- Privacy Policy

Home » Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Validity is a fundamental concept in research, referring to the extent to which a test, measurement, or study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure. Ensuring validity is crucial as it determines the trustworthiness and credibility of the research findings.

Research Validity

Research validity pertains to the accuracy and truthfulness of the research. It examines whether the research truly measures what it claims to measure. Without validity, research results can be misleading or erroneous, leading to incorrect conclusions and potentially flawed applications.

How to Ensure Validity in Research

Ensuring validity in research involves several strategies:

- Clear Operational Definitions : Define variables clearly and precisely.

- Use of Reliable Instruments : Employ measurement tools that have been tested for reliability.

- Pilot Testing : Conduct preliminary studies to refine the research design and instruments.

- Triangulation : Use multiple methods or sources to cross-verify results.

- Control Variables : Control extraneous variables that might influence the outcomes.

Types of Validity

Validity is categorized into several types, each addressing different aspects of measurement accuracy.

Internal Validity

Internal validity refers to the degree to which the results of a study can be attributed to the treatments or interventions rather than other factors. It is about ensuring that the study is free from confounding variables that could affect the outcome.

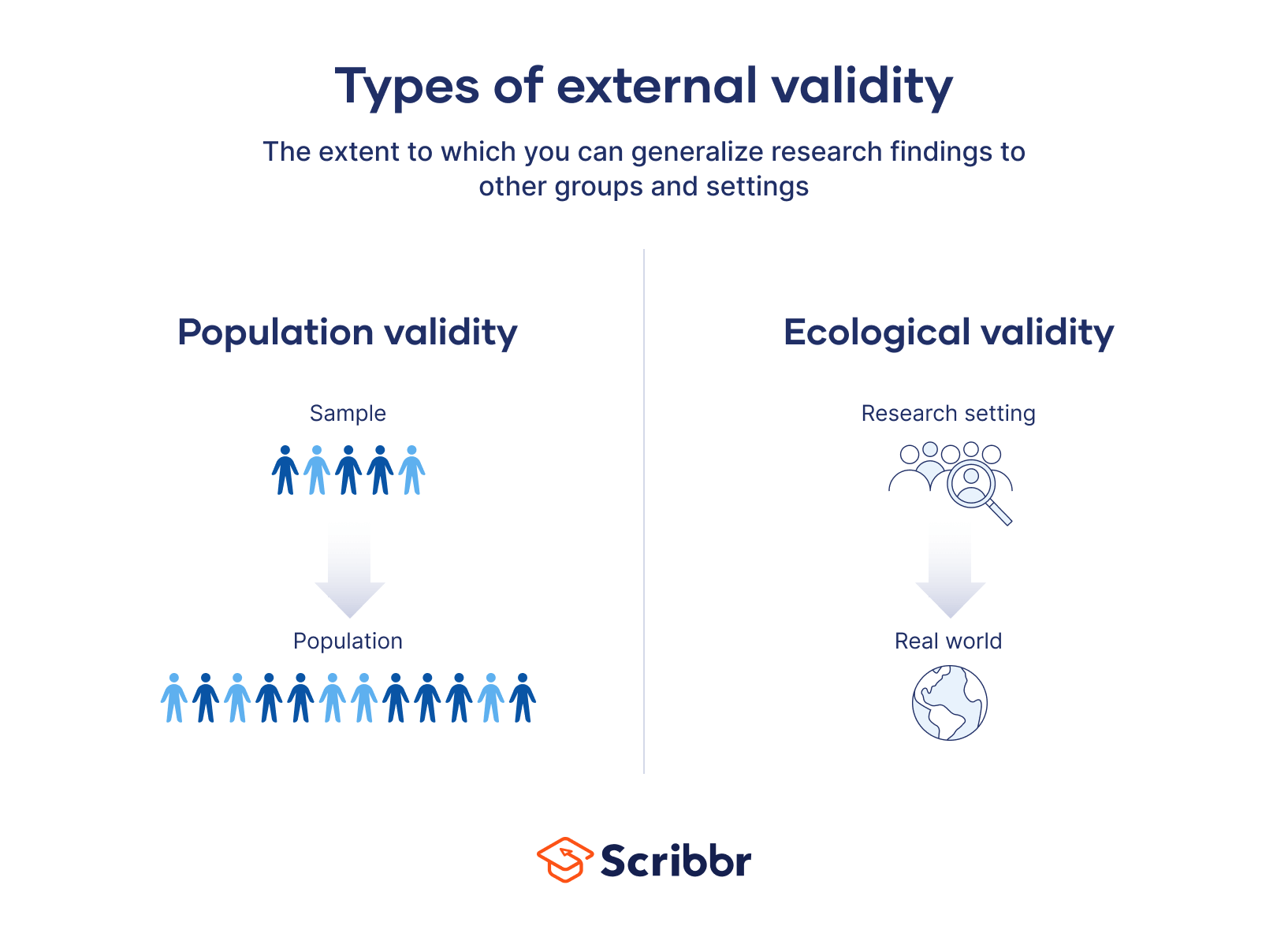

External Validity

External validity concerns the extent to which the research findings can be generalized to other settings, populations, or times. High external validity means the results are applicable beyond the specific context of the study.

Construct Validity

Construct validity evaluates whether a test or instrument measures the theoretical construct it is intended to measure. It involves ensuring that the test is truly assessing the concept it claims to represent.

Content Validity

Content validity examines whether a test covers the entire range of the concept being measured. It ensures that the test items represent all facets of the concept.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity assesses how well one measure predicts an outcome based on another measure. It is divided into two types:

- Predictive Validity : How well a test predicts future performance.

- Concurrent Validity : How well a test correlates with a currently existing measure.

Face Validity

Face validity refers to the extent to which a test appears to measure what it is supposed to measure, based on superficial inspection. While it is the least scientific measure of validity, it is important for ensuring that stakeholders believe in the test’s relevance.

Importance of Validity

Validity is crucial because it directly affects the credibility of research findings. Valid results ensure that conclusions drawn from research are accurate and can be trusted. This, in turn, influences the decisions and policies based on the research.

Examples of Validity

- Internal Validity : A randomized controlled trial (RCT) where the random assignment of participants helps eliminate biases.

- External Validity : A study on educational interventions that can be applied to different schools across various regions.

- Construct Validity : A psychological test that accurately measures depression levels.

- Content Validity : An exam that covers all topics taught in a course.

- Criterion Validity : A job performance test that predicts future job success.

Where to Write About Validity in A Thesis

In a thesis, the methodology section should include discussions about validity. Here, you explain how you ensured the validity of your research instruments and design. Additionally, you may discuss validity in the results section, interpreting how the validity of your measurements affects your findings.

Applications of Validity

Validity has wide applications across various fields:

- Education : Ensuring assessments accurately measure student learning.

- Psychology : Developing tests that correctly diagnose mental health conditions.

- Market Research : Creating surveys that accurately capture consumer preferences.

Limitations of Validity

While ensuring validity is essential, it has its limitations:

- Complexity : Achieving high validity can be complex and resource-intensive.

- Context-Specific : Some validity types may not be universally applicable across all contexts.

- Subjectivity : Certain types of validity, like face validity, involve subjective judgments.

By understanding and addressing these aspects of validity, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their studies, leading to more reliable and actionable results.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

External Validity – Threats, Examples and Types

Internal Consistency Reliability – Methods...

Split-Half Reliability – Methods, Examples and...

Criterion Validity – Methods, Examples and...

