Racism, bias, and discrimination

Racism is a form of prejudice that generally includes negative emotional reactions to members of a group, acceptance of negative stereotypes, and racial discrimination against individuals; in some cases it can lead to violence.

Discrimination refers to the differential treatment of different age, gender, racial, ethnic, religious, national, ability identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic, and other groups at the individual level and the institutional/structural level. Discrimination is usually the behavioral manifestation of prejudice and involves negative, hostile, and injurious treatment of members of rejected groups.

Adapted from the APA Dictionary of Psychology

Resources from APA

Racial Equity Action Plan Progress and Impact Report

Update on APA’s efforts toward dismantling systemic racism in psychology and society

Empowering youth of color

The psychologist is one of 12 global leaders who received a $20 million grant from Melinda French Gates.

Implicit theories concerning the intelligence of individuals with Down syndrome

Think professionals who work with people with disabilities are immune to bias? Think again

Combating stigma against patients

How clinicians can overcome bias and provide better treatment

More resources about racism

What APA is doing

Race, ethnicity, and religion

APA Services advocates for the equal treatment of people of all races, religions, and ethnicities, as well as funding for federal programs that address health disparities in these groups.

Equity, diversity, and inclusion

Inclusive language guidelines

APA’s commitment to addressing systemic racism

APA’s action plan for addressing inequality

APA’s apology to people of color in the U.S.

Confronting past wrongs and building an equitable future

Stigma of Disease and Disability

The Psychology of Hate

Microaggressions and Traumatic Stress

Addressing Cultural Complexities in Counseling and Clinical Practice

Trauma and Racial Minority Immigrants

Magination Press children’s books

Bernice Sandler and the Fight for Title IX

Lulu the One and Only

There's a Cat in Our Class!

Algo Le Pasó a Mi Papá

Something Happened to My Dad

Journal special issues

Training and Educating Antiracist Psychologists

Asian America and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Dismantling Racism in the Field of Psychology and Beyond

Understanding, Unpacking and Eliminating Health Disparities

Recentering AAPI Narratives as Social Justice Praxis

Ethnic psychological associations

- American Arab, Middle Eastern, and North African Psychological Association

- The Association of Black Psychologists

- Asian American Psychological Association

- National Latinx Psychological Association

- Society of Indian Psychologists

Related resources

- Protecting and Defending our People: Nakni tushka anowa (The Warrior’s Path) Final Report (PDF, 8.64MB) APA Division 45 Warrior’s Path Presidential Task Force (2020)

- Society for Community Research and Action (APA Division 27) Antiracism / Antioppression email series

- Society of Counseling Psychology (APA Division 17) Social justice resources

- Talking About Race | National Museum of African American History and Culture Tools and guidance for discussions of race

- InnoPsych therapists of color search

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Toll of QAnon on families of followers

The urgent message coming from boys

Your kid can’t name three branches of government? He’s not alone.

Mahzarin Banaji opened the symposium on Tuesday by recounting the “implicit association” experiments she had done at Yale and at Harvard. The final talk is today at 9 a.m.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Turning a light on our implicit biases

Brett Milano

Harvard Correspondent

Social psychologist details research at University-wide faculty seminar

Few people would readily admit that they’re biased when it comes to race, gender, age, class, or nationality. But virtually all of us have such biases, even if we aren’t consciously aware of them, according to Mahzarin Banaji, Cabot Professor of Social Ethics in the Department of Psychology, who studies implicit biases. The trick is figuring out what they are so that we can interfere with their influence on our behavior.

Banaji was the featured speaker at an online seminar Tuesday, “Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People,” which was also the title of Banaji’s 2013 book, written with Anthony Greenwald. The presentation was part of Harvard’s first-ever University-wide faculty seminar.

“Precipitated in part by the national reckoning over race, in the wake of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others, the phrase ‘implicit bias’ has almost become a household word,” said moderator Judith Singer, Harvard’s senior vice provost for faculty development and diversity. Owing to the high interest on campus, Banaji was slated to present her talk on three different occasions, with the final one at 9 a.m. Thursday.

Banaji opened on Tuesday by recounting the “implicit association” experiments she had done at Yale and at Harvard. The assumptions underlying the research on implicit bias derive from well-established theories of learning and memory and the empirical results are derived from tasks that have their roots in experimental psychology and neuroscience. Banaji’s first experiments found, not surprisingly, that New Englanders associated good things with the Red Sox and bad things with the Yankees.

She then went further by replacing the sports teams with gay and straight, thin and fat, and Black and white. The responses were sometimes surprising: Shown a group of white and Asian faces, a test group at Yale associated the former more with American symbols though all the images were of U.S. citizens. In a further study, the faces of American-born celebrities of Asian descent were associated as less American than those of white celebrities who were in fact European. “This shows how discrepant our implicit bias is from even factual information,” she said.

How can an institution that is almost 400 years old not reveal a history of biases, Banaji said, citing President Charles Eliot’s words on Dexter Gate: “Depart to serve better thy country and thy kind” and asking the audience to think about what he may have meant by the last two words.

She cited Harvard’s current admission strategy of seeking geographic and economic diversity as examples of clear progress — if, as she said, “we are truly interested in bringing the best to Harvard.” She added, “We take these actions consciously, not because they are easy but because they are in our interest and in the interest of society.”

Moving beyond racial issues, Banaji suggested that we sometimes see only what we believe we should see. To illustrate she showed a video clip of a basketball game and asked the audience to count the number of passes between players. Then the psychologist pointed out that something else had occurred in the video — a woman with an umbrella had walked through — but most watchers failed to register it. “You watch the video with a set of expectations, one of which is that a woman with an umbrella will not walk through a basketball game. When the data contradicts an expectation, the data doesn’t always win.”

Expectations, based on experience, may create associations such as “Valley Girl Uptalk” is the equivalent of “not too bright.” But when a quirky way of speaking spreads to a large number of young people from certain generations, it stops being a useful guide. And yet, Banaji said, she has been caught in her dismissal of a great idea presented in uptalk. Banaji stressed that the appropriate course of action is not to ask the person to change the way she speaks but rather for her and other decision makers to know that using language and accents to judge ideas is something people at their own peril.

Banaji closed the talk with a personal story that showed how subtler biases work: She’d once turned down an interview because she had issues with the magazine for which the journalist worked.

The writer accepted this and mentioned she’d been at Yale when Banaji taught there. The professor then surprised herself by agreeing to the interview based on this fragment of shared history that ought not to have influenced her. She urged her colleagues to think about positive actions, such as helping that perpetuate the status quo.

“You and I don’t discriminate the way our ancestors did,” she said. “We don’t go around hurting people who are not members of our own group. We do it in a very civilized way: We discriminate by who we help. The question we should be asking is, ‘Where is my help landing? Is it landing on the most deserved, or just on the one I shared a ZIP code with for four years?’”

To subscribe to short educational modules that help to combat implicit biases, visit outsmartinghumanminds.org .

Share this article

You might like.

New book by Nieman Fellow explores pain, frustration in efforts to help loved ones break free of hold of conspiracy theorists

When we don’t listen, we all suffer, says psychologist whose new book is ‘Rebels with a Cause’

Efforts launched to turn around plummeting student scores in U.S. history, civics, amid declining citizen engagement across nation

You want to be boss. You probably won’t be good at it.

