Engineering: The Literature Review Process

- How to Use This Guide

What is a literature review and why is it important?

Further reading ....

- 2. Precision vs Retrieval

- 3. Equip Your Tool Box

- 4. What to look for

- 5. Where to Look for it

- 6. How to Look for it

- 7. Keeping Current

- 8. Reading Tips

- 9. Writing Tips

- 10. Checklist

A literature review not only summarizes the knowledge of a particular area or field of study, it also evaluates what has been done, what still needs to be done and why all of this is important to the subject.

- The Stand-Alone Literature Review A literature review may stand alone as an individual document in which the history of the topic is reported and then analyzed for trends, controversial issues, and what still needs to be studied. The review could just be a few pages for narrow topics or quite extensive with long bibliographies for in-depth reviews. In-depth review articles are valuable time-savers for professionals and researchers who need a quick introduction or analysis of a topic but they can be very time-consuming for authors to produce. Examples of review articles: Walker, Sara Louise (2011) Building mounted wind turbines and their suitability for the urban scale - a review of methods of estimating urban wind resource . Energy and Buildings 43(8):1852-1862. For this review, the author focused on the different methodologies used to estimate wind speed in urban settings. After introducing the theory, she explained the difficulty for in-situ measuring, and then followed up by describing each of the different estimation techniques that have been used instead. Strengths and weaknesses of each method are discussed and suggestions are given on where more study is needed. Length: 11 pages. References: 59. Calm, J.M. (2008) The next generation of refrigerants - historical review, considerations, and outlook. International Journal of Refrigeration 31(7):1123-1133. This review focuses on the evolution of refrigerants and divides the evolution into 4 generations. In each generation the author describes which type of refrigerants were most popular and discusses how political, environmental, and economic issues as well as chemical properties effected choices. Length: 11 pages. References: 51.

- The Literature Review as a Section Within a Document Literature reviews are also part of dissertations, theses, research reports and scholarly journal articles; these types of documents include the review in a section or chapter that discusses what has gone before, how the research being presented in this document fills a gap in the field's knowledge and why that is important. Examples of literature reviews within a journal article: Jobert, Arthur, et al. (2007) Local acceptance of wind energy: factors of success identified in French and German case studies. Energy Policy 35(5):2751-2760. In this case, the literature review is a separate, labeled section appearing between the introduction and methodology sections. Peel, Deborah and Lloyd, Michael Gregory (2007) Positive planning for wind-turbines in an urban context. Local Environment 12(4):343-354. In this case the literature review is incorporated into the article's introduction rather than have its own section. Which version you choose (separate section or within the introduction) depends on format requirements of the publisher (for journal articles), the ASU Graduate College and your academic unit (for ASU dissertations and theses) and application instructions for grants. If no format is specified choose the method in which you can best explain your research topic, what has come before and the importance of the knowledge you are adding to the field. Examples of literature reviews within a dissertation or thesis : Porter, Wayne Eliot (2011) Renewable Energy in Rural Southeastern Arizona: Decision Factors: A Comparison of the Consumer Profiles of Homeowners Who Purchased Renewable Energy Systems With Those Who Performed Other Home Upgrades or Remodeling Projects . Arizona State University, M.S. Thesis. This author effectively uses a separate chapter for the literature review for his detailed analysis. Magerman, Beth (2014) Short-Term Wind Power Forecasts using Doppler Lidar. Arizona State University, M.S. Thesis. The author puts the literature review within Chapter Two presenting it as part of the background information of her topic. Note that the literature review within a thesis or dissertation more closely resembles the scope and depth of a stand- alone literature review as opposed to the briefer reviews appearing within journal articles. Within a thesis or dissertation, the review not only presents the status of research in the specific area it also establishes the author's expertise and justifies his/her own research.

Online tutorials:

- Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students Created by the North Caroline State University Libraries

Other ASU Library Guides:

- Literature Reviews and Annotated Bibliographies More general information about the format and content of literature reviews; created by Ed Oetting, History and Political Science Librarian, Hayden Library.

Readings:

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting It Written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre, University of Toronto

- Literature Reviews Created by The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

- << Previous: How to Use This Guide

- Next: 2. Precision vs Retrieval >>

- Last updated: Jan 2, 2024 8:27 AM

- URL: https://libguides.asu.edu/engineeringlitreview

The ASU Library acknowledges the twenty-three Native Nations that have inhabited this land for centuries. Arizona State University's four campuses are located in the Salt River Valley on ancestral territories of Indigenous peoples, including the Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Pee Posh (Maricopa) Indian Communities, whose care and keeping of these lands allows us to be here today. ASU Library acknowledges the sovereignty of these nations and seeks to foster an environment of success and possibility for Native American students and patrons. We are advocates for the incorporation of Indigenous knowledge systems and research methodologies within contemporary library practice. ASU Library welcomes members of the Akimel O’odham and Pee Posh, and all Native nations to the Library.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Research Methods and Design

- Action Research

- Case Study Design

Literature Review

- Quantitative Research Methods

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Mixed Methods Study

- Indigenous Research and Ethics This link opens in a new window

- Identifying Empirical Research Articles This link opens in a new window

- Research Ethics and Quality

- Data Literacy

- Get Help with Writing Assignments

A literature review is a discussion of the literature (aka. the "research" or "scholarship") surrounding a certain topic. A good literature review doesn't simply summarize the existing material, but provides thoughtful synthesis and analysis. The purpose of a literature review is to orient your own work within an existing body of knowledge. A literature review may be written as a standalone piece or be included in a larger body of work.

You can read more about literature reviews, what they entail, and how to write one, using the resources below.

Am I the only one struggling to write a literature review?

Dr. Zina O'Leary explains the misconceptions and struggles students often have with writing a literature review. She also provides step-by-step guidance on writing a persuasive literature review.

