| | | | |||||

|

| |||||

The drama of the mid-twentieth century emerged on a foundation of earlier struggles. Two are particularly notable: the NAACP’s campaign against lynching, and the NAACP’s legal campaign against segregated education, which culminated in the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown decision.

The NAACP’s anti-lynching campaign of the 1930s combined widespread publicity about the causes and costs of lynching, a successful drive to defeat Supreme Court nominee John J. Parker for his white supremacist and anti-union views and then defeat senators who voted for confirmation, and a skillful effort to lobby Congress and the Roosevelt administration to pass a federal anti-lynching law. Southern senators filibustered, but they could not prevent the formation of a national consensus against lynching; by 1938 the number of lynchings declined steeply. Other organizations, such as the left-wing National Negro Congress, fought lynching, too, but the NAACP emerged from the campaign as the most influential civil rights organization in national politics and maintained that position through the mid-1950s.

Houston was unabashed: lawyers were either social engineers or they were parasites. He desired equal access to education, but he also was concerned with the type of society blacks were trying to integrate. He was among those who surveyed American society and saw racial inequality and the ruling powers that promoted racism to divide black workers from white workers. Because he believed that racial violence in Depression-era America was so pervasive as to make mass direct action untenable, he emphasized the redress of grievances through the courts.

The designers of the Brown strategy developed a potent combination of gradualism in legal matters and advocacy of far-reaching change in other political arenas. Through the 1930s and much of the 1940s, the NAACP initiated suits that dismantled aspects of the edifice of segregated education, each building on the precedent of the previous one. Not until the late 1940s did the NAACP believe it politically feasible to challenge directly the constitutionality of “separate but equal” education itself. Concurrently, civil rights organizations backed efforts to radically alter the balance of power between employers and workers in the United States. They paid special attention to forming an alliance with organized labor, whose history of racial exclusion angered blacks. In the 1930s, the National Negro Congress brought blacks into the newly formed United Steel Workers, and the union paid attention to the particular demands of African Americans. The NAACP assisted the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the largest black labor organization of its day. In the 1940s, the United Auto Workers, with NAACP encouragement, made overtures to black workers. The NAACP’s successful fight against the Democratic white primary in the South was more than a bid for inclusion; it was a stiff challenge to what was in fact a regional one-party dictatorship. Recognizing the interdependence of domestic and foreign affairs, the NAACP’s program in the 1920s and 1930s promoted solidarity with Haitians who were trying to end the American military occupation and with colonized blacks elsewhere in the Caribbean and in Africa. African Americans’ support for WWII and the battle against the Master Race ideology abroad was matched by equal determination to eradicate it in America, too. In the post-war years blacks supported the decolonization of Africa and Asia.

The Cold War and McCarthyism put a hold on such expansive conceptions of civil/human rights. Critics of our domestic and foreign policies who exceeded narrowly defined boundaries were labeled un-American and thus sequestered from Americans’ consciousness. In a supreme irony, the Supreme Court rendered the Brown decision and then the government suppressed the very critique of American society that animated many of Brown ’s architects.

White southern resistance to Brown was formidable and the slow pace of change stimulated impatience especially among younger African Americans as the 1960s began. They concluded that they could not wait for change—they had to make it. And the Montgomery Bus Boycott , which lasted the entire year of 1956, had demonstrated that mass direct action could indeed work. The four college students from Greensboro who sat at the Woolworth lunch counter set off a decade of activity and organizing that would kill Jim Crow.

Elimination of segregation in public accommodations and the removal of “Whites Only” and “Colored Only” signs was no mean feat. Yet from the very first sit-in, Ella Baker , the grassroots leader whose activism dated from the 1930s and who was advisor to the students who founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), pointed out that the struggle was “concerned with something much bigger than a hamburger or even a giant-sized Coke.” Far more was at stake for these activists than changing the hearts of whites. When the sit-ins swept Atlanta in 1960, protesters’ demands included jobs, health care, reform of the police and criminal justice system, education, and the vote. (See: “An Appeal for Human Rights.” ) Demonstrations in Birmingham in 1963 under the leadership of Fred Shuttlesworth’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, which was affiliated with the SCLC, demanded not only an end to segregation in downtown stores but also jobs for African Americans in those businesses and municipal government. The 1963 March on Washington, most often remembered as the event at which Dr. King proclaimed his dream, was a demonstration for “Jobs and Justice.”

Movement activists from SNCC and CORE asked sharp questions about the exclusive nature of American democracy and advocated solutions to the disfranchisement and violation of the human rights of African Americans, including Dr. King’s nonviolent populism, Robert Williams’ “armed self-reliance,” and Malcolm X’s incisive critiques of worldwide white supremacy, among others. (See: Dr. King, “Where Do We Go from Here?” ; Robert F. Williams, “Negroes with Guns” ; and Malcolm X, “Not just an American problem, but a world problem.” ) What they proposed was breathtakingly radical, especially in light of today’s political discourse and the simplistic ways it prefers to remember the freedom struggle. King called for a guaranteed annual income, redistribution of the national wealth to meet human needs, and an end to a war to colonize the Vietnamese. Malcolm X proposed to internationalize the black American freedom struggle and to link it with liberation movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Thus the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s was not concerned exclusively with interracial cooperation or segregation and discrimination as a character issue. Rather, as in earlier decades, the prize was a redefinition of American society and a redistribution of social and economic power.

Guiding Student Discussion

Students discussing the Civil Rights Movement will often direct their attention to individuals’ motives. For example, they will question whether President Kennedy sincerely believed in racial equality when he supported civil rights or only did so out of political expediency. Or they may ask how whites could be so cruel as to attack peaceful and dignified demonstrators. They may also express awe at Martin Luther King’s forbearance and calls for integration while showing discomfort with Black Power’s separatism and proclamations of self-defense. But a focus on the character and moral fiber of leading individuals overlooks the movement’s attempts to change the ways in which political, social, and economic power are exercised. Leading productive discussions that consider broader issues will likely have to involve debunking some conventional wisdom about the Civil Rights Movement. Guiding students to discuss the extent to which nonviolence and racial integration were considered within the movement to be hallowed goals can lead them to greater insights.

Nonviolence and passive resistance were prominent tactics of protesters and organizations. (See: SNCC Statement of Purpose and Jo Ann Gibson Robinson’s memoir, The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It. ) But they were not the only ones, and the number of protesters who were ideologically committed to them was relatively small. Although the name of one of the important civil rights organizations was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, its members soon concluded that advocating nonviolence as a principle was irrelevant to most African Americans they were trying to reach. Movement participants in Mississippi, for example, did not decide beforehand to engage in violence, but self-defense was simply considered common sense. If some SNCC members in Mississippi were convinced pacifists in the face of escalating violence, they nevertheless enjoyed the protection of local people who shared their goals but were not yet ready to beat their swords into ploughshares.

Armed self-defense had been an essential component of the black freedom struggle, and it was not confined to the fringe. Returning soldiers fought back against white mobs during the Red Summer of 1919. In 1946, World War Two veterans likewise protected black communities in places like Columbia, Tennessee, the site of a bloody race riot. Their self-defense undoubtedly brought national attention to the oppressive conditions of African Americans; the NAACP’s nationwide campaign prompted President Truman to appoint a civil rights commission that produced To Secure These Rights , a landmark report that called for the elimination of segregation. Army veteran Robert F. Williams, who was a proponent of what he called “armed self-reliance,” headed a thriving branch of the NAACP in Monroe, North Carolina, in the early 1950s. The poet Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die” dramatically captures the spirit of self-defense and violence.

