Intellectual Property Implications of Artificial Intelligence and Ownership of AI-Generated Works

133 Pages Posted: 10 Jul 2023

Ashraf Tarek

Independent

Date Written: June 28, 2023

This dissertation explores the complex and evolving relationship between artificial intelligence (AI) and intellectual property (IP) law, specifically focusing on the ownership of the products created through AI. With the rapid advancements in AI technology, machines are increasingly capable of autonomously generating creative works, raising novel legal challenges. This study examines the existing legal frameworks, evaluates the adequacy of current IP laws, and proposes potential solutions to address the intellectual property implications of AI-generated works.

Keywords: Intellectual Property, Artificial Intelligence, Ownership of AI-Generated Works

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Ashraf Tarek (Contact Author)

Independent ( email ), do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on ssrn, paper statistics, related ejournals, intellectual property: copyright law ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Intellectual Property: Patent Law eJournal

Intellectual property: trademark law ejournal, artificial intelligence ejournal, artificial intelligence - law, policy, & ethics ejournal, information policy, ethics, access & use ejournal.

Advertisement

Artificial intelligence as law

Presidential address to the seventeenth international conference on artificial intelligence and law

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2020

- Volume 28 , pages 181–206, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Bart Verheij 1

17k Accesses

28 Citations

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Information technology is so ubiquitous and AI’s progress so inspiring that also legal professionals experience its benefits and have high expectations. At the same time, the powers of AI have been rising so strongly that it is no longer obvious that AI applications (whether in the law or elsewhere) help promoting a good society; in fact they are sometimes harmful. Hence many argue that safeguards are needed for AI to be trustworthy, social, responsible, humane, ethical. In short: AI should be good for us. But how to establish proper safeguards for AI? One strong answer readily available is: consider the problems and solutions studied in AI & Law. AI & Law has worked on the design of social, explainable, responsible AI aligned with human values for decades already, AI & Law addresses the hardest problems across the breadth of AI (in reasoning, knowledge, learning and language), and AI & Law inspires new solutions (argumentation, schemes and norms, rules and cases, interpretation). It is argued that the study of AI as Law supports the development of an AI that is good for us, making AI & Law more relevant than ever.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Study of Artificial Intelligence as Law

Toward a Conceptual Framework for Understanding AI Action and Legal Reaction

I, Inhuman Lawyer: Developing Artificial Intelligence in the Legal Profession

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Medical Ethics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is my pleasure to speak to you today Footnote 1 on Artificial Intelligence and Law, a topic that I have already loved for so long—and I guess many of you too—and that today is in the center of attention.

It is not a new thing that technological innovation in the law has attracted a lot of attention. For instance, think of an innovation brought to us by the French 18th century freemason Joseph-Ignace Guillotin: the guillotine. Many people gathered at the Nieuwmarkt, Amsterdam, when it was first used in the Netherlands in 1812 (Fig. 1 , left). The guillotine was thought of as a humane technology, since the machine guaranteed an instant and painless death.

Technological innovation in the law in the past (left) and in the future? (right). Left: Guillotine at the Nieuwmarkt in Amsterdam, 1812 (Rijksmuseum RP-P-OB-87.033, anonymous). Right: TV series Futurama, judge 723 ( futurama.fandom.com/wiki/Judge_723 )

And then a contemporary technological innovation that attracts a lot of attention: the self-driving car that can follow basic traffic rules by itself, so in that sense is an example of normware, an artificial system with embedded norms. In a recent news article, Footnote 2 the story is reported that a drunk driver in Meppel in my province Drenthe in the Netherlands was driving his self-driving car. Well, he was riding his car, as the police discovered that he was tailing a truck, while sleeping behind the wheel, his car in autopilot mode. His driver’s licence has been withdrawn.

And indeed technological innovation in AI is spectacular, think only of the automatically translated headline ‘Drunken Meppeler sleeps on the highway’, perhaps not perfect, but enough for understanding what is meant. Innovation in AI is going so fast that many people have become very enthusiastic about what is possible. For instance, a recent news item reports that Estonia is planning to use AI for automatic decision making in the law. Footnote 3 It brings back the old fears for robot judges (Fig. 1 , right).

Contrast here how legal data enters the legal system in France where it is since recently no longer allowed to use data to evaluate or predict the behavior of individual judges:

LOI n \(^{\mathbf{o}}\) 2019-222 du 23 mars 2019 de programmation 2018–2022 et de réforme pour la justice (1)—Article 33 Les données d’identité des magistrats et des membres du greffe ne peuvent faire l’objet d’une réutilisation ayant pour objet ou pour effet d’évaluer, d’analyser, de comparer ou de prédire leurs pratiques professionnelles réelles ou supposées. [The identity data of magistrates and members of the registry cannot be reused with the purpose or effect of evaluating, analyzing, comparing or predicting their actual or alleged professional practices.]

The fears are real, as the fake news and privacy disasters that are happening show. Even the big tech companies are considering significant changes, such as a data diet. Footnote 4 But no one knows whether that is because of a concern for the people’s privacy or out of fear for more regulation hurting their market dominance. Anyway, in China privacy is thought of very differently. Figure 2 shows an automatically identified car of which it is automatically decided that it is breaching traffic law—see the red box around it. And indeed with both a car and pedestrians on the zebra crossing something is going wrong. Just this weekend the newspaper reported about how the Chinese public thinks of their social scoring system. Footnote 5 It seems that the Chinese emphasise the advantages of the scoring system, as a tool against crimes and misbehavior.

A car breaching traffic law, automatically identified

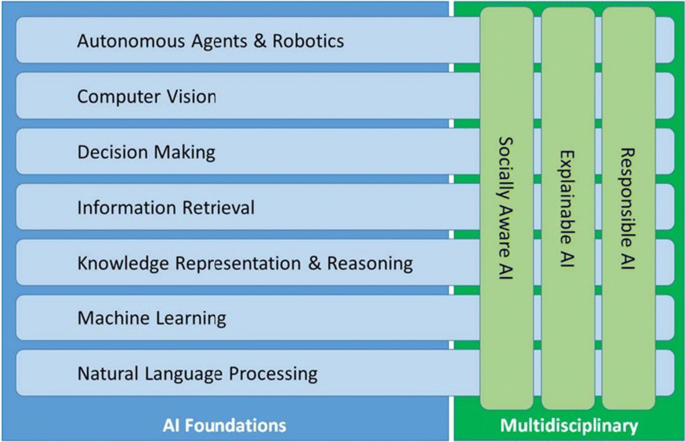

Against this background of the benefits and risks of contemporary AI, the AI community in the Netherlands has presented a manifesto Footnote 6 emphasising what is needed: an AI that is aligned with human values and society. In Fig. 3 , key fields of research in AI are listed in rows, and in columns three key challenges are shown: first, AI should be social, and should allow for sensible interaction with humans; second, AI should be explainable, such that black box algorithms trained on data are made transparent by providing justifying explanations; and, third, AI should be responsible, in particular AI should be guided by the rules, norms, laws of society.

Artificial Intelligence Grid: foundational areas and multidisciplinary challenges (source: Dutch AI Manifesto \(^{6}\) )

Also elsewhere there is more and more awareness of the need for a good, humane AI. For instance, the CLAIRE Confederation of Laboratories for AI Research in Europe Footnote 7 uses the slogan

Excellence across all of AI For all of Europe With a Human-Centered Focus.

In other words, this emerging network advertises a strong European AI with social, explainable, responsible AI at its core.

And now a key point for today: AI & Law has been doing this all along. At least since the start of its primary institutions—the biennial conference ICAIL (started in 1987 by IAAIL), Footnote 8 the annual conference JURIX (started in 1988) Footnote 9 and the journal Artificial Intelligence & Law (in 1992)—, we have been working on good AI. In other words, AI & Law has worked on the design of socially aware, explainable, responsible AI for decades already. One can say that what is needed in AI today is to do AI as we do law.

2 Legal technology today

But before explaining how that could go let us look a bit at the current state of legal technology, for things are very different when compared to the start of the field of AI & Law.

For one thing, all branches of government now use legal technology to make information accessible for the public and to provide services as directly and easily as possible. For instance, a Dutch government website Footnote 10 provides access to laws, regulations and treaties valid in the Netherlands. The Dutch public prosecution provides an online knowledge-based system that gives access to fines and punishments in all kinds of offenses. Footnote 11 There you can for instance find out what happens when the police catch you with an amount of marihuana between 5 and 30 grams. In the Netherlands, you have to pay 75 euros, and there is a note: also the drugs will be taken away from you. Indeed in the Netherlands all branches of government have online presence, as there is a website that gives access to information about the Dutch judicial system, including access to many decisions. Footnote 12

An especially good example of successful legal technology is provided by the government’s income tax services. Footnote 13 In the Netherlands, filling out your annual tax form has become very simple. The software is good, it is easy to use, and best of all: in these days of big interconnected data much of what you need to fill in is already fillled in for you. Your salary, bank accounts, savings, mortgage interest paid, the value of your house, it is all already there when you log in. In certain cases the tool even leaves room for some mild tax evasion—or tax optimisation if you like—since by playing with some settings a married couple can make sure that one partner has to pay just below the minimal amount that will in fact be collected, which can save about 40 euros.

