- भाषा : हिंदी

- Classroom Courses

- Our Selections

- Student Login

- About NEXT IAS

- Director’s Desk

- Advisory Panel

- Faculty Panel

- General Studies Courses

- Optional Courses

- Interview Guidance Program

- Postal Courses

- Test Series

- Current Affairs

- Student Portal

- Prelims Analytica

- CSE (P) 2024 Solutions

- Pre Cum Main Foundation Courses

- 1 Year GSPM Foundation Course

- 2 Year Integrated GSPM Foundation Course: Elevate

- 3 Year Integrated GSPM Foundation Course: EDGE

- 2 Year GSPM Foundation with Advanced Integrated Mentorship (FAIM)

- Mentorship Courses

- 1 Year Advanced Integrated Mentorship (AIM)

- Early Start GS Courses

- 1 Year GS First Step

- Mains Specific

- Mains Advance Course (MAC) 2024

- Essay Guidance Program cum Test Series 2024

- Ethics Enhancer Course 2024

- Prelims Specific

- Weekly Current Affairs Course 2025

- Current Affairs for Prelims (CAP) 2025

- CSAT Course 2025

- CSAT EDGE 2025

- Optional Foundation Courses

- Mathematics

- Anthropology

- Political Science and International Relations (PSIR)

- Optional Advance Courses

- Political Science & International Relations (PSIR)

- Civil Engineering

- Electrical Engineering

- Mechanical Engineering

- Interview Guidance Programme / Personality Test Training Program

- GS + CSAT Postal Courses

- Current Affairs Magazine – Annual Subscription

- GS+CSAT Postal Study Course

- First Step Postal Course

- Postal Study Course for Optional Subjects

- Prelims Test Series for CSE 2025 (Offline/Online)

- General Studies

- GS Mains Test Series for CSE 2024

- Mains Test Series (Optional)

- PSIR (Political Science & International Relations)

- Paarth PSIR

- PSIR Answer Writing Program

- PSIR PRO Plus Test Series

- Mathematics Year Long Test Series (MYTS) 2024

- Indian Economic Services

- ANUBHAV (All India Open Mock Test)

- ANUBHAV Prelims (GS + CSAT)

- ANUBHAV Mains

- Headlines of the Day

- Daily Current Affairs

- Editorial Analysis

- Monthly MCQ Compilation

- Monthly Current Affairs Magazine

- Previous Year Papers

- Down to Earth

- Kurukshetra

- Union Budget

- Economic Survey

- Download NCERTs

- NIOS Study Material

- Beyond Classroom

- Toppers’ Copies

- Indian Polity

Uniform Civil Code (UCC): Meaning, Constitutional Provisions, Debates, Judgments & More

Rooted in the principles of equality, justice, and secularism, the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) has been a long-standing aspiration in India. Recent developments such as the passage of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) Bill in Uttarakhand have reignited the debates surrounding it. This article of Next IAS aims to explain the meaning of the UCC, related constitutional provisions, its benefits and challenges, and the way forward.

Meaning of the Uniform Civil Code

A Uniform Civil Code (UCC) refers to a common law that applies to all religious communities in personal matters such as marriage, inheritance, divorce, adoption, etc. It aims to replace the different personal laws that currently govern personal matters within different religious communities.

A UCC primarily aims to promote social harmony, gender equality, and secularism by eliminating disparate legal systems based on different religions and communities. Such a code seeks to ensure uniformity of laws not only between the communities but also within a community.

Constitutional Provisions

The Directive Principle of State Policies mentioned in Article 44 of the Indian Constitution provides that The State shall endeavor to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India. However, being a Directive Principle, it is not justiciable.

Status of the Uniform Civil Code in India

- As of now, India does not have a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) implemented at the national level. Instead, different personal laws based on religious customs and practices govern matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, and adoption for different religious communities.

- However, over the years, the central government as well as some states have made certain efforts towards the implementation of UCC. These efforts can be seen under the following two heads:

Steps taken by the Center

Special marriage act, 1954.

It was enacted to provide a secular alternative in marriages. It lays down provisions for civil marriage for the people of India and all Indian nationals in foreign countries, irrespective of religion or faith followed by either party.

Hindu Code Bills

The Hindu Code Bills , passed by the Parliament during the 1950s, are seen as a step towards the UCC. The following 4 Acts enacted under it seek to codify and bring uniformity in personal laws within the Hindu community:

- The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

- The Hindu Succession Act, 1956

- The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956

- The Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956

Note: The term ‘Hindu’ also includes Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists for the purpose of these laws.

Steps taken by the States

- This law in Goa is known as the Goa Civil Code or Goa Family Code and applies to all Goans, irrespective of their religious or ethnic community.

Uttarakhand

- The Bill provides for a common law for matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance of property, etc., and applies to all residents of Uttarakhand except Scheduled Tribes.

Present Status

- Nationwide implementation of a Uniform Civil Code remains an elusive goal.

