An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

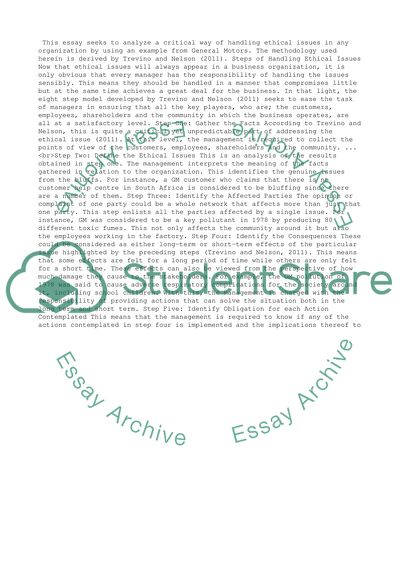

Managing organizational ethics: How ethics becomes pervasive within organizations

Cecilia martínez.

a Centre for Applied Ethics, University of Deusto, Avda. Universidades 24, 48007 Bilbao, Spain

Ann Gregg Skeet

b Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA 95053, U.S.A.

Pedro M. Sasia

This study analyzes real experiences of culture management to better understand how ethics permeates organizations . In addition to reviewing the literature, we used an action-research methodology and conducted semistructured interviews in Spain and in the U.S. to approach the complexity and challenges of fostering a culture in which ethical considerations are a regular part of business discussions and decision making. The consistency of findings suggests patterns of organizational conditions, cultural elements, and opportunities that influence the management of organizational cultures centered on core ethical values. The ethical competencies of leaders and of the workforce also emerged as key factors. We identify three conditions—a sense of responsibility to society, conditions for ethical deliberation, and respect for moral autonomy—coupled with a diverse set of cultural elements that cause ethics to take root in culture when the opportunity arises. Leaders can use this knowledge of the mechanisms by which organizational factors influence ethical pervasiveness to better manage organizational ethics.

1. Business ethics and culture management

In the last 40 years, globalization, accelerated by technological development, has transformed the context in which companies work and compete ( Dolan & Raich, 2009 ). Technology amplifies the influence of a broad group of social and political actors that have no financial stakes in companies (Kennedy, 2013). Managers have to deal with this complex and dynamic framework of social, organizational, and individual drivers of socially responsible performance. Instances of these drivers include policies, laws, and regulations (social factors); organizational ethics and tone at the top (organizational factors); and individual preferences of customers, employees, and investors. Moreover, these drivers are evolving dynamically at all three levels in response to the consequences of globalization ( Aguinis & Glavas, 2012 ). Environmental degradation, growing inequality, the 2007-2009 financial crisis, and the global COVID-19 pandemic have revived the debate on ethics in the business realm.

As a result, researchers and managers have shown renewed interest in managing organizational ethics. Companies began incorporating new values and goals beyond economic profit in their organizational cultures as a strategy to deal with the dynamic and uncertain context in which they are operating ( Garriga & Melé, 2004 ). Thus companies’ social roles and ways of doing business have evolved ( Freeman, 2017 ). In August 2019, the Business Roundtable redefined the purpose of a corporation as promoting an economy for the benefit of all stakeholders; not just shareholders but also customers, employees, suppliers, and communities ( Business Roundtable, 2019 ). They did not, however, explain how companies would achieve this new purpose. Many companies are adopting culture management, including ethics, as a strategy for meeting social demands ( Treviño et al., 2014 ). But neither the traditional triple bottom line nor the culture underpinning decisions have fully encompassed ethics ( Burford et al., 2016 ). One of the main causes of the 2007–09 financial crisis was the lack of ethics in management. Ethics has received more attention since then owing to high-profile ethical dilemmas in the technology sector, long considered an economic bellwether. Governance is also now focused on ethical culture. In 2017, the NACD Blue Ribbon Commission recommended that boards should monitor their organizations’ culture and integrate it into ongoing discussions with management about strategy, risk, and performance ( NACD, 2017 ). Although companies linked to the financial crisis and companies in the technology industry had strong reputations for corporate social responsibility and appeared to embrace ethics, the behavior of some managers in these companies was clearly unethical ( Sims & Brinkmann, 2009 ).

The predominant approach to culture management has focused on the alignment of values between the individual employee and the organization ( DiStaso, 2017 ). As a consequence, research has focused primarily on individual factors—age, behavior, personal values, or organizational commitment—more often than on organizational factors, such as culture, policies, rewards, or training ( Lehnert et al., 2015 ).

But everyday business practices have challenged the idea of a direct link between values and behavior that underlies this familiar paradigm. When inconsistencies or conflicts are perceived to threaten cognitive frameworks, individuals ( Lord & Brown, 2001 ; Watson et al., 2004 ) and groups ( List & Pettit, 2011 ) adjust their values to preserve integrity, affirm a positive self-image, or support contextual pressures that orient their behaviors. Therefore, behaviors may be most effectively influenced if management shifts its focus from defining values to creating a learning process that builds and activates a shared ethical culture ( Appelbaum et al., 2007 ; Watson et al., 2004 ). Caterina Bulgarella used the appealing metaphor of an “architect of culture” to describe this new paradigm, offering fresh insights for facing the complexity of managing culture and ethics ( Ethical Systems, 2018 ).

This study focuses on the organizational level. Using a model developed by Gutiérrez Díez (1996) proved remarkably effective to connect elements of culture to conditions and opportunities to build shared ethical culture. It revealed patterns between the types of cultural elements in use, the conditions present in the company, and the organization’s ability to take advantage of opportunities for promoting ethics in the company. Companies can use these findings to establish mechanisms to build individual and organizational ethical abilities and successfully manage their organizational ethics.

2. Managing culture to manage ethics

Culture relates to a unique shared purpose and set of values articulated in a system that internally provides a shared mindset for employees. It shapes how a company interacts with its context, orients its decision-making processes, and performs its functions ( Flamholtz & Randle, 2011 ; Schein, 1990 ). Therefore, culture influences the degree to which ethics becomes embedded within an organization. It makes sense that intentionally managing culture is an appropriate strategy to promote ethics ( Treviño et al., 2014 ).

Gutiérrez Díez (1996) proposed four groups of cultural elements after studying previous approaches based on Schein’s (1990) culture framework of basic assumptions, espoused values, and cultural artifacts. Gutiérrez Díez’s model helps to further define the visible and invisible aspects of culture, a relevant topic in contemporary business literature ( Rick, 2015 ). The types of elements, from minor to major visibility, are normative, symbolic, declarative and structural.

- • Normative elements constitute a framework to explain reality, to understand how it is and how it should be. Examples of these elements are beliefs, implicit values or standards, sanctions, or taboos.

- • Symbolic elements include rites, ceremonies, the physical appearance of facilities, attire, logos, exemplary people or heroes, organizational codes, stories, and myths, and group jargon that create feelings of unity among employees.

- • Declarative elements are statements and formal declarations of mission, vision and values statements, codes, industry pledges, public messages, or internal messages to employees.

- • Structural elements involve organizational structures and visible procedures using the previous elements, including organizational charts and hierarchies, communication and dialogue channels, internal participation mechanisms, and human resource management ( Gutiérrez Díez, 1996 ).

Literature and practice identified three main steps in the process of designing and managing organizational culture. The first step is the definition or redefinition of shared values that the company declares and communicates. The second step is using those values in decision making, inculcating them into organizational life and practices. Finally, the alignment of policies and procedures with the values affirms and consolidates culture in signs and observable behaviors in the company ( Arthur W. Page Society, 2012 ; Treviño et al., 2014 ). As a result, the different elements of culture develop as the company evolves; thus more evolved, mature companies present a greater variety of cultural elements.