Often, deciding whether violence is “good” or “bad,” necessary or ill-conceived depends on one’s perspective and which point of view runs through history books. Students should be encouraged to consider why activists may have considered violence a necessary part of their work and what role it played in their overall programs. Are violence and nonviolence necessarily antithetical, or can they be complementary? For example the Black Panther Party may be best remembered by images of members clad in leather and carrying rifles, but they also challenged widespread police brutality, advocated reform of the criminal justice system, and established community survival programs, including medical clinics, schools, and their signature breakfast program. One question that can lead to an extended discussion is to ask students what the difference is between people who rioted in the 1960s and advocated violence and the participants in the Boston Tea Party at the outset of the American Revolution. Both groups wanted out from oppression, both saw that violence could be efficacious, and both were excoriated by the rulers of their day. Teachers and students can then explore reasons why those Boston hooligans are celebrated in American history and whether the same standards should be applied to those who used arms in the 1960s.

An important goal of the Civil Rights Movement was the elimination of segregation. But if students, who are now a generation or more removed from Jim Crow, are asked to define segregation, they are likely to point out examples of individual racial separation such as blacks and whites eating at different cafeteria tables and the existence of black and white houses of worship. Like most of our political leaders and public opinion, they place King’s injunction to judge people by the content of their character and not the color of their skin exclusively in the context of personal relationships and interactions. Yet segregation was a social, political, and economic system that placed African Americans in an inferior position, disfranchised them, and was enforced by custom, law, and official and vigilante violence.

The discussion of segregation should be expanded beyond expressions of personal preferences. One way to do this is to distinguish between black and white students hanging out in different parts of a school and a law mandating racially separate schools, or between black and white students eating separately and a laws or customs excluding African Americans from restaurants and other public facilities. Put another way, the civil rights movement was not fought merely to ensure that students of different backgrounds could become acquainted with each other. The goal of an integrated and multicultural America is not achieved simply by proximity. Schools, the economy, and other social institutions needed to be reformed to meet the needs for all. This was the larger and widely understood meaning of the goal of ending Jim Crow, and it is argued forcefully by James Farmer in “Integration or Desegregation.”

A guided discussion should point out that many of the approaches to ending segregation did not embrace integration or assimilation, and students should become aware of the appeal of separatism. W. E. B. Du Bois believed in what is today called multiculturalism. But by the mid-1930s he concluded that the Great Depression, virulent racism, and the unreliability of white progressive reformers who had previously expressed sympathy for civil rights rendered an integrated America a distant dream. In an important article, “Does the Negro Need Separate Schools?” Du Bois argued for the strengthening of black pride and the fortification of separate black schools and other important institutions. Black communities across the country were in severe distress; it was counterproductive, he argued, to sacrifice black schoolchildren at the altar of integration and to get them into previously all-white schools, where they would be shunned and worse. It was far better to invest in strengthening black-controlled education to meet black communities’ needs. If, in the future, integration became a possibility, African Americans would be positioned to enter that new arrangement on equal terms. Du Bois’ argument found echoes in the 1960s writing of Stokely Carmichael ( “Toward Black Liberation” ) and Malcolm X ( “The Ballot or the Bullet” ).

Scholars Debate

Any brief discussion of historical literature on the Civil Rights Movement is bound to be incomplete. The books offered—a biography, a study of the black freedom struggle in Memphis, a brief study of the Brown decision, and a debate over the unfolding of the movement—were selected for their accessibility variety, and usefulness to teaching, as well as the soundness of their scholarship.

Walter White: Mr. NAACP , by Kenneth Robert Janken, is a biography of one of the most well known civil rights figure of the first half of the twentieth century. White made a name for himself as the NAACP’s risk-taking investigator of lynchings, riots, and other racial violence in the years after World War I. He was a formidable persuader and was influential in the halls of power, counting Eleanor Roosevelt, senators, representatives, cabinet secretaries, Supreme Court justices, union leaders, Hollywood moguls, and diplomats among his circle of friends. His style of work depended upon rallying enlightened elites, and he favored a placing effort into developing a civil rights bureaucracy over local and mass-oriented organizations. Walter White was an expert in the practice of “brokerage politics”: During decades when the majority of African Americans were legally disfranchised, White led the organization that gave them an effective voice, representing them and interpreting their demands and desires (as he understood them) to those in power. Two examples of this were highlighted in the first part of this essay: the anti-lynching crusade, and the lobbying of President Truman, which resulted in To Secure These Rights . A third example is his essential role in producing Marian Anderson’s iconic 1939 Easter Sunday concert at the Lincoln Memorial, which drew the avid support of President Roosevelt and members of his administration, the Congress, and the Supreme Court. His style of leadership was, before the emergence of direct mass action in the years after White’s death in 1955, the dominant one in the Civil Rights Movement.

There are many excellent books that study the development of the Civil Rights Movement in one locality or state. An excellent addition to the collection of local studies is Battling the Plantation Mentality , by Laurie B. Green, which focuses on Memphis and the surrounding rural areas of Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi between the late 1930s and 1968, when Martin Luther King was assassinated there. Like the best of the local studies, this book presents an expanded definition of civil rights that encompasses not only desegregation of public facilities and the attainment of legal rights but also economic and political equality. Central to this were efforts by African Americans to define themselves and shake off the cultural impositions and mores of Jim Crow. During WWII, unionized black men went on strike in the defense industry to upgrade their job classifications. Part of their grievances revolved around wages and working conditions, but black workers took issue, too, with employers’ and the government’s reasoning that only low status jobs were open to blacks because they were less intelligent and capable. In 1955, six black female employees at a white-owned restaurant objected to the owner’s new method of attracting customers as degrading and redolent of the plantation: placing one of them outside dressed as a mammy doll to ring a dinner bell. When the workers tried to walk off the job, the owner had them arrested, which gave rise to local protest. In 1960, black Memphis activists helped support black sharecroppers in surrounding counties who were evicted from their homes when they initiated voter registration drives. The 1968 sanitation workers strike mushroomed into a mass community protest both because of wage issues and the strikers’ determination to break the perception of their being dependent, epitomized in their slogan “I Am a Man.” This book also shows that not everyone was able to cast off the plantation mentality, as black workers and energetic students at LeMoyne College confronted established black leaders whose positions and status depended on white elites’ sufferance.

Brown v. Board of Education: A Brief History with Documents , edited by Waldo E. Martin, Jr., contains an insightful 40-page essay that places both the NAACP’s legal strategy and 1954 Brown decision in multiple contexts, including alternate approaches to incorporating African American citizens into the American nation, and the impact of World War II and the Cold War on the road to Brown . The accompanying documents affirm the longstanding black freedom struggle, including demands for integrated schools in Boston in 1849, continuing with protests against the separate but equal ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson of 1896, and important items from the NAACP’s cases leading up to Brown . The documents are prefaced by detailed head notes and provocative discussion questions.

Debating the Civil Rights Movement , by Steven F. Lawson and Charles Payne, is likewise focused on instruction and discussion. This essay has largely focused on the development of the Civil Rights Movement from the standpoint of African American resistance to segregation and the formation organizations to fight for racial, economic, social, and political equality. One area it does not explore is how the federal government helped to shape the movement. Steven Lawson traces the federal response to African Americans’ demands for civil rights and concludes that it was legislation, judicial decisions, and executive actions between 1945 and 1968 that was most responsible for the nation’s advance toward racial equality. Charles Payne vigorously disagrees, focusing instead on the protracted grassroots organizing as the motive force for whatever incomplete change occurred during those years. Each essay runs about forty pages, followed by smart selections of documents that support their cases.