Construct Validity – Types, Threats and Examples

Internal Validity – Threats, Examples and Guide

Validity in research: a guide to measuring the right things

Last updated

27 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Validity is necessary for all types of studies ranging from market validation of a business or product idea to the effectiveness of medical trials and procedures. So, how can you determine whether your research is valid? This guide can help you understand what validity is, the types of validity in research, and the factors that affect research validity.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is validity?

In the most basic sense, validity is the quality of being based on truth or reason. Valid research strives to eliminate the effects of unrelated information and the circumstances under which evidence is collected.

Validity in research is the ability to conduct an accurate study with the right tools and conditions to yield acceptable and reliable data that can be reproduced. Researchers rely on carefully calibrated tools for precise measurements. However, collecting accurate information can be more of a challenge.

Studies must be conducted in environments that don't sway the results to achieve and maintain validity. They can be compromised by asking the wrong questions or relying on limited data.

Why is validity important in research?

Research is used to improve life for humans. Every product and discovery, from innovative medical breakthroughs to advanced new products, depends on accurate research to be dependable. Without it, the results couldn't be trusted, and products would likely fail. Businesses would lose money, and patients couldn't rely on medical treatments.

While wasting money on a lousy product is a concern, lack of validity paints a much grimmer picture in the medical field or producing automobiles and airplanes, for example. Whether you're launching an exciting new product or conducting scientific research, validity can determine success and failure.

- What is reliability?

Reliability is the ability of a method to yield consistency. If the same result can be consistently achieved by using the same method to measure something, the measurement method is said to be reliable. For example, a thermometer that shows the same temperatures each time in a controlled environment is reliable.

While high reliability is a part of measuring validity, it's only part of the puzzle. If the reliable thermometer hasn't been properly calibrated and reliably measures temperatures two degrees too high, it doesn't provide a valid (accurate) measure of temperature.

Similarly, if a researcher uses a thermometer to measure weight, the results won't be accurate because it's the wrong tool for the job.

- How are reliability and validity assessed?

While measuring reliability is a part of measuring validity, there are distinct ways to assess both measurements for accuracy.

How is reliability measured?

These measures of consistency and stability help assess reliability, including:

Consistency and stability of the same measure when repeated multiple times and conditions

Consistency and stability of the measure across different test subjects

Consistency and stability of results from different parts of a test designed to measure the same thing

How is validity measured?

Since validity refers to how accurately a method measures what it is intended to measure, it can be difficult to assess the accuracy. Validity can be estimated by comparing research results to other relevant data or theories.

The adherence of a measure to existing knowledge of how the concept is measured

The ability to cover all aspects of the concept being measured

The relation of the result in comparison with other valid measures of the same concept

- What are the types of validity in a research design?

Research validity is broadly gathered into two groups: internal and external. Yet, this grouping doesn't clearly define the different types of validity. Research validity can be divided into seven distinct groups.

Face validity : A test that appears valid simply because of the appropriateness or relativity of the testing method, included information, or tools used.

Content validity : The determination that the measure used in research covers the full domain of the content.

Construct validity : The assessment of the suitability of the measurement tool to measure the activity being studied.

Internal validity : The assessment of how your research environment affects measurement results. This is where other factors can’t explain the extent of an observed cause-and-effect response.

External validity : The extent to which the study will be accurate beyond the sample and the level to which it can be generalized in other settings, populations, and measures.

Statistical conclusion validity: The determination of whether a relationship exists between procedures and outcomes (appropriate sampling and measuring procedures along with appropriate statistical tests).

Criterion-related validity : A measurement of the quality of your testing methods against a criterion measure (like a “gold standard” test) that is measured at the same time.

- Examples of validity

Like different types of research and the various ways to measure validity, examples of validity can vary widely. These include:

A questionnaire may be considered valid because each question addresses specific and relevant aspects of the study subject.

In a brand assessment study, researchers can use comparison testing to verify the results of an initial study. For example, the results from a focus group response about brand perception are considered more valid when the results match that of a questionnaire answered by current and potential customers.

A test to measure a class of students' understanding of the English language contains reading, writing, listening, and speaking components to cover the full scope of how language is used.

- Factors that affect research validity

Certain factors can affect research validity in both positive and negative ways. By understanding the factors that improve validity and those that threaten it, you can enhance the validity of your study. These include:

Random selection of participants vs. the selection of participants that are representative of your study criteria

Blinding with interventions the participants are unaware of (like the use of placebos)

Manipulating the experiment by inserting a variable that will change the results

Randomly assigning participants to treatment and control groups to avoid bias

Following specific procedures during the study to avoid unintended effects

Conducting a study in the field instead of a laboratory for more accurate results

Replicating the study with different factors or settings to compare results

Using statistical methods to adjust for inconclusive data

What are the common validity threats in research, and how can their effects be minimized or nullified?

Research validity can be difficult to achieve because of internal and external threats that produce inaccurate results. These factors can jeopardize validity.

History: Events that occur between an early and later measurement

Maturation: The passage of time in a study can include data on actions that would have naturally occurred outside of the settings of the study

Repeated testing: The outcome of repeated tests can change the outcome of followed tests

Selection of subjects: Unconscious bias which can result in the selection of uniform comparison groups

Statistical regression: Choosing subjects based on extremes doesn't yield an accurate outcome for the majority of individuals

Attrition: When the sample group is diminished significantly during the course of the study

Maturation: When subjects mature during the study, and natural maturation is awarded to the effects of the study

While some validity threats can be minimized or wholly nullified, removing all threats from a study is impossible. For example, random selection can remove unconscious bias and statistical regression.

Researchers can even hope to avoid attrition by using smaller study groups. Yet, smaller study groups could potentially affect the research in other ways. The best practice for researchers to prevent validity threats is through careful environmental planning and t reliable data-gathering methods.

- How to ensure validity in your research

Researchers should be mindful of the importance of validity in the early planning stages of any study to avoid inaccurate results. Researchers must take the time to consider tools and methods as well as how the testing environment matches closely with the natural environment in which results will be used.

The following steps can be used to ensure validity in research:

Choose appropriate methods of measurement

Use appropriate sampling to choose test subjects

Create an accurate testing environment

How do you maintain validity in research?

Accurate research is usually conducted over a period of time with different test subjects. To maintain validity across an entire study, you must take specific steps to ensure that gathered data has the same levels of accuracy.

Consistency is crucial for maintaining validity in research. When researchers apply methods consistently and standardize the circumstances under which data is collected, validity can be maintained across the entire study.

Is there a need for validation of the research instrument before its implementation?

An essential part of validity is choosing the right research instrument or method for accurate results. Consider the thermometer that is reliable but still produces inaccurate results. You're unlikely to achieve research validity without activities like calibration, content, and construct validity.

- Understanding research validity for more accurate results

Without validity, research can't provide the accuracy necessary to deliver a useful study. By getting a clear understanding of validity in research, you can take steps to improve your research skills and achieve more accurate results.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples

Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples

Published on 3 May 2022 by Fiona Middleton . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Reliability and validity are concepts used to evaluate the quality of research. They indicate how well a method , technique, or test measures something. Reliability is about the consistency of a measure, and validity is about the accuracy of a measure.

It’s important to consider reliability and validity when you are creating your research design , planning your methods, and writing up your results, especially in quantitative research .

| Reliability | Validity | |

|---|---|---|

| What does it tell you? | The extent to which the results can be reproduced when the research is repeated under the same conditions. | The extent to which the results really measure what they are supposed to measure. |

| How is it assessed? | By checking the consistency of results across time, across different observers, and across parts of the test itself. | By checking how well the results correspond to established theories and other measures of the same concept. |

| How do they relate? | A reliable measurement is not always valid: the results might be reproducible, but they’re not necessarily correct. | A valid measurement is generally reliable: if a test produces accurate results, they should be . |

Table of contents

Understanding reliability vs validity, how are reliability and validity assessed, how to ensure validity and reliability in your research, where to write about reliability and validity in a thesis.