Still, the incorporation of ethics cannot be taken for granted in the complex process of culture management. All too often, companies do not use ethical principles in culture management or in establishing a hierarchy of organizational values. For ethics to permeate the organization, the steps of culture management should incorporate ethical values in order to build ethical cultures ( Grandy & Sliwa, 2017 ).

Cultures are ethically sound when the shared set of values is ethically conceivable and credible both inside and outside of the company. Employees must perceive decisions as ethically consistent with their personal values, so that they and the groups they participate in are committed to acting according to this common ethical framework and to revisiting it as new obligations arise ( Haski-Leventhal et al., 2015 ; Rothschild, 2016 ). At the same time, political and social agents outside of the company must see the business culture in this same way for ethics to take hold over time.

But even when managers are committed to orienting organizational culture ethically, they may not know how to effectively integrate ethics. Moreover, two companies with similar conditions can also differ in the way and extent to which they incorporate ethics ( Eccles et al., 2014 ). So how does ethics permeate organizations to create ethical cultures and encourage moral behavior? What are the cultural elements influencing ethics to take root in culture?

3. Finding patterns in how companies encourage ethics

To answer these questions, we have studied the real experiences companies have had incorporating ethics in their cultures. We analyzed experiences of 18 businesspeople diverse in terms of age, seniority, and leadership positions. Their companies varied in size and type of industry, and they operated in two countries with different cultural, political, and regulatory frameworks on two different continents. All participants interviewed were engaged in ethical forums promoted by university centers of applied ethics. These executives have been participating, some for many years, in a group that meets regularly to discuss ethics in a confidential setting, allowing a learning community to form over time. They are a sample of motivated, ethically aware leaders in high- and medium-level positions who are willing to share information about their companies based on relationships they held with each of the ethics centers over time. We felt it likely that we would be able to study the ethical evolution of culture in their companies in enough detail to truly examine decision making and other actions taken in these companies in the context of promoting ethics in organizational cultures.

We started the study at the Centre for Applied Ethics at Spain’s University of Deusto, with nine men and three women. In three half-day sessions, this learning community analyzed two real cases of cultural change and discussed them with experts to identify patterns of ethics pervasiveness. In the U.S., we posed the same questions answered in Spain to another six businessmen from the learning community at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Individual semistructured interviews with participants at their companies helped us reconstruct the ways ethics had been introduced. The analysis of data confirmed and enriched the patterns identified in Spain. As a final step, we presented our conclusions to the learning community in Spain for further discussion and validation.

Our study, although its sample is small, meets conditions for the validity of findings ( Guest et al., 2006 ). But some characteristics of participants may introduce bias, so further studies, with a wider group of companies and incorporating greater participant diversity, are required to confirm and complete the patterns identified here.

3.1. Getting ethics into organizations

From the data we collected, patterns emerged around three aspects. First, we identified some consistent situations with similar characteristics that companies used to embed ethical principles in corporate culture. We named the three types of situations opportunities. These opportunities correlate well with the main stages of building organizational culture, so we used them to classify our findings. Second, we identified three conditions present in companies successful at promoting ethics in their cultures. Finally, we found that a mix of cultural elements, rather than overreliance on one or two types, contributed to ethics in the culture. More mature companies used a greater array of elements and had more and better developed practices for promoting ethics.

Opportunities of the first type, which we refer to as turning points, are challenging situations rife with difficulty, uncertainty, or complexity. These situations are opportunities to introduce and incorporate ethics. A second type of opportunity emerged around decision-making processes , which can be informed by ethics. Finally, transmission of ethics in culture, resulting in the broader dissemination and further strengthening of the norms shared throughout the company, is another opportunity to affirm culture. In some stories, participants described companies’ abilities to leverage one situation for more than one type of opportunity. For example, they leveraged staff turnover—a turning point—not only for introducing but also for affirming ethics; or they used development of ethical skills—an example of transmission— to both affirm and use values ( Table 1 ). This suggests a cyclical dynamic in the process of introducing, using, and affirming ethical values ( Lozano, 2009 ; Treviño et al., 2014 ).

Examples of opportunities

| Examples of opportunities | Leveraged for |

|---|---|

| Challenging situations rife with difficulty, uncertainty, or complexity that buck current culture or practices. | |

| External | |

| Introducing values | |

| Introducing values | |

| Introducing values | |

| Introducing (in one case, also using) values | |

| Internal | |

| Introducing values | |

| Introducing values | |

| Introducing values | |

| Introducing (in a few cases, also affirming) values | |

| Introducing (in one case, also using) values | |

| in which realities test existing norms and policies. | |

| Decisions about policies, products, or services | Using values |

| Operational decisions | Using values |

| Decisions about procedures | Using (in one case, also affirming) values |

| Communication and transmission of ethical practices and norms. | |

| Deployment, standards of services, or cultural norms in individual behavior | Affirming values |

| Training of new employees | Affirming values |

| Some individuals’ lack of ethical motivation | Affirming values |

| Measuring and developing ethical skills | Affirming (in one case, also using) values |

We found three conditions that, when present in companies, made it easier for them to leverage opportunities to promote ethics in the organization. The first condition was a responsibility to society , implying awareness and acceptance of the company’s role in society beyond economic transactions. When this existed, participants confirmed that the company engaged with social agents, assumed its social duties, and held itself accountable ( Aßländer & Curbach, 2014 ; Dembinski, 2011 ). The second condition is the respect of moral autonomy and a climate of mutual trust , which is when the moral arguments or ethical concerns of all individuals are heard in situations that affect them or in which they have expertise. The final condition is ethical deliberation, the main principles of which are ( List & Pettit, 2011 ; Stansbury, 2009 ):

- • The use of information to clarify the ethical dilemma;

- • The respect of individuals’ moral autonomy that allows a deliberative process to reach a consensus based on moral arguments;

- • The consideration of downstream effects of the decision; and

- • Sharing the motivations behind that decision in a transparent way throughout the company.

3.2. Patterns of conditions and cultural elements that support ethics

Participants described the evolution of ethical culture in their companies, and we identified significant coincidences in sets of conditions coupled with specific cultural elements put in place to leverage opportunities ( Table 2 ). Although we asked about successful experiences, participants also discussed inhibitors working against the pervasiveness of ethics in culture that also supported the patterns. For example, participants reported that if organizational conditions were not present, cultural elements identified as enablers of leveraging opportunities to promote ethics would not be influential.