An Introduction to Literature Reviews

Dr. Eric Jensen, Professor of Sociology at the University of Warwick, and Dr. Charles Laurie, Director of Research at Verisk Maplecroft, explain how to write a literature review, and why researchers need to do so. Literature reviews can be stand-alone research or part of a larger project. They communicate the state of academic knowledge on a given topic, specifically detailing what is still unknown.

This is the first video in a whole series about literature reviews. You can find the rest of the series in our SAGE database, Research Methods:

Videos covering research methods and statistics

Identify Themes and Gaps in Literature (with real examples) | Scribbr

Finding connections between sources is key to organizing the arguments and structure of a good literature review. In this video, you'll learn how to identify themes, debates, and gaps between sources, using examples from real papers.

4 Tips for Writing a Literature Review's Intro, Body, and Conclusion | Scribbr

While each review will be unique in its structure--based on both the existing body of both literature and the overall goals of your own paper, dissertation, or research--this video from Scribbr does a good job simplifying the goals of writing a literature review for those who are new to the process. In this video, you’ll learn what to include in each section, as well as 4 tips for the main body illustrated with an example.

- Literature Review This chapter in SAGE's Encyclopedia of Research Design describes the types of literature reviews and scientific standards for conducting literature reviews.

- UNC Writing Center: Literature Reviews This handout from the Writing Center at UNC will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

- Purdue OWL: Writing a Literature Review The overview of literature reviews comes from Purdue's Online Writing Lab. It explains the basic why, what, and how of writing a literature review.

Organizational Tools for Literature Reviews

One of the most daunting aspects of writing a literature review is organizing your research. There are a variety of strategies that you can use to help you in this task. We've highlighted just a few ways writers keep track of all that information! You can use a combination of these tools or come up with your own organizational process. The key is choosing something that works with your own learning style.

Citation Managers

Citation managers are great tools, in general, for organizing research, but can be especially helpful when writing a literature review. You can keep all of your research in one place, take notes, and organize your materials into different folders or categories. Read more about citations managers here:

- Manage Citations & Sources

Concept Mapping

Some writers use concept mapping (sometimes called flow or bubble charts or "mind maps") to help them visualize the ways in which the research they found connects.

There is no right or wrong way to make a concept map. There are a variety of online tools that can help you create a concept map or you can simply put pen to paper. To read more about concept mapping, take a look at the following help guides:

- Using Concept Maps From Williams College's guide, Literature Review: A Self-guided Tutorial

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix is is a chart you can use to help you organize your research into thematic categories. By organizing your research into a matrix, like the examples below, can help you visualize the ways in which your sources connect.

- Walden University Writing Center: Literature Review Matrix Find a variety of literature review matrix examples and templates from Walden University.

- Writing A Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix An example synthesis matrix created by NC State University Writing and Speaking Tutorial Service Tutors. If you would like a copy of this synthesis matrix in a different format, like a Word document, please ask a librarian. CC-BY-SA 3.0

- << Previous: Case Study Design

- Next: Quantitative Research Methods >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:51 AM

CityU Home - CityU Catalog

- Design Foundations

- Design Process

- Design Research

- Design Resources

- Field Tools

- Experience Design: Walt Disney World

Literature Review

A literature review explains concepts that relate to your research project. As a design researcher, your job is to select sources (news stories, books, journal articles, movies, etc.) that help you build a relevant research project. These sources help you determine what methods you should implement to get the data you need to answer your research question. The content in your literature review is a foundation for the rest of your project. It demonstrates you have searched the universe to learn as much as you can about your topic and that you have built your project on evidence.

Literature reviews don’t just report facts—they make a case for why the content you selected is essential for the research. Perhaps you feel that scenes from classic movies like Citizen Kane , The Maltese Falcon , and Holiday Inn reveal insights that inform your project. That’s great! Use the literature review to make a case for why they belong and what they reveal. You select the sources for the literature review, which means the content you feature is a stance that these concepts matter. Use the literature to justify your project.

In this piece, highlight conclusions that have been established and areas that have not been addressed. If contradictory content is found address it in the literature review. Review the theoretical framework for your project in the literature review and discuss how it connects to the research project. The literature review should contextualize why the research question(s) is/are being asked in the first place.

Often, a literature review follows this format:

- Introduction

- Conceptual or Theoretical Framework

- Review of Research (organized by themes)

What do you put in a Literature Review?

In their book A student’s guide to methodology: justifying enquiry , Clough and Nutbrown (2002) present the idea that the research question is the place to start when writing a literature review. They claim that the research question contains many of the parts of a literature review. Let’s see that in action.

Here’s a question developed in 2019 by xdMFA students Ashley Lippard and Vanessa Cannon.

What values motivate a female millennial when choosing between a disposable or reusable coffee cup while inside a coffee shop?

When we take this question apart, concepts for the literature review emerge—concepts we would need to research and write about. Let’s take a look at that breakdown:

- Values : What are they? Where do they come from? How do they affect behavior?

- Motivation : What is it? What are the different ways people are motivated? What prevents or encourages motivation? Historically, what has motivated this age group?

- Female Millennials : Who are they and what defines this culture? How do they behave? What decisions do they typically make? What are their values?

- Choice : What does choosing something over another thing entail? What affects choices in this scenario? What choices are available to these people? How empowered do they feel to choose for themselves?

- Disposable and reusable coffee cups : What are they and how did they come into being? What prompted businesses to offer these options? What are the physical features of these products? How and where are they made? How are they branded? What are the perceptions of these products?

- Coffee Shop : What are the different types of coffee shops? What do they mean to different people? What is acceptable behavior inside one? How do they function?

In just one research question, we isolated six different major concepts. If you wanted to, you could write at least five or six pages about each of these concepts. The literature review would be 30-40 pages long! More importantly, your literature review would be a thorough overview of key concepts for those who are not familiar with your topic.