Reliability and validity are closely related, but they mean different things. A measurement can be reliable without being valid. However, if a measurement is valid, it is usually also reliable.

What is reliability?

Reliability refers to how consistently a method measures something. If the same result can be consistently achieved by using the same methods under the same circumstances, the measurement is considered reliable.

What is validity?

Validity refers to how accurately a method measures what it is intended to measure. If research has high validity, that means it produces results that correspond to real properties, characteristics, and variations in the physical or social world.

High reliability is one indicator that a measurement is valid. If a method is not reliable, it probably isn’t valid.

However, reliability on its own is not enough to ensure validity. Even if a test is reliable, it may not accurately reflect the real situation.

Validity is harder to assess than reliability, but it is even more important. To obtain useful results, the methods you use to collect your data must be valid: the research must be measuring what it claims to measure. This ensures that your discussion of the data and the conclusions you draw are also valid.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Reliability can be estimated by comparing different versions of the same measurement. Validity is harder to assess, but it can be estimated by comparing the results to other relevant data or theory. Methods of estimating reliability and validity are usually split up into different types.

Types of reliability

Different types of reliability can be estimated through various statistical methods.

| Type of reliability | What does it assess? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| The consistency of a measure : do you get the same results when you repeat the measurement? | A group of participants complete a designed to measure personality traits. If they repeat the questionnaire days, weeks, or months apart and give the same answers, this indicates high test-retest reliability. | |

| The consistency of a measure : do you get the same results when different people conduct the same measurement? | Based on an assessment criteria checklist, five examiners submit substantially different results for the same student project. This indicates that the assessment checklist has low inter-rater reliability (for example, because the criteria are too subjective). | |

| The consistency of : do you get the same results from different parts of a test that are designed to measure the same thing? | You design a questionnaire to measure self-esteem. If you randomly split the results into two halves, there should be a between the two sets of results. If the two results are very different, this indicates low internal consistency. |

Types of validity

The validity of a measurement can be estimated based on three main types of evidence. Each type can be evaluated through expert judgement or statistical methods.

| Type of validity | What does it assess? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| The adherence of a measure to of the concept being measured. | A self-esteem questionnaire could be assessed by measuring other traits known or assumed to be related to the concept of self-esteem (such as social skills and optimism). Strong correlation between the scores for self-esteem and associated traits would indicate high construct validity. | |

| The extent to which the measurement of the concept being measured. | A test that aims to measure a class of students’ level of Spanish contains reading, writing, and speaking components, but no listening component. Experts agree that listening comprehension is an essential aspect of language ability, so the test lacks content validity for measuring the overall level of ability in Spanish. | |

| The extent to which the result of a measure corresponds to of the same concept. | A is conducted to measure the political opinions of voters in a region. If the results accurately predict the later outcome of an election in that region, this indicates that the survey has high criterion validity. |

To assess the validity of a cause-and-effect relationship, you also need to consider internal validity (the design of the experiment ) and external validity (the generalisability of the results).

The reliability and validity of your results depends on creating a strong research design , choosing appropriate methods and samples, and conducting the research carefully and consistently.

Ensuring validity

If you use scores or ratings to measure variations in something (such as psychological traits, levels of ability, or physical properties), it’s important that your results reflect the real variations as accurately as possible. Validity should be considered in the very earliest stages of your research, when you decide how you will collect your data .

- Choose appropriate methods of measurement

Ensure that your method and measurement technique are of high quality and targeted to measure exactly what you want to know. They should be thoroughly researched and based on existing knowledge.

For example, to collect data on a personality trait, you could use a standardised questionnaire that is considered reliable and valid. If you develop your own questionnaire, it should be based on established theory or the findings of previous studies, and the questions should be carefully and precisely worded.

- Use appropriate sampling methods to select your subjects

To produce valid generalisable results, clearly define the population you are researching (e.g., people from a specific age range, geographical location, or profession). Ensure that you have enough participants and that they are representative of the population.

Ensuring reliability

Reliability should be considered throughout the data collection process. When you use a tool or technique to collect data, it’s important that the results are precise, stable, and reproducible.

- Apply your methods consistently

Plan your method carefully to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each measurement. This is especially important if multiple researchers are involved.

For example, if you are conducting interviews or observations, clearly define how specific behaviours or responses will be counted, and make sure questions are phrased the same way each time.

- Standardise the conditions of your research

When you collect your data, keep the circumstances as consistent as possible to reduce the influence of external factors that might create variation in the results.

For example, in an experimental setup, make sure all participants are given the same information and tested under the same conditions.

It’s appropriate to discuss reliability and validity in various sections of your thesis or dissertation or research paper. Showing that you have taken them into account in planning your research and interpreting the results makes your work more credible and trustworthy.

| Section | Discuss |

|---|---|

| What have other researchers done to devise and improve methods that are reliable and valid? | |

| How did you plan your research to ensure reliability and validity of the measures used? This includes the chosen sample set and size, sample preparation, external conditions, and measuring techniques. | |

| If you calculate reliability and validity, state these values alongside your main results. | |

| This is the moment to talk about how reliable and valid your results actually were. Were they consistent, and did they reflect true values? If not, why not? | |

| If reliability and validity were a big problem for your findings, it might be helpful to mention this here. |

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Middleton, F. (2022, October 10). Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/reliability-or-validity/

Is this article helpful?

Fiona Middleton

Other students also liked, the 4 types of validity | types, definitions & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, sampling methods | types, techniques, & examples.

Validity & Reliability In Research

A Plain-Language Explanation (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | September 2023

Validity and reliability are two related but distinctly different concepts within research. Understanding what they are and how to achieve them is critically important to any research project. In this post, we’ll unpack these two concepts as simply as possible.

This post is based on our popular online course, Research Methodology Bootcamp . In the course, we unpack the basics of methodology using straightfoward language and loads of examples. If you’re new to academic research, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Validity & Reliability

- The big picture

- Validity 101

- Reliability 101

- Key takeaways

First, The Basics…

First, let’s start with a big-picture view and then we can zoom in to the finer details.

Validity and reliability are two incredibly important concepts in research, especially within the social sciences. Both validity and reliability have to do with the measurement of variables and/or constructs – for example, job satisfaction, intelligence, productivity, etc. When undertaking research, you’ll often want to measure these types of constructs and variables and, at the simplest level, validity and reliability are about ensuring the quality and accuracy of those measurements .

As you can probably imagine, if your measurements aren’t accurate or there are quality issues at play when you’re collecting your data, your entire study will be at risk. Therefore, validity and reliability are very important concepts to understand (and to get right). So, let’s unpack each of them.

What Is Validity?

In simple terms, validity (also called “construct validity”) is all about whether a research instrument accurately measures what it’s supposed to measure .