Patterns of opportunities, conditions, and cultural elements

| Opportunities | Conditions | Specific elements of culture |

|---|---|---|

| Turning points | Sense of responsibility to society | Enablers of ethical leadership |

| beliefs, rules | ||

| statements, codes | ||

| exemplary people | ||

| Respect for moral autonomy/climate of trust | Attention to social or individual values | |

| participation control systems | ||

| HR management | ||

| external consultants, country profiles | ||

| Decision-making | Ethical deliberation conditions | Frameworks for decision-making |

| policies | ||

| beliefs, rules (mainly for startups) | ||

| Sense of responsibility to society | Structures for responsibility, authority, and accountability | |

| organizational charts | ||

| arbitration mechanisms | ||

| supervisors (ethical senior leaders) | ||

| Respect for moral autonomy/climate of trust | Consolidation of ethical deliberation conditions | |

| info systems | ||

| participation channels | ||

| communication | ||

| Development of ethical motivation and competence | ||

| HR training | ||

| Incentives and reward systems | ||

| Transmission of culture | Respect for moral autonomy/climate of trust | Description of culture |

| mission and values statements | ||

| Means of transmitting culture | ||

| HR management (tone at the top, competencies) | ||

| internal communication | ||

| organizational charts | ||

| Enablers of consistency in implementation | ||

| benchmarking | ||

| measuring and control systems | ||

| reporting and compliance systems | ||

| exemplary people, stories, and myths |

While the study focused on organizational factors, an unprompted, recurring reference to individual capabilities emerged, indicating their essential role in the success of iterative learning in culture management. All participants mentioned the importance of individual ethical attitudes and competencies. For example, participants cited reflection and learning capabilities ( Treviño et al., 2014 ). The specific individual factors emerged largely in the six interviews conducted in the U.S., which could be due to the different methodologies used in the two locations. Therefore, our observations about leadership skills and competencies from this study are only a promising starting point; more research may discern whether there are indeed patterns of individual moral capabilities that also contribute to promoting ethics in workplaces.

The patterns shed light on the mechanisms by which conditions and cultural elements influence the pervasiveness of ethics in the company. The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics used the patterns in the design of a World Economic Forum survey about creating ethical culture conducted among 99 respondents, confirming their ability to shed light on the organizational processes ( Skeet & Guszcza, 2020 ). The next subsections explain the mechanisms in each type of opportunity that we were able to identify ( Table 2 ).

3.2.1. Mechanisms to introduce ethics

When companies find themselves at turning points opportune for introducing ethics, they should decide whether to incorporate new principles or values to reinforce their organizational ethics. These turning points may be external or market-based, such as pressure from major stakeholders, unfavorable economic conditions, or legal or regulatory changes, or they may be internal, such as changes in leadership, staff turnover, conflict resolution, or poor economic performance ( Aguinis & Glavas, 2012 ). Indeed, large companies in both the U.S. and the EU have had to address issues of ethics and corporate culture due to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines (U.S.) and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. We even observed some companies intentionally creating turning-point opportunities by rotating employees through different assignments so someone in a new role could introduce ethics from a fresh perspective. Several companies used outside consultants as a mechanism for generating turning-point opportunities that would promote ethics.

When the first condition, the sense of responsibility to society, was present, it allowed leaders to take advantage of all these turning points , including changes in procedures, to meet sociological and cultural diversity or to reinforce social responsibility as the company grew. We also observed evidence of the second condition, the respect for individual moral autonomy, especially when individuals were willing to identify issues without fear of retaliation. Several examples highlighted how staff were motivated to uncover ethical problems or conflicts of interest and how people were empowered to make recommendations even to reverse prior decisions, thus creating turning points.

The most commonly mentioned cultural elements during turning points were those enabling formal or informal ethical leadership or bringing attention to social or individual ethical values ( Table 2 ). Spanish participants were more likely to mention normative elements in turning points, while North Americans referred more often to declarative elements, which may be due to cultural differences. Some of the specific symbolic elements mentioned in both locations included exemplary people as promoters of ethics, attention to legacy by founders, and ceremonies observing volunteer work outside the company, suggesting that role models can be highly influential in moral engagement ( Appelbaum et al., 2007 ). One company developed country profiles—a structural element—to improve cultural sensitivity in preparation for future turning-point opportunities in different settings around the globe.

3.2.2. Mechanisms fostering ethical decision-making

We found that opportunities to use ethics arise in decisions about policies, products or services, and procedures, as well as in operational decisions. Ethical decision-making is critical in managing ethics in organizations ( Bowen, 2004 ; Lehnert et al., 2015 ). Our respondents described decisions that led to changes in policies, codes, or internal messages, favoring the spread of values throughout the company and showing the ability of the company to leverage the connection between two of the steps of culture management: the use of and the affirmation of values.

Although three conditions were present in the decision-making examples, two of them seem to be most relevant. Participants mentioned specific examples of ethical deliberation in decision-making situations entailing individual accountability and involving people in the creation of certain standards for which they were going to be held responsible. Participants, especially in the U.S., mentioned a sense of responsibility to the society in which the company operates when making decisions related to policies or procedures affecting stakeholders in diverse cultural or social contexts. Moreover, in the absence of either a sense of responsibility to society or of conditions conducive to moral deliberation, companies were less likely to use ethics when making decisions. In one example, the company was more interested in appearing neutral, in terms of its impact on society, than in making any value judgment about what the right thing to do would be in certain circumstances. The company did not expect to be held accountable for the downstream implications of its decisions.

The cultural elements drawn upon in the use of ethics included normative and declarative elements that shaped decision-making frameworks, and structural elements allowing companies to establish or clarify responsibility and accountability, to support the conditions for ethical deliberation, and to develop ethical motivations and abilities. These elements aim to clarify rather than to impose how ethics can be used ( Bowen, 2004 ; List & Pettit, 2011 ) ( Table 2 ). Interviewees in startups mentioned normative elements more, while people in more established companies mentioned declarative and structural elements, reinforcing how critical these implicit elements are when a company is in its earliest days and has not yet developed declarative and structural elements.

Ethical decision-making can be inhibited by a lack of certain conditions or by a mix of cultural elements. In one case, the interviewee assured us that all employees were free to confront management, which sounded admirable in principle. But he went on to say there were no mechanisms in place to consult people affected by decisions or to share the reasons behind them. In other words, even when there is a will to respect moral autonomy, it is hard for decision-making to follow ethical principles if the conditions for ethical deliberation are absent. Additionally, a lack of policies that spell out responses for employees in specific situations, both when dealing with management and with customers, created voids for ethical decision-making.

3.2.3. Mechanisms involved in affirming ethics

Companies that successfully leverage ethics find a way to lock it into their culture, promoting and demonstrating coherency between values and behavior. Examples of these opportunities are processes for deploying standards or cultural norms, or for developing and measuring ethical motivation and skills. As we saw with turning points, companies also intentionally create opportunities for transmission of culture ( Table 1 ). For instance, some companies approached renewals of policies or codes—opportunities to introduce ethics—as training processes to strengthen the transmission of ethical standards throughout the organization.

Respect for individual moral autonomy seemed especially important in building a shared ethical mindset and values. Awareness and acceptance of social reality helped companies deal with the diversity and pluralism of their employees. Elements useful in affirming culture allow for shared comprehension of corporate culture and for awareness of the consistency in the application of values across the company ( Table 2 ).

Declarative elements describing culture were used early and often as enablers of transmitting culture in companies. And structural elements, such as formal training procedures, “tone at the top” programs, internal communication channels, and deployment of compliance and ethics responsibilities, were means for transmitting the culture and promoting shared values. These elements were correlated with enhanced awareness and moral capabilities in employees ( Warren et al., 2014 ) and with the development of ethical behavior and practices in organizations ( Treviño et al., 2014 ). Other examples of ways to bolster company values included drawing up organizational charts that reflect values and setting up a foundation to reinforce local community engagement.

Finally, symbolic and structural elements enabled coherency within the companies we examined. Structural elements such as measurement, assessment, reporting, and reward systems to operationalize declarative elements were cited by several companies as influencing awareness of and motivation to practice ethics ( Burford et al . , 2016 ; Griffiths et al., 2018 ) and also in creating an environment that inhibits deviant behavior. Two companies described using “culture buddies” as an orientation method to transfer culture to newer employees, suggesting this could be an example of ethical “contagion”—the idea that exposure to ethical behavior encourages more ethical behavior ( Appelbaum et al., 2007 ).