Study pinpoints two measures that predict effective managers

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Discrimination and Prejudice — Racial Discrimination

Essays on Racial Discrimination

Themes in lorraine hansberry's "a raisin in the sun", racial discrimination and sexism in william shakespeare's plays, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Issue of Racial Discrimination in Beyoncé's Song "Formation"

Racial discrimination and microaggressions and its consequences, effects of racial discrimination on health, employment, and housing in the us, racism in society, its effects and ways to overcome, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Critical Analysis of Kaepernicks Act of Kneeling

Race discrimination and its existence nowadays, racism as a result of discrimination towards the minorities in a community, inequality in the marrow of tradition, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Causes and Effects of Racism in Born a Crime

The hidden impact of internalized racism on psychology and society, the case of trayvon martin and stand-your-ground law in the us, the importance of analyzing racist depictions in films, black oppression in america: jim crow laws to today’s society , the flowers by alice walker: the impact of racism on children, trayvon martin case: self-defense vs deadly force, racial profiling: it’s not in the past, the difference between the lives of black and whites during slavery, the issue of racial prejudice in american literature, racial & gender inequalities in the workplace, workplace discrimination against african americans in the us, black boy by richard wright: being a minority in the deep south, african americans who started the battle for civil rights, gregory mantsio's 'class in america': the issue of prejudice in society, prejudice, racism and american dream in gregory mantsios' 'class in america', the overrepresentation of certain groups of society in the criminal justice system, conflicting views on the idea of affirmative action, racial stereotyping in the movie straight outta compton, rise of anti-muslim sentiment: islamophobia, relevant topics.

- Racial Profiling

- Discrimination

- Gender Discrimination

- Hate Speech

- Fat Shaming

- Multiculturalism

- Transphobia

- Gun Control

- Martin Luther King

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Bibliography

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

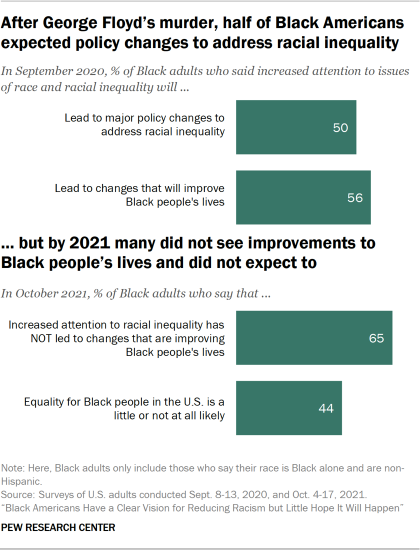

A pandemic that disproportionately affected communities of color, roadblocks that obstructed efforts to expand the franchise and protect voting discrimination, a growing movement to push anti-racist curricula out of schools – events over the past year have only underscored how prevalent systemic racism and bias is in America today.

What can be done to dismantle centuries of discrimination in the U.S.? How can a more equitable society be achieved? What makes racism such a complicated problem to solve? Black History Month is a time marked for honoring and reflecting on the experience of Black Americans, and it is also an opportunity to reexamine our nation’s deeply embedded racial problems and the possible solutions that could help build a more equitable society.

Stanford scholars are tackling these issues head-on in their research from the perspectives of history, education, law and other disciplines. For example, historian Clayborne Carson is working to preserve and promote the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and religious studies scholar Lerone A. Martin has joined Stanford to continue expanding access and opportunities to learn from King’s teachings; sociologist Matthew Clair is examining how the criminal justice system can end a vicious cycle involving the disparate treatment of Black men; and education scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students.

Learn more about these efforts and other projects examining racism and discrimination in areas like health and medicine, technology and the workplace below.

Update: Jan. 27, 2023: This story was originally published on Feb. 16, 2021, and has been updated on a number of occasions to include new content.

Understanding the impact of racism; advancing justice

One of the hardest elements of advancing racial justice is helping everyone understand the ways in which they are involved in a system or structure that perpetuates racism, according to Stanford legal scholar Ralph Richard Banks.

“The starting point for the center is the recognition that racial inequality and division have long been the fault line of American society. Thus, addressing racial inequity is essential to sustaining our nation, and furthering its democratic aspirations,” said Banks , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and co-founder of the Stanford Center for Racial Justice .

This sentiment was echoed by Stanford researcher Rebecca Hetey . One of the obstacles in solving inequality is people’s attitudes towards it, Hetey said. “One of the barriers of reducing inequality is how some people justify and rationalize it.”

How people talk about race and stereotypes matters. Here is some of that scholarship.

For Black Americans, COVID-19 is quickly reversing crucial economic gains

Research co-authored by SIEPR’s Peter Klenow and Chad Jones measures the welfare gap between Black and white Americans and provides a way to analyze policies to narrow the divide.

How an ‘impact mindset’ unites activists of different races

A new study finds that people’s involvement with Black Lives Matter stems from an impulse that goes beyond identity.

For democracy to work, racial inequalities must be addressed

The Stanford Center for Racial Justice is taking a hard look at the policies perpetuating systemic racism in America today and asking how we can imagine a more equitable society.

The psychological toll of George Floyd’s murder

As the nation mourned the death of George Floyd, more Black Americans than white Americans felt angry or sad – a finding that reveals the racial disparities of grief.

Seven factors contributing to American racism

Of the seven factors the researchers identified, perhaps the most insidious is passivism or passive racism, which includes an apathy toward systems of racial advantage or denial that those systems even exist.

Scholars reflect on Black history

Humanities and social sciences scholars reflect on “Black history as American history” and its impact on their personal and professional lives.

The history of Black History Month

It's February, so many teachers and schools are taking time to celebrate Black History Month. According to Stanford historian Michael Hines, there are still misunderstandings and misconceptions about the past, present, and future of the celebration.

Numbers about inequality don’t speak for themselves

In a new research paper, Stanford scholars Rebecca Hetey and Jennifer Eberhardt propose new ways to talk about racial disparities that exist across society, from education to health care and criminal justice systems.

Changing how people perceive problems

Drawing on an extensive body of research, Stanford psychologist Gregory Walton lays out a roadmap to positively influence the way people think about themselves and the world around them. These changes could improve society, too.

Welfare opposition linked to threats of racial standing

Research co-authored by sociologist Robb Willer finds that when white Americans perceive threats to their status as the dominant demographic group, their resentment of minorities increases. This resentment leads to opposing welfare programs they believe will mainly benefit minority groups.

Conversations about race between Black and white friends can feel risky, but are valuable

New research about how friends approach talking about their race-related experiences with each other reveals concerns but also the potential that these conversations have to strengthen relationships and further intergroup learning.

Defusing racial bias

Research shows why understanding the source of discrimination matters.

Many white parents aren’t having ‘the talk’ about race with their kids

After George Floyd’s murder, Black parents talked about race and racism with their kids more. White parents did not and were more likely to give their kids colorblind messages.

Stereotyping makes people more likely to act badly

Even slight cues, like reading a negative stereotype about your race or gender, can have an impact.

Why white people downplay their individual racial privileges

Research shows that white Americans, when faced with evidence of racial privilege, deny that they have benefited personally.

Clayborne Carson: Looking back at a legacy

Stanford historian Clayborne Carson reflects on a career dedicated to studying and preserving the legacy of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

How race influences, amplifies backlash against outspoken women

When women break gender norms, the most negative reactions may come from people of the same race.

