- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: November 16, 2023 | Original: October 6, 2017

Hinduism is the world’s oldest religion, according to many scholars, with roots and customs dating back more than 4,000 years. Today, with more than 1 billion followers , Hinduism is the third-largest religion worldwide, after Christianity and Islam . Roughly 94 percent of the world’s Hindus live in India. Because the religion has no specific founder, it’s difficult to trace its origins and history. Hinduism is unique in that it’s not a single religion but a compilation of many traditions and philosophies: Hindus worship a number of different gods and minor deities, honor a range of symbols, respect several different holy books and celebrate with a wide variety of traditions, holidays and customs. Though the development of the caste system in India was influenced by Hindu concepts , it has been shaped throughout history by political as well as religious movements, and today is much less rigidly enforced. Today there are four major sects of Hinduism: Shaivism, Vaishnava, Shaktism and Smarta, as well as a number of smaller sects with their own religious practices.

Hinduism Beliefs, Symbols

Some basic Hindu concepts include:

- Hinduism embraces many religious ideas. For this reason, it’s sometimes referred to as a “way of life” or a “family of religions,” as opposed to a single, organized religion.

- Most forms of Hinduism are henotheistic, which means they worship a single deity, known as “Brahman,” but still recognize other gods and goddesses. Followers believe there are multiple paths to reaching their god.

- Hindus believe in the doctrines of samsara (the continuous cycle of life, death, and reincarnation) and karma (the universal law of cause and effect).

- One of the key thoughts of Hinduism is “atman,” or the belief in soul. This philosophy holds that living creatures have a soul, and they’re all part of the supreme soul. The goal is to achieve “moksha,” or salvation, which ends the cycle of rebirths to become part of the absolute soul.

- One fundamental principle of the religion is the idea that people’s actions and thoughts directly determine their current life and future lives.

- Hindus strive to achieve dharma, which is a code of living that emphasizes good conduct and morality.

- Hindus revere all living creatures and consider the cow a sacred animal.

- Food is an important part of life for Hindus. Most don’t eat beef or pork, and many are vegetarians.

- Hinduism is closely related to other Indian religions, including Buddhism , Sikhism and Jainism.

There are two primary symbols associated with Hinduism, the om and the swastika. The word swastika means "good fortune" or "being happy" in Sanskrit, and the symbol represents good luck . (A hooked, diagonal variation of the swastika later became associated with Germany’s Nazi Party when they made it their symbol in 1920.)

The om symbol is composed of three Sanskrit letters and represents three sounds (a, u and m), which when combined are considered a sacred sound. The om symbol is often found at family shrines and in Hindu temples.

Hinduism Holy Books

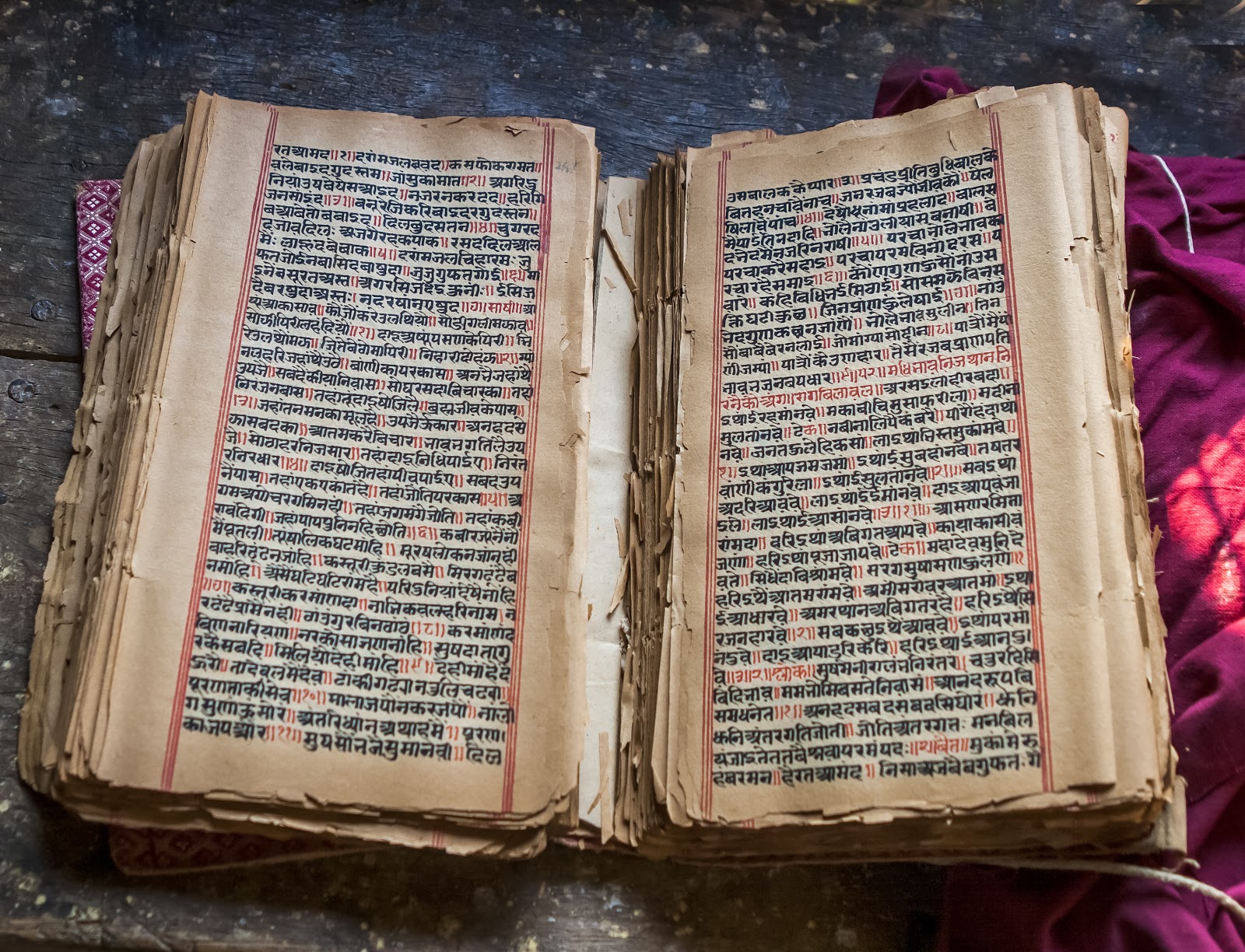

Hindus value many sacred writings as opposed to one holy book.

The primary sacred texts, known as the Vedas, were composed around 1500 B.C. This collection of verses and hymns was written in Sanskrit and contains revelations received by ancient saints and sages.

The Vedas are made up of:

- The Rig Veda

- The Samaveda

- Atharvaveda

Hindus believe that the Vedas transcend all time and don’t have a beginning or an end.

The Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, 18 Puranas, Ramayana and Mahabharata are also considered important texts in Hinduism.

Origins of Hinduism

Most scholars believe Hinduism started somewhere between 2300 B.C. and 1500 B.C. in the Indus Valley, near modern-day Pakistan. But many Hindus argue that their faith is timeless and has always existed.

Unlike other religions, Hinduism has no one founder but is instead a fusion of various beliefs.

Around 1500 B.C., the Indo-Aryan people migrated to the Indus Valley, and their language and culture blended with that of the indigenous people living in the region. There’s some debate over who influenced whom more during this time.

The period when the Vedas were composed became known as the “Vedic Period” and lasted from about 1500 B.C. to 500 B.C. Rituals, such as sacrifices and chanting, were common in the Vedic Period.

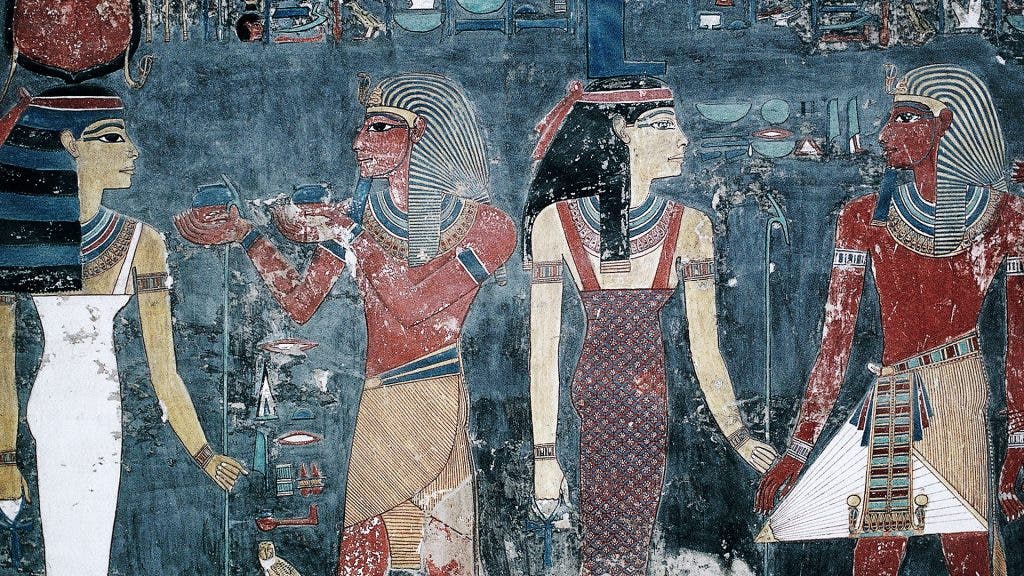

The Epic, Puranic and Classic Periods took place between 500 B.C. and A.D. 500. Hindus began to emphasize the worship of deities, especially Vishnu, Shiva and Devi.