Step-by-Step: an Applied Example

Many early-career students fall into the pit of writing an annotated bibliography or a book report and they think it’s a lit review. It’s not. Don’t do that.

The literature review does not summarize your sources—it tells your story in your words. You write about concepts relevant to the research, and the sources you found to support your statements. Yes, sometimes you may call out a specific source, quoting it directly, but almost all of your literature review should be in your words. Whenever you write a sentence that is from another’s work, cite it.

The lit review should look like an Easter egg hunt: a field of grass and trees and shrubs you planted and arranged, with a sprinkling of colorful citations within reach, ready to open.

Let’s use the example above to plan out a full literature review. The language I use below is very conversational just to point you in the right direction. It is not comprehensive or complete, but it should give you an idea of what you should write in the literature review. Do not submit a lit review that reads exactly like what I have written below.

Now that’s out of the way, here’s the research question again.

Lit Review Section 1: Introduction

Coffee shops are really popular in the United States and have seen a surge between 1990 and 2020 (citation). A lot of people go there. Popular shows, movies, show people hanging out in coffee shops a lot as if they are a cool place to be. Local and international-chain coffee shops permeate western culture and millennials go there a ton. It’s a place they hang out—not just for coffee, but as a Thirdspace (citation). Coffee shops are prevalent and are used daily by millions, which can lead to a great deal of paper and plastic waste in the form of disposable cups. When people buy coffee at a coffee shop, they have a choice to use a disposable cup provided by the store or to bring their own reusable cup. Both options have their own upsides and downsides—often driven by customers’ personal preferences and values but sometimes affected by how cool they want to look.

(this section should be at least 3 paragraphs)

Lit Review Section 2: Theoretical Framework

Millennials in the United States in 2020 are roughly 19 years-old. At this stage of development, they are forming their identities and are still very must about what looks cool, is stylish, and is trendy (citation). They want to be accepted and are forming their self and worldviews (citation). When these people buy coffee, they have a decision to make—to use a disposable or a reusable cup. Either choice demonstrates their values. The theory of attitudinal showing (TAS) explains how people’s outward choices demonstrate their values (This is not a real theory, y’all. I’m making this stuff up – Dennis) . TAS is comprised of several parts that are relevant for this project, which is concerned with values and coolness. I will discuss those parts here.

Lit Review Section 3: Review of Research (Organized by Themes)

This is what values are. They come from parents, friends, culture. People behave according to values. Millennials in the U.S. have these values. There has been a shift in values since industrialization. Etc. Write a lot about values based on your reading/the literature so readers know what they are and why they are part of this research project. Tell a rich story. Paint a clear picture. Cite all of your statements so readers will know where you got this information.

Motivation is (explain it here). People are motivated by different things—extrinsic and extrinsic. This is what intrinsic and extrinsic are. Millennials are really affected by extrinsic when it comes to buying. Their motivation to choose sustainable practices can suffer when they have limited friendships and deep relationships. Historically, millennials have been motivated by television, but it seems TikTok is the main driver now (citation). Etc. Write a lot about motivation based on your reading/the literature so readers know what it is and why it is part of this research project. Tell a rich story. Paint a clear picture. Cite all of your statements so readers will know where you got this information.

Choices are (explain it here). What does choosing something over another thing entail? What affects choices in this scenario? What choices are available to these people? How empowered do they feel to choose for themselves? Write a lot about choices based on your reading/the literature so readers know what they are and why they are part of this research project. Tell a rich story. Paint a clear picture. Cite all of your statements so readers will know where you got this information.

Female Millennials are (explain it here). Who are they and what defines this culture? How do they behave? What decisions do they typically make? What are their values? Write a lot about female millennials based on your reading/the literature so readers know who they are and why they are part of this research project. Tell a rich story. Paint a clear picture. Cite all of your statements so readers will know where you got this information.

Disposable and reusable coffee cups are (explain it here). What are they and how did they come into being? What prompted businesses to offer these options? What are the physical features of these products? How and where are they made? How are they branded? What are the perceptions of these products? Write a lot about coffee cups based on your reading/the literature so readers know who they are and why they are part of this research project. Tell a rich story. Paint a clear picture. Cite all of your statements so readers will know where you got this information.

Coffee Shops are (explain it here). What are the different types of coffee shops? What do they mean to different people? What is acceptable behavior inside one? How do they function? Write a lot about coffee shops based on your reading/the literature so readers know who they are and why they are part of this research project. Tell a rich story. Paint a clear picture. Cite all of your statements so readers will know where you got this information.

Lit Review Section 4: Conclusion

Wrap up your thoughts. Summarize the content. Connect the lit review to the next section in your Research Report (which is usually Methodology) so it flows seamlessly into the full report or dissertation.

Literature Review Guidance

In 2020, Nature posted “How to write a superb literature review,” where experts shared advice. It is a must-read.

These brief videos on literature reviews are a good introduction to the process.

Literature Review, Step By Step

Virginia Commonwealth University and UNC-Chapel Hill have great step-by-step processes for literature reviews published on their websites:

- Your First Literature Review: VCU Libraries

- Literature Reviews: UNC Chapel Hill

Where to Look for Literature

The literature review will catch you up on the aspects of your research topic. Use Google Scholar, the Miami University Libraries, websites, and blogs… anything that’s out there where people have written about your topic. Make sure to verify the sources you are reading are of high quality. If it’s a research paper that has been published, it’s probably ok. If it’s a blog post on a personal blog, use your common sense to verify what you’re reading is more fact than personal opinion.

More About Literature Reviews

These videos explore the literature review process in detail.

A reader should be able to remove all of the citations in the literature review and read it fluidly as if the topic is being explained in a seamless recount of what is known about the topic.