One might think that such legal tech systems are now normal, but that is far from true. Many countries struggle with developing proper legal tech at the government level. One issue is that the design of complex systems is notoriously hard, and this is already true without very advanced AI.

Also the Netherlands has had its striking failures. A scary example is the Dutch project to streamline the IT support of population registers. One would say a doable project, just databases with names, birth dates, marriages, addresses and the like. The project was a complete failure. Footnote 14 After burning 90 million euros, the responsible minister—by the way earlier in his career a well-recognized scientist—had to pull the plug. Today all local governments are still using their own systems.

Still legal tech is booming, and focuses on many different styles of work. The classification used by the tech index maintained by the CodeX center for legal informatics at Stanford university distinguishes nine categories (Marketplace, Document Automation, Practice Management, Legal Research, Legal Education, Online Dispute Resolution, E-Discovery, Analytics and Compliance). Footnote 15 It currently lists more than a 1000 legal tech oriented companies.

And on the internet I found a promising graph about how the market for legal technology will develop. Now it is worth already a couple of 100s of millions of dollars, but in a few years time that will have risen to 1.2 billion dollars—according to that particular prediction. I leave it to you to assess what such a prediction really means, but we can be curious and hopeful while following how the market will actually develop.

So legal tech clearly exists, in fact is widespread. But is it AI, in the sense of AI as discussed at academic conferences? Most of it not really. Most of what we see that is successful in legal tech is not really AI. But there are examples.

I don’t know about you, but I consider the tax system just discussed to be a proper AI system. It has expert knowledge of tax law and it applies that legal expertise to your specific situation. True, this is largely good old-fashioned AI already scientifically understood in the 1970s, but by its access to relevant databases of the interconnected-big-data kind, it certainly has a modern twist. One could even say that the system is grounded in real world data, and is hence an example of situated AI, in the way that the term was used in the 1990s (and perhaps before). But also this is clearly not an adaptive machine learning AI system, as is today expected of AI.

3 AI & law is hard

The reason why much of the successful legal tech is not really AI is simple. AI & Law is hard, very hard. In part this explains why many of us are here in this room. We are brave, we like the hard problems. In AI & Law they cannot be evaded.

Nederland ontwapent (The Netherlands disarm). Source: Nationaal Archief, 2.24.01.03, 918-0574 (Joost Evers, Anefo)

Let us look at an example of real law. We go back to the year when I was born when pacifism was still a relevant political attitude. In that year the Dutch Supreme court decided that the inscription ‘The Netherlands disarm’, mounted on a tower (Fig. 4 ) was not an offense. Footnote 16 The court admitted that indeed the sign could be considered a violation of Article 1 of the landscape management regulation of the province of North Holland, but the court decided that that regulation lacked binding power by a conflict with the freedom of speech, as codified in Article 7 of the Dutch constitution.

An example of a hard case. This outcome and its reasoning could not really be predicted, which is one reason why the case is still taught in law schools.

The example can be used to illustrate some of the tough hurdles for the development of AI & Law as they have been recognized from the start; here a list used by Rissland ( 1988 ) when reviewing Anne Gardner’s pioneering book ‘An AI approach to legal reasoning’ (Gardner 1987 ), a revision of her 1984 Stanford dissertation. Footnote 17 I am happy that both are present in this room today.

The subsumption model

Legal reasoning is rule-guided, rather than rule-governed In the example, indeed both the provincial regulation and the constitution were only guiding, not governing. Their conflict had to be resolved. A wise judge was needed.

Legal terms are open textured In the example it is quite a stretch to interpret a sign on a tower as an example of speech in the sense of freedom of speech, but that is what the court here did. It is the old puzzle of legally qualifying the facts, not at all an easy business, also not for humans. With my background in mathematics, I found legal qualification to be a surprisingly and unpleasantly underspecified problem when I took law school exams during my first years as assistant professor in legal informatics in Maastricht, back in the 1990s. Today computers also still would have a very hard time handling open texture.

Legal questions can have more than one answer, but a reasonable and timely answer must be given I have not checked how quickly the supreme court made its decision, probably not very quickly, but the case was settled. The conflict was resolved. A solution that had not yet been there, had been created, constructed. The decision changed a small part of the world.

The answers to legal questions can change over time In the example I am not sure about today’s law in this respect, in fact it is my guess that freedom of speech is still interpreted as broadly as here, and I would not be surprised when it is now interpreted even more broadly. But society definitely has changed since the late 1960s, and what I would be surprised about is when I would today see such a sign in the public environment.

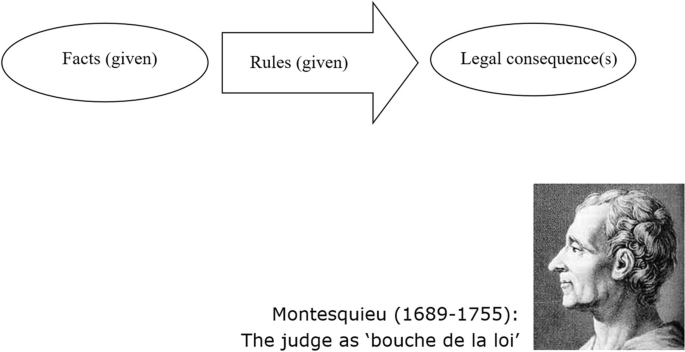

One way of looking at the hurdles is by saying that the subsumption model is false. According to the subsumption model of law there is a set of laws, thought of as rules, there are some facts,—and you arrive at the legal answers, the legal consequences by applying the rules to the facts (Fig. 5 ). The case facts are subsumed under the rules, providing the legal solution to the case. It is often associated with Montesquieu’s phrase of the judge as a ‘bouche de la loi’, the mouth of the law, according to which a judge is just the one who makes the law speak.

All hurdles just mentioned show that this perspective cannot be true. Rules are only guiding, terms are open-textured, there can be more answers, and things can change.

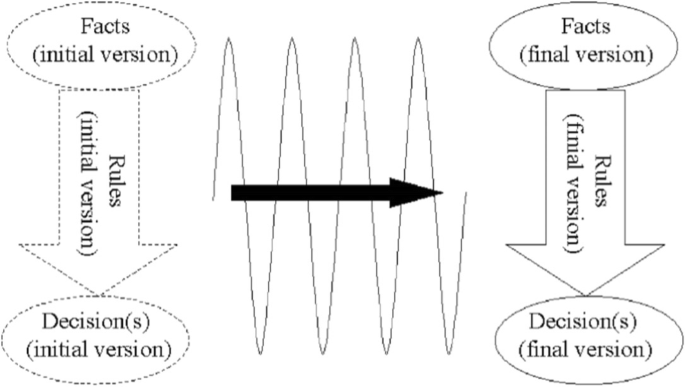

The theory construction model (Verheij 2003a , 2005 )

Hence an alternative perspective on what happens when a case is decided. Legal decision making is a process of constructing and testing a theory, a series of hypotheses that are gradually developed and tested in a critical discussion (Fig. 6 ). The figure suggests an initial version of the facts, an initial version of the relevant rules, and an initial version of the legal conclusions. Gradually the initial hypothesis is adapted. Think of what happens in a court proceedings, and in what in the Netherlands is called the ‘raadkamer’, the internal discussion among judges, where after a careful constructive critical discussion—if the judges get the time for that of course—finally a tried and tested perspective on the case is arrived at, showing the final legal conclusions subsuming the final facts under the final rules. This is the picture I used in the 2003 AI & Law special issue of the AI journal, edited by Edwina Rissland, Kevin Ashley, and Ronald Loui, two of them here in this room. A later version with Floris Bex emphasises that also the perspective on the evidence and how it supports the facts is gradually constructed (Bex and Verheij 2012 ). In our field, the idea of theory construction in the law has for instance been emphasised by McCarty ( 1997 ), Hafner and Berman ( 2002 ), Gordon ( 1995 ), Bench-Capon and Sartor ( 2003 ) and Hage et al. ( 1993 ).

4 AI as law

Today’s claim is that good AI requires a different way of doing AI, a way that we in the field of AI & Law have been doing all along, namely doing AI in a way that meets the requirements of the law, in fact in a way that models how things are done in the law. Let us discuss this perspective a bit further.

There can be many metaphors on what AI is and how it should be done, as follows.

AI as mathematics, where the focus is on formal systems;

AI as technology, where the focus is on the art of system design;

AI as psychology, where the focus is on intelligent minds;

AI as sociology, where the focus is on societies of agents.