Kenneth R. Janken is Professor of African and Afro-American Studies and Director of Experiential Education, Office of Undergraduate Curricula at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the author of White: The Biography of Walter White, Mr. NAACP and Rayford W. Logan and the Dilemma of the African American Intellectual . He was a Fellow at the National Humanities Center in 2000-01.

Illustration credits

To cite this essay: Janken, Kenneth R. “The Civil Rights Movement: 1919-1960s.” Freedom’s Story, TeacherServe©. National Humanities Center. DATE YOU ACCESSED ESSAY. <https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1917beyond/essays/crm.htm>

NHC Home | TeacherServe | Divining America | Nature Transformed | Freedom’s Story About Us | Site Guide | Contact | Search

TeacherServe® Home Page National Humanities Center 7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256 Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709 Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535 Copyright © National Humanities Center. All rights reserved. Revised: April 2010 nationalhumanitiescenter.org

Site Content

The national movement.

Irfan Habib

Tulika Books

Pub Date: September 2013

ISBN: 9788189487799

Format: Paperback

List Price: $11.00 £8.99

Shipping Options

Purchasing options are not available in this country.

About the Author

- Asian Studies

- Asian Studies: South Asian History

- History: South Asian History

Essay: The Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights Movement sought to win the American promise of liberty and equality during the twentieth century. From the early struggles of the 1940s to the crowning successes of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts that changed the legal status of African-Americans in the United States, the Civil Rights Movement firmly grounded its appeals for liberty and equality in the Constitution and Declaration of Independence. Rather than rejecting an America that discriminated against a particular race, the movement fought for America to fulfill its own universal promise that “all men are created equal.” It worked for American principles within American institutions rather than against them.

African-Americans endured racial prejudice that compelled them to fight racism in World War II while fighting in segregated units. It was particularly hard to accept because the war was fought against the racist Nazis who were attempting to eradicate the Jews grounded in racially-based totalitarianism. For black soldiers, the stark contradiction with American wartime ideals was as repulsive as their daily condition of fighting separately. Many black units—most famously the Tuskegee Airmen—fought just as courageously as their white counterparts. Fighting for the “Double V” for victory over totalitarianism and racism, returning black veterans were not keen on returning to the Jim Crow South with legal (de jure) segregation nor to a North with informal (de facto) segregation.

On the national level, African-Americans sought to overturn segregation with legal challenges up to the Supreme Court, pressuring presidents to enforce equality, and lobbying Congress for changes in the law of the land.

In the postwar years, civil rights leaders prepared a dual strategy of attacking all discrimination throughout American society. On the national level, African-Americans sought to overturn segregation with legal challenges up to the Supreme Court, pressuring presidents to enforce equality, and lobbying Congress for changes in the law of the land. On the local level, marches were held to demonstrate the fundamental immorality and violence of segregation and to change local laws.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was established by W.E.B. DuBois and other black and white, male and female reformers in 1909 to struggle for civil rights, helped lead the legal battle in the courts. The NAACP legal team, led by Thurgood Marshall, who would later become the first black justice on the Supreme Court, scored the first major success of the Civil Rights Movement with Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) decision that indirectly overturned Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which had set the precedent for legalizing segregation. New Chief Justice Earl Warren persuaded his fellow justices to issue a unanimous 9-0 decision for the moral force to overcome expected white southern resistance. The outcome was a landmark for black equality that initiated the Civil Rights Movement.

The good outcome led many to overlook the questionable legal reasoning employed in the decision. The Supreme Court shockingly admitted white and black schools were equal despite evidence to the contrary. Moreover, the Court stated that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment had “inconclusive” origins related to segregated schools and doubted whether it could be applied to this case. Instead, the Court turned to social science as the basis for its decision. It referred to experiments in which black children played with dolls of different races. Members of the Court misread the evidence because the results of the studies actually showed that the segregated black children chose to play with black dolls. The Court mistakenly reported that the black children played more with the white dolls and had a “feeling of inferiority.”

The Court settled for declaring the edict that segregated schools were “inherently unequal” based on dubious social science and missed an opportunity for a constitutionally-grounded precedent banning all racial discrimination.

In Plessy v. Ferguson , Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote this powerful dissent: “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of our civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” (John Marshall Harlan, Plessy v. Ferguson Dissenting Opinion, 1896).

By ignoring Harlan’s understanding of the equality principle in the Constitution and settling for the use of social science, Chief Justice Warren diminished the constitutional force of the decision, which, if read narrowly, did not exactly overturn Plessy .

Even with the unanimous decision that Chief Justice Warren sought, the case encountered opposition, and it took more than a decade of direct action by African-Americans and others to win equality. In 1955, the Montgomery Bus Boycott initiated a decade of local demonstrations against segregation in the South. In December 1955, Rosa Parks courageously refused to give up her bus seat to a white man because she was tired of being treated like a second-class citizen. African-Americans applied economic pressure for more than one year to force concessions for desegregation at the local level, and a charismatic young Baptist minister, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., provided vision and leadership for the emerging movement at Montgomery.

As a result of the Brown decision, many white politicians and ordinary citizens engaged in what they called “massive resistance” to oppose desegregation. In 1957, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus refused to use the state National Guard to protect black children at Little Rock High School. President Dwight Eisenhower sent in troops from the 101st Airborne Division to compel local desegregation and protect the nine black students while federalizing the Arkansas National Guard to block Faubus. The Little Rock Nine attended school under the watchful eye of federal troops. The principles of equality and constitutional federalism came into conflict during this incident because the national government used the military to impose integration at the local level.

In 1957, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus refused to use the state National Guard to protect black children at Little Rock High School. President Dwight Eisenhower sent in troops from the 101st Airborne Division to compel local desegregation and protect the nine black students while federalizing the Arkansas National Guard to block Faubus.

In the early 1960s, African-Americans continued to press for equality at the local and national levels. In 1960, black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina started a wave of “sit-ins” in which they took seats reserved for whites at segregated lunch counters. The sit-ins led to applying the economic pressure of a boycott that successfully desegregated the local lunch counters.

In 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. used his moral vision and rhetoric to achieve the greatest successes of the movement for black equality and the end of segregation. King helped to organize marches in Birmingham, Alabama, where police dogs and fire hoses were turned on the Birmingham marchers and caused shock and outrage across the nation when the violence was televised. King and hundreds of others were arrested for demonstrating without a permit.

From his jail cell, King wrote his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” defending the civil rights demonstrations by quoting the great Christian authority St. Augustine that “an unjust law is no law at all.” Employing the principles of America’s Founders, King explained that a just law is a “man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God.” King posited that just laws uplift the human person while unjust laws “distort the soul” (Martin Luther King, Jr. “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” April 16, 1963).

He argued that just laws are rooted in human equality, while unjust laws give a false sense of superiority and inferiority. Moreover, segregation laws had been inflicted upon a minority who had no say in making the laws and thereby passed without consent, violating American principles of republican self-government.

King closed the letter by asserting that the Civil Rights Movement was “standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence” (Martin Luther King, Jr. “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” April 16, 1963).

On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy responded and addressed the nation on television. “We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution,” he told the nation. For Kennedy, the question was “whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities” (John F. Kennedy, “Civil Rights Address,” June 11, 1963).

