Site Navigation

Smithsonian magazine.

Smithsonian magazine places a Smithsonian lens on the world, looking at the topics and subject matters researched, studied, and exhibited by the Smithsonian—science, history, art, popular culture and innovation—and chronicling them every day for our diverse readership.

Recent Releases

- Science / Nature

- Smithsonian

- Upcoming Titles

- Animals & Pets

- Antiques & Collectibles

- Art & Photography

- Auto & Cycles

- Business & Finance

- Computers & Electronics

- Entertainment & TV

- Fashion & Style

- Food & Cooking

- Health & Fitness

- Home & Gardening

- Local & Regional

- News & Politics

- Science & Nature

- Sports & Recreation

- Browse Magazines

- Shopping Cart

Reviews For Smithsonian Magazine

Smithsonian: a change of pace.

I started receiving Smithsonian Magazine about eight months ago. My husband and I both like the magazine, as well as the idea that our subscription fee supports the Smithsonian Institute and gives us a few member perks like a discount in the museum cafes if we ever happen to be in DC, and the Institute?s wonderful catalogue. Contents Smithsonian?s articles run the gamut from stories about the environment to archaeology to art and architecture to astronomy to entomology to history. Usually I have a magazine with me in the car so that I can read bits and pieces when I?m stopped in traffic; however, I never take Smithsonian. The articles are longer and more in depth and require my full attention--I can?t get away with a quick scan like I do with fashion magazines. I feel as though the content of Smithsonian is something to be savored as I read, ideas to ponder, information to digest and wonder at. I like the fact that I have to think on a deeper level with this magazine that wrests my attention from my latest homework assignment, the grocery list, the need to mop the kitchen. Smithsonian has a definite slant that favors exhibits in its own or affiliate museums, but given the quality of these exhibits, I won?t quibble about a little self-promotion. The magazine also delves into personal profiles, often linked with a current issue, such as a profile on Louis Pasteur who discovered the anthrax vaccine or a profile of Boss Tweed in conjunction with an article about the restoration of the New York City Courthouse that Tweed had built. I did not think that the articles on insects and animals would be nearly as interesting as they are. Smithsonian has made me a believer in the cuteness of Tasmanian devils, and that humans and animals can find a middle ground together as in an article about tigers in Nepal. I find most of the content genuinely informative, not just regurgitations of things I?ve heard before. The writers have a talent for finding new angles on current or older issues that I appreciate. Since I always find something to criticize, my biggest disappointment with Smithsonian lies in their guest columnists for Taking Issue. For this column, an editor or writer is given the upcoming issues articles to read before press and to comment on them. Most of these guest writers seem to find more things to criticize about the articles than they find good. I sincerely hope they?re not getting paid. Design The design of Smithsonian appears to be understated elegance. The pages of articles are uncluttered and clean looking. The regularly occurring features and columns are indicated by a small box with the title of the column and an appropriate graphic of some sort, but even these are unobtrusive. Articles often range from 6-9 pages, including illustrations, and are always completely together, never continued in some back page space. The best part of the design is the magazine?s use of photography to not only enhance and illustrate articles, but in many cases to make its own statement. A recent article about tree-climbing as a recreational sport not only had the coveted centerfold spot with two climbers rappelling down the trunk of huge California coast redwood, but also the cover photo of a mosquito-netted platform hanging from the silhouetted branch of a tree with the sunset behind it. One of the recurring columns involves old familiar photos, such as those that appeared on the cover of Life, and tracking down the people in the photos and where they are today as well as including details about the photographer who captured the ?indelible image.? Advertising Out of 110-115 pages in each issue, the magazine has 30-35 pages of advertising. Compared to other magazines to which I subscribe, this number is exceedingly low. Overall Smithsonian Magazine is, for me, a much-appreciated change of pace. It?s the kind of magazine that I curl up with on the couch, complete with cup of tea and fuzzy lap robe. The cat is optional. Recommended: Yes