Examining disparities in education

Scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students. Annamma’s research examines how schools contribute to the criminalization of Black youths by creating a culture of punishment that penalizes Black children more harshly than their white peers for the same behavior. Her work shows that youth of color are more likely to be closely watched, over-represented in special education, and reported to and arrested by police.

“These are all ways in which schools criminalize Black youth,” she said. “Day after day, these things start to sediment.”

That’s why Annamma has identified opportunities for teachers and administrators to intervene in these unfair practices. Below is some of that research, from Annamma and others.

New ‘Segregation Index’ shows American schools remain highly segregated by race, ethnicity, and economic status

Researchers at Stanford and USC developed a new tool to track neighborhood and school segregation in the U.S.

New evidence shows that school poverty shapes racial achievement gaps

Racial segregation leads to growing achievement gaps – but it does so entirely through differences in school poverty, according to new research from education Professor Sean Reardon, who is launching a new tool to help educators, parents and policymakers examine education trends by race and poverty level nationwide.

School closures intensify gentrification in Black neighborhoods nationwide

An analysis of census and school closure data finds that shuttering schools increases gentrification – but only in predominantly Black communities.

Ninth-grade ethnic studies helped students for years, Stanford researchers find

A new study shows that students assigned to an ethnic studies course had longer-term improvements in attendance and graduation rates.

Teaching about racism

Stanford sociologist Matthew Snipp discusses ways to educate students about race and ethnic relations in America.

Stanford scholar uncovers an early activist’s fight to get Black history into schools

In a new book, Assistant Professor Michael Hines chronicles the efforts of a Chicago schoolteacher in the 1930s who wanted to remedy the portrayal of Black history in textbooks of the time.

How disability intersects with race

Professor Alfredo J. Artiles discusses the complexities in creating inclusive policies for students with disabilities.

Access to program for black male students lowered dropout rates

New research led by Stanford education professor Thomas S. Dee provides the first evidence of effectiveness for a district-wide initiative targeted at black male high school students.

How school systems make criminals of Black youth

Stanford education professor Subini Ancy Annamma talks about the role schools play in creating a culture of punishment against Black students.

Reducing racial disparities in school discipline

Stanford psychologists find that brief exercises early in middle school can improve students’ relationships with their teachers, increase their sense of belonging and reduce teachers’ reports of discipline issues among black and Latino boys.

Science lessons through a different lens

In his new book, Science in the City, Stanford education professor Bryan A. Brown helps bridge the gap between students’ culture and the science classroom.

Teachers more likely to label black students as troublemakers, Stanford research shows

Stanford psychologists Jennifer Eberhardt and Jason Okonofua experimentally examined the psychological processes involved when teachers discipline black students more harshly than white students.

Why we need Black teachers

Travis Bristol, MA '04, talks about what it takes for schools to hire and retain teachers of color.

Understanding racism in the criminal justice system

Research has shown that time and time again, inequality is embedded into all facets of the criminal justice system. From being arrested to being charged, convicted and sentenced, people of color – particularly Black men – are disproportionately targeted by the police.

“So many reforms are needed: police accountability, judicial intervention, reducing prosecutorial power and increasing resources for public defenders are places we can start,” said sociologist Matthew Clair . “But beyond piecemeal reforms, we need to continue having critical conversations about transformation and the role of the courts in bringing about the abolition of police and prisons.”

Clair is one of several Stanford scholars who have examined the intersection of race and the criminal process and offered solutions to end the vicious cycle of racism. Here is some of that work.

Police Facebook posts disproportionately highlight crimes involving Black suspects, study finds

Researchers examined crime-related posts from 14,000 Facebook pages maintained by U.S. law enforcement agencies and found that Facebook users are exposed to posts that overrepresent Black suspects by 25% relative to local arrest rates.

Supporting students involved in the justice system

New data show that a one-page letter asking a teacher to support a youth as they navigate the difficult transition from juvenile detention back to school can reduce the likelihood that the student re-offends.

Race and mass criminalization in the U.S.

Stanford sociologist discusses how race and class inequalities are embedded in the American criminal legal system.

New Stanford research lab explores incarcerated students’ educational paths

Associate Professor Subini Annamma examines the policies and practices that push marginalized students out of school and into prisons.

Derek Chauvin verdict important, but much remains to be done

Stanford scholars Hakeem Jefferson, Robert Weisberg and Matthew Clair weigh in on the Derek Chauvin verdict, emphasizing that while the outcome is important, much work remains to be done to bring about long-lasting justice.

A ‘veil of darkness’ reduces racial bias in traffic stops

After analyzing 95 million traffic stop records, filed by officers with 21 state patrol agencies and 35 municipal police forces from 2011 to 2018, researchers concluded that “police stops and search decisions suffer from persistent racial bias.”

Stanford big data study finds racial disparities in Oakland, Calif., police behavior, offers solutions

Analyzing thousands of data points, the researchers found racial disparities in how Oakland officers treated African Americans on routine traffic and pedestrian stops. They suggest 50 measures to improve police-community relations.

Race and the death penalty

As questions about racial bias in the criminal justice system dominate the headlines, research by Stanford law Professor John J. Donohue III offers insight into one of the most fraught areas: the death penalty.

Diagnosing disparities in health, medicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted communities of color and has highlighted the health disparities between Black Americans, whites and other demographic groups.

As Iris Gibbs , professor of radiation oncology and associate dean of MD program admissions, pointed out at an event sponsored by Stanford Medicine: “We need more sustained attention and real action towards eliminating health inequities, educating our entire community and going beyond ‘allyship,’ because that one fizzles out. We really do need people who are truly there all the way.”

Below is some of that research as well as solutions that can address some of the disparities in the American healthcare system.

Stanford researchers testing ways to improve clinical trial diversity

The American Heart Association has provided funding to two Stanford Medicine professors to develop ways to diversify enrollment in heart disease clinical trials.

Striking inequalities in maternal and infant health

Research by SIEPR’s Petra Persson and Maya Rossin-Slater finds wealthy Black mothers and infants in the U.S. fare worse than the poorest white mothers and infants.

More racial diversity among physicians would lead to better health among black men

A clinical trial in Oakland by Stanford researchers found that black men are more likely to seek out preventive care after being seen by black doctors compared to non-black doctors.

A better measuring stick: Algorithmic approach to pain diagnosis could eliminate racial bias

Traditional approaches to pain management don’t treat all patients the same. AI could level the playing field.

5 questions: Alice Popejoy on race, ethnicity and ancestry in science

Alice Popejoy, a postdoctoral scholar who studies biomedical data sciences, speaks to the role – and pitfalls – of race, ethnicity and ancestry in research.

Stanford Medicine community calls for action against racial injustice, inequities

The event at Stanford provided a venue for health care workers and students to express their feelings about violence against African Americans and to voice their demands for change.

Racial disparity remains in heart-transplant mortality rates, Stanford study finds

African-American heart transplant patients have had persistently higher mortality rates than white patients, but exactly why still remains a mystery.

Finding the COVID-19 Victims that Big Data Misses

Widely used virus tracking data undercounts older people and people of color. Scholars propose a solution to this demographic bias.

Studying how racial stressors affect mental health

Farzana Saleem, an assistant professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education, is interested in the way Black youth and other young people of color navigate adolescence—and the racial stressors that can make the journey harder.

Infants’ race influences quality of hospital care in California

Disparities exist in how babies of different racial and ethnic origins are treated in California’s neonatal intensive care units, but this could be changed, say Stanford researchers.