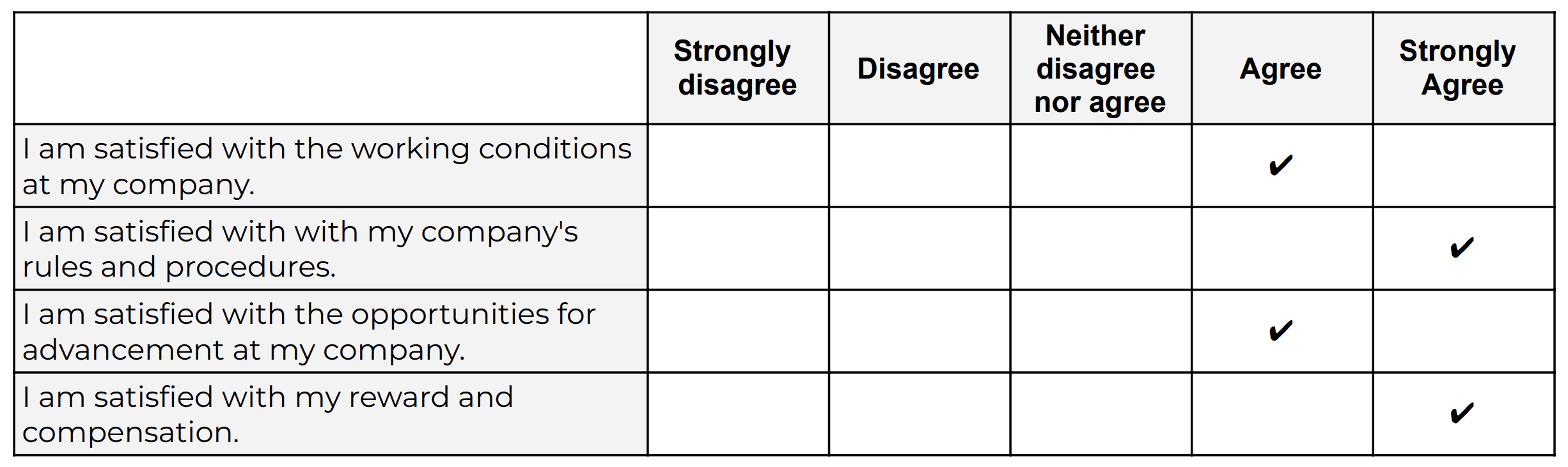

For example, let’s say you have a set of Likert scales that are supposed to quantify someone’s level of overall job satisfaction. If this set of scales focused purely on only one dimension of job satisfaction, say pay satisfaction, this would not be a valid measurement, as it only captures one aspect of the multidimensional construct. In other words, pay satisfaction alone is only one contributing factor toward overall job satisfaction, and therefore it’s not a valid way to measure someone’s job satisfaction.

Oftentimes in quantitative studies, the way in which the researcher or survey designer interprets a question or statement can differ from how the study participants interpret it . Given that respondents don’t have the opportunity to ask clarifying questions when taking a survey, it’s easy for these sorts of misunderstandings to crop up. Naturally, if the respondents are interpreting the question in the wrong way, the data they provide will be pretty useless . Therefore, ensuring that a study’s measurement instruments are valid – in other words, that they are measuring what they intend to measure – is incredibly important.

There are various types of validity and we’re not going to go down that rabbit hole in this post, but it’s worth quickly highlighting the importance of making sure that your research instrument is tightly aligned with the theoretical construct you’re trying to measure . In other words, you need to pay careful attention to how the key theories within your study define the thing you’re trying to measure – and then make sure that your survey presents it in the same way.

For example, sticking with the “job satisfaction” construct we looked at earlier, you’d need to clearly define what you mean by job satisfaction within your study (and this definition would of course need to be underpinned by the relevant theory). You’d then need to make sure that your chosen definition is reflected in the types of questions or scales you’re using in your survey . Simply put, you need to make sure that your survey respondents are perceiving your key constructs in the same way you are. Or, even if they’re not, that your measurement instrument is capturing the necessary information that reflects your definition of the construct at hand.

If all of this talk about constructs sounds a bit fluffy, be sure to check out Research Methodology Bootcamp , which will provide you with a rock-solid foundational understanding of all things methodology-related. Remember, you can take advantage of our 60% discount offer using this link.

Need a helping hand?

What Is Reliability?

As with validity, reliability is an attribute of a measurement instrument – for example, a survey, a weight scale or even a blood pressure monitor. But while validity is concerned with whether the instrument is measuring the “thing” it’s supposed to be measuring, reliability is concerned with consistency and stability . In other words, reliability reflects the degree to which a measurement instrument produces consistent results when applied repeatedly to the same phenomenon , under the same conditions .

As you can probably imagine, a measurement instrument that achieves a high level of consistency is naturally more dependable (or reliable) than one that doesn’t – in other words, it can be trusted to provide consistent measurements . And that, of course, is what you want when undertaking empirical research. If you think about it within a more domestic context, just imagine if you found that your bathroom scale gave you a different number every time you hopped on and off of it – you wouldn’t feel too confident in its ability to measure the variable that is your body weight 🙂

It’s worth mentioning that reliability also extends to the person using the measurement instrument . For example, if two researchers use the same instrument (let’s say a measuring tape) and they get different measurements, there’s likely an issue in terms of how one (or both) of them are using the measuring tape. So, when you think about reliability, consider both the instrument and the researcher as part of the equation.

As with validity, there are various types of reliability and various tests that can be used to assess the reliability of an instrument. A popular one that you’ll likely come across for survey instruments is Cronbach’s alpha , which is a statistical measure that quantifies the degree to which items within an instrument (for example, a set of Likert scales) measure the same underlying construct . In other words, Cronbach’s alpha indicates how closely related the items are and whether they consistently capture the same concept .

Recap: Key Takeaways

Alright, let’s quickly recap to cement your understanding of validity and reliability:

- Validity is concerned with whether an instrument (e.g., a set of Likert scales) is measuring what it’s supposed to measure

- Reliability is concerned with whether that measurement is consistent and stable when measuring the same phenomenon under the same conditions.

In short, validity and reliability are both essential to ensuring that your data collection efforts deliver high-quality, accurate data that help you answer your research questions . So, be sure to always pay careful attention to the validity and reliability of your measurement instruments when collecting and analysing data. As the adage goes, “rubbish in, rubbish out” – make sure that your data inputs are rock-solid.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Methodology Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS.

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS AND I HAVE GREATLY BENEFITED FROM THE CONTENT.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Understanding Reliability and Validity

These related research issues ask us to consider whether we are studying what we think we are studying and whether the measures we use are consistent.

Reliability

Reliability is the extent to which an experiment, test, or any measuring procedure yields the same result on repeated trials. Without the agreement of independent observers able to replicate research procedures, or the ability to use research tools and procedures that yield consistent measurements, researchers would be unable to satisfactorily draw conclusions, formulate theories, or make claims about the generalizability of their research. In addition to its important role in research, reliability is critical for many parts of our lives, including manufacturing, medicine, and sports.

Reliability is such an important concept that it has been defined in terms of its application to a wide range of activities. For researchers, four key types of reliability are:

Equivalency Reliability

Equivalency reliability is the extent to which two items measure identical concepts at an identical level of difficulty. Equivalency reliability is determined by relating two sets of test scores to one another to highlight the degree of relationship or association. In quantitative studies and particularly in experimental studies, a correlation coefficient, statistically referred to as r , is used to show the strength of the correlation between a dependent variable (the subject under study), and one or more independent variables , which are manipulated to determine effects on the dependent variable. An important consideration is that equivalency reliability is concerned with correlational, not causal, relationships.

For example, a researcher studying university English students happened to notice that when some students were studying for finals, their holiday shopping began. Intrigued by this, the researcher attempted to observe how often, or to what degree, this these two behaviors co-occurred throughout the academic year. The researcher used the results of the observations to assess the correlation between studying throughout the academic year and shopping for gifts. The researcher concluded there was poor equivalency reliability between the two actions. In other words, studying was not a reliable predictor of shopping for gifts.