Smithsonian Magazine--Homescholar's Resource

When I was responsible for the education of my homescholar, I subscribed to several quality magazines in order to expose her to a wide range of educated outlooks. Smithsonian Magazine was among the top in this category. If you're homeschooling, I highly recommend it. Monthly Smithsonian is a monthly magazine. Despite the frequency of the issues, each issue is vast in its range, and lushly illustrated. Many of the magazines that I selected were quarterly, which is actually to infrequent to consistently whet a homescholar's appetite for information. Accessible Some of the magazines that I subscribed to were more in the line of scholarly treatises, and were better suited to an academic audience. Not so the Smithsonian. The articles are written on a level that a tenth grader can understand. Although they are accessible, they don't talk down to the reader, and they do provide bibliographic links to further reading if you want to get more depth into a subject. Links to the Web Site Even then, they had links to their web site, where you could find and follow related threads. Now, the links are even more extensive, and the web site even more entertaining. I find this a great resource, especially if your goal is to use the magazine as a teaching tool. It's one thing to have a static tool, another to have a dynamic one which will lead to further exploration. Excellent content If you're using the magazine for teaching, you want the content to be the best possible. Smithsonian never let me down in this respect. The writing was always top-notch. The photography rivals that of National Geographic (another homescholar favorite). The bibliographic annotations are sometimes less extensive than I would like, but at least they exist. It will never write to sell a product (unlike so many magazines.) In short, the stuff between the covers is well worth reading. Varied The topics in the magazine are as varied as the Smithsonian's collection. Perfect for encouraging an inquiring mind. An issue can have an article on alternative energy, one on archeology, and one on an art technique, and the articles are placed so that they don't seem to clash with one another. (Which brings to mind the editing--which is skillful to the extreme.) Summing up I used this magazine as part of my approach to home schooling my daughter. It provided a wealth of well written, interesting articles which inspired, instructed, and excited. It was perfect for the goal at hand, which was to encourage my daughter to be a life long learner. If you've got a similar goal for yourself or for your children, then this is a good magazine to have around the house. I've never been to the museum or store, so can't speak to the usefulness of these membership benefits, but I recommend the magazine without reservation. Recommended: Yes

Art Gallery, News, Modern Lifestyle all in one Magazine

The Smithsonian What A Work of Art Pull out the scissors, the mattes and the nice oak frames and get ready for some excellent photography that you could cut right out and hang it on your wall. Two magazines have stunned the world with their photography that I have stumbled across, National Geographic Magazine and the Smithsonian. This review is based off previous subscriptions and readings and the Smithsonian October 2000 issue. As we glance the isles of newspapers and various magazines certain images catch the eye; I believe it is two things, sex appeal, which is highly exploited and bold simple eye catching covers. This issue of Smithsonian like so many others always seems to capture the eye, you must take a look or you will be wondering for days what that image was of. With one striking image, the magazine will intrigue its viewers to pick up the issue and glance the pages: 1. To find out what it is on the front page that captivates them. 2. To see if there is anything else that compares to its glamour. 3. Last off, to understand the content of the magazine. 1. The cover, ?Working in silver gilt and ivory, Belgian artist Charles van der Stappen sculpted this work, Sphinx mysterieux, in 1897. ?? This singular image captivated the viewer and brought him to attention. 2. As you open to the first two pages, what else, an advertisement of course! The next two pages is also an advertisement but its content relates to the next page which is not which brings the seamlessness appeal and shows the ingeniousness of the marketer. ?Make them feel at home and they won?t even notice that they were just sold to.? As they will find out there are many stunning articles, well written, and some nice works of art (pictures that is). 3. A magazine that sells art and modern life styles brings us closer to ourselves as we learn more about everything else. The Smithsonian pulled off the eye-catching theory and kept it very simple on the front cover. Within its advertising (where they make their money), it is seamless with content that can make one think that there wasn?t many ads at all, very good thought for consumers! The Content Some of the articles and type of material this magazine reviews are: ?The cat that walks by itself,? ?Kudzu: Love it ? or run,? ?Art Nouveau,? ?The Bozeman Trail,? and ?A lofty tribute to barns.? There are more of course, but for the sake of length and your time I will desist. As we look at the first article, ?The Cat that walks by itself,? we are first dazzled by Charles Bergman?s photography skills. The design template used to encase the article is also quite appealing with its borders and icons. It has a little blurb that reads, ?In Mexico?s Maya jungle, the survival of the jaguar hangs on radio collars, hounds and former hunters.? This along with the picture will lure you into reading the article or make you move on, to me it sings, READ now or be ignorant. In The End Some of the best written works ever, excellent examples of wonderful photography, seamless design with advertisements and other media within the magazine and wonderful templates. I would recommend obtaining a copy and seeing for yourself, I am sure that you won?t be sorry. I will obtain some more information and stick it here at the end as I update this article, a wonderful magazine that deserves even more speculation. ___Regards, JBHut Recommended: Yes

An old friend.