Immigrants don’t move state-to-state in search of health benefits

When states expand public health insurance to include low-income, legal immigrants, it does not lead to out-of-state immigrants moving in search of benefits.

Excess mortality rates early in pandemic highest among Blacks

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been starkly uneven across race, ethnicity and geography, according to a new study led by SHP's Maria Polyakova.

Decoding bias in media, technology

Driving Artificial Intelligence are machine learning algorithms, sets of rules that tell a computer how to solve a problem, perform a task and in some cases, predict an outcome. These predictive models are based on massive datasets to recognize certain patterns, which according to communication scholar Angele Christin , sometimes come flawed with human bias .

“Technology changes things, but perhaps not always as much as we think,” Christin said. “Social context matters a lot in shaping the actual effects of the technological tools. […] So, it’s important to understand that connection between humans and machines.”

Below is some of that research, as well as other ways discrimination unfolds across technology, in the media, and ways to counteract it.

IRS disproportionately audits Black taxpayers

A Stanford collaboration with the Department of the Treasury yields the first direct evidence of differences in audit rates by race.

Automated speech recognition less accurate for blacks

The disparity likely occurs because such technologies are based on machine learning systems that rely heavily on databases of English as spoken by white Americans.

New algorithm trains AI to avoid bad behaviors

Robots, self-driving cars and other intelligent machines could become better-behaved thanks to a new way to help machine learning designers build AI applications with safeguards against specific, undesirable outcomes such as racial and gender bias.

Stanford scholar analyzes responses to algorithms in journalism, criminal justice

In a recent study, assistant professor of communication Angèle Christin finds a gap between intended and actual uses of algorithmic tools in journalism and criminal justice fields.

Move responsibly and think about things

In the course CS 181: Computers, Ethics and Public Policy , Stanford students become computer programmers, policymakers and philosophers to examine the ethical and social impacts of technological innovation.

Homicide victims from Black and Hispanic neighborhoods devalued

Social scientists found that homicide victims killed in Chicago’s predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods received less news coverage than those killed in mostly white neighborhoods.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

AI Index Diversity Report: An Unmoving Needle

Stanford HAI’s 2021 AI Index reveals stalled progress in diversifying AI and a scarcity of the data needed to fix it.

Identifying discrimination in the workplace and economy

From who moves forward in the hiring process to who receives funding from venture capitalists, research has revealed how Blacks and other minority groups are discriminated against in the workplace and economy-at-large.

“There is not one silver bullet here that you can walk away with. Hiring and retention with respect to employee diversity are complex problems,” said Adina Sterling , associate professor of organizational behavior at the Graduate School of Business (GSB).

Sterling has offered a few places where employers can expand employee diversity at their companies. For example, she suggests hiring managers track data about their recruitment methods and the pools that result from those efforts, as well as examining who they ultimately hire.

Here is some of that insight.

How To: Use a Scorecard to Evaluate People More Fairly

A written framework is an easy way to hold everyone to the same standard.

Archiving Black histories of Silicon Valley

A new collection at Stanford Libraries will highlight Black Americans who helped transform California’s Silicon Valley region into a hub for innovation, ideas.

Race influences professional investors’ judgments

In their evaluations of high-performing venture capital funds, professional investors rate white-led teams more favorably than they do black-led teams with identical credentials, a new Stanford study led by Jennifer L. Eberhardt finds.

Who moves forward in the hiring process?

People whose employment histories include part-time, temporary help agency or mismatched work can face challenges during the hiring process, according to new research by Stanford sociologist David Pedulla.

How emotions may result in hiring, workplace bias

Stanford study suggests that the emotions American employers are looking for in job candidates may not match up with emotions valued by jobseekers from some cultural backgrounds – potentially leading to hiring bias.

Do VCs really favor white male founders?

A field experiment used fake emails to measure gender and racial bias among startup investors.

Can you spot diversity? (Probably not)

New research shows a “spillover effect” that might be clouding your judgment.

Can job referrals improve employee diversity?

New research looks at how referrals impact promotions of minorities and women.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 18 May 2023

A systemic approach to the psychology of racial bias within individuals and society

- Allison L. Skinner-Dorkenoo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1220-4791 1 ,

- Meghan George ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6917-6061 2 ,

- James E. Wages III ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4205-9807 3 ,

- Sirenia Sánchez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1597-679X 2 &

- Sylvia P. Perry ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3435-3125 2 , 4 , 5

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 2 , pages 392–406 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

17 Citations

53 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Social behaviour

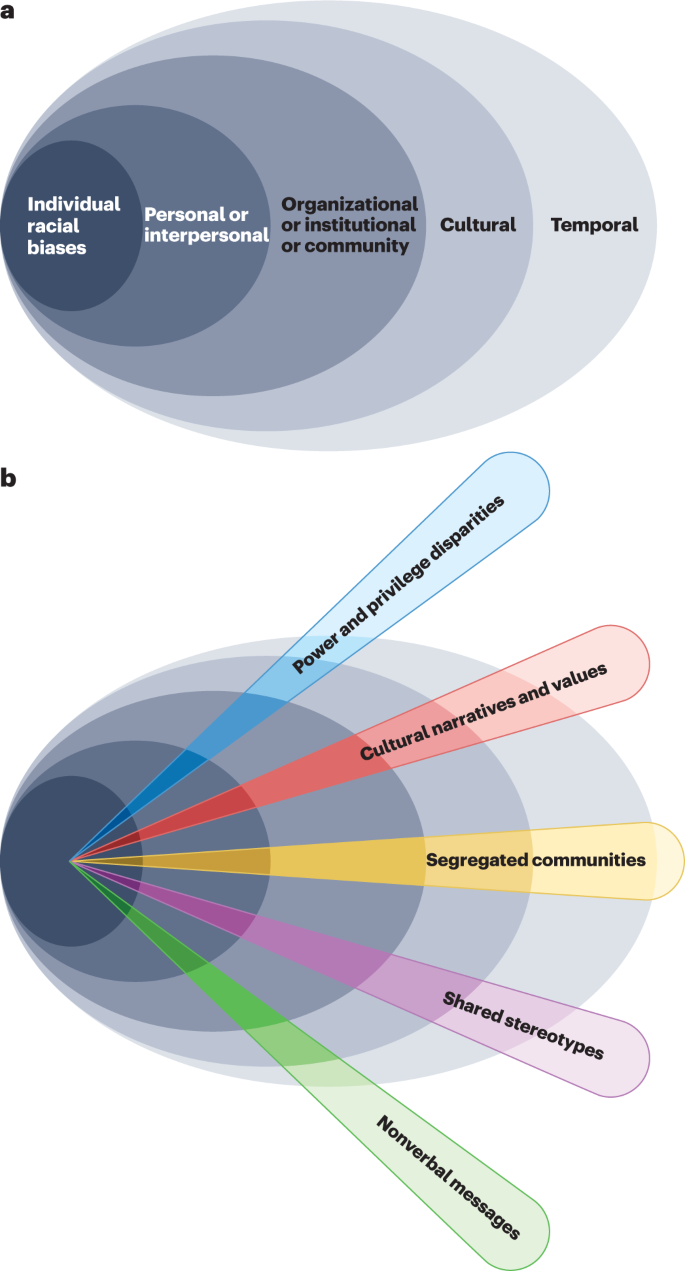

Historically, the field of psychology has focused on racial biases at an individual level, considering the effects of various stimuli on individual racial attitudes and biases. This approach has provided valuable information, but not enough focus has been placed on the systemic nature of racial biases. In this Review, we examine the bidirectional relation between individual-level racial biases and broader societal systems through a systemic lens. We argue that systemic factors operating across levels — from the interpersonal to the cultural — contribute to the production and reinforcement of racial biases in children and adults. We consider the effects of five systemic factors on racial biases in the USA: power and privilege disparities, cultural narratives and values, segregated communities, shared stereotypes and nonverbal messages. We discuss evidence that these factors shape individual-level racial biases, and that individual-level biases shape systems and institutions to reproduce systemic racial biases and inequalities. We conclude with suggestions for interventions that could limit the effects of these influences and discuss future directions for the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cognitive causes of ‘like me’ race and gender biases in human language production

The correct way to test the hypothesis that racial categorization is a byproduct of an evolved alliance-tracking capacity

A psycholinguistic study of intergroup bias and its cultural propagation

Introduction.

