- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School’s In

- In the Media

You are here

How technology is reinventing education.

New advances in technology are upending education, from the recent debut of new artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT to the growing accessibility of virtual-reality tools that expand the boundaries of the classroom. For educators, at the heart of it all is the hope that every learner gets an equal chance to develop the skills they need to succeed. But that promise is not without its pitfalls.

“Technology is a game-changer for education – it offers the prospect of universal access to high-quality learning experiences, and it creates fundamentally new ways of teaching,” said Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who is also a professor of educational technology at the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning . “But there are a lot of ways we teach that aren’t great, and a big fear with AI in particular is that we just get more efficient at teaching badly. This is a moment to pay attention, to do things differently.”

For K-12 schools, this year also marks the end of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding program, which has provided pandemic recovery funds that many districts used to invest in educational software and systems. With these funds running out in September 2024, schools are trying to determine their best use of technology as they face the prospect of diminishing resources.

Here, Schwartz and other Stanford education scholars weigh in on some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom this year.

AI in the classroom

In 2023, the big story in technology and education was generative AI, following the introduction of ChatGPT and other chatbots that produce text seemingly written by a human in response to a question or prompt. Educators immediately worried that students would use the chatbot to cheat by trying to pass its writing off as their own. As schools move to adopt policies around students’ use of the tool, many are also beginning to explore potential opportunities – for example, to generate reading assignments or coach students during the writing process.

AI can also help automate tasks like grading and lesson planning, freeing teachers to do the human work that drew them into the profession in the first place, said Victor Lee, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “I’m heartened to see some movement toward creating AI tools that make teachers’ lives better – not to replace them, but to give them the time to do the work that only teachers are able to do,” he said. “I hope to see more on that front.”

He also emphasized the need to teach students now to begin questioning and critiquing the development and use of AI. “AI is not going away,” said Lee, who is also director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), which provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students across subject areas. “We need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology.”

Immersive environments

The use of immersive technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality is also expected to surge in the classroom, especially as new high-profile devices integrating these realities hit the marketplace in 2024.

The educational possibilities now go beyond putting on a headset and experiencing life in a distant location. With new technologies, students can create their own local interactive 360-degree scenarios, using just a cell phone or inexpensive camera and simple online tools.

“This is an area that’s really going to explode over the next couple of years,” said Kristen Pilner Blair, director of research for the Digital Learning initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, which runs a program exploring the use of virtual field trips to promote learning. “Students can learn about the effects of climate change, say, by virtually experiencing the impact on a particular environment. But they can also become creators, documenting and sharing immersive media that shows the effects where they live.”

Integrating AI into virtual simulations could also soon take the experience to another level, Schwartz said. “If your VR experience brings me to a redwood tree, you could have a window pop up that allows me to ask questions about the tree, and AI can deliver the answers.”

Gamification

Another trend expected to intensify this year is the gamification of learning activities, often featuring dynamic videos with interactive elements to engage and hold students’ attention.

“Gamification is a good motivator, because one key aspect is reward, which is very powerful,” said Schwartz. The downside? Rewards are specific to the activity at hand, which may not extend to learning more generally. “If I get rewarded for doing math in a space-age video game, it doesn’t mean I’m going to be motivated to do math anywhere else.”

Gamification sometimes tries to make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” Schwartz said, by adding art and rewards to make speeded response tasks involving single-answer, factual questions more fun. He hopes to see more creative play patterns that give students points for rethinking an approach or adapting their strategy, rather than only rewarding them for quickly producing a correct response.

Data-gathering and analysis

The growing use of technology in schools is producing massive amounts of data on students’ activities in the classroom and online. “We’re now able to capture moment-to-moment data, every keystroke a kid makes,” said Schwartz – data that can reveal areas of struggle and different learning opportunities, from solving a math problem to approaching a writing assignment.

But outside of research settings, he said, that type of granular data – now owned by tech companies – is more likely used to refine the design of the software than to provide teachers with actionable information.

The promise of personalized learning is being able to generate content aligned with students’ interests and skill levels, and making lessons more accessible for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. Realizing that promise requires that educators can make sense of the data that’s being collected, said Schwartz – and while advances in AI are making it easier to identify patterns and findings, the data also needs to be in a system and form educators can access and analyze for decision-making. Developing a usable infrastructure for that data, Schwartz said, is an important next step.

With the accumulation of student data comes privacy concerns: How is the data being collected? Are there regulations or guidelines around its use in decision-making? What steps are being taken to prevent unauthorized access? In 2023 K-12 schools experienced a rise in cyberattacks, underscoring the need to implement strong systems to safeguard student data.

Technology is “requiring people to check their assumptions about education,” said Schwartz, noting that AI in particular is very efficient at replicating biases and automating the way things have been done in the past, including poor models of instruction. “But it’s also opening up new possibilities for students producing material, and for being able to identify children who are not average so we can customize toward them. It’s an opportunity to think of entirely new ways of teaching – this is the path I hope to see.”

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Watch TED-Ed videos

The TED-Ed project — TED's education initiative — makes short video lessons worth sharing, aimed at educators and students. Within TED-Ed’s growing library of lessons, you will find carefully curated educational videos, many of which are collaborations between educators and animators nominated through the TED-Ed platform.

Featured TED-Ed videos

Why are cats so weird?

The science of skin color

How playing an instrument benefits your brain

The physics of the hardest move in ballet

What would happen if you didn't sleep

Why should you listen to Vivaldi's "Four Seasons"?

What gives a dollar bill its value

Would you sacrifice one person to save five

What really happens to the plastic you throw away

How to understand power

What is bipolar disorder

Why it's so hard to cure HIV/AIDS

Einstein's miracle year

The unexpected math behind Van Gogh's "Starry Night"

What makes a hero

The science of stage fright and how to overcome it

View all TED.com featured TED-Ed videos

Explore TED-Ed

Watch a lesson, customize a lesson, and explore TED-Ed's growing library of educational resources!

About TED-Ed

Learn about TED-Ed's commitment to creating lessons worth sharing.

- Tuition & Financial Aid

- Online Experience

Integrating Technology in the Classroom: Best Practices

Technology has been reshaping society throughout time. Long before ChatGPT came on the scene, digital technologies started changing the world of work and the skills required for success. As one proof point, the World Economic Forum says that new technologies will remain a key driver of business transformation through 2027. 1 The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics provides more proof in its projection of 23% job growth for computer and information research scientists from 2022-2032. 2 That's compared to 0.3% annual growth for jobs overall during the same time. 3

The Importance of Technology in Education

Because our society and economy are so dependent on technology, school leaders and teachers must prioritize creating technology literacy as part of making sure students are ready for life beyond high school. Getting the best results from technology integrations may require new operating methods and problem-solving techniques but still relies on proven principles and goals for education and enhancing student learning experiences. This blog explores best practices for effectively using technology to create engaging, interactive, and inclusive learning environments. Discover how embracing technological advancements can prepare students for a tech-savvy future while supporting their diverse learning needs.

Building Modern Skills for Success

Developing technical skills such as digital literacy, coding, and data analysis are essential to prepare students for tech-driven careers and beyond. Basic technical skills are important for navigating online platforms, understanding digital tools, and making data-informed decisions. 4

Soft skills like empathy and collaboration are equally vital because they help students communicate effectively, resolve conflicts, and work well in diverse, tech-rich environments. These skills ensure students can ethically and responsibly interact in digital spaces and contribute positively to online communities. 5

Enhancing Learning Experiences

Gamified learning tools like Zearn, Amira, and Duolingo provide personalized learning platforms that adapt to each student's pace and skill level. Interactive digital technology like this can make learning fun, keeping students actively engaged to achieve better outcomes. 4

While technology enhances learning, it's crucial to maintain balance. Over-reliance on tech can be counterproductive. Educators should integrate technology in moderation to ensure it complements traditional teaching methods, adding instructional value without overwhelming students. 6

Supporting Diverse Learners

Technology supports diverse learning needs by enabling differentiated instruction. Tools like interactive quizzes and multimedia resources cater to various learning styles, helping every student grasp complex concepts effectively. Technology tools can also foster collaboration among students. Features that support group work and peer interaction help students learn from each other, promoting a more inclusive and supportive learning environment.