The concept of dharma was introduced in new texts, and other faiths, such as Buddhism and Jainism, spread rapidly.

Hinduism vs. Buddhism

Hinduism and Buddhism have many similarities. Buddhism, in fact, arose out of Hinduism, and both believe in reincarnation, karma and that a life of devotion and honor is a path to salvation and enlightenment.

But some key differences exist between the two religions: Many strains of Buddhism reject the caste system, and do away with many of the rituals, the priesthood, and the gods that are integral to Hindu faith.

Medieval and Modern Hindu History

The Medieval Period of Hinduism lasted from about A.D. 500 to 1500. New texts emerged, and poet-saints recorded their spiritual sentiments during this time.

In the 7th century, Muslim Arabs began invading areas in India. During parts of the Muslim Period, which lasted from about 1200 to 1757, Islamic rulers prevented Hindus from worshipping their deities, and some temples were destroyed.

Mahatma Gandhi

Between 1757 and 1947, the British controlled India. At first, the new rulers allowed Hindus to practice their religion without interference, but the British soon attempted to exploit aspects of Indian culture as leverage points for political control, in some cases exacerbating Hindu caste divisions even as they promoted westernized, Christian approaches.

Many reformers emerged during the British Period. The well-known politician and peace activist, Mahatma Gandhi , led a movement that pushed for India’s independence.

The partition of India occurred in 1947, and Gandhi was assassinated in 1948. British India was split into what are now the independent nations of India and Pakistan , and Hinduism became the major religion of India.

Starting in the 1960s, many Hindus migrated to North America and Britain, spreading their faith and philosophies to the western world.

Hindus worship many gods and goddesses in addition to Brahman, who is believed to be the supreme God force present in all things.

Some of the most prominent deities include:

- Brahma: the god responsible for the creation of the world and all living things

- Vishnu: the god that preserves and protects the universe

- Shiva: the god that destroys the universe in order to recreate it

- Devi: the goddess that fights to restore dharma

- Krishna: the god of compassion, tenderness and love

- Lakshmi: the goddess of wealth and purity

- Saraswati: the goddess of learning

Places of Worship

Hindu worship, which is known as “puja,” typically takes place in the Mandir (temple). Followers of Hinduism can visit the Mandir any time they please.

Hindus can also worship at home, and many have a special shrine dedicated to certain gods and goddesses.

The giving of offerings is an important part of Hindu worship. It’s a common practice to present gifts, such as flowers or oils, to a god or goddess.

Additionally, many Hindus take pilgrimages to temples and other sacred sites in India.

6 Things You Might Not Know About Gandhi

The iconic Indian activist, known for his principle of nonviolent resistance, had humble beginnings and left an outsized legacy.

The Ancient Origins of Diwali

Diwali, also known as the Festival of Lights, is primarily celebrated by followers of the Hindu, Sikh and Jain faiths.

Hinduism Sects

Hinduism has many sects, and the following are often considered the four major denominations.

Shaivism is one of the largest denominations of Hinduism, and its followers worship Shiva, sometimes known as “The Destroyer,” as their supreme deity.

Shaivism spread from southern India into Southeast Asia and is practiced in Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia as well as India. Like the other major sects of Hinduism, Shaivism considers the Vedas and the Upanishads to be sacred texts.

Vaishnavism is considered the largest Hindu sect, with an estimated 640 million followers, and is practiced worldwide. It includes sub-sects that are familiar to many non-Hindus, including Ramaism and Krishnaism.

Vaishnavism recognizes many deities, including Vishnu, Lakshmi, Krishna and Rama, and the religious practices of Vaishnavism vary from region to region across the Indian subcontinent.

Shaktism is somewhat unique among the four major traditions of Hinduism in that its followers worship a female deity, the goddess Shakti (also known as Devi).

Shaktism is sometimes practiced as a monotheistic religion, while other followers of this tradition worship a number of goddesses. This female-centered denomination is sometimes considered complementary to Shaivism, which recognizes a male deity as supreme.

The Smarta or Smartism tradition of Hinduism is somewhat more orthodox and restrictive than the other four mainstream denominations. It tends to draw its followers from the Brahman upper caste of Indian society.

Smartism followers worship five deities: Vishnu, Shiva, Devi, Ganesh and Surya. Their temple at Sringeri is generally recognized as the center of worship for the denomination.

Some Hindus elevate the Hindu trinity, which consists of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Others believe that all the deities are a manifestation of one.

Hindu Caste System

The caste system is a social hierarchy in India that divides Hindus based on their karma and dharma. Although the word “caste” is of Portuguese origin, it is used to describe aspects of the related Hindu concepts of varna (color or race) and jati (birth). Many scholars believe the system dates back more than 3,000 years.

The four main castes (in order of prominence) include:

- Brahmin: the intellectual and spiritual leaders

- Kshatriyas: the protectors and public servants of society

- Vaisyas: the skillful producers

- Shudras: the unskilled laborers

Many subcategories also exist within each caste. The “Untouchables” are a class of citizens that are outside the caste system and considered to be in the lowest level of the social hierarchy.

For centuries, the caste system determined most aspect of a person’s social, professional and religious status in India.

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From the Sphinx of Egypt to the Kama Sutra, explore ancient history videos.

When India became an independent nation, its constitution banned discrimination based on caste.

Today, the caste system still exists in India but is loosely followed. Many of the old customs are overlooked, but some traditions, such as only marrying within a specific caste, are still embraced.

Hindus observe numerous sacred days, holidays and festivals.

Some of the most well-known include:

- Diwali : the festival of lights

- Navaratri: a celebration of fertility and harvest

- Holi: a spring festival

- Krishna Janmashtami: a tribute to Krishna’s birthday

- Raksha Bandhan: a celebration of the bond between brother and sister

- Maha Shivaratri: the great festival of Shiva

Hinduism Facts. Sects of Hinduism . Hindu American Foundation. Hinduism Basics . History of Hinduism, BBC . Hinduism Fast Facts, CNN .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Hindu University of America

- President’s Message

- Mission & Vision

- Ethos And Culture

- Our Promise

- Learn more about HUA

- Donate Today

- Areas of Study

- Credit Hours

- Academic Calendar

- Explore programs and courses

- Browse our course catalog

- Conversion Formula

- Credit Transfer

- Tuition and Fees

- Scholarships

- Learn more about our admissions process

- Advancement

- Director’s Message

- Giving to HUA

- Giving Categories

- Sustenance Funds

- Capital Funds

- Endowment Funds

- Donor Recognition

- Legacy Gift Guidelines

- Learn about giving to HUA

- Give to HUA

- Access HUA Email

- Access HUA LMS

A case for Hindu Studies in Academia

The Hin du co mmun it y in India and globally have a dual role and respo nsibility: as direct inheritors of Hindu legacy and as its custodians. … The collective body of Hindu literature and writings is vast and rich, and merits a status of a world heritage and a study for its own sake.

