Essays on homelessness could explore the causes, such as economic instability, mental health issues, or systemic problems, and the societal impacts of homelessness. Discussions may also cover various solutions and strategies being employed by different regions to address homelessness and support the affected populations. A substantial compilation of free essay instances related to Homelessness you can find at Papersowl. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Effects of Homelessness and Student Academic Achievement

Supporting and understanding the differing at-risk students, especially students experiencing homelessness, in the classroom is an important aspect of being an educator. Teachers are often seen as important referents in a community. The ways that teachers interact with homeless children and families convey important messages to children and families. Teacher views about children and families can indeed foster feelings of worthiness or the lack thereof (Powers-Costell & Swick, 2011 p.208). For teachers to teach these at-risk students, they must fully […]

Substance Abuse and Homelessness

Homelessness is becoming a more and more prevalent issue in America as years progress. Drive through any city's downtown area and you're bound to see at least one, if not many more, homeless individuals or families residing along the streets or in homeless camps. In many cases, these people have been suffering from homelessness for years and this has simply become their norm; this is known as chronic homelessness. Although this has become a way of life for many, homelessness […]

Veterans: Fight for Freedom and Rights

Veterans have sacrificed so much for our country by fighting to maintain our freedom and rights. For this reason, the government should do something about the veterans poverty rate. Veterans have resources that they could use but the resources do not always reach out to the veterans in need. The rate of homeless veterans is very high compared to non-veterans in the United States because they were usually not ever taught how to write a resume and many have had […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

My Opinion about Homelessness

My opinion is based on what I see and encounter and also from research. Homelessness. Homeless people did not choose the lifestyle on purpose, misfortune made the choice for them consequently they should be generously assisted kind heartedly without social isolation, pity, job insecurities, humiliation, pitiful wages e.t.c. Learning by choice or pain, which would you rather settle with? Unique story. Every person who has become homeless has a unique story about what happened to them. I can fill these […]

Homelessness and Mental Illness

Research problem: Homelessness Research question: Why is the mental health population and people with disabilities more susceptible to becoming homeless? Mental health policies that underserve vulnerable people are a major cause of homelessness. The deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals, including the failure of aftercare and community support programs are linked to homelessness. Also, restrictive admission policies that keep all but the most disturbed people out of psychiatric hospitals have an effect on the rising number of homeless people. The New York […]

Homeless Veterans

From bullet shells, to bomb blasts, and potentially amputated limbs, U.S. soldiers face on the scariest and life threatening situations no man or woman could ever imagine. America's military is one of the strongest forces in the world and consists of the toughest and strongest men and women in the US. These soldiers have risked their lives, lost limbs, their friends, their family, and their lives. The bravery and honor that any soldier musters up to go into battle can […]

Homelessness Problem in LA

Homelessness in LA is not an isolated case in U.S but rather public issue from 1980s since represents a huge problem for several cities as well as for largely populated states. People are facing this problem in daily basis; every time we are waiting by the traffic lights on the street, homeless people approaches to us and ask us either for a food or a change. Homeless people are people who are without a home and therefore living on the […]

The Causes of Homelessness

Homelessness has been a problem in American society for many generations. There are countless amounts of people who live without a permanent home and lack the basic essentials of life, such as food,wds `1ater, and clothes. It is likely when you walk or drive in your city that you will encounter a homeless person. Often when you are passing by a homeless individual or group, the thought comes to your mind, how did the end up here? Or why or […]

How Poverty Affects a Child’s Brain and Education

Although children are some of the most resilient creatures on earth. Living in poverty has risks that can cause children all types of issues. That makes you wonder, does poverty have an effect on a child's brain development? The million dollar question. How does poverty affect children's brain development? Poverty can cause health and behavioral issues. There is suggestive evidence that living in poverty may alter the way a child's brain develops and grows, which can, in turn, alter the […]

Unemployment a Major Cause of Homelessness

Homelessness or known as extreme poverty can be interpreted as a circumstance when people have no place to stay with the result that they end up live in the street, under the bridge even at the side of the river. There are 3.5 million Americans are homeless each year. Of these, more than 1 million are children and on any given night, more than 300,000 children are homeless. They who do not have an occupation are the one that is […]