The field of psychology so far has primarily focused on racial bias at an individual level, centring the effects of various stimuli on the racial biases of individuals 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 . Racial bias refers to favouring or providing preferential treatment to members of one racial group over another. There is no doubt that the approach of focusing on personally held racial prejudices and discrimination has provided valuable information about the psychology of racial biases. However, this approach largely ignores the systemic nature of racial biases and the ways in which racial biases are shaped by the broader cultural systems in which people live 12 , 13 , 14 . For instance, the focus on individual-level biases has contributed to the burgeoning industry of diversity and implicit bias trainings 15 that aim to address problems such as police brutality against Black people 16 . Although potentially useful for changing individual attitudes and/or biases, these interventions seem unlikely to adequately address the underlying causes of bias, which stem from the systems and structures that create and reinforce racial inequality.

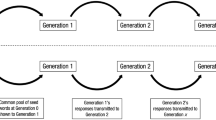

The overemphasis on the individual level in research on racial biases seems to have come at the expense of psychological research and theorizing about the impact of broader contextual factors, and how individual-level racial biases reinforce broader systemic patterns of oppression. Models of nested levels of influence in the study of race relations 17 , human development 18 and culture 19 , 20 can be used to consider the relation between racial bias and broader systemic factors (Fig. 1 ). Each level of influence influences the innermost level of individual attitudes, and conversely, individual-level attitudes also influence systems 21 .

a , The nested-levels framework focuses on how each systemic level of influence influences individual-level attitudes, and how individual-level attitudes influence systems. The most proximal influences on racial bias are personal and interpersonal experiences, which are nested within communities and institutions that set the local context for interpersonal experiences. Communities are situated within broader cultural contexts that shape the norms, values and beliefs that structure society. At the outermost level are temporal influences, which capture how past manifestations of these systems continue to influence members of society. b , There is a bidirectional influence from each of the systemic levels to the individual level and from the individual level back out to each of the systemic levels, within the five factors discussed in the Review.

Five key systemic factors — power and privilege disparities, cultural narratives and values, segregated communities, shared stereotypes, and nonverbal messages — influence racial bias across the nested levels of this framework. Although they are certainly not the only systemic factors that influence racial biases, we focus on these five because we believe them to be particularly relevant to the development of racial biases in the contemporary USA. At the innermost level are the most proximal influences on individual-level racial bias — personal and interpersonal experiences, such as socialization from caregivers and interracial friendships. These experiences are nested within communities and institutions that set the local context for interpersonal experiences, such as the racial diversity in a school or neighbourhood community. Communities are situated within a broader cultural context that shapes the norms, values, and beliefs that structure society. At the outermost level are temporal influences, which capture how past interpersonal, institutional or community, and societal influences continue to influence members of society throughout their lives. Although the primary focus is on how each level of influence affects individual-level attitudes, the levels also influence one another. For instance, culture can shape organizations and interpersonal experiences within that culture, as well as individual-level biases. Likewise, individual-level racial biases can mould interpersonal experiences, which can shape factors at the organizational and community level.

In this Review, we recognize the bidirectional relation between individual-level racial biases and broader societal systems across levels of influence. In some cases, there is clear evidence of the causal chain from system to individual and from individual to system, whereas in others, there might be evidence of an association, but the direction of influence is unclear. In many cases, individual-level biases and broader societal systems might be mutually reinforcing, but for clarity we take the approach of assessing each direction of influence separately. We examine the role of power and privilege, cultural narratives and values, racial segregation, shared cultural stereotypes and nonverbal signals in racial bias. In each section, we first discuss what is known about the contextual factors that produce and reinforce individual-level biases before highlighting how individual-level biases shape institutions and systems. Although our primary focus is on how these systemic factors influence racial biases, we also use the nested levels of influence framework to examine how individual-level racial biases held by the public can contribute to the reinforcement and perpetuation of systemic oppression at the interpersonal, institutional and/or community, societal and temporal levels. We conclude with implications for interventions aimed at reducing racial bias and discuss future directions for research.

To appropriately analyse the factors that perpetuate racial bias at a systemic level, it is critical to contextualize within culture. We focus on the USA because it is the context that we have the cultural knowledge to discuss and where most research on racial bias development has been conducted. The racial context of the USA is distinct in several ways. Notably, white European colonizers violently stole the land that comprises the USA from indigenous inhabitants across multiple centuries 22 . Furthermore, the enslavement of Black people was legal and common practice for over 200 years in North America 23 , 24 . Citizenship was largely restricted to white people for most of the history of the USA, with full citizenship not open to people of all ethnicities until 1952 (ref. 25 ). Throughout this history, white people have accrued power, wealth, status and numerical majority status through systems that intentionally oppress and marginalize people of colour, including Native Americans, African Americans and members of other ethnic groups. Although modern laws bar racial discrimination, substantial racial inequalities between white people and people of colour persist in the USA, in areas including wealth, education and health 26 , 27 , 28 . Given this history of racism in the USA, the systemic factors that perpetuate racial biases into the present might be somewhat distinct from other contexts. Despite this focus on the USA, this Review could be valuable for understanding similar patterns of bias and oppression outside the USA. Some of these similarities are highlighted in the book Caste: The Origins Of Our Discontents 29 — which draws parallels between the systems of oppression of Black people in the USA, Jewish people in Nazi Germany and Dalit people in India. Although thoroughly analysing such parallels is beyond the scope of this Review, we briefly discuss systemic factors that perpetuate biases based on socially constructed categories — such as race — in other cultural contexts in the concluding section.

Power and privilege disparities

Power and privilege disparities set the initial conditions within which other factors operate. Systemic inequalities in the distribution of power and privilege serve as the societal backdrop in the USA, directly contributing to individual-level racial biases. Many residents of the USA grow up in an environment in which their doctors, lawyers, teachers, government officials, entrepreneurs, and people occupying other respected roles are white 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 . Thus, to these residents, the USA might look like it ‘belongs to’ white people.