Following the Roman empire’s decline and fall, European and Near East histories have been rife with accounts of hegemonic battles among the three Abrahamic civilizations. Islam overran nations at the point of a sword, crusaders inspired by the Popes attempted to wrest back control of their Holy Land, Christians’ inquisitions terrorized heretics, and their conquests decimated the indigenous cultures of the New World. And in the post-medieval world, while Islamic civilization remains stymied by nostalgia of its losses to Judeo-Christian rivals, there has been some moral redemption for the West through its science and material progress that have lifted millions out of poverty and the grips of disease. Yet, contemporaneously, many nations have been colonized and enslaved, pogroms unleashed and masses killed and nature’s ecological systems nearly destroyed in the pursuit of unbridled materialism and the imposition of a narrow and constipated set of religious doctrines and philosophical ideas. On balance, there has been material progress -- but, at a huge cost. It is, therefore, only natural to ask: “ Could a mindset different from a Western one, which dominates most of humanity today, offer a countervailing perspective and tend us toward a more balanced one? ” Yes, it is an idea worth studying – and, a contemplation of the Hindu mindset offers hope. Such a mindset, when rooted in a disciplined study and understanding of a Hindu perspective, promises that alternative to the world, outside of India. Equally, inside India, such a study of Hinduism is imperative for the curious Hindu as an inheritor and a custodian of its bequest so that it may reclaim, conserve and live its heritage – a heritage which faces a possibility of being lost to time. All this aside, the collection of Hindu ideas and all their accompanying disciplines merit a study for its own sake as a world heritage. Hinduism has created by far the longest surviving civilization, has offered a deeply contrasting set of views on life and post-life through a body of literature that is manifold vaster than the collective set of classical writings of the West, and in a language – Sanskrit – admired not just for its antiquity but also for its grammatical precision. Furthermore, in academia, there is a need to address a skewed discourse on Hinduism, led in large part by its detractors, by encouraging and fostering an exhaustive, well-researched, cogent and targeted body of academic writings grounded in the hermeneutics of shraddha . All in all, a disciplined and academic study of the body of Hindu literature and philosophy is essential and needed today to offer a counterpoint to an all-pervasive Western way of thinking, to safeguard, preserve and pass on Hindu philosophical thought, to study for its own sake an ancient, rich and vast body of world heritage literature, and to countervail against the predominantly outsiders’ perspectives in academia.

Only a few limited concepts from the Hindu way have moved from the periphery and exotica to mainstream on the global stage – others remain untouched or confined to study by a coterie of scholars in Western academic institutions. Uniquely, it is Yoga which in the last several decades has been embraced by large numbers of people for its palpable benefits to the well-being of individuals and society. Vegetarianism and ahimsa toward all beings and nature – quintessential Indian and Hindu1 concepts – have also begun to gain currency.2 Yet, to an informed insider to Hinduism, these concepts are merely incidental outgrowths from a larger set of foundational philosophical ideas. Yoga, from an insider’s perspective, is just one among numerous ways to follow in the quest for answers to existential questions; its salutary effects, while important to prepare the body and mind for contemplative meditation, are only incidental to the larger goal of seeking Brahman. The larger body of Hindu thoughts has many other underlying principles that can benefit humanity: for instance, there are multiple ways to get to the same Truth (an absence of a singular doctrine), that an individual may see the same God in his/her own way but different from another individual, and that a path to spiritual goal traverses one’s inner self and doesn’t require an external and disassociated God (the concept of Advait ). Over millennia, these principles have permitted freedom of thought and expression, and created a civilizational mindset of accommodation and acceptance of different ideas quite in contrast to Abrahamic religions’ hegemonic belief of conversion to their form of the Truth. So, with time, Hinduism has responded to the new ideas and debates that have arisen from within and without, and spawned three other bodies of religious thought, viz. Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism; and these have brought forth distinct, and sometimes contrasting, positions to that of Hinduism itself. Ahimsa came from Jain philosophy of non-violence against all beings and living things – and, Hinduism, later, accepted and incorporated this as its own basic tenet. For the people beyond its boundaries, it has nurtured a civilization of refuge, which has made room for people persecuted elsewhere and accepted their religious ideas and manifestations as still a new set of perspectives, meriting respect and understanding. So, if a greater number of people are exposed to Hindu ideas by way of academic study and discourse, humanity could together, perhaps, find a middle path that offers hopes of a world more peaceful and of planet Earth more sustainable.

The Hindu community in India and globally have a dual role and responsibility: as direct inheritors of Hindu legacy and as its custodians. However, over the last thousand years and particularly in the last three centuries, Hindus have ceded control of their institutions of learning and grown diffident about their inherited knowledge. Pride, the sense of ownership and of responsibility to conserve and embellish this knowledge has given way to an ambivalence about their own inheritance and a consuming need to acquire outsiders’ systems of values and education. The historical discontinuities of conquests and forced arrogation of power by invaders and colonizers have diminished and interrupted the natural intergenerational flow of knowledge. It is therefore a challenge to resurrect a mindset of pride of ownership, of research and conservation. The challenges for the curious and academically inclined Hindus are further compounded because Hinduism resides not in any one book, but in a vast compendium of writings, discourses and commentaries. To string it all together without easy access to in-depth knowledge and the teaching methods of its living practitioners – gurus and acharyas – is a daunting task for most. Besides, an ecosystem of learning and livelihood to sustain a quest for its study is practically non-existent, even after seventy years of the end of colonial rule. As hopeless as it might seem, there are some green shoots of a growing awareness of this problem and the need to fix it. Against this backdrop, it is essential to create centers of learning within existing Indian and select foreign academic institutions that focus and engage in rigorous study and research into Hindu writings. Given the vastness and range of philosophical subjects and thoughts, the study must be undertaken by not a limited few, but a larger number of institutions – with each institution becoming a center of specialty of a unique school of thinking. This way a wide range of subjects and thoughts can be addressed simultaneously and collectively by a distributed and connected network of academic institutions. With time and focused curation, the overall standard of research and writing would improve and attract brighter minds, and livelihood opportunities would emerge in academia and beyond – the flywheel of Hindu studies would then begin to turn and gain momentum. From this ecosystem would emerge future scholars – gurus and acharyas – who would then propagate and sustain an academic study of Hindu writings within and without India and offer an intellectual and academic counterweight to balance the scale in debates on Hindu philosophy and schools of thought.

The collective body of Hindu literature and writings is vast and rich and merits a status of a world heritage and a study for its own sake. Greek and Latin writings – classical works of Western civilization transcribed in about 30,000 manuscripts – enjoy a disproportionate status in academia. In contrast, Hinduism’s Sanskrit, Tamil and other writings – estimated to be in many million manuscripts – are relegated as esoterica even before an impartial study and discourse are conducted. Hindu deliberations offer a very distinct set of points of view on life, death, co-existence with others and nature, health and well-being, and on the visible universe around us and what may lie beyond human perception. It is this combination of being distinct, multi-disciplinary and voluminous that makes a case for academic institutions to dedicate resources and study Hindu philosophies while maintaining a balance between the two approaches of academic study, viz. the hermeneutics of suspicion and hermeneutics of s hraddha .

Western academia, while being an outsider to Hinduism, is ironically the largest producer of commentaries and research on the latter. And, not surprisingly, given its Abrahamic roots, the balance of writings tends to have a preponderance of hermeneutics of suspicion. Such an academic environment has its own dynamics, which essentially regurgitates and validates a prevailing point of view from one writing to the next. The voice of an insider scarcely finds a set of sponsors and supporters. This lopsidedness is self-perpetuating. An externally originating thrust which pushes against this imbalance is therefore imperative to reclaim space and control the narrative. Only a deliberate plan and action to address this need can succeed in the academic world. Indian institutions, alongside some other sympathetic places of learning could be encouraged and fostered to develop a veritable counter narrative. Such an effort must lay down and adhere to the most rigorous academic standards for the evaluation of research which rival those of eminent academic institutions anywhere in the world.

While it may seem that Hindu studies have a very arduous climb up the academic hill, its success is achievable, for there is a reassuring confidence in an informed insider rooted in the durability of Hindu ideas, which have endured the longest journey of many millennia and created a civilization that has given the world alternative perspectives through the wisdom of Gita, Buddha, Mahavir, Nanak and Gandhi, of yoga and ahimsa to name a few – and, all this with the power of thought, appeal and debate, and without violence and without being an existential threat to fellow beings and nature itself.

- This paper speaks of Hindu philosophy and ideas in a broader sense, embracing with it ideas found in other Indic traditions, like Jainism and Buddhism.

- Unlike Yoga in the West, these concepts are generally not directly attributed to the Hindu way, but as ideas emanating from the need to have a healthier life and a sustainable planet.

Related Articles

Who speaks for hindu studies, better understanding of hinduism requires a multi-pronged approach, importance of hindu studies in universities.

- Utility Menu

GA4 tracking code

- For Educators

- For Professionals

- For Students

dbe16fc7006472b870d854a97130f146

Pollution and india's living river.

PDF Case File

Download Case

Note on This Case Study

Global anthropogenic—or human caused—climate change has deeply impacted the ways that religions are practiced around the world. At the same time, religions have also played major roles in framing the issue among their believers. Some Hindus work tirelessly to change their habits and mitigate human impact on the climate. Others ignore the crisis, or do not believe in Hindu environmentalism. Read this case study with this in mind: the Hindus described here show a range of reactions to climate change, but all of them are Hindu.