In cases where ethics failed to take hold, the lack of exemplary leaders—that is, when leadership talked the talk but didn’t walk the walk—inhibited development of a culture of ethics. A lack of balance in the types of cultural elements identified as enablers was another inhibitor for transmitting culture effectively. One company relied heavily on declarative elements and normative elements—mission statements and related slogans, and the beliefs of founders—but did not deploy a balance of structural or symbolic elements to ensure their implementation. The company did not promote a collective learning process to achieve a shared hierarchy of values, and it has suffered from a disconnect similar to Enron ( Sims & Brinkmann, 2009 ). This company is now known for having a strong mission and culture, but not one that encourages ethical behavior.

In startups, survey participants cited as inhibitors pragmatic normative elements—a focus on legal, not ethical considerations—and the influence of having a poor array of cultural elements. For example, they mentioned a lack of formal declarative cultural elements (e.g., mission and values, policies and decision-making criteria); scant symbolic elements (e.g., a lack of ethical sensibility and moral competency in leaders, or few sanctions for behavior that went against stated norms or values); or an absence of structural elements (e.g., channels for participation beyond informal meetings). To test these tendencies would require further studies focusing on a larger number of startups. When affirming values, conditions and cultural elements interact, reinforcing the culture and the consistency with which it is implemented, and thus strengthening the procedures and practices that engender individual and organizational accountability.

4. Toward a culture of ethics: A roadmap

More and more companies are intentionally managing culture as a strategy for organizational ethics. But there are currently few practical tools and approaches to deal with the complexity of fostering cultures in which ethical considerations are a regular part of business discussions and decision-making. The patterns identified in this study show a dynamic relationship among opportunities, conditions, and specific sets of cultural elements, thereby uncovering some of the mechanisms of ethics pervasiveness. Further, these patterns show the importance of using different types of cultural elements to leverage opportunities when conditions are present. An old framework ( Gutiérrez Díez, 1996 ) used for the analysis of cultural elements offered new insights to uncover mechanisms by which ethics is instilled in companies.

Our evidence-based patterns can help managers encourage ethics in their organizational culture by leveraging foreseeable or even intentionally created opportunities to incorporate ethics ( Figure 1 ). The starting point for ethical development within a company is to explore and reflect upon its current culture. The patterns observed in this study support regular culture assessments that include reviewing cultural elements and assessing the presence or absence of conditions that can lead to the introduction, use, and affirmation of ethics. Through these types of assessments, companies can identify conditions and cultural elements worth promoting to encourage ethics. Once the company has acted on its findings to drive cultural change, a reassessment starts the process anew. In this way, culture management becomes a practical, technical skill, measuring outcomes and developing an organization that can learn about itself.

Manager’s actions using patterns

Ethical aspects

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and research committees in each location of the study, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study has received no external funds.

Declaration of competing interest

Cecilia Martinez Arellano declares that she has no conflicts of interest. Pedro M. Sasia Santos declares that he has no conflicts of interest. Ann G. Skeet has the following conflicts of interest:

- • During the time the research was conducted, a relative of Ann Skeet's worked at one of the companies where the interviews for this study were conducted. The company is a multinational enterprise with over 80,000 employees, and there is no direct connection between him and the people who were interviewed as part of this study.

- • The Center for Applied Ethics where Ann Skeet works receives general marketing sponsorship support for business ethics programming that includes events and business ethics internships from some of the companies interviewed, but not support specific to this study. Interns participating in the center’s business internship program worked at one of the companies where the research was conducted.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the members of the learning community of academics and practitioners focused on business ethics training and research at Directica, the Centre for Applied Ethics at the University of Deusto, and also the companies and businesspeople of the Markkula Center’s business ethics partnership at Santa Clara University that have taken part in this study.

- Aguinis H., Glavas A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management. 2012; 38 (4):932–968. [ Google Scholar ]

- Appelbaum S.H., Iaconi G.D., Matousek A. Positive and negative deviant workplace behaviors: Causes, impacts, and solutions. Corporate Governance. 2007; 7 (5):586–598. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arthur W. Page Society . 2012. Building belief: A new model for activating corporate character and authentic advocacy. https://knowledge.page.org/report/building-belief-a-new-model-for-activating-corporate-character-and-authentic-advocacy/ Available at. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aßländer M., Curbach J. The corporation as citizen? Towards a new understanding of corporate citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics. 2014; 120 (4):541–554. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowen S. Organizational factors encouraging ethical decision making: An exploration into the case of an exemplar. Journal of Business Ethics. 2004; 52 (4):311–324. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burford G., Hoover E., Stapleton L., Harder M. An unexpected means of embedding ethics in organizations: Preliminary findings from values-based evaluations. Sustainability. 2016; 8 (7) [ Google Scholar ]

- Business Roundtable . 2019, August 19. Business Roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote ‘an economy that serves all Americans’ https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans Available at. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dembinski P. The incompleteness of the economy and business: A forceful reminder. Journal of Business Ethics. 2011; 100 (1):29–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- DiStaso M. Arthur W. Page Society; 2017, May 22. CCOs on building corporate character: More work to be done. https://page.org/blog/ccos-on-building-corporate-character-more-work-to-be-done Available at: [ Google Scholar ]

- Dolan S.L., Raich M. The great transformation in business and society: Reflections on current culture and extrapolation for the future. Cross Cultural Management: International Journal. 2009; 16 (2):121–130. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eccles R.G., Ioannou I., Serafeim G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science. 2014; 60 (11):2835–2857. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ethical Systems . 2018. Featured ethics expert and culture architect: Caterina Bulgarella. http://ethicalsystems.org/content/featured-ethics-expert-and-culture-architect-catarina-bulgarella Available at. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flamholtz E., Randle Y. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 2011. Corporate culture: The ultimate strategic asset. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman R.E. The new story of business: Towards a more responsible capitalism. Business and Society Review. 2017; 122 (3):449–465. [ Google Scholar ]

- Garriga E., Melé D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics. 2004; 53 (1):51–71. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grandy G., Sliwa M. Contemplative leadership: The possibilities for the ethics of leadership theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics. 2017; 143 (3):423–440. [ Google Scholar ]

- Griffiths K., Boyle C., Henning T.F. Beyond the certification badge: How infrastructure sustainability rating tools impact on individual, organizational, and industry practice. Sustainability. 2018; 10 (4) [ Google Scholar ]

- Guest G., Bunce A., Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006; 18 (1):59–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gutiérrez Díez E.J. Universidade Compultense de Madrid; Madrid, Spain: 1996. Evaluación de la cultura en la organización de instituciones de educación social. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haski-Leventhal D., Roza L., Meijs L.C. Congruence in corporate social responsibility: Connecting the identity and behavior of employers and employees. Journal of Business Ethics. 2015; 143 (1):35–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehnert K., Park Y., Singh N. Research note and review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: Boundary conditions and extensions. Journal of Business Ethics. 2015; 129 (1):195–219. [ Google Scholar ]

- List C., Pettit P. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2011. Group agency: The possibility, design, and status of corporate agents. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lord R.G., Brown D.J. Leadership, values, and subordinate self-concepts. The Leadership Quarterly. 2001; 12 (2):133–152. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lozano J.M. Trotta; Madrid, Spain: 2009. La empresa ciudadana como empresa responsable y sostenible. [ Google Scholar ]