And then AI as law, to which we return in a minute (Table 1 ).

In AI as mathematics, one can think of the logical and probabilistic foundations of AI, indeed since the start and still now of core importance. It is said that the namegiver of the field of AI—John McCarty—thought of the foundations of AI as an instance of logic, and logic alone. In contrast today some consider AI to be a kind of statistics 2.0 or 3.0.

In AI as technology, one can think of meticulously crafted rule-based expert systems or of machine learning algorithms evaluated on large carefully labeled data sets. In AI as technology, AI applications and AI research meet most directly.

In AI as psychology, one can think of the modeling of human brains as in cognitive modeling, or of the smart human-like algorithms that are sometimes referred to as cognitive computing.

In AI as sociology, one can think of multi-agent systems simulating a society and of autonomous robots that fly in flocks.

Perhaps you have recognized the list of metaphors as the ones used by Toulmin ( 1958 ) when he discussed what he thought of as a crisis in the formal analysis of human reasoning. He argued that the classical formal logic then fashionable was too irrelevant for what reasoning actually was, and he arrived at a perspective of logic as law. Footnote 18 What he meant was that counterargument must be considered, that rules warranting argumentative steps are material—and not only formal—, that these rules are backed by factual circumstances, that conclusions are often qualified, uncertain, presumptive, and that reasoning and argument are to be thought of as the outcome of debates among individuals and in groups (see also Hitchcock and Verheij 2006 ; Verheij 2009 ). All of these ideas emphasised by Toulmin have now been studied extensively, with the field of AI & Law having played a significant role in the developments. Footnote 19

The metaphors can also be applied to the law, exposing some key ideas familiar in law.

If we think of law as mathematics, the focus is on the formality of procedural rule following and of stare decisis where things are well-defined and there is little room for freedom.

In law as technology, one can think of the art of doing law in a jurisdiction with either a focus on rules, as in civil law systems, or with a focus on cases, as in common law systems.

In law as psychology, one can think of the judicial reasoning by an individual judge, and of the judicial discretion that is to some extent allowed, even wanted.

In law as sociology, the role of critical discussion springs to mind, and of regulating a society in order to give order and prevent chaos.

And finally the somewhat pleonastic metaphor of law as law, but now as law in contrast with the other metaphors. I think of two specific and essential ideas in the law, namely that government is to be bound by the rule of law, and that the goal of law is to arrive at justice, thereby supporting a good society and a good life for its citizens.

Note how this discussion shows the typically legal, hybrid balancing of different sides: rules and cases, regulations and decisions, rationality and interpretation, individual and society, boundedness and justice. And as we know this balancing best takes place in a constructive critical discussion.

Which brings us to bottom line of the list of AI metaphors (Table 1 ).

5. AI as law, where the focus is on hybrid critical discussion.

In AI as law, AI systems are to be thought of as hybrid critical discussion systems, where different hypothetical perspectives are constructed and evaluated until a good answer is found.

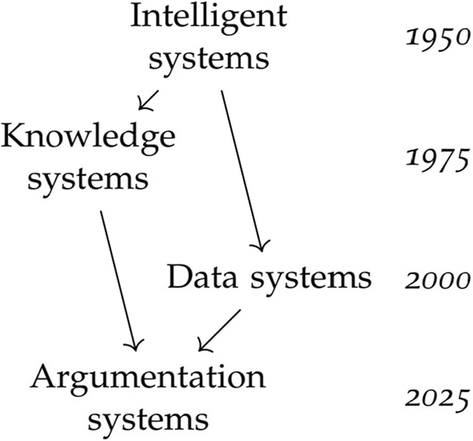

Bridging the gap between knowledge and data systems in AI (Verheij 2018 )

In this connection, I recently explained what I think is needed in AI (Fig. 7 ), namely the much needed step we have to make towards hybrid systems that connect knowledge representation and reasoning techniques with the powers of machine learning. In this diagram I used the term argumentation systems. But since argumentation has a very specific sound in this community, and perhaps to some feels as a too specific, too limiting perspective, I today speak of AI as Law in the sense of the development of hybrid critical discussion systems.

5 Topics in AI

Let me continue with a discussion of core topics in AI with the AI as Law perspective in mind. My focus is on reasoning, knowledge, learning and language.

5.1 Reasoning

First reasoning. I then indeed think of argumentation where arguments and counterarguments meet (van Eemeren et al. 2014 ; Atkinson et al. 2017 ; Baroni et al. 2018 ). This is connected to the idea of defeasibility, where arguments become defeated when attacked by a stronger counterargument. Argumentation has been used to address the deep and old puzzles of inconsistency, incomplete information and uncertainty.

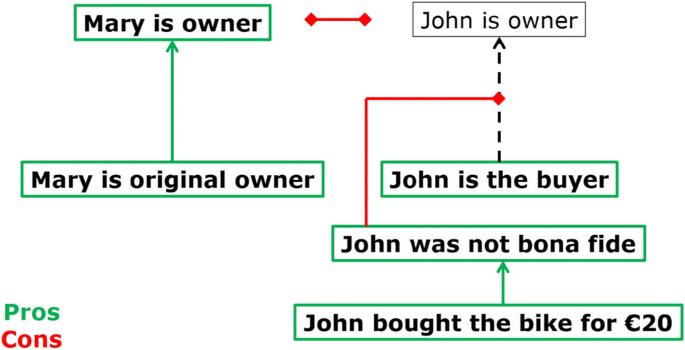

Here is an example argument about the Dutch bike owner Mary whose bike is stolen (Fig. 8 ). The bike is bought by John, hence both have a claim to ownership—Mary as the original owner, John as the buyer. But in this case the conflict can be resolved as John bought the bike for the low price of 20 euros, indicating that he was not a bona fide buyer. At such a price, he could have known that the bike was stolen, hence he has no claim to ownership as the buyer, and Mary is the owner.

- Argumentation

It is one achievement of the field of AI & Law that the logic of argumentation is by now well understood, so well that it can be implemented in argumentation diagramming software that applies the logic of argumentation, for instance the ArguMed software that I implemented long ago during my postdoc period in the Maastricht law school (Verheij 2003a , 2005 ). Footnote 20 It implements argumentation semantics of the stable kind in the sense of Dung’s abstract argumentation that was proposed some 25 years ago (Dung 1995 ), a turning point and a cornerstone in today’s understanding of argumentation, with many successes. Abstract argumentation also gave new puzzles such as the lack of standardization leading to all kinds of detailed comparative formal studies, and more fundamentally the multiple formal semantics puzzle. The stable, preferred, grounded and complete semantics were the four proposed by Dung ( 1995 ), quickly thereafter extended to 6 when the labeling-based stage and semi-stable semantics were proposed (Verheij 1996 ). But that was only the start because the field of computational argumentation was then still only emerging.

For me, it was obvious that a different approach was needed when I discovered that after combining attack and support 11 different semantics were formally possible (Verheij 2003b ), but practically almost all hardly relevant. No lawyer has to think about whether the applicable argumentation semantics is the semi-stable or the stage semantics.

One puzzle in the field is the following, here included after a discussion on the plane from Amsterdam to Montreal with Trevor Bench-Capon and Henry Prakken. A key idea underlying the original abstract argumentation paper is that derivation-like arguments can be abstracted from, allowing to focus only on attack. I know that for many this idea has helped them in their work and understanding of argumentation. For me, this was—from rather early on—more a distraction than an advantage as it introduced a separate, seemingly spurious layer. In the way that my PhD supervisor Jaap Hage put it: ‘those cloudy formal structures of yours’—and Jaap referred to abstract graphs in the sense of Dung—have no grounding in how lawyers think. There is no separate category of supporting arguments to be abstracted from before considering attack; instead, in the law there are only reasons for and against conclusions that must be balanced. Those were the days when Jaap Hage was working on Reason-Based Logic ( 1997 ) and I was helping him (Verheij et al. 1998 ). In a sense, the ArguMed software based on the DefLog formalism was my answer to removing that redundant intermediate layer (still present in its precursor the Argue! system), while sticking to the important mathematical analysis of reinstatement uncovered by Dung (see Verheij 2003a , 2005 ). For background on the puzzle of combining support and attack, see (van Eemeren et al. 2014 , Sect. 11.5.5).

But as I said from around the turn of the millenium I thought a new mathematical foundation was called for, and it took me years to arrive at something that really increased my understanding of argumentation: the case model formalism (Verheij 2017a , b ), but that is not for now.

5.2 Knowledge

The second topic of AI to be discussed is knowledge, so prominent in AI and in law. I then think of material, semi-formal argumentation schemes such as the witness testimony scheme, or the scheme for practical reasoning, as for instance collected in the nice volume by Walton et al. ( 2008 ).