As always, when thinking about religion and climate change, maintain a focus on how religion is internally diverse, always evolving and changing, and always embedded in specific cultures.

While Hinduism is a global religion, most Hindus—nearly one billion—live in India. In fact, Hindu goddesses are often a part of the Indian geographical landscape. This includes the deified river: the Ganges.

The Ganges River, also known as Ma Ganga (or Mother Ganges), flows from the glaciers of the Himalayas and crosses much of the subcontinent before flowing into the Indian Ocean. The religious origins of this goddess are varied, and devotees of different Hindu gods often believe in different stories about her. One of the more common stories comes from followers of the god Shiva. Many Shiva devotees believe Mother Ganges offered to descend to earth to purify the burning coals of the ancestors of the Hindu sage Bhagiratha. However, she was concerned that her fall from the cosmic realm would destroy the earth, so Shiva offered to catch her in his hair. Her waters ran in rivulets through his hair and onto the earth, where she purified the remains.

The Ganges River is therefore not only a waterway, but a goddess from heaven. Thus, many Hindus believe that the river has incredible healing powers. It is a common belief that bathing in the Ganges washes away a person’s bad karma and is like being in heaven. Some Hindus even believe that being brushed by a breeze which contains a single drop of the Ganges will absolve the impurities of multiple lifetimes. To most Hindus, dying in the holy city of Varanasi, on the banks of the Ganges, is said to result in moksha—a release from the endless cycle of suffering and rebirth. It is estimated that 32,000 corpses are cremated each year in Varanasi, after which their ashes are given to the Ganges. Others who cannot afford cremation simply wrap and float the body down the river. To access her healing waters, Hindus travel from all over the world on pilgrimages, often filling containers with water to bring back to their homes for rituals or healings. In fact, the largest gathering of human beings in the entire world regularly occurs on the banks of the river at the city of Allahabad. Every 12 years, the city hosts the Kumbh Mela, a religious festival during which the central ritual is bathing in the Ganges to achieve moksha. In 2001, over 30 million pilgrims attended, making it the largest gathering in human history. Unfortunately, the river has also become one of the most polluted bodies of water in the entire world, due to India’s exploding population and rapid industrialization. Over 450 million people live in the Ganges river basin, and human waste is the cause of most of the pollution. Almost five billion liters of sewage flow into the river every day, only a quarter of which is treated. By Varanasi, the Ganges is an open sewer. Fecal bacteria at this point is 150 times higher than the safe level for bathing, let alone drinking. Over 300,000 Indian children die annually from drinking contaminated water. Industrial effluent also pollutes the river, particularly from tanneries in Kanpur. Indian industries dump nearly a billion liters of waste into the river daily. Climate change has worsened the problem: water flow has decreased as Himalayan glaciers shrink.

In fact, many Hindus continue to bathe in or even drink the Ganges regularly. Confident in the healing powers of the divine river, they believe nothing could compromise the purity of their goddess. For them, Mother Ganges exists to wash away the impurities and pollution of earth and thus can cleanse herself. Major cleanup efforts are thus a waste of money and effort. Some governments and industries have taken advantage of these beliefs, and have used confidence in the cleansing power of the Ganges to justify continuing to pollute the river. Other Hindus acknowledge the problem, but lay blame on Muslims. Because cattle are holy to many Hindus, Kanpur’s polluting tanneries—which create leather from cowhides—are all owned by Muslims. Many Muslims claim that they have been unfairly persecuted by Hindu nationalists, who they say would rather persecute Muslim businesses than address more expensive sewage issues.

In March 2017, as cleanup efforts continued to fail, the High Court of Uttarakhand state confirmed the deified status that Hindus have long given the river. They issued a judgment that the Ganges and the Yamuna river—a Ganges tributary—are “living entities” which are entitled to human rights. Those caught polluting the river could thus be charged with assault or even murder. A few days later, activists sought murder charges against several politicians on behalf of the Yamuna River, sections of which are no longer able to support life. However, on July 7, 2017, the Supreme Court of India struck down Uttarakhand state’s ruling, arguing that treating the rivers as living entities was impractical. The Ganges is still revered as a living goddess by Hindus across the world, but an effective solution to its pollution remains elusive. Hinduism Case Study – Climate Change 2018

Additional Resources

Primary sources:, secondary sources:.

• BBC in-depth reporting on “India’s Dying Mother”: http://bbc.in/2vBdlH3 • BBC video on the religious and geographic origins of the Ganges: http://bit.ly/2fnnhgD • NPR report on the Ganges as a legal “living entity”: http://n.pr/2sj02Ge • Financial Times video on pollution in the Ganges: http://bit.ly/2vyigrY • The Guardian video on pollution in the Yamuna River: http://bit.ly/2uAEIfD • PBS video on the Kumbh Mela festival: http://to.pbs.org/1EnPeeb • National Geographic video on cremations at the Ganges: http://bit.ly/2wo0SUm

Discussion Questions

This case study was created by Kristofer Rhude, MDiv ’18, under the editorial direction of Dr. Diane L. Moore, faculty director of Religion and Public Life.

- 1. World Religion Database, ed. Todd M. Johnson and Brian A. Grim (Boston: Brill, 2015).

- 2. Kelly D. Alley, On the Banks of the Ganga: When Wastewater Meets a Sacred River, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002), 56-60; David Kinsley, Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition, (Berkeley: UC Press, 1986), 188-189.

- 3. Kinsley Hindu Goddesses, 191, 193-4; Justin Rowlatt, “India’s Dying Mother,” BBC News, (London), May 12, 2016. http://bbc.in/21TmEJ6

- 4. Linda Davidson and David Gitlitz, Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland: An Encyclopedia, (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2002), 322-3.

- 5. Rowlatt, “India’s Dying Mother”; George Black, “What it Takes to Clean the Ganges,” The New Yorker, Jul. 25, 2016. http://bit.ly/29PUsCy

- 6. Krishna N Das, “India’s Holy Men to Advise Modi’s Ganges River Cleanup,” Reuters, (New Delhi), June 12, 2014. http://reut.rs/2vnJFKN

- 7. Rowlatt, “India’s Dying Mother.”; Black, “What it Takes to Clean the Ganges.”; Das, “India’s Holy Men.”

- 8. Alley, On the Banks of the Ganges, 237; Kinsley, Hindu Goddesses, 191; Rowlatt, “India’s Dying Mother”;

- Amrit Dhillon, “The Ganges: Holy River from Hell,” The Sydney Morning Herald, Aug. 4, 2014. http://bit.ly/2vQwWn6

- 9. Black, “What it Takes to Clean the Ganges.”

- 10. Michael Safi, “Murder Most Foul: polluted Indian river reported dead…,” The Guardian (Delhi), July 7, 2017. http://bit.ly/2tTIGU3

- See more Christianity Case Studies

- See more Climate Change Case Studies

Arranged Marriages, Matchmakers, and Dowries in India

Arranged marriages in india.

Arranged marriages have been part of the Indian culture since the fourth century. Many consider the practice a central fabric of Indian society, reinforcing the social, economic, geographic, and the historic significance of India (Stein). Prakasa states that arranged marriages serve six functions in the Indian community: (1) helps maintain the social satisfaction system in the society; (2) gives parents control, over family members; (3) enhances the chances to preserve and continue the ancestral lineage; (4) provides an opportunity to strengthen the kinship group; (5) allows the consolidation and extension of family property; (6) enables the elders to preserve the principle of endogamy (Prakasa 17) (see Gender and Nation ).

The practice of arranged marriages began as a way of uniting and maintaining upper caste families. Eventually, the system spread to the lower caste where it was used for the same purpose (see Caste System in India ). The specifics of arranged marriages vary, depending on if one is Hindu or Muslim. “Marriage is treated as an alliance between two families rather than a union between two individuals” (Prakasa 15). The Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929-1978 states that the legal age for marriage is 18 for females, and 21 for males,with most females being married by 24 and most males being married by their late twenties (McDonald). However, many children, age 15 and 16 are married within a cultural context, with these marriages being neither void or voidable under Hindu or Muslim religious law, as long as the marriage is not consummated until the legal age of 18 for females and 21 for males.