A Sample Literature Review

The best way to understand a good literature review is to read one. This Literature review, The Educational Benefits of Travel Experiences: A Literature Review , synthesizes existing knowledge elegantly, thoroughly, and clearly.

Literature Review: Developing a search strategy from the Charles Sturt University Library

Someday, a client or stakeholder will ask you “how do you know this design direction is going to work?” When you have reviewed the literature (what other people have found) you’ll be ready to answer with confidence. Enjoy finding out about your topic. The literature review should reveal new facets of it you had never before expected.

Go deep and be detailed. Do not assume your reader knows the concepts you are discussing.

Dennis Cheatham

Associate Professor, Communication Design

Miami University

Customize Cookie Preferences

Design studio practice in the context of architectural education: a narrative literature review

- Open access

- Published: 23 August 2021

- Volume 32 , pages 2343–2364, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Upeksha Hettithanthri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1337-4234 1 , 2 &

- Preben Hansen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5150-9101 1

11k Accesses

14 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize the current knowledge on the conventional design studio context. This is a narrative literature review based on articles published within the last ten years, while 60 articles were selected for the literature review following a rigorous filtration process. The final articles were selected by applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to the initially selected articles. This review has synthesized the current knowledge on design studio contexts and will review the conventional design studio context, design studio practices that take place within design studios and use of digital tools. The main aim of this study is to broaden the understanding of design studio contexts and to comprehend the types of design studio contexts available in architectural studies. Furthermore, it discusses the digital tools used in design studio practices in the last 10 years. A thematic analysis was conducted in reviewing the articles. It is to be noted that no research has been carried out except one on generating design studio context outside the conventional design studio set-up. This study aims to identify the potential research possibilities of context generated design studios to engage in design studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Communicating Heritage Through Intertwining Theory and Studio Based Course in Architectural Education

Educational Experiences Related to Architecture and Environmental Art

Exploring the architectural design process assisted in conventional design studio: a systematic literature review

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The meaning of the word context differs according to the situation (Koffeman & Snoek, 2019 ). As explicated by Edwards and Miller ( 2007 , p. 265), the meaning of the context in an educational set-up is a bounded container that allows various activities to occur. Further, the context has a fluid nature that could accommodate the flexibility to entertain a set of practices (Koffeman & Snoek, 2019 ). The design studio context is creating a learning environment that mainly focuses on increasing the creative learning abilities of the students (Ibrahim & Utaberta, 2012 ). The architectural design studio context is similar to other design studio contexts in graphics, fashion and communication disciplines, and it is almost similar in physical infrastructure and human involvement (Corazzoa, 2019 ). The sole difference lies in the specific tasks executed within the architectural design studio context. Students engage in solving architectural and spatial problems in architectural design studios. The physical infrastructure of the architectural design studio can even be used by other design disciplines because there is not much of a difference in the physical environment of the design studio. As illustrated by Emam et al. ( 2019 , p. 164), design studios mainly cater to design education where students engage in project-based learning. The design studio context consists of situational and contextual factors, in addition to the engagement of students and lecturers. Orbey and Sarioglu ( 2020 ) claimed that the activities that occur within the design studio context had empowered the creative design abilities of students. The physical environment of the design studio will never create a studio context without the collaborative engagement of the students and lecturers (Rodriguez et al., 2018 ). As depicted by Bashier ( 2014 , p. 426), the context of the design studio can be identified as a collaborative learning environment where students and lecturers are engaged in learning and teaching through real-life problem scenarios. According to Grover et al. ( 2020 , p. 2), the design studio context motivates the intrinsic creativity of students through the learning environment.

Conventional design studio (CDS)

The conventional design studio context is a learning environment located within an institutional set-up with all the infrastructure created to collaborate, brainstorm, learn by doing, and engage in reflective practice (Orbey & Sarıoğlu Erdoğdu, 2020 ). CDS context is a creative learning space where students gather with peers and tutors to solve design problems. Further, CDS is identified as a physical container created for the social interaction of students and design tutors (Corazzoa, 2019 ). The physical boundaries of the conventional design studio are limited to an academic or an institutional environment (Kay Brocato, 2009 ). However, pedagogical practices have heavily contributed to making the design studio conventional. Existing studies on CDS articulate it as an engagement or an approach for teaching occurring within a specific environment. Schon ( 1987 , pp. 41–43) defines the design studio through four central learning concepts. He explained the design studio as (1) a culture where students and lecturers work together, (2) as a physical fixed space where teaching and learning can occur, (3) studio as a way of teaching and learning, and (4) as a program of activity. The learning culture of the design studio is students and lecturers working together, sharing ideas, testing best solutions, displaying the results, and this creates an interactive knowledge sharing, practice-based learning culture where students learn through reflection in action. This pedagogical practice is a unique learning culture. However, this reflective practice and collaborative learning culture is not limited only to CDS. This practice can even be seen in non-conventional, virtual, blended or online design studios. Echoing this fact, Schon ( 1987 , p. 44) highlights “the studio as a physical fixed space where teaching and learning can be happening”. In strengthening the definition given by Schon, Corazzoa ( 2019 , p. 1255) has defined the design studio context through six elements. They are (1) studio as making, (2) studio as bridging, (3) studio as meaning, (4) studio as enabling, (5) studio as backgrounding and (6) studio as disciplining. The Design studio context enables students to work with materials and make artefacts. This fact further strengthens the point of learning by doing. Creating artefacts can happen in a CDS setting or even in a virtual/blended platform where students could collaborate online. In non-conventional virtual design studios, making happens through a digital medium by incorporating digital tools and technologies such as Auto Cad, 3D max, etc. These six elements are not only seen in non-conventional virtual/blended and online design studios; they are also visible in CDS. This Literature Review focuses on identifying the types of design studio contexts, including studio practices.