- NACD . 2017. Culture as a corporate asset. https://www.nacdonline.org/insights/publications.cfm?ItemNumber=48252 Available at. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rick T. Ameliorate ; 2015, August 28. Organizational culture is largely invisible. http://www.torbenrick.eu/blog/culture/organizational-culture-is-largely-invisible/ Available at. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothschild J. The logic of a cooperative economy and democracy 2.0: Recovering the possibilities for autonomy, creativity, solidarity, and common purpose. The Sociological Quarterly. 2016; 57 (1):7–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schein E.H. Organizational culture. American Psychologist. 1990; 45 (2):109–119. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sims R.R., Brinkmann J. Thoughts and second thoughts about Enron ethics. In: Garsten C., Hernes T., editors. Ethical dilemmas in management. Routledge; Abingdon, UK: 2009. pp. 117–130. [ Google Scholar ]

- Skeet A.G., Guszcza J. 2020, January 7. How business can create an ethical culture in the age of tech. The European Sting . https://europeansting.com/2020/01/07/how-businesses-can-create-an-ethical-culture-in-the-age-of-tech/ Available at. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stansbury J. Reasoned moral agreement applying discourse ethics within organizations. Business Ethics Quarterly. 2009; 19 (1):33–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Treviño L.K., Den Nieuwenboer N.A., Kish-Gephart J.J. (Un)ethical behavior in organizations. Annual Review of Psychology. 2014; 65 :635–660. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Warren D.E., Gaspar J.P., Laufer W.S. Is formal ethics training merely cosmetic? A study of ethics training and ethical organizational culture. Business Ethics Quarterly. 2014; 24 (1):85–117. [ Google Scholar ]

- Watson G.W., Papamarcos S.D., Teague B.T., Bean C. Exploring the dynamics of business values: A self-affirmation perspective. Journal of Business Ethics. 2004; 49 (4):337–346. [ Google Scholar ]

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Chipotle

An Organizational Ethical Dilemma Essay Examples

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Chipotle , Ethics , Customers , Ethical , Food , Stakeholders , Pets , Law

Words: 1300

Published: 03/08/2023

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Introduction

It is common for an organization to fall into some predicament once in a while. The concept reveals itself by the aspect of organizations having contingency plans that leverage them in the case of an impromptu or ongoing scandals. I have always observed that companies have insurance covers for such incidences. Most of the problems that organizations are likely to encounter include organizational ethical dilemmas. Recently, one of the well-known fast food joint, Chipotle Mexican Grill, alias chipotle. Chipotle encompasses a chain of fast food restaurants. The chain is allegedly accused of breaching the food policy protocol regulations by using dog and cat meat as part of their dishes. The situation has led to the chain facing food safety lawsuit. The ethical dilemma that Chipotle is facing entails the alleged claims on food security and making consumers sick against losing the market share and the shareholders. In this paper, I will provide my insight on the organizational-ethical dilemma that the Chipotle chain of restaurants are facing and how the organization is dealing with the crisis in light of the eight steps model of ethical decision making by Trevor and Nelson.

Key facts about Chipotle

The Mexican chipotle grill has had a rather rough time in the recent past. Just a recap, I did see that Chipotle had been sued by the federal government over compensation of stockholders in the year 2015. The same year and the corresponding lawsuits saw the sales decline by over 14.6% (Blackmore, 2016). Consequently, lawsuits by investors have been imminent. The current scenario is an alleged case of the organization using dog and cat meat as part of their dishes. The situation to me is a scary one since I do not think I can stand the fact that I may have taken a pizza or any meat affiliated product from them. It is reported that the FDA inspectors came across some live dogs and cats and correspondingly saw dead corpses of the same somewhere near the chipotle factory in Denver. The case was reported to the local authorities (Blackmore, 2016). The intriguing and weird question that I keep on asking myself is, “why would such a popular and high ranked chain result to such measures if at all the allegations are true?”

The ethical issue involved

Let me assume for a moment that the allegations are true and have some solid, irrefutable evidence. First, use of dog and cat meat is not legal by any means. If someone was to justify the case since I know of some nations that eat dog meat, then here in our country it would be awkward and unethical. It is expected that any food restaurant used the recommended and expected the raw material to synthesize and prepare the dishes. Failure to observe that is highly unethical and against the law. Inability to follow and keep the ethical guidelines is termed as unethical (Trevino & Nelson, 2014). The public has raised concerns on the same, and there is an imminent situation of conflict which indicates a sign of ethical collapse (Jennings, 2006).

Relevant Individuals and Groups

The key people involved here in my view are the stakeholders and the consumers. In my interpretation, the stakeholders have a lot to lose. If the business collapses entirely, then their investment is in jeopardy. The consumers on the other hand risk disease as a result of the extraordinary dishes they are served at the Chipotle restaurant. Trevino and Nelson, (2014) assert the customers, and the stakeholders are likely to suffer the most. In my view, the leadership has failed to establish and honor the food policy protocol and that is an indication of a failed leadership (Ciulla, 2005).

Possible Consequences and specific Alternative Actions

No company wants to see the good name and reputation go down the drain for whatever reasons. In the case that the situation occurs, companies will try their best to salvage the situation (Lamberton, Mihalek & Smith, 2005). Chipotle Mexican Grill is likely to suffer a significant loss both concerning the clients and the stakeholders. As an alternative, the company is offering the customers vouchers and free meals at the restaurants as a way of reassuring and attracting the customers. Additionally, the firm is holding general meetings with the stakeholders to explain and reassure them of their investment (Blackmore, 2016).

Relevant Obligations from my analysis of the dilemma

The Chipotle chain has a duty by law and by ethics to ensure that they provide their customers with what they promise. Additionally, they also need to engage the stakeholders in meetings and ensure that they have a consensus that does not see the investors pulling out (Clegg, Kornberger, & Rhodes, 2007).

Community Standards of Integrity that provides me with guidance

Service with integrity encompasses my day to day activities at my workplace and other social interactions. Integrity is a virtue that sees one doing the right things, the right manner, the right time, and place. If the Chipotle had observed service with integrity, then they may not have landed at the current predicament (Lamberton, Mihalek, & Smith, 2005).

Possible creative alternate actions

The Chipotle Mexican Grill have a daunting and tricky task ahead of turning the tables around. They have to invent some innovative and highly lucrative tactics. One of the tactics is discrediting the alleged evidence as malicious and false. Probably a plan by the competitors to downplay them. Moreover, they can disregard the accusations and focus on clearing their name while at the same time providing better and quality services to the customers (Hatvany, & Strack, 1980). In my opinion, the strategy turns tables around, though slowly but effectively.

What is my gut telling me?

I have a feeling that the case against the Chipotle restaurants has an imminent malicious background. If I am going to inculcate other additives the main dish of my customers with off the menu items, then I have to be smart. The Chipotle could not have been possibly that careless to leave evidence behind, mostly in an area frequently visited by health inspectors. That is an act of deliberated suicide.

The organizational-ethical dilemma facing the Chipotle group of the restaurant is dangerous in its state. The shareholders and the customers have questions and doubts regarding the overall credibility of the organization. Standards and responsibility are seen to have been lost or neglected by the company. However, in my honest view, the company seems amicably and responsibly responding to the adversity and may soon recover. Some of the positive actions that they are engaging include holding meetings with stakeholders, communicating as needed to the customers and even offering free vouchers for meals and other shopping to the customers. To me, this may just be the beginning of a long path to recovery.