I've been a subscriber to Smithsonian for about eight years now. I don't see this changing anytime soon. This is general interest magazine with a slant towards science for the layperson. Regular features are: A Note from the Secretary, Around the Mall and Beyond, Phenomena, Comment & Notes, Points of Interest, The Object at Hand, Smithsonian Highlights, Book Reviews, and The Last Page. A Note from the Secretary is usually a description or sales pitch of some program that the Smithsonian is currently involved in. It reads very much like a memo from the board of directors of a large company and I guess that's what it is. I usually only skim this section because it is very dry and rarely has any connection to the contents of the magazine , although sometimes he will plug an article. Around the mall and Beyond is also mostly concerned with the business of the Smithsonian. There are occasional profiles of people connected to or employed by the various departments of the Smithsonian. Sometimes there will be an article about a particular exhibition or collection. Sometimes the connection is a little more tenuous though, as in a recent article on a mother-daughter book club formed by the associate director of the Smithsonian's Anacostia Museum and Center for African American History and Culture. The book club itself has no official connection to the Smithsonian Institute. Phenomena, Comment & Notes is generally a very brief (two or three pages) story on a professional scientist of one kind or another. It might be about an archaeologist's dig or a an astronomer's findings or some such thing. These are usually brief enough that they don't quite satisfy my curiosity. Although, they do consistently provoke my curiosity, and that is an accomplishment when compared to other magazines. Points of Interest is similar to Phenomena, Comment & Notes except that it's more pure Americana. It quite often has an approach like that of Charles' Kuralt's On The Road series. It is not uncommon for it to focus on a local festival like the Kerrville Folk Festival, or Marysville, Washington's Annual Strawberry Festival, which features an adult tricycle race. The Object at Hand is an interesting feature in that it usually gives a sort of case history of an object housed in one of the Smithsonian's museums. The range here is really staggering. From the actual Star Spangled banner, to the original MRI machine. I don't always find the subject enthralling, but on the whole this is a pleasant way to kill a few minutes and find out more about our national heritage. Smithsonian Highlights is a calendar of events which has a brief newsy article on a featured event and two or three pages of other events. I rarely read this because I live in Arkansas and don't figure to be traveling to the Smithsonian anytime soon. If I were planning a vacation to the area though I would find the information very helpful. The Book Reviews section features mostly nonfiction books on diverse topics like Mediterranean cuisine or the history of Basques, or tulips. There are also frequent reviews of memoirs by scientists and researchers of various types. I like this feature a lot not because I value the opinions so highly, but because I would otherwise never hear of most of these books. I'm a member of the Book of the Month Club and the Quality Paperback Book Club and frequently browse Barnes and Nobles website and they just don't highlight books like these. The reviews are typically of a length to be useful in making buying decisions. The Last Page is my least favorite feature as it is a purportedly humorous slice of life essay and i have a very low tolerance for that sort of thing. If you like Dave Barry and Lewis Grizzard, then this is probably right up your alley. If they set your teeth on edge, don't bother with this stuff. I must say however that it is a very small part of the magazine and I can live with it even if I only rarely find it amusing. In addition to these regular features each issue contains around five long in depth articles on a number of diverse subjects. Reappraisals of various artists seem to be recurring more and more as the years go past. I can remember seeing articles on Winslow Homer, Jasper Johns, and Vermeer. I find the biographical information highly informative and especially enjoy seeing works placed in their historical context. The features on artists have good layouts without a lot of distracting interplay between text and art. They sometimes begin an article with a full page spread that has text overlaying art but rarely do they intrude further on the graphics. I have a minor quibble though about their selection of paintings to reproduce. Very often the article will go on and on about a particular painting and I'll flip around and try to find it. As likely as not I won't find it because it simply isn't there. I find that aggravating. Otherwise these are articles that I look forward to. Another frequent topic over the last several years is alternative farming. I can remember articles about non-chemical methods of pest control such as infrared lights, ultrasonic sounds, and ladybugs. In addition there are also frequent photo essays and what not that I find a lot of pleasure in. Typically the magazine has outstanding production values through out, from choice of typeface to page design, but these sections are where they really go all out to make a beautiful presentation. It's hard to beat nature photography and a recent feature on insects called "Supermodels with Six Legs" is a perfect example of what I'm talking about. There is a photo of a butterfly that gets its iridescent blue color not from pigment but from scales on its wings that reflect only blue light. The thing I like most about Smithsonian is that it is imminently re-readable. It contains enough technical information that I'm unlikely to absorb it all. Consequently, if I pick up this months's issue next year, I'll probably enjoy most of it all over again. This is one of the few magazines that I actually save. I have every issue going back eight years and I've moved during that period. Anything that stays with me through packing and unpacking is a member of the family. I highly recommend a subscription to Smithsonian as a gift for family members. It is full of eclectic articles and gorgeous photography. Smithsonian doesn't always fascinate me, but it always interests me. Recommended: Yes