Digital Literacy: Preparing Students for a Tech-Savvy Future

Digital literacy involves using technology to learn, create, and participate in the digital world. It is essential for students to develop these skills to navigate and leverage technology effectively both inside and outside the classroom. 7

Digital Citizenship

Teaching digital citizenship helps students understand the ethical use of technology and the responsibilities that come with interaction in virtual worlds.

Key areas to cover include: 5, 6, 7

- Misinformation and disinformation

- Balancing online and offline activities

- Mental health topics

A responsible use policy (RUP) is valuable for teaching digital citizenship. In addition to setting boundaries for acceptable behavior, it can help students focus on positive behaviors like giving credit to content creators, being kind online, and using technology to solve problems. An effective RUP includes clear purpose statements, desired behaviors, and plans for resolving issues. 8

Essential Digital Skills

Coding, data analysis, and online research are digital skills that will help students thrive. These foundational skills enable students to use technology effectively and prepare them for future academic and career opportunities.

Considerations for Implementing Educational Technology

While there are many technical aspects to choosing instructional technology, it’s important to begin with a clear understanding of your goals and to assess and plan for the human considerations surrounding technology use.

Start with Clear Objectives

To successfully integrate technology in the classroom, start by identifying specific instructional goals. Focus on the learning activity and explore how the chosen technology aligns with lesson objectives and enhances the learning experience. 9 Consider how class time will be spent and select learning technology tools that match the educational goals without requiring extensive time to learn. For young kindergarten and elementary school students, prioritize digital technologies that support fundamental skills without excessive screen time, ensuring that the time spent on devices is appropriate for their age and learning needs.

Foster a Growth Mindset

Teaching students to have a growth mindset, which holds that intelligence can be developed through effort and perseverance, is even more important than teaching students to use the tools. You can play a vital role as a teacher by emphasizing hard work and providing ample opportunities for practice and feedback. Supporting students through challenges and valuing learning over innate talent reinforces this mindset, creating a motivating classroom environment. 10

Because digital technology is always evolving, teachers must also embrace a growth mindset in their work. By learning alongside them, you can encourage students and model the habits of a lifelong learner. 11

Teacher Professional Development Is Essential

New educational technologies can provide a wealth of data about student progress, but teachers need to be trained to understand what the data is telling them. Being more data literate helps teachers understand student needs better and adapt their teaching methods accordingly, driving improved student outcomes. That is one of the reasons the University of Iowa’s Online Master of Arts in Teaching, Leadership, and Cultural Competency core curriculum includes a choice of courses on technology integration or participatory learning and media, along with several STEM electives.

However, only a fraction of teachers have learned to analyze data in their preparation programs, highlighting the need for ongoing professional development. School districts must support teachers in their efforts to become more adept at analyzing data, as well as helping them keep up with developments in educational technology. 7

Make the Technology Accessible

Ensuring accessibility in instructional technology involves both effective communication and thoughtful choice of technology. Teachers and school administrators should eliminate jargon and clearly explain the technology's use and data to make new technology non-threatening for students and their families. 7

Providing clear communication and resources to families helps them understand classroom technology and fosters trust and collaboration. Establishing a two-way communication channel with families through your school's learning management system or another digital platform can also extend the classroom, empowering caregivers to support and reinforce positive technology use at home. 6

Additionally, it's crucial to consider how students access lessons outside of school. Frequently, lower-income students have greater access to smartphones than high-speed internet, so being aware of which digital devices can support your educational content is essential. 7

Protect Student Privacy

Student privacy is an important and multifaceted issue. It includes protecting information about and from students, their families, and schools. Two major federal laws, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), outline protections for student data.

While there's a lot to understand, begin by consulting school and district policies for guidelines. Also, consider incorporating lessons into classwork that educate students on privacy risks and strategies to protect their own information. 6, 7

Choose the Right Tools

To effectively incorporate technology into the classroom, begin with how the tool(s) support achieving instructional goals and enhance learning experiences. Good reasons to use technology in education include encouraging engagement, differentiating and personalizing instruction, and increasing digital fluency. 4

Consider the following:

Purpose and Goals :

- Start by asking questions : Identify the specific learning activity and explore how assistive technology can help your students achieve the desired results

- Instructional alignment : Choose tools that match your instructional goals, such as screencasting software for making student presentations, or AI-assisted tutoring programs that allow students to progress at their own pace 12

Quality and Engagement :

- Interactive over passive : to increase student engagement, prioritize tools that offer interactive opportunities over passive consumption

- Task monitoring : Select platforms that allow you to track the students' learning process and provide timely feedback. Also consider whether there are integrations with other instructional technology such as your school's learning management system

Student Perspective :

- Ease of use : Evaluate the tool from a student's perspective to ensure it’s user-friendly

- Free vs. paid versions : Consider the impact of ads and age-appropriateness in free versions, and regularly check for updates 13

Engagement Features :

- Motivational elements : Be mindful of features like streaks and rewards, which can encourage engagement but may also lead to compulsive behaviors

Monitor and Evaluate

Ensure the success of technology integrations by regularly monitoring the results and comparing them to desired learning outcomes. One approach is to use the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) framework. The PDSA model involves planning a change, implementing it, studying the results, and acting on what is learned. 14

Base the study phase on technology-generated data, combined with feedback from students and, if relevant, family members or other stakeholders. To borrow a phrase from the technology field, consider designing your program to "fail fast" to get to success. With this approach, you implement limited-scope pilot programs and short evaluation cycles, iterating quickly to refine your approach for the best results. 4, 5

Effective Use of Educational Technology

Research indicates you can achieve the best results by using digital technology in the classroom with a blended learning approach. A recent meta-study of higher education results published by the Brookings Institution also has implications for best practices in using technology in K-12 settings. Blended learning combines traditional in-class instruction with online and digital learning experiences. This approach allows students to engage with course material both inside and outside the classroom, enhancing their overall learning experience. In addition, using a blended learning approach can be easier for teachers, particularly those who are learning to use the technology, to implement. 15

What is a Flipped Classroom?

The flipped classroom is a popular method of implementing blended learning. In this model, students watch digitized or online classes as homework, freeing up face-to-face class time for active learning activities such as discussions, peer teaching, projects, and problem-solving. 15