I also think of norms, in our community often studied with a Hohfeldian or deontic logic perspective on rights and obligations as a background. Footnote 21 And then there are the ontologies that can capture large amounts of knowledge in a systematic way. Footnote 22

One lesson that I have taken home from working in the domain of law—and again don’t forget that I started in the field of mathematics where things are thought of as neat and clean—one lesson is that in the world of law things are always more complex than you think. One could say that it is the business of law to find the exactly right level of complexity, and that is often just a bit more complex than one’s initial idea. And if things are not yet complex now, they can become tomorrow. Remember the dynamics of theory construction that we saw earlier (Fig. 6 ).

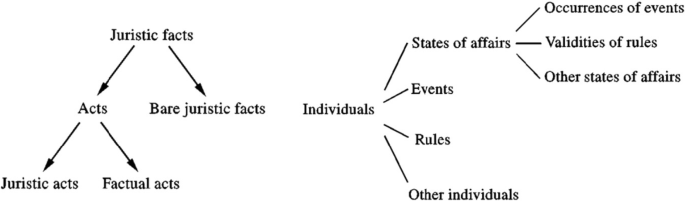

Types of juristic facts (left); tree of individuals (right) (Hage and Verheij 1999 )

Figure 9 (left) shows how in the law different categories of juristic facts are distinguished. Here juristic facts are the kind of facts that are legally relevant, that have legal consequences. They come in two kinds: acts with legal consequences, and bare juristic facts, where the latter are intentionless events such as being born, which still have legal consequences. And acts with legal consequences are divided in on the one hand juristic acts aimed at a legal consequence (such as contracting), and on the other factual acts, where although there is no legal intention, still there are legal consequences. Here the primary example is that of unlawful acts as discussed in tort law. I am still happy that I learnt this categorization of juristic facts in the Maastricht law school, as it has relevantly expanded my understanding of how things work in the world. And of how things should be done in AI. Definitely not purely logically or purely statistically, definitely with much attention for the specifics of a situation.

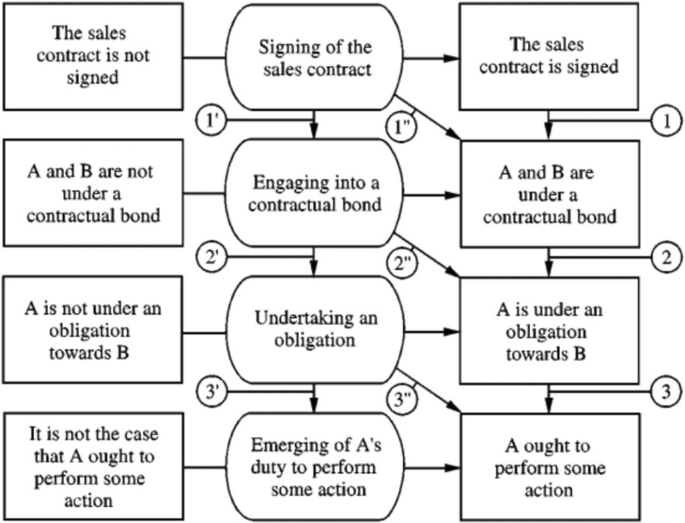

Signing a sales contract (Hage and Verheij 1999 )

Figure 9 (right) shows another categorization, prepared with Jaap Hage, that shows how we then approached the core categories of things, or ‘individuals’ that should be distinguished when analyzing the law: states of affairs, events rules, other individuals, and then the subcategories of event occurrences, rule validities and other states of affairs. And although such a categorization does have a hint of the baroqueness of Jorge Luis Borges’ animal taxonomy (that included those animals that belong to the emperor, mermaids and innumerable animals), the abstract core ontology helped us to analyze the relations between events, rules and states of affairs that play a role when signing a contract (Fig. 10 ). Indeed at first sight a complex picture. For now it suffices that at the top row there is the physical act of signing—say when the pen is going over the paper to sign—and this physical act counts as engaging in a contractual bond (shown in the second row), which implies the undertaking of an obligation (third row), which in turn leads to a duty to perform an action (at the bottom row). Not a simple picture, but as said, in the law things are often more complex than expected, and typically for good, pragmatic reasons.

The core puzzle for our field and for AI generally that I would like to mention is that of commonsense knowledge. This remains an essential puzzle, also in these days of big data; also in these days of cognitive computing. Machines simply don’t have commonsense knowledge that is nearly good enough. A knowledgeable report in the Communications of the ACM explains that progress has been slow (Davis and Marcus 2015 ). It goes back to 2015, but please do not believe it when it is suggested that things are very different today. The commonsense knowledge problem remains a relevant and important research challenge indeed and I hope to see more of the big knowledge needed for serious AI & Law in the future. Only brave people have the chance to make real progress here, like the people in this room.

One example of what I think is an as yet underestimated cornerstone of commonsense knowledge is the role of globally coherent knowledge structures—such as the scenarios and cases we encounter in the law. Our current program chair Floris Bex took relevant steps to investigate scenario schemes and how they are hierarchically related, in the context of murder stories and crime investigation (Bex 2011 ). Footnote 23 Our field would benefit from more work like this, that goes back to the frames and scripts studied by people such as Roger Schank and Marvin Minsky.

My current favorite kind of knowledge representation uses the case models mentioned before. It has for instance been used to represent how an appellate court gradually constructs its hypotheses about a murder case on the basis of the evidence, gradually testing and selecting which scenario of what has happened to believe or not (Verheij 2019 ), and also to the temporal development of the relevance of past decisions in terms of the values they promote and demote (Verheij 2016 ).

5.3 Learning

Then we come to the topic of learning. It is the domain of statistical analysis that shows that certain judges are more prone to supporting democrat positions than others, and that as we saw no longer is allowed in France. It is the domain of open data, that allows public access to legal sources and in which our community has been very active (Biagioli et al. 2005 ; Francesconi and Passerini 2007 ; Francesconi et al. 2010a , b ; Sartor et al. 2011 ; Athan et al. 2013 ). And it is the realm of neural networks, back in the days called perceptrons, now referred to as deep learning.

The core theme to be discussed here is the issue of how learning and the justification of outcomes go together, using a contemporary term: how to arrive at an explainable AI, an explainable machine learning. We have heard it discussed at all career levels, by young PhD students and by a Turing award winner.

The issue can be illustrated by a mock prediction machine for Dutch criminal courts. Imagine a button that you can push, that once you push it always gives the outcome that the suspect is guilty as charged. And thinking of the need to evaluate systems (Conrad and Zeleznikow 2015 ), this system has indeed been validated by the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics, that has the data that shows that this prediction machine is correct in 91 out of a 100 cases (Fig. 11 ). The validating data shows that the imaginary prediction machine has become a bit less accurate in recent years, presumably by changes in society, perhaps in part caused by the attention in the Netherlands for so-called dubious cases, or miscarriages of justice, which may have made judges a little more reluctant to decide for guilt. But still: 91% for this very simple machine is quite good. And as you know, all this says very little about how to decide for guilt or not.

Convictions in criminal cases in the Netherlands; source: Central Bureau of Statistics ( www.cbs.nl ), data collection of September 11, 2017

How hard judicial prediction really is, also when using serious machine learning techniques, is shown by some recent examples. Katz et al. ( 2017 ) that their US Supreme Court prediction machine could achieve a 70% accuracy. A mild improvement over the baseline of the historical majority outcome (to always affirm a previous decision) which is 60%, and even milder over the 10 year majority outcome which is 67%. The system based its predictions on features such as judge identity, month, court of origin and issue, so modest results are not surprising.

In another study Aletras and colleagues ( 2016 ) studied European Court of Human Rights cases. They used n-grams and topics as the starting point of their training, and used a prepared dataset to make a cleaner baseline of 50% accuracy by random guessing. They reached 79% accuracy using the whole text, and noted that by only using the part where the factual circumstances are described already an accuracy of 73% is reached.

Naively taking the ratios of 70 over 60 and of 79 over 50, one sees that factors of 1.2 and of 1.6 improvement are relevant research outcomes, but practically modest. And more importantly these systems only focus on outcome, without saying anything about how to arrive at an outcome, or about for which reasons an outcome is warranted or not.

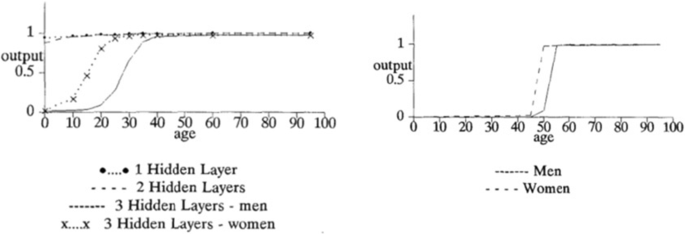

And indeed and as said before learning is hard, especially in the domain of law. Footnote 24 I am still a fan of an old paper by Trevor Bench-Capon on neural networks and open texture (Bench-Capon 1993 ). In an artificially constructed example about welfare benefits, he included different kinds of constraints: boolean, categorical, numeric. For instance, women were allowed the benefit after 60, and men after 65. Trevor found that after training, the neural network could achieve a high overall performance, but with somewhat surprising underlying rationales. In Fig. 12 , on the left, one can see that the condition starts to be relevant long before the ages of 60 and 65 and that the difference in gender is something like 15 years instead of 5. On the right, with a more focused training set using cases with only single failing conditions, the relevance started a bit later, but still too early, while the gender difference now indeed was 5 years.