Conduit of the Wonders that make life worth living

So my subscription started a couple years ago, when upon spending a summer in the capital, (as a Whitehouse intern of all things), I had the immense guilty pleasure of spending hours in the Smithsonian museums, from the standards like American History and Air and Space, to the more obscure ones like National Building Museum, and the Newseum (that last one is not part of the smithsonian, but this small one across the bridge in virginia was my favorite by far, so I thought I should plug it). The pleasure came from having access to a world of knowledge that just blows the mind. The guilt comes with pride of being in a country that provides this for free. I spent the summer before in Paris, where access to their treasures came at significant price (unless you knew the tricks, but that's again beside the point). So I became a member, to thank the Smithsonian for their wonderful the museums. The magazine was a wonderful surprise. In it, I found the same love of knowledge. The same delight in the little things that make the world such a great place to live. And it comes every month to my door step. With reporting on the same multitudes of topics that you find in the museums, it is always a pleasure to read. It goes out of its way to find the quirky and the eccentric that other news sources would not pick up on, from the sheer linguphilia of a.w.a.d (a word a day), to the creation of a 20th century illuminated bible, to the latest advances in physics, to the great american side-show from small-town USA. The Smithsonian Magazine constantly fascinates and informs and delights. It is something I eagerly look forward to each month. (It also happens to be one of the visually stunningly beautiful magazines I subscribe to, or even see. It easily gives National geographic a run for its money.) Recommended: Yes

A nice little gem of a magazine

The Smithsonian magazine does a few things. One, it contains many features, similar to National Geographic, about our world, the environment, people, places, and events (both current and historical). Yet, the Smithsonian goes beyond that. A part of the Smithsonian's charm is that many of the features in the magazine could also easily be features in the Smithsonian museums and in fact some are related to the exhibits (see below). The magazine is published monthly and I await each issue eagerly. Being a teacher I also find that it is handy to use in the classroom. Students can easily read up on new developments, see some gorgeous pictures and hopefully learn something in the process. The February 2008 (most recent) issue has such features as the Parthenon, finding lost World War II art, and an article on the African-American history inaugural exhibition. This is one particular issue that I will use in my classrooms again and again. The Smithsonian is printed in the standard magazine size (8 1/2 x 11) and format. Each issue is just over 100 pages in length with a good mixture of main articles, editorial, letters to the editor, and small feature-ettes. Since this was a gift subscription I am unsure of the cost and there is not a cover price printed on the front. For people looking to an alternative to the National Geographic magazine or as a supplement to that, look towards the Smithsonian. It is a nice little gem in a market that many don’t look to beyond the small yellow magazine. This was given to me as a gift and I would gladly keep the subscription going for a long time to come. Recommended: Yes

From our Nation's Capital...

For an all-around informative and interesting magazine, Smithsonian is one of the best you'll find. Often times it is classified as a "general interest," magazine, leading some to think it's probably boring or has no theme. It's only general because it covers so much, you just can't put neatly into one category. Americana probably describes it best, since it is the magazine of America's premier museum, the Smithsonian Institute, and also tells stories that make America, America. The magazine usually covers art, history, people, and events. In keeping up with our rapid approach to the 21st century it keeps up with the times by covering an occasional environmental success/failure story. It features story about technology and how it affects our day-to-day lives. Sports, nature, cities, have all been covered. There are profiles of artists, writers, and performers of the past. There is a book review section and a schedule of Smithsonian's exhibits. One of my favorite sections is "The Object at Hand," which features some curiosity or ordinary thing. A couple of recent examples featured such diverse subjects as brazil nuts and lighthouse lenses. Some other recent stories that I enjoyed include: the history of salt, the story of Pocahontas, time pieces, the power of turquoise, checkers players, tracking a hurricane, the piranha, and the dairy industry. You can see that a wide variety of subjects are covered. This is not a news magazine. It has no political agenda. It is fun, it is educational, it is entertaining. You will learn something you never knew you wanted to know. Recommended: Yes

Like a mini-museum.

I love Smithsonian magazine. Every issue is guaranteed to include at least one article that I will find interesting, and usually many more than that. Because this is the SMITHSONIAN magazine, it is much like the Institution that publishes it. All topics are covered with the same care and there are humorous as well as serious articles. I've read about clocks and watches, Swiss Army Knives, painters and photographers, countless products, inventors, designers, and other notable people, places and, yes, things. There is always something for anybody in each issue and it is an excellent family magazine. One thing that will appeal to kids is the fact that they do cover light hearted topics and many of the articles are 4 - 5 pages, in addition to the longer more in-depth essays. The articles are educational as well as being entertaining, and it's a good way to get started learning about some topic, without getting too much info at one time. The reader gets a taste of many different topics. It has the one problem that so many magazines have and which we all just have to accept. To many of those little subscription cards sticking out between the pages that make it hard to just flip through. The pages always fall open to those little cards. Still, that's not much of a problem and more than compensated for by the rest of the magazine. Recommended: Yes