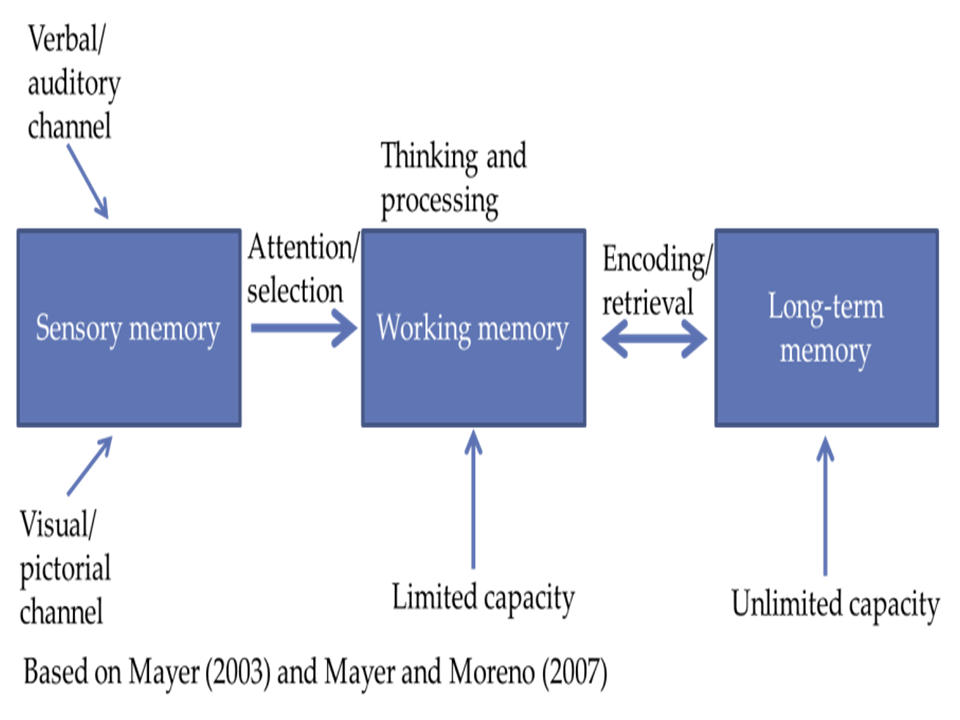

Theoretical Benefits

According to constructivist theory, this active learning approach enables students to build upon their pre-existing knowledge, resulting in deeper understanding. It also reduces cognitive load during class, allowing students to form more complex ideas. 15

Effectiveness in Practice

Research has shown that students in flipped classrooms perform better academically compared to traditional lecture-based settings, particularly in language, technology, and health science courses. Smaller gains in student outcomes were found in math and engineering courses. The Brookings study also showed that "In addition to confirming that flipped learning has a positive impact on foundational knowledge (the most common outcome in prior reviews of the research), we found that flipped pedagogies had a modest positive effect on higher-order thinking. Flipped learning was particularly effective at helping students learn professional and academic skills." 15

Practical Considerations

Teachers can use various platforms, such as the school's learning management systems, class blogs, or shared documents, to help students access online courses, creating authentic learning experiences both at home and in school. 6

How Educational Technology Supports Student Engagement

Classroom technology and specific approaches to using assistive technology in lesson plans can support student engagement in several ways. Interactive learning through technologies ranging from interactive smartboards and online quizzes to educational apps can make the learning experience more dynamic and engaging. 16

In addition to the benefits mentioned above, the flipped classroom can provide meaningful opportunities for student interactions, and well-designed lessons can provide valuable support for developing students' intra- and interpersonal skills. 15

Project-based learning can be a powerful approach to technology-aided education. ISTE.org, an association of K-12 and university educators "dedicated to making teaching and learning more meaningful for educators and learners around the globe," 17 has suggested using project-based, creative assessments to supplement traditional assessments at least once a semester.

In these assessments, "The teacher poses a question, tells students what the standards are and asks them to demonstrate their knowledge through a creative project." The project could take many different forms, depending on your subject, grade level, available technology, and educational goals. Students build problem-solving skills along with deepening their mastery of the subject while working through the assessments. 18

What Tech Do You Need in the Classroom?

Instructional technology can be divided into four categories: learning management systems, content creation and presentation, application software, and collaborative tools.

The potential benefits of a learning management system (LMS) begin with making it easier to store and update lesson plans, but go much further. Depending on the specific system and its integrations, your LMS can store lesson resources, accept student assignments and administer assessments, help students and teachers monitor progress, record grades, and report aggregate performance data.

Content creation and presentation tools include interactive whiteboards (smartboards), laptop computers and tablets. In addition to offering many ways to "write" on the board, a smartboard can typically display rich media, offer interactive activities for students to engage with, and connect to the internet. Some can even save lessons and send them to students who have missed a class session. 19 Education technology is dynamic, with new apps and software being developed regularly. Online resources, including ISTE, Edutopia, and Commonsense, frequently publish roundups of popular apps and software. Google Classroom, Microsoft Teams, and Zoom are popular tools for collaboration and online education.

Embracing AI's Potential in Modern Education

AI is poised to change work and society in ways we can hardly begin to anticipate. By embracing its potential, schools help prepare students for future careers and societal roles. Additionally, AI is already providing educational benefits, including personalized learning and intelligent tutoring, through its integration with popular tools like Amira and Duolingo.

Critical Thinking and Responsibility

Teach students to think critically and act responsibly when working with AI. This includes understanding AI's capabilities and limitations and recognizing ethical considerations. 20

Process-Focused Learning

Design lesson plans that focus on the learning process. Use AI as a launching pad for students' creativity or critical thought rather than as an end in itself. Emphasize the importance of developing ideas and continual improvement. 21

Specific Tips for Teachers

Teachers can incorporate the following tips, cleverly developed around the acronym “ChatGPT” by Jack Dougall, a secondary school humanities and business teacher in Spain, into their project instructions to help students effectively use AI tools: 22

- Converse : Engage in dialogue with AI; it's not a simple search engine

- Hypothesize : Predict possible responses to identify errors

- Adapt : Reframe questions or dive deeper if initial responses aren't sufficient

- Think : Reflect on AI responses for accuracy and bias

- Gather : Cross-verify AI-generated information with other sources

- Probe : Ask follow-up questions for deeper understanding

- Train : Continually refine interactions with AI for effective use

A Technology Case Study with Real-World Inspiration

You don’t need a hefty technology budget to start integrating technology tools into your classroom as long as you approach it creatively. Mary Howard, a sixth-grade teacher in Grand Island, New York, capitalized on the popularity of escape rooms to create an interactive digital exercise with built-in engagement mechanisms. 23 In Howard's escape room lesson, student teams created their own escape room activities by developing narratives, designing puzzles, and embedding clues using digital tools like QR codes. They then presented their challenges to their classmates. This process encouraged students to engage deeply with the material, apply problem-solving skills, and collaborate effectively.

The attraction for students is based on four principles: narrative-based challenges, a time element, solution or reward focus, and the inclusion of clues, riddles, or puzzles. Exercises like these can be adapted with tools like Klikaklu or GooseChase for various subjects and grade levels. 23

Embrace the Technology Integration Journey with the University of Iowa

Integrating technology in the classroom can enhance learning experiences, support diverse learners, and prepare students for a tech-driven future. Educators can create engaging and effective learning environments by focusing on digital literacy, fostering a growth mindset, and using innovative tools and methods like AI and flipped classrooms. Being open to new ideas and cultivating a growth mindset are keys to your professional development and providing a model for students to follow.

If you're ready to deepen your understanding of how technology can support student success, consider the University of Iowa's affordable, part-time Online MA in Teaching, Leadership, and Cultural Competency (MATLCC) . The program equips you with conceptual frameworks, strategies, and tactics that can empower students for 21st-century success and fuel your growth as an educational professional. You can keep teaching while you learn and immediately apply your new skills. Contact an admissions outreach advisor to learn more.