Blackmore, W. (2016, January 9). Chipotle Sued Over Food-Safety Scandal. Retrieved from Take Part: http://www.takepart.com/article/2016/01/09/chipotle-investor-lawsuit. Ciulla, J. B. (2005). The state of leadership ethics and the work that lies before us. Business Ethics: A European Review, 14(4), 323-335. Clegg, S., Kornberger, M., & Rhodes, C. (2007). Business ethics as practice. British Journal Management, 18(2), 107-122. Hatvany, N., & Strack, F. (1980). The impact of a discredited key witness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 10(6), 490-509. Jennings, M. M. (2006, August). The seven signs of ethical collapse. In European Business Forum (Vol. 25, No. Summer, pp. 32-38). Lamberton, B., Mihalek, P. H., & Smith, C. S. (2005). The tone at the top and ethical conduct connection. Strategic Finance, 86(9), 36. Trevino, L. K., & Nelson, K. A. (2014). Managing business ethics: Straight talk about how to do it right. 6th Edition. New York: Wiley & Sons.

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 2019

This paper is created by writer with

ID 260367081

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Example of article review on attachment theory, example of essay on cultural identity, degree objective admission essay examples, working mother essay, function concepts in a residential air conditioning service and installation company essay sample, research paper on conservation genetics, central serous retinopathy a disease overview case study examples, research paper on the present and future of computer based espionage and terrorism, free essay on management memo marine enterprises, looking and seeing in raymond carvers cathedral essay sample, men and women earlier times vs today essay examples, example of research paper on sigurd the volsung, essay on telemetry and ekg monitoring, free essay on evaluating the effect on total quality management on road constructions in nigeria, free book review on buddhism, breach of the peace essay example, strengths case study examples 2, term paper on ad choice thirsty for beer australian beer commercial 2014, protection thesis proposals, bridge thesis proposals, california thesis proposals, acceptance thesis proposals, house thesis proposals, inhibition research papers, nutrient research papers, bench research papers, metric research papers, practical application essays, psychosexual development essays, calender essays, juror essays, suture essays, humanization essays, bookshop essays, karaoke essays, humming essays, mccarthy essays, martial essays, child care essays, rearing essays, unconsciousness essays, brain damage essays, remedy essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

- What are research briefings?

- How it works

- The Oxford Review Store

- The DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion) Impact Series

- What is DEI? The Oxford Review Guide to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

- The Oxford Review DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion) Dictionary

- The Essential Guide to Evidence-Based Practice

- The Oxford Review Encyclopaedia of Terms

- Video Research Briefings

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Competitive Intelligence From The Oxford Review

- The Oxford Review Mission / Aim

- How to use The Oxford Review to do more than just be the most knowledgeable person in the room

- Charities The Oxford Review Supports

- Terms and conditions

- Member Login

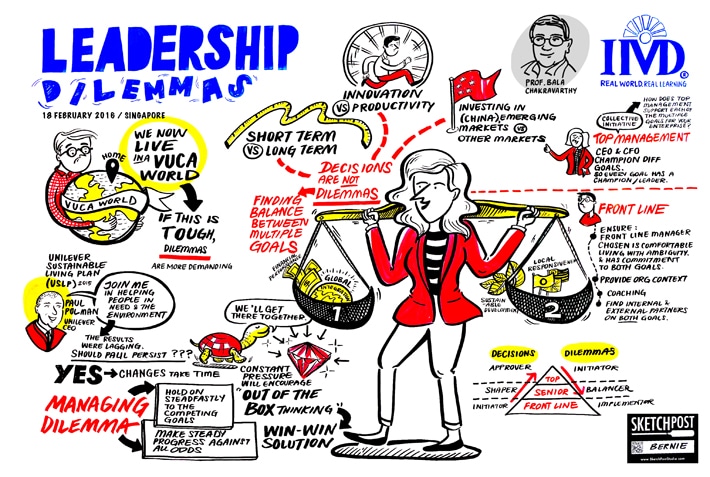

6 ways organisations deal with dilemmas

Blog, Coaching, Human Resources, Leadership, Learning, Management, Organisational Change, Organisational Development, Research

Following on from the previous post ‘New research: Organisational responses to dilemmas and emergencies’ in this post I will look at what the research says about the 6 ways organisations deal with dilemmas.

Be impressively well-informed

Get your FREE organizational and people development research briefings, infographics, video research briefings, a free copy of The Oxford Review and more...

Be impressively well-informed and up-to-date

Success! Please check your email. If you haven't got anything from us (check your junk mail) the email address may not be quite right - please try again.

There was an error submitting your subscription. Please try again.

It has previously been found that there are six main ways organisations deal with these secondary order tensions, paradoxes and dilemmas:

- Denial. The organisation just doesn’t recognise or see the secondary order tensions, paradoxes and dilemmas and operates as if they don’t exist.

- Cosmetic responses . This is where organisations take action that appears to deal with them, but don’t. For example where they hold a meeting with all the concerned departments and agencies to talk about and agree a set of actions to deal with the issues, without executing the actions required.

- Selection. This is where the organisation selects which secondary order tensions, paradoxes and dilemmas to deal with and either ignores those that are just too hard to deal with or those that they haven’t got a ready solution to.

- Alternation. This is where the organisation flops from dealing with one issue or pole of a dilemma to another, but doesn’t actually deal with them together. In effect the organisation keeps switching its focus and swinging between the issues without seeing them as a whole picture. As a result they often fail to see the connections between issues.

- Segmentation. This is where different departments or units are dealing with and trying to solve different secondary order tensions, paradoxes and dilemmas without coordination.

- Transcendence. The authors note that this occurs when “when organizations openly acknowledge the dilemma and tensions confronting them, accept it as a paradox, and attempt to work out creative responses. Organizations adopting this approach would emphasize continuous vigilance, adaptability, learning, creativity, improvisation, and “going with the flow.” These organizations would have flexible structures, communication-intensive processes, and experimental approaches to problem solving.”

Usually, because transcendence responses require constant and consistent vigilance and management, they are always in danger of degenerating into one of the other types of responses.

Additionally because denial, selection and cosmetic responses appear to be the least costly, especially in terms of effort, creativity and time, they are the most frequent responses in most organisations. However, as previous research has shown, these three strategies lie at the heart of the failure of most complex inter-agency/inter-departmental responses.

This table shows the properties of each response type:

Transcendence responses appear to be the most costly initially because it necessitates co-operative problem solving and consensus building, which takes time and high levels of engagement.

In the next post I will look at the the conclusions of this research and what it means for your organisation.

Be impressively well informed

Get the very latest research intelligence briefings, video research briefings, infographics and more sent direct to you as they are published

Be the most impressively well-informed and up-to-date person around...

Success! Now check your email to confirm that we got your email right. If you don't get an email in the next 4-5 minutes something went wrong: 1. Check your junk folder just in case 🙁 2. If it's not there either, you may have accidentally mistyped your email address (it happens). Have another go. Many thanks

You may also like

Research review of the balanced scorecard, podcast: what are the workplace issues of neurodiversity, subscribe to our newsletter now.

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

- Call to +1 844 889-9952

Organizational Ethical Dilemmas

| 📄 Words: | 1829 |

|---|---|

| 📝 Subject: | |

| 📑 Pages: | 6 |

| ✍️ Type: | Essay |

These days organizations are expected to be socially responsible and engage in ethical decision-making. The paper aims to explore the main moral issues companies encounter and examine how they can be resolved. The study is based on the analysis and summarization of the existing literature covering business dilemmas, as well as different aspects of organizational ethics. The author also uses the case of Apple Inc. as an example of a company that abides by certain moral standards and expectations. While making decisions organizations have to consider multiple stakeholders, such as customers, employees, and the environment. There are also benefits of engaging in programs aimed at enhancing the communities well-being. Therefore, companies aspiring to achieve better public recognition should acknowledge these factors during their operations.