Kennedy was mindful of the historical significance of the year when he appealed to Lincoln’s Proclamation freeing the slaves: “One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free…And this Nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free” (John F. Kennedy, “Civil Rights Address,” June 11, 1963).

On August 28, 1963, the greatest event of the Civil Rights Movement occurred with the March on Washington. More than 250,000 blacks and whites, young and old, clergy and laity, descended upon the capital in support of the proposed civil rights bill. From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, King evoked great documents of freedom when he said “Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation” (Martin Luther King, Jr. “I Have A Dream,” August 28, 1963). The Emancipation Proclamation freed the slaves one hundred years before on January 1, 1863. Simultaneously, he also subtly referred to the other great document of 1863, Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address,” which was inscribed in the wall of the memorial, and begins, “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” (Abraham Lincoln, “Gettysburg Address,” November 19, 1863).

King offered high praise for the “architects of our republic” who wrote the “magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.” King began his evocative peroration “I Have a Dream” by declaring that his dream is “deeply rooted in the American dream.” “One day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed. ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal’” (Martin Luther King, Jr. “I Have A Dream,” August 28, 1963).

African-Americans won the fruits of their decades of struggle for civil rights when Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Civil Rights Act legally ended segregation in all public facilities. The act had to overcome a Southern filibuster in the Senate and the fears of conservatives in both parties that it was an unconstitutional intrusion of the federal government upon the rights of the states and into local affairs and private businesses.

Although the Fifteenth Amendment had been ratified a hundred years before, African Americans still voted at low rates, especially in the Deep South. A number of devices—literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses that prevented descendants of slaves from voting—severely curtailed black suffrage. Violence and intimidation were the main vehicles of preventing African-Americans from voting in the mid-1960s.

In March 1965, Martin Luther King and other leaders organized marches in Selma, Alabama, for voting rights. After enduring beatings by club-wielding mounted police officers on “Bloody Sunday,” the marchers eventually set out again several days later and reached Montgomery under the watchful eye of federal troops. Congress soon passed the Voting Rights of 1965, banning abridgment of the right to vote on account of race.

Yet in the wake of the great legislative triumphs for social and voting equality the summer of 1965 (and successive summers) witnessed the explosion of racial violence and rioting by black citizens in American cities. Despite gaining rights of equal opportunity African-Americans still lived under obvious economic disparities with whites. The passage of federal laws securing equal opportunity led to rising expectations of immediate equality, which did not happen. Young “Black Power” advocates also began advocating self-reliance as a race, a celebration of African heritage, and a rejection of white society. Forming groups like the Black Panthers, a minority of young African-Americans spoke in passionate terms advocating violence, leading to confrontations with police. Many white Americans were shocked and confused at the urban riots occurring just after legal equality for African-Americans had been achieved.

In the 1970s and 1980s, plans of “affirmative action” were introduced in college admissions and in hiring for public and private jobs that soon became controversial. Intended to remedy the historic wrongs of slavery and segregation, affirmative action policies established preference or quotas for the number of African-Americans (and soon women and other minorities) who would be admitted or hired. Its proponents sought to achieve an equality of outcome in society rather than merely equal opportunity in American society. Some whites complained that this was “reverse discrimination” against whites that tolerated lower standards for the benefited groups. The most notable Supreme Court case addressing the issue was the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) decision, in which racial preferences, but not racial quotas, were upheld.

The Supreme Court essentially agreed with the supporters of affirmative action who argued that “discrimination against members of the white ‘majority’ cannot be suspect if its purpose can be characterized as ‘benign’” (Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., Regents of the University of California v. Bakke , Opinion, 1978)

Related Content

The Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights Movement sought to win the American promise of liberty and equality during the twentieth-century. From the early struggles of the 1940s to the crowning successes of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts that changed the legal status of African-Americans in the United States, the Civil Rights Movement firmly grounded its appeals for liberty and equality in the Constitution and Declaration of Independence. Rather than rejecting an America that discriminated against a particular race, the movement fought for America to fulfill its own universal promise that “all men are created equal.” The Civil Rights Movement worked for American principles within American institutions rather than against them.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Abolitionism to Jim Crow

- Du Bois to Brown

- Montgomery bus boycott to the Voting Rights Act

- From Black power to the assassination of Martin Luther King

- Into the 21st century

- Black Lives Matter and Shelby County v. Holder

When did the American civil rights movement start?

- What did Martin Luther King, Jr., do?

- What is Martin Luther King, Jr., known for?

- Who did Martin Luther King, Jr., influence and in what ways?

- What was Martin Luther King’s family life like?

American civil rights movement

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- NeoK12 - Educational Videos and Games for School Kids - Civil Rights Movement

- History Learning Site - The Civil Rights Movement in America 1945 to 1968

- Library of Congress - The Civil Rights Movement

- National Humanities Center - Freedom's Story - The Civil Rights Movement: 1919-1960s

- John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum - Civil Rights Movement

- civil rights movement - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- civil rights movement - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The American civil rights movement started in the mid-1950s. A major catalyst in the push for civil rights was in December 1955, when NAACP activist Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a public bus to a white man.

Who were some key figures of the American civil rights movement?

Martin Luther King, Jr. , was an important leader of the civil rights movement. Rosa Parks , who refused to give up her seat on a public bus to a white customer, was also important. John Lewis , a civil rights leader and politician, helped plan the March on Washington .

What did the American civil rights movement accomplish?

The American civil rights movement broke the entrenched system of racial segregation in the South and achieved crucial equal-rights legislation.

What were some major events during the American civil rights movement?

The Montgomery bus boycott , sparked by activist Rosa Parks , was an important catalyst for the civil rights movement. Other important protests and demonstrations included the Greensboro sit-in and the Freedom Rides .

What are some examples of civil rights?

Examples of civil rights include the right to vote, the right to a fair trial, the right to government services, the right to a public education, and the right to use public facilities.

Essay on National Movement

Students are often asked to write an essay on National Movement in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on National Movement

Introduction.

The National Movement refers to the struggle for freedom and independence from colonial rule. It was a mass movement that united people from all walks of life.

Role of Leaders

Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Subhash Chandra Bose played a crucial role. They mobilized masses and led various campaigns for independence.

The National Movement resulted in India gaining independence in 1947. It also instilled a sense of unity and nationalism among Indians.

250 Words Essay on National Movement

Introduction to the national movement, the genesis of national movement.

The genesis of national movements can be traced back to the 18th and 19th centuries, when nations across Europe and Asia began to rise against colonial powers. This period was marked by a growing consciousness of national identity, fueled by the Enlightenment’s ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

The Role of Intellectuals and Masses

Intellectuals played a significant role in the national movement. They inspired the masses with their writings, speeches, and actions, fostering a sense of national pride and unity. Simultaneously, the masses, driven by the desire for freedom and justice, participated actively in protests, strikes, and revolutions, making the national movement a truly inclusive struggle.

Impact of the National Movement

The national movement had profound impacts, leading to the dismantling of colonial empires and the emergence of independent nations. It fostered democratic values, human rights, and the rule of law, shaping the political landscape of the modern world. Moreover, it stimulated cultural and social transformation, promoting national languages, arts, and traditions.

In conclusion, the national movement was a transformative period that redefined the course of history. It was not just a fight for political freedom, but also a struggle for cultural identity, social justice, and human dignity. It serves as a testament to the indomitable spirit of humanity, inspiring future generations to uphold the values of freedom and justice.