Stability Reliability

Stability reliability (sometimes called test, re-test reliability) is the agreement of measuring instruments over time. To determine stability, a measure or test is repeated on the same subjects at a future date. Results are compared and correlated with the initial test to give a measure of stability.

An example of stability reliability would be the method of maintaining weights used by the U.S. Bureau of Standards. Platinum objects of fixed weight (one kilogram, one pound, etc...) are kept locked away. Once a year they are taken out and weighed, allowing scales to be reset so they are "weighing" accurately. Keeping track of how much the scales are off from year to year establishes a stability reliability for these instruments. In this instance, the platinum weights themselves are assumed to have a perfectly fixed stability reliability.

Internal Consistency

Internal consistency is the extent to which tests or procedures assess the same characteristic, skill or quality. It is a measure of the precision between the observers or of the measuring instruments used in a study. This type of reliability often helps researchers interpret data and predict the value of scores and the limits of the relationship among variables.

For example, a researcher designs a questionnaire to find out about college students' dissatisfaction with a particular textbook. Analyzing the internal consistency of the survey items dealing with dissatisfaction will reveal the extent to which items on the questionnaire focus on the notion of dissatisfaction.

Interrater Reliability

Interrater reliability is the extent to which two or more individuals (coders or raters) agree. Interrater reliability addresses the consistency of the implementation of a rating system.

A test of interrater reliability would be the following scenario: Two or more researchers are observing a high school classroom. The class is discussing a movie that they have just viewed as a group. The researchers have a sliding rating scale (1 being most positive, 5 being most negative) with which they are rating the student's oral responses. Interrater reliability assesses the consistency of how the rating system is implemented. For example, if one researcher gives a "1" to a student response, while another researcher gives a "5," obviously the interrater reliability would be inconsistent. Interrater reliability is dependent upon the ability of two or more individuals to be consistent. Training, education and monitoring skills can enhance interrater reliability.

Related Information: Reliability Example

An example of the importance of reliability is the use of measuring devices in Olympic track and field events. For the vast majority of people, ordinary measuring rulers and their degree of accuracy are reliable enough. However, for an Olympic event, such as the discus throw, the slightest variation in a measuring device -- whether it is a tape, clock, or other device -- could mean the difference between the gold and silver medals. Additionally, it could mean the difference between a new world record and outright failure to qualify for an event. Olympic measuring devices, then, must be reliable from one throw or race to another and from one competition to another. They must also be reliable when used in different parts of the world, as temperature, air pressure, humidity, interpretation, or other variables might affect their readings.

Validity refers to the degree to which a study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure. While reliability is concerned with the accuracy of the actual measuring instrument or procedure, validity is concerned with the study's success at measuring what the researchers set out to measure.

Researchers should be concerned with both external and internal validity. External validity refers to the extent to which the results of a study are generalizable or transferable. (Most discussions of external validity focus solely on generalizability; see Campbell and Stanley, 1966. We include a reference here to transferability because many qualitative research studies are not designed to be generalized.)

Internal validity refers to (1) the rigor with which the study was conducted (e.g., the study's design, the care taken to conduct measurements, and decisions concerning what was and wasn't measured) and (2) the extent to which the designers of a study have taken into account alternative explanations for any causal relationships they explore (Huitt, 1998). In studies that do not explore causal relationships, only the first of these definitions should be considered when assessing internal validity.

Scholars discuss several types of internal validity. For brief discussions of several types of internal validity, click on the items below:

Face Validity

Face validity is concerned with how a measure or procedure appears. Does it seem like a reasonable way to gain the information the researchers are attempting to obtain? Does it seem well designed? Does it seem as though it will work reliably? Unlike content validity, face validity does not depend on established theories for support (Fink, 1995).

Criterion Related Validity

Criterion related validity, also referred to as instrumental validity, is used to demonstrate the accuracy of a measure or procedure by comparing it with another measure or procedure which has been demonstrated to be valid.

For example, imagine a hands-on driving test has been shown to be an accurate test of driving skills. By comparing the scores on the written driving test with the scores from the hands-on driving test, the written test can be validated by using a criterion related strategy in which the hands-on driving test is compared to the written test.

Construct Validity

Construct validity seeks agreement between a theoretical concept and a specific measuring device or procedure. For example, a researcher inventing a new IQ test might spend a great deal of time attempting to "define" intelligence in order to reach an acceptable level of construct validity.

Construct validity can be broken down into two sub-categories: Convergent validity and discriminate validity. Convergent validity is the actual general agreement among ratings, gathered independently of one another, where measures should be theoretically related. Discriminate validity is the lack of a relationship among measures which theoretically should not be related.

To understand whether a piece of research has construct validity, three steps should be followed. First, the theoretical relationships must be specified. Second, the empirical relationships between the measures of the concepts must be examined. Third, the empirical evidence must be interpreted in terms of how it clarifies the construct validity of the particular measure being tested (Carmines & Zeller, p. 23).

Content Validity

Content Validity is based on the extent to which a measurement reflects the specific intended domain of content (Carmines & Zeller, 1991, p.20).

Content validity is illustrated using the following examples: Researchers aim to study mathematical learning and create a survey to test for mathematical skill. If these researchers only tested for multiplication and then drew conclusions from that survey, their study would not show content validity because it excludes other mathematical functions. Although the establishment of content validity for placement-type exams seems relatively straight-forward, the process becomes more complex as it moves into the more abstract domain of socio-cultural studies. For example, a researcher needing to measure an attitude like self-esteem must decide what constitutes a relevant domain of content for that attitude. For socio-cultural studies, content validity forces the researchers to define the very domains they are attempting to study.

Related Information: Validity Example

Many recreational activities of high school students involve driving cars. A researcher, wanting to measure whether recreational activities have a negative effect on grade point average in high school students, might conduct a survey asking how many students drive to school and then attempt to find a correlation between these two factors. Because many students might use their cars for purposes other than or in addition to recreation (e.g., driving to work after school, driving to school rather than walking or taking a bus), this research study might prove invalid. Even if a strong correlation was found between driving and grade point average, driving to school in and of itself would seem to be an invalid measure of recreational activity.

The challenges of achieving reliability and validity are among the most difficult faced by researchers. In this section, we offer commentaries on these challenges.

Difficulties of Achieving Reliability

It is important to understand some of the problems concerning reliability which might arise. It would be ideal to reliably measure, every time, exactly those things which we intend to measure. However, researchers can go to great lengths and make every attempt to ensure accuracy in their studies, and still deal with the inherent difficulties of measuring particular events or behaviors. Sometimes, and particularly in studies of natural settings, the only measuring device available is the researcher's own observations of human interaction or human reaction to varying stimuli. As these methods are ultimately subjective in nature, results may be unreliable and multiple interpretations are possible. Three of these inherent difficulties are quixotic reliability, diachronic reliability and synchronic reliability.

Quixotic reliability refers to the situation where a single manner of observation consistently, yet erroneously, yields the same result. It is often a problem when research appears to be going well. This consistency might seem to suggest that the experiment was demonstrating perfect stability reliability. This, however, would not be the case.

For example, if a measuring device used in an Olympic competition always read 100 meters for every discus throw, this would be an example of an instrument consistently, yet erroneously, yielding the same result. However, quixotic reliability is often more subtle in its occurrences than this. For example, suppose a group of German researchers doing an ethnographic study of American attitudes ask questions and record responses. Parts of their study might produce responses which seem reliable, yet turn out to measure felicitous verbal embellishments required for "correct" social behavior. Asking Americans, "How are you?" for example, would in most cases, elicit the token, "Fine, thanks." However, this response would not accurately represent the mental or physical state of the respondents.

