Cultural Deviance Theory – Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons

Kamalpreet Gill Singh (PhD)

This article was co-authored by Kamalpreet Gill Singh, PhD. Dr. Gill has a PhD in Sociology and has published academic articles in reputed international peer-reviewed journals. He holds a Master’s degree in Politics and International Relations and a Bachelor’s in Computer Science.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Cultural Deviance Theory states that crime is correlated strongly to the cultural values and norms prevalent in a society.

In other words, individuals may turn to crime not on account of any innate character traits, but because they are influenced by:

- The place they live in,

- The people they are surrounded by, and

- The socio-economic conditions of their micro-environment

Those three elements come together to form a unique subculture influencing the individual and their chances to turn to crime.

Usually, the theory is used to critique immigrant and working-class cultures, making it a highly controversial theory in the 21st Century!

Origins of Cultural Deviance Theory

The theory was born out of the work of University of Chicago sociologists Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay in the 1930s. Shaw and McKay were part of a larger theoretical project to understand social deviance and crime in the rapidly burgeoning immigrant neighborhoods of Chicago during this period.

The theory Shaw and McKay proposed came to be called the Social Disorganization Theory as it attributed delinquency to a disorganization or rupture of traditional societal norms by forces such as immigration and poverty.

The criminologist Walter B. Miller (1958) made significant additions to the work of Shaw, McKay and others. He added his own thesis that certain cultural values in lower-class societies (which were absent among the middle-classes) played a major role in contributing to social deviance or delinquent behavior.

Miller’s thesis came to be known as the cultural deviance theory.

Here are some scholarly definitions of the cultural deviance theory that have been paraphrased and can be used as such:

- Shaw and McKay (1969) proposed that the transmission of cultural norms that result in criminal or delinquent behavior is a cause of delinquent or criminal behavior.

- Miller (1958) suggested that delinquent behavior arose as a result of “focal concerns” or a set of issues that the subjects feel highly emotionally involved with, of “lower class culture”.

Related Theory: The Theory of Cultural Capital

Six Focal Concerns of Cultural Deviance Theory

Miller (1958) further identified six cornerstones of lower-class subculture that he called “focal concerns”.

According to Miller, a fixation of lower-class youths with these “focal concerns” led to increased delinquency. These six focal concerns were:

1. Trouble – According to Miller, “getting in trouble” and “staying out of trouble” were major concerns of lower-class youth (with trouble here defined as encounters with the law). This pointed towards a key feature of lower-class subculture in which respect for the law came not out of a sense of morality but from a fear of punishment.

2. Toughness – In lower class cultures, toughness, defined by a disregard for consequences, a contempt for literary, artistic, and scholarly pursuits including education, a pride in displays of unsentimentality, and an objectification of women, becomes a highly valued and desired attribute. Juveniles aspire to be “tough” in the sense described above to gain respect among their peers.

3. Smartness – Smartness, defined as being manipulative and possessing cunning, was said to be another prized attribute among juveniles in a lower-class culture. A “smart guy” is one who gets others to do his bidding without the direct use of violence. Think of the various depictions of “smart guys”, “wise guys”, and “smooth operators” in gangster movies who are always flirting with the law.

4. Excitement – Juveniles in lower-class cultures seem to be chasing the next thrill to overcome the monotony of lower-class culture. This often leads them to activities such joining gangs or doing drugs.

5. Fate – Feeling disempowered, members of the lower-classes may place a greater reliance on fate or luck than those of the middle classes. This may lead to an attitude of recklessness, as actions and their consequences may come to be seen as preordained, and thus beyond the pale of morality. In other words, if what is to be, shall be, then why worry about consequences? For the proponents of the cultural deviance theory, such an attitude can act as an enabler for delinquency.

6. Autonomy – According to Miller, lower classes may display a contempt towards authority, seeing institutions of the state as exerting undue control over their lives. They may seek to resist such control and assert their autonomy. Delinquency or crime can result as a direct result of this attempt to assert their autonomy against the system, manifesting itself through acts of vandalism or petty crime.

Good to Know Information

The cultural deviance theory is often viewed as a part of a larger theory called the social disorganization theory. Social disorganization theory links crime and delinquency to cultural norms of particular locations or residential areas such as those of low-income groups or those with a heavy concentration of poor immigrants.

However, a key difference between the two is that the cultural deviance theory fleshes out in much greater detail the processes that lead to the formation of a unique delinquent subculture and how this may in turn influence youth towards delinquency.

The social disorganization theory on the other hand stresses on ruptures within systems or breakdown of traditional societal bonds as the reason for delinquency.

Another theory viewed within the same grouping is Sutherland’s (1947) differential association theory . All such theories are further classified together under the broad label of Ecological or Socio-ecological theories that give primacy to the role of the social environment upon human behavioral patterns .

List of Real-Life Examples

1. Ethnic Gangs

Much of the fieldwork that resulted in the formulation of the cultural divergence theory occurred among immigrant street corner gangs in Chicago and Boston in the first half of the twentieth century. Many tenets of the cultural deviance theory are applicable to gangs even in the twenty-first century.

For instance, Indo-Canadian gangs in the Vancouver region of Canada composed of Punjabi Sikh migrants from India draw on cultural values of honour, violence, and revenge coupled with poverty to lure many young boys into joining these gangs. Frederick Thrasher, an early contributor to the cultural deviance theory wrote that “an immigrant colony…is itself an isolated social world…the gang boy moves only in his own universe and other regions are clothed in nebulous mystery…he knows little of the outside world.” (Thrasher 1927)

2. The Chicago Area Project

In 1934, Clifford Shaw, one of the early proponents of the cultural deviance theory, set up the Chicago Area Project in the Russell Square Park neighborhood of South Chicago. This neighborhood was then inhabited by newly arrived immigrants from rural Poland who worked in steel factories and clung tenaciously to their traditional way of life while struggling to cope up with life in an industrialized society.

The Russell Square Park neighborhood had a very high rate of petty crime such as theft and vandalism committed by juveniles who had organized themselves into a number of gangs.

Conventional “top-down” approaches to control delinquency such as punitive policing did not seem to work. So Shaw suggested a “bottom-up” approach based on his theory that the cause of the delinquency was cultural norms that were being adopted and transmitted by the gangs in an environment of deprivation, poverty, and isolation.

Shaw suggested a three-pronged approach to tackle the problems of crime, theft, and vandalism. This included:

- Organizing the community, and

- Providing services to the neighborhood through volunteers.

With these three approaches, Shaw attempted to alter the culture of the gangs and change the perception of gang members about which cultural values were to sought and pursued. The idea was to promote productive values (e.g. getting a job, being a law-abiding citizen), and make others undesirable (e.g. committing acts of vandalism).

3. Honor Killings

Honor killings among immigrants from South Asia and West Asia are a form of violence in which a female, usually a sister or a daughter, is murdered by men of her own family for the perceived act of bringing dishonor to her family. It usually occurs when she is accused of associating with a man outside of her community. Such killings in the West have been documented mostly among newly arrived immigrants working blue collar jobs .