Muslim Arranged Marriages in India

In the Muslim faith, it is the responsibility of the parents to provide for the education and the marriage of their children. The parent’s duties are not considered complete unless their daughter is happily married (Ahmad 53). Marriage is a sunna , an obligation from the parent to the child that must be fulfilled because the female is viewed as a par gaheri , a person made for someone else’s house (53). In this custom, it is the responsibility of the groom’s parents to make the initial move toward marriage: seeking eligible females and insuring their son is marketable. Once a female has been selected, the father of the male sends a letter to the perspective bride’s father, through a maulvi , a liaison between the families, asking the father if his daughter can marry his son. If the female’s father accepts by letter, then a formal ceremony is held at the female’s house, where the father of the groom asks the girl’s father if his daughter can marry. A feast and perhaps the giving of gifts, depending on the region of the exchange, follow the “asking” ceremony. During the feast, the respective parents set a time to solemnize the marriage, “usually during the summer season (garmiyan) because it allows more time for people to attend” (98). The date of the actual marriage ceremony depends on the age of the individuals, which ranges from four years to eight years after the “asking” ceremony (97).

Most Muslim arranged marriages are solemnized four years after the “asking” ceremony. The ceremony itself consists of a sub ceremony: the maledera, where female members of the male’s family wash and dress the male in traditional clothing, and the female dera, where the female is washed, given henna, and given ceremonial jewelry (98). The actual marriage ceremony (nikah) consists of both individuals being asked if they are in agreement for marriage. Once a yes is acknowledged, the Koran is read, and the father determines a dowry, with 40% being paid at the nikah and an agreement that the rest will be paid at a later date. The paying of a dowry is culturally optional, but legally unlawful. Once the dowry has been agreed on, a marriage contract is drawn up and the female goes to live with the husband’s family.

If the daughter remains unmarried, she is considered a spinster, who brings shame upon her family, and she is considered a burden. A woman also suffers this fate if she is separated or single past 24 years old (Stein). For more information, see Divorce in India.

Hindu Arranged Marriages in India

Marriage is a sacramental union in the Hindu faith. “One is incomplete and considered unholy if they do not marry” (Parakasa 14). Because of these beliefs, many families begin marriage preparation well in advance of the date of marriage, with the help of “kinsmen, friends, and ‘go-betweens’” (14). Most females are married before puberty, with almost all girls being married before 16, while most boys are married before the age of 22 (Gupta 146). However, couples normally do not consummate the marriage until three years after the marriage ceremony (146). The legal age for marriages is 18 for females and 21 for males (McDonald). The male’s family is responsible for seeking the female. The male’s family is responsible for arranging the marriage. Like Muslim arranged marriages, the Hindu culture uses a matchmaker to help find possible matches. Once a match is found and arrangements met, the two families meet to discuss dowry, time, and location of the wedding, the birth stars of the boy and girl, and education (McDonald). During this time, the males of the family huddle in the center of the room, while the perspective couple sits at the periphery of the room and exchange glances. If the two families agree, they shake hands and set a date for the wedding (McDonald).

Most Hindu pre-wedding ceremonies take place on acuta , the most spiritual day for marriages. The ceremony often takes place early in the morning, with the male leading the female around a fire ( punit ) seven times. After the ceremony, the bride is taken back to her home until she is summoned to her husband’s family house. Upon her arrival, her husband’s mother is put in charge of her, where she is to learn the inner workings of the house. During this time she is not allowed to interact with the males of the house, because she is considered pure until the marriage is consummated. This period of marriage can range from three to six years (McDonald).

Arranged Marriage Matchmaker in India

The traditional arranged marriage matchmaker is called a nayan (Prakasa 21). The matchmaker is normally a family friend or distant relative who serves as a neutral go-between when families are trying to arrange a marriage. Some families with marriageable age children may prefer not to approach possible matches with a marriage proposal because communication between families could break down, and could result in accidental disrespect between the two families (Ahmad 68). Matchmakers can serve two functions: marriage scouts, who set out to find possible matches, and as negotiators, people who negotiate between families. As a scout and negotiator, a family sends the nayan into the community to seek possible matches. The matchmaker considers “family background, economic position, general character, family reputation, the value of the dowry, the effect of alliance on the property, and other family matters” (Prakasa 15). Once a match is found, the matchmaker notifies his or her clients and arranges communication through him or her. Communication is facilitated through the nayan until some type of agreement is met. Depending on the region, an actual meeting between the families takes place, to finalize the marriage agreement, while also allowing the couple to see each other (22).

Once a marriage agreement is met, the nayan may be asked to assist in the marriage preparations: jewelry and clothing buying, ceremonial set-up, and notification of the marriage to the community (Ahmad 68). The nayan usually receives no pay for his or her services, but may receive gifts: clothing, food, and assistance in farming from both families for the services they provide (69).

Newspapers, the Internet, television ads, and social conventions serve as the modern nayan (Prakasa 22). Indian families in metropolitan cities use the mass media as go-between as a way of bridging cultural gaps, in areas where there may be a small Indian population.

Dowries in India

Dowries originally started as “love” gifts after the marriages of upper caste individuals, but during the medieval period the demands for dowries became a precursor for marriage (Prakasa 61). The demand for dowries spread to the lower caste, and became a prestige issue, with the system becoming rigid and expensive. The dowry system became a tool for “enhancing family social status and economic worth” (61). Prakasa notes five purposes of the dowry: (1) provides an occasion for people to boost their self esteem through feasts and displays of material objects; (2) makes alliances with the families of similar status; (3) helps prevent the breakup of family property; (4) gets a better match for daughters; (5) furnishes daughters with some kind of social and economic security (61-62). The expensive nature of dowries has helped raise the marriage age in the middle and lower caste because families have not been able to meet dowry demands, and has also forced some families “to transcend their caste groups and find bridegrooms from other sub caste and different caste” (62).

There are some disadvantages to dowries. Families may suffer financial hardships due to the expensive nature of dowries. They may not be able to afford dowries, therefore prohibiting their children from marriage, causing “girls to occasionally commit suicide in order to rid their fathers of financial burdens” (62). Because of social instances like these, many consider “the dowry system as a social evil and an intolerable burden to many brides’ families”(62).

As a result, the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961 was passed. It decrees, “to give, take, or demand a dowry is an offense punishable by imprisonment and fines” (77). A dowry is also defined as “any property or valuable security given or agreed to be given either directly or indirectly by one party to a marriage to the other party to the marriage, or by the parents of either party to a marriage or by any other person, to either party to the marriage or to any other person at or before or after the marriage as consideration for the marriage of the said parties” (Diwan 77). The law does make the following exclusion: “any presents made at the time of marriage to either party to the marriage in the form of cash, ornament, clothes or other articles, do not count as a dowry” (77). These items are considered wedding gifts. The law does create the following loop hole; “the giving or taking of dowry does not affect the validity of the marriage… if the dowry is given, the bride is entitled to it, but the person giving it is punished by law if discovered” (77).

Select Bibliography

- Harlan, Lindsey, ed. From the Margins of Hindu Marriage: Essays on Gender, Religion, and culture. New York: Oxford University Press,1995.

- Kannan, Chirayil. Intercaste and inter-community marriages in India . Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1963.

- Manning, Henry Edward. Indian Child Marriages . London: New Review, 1890.

- Uberoi, Patricia, ed. Family, Kinship, and Marriage in India . New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Works Cited

- Ahmad, Imtiaz, ed. Family, Kinship and Marriage Among Muslimsin India . Manohar: Jawaharlal Nehru University Press, 1976.

- Diwan, Paras. Family Law: Law of Marriage and Divorce in India . New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Private Limited, 1983.

- Goswami, B, J. Sarkar, and D. Danda, eds. Marriage in India: Tribes, Muslims, and Anglo-India . Calcutta: Shri Sovan Lal Kumar,1988.

- Gupta, Giri Raj, ed. Family and Social Change in Modern India . Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 1971.

- Prakasa, Rao. Marriage, The Family and Women in India . Printox: South Asia Books,1982.

- Ramu, G. Family and Caste in Urban India: A Case Study . New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House PVT LTD, 1977.

- Reddy, Narayan. Marriages in India . Gurgaon: The Academic Press, 1978.

- Saheri’s Choice . Dir. Hamis McDonald. Videocorp LTD, 1998.

- Sastri, A. Mahadeva. The Vedic Law of Marriage or The Emancipation of Woman . New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1918.

- Stein, Dorothy. “Burning Widows, Burning Brides: The Perils of Daughterhood in India.” Pacific Affairs 61 (1988): 465-485.

Related Web Sites

Bollywood and Women

Caste System in India

Divorce in India

Gender and Nation

Third World and Third World Women

Women, Islam, and Hijab

Author: Santana Flanigan, Fall 2000 Last edited: October 2017

Related Posts

Introduction to postcolonial / queer studies, biocolonialism, 13 comments.

very well elaborated article, very useful. thanks for sharing.

This was so helpful. It was detailed and easy to understand.

Great article. Clarified a lot for my research paper

Thanks for the great information. Beautifully written.