Homelessness is not a Choice

Homelessness is not a choice an individual makes but is a result of poverty, unemployment, and lack of affordable housing. Many homeless people come from a loving family, and at one point in their life, they had jobs and homes. Economic and social challenges cause them to suffer and make bad life choices which lead them down the road of homelessness. Back then, families looked after their unfortunate ones and supported them when they lost their jobs, faced economic issues […]

Closing the Education Gap by Attacking Poverty Among Children

Looking around the campus of an Ivy League schools, one wonders how students from such diverse backgrounds ultimately wound up at the same place. From having a mother who works in admissions, I grew up hearing that no matter where you came from, your socioeconomic status, and even sometimes your grades, all kids have the potential to attend a prestigious university. However, I find that hard to believe. With a combination of taking this class on homelessness this semester, growing […]

Homelessness in the United States

Homelessness is a social problem that has long plagued the United States and surrounding Countries for centuries. It is an economic and social problem that has affected people from all walks of life, including children, families, veterans, and the elderly. Kilgore (2018). States homelessness is believed to have affected an estimated amount of 2.5-3.5 million people each year in the United States alone. Recent evidence suggests economic conditions have increased the number of people affected by homelessness in the United […]

Youth Homelessness in the United States

Imagine having to live on the streets, in unbearable conditions, never knowing what it is like to be in a stable environment. This presents many challenges faced by children as young as a few months old. These challenges are faced by some of the more than 500,000 children (Bass 2017). These children do not have anywhere to call home and very little resources to help them a place to live. These numbers of homeless youth are increasing making it harder […]

Homelessness in Hometown

Huntsville, Tx is a city with a high rate in population growth and homelessness is an issue that is over looked. There are many people without a home or low incomes which makes them inclined to stress and fall under poverty level. There are individuals and families that cannot afford to purchase groceries, or toiletries for their families. Everyone can get a job and maintain middle class status, but there is a great amount of people that have jobs and […]

Homelessness Policy in the United States

The logic behind the previous and current strategy of state-funded and driven housing policy improvement is that by allowing cities and states to control and determine policy fitting their specific needs, there will be more room for innovative strategies for complex problems. The affordable housing struggle of 2018 is different from those of the 1960s or 1980s, and its solution may require a more creative solution than federal vouchers and subsidies equally applied based on income. In a world of […]

America is Suffering from Poverty

United states of America haves a population of 325.7 million people. As Americans we love Sunday night football, Drake concerts, watching Donald Trump run our country into a hole andoursocial networks. Although we have several interests we cannot let it entertain us from the fact that America is suffering from poverty. Poverty is the state of being awfully poor. What decent country puts more focus on their Instagram poststhan their bank account funds? According to World Bank, in 2013 769 […]

Homelessness cannot be Solved Overnight

Homelessness is a very difficult subject to talk about for many people. A lot of people know someone who is either currently homeless or has been homeless before and is no longer homeless, so this topic may really hit home for them. Other people may not have direct experiences with homeless people unless they see them in public. It can be very difficult to know how to act when you see a homeless person in public that you have never […]

The Issue of Homelessness

James Harris always begins with “God bless you” before asking for money. He hates asking people for anything, so this three-word phrase serves as his own offering. Harris, a veteran, has had AIDS for thirty years. When the medication stopped working, the world began to crumble around him. He became depressed and was ultimately evicted from his place in Hollywood. “I’ve been beaten, robbed, and chased, he said. “People steal your tents and your tarps and your clothes. I’ve lost […]

Homelessness in San Gabriel Valley

Los Angeles County has seen a slight decline in homelessness since the 2017 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count. The data is comprised every year by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. Volunteers would go out and count individuals who are unsheltered. The rest of the individuals counted come from shelters or those living out of cars, vans or tents. The 2018 data shows that there is a total of 52,765 in Los Angeles County compared to the 55,048 that were […]

What Can we do to Fix Homelessness?