Big, Glossy & Great

I'm a sucker for the big glossy magazines I grew up with, like Life, National Geographic and Smithsonian. You know, the kind you never throw away and make a library out of. These are more like books than magazines. I originally ordered it for my daughter hoping to get her interested in a variety of topics, but I think I'm the one who reads and re-reads it the most. I have quite a collection of them, and many times return to the pile, as they are an excellent resource material. And yes, my daughter does on occasion use information in for them for school projects. These magazines are always fresh with new ideas, new discoveries and re-investigations of old ideas. They have a host of people who contribute to this magazine, and the perspective of the subjects changes from month to month. The topics are far ranging, from archeology, science, gemology, nature, space, history and people. I especially like the articles on Smithsonian history and current exhibit write ups. I can hardly wait to get to the "Castle" to see some of these wonderful things myself. Recommended: Yes

In every issue of the Smithsonian the reader is taken on different journeys to all the corners of this wonderful world we live in, introduced to cultures, both primitive and modern, whether it be life as a human, animal or plant. The readers brain is fed interesting and informative data and may even spark an interest in learning more on the subjects introduced. This magazine is a must have for all coffee tables, medical offices or road trip goodie bags. I'm sure that in time, I will have a room full of Smithsonian magazines to be used for reference material, dreaming of journeys to far away places, imagining myself as royalty or a famous botanist or showing my future grandchildren all the exciting wonders of this world. Recommended: Yes

Skip to Main Content

Natural History

Write a Review

You must have an account and be logged in to write a review.

- Create New Wish List

Description

The Smithsonian's Natural History: The Ultimate Visual Guide to Everything on Earth is a monumental and beautiful exploration of Earth's wildlife and natural history—its rocks, minerals, animals, plants, fungi, and microorganisms. In the 11 years since this book was released, thousands of new species have been identified, and new revelations have redrawn the tree of life. Already featuring galleries of more than 5,000 species, Natural History now includes discoveries such as the olinguito (the "kitty bear" of the Andean cloud forest) and the painted mannakin of Peru. It takes advantage of the first living observations of the giant squid and the deep-sea anglerfish. And it has reorganized the groups of living things to reflect the latest scientific understanding. All this ensures that this, the only book to offer a complete visual survey of all kingdoms of life, remains the benchmark of illustrated natural history references.

Museum Story

The Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History is the world's preeminent museum and research complex dedicated to inspiring curiosity, discovery, and learning about the natural world through its unparalleled research, collections, exhibitions and educational outreach programs.

- 11.06" x 9.25"

You May Also Like

Customer Reviews

Average Rating:

Based on 2 Reviews

January 19, 2022

My 10-year-old grandson went right to the minerals and rocks and was in awe for quite some time - there were many related pages. An amazing number and quality of life and geologic depictions with tantalizing descriptions. Stimulating to both mind and soul.

Massimo Podrecca

December 23, 2021

Beautiful and informative.

Welcome to Smithsonian.com, home of Smithsonian products and services. Visit our main website at si.edu to plan a visit or explore our collections and resources.

Where Will We See You Next?

Download our new catalog to find inspiration for your next journey!

You Make a Difference 100% of our proceeds support the Smithsonian mission.

Smithsonian Store

New arrivals.

Best Sellers

Science & Activity Kits

Learn what’s new in history, science, archaeology, art and travel with daily articles from Smithsonian magazine’s writers and editors.

Subscribe to the Magazine

Only $19.99 for 1 year

A journey into the Smithsonian collections like never before.

Award-winning programming exploring science, nature, history, and pop culture.

Smithsonian Theaters

Visit the Largest IMAX Screen in the Region

Airbus imax theater.

Plan Your Visit to the All New Planetarium

8k ultra hd 70 foot dome.

Smithsonian Theaters presents

Sci-fi sundays.

Deep Sky: An IMAX Original Documentary

Now playing.

Travel the world with Smithsonian. Enrichment-filled journeys on all 7 continents!

Smithsonian Journeys

A World of Possibilities

Request your free catalog now!

Be the First To Know

Learn about new tours, free webinars, and more

Find Your Perfect Journey

Discover a trip to match your interests!

Plan a visit to the Smithsonian

Visit Museums, Galleries, & the Zoo

More from the Smithsonian

At the Smithsonian

Explore dining, shopping, theater and interactive activities while you are visiting our locations

African American History and Culture Museum

Store locations, dining locations.

Sweet Home Café Lower Level

African Art Museum

Store location, air & space museum (washington, dc).

Ground floor

IMAX Location

Air & space museum (udvar-hazy).