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/digest/

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from bls.gov/ooh/computer-and-information-technology/computer-and-information-research-scientists.htm

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from bls.gov/news.release/ecopro.nr0.htm

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from commonsense.org/education/articles/3-essential-questions-for-edtech-use

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from iste.org/blog/edtech-for-good-experts-weigh-in

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from commonsense.org/education/articles/teachers-essential-guide-to-teaching-with-technology

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from newleaders.org/blog/how-the-best-k-12-education-leaders-build-data-literacy

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from iste.org/blog/5-tips-for-creating-a-district-responsible-use-policy

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from https://iste.org/blog/stop-talking-tech-3-tips-for-pedagogy-based-coaching

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from apa.org/ed/precollege/psychology-teacher-network/introductory-psychology/growth-mindset-classroom-cultures

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from iste.org/blog/iste-certified-educator-shares-4-tips-for-teaching-with-tech

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from iste.org/blog/stop-talking-tech-3-tips-for-pedagogy-based-coaching

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from edutopia.org/article/evaluating-tech-tools-classroom

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from edutopia.org/article/data-literacy-skills-teachers/

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from brookings.edu/articles/flipped-learning-what-is-it-and-when-is-it-effective

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from edutopia.org/video/flipped-class-which-tech-tools-are-right-you/

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from iste.org/our-story

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from iste.org/blog/with-imagination-and-the-right-apps-students-learn-and-can-prove-it

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from insights.samsung.com/2024/05/15/what-are-the-advantages-of-smart-boards-in-the-classroom-2/

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from https://iste.org/blog/what-educators-and-students-can-learn-from-chatgpt

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from https://iste.org/blog/chatgpt-ban-it-no-embrace-it-yes

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from https://iste.org/blog/help-students-think-more-deeply-with-chatgpt

- Retrieved on July 24, 2024, from iste.org/blog/use-escape-rooms-to-deepen-learning

Return to University of Iowa Education Blog

This will only take a moment.

Spring 2025 Term

The University of Iowa has engaged Everspring , a leading provider of education and technology services, to support select aspects of program delivery.

The future of educational technology

Dan Schwartz is a cognitive psychologist and dean of the Stanford Graduate School of Education.

He says that artificial intelligence is a different beast, but he is optimistic about its future in education. “It’s going to change stuff. It’s really an exciting time,” he says. Schwartz imagines a world not where AI is the teacher, but where human students learn by teaching AI chatbots key concepts. It’s called the Protégé Effect, Schwartz says, providing host Russ Altman a glimpse of the future of education on this episode of Stanford Engineering’s The Future of Everything podcast.

Listen on your favorite podcast platform:

Related : Dan Schwartz , professor of educational technology

[00:00:00] Dan Schwartz: You know, the tough question for me is, should you let the kid use ChatGPT during the test? Right? And we had this argument over calculators, right? And finally they came up with ways to ask questions where it was okay if the kids had calculators. Because the calculator was doing the routine stuff and that's not really what you cared about. What you cared about was, could the kid be innovative? Could they take another, a second approach to solve a problem? Things like that.

[00:00:33] Russ Altman: This is Stanford Engineering's The Future of Everything, and I'm your host, Russ Altman. If you're enjoying The Future of Everything podcast, please hit the follow button in the app that you're listening to now. This will guarantee that you never miss an episode.

[00:00:46] Today, Dan Schwartz will tell us how AI is impacting education. He studies educational technology and he finds that there's a lot of promise and a lot of worries about how we're going to use AI in the classroom. It's the future of educational technology. Before we get started, please remember to follow the show in the app that you listen to. You'll be alerted to all of our episodes and it'll make sure that you never miss the future of anything.

[00:01:16] You know, the rise of AI has been on people's minds ever since the release of ChatGPT. Especially the powerful one that started to do things that were scary good. We've seen people using it in business, in sports, in entertainment, and definitely in education. When it comes to education, there are some fundamental questions, however, are we teaching students how to use AI? Or are we teaching students? How do we assess them? Can teachers grade papers with AI? Can students write papers with AI? Why is anybody doing anything? Why don't we just have the AI talk to itself all day? These are real questions that come up in AI.

[00:01:55] Fortunately, we're going to be talking to Dan Schwartz, who's a professor of education and a dean of the School of Education at Stanford University about how AI is impacting education.

[00:02:06] Dan, the release of ChatGPT has had an impact all over the world, people are using it in all kinds of ways. And clearly one of the areas that AI, especially generative AI has made impact is in education. Students are clearly using it, teachers are thinking about using it or using it. You're the Dean of Education at Stanford. What's your take on the situation right now for AI in education?

[00:02:33] Dan Schwartz: Okay, so lots of answers to that, but, but, you know, the thing I've enjoyed the most is, uh, showing it to people and watching their reaction. So I'm a cognitive psychologist. I study creativity, learning, what it means to understand. And you show this to people and you just see them go, oh my lord.

[00:02:53] And then the next thing you see is they begin to say, uh, what's left for humans? Like what's left? And then they sort of say, wait a minute, will there be any jobs? And then finally they sort of say. Oh my goodness, education needs to change. And as a dean who raises money for a school, this is the best thing to ever happen. No, whether it's good or bad, it doesn't matter. Everybody realizes it's going to change stuff. And so it's really an exciting time.

[00:03:22] Russ Altman: So that is really good news. I have to say going into this and I have to reveal a bias. I have often wondered if technology has any place in a classroom. And I think it's because I was, uh, I was injured as a youth.

[00:03:37] This is in the 1970s when some teachers tried to put a computer program in front of me and I was a pretty motivated student and I worked with this computer for about six minutes, and I should say, I'm not an anti-computer person. I literally spent all my time writing algorithms and doing computation work. But I just felt as a youth that I wanted to have a teacher in front of me, a human telling me things. Uh, and so that is clearly not the direction, I hear you laughing. So talk to me about the appropriate way to think about computers. Because I really have a big negative reaction to the idea of anything standing between me and a teacher.

[00:04:18] Dan Schwartz: You must have had very good teachers.

[00:04:19] Russ Altman: I might have.

[00:04:19] Dan Schwartz: So Russ, you sound like someone who doesn't play video games.

[00:04:23] Russ Altman: I do not play video games.

[00:04:24] Dan Schwartz: So there's this world out there where people can experience things they could never experience, uh, directly. And no teacher can deliver this immersive experience of you in the Amazon searching for anthropological artifacts. There's also something called social media that people use.

[00:04:43] Russ Altman: I've heard about this.

[00:04:43] Dan Schwartz: Yeah. Yeah.

[00:04:44] Russ Altman: I think we disseminate the show using it.

[00:04:46] Dan Schwartz: So back in the day.

[00:04:47] Russ Altman: Okay. So I'm a dinosaur.

[00:04:49] Dan Schwartz: Uh, back in the day, you got the Apple 2 maybe, and it's about 64 K, maybe. It's got a big floppy drive and it takes all its CPU power to draw a picture of a two plus two on the screen. So I think things have changed a little bit Russ. But I appreciate your desire to be connected to teachers. I don't think we're replacing them.

[00:05:14] Russ Altman: I'm not going to give you a lecture about teaching. But I will say this one sentence that was reverberating through my brain when I was getting ready for our interview, which was when I'm in a classroom, and this has been since I've been in third grade. I am watching the teacher trying to understand, how they think about the information and how they struggle with it to like understand it and then try to relay it to me.

[00:05:34] And so it is, that's where I'm learning. I'm, it's not even what they're saying. It's they're painting a picture for their cognitive model of what they're talking about. And that's what I'm trying to pull out to this day. And so that's why I have such a negative reaction to anything standing between me and this other human who has a model that is more advanced than mine about the material that we're struggling with and I just, I'm trying to download that model.

[00:06:01] Dan Schwartz: Wow. You're, you are a cognitive psychologist, Russ?

[00:06:03] Russ Altman: I don't know.

[00:06:05] Dan Schwartz: Like I had a buddy who sort of became a Nobel laureate. And he talked about how he loved take apart cars, and I'd say I love to watch you take apart cars, just to figure out what you're doing. No, so I think, let's separate this. There's the part where you think the interaction with the teacher is important. I don't know that you need it eight hours a day. You know, that's an awful lot of interaction. I'm not sure I want to be with my mom and dad for eight hours a day trying to figure out their thinking. So you don't need it all the time.

[00:06:34] On the other side, you know, we can do creative things with the computers. So for example, I wrote a program where students learn by teaching a computer agent. And so they're trying to figure out how to get the agent to think the way it should in the domain. Turns out it's highly motivating. The kids learn a lot. The problem was the technology quickly became obsolete. Because after kids used it for a couple of days, they no longer needed it, 'cause they'd figured out sort of how to do the kind of reasoning that we wanted them to teach the agent to do for reasoning.