Agrawal, Nina. L.A. County Declares a Shelter Crisis, Providing Flexibility in How It Provides Beds and Assistance. Los Angeles Times, 30 Oct. 2018, www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-board-homeless-shelter-declaration-20181030-story.html. A shelter crisis was declared on October 30, 2018. This called for the Los Angeles Homeless Service Authority to have be allowed to spend $81 million in a more flexible way. Declaring a shelter crisis allows the homeless ability to bypass some regulations and get access to emergency housing. This also gives the flexibility to spend […]

Suicidality in Transgender Teens

Gender identity is defined as one’s sense of being a male, female, or other gender. It is the individual’s own connection to their gender which defines who they are. Many people feel as if the sex they were born with does not match with the gender they identify with. In many cases, people may identify as transgender. Transgender individuals believe, “the sex assigned at birth is discordant with their gender identity” (Sitkin & Murota, 2017, p. 725). An example of […]

The Trauma of Homelessness

It's the age-old question, the chicken or the egg, and how do you serve it best? In this case what came first, being homeless or Post-Traumatic Stress disorder, and how do you end it? Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and homelessness can create a cycle that feeds on itself. The act of becoming homeless in itself can act as a catalyst for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, while also being caused by it. Permanent sustainable housing has proven to be effective in addressing both […]

Extra Credit Solutions to Homelessness: Sociological Vs Individualistic Views

The contemporary social problem I have choose to discuss is homelessness throughout our country. As of 2017, 554,000 people were reported to be homeless. People who are homeless are unable to maintain housing, and usually have income. Homelessness can be hereditary, or self-imposed, the reasons people are homeless differ between their personal life stories of how they got there. This number has increased since previous years making homelessness a major issue in our country, especially in large cities such as […]

The Consequences of Homelessness – a Childhood on the Streets

“A therapeutic intervention with homeless children (2) often confronts us with wounds our words cannot dress nor reach. These young subjects seem prey to reenactments of a horror they cannot testify to” (Schweidson & Janeiro 113). According to Marcal, a stable environment and involved parenting are essential regarding ability to provide a healthy growing environment for a child (350). It is unfortunate then, that Bassuk et al. state that 2.5 million, or one in every 30 children in America are […]

Homelessness in America

Life brings along a lot of good and bad affairs. However, we try to focus on the good that brings us happiness. Experience sometimes tends to ruin the good times. One of the bad affairs that society today faces is homelessness. Homelessness can be defined as not having a fixed roof over one's head or living in temporary accommodation under the threat of eviction[1]. This paper focuses on societal views to try to explain the issue of homelessness in the […]

Mental Disorders Among Homeless Veterans

There have been many studies performed over the past several years to test the theory of why veterans who suffer from mental and/or substance use disorders have a higher possibility of becoming homeless. Those studies also included the impact of war and combat as well as several risk factors while our veterans served in the military. The road that leads to homelessness if often left untreated and further complicates treatment and therapy to fix the underlying issues. There are several […]

Poverty and Homelessness in America

Poverty and Homelessness in America is a daunting subject which everyone recognizes but do not pay attention to. A homeless person is stereotypically thought to be a person who sleeps at the roadside, begging for money and influenced by drug with dirty ragged clothes and a person who is deprived of basic facilities in his or her life such as; education, electricity, proper clothes, shelter, water with a scarcity of balanced diet is termed as person living under the line […]

Addressing Homelessness Lie

According to recent studies, about 150 million people worldwide are homeless. It is estimated that another 1.6 billion people live in inadequate housing conditions. This means that about 20% of the world's population suffers from poor housing conditions, homelessness or from the danger of becoming homeless. Poverty is a big reason when it comes to homelessness. If people have debts and don't have a suitable job to pay them off, they may lose their homes as they won't be able […]

Mental Illness is One Type of Homelessness

'Poverty is not an accident. Like slavery and apartheid, it is man-made and can be removed by the actions of human beings', an unforgettable quote by the man himself Nelson Mandela. For his fight against racial prejudice and apartheid, Nelson leaves a towering legacy that will be recalled for generations to come. But, today's world is pervaded with the good and the evil. There are those that assist to keep a relatively-stable society; and then there are those who just […]

Additional Example Essays

- Socioautobiography Choices and Experiences Growing up

- A Class Divided

- Gender Inequality in Education

- End Of Life Ethical Issues

- The Oppression And Privilege

- Macbeth Downfall in the Context of Violence

- Arguments For and Against Euthanasia

- Catherine Roerva: A Complex Figure in the Narrative of Child Abuse

- "Just Walk on" by Brent Staples Summary: Racial Stereotypes and Their Impact

- Why Abortion Should be Illegal

- Logical Fallacies in Letter From Birmingham Jail

- How the Roles of Women and Men Were Portrayed in "A Doll's House"

How To Write an Essay About Homelessness

Understanding the complexity of homelessness.