500 Words Essay on National Movement

The National Movement, also known as the Indian Independence Movement, was a series of historical events that marked India’s struggle for freedom from British rule. It was a vibrant, multifaceted movement that involved various political organizations, philosophies, and leaders, united by their common goal of ending British colonial control.

The Birth of the National Movement

The rise of extremist ideology.

The early 20th century witnessed a shift from moderate to extremist ideology in the National Movement. Leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, and Bipin Chandra Pal advocated for Swaraj (self-rule) and used methods like boycotts, strikes, and public processions to mobilize the masses. The 1905 partition of Bengal by Lord Curzon was a significant event that ignited widespread protests and marked the beginning of the Swadeshi Movement.

Impact of World War I and II

World War I and II were pivotal in shaping the National Movement. The British government’s decision to involve India in the wars without consulting Indian leaders led to widespread resentment. The post-WWI period saw the emergence of Mahatma Gandhi as a significant leader who introduced the concept of Satyagraha (non-violent resistance). His leadership during the Non-Cooperation Movement (1920-22) and the Civil Disobedience Movement (1930-34) galvanized the masses and intensified the struggle for independence.

The Final Phase

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Top of page

Collection Civil Rights History Project

Youth in the civil rights movement.

At its height in the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement drew children, teenagers, and young adults into a maelstrom of meetings, marches, violence, and in some cases, imprisonment. Why did so many young people decide to become activists for social justice? Joyce Ladner answers this question in her interview with the Civil Rights History Project, pointing to the strong support of her elders in shaping her future path: “The Movement was the most exciting thing that one could engage in. I often say that, in fact, I coined the term, the ‘Emmett Till generation.’ I said that there was no more exciting time to have been born at the time and the place and to the parents that movement, young movement, people were born to… I remember so clearly Uncle Archie who was in World War I, went to France, and he always told us, ‘Your generation is going to change things.’”

Several activists interviewed for the Civil Rights History Project were in elementary school when they joined the movement. Freeman Hrabowski was 12 years old when he was inspired to march in the Birmingham Children’s Crusade of 1963. While sitting in the back of church one Sunday, his ears perked up when he heard a man speak about a march for integrated schools. A math geek, Hrabowski was excited about the possibility of competing academically with white children. While spending many days in prison after he was arrested at the march, photographs of police and dogs attacking the children drew nationwide attention. Hrabowski remembers that at the prison, Dr. King told him and the other children, “What you do this day will have an impact on children yet unborn.” He continues, “I’ll never forget that. I didn’t even understand it, but I knew it was powerful, powerful, very powerful.” Hrabowski went on to become president of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, where he has made extraordinary strides to support African American students who pursue math and science degrees.

As a child, Marilyn Luper Hildreth attended many meetings of the NAACP Youth Council in Oklahoma City because her mother, the veteran activist Clara Luper, was the leader of this group. She remembers, “We were having an NAACP Youth Council meeting, and I was eight years old at that time. That’s how I can remember that I was not ten years old. And I – we were talking about our experiences and our negotiation – and I suggested, made a motion that we would go down to Katz Drug Store and just sit, just sit and sit until they served us.” This protest led to the desegregation of the drug store’s lunch counter in Oklahoma City. Mrs. Hildreth relates more stores about what it was like to grow up in a family that was constantly involved in the movement.

While some young people came into the movement by way of their parents’ activism and their explicit encouragement, others had to make an abrupt and hard break in order to do so, with some even severing familial ties. Joan Trumpauer Mulholland was a young white girl from Arlington, Virginia, when she came to realize the hypocrisy of her segregated church in which she learned songs such as “Jesus loves the little children, red and yellow, black and white.” When she left Duke University to join the movement, her mother, who had been raised in Georgia, “thought I had been sort of sucked up into a cult… it went against everything she had grown up and believed in. I can say that a little more generously now than I could have then.” Phil Hutchings’ father was a lifetime member of the NAACP, but couldn’t support his son when he moved toward radicalism and Black Power in the late 1960s. Hutchings reflects on the way their different approaches to the struggle divided the two men, a common generational divide for many families who lived through those times: “He just couldn’t go beyond a certain point. And we had gone beyond that… and the fact that his son was doing it… the first person in the family who had a chance to complete a college education. I dropped out of school for eleven years… He thought I was wasting my life. He said, ‘Are you … happy working for Mr. Castro?’”

Many college student activists sacrificed or postponed their formal education, but they were also picking up practical skills that would shape their later careers. Michael Thelwell remembers his time as a student activist with the Nonviolent Action Group, an organization never officially recognized by Howard University and a precursor to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC): “I don’t think any of us got to Howard with any extensive training in radical political activism. By that I mean, how do you write a press conference [release]? How you get the attention of the press? How do you conduct a nonviolent protest? How do you deal with the police? How do you negotiate or maneuver around the administration? We didn’t come with that experience.” Thelwell’s first job after he graduated from college was to work for SNCC in Washington, D.C., as a lobbyist.

Similar reflections about young people in the freedom struggle are available in other collections in the Library. One such compelling narrative can be found in the webcast of the 2009 Library of Congress lecture by journalist and movement activist, Tracy Sugarman, entitled, “We Had Sneakers, They Had Guns: The Kids Who Fought for Civil Rights in Mississippi.” As is readily apparent from that lecture and the previous examples, drawn from the Civil Rights History Project collection, the movement completely transformed the lives of young activists. Many of them went on to great success as lawyers, professors, politicians, and leaders of their own communities and other social justice movements. They joined the struggle to not only shape their own futures, but to also open the possibilities of a more just world for the generations that came behind them.

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

History Grade 11 - Topic 4 Essay Questions

Essay Question:

To what extent were Black South Africans were deprived of their political, economic, and social rights in the early 1900s and how did this reality pave the way for the rise of African Nationalism? Present an argument in support of your answer using relevant historical evidence. [1]

Background and historical overview:

There was no South Africa (as we know it today) before 1910. Britain had defeated Boer Republics in the South African War which date from (1899–1903). There were four separate colonies: Cape, Natal, Orange River, Transvaal colonies and each were ruled by Britain. They needed support of white settlers in colonies to retain power. [2] In 1908, about 33 white delegates met behind closed doors to negotiate independence for Union of South Africa. The views and opinions of 85% of country’s future citizens (black people) not even considered in these discussions. British wanted investments protected, labour supplies assured, and agreed on the fundamental question to give political/economic power to white settlers. [3] This essay pushes back in time to analyse how this violent context in South African history served as an ideological backdrop for the rise of African nationalism in the country and elsewhere in the world.