The motivation for such crimes is cultural notions of honor, masculinity, and ethnic/tribal pride coupled with a lack of access to education. Additionally, perpetrators of such acts see their own cultural code as being above the law of the land.

Further, as in Walter Miller’s classic formulation of the cultural deviance theory, notions of toughness in some cultures result in an objectification of women, and in turn, violence against them.

Miller (1958) argued that these supposed cultural traits of the working classes represented the formulation of a unique working-class subculture. This was due primarily to an absence of strong male figures during childhood, and was the cause of high rates of delinquency among lower class youth.

Advantages of Cultural Deviance Theory

1. It’s Comprehensive

The cultural deviance theory combines elements of the social disorganization theory of Shaw and McKay and the strain theory of Robert Merton (1938) to present one of the most comprehensive analyses of delinquency.

While the social disorganization theory focused only on the breakdown of institutions, the strain theory posited a strain or conflict between an individual’s desires and their means as the reasons for crime. While the first misses one crucial step in explaining how disorganization leads to crime, the second focuses too much on individual reasons. The cultural deviance theory combines both.

2. It’s Portable

Although designed initially to examine delinquency in American cities, the cultural deviance theory, with a few tweaks, can be applied to many other cultural settings. The “focal concerns” identified by Miller were specific to the setting of his research but can be adapted to other cultures.

3. It’s Solution-Oriented

Like the routine activities theory of crime , the cultural deviance theory not only claims to explain the causes of delinquency, it also provides a blueprint for solving the problem. Many theoretical models of deviance (such as the conflict theory of deviance ) often remain limited to merely explaining a problem, without providing any actionable insights.

With the cultural deviance theory however, once the “focal concerns” of a culture have been identified, a solution can be devised based on reorienting the cultural norms of delinquents through community intervention, providing services, and community organization.

Criticisms and Disadvantages of Cultural Deviance Theory

1. Stereotyping and Stigmatizing of Lower-class Culture

The classic definition of the cultural deviance theory rests on the delineation of certain “focal concerns” such as toughness, smartness, trouble, etc. that it attributes to a “lower class culture”.

However there is no definitive evidence to support that such attributes are limited only to lower (or working) class cultures. Middle-classes too might identify with such “focal concerns” without having to face the scrutiny of academics and governments trying to ‘fix’ them.

2. Overemphasizing the Impact of Culture

Cultural Deviance Theory relies a little too heavily on the impact of culture on the individual, without accounting for the individual’s own agency in negotiating their way through the structural forces in their lives.

3. Applicable only to Explanations of Certain Kinds of Crimes

The cultural deviance theory can only be used to explain certain classes of crimes such as theft, vandalism, etc. that have a higher rate of prevalence among the working classes. It does not apply to white collar crimes such as fraud, money-laundering etc that are carried out by highly educated individuals or groups of people from the middle or the upper-middle classes who may not belong to working-class and immigrant communities.

Similarly it does not apply to acts of sexual violence that cross class and ethnic barriers. The cultural deviation theory’s assumptions such as a fear of punitive action rather than a sense of morality being the driver of the lower classes fail to hold in such cases as white-collar criminals too show little regard for precepts of morality.

Personally, I find cultural deviance theory creates a ‘deficit’ mindset toward the working-classes and ignores the enormous damage to society caused by the capitalist class. Similarly, it fails to see the positive aspects of the working-classes (such as resilience and their remarkable storytelling traditions).

Nevertheless, this is a sober reflection on the relationship between culture and crime. It remains a worthwhile theoretical lens to examine social problems. But for me, it’s also a learning opportunity to learn how to look critically at a theory and examine its blindspots and biases, of which Cultural Deviance Theory has many.

Reference List

Merton, R. K. (1938). Social structure and anomie . American Sociological Review 3(5), pp. 672-682. Doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/2084686

Miller, W. B. (1958) Lower class culture as a generating milieu of gang culture. Journal of Social Issues 14(3), pp. 5-19. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1958.tb01413.x

Shaw, C. R. and McKay, H.D. (1969). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sutherland, E. (1947) Principles of criminolog y Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins.

Thrasher, F. (1927) The gang: A study of 1313 gangs in Chicago Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kamalpreet Gill Singh (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Ableism Examples

- Kamalpreet Gill Singh (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link The 10 Types of Masculinity

- Kamalpreet Gill Singh (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 31 Most Popular Motivation Theories (A to Z List)

- Kamalpreet Gill Singh (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link Counterfactual Thinking: 10 Examples and Definition

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Role of Cultural Criminology: A Theoretical and Methodological Lineage

This paper addresses the role of cultural criminology as a subfield in academic criminology. Herein, I examine the different ways in which “culture” has been conceptualized in criminology and the relation of those conceptualizations to that of cultural criminology. I go on to trace the main theoretical and methodological approaches that have informed this relatively new subfield of criminological inquiry and briefly discuss some of the perceived limitations of cultural criminology as well as important areas for future inquiry.

Related Papers

Critical Criminology

Dale C. Spencer

Keith Hayward

This books draws together the work of the three leading international figures in cultural criminology today. The book traces the history, current configuration, methodological innovations and future trajectories of cultural criminology, mapping its terrain for students and academics in this exciting field. Praise from Professor Zygmunt Bauman: "This is not just a book on the present state and possible prospects of our understanding of crime, criminals and our responses to both. However greatly the professional criminologists might benefit from the authors' illuminating insights and the new cognitive vistas their investigations have opened, the impact of this book may well stretch far beyond the realm of criminology proper and mark a watershed in the progress of social study as such. This book, after all, brings into the open the irremediable unclarity, endemic contentiousness and the resulting frailty of the line dividing deviance from the norm of social life - that line being simultaneously a weapon and the prime stake in the construction and servicing of social order."

David C Brotherton

This paper sets out to explain to a sociological/criminological audience the theory and practice of what has become known as cultural criminology. The authors have approached this task as a dialog, a conversation, that brings together the critiques and abstractions of the theorist (Jock Young), with his 30-year involvement in the deviance field and the empirical data and experiences of the urban street researcher (David Brotherton) who has spent much of the last 12 years studying and working with gang members. Our aim is to show how this approach to the study of deviance is more appropriate in this period of late modernity than that which currently dominates the field, a positivistic fundamentalism bent on rendering human action into the predictable, the quantifiable, and the mundane.

Nic Groombridge

Symbolic Interaction

Julius Bertašius

Dr Deborah Talbot

Original teaching materials on cultural criminology, looking at its cultural context and application to criminological problems.