[00:07:06] Russ Altman: That's exactly what I was talking about before, about my relationship with my teacher. And you just flipped it, but it's the same idea, which is that there's a cognitive model that you're trying to transfer. And by doing that transfer, you get in, you introspect on it and you understand what it is that you're thinking about.

[00:07:22] Dan Schwartz: I think that's right. You know, so the concern is the computer does all the work, right? And so I'm just sitting there pressing a button that isn't relevant to the domain I'm trying to learn. But you know, uh, one of the things computers are really good at, like as good as casinos, is motivation. So some computer programs, they gamify it. I'm not sure that's a great use of it. Because you, you know, you try and you learn to just beat the game for the reward.

[00:07:49] Russ Altman: Right.

[00:07:49] Dan Schwartz: As opposed to learn the content. But things like having, teaching an intelligent agent how to think. There's something called the protege effect, which is you'll try harder to learn the content to teach your agent than you will to prepare for a test. Right? So we can make the computer pretty social.

[00:08:08] Russ Altman: Okay. So you are clearly a technology optimist in education. And in addition to the amazing fundraising and like, there's so many questions to be answered. What I think a lot of people are worried about is, are we at risk of losing a gen. We've already lost a few generations of students, some people argue, because of the pandemic and the terrible impact it had, especially on, uh, on people who weren't privileged in society and in their education.

[00:08:34] Are we about to enter yet another shock to the system where, because of the ease of having essays written and having, and grading papers, that we really don't serve a generation of students well? Or do you think that's a overhyped, unlikely to happen thing?

[00:08:51] Dan Schwartz: No, it's a good question. You know, that part of this is people's view about cheating, you know? And so it's too easy for students to do certain things. But there's another response that I want to hang on to. I want to ask you, Russ, are you using, you teach.

[00:09:07] Russ Altman: Yeah.

[00:09:07] Dan Schwartz: Are you like putting in all sorts of rules to prevent students from cheating, or are you saying, use it, do whatever you can. I'm going to outsmart your technique anyway.

[00:09:17] Russ Altman: It's a little bit more on the latter. So we, uh, I teach an ethics class, which is a writing class. And we allow ChatGPT because the, my fellow instructor and I decided, and this was the quote, we want to be part of the future, not part of the past. So we said to the students,

[00:09:33] Dan Schwartz: Sorry, The Future of Everything, Russ.

[00:09:34] Russ Altman: Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. And thanks for the plug. So, uh, we allow it. We asked them to tell us what prompt they used and to show us the initial output that they got from that prompt. And then we, of course, have them hand in the final thing. And we instruct the TAs and ourselves, when we grade that we're grading the final product with or without a declaration of whether ChatGPT is used.

[00:09:56] We do have engineers as TAs, which means that they did a careful analysis. Students who used ChatGPT, and I don't think this is a surprise, got slightly lower grades, but spend substantially less time on the assignment. So if you're a busy student, you might say, I will make that trade off because the grades weren't a ton worse. It was like two points out of a hundred, like from a ninety to an eighty-eight, and they completed it in like half the time.

[00:10:25] Dan Schwartz: Uh, do you think they learned less?

[00:10:28] Russ Altman: So we don't know. We don't know. And, uh, the evaluation of learning is something that I'm looking to you, Dan. Uh, how do I tell? So, um, so we do try to use it. But we are stressed out. We have seen cases where people say they used ChatGPT, but tried to mislead us in how they use it. They said, I only used it for copy editing, but it was clear that they did more than copy editing with it. And so there's at the edges, there are some challenges. But in the end, we said motivated students who want to learn will use it as a tool and we'll learn. And the students who we have failed to motivate, and it is our failure, you could argue. They're just going to do whatever they do, and we're not going to be able to really impact that trajectory very much.

[00:11:12] Dan Schwartz: Yeah, you know, you sort of see the same thing with video, video-based lectures. So I'm online. I've got this lecture. Do I really want to sit and listen to the whole thing? Not really. I'm going to skim forward to find the information. I skim back. I'm probably going to end up doing the minimum amount if it's not a great lecture.

[00:11:29] Russ Altman: Yeah.

[00:11:29] Dan Schwartz: So I'm not sure this is a ChatGPT phenomenon. It's just, it's sort of an enabler. I think the challenge is thinking of the right assignment. So like, you can grade things on novel and appropriateness. So, are they novel? You know, if they use ChatGPT like everybody else, they won't be novel. They'll all produce the same thing.

[00:11:48] Russ Altman: It's incredibly, yes. It, so it is, um, there's the most common type of, uh, moral theory is called common morality. And it turns out that ChatGPT does pretty well at that one because there's so many examples that it has seen. And it's terrible at Kant. Deontology, it really can't do. Okay, so let me.

[00:12:07] Dan Schwartz: So let me get back to your question.

[00:12:09] Russ Altman: Yeah.

[00:12:09] Dan Schwartz: So here's what I see going on right now. There, there are like, uh, big industry conferences. Because they're going to, they're producing the technology that schools can adopt. Right? And there's a lot of money there. And twenty years ago, there were zero unicorns, and about, uh, I think last year, fifty-four billion dollar valuation companies in ed tech. So this is a big change. So what are they doing? They're basically creating things to do stuff to students, right?

[00:12:42] So maybe they're marketing to the teachers, but it's, you know, it's, I'll make a tutor that, uh, is more efficient at delivering information to the students. Or, I will make a program that can correct their math very quickly. And so what's happening is the industry is sort of using the AI in the way that nobody else uses it.

[00:13:04] Because everybody who's got this tool wants to create stuff, right? Like, uh, my brother. It's my birthday, what does he do? He has ChatGPT to write me a poem about Dan Schwartz at Stanford. What he doesn't know is that there's a lot of Dan Schwartz's and so evidently I wear colorful ties, but this is what everybody wants to do. They want to create with it. Meanwhile, the field is trying to push towards efficiency. Can we get the kids done faster? Can we get them through the curriculum faster? Can we correct them faster? In which case the kids are going to optimize for being really efficient, right? As opposed to just trying to be creative, innovative, use it for deeper kinds of things. So this is my big fear.

[00:13:42] Russ Altman: And so you're watching these companies and I'm guessing that they don't always ask your opinion about what's, what would you tell, so let's say a, one of these unicorn billion dollar or more companies comes to you and says, we want to do this right. We want to use the best educational research to create AI that can bring education to people who might otherwise not have quality education. What would you tell them?

[00:14:04] Dan Schwartz: So this is a challenge, right? This is something we're actively trying to solve. So we've created a Stanford accelerator for learning to kind of figure out how to do this. 'Cause I've been in this ed tech position for quite a while. And the companies come in and they say, we really want your opinion. And then they present what they're doing. And I go, uh, have you ever thought of, and they go, wait, let me finish. And this goes on for fifty-five minutes. Where they're telling me what they want to do. And I'm trying to say, you know, if you just did this. And the way it ends is I say to them, look, you, if you do these three things, I'll consider being an advisor.

[00:14:42] Russ Altman: Right.

[00:14:42] Dan Schwartz: They never come back.

[00:14:45] Russ Altman: So the message you're sending them is just not in their worldview.

[00:14:50] Dan Schwartz: It's because they have a vision. Everybody wants to start their own school.

[00:14:53] Russ Altman: Yeah.

[00:14:53] Dan Schwartz: They have their vision of what it should be and they're urgent to get it done. And you know, it's a startup mentality. So trying to figure out how can we educate them? You know, I think we know a lot about how people learn that, uh, that we didn't know twenty years ago when they went to school. And the AI, you know, one of the things it can do is implement some of these theories of learning in ways that don't exist in textbooks and things like that.