Ground Level

Lower Level

American Art Museum

First Floor

Courtyard Café Kogod Courtyard

American History Museum

Main Museum Store First floor

Mall Museum Store Second floor

The Price of Freedom Store Third Floor

Eat at America's Table Ground Level

LeRoy Neiman Jazz Café First Floor

Theater Location

Warner Bros. Theater First floor

Other Fun Things

Ride Simulators Lower Level

Penny Smashers First Floor

American Indian Museum (Washington, DC)

Roanoke Museum Store Second Level

Mitsitam Café

Mitsitam Espresso Coffee Bar

American Indian Museum (New York City)

Mili Kàpi Cafe Level 2

Asian Art Museum

Café Sackler Pavilion

Cooper Hewitt Design Museum (NYC)

Tarallucci e Vino Café Ground Floor

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Dolcezza Coffee & Gelato Ground Level

Natural History Museum

Gem and Mineral Store Second Floor

Gallery & Family Store Ground Floor

Mammal Store First Floor

Express Kiosk Second Floor

Ocean Terrace Café First Floor

Atrium Café Ground Floor

Butterfly Pavilion

Second Floor

National Zoo

Visitor Center

Panda Plaza

Great Cats Gift Shop

Panda Overlook Cafe (seasonal)

Hot Dog Diner (seasonal)

Seal Rock Cafe (seasonal)

Playground: Me and the Bee

Conservation Carousel

Portrait Gallery

Postal museum, renwick gallery, smithsonian castle.

Castle Great Hall - Main Floor

Castle Café Main Floor

© Copyright 2024 Smithsonian Enterprises. Privacy Statement Cookie Policy Terms of Use Smithsonian Institution

- Kindle Store

- Kindle Newsstand

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

Read with Kindle Unlimited $0.00

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Smithsonian Magazine Kindle Edition

| New from | Used from |

| Kindle | |||

- Kindle $0.00

Get this magazine and more with Kindle Unlimited. Enjoy a selection of magazines, newspapers, popular series, best sellers and audiobooks for one low price. Explore Kindle Unlimited

- Kindle (5th Generation)

- Kindle Keyboard

- Kindle (2nd Generation)

- Kindle (1st Generation)

- Kindle Paperwhite

- Kindle Paperwhite (5th Generation)

- Kindle Touch

- Kindle Voyage

- Kindle Fire HDX 8.9''

- Kindle Fire HDX

- Kindle Fire HD (3rd Generation)

- Fire HDX 8.9 Tablet

- Fire HD 7 Tablet

- Fire HD 6 Tablet

- Kindle Fire HD 8.9"

- Kindle Fire HD(1st Generation)

- Kindle Fire(2nd Generation)

- Kindle Fire(1st Generation)

- Kindle for Android Phones redding_periodical_version_info

- Kindle for Android Tablets whiskeytown_periodical_version_info

- Kindle for iPhone iphone_periodical_version_info

- Kindle for iPod Touch ipod_periodical_version_info

- Kindle for iPad ipad_periodical_version_info

- mac_periodical_version_info

Enter your mobile number or email address below and we'll send you a link to download the free Kindle App. Then you can start reading Kindle magazines on your smartphone or tablet - no Kindle device required.

To get the free app, enter your mobile phone number.

Editorial Reviews

This magazine chronicles the arts, environment, sciences and popular culture of the times. It is edited for modern, well-rounded individuals with diverse, general interests. Each subscription includes a membership to the Smithsonian Institution which provides special discounts at Smithsonian gift shops, world travel opportunities through Smithsonian study tours and information on all Smithsonian events in any area. Kindle Magazines are fully downloaded onto your Kindle so you can read them even when you're not wirelessly connected.This magazine does not necessarily reflect the full print content of the publication.

Product details

- Language : English

- Publication date : December 18, 2023

- Date First Available : March 25, 2011

- Publisher : Smithsonian (December 18, 2023)

- ASIN : B004T1Z7PE

- #10 in Entertainment & Pop Culture eMagazines

Customers who bought this item also bought

Related books

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 71% 13% 8% 4% 4% 71%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 71% 13% 8% 4% 4% 13%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 71% 13% 8% 4% 4% 8%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 71% 13% 8% 4% 4% 4%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 71% 13% 8% 4% 4% 4%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