Before beginning an essay on homelessness, it's essential to understand its complexity. Homelessness is not just the absence of physical housing but is often intertwined with issues like poverty, mental health, substance abuse, and social exclusion. Start your essay by defining homelessness, which may vary from sleeping rough on the streets to living in temporary shelters or inadequate housing. It's also important to acknowledge the different demographics affected by homelessness, such as veterans, families, the youth, and the chronically homeless. This foundational understanding sets the stage for a nuanced discussion in your essay.

Researching and Gathering Data

An essay on homelessness should be grounded in factual, up-to-date data. Research statistics from reliable sources such as government reports, reputable NGOs, and academic studies. This research might include figures on the number of homeless individuals in a specific region, the primary causes of homelessness, and the effectiveness of various intervention programs. By presenting well-researched information, your essay will not only be more credible but will also provide a factual basis for your arguments.

Selecting a Specific Angle

Homelessness is a broad topic, so it's crucial to select a specific angle for your essay. You might choose to focus on the causes of homelessness, the challenges faced by homeless individuals, or the societal impact of homelessness. Alternatively, you could discuss policy solutions and interventions that have been successful or have failed. This focus will provide your essay with a clear direction and allow you to explore a particular aspect of homelessness in depth.

Analyzing Causes and Effects

A key part of your essay should be dedicated to analyzing the causes and effects of homelessness. Discuss various factors that lead to homelessness, such as economic downturns, lack of affordable housing, family breakdown, and mental health issues. Similarly, explore the impact of homelessness on individuals and society, like health problems, social isolation, and economic costs. This analysis will help readers understand the multifaceted nature of the problem.

Discussing Solutions and Conclusions

Towards the end of your essay, discuss potential solutions to homelessness. This could include government policies, community-based initiatives, or innovative approaches like housing-first models. Highlight the importance of a multi-faceted approach, addressing not just the lack of housing but also underlying issues like health care, education, and employment support. Conclude your essay by summarizing the key points discussed, restating the importance of addressing homelessness, and suggesting areas for future research or action.

Finalizing Your Essay

After writing your essay, take the time to review and refine it. Ensure that your arguments are coherent and supported by evidence. Check for grammatical errors and ensure that your writing is clear and concise. It might also be beneficial to get feedback from peers or instructors. A well-written essay on homelessness will not only inform but also potentially inspire action or further discussion on this critical social issue.

- Open access

- Published: 16 September 2024

Social isolation and loneliness among people living with experience of homelessness: a scoping review

- James Lachaud 1 , 2 ,

- Ayan A. Yusuf 2 ,

- Faith Maelzer 2 , 3 ,

- Melissa Perri 2 , 4 ,

- Evie Gogosis 2 ,

- Carolyn Ziegler 5 ,

- Cilia Mejia-Lancheros 2 , 6 &

- Stephen W. Hwang 2 , 4 , 7

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 2515 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Social isolation and loneliness (SIL) are public health challenges that disproportionally affect individuals who experience structural and socio-economic exclusion. The social and health outcomes of SIL for people with experiences of being unhoused have largely remained unexplored. Yet, there is limited synthesis of literature focused on SIL to appropriately inform policy and targeted social interventions for people with homelessness experience. The aim of this scoping review is to synthesize evidence on SIL among people with lived experience of homelessness and explore how it negatively impacts their wellbeing. We carried out a comprehensive literature search from Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and Web of Science's Social Sciences Citation Index and Science Citation Index for peer-reviewed studies published between January 1st, 2000 to January 3rd, 2023. Studies went through title, abstract and full-text screening conducted independently by at least two reviewers. Included studies were then analyzed and synthesized to identify the conceptualizations of SIL, measurement tools and approaches, prevalence characterization, and relationship with social and health outcomes. The literature search yielded 5,294 papers after removing duplicate records. Following screening, we retained 27 qualitative studies, 23 quantitative studies and two mixed method studies. SIL was not the primary objective of most of the included articles. The prevalence of SIL among people with homelessness experience varied from 25 to 90% across studies. A range of measurement tools were used to measure SIL making it difficult to compare results across studies. Though the studies reported associations between SIL, health, wellbeing, and substance use, we found substantial gaps in the literature. Most of the quantitative studies were cross-sectional, and only one study used health administrative data to ascertain health outcomes. More studies are needed to better understand SIL among this population and to build evidence for actionable strategies and policies to address its social and health impacts.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Social isolation and loneliness (SIL) are major social and health issues representing a growing global public health challenge, particularly for socio-economically excluded and underserved populations [ 1 , 2 ]. Social isolation is defined as a lack of close or meaningful relationships and results from multidimensional experiences associated with exclusion from mainstream society, hopelessness, abandonment, social marginalization, lack of community networks and dissatisfaction with relationships [ 3 , 4 ]. Loneliness is a more personal and subjective multifaceted experience consisting of different types of self-perceived social deficits, including social loneliness, defined as a self-perceived lack of friendships in either quality or quantity and emotional loneliness, experienced as a deficit of intimate attachments such as familial or romantic relationships or feeling alone and isolated [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