A decade has passed since Jock Young and I published 'Cultural criminology: Some notes on the script', the opening article of a special edition on cultural criminology for Theoretical Criminology. This 'sequel' article looks back on developments in the field during the intervening decade as well as responding to some of the criticisms that have emerged in the same period. In particular, it addresses the following critical concerns: that cultural criminology has an inherent romanticism towards its object of study; that it fails to consider or incorporate broader gender dynamics in its analysis; and that cultural criminologists are unable to formulate any meaningful policy measures other than non-interventionism. In responding to these criticisms the article highlights some of the subtle yet important conceptual reconfigurations that have occurred in cultural criminology as it continues to consolidate its position within the discipline. Exposition Over a decade has passed since the late Jock Young and I published 'Cultural criminology: Some notes on the script' (Hayward and Young, 2004), the opening article of a special edition on cultural criminology (CC) for Theoretical Criminology. In that article and as guest editors generally, we had two aims. First, at a practical level, our goal was to introduce

Cultural Criminology Unleashed Edited by Jeff Ferrell, Keith Hayward, Wayne Morrison & Mike Presdee This new title will become the core book on cultural criminology. Cultural Criminology Unleashed brings together cutting edge research across the range of meanings of the term 'cultural' - from anthropology to art, from media analyses to theories of situated meaning. Global in scope, contributions take in the US, UK, Europe, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. A landmark text on the crime-culture nexus, Cultural Criminology Unleashed will be vital reading for academics as well as undergraduate and postgraduate students of criminology/sociology of deviance, penology and criminal justice, as well as cultural studies, media studies, qualitative research methods and sociology. Its editors and authors include the leading exponents of cultural criminology on both sides of the Atlantic. Contents include: Style, Criminology and Phenomenology; ; Biography and the Excavation of Transgression; The Narrative Gratifications of Street Fighting; Visual Methodologies in Cultural Criminology; Marilyn Manson, Colombine, and Cultural Criminology; New Cultural Approaches to Alcohol and Drug Research; Cultural Resistance to the US Patriot Act; Illegal Street racing and the Seduction of Speed: Shifting Underclass Criminal Identities in Late Modernity; The 'Hillbilly Heroin' Moral Panic; The Commodification of Child Sexual Abuse; Celebrity and Criminality; Cultural Criminology, the City and the Spatial Dynamics of Exclusion; Scrounging the Margins of Legality; Crime Talk in Contemporary Urban Japan ; Graffiti Beyond Subculture; Psycho-social Criminology; Immigrant Ethnicity and the Multi-Cultural Administration of Justice ; Cross-cultural Dynamics of Street Gangs; Masculine Fantasy and the Internet; Voodoo Criminology and the Numbers Game. About the Editors: Jeff Ferrell, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Texas Christian University, USA; Keith Hayward, School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent; Wayne Morrison, Director, External Law Programme, University of London; Mike Presdee, School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent. ISBN: 1 90438 531 1

Cyndi Banks

Kenneth Nunn

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Crime Media Culture

Craig Webber

Meg D Lonergan

Richard Staring

Ify Chukwuma

International Annals of Criminology

Masahiro Suzuki

Liam J . Leonard

The Handbook of Criminological Theory

Ekaterina Bochkovar

Crime, Law and Social Change

Susanne Karstedt

Djordje Ignjatović

Cultural Criminology Syllabus (ARTS 140)

Jorge V Castañeda

Chris Cunneen

Cultural criminology unleashed

The American Sociologist

Robert Hauhart

Challenging Criminological Theory: The Legacy of Ruth Kornhauser edited by Frank Cullen, Pamela Wilcox, Robert Sampson and Brendan Dooley

Charis Kubrin

Theoretical Criminology

David W Garland

Bill Hebenton

Kevin Whiteacre

Scott Lukas , Stuart Henry

University Essays

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

7.3 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime

Sociologists have tried to understand why people engage in deviance or crime by developing theories to help explain this behavior. It is important to note that these theories focus primarily on why people engage in crime, why some behaviors are defined as criminal while others aren’t, and how people learn criminal behavior rather than on deviance more broadly. The focus of these theories reflects that society is much more concerned about crime than people who break other kinds of social or cultural norms.

7.3.1 Historical Theories of Deviance

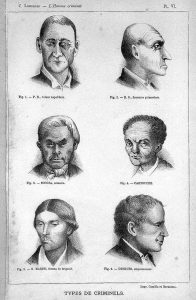

Inspired by Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species , early scholars trying to explain crime turned to the concept of evolution to understand differences among humans by claiming physical features were identifying markers of criminals. Several characteristics were said to indicate criminality, including skull shape, size, body type, and facial features. For example, Cesare Lombroso (1911), the father of positivist criminology, claimed that criminals were evolutionary throwbacks. He claimed that criminals can be identified by their abnormal apelike facial and physical features. A visual depiction of these features can be seen below in figure 7.4 .This school of thought is closely associated with the eugenics movement, discussed more in-depth in Chapter 11 . These theories were quickly disproven and have received harsh critiques for their blatantly racist foundation.

7.3.1.1 Durkheim and Functionalism

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society. One way deviance is functional, he argued, is that it challenges people’s present views (1893). For instance, Colin Kaepernick taking a knee during the national anthem to protest police violence challenged people’s ideas about racial inequality in the United States. Moreover, Durkheim noted, when deviance is punished, it reaffirms currently held social norms, which also contributes to society (1960[1893]). Seeing a student given detention for skipping class reminds other high schoolers that playing hooky isn’t allowed and that they, too, could get detention.

Durkheim’s point regarding the impact of punishing deviance speaks to his arguments about law. Durkheim saw laws as an expression of the collective conscience, which are the beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society. He discussed the impact of societal size and complexity as contributors to the collective conscience and the development of justice systems and punishments. In large, industrialized societies that were largely bound together by the interdependence of work (the division of labor), punishments for deviance were generally less severe. In smaller, more homogeneous societies, deviance might be punished more severely.

Modern theories have a few significant critiques of Durkheim’s perspective on crime. Sociologists have critiqued Durkheim’s argument that deviance is functional for not being generalizable to all crimes. For instance, it can be hard to argue that murder is functional for society solely because it reaffirms currently held social norms. Moreover, the idea that law is an expression of collective consciousness has also been critiqued. Conflict theorists argue that the bourgeois or elite have significant influence over political and legal institutions, allowing them to pass laws that benefit their interests and avoid harsh punishments when they commit crimes. This challenges the idea that the law reflects what society thinks is just or right.

7.3.1.2 Social Disorganization Theory

Developed by researchers at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, social disorganization theory asserts that crime is most likely to occur in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control.

Some research supports this theory. Even today, crimes like theft or murder are more likely to occur in low-income neighborhoods with many social problems. Still, a critique of this research is that many of these studies rely on official crime rates, much of which reflect police surveillance rather than actual crime rates. For this reason, social disorganization theory does not adequately explain white collar crimes committed by individuals living in wealthy neighborhoods, such as financial fraud or insider trading. Similarly, research from a social disorganization theory often uses circular logic: an area with a high crime rate is assumed to signal a disorganized neighborhood, leading to a high crime rate (Bursik 1988).

7.3.1.3 Cultural Deviance Theory

Cultural deviance theory suggests that conformity to the prevailing cultural norms of lower-class society causes crime. Researchers Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay (1942) studied crime patterns in Chicago in the early 1900s. They found that violence and crime were at their worst in the middle of the city and gradually decreased the farther someone traveled from the urban center toward the suburbs. Shaw and McKay noticed that this pattern matched the migration patterns of Chicago citizens. As the urban population expanded, wealthier people moved to the suburbs and left behind the less privileged. Shaw and McKay concluded that socioeconomic status correlated to race and ethnicity resulted in a higher crime rate.