Worked in the beginning, not anymore

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

REVIEW: The Hod King by Josiah Bancroft

The Hod King is the third volume in Josiah Bancroft’s masterful Books of Babel tetralogy, combining the best features of the first two books of the series, Senlin Ascends and Arm of the Sphinx , while bringing new emotional depth to this tragic story.  The Tower of Babel is an overwhelmingly massive structure, taller than any modern skyscraper. The building is divided into layers called “ringdoms,” each with its own peculiar culture and politics. In the first book, Senlin Ascends , our hero struggles to make his way upward through the ringdoms, believing that he will find his wife at the Tower’s famous baths. Senlin must overcome a series of Kafkaesque absurdities at each level to continue his ascent. By the second book, Arm of the Sphinx , the previously naïve Senlin is determined to take charge of his destiny, assembling a ragtag crew of makeshift pirates, traveling through this steampunk world on a stolen airship. The Hod King strikes just the right balance between the Kafka-inspired absurdity of Senlin Ascends and the multi-point-of-view adventures of Arm of the Sphinx . More importantly, The Hod King deepens the emotional impact of the story as we finally encounter Marya. A year has passed since the newlyweds were first separated outside the Tower. Senlin’s bride may not be as he remembers, and the question arises of whether she actually wants to be “saved.” Senlin’s personal struggles are set against the backdrop of the greater mysteries of the Tower, including those of the enigmatic Sphinx and the Hod King. As unlikely as it seems, Senlin’s journey may be inexorably linked with the fate of the Tower itself. Among the many brilliant aspects of the Books of Babel, I am particularly impressed with Josiah Bancroft’s use of theatrical motifs to deepen the story. The author skillfully hones his theatre-related imagery in The Hod King , driving home the theme of finding our true selves behind the many literal and figurative masks that we wear throughout our lives. The Hod King is arguably the best volume in Josiah Bancroft’s Books of Babel series. Grimdark readers will especially love the complexity of this dark world, as well as Bancroft’s consistently outstanding characterization. The tetralogy concludes with The Fall of Babel . Read The Hod King by Josiah Bancroft John Mauro lives in a world of glass amongst the hills of central Pennsylvania. When not indulging in his passion for literature or enjoying time with family, John is training the next generation of materials scientists at Penn State University, where he teaches glass science and materials kinetics. John also loves cooking international cuisine and kayaking the beautiful Finger Lakes region of upstate New York.  You may also like REVIEW: A Good Deliverance by Toby ClementsAugust 31, 2024  REVIEW: Order of the Shadow Dragon by Steven McKinnonAugust 29, 2024  REVIEW: A Savage Moon by Theodore BrunAugust 28, 2024 Grimdark Magazine  TURN YOUR INBOX INTO A GRIMBOXQuick links.

GET GRIT IN YOUR INBOXStay on top of all the latest book releases and discussions—join our mailing list. Get a free magazineJoin our mailing list for a free issue, the latest book releases, and grimdark discussions. © 2024 Grimdark Magazine | Website built with ♥ by Acid Media