- Hindu Marriage Act (1955)

- Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act (1937)

- Christian Marriage Act (1872)

- Parsee Marriage and Divorce Act (1937) etc

Debates in the Constituent Assembly

The issue of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) was debated extensively in the Constituent Assembly. Key arguments presented during the debate can be summarized as follows:

Arguments in Favor

The proponents of the UCC in the Constituent Assembly included members like B.R. Ambedkar, Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar, and K.M. Munshi. They put forth the following arguments in favor of a common civil code

- Equality and Justice : As per them, a common civil code would uphold the principles of equality and justice by ensuring uniform laws for all citizens, regardless of their religious affiliations.

- Secularism: A UCC would align with the secular nature of the Indian state, separating personal laws from religious considerations and promoting a unified national identity.

- Women’s Rights : Such a code would do away with discriminatory practices prevalent in personal laws, particularly those affecting women’s rights in matters such as marriage, divorce, and inheritance. Thus, it would promote gender equality and women empowerment.

Arguments Against

Opponents of the UCC in the Constituent Assembly included members such as Nazirrudin Ahmad and Mohammad Ismail Khan . They expressed the following reservations about the UCC:

- Religious Autonomy : It might cause potential infringement upon the religious autonomy of various communities as it would interfere with religious customs and traditions without the consent of those communities.

- Cultural Sensitivities : A single code might not adequately accommodate the unique customs and sensitivities of different communities. This, in turn, might hamper the diversity of religious and cultural practices in India.

- Social Unrest : Practices related to personal matters are deeply rooted in the religious and cultural identities of various communities in India. Implementing a uniform civil code might mean forcing them to relinquish their identities and could lead to social unrest and communal tensions.

Since a consensus on a UCC could not be reached in the Constituent Assembly, it was placed under the Directive Principles of State Policy under Article 44.

Supreme Court’s Views on Uniform Civil Code

The issue of a Uniform Civil Code has been dealt with by the Supreme Court in various cases. Accordingly, the Supreme Court has passed several landmark judgments and observations that have significantly contributed to the discourse on the UCC. Some of these include:

| In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that Muslim women were entitled to maintenance beyond the iddat period under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code. It observed that a UCC would help in removing contradictions based on certain religious ideologies. | |

| In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that a Hindu husband, upon converting to Islam, cannot enter into a second marriage without dissolving his first marriage. The court emphasized the need for a UCC to ensure gender justice and equality. | |

| In this case, the Supreme Court declared triple talaq unconstitutional, holding that it violated the fundamental rights of Muslim women. The verdict underscored the urgency of enacting a UCC to address gender discrimination and ensure uniform laws governing marriage and divorce. | |

| In this case, the Supreme Court struck down Section 497 of IPC relating to adultery on the grounds that it violated Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution. The court emphasized the need for gender-neutral laws and suggested the enactment of a UCC to address inconsistencies in personal laws. | |

| In this case, the Supreme Court addressed the ban on the entry of women of menstrual age into the Sabarimala temple in Kerala. The judgment highlighted the need for a UCC to harmonize conflicting rights and ensure gender equality across religions. |

Law Commission’s Views on Uniform Civil Code

The Law Commission of India has periodically examined the issue of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) and its implications for Indian society. Some notable observations made by the Law Commission are as follows:

21st Law Commission of India (headed by Justice Balbir Singh Chauhan)

- This commission expressed the view that implementing a UCC might not be necessary or desirable at this time. Instead, it suggested a series of reforms within various personal laws pertaining to different communities.

- Thus, it recommended amendments and changes to existing family laws with the aim of ensuring justice and equality within all religions, rather than proposing a single uniform law.

22nd Law Commission of India (headed by Justice Rituraj Awasthi)

- This commission has issued a consultation paper on the UCC, seeking public feedback on the issue.

- Diverse sections of the population including religious organizations, legal experts, policymakers, and civil society groups have been asked to furnish their views regarding the feasibility, implications, and potential framework for a UCC.