Children who are socialized in an unequal society, without systemic explanations for why power and privilege have been concentrated among certain people, often internalize that system 34 . Both children and adults tend to conclude that the way things are structured in society is the way they should be 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 . For example, experimental evidence suggests that children in the USA tend to prefer people who are relatively more fortunate, even if that good fortune is simply due to luck 43 , and when given the opportunity to rectify existing resource inequalities, they often exacerbate inequalities by giving more to the person who already has more resources 44 . These laboratory findings suggest that when children are socialized in an environment in which people in a particular social group have more resources, they will tend to favour people in that social group and distribute resources in ways that perpetuate resource disparities. Thus, in the USA — where racial wealth disparities are large and growing 28 — systemic inequalities predispose children to infer that white people are better than and deserve to have more than people of colour 45 . Among adults, markers of structural racial inequalities can also predict racial bias. Attending a university with few faculty members of colour, living in an area that has high poverty rates among Black residents and living in a community with low economic mobility all predict heightened implicit bias against Black people among non-Black American residents 7 , 46 . In other words, children and adults are motivated to justify the systems in which they are socialized 41 , 42 .

When progressive changes in society challenge ingrained expectations of inequality, racial biases can be heightened. White residents of the USA who were exposed to information about the increasing racial diversity of the USA subsequently exhibited increased bias favouring white people relative to those who were not exposed to this information 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 . Emphasizing the racially historic milestone of Barack Obama being elected as president of the USA also increased implicit pro-white bias among white American residents, relative to those who were not exposed to this information 50 . This research suggests that racial inequalities at various levels of influence — from local communities to the broader cultural context — can lead people to believe that inequality is natural and justified, and that racial progress that challenges those inequalities might further intensify individual-level racial bias.

Next, we turn to the role of individual-level racial biases in perpetuating systemic racial inequalities. Individual-level racial biases have been argued to impact systemic disparities in power and privilege in a variety of domains, including government representation, population health, education, employment, and immigration 51 . Perhaps the most direct impact of individual-level racial biases on systemic outcomes can be seen in voting behaviour. Greater individual-level anti-Black bias was associated with a lower likelihood of voting for Barack Obama in the 2008 American presidential election and reduced support for his healthcare reform proposal 52 , 53 . With regard to health, white residents of the USA (especially those with higher racial bias) were less supportive of COVID-19 pandemic precautions when they were more aware — based on prior knowledge or experimental exposure to information — that COVID-19 was disproportionately affecting people of colour in the USA 54 , 55 , 56 . Other work has tied racial disparities in health and healthcare access to the average individual-level bias against Black people held by white residents in their county of residence 53 , 57 . In locations where white residents had higher racial biases, Medicaid disability expenditures (which particularly benefit people of colour) were lower, and Black residents had reduced access to healthcare and increased rates of circulatory-disease-related death 53 , 57 . Educational disparities have also been linked to individual-level racial biases. In American counties where the individual-level bias against Black people is stronger, there are larger racial disparities in school disciplinary actions, with Black students being subjected to more suspensions, expulsions, and referrals to law enforcement than white students 58 . These findings suggest that individual-level biases of residents of the USA can influence presidential elections, community health inequalities and school disciplinary actions, reflecting long-term temporal impacts on the privilege and power afforded to people of colour at cultural, community, and interpersonal levels.

In sum, racial disparities in power and privilege have been built into the societal system of the USA, resulting in wide-ranging effects on the life outcomes of residents of the USA. This system also affects the attitudes of those living within the system, leading to expectations of inequality and beliefs that inequality is justified. These beliefs and expectations then motivate the individuals that make up the system to behave in ways that maintain the system of inequality, such that individuals’ attitudes reinforce the system of inequality that produced them.

Cultural narratives and values

The concentration of power and privilege among white people in the USA means that white people largely write the histories, set the norms and define the values of American society. This centring of white people can be seen in historical narratives, cultural products and cultural beliefs, which can all contribute to the development of individual-level racial biases 59 . Below, we discuss the role of each of these aspects of culture in shaping racial biases.

Historical narratives

Historical narratives can play an important part in how people view themselves and others in society 10 . In educational curricula in the USA, national history tends to be taught through a white-affirming lens, such that the attitudes, values and perspectives of white people are implicitly or explicitly justified by the historical narrative 60 , 61 . The perspectives and experiences of people of colour are often omitted from curricula entirely. For instance, despite their many historical contributions to the USA 62 , Asian Americans are vastly underrepresented in American textbooks 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 .

For much of the history of the USA, when people of colour were discussed in textbooks, they were described with derogatory and dehumanizing stereotypes that justified their marginalization 60 , 67 . Moreover, egregious acts perpetrated by white people have often been presented in a sanitized way that minimizes, glosses over, and justifies them 68 , 69 , 70 . As an example, ‘manifest destiny’ (the worldview that white people were destined to expand their territory to the west coast of North America) is often presented uncritically as a justification for atrocities that white people committed against the original Native American and Mexican inhabitants of the continent 60 , 71 . Similarly, Confederate symbols — which celebrate the southern American states that went to war with northern American states to maintain the institution of slavery — are argued to be a race-neutral representation of Southern pride in some textbooks and by some modern pundits and continue to be displayed at some courthouses 72 , 73 , 74 . The way history is usually portrayed in American society therefore obscures the relation between contemporary systems and racial injustices of the past 61 . Some states have even created laws explicitly barring the teaching of critical history related to race 75 .

The way history is presented in society shapes individual-level attitudes about race and racism. School curricula can be vital contributors to ethnocentric biases in childhood 76 . Furthermore, adults who have less knowledge of the racial injustices of the past tend to be less aware of present-day racism 77 . Exposure to historical narratives that centre white people and glorify the nation reduce awareness of racial injustices among school children, college students, and adult museum visitors 70 , 78 . Furthermore, experimental evidence suggests that exposure to the Confederate flag (versus no exposure to the flag) can increase racial biases and promote racial injustice 79 . Thus, how history is portrayed at a cultural level, in textbooks, and in community schools and institutions (such as museums and memorials) has the potential to influence individual-level racial biases.

Individuals receive and simultaneously reproduce and uphold these historical narratives. For instance, it was argued in 1963 that the individual-level racial biases of historians were to blame for the history of Native Americans being oversimplified, mischaracterized and/or overlooked entirely 80 . Although there have been changes to the framing of the history of the USA over the intervening 60 years, many of the issues identified persist to this day 81 . For example, Christopher Columbus is still often credited with and praised for ‘discovering’ North America, even though it was already inhabited by thriving interconnected societies of millions of people 22 .

The effects of individual-level biases can also be seen at the community and interpersonal levels. The same history and culture can be represented differently depending on who is curating and constructing the representation 78 , 82 . As an example, students who reported that being white was central to their identity reported more negative attitudes towards Black History Month representations that were curated and displayed in schools in which the majority of students were Black (versus those that were curated and displayed in schools in which the majority of students were white) 70 . This finding is particularly meaningful because Black History Month representations in schools with a majority of Black students were generally more supportive of anti-racism than those in schools with a majority of white students. Another study provided evidence that patrons of the Ellis Island Immigration Museum tended to identify exhibits that painted the USA in a positive light as more important than exhibits highlighting historical injustices 78 . Patrons who reported more assimilationist attitudes — such as believing that to ‘be truly American’ means speaking English — particularly disliked the exhibits highlighting historical injustices. All of these findings converge to suggest that individual-level biases shape the way people in the USA think about and portray history at personal, community, cultural and temporal levels.