I also wrote about how deep-rooted marriages are in Indian culture and how we are forced to marry at a particular age to someone in our cast and sub caste. I narrate my struggle with the orthodox system to stay unmarried even though I am 30 years old now.

Do visit my blog to read the article and let me know if you like it. 🙂

I have a question: Despite arranged marriages being encouraged at the legal age of 18, many girls are married as teenagers; why?

Pingback: Arranged Marriage: – Nick’s Blog

Hey I am a high school student in the 11th grade and I am working on a capstone project that is focused on arranged marriges and one of the components to the project is to contact an expert on the topic. I would really like some feedback from you guys and it would really help me alot

Thank you for the comment. Unfortunately, we are not experts on arranged marriage. If you email us at [email protected] with more details, I can try to find you some sources or connect you with someone that might be able to help you.

I am a high school student and I was wondering what credibility the author has for this source because I would like to use it in a paper I am writing. If you could help me that would be amazing and it would really help me.

Thank you for the comment. The post serves as an overview of Arranged Marriage in India. If you want to research further, see the “select bibliography” and “works cited” at the end of the post for additional sources.

Hey, Im doing a capstone project on arranged marriage too, but I’m looking at it more in a way of how science is involved in this traditional system in our modern days of technology. Good Luck on your paper!

The only way to achieve happiness is to cherish what you have and forget what you don’t have

Pingback: Netflix’s Indian Matchmaking and the Shadow of Caste - Non Perele - News Online

Write A Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- About Postcolonial Studies

- About This Site

- How to Cite Our Pages

- Calls for Papers

- Authors & Artists

- Critics & Theorists

- Terms & Issues

- Digital Bookshelf

- Book Reviews

- You can contribute

- About the Program

- Emory GPS Events

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Exploring indian culture through food.

Food and Identity

Food (Sanskrit— bhojana,“that which is to be enjoyed,” Hindi— khana, Tamil— shapad) presents a way to understand everyday Indian culture as well as the complexities of identity and interaction with other parts of the world that are both veiled and visible. In India today,with a growing economy due to liberalization and more consumption than ever in middle class life, food as something to be enjoyed and as part of Indian culture is a popular topic. From a 1960s food economy verging on famine, India is now a society where food appears plentiful, and the aesthetic possibilities are staggering. Cooking shows that demonstrate culinary skills on television, often with celebrity chefs or unknown local housewives who may have won a competition, dominate daytime ratings. Local indigenous specialties and ways of cooking are the subjects of domestic and international tourism brochures. Metropolitan restaurants featuring international cuisines are filled with customers. Packaged Indian and foreign foods sell briskly in supermarkets, and indigenous street food and hole-in-the wall cafés have never been as popular. Yet lifestyle magazines tout healthy food, nutritious diets, locally sourced ingredients, and sustainable and green alternatives. India’s understanding of its own cultures and its complex historical and contemporary relations with foreign cultures are deeply evident in public conceptualizations of food as well as in culinary and gastronomic choices and lifestyles.

As Harvard anthropologist Theodore Bestor reminds us, the culinary imagination is a way a culture conceptualizes and imagines food. Generally, there is no “Indian” food but rather an enormous number of local, regional, caste-based ingredients and methods of preparation. These varieties of foods and their preparation have only been classified as “regional” and “local” cuisines since Indian independence in 1947 yet have enjoyed domestic and foreign patronage throughout most of India’s history. Because of this diversity and its celebration, most Indians appreciate a wide array of flavors and textures and are traditionally discerning consumers who eat seasonally, locally, and, to a large extent, sustainably. However, despite some resistance in recent years, the entry of multinational food corporations and their mimicking by Indian food giants, the industrialization of agriculture, the ubiquity of standardized food crops, and the standardization of food and tastes in urban areas have stimulated a flattening of the food terrain.

Food in India is an identity marker of caste, class, family, kinship, tribe affiliation, lineage, religiosity, ethnicity, and increasingly, of secular group identification.

In the recurring identity crises that globalization seems to encourage, one would expect that food would play a significant part in dialogues about nationalism and Indian identities. But food in India has been virtually absent from the academic discourse because of the diversity and spread of the gastronomic landscape. Things are different on the Internet. In response to the forces of globalization and Indian food blogs both teaching cookery and commenting on food, are mushrooming in cyberspace.

India has several thousand castes and tribes, sixteen official languages and several hundred dialects, six major world religions, and many ethnic and linguistic groups. Food in India is an identity marker of caste, class, family, kin- ship, tribe affiliation, lineage, religiosity, ethnicity, and increasingly, of secular group identification. How one eats, what one eats, with whom, when, and why, is key to understanding the Indian social landscape as well as the relationships, emotions, statuses, and transactions of people within it.

The aesthetic ways of knowing food—of being a gourmand and deriving pleasure from it—as well as ascetic responses to it—are lauded in ancient scriptural texts such as the Kamasutra and the Dharmaśāstras . But historically in India, food consumption has also paradoxically been governed by under- standings that lean toward asceticism and self-control as well. Traditional Ayurvedic (Hindu) and Unani (Muslim) medical systems have a tripartite categorization of the body on its reaction to foods. In Ayurveda, the body is classified as kapha (cold and phlegmy), vaata (mobile and flatulent), or pitta (hot and liverish), and food consumption is thus linked not only to overall feelings of well being and balance but to personality disorders and traits as well. Eating prescribed foods ( sattvic foods that cool the senses versus rajasic foods that inflame the passions) and doing yoga and breathing exercises to balance the body, spirit, and mind are seen as very basic self-care and self-fashioning.

This appreciation and negation of gastronomic pleasure is made more complex by caste- and religion-based purity as well as pollution taboos. With some exceptions, since the early twelfth century, upper-caste Hindus, Jains, and some regional groups are largely vegetarian and espouse ahimsa (nonviolence). Often upper castes will not eat onions, garlic, or processed food, believing them to violate principles of purity. Some lower-caste Hindus are meat eaters, but beef is forbidden as the cow is deemed sacred, and this purity barrier encompasses the entire caste and religious system.

As the eminent pioneering anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss noted, there is a sharp distinction between cooked and uncooked foods, with cooked or processed food capable of being contaminated with pollution easier than uncooked food. For upper-caste Hindus, raw rice is deemed pure even if served by a lower-caste person, but cooked rice can carry pollution when coming in contact with anything polluting, including low-caste servers. Religion also plays a part in dietetic rules; Muslims in India may eat beef, mutton, and poultry but not pork or shellfish; Christians may eat all meats and poultry; and Parsis eat more poultry and lamb than other meats. However, as many scholars have noted, because of the dominance of Hinduism in India and the striving of many lower-caste people for social mobility through imitation of higher-caste propensities, vegetarianism has evolved as the default diet in the subcontinent. Most meals would be considered complete without meat protein.

History and the Culinary Imagination

India sought to define itself gastronomically in the face of colonization beginning in the twelfth century. First, Central Asian invaders formed several dynasties known as the Sultanates from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries. Then, the great Mughal dynasty ruled from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The British came to trade as the East India Company, stayed as the Crown from the eighteenth century until 1847, and then had their heyday as the British Raj from 1857 to 1947. The Mughals brought new foods to the subcontinent from Central Asia, including dried fruits, pilafs, leavened wheat breads, stuffed meat, poultry, and fruits. The Mughals also brought new cooking processes such as baking bread and cooking meat on skewers in the tandoor (a clay oven), braising meats and poultry, tenderizing meats and game using yogurt protein, and making native cheese. They borrowed indigenous ingredients such as spices (cardamom, pepper, and clove) and vegetables (eggplant from India and carrots from Afghanistan) to cook their foods, creating a unique Mughlai haute courtly cuisine.

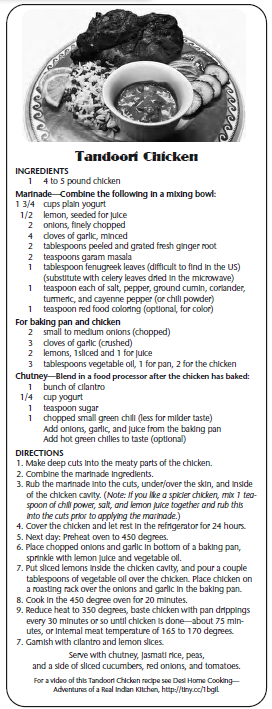

From princely kitchens, the cuisine has made its way over the centuries to restaurants in major cities. In Delhi, the capital of Mughal India, as food writer Chitrita Banerji informs us, the Moti Mahal Restaurant claims to have invented tandoori chicken. In neighborhood Punjabi and Mughlai restaurants in metropolitan centers, the menu usually consists of dishes of meat and poultry that are heavily marinated with spices, then grilled and braised in thick tomato or cream-based sauces and served with indigenous leavened breads such as naan and rice dishes with vegetables and meats such as pilafs and biryani . These foods, in popular, mass-customized versions, are the staples of the dhabhas (highway eateries) all over India.