Neural networks and open texture (Bench-Capon 1993 )

What I have placed my bets on is the kind of hybrid cases and rules systems that for us in AI & Law are normal. Footnote 25 I now represent Dutch tort law in terms of case models validating rule-based arguments (Verheij 2017b ) (cf. Fig. 13 below).

5.4 Language

Then language, the fourth and final topic of AI that I would like to discuss with you. Today the topic of language is closely connected to machine learning. I think of the labeling of natural language data to allow for training; I think of prediction such as by a search engine or chat application on a smartphone, and I think of argument mining, a relevant topic with strong roots in the field of AI & Law.

The study of natural language in AI, and in fact of AI itself, got a significant boost by IBM’s Watson system that won the Jeopardy! quiz show. For instance, Watson correctly recognized the description of ‘A 2-word phrase [that] means the power to take private property for public use’. That description refers to the typically legal concept of eminent domain, the situation in which a government disowns property for public reasons, such as the construction of a highway or windmill park. Watson’s output showed that the legal concept scored 98%, but also ‘electric company’ and ‘capitalist economy’ were considered with 9% and 5% scores, respectively. Apparently Watson sees some kind of overlap between the legal concept of eminent domain, electric companies and capitalist economy, since 98+9+5 is more than a 100 percent.

And IBM continued, as Watson was used as the basis for its debating technologies. In a 2014 demonstration, Footnote 26 the system is considering the sale of violent video games to minors. The video shows that the system finds reasons for and against banning the sale of such games to minors, for instance that most children who play violent games do not have problems, but that violent video games can increase children’s aggression. The video remains impressive, and for the field of computational argumentation that I am a member of it was somewhat discomforting that the researchers behind this system were then outsiders to the field.

The success of these natural language systems leads one to think about why they can do what they do. Do they really have an understanding of a complex sentence describing the legal concept of eminent domain; can they really digest newspaper articles and other online resources on violent video games?

These questions are especially relevant since in our field of AI & Law we have had the opportunity to follow research on argument mining from the start. Early and relevant research is by Raquel Mochales Palau and Sien Moens, who studied argument mining in a paper at the 2009 ICAIL conference ( 2009 , 2011 ). And as already shown in that paper, it should not be considered an easy task to perform argument mining. Indeed the field has been making relevant and interesting progress, as also shown in research presented at this conference, but no one would claim the kind of natural language understanding needed for interpreting legal concepts or online debates. Footnote 27

So what then is the basis of apparent success? Is it simply because a big tech company can do a research investment that in academia one can only dream of? Certainly that is a part of what has been going on. But there is more to it than that as can be appreciated by a small experiment I did, this time actually an implemented online system. It is what I ironically called Poor Man’s Watson, Footnote 28 which has been programmed without much deep natural language technology, just some simple regular expression scripts using online access to the Google search engine and Wikipedia. And indeed it turns out that the simple script can also recognize the concept of eminent domain: when one types ‘the power to take private property for public use’ the answer is ‘eminent domain’. The explanation for this remarkable result is that for some descriptions the correct Wikipedia page ends up high in the list of pages returned by Google, and that happens because we—the people—have been typing in good descriptions of those concepts in Wikipedia, and indeed Google can find these pages. Sometimes the results are spectacular, but also they are brittle since seemingly small, irrelevant changes can quickly break this simple system.

And for the debating technology something similar holds since there are web sites collecting pros and cons of societal debates. For instance, the web site procon.org has a page on the pros and cons of violent video games. Footnote 29 Arguments it has collected include ‘Pro 1: Playing violent video games causes more aggression, bullying, and fighting’ and ‘Con 1: Sales of violent video games have significantly increased while violent juvenile crime rates have significantly decreased’. The web site Kialo has similar collaboratively created lists. Footnote 30 Concerning the issue ‘Violent video games should be banned to curb school shootings’, it lists for instance the pro ‘Video games normalize violence, especially in the eyes of kids, and affect how they see and interact with the world’ and the con ‘School shootings are, primarily, the result of other factors that should be dealt with instead’.

Surely the existence of such lists typed in, in a structured way, by humans is a central basis for what debating technology can and cannot do. It is not a coincidence that—listening carefully to the reports—the examples used in marketing concern curated lists of topics. At the same time this does not take away the bravery of IBM and how strongly it has been stimulating the field of AI by its successful demos. And that also for IBM things are sometimes hard is shown by the report from February 2019 when IBM’s technology entered into a debate with a human debater, and this time lost. Footnote 31 But who knows what the future brings.

What I believe is needed is the development of an ever closer connection between complex knowledge representations and natural language explanations, as for instance in work by Charlotte Vlek on explaining Bayesian Networks (Vlek et al. 2016 ), which had nice connections to the work discussed by Jeroen Keppens yesterday ( 2019 ).

6 Conclusion

As I said I think the way to go for the field is to develop an AI that is much like the law, an AI where systems are hybrid critical discussion systems.

For after phases of AI as mathematics, as technology, as psychology, and as sociology—all still important and relevant—, an AI as Law perspective provides fresh ideas for designing an AI that is good (Table 1 ). And in order to build the hybrid critical discussion systems that I think are needed, lots of work is waiting in reasoning, in knowledge, in learning and in language, as follows.

For reasoning (Sect. 5.1 ), the study of formal and computational argumentation remains relevant and promising, while work is needed to arrive at a formal semantics that is not only accessible for a small group of experts.

For knowledge (Sect. 5.2 ), we need to continue working on knowledge bases large and small, and on systems with embedded norms. But I hope that some of us are also brave enough to be looking for new ways to arrive at good commonsense knowledge for machines. In the law we cannot do without wise commonsense.

For learning (Sect. 5.3 ), the integration of knowledge and data can be addressed by how in the law rules and cases are connected and influence one another. Only then the requirements of explainability and responsibility can be properly addressed.

For language (Sect. 5.4 ), work is needed in interpretation of what is said in a text. This requires an understanding in terms of complex, detailed models of a situation, like what happens in any court of law where every word can make a relevant difference.

Lots of work to do. Lots of high mountains to conquer.

The perspective of AI as Law discussed here today can be regarded as an attempt to broaden what I said in the lecture on ‘Arguments for good AI’ where the focus is mostly on computational argumentation (Verheij 2018 ). There I explain that we need a good AI that can give good answers to our questions, give good reasons for them, and make good choices. I projected that in 2025 we will have arrived at a new kind of AI systems bridging knowledge and data, namely argumentation systems (Fig. 7 ). Clearly and as I tried to explain today, there is still plenty of work to be done. I expect that a key role will be played by work in our field on connections between rules, cases and arguments, as in the set of cases formalizing tort law (Fig. 13 , left) that formally validate the legally relevant rule-based arguments (Fig. 13 , right).

Arguments, rules and cases for Dutch tort law (Verheij 2017b )

By following the path of developing AI as Law we can guard against technology that is bad for us, and that—unlike the guillotine I started with—is a really humane technology that directly benefits society and its citizens.

In conclusion, in these days of dreams and fears of AI and algorithms, our beloved field of AI & Law is more relevant than ever. We can be proud that AI & Law has worked on the design of socially aware, explainable, responsible AI for decades already.

And since we in AI & Law are used to address the hardest problems across the breadth of AI (reasoning, knowledge, learning, language)—since in fact we cannot avoid them—, our field can inspire new solutions. In particular, I discussed computational argumentation, schemes for arguments and scenarios, encoded norms, hybrid rule-case systems and computational interpretation.

We only need to look at what happens in the law. In the law, we see an artificial system that adds much value to our life. Let us take inspiration from the law, and let us work on building Artificial Intelligence that is not scary, but that genuinely contributes to a good quality of life in a just society. I am happy and proud to be a member of this brave and smart community and I thank you for your attention.

This text is an adapted version of the IAAIL presidential address delivered at the 17th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law (ICAIL 2019) in Montreal, Canada (Cyberjustice Lab, University of Montreal, June 19, 2019).

‘Beschonken Meppeler rijdt slapend over de snelweg’ (automatic translation: ‘Drunken Meppeler sleeps on the highway’), RTV Drenthe, May 17, 2019.

‘Can AI be a fair judge in court? Estonia thinks so’, Wired, March 25, 2019 (Eric Miller).