In defining the Conventional Design Studio, it is stated that as a comprehensive model of design learning established many decades before, its system, built structure, and epistemology intermingle together to create a unique learning environment following problem-based learning (Brandt et al., 2013 ). Design studio context provides room for both implicit and explicit learning (Park, 2020 ). We identified the conventional design studio as a structured, systematic learning and designing process by being in a dedicated fixed built structure. However, students in the conventional design studio face many problems, making the process adopted in the CDS more problematic (Chen, 2016 ). In the context of CDS, the design process that is followed is more linear; the instructors set the design process into small tasks and request students to work according to those instructions (Chen, 2016 ). Students in the CDS are guided by expert designers in the industry (Rodriguez et al., 2018 ). The conventional design studio has reported that students have less motivation and engagement, and there are many reasons behind it (Rodriguez et al., 2018 ). The structured, systematic process of the CDS provides a less diversified learning experience to the students, impacting their creativity and design thinking in various ways (Rodriguez et al., 2018 ). Moreover, the CDS context has reported the disconnection from real-world problem scenarios, highlighting that finding solutions for problems set in the outside world while sitting in a dedicated working environment might be the key reason for this disconnection (Rodriguez et al., 2018 ).

It is essential to understand what distinguishes the conventional design studio context from other contexts. CDS is a creative learning environment where students are assigned to solve real-life problems through creative design solutions while being in a dedicated room for designing in an institutional set-up. Furthermore, CDS is a controlled creative learning environment that has been specifically designed to engage in creative activities. However, the unique feature of the CDS is that it is accompanied by all the tools that are especially required for design. This fact distinguishes the CDS unique form from other contexts. When creating a design studio context outside of an institutional set-up, facilitating those design tools is challenging because those were designed to work within a CDS context.

Design studio practices

The studio practices are the activities students and facilitators are engaged in. The design studio context facilitates numerous activities. Students are learning by creative pursuits. They work together with their peer to find design solutions to real-life problems. Face-to-face learning, peer support, assessments, and reflective practice are commonly discussed studio practices in literature. As explained by Emam et al., ( 2019 , pp. 164–165), within the conventional design studio context, students engage in a single open-ended, project-based problem, allowing students to solve the problem in their own way. The design solutions are generated through an iterative process, and the design solutions are continuously reviewed, judged and open for comments by the jury and the peer (Ardington & Drury, 2017 ). Another practice that is generated through students' engagements with projects is Interaction and engagement. The design studio context fosters motivation and helps to develop strong learning communities. This enhances deep learning and sustainable retention of the learning outcomes of design studies. Thus, this literature review highlights the existing evidence on commonly used studio practices.

Use of tools

Usage of tools plays a vital role in the design studio context. Students use tools for various tasks. They need the aid of tools from the beginning of the design process to the end. Some tools are supportive in creative designing, and some tools are supportive in creative design communication, whilst another set of tools are supportive in teaching and learning in design studios. Tools used in design studios are found in both digital and manual formats. Therefore, identifying the types of tools used in design studios is one of the aims of this literature review.

This review aims to understand the design studio contexts found in literature and identify the key characteristics of the studio context. Furthermore, this review explores the type of studio practices found within the design studio context. This review will give a broad understanding of the design studio context and existing studio practices. This study has adopted the narrative literature review methodology, and articles published over the last decade (2010–2020) were selected. The reason for the selection is that the writer needed to explore how teaching and learning have taken place in the recent past and how it has changed from its original form. The literature has revealed a cross-section of how the CDS and its practices have been explored and investigated by other researchers throughout the last decade.

To summarize, the CDS has shown problems in the areas of (1) student engagement, (2) motivation, (3) disconnection from real-world problem scenarios. These issues demand a move from the CDS context. Moreover, there is a substantial gap in literature on context generated design studios that could create the design studio outside the conventional framework.

Problem formulation

The context of education has changed rapidly from face-to-face learning to online distance learning. In addition, the use of digital tools for teaching and learning has escalated drastically. How these changes have reflected on architectural studio context is a subject that lacks discussion and, therefore, an important aspect that warrants further research.

The conventional design studio context has not undergone many changes from its original form. The contextual influences on students' design process are important; however, it has lacked in-depth research over the last few decades. The aim of this literature review is to understand how those researchers have been identified within the design studio context in the respective empirical studies and to assess the contextual contribution towards design studio practices. For this purpose, empirical studies on the design studio context and design studio practices were selected after a rigorous filtration process.

Research has indicated that the learning needs of contemporary architectural learners have evolved to a complex level. Therefore, it becomes imperative to explore the potential practices that could be adopted by using digital technologies to benefit future architectural learners. The studio has been recognized as the unique learning context for architectural studies. However, stepping out from the typical pedagogic framework while keeping unique elementary needs of the conventional design studio context is an important fact that many researchers have not explored. The problem has been formulated to understand the contextual contribution of the design studio to the design studio practices and to understand how the digital technologies could be used in teaching and learning in design studios.

Research questions

This literature review was conducted to find answers for the following research questions:

RQ 1—What are the architectural design studio contexts available?

RQ 2—What are the architectural design studio practices available?

RQ 3—What are the digital tools and technologies used in architectural design studios?

Methodology

For this literature review, the narrative review methodology was adopted (SAGE Internet Research Methods, 2019 ). Narrative literature reviews consist of a credible, comprehensive, in-depth analysis of a particular subject domain, allowing the writer to critically analyze and summarize theories and concepts (Baker, 2016 ) (Green et al., 2006 ). Adopting a narrative literature review methodology will be supportive in identifying patterns and trends in the literature and identify existing gaps in the body of the knowledge domain (Green et al., 2006 ). The study needed to generate more focus on the research questions and discover and produce comprehensive, methodological, and logical answers based on the publications selected. A narrative literature review provides a theoretical focus on the existing knowledge domains and logical explanations of available knowledge sources. Even though we have adopted the narrative literature review methodology, a rigorous systematic method of searching and selection of articles adopted is further explained in “ Search strategy ” section.