Organizations and Ethical Decision-Making

These days organizations purposes and responsibilities are not seen merely through the framework of legal and financial liabilities. Along with the expectations regarding providing quality goods and services, they are viewed accountable for maintaining workplace diversity, supporting environmental protection, and contributing to the public good. In other words, there are specific standards of social responsibility they have to abide by (Duckworth, 2016). Fulfilling these duties entails facing ethical dilemmas at different levels of a company’s operations, but the successful resolution of these issues can positively contribute to its public image.

First of all, it is essential to understand the basic principles of ethical decision-making. Its key element is proper framing, which implies establishing that the problem is ethical even if other responsibilities are involved (Schwartz, 2017). This demands moral awareness, which requires understanding how the decision-makers actions influence individuals, organizations, or the environment (Schwartz, 2017). Therefore, careful consideration of possible outcomes is demanded to choose the most optimal decision for all the parties involved. For companies, these stakeholders include customers, the environment, employees, and communities.

Marketing Strategies and Production Processes

All economic transactions are based on supply and demand, making customers purchasing power, their needs, expectations, and satisfaction levels the main predictors of an organization’s performance. Therefore, companies focus should be on providing their clients with products that are safe to use and comply with their description. It is not merely a question of economic benefit: state laws protect customers rights to safety, to being heard, and being informed (Weiss, 2014). However, while legally regulated, business operations should also be considered from an ethical perspective. These areas include advertising, product safety, and ecological responsibility.

Ethical Advertising

Many discussions surround the issue of advertising. Companies are legally obliged to give accurate information regarding the product or service they provide (Weiss, 2014). However, they often employ various misleading tactics during their marketing operations which, while not being necessarily punishable, are still rather questionable. For instance, nowadays, with the increase of health-conscious consumers, many companies add “sugar-free” labels to their packaging hiding sugar under lesser-known names (such as dextrose, fructose, maltose). In other cases, clarification is written in a small font that is hard for most consumers to read. While from a legal perspective, it may be considered customers responsibility to educate themselves or be more careful; it is an ethical obligation of an organization to give accurate, easily accessible, and understandable information about the product. Moreover, deceiving clients is unlikely to be an efficient long-term strategy since it undermines trust.

Potentially-Harmful Products

Another ethical issue is connected to advertising such products as fast food, cigarettes, and alcohol, which are associated with many diseases, including obesity, diabetes, addictions, and lung cancer. Many concerns have been expressed regarding certain marketing strategies that glorify unhealthy behaviors, such as consuming high-calories foods or drinking alcoholic beverages (Weiss, 2014). Such advertising can be particularly dangerous if directed to teenagers who tend to be more vulnerable to external influence (Weiss, 2014). Parents raise particular concerns regarding pop-up ads online (Weiss, 2014). The companies should understand that if they advertise potentially harmful products to youngsters, they are not merely dealing with a way to increase sales. From a long-term perspective, it makes them responsible for growing figures in child obesity and alcohol consumption among adolescents.

Safety Concerns

Some products may also have certain defects posing a danger to consumers. It is a legal issue, though surrounded by discussions related to the extent companies should be held responsible for the harm caused by their goods (Weiss, 2014). However, it is also a moral obligation of a trader to make sure their customers are safe. Therefore, having learned about a potentially harmful defect, they should recall their products (Weiss, 2014). For instance, in 2019, Apple recalled some of its 15 MacBook Pro laptops due to a battery fire risk (Gibbs, 2019). Such actions not only help to ensure that the clients are safe and no lawsuits would follow, but it is also an ethical decision that supports the company’s reputation.

Environmental Protection

Organizations should also be accountable for the impact they have on the environment. It is estimated that significant damage to ecology is done through irresponsible production processes (Weiss, 2014). Damage caused by human activity, including greenhouse emissions and uncontrollable use of limited resources, contributes to increases in heart and respiratory diseases and is also linked to climate change and water scarcity (Weiss, 2014). Thus, protecting nature concerns individual lives and societies as a whole. Therefore, companies (which have more resources to harm and more resources to help) should also be aware of their environmental impact. As environmental awareness increases, many businesses start to employ green marketing strategies (such as eco-friendly packaging) using it as a competitive edge (Mahmoud, 2018). However, it should not be merely a way of attracting clients – their actions must align with the principles of sustainability.

Creating Respectful Workplaces

Apart from responsibilities towards customers and the environment, companies have moral obligations to their potential and current employees. They are expected to provide equal opportunities for all applicants and create safe and respectful workplaces for their employees, supporting and enhancing diversity. It is essential to eliminate any differences in status between demographic subgroups (Guillaume et al., 2017). A person’s position in a company should be only influenced by their merit and contribution.

Enhancing Diversity

These objectives can be achieved by developing effective diversity management strategies including recruiting practices aimed at attracting candidates from different backgrounds. However, merely employing people of diverse genders, races, and sexual orientations without creating an appropriate corporate culture is unlikely to be beneficial both for the company and its new staff members. Therefore, many organizations now provide diversity training to raise awareness regarding widespread biases and foster tolerance and better communication (Shaban, 2016). Managers must help their employees to understand and accept their differences (Shaban, 2016). As Guillaume et al. point out, positive attitudes towards diversity and “task and team-related competencies and motivation” are essential for creating respectful and productive workplaces (2017, p. 296).

Leadership also plays a crucial role – managers should avoid expressing any biases and personally contribute to cultivating tolerance and equality (Guillaume et al., 2017). Many global companies also have training programs aimed at different minorities, helping them improve their skills and qualifications. This can ensure that people of a background that made it difficult for them to receive education and training similar to others are provided with an opportunity for professional development.

Apple’s Example

These days the majority of successful companies foster and develop diversity. Creating inclusive teams fulfills their moral responsibilities towards their communities and is also suggested to improve their performance by attracting more talent (Lambert, 2016). One of the leading companies in the world of technology, Apple Inc., also puts a great value on diversity linking it to better innovation (Apple, 2018a). Its recent hiring statistics show that human resources managers try to attract more people from different minority groups (Apple, 2018b). They also claim to have achieved equal pay for similar roles and performances in every country they operate in (Apple, 2018a). Such strategies help to ensure that the company attracts a positive public image by taking care of one of its main stakeholders – employees.

Corporate Volunteer Programs

Benefits to companies.

Another way to provide for better life satisfaction and engagement of workers is through organizing corporate volunteer programs. Such initiatives are aimed at creating a coordinated approach to providing employees with opportunities to contribute to the public good. Some activities they can be involved in include “after-school reading programs, working in homeless shelters, constructing low-income housing, cleaning up community parks” (Longenecker et al., 2012, p. 10).

There are several practical reasons why companies may cultivate such practices. Research shows that employees participation in volunteering contributes to increases in media exposure, brand recognition, and customer loyalty (Longenecker et al., 2012). Moreover, working for the same cause can help employees to bond together widening networking possibilities (Longenecker et al., 2012). Research also shows that such programs increase employee engagement, consequently leading to better performance (Caligiuri et al., 2013). Also, performing different roles while volunteering can help them to improve their organizational or emotional skills.

Benefits to Employees

In addition, there are significant ethical implications of organizational volunteering. As Duckworth (2016) emphasizes, it is critical to remember that employees are also community members. Therefore, working for its benefit can increase employees happiness and life satisfaction, providing them with opportunities to do something meaningful for society. Also, as community members, employees have their own experiences, which make them capable of or interested in improving certain aspects of social life. Moreover, allowing employees to suggest and develop their ideas can help to increase the social responsibility of an organization as a whole (Duckworth, 2016). Therefore, it will enable companies to use their resources to contribute to the public good.