[00:15:17] So that's the big hope. And the question is, how can you take advantage of industry? You know, education is a public good, but they still buy all their products. And so going through those companies is one way to sort of bring a positive revolution. But again, I'm a little worried that the companies are, and they're sort of optimizing for local minima.

[00:15:41] Russ Altman: Yeah.

[00:15:41] Dan Schwartz: You know, to accommodate the current schools and things like that.

[00:15:44] Russ Altman: Should we take, so what, should we take solace in the teachers? So many of us are fans of teachers, grammar school teachers, middle school teachers, high school teachers, but many of these folks are incredibly dedicated. Will they be a final, um, uh, a final filter that looks at these, uh, educational technologies and says, absolutely not. Or yeah, we'll use that, but we're going to use that in a way that makes sense for my way of teaching. Or are they not in a position to make those kinds of, what you could call courageous decisions, about kind of modifying the use of these tools to make them as good as possible in, uh, on the ground?

[00:16:21] Dan Schwartz: So it's pretty interesting. The surveys I've seen, uh, sort of over the last year, the different groups do different surveys. It, it sort of, if I take the average, about sixty percent of K 12 teachers are using GenAI, right? And about thirty percent of the kids. If I go to the college level, about thirty percent of the faculty are using GenAI in teaching and about eighty percent of the kids are using it. So I do think in the pre K to 12 space, the teachers are making decisions. They do a lot of curriculum. There are, so a great application is, um, project-based learning. So project-based learning is a lot of fun. Kids learn a lot. They sort of develop a passion, a certain depth. As opposed to just mastering sort of the requirements, but it's really hard to manage. You know, when I was a high school teacher, I had a hundred and thirty kids, right?

[00:17:11] If all of them have a separate project, I have to help plan them and make them goal, you know, learning goal appropriate. So the GenAI can help me do that. It can help me, uh, have the kids sort of help use it to help them design a successful project. Uh, it can help me with a dashboard that helps manage them, hitting their milestones, things like that.

[00:17:31] And there, you know, it's, it, the, teacher is like, I can do something I just couldn't do before.

[00:17:35] Russ Altman: Yeah. Yeah.

[00:17:36] Dan Schwartz: It's different than the model where you put the kids in the back of the room who finished early and say, go use the computer. I think, you know, most schools, kids are carrying computers in classes. So it's a little different. It's more integrated than it used to be.

[00:17:52] Russ Altman: This is the Future of Everything with Russ Altman. More with Dan Schwartz, next.

[00:18:06] Welcome back to The Future of Everything. I'm Russ Altman and I'm speaking with Dan Schwartz, professor of education at Stanford University.

[00:18:12] In the last segment, Dan told us about AI, education, some of the promises and some of the pitfalls that he's looking at on the ground, thinking about how to educate the next generation.

[00:18:23] In this segment, I'm going to ask him about assessment, grading. How do we do that with AI and how do we make sure it goes well? Also going to ask him about physical activity, which turns out physical ness is an important part of learning.

[00:18:39] I want to get a little bit more detailed, Dan, in this next segment, and I want to start off with assessment, grading. I know you've thought about this a lot. People are worried that um, AI is going to start to doing, be doing all the grading. Everybody knows that a high school teacher with a big, couple of big classes can spend their entire weekend grading essays. It is so tempting just to feed that into ChatGPT and say, hey, how good is this essay? How should we think about, maybe worry about, but maybe just think about, assessment in education in the future?

[00:19:11] Dan Schwartz: Yeah, this was, uh, you remember the MOOCs?

[00:19:14] Russ Altman: Yes.

[00:19:14] Dan Schwartz: Massively online, open courses. And, uh, you're hoping you have ten thousand students, and then you gotta grade the papers for ten thousand students. So what do you do? You give a multiple-choice tests, which can be machine coded, right? So, so I think that's always there. I'm going to take it a slightly different direction, which is, uh, I'm interacting with a computer system and while I'm interacting with it, it's, it can be constantly assessing in real time, right?

[00:19:41] And so there's a field that's sometimes called educational data mining or learning analytics. And there's thousands of people who are working on, how do I get informative signal out of students interactions. Like, are they trying to game the system? Are they reflecting? And so forth. So this is something the computer can do pretty well, right?

[00:20:02] It can sort of track what students are doing, assess, and then ideally deliver the right piece of instruction at the moment. So yours, you could use the assessments to give people a grade, but really the more important thing is, can you use the assessments to make instructional decisions? So I think this is a big area of advancement, but here's my concern.

[00:20:25] We've gotten very good at assessing things that are objectively right and wrong. Like did you remember the right word? Did you get two plus two correctly? For most of the things we care about now, they're like strategic and heuristic, which means it's not a guaranteed right answer. And so what you really want to do is assess students choices for what to do. So for example, uh, creativity, it's just for the most part, it's a large set of strategies. Right? There's a bunch of strategies that help you be creative. The question is, do the students choose to do that or do they take the safe route? 'Cause creativity is a risk, right? 'Cause you're not sure.

[00:21:02] So I think this is where the field needs to go. Is being willing to say that certain kinds of choices about learning are better than others. Uh, and it's a, it becomes more of an ethical question now. Instead of saying two plus two equals four, there's no ethics to it.

[00:21:16] Russ Altman: Are you going to be able to convince non educators who hold purse strings, let's call them the government, that these kinds of assessments are important and need to be included? Because my sense is that when it filters up to boards of education or elected leaders, a lot of that stuff goes out of the window. And they just want to know how good are they at reading comprehensive and can they do enough math to be competitive with, you know, country X?

[00:21:43] Dan Schwartz: Yeah. Yeah. So different assessments serve different purposes. Like the big year end tests that kids take, those aren't to inform the instruction of that child. They're not even for that teacher. They're for school districts to decide are our policies working. And so it's really a different kind of assessment than me as a teacher trying to decide what should I give the kid next. So I think it's going to vary. You know, the tough question for me is should you let the kid use ChatGPT during the test? Right?

[00:22:14] And we had this argument over calculators, right? And finally they came up with ways to ask questions where it was okay if the kids had calculators. Because the calculator was doing the routine stuff. And that's not really what you cared about. What you cared about was, could the kid be innovative? Could they take a, another, a second approach to solve a problem?

[00:22:34] Russ Altman: Yeah.

[00:22:34] Dan Schwartz: Things like that.

[00:22:34] Russ Altman: We, so I teach another class where it's a programming class, the students write programs, and we have switched, um, and we've actually downgraded the value. So as you know, very well, just as background, there is now an amazing, ChatGPT can also write computer code essentially. And so a lot of coding now is kind of done for you and you don't need to do it. We are trying to make sure that they understand the algorithms that we ask them to code. And so what we're doing is we're downgrading the amount of points you get for working code.

[00:23:04] You still get some, but we're upgrading the quiz about how the algorithm works. Do you understand exactly why this happened the way it did? Why is this data structure a good choice or a bad choice? And so it's forcing us, and you could have argued that we should have done this twenty years ago in the same class, but this is making it a more urgent issue, because if we don't, people can just get an automatic piece of code. They can run it. It'll work. They have no understanding of what happened. And so it's really a positive. It's putting more of a burden on us to figure out why the heck did we have them write this code in the first place?

[00:23:39] Dan Schwartz: No, this was my point. It makes you sort of rethink what is valuable to learn. And you stop doing what was easy to grade. So I have an interesting one. This is a little nerdy.

[00:23:51] Russ Altman: Okay. I love it. I love it.

[00:23:52] Dan Schwartz: I teach the intro PhD statistics course in education. And lots of students say, I took statistics, right? And I'm sort of like, well, that's great. Let me ask you one question. And I say, I'm going to email you a question and you'll have five minutes to respond. You let me know when you're ready for it. And I ask them, uh, this is just for you, Russ. But why is the tail of the T distribution fat in small sample sizes? And I, what I get back usually is because they're small sample sizes.