‘Het nieuwe datadieet van Google en Facebook’ (automatic translation: ‘The new data diet from Google and Facebook’, nrc.nl , May 11, 2019.

‘Zo stuurt en controleert China zijn burgers’ (automatic translation: ‘This is how China directs and controls its citizens’, nrc.nl , June 14, 2019.

bnvki.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Dutch-AI-Manifesto.pdf .

claire-ai.org .

iaail.org .

wetten.overheid.nl .

www.om.nl/onderwerpen/boetebase .

uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl .

www.belastingdienst.nl .

‘ICT-project basisregistratie totaal mislukt’ (automatic translation: ‘IT project basic registration totally failed’), nrc.nl , July 17, 2017.

techindex.law.stanford.edu .

Supreme Court The Netherlands, January 24, 1967: Nederland ontwapent (The Netherlands disarm).

For more on the complexity of AI & Law, see for instance (Rissland 1983 ; Sergot et al. 1986 ; Bench-Capon et al. 1987 , 2012 ; Rissland and Ashley 1987 ; Oskamp et al. 1989 ; Ashley 1990 , 2017 ; van den Herik 1991 ; Berman and Hafner 1995 ; Loui and Norman 1995 ; Bench-Capon and Sartor 2003 ; Sartor 2005 ; Zurek and Araszkiewicz 2013 ; Lauritsen 2015 ).

Toulmin ( 1958 ) speaks of logic as mathematics, as technology, as psychology, as sociology and as law (jurisprudence).

See for instance the research by Prakken ( 1997 ), Sartor ( 2005 ), Gordon ( 1995 ), Bench-Capon ( 2003 ) and Atkinson and Bench-Capon ( 2006 ). Argumentation research in AI & Law is connected to the wider study of formal and computational argumentation, see for instance (Simari and Loui 1992 ; Pollock 1995 ; Vreeswijk 1997 ; Chesñevar et al. 2000 ). See also the handbooks (Baroni et al. 2018 ; van Eemeren et al. 2014 ).

For some other examples, see (Gordon et al. 2007 ; Loui et al. 1997 ; Kirschner et al. 2003 ; Reed and Rowe 2004 ; Scheuer et al. 2010 ; Lodder and Zelznikow 2005 ).

See for instance (Sartor 2005 ; Gabbay et al. 2013 ; Governatori and Rotolo 2010 ).

See for instance (McCarty 1989 ; Valente 1995 ; van Kralingen 1995 ; Visser 1995 ; Visser and Bench-Capon 1998 ; Hage and Verheij 1999 ; Boer et al. 2002 , 2003 ; Breuker et al. 2004 ; Hoekstra et al. 2007 ; Wyner 2008 ; Casanovas et al. 2016 ).

For more work on evidence in AI & Law, see for instance (Keppens and Schafer 2006 ; Bex et al. 2010 ; Keppens 2012 ; Fenton et al. 2013 ; Vlek et al. 2014 ; Di Bello and Verheij 2018 ).

See also recently (Medvedeva et al. 2019 ).

See for instance work by (Branting 1991 ; Skalak and Rissland 1992 ; Branting 1993 ; Prakken and Sartor 1996 , 1998 ; Stranieri et al. 1999 ; Roth 2003 ; Brüninghaus and Ashley 2003 ; Atkinson and Bench-Capon 2006 ; Čyras et al. 2016 ).

Milken Institute Global Conference 2014, session ‘Why Tomorrow Won’t Look Like Today: Things that Will Blow Your Mind’, youtu.be/6fJOtAzICzw?t=2725 .

See for instance (Schweighofer et al. 2001 ; Wyner et al. 2009 , 2010 ; Grabmair and Ashley 2011 ; Ashley and Walker 2013 ; Grabmair et al. 2015 ; Tran et al. 2020 ).

Poor Man’s Watson, www.ai.rug.nl/~verheij/pmw .

videogames.procon.org .

kialo.com .

‘IBM’s AI loses debate to a human, but it’s got worlds to conquer’, cnet.com , February 11, 2019.

Aletras N, Tsarapatsanis D, Preoţiuc-Pietro D, Lampos V (2016) Predicting judicial decisions of the European Court of Human Rights: a natural language processing perspective. Peer J Comput Sci 2:1–19. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.93

Article Google Scholar

Ashley KD (1990) Modeling legal arguments: reasoning with cases and hypotheticals. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Google Scholar

Ashley KD (2017) Artificial intelligence and legal analytics: new tools for law practice in the digital age. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Ashley KD, Walker VR (2013) Toward constructing evidence-based legal arguments using legal decision documents and machine learning. In: Proceedings of the fourteenth international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 176–180. ACM, New York (New York)

Athan T, Boley H, Governatori G, Palmirani M, Paschke A, Wyner A (2013) OASIS LegalRuleML. In: Proceedings of the 14th international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 2013), pp 3–12. ACM Press, New York (New York)

Atkinson K, Bench-Capon TJM (2006) Legal case-based reasoning as practical reasoning. Artif Intell Law 13:93–131

Article MATH Google Scholar

Atkinson K, Baroni P, Giacomin M, Hunter A, Prakken H, Reed C, Simari G, Thimm M, Villata S (2017) Toward artificial argumentation. AI Mag 38(3):25–36

Baroni P, Gabbay D, Giacomin M, van der Torre L (eds) (2018) Handbook of formal argumentation. College Publications, London

MATH Google Scholar

Bench-Capon TJM (1993) Neural networks and open texture. In: Proceedings of the fourth international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 292–297. ACM Press, New York (New York)

Bench-Capon TJM (2003) Persuasion in practical argument using value-based argumentation frameworks. J Logic Comput 13(3):429–448

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Bench-Capon TJM, Sartor G (2003) A model of legal reasoning with cases incorporating theories and values. Artif Intell 150(1):97–143

Bench-Capon TJM, Robinson GO, Routen TW, Sergot MJ (1987) Logic programming for large scale applications in law: a formalisation of supplementary benefit legislation. In: Proceedings of the 1st international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 1987), pp 190–198. ACM, New York (New York)

Bench-Capon T, Araszkiewicz M, Ashley KD, Atkinson K, Bex FJ, Borges F, Bourcier D, Bourgine D, Conrad JG, Francesconi E, Gordon TF, Governatori G, Leidner JL, Lewis DD, Loui RP, McCarty LT, Prakken H, Schilder F, Schweighofer E, Thompson P, Tyrrell A, Verheij B, Walton DN, Wyner AZ (2012) A history of AI and Law in 50 papers: 25 years of the international conference on AI and law. Artif Intell Law 20(3):215–319

Berman DH, Hafner CL (1995) Understanding precedents in a temporal context of evolving legal doctrine. In: Proceedings of the fifth international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 42–51. ACM Press, New York (New York)

Bex FJ (2011) Arguments, stories and criminal evidence: a formal hybrid theory. Springer, Berlin

Bex FJ, Verheij B (2012) Solving a murder case by asking critical questions: an approach to fact-finding in terms of argumentation and story schemes. Argumentation 26:325–353

Bex FJ, van Koppen PJ, Prakken H, Verheij B (2010) A hybrid formal theory of arguments, stories and criminal evidence. Artif Intell Law 18:1–30

Biagioli C, Francesconi E, Passerini A, Montemagni S, Soria C (2005) Automatic semantics extraction in law documents. In: Proceedings of the 10th international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 2005), pp 133–140. ACM Press, New York (New York)

Boer A, Hoekstra R, Winkels R (2002) METAlex: legislation in XML. In: Bench-Capon TJM, Daskalopulu A, Winkels R (eds) Legal knowledge and information systems. JURIX 2002: the fifteenth annual conference. IOS Press, Amsterdam, pp 1–10

Boer A, van Engers T, Winkels R (2003) Using ontologies for comparing and harmonizing legislation. In: Proceedings of the 9th international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 60–69. ACM, New York (New York)

Branting LK (1991) Building explanations from rules and structured cases. Int J Man Mach Stud 34(6):797–837

Branting LK (1993) A computational model of ratio decidendi. Artif Intell Law 2(1):1–31

Breuker J, Valente A, Winkels R (2004) Legal ontologies in knowledge engineering and information management. Artif Intell Law 12(4):241–277

Brüninghaus S, Ashley KD (2003) Predicting outcomes of case based legal arguments. In: Proceedings of the 9th international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 2003), pp 233–242. ACM, New York (New York)

Casanovas P, Palmirani M, Peroni S, van Engers T, Vitali F (2016) Semantic web for the legal domain: the next step. Semant Web 7(3):213–227

Chesñevar CI, Maguitman AG, Loui RP (2000) Logical models of argument. ACM Comput Surv 32(4):337–383