SIL has been linked to putting people at increased risk for adverse health outcomes, social distress and premature death [ 6 ]. Lack of adequate social support has been reported to increase the odds of premature death by 50% [ 6 ]. Previous studies have also found an association between SIL and increased risk of developing dementia, coronary heart disease and stroke, poorer mental and cognitive health outcomes, and consumption of a low-quality diet [ 7 , 8 ]. While SIL affects many populations, individuals with experiences of being unhoused are among those with the highest risk of being socially isolated and lonely. First, experiences of homelessness are visible and extreme forms of social exclusion. Unhoused people are more socially disconnected, can feel rejected or abandoned, and may not have appropriate informal (family, relatives, friends) and formal support networks [ 9 , 10 ]. Second, even after being housed, structural forms of oppression (i.e., racism) and discrimination associated with previous experiences of being unhoused continue to impact individuals’ lives and deprive people of meaningful recovery and social integration, connection and relationships [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Individuals who have experienced homelessness often face persistent stigma and discrimination that can affect their social interactions and access to essential services [ 12 ]. People with experiences of being unhoused have self-reported higher odds of poor mental and physical health and loneliness than their housed counterparts [ 14 ]. Moreover, people with experiences of being unhoused have lower life expectancy and experience impairments associated with aging earlier compared with people without experiences of being unhoused [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. These factors can make individuals more vulnerable to social and economic abuse, which may affect their ability to build meaningful social connections.

Recent years have seen increased initiatives to address SIL among formerly homeless populations. There is some consensus in social work to consider SIL in needs assessments for health and social care for some specific population groups, such as seniors and youth [ 18 , 19 ]. More resources are being allocated to address SIL in supportive housing programs and intervention design [ 20 ]. Social prescribing, which involves primary care physicians prescribing social activities to patients as a strategy to strengthen social engagement and lower loneliness, is becoming a growing practice [ 21 , 22 ]. Nonetheless, SIL remains complex to conceptualize, and it has been difficult to measure its prevalence and association with social and health outcomes and other indicators of wellbeing. Without a clear conceptualization and measurement approach, it is uncertain how to design adequate interventions and policies to address SIL.

The aim of this scoping review was to identify, map, and synthesize the findings of qualitative and quantitative studies that measure SIL among people over the age of 18 with lived or living experience of homelessness including those living in supportive or social housing, or staying in emergency or transitional accommodation in order to highlight the gaps in the existing literature and inform the development of future interventions. This scoping review will aim to answer the following questions:

How are SIL conceptualized across studies involving people with experience of homelessness?

What scales and tools are used to measure SIL across these studies?

What is the prevalence of SIL and the relationship between SIL and social and health outcomes in people with experience of homelessness?

Data sources and searches

The scoping review protocol followed the methodology outlined by Arksey and O’Malley, Levac et al. [ 18 ] and is guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA ScR) [ 23 ]. Initially, a preliminary search was performed in Medline and Embase to identify any existing scoping reviews related to the topic, and to refine the search strategies by pinpointing key concepts and determining an appropriate timeframe to include relevant studies [ 24 ]. Then, comprehensive literature searches were carried out by an information specialist (CZ) in Medline (Ovid platform), Embase (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials & Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), and Web of Science's Social Sciences Citation Index and Science Citation Index. The search strategies had a broad range of subject headings and keywords, adapted for each database, for the two core concepts of SIL and homelessness or social housing, combined with the Boolean operator AND. The searches were limited to articles in English, French, and Spanish published between January 1st, 2000 to October 27, 2021, followed by an updated search to January 3rd, 2023. The publication languages were chosen for feasibility purpose, considering the linguistic capacity of the research team. Comments, editorials, and letters were excluded from the search. There were a total of 8,398 results from these two rounds of searches prior to de-duplication (7,356 at search one and 1,042 at search two) and the records were compiled in EndNote. The complete search strategies as run are included in the Supplementary material .