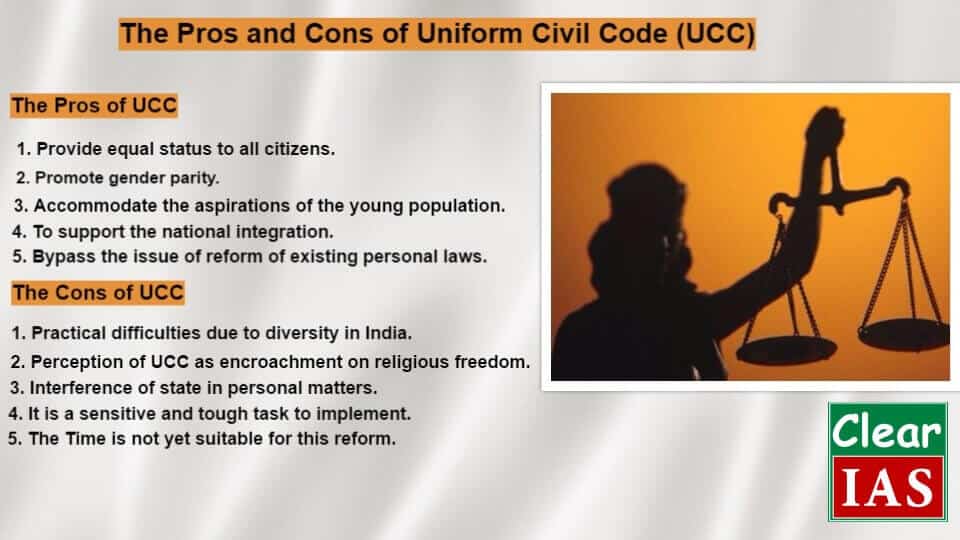

Arguments in Favour of Uniform Civil Code

Based on the above-discussed discourse and the opinion of the experts, the following arguments can be put forth in favor of implementing a Uniform Civil Code:

- Simplifies Legal System : Having one set of laws for all will simplify the personal laws that are at present segregated on the basis of religious beliefs. This, in turn, would simplify the legal framework and the legal process.

- Promotes Equality : A UCC aims to ensure that all citizens of India, irrespective of their religion, are treated equally under the law. Thus, it will help promote the ideal of equality as envisaged in the Preamble.

- Promotes Secularism : A UCC would help towards achieving a secular state where the law is the same for all, regardless of religion. Thus, it would help promote the ideal of Secularism in the country.

- Promotes Gender Equality and Women Empowerment : The current personal laws of different religious communities put women in a disadvantageous position in matters related to marriage, divorce, inheritance, and property rights. Implementing a UCC would ensure equal treatment and opportunities for women in these areas, thus promoting the cause of Gender Equality and Women Empowerment.

- Promotes National Integratio n: A common set of laws for all citizens will promote a sense of oneness and the national spirit. This, in turn, will promote national unity and integrity and help India emerge as a nation in the true sense.

- Promotes Modernization : By doing away with outdated religious laws, a UCC would reflect the progressive aspirations of a modern democratic society based on current values and ethics.

- Elevates Global Image : Adopting a UCC would enhance India’s international image as a progressive and inclusive democracy committed to upholding the principles of equality, justice, and secularism. It would align India’s legal framework with global human rights standards and modern democratic practices.

Arguments Against Uniform Civil Code

Several critics have put forth the following arguments against implementing a Uniform Civil Code:

- Lack of Consensus : There is no consensus among various communities about what the UCC should entail. The lack of agreement on the principles and provisions of a common code makes it difficult to envision a UCC that is acceptable to all.

- Implementational Challenges : The sheer diversity of laws governing different communities makes the drafting and implementation of a UCC a daunting task. Creating a code that adequately addresses and respects the nuances of each community’s laws won’t be easy.

- Threat to Religious Freedom : Implementing a UCC would infringe upon the religious freedom of citizens by imposing uniform laws that may contradict their religious beliefs and practices. This might mean state interference in religious affairs.

- Threat to Cultural Diversity : Imposing uniform laws across such diverse communities would ignore the unique cultural practices, traditions, customs, and sensitivities of different religious groups. Overall, it might go against the idea of diversity.

- Fear of Majoritarianism : There is a concern that a UCC could reflect the beliefs and practices of the majority religion. Thus, it may be akin to imposing a majoritarian view on minorities and hence marginalization of minority groups.

- Threat of Social Unrest : Given the sensitivity around religious and cultural practices, there is a risk that attempting to implement a UCC could lead to social unrest and deepen communal divides.

- Undermining Federalism : Personal matters being under the Concurrent List, both the Parliament and state legislature are empowered to make laws on them. Imposing a UCC could undermine the federal structure by encroaching upon the rights of states to legislate on such matters.

Way Forward

- Dialogue and Consultation : There needs to be extensive dialogue and consultation with all stakeholders, including religious communities, legal experts, policymakers, and civil society organizations, to understand concerns and perspectives regarding the UCC.

- Public Awareness and Education : Conducting awareness campaigns and educational programs to inform the public about the benefits and implications of the UCC can help build consensus and garner support for its implementation.

- Piecemeal Approach : A piecemeal approach of codifying the different personal laws and putting them for public debates and scrutiny can be adopted. This will arouse public consciousness towards UCC.

- Inclusivity : A UCC should be drafted in such a manner that respects religious diversity while promoting gender equality and justice is crucial.

- Gradual Implementation : Implementing the UCC in a phased manner, starting with areas where there is least resistance and gradually expanding its scope, can help mitigate concerns and ensure a smoother transition.

- Monitoring and Evaluation : As and when a UCC is implemented, a mechanism should be established for monitoring its implementation, and evaluating its impact on society. This will help make necessary adjustments and improvements and smoothen the process of its implementation.

- Political Will : Political leaders must demonstrate leadership and a strong will to navigate through the complexities and challenges associated with the UCC implementation.