The Union Constitution of 1910 placed political power in hands of white citizens. However, a small number of educated black, coloured citizens allowed to elect few representatives to Union parliament. [4] More generally, it was only whites who were granted the right to vote. They imagined a ‘settler nation’ where was no room for blacks with rights. In this regard, white citizens called selves ‘Europeans’. Furthermore, all symbols of new nation, European language (mainly English and Dutch), religion, school history. In this view, African languages, histories, culture were portrayed as inferior. [5]

Therefore, racism was an integral feature in colonial societies, and this essentially meant that Africans were seen as members of inferior ‘tribes’ and thus should practise traditions in ‘native’ reserves. Whilst, on the other hand, in the settler (white) nation, black people were recognized only as workers in farms, mines, factories owned by whites. Thus, black people were denied of their political rights, cultural recognition, economic opportunities, because of these entrenched processes and politics of exclusion. In 1910 large numbers of black South African men were forced to become migrant workers on mines, factories, expanding commercial farms. In 1913, the infamous Natives Land Act, worsened the situation for black people as land allocated to black people by the Act was largely infertile and unsuitable for agriculture. [6]

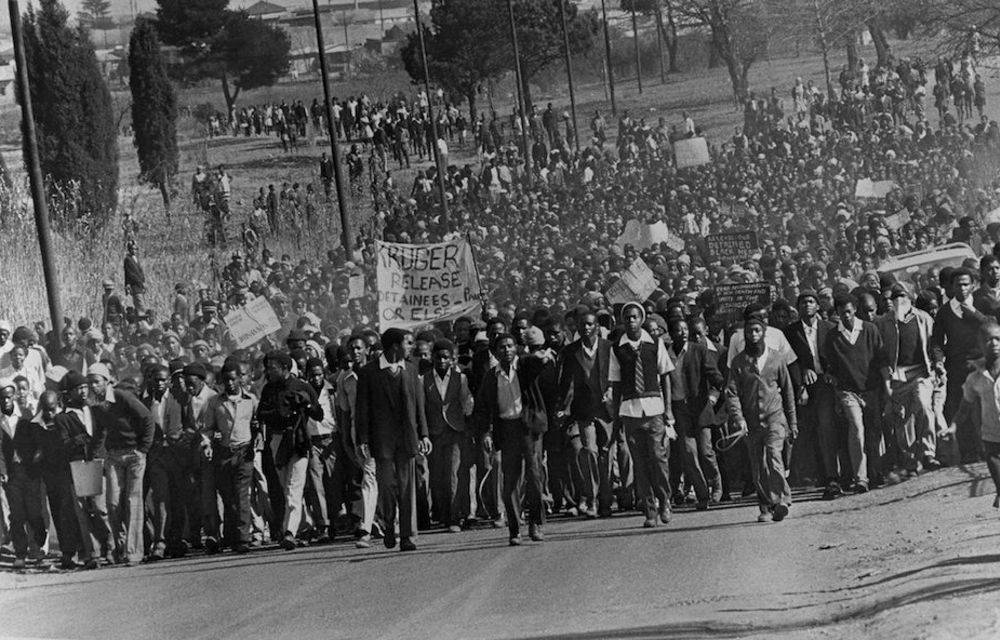

Rise of African Nationalism:

In the 19th century, the Western-educated African, coloured, Indian middle class who grew up mainly in the Cape and Natal, mostly professional men (doctors, lawyers, teachers, newspaper editors) and were proud of their African, Muslim, Indian heritage embraced idea of progressive ‘colour-blind’ western civilisation that could benefit all people. This was a more worldly outlook or form of nationalism which recognized all non-white groupings across the colonial world as victims of colonial racism and violence. [7] However, another form of nationalism recognized the differences within the colonized groups and argued for a stricter and more specific definition of what it means to be African in a colonial world. These were some differences within the umbrella body of African nationalism and were firmly anchored during the course of the 20th century.

African Peoples’ Organization:

One of the African organisations that led to the rise of African nationalism was the African People’s Organisation (APO). At first the APO did not concern itself with rights of black South Africans. They committed themselves to the vision that all oppressed racial groups must work together to achieve anything. Therefore, a delegation was sent to London in 1909 to fight for rights for coloured (‘coloured’. In this context, ‘everyone who was a British subject in South Africa and who was not a European’). [8]

Natal Indian Congress:

Natal Indian Congress Natal Indian Congress (NIC) was an important influence in the development of non-racial African nationalism in South Africa. Arguably, it was one of the first organisations in South Africa to use word ‘congress’. It was formed in 1894 to mobilise the Indian opposition to racial discrimination in Colony. [9] The founder of this movement was MK Gandhi who later spearheaded a massive peaceful resistance (Satyagraha) to colonial rule. This protest forced Britain to grant independence to India, 1947. The NIC organised many protests and more generally campaigned for Indian rights. In 1908, hundreds of Indians gathered outside Johannesburg Mosque in protest against law that forced Indians to carry passes, passive resistance campaigns of Gandhi and NIC succeeded in Indians not having to carry passes. But, however, they failed to win full citizenship rights as the NIC did not join united national movement for rights of all citizens until 1930s, 1940s

South African Native National Congress (now known as African National Congress):

In response to Union in 1910, young African leaders (Pixley ka Isaka Seme, Richard Msimang, George Montsioa, Alfred Mangena) worked with established leaders of South African Native Convention to promote formation of a national organization. The larger aim was to form a national organisation that would unify various African groups. [10] On 8 January 1912, first African nationalist movement formed at a meeting in Bloemfontein. South African National Natives Congress (SANNC) were mainly attended by traditional chiefs, teachers, writers, intellectuals, businessmen. Most delegates had received missionary education. They strongly believed in 19th century values of ‘improvement’ and ‘progress’ of Africans into a global European ‘civilisation’ and culture. In 1924, the SANNC changed name to African National Congress (ANC), in order to assert an African identity within the movement. [11]

Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU):

The Industrial and Commercial Workers Union African protest movements that helped foster growing African nationalism in early 1920s . Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) was formed in 1919 was led by Clements Kadalie, Malawian worker. This figure had led successful strike of dockworkers in Cape Town. Mostly active among farmers and migrant workers. But, only temporarily away from their farms and was very difficult to organise. The central question to pose is to examine the ways in which the World War II influence the rise of African nationalism? Essentially, there were various ways that WW II influenced the rise of African nationalism. [12] Firstly, through the Atlantic Charter, AB Xuma’s, African claims in relation to this Charter. In addition, the influence of politicized soldiers returning from War had a significant impact.

The Atlantic Charter and AB Xuma’s African claims Churchill and Roosevelt issued the Atlantic Charter in 1941, describing the world they would like to see after WWII. To the ANC and African nationalists generally, the Atlantic Charter amounted to promise for freedom in Africa once war was over. Britain recruited thousands of African soldiers to fight in its armies (nearly two million Africans recruited as soldiers, porters, scouts for Allies during war). This persuaded Africans to sign up and Britain called it ‘a war for freedom’. [13] The soldiers returning home expected Britain to honour their sacrifice, however, the recognition they expected did not arrive and thus became bitter, discontented, and only had fought to protect interests of colonial powers only to return to exploitation and indignities of colonial rule.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this essay has attempted to examine the historical circumstances in which black people were denied of their political, economic, and social rights in the early 1990s. There are various that must be acknowledged in order to have a granular understanding of the larger and longer history of African nationalism, and this examination may exceed the scope of this essay. However, the central argument made here is that the rise of African nationalism in all its different ethos and manifestations was premised on humanizing black people in various parts of the colonial world. To stress this point, African nationalism emerged as a vehicle of resistance and humanization. Finally, African nationalism cannot be read outside the international context (as shown throughout the paper), as we have to take into account various factor which effectively influenced the spurge of this ideological outlook in society.

This content was originally produced for the SAHO classroom by Ayabulela Ntwakumba & Thandile Xesi.

[1] National Senior Certificate.: “Grade 11 November 2019 History Paper 2 Exam,” National Senior Certificate, November 2019. Eastern Cape Province Education.

[2] Williams, Donovan. "African nationalism in South Africa: origins and problems." The Journal of African History 11, no. 3 (1970): 371-383.

[3] Feit, Edward. "Generational Conflict and African Nationalism in South Africa: The African National Congress, 1949-1959." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 5, no. 2 (1972): 181-202.

[4] Chipkin, Ivor. "The decline of African nationalism and the state of South Africa." Journal of Southern African Studies 42, no. 2 (2016): 215-227.