This theory has many similar critiques to social disorganization theory, as they were developed around the same time and strongly emphasize the role of the environment on crime and deviance. One other critique of cultural deviance theory is that while it attributes crime to lower class cultures and values, there is no substantial evidence that these attitudes are limited to people in this class.

7.3.2 Modern Theories of Deviance

In response to the historical theories of deviance, new theories emerged that critiqued or expanded upon them to address shortfalls in their explanations. At the end of this section, figure 7.6 summarizes these key theories.

7.3.2.1 Robert Merton’s Strain Theory: Rethinking Durkheim

Sociologist Robert Merton agreed that deviance is an inherent part of a functioning society, but he expanded on Durkheim’s ideas by developing strain theory , which notes that access to socially acceptable goals plays a part in determining whether a person conforms or deviates. Merton defined five ways people respond to this gap between having a socially accepted goal and having no socially accepted way to pursue it. To understand the five ways people respond, we’ll look at the example of the American Dream: the idea that to be successful, you should own a house, car, and have a happy and functional family.

Example: “I may not be able to afford to buy a house in my lifetime, but I have a working car, a loving partner, and a cute dog. I’m content with the lot I’ve been given in life.”

Example: “I grew up in a neighborhood that didn’t have good schools, and I never had an opportunity to get ahead. I want a house, nice car, and to take care of my family, but the only way I can see myself doing that is by continuing to sell cocaine and counterfeit goods.”

Example: “I’m never going to be able to afford a nice home and car, but I don’t need those things anyways! I like the apartment I rent, and my cat’s only other form of life I want to be responsible for. Why not just love the things that I do have?”

Example: “ Why would I even participate in society at all? The deck is stacked against me. I know I’m only 20, but (illegally) hopping on trains and travelling around the country with my friends is where it’s at! ”

Example: “I’m gonna overthrow the government, that’s what I’m going to do! The system is unjust and it’s not one that’s designed for how humans really are!”

7.3.2.2 William Julius Wilson: Rethinking the Role of Neighborhoods

William Julius Wilson refined ideas in social disorganization theory to explain why people in poverty, particularly those living in black and immigrant communities, are more likely to live in high-crime neighborhoods. Rather than focusing on the role of cultural factors like previous theorists, Wilson (1987) focused on how economic changes have contributed to these groups being more likely to live in high-crime neighborhoods.

Wilson (1997) argued that before the decline of industrial and manufacturing jobs, these groups could be economically successful despite having low levels of education given their access to high paying factory jobs. After manufacturing jobs left these cities, black people and recent immigrants became trapped in low-income high-crime areas with few jobs or low-wage, service sector jobs. According to Wilson’s (1997) theory, crime emerges because policy leads to little economic opportunity and traps disadvantaged groups in poor, high-crime areas where turning to crime is one of the few opportunities for advancement.

7.3.2.3 Karl Marx’s Unequal System Theory

Karl Marx believed that the bourgeoisie centralized their power and influence through government and law. Though Marx spoke little of deviance, his ideas created the foundation for other theorists who study the intersection of deviance and crime with wealth and power. Later Marxists, such as Richard Quinney (1974), expanded upon these ideas. He believed that the bourgeoisie set up laws to maintain their class rankings rather than to reduce crime. Similarly, he argued that the legal system is uninterested in addressing the root causes of crime. Instead, the legal system is preoccupied with controlling the lower class.

7.3.2.4 C. Wright Mills’ Power Elite Theory

Power Elite theory differs from unequal system theory in that it further refines the ideas of unequal system theory. It more clearly specifies which actors influence laws, rather than broadly characterizing the bourgeois as having this power. Still, many similarities exist between the two theories in that they both look at how the groups in power exploit their influence for their benefit at the expense of marginalized populations.

In his book The Power Elite (1956), sociologist C. Wright Mills described the existence of what he dubbed the power elite, a small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who hold the power and resources. Wealthy executives, politicians, celebrities, and military leaders often have access to national and international power, and in some cases, their decisions affect everyone in society. Because of this, the rules of society are stacked in favor of a privileged few who manipulate them to stay on top. It is these people who decide what is criminal and what is not, and the effects are often felt most by those who have little power.

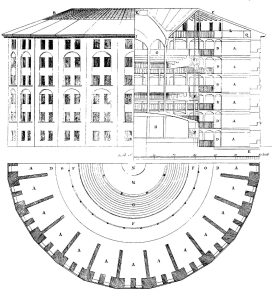

7.3.2.5 Michele Foucault: Discipline and Punishment Theory

The panopticon, as seen below in figure 7.5, is a late eighteenth century circular prison designed by philosopher Jeremy Bentham. In the panopticon prison design, guards could continuously monitor prisoners without the prisoners knowing if guards were watching. Since prisoners would not know when guards were watching them, they would constantly surveil their behavior to avoid punishment. French philosopher Michele Foucault (1977) drew parallels between Jeremy Benthan’s panopticon and how modern institutions control the population. He argued that punishment currently occurs through discipline and surveillance by institutions, such as prisons, mental hospitals, schools, and workplaces. These institutions produce compliant citizens without the threat of violence.

Ultimately, Foucault (1977) argued that surveillance created an effect where individuals conformed to society since they never knew if they were being watched. His ideas have gained new importance with the rise of surveillance technologies, which make it harder to engage in deviance without getting caught. Examples of this phenomenon are federal mass surveillance policies and the rise of police departments using technologies to scour social media networks for information about criminal activities. Broadly, Foucault (1977) proposed that social control and punishment are not just formal sanctions, like a prison sentence or ticket, but also something more mundane and built into social institutions.

7.3.2.6 Lemert’s Labeling Theory

Rooted in symbolic interactionism, labeling theory examines the ascribing of a deviant behavior to another person by members of society. What is considered deviant is determined not so much by the behaviors themselves or the people who commit them, but by the reactions of others to these behaviors. As a result, what is considered deviant changes over time and can vary significantly across cultures.

Sociologist Edwin Lemert expanded on the concepts of labeling theory and identified two types of deviance that affect identity formation. Primary deviance is a violation of norms that does not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others. Speeding is a deviant act, but receiving a speeding ticket generally does not make others view you as a bad person, nor does it alter your own self-concept. Individuals who engage in primary deviance still maintain a feeling of belonging in society and are likely to continue to conform to norms in the future.

Sometimes, in more extreme cases, primary deviance can morph into secondary deviance . In secondary deviance a person may begin to take on and fulfill the role of a “deviant” as an act of rebellion against the society that has labeled that individual as such. In many ways, secondary deviance is captured by the phrase, “If you tell a child enough that they’re a bad kid, they’ll eventually believe that they’re a bad kid.” This perspective hits on how negative social labels, especially of juveniles, have the power to create more deviant or criminal behavior.