The British and other Western powers—including most importantly Portugal—came to India in search of spices to preserve meats, but the age of empire dictated culinary exchanges. India received potatoes, tomatoes, and chilies from the New World, and all became an integral part of the cuisine. The British traded spices and provided the technology and plant material and even transported labor to produce sugar in the West Indies.1 Indian food historian Madhur Jaffrey states that as the British Raj set roots in the subcontinent, the English-trained Indian cooks (Hindi— khansama ) to make a fusion food of breads, mulligatawny soup (from the Tamil mulahathani —pepper water) mince pies and roasts, puddings, and trifles. These dishes were later adapted to the metropolitan Indian table for the officers of the Indian army and British-Indian club menus. “Military hotels”— restaurants where meat and poultry were served primarily to troop members and often run by Parsis or Muslims—became popular as the new concept of public dining gained popularity in urban India between 1860 and 1900. The oldest known cafe from this era is Leopold’s Cafe in south Bombay (now Mumbai), where military hotel culture first took root. Other “hotels” or eateries primarily served, as they still do, vegetarian domestic cuisine in a public setting. In Bangalore, neighborhood fast food eateries called Darshinis serve a quick menu of popular favorites such as idli (steamed rice dumplings), dosa (rice and lentil crepes), and puri (fried bread), while neighborhood restaurants called sagars —meaning “ocean” but denoting a type of restaurant that has many varieties drawn from a commercial restaurant chain called Sukh Sagar, or “ocean of pleasure”—serve a wide array of dishes from both north and south India, as well as Indian, Chinese, and “continental food.”

“Continental food” in contemporary India includes a combination of English breakfast dishes such as omelette and toast; bread, butter, jam; meat and potato “cutlets;” an eclectic combination of Western dishes such as pizza, pasta, and tomato soup with croutons; bastardized French cuisine of vegetable baked au gratin with cheese and cream sauces, liberally spiced to make them friendly to the Indian palate; caramel custard, trifle, fruit and jelly; and cream cakes for dessert. Western cuisine is no longer just British colonial cuisine with these additions but a mosaic of specific national cuisines where Italian, and more recently, Mexican foods dominate, as these cuisines easily absorb the spices needed to stimulate Indian palates. Indian-Chinese food, another ethnic variant, owes its popularity to a significant Chinese population in Calcutta, who Indianized Chinese food and, through a number of family-run restaurants, distributed it throughout India, so it is now considered “local.” Street vendors serve vernacular versions of spicy hakka noodles, spicy corn, and “gobi Manchurian,” a unique Indian-Chinese dish of fried spiced cauliflower.

Despite this diversity, there are regional differences. Some observers con- tend that the Punjab—the Western region of the Indo-Gangetic plain of north India—is the breadbasket of the country. The region grows vast quantities of wheat that is milled and made into leavened oven-baked breads such as naan; unleavened griddle-baked breads such a chapattis , phulkas , and rumali rotis ; and stuffed griddle-fried breads such as kulcha and paratha . These breads are often eaten with vegetable or meat dishes. In the south, by contrast, rice is the staple grain. It is dehusked, steamed, and often eaten with spice-based vegetables and sometimes meat-based gravy dishes. The one cooking process that seems to be common to the subcontinent is that of “tempering,” or flash-frying, spices to add flavor to cooked food.

Contemporary India celebrates cuisine from local areas and culinary processes. The history of India, combined with its size, population, and lack of adequate transportation, left it with a heritage of finely developed local delicacies and a connoisseur population trained in appreciation of difference, seasonality, methods of preparation, taste, regionality, climate, diversity, and history though largely in an unselfconscious manner until very recently. Though many regional delicacies are appreciated nationally, such as the methi masala (fenugreek chutney) of Gujarat or the fine, gauze-like, sweet suther pheni (a confection that resembles a bird’s nest) of Rajasthan, regional delicacies such as the Bengal River carp marinated in spicy ground mustard and cooked in strong- smelling mustard oil often seem exotic and sometimes strange to outsiders. Train travel in India is a culinary tasting journey with stations stocking local delicacies, making it incumbent on the traveler to “stock up” on legendary specialties. Domestic food tourism creates and sustains a vibrant culinary imagination and a gastronomic landscape, both within and outside India.

The Indian Meal

The Indian meal is a complex and little-understood phenomenon. “Typical” meals often include a main starch such as rice, sorghum, or wheat; vegetable or meat curries that are dry roasted or shallow wok fried; cured and dried vegetable dishes in sauces; and thick lentil soups, with different ingredients. Condiments might include masalas (a dry or wet powder of fine ground spices and herbs) plain yogurt, or a vegetable raita (yogurt dip, also called pachchadi in south India), salted pickles, fresh herbal and cooked chutneys, dried and fried wafers and salted papadums (fried lentil crisps), and occasionally dessert (called “sweetmeats”). Indian meals can have huge variations across the subcontinent, and any of these components in different orders and with different ingredients might constitute an Indian meal.

Rice is a powerful symbol of both hunger and want as well as fulfillment and fertility. Until the late nineteenth century, however, only the wealthy ate rice, and most Indians consumed millet and sorghum.

When a multi-dish meal is served on a large platter in north India, the serving utensil is usually made of silver for purity. A banana leaf might be the main platter for a south Indian festival. In either case, there are various small bowls for each dish. This kind of meal is called a thali and is named for the platter on which it is served. The meal is eaten first with a sweet, followed by all the dishes served simultaneously and mixed together with the rice, based on the eater’s discretion. The meal ends with yogurt, which is thought to cool the body, and then followed by sweets and/or fruit. Festival meals usually end with a digestive in the form of a paan (betel leaf and nut folded together), which again has regional variations of style and taste.

Rice is a powerful symbol of both hunger and want as well as fulfillment and fertility. Until the late nineteenth century, however, only the wealthy ate rice, and most Indians consumed millet and sorghum. Nevertheless, the powerful symbolism of rice as a sign of fertility for many castes makes it part of marriage rites. Welcoming a new bride to the family home includes having her kick over a measure of rice to indicate that she brings prosperity to the household. A traditional test of a worthy daughter-in-law is her ability to “wash” the rice properly and to gauge the right amount of water it draws while cooking. Rice is still a symbol of wealth, and those families who have access to “wetland” where rice paddies grow are still thought to be wealthy and well endowed. Long grain scented basmati rice is India’s most popular variety and is valued in foreign markets as well. Efforts of the Indian government to protect Indian basmati rice failed, and now two types of American basmati exist, a situation many Indians consider shameful.

Gastronomic Calendars, Rituals, and Seasonality

In India as elsewhere, food culture is shaped by climate, land, and access to natural resources. The food system emphasizes eating agricultural and natural produce “in season,” such as mangoes and local greens during the summer, pumpkins during the rainy monsoon months, and root vegetables during the winter months. This emphasis is based upon a belief that in-season foods are more potent, tastier, and of greater nutritional value, although the yearround availability of many foods due to technology are beginning to change eating habits.

Cooks who are native to India are aware of culinary cycles and of multiple-dish recipes using fruits and vegetables of the season, some deemed “favorites” within caste groups and families. For example, prior to the ripened mango harvest of May and June, tiny unripe mangoes are harvested and pick- led in brine. The ripe mango and the pickled mango are the same species but are clearly different culinary tropes with different characteristics that are some- times attributed with fortifying, healing, auspicious, and celebratory values, based on taste, color, and combination. Connoisseurs are aware of desirable foods in local areas and sometimes travel great distances to acquire the first or best product of the season. Seasonality and regionality are also part of wed- ding celebrations, funerary rites, and domestic feasts. The winter peasant menu of the Punjab sarson ka saag , a stew of spicy mustard greens believed to “heat” the body, and makki ki roti ( griddled corn flatbreads), are imported to haute tables in Delhi restaurants as “rustic” fare.

Religious festivals also align with culinary cycles, festivals, or sacred periods of the year that are often associated with offerings to the gods and feasting on certain foods. The south Indian Harvest festival of Pongal in February is accompanied by a feast of harvested rice cooked with lentils in three different dishes, shakkarai pongal (Tamil-sweet), ven pongal (Tamil-savory), and akkara vadashal (Tamil-milk), accompanied by a stew of nine different winter vegetables and beans, offered first to tutelary deities and then consumed as consecrated food. Temples, especially those dedicated to the Hindu God Vishnu, have a long history of developed culinary traditions and food- offering aesthetics. The Krishna Temple in the south Indian temple town of Udupi is known throughout India for the distribution of free seasonal meals to thousands of devotees. Other temples are known for offerings of certain sweets or savories of that region or enormous and detailed menus of offerings from the land.