In conclusion, the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) stands as a critical imperative for India’s journey towards social justice, equality, and secularism. Despite some drawbacks and implementational challenges, UCC offers immense potential benefits. From ensuring gender equality and social cohesion to simplifying legal procedures and fostering modernization, the UCC holds the promise of protecting the oppressed as well as promoting national unity and solidarity.

Read out our detailed article on the Uttarakhand UCC Bill

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the uniform civil code.

UCC refers to a common law being applicable to all religious communities in personal matters such as marriage, inheritance, etc. It aims to replace the different personal laws that currently govern personal matters within different religious communities.

What is the Need for a Uniform Civil Code in India?

The need for a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India arises from the imperative of establishing equality, secularism, and national integration in India.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Evolution of panchayati raj institutions (pris) in india, leaders in parliament, leader of opposition (lop), judicial review: meaning, scope, significance & more, parliament of india, rajya sabha: composition, system of elections & more, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Featured Post

NEXT IAS (Delhi)

Old rajinder nagar.

- 27-B, Pusa Road, Metro Pillar no.118, Near Karol Bagh Metro, New Delhi-110060

Mukherjee Nagar

- 1422, Main Mukherjee Nagar Road. Near Batra Cinema New Delhi-110009

NEXT IAS (Jaipur)

- NEXT IAS - Plot No - 6 & 7, 3rd Floor, Sree Gopal Nagar, Gopalpura Bypass, Above Zudio Showroom Jaipur (Rajasthan) - 302015

NEXT IAS (Prayagraj)

- 31/31, Sardar Patel Marg, Civil Lines, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh - 211001

NEXT IAS (Bhopal)

- Plot No. 46 Zone - 2 M.P Nagar Bhopal - 462011

- 8827664612 ,

Devices of Parliamentary Proceedings: Meaning, Types, Applications & Importance

- Nov 13, 2023

Constitutional Aspects Revolving Around Uniform Civil Code: A Critical Analysis

Updated: Mar 11

Authored by Huzaifa Aslam, a 4th-year Law Student at the Aligarh Muslim University

Introduction

The Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is a concept that has long been debated and discussed in the Indian socio-legal landscape. At its core, a UCC seeks to provide a uniform set of laws governing personal matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, and property for all citizens, irrespective of their religious beliefs or community affiliations. In essence, it calls for the unification of personal laws that currently vary among different religious communities in India, including Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and others.

The relevance of the UCC in India stems from the country’s unique diversity, both in terms of religion and culture. India is a secular nation that upholds the principles of equality and justice for all its citizens, regardless of their faith or background. However, this diversity has led to the existence of distinct personal laws for various religious groups, often resulting in disparities in legal rights, particularly concerning family matters.

The debate surrounding the UCC is multifaceted and touches upon various aspects of Indian society. It encompasses issues related to gender equality, individual rights, religious freedom, and social justice. Advocates argue that Aditya Bharat Manubarwala strongly advocated in favour of the Centre in their proposal of UCC that a UCC would harmonise conflicting personal laws, eliminate gender biases inherent in some of these laws, and promote a more equitable and just legal framework.

On the other hand, opponents contend that implementing a UCC could infringe upon religious freedom and cultural practices, potentially alienating minority communities. They argue that personal laws are deeply rooted in religious traditions and should be preserved as part of the unique fabric of Indian society.

The relevance of the UCC in India cannot be overstated. It represents an ongoing constitutional and societal debate that seeks to strike a balance between uniformity and diversity, between individual rights and community rights, and between tradition and modernity. This critical analysis of the constitutional aspects surrounding the UCC will delve deeper into these complexities, exploring the historical context, constitutional framework, legal and ethical implications, political and social factors, comparative perspectives, case studies, and the challenges and prospects associated with this important issue in India.

Historical Context of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) Debate in India and Key Milestones

The debate surrounding the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India is deeply rooted in the country’s historical, cultural, and political landscape. Understanding its historical context and key milestones is crucial to comprehending the complexity of this ongoing discussion.

Ancient and Medieval India

In ancient and medieval India, personal laws were primarily governed by customary practices and religious texts specific to various communities. Hindu personal laws were influenced by texts like Manusmriti, while Muslim personal laws were derived from the Quran and Hadith. Different communities have their own distinct sets of rules and practices.

Colonial Era (19th and early 20th centuries)

The genesis of the UCC debate can be traced back to the colonial era when British colonial rulers introduced certain reforms related to personal laws. The British government, as part of its “divide and rule” policy, maintained a somewhat hands-off approach commonly referred to as “non-interference” or “non-regulation” towards religious and personal laws, allowing different religious communities to govern their respective personal matters. This laid the foundation for the pluralistic legal system in India.

Hindu Code Bill (1955-56)

One of the first significant milestones in the UCC debate occurred when the Indian government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, initiated the Hindu Code Bill in the mid-1950s. This ambitious legislative effort aimed to reform and codify Hindu personal laws, covering issues like marriage, divorce, and succession. The bill faced staunch opposition from conservative groups and religious leaders but eventually passed, marking the beginning of legal reforms in personal laws.