Corporate Volunteering Organization

However, to derive these benefits, it is important to ensure that corporate volunteering programs are organized well. Caligiuri et al. suggest that to obtain long-term benefits for companies, NGOs, and individual employees, companies should “select volunteers for their technical skills (and put them in assignments where they can use them), to provide them with an opportunity to further develop their skills, and to assign them to NGOs that have the tangible resources to sustain the volunteers’ projects after the volunteers leave so the “sense of purpose” among the volunteers is high” (2013, p. 856). Knowing that their contribution will be meaningful in the long run, even if they would not be able to continue working for that cause, can significantly improve volunteers motivation.

Thus, while performing their legal and economic operations, organizations also have to consider multiple ethical dilemmas. They should identify the main stakeholders and how they would be affected by the chosen course of action. In many cases, companies negligence or intention to deceive can harm their clients, employees, or the environment. However, they also have a lot to offer: unique resources they can use to improve individual lives or contribute to the public good. Successful companies these days understand their responsibilities, try to adjust their decision-making process to be more ethical, and take actions to give back to the community.

Apple. (2018a). Inclusion and diversity . Web.

Apple. (2018b). Employer information report EEO-1 . Web.

Caligiuri, P., Mencin, A., & Jiang, K. (2013). Win–win–win: The influence of company‐sponsored volunteerism programs on employees, NGOs, and business units. Personnel Psychology , 66 (4), 825–860.

Duckworth, H. A. (2016). Social responsibility should be participation essential. The Journal for Quality and Participation , 38 (4), 39–40.

Gibbs, Samuel. (2019). Apple recalls 15in MacBook Pro laptops over battery fire risk. The Guardian . Web.

Guillaume, Y. R., Dawson, J. F., Otaye‐Ebede, L., Woods, S. A., & West, M. A. (2017). Harnessing demographic differences in organizations: What moderates the effects of workplace diversity? Journal of Organizational Behavior , 38 (2), 276–303.

Lambert, J. (2016). Cultural diversity as a mechanism for innovation: Workplace diversity and the absorptive capacity framework. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict , 20 (1), 68–77.

Longenecker, C. O., Beard, S., & Scazzero, J. A. (2012). What about the workers? The workforce benefits of corporate volunteer programs. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal , 27(1), 9–12.

Mahmoud, T.O. (2018). Impact of green marketing mix on purchase intention. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences , 5 (2), 127–135.

Schwartz, M. S. (2017). Business ethics: An ethical decision-making approach . John Wiley & Sons.

Shaban, A. (2016). Managing and leading a diverse workforce: One of the main challenges in management. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences , 230 (1), 76–84.

Weiss, J. W. (2014). Business ethics: A stakeholder and issues management approach (6 th edition). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Cite this paper

Select style

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

BusinessEssay. (2022, December 18). Organizational Ethical Dilemmas. https://business-essay.com/organizational-ethical-dilemmas/

"Organizational Ethical Dilemmas." BusinessEssay , 18 Dec. 2022, business-essay.com/organizational-ethical-dilemmas/.

BusinessEssay . (2022) 'Organizational Ethical Dilemmas'. 18 December.

BusinessEssay . 2022. "Organizational Ethical Dilemmas." December 18, 2022. https://business-essay.com/organizational-ethical-dilemmas/.

1. BusinessEssay . "Organizational Ethical Dilemmas." December 18, 2022. https://business-essay.com/organizational-ethical-dilemmas/.

Bibliography

BusinessEssay . "Organizational Ethical Dilemmas." December 18, 2022. https://business-essay.com/organizational-ethical-dilemmas/.

- Consumer Responsibility: Impact on Factory Workers

- Ethics and Workers’ Participation

- Professionalism and Engineering Ethics

- Are Multinationals Free From Moral Obligation?

- Ethical Violations and Challenges

- Citigroup and Subprime Lending

- Ethical Consumption and CSR in Global Supply Chains

- A Method for Evaluating Ethics in an Organization

- Public Relations Professional Ethics

- Professional Ethics and Individual Rights and Freedoms

More From Forbes

Eight common ethical dilemmas business owners face (and how to overcome them).

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Ethical dilemmas are commonplace in society, but when a business experiences one, the impact (and potential fallout) can have a wide reach.

In many cases, ethical dilemmas are challenging to work through because the risk and reward aren't as clear-cut as other types of decisions. This complexity becomes even more convoluted with businesses, as other businesses, customers and employees can all be affected. Below, eight leaders from Young Entrepreneur Council examine some of the more common ethical dilemmas business owners may face and offer their advice on how to overcome them.

Young Entrepreneur Council members offer their tips for how to overcome these ethical dilemmas.

1. Supporting Other Businesses When Money Is Tight

Sometimes business owners have to choose between keeping costs down to survive and supporting other businesses. This is a difficult choice to make and one with significant impact on different people. It helps to find alternative ways to do your part in helping other businesses. It doesn't always have to be about money. If you want to support other businesses and avoid losing money, you could cross-promote other businesses or help in different ways. Keep an open mind and keep looking for solutions and you could come up with interesting ways to help your business and others around you. - Syed Balkhi , WPBeginner

2. Compromising On Product Quality

Compromising on product quality is usually the first place business owners go to make a few extra bucks. Cheaper cost of goods sold looks great on a spreadsheet, but the reality of the situation is your customers will notice. In most industries, the goal is to maximize the lifetime value of the customer. It is very important to put your best foot forward with your product quality and not try to cut corners. If there’s a manufacturing error, don’t sell it. If the software is buggy, don’t ship it. If the food isn't cooked right, send it back. It’s always financially beneficial in the long term to do the right thing. Give the customer the highest quality you can for the money they’re paying you. - Michael Fellows , Patriot Crew

3. Offshoring Your Manufacturing

I once consulted with an entrepreneur who was passionate about manufacturing in the U.S., but who unfortunately found out through market testing that the customers could only tolerate a price point that was too low for this manufacturer to provide. So their ethical dilemma was whether or not to offshore their manufacturing. In the end, they came to terms with the market price, and then, while they chose to manufacture offshore, they ended up forming a strong relationship with the provider and built up enough trust in ethical practices. This was the only way for the small brand to take a toehold in the market. Once they gain enough traction, they hope to move their operations back to the U.S. and command a higher price point. - Kaitlyn Witman , Rainfactory

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024

Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024.

4. Letting Clients Go

Walking away from toxic clients can be a common ethical dilemma. It's hard to know what the right thing to do is if they are bringing good income into your company and there are contracts signed. But if it's a toxic relationship, boundaries need to be set. If those aren't working, the relationship needs to end—as difficult as that can be. - Diego Orjuela , Cables & Sensors

5. Responding To Employee Social Media Behavior

The question of how to respond to employees' social media behavior outside of work is a difficult one. It's sometimes hard to draw the line. It's entirely justifiable to fire an employee over poor behavior on their personal social media accounts, but it's sometimes tricky to determine exactly when that line is crossed. In today's day and age, there's no excuse for crossing a boundary on social media. Internet etiquette is taught to everyone these days. So if your employee, no matter how valuable they are, crosses a line into propagating hate speech or is discriminating against a particular community of people, then I'd let them go. - Amine Rahal , IronMonk Solutions

6. Keeping Employees Because Of Seniority