The Globalization of Indian Food

Although it has never had a standardized diet, India has traditionally “imagined” its cuisine with respect to the incorporation and domestication of “foreign” influences. In the past two decades, with India becoming an economic powerhouse, a variety of multinational fast food companies have entered the previously protected Indian culinary landscape. They include Pizza Hut, Mc- Donald’s, KFC, Pepsico, and, most recently, Taco Bell. These companies have had to “Indianize” and self-domesticate to conquer the notoriously difficult-to-please Indian palate.2 Today, urban fast food chains in India have become common and are transforming the middle class diet.

At the same time, local food purveyors have taken complex regional recipes and modified them for ease of industrial production, leading to a pack- aged food boom in India.3 The Indian food market of $182 billion is believed to be growing at a rapid clip of 13 percent.4 Indian precooked packaged foods empires such as MTR, SWAD, Haldirams, and Pataks have gone global, avail- able wherever Indians now live, leading a quiet yet unrecognized revolution in eating habits. Formerly, the focus was upon rural, natural, fresh, and prepared on-site food. Now, there is a shift in emphasis to industrialized, processed food. These developments are partially reengineering local and caste-based special- ties for mass production, distribution, and consumption, changing past notions of what is traditional or valued.

Some scholars have suggested that Indian food is filtered through Great Britain to the world, though diasporic Indian groups have also contributed. North American eateries serve curries and rice, tandoori chicken , naan , and chicken tikka masala (said to be invented in Glasgow), while the Japanese make karai and rice, demonstrating the attractiveness of “exotic” India’s cultural power and reach.

The cultures of contemporary Indian cuisine, including the politics, food processes, production, and consumption, are simultaneously changing and exhilarating. Further innovation and increased attention to Indian cuisine will almost certainly occur and promises to be an exciting area of innovation and critical research in the future.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Sidney Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin Books, 1986).

- Krishnenu Ray and Tulasi Srinivas, eds., Curried Cultures: Globalization, Food, South Asia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

- Tulasi Srinivas, “Everyday Exotic: Transnational Spaces and Contemporary Foodways in Bangalore,” Food, Culture and Society: An International Journal of Multidisciplinary Re- search 10 1 (2007): 85–107.

- Aroonim Bhuyan, “India’s Food Industry on the Path of High Growth,” Indo-Asian News Service , 2010, accessed July 10, 2011, see http://www.corecentre.co.in/Database/Docs/Doc- Files/food.pdf.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Achaya, K.T. Indian Food: A Historical Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1994.

Appadurai, Arjun. “Gastro-Politics in Hindu South Asia.” American Ethnologist8 no. 3, Symbolism and Cognition(1981): 494–551.

——————. “How to Make a National Cuisine: Cookbooks in Contemporary India.” Comparative Studies in Society and History30 no. 1 (1988): 3–24.

Bagla, Pallava and Subhadra Menon. “The Story of Rice.” The India Magazine9 (February 1989): 60–70.

Banerji, Chitrita. Eating Indian: An Odyssey into the Food and Culture of the Land of Spices. London: Bloomsbury, 2007.

Bestor, Theodore. “Cuisine and Identity in Contemporary Japan.” Routledge Handbook of Japanese Culture and Society. London: Routledge Press, 2011.

Bhuyan, Aroonim. “India’s Food Industry on the Path of High Growth.” 2010. See http://www.corecentre.co.in/Database/Docs/DocFiles/food.pdf.

Collingham, Lizzie. Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Goody, Jack. Cooking, Cuisine and Class: A Study in Comparative Sociology . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Jaffrey, Madhur. A Taste of India. London: Pavilion, 1989.

Khare, Ravindra S., ed. The Eternal Food: Gastronomic Ideas and Experiences of Hindus and Buddhists. Binghamton: SUNY Press, 1982. See also Mount Goverdhan in same volume.

Mintz, Sidney. W. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

Olivelle, Patrick. From Feast to Fast: Food and the Indian Ascetic in Collected Essays of Patrick Olivelle . Firenze: Firenze University Press, 1999.

Ray, Krishnenu and Tulasi Srinivas, eds. Curried Cultures: Globalization, Food, South Asia . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Sen, Amartya. Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlements and Deprivation. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982.

Sen, Colleen Taylor. Food Culture in India. London: Greenwood Press, 2004.

Srinivas, M.N. The Cohesive Role of Sankritization and Other Essays. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, 1962.

Srinivas, Tulasi. “Everyday Exotic: Transnational Spaces and Contemporary Foodways in Bangalore.” Food, Culture and Society 10 no. 1 (2007).

Srinivas, Tulasi. “As Mother Made It: The Cosmopolitan Indian Family, ‘Authentic’ Food and the Construction of Cultural Utopia.” International Journal of Sociology of the Family 32 no. 2 (2006): 199–221.

Toomey, Paul. “Mountain of Food, Mountain of Love: Ritual Inversion in the Annakūta Feast at Mount Govardhan.” Ravindra S. Khare, ed. The Eternal Food: Gastronomic Ideas and Experiences of Hindus and Buddhists. Albany: SUNY Press, 1992.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- The AAS First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Hindu-Christian Dialogue in India

Introduction

India, often referred to as Bharat or Hindusthan , is a land of plurality, diversity, and complexity. Although India is strongly influenced by Hindu beliefs and practices, it has also demonstrated an amazing sense of tolerance, acceptance, and adaptability with other faiths and religions over the centuries. Historically, there have been occasional clashes between the religious communities, and yet many religions, religious movements, and other faiths have emerged and flourished in India—often tolerating each other and sometimes absorbing certain precepts and practices so as to enrich each others’ spiritual journey.

Christianity in India, though perceived to be a comparatively recent phenomenon, can be traced back to at least the third century, if not to the very first century. The strong tradition of Saint Thomas Christians points to the arrival of the gospel through one of Jesus’s disciples, Thomas, in the first century. Without going into the merits or demerits of this tradition, we can be assured that the Christian faith was present in India long before the emergence of the modern missionary era, prospering for 2000 years alongside the dominant Hindu society. The fact that many forms and practices of Hinduism have been adopted by the Christian community in India is an indication of mutual enrichment and cohabitation.

Christians in India have demonstrated many responses to the dominant Hindu and, to a certain extent, the Muslim, Sikh, and Buddhist communities. Christian perceptions, attitudes, and approaches to each religion range from highly negative to an overtly positive interaction. On the one side, most early missionaries (in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries), who were largely products of the Pietistic movement, looked at the native religions as sinful if not Satanic. Hence, their approach to them was more condemnatory. In contrast, particularly in the middle of the twentieth century, a more sympathetic and positive attitude emerged among the Christian missionaries—some of whom even abandoned their missionary vocation and absorbed many religious precepts and practices of the native religions into their own faith. This often led to syncretistic religious practices. However, a large segment of the Christian community in India probably is more inclined to live harmoniously with the people of other faiths, often entering into what we call “informal dialogue” over many central issues of faith and practices. “There are many situations in India where informal dialogue has long been an established reality made possible and often inevitable by the proximity of neighbors of different faiths.” 1 This aspect of informal dialogue is part and parcel of their day-to-day life, but apparently has not been taken seriously either by the theologians or church leaders. While this type of informal dialogue perhaps has more potential in making a difference with regard to Christian life and witness in India, sadly very little attention is given to informing, equipping, and mobilizing Christians in India to undertake such informal dialogue with people of other faiths.

Such inattention to the potential found in informal dialogue may have significant consequences since twenty-first-century Christian mission in India will be radically different from that of previous centuries. While acknowledging some damaging and disturbing trends that may have adverse effects on the life and witness of the Christian community, it must not be forgotten that a huge percentage of both the literate and the educated masses are showing signs of openness and positive inclinations towards a deeper and better understanding of Christianity and particularly the person of Jesus Christ. In such a context, it is extremely important to consciously develop positive and constructive ways of establishing a neutral platform from which ongoing dialogue at various levels can be articulated and undertaken. Often it is not the precepts of the Christian faith that are offensive to the people of India; rather, it is the way the Christians present them in their life and practice (or in some instances, fail to practice what they proclaim) that offends people. In the wake of emerging Hindu fundamentalism in India, it is imperative that the Christian community grapple with how to sympathetically interact with people of other faiths so that many misperceptions and misunderstandings can be addressed, thus paving the way for articulating Christian witness in a more constructive manner.

Overview of Essay