Diachronic reliability refers to the stability of observations over time. It is similar to stability reliability in that it deals with time. While this type of reliability is appropriate to assess features that remain relatively unchanged over time, such as landscape benchmarks or buildings, the same level of reliability is more difficult to achieve with socio-cultural phenomena.

For example, in a follow-up study one year later of reading comprehension in a specific group of school children, diachronic reliability would be hard to achieve. If the test were given to the same subjects a year later, many confounding variables would have impacted the researchers' ability to reproduce the same circumstances present at the first test. The final results would almost assuredly not reflect the degree of stability sought by the researchers.

Synchronic reliability refers to the similarity of observations within the same time frame; it is not about the similarity of things observed. Synchronic reliability, unlike diachronic reliability, rarely involves observations of identical things. Rather, it concerns itself with particularities of interest to the research.

For example, a researcher studies the actions of a duck's wing in flight and the actions of a hummingbird's wing in flight. Despite the fact that the researcher is studying two distinctly different kinds of wings, the action of the wings and the phenomenon produced is the same.

Comments on a Flawed, Yet Influential Study

An example of the dangers of generalizing from research that is inconsistent, invalid, unreliable, and incomplete is found in the Time magazine article, "On A Screen Near You: Cyberporn" (De Witt, 1995). This article relies on a study done at Carnegie Mellon University to determine the extent and implications of online pornography. Inherent to the study are methodological problems of unqualified hypotheses and conclusions, unsupported generalizations and a lack of peer review.

Ignoring the functional problems that manifest themselves later in the study, it seems that there are a number of ethical problems within the article. The article claims to be an exhaustive study of pornography on the Internet, (it was anything but exhaustive), it resembles a case study more than anything else. Marty Rimm, author of the undergraduate paper that Time used as a basis for the article, claims the paper was an "exhaustive study" of online pornography when, in fact, the study based most of its conclusions about pornography on the Internet on the "descriptions of slightly more than 4,000 images" (Meeks, 1995, p. 1). Some USENET groups see hundreds of postings in a day.

Considering the thousands of USENET groups, 4,000 images no longer carries the authoritative weight that its author intended. The real problem is that the study (an undergraduate paper similar to a second-semester composition assignment) was based not on pornographic images themselves, but on the descriptions of those images. This kind of reduction detracts significantly from the integrity of the final claims made by the author. In fact, this kind of research is commensurate with doing a study of the content of pornographic movies based on the titles of the movies, then making sociological generalizations based on what those titles indicate. (This is obviously a problem with a number of types of validity, because Rimm is not studying what he thinks he is studying, but instead something quite different. )

The author of the Time article, Philip Elmer De Witt writes, "The research team at CMU has undertaken the first systematic study of pornography on the Information Superhighway" (Godwin, 1995, p. 1). His statement is problematic in at least three ways. First, the research team actually consisted of a few of Rimm's undergraduate friends with no methodological training whatsoever. Additionally, no mention of the degree of interrater reliability is made. Second, this systematic study is actually merely a "non-randomly selected subset of commercial bulletin-board systems that focus on selling porn" (Godwin, p. 6). As pornography vending is actually just a small part of the whole concerning the use of pornography on the Internet, the entire premise of this study's content validity is firmly called into question. Finally, the use of the term "Information Superhighway" is a false assessment of what in actuality is only a few USENET groups and BBSs (Bulletin Board System), which make up only a small fraction of the entire "Information Superhighway" traffic. Essentially, what is here is yet another violation of content validity.

De Witt is quoted as saying: "In an 18-month study, the team surveyed 917,410 sexually-explicit pictures, descriptions, short-stories and film clips. On those USENET newsgroups where digitized images are stored, 83.5 percent of the pictures were pornographic" (De Witt 40).

Statistically, some interesting contradictions arise. The figure 917,410 was taken from adult-oriented BBSs--none came from actual USENET groups or the Internet itself. This is a glaring discrepancy. Out of the 917,410 files, 212,114 are only descriptions (Hoffman & Novak, 1995, p.2). The question is, how many actual images did the "researchers" see?

"Between April and July 1994, the research team downloaded all available images (3,254)...the team encountered technical difficulties with 13 percent of these images...This left a total of 2,830 images for analysis" (p. 2). This means that out of 917,410 files discussed in this study, 914,580 of them were not even pictures! As for the 83.5 percent figure, this is actually based on "17 alt.binaries groups that Rimm considered pornographic" (p. 2).

In real terms, 17 USENET groups is a fraction of a percent of all USENET groups available. Worse yet, Time claimed that "...only about 3 percent of all messages on the USENET [represent pornographic material], while the USENET itself represents 11.5 percent of the traffic on the Internet" (De Witt, p. 40).

Time neglected to carry the interpretation of this data out to its logical conclusion, which is that less than half of 1 percent (3 percent of 11 percent) of the images on the Internet are associated with newsgroups that contain pornographic imagery. Furthermore, of this half percent, an unknown but even smaller percentage of the messages in newsgroups that are 'associated with pornographic imagery', actually contained pornographic material (Hoffman & Novak, p. 3).

Another blunder can be seen in the avoidance of peer-review, which suggests that there was some political interests being served in having the study become a Time cover story. Marty Rimm contracted the Georgetown Law Review and Time in an agreement to publish his study as long as they kept it under lock and key. During the months before publication, many interested scholars and professionals tried in vain to obtain a copy of the study in order to check it for flaws. De Witt justified not letting such peer-review take place, and also justified the reliability and validity of the study, on the grounds that because the Georgetown Law Review had accepted it, it was therefore reliable and valid, and needed no peer-review. What he didn't know, was that law reviews are not edited by professionals, but by "third year law students" (Godwin, p. 4).

There are many consequences of the failure to subject such a study to the scrutiny of peer review. If it was Rimm's desire to publish an article about on-line pornography in a manner that legitimized his article, yet escaped the kind of critical review the piece would have to undergo if published in a scholarly journal of computer-science, engineering, marketing, psychology, or communications. What better venue than a law journal? A law journal article would have the added advantage of being taken seriously by law professors, lawyers, and legally-trained policymakers. By virtue of where it appeared, it would automatically be catapulted into the center of the policy debate surrounding online censorship and freedom of speech (Godwin).

Herein lies the dangerous implication of such a study: Because the questions surrounding pornography are of such immediate political concern, the study was placed in the forefront of the U.S. domestic policy debate over censorship on the Internet, (an integral aspect of current anti-First Amendment legislation) with little regard for its validity or reliability.

On June 26, the day the article came out, Senator Grassley, (co-sponsor of the anti-porn bill, along with Senator Dole) began drafting a speech that was to be delivered that very day in the Senate, using the study as evidence. The same day, at the same time, Mike Godwin posted on WELL (Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link, a forum for professionals on the Internet) what turned out to be the overstatement of the year: "Philip's story is an utter disaster, and it will damage the debate about this issue because we will have to spend lots of time correcting misunderstandings that are directly attributable to the story" (Meeks, p. 7).

As Godwin was writing this, Senator Grassley was speaking to the Senate: "Mr. President, I want to repeat that: 83.5 percent of the 900,000 images reviewed--these are all on the Internet--are pornographic, according to the Carnegie-Mellon study" ( p. 7). Several days later, Senator Dole was waving the magazine in front of the Senate like a battle flag.

Donna Hoffman, professor at Vanderbilt University, summed up the dangerous political implications by saying, "The critically important national debate over First Amendment rights and restrictions of information on the Internet and other emerging media requires facts and informed opinion, not hysteria" (p.1).