Conrad JG, Zeleznikow J (2015) The role of evaluation in ai and law: an examination of its different forms in the ai and law journal. In: Proceedings of the 15th international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 2015), pp 181–186. ACM, New York (New York)

Čyras K, Satoh K, Toni F (2016) Abstract argumentation for case-based reasoning. In: Proceedings of the fifteenth international conference on principles of knowledge representation and reasoning (KR 2016), pp 549–552. AAAI Press

Davis E, Marcus G (2015) Commonsense reasoning and commonsense knowledge in artificial intelligence. Commun ACM 58(9):92–103

Di Bello M, Verheij B (2018) Evidential reasoning. In: Bongiovanni G, Postema G, Rotolo A, Sartor G, Valentini C, Walton DN (eds) Handbook of legal reasoning and argumentation. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 447–493

Chapter Google Scholar

Dung PM (1995) On the acceptability of arguments and its fundamental role in nonmonotonic reasoning, logic programming and n-person games. Artif Intell 77:321–357

Fenton NE, Neil MD, Lagnado DA (2013) A general structure for legal arguments about evidence using Bayesian Networks. Cognit Sci 37:61–102

Francesconi E, Passerini A (2007) Automatic classification of provisions in legislative texts. Artif Intell Law 15(1):1–17

Francesconi E, Montemagni S, Peters W, Tiscornia D (2010a) Integrating a bottom–up and top–down methodology for building semantic resources for the multilingual legal domain. In: Semantic processing of legal texts, pp 95–121. Springer, Berlin

Francesconi E, Montemagni S, Peters W, Tiscornia D (2010b) Semantic processing of legal texts: where the language of law meets the law of language. Springer, Berlin

Gabbay D, Horty J, Parent X, Van der Meyden R, van der Torre L (2013) Handbook of deontic logic and normative systems. College Publication, London

Gardner A (1987) An artificial intelligence approach to legal reasoning. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Gordon TF (1995) The pleadings game: an artificial intelligence model of procedural justice. Kluwer, Dordrecht

Gordon TF, Prakken H, Walton DN (2007) The Carneades model of argument and burden of proof. Artif Intell 171(10–15):875–896

Governatori G, Rotolo A (2010) Changing legal systems: legal abrogations and annulments in defeasible logic. Logic J IGPL 18(1):157–194

Grabmair M, Ashley KD (2011) Facilitating case comparison using value judgments and intermediate legal concepts. In: Proceedings of the 13th international conference on Artificial intelligence and law, pp 161–170. ACM, New York (New York)

Grabmair M, Ashley KD, Chen R, Sureshkumar P, Wang C, Nyberg E, Walker VR (2015) Introducing LUIMA: an experiment in legal conceptual retrieval of vaccine injury decisions using a uima type system and tools. In: Proceedings of the 15th international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 69–78. ACM, New York (New York)

Hafner CL, Berman DH (2002) The role of context in case-based legal reasoning: teleological, temporal, and procedural. Artif Intell Law 10(1–3):19–64

Hage JC (1997) Reasoning with rules. An essay on legal reasoning and its underlying logic. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Hage JC, Verheij B (1999) The law as a dynamic interconnected system of states of affairs: a legal top ontology. Int J Hum Comput Stud 51(6):1043–1077

Hage JC, Leenes R, Lodder AR (1993) Hard cases: a procedural approach. Artif Intell Law 2(2):113–167

Hitchcock DL, Verheij B (eds) (2006) Arguing on the toulmin model. New essays in argument analysis and evaluation (argumentation library, volume 10). Springer, Dordrecht

Hoekstra R, Breuker J, Di Bello M, Boer A (2007) The lkif core ontology of basic legal concepts. In: Casanovas P, Biasiotti MA, Francesconi E, Sagri MT (eds). Proceedings of LOAIT 2007. Second workshop on legal ontologies and artificial intelligence techniques, pp 43–63. CEUR-WS

Katz DM, Bommarito II MJ, Blackman J (2017) A general approach for predicting the behavior of the Supreme Court of the United States. PLoS ONE 12(4):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174698

Keppens J (2012) Argument diagram extraction from evidential Bayesian networks. Artif Intell Law 20:109–143

Keppens J (2019) Explainable Bayesian network query results via natural language generation systems. In: Proceedings of the 17th international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 2019), pp 42–51. ACM, New York (New York)

Keppens J, Schafer B (2006) Knowledge based crime scenario modelling. Expert Syst Appl 30(2):203–222

Kirschner PA, Shum SJB, Carr CS (2003) Visualizing argumentation: software tools for collaborative and educational sense-making. Springer, Berlin

Lauritsen M (2015) On balance. Artif Intell Law 23(1):23–42

Lodder AR, Zelznikow J (2005) Developing an online dispute resolution environment: dialogue tools and negotiation support systems in a three-step model. Harvard Negot Law Rev 10:287–337

Loui RP, Norman J (1995) Rationales and argument moves. Artif Intell Law 3:159–189

Loui RP, Norman J, Altepeter J, Pinkard D, Craven D, Linsday J, Foltz M (1997) Progress on room 5: a testbed for public interactive semi-formal legal argumentation. In: Proceedings of the 6th international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 207–214. ACM Press

McCarty LT (1989) A language for legal discourse. i. basic features. In: Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 1989), pp 180–189. ACM, New York (New York)

McCarty LT (1997) Some arguments about legal arguments. In: Proceedings of the 6th international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 1997), pp 215–224. ACM Press, New York (New York)

Medvedeva M, Vols M, Wieling M (2019) Using machine learning to predict decisions of the European court of human rights. Artif Intell Law. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-019-09255-y

Mochales Palau R, Moens MF (2009) Argumentation mining: the detection, classification and structure of arguments in text. In: Proceedings of the 12th international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 2009), pp ges 98–107. ACM Press, New York (New York)

Mochales Palau R, Moens MF (2011) Argumentation mining. Artif Intell Law 19(1):1–22

Oskamp A, Walker RF, Schrickx JA, van den Berg PH (1989) PROLEXS divide and rule: a legal application. In: Proceedings of the second international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 54–62. ACM, New York (New York)

Pollock JL (1995) Cognitive carpentry: a blueprint for how to build a person. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Prakken H (1997) Logical tools for modelling legal argument. A study of defeasible reasonong in law. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Prakken H, Sartor G (1996) A dialectical model of assessing conflicting arguments in legal reasoning. Artif Intell Law 4:331–368

Prakken H, Sartor G (1998) Modelling reasoning with precedents in a formal dialogue game. Artif Intell Law 6:231–287

Reed C, Rowe G (2004) Araucaria: software for argument analysis, diagramming and representation. Int J AI Tools 14(3–4):961–980

Rissland EL (1983) Examples in legal reasoning: Legal hypotheticals. In: Proceedings of the 8th international joint conference on artificial intelligence (IJCAI 1983), pp 90–93

Rissland EL (1988) Book review. An artificial intelligence approach to legal reasoning. Harvard J Law Technol 1(Spring):223–231

Rissland EL, Ashley KD (1987) A case-based system for trade secrets law. In: Proceedings of the first international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 60–66. ACM Press, New York (New York)

Roth B (2003) Case-based reasoning in the law. A formal theory of reasoning by case comparison. Dissertation Universiteit Maastricht, Maastricht

Sartor G (2005) Legal reasoning: a cognitive approach to the law. Vol 5 of Treatise on legal philosophy and general jurisprudence. Springer, Berlin

Sartor G, Palmirani M, Francesconi E, Biasiotti MA (2011) Legislative XML for the semantic web: principles, models, standards for document management. Springer, Berlin

Scheuer O, Loll F, Pinkwart N, McLaren BM (2010) Computer-supported argumentation: a review of the state of the art. Int J Comput Support Collab Learn 5(1):43–102

Schweighofer E, Rauber A, Dittenbach M (2001) Automatic text representation, classification and labeling in European law. In: Proceedings of the 8th international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 78–87. ACM, New York (New York)

Sergot MJ, Sadri F, Kowalski RA, Kriwaczek F, Hammond P, Cory HT (1986) The british nationality act as a logic program. Commun ACM 29(5):370–386

Simari GR, Loui RP (1992) A mathematical treatment of defeasible reasoning and its applications. Artif Intell 53:125–157

Skalak DB, Rissland EL (1992) Arguments and cases: an inevitable intertwining. Artif Intell Law 1(1):3–44

Stranieri A, Zeleznikow J, Gawler M, Lewis B (1999) A hybrid rule-neural approach for the automation of legal reasoning in the discretionary domain of family law in australia. Artif Intell Law 7(2–3):153–183

Toulmin SE (1958) The uses of argument. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Tran V, Le Nguyen M, Tojo S, Satoh K (2020) Encoded summarization: summarizing documents into continuous vector space for legal case retrieval. Artif Intell Law. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-020-09262-4