Definition and screening process

To refine our screening process, we defined individuals experiencing homelessness as those lacking stable, safe, permanent, and appropriate housing, or the immediate means and ability to acquire such housing [ 25 ]. This definition encompasses individuals who are marginally housed or at high risk of eviction, including individuals who are "doubled up," couch surfing, or living in overcrowded conditions [ 26 ].

To be considered eligible for inclusion, we established the following inclusion criteria for the scoping review:

studies had to include participants that were people with homelessness experience or marginally/vulnerably housed populations (people living in supportive housing or shelters). While our screening process did not establish an age criterion, we excluded studies that focused exclusively on minors (under 18 years old) experiencing homelessness. This decision was made as a recent study showed that minors experiencing homelessness might need specific considerations and theoretical framework [ 27 ];

studies had to be peer-reviewed qualitative and quantitative original research papers published in English, French, or Spanish;

studies had to be published between 2000-and January 3, 2023;

studies had to examine or include in the analyses: loneliness, social isolation, social disconnection, solitude, social withdrawal, abandonment, lack of contact, social exclusion or rejection.

We excluded papers that were systematic or scoping reviews, and papers where the studied populations was exclusively minors; where the field activities and data were collected from caregivers or other workers, and not people with homelessness experience or marginally/vulnerably housed; studies that only focused on networking, social or community integration and did not refer to social isolation or loneliness. No exclusion was made based on geographic region or countries, however we excluded studies that focused on people residing in camps due to displacement from war, insecurity, or major natural disasters, as these situations are typically addressed by different theoretical and humanitarian frameworks [ 28 ].

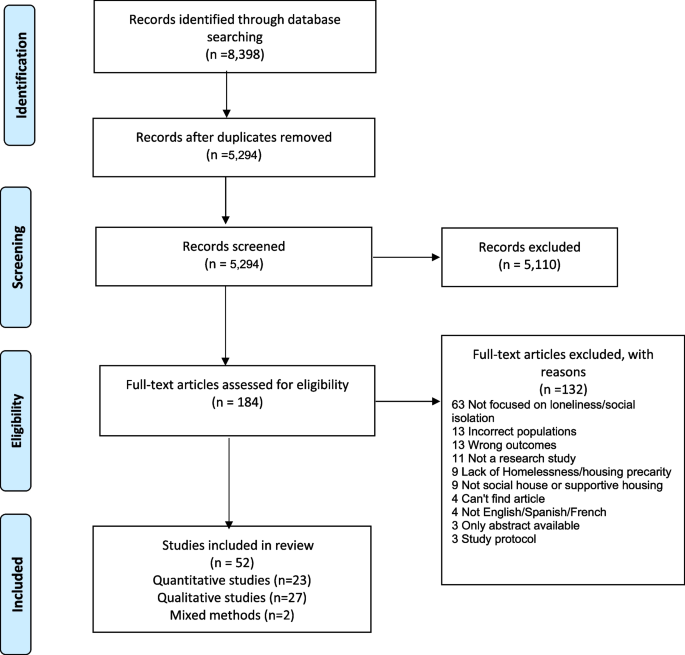

The results from all searches were imported to Covidence systematic review software, where duplicates were removed. The searches yielded 5,294 papers for screening after the deletion of duplicates. Four researchers (AY, EG, FM, and MP) screened the article titles and abstracts independently and in duplicate in Covidence using the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full-text of the articles that met our eligibility criteria were then assessed by two independent reviewers. At both stages, differences in voting were discussed and resolved as a group, and included the Principal Investigator (JL). In total, 52 articles met the criteria for data extraction and analyses. The PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1 shows the flow of information through the different stages of the review.

PRISMA flow diagram

Data extraction

The main characteristics, research questions, targeted populations, measurement and findings of the selected studies were extracted in an Excel database file by the four researchers (AY, EG, FM, and MP) and reviewed by the Principal Investigator (JL). A summary of each selected paper can be found in Tables 1 and Table 2 .