[00:24:24] Russ Altman: Right. Or because it's the T distribution.

[00:24:27] Dan Schwartz: Or it's, yes, even better. And then I come back and I sort of say, well, have you ever heard of the standard error? And I begin to get at the conceptual stuff, right? And, uh, I suspect if I gave it, uh, so there are ways to get conceptual questions that are really important. But you know, being able to prompt or write R code, you know, that's a good thing. You want them to learn the skills as well.

[00:24:50] Russ Altman: Exactly.

[00:24:51] Dan Schwartz: So I don't know, you know, when the calculator showed up, there's a big debate, right? What should students learn? Can they use the calculator? The apocryphal solution was you had to learn the regular math and the calculator now. You just had to learn twice as much. And so maybe that's what it's going to be.

[00:25:08] Russ Altman: And that's a very likely transitional strategy and then we'll see where we end up. Okay. In the final few minutes, I, this seems like it's unrelated to AI, but I bet it's not. You've done a lot of work on physical activity and learning. You've even been on a paper recently where you talk about having a walk during a teaching session and whether you get better outcomes than if you were just standing or sitting. So tell me about that interest and tell me if it has anything to do with today's topic.

[00:25:37] Dan Schwartz: I can make the bridge. I can do it, Russ. Right. So we did some studies. Um, I've done a lot of it. It's called embodiment where, yeah, there was, I got clued into this where, uh, I was asking people about why, about gears. And I say, you know, you have three gears in a line, and you turn the gear on the left clockwise. What does the gear on the right do? Far right. And I'd watch them, and they'd go like this with their hands. They'd model with their hands. And then I was sort of like, well, what's the basis of this? And I'd say well why? And they say because this one's turning that way that one, I go but why. And in the end, they just bottom out. They just show me their hands. They didn't say things like one molecule displaces another.

[00:26:20] Russ Altman: Right.

[00:26:21] Dan Schwartz: So that sort of clued me in.

[00:26:22] Russ Altman: This pinky is going up and this other pinky is going down.

[00:26:26] Dan Schwartz: Yes.

[00:26:26] Russ Altman: What don't you understand about that?

[00:26:28] Dan Schwartz: Pretty much. Well, it was nonverbal.

[00:26:31] Russ Altman: Yeah.

[00:26:31] Dan Schwartz: So we went on, you know, we discovered that the basis for negative numbers, right? Is actually perceptual symmetry. And we did some neuro stuff. And so the question is sort of how does this perceptual apparatus, which some people, we're just loaded with perception, right? The brain's just one giant perceiving. So how do you get that going? So part of the embodiment is my ability to take action, right? And so this is where we started, right? Right now, the AI feels very verbal, very abstract. Even the video generation, it's amazing, but it's pretty passive for me. So enter virtual worlds, they're still working on the form factor where I can move my hand in space.

[00:27:16] Russ Altman: Yeah.

[00:27:17] Dan Schwartz: And something will happen in the environment in response to that. You know, I think medicine is, you know, really been working on haptics so surgeons can practice. Uh, there was a great guy who made a virtual world for different heart congenital defects, and you could go in and practice surgery and see what would happen to the blood flow. So I think, uh, that embodiment where you get to bring all your senses to bear, it's not just words, but it's everything, can really do a lot for learning, for engagement, uh, not just physical skills.

[00:27:49] Russ Altman: So that's a challenge to, I'm hearing a challenge to AI, which is as an educator, you know that this physicality can be an critical part of learning. And by the way, would this be a surprise? I mean, we're, we've been on earth evolving for several hundred million years. And, uh, you would be surprised if our ability to manipulate and look at three dimensional situations wasn't critical to learning, and yet that's not what AI is doing right now. So this is a clear challenge to AI among other things.

[00:28:17] Dan Schwartz: Right. So, uh, I have a colleague, Renate Fruchter. And, uh, she teaches architecture, and she has students make a blueprint for the building, right? And then she feeds the blueprint to a CAD system that creates the building. She then takes the building and puts it into a physics engine, it can basically render the building and make walls so you can't move through them, and it has gravity and things like that.

[00:28:42] She then puts the, uh, original student who designed the building in a wheelchair and has them try to navigate through that environment. At which point they sort of understand, oh this is why you need so much space so they can turn around, so they can navigate near the door. I am sure that is an incredibly compelling experience that allows them to be generative about all their future designs.

[00:29:03] So yeah, this is a challenge and part of the co-mingling of the AI and the virtual worlds, I think this is a big challenge. It's computationally very heavy, but it will open the door for lots of ways of teaching that you just couldn't do before.

[00:29:17] Russ Altman: Thanks to Dan Schwartz. That was the future of educational technology.

[00:29:21] You've been listening to The Future of Everything and I'm Russ Altman. You know what? We have an archive with more than 250 back episodes of The Future of Everything. So you have instant access to a wide array of discussions that can keep you entertained and informed. Also, remember to rate, review, and follow. I care deeply about that request.

[00:29:41] And also, if you want to follow me, you can follow me on X @ @RBAltman, and you can follow Stanford Engineering @ StanfordENG.

Electric reactor could cut industrial emissions

James Landay: Paving a Path for Human-Centered Computing

Exploring space-related, human-centered design

Want a daily email of lesson plans that span all subjects and age groups?

Subjects all subjects all subjects the arts all the arts visual arts performing arts value of the arts back business & economics all business & economics global economics macroeconomics microeconomics personal finance business back design, engineering & technology all design, engineering & technology design engineering technology back health all health growth & development medical conditions consumer health public health nutrition physical fitness emotional health sex education back literature & language all literature & language literature linguistics writing/composition speaking back mathematics all mathematics algebra data analysis & probability geometry measurement numbers & operations back philosophy & religion all philosophy & religion philosophy religion back psychology all psychology history, approaches and methods biological bases of behavior consciousness, sensation and perception cognition and learning motivation and emotion developmental psychology personality psychological disorders and treatment social psychology back science & technology all science & technology earth and space science life sciences physical science environmental science nature of science back social studies all social studies anthropology area studies civics geography history media and journalism sociology back teaching & education all teaching & education education leadership education policy structure and function of schools teaching strategies back thinking & learning all thinking & learning attention and engagement memory critical thinking problem solving creativity collaboration information literacy organization and time management back, filter by none.

- Elementary/Primary

- Middle School/Lower Secondary

- High School/Upper Secondary

- College/University

- TED-Ed Animations

- TED Talk Lessons

- TED-Ed Best of Web

- Under 3 minutes

- Under 6 minutes

- Under 9 minutes

- Under 12 minutes

- Under 18 minutes

- Over 18 minutes

- Algerian Arabic

- Azerbaijani

- Cantonese (Hong Kong)

- Chinese (Hong Kong)

- Chinese (Singapore)

- Chinese (Taiwan)

- Chinese Simplified

- Chinese Traditional

- Chinese Traditional (Taiwan)

- Dutch (Belgium)

- Dutch (Netherlands)

- French (Canada)

- French (France)

- French (Switzerland)

- Kurdish (Central)

- Luxembourgish

- Persian (Afghanistan)

- Persian (Iran)

- Portuguese (Brazil)

- Portuguese (Portugal)

- Spanish (Argentina)

- Spanish (Latin America)

- Spanish (Mexico)

- Spanish (Spain)

- Spanish (United States)

- Western Frisian

sort by none

- Longest video

- Shortest video

- Most video views

- Least video views

- Most questions answered

- Least questions answered

Is this the most valuable thing in the ocean?

Lesson duration 05:37

53,124 Views

How do bulletproof vests work?