7.3.2.7 Sykes and Matza’s Techniques of Neutralization

How do people deal with the labels they are given? This was the subject of a study done by Gresham Sykes and David Matza (1957). They studied teenage boys who had been labeled as juvenile delinquents to see how they either embraced or denied these labels. They argued that criminals don’t have vastly different cultural values but rather adopt attitudes to justify criminal behavior at times. Sykes and Matza developed five techniques of neutralization to capture how people justify engaging in criminal acts. Individuals may not necessarily internalize labels if they have developed strategies to reject associating their actions with these labels.

Let’s apply each of these techniques by pretending to be a teenager justifying shoplifting at a major retail chain department store. From this example, we can see how individuals can justify engaging in an act that may be illegal and violates social norms through these kinds of cognitive strategies

Example: “I don’t want to steal from this store, but I’ve applied to so many jobs and no one seems to want to hire a teenager these days.”

Example: “It’s not like anyone is being hurt by me stealing.”

Example: “Who am I hurting anyways? This is a big corporation! They expect some level of theft.”

Example: “This corporation is way more corrupt considering the fact most of their goods come from sweatshops where there is child labor.

Example: “I’m only stealing because I really don’t have enough money to get my sister a nice birthday present and she matters way more to me than any stupid corporation does. I’m a modern day Robin Hood.”

7.3.2.8 Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory

In the early 1900s, sociologist Edwin Sutherland sought to understand how deviant behavior developed among people. Since criminology was a young field, he drew on other aspects of sociology including social interactions and group learning (Laub 2006) and the work of George Herbert Mead, whose ideas are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4 . His conclusions established differential association theory , which suggested that individuals learn deviant behavior from those close to them who provide models of and opportunities for deviance.

According to Sutherland, deviance is less a personal choice and more a result of differential socialization processes. He argues that people learn all aspects of criminal behavior through interacting with others and being part of intimate personal groups. Sutherland’s theory captures not only how people learn criminal behavior, but also how people learn motives, rationalizations, and attitudes towards crime. Differential association theory also demystifies crime, conceptualizing it as a behavior just like any other: a radical departure from early theories of crime that viewed criminals as inherently biologically different or all individuals as naturally pleasure seeking, selfish, and prone to crime. In Sutherland’s theory, anyone has the potential to engage in crime if they learn how to commit crime and embrace favorable definitions of crime. This theory also helps explain why not all children who grow up in poverty end up engaging in criminal activity—as historical theories such as cultural deviance theory suggest—because they encounter different situations that shape their definitions towards violating the law.

| Theory | Associated Theorist | Contribution to the Study of Deviance and Crime |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Association Theory | Edwin Sutherland | Argues that deviance arises from learning and modeling deviant behavior seen in other people close to the individual |

| Discipline and Punishment Theory | Michel Foucault | Highlights how social control mechanisms are not just formal sanctions, but also built into modern institutions |

| Labeling Theory | Edwin Lemert | Argues that deviance arises from the reactions of others, particularly those in power who are able to determine labels |

| Power Elite Theory | C. Wright Mills | Argues that deviance arises from the ability of those in power to define deviance in ways that maintain the status quo |

| Revised Social Disorganization Theory | William Julius Wilson | Argues that crime emerges because policy leads to little economic opportunity and traps disadvantaged groups in poor, high crime areas where turning to crime is one of the few opportunities for advancement |

| Strain Theory | Robert Merton | Argues that deviance arises from a lack of ways to reach socially accepted goals by accepted methods |

| Techniques of Neutralization | Gresham Sykes and David Matza | Developed five techniques of neutralization to capture how people justify engaging in criminal acts |

| Unequal System Theory | Karl Marx | Argues that deviance arises from inequalities in wealth and power that arise from the economic system |

Figure 7.6. Modern Theories of Deviance and Crime

7.3.3 Licenses and Attributions for Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime

“Durkheim and Functionalism” paragraphs 1 and 2 edited for clarity and brevity are from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Social Disorganization Theory” paragraph 1 edited for clarity and brevity is from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Cultural Deviance Theory” paragraph 1 is from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance” by Heather Griffiths and Nathan Keirns in Openstax Sociology 2e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance

“Robert Merton’s Strain Theory: Rethinking Durkheim” modified from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Karl Marx’s Unequal System Theory” modified from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“C. Wright Mills’ Power Elite Theory” paragraph two edited for clarity and brevity from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Lemert’s Labeling Theory” paragraphs 1 and 2, and sentences 1 and 2 in paragraph 3 edited for clarity and brevity from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory” modified from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

Figure 7.4. Plate 6 of L’Homme Criminel by Cesar Lombroso, Public domain , via the Wellcome Collection .

Figure 7.5. Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon Prison Design, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons .

Figure 7.6 is from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime . Substantial modifications and additions have been made.

All other content in this section is original content by Alexandra Olsen and licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Sociology in Everyday Life Copyright © by Matt Gougherty and Jennifer Puentes. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 7. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control

Learning objectives.

7.1. Deviance and Control

- Define deviance and categorize different types of deviant behaviour

- Determine why certain behaviours are defined as deviant while others are not

- Differentiate between methods of social control

- Describe the characteristics of disciplinary social control and their relationship to normalizing societies

7.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance

- Describe the functionalist view of deviance in society and compare Durkheim’s views with social disorganization theory, control theory, and strain theory

- Explain how critical sociology understands deviance and crime in society

- Understand feminist theory’s unique contributions to the critical perspective on crime and deviance

- Describe the symbolic interactionist approach to deviance, including labelling and other theories

7.3. Crime and the Law

- Identify and differentiate between different types of crimes

- Evaluate Canadian crime statistics

- Understand the nature of the corrections system in Canada

Introduction to Deviance, Crime, and Social Control

Psychopaths and sociopaths are some of the favourite “deviants” in contemporary popular culture. From Patrick Bateman in American Psycho , to Dr. Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs , to Dexter Morgan in Dexter , to Sherlock Holmes in Sherlock and Elementary , the figure of the dangerous individual who lives among us provides a fascinating fictional figure. Psychopathy and sociopathy both refer to personality disorders that involve anti-social behaviour, diminished empathy, and lack of inhibitions. In clinical analysis, these analytical categories should be distinguished from psychosis , which is a condition involving a debilitating break with reality.

Psychopaths and sociopaths are often able to manage their condition and pass as “normal” citizens, although their capacity for manipulation and cruelty can have devastating consequences for people around them. The term psychopathy is often used to emphasize that the source of the disorder is internal, based on psychological, biological, or genetic factors, whereas sociopathy is used to emphasize predominant social factors in the disorder: the social or familial sources of its development and the inability to be social or abide by societal rules (Hare 1999). In this sense sociopathy would be the sociological disease par excellence. It entails an incapacity for companionship ( socius ), yet many accounts of sociopaths describe them as being charming, attractively confident, and outgoing (Hare 1999).