The study adopted literature within the last ten years because finding the most current studio practices and design processes within the design studio context is important in framing the research. The primary selection criteria for the articles focused on identifying papers containing data and empirical studies on the architectural design studio context, which explains the design process of the students. Furthermore, the necessary keywords for advanced study were established based on the above focus.

Search strategy

For this study, articles were browsed from the following databases: Scopus, Web of Science, and Science Direct. The reason behind selecting these three databases is that they are widely used for literature reviews on architectural studies by many scholars, and they contain a heavy number of articles related to architectural studies. At the initial search, 1594 peer-reviewed articles were found. For this search, articles published from 2010–2020 were selected as the time duration. This specific choice of publication years was to meet the study's requirement of exploring recent knowledge domains and contemporary practices related to design studios.

Articles were browsed using several keywords, and those keywords were generated by using similar meanings and applications of the design studio. The appearance of those keywords in all sections, including the title, abstract, and full text, were taken into account. “Architectural Design Studio” OR “Design Studio Education” OR “Design studio context” OR “Context of Design studio” OR “Design Studio environment” OR “Design studios” OR “Learning in Architectural Design Studios” OR “Interior Design Studios” AND “Online Design Studios” OR “Mobile Design Studios” OR “Remote Design Studios” OR “Distance Learning in Architectural Studio” were used as keywords in browsing. Articles were selected irrespective of region or country. Journal and conference articles have both been taken into account for the review.

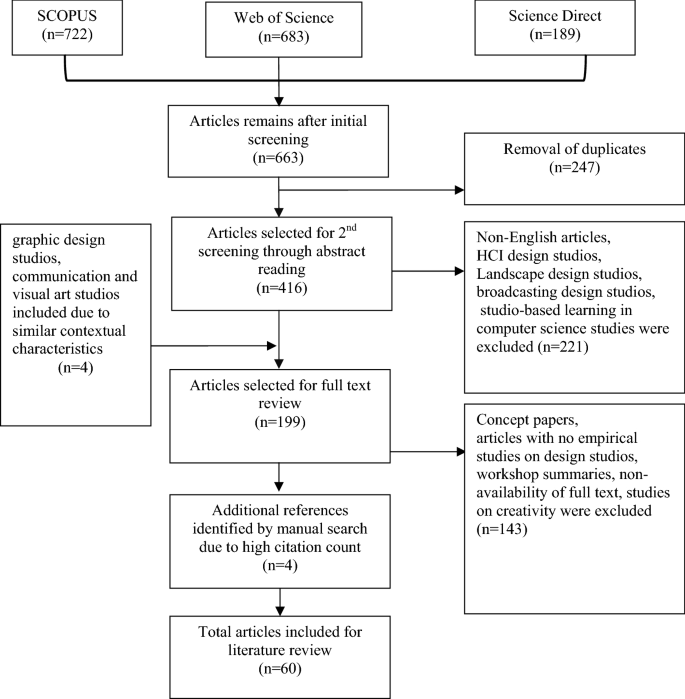

Inclusion and exclusion

The initial screening included reading the abstracts of the selected article and thereafter selected 663 relevant articles for further examination. Duplicates were removed, after which 416 articles remained. Design studio experiments conducted in order for IT students to discover HCI matters were removed at the second filtration due to the lack of explanations on design studio context. Broadcasting design studios and studio-based learning in computer science and linguistic studies were also excluded. Since the design studio context is almost equivalent to the architectural design studio, literature on graphic design studios and product design studios were included in this study. Landscape design studios that have conducted empirical research on fieldwork with no involvement of digital technology or digital tools were excluded at the second filtration. Empirical studies on design studio practices, empirical studies on conventional design studios, studio space and context, empirical studies on the use of digital and manual tools in design studio education, virtual design studios, blended learning design studios and teaching experiments in design studios were included for the full article review. In addition, literature reviews conducted on architectural design studios were included for the review because those contained summaries of the knowledge gained through referring to many research studies found on architectural design studio contexts. This literature review aims to understand how the CDS context and its practices have been explained in the existing literature. Concept papers found did not encompass sufficient information in explaining the design studio context, the role of the studio and studio practices. Therefore, those papers were excluded. Empirical studies on creative design studio practices were included; however, studies on creativity and creative cognition were excluded because creativity is a different domain and exploring creativity is not a central aim of this study. Articles that lacked explanation on design studio practices, workshop summaries, and articles with limited access to the full text were excluded at the third filtration. Moreover, for the review, quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method, and ethnographic studies were selected (Fig. 1 ).

Process map of article selection

Eligibility criteria for inclusion

After the rigorous filtration process, 60 peer-reviewed articles written in the English Language were selected for the literature review. The following eligibility criteria were established to find the current status of literature in the architectural design studio context. Criteria were established in answering the research questions generated. In answering RQ1, Criteria 1 and 2 were created. This will support filtering the best-fit articles to describe the design studio context and broaden the understanding of the design studio context as a learning environment. Criteria 3,4 and 5 was created in answering RQ2. RQ 2 focuses on determining the current studio practices found in literature. In investigating this matter, the studio practice has been divided into two major streams: pedagogical practices and creative design practices and studies conducted under those areas were mapped accordingly under the categories created. RQ 3 focuses on understanding the types of digital tools and technologies used in design studios, and criteria 6 and 7 address this matter.

List of criteria

Empirical studies describing conventional design studio context

Empirical studies on distance, virtual and blended design studio contexts.