[5] Prinsloo, Mastin. "‘Behind the back of a declarative history’: Acts of erasure in Leon de Kock's Civilizing Barbarians: Missionary narrative and African response in nineteenth century South Africa." The English Academy Review 15, no. 1 (1998): 32-41.

[6] Gilmour, Rachael. "Missionaries, colonialism and language in nineteenth‐century South Africa." History Compass 5, no. 6 (2007): 1761-1777.

[7] Lester, Alan. Imperial networks: Creating identities in nineteenth-century South Africa and Britain. Routledge, 2005.

[8] Van der Ross, Richard E. "The founding of the African Peoples Organization in Cape Town in 1903 and the role of Dr. Abdurahman." (1975).

[9] Vahed, Goolam, and Ashwin Desai. "A case of ‘strategic ethnicity’? The Natal Indian Congress in the 1970s." African Historical Review 46, no. 1 (2014): 22-47.

[10] Suttner, Raymond. "The African National Congress centenary: a long and difficult journey." International Affairs 88, no. 4 (2012): 719-738.

[11] Houston, G. "Pixley ka Isaka Seme: African unity against racism." (2020).

[12] Xuma, A. B. "African National Congress invitation to emergency conference of all Africans."

[13] Kumalo, Simangaliso. "AB Xuma and the politics of racial accommodation versus equal citizenship and its implication for nation-building and power-sharing in South Africa."

- Bennett-Smyth, T., 2003, September. Transcontinental Connections: Alfred B Xuma and the African National Congress on the World Stage. In workshop on South Africa in the 1940s, Southern African Research Centre, Kingston, Canada.

- Chipkin, I., 2016. The decline of African nationalism and the state of South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 42(2), pp.215-227.

- Feit, E., 1972. Generational Conflict and African Nationalism in South Africa: The African National Congress, 1949-1959. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 5(2), pp.181-202.

- Kumalo, S., AB Xuma and the politics of racial accommodation versus equal citizenship and its implication for nation-building and power-sharing in South Africa.

- Moeti, M.T., 1982. ETHIOPIANISM: SEPARATIST ROOTS OF AFRICAN NATIONALISM IN SOUTH AFRICA.

- Rotberg, R., "African nationalism: concept or confusion?." The Journal of Modern African Studies 4, no. 1. pp. 33-46.

- Swan, M., 1984. The 1913 Natal Indian Strike. Journal of Southern African Studies, 10(2), pp.239-258.

- Vahed, G. and Desai, A., 2014. A case of ‘strategic ethnicity’? The Natal Indian Congress in the 1970s. African Historical Review, 46(1), pp.22-47.

- Van der Ross, R.E., 1975. “The founding of the African Peoples Organization in Cape Town in 1903 and the role of Dr. Abdurahman”.

- van Niekerk, R., 2014. SOCIAL DEMOCRACY AND THE ANC: BACK TO THE FUTURE?. A Lula Moment for South Africa: Lessons from Brazil, pp.47-61.

- Williams, D., 1970. “African nationalism in South Africa: origins and problems”. The Journal of African History, 11(3), pp.371-383.

Return to topic: Nationalism - South Africa, the Middle East, and Africa

Return to SAHO Home

Return to History Classroom

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

Nationalism Essay for Students and Children

400 words essay on nationalism.

First of all, Nationalism is the concept of loyalty towards a nation. In Nationalism, this sentiment of loyalty must be present in every citizen. This ideology certainly has been present in humanity since time immemorial. Above all, it’s a concept that unites the people of a nation. It is also characterized by love for one’s nation. Nationalism is probably the most important factor in international politics.

Why Nationalism Is Important?

Nationalism happens because of common factors. The people of a nation share these common factors. These common factors are common language, history , culture, traditions, mentality, and territory. Thus a sense of belonging would certainly come in people. It would inevitably happen, whether you like it or not. Therefore, a feeling of unity and love would happen among national citizens. In this way, Nationalism gives strength to the people of the nation.

Nationalism has an inverse relationship with crime. It seems like crime rates are significantly lower in countries with strong Nationalism. This happens because Nationalism puts feelings of love towards fellow countrymen. Therefore, many people avoid committing a crime against their own countrymen. Similarly, corruption is also low in such countries. Individuals in whose heart is Nationalism, avoid corruption . This is because they feel guilty to harm their country.

Nationalism certainly increases the resolve of a nation to defend itself. There probably is a huge support for strengthening the military among nationalistic people. A strong military is certainly the best way of defending against foreign enemies. Countries with low Nationalism, probably don’t invest heavily in the military. This is because people with low Nationalism don’t favor strong militaries . Hence, these countries which don’t take Nationalism seriously are vulnerable.

Nationalism encourages environmental protection as well. People with high national pride would feel ashamed to pollute their nation. Therefore, such people would intentionally work for environment protection even without rules. In contrast, an individual with low Nationalism would throw garbage carelessly.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Contemporary Nationalism

Nationalism took an ugly turn in the 20th century with the emergence of Fascism and Nazism. However, that was a negative side of Nationalism. Since then, many nations gave up the idea of aggressive Nationalism. This certainly did not mean that Nationalism in contemporary times got weak. People saw strong Nationalism in the United States and former USSR. There was a merger of Nationalism with economic ideologies like Capitalism and Socialism.

In the 21st century, there has been no shortage of Nationalism. The popular election of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin is proof. Both these leaders strongly propagate Nationalism. Similarly, the election victory of other nationalistic leaders is more evidence.

Nationalism is a strong force in the world that is here to say. Nationalism has a negative side. However, this negative side certainly cannot undermine the significance of Nationalism. Without Nationalism, there would have been no advancement of Human Civilization.

500 Words Essay on Nationalism

Nationalism is an ideology which shows an individual’s love & devotion towards his nation. It is actually people’s feelings for their nation as superior to all other nations. The concept of nationalism in India developed at the time of the Independence movement. This was the phase when people from all the areas/caste/religion etc collectively fought against British Raj for independence. Hence nationalism can be called as collective devotion of all the nationals towards their country.

Introduction of Nationalism in India:

The first world war (1919) had far-reaching consequences on the entire world. After the first world war, some major movements broke out in India like Satyagrah & Non-co-operation movement. This has sown the seeds of nationalism in Indians. This era developed new social groups along with new modes of struggle. The major events like Jalianwala Bagh massacre & Khilafat movement had a strong impact on the people of India.

Thus, their collective struggle against colonialism brought them together and they have collectively developed a strong feeling of responsibility, accountability, love, and devotion for their country. This collective feeling of the Indian people was the start of the development of Nationalism. Foundation of Indian National Congress in 1885 was the first organized expression of nationalism in India.

Basis of Rising of Nationalism in India

There could be several basis of rising of nationalism in India:

- The Britishers came to India as traders but slowly became rulers and started neglecting the interests of the Indians. This led to the feeling of oneness amongst Indians and hence slowly led to nationalism.

- India developed as a unified country in the 19 th & 20 th century due to well-structured governance system of Britishers. This has led to interlinking of the economic life of people, and hence nationalism.

- The spread of western education, especially the English language amongst educated Indians have helped the knowledgeable population of different linguistic origin to interact on a common platform and hence share their nationalist opinions.

- The researches by Indian and European scholars led to the rediscovery of the Indian past. The Indian scholars like Swami Vivekanand & European scholars like Max Mueller had done historical researched & had glorified India’s past in such a manner that Indian peoples developed a strong sense of nationalism & patriotism.