In a modern society characterized by the predominance of secondary rather than primary relationships, the sociopath or psychopath functions, in popular culture at least, as a prime index of contemporary social unease. The sociopath is like the nice neighbour next door who one day “goes off” or is revealed to have had a sinister second life. In many ways the sociopath is a cypher for many of the anxieties we have about the loss of community and living among people we do not know. In this sense, the sociopath is a very modern sort of deviant. Contemporary approaches to psychopathy and sociopathy have focused on biological and genetic causes. This is a tradition that goes back to 19th century positivist approaches to deviance, which attempted to find a biological cause for criminality and other types of deviant behaviour.

The Italian professor of legal psychiatry Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) was a key figure in positivist criminology who thought he had isolated specific physiological characteristics of “degeneracy” that could distinguish “born criminals” from normal individuals (Rimke 2011). In a much more sophisticated way, this was also the premise of Dr. James Fallon, a neuroscientist at the University of California. His research involved analyzing brain scans of serial killers. He found that areas of the frontal and temporal lobes associated with empathy, morality, and self-control are “shut off” in serial killers. In turn, this lack of brain activity has been linked with specific genetic markers suggesting that psychopathy or sociopathy was passed down genetically. Fallon’s premise was that psychopathy is genetically determined. An individual’s genes determine whether they are psychopathic or not (Fallon 2013).

However, at the same time that he was conducting research on psychopaths, he was studying the brain scans of Alzheimer’s patients. In the Alzheimer’s study, he discovered a brain scan from a control subject that indicated the symptoms of psychopathy he had seen in the brain scans of serial killers. The scan was taken from a member of his own family. He broke the seal that protected the identity of the subject and discovered it was his own brain scan.

Fallon was a successfully married man, who had raised children and held down a demanding career as a successful scientist and yet the brain scan indicated he was a psychopath. When he researched his own genetic history, he realized that his family tree contained seven alleged murderers including the famous Lizzie Borden, who allegedly killed her father and stepmother in 1892. He began to notice some of his own behaviour patterns as being manipulative, obnoxiously competitive, egocentric, and aggressive, just not in a criminal manner.He decided that he was a “pro-social psychopath”—an individual who lacks true empathy for others but keeps his or her behaviour within acceptable social norms—due to the loving and nurturing family he grew up in. He had to acknowledge that environment, and not just genes, played a significant role in the expression of genetic tendencies (Fallon 2013).

What can we learn from Fallon’s example from a sociological point of view? Firstly, psychopathy and sociopathy are recognized as problematic forms of deviance because of prevalent social anxieties about serial killers as types of criminal who “live next door” or blend in. This is partly because we live in a type of society where we do not know our neighbours well and partly because we are concerned to discover their identifiable traits as these are otherwise concealed. Secondly, Fallon acknowledges that there is no purely biological or genetic explanation for psychopathy and sociopathy.

Many individuals with the biological and genetic markers of psychopathy are not dangers to society—key to pathological expressions of psychopathy are elements of an individual’s social environment and social upbringing (i.e., nurture). Finally, in Fallon’s own account, it is difficult to separate the discovery of the aberrant brain scan and the discovery and acknowledgement of his personal traits of psychopathy. Is it clear which came first? He only recognizes the psychopatholoy in himself after seeing the brain scan. This is the problem of what Ian Hacking (2006) calls the “looping effect” that affects the sociological study of deviance (see discussion below). In summary, what Fallon’s example illustrates is the complexity of the study of social deviance.

7.1. Deviance and Control

What, exactly, is deviance? And what is the relationship between deviance and crime? According to sociologist William Graham Sumner, deviance is a violation of established contextual, cultural, or social norms, whether folkways, mores, or codified law (1906). Folkways are norms based on everyday cultural customs concerning practical matters like how to hold a fork, what type of clothes are appropriate for different situations, or how to greet someone politely. Mores are more serious moral injunctions or taboos that are broadly recognized in a society, like the incest taboo. Codified laws are norms that are specified in explicit codes and enforced by government bodies. A crime is therefore an act of deviance that breaks not only a norm, but a law. Deviance can be as minor as picking one’s nose in public or as major as committing murder.

John Hagen (1994) provides a typology to classify deviant acts in terms of their perceived harmfulness, the degree of consensus concerning the norms violated, and the severity of the response to them. The most serious acts of deviance are consensus crimes about which there is near-unanimous public agreement. Acts like murder and sexual assault are generally regarded as morally intolerable, injurious, and subject to harsh penalties. Conflict crimes are acts like prostitution or smoking marijuana, which may be illegal but about which there is considerable public disagreement concerning their seriousness. Social deviations are acts like abusing serving staff or behaviours arising from mental illness and addiction, which are not illegal in themselves but are widely regarded as serious or harmful. People agree that they call for institutional intervention. Finally there are social diversions like riding skateboards on sidewalks, overly tight leggings, or facial piercings that violate norms in a provocative way but are generally regarded as distasteful but harmless, or for some, cool.

The point is that the question, “What is deviant behaviour?” cannot be answered in a straightforward manner. This follows from two key insights of the sociological approach to deviance (which distinguish it from moral and legalistic approaches). Firstly, deviance is defined by its social context. To understand why some acts are deviant and some are not, it is necessary to understand what the context is, what the existing rules are, and how these rules came to be established. If the rules change, what counts as deviant also changes. As rules and norms vary across cultures and time, it makes sense that notions of deviance also change.

Fifty years ago, public schools in Canada had strict dress codes that, among other stipulations, often banned women from wearing pants to class. Today, it is socially acceptable for women to wear pants, but less so for men to wear skirts. In a time of war, acts usually considered morally reprehensible, such as taking the life of another, may actually be rewarded. Much of the confusion and ambiguity regarding the use of violence in hockey has to do with the different sets of rules that apply inside and outside the arena. Acts that are acceptable and even encouraged on the ice would be punished with jail time if they occurred on the street.

Whether an act is deviant or not depends on society’s definition of that act. Acts are not deviant in themselves. The second sociological insight is that deviance is not an intrinsic (biological or psychological) attribute of individuals, nor of the acts themselves, but a product of social processes . The norms themselves, or the social contexts that determine which acts are deviant or not, are continually defined and redefined through ongoing social processes—political, legal, cultural, etc. One way in which certain activities or people come to be understood and defined as deviant is through the intervention of moral entrepreneurs.

Becker (1963) defined moral entrepreneurs as individuals or groups who, in the service of their own interests, publicize and problematize “wrongdoing” and have the power to create and enforce rules to penalize wrongdoing. Judge Emily Murphy, commonly known today as one of the “Famous Five” feminist suffragists who fought to have women legally recognized as “persons” (and thereby qualified to hold a position in the Canadian Senate), was a moral entrepreneur instrumental in changing Canada’s drug laws. In 1922 she wrote The Black Candle , in which she demonized the use of marijuana:

[Marijuana] has the effect of driving the [user] completely insane. The addict loses all sense of moral responsibility. Addicts to this drug, while under its influence, are immune to pain, and could be severely injured without having any realization of their condition. While in this condition they become raving maniacs and are liable to kill or indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods of cruelty without, as said before, any sense of moral responsibility…. They are dispossessed of their natural and normal will power, and their mentality is that of idiots. If this drug is indulged in to any great extent, it ends in the untimely death of its addict (Murphy 1922).