In addition to the hysteria, Hoffman sees a plethora of other problems with the study. "Because the content analysis and classification scheme are 'black boxes,'" Hoffman said, "because no reliability and validity results are presented, because no statistical testing of the differences both within and among categories for different types of listings has been performed, and because not a single hypothesis has been tested, formally or otherwise, no conclusions should be drawn until the issues raised in this critique are resolved" (p. 4).

However, the damage has already been done. This questionable research by an undergraduate engineering major has been generalized to such an extent that even the U.S. Senate, and in particular Senators Grassley and Dole, have been duped, albeit through the strength of their own desires to see only what they wanted to see.

Annotated Bibliography

American Psychological Association. (1985). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, DC: Author.

This work on focuses on reliability, validity and the standards that testers need to achieve in order to ensure accuracy.

Babbie, E.R. & Huitt, R.E. (1979). The practice of social research 2nd ed . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

An overview of social research and its applications.

Beauchamp, T. L., Faden, R.R., Wallace, Jr., R.J. & Walters, L . ( 1982). Ethical issues in social science research. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

A systematic overview of ethical issues in Social Science Research written by researchers with firsthand familiarity with the situations and problems researchers face in their work. This book raises several questions of how reliability and validity can be affected by ethics.

Borman, K.M. et al. (1986). Ethnographic and qualitative research design and why it doesn't work. American behavioral scientist 30 , 42-57.

The authors pose questions concerning threats to qualitative research and suggest solutions.

Bowen, K. A. (1996, Oct. 12). The sin of omission -punishable by death to internal validity: An argument for integration of quantitative research methods to strengthen internal validity. Available: http://trochim.human.cornell.edu/gallery/bowen/hss691.htm

An entire Web site that examines the merits of integrating qualitative and quantitative research methodologies through triangulation. The author argues that improving the internal validity of social science will be the result of such a union.

Brinberg, D. & McGrath, J.E. (1985). Validity and the research process . Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

The authors investigate validity as value and propose the Validity Network Schema, a process by which researchers can infuse validity into their research.

Bussières, J-F. (1996, Oct.12). Reliability and validity of information provided by museum Web sites. Available: http://www.oise.on.ca/~jfbussieres/issue.html

This Web page examines the validity of museum Web sites which calls into question the validity of Web-based resources in general. Addresses the issue that all Websites should be examined with skepticism about the validity of the information contained within them.

Campbell, D. T. & Stanley, J.C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

An overview of experimental research that includes pre-experimental designs, controls for internal validity, and tables listing sources of invalidity in quasi-experimental designs. Reference list and examples.

Carmines, E. G. & Zeller, R.A. (1991). Reliability and validity assessment . Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

An introduction to research methodology that includes classical test theory, validity, and methods of assessing reliability.

Carroll, K. M. (1995). Methodological issues and problems in the assessment of substance use. Psychological Assessment, Sep. 7 n3 , 349-58.

Discusses methodological issues in research involving the assessment of substance abuse. Introduces strategies for avoiding problems with the reliability and validity of methods.

Connelly, F. M. & Clandinin, D.J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher 19:5 , 2-12.

A survey of narrative inquiry that outlines criteria, methods, and writing forms. It includes a discussion of risks and dangers in narrative studies, as well as a research agenda for curricula and classroom studies.

De Witt, P.E. (1995, July 3). On a screen near you: Cyberporn. Time, 38-45.

This is an exhaustive Carnegie Mellon study of online pornography by Marty Rimm, electrical engineering student.

Fink, A., ed. (1995). The survey Handbook, v.1 .Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

A guide to survey; this is the first in a series referred to as the "survey kit". It includes bibliograpgical references. Addresses survey design, analysis, reporting surveys and how to measure the validity and reliability of surveys.

Fink, A., ed. (1995). How to measure survey reliability and validity v. 7 . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

This volume seeks to select and apply reliability criteria and select and apply validity criteria. The fundamental principles of scaling and scoring are considered.

Godwin, M. (1995, July). JournoPorn, dissection of the Time article. Available: http://www.hotwired.com

A detailed critique of Time magazine's Cyberporn , outlining flaws of methodology as well as exploring the underlying assumptions of the article.

Hambleton, R.K. & Zaal, J.N., eds. (1991). Advances in educational and psychological testing . Boston: Kluwer Academic.

Information on the concepts of reliability and validity in psychology and education.

Harnish, D.L. (1992). Human judgment and the logic of evidence: A critical examination of research methods in special education transition literature . In D.L. Harnish et al. eds., Selected readings in transition.

This article investigates threats to validity in special education research.

Haynes, N. M. (1995). How skewed is 'the bell curve'? Book Product Reviews . 1-24.

This paper claims that R.J. Herrnstein and C. Murray's The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life does not have scientific merit and claims that the bell curve is an unreliable measure of intelligence.

Healey, J. F. (1993). Statistics: A tool for social research, 3rd ed . Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing.

Inferential statistics, measures of association, and multivariate techniques in statistical analysis for social scientists are addressed.

Helberg, C. (1996, Oct.12). Pitfalls of data analysis (or how to avoid lies and damned lies). Available: http//maddog/fammed.wisc.edu/pitfalls/

A discussion of things researchers often overlook in their data analysis and how statistics are often used to skew reliability and validity for the researchers purposes.

Hoffman, D. L. and Novak, T.P. (1995, July). A detailed critique of the Time article: Cyberporn. Available: http://www.hotwired.com

A methodological critique of the Time article that uncovers some of the fundamental flaws in the statistics and the conclusions made by De Witt.

Huitt, William G. (1998). Internal and External Validity . http://www.valdosta.peachnet.edu/~whuitt/psy702/intro/valdgn.html

A Web document addressing key issues of external and internal validity.

Jones, J. E. & Bearley, W.L. (1996, Oct 12). Reliability and validity of training instruments. Organizational Universe Systems. Available: http://ous.usa.net/relval.htm

The authors discuss the reliability and validity of training design in a business setting. Basic terms are defined and examples provided.

Cultural Anthropology Methods Journal. (1996, Oct. 12). Available: http://www.lawrence.edu/~bradleyc/cam.html

An online journal containing articles on the practical application of research methods when conducting qualitative and quantitative research. Reliability and validity are addressed throughout.

Kirk, J. & Miller, M. M. (1986). Reliability and validity in qualitative research. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

This text describes objectivity in qualitative research by focusing on the issues of validity and reliability in terms of their limitations and applicability in the social and natural sciences.

Krakower, J. & Niwa, S. (1985). An assessment of validity and reliability of the institutinal perfarmance survey . Boulder, CO: National center for higher education management systems.

Educational surveys and higher education research and the efeectiveness of organization.

Lauer, J. M. & Asher, J.W. (1988). Composition Research. New York: Oxford University Press.

A discussion of empirical designs in the context of composition research as a whole.

Laurent, J. et al. (1992, Mar.) Review of validity research on the stanford-binet intelligence scale: 4th Ed. Psychological Assessment . 102-112.

This paper looks at the results of construct and criterion- related validity studies to determine if the SB:FE is a valid measure of intelligence.

LeCompte, M. D., Millroy, W.L., & Preissle, J. eds. (1992). The handbook of qualitative research in education. San Diego: Academic Press.

A compilation of the range of methodological and theoretical qualitative inquiry in the human sciences and education research. Numerous contributing authors apply their expertise to discussing a wide variety of issues pertaining to educational and humanities research as well as suggestions about how to deal with problems when conducting research.

McDowell, I. & Newell, C. (1987). Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires . New York: Oxford University Press.

This gives a variety of examples of health measurement techniques and scales and discusses the validity and reliability of important health measures.