Cultural products

At a societal level, the cultural products — such as art forms, varieties of dress and appearance, and styles of speech — of white people tend to be the most highly regarded. The art, music, and dance that are most culturally valued in the USA are rooted in white European traditions 83 , 84 . For instance, professional dance schools largely focus on ballet and modern dance 85 and music departments primarily emphasize classical music education — marginalizing the study of dance and music traditions developed by artists of colour 86 , 87 . Expectations for appropriate dress and communication are also centred around norms established by white Americans. In some cases, schools 88 and workplaces 89 have created policies and municipalities have passed laws 90 prohibiting styles of dress that are culturally linked to people of colour, such as durags, hijabs, and sagging pants. Even when these marginalized styles are not explicitly banned, there might be added scrutiny of individuals who wear them 91 . As an example, Black women are often expected to conform to white femininity norms by straightening their hair to be perceived as professional 90 , 92 , 93 . Furthermore, grammatical rules and standard linguistic styles in the USA are based on the language practices of white Americans 94 and deviations from these norms — such as use of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) — are often cited as evidence of inferiority 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 . Although there can be conditional acceptance and appropriation of elements of the cultures of people of colour such as styles of dress 99 , the typical situation is the prioritization of cultural products of white people.

In summary, the cultural products of people of colour are devalued and stigmatized at a societal level, which results in individual-level biases against those who use and produce these cultural products. This contribution to individual-level racial bias is particularly insidious because it creates conditions under which people can obliviously perpetuate racial biases, believing their bias to be against the cultural products they perceive as inferior rather than the people associated with the products. In one hypothetical scenario at an interpersonal level, parents might pass along individual-level racial biases to their children when parents conclude that the classmate with dreadlocked hair (a hairstyle with African roots that is common among Black Americans) looks like a troublemaker. In this way, Americans can look down on Black people who engage with Black cultural products — like listening to hip hop music, having dreadlocks or using AAVE — while still believing themselves to be ‘not racist’. Devaluing Black cultural products perpetuates racism, because doing so suggests that Black culture is inferior to white culture.

Individual-level biases can also feed back to contribute to the reproduction of biased cultural products. White people are more likely than people of other races to rise to positions of economic power and influence 100 , and therefore to enact their individual biases and serve as gatekeepers for the promotion of certain cultural products over others. At the most extreme, individual-level biases of white people in power have resulted in cultural genocide, such as through Native American boarding schools, which systematically destroyed Native American families and communities 101 . The white people who created and promoted Native American boarding schools argued that Native American communities were dangerous and that Native children needed to be rescued by ‘good Christians’ 102 . These arguments were consistent with widespread beliefs about the cultural inferiority of Native Americans, which allowed racist policies, such as those forcing all Native American children to live in boarding schools that barred them from practising their culture, seem acceptable.

Evidence of the effects of widely held individual-level white-centric biases can also be observed on a cultural level in academic fields, influencing their methods, standards, and knowledge bases (for example, in mathematics 103 , 104 , psychology 105 , and written composition 87 , 94 ). As an example, individual-level biases towards white cultural products arguably led to the development of writing standards that privilege white styles of discourse 106 . From a historical perspective, although Native Americans had a diverse array of numeric systems that were still in use at the turn of the twentieth century 107 , individual-level biases towards white people and culture led ‘Western mathematics’ to be established as the standard for mathematics education in the USA, marginalizing indigenous knowledge 103 . The effect of individual-level biases among key decision-makers can also be seen in policy decisions, such as whose cultural holidays are officially recognized as public holidays 108 and whose cultural knowledge frames the questions used in standardized testing 109 , 110 , 111 .

Cultural beliefs

Widely held cultural beliefs and philosophies can shape the way in which individuals make sense of society, contributing to individual-level racial biases. In the USA, the ‘American dream’ — which asserts that anyone can achieve success if they are willing to put in the work — is a dominant philosophy in government, education and the media. The belief that people who merit success will ultimately achieve it can serve as a beacon of hope for those who are striving to raise their social status, while also justifying to people with the highest status that they have rightfully earned their positions. Thus, promoting the American dream reinforces tendencies for people to justify and reinforce the systems of inequality in which they were socialized 41 , 42 , 112 , 113 . Indeed, priming American residents with messages promoting meritocracy (versus other types of messages) can reduce recognition of unearned privilege 114 and increase blame placed on people disadvantaged by societal systems 115 . Given the many racial inequalities in American society, teaching children that people who deserve success achieve it conveys the implicit message that most people of colour do not merit the status and success that white people enjoy in the USA 45 — imparting individual-level racial bias.

Racially colourblind ideology (the idea of disregarding the issue of race) is another cultural philosophy that can contribute to the perpetuation of individual-level racial biases. Polling data from 2020 indicated that approximately 40% of American residents believed that paying less attention to race would improve racial inequalities in society 116 . Yet, evidence suggests that racially colourblind messages provide a way for racially biased messages to discreetly influence public attitudes. For example, white Americans are much more likely to be persuaded to adopt policy positions through subtle racial appeals referring to Black people — such as references to the ‘inner city’ or ‘culture of poverty’ — than they are to be persuaded by explicit racial appeals that refer to Black people as lazy and uneducated welfare recipients 117 , 118 . Politicians have deliberately used these ‘dog whistles’ to capitalize on racial stereotypes and gain public support for racist political agendas 119 , 120 . Even ostensibly well intentioned colourblind attitudes and policies can perpetuate racial biases 121 . For instance, exposing children to the racially colourblind mindset, compared to a diversity mindset, reduced their ability to identify racially biased incidents and appropriately report them to teachers 122 . Promoting racial colourblindness at a societal, institutional or even an interpersonal level can reduce individual-level awareness of systemic racism and increase susceptibility to racially biased messages.

In the reverse direction, individual-level racial biases can also influence cultural beliefs. Americans with higher levels of racial bias tend to report a stronger belief in meritocracy 123 , 124 . Moreover, young, white adults with relatively high socio-economic status are more likely than people of other races and lower economic status to believe that the USA is a meritocracy 125 . Individual-level racial biases are also associated with more support for racially colourblind sentiments, such as ‘society would be better off if we all stopped talking about race’ 126 , 127 . Some psychologists have theorized that racial biases can motivate racially colourblind perspectives that help to maintain ignorance of racial injustices 128 . Racially colourblind ideology has also served to perpetuate systemic racism through government policies (Box 1 ). Taken together, individual-level racial biases have been associated with cultural philosophies that obscure and reinforce racial inequalities across societal levels.

Altogether, historical narratives that exclude people of colour and downplay the history of racism in the USA, cultural norms that devalue the cultural products of people of colour, and cultural beliefs that obscure systems of inequality contribute to the development and maintenance of individual-level racial biases. Once individual-level racial biases have been established, these attitudes cumulatively shape how history is told, what cultural knowledge and products make up the mainstream, and what cultural beliefs are promoted.

Box 1 Colourblind ideology

In the USA, there are numerous examples of societal-level colourblind racial ideology being used to uphold systemic racial oppression. For instance, following the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling (1954), separate schools for Black and white students were ruled unconstitutional. Consequently, school boards in multiple American states continued to segregate students by race but claimed that school assignments were now based on ‘fit’ and ‘ability’, rather than race 264 . In this example, the colourblind ideology of assignment by ability was a means of perpetuating systemic oppression while also obscuring systemic racism and reinforcing racist stereotypes about intellectual abilities. A similar series of events took place following the Batson v. Kentucky (1986) Supreme Court decision, which ruled that potential jurors could not be removed on the basis of their race. Following the decision, attorneys continued to remove Black potential jurors, but now provided a colourblind rationale 265 , 266 . Jurors can be struck for such arbitrary reasons as wearing a hat, being unemployed, or the prosecutor simply having a bad feeling about them 266 .