One of the tactics used by moral entrepreneurs is to create a moral panic about activities, like marijuana use, that they deem deviant. A moral panic occurs when media-fuelled public fear and overreaction lead authorities to label and repress deviants, which in turn creates a cycle in which more acts of deviance are discovered, more fear is generated, and more suppression enacted. The key insight is that individuals’ deviant status is ascribed to them through social processes. Individuals are not born deviant, but become deviant through their interaction with reference groups, institutions, and authorities.

Through social interaction, individuals are labelled deviant or come to recognize themselves as deviant. For example, in ancient Greece, homosexual relationships between older men and young acolytes were a normal component of the teacher-student relationship. Up until the 19th century, the question of who slept with whom was a matter of indifference to the law or customs, except where it related to family alliances through marriage and the transfer of property through inheritance. However, in the 19th century sexuality became a matter of moral, legal, and psychological concern. The homosexual, or “sexual invert,” was defined by the emerging psychiatric and biological disciplines as a psychological deviant whose instincts were contrary to nature.

Homosexuality was defined as not simply a matter of sexual desire or the act of sex, but as a dangerous quality that defined the entire personality and moral being of an individual (Foucault 1980). From that point until the late 1960s, homosexuality was regarded as a deviant, closeted activity that, if exposed, could result in legal prosecution, moral condemnation, ostracism, violent assault, and loss of career. Since then, the gay rights movement and constitutional protections of civil liberties have reversed many of the attitudes and legal structures that led to the prosecution of gays, lesbians, and transgendered people. The point is that to whatever degree homosexuality has a natural or inborn biological cause, its deviance is the outcome of a social process.

It is not simply a matter of the events that lead authorities to define an activity or category of persons deviant, but of the processes by which individuals come to recognize themselves as deviant. In the process of socialization, there is a “looping effect” (Hacking 2006). Once a category of deviance has been established and applied to a person, that person begins to define himself or herself in terms of this category and behave accordingly. This influence makes it difficult to define criminals as kinds of person in terms of pre-existing, innate predispositions or individual psychopathologies. As we will see later in the chapter, it is a central tenet of symbolic interactionist labelling theory , that individuals become criminalized through contact with the criminal justice system (Becker 1963). When we add to this insight the sociological research into the social characteristics of those who have been arrested or processed by the criminal justice system —variables such as gender, age, race, and class— it is evident that social variables and power structures are key to understanding who chooses a criminal career path.

One of the principle outcomes of these two sociological insights is that a focus on the social construction of different social experiences and problems leads to alternative ways of understanding them and responding to them. In the study of crime and deviance, the sociologist often confronts a legacy of entrenched beliefs concerning either the innate biological disposition or the individual psychopathology of persons considered abnormal: the criminal personality, the sexual or gender “deviant,” the disabled or ill person, the addict, or the mentally unstable individual. However, as Ian Hacking observes, even when these beliefs about kinds of persons are products of objective scientific classification, the institutional context of science and expert knowledge is not independent of societal norms, beliefs, and practices (2006).

The process of classifying kinds of people is a social process that Hacking calls “making up people” and Howard Becker calls “labelling” (1963). Crime and deviance are social constructs that vary according to the definitions of crime, the forms and effectiveness of policing, the social characteristics of criminals, and the relations of power that structure society. Part of the problem of deviance is that the social process of labelling some kinds of persons or activities as abnormal or deviant limits the type of social responses available. The major issue is not that labels are arbitrary or that it is possible not to use labels at all, but that the choice of label has consequences. Who gets labelled by whom and the way social labels are applied have powerful social repercussions.

Making Connections: Careers in Sociology

Why i drive a hearse.

When Neil Young left Canada in 1966 to seek his fortune in California as a musician, he was driving his famous 1953 Pontiac hearse “Mort 2.” He and Bruce Palmer were driving the hearse in Hollywood when they happened to see Stephen Stills and Richie Furray driving the other way, a fortuitous encounter that led to the formation of the band Buffalo Springfield (McDonough 2002). Later Young wrote “Long May You Run” as an elegy to his first hearse “Mort,” which he performed at the closing ceremonies of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Rock musicians are often noted for their eccentricities, but is driving a hearse deviant behaviour? When sociologist Todd Schoepflin ran into his childhood friend Bill who drove a hearse, he wondered what effect driving a hearse had on his friend and what effect it might have on others on the road. Would using such a vehicle for everyday errands be considered deviant by most people? Schoepflin interviewed Bill, curious first to know why he drove such an unconventional car. Bill had simply been on the lookout for a reliable winter car; on a tight budget, he searched used car ads and stumbled on one for the hearse. The car ran well and the price was right, so he bought it. Bill admitted that others’ reactions to the car had been mixed. His parents were appalled and he received odd stares from his coworkers. A mechanic once refused to work on it, stating that it was “a dead person machine.” On the whole, however, Bill received mostly positive reactions. Strangers gave him a thumbs-up on the highway and stopped him in parking lots to chat about his car. His girlfriend loved it, his friends wanted to take it tailgating, and people offered to buy it. Could it be that driving a hearse isn’t really so deviant after all? Schoepflin theorized that, although viewed as outside conventional norms, driving a hearse is such a mild form of deviance that it actually becomes a mark of distinction. Conformists find the choice of vehicle intriguing or appealing, while nonconformists see a fellow oddball to whom they can relate. As one of Bill’s friends remarked, “Every guy wants to own a unique car like this and you can certainly pull it off.” Such anecdotes remind us that although deviance is often viewed as a violation of norms, it’s not always viewed in a negative light (Schoepflin 2011).

Social Control

When a person violates a social norm, what happens? A driver caught speeding can receive a speeding ticket. A student who texts in class gets a warning from a professor. An adult belching loudly is avoided. All societies practise social control , the regulation and enforcement of norms. Social control can be defined broadly as an organized action intended to change people’s behaviour (Innes 2003). The underlying goal of social control is to maintain social order , an arrangement of practices and behaviours on which society’s members base their daily lives. Think of social order as an employee handbook and social control as the incentives and disincentives used to encourage or oblige employees to follow those rules. When a worker violates a workplace guideline, the manager steps in to enforce the rules. One means of enforcing rules are through sanctions . Sanctions can be positive as well as negative. Positive sanctions are rewards given for conforming to norms. A promotion at work is a positive sanction for working hard. Negative sanctions are punishments for violating norms. Being arrested is a punishment for shoplifting. Both types of sanctions play a role in social control.

Sociologists also classify sanctions as formal or informal. Although shoplifting, a form of social deviance, may be illegal, there are no laws dictating the proper way to scratch one’s nose. That doesn’t mean picking your nose in public won’t be punished; instead, you will encounter informal sanctions . Informal sanctions emerge in face-to-face social interactions. For example, wearing flip-flops to an opera or swearing loudly in church may draw disapproving looks or even verbal reprimands, whereas behaviour that is seen as positive—such as helping an old man carry grocery bags across the street—may receive positive informal reactions, such as a smile or pat on the back.