- The emergence of the press in the 19 th century has helped in the mobilization of people’s opinion thereby giving them a common platform to interact for independence motion and also to promote nationalism.

- Various reforms and social movements had helped Indian society to remove the social evils which were withholding the societal development and hence led to rejoining of society.

- The development of well-led railway network in India was a major boost in the transportation sector. Hence making it easy for the Indian population to connect with each other.

- The international events like the French revolution, Unification of Italy & Germany, etc.have awakened the feelings of national consciousness amongst Indian people.

Though a lot of factors had led to rising of nationalism in India, the major role was played by First world war, Rowlatt act and Jaliawala bagh massacre. These major incidences have had a deep-down impact on the mind of Indians. These motivated them to fight against Britishers with a strong feeling of Nationalism. This feeling of nationalism was the main driving force for the independence struggle in India.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

India’s Struggle for Independence: Indian Freedom Movement

Last updated on July 23, 2024 by ClearIAS Team

In the 6-part framework to study modern Indian History , we have so far covered:

- India in 1750 .

- British Expansion .

- The changes introduced by the British .

- Popular Uprisings and Revolts against the British

- Socio-religious movements in India .

In this article (6th part), we discuss the emergence of Indian nationalism and India’s struggle for independence.

Table of Contents

Indian Nationalism

Note: Subscribe to the ClearIAS YouTube Channel to learn more.

India has been unified under many empires in its history like the Mauryan Empire and Mughal empire. A sense of oneness has been there for ages – even though most of the centralised administration in India didn’t last long.

With the end of Mughal rule, India broke into hundreds of princely states. The British – which were instrumental in the fall of the Mughal Empire – held control over the princely states and created the British Indian Empire .

UPSC CSE 2025: Study Plan ⇓

(1) ⇒ UPSC 2025: Prelims cum Mains

(2) ⇒ UPSC 2025: Prelims Test Series

(3) ⇒ UPSC 2025: CSAT

Note: To know more about ClearIAS Courses (Online/Offline) and the most effective study plan, you can call ClearIAS Mentors at +91-9605741000, +91-9656621000, or +91-9656731000.

However, most Indians were extremely dissatisfied with the exploitative foreign rule.

The educated Indians realised that the British always gave priority to their colonial interests and treated India only as a market.

They advocated for the political independence of India.

Foundation of Indian National Congress (INC) in 1885

The late nineteenth century witnessed the emergence of many political organisations in British India.

Indian National Congress (also known as Congress Party) founded in 1885 was the most prominent one.

Initially, its aim was to create a platform for civic and political dialogue between Indians and the British Raj and thus obtain a greater share of government for educated Indians.

Later, under the leaders like Mahatma Gandhi , Jawarhal Nehru , Subhas Chandra Bose , and Sardar Vallabhai Patel , the Congress party played a central role in organising mass movements against the British.

Partition of Bengal (1905)

Indian nationalism was gaining in strength and Bengal was the nerve centre of Indian nationalism in the early 1900s.

Lord Curzon, the Viceroy (1899-1905), attempted to ‘dethrone Calcutta’ from its position as the centre from which the Congress Party manipulated throughout Bengal, and indeed, the whole of India.

The decision to partition Bengal into two was in the air from December 1903.

Congress party – from 1903 to mid-1905 – tried moderate techniques of petitions, memoranda, speeches, public meetings and press campaigns. The objective was to turn to public opinion in India and England against the partition.

However, Viceroy Curzon 1905 formally announced the British Government’s decision for the partition of Bengal on 19 July 1905. The partition took effect on 16 October 1905.

The partition was meant to foster another kind of division – on the basis of religion. The aim was to place Muslim communalists as a counter to the Congress. Curzon promised to make Dacca the new capital.

This resulted in a lot of discontent among the Indians. Many considered this as a policy of ‘Divide and Rule’ by the British.

This triggered a self-sufficiency movement popularly known as the Swadeshi movement.

Also read: Dr. Rajendra Prasad: Architect of the Indian Republic

The Swadeshi Movement (1905-1908)

From conservative moderation to political extremism, from terrorism to incipient socialism, from petitioning and public speeches to passive resistance and boycott, all had their origins in the movement.

Swadeshi is a conjunction of two Sanskrit words: swa (“self”) and desh (“country”).

The movement popularised the use and consumption of indigenous products. Indians started ditching British goods for Indian products.

Women, students, and a large section of the urban and rural population of Bengal and other parts of India became actively involved in politics for the first time with Swadeshi Movement.

The message of Swadeshi and the boycott of foreign goods soon spread to the rest of the country.

The militant nationalists led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, Lajpat Rai and Aurobindo Ghosh were in favour of extending the movement to the rest of India and carrying it beyond the programme of just Swadeshi and boycott to a full-fledged political mass struggle. For them, the aim was Swaraj.

In 1906, the Indian National Congress at its Calcutta Session presided over by Dadabhai Naoroji, declared that the goal of the Indian National Congress was ‘self-government or Swaraj like that of the United Kingdom or the Colonies.

There were differences in the ideologies of the congressmen who were popularly known by the names Moderates and the Extremists. They had differences of opinion regarding the pace of the movement and the techniques of struggle to be adopted. This came to a head in the 1907 Surat session of the Congress where the party split (the two factions re-joined later).

This period also saw a breakthrough in Indian art, literature, music, science and industry.

It was, perhaps, in the cultural sphere that the impact of the Swadeshi Movement was most marked. The songs composed at that time by Rabindranath Tagore, Rajani Kanta Sen etc became the moving spirit for nationalists of all hues.

In art, this was the period when Abanindranath Tagore broke the domination of Victorian naturalism over Indian art and sought inspiration from the rich indigenous traditions of Mughal, Rajput and Ajanta paintings.

In science, Jagdish Chandra Bose, Prafulla Chandra Ray, and others pioneered original research that was praised the world over.

The Swadeshi period also saw the creative use of traditional popular festivals and melas as a means of reaching out to the masses. The Ganapati and Shivaji festivals, popularized by Tilak, became a medium for Swadeshi propaganda not only in Western India but also in Bengal.

Another important aspect of the Swadeshi Movement was the great emphasis given to self-reliance or ‘Atmasakti’in various fields meant the re-asserting of national dignity, honour and confidence.

Self-reliance also meant an effort to set up Swadeshi or indigenous enterprises. The period saw a mushrooming of Swadeshi textile mills, soap and match factories etc.

One of the major features of the programme of self-reliance was Swadeshi or National Education. In 1906, the National Council of Education was established. The vernacular medium was given stress from the primary to university level.

Corps of volunteers (or samitis as they were called) were another major form of mass mobilization widely used by the Swadeshi Movement. The Swadesh Bandhab Samiti set up by Ashwini Kumar Dutt was the most well-known volunteer organization of them all.

Reasons for the failure of the Swadeshi Movement

- The main drawback of the Swadeshi Movement was that it was not able to garner the support of the mass. The British use of communalism to turn the Muslims against the Swadeshi Movement was to a large extent responsible for this.

- During the Swadeshi phase, the peasantry was not organized around peasant demands. The movement was able to mobilize the peasantry only in a limited way.

- By mid-1908 repression took the form of controls and bans on public meetings, processions and the press.

- The internal squabbles, and especially, the split in the Congress (1907), the apex all-India organization, weakened the movement.

- The Swadeshi Movement lacked an effective organization and party structure.

- Lastly, the movement declined because of the very logic of mass movements itself — they cannot be sustained endlessly.