Lesson duration 05:16

161,899 Views

The most dangerous elements on the periodic table

Lesson duration 04:39

235,180 Views

What the oil industry doesn’t want you to know

Lesson duration 06:45

503,916 Views

Why are scientists shooting mushrooms into space?

Lesson duration 05:29

488,929 Views

The weirdest (and coolest) tongues in the animal kingdom

Lesson duration 05:17

171,649 Views

Why fish are better at breathing than you are

Lesson duration 05:21

370,398 Views

What happens in your body during a miscarriage?

Lesson duration 05:43

372,506 Views

Could we build a miniature sun on Earth?

Lesson duration 04:54

205,861 Views

These animals can hear everything

Lesson duration 05:26

191,226 Views

Can you transplant a head to another body?

Lesson duration 05:31

468,245 Views

How does an air conditioner actually work?

345,755 Views

Scientists are obsessed with this lake

Lesson duration 05:38

783,488 Views

Why do bugs swarm over water?

Lesson duration 05:13

337,143 Views

We need to track the world's water like we track the weather - Sonaar Luthra

Lesson duration 13:30

47,386 Views

The solar system is beige

Lesson duration 09:10

256,541 Views

What Earth in 2050 could look like

Lesson duration 05:00

629,872 Views

When ancient wisdom beats modern industry

Lesson duration 05:45

571,256 Views

Why does this flower smell like a dead body?

Lesson duration 05:28

298,140 Views

The real reason dodo birds went extinct

Lesson duration 05:32

515,327 Views

Would you raise the baby that ate your siblings?

535,624 Views

How much would it cost to buy the ocean?

Lesson duration 05:01

736,995 Views

Why is rice so popular?

Lesson duration 04:53

724,059 Views

Are pandas the most misunderstood animal?

Lesson duration 05:19

440,303 Views

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Learning

- Home ›

- Learning Technology ›

- AI for Teaching and Learning ›

AI for Teaching and Learning Video Series

Have questions about where to start with generative AI? The AI for Teaching and Learning video series is a great introduction.

Produced by Notre Dame Learning and the Office of Information Technology’s Teaching & Learning Technologies (TLT) team, these short videos aim to help faculty and the broader campus community get more familiar with generative AI in educational contexts.

The first two videos in the series are available now, and the rest will be published to this page early in the fall 2024 semester.

Opening the Dialogue on AI in Education

Ron Metoyer , Notre Dame’s vice president and associate provost for teaching and learning, introduces the AI for Teaching and Learning video series. He highlights how AI is changing education and encourages those who teach at Notre Dame to explore tools like ChatGPT, build their understanding of AI, and have open conversations with students about the technology’s pros and cons. Drawing a parallel between the current state of technological change and the experience of using web browsers for the first time in the 1990s, Metoyer expresses his confidence that educators can and will successfully navigate AI’s impact, now and in the future.

- AI for Teaching and Learning

- Establishing AI Policies for Your Course

- Building Critical AI Literacy

Intro to Generative AI

John Behrens , director of the Technology and Digital Studies Program in the College of Arts and Letters, provides an overview of generative AI, explaining its powerful capabilities in performing tasks once limited to humans, including text and image generation. He outlines five key concepts: AI’s extraordinary abilities, the variety of its outputs, associated challenges and risks, its impact on human tasks, and its evolving nature. Behrens emphasizes the importance of understanding AI’s limitations and the responsibility users must take when utilizing these systems.

- AI Overview and Definitions

- Five Things to Know About Generative AI & Technical Literacy

Intro to Text-to-Text Systems

This video will be added to this page in early September.

Generating Prompts

Navigating ai tools with integrity in academia, ai-assisted writing, best practices for assessment in the age of ai.

Become an Insider

Sign up today to receive premium content.

The Evolution of Technology in K–12 Classrooms: 1659 to Today

Alexander Huls is a Toronto-based writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times , Popular Mechanics , Esquire , The Atlantic and elsewhere.

In the 21st century, it can feel like advanced technology is changing the K–12 classroom in ways we’ve never seen before. But the truth is, technology and education have a long history of evolving together to dramatically change how students learn.

With more innovations surely headed our way, why not look back at how we got to where we are today, while looking forward to how educators can continue to integrate new technologies into their learning?

DISCOVER: Special education departments explore advanced tech in their classrooms.

Using Technology in the K–12 Classroom: A History

1659: magic lantern.

- Inventor: Christiaan Huygens

- A Brief History: An ancestor of the slide projector, the magic lantern projected glass slides with light from oil lamps or candles. In the 1680s, the technology was brought to the education space to show detailed anatomical illustrations, which were difficult to sketch on a chalkboard.

- Interesting Fact: Huygens initially regretted his creation, thinking it was too frivolous.

1795: Pencil

- Inventor: Nicolas-Jacques Conté

- A Brief History : Versions of the pencil can be traced back hundreds of years, but what’s considered the modern pencil is credited to Conté, a scientist in Napoleon Bonaparte’s army. It made its impact on the classroom, however, when it began to be mass produced in the 1900s.

- Interesting Fact: The Aztecs used a form of graphite pencil in the 13th century.

1801: Chalkboard

- Inventor: James Pillans

- A Brief History: Pillans — a headmaster at a high school in Edinburgh, Scotland — created the first front-of-class chalkboard, or “blackboard,” to better teach his students geography with large maps. Prior to his creation, educators worked with students on smaller, individual pieces of wood or slate. In the 1960s, the creation was upgraded to a green board, which became a familiar fixture in every classroom.

- Interesting Fact: Before chalkboards were commercially manufactured, some were made do-it-yourself-style with ingredients like pine board, egg whites and charred potatoes.

1888: Ballpoint Pen

- Inventory: John L. Loud

- A Brief History: John L. Loud invented and patented the first ballpoint pen after seeking to create a tool that could write on leather. It was not a commercial success. Fifty years later, following the lapse of Loud’s patent, Hungarian journalist László Bíró invented a pen with a quick-drying special ink that wouldn’t smear thanks to a rolling ball in its nib.

- Interesting Fact: When ballpoint pens debuted in the U.S., they were so popular that Gimbels, the department store selling them, made $81 million in today’s money within six months.

LEARN MORE: Logitech Pen works with Chromebooks to combine digital and physical learning.

1950s: Overhead Projector

- Inventor: Roger Appeldorn

- A Brief History: Overhead projects were used during World War II for mission briefings. However, 3M employee Appeldorn is credited with creating not only a projectable transparent film, but also the overhead projectors that would find a home in classrooms for decades.

- Interesting Fact: Appeldorn’s creation is the predecessor to today’s bright and efficient laser projectors .

1959: Photocopier

- Inventor: Chester Carlson

- A Brief History: Because of his arthritis, patent attorney and inventor Carlson wanted to create a less painful alternative to making carbon copies. Between 1938 and 1947, working with The Haloid Photographic Company, Carlson perfected the process of electrophotography, which led to development of the first photocopy machines.

- Interesting Fact: Haloid and Carlson named their photocopying process xerography, which means “dry writing” in Greek. Eventually, Haloid renamed its company (and its flagship product line) Xerox .

1967: Handheld Calculator

- Inventor: Texas Instruments

- A Brief History: As recounted in our history of the calculator , Texas Instruments made calculators portable with a device that weighed 45 ounces and featured a small keyboard with 18 keys and a visual display of 12 decimal digits.

- Interesting Fact: The original 1967 prototype of the device can be found in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History .

1981: The Osborne 1 Laptop

- Inventor: Adam Osborne, Lee Felsenstein

- A Brief History: Osborne, a computer book author, teamed up with computer engineer Felsenstein to create a portable computer that would appeal to general consumers. In the process, they provided the technological foundation that made modern one-to-one devices — like Chromebooks — a classroom staple.