Formal sanctions , on the other hand, are ways to officially recognize and enforce norm violations. If a student plagiarizes the work of others or cheats on an exam, for example, he or she might be expelled. Someone who speaks inappropriately to the boss could be fired. Someone who commits a crime may be arrested or imprisoned. On the positive side, a soldier who saves a life may receive an official commendation, or a CEO might receive a bonus for increasing the profits of his or her corporation. Not all forms of social control are adequately understood through the use of sanctions, however. Black (1976) identifies four key styles of social control, each of which defines deviance and the appropriate response to it in a different manner. Penal social control functions by prohibiting certain social behaviours and responding to violations with punishment. Compensatory social control obliges an offender to pay a victim to compensate for a harm committed. Therapeutic social control involves the use of therapy to return individuals to a normal state. Conciliatory social control aims to reconcile the parties of a dispute and mutually restore harmony to a social relationship that has been damaged. While penal and compensatory social controls emphasize the use of sanctions, therapeutic and conciliatory social controls emphasize processes of restoration and healing.

Social Control as Government and Discipline

Michel Foucault notes that from a period of early modernity onward, European society became increasingly concerned with social control as a practice of government (Foucault 2007). In this sense of the term, government does not simply refer to the activities of the state, but to all the practices by which individuals or organizations seek to govern the behaviour of others or themselves. Government refers to the strategies by which one seeks to direct or guide the conduct of another or others. In the 15th and 16th centuries, numerous treatises were written on how to govern and educate children, how to govern the poor and beggars, how to govern a family or an estate, how to govern an army or a city, how to govern a state and run an economy, and how to govern one’s own conscience and conduct. These treatises described the burgeoning arts of government, which defined the different ways in which the conduct of individuals or groups might be directed. Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince (1532), which offers advice to the prince on how best to conduct his relationship with his subjects, is the most famous of these treatises.

The common theme in the various arts of governing proposed in early modernity was the extension of Christian monastic practices involving the detailed and continuous government and salvation of souls. The principles of monastic government were applied to a variety of non-monastic areas. People needed to be governed in all aspects of their lives. It was not, however, until the 19th century and the invention of modern institutions like the prison, the public school, the modern army, the asylum, the hospital, and the factory, that the means for extending government and social control widely through the population were developed.

Foucault (1979) describes these modern forms of government as disciplinary social control because they each rely on the detailed continuous training, control, and observation of individuals to improve their capabilities: to transform criminals into law abiding citizens, children into educated and productive adults, recruits into disciplined soldiers, patients into healthy people, etc. Foucault argues that the ideal of discipline as a means of social control is to render individuals docile. That does not mean that they become passive or sheep-like, but that disciplinary training simultaneously increases their abilities, skills, and usefulness while making them more compliant and manipulable.

The chief components of disciplinary social control in modern institutions like the prison and the school are surveillance, normalization, and examination (Foucault 1979). Surveillance refers to the various means used to make the lives and activities of individuals visible to authorities. In 1791, Jeremy Bentham published his book on the ideal prison, the panopticon or “seeing machine.” Prisoners’ cells would be arranged in a circle around a central observation tower where they could be both separated from each other and continually exposed to the view of prison guards. In this way, Bentham proposed, social control could become automatic because prisoners would be induced to monitor their own behaviour.

Similarly, in a school classroom, students sit in rows of desks immediately visible to the teacher at the front of the room. In a store, shoppers can be observed through one-way glass or video monitors. Contemporary surveillance expands the capacity for observation using video or electronic forms of surveillance to render the activities of a population visible. London, England, holds the dubious honour of being the most surveilled city in the world. The city’s “ring of steel” is a security cordon in which over half a million surveillance cameras are used to monitor and record traffic moving in and out of the city centre.

The practice of normalization refers to the way in which norms, such as the level of math ability expected from a grade 2 student, are first established and then used to assess, differentiate, and rank individuals according to their abilities (an A student, B student, C student, etc.). Individuals’ progress in developing their abilities, whether in math skills, good prison behaviour, health outcomes, or other areas, is established through constant comparisons with others and with natural and observable norms. Minor sanctions are used to continuously modify behaviour that does not comply with correct conduct: rewards are applied for good behaviour and penalties for bad.

Periodic examinations through the use of tests in schools, medical examinations in hospitals, inspections in prisons, year-end reviews in the workplace, etc. bring together surveillance and normalization in a way that enables each individual and each individual’s abilities to be assessed, documented, and known by authorities. On the basis of examinations, individuals can be subjected to different disciplinary procedures more suited to them. Gifted children might receive an enriched educational program, whereas poorer students might receive remedial lessons.

Foucault describes disciplinary social control as a key mechanism in creating a normalizing society . The establishment of norms and the development of disciplinary procedures to correct deviance from norms become increasingly central to the organization and operation of institutions from the 19th century onward. To the degree that “natural” or sociological norms are used to govern our lives more than laws and legal mechanisms, society can be said to be controlled through normalization and disciplinary procedures. Whereas the use of formal laws, courts , and the police come into play only when laws are broken, disciplinary techniques enable the continuous and ongoing social control of an expanding range of activities in our lives through surveillance, normalization, and examination. While we may never encounter the police for breaking a law, if we work, go to school, or end up in hospital, we are routinely subject to disciplinary control through most of the day.

7.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance

Why does deviance occur? How does it affect a society? Since the early days of sociology, scholars have developed theories attempting to explain what deviance and crime mean to society. These theories can be grouped according to the three major sociological paradigms: functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and conflict theory.

Functionalism

Sociologists who follow the functionalist approach are concerned with how the different elements of a society contribute to the whole. They view deviance as a key component of a functioning society. Social disorganization theory, strain theory, and cultural deviance theory represent three functionalist perspectives on deviance in society.

Émile Durkheim: The Essential Nature of Deviance

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society. One way deviance is functional, he argued, is that it challenges people’s present views (1893). For instance, when black students across the United States participated in “sit-ins” during the civil rights movement, they challenged society’s notions of segregation. Moreover, Durkheim noted, when deviance is punished, it reaffirms currently held social norms, which also contributes to society (1893). Seeing a student given a detention for skipping class reminds other high schoolers that playing hooky isn’t allowed and that they, too, could get a detention.

Social Disorganization Theory

Developed by researchers at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, social disorganization theory asserts that crime is most likely to occur in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control. In a certain way, this is the opposite of Durkheim’s thesis. Rather than deviance being a force that reinforces moral and social solidarity, it is the absence of moral and social solidarity that provides the conditions for social deviance to emerge.

Early Chicago School sociologists used an ecological model to map the zones in Chicago where high levels of social problem were concentrated. During this period, Chicago was experiencing a long period of economic growth, urban expansion, and foreign immigration. They were particularly interested in the zones of transition between established working class neighbourhoods and the manufacturing district. The city’s poorest residents tended to live in these transitional zones, where there was a mixture of races, immigrant ethnic groups, and non-English languages, and a high rate of influx as people moved in and out. They proposed that these zones were particularly prone to social disorder because the residents had not yet assimilated to the American way of life. When they did assimilate they moved out, making it difficult for a stable social ecology to become established there.