Perhaps the greatest effect of the use of colourblind ideology emerged as part of the so-called War on Drugs, a federal campaign in the USA that began in 1971 to crack down on the possession and sale of illegal drugs. One of its most notorious policies set a penalty 100 times higher for possession of substances that were disproportionately used by Black American residents than for substances disproportionately used by white American residents 210 . The War on Drugs has been credited with the massive increase in the prison population and dramatic growth of racial disparities in incarceration rates in the USA during the late twentieth century 267 . As of 2021, Black Americans were incarcerated at roughly five times the rate of white Americans 268 , 269 . Overall, racially colourblind ideology has allowed systemic policies that are ostensibly race-neutral to remain racially biased in effect.

Segregated communities

Segregation in neighbourhoods, workplaces, and classrooms is another systemic influence on individual-level racial bias. Segregation in the USA is often a result of the power and privilege disparities and cultural narratives discussed above. For instance, ‘redlining’ was a mid-twentieth-century policy in which neighbourhoods were graded (from ‘desirable’ to ‘hazardous’) according to their supposed risk of decreasing in value. Neighbourhoods populated by people of colour were assigned the lowest scores (demarcated by a red border on a map), which both reduced the value of these homes and prevented homebuyers from accessing federally backed and insured loans 129 , 130 . The enduring impact of this policy is that families of colour have not been able to build the generational wealth through homeownership that white people have 28 , 131 . To this day, homeowners in neighbourhoods that were deemed hazardous have dramatically less home equity than homeowners in areas that were deemed desirable 132 . Thus, residents of the USA see that nice homes and other symbols of wealth are associated with white people, promoting and reinforcing individual-level pro-white biases 130 .

The echoes of this policy also reinforce residential segregation because homebuyers with adequate means (who are more likely to be white) are motivated to avoid redlined neighbourhoods, where homes tend to be devalued and appreciate far less over time 132 . Thus, racial segregation remains commonplace in the USA. For instance, the average white American lives in a neighbourhood whose residents are 75% white 133 . Similarly, workplace racial segregation was higher in the 2010s than it was in the 1980s and 1990s 134 . Although public school segregation was ruled unconstitutional in 1954 (ref. 135 ), the last school district only fully integrated in 2017 (ref. 136 ). Even within racially integrated schools, a biased system of sorting students into different and unequal course tracks results in overrepresentation of white students in the more advanced and better resourced tracks 137 .

Ongoing segregation also limits intergroup contact 138 — contact between people belonging to different racial or ethnic groups — one of the most reliable and best studied predictors of reduced individual-level bias 139 . Close contact between groups has been argued to reduce prejudice when those groups share common goals, hold equal status, cooperate with each other and are supported by the broader societal system 138 . Systemic racism in the USA reduces the likelihood of these conditions being met, but the bulk of the evidence indicates that even when optimal conditions are not met, positive intergroup contact reduces prejudice 140 , 141 , 142 . Thus, the fact that so many social environments — including communities, institutions and interpersonal experiences — in the USA remain racially segregated probably contributes to the persistence of individual-level racial biases.

Limited opportunities for close contact might be particularly detrimental when groups share the same geographic space but lack close contact with one another. A 2015 study found that racial biases among white residents of the USA were highest in states where the Black population was largest 143 . A follow-up study examined how this pattern relates to intergroup contact, finding that living in a state with more Black residents was only associated with increased racial bias among white residents who had limited close contact with Black people 144 . Thus, when white people live alongside people of colour in their communities without forming close relationships, racial bias might increase. As such, racial segregation in racially diverse regions and states seems particularly likely to engender individual-level racial biases because intergroup exposure can elicit group threat 145 , without the psychological benefits provided by meaningful emotional connections developed through close intergroup contact.

Individual-level racial biases can also reinforce segregated communities and systems. Black communities in the USA are stereotyped as being impoverished, crime-ridden, rundown, dangerous, dirty, and ‘ghetto’ 146 , 147 . If key decision-makers or a critical mass of members of the public hold these biases, devaluation of physical spaces associated with people of colour (such as schools and neighbourhoods) can result 148 , 149 , 150 , 151 . There is experimental evidence that homes in predominantly Black neighbourhoods and homes owned by Black (versus white) people tend to be devalued. When white residents of the USA were asked to assign value to a home, they thought the home was worth less if an image of a Black (relative to white) family appeared in front of the home, even though all other factors were the same 146 . The same patterns emerge in actual housing data 152 . Schools in predominantly Black neighbourhoods are undervalued, receiving less funding per student than schools in predominantly white neighbourhoods 153 .

This disregard for neighbourhoods populated by people of colour can also be seen in decisions about infrastructure, such as where to place hazardous waste dumps and what communities to displace when new amenities such as freeways and railroads are introduced into communities. Eminent domain — a legal power that forces private citizens to sell land to the government for public projects —is more likely to be used in communities of colour 154 , 155 and has myriad negative consequences, including loss of wealth and disruption of community ties and stability 156 , 157 . Experimental evidence has indicated that white Americans are less likely to oppose placing a hypothetical chemical plant next to a Black neighbourhood than next to a white neighbourhood 146 . Real-world data are consistent with this hypothetical scenario: the highest polluting industries and sites for toxic waste disposal in the USA tend to be in areas with large populations of Black people 158 , 159 . By contrast, experimental evidence indicates that landmarks that are of interest to white people (such as their workplaces, schools, pools, golf clubs and tennis clubs) tend to be placed relatively far from communities of colour 160 . Furthermore, analyses of existing institutional policies show that recreation facilities that are closer to communities of colour have more exclusionary barriers — such as fees or dress codes 160 , 161 . The history of practices of this kind explain the relatively low swimming rates among Black Americans and dramatically higher drowning rates among Black (relative to white) American residents 162 , 163 , 164 .

Overall, individual-level racial biases can contribute to the devaluation and negative stereotyping of physical spaces occupied by people of colour, which make those spaces less desirable to white people—reinforcing racial segregation. These racial biases might ultimately contribute to a host of systemic and structural racial inequalities within domains ranging from health and wealth to education, which adversely impact people of colour for generations.

Shared stereotypes

Shared stereotypes can spread cultural narratives and justify oppressive systems. Propaganda campaigns have been used to spread stereotypes about people of colour throughout the history of the USA. For instance, nineteenth-century media stereotypes of men of Chinese descent as weak and effeminate 165 , 166 were used to marginalize these men, painting them as poorly suited for traditionally masculine jobs and undesirable as husbands 167 . Propaganda about intellect, criminality, and sexuality has been used by the media, politicians, industries, and scientists to exercise social control over Black Americans and justify their enslavement and subordination for centuries 23 , 168 , 169 (and see a preprint 170 ).

Stereotypical representations of people of colour continue in the contemporary media 34 . On television, people of colour tend to be depicted in negative and stereotypical ways 171 , 172 , 173 , as outside mainstream contemporary society 174 or not represented at all 175 . News coverage also tends to depict people of colour in a negative light 176 , 177 , 178 and Black criminal suspects are often overrepresented in news media — perpetuating stereotypes that Black people are ‘criminal’ and ‘reckless’ 179 , 180 . These stereotypes represent only a few of the many ways people of colour are negatively stereotyped in the USA. Meanwhile, white people are overrepresented in media coverage of crime victims 174 , 181 , 182 .