Data synthesis

The studies reviewed exhibited considerable variability in their methodological approaches, participant demographics (including young adults, adults, and seniors) or sex and gender-based groups, measures of SIL, definitions of homelessness experience, and countries where they were conducted. To provide a thorough overview, we examined both quantitative and qualitative research. Initially, we assessed the theoretical frameworks used in these studies to better grasp the conceptualization and ongoing discussions about SIL within the target population. In our analysis of quantitative studies, we identified key similarities and differences in SIL measurements, demographic characteristics, discussions of the prevalence and patterns of SIL and its relationship with health status. To deepen our understanding, we used a crosswalk approach [ 29 ] using both quantitative and qualitative studies to examine how participants described, contextualized, and nuanced their experiences of SIL, and how SIL related to demographic factors, gender, and homelessness experience.

Overview of included studies

The main characteristics of the 52 articles included in this review are outlined in Tables 1 and Table 2 . Most articles (n = 42) were published from 2010 and later and were conducted in the US (n = 16) and Canada (n = 16). Study methodology was almost evenly split between quantitative (n = 23) and qualitative (n = 27) methods, and a very small number (n = 2) used a mixed methods approach. Among quantitative studies, 18 had a cross-sectional or one-point-in-time design, and 5 used a longitudinal design. Most of the qualitative studies (15) used a thematic analysis approach.

Characteristics of the populations covered in included studies

Among included articles, 4 focused on women [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ] and older women [ 34 ]; 5 studies examined male [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ] or older male populations [ 39 ]. In total, 10 articles focused on older adults, which usually included early aging starting from 50 years [ 40 ] or 55 years [ 41 ] of age and above for populations with experience of homelessness. We found no studies that focused on non-binary groups, though gender-diverse self-identified individuals were included in 6 of the studies [ 33 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Moreover, there were a small number of studies (n = 6) focused on youth. Three of these were quantitative studies [ 47 , 48 , 49 ] comparing homeless youth and young adults to youth in the general population. The other 3 were qualitative studies [ 50 , 51 , 52 ]; 2 described how youth experience loneliness [ 51 , 52 ]; one study identified strategies for dealing with feelings of loneliness among homeless adolescents [ 50 ]. Three studies [ 53 , 54 , 55 ] focused on a population of veterans who were currently experiencing homelessness or were formerly homeless and living in either subsidized or supportive housing. Participants’ ethnicity was reported in most of the studies (n = 32).

Social isolation and loneliness as the primary objective

Only 18 of the 52 studies focused on SIL as their primary objective or included SIL in the main research questions. Of these 18 studies, 13 were quantitative and 5 were qualitative as summarized in Tables 1 and 2 . In the remaining 34 articles, SIL neither was the main objective nor clearly stated in the objectives or research questions. In those studies, SIL was usually considered as one of the potential explicative or control factors [ 30 , 56 , 57 ], and eventually emerged or co-created from participants’ narratives.

Conceptualization of social isolation and loneliness

Different theoretical frameworks were used to contextualize SIL in relation to unhoused or homelessness experiences. For some studies, SIL was embedded in the homelessness experience, since homelessness is in itself a form of social exclusion, which limits people’s participation in society [ 36 , 58 ]. Lafuente et al. [ 36 ] explained the experience of unhoused men through the lens of social disaffiliation theory. They explained that situational changes (i.e., loss of employment) or intrinsic factors (voluntary withdrawal) caused participants to become socially disaffiliated. Narratives on isolation from this study revealed feelings of alienation, powerlessness, self-rejection, depression, loneliness and unworthiness. Similarly, the study by Burns et al. [ 39 ] explained how the transient nature of being unhoused creates interrelated dimensions of social exclusion, generating a sense of invisibility, identity exclusion, racism, exclusion of social ties and meaningful interactions with the community, thus leading to social isolation.

Bell and Walsh [ 37 ] conceptualized SIL among individuals experiencing homelessness as being driven by mainstream normative conceptions of homelessness and the stigma of homelessness. The authors suggest that conceptions of homelessness conflate between notions of “rooflessness” and “rootlessness” which “denotes the absence of support and inclusion in one’s community driving experiences of isolation and loneliness.” [ 37 ].

In the study by Baker et al., [ 58 ] SIL is discussed as part of a new landscape of a network society and digital exclusion. The rapid development of information and communication technologies (ICT) has drastically changed human communication and interactions leaving many behind and out of communication flows . The authors explained that aging combined with many social disadvantages like histories of homelessness, multiple complex needs, rural areas of residence, and economically restricted mobility can contribute to creating or keeping affected older adults disconnected and socially isolated.