Valente A (1995) Legal knowledge engineering. A modelling approach. IOS Press, Amsterdam

van den Herik HJ (1991) Kunnen computers rechtspreken?. Gouda Quint, Arnhem

van Eemeren FH, Garssen B, Krabbe ECW, Snoeck Henkemans AF, Verheij B, Wagemans JHM (2014) Handbook of argumentation theory. Springer, Berlin

van Kralingen RW (1995) Frame-based conceptual models of statute law. Kluwer Law International, The Hague

Verheij B (1996) Two approaches to dialectical argumentation: admissible sets and argumentation stages. In: Meyer JJ, van der Gaag LC (eds) Proceedings of NAIC’96. Universiteit Utrecht, Utrecht, pp 357–368

Verheij B (2003a) Artificial argument assistants for defeasible argumentation. Artif Intell 150(1–2):291–324

Verheij B (2003b) DefLog: on the logical interpretation of prima facie justified assumptions. J Logic Comput 13(3):319–346

Verheij B (2005) Virtual arguments. On the design of argument assistants for lawyers and other arguers. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague

Verheij B (2009) The Toulmin argument model in artificial intelligence. Or: how semi-formal, defeasible argumentation schemes creep into logic. In: Rahwan I, Simari GR (eds) Argumentation in artificial intelligence. Springer, Berlin, pp 219–238

Verheij B (2016) Formalizing value-guided argumentation for ethical systems design. Artif Intell Law 24(4):387–407

Verheij B (2017a) Proof with and without probabilities. Correct evidential reasoning with presumptive arguments, coherent hypotheses and degrees of uncertainty. Artif Intell Law 25(1):127–154

Verheij B (2017b) Formalizing arguments, rules and cases. In: Proceedings of the 16th international conference on artificial intelligence and law (ICAIL 2017), pp 199–208. ACM Press, New York (New York)

Verheij B (2018) Arguments for good artificial intelligence. University of Groningen, Groningen. http://www.ai.rug.nl/~verheij/oratie/

Verheij B (2019) Analyzing the Simonshaven case with and without probabilities. Top Cognit Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12436

Verheij B, Hage JC, van den Herik HJ (1998) An integrated view on rules and principles. Artif Intell Law 6(1):3–26

Visser PRS (1995) Knowledge specification for multiple legal tasks; a case study of the interaction problem in the legal domain. Kluwer Law International, The Hague

Visser PRS, Bench-Capon TJM (1998) A comparison of four ontologies for the design of legal knowledge systems. Artif Intell Law 6(1):27–57

Vlek CS, Prakken H, Renooij S, Verheij B (2014) Building Bayesian Networks for legal evidence with narratives: a case study evaluation. Artif Intell Law 22(4):375–421

Vlek CS, Prakken H, Renooij S, Verheij B (2016) A method for explaining Bayesian Networks for legal evidence with scenarios. Artif Intell Law 24(3):285–324

Vreeswijk GAW (1997) Abstract argumentation systems. Artif Intell 90:225–279

Walton DN, Reed C, Macagno F (2008) Argumentation schemes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book MATH Google Scholar

Wyner A (2008) An ontology in OWL for legal case-based reasoning. Artif Intell Law 16(4):361

Wyner A, Angelov K, Barzdins G, Damljanovic D, Davis B, Fuchs N, Hoefler S, Jones K, Kaljurand K, Kuhn T et al (2009) On controlled natural languages: properties and prospects. In: International workshop on controlled natural language, pp 281–289. Berlin

Wyner A, Mochales-Palau R, Moens MF, Milward D (2010) Approaches to text mining arguments from legal cases. In: Semantic processing of legal texts, pp 60–79. Springer, Berlin

Zurek T, Araszkiewicz M (2013) Modeling teleological interpretation. In: Proceedings of the fourteenth international conference on artificial intelligence and law, pp 160–168. ACM, New York (New York)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Artificial Intelligence, Bernoulli Institute of Mathematics, Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands

Bart Verheij

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bart Verheij .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Verheij, B. Artificial intelligence as law. Artif Intell Law 28 , 181–206 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-020-09266-0

Download citation

Published : 14 May 2020

Issue Date : June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-020-09266-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Artificial intelligence

- Knowledge representation and reasoning

- Machine learning

- Natural language processing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Legal Fundaments

- Legal Research

The Role of AI Technology for Legal Research and Decision Making

- August 2023

- 10(07):2395-0056

- Amity University Dubai

- Guru Kashi University

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Sagar Varma Samanthapudi

- Piyush Rohella

- S. R. Ashokkumar

- M. Maria Antony Raj

- Sarmad Jaafar Naser

- S. Vinayagam

- T. Thirumalaikumari

- Mr. Gautam Joshi

- Tshilidzi Marwala

- Letlhokwa George Mpedi

- Baljinder Kaur

- Kulwinder Kaur

- Md Habibullah

- Vakil Singh

- Ms Ripendeep Kaur

- Sohrab Hussain

- Artif Intell Law

- Jonathan D. Touboul

- Syeda Marufa Yeasmin

- Manish Paul

- João Guerreiro

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

How AI will revolutionize the practice of law

Subscribe to the center for technology innovation newsletter, john villasenor john villasenor nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , center for technology innovation.

March 20, 2023

Artificial intelligence (AI) is poised to fundamentally reshape the practice of law. While there is a long history of technology-driven changes in how attorneys work, the recent introduction of large language model-based systems such as GPT-3 and GPT-4 marks the first time that widely available technology can perform sophisticated writing and research tasks with a proficiency that previously required highly trained people.

Law firms that effectively leverage emerging AI technologies will be able to offer services at lower cost, higher efficiency, and with higher odds of favorable outcomes in litigation. Law firms that fail to capitalize on the power of AI will be unable to remain cost-competitive, losing clients and undermining their ability to attract and retain talent.

Efficiency Improvements

Consider one of the most time-consuming tasks in litigation: extracting structure, meaning, and salient information from an enormous set of documents produced during discovery . AI will vastly accelerate this process, doing work in seconds that without AI might take weeks. Or consider the drafting of motions to file with a court. AI can be used to very quickly produce initial drafts, citing the relevant case law, advancing arguments, and rebutting (as well as anticipating) arguments advanced by opposing counsel. Human input will still be needed to produce the final draft, but the process will be much faster with AI.

More broadly, AI will make it much more efficient for attorneys to draft documents requiring a high degree of customization—a process that traditionally has consumed a significant amount of attorney time. Examples include contracts, the many different types of documents that get filed with a court in litigation, responses to interrogatories, summaries for clients of recent developments in an ongoing legal matter, visual aids for use in trial, and pitches aimed at landing new clients. AI could also be used during a trial to analyze a trial transcript in real time and provide input to attorneys that can help them choose which questions to ask witnesses.

The Legal Tech Startup Ecosystem

These opportunities will spur the creation of new legal tech companies. One example is Casetext, which was featured in an early March broadcast of MSNBC’s Morning Joe, and recently announced an AI legal assistant called CoCounsel. CoCounsel, which is powered by technology from OpenAI, the company that created ChatGPT, allows an attorney to ask the same sort of questions that he or she might ask of a junior associate, such as, “Can you research what courts in this jurisdiction have done in cases presenting similar fact patterns to the case we are working on?” Casetext is part of what is sure to become a rapidly growing ecosystem of legal tech companies offering AI products based on large language models.

There are also opportunities to use AI for more fully automated provision of legal services. Legal and policy frameworks will need to be updated to facilitate innovation in this space, while also identifying and protecting against the associated risks.

New Skills Required

For attorneys, getting the most out of AI tools will involve far more than just pushing a button. AI is most effective when it is used to complement human skills, and the people who learn how to leverage this collaboration well will get the most mileage out of AI tools.

This will require developing new skills, including knowing how to choose the right AI tool for a particular task, knowing how to construct the right queries and evaluate the relevance, quality, and accuracy of the responses (and then update the queries as needed), and being able synthesize the overall results into a cohesive, actionable picture. Attorneys will also need to be attentive to ensuring that any use of AI tools is done with appropriate attention to protecting confidentiality.

Law firms will need to institute new training so that practicing attorneys can adapt to this new environment. Law schools should update their curricula to ensure that they provide law students with instruction in how to use AI writing and research tools, as these skills will be in high demand among recruiters.

Broadening Access to Legal Services

AI also has the potential to dramatically broaden access to legal services, which are prohibitively expensive for many individuals and small businesses. As the Center for American Progress has written , “[p]romoting equal, meaningful access to legal representation in the U.S. justice system is critical to ending poverty, combating discrimination, and creating opportunity.”

AI will make it much less costly to initiate and pursue litigation. For instance, it is now possible with one click to automatically generate a 1000-word lawsuit against robocallers. More generally, drafting a well-written complaint will require more than a single click, but in some scenarios, not much more. These changes will make it much easier for law firms to expand services to lower-income clients.