Empirical studies on creating design studio context outside the conventional institutional set-up

Empirical studies on pedagogical practices in design studios

Empirical studies on creative design practices in design studios

Empirical studies on digital pedagogical tools used in design studio practice

Empirical studies on creative digital design tools used in design studios

The table of criteria generated the following outcomes. Among 27 articles, 60 described the conventional design studio context through their empirical studies. Amid those 27 articles, 7 articles described the conventional design studio context in addition to virtual/blended /online design studios. There was only one article amidst them, which had stepped beyond the conventional studio set-up and facilitated the students' design process in a non-institutional environment, and it was a fieldwork project. 34 articles were discussed pedagogical practices within the design studio context. Perusing the articles, it was evident that the research interest in pedagogical practices within design studios has escalated within the last ten years. 21 studies generated discussions on creative design practices. Furthermore, 21 articles with discussions on digital pedagogical tools used in design studios were found, and 13 articles discussed creative digital design tools. As shown in Table 1 , we found a substantial gap in studies focusing on context generated design studios.

The study adopted the Thematic analysis based on the Grounded Theory under the qualitative methodology in analyzing data. Grounded theory is a mechanism that is applied in order to build a theory from available data (Corbin & Strauss, 2020 ). In the application of Grounded Theory, it is unnecessary to start with a pre articulated hypothesis or a theory, but it allows the researcher to build a theory based on the data generated through empirical study (Byrne, 2016 ). Thematic analysis is a methodology that could show existing patterns in data. Thematic Analysis comes under the umbrella of qualitative research methodology, which could develop themes through the data gathered. The thematic analysis reveals a pattern within the recognized data that has emerged through analysis categories (Jennifer Fereday & Eimear Muir-Cochrane, 2006 ). This was guided by 6 phases of thematic analysis, and an inductive approach has been undertaken (Hoskyns, 2016 ). Utilizing an inductive approach in qualitative data analysis is a method that involves reading raw data and generating categories and themes based on the researcher's criteria instead of adhering to existing theories. The inductive approach is a bottom-up method where the researcher uses observations to see the patterns. Moreover, the inductive approach allows the researcher to develop a theory that emerges from the data (Yukhymenko et al., 2014 ).

Familiarizing with the data, creating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining the themes, and reporting were the significant six steps to generate themes. As the initial step of the thematic analysis, important data identified through rigorous filtration were extracted from the articles. The data was fed into a codebook in an Excel sheet. The study followed a three-phased coding methodology commencing with open coding. The coding was conducted to seek the answers to the research questions generated. Firstly, the narrations were coded into multiple open codes. Open codes consist of narrations on the design studio context, virtual studios, studio practices, experiments, examples, explanations on tools, technology and multiple related facts. In order to filter the data generated from open coding, it was further clustered into meaningful axial codes by collecting similar subject areas into axial coding. A set of axial codes generated selective codes, which supports generating categories. Those categories generated themes that could answer the research questions created. The coding process was done through MAXQDA 11, and the affinity diagram was used at the beginning of the process before it was fed into the software.

Thematic analysis—design studio contexts

RQ 1 is created to identify the types of design studio contexts found in literature. In this process, we identified codes in literature describing the design studio context and its characteristics. The identified codes were clustered into 22 major categories. Six themes emerged through the categories identified, and three of them described the conventional design studio context, and the rest described the non-conventional design studio context (Table 2 ).

The design studio contexts depicted in the literature has generated two major dimensions as conventional design studio context and non-conventional design studio context. Identified codes generated 11 major categories, and it led to identifying three major themes as material space, pedagogical practices and creative design practices, which created the dimension: conventional design studio context. On the other hand, virtual space, pedagogical practices, and creative design practices generated the dimension non-conventional design studio context. The codes and categories have shown that the CDS context has many common features that are even visible in non-conventional design studio contexts. The studio context comprises physical infrastructure such as pinup boards, tables and chairs, which support design and drawing purposes, display panels for demonstrations, and model making areas for prototyping and testing.

The material space of the design studio is the built environment and the working culture of a studio. In defining the material space of the CDS, Corazzoa ( 2019 , p. 1255) has explained it through five elements. The material space of a studio empowers Making, Bridging, Meaning, Enabling, Backgrounding and Disciplining. Further, explaining this fact, the CDS context comprises a space for making and creating artifacts or models for testing design ideations. The built environment and physical infrastructure contribute heavily to this fact. The activities taking place in the CDS confer meanings and values such as periodic critics, demonstrations and conversations and dialogues on projects contributing to meaningful outcomes.

Further, the material space of a CDS enables students and tutors to collaborate more through interactive activities that support sharing knowledge and experience. The material space of CDS provides the background for all learning and teaching activities and acts as a backdrop for all the activities. Finally, the material space of CDS contributes to carving the design discipline, in addition to creating a culture of designing.

The existence of martial space will not convert the space into a design studio context. To make it a studio context, the contribution of pedagogical and creative design practices has played a vital role. The codes have shown that the conventional context of the design studio is not only made by the fixed, immobile physical infrastructure of the design studio. Even within the modern, non-traditional set-up, the CDS context has found teaching and learning practices followed by the conventional master apprenticeship model. The fixed physical nature of the design studio is not the only demarcation that makes it conventional. In order to deem it a conventional design studio, the pedagogical practices followed would contribute.

The theme generated as "creative design practices" comprises heavy paperwork, pen and pencil work, and verbal communication. Students in CDSs produce heavy paper prototypes and rough mock-ups (Vosinakis & Koutsabasis, 2013 ). In CDS, students are encouraged to build solid skills through manual drafting, rendering and making. The dependency and encouragement to utilize manual techniques and tools are higher in CDS contexts. The mixed-use of digital and manual tools is commonly evident as a pedagogical practice in CDS. The mode of engagement is face to face in the CDS context. The face-to-face interaction enables students to see and reflect on the other peer learners' design approaches and witness pitfalls in their design solutions. Problem-based learning is heavily practiced in CDS. Students learning in CDS contexts bring the problem to the design studio to solve. This has created a disconnection from real-world problem scenarios. Stepping out from the conventional context to where the problem is generated and solving it by being in the real problem context was not evident in CDS. In this scenario, live projects can be identified as a pedagogical practice found in non-conventional design studio contexts where students work and design in real problem courses by being in those contexts.