Goa’s Adoption of a UCC ( 1961 )

After Goa’s liberation from Portuguese colonial rule in 1961, the region adopted a Uniform Civil Code. This move was significant as it demonstrated the feasibility of implementing a UCC in India, albeit in a relatively small state.

Shah Bano Case (1985)

The landmark Shah Bano case brought the issue of gender justice and the need for uniformity in personal laws to the forefront. The Supreme Court’s judgment in favour of Shah Bano, a Muslim woman seeking maintenance from her husband after divorce, sparked a nationwide debate on the rights of Muslim women and the reform of Muslim personal law.

Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Babri Masjid Dispute (late 1980s and early 1990s)

The late 1980s and early 1990s witnessed the rise of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and the highly contentious Babri Masjid demolition. These events heightened religious tensions and influenced the UCC debate, as various interest groups called for uniformity in laws, especially in relation to religious practices and places of worship.

Recommendations of the Law Commission

The Law Commission of India has periodically examined and made recommendations regarding the implementation of a UCC. In its report , the Commission has highlighted the need for reforms in personal laws to ensure gender equality and social justice.

Current Debates and Legal Cases

The UCC debate continues to be a prominent issue in contemporary India. Various legal cases, such as the Triple Talaq case and debates around the rights of women in different religious communities, have reignited discussions about the necessity and feasibility of a UCC.

These historical milestones and events reflect the evolving nature of the UCC debate in India. It is a topic deeply intertwined with questions of religious freedom, social justice, and gender equality. The historical context highlights both the challenges and opportunities associated with the implementation of a UCC in a diverse and pluralistic society like India.

The Relevant Provisions in the Indian Constitution Related to Personal Laws, including Articles 44, 25, and 26

The Indian Constitution contains several provisions that are relevant to the discussion of personal laws, particularly in the context of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC). These provisions include Article 44 , Article 25 , and Article 26 .

Article 44 of the Indian Constitution is a Directive Principle of State Policy, and it states that “ The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a Uniform Civil Code throughout the territory of India.” This article envisions a UCC that would replace the existing personal laws that vary based on religion and community and aims to promote uniform laws governing various aspects of personal life, such as marriage, divorce, adoption, and inheritance, irrespective of an individual’s religion. While Directive Principles are not legally enforceable, they serve as guiding principles for the government.

Significance :

The UCC seeks to establish equality and justice by eliminating discriminatory practices within personal laws based on religion or community.

Article 44 in the Directive Principles reflects the framers’ vision of a modern, progressive, and unified legal framework for personal laws in India. It emphasises the need to harmonise conflicting personal laws to ensure gender equality and social justice. However, the framers also recognied the complexity of the issue and the importance of respecting diverse religious and cultural practices.

Article 25 (Freedom of Religion)

Article 25 guarantees the freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion. However, it is subject to public order, morality, health, and other fundamental rights.

Article 25 upholds the individual’s right to religious freedom, ensuring that personal laws based on religion can exist.

The state can intervene to regulate religious practices when they infringe upon public order, morality, or health.

Article 26 (Freedom to Manage Religious Affairs)

Article 26 grants religious denominations the right to manage their religious affairs, including establishing institutions for religious and charitable purposes.

While Article 26 allows religious groups to manage their affairs independently, it does not grant them absolute autonomy. The state can regulate these institutions in the interest of public order, morality, and other fundamental rights.

Delicate Balance between Individual Rights and State Intervention in Religious Matters

The debate over a UCC involves navigating a delicate balance between individual rights and state intervention in religious matters.

Individual Rights

Article 25 guarantees the freedom of religion, allowing individuals to practice their faith and follow their personal laws. Critics of a UCC argue that imposing uniform laws could infringe upon these individual rights, particularly for religious minorities, as it may disrupt their traditional practices and beliefs.

State Intervention

Article 44 suggests that the state should aim for a UCC to promote uniformity and social justice. However, any attempt to implement a UCC should carefully consider the religious and cultural diversity of India and the principles of federalism, respecting the autonomy of religious institutions.

The delicate balance revolves around upholding individual rights to religious freedom while considering the broader goals of equality, gender justice, and social cohesion. Proponents argue that a UCC would promote gender equality and social harmony, while opponents emphasise the importance of preserving religious and cultural diversity. Achieving this balance requires comprehensive legal reforms that are sensitive to the needs and rights of all citizens. The debate surrounding the UCC remains a complex and multifaceted issue in India’s legal and social landscape.

Challenges and Prospects

Implementing a Universal Civil Code (UCC) in India is a complex and contentious issue, fraught with various challenges and obstacles. These hurdles span legal, social, and political dimensions:

Religious and Cultural Diversity

India is a highly diverse country with multiple religions, cultures, and traditions. Implementing a UCC that respects this diversity while providing a uniform legal framework is a significant challenge.

Constitutional Amendments

To implement a UCC, India may need to amend various provisions of its constitution. This requires significant political consensus and effort, which can be difficult to achieve.

Religious Opposition

Many religious groups and leaders may oppose a UCC on the grounds that it could interfere with their religious laws and customs. This opposition can lead to social and political tensions.

Political Divisions

The issue of a UCC often becomes politicized, with different political parties taking varying positions. Achieving bipartisan support for such a significant legal change is challenging.

Legal Complexity

Drafting a comprehensive UCC that covers personal laws related to marriage, divorce, inheritance, and more while ensuring fairness and equity is legally complex and requires careful consideration.

Gender Equality

One of the goals of a UCC is to promote gender equality. However, achieving this may face resistance from traditional and patriarchal norms prevalent in some communities.

Public Opinion

Public opinion on a UCC is diverse, and there may be resistance from segments of the population who fear the loss of their cultural and religious identity.

Enforcement and Implementation

Even if a UCC is enacted, its effective enforcement and implementation can be challenging, especially in remote or culturally conservative areas.

International Obligations

India has international obligations under various human rights conventions. Implementing a UCC must align with these obligations, adding complexity to the process.

Judicial Backlog

Implementing a UCC could lead to an increase in legal disputes as personal laws are standardized. India already faces a significant backlog of cases, and this could exacerbate the problem.

Socioeconomic Impact

Changes in personal laws can have socioeconomic implications, particularly for vulnerable groups. Ensuring that a UCC doesn’t disproportionately affect marginalized communities is crucial.

Consultation and Consensus- Building

Achieving consensus among diverse stakeholders, including religious and cultural leaders, legal experts, and political parties, is a major challenge.

Education and Awareness

Educating the public about the benefits and implications of a UCC is essential for its successful implementation.

Landmark Legal Cases Related to Personal Laws and the UCC: Highlighting Their Significance

Several landmark legal cases in India have had a significant impact on the debate surrounding personal laws and the Universal Civil Code (UCC). These cases have addressed issues related to gender equality, religious practices, and the need for uniformity in personal laws. Here are some notable cases:

This is one of the most famous cases related to personal laws and the UCC. Shah Bano, a Muslim woman, sought maintenance from her husband after being divorced through the Islamic practice of triple talaq. The Supreme Court ruled in her favour, recognising her right to maintenance under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code, irrespective of her religion.

The case sparked a nationwide debate and led to the passage of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act in 1986, which limited the application of Section 125 in cases of Muslim divorce. This case highlighted the need for reforms in Muslim personal laws.

Mary Roy Case (1986)

In this case, Mary Roy, a Christian woman from Kerala, challenged the discriminatory provisions of the Travancore Christian Succession Act, which favored male heirs in matters of inheritance. The Supreme Court ruled in her favor, holding that gender discrimination in inheritance laws violated the constitutional principles of equality.

This case set an important precedent for gender equality in personal laws and contributed to the broader discourse on uniformity in personal laws.

Danial Latifi Case (2001)

This case involved issues related to the maintenance of Muslim women after divorce. The Supreme Court emphasised that Muslim women have the right to claim maintenance beyond the iddat period (the period of waiting after divorce) under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code.

The case reaffirmed the principle that gender justice and equality are paramount and that personal laws should not infringe upon these principles.

Sarla Mudgal Case (1995) and Lily Thomas Case (2000)

These cases dealt with the practice of bigamy among Hindu men who converted to Islam to marry another woman without divorcing their first wife. The Supreme Court held that such conversions for the sole purpose of bigamy were unacceptable and not protected by the freedom to practice religion.

These cases raised questions about the need for uniformity and reform in personal laws to prevent misuse.

Triple Talaq Cases (2017)

A series of cases challenging the practice of triple talaq (instant divorce) in Islam led to a landmark judgment by the Supreme Court in 2017. The court declared the practice of triple talaq unconstitutional, stating that it violated the rights of Muslim women.

This judgment was seen as a significant step towards reforming Muslim personal laws and ensuring gender equality.

Comparative Analysis of India’s Approach to Personal Laws with Other Countries That Have and Do Not Have a UCC

India’s approach to personal laws is unique in its complexity due to its diverse religious and cultural landscape. Let’s compare India’s approach to personal laws with examples from countries with or without a Universal Civil Code (UCC) and analyse the lessons India can learn:

Countries with a UCC or Uniform Personal Laws

Turkey, historically a Muslim-majority country, adopted a UCC in the early 20th century under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s leadership. The UCC abolished Islamic legal provisions and introduced a secular legal system.

Lesson for India : Turkey’s experience shows that a UCC can be implemented even in a predominantly Muslim country, emphasising secularism while respecting religious diversity.

Tunisia, another Muslim-majority country, implemented a UCC in 1956, making significant reforms to personal laws, including women’s rights in marriage, divorce, and inheritance.

Countries without a UCC or Uniform Personal Laws

United states.

The United States does not have a UCC. Instead, it follows a system of state-specific family laws, leading to variations in marriage, divorce, and inheritance laws across states.

Lesson for India : The U.S. experience highlights the challenges of legal complexity and inconsistencies when personal laws are not standardised at the national level.

United Kingdom

The UK has a diverse population with various religious communities, but it does not have a UCC. It allows religious arbitration councils, such as Sharia councils for Muslims, for family matters, which operate parallel to the legal system.

Lesson for India : The UK’s approach illustrates how countries can accommodate diverse religious practices while maintaining a secular legal framework. However, it raises concerns about the potential for parallel legal systems and ensuring individual rights are upheld.

Canada, known for its multiculturalism, respects religious and cultural diversity. It does not have a UCC but ensures that its legal system is secular and protects individual rights.

Canada’s approach highlights the importance of upholding secular principles while respecting cultural and religious diversity.

Lessons for India

Secularism : India can learn from Turkey and Tunisia, where secular principles guided the implementation of UCC while respecting religious diversity.

Gender Equality: International experiences show that implementing a UCC can be a means to advance gender equality and women’s rights.

Complexity and Inconsistency: India can learn from the U.S. about the challenges of legal complexity and inconsistencies when personal laws vary by region.

Accommodating Diversity: The UK and Canada demonstrate how to accommodate religious and cultural diversity while maintaining a secular legal framework. India can explore similar models that respect diversity but emphasise secular laws.

Legal Oversight: India should consider the potential for parallel legal systems, as seen in the UK, and ensure that religious arbitration does not infringe upon individual rights.

Balancing Cultural Sensitivity and Human Rights: India can draw lessons from countries that have found a balance between cultural sensitivity and upholding human rights and equality under the law.

India can benefit from studying international experiences to inform its approach to personal laws and the ongoing UCC debate. The key challenge lies in finding a balance that respects cultural and religious diversity while upholding secular and equitable legal principles.

The Constitutional Aspects Revolving Around the Uniform Civil Code highlights the tension between the principles of secularism and individual rights on one side and the preservation of religious and cultural diversity on the other. The debate revolves around how to reconcile these constitutional aspects while ensuring justice and equality for all citizens.

The implementation of a UCC is often a politically contentious issue. Political parties may exploit this debate, and it can lead to polarisation and social unrest. Critics argue that a UCC may infringe upon the religious freedom of minorities by imposing secular laws that conflict with their religious practices and customs. For some minority groups, religious and cultural practices are closely intertwined. Implementing a UCC could potentially erode traditional customs, raising questions about the preservation of cultural heritage. Depending on the existing legal framework, implementing a UCC may require amendments to the constitution, which can be a complex and time-consuming process. To address the concerns of religious and cultural minorities, it’s crucial to engage in extensive consultations and consider their perspectives during the drafting and implementation of a UCC.

Recent Posts

A Precautionary Measure?: The Demarcation of Separation of Power Between Judiciary and Legislature

EWS Reservation In India: A Blow To Social Justice?

Unveiling the Veil: Assessing Corporate Donor Privacy in Electoral Funding

Disclaimer : The Society For Constitutional Law Discussion makes endeavours to ensure that the information published on the website is factual and correct. However, some of the content may contain errors. In the blog/article, all views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of TSCLD or its members in any manner whatsoever. In case of any Query or Concern, please reach out to us.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

3 Comparative Lessons and the Case of India

- Published: April 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter analyses the case of India in depth. It explores the role of community law in the personal law of India while providing a constitutional and social context as a backdrop. Particularly, secularism in the Indian Constitution is discussed alongside Article 44 provisions. The chapter then explores the issues predicted to arise in securing a uniform civil code, such as multiculturalism, fear of a Hindu Code, encroachment on freedom of religion, other preferred Indian approaches to religious issues, and the court’s role in securing the code. Further, it introduces possible models and the preferred model of establishing and implementing a uniform civil code, including such details as the church-state models, the elements of the uniform civil code, the gradual implementation of the code, and policy considerations.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| January 2023 | 9 |

| February 2023 | 1 |

| April 2023 | 8 |

| May 2023 | 8 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 5 |

| October 2023 | 3 |

| November 2023 | 8 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Increase Font Size

14 Uniform Civil Code

Debjani Chakravarthy

Introduction

Uniform Civil Code, a directive principle in the Indian Constitution has been the theme of one of the most intense, intriguing and widespread debate that emerged in India‘s public life right from the juncture that the constitution was adopted in 1950. You may have heard about the issue of Uniform Civil Code (henceforth, UCC) in the recent statements by the Jamiat-e-Ulama Hind (JUH) and All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) about how religious laws are a matter of religious freedom. A country with a secular constitution such as India is expected to uphold religious freedom as well as social justice. In this chapter we will learn about the UCC; its history and the debates surrounding its (non) implementation; the issue of gender and law in India—and the controversial question of how to balance religious and personal freedom as well as secularism and social justice.

Directive principles in the constitution are those provisions that are required to be taken into account by the state while making legislations, plans and policies. However these principles are non-justiciable, unlike fundamental rights, that is, if they are infringed in any way by the state, no judicial remedy is available to the citizens. In case of The Fundamental Rights embodied in Part III of the Constitution— encroachment of such rights are subject to judicial remedy. The rights of the citizen in the context of the directive principles may be exercised in an indirect way. The citizens are expected to treat the directive principles as yardsticks of a government‘s performance while expending their right to vote. The directive principle of UCC appears as Article 44 in the Indian constitution, advising the state to enact a uniform, undifferentiated set of civil laws throughout ‗the territory of India.‘ It reads:

The state shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.

The issue of UCC is closely tied to the operation of democracy in India, the formation of nationalist discourses, and the disavowed continuity of both these phenomena with the ideological and administrative apparatus of colonial rule. It also— as you will see— represents the interface of gender issues with democracy, citizenship and formal equality.

Section 1: The Legacy of Colonialism and the Civil Code

Colonialism is project and practice of domination—mostly by European/Western/White powers—of land, peoples, and cultures. Indian administrative and legal systems, as well as the idea of Indian democracy have been largely derived from the British Colonial State. This is not to suggest that this derivation or inheritance have been uncritical and uncontested. Cultures of anti-colonial resistance thrived in the British era and thrive today. The concept of colonialism has been expanded to include systems of domination that marginalize large sections of the population based on caste, gender, religion, sexuality, language, location – and other realities. Thus, the notion of intersectionality—of identities and politics—is essential to understand the evolution and issues surrounding the UCC. You can refer to the module on Intersectionality theory for a better understanding. UCC is not just a legal issue; it is a matter of intersecting identities and ideologies of gender, religion, and caste.

If you think that the UCC is a good idea, you might wonder why the provision on enacting one was placed as a directive principle and not a fundamental right. Tenets of Liberal democracy suggest that every citizen of a nation state must have equal legal rights. Yet in the Constitution, which lays down the terms of democracy in India, a distinction is made between rights in the public and rights at the private sphere. This distinction has been inherited from the colonial system and its lawmaking.

Colonial law first distinguished between criminal and civil law and placed laws regarding family practices, such as, marriage, divorce, adoption and inheritance within civil law. All laws other than family laws were universally applicable to all subjects. However, family laws were called personal laws and were codified according to religious tenets—a task entrusted to Hindu and Islamic religious authorities. The colonial state also drew a sharp distinction between the private and public sphere. In the former, structures of traditional religion and family life were allowed to remain without any state intervention (to stop any oppression of women and children). Interestingly, the colonial state used gender justice and women‘s issues as a reason to justify colonial rule.

For the public sphere, strict universal laws about trade/commerce, criminal offences, and ownership of property were instituted, so that civic and revenue administration becomes easier. The British state had also formed alliances with religious authorities (such as Brahmans/ Savarna castes) to facilitate indirect rule and social control. The notion of ―majority‖ and ―minority‖ for instance, is a framework of assessing Indian pluralism constructed during the colonial period and is a part of the dominant discourse of colonial modernity. This discourse assigns identities based on religion to various communities for the purposes of maintaining administrative order within a deeply heterogeneous empire. This approach undermines the vast diversity of society in India with its plurality of cultural practices— relegating it instead to a society of just a few contending religious groups.The British institutionalization of tribal identities follows the same logic. ―The definition of tribes as culturally distinct—from Hindu society as well as from one another—hinged on a catalog of cultural, racial and linguistic traits according to which they were labeled and classified. The anthropological gaze constructed the ‗tribes‘ as unitary, well-integrated, and timeless wholes, unpolluted by contact with the larger civilization until the advent of colonialism (Upadhya 2011, 268).‖ The question of tribes or tribal rights is rarely raised in the debate on UCC.

Thus the British colonial state divided the legal domain into Criminal and Civil, further dividing the ‗civil‘ into personal and fiscal laws. It codified personal laws with the help of religious authorities. Traditional family laws of Hinduism (like Mitakshara and Dayabhaga ) and Islam (Sharia laws derived from the Quran and the Hadith ) were unified and organized within codes. The state envisioned gender justice through passing of criminal laws prohibiting atrocious customary practices on women. However, the state was disinterested to reform the religious family laws which are often inequitable and unjust to women. This is related to the way in which colonialism differentiates the rights of individuals in public and private domain. Colonial ideology imposed on Indian society followed the logic of divide-and-rule.

So you can imagine how instead of eradicating social stratifications based on gender and caste, these divisions were carefully nurtured by the state to ensure status quo and prevent mass rebellion. This hands-free policy helped an initial commercial agency such as the East India Company to assume power over vast territories and colonize them substantively and epistemologically. Law as well as strengthening the hand of Brahmanism was a chief vehicle of this paternalistic control. There was constant effort towards standardizing law for the benefit of the newly introduced colonial juridical structure.The uniformity of colonial logichas left its indelible smear all over the Indian constitution and the debate over UCC.