Pedro Almodóvar’s The Room Next Door Finds Joy Even as It Stares Down Death F or those who have been following his career from the start , the idea of Pedro Almodóvar’s growing older—and increasingly using his films to reflect on illness and death, or at least just the inevitable slowdown that comes for most of us—is a bitter pill. None of us relishes thinking about our own mortality. But sometimes it feels worse to think about losing an artist we love, especially one as vital and ageless as Almodóvar. One of his finest, most moving works , 2019’s Pain and Glory , reckoned with the nuisances of aging, as well as the trauma of being an artist in crisis. But the director’s first English-language movie, The Room Next Door —playing in competition here at the Venice Film Festival —delves even further into the murky waters of our feelings about death. Julianne Moore and Tilda Swinton star as Ingrid and Martha, old friends who bonded in New York in the 1980s but who have been out of touch for a long time. They reconnect when Ingrid learns that Martha is being treated for cancer, and their rekindled friendship veers into complicated territory. The Room Next Door is an adaptation, written by Almodóvar himself, of Sigrid Nunez’s 2020 novel What Are You Going Through, and at first the movie’s tone feels a little strange, untethered to any easily identifiable genre. It’s a story about friendship, clearly, but also about a woman facing a solitary and difficult choice. The dialogue sometimes feels flat and wooden. At one point Martha reminds Ingrid of the lover they’d once shared, though technically, he’d drifted toward Ingrid after he and Martha had broken up. “He was a passionate and enthusiastic lover, and I hope he was for you too,” Martha says, and though she means it, the line hits with a thud. And even if Almodóvar goes for a laugh here or there, overall the tone of The Room Next Door is a bit somber—almost like a black comedy, but not quite. Read more: The Best New Movies of August 2024 And yet, by the end, something almost mystical has happened: the movie’s final moments usher in a kind of twilight, a state of grace that you don't see coming. Ingrid, a successful writer, first hears of Martha’s illness at a signing event for her most recent book. Though she hasn’t seen Martha in years, she dutifully visits her at the hospital where she’s being treated. They catch up quickly: Martha, who worked for years as a war correspondent, has a daughter, Michelle, born when she was still a teenager. Michelle has accused Martha of being a bad mother, and is particularly resentful that she has withheld information about Michelle’s father. Martha denies none of it. Still, she wishes she and Michelle were closer, and her grave illness—she has stage three cervical cancer—puts a new spin on things. She’s hoping the experimental treatment she’s been receiving will work; she’s devastated when she learns that it isn’t. And so she procures for herself— on the Dark Web , she tells Ingrid, almost in a whisper—an illegal pill that will put an end to all of it. She has worked out all the details: she’ll leave a note for the police, explaining that she alone is responsible for her fate. And she doesn’t want a stranger discovering her body. When she decides the time is right, what she wants, she says, is to know that a friend is in “the room next door.” She has decided Ingrid will be that friend, though Ingrid, who has a quivering, electric, nervous quality beneath her veneer of self-confidence, at first wants no part of it. Ingrid has re-entered Martha’s life in a whirlwind of good intentions. But does she really want to help Martha die ? She’s not so sure. (She has also, unbeknownst to Martha, reconnected platonically with that old shared boyfriend; his name is Damian, and he’s played, with a kind of droll swagger, by John Turturro .) Ingrid and Martha’s rekindled friendship seems shaky at first. Martha has decided that she doesn’t want to die in her own smartly appointed Fifth Avenue apartment. So she books a tony modern country house somewhere near Woodstock—it has amazing views of nature that only money can buy—and she and Ingrid pack their bags and drive up. Almost as soon as they arrive, Martha panics. She’s forgotten the precious euthanasia pill; she insists that she and Ingrid drive back to Manhattan immediately to get it. Ingrid barely hides her annoyance; how did she get into this situation, anyway? Briefly, the movie tap-dances into screwball-comedy territory. It would all be very funny, if Martha weren’t suffering so much. But The Room Next Door is on its way to place of tenderness and accord—we just can’t see it yet. At one point, Martha rages against her illness, but also against the cheap bromides people use when they talk about cancer, often referring to treating it as a “battle,” a test of strength that’s also somehow a measure of virtue. “If you lose, well, maybe you just didn’t fight hard enough,” she says bitterly. No wonder she wants to write the ending to her own story: “I think I deserve a good death." Swinton’s Martha is frail but still, somehow, has the vitality of a pale blond moon; Moore , with her burgundy-red hair and intense, searching eyes, brings a rush of color into her life. They talk about books, art, movies: Martha has been thinking about the closing lines of James Joyce’s The Dead, so they spend an evening watching John Huston’s gorgeous 1987 version on the rental's DVD player. They make conversation about little things: a recent book that interests them both, Roger Lewis’ Erotic Vagrancy, about the partnership of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton ; the reproduction of Edward Hopper’s People in the Sun that hangs in the rented house’s hallway. Their idle conversations are a kind of casual nourishment. It's a pleasure to watch these two actors together. Martha and Ingrid riff against and annoy each another until suddenly, they find their groove, and the movie does too. Shot by Eduard Grau, the film has a rich, handsome look, and the production and costume design are characteristically Almodóvarian in their jubilance. The sets include stunningly orchestrated combinations of pickle green and tomato red; there are artfully shabby velvet couches and walls casually sponged with cobalt-blue paint. (The production designer is Inbal Weinberg; the costumes are by Bina Daigeler.) It’s all marvelous to look at, but this kind of visual splendor might evoke some guilt, too. Is it wrong to be ogling Martha’s fabulous, mega-chunky color-blocked knit pullover when you know, as she does, that death is just one little pill away? But as the story wheels forward, it becomes clear that the joy Almodóvar takes in colors and patterns isn’t beside the point; it is the point. He’s created a kind of cocoon world for these two women, as they embark together on a bumpy adventure. And that’s how he beckons us into their story. Lime and lilac, scarlet and saffron: he knows what colors work together, which combinations will surprise us or offer a jolt of delight. The colors of The Room Next Door are its secret message, a language of pleasure and beauty that reminds us how great it is to be alive. If it’s possible to make a joyful movie about death, Almodóvar has just done it. More Must-Reads from TIME

Contact us at [email protected]

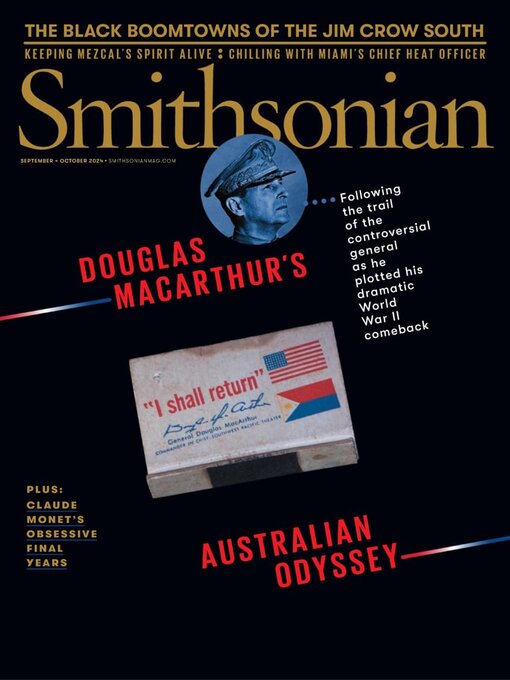

Smithsonian Magazine Description OverDrive Magazine

Culture & Literature Science Frequency: Every other month Pages: 144 Publisher: Smithsonian Institute Edition: September-October 2024 OverDrive Magazine Release date: August 30, 2024