In answering RQ1, the thematic analysis brought up two major design studio contexts found in empirical studies, namely conventional design studio and non-conventional design studio contexts. The study noted that pedagogical and creative design practices contribute heavily to making the set-up conventional or non-conventional. This literature review identified CDS as a fixed, immobile, physical environment located within an institutional set-up for design students and lecturers to engage in their design practices. Moreover, the study highlights that the CDS context has been created by adopting conventional pedagogical practices into the studio without moderating them to fit into the studio user's current knowledge and skill levels. The facts found in literature strengthened the notion that the studio practices could step beyond the conventional studio environment to the context generated design studios where students could create their design studio through engagement.

- Studio practices

RQ 2 was focused on identifying studio practices followed in studio contexts. The pedagogical approaches followed in the conventional design studio is mainly followed by traditional teaching and learning methods. Students are learning through the reflection of the design tutors, and this has been explained by Schon ( 1987 ), 30 years prior to his theory on the reflective practitioner. "Reflection on action" is the established pedagogical practice in the conventional design studio. The non-conventional design studio context displays more freedom when guiding novice designers. The categories have shown that the NCDSs are rich in digital technologies. It uses digital tools, software and platforms in various levels of teaching and learning. Design communication and collaboration is done chiefly through digital platforms. Blogs, Web 2.0, and social media platforms became popular among non-CDS users (Bâldea et al., 2015 ). The use of digital technologies for communication is not commonly available in the CDS context. Students and design tutors gather face to face at design studios and discuss, demonstrate, present and criticize design attempts. Therefore, technology does not play a significant role in communication in the conventional design studio context.

The CDS context is featured as a safe and ideal place for problem-based learning in literature. Furthermore, it generates the feeling of a laboratory where many experiments and testing with the involvement of many parties in an open, less formal and less hierarchical workplace environment (Ardington & Drury, 2017 ). Furthermore, the conventional design studio context comprises high material character with sketches, notes, artifacts, paper mock-ups, physical models and pinup presentation facilities (Vyas, 2013 ). The flexible infrastructure of the studio environment supports adaptability to various scenarios (Corazzoa, 2019 ). Compared to the virtual/ online design studio context, the material character has been replaced through digital tools such as digital drawing platforms, virtual realities etc. The change of the material space or physical infrastructure has not sufficiently influenced the creative design practice of students because it stands as a facilitator in the conventional design studio context.

It was challenging to identify clear margins on differentiating design studio practices of CDS and NCDS. The boundaries got blurred due to the most common features visible in both contexts. It was evident in literature; NCDSs practice the same pedagogical practices; however, they use different platforms. The collaboration is mostly happening through the digitally mediated platforms in NCDS contexts. In this scenario, virtual, blended, and online design studios were counted as NCDSs, where students collaborate mainly through digitally mediated virtual environments. Literature depicts that students in NCDS contexts generate more virtual and digital prototypes than students in CDS contexts. Making digital prototypes is again visible in the CDS context. Nevertheless, in virtual and online studio contexts, students mainly get the help of software and virtual realities in developing, prototyping and testing design solutions. The availability of the material space is not a mandatory factor in NCDS contexts.

Codes and categories have emphasized that CDS is more focused on bringing design problems into the design studio and engaging in solving those within the physical boundaries of the CDS. The pedagogical practices are more centered on generating solutions for real-life problems while engaging in studio activities. This practice has created a unique working culture within the CDS. Students empathize, synthesize and generate ultimate solutions to problems generated in the world outside the design studio set-up while being in the CDS environment. This scenario has even been reflected in virtual and online design studios. In the virtual, blended or online design studio, students are more distant to the actual problem domain, and the level of collaboration and levels of empathizing and synthesizing have varied from the CDS. Being in the context where a problem has occurred or working in the context where more inspiration could be found rather than bringing them back to the studio can be identified as non-conventional studio practices, and the generated codes and categories supported this fact. Process-based learning than project-based learning is visible in non-conventional studio practices.

We believe those pedagogical practices and creative design practices heavily contribute to converting the material space of the CDS into a studio context. The material space of the design studio has no meaning without creative and pedagogical practices embedded within it. From our point of view, any context could be converted into a design studio by adopting pedagogical and creative design practices and the involvement of active collaboration of students and lecturers. The flexibility of the design studio environment is a motivational factor in moving out from the conventional design studio to context generated design studios. We strongly believe that any context could be transferred into a context generated design studio by facilitating the creative and pedagogical practices within any environment.

Digital tools

RQ 3 aims at identifying digital tools used in design studio contexts identified in RQ1. In answering this question, the study generated seven major categories via 21major codes identified. Those categories led to three themes that fall under three dimensions. Literature shows evidence on the escalation in digital tools in design studio practice from 2012–2020 (Table 3 ).

The coding was done based on the understanding of what those tools support. Twenty-six codes were generated, and they were clustered into seven major categories. It was tested and depicted in literature; some digital tools have contributed to improving the students' creative design thinking ability. Most digital tools such as the internet, virtual reality, video cameras and some 3D abstractions and construction of digital 3Ds have been supported in improving creative design abilities (Lloyd, 2013 ). Virtual realities have created a platform for students to see beyond what they can predict and assume to see. Further, these digital tools have more flexibility to conduct many revisions, which indirectly supports the improvement of creative thinking. Using the internet for searching, identifying the precedents, analyzing and extracting relevant knowledge to solve the problem at hand also makes the designer creative in identifying potential applications. This identification generates the first dimension, “Digital tools supported for creative design thinking”.