Meeks, B. (1995, July). Muckraker: How Time failed. Available: http://www.hotwired.com

A step-by-step outline of the events which took place during the researching, writing, and negotiating of the Time article of 3 July, 1995 titled: On A Screen Near You: Cyberporn .

Merriam, S. B. (1995). What can you tell from an N of 1?: Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Journal of Lifelong Learning v4 , 51-60.

Addresses issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research for education. Discusses philosophical assumptions underlying the concepts of internal validity, reliability, and external validity or generalizability. Presents strategies for ensuring rigor and trustworthiness when conducting qualitative research.

Morris, L.L, Fitzgibbon, C.T., & Lindheim, E. (1987). How to measure performance and use tests. In J.L. Herman (Ed.), Program evaluation kit (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Discussion of reliability and validity as it pertyains to measuring students' performance.

Murray, S., et al. (1979, April). Technical issues as threats to internal validity of experimental and quasi-experimental designs. San Francisco: University of California. 8-12.

(From Yang et al. bibliography--unavailable as of this writing.)

Russ-Eft, D. F. (1980). Validity and reliability in survey research. American Institutes for Research in the Behavioral Sciences August , 227 151.

An investigation of validity and reliability in survey research with and overview of the concepts of reliability and validity. Specific procedures for measuring sources of error are suggested as well as general suggestions for improving the reliability and validity of survey data. A extensive annotated bibliography is provided.

Ryser, G. R. (1994). Developing reliable and valid authentic assessments for the classroom: Is it possible? Journal of Secondary Gifted Education Fall, v6 n1 , 62-66.

Defines the meanings of reliability and validity as they apply to standardized measures of classroom assessment. This article defines reliability as scorability and stability and validity is seen as students' ability to use knowledge authentically in the field.

Schmidt, W., et al. (1982). Validity as a variable: Can the same certification test be valid for all students? Institute for Research on Teaching July, ED 227 151.

A technical report that presents specific criteria for judging content, instructional and curricular validity as related to certification tests in education.

Scholfield, P. (1995). Quantifying language. A researcher's and teacher's guide to gathering language data and reducing it to figures . Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

A guide to categorizing, measuring, testing, and assessing aspects of language. A source for language-related practitioners and researchers in conjunction with other resources on research methods and statistics. Questions of reliability, and validity are also explored.

Scriven, M. (1993). Hard-Won Lessons in Program Evaluation . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

A common sense approach for evaluating the validity of various educational programs and how to address specific issues facing evaluators.

Shou, P. (1993, Jan.). The singer loomis inventory of personality: A review and critique. [Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Southwest Educational Research Association.]

Evidence for reliability and validity are reviewed. A summary evaluation suggests that SLIP (developed by two Jungian analysts to allow examination of personality from the perspective of Jung's typology) appears to be a useful tool for educators and counselors.

Sutton, L.R. (1992). Community college teacher evaluation instrument: A reliability and validity study . Diss. Colorado State University.

Studies of reliability and validity in occupational and educational research.

Thompson, B. & Daniel, L.G. (1996, Oct.). Seminal readings on reliability and validity: A "hit parade" bibliography. Educational and psychological measurement v. 56 , 741-745.

Editorial board members of Educational and Psychological Measurement generated bibliography of definitive publications of measurement research. Many articles are directly related to reliability and validity.

Thompson, E. Y., et al. (1995). Overview of qualitative research . Diss. Colorado State University.

A discussion of strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research and its evolution and adaptation. Appendices and annotated bibliography.

Traver, C. et al. (1995). Case Study . Diss. Colorado State University.

This presentation gives an overview of case study research, providing definitions and a brief history and explanation of how to design research.

Trochim, William M. K. (1996) External validity. (. Available: http://trochim.human.cornell.edu/kb/EXTERVAL.htm

A comprehensive treatment of external validity found in William Trochim's online text about research methods and issues.

Trochim, William M. K. (1996) Introduction to validity. (. Available: hhttp://trochim.human.cornell.edu/kb/INTROVAL.htm

An introduction to validity found in William Trochim's online text about research methods and issues.

Trochim, William M. K. (1996) Reliability. (. Available: http://trochim.human.cornell.edu/kb/reltypes.htm

A comprehensive treatment of reliability found in William Trochim's online text about research methods and issues.

Validity. (1996, Oct. 12). Available: http://vislab-www.nps.navy.mil/~haga/validity.html

A source for definitions of various forms and types of reliability and validity.

Vinsonhaler, J. F., et al. (1983, July). Improving diagnostic reliability in reading through training. Institute for Research on Teaching ED 237 934.

This technical report investigates the practical application of a program intended to improve the diagnoses of reading deficient students. Here, reliability is assumed and a pragmatic answer to a specific educational problem is suggested as a result.

Wentland, E. J. & Smith, K.W. (1993). Survey responses: An evaluation of their validity . San Diego: Academic Press.

This book looks at the factors affecting response validity (or the accuracy of self-reports in surveys) and provides several examples with varying accuracy levels.

Wiget, A. (1996). Father juan greyrobe: Reconstructing tradition histories, and the reliability and validity of uncorroborated oral tradition. Ethnohistory 43:3 , 459-482.

This paper presents a convincing argument for the validity of oral histories in ethnographic research where at least some of the evidence can be corroborated through written records.

Yang, G. H., et al. (1995). Experimental and quasi-experimental educational research . Diss. Colorado State University.

This discussion defines experimentation and considers the rhetorical issues and advantages and disadvantages of experimental research. Annotated bibliography.

Yarroch, W. L. (1991, Sept.). The Implications of content versus validity on science tests. Journal of Research in Science Teaching , 619-629.

The use of content validity as the primary assurance of the measurement accuracy for science assessment examinations is questioned. An alternative accuracy measure, item validity, is proposed to look at qualitative comparisons between different factors.

Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research: Design and methods . London: Sage Publications.

This book discusses the design process of case study research, including collection of evidence, composing the case study report, and designing single and multiple case studies.

Related Links

Internal Validity Tutorial. An interactive tutorial on internal validity.

http://server.bmod.athabascau.ca/html/Validity/index.shtml

Howell, Jonathan, Paul Miller, Hyun Hee Park, Deborah Sattler, Todd Schack, Eric Spery, Shelley Widhalm, & Mike Palmquist. (2005). Reliability and Validity. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=66

- How it works

Reliability and Validity – Definitions, Types & Examples

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 16th, 2021 , Revised On October 26, 2023

A researcher must test the collected data before making any conclusion. Every research design needs to be concerned with reliability and validity to measure the quality of the research.

What is Reliability?

Reliability refers to the consistency of the measurement. Reliability shows how trustworthy is the score of the test. If the collected data shows the same results after being tested using various methods and sample groups, the information is reliable. If your method has reliability, the results will be valid.

Example: If you weigh yourself on a weighing scale throughout the day, you’ll get the same results. These are considered reliable results obtained through repeated measures.

Example: If a teacher conducts the same math test of students and repeats it next week with the same questions. If she gets the same score, then the reliability of the test is high.

What is the Validity?

Validity refers to the accuracy of the measurement. Validity shows how a specific test is suitable for a particular situation. If the results are accurate according to the researcher’s situation, explanation, and prediction, then the research is valid.

If the method of measuring is accurate, then it’ll produce accurate results. If a method is reliable, then it’s valid. In contrast, if a method is not reliable, it’s not valid.

Example: Your weighing scale shows different results each time you weigh yourself within a day even after handling it carefully, and weighing before and after meals. Your weighing machine might be malfunctioning. It means your method had low reliability. Hence you are getting inaccurate or inconsistent results that are not valid.