Meaning and experiences of social exclusion and, in particular SIL were further voiced through semi-structured qualitative interviews or focus groups in different studies. Often, participants reflected on how broader structural stigmatization and alienation associated with housing insecurity contributed to their perceived SIL. Jurewicz et al. [ 59 ] highlighted how systemic policies and practices affecting individuals experiencing homelessness who used substances generate and contribute to ongoing experiences of housing precarity, loneliness and isolation. Participants further discussed the complex interrelationship between substance use and homelessness including the strain on social relationships as a result of substance use [ 59 ]. Similarly, Martínez et al., [ 60 ] described how experiences of loneliness are driven by a lack of meaningful relationships, conflicts with families, a lack of social inclusion, and marginalization faced by individuals residing in a residential center in Gipuzkoa, Spain. In the study by Johnstone et al., [ 61 ] social isolation was defined as being associated with not having perceived opportunities to develop multiple group memberships.

Experiences and conceptualizations of loneliness were not strictly dependent upon one’s lack of access to housing. Two studies discussed how the transition into supportive or transitional housing further exacerbated experiences of loneliness and isolation [ 53 , 62 ]. Polvere, Macnaughton and Piat [ 62 ] and Winer et al. [ 53 ] highlighted that the transition to living within congregate-supported settings or independent apartments can be linked to experiences of SIL even when people are offered social engagement activities. Some participants reported feeling voluntarily isolated as they did not want to engage with others and some participants anticipated social isolation due to transitioning into a new environment.

Measurement tools to assess social isolation and loneliness

There were multiple approaches to measuring SIL across all studies, including widely used and validated multi-item scales and single-item measures. There were three main scales that were developed, revised, tested or used to measure SIL among people experiencing homelessness: The Rokach Loneliness questionnaire, the UCLA Loneliness Scale and its revised versions, and the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale.

The rokach loneliness questionnaire

Five studies used the Rokach Loneliness Questionnaire [ 47 , 48 , 49 , 63 , 64 ]. The Rokach Loneliness Questionnaire [ 47 , 48 ] measures causes of loneliness and coping strategies and has been used in studies with young people aged 15–30 in Toronto, Canada. The questionnaire measures the experience of loneliness across five factors, with yes/no items on five subscales: emotional distress such as pain or feelings of hopelessness; social inadequacy and alienation including a sense of detachment; growth and discovery such as feelings of inner strength and self-reliance; interpersonal isolation including alienation or rejection; and self-alienation such as feelings of numbness or denial. The items on the interpersonal isolation subscale relate to an overall lack of close or romantic relationships.

The UCLA loneliness scale

Six of the studies in this review used the UCLA Loneliness Scale or a revised version. Novacek et al. [ 54 ] assessed subjective feelings of SIL among Black and White identifying veterans with psychosis and recent homelessness compared with a control group at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The 20-item scale was used to measure subjective feelings of SIL over the past month. Participants rated their experience ranging from “never” to “often,” with higher scores indicating higher subjective feelings of loneliness. Lehmann et al. [ 38 ] used a revised version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale to examine individual factors including loneliness relevant in people experiencing homelessness to report their victimization to police. The researcher recruited 60 self-identified adult males aged 19 to 67 currently experiencing homelessness in Germany and used a revised and shorter German UCLA Loneliness Scale developed by Bilsky and Hosser [ 65 ], to measure loneliness. The scale is composed of 12 items with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much”) and positively formulated items were recorded to reflect a higher level of loneliness. The load factors for the scale are experiences of general loneliness, emotional loneliness, and inner distance. Drum and Medvene [ 66 ] used the UCLA-R Loneliness Scale, which has been adapted for an older adult population to measure loneliness among older adults living in affordable seniors housing in Wichita, Kansas. This version is composed of 23 items, with a four-point Likert scale-type of response options. Participants’ total score ranged from 20 to 80, with a higher score representing greater loneliness.

Tsai et al. [ 67 ], Dost et al. [ 68 ] and Ferrari et al. [ 69 ] used a shortened revised version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3, which consists of three items: “how often they feel they lack companionship, how often they feel left out, and how often they feel isolated from others.” Participants self-reported their responses using a 3-point Likert scale (“hardly ever,” “some of the time,” and “often”) to answer questions. A summed score of 3 to 5 is defined as not lonely and a summed score of 6 or more is defined as lonely. The 3-item scale is used widely in research and clinical settings as a short assessment of loneliness.

De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale