- Marketing Mix Strategy

- Five Forces

- Business Lists

- Competitors

- Business Concepts

- Marketing and Strategy

Extensive Problem Solving

This article covers meaning, importance & example of Extensive Problem Solving from marketing perspective.

What is Extensive Problem Solving?

Extensive problem solving is the purchase decision marking in a situation in which the buyer has no information, experience about the products, services and suppliers. In extensive problem solving, lack of information also spreads to the brands for the product and also the criterion that they set for segregating the brands to be small or manageable subsets that help in the purchasing decision later. Consumers usually go for extensive problem solving when they discover that a need is completely new to them which requires significant effort to satisfy it.

The decision making process of a customer includes different levels of purchase decisions, i.e. extensive problem solving, limited problem solving and routinized choice behaviour.

Elements of Extensive Problem Solving

The various parameters which leads to extensive problem solving are:

1. Highly Priced Products: Like a car, house

2. Infrequent Purchases: Purchasing an automobile, HD TV

3. More Customer Participation: Purchasing a laptop with selection of RAM, ROM, display etc

4. Unfamiliar Product Category: Real-estate is a very unexplored category

5. Extensive Research & Time: Locality of buying house, proximity to hospital, station, market etc.

All these parameters or elements leads to extensive problem solving for the customer while taking a decision to make a purchase.

- Problem Recognition

- Problem Solution Approach

Importance of Extensive Problem Solving

It is very important for marketers to know the process that customers go through before purchasing. They cannot rely upon re-buys and word of mouth all the time for acquiring new customers. The customer in general goes through problem recognition, information search, evaluation, purchase decision and post-purchase evaluation. Closely related to a purchase decision is the problem solving phase. A new product with long term investment leads to extensive problem solving from a customer. This signifies that not all buying situations are same. A rebuy is very much different from a first choice purchase. The recognition that a brand enjoys in a customer’s mind helps the customer to make purchase decisions easily. If the brand has a dedicated marketing communication effort, whenever a consumer feels the need for a new product, they instantly go for it.

To help customers in extensive problem solving, companies must have clear transparent communication. It is thus very important for marketers to use a proper marketing mix so that they can have some cognition from their customers when they think of new products. With the advent of social media, the number of channels for promotion have hugely developed and they require a clear understanding on the segment of customer that each channel serves. The communication channels should lucidly differentiate themselves from other brands so that they are purchased quickly and easily.

Example of Extensive Problem Solving

Let us suppose, that Amber wants to buy a High Definition TV. The problem being, she has no idea regarding it. This is a case of extensive problem solving as the amount of information is low, the risk she is taking is high as she is going with the opinion that she gathers from her peers, the item is expensive and at the same time it also demands huge amount of involvement from the customer. Similarly, buying high price and long-term assets or products like car, motorcycle, house etc leads to extensive problem solving decision for the customers.

Hence, this concludes the definition of Extensive Problem Solving along with its overview.

This article has been researched & authored by the Business Concepts Team which comprises of MBA students, management professionals, and industry experts. It has been reviewed & published by the MBA Skool Team . The content on MBA Skool has been created for educational & academic purpose only.

Browse the definition and meaning of more similar terms. The Management Dictionary covers over 1800 business concepts from 5 categories.

Continue Reading:

- Sales Management

- Market Segmentation

- Brand Equity

- Positioning

- Selling Concept

- Marketing & Strategy Terms

- Human Resources (HR) Terms

- Operations & SCM Terms

- IT & Systems Terms

- Statistics Terms

What is MBA Skool? About Us

MBA Skool is a Knowledge Resource for Management Students, Aspirants & Professionals.

Business Courses

- Operations & SCM

- Human Resources

Quizzes & Skills

- Management Quizzes

- Skills Tests

Quizzes test your expertise in business and Skill tests evaluate your management traits

Related Content

- Marketing Strategy

- Inventory Costs

- Sales Quota

- Quality Control

- Training and Development

- Capacity Management

- Work Life Balance

- More Definitions

All Business Sections

- SWOT Analysis

- Marketing Mix & Strategy

- PESTLE Analysis

- Five Forces Analysis

- Top Brand Lists

Write for Us

- Submit Content

- Privacy Policy

- Contribute Content

- Web Stories

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Individual Consumer Decision Making

29 Consumer Decision Making Process

An organization that wants to be successful must consider buyer behavior when developing the marketing mix. Buyer behavior is the actions people take with regard to buying and using products. Marketers must understand buyer behavior, such as how raising or lowering a price will affect the buyer’s perception of the product and therefore create a fluctuation in sales, or how a specific review on social media can create an entirely new direction for the marketing mix based on the comments (buyer behavior/input) of the target market.

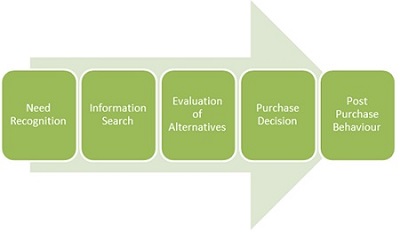

The Consumer Decision Making Process

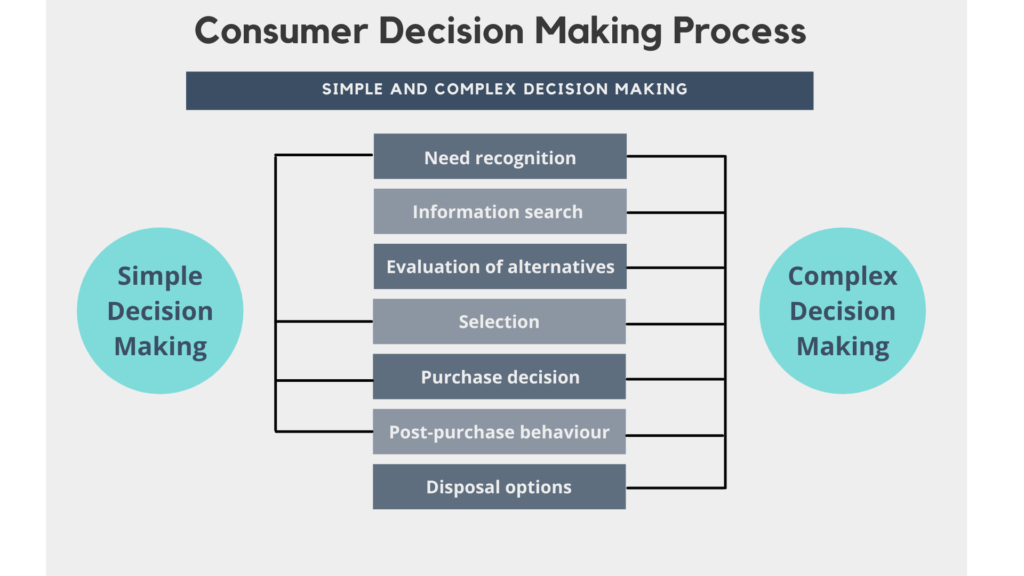

Once the process is started, a potential buyer can withdraw at any stage of making the actual purchase. The tendency for a person to go through all six stages is likely only in certain buying situations—a first time purchase of a product, for instance, or when buying high priced, long-lasting, infrequently purchased articles. This is referred to as complex decision making .

For many products, the purchasing behavior is a routine affair in which the aroused need is satisfied in a habitual manner by repurchasing the same brand. That is, past reinforcement in learning experiences leads directly to buying, and thus the second and third stages are bypassed. This is called simple decision making .

However, if something changes appreciably (price, product, availability, services), the buyer may re-enter the full decision process and consider alternative brands. Whether complex or simple, the first step is need identification (Assael, 1987).

When Inertia Takes Over

Need Recognition

Whether we act to resolve a particular problem depends upon two factors: (1) the magnitude of the discrepancy between what we have and what we need, and (2) the importance of the problem. A consumer may desire a new Cadillac and own a five-year-old Chevrolet. The discrepancy may be fairly large but relatively unimportant compared to the other problems they face. Conversely, an individual may own a car that is two years old and running very well. Yet, for various reasons, they may consider it extremely important to purchase a car this year. People must resolve these types of conflicts before they can proceed. Otherwise, the buying process for a given product stops at this point, probably in frustration.

Once the problem is recognized it must be defined in such a way that the consumer can actually initiate the action that will bring about a relevant problem solution. Note that, in many cases, problem recognition and problem definition occur simultaneously, such as a consumer running out of toothpaste. Consider the more complicated problem involved with status and image–how we want others to see us. For example, you may know that you are not satisfied with your appearance, but you may not be able to define it any more precisely than that. Consumers will not know where to begin solving their problem until the problem is adequately defined.

Marketers can become involved in the need recognition stage in three ways. First they need to know what problems consumers are facing in order to develop a marketing mix to help solve these problems. This requires that they measure problem recognition. Second, on occasion, marketers want to activate problem recognition. Public service announcements espousing the dangers of cigarette smoking is an example. Weekend and night shop hours are a response of retailers to the consumer problem of limited weekday shopping opportunities. This problem has become particularly important to families with two working adults. Finally, marketers can also shape the definition of the need or problem. If a consumer needs a new coat, do they define the problem as a need for inexpensive covering, a way to stay warm on the coldest days, a garment that will last several years, warm cover that will not attract odd looks from their peers, or an article of clothing that will express their personal sense of style? A salesperson or an ad may shape their answers

Information Search

After a need is recognized, the prospective consumer may seek information to help identify and evaluate alternative products, services, and outlets that will meet that need. Such information can come from family, friends, personal observation, or other sources, such as Consumer Reports, salespeople, or mass media. The promotional component of the marketers offering is aimed at providing information to assist the consumer in their problem solving process. In some cases, the consumer already has the needed information based on past purchasing and consumption experience. Bad experiences and lack of satisfaction can destroy repeat purchases. The consumer with a need for tires may look for information in the local newspaper or ask friends for recommendation. If they have bought tires before and was satisfied, they may go to the same dealer and buy the same brand.

Information search can also identify new needs. As a tire shopper looks for information, they may decide that the tires are not the real problem, that the need is for a new car. At this point, the perceived need may change triggering a new informational search. Information search involves mental as well as the physical activities that consumers must perform in order to make decisions and accomplish desired goals in the marketplace. It takes time, energy, money, and can often involve foregoing more desirable activities. The benefits of information search, however, can outweigh the costs. For example, engaging in a thorough information search may save money, improve quality of selection, or reduce risks. The Internet is a valuable information source.

Evaluation of Alternatives

After information is secured and processed, alternative products, services, and outlets are identified as viable options. The consumer evaluates these alternatives , and, if financially and psychologically able, makes a choice. The criteria used in evaluation varies from consumer to consumer just as the needs and information sources vary. One consumer may consider price most important while another puts more weight (importance) upon quality or convenience.

Using the ‘Rule of Thumb’

Consumers don’t have the time or desire to ponder endlessly about every purchase! Fortunately for us, heuristics , also described as shortcuts or mental “rules of thumb”, help us make decisions quickly and painlessly. Heuristics are especially important to draw on when we are faced with choosing among products in a category where we don’t see huge differences or if the outcome isn’t ‘do or die’.

Heuristics are helpful sets of rules that simplify the decision-making process by making it quick and easy for consumers.

Common Heuristics in Consumer Decision Making

- Save the most money: Many people follow a rule like, “I’ll buy the lowest-priced choice so that I spend the least money right now.” Using this heuristic means you don’t need to look beyond the price tag to make a decision. Wal-Mart built a retailing empire by pleasing consumers who follow this rule.

- You get what you pay for: Some consumers might use the opposite heuristic of saving the most money and instead follow a rule such as: “I’ll buy the more expensive product because higher price means better quality.” These consumers are influenced by advertisements alluding to exclusivity, quality, and uncompromising performance.

- Stich to the tried and true: Brand loyalty also simplifies the decision-making process because we buy the brand that we’ve always bought before. therefore, we don’t need to spend more time and effort on the decision. Advertising plays a critical role in creating brand loyalty. In a study of the market leaders in thirty product categories, 27 of the brands that were #1 in 1930 were still at the top over 50 years later (Stevesnson, 1988)! A well known brand name is a powerful heuristic .

- National pride: Consumers who select brands because they represent their own culture and country of origin are making decision based on ethnocentrism . Ethnocentric consumers are said to perceive their own culture or country’s goods as being superior to others’. Ethnocentrism can behave as both a stereotype and a type of heuristic for consumers who are quick to generalize and judge brands based on their country of origin.

- Visual cues: Consumers may also rely on visual cues represented in product and packaging design. Visual cues may include the colour of the brand or product or deeper beliefs that they have developed about the brand. For example, if brands claim to support sustainability and climate activism, consumers want to believe these to be true. Visual cues such as green design and neutral-coloured packaging that appears to be made of recycled materials play into consumers’ heuristics .

The search for alternatives and the methods used in the search are influenced by such factors as: (a) time and money costs; (b) how much information the consumer already has; (c) the amount of the perceived risk if a wrong selection is made; and (d) the consumer’s predisposition toward particular choices as influenced by the attitude of the individual toward choice behaviour. That is, there are individuals who find the selection process to be difficult and disturbing. For these people there is a tendency to keep the number of alternatives to a minimum, even if they have not gone through an extensive information search to find that their alternatives appear to be the very best. On the other hand, there are individuals who feel it necessary to collect a long list of alternatives. This tendency can appreciably slow down the decision-making function.

Consumer Evaluations Made Easier

The evaluation of alternatives often involves consumers drawing on their evoke, inept, and insert sets to help them in the decision making process.

The brands and products that consumers compare—their evoked set – represent the alternatives being considered by consumers during the problem-solving process. Sometimes known as a “consideration” set, the evoked set tends to be small relative to the total number of options available. When a consumer commits significant time to the comparative process and reviews price, warranties, terms and condition of sale and other features it is said that they are involved in extended problem solving. Unlike routine problem solving, extended or extensive problem solving comprises external research and the evaluation of alternatives. Whereas, routine problem solving is low-involvement, inexpensive, and has limited risk if purchased, extended problem solving justifies the additional effort with a high-priced or scarce product, service, or benefit (e.g., the purchase of a car). Likewise, consumers use extensive problem solving for infrequently purchased, expensive, high-risk, or new goods or services.

As opposed to the evoked set, a consumer’s inept set represent those brands that they would not given any consideration too. For a consumer who is shopping around for an electric vehicle, for example, they would not even remotely consider gas-guzzling vehicles like large SUVs.

The inert set represents those brands or products a consumer is aware of, but is indifferent to and doesn’t consider them either desirable or relevant enough to be among the evoke set. Marketers have an opportunity here to position their brands appropriately so consumers move these items from their insert to evoke set when evaluation alternatives.

The selection of an alternative, in many cases, will require additional evaluation. For example, a consumer may select a favorite brand and go to a convenient outlet to make a purchase. Upon arrival at the dealer, the consumer finds that the desired brand is out-of-stock. At this point, additional evaluation is needed to decide whether to wait until the product comes in, accept a substitute, or go to another outlet. The selection and evaluation phases of consumer problem solving are closely related and often run sequentially, with outlet selection influencing product evaluation, or product selection influencing outlet evaluation.

While many consumers would agree that choice is a good thing, there is such a thing as “too much choice” that inhibits the consumer decision making process. Consumer hyperchoice is a term used to describe purchasing situations that involve an excess of choice thus making selection for difficult for consumers. Dr. Sheena Iyengar studies consumer choice and collects data that supports the concept of consumer hyperchoice. In one of her studies, she put out jars of jam in a grocery store for shoppers to sample, with the intention to influence purchases. Dr. Iyengar discovered that when a fewer number of jam samples were provided to shoppers, more purchases were made. But when a large number of jam samples were set out, fewer purchases were made (Green, 2010). As it turns out, “more is less” when it comes to the selection process.

The Purchase Decision

After much searching and evaluating, or perhaps very little, consumers at some point have to decide whether they are going to buy.

Anything marketers can do to simplify purchasing will be attractive to buyers. This may include minimal clicks to online checkout; short wait times in line; and simplified payment options. When it comes to advertising marketers could also suggest the best size for a particular use, or the right wine to drink with a particular food. Sometimes several decision situations can be combined and marketed as one package. For example, travel agents often package travel tours with flight and hotel reservations.

To do a better marketing job at this stage of the buying process, a seller needs to know answers to many questions about consumers’ shopping behaviour. For instance, how much effort is the consumer willing to spend in shopping for the product? What factors influence when the consumer will actually purchase? Are there any conditions that would prohibit or delay purchase? Providing basic product, price, and location information through labels, advertising, personal selling, and public relations is an obvious starting point. Product sampling, coupons, and rebates may also provide an extra incentive to buy.

Actually determining how a consumer goes through the decision-making process is a difficult research task.

Post-Purchase Behaviour

All the behaviour determinants and the steps of the buying process up to this point are operative before or during the time a purchase is made. However, a consumer’s feelings and evaluations after the sale are also significant to a marketer, because they can influence repeat sales and also influence what the customer tells others about the product or brand.

Keeping the customer happy is what marketing is all about. Nevertheless, consumers typically experience some post-purchase anxiety after all but the most routine and inexpensive purchases. This anxiety reflects a phenomenon called cognitive dissonance . According to this theory, people strive for consistency among their cognitions (knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values). When there are inconsistencies, dissonance exists, which people will try to eliminate. In some cases, the consumer makes the decision to buy a particular brand already aware of dissonant elements. In other instances, dissonance is aroused by disturbing information that is received after the purchase. The marketer may take specific steps to reduce post-purchase dissonance. Advertising that stresses the many positive attributes or confirms the popularity of the product can be helpful. Providing personal reinforcement has proven effective with big-ticket items such as automobiles and major appliances. Salespeople in these areas may send cards or may even make personal calls in order to reassure customers about their purchase.

Media Attributions

- The graphic of the “Consumer Decision Making Process” by Niosi, A. (2021) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA and is adapted from Introduction to Business by Rice University.

Text Attributions

- The sections under the “Consumer Decision Making Process,” “Need Recognition” (edited), “Information Search,” “Evaluation of Alternatives”; the first paragraph under the section “Selection”; the section under “Purchase Decision”; and, the section under “Post-Purchase Behaviour” are adapted from Introducing Marketing [PDF] by John Burnett which is licensed under CC BY 3.0 .

- The opening paragraph and the image of the Consumer Decision Making Process is adapted from Introduction to Business by Rice University which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- The section under “Using the ‘Rule of Thumb'” is adapted (and edited) from Launch! Advertising and Promotion in Real Time [PDF] by Saylor Academy which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

Assael, H. (1987). Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action (3rd ed.), 84. Boston: Kent Publishing.

Green, P. (2010, March 17). An Expert on Choice Chooses. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/18/garden/18choice.html.

Consumer purchases made when a (new) need is identified and a consumer engages in a more rigorous evaluation, research, and alternative assessment process before satisfying the unmet need.

Consumer purchases made when a need is identified and a habitual ("routine") purchase is made to satisfy that need.

Purchasing decisions made out of habit.

The first stage of the Consumer Decision Making Process, need recognition takes place when a consumer identifies an unmet need.

The second stage of the Consumer Decision Making Process, information search takes place when a consumer seeks relative information that will help them identify and evaluate alternatives before deciding on the final purchase decision.

The third stage of the Consumer Decision Making Process, the evaluation of alternatives takes place when a consumer establishes criteria to evaluate the most viable purchasing option.

Also known as "mental shortcuts" or "rules of thumb", heuristics help consumers by simplifying the decision-making process.

A small set of "go-to" brands that consumers will consider as they evaluate the alternatives available to them before making a purchasing decision.

The brands a consumer would not pay any attention to during the evaluation of alternatives process.

The brands a consumer is aware of but indifferent to, when evaluating alternatives in the consumer decision making process. The consumer may deem these brands irrelevant and will therefore exclude them from any extensive evaluation or consideration.

A term that describes a purchasing situation in which a consumer is faced with an excess of choice that makes decision making difficult or nearly impossible.

A type of cognitive inconsistency, this term describes the discomfort consumers may feel when their beliefs, values, attitudes, or perceptions are inconsistent or contradictory to their original belief or understanding. Consumers with cognitive dissonance related to a purchasing decision will often seek to resolve this internal turmoil they are experiencing by returning the product or finding a way to justify it and minimizing their sense of buyer's remorse.

Introduction to Consumer Behaviour Copyright © 2021 by Andrea Niosi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

What is Problem Solving? (Steps, Techniques, Examples)

What is problem solving, definition and importance.

Problem solving is the process of finding solutions to obstacles or challenges you encounter in your life or work. It is a crucial skill that allows you to tackle complex situations, adapt to changes, and overcome difficulties with ease. Mastering this ability will contribute to both your personal and professional growth, leading to more successful outcomes and better decision-making.

Problem-Solving Steps

The problem-solving process typically includes the following steps:

- Identify the issue : Recognize the problem that needs to be solved.

- Analyze the situation : Examine the issue in depth, gather all relevant information, and consider any limitations or constraints that may be present.

- Generate potential solutions : Brainstorm a list of possible solutions to the issue, without immediately judging or evaluating them.

- Evaluate options : Weigh the pros and cons of each potential solution, considering factors such as feasibility, effectiveness, and potential risks.

- Select the best solution : Choose the option that best addresses the problem and aligns with your objectives.

- Implement the solution : Put the selected solution into action and monitor the results to ensure it resolves the issue.

- Review and learn : Reflect on the problem-solving process, identify any improvements or adjustments that can be made, and apply these learnings to future situations.

Defining the Problem

To start tackling a problem, first, identify and understand it. Analyzing the issue thoroughly helps to clarify its scope and nature. Ask questions to gather information and consider the problem from various angles. Some strategies to define the problem include:

- Brainstorming with others

- Asking the 5 Ws and 1 H (Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How)

- Analyzing cause and effect

- Creating a problem statement

Generating Solutions

Once the problem is clearly understood, brainstorm possible solutions. Think creatively and keep an open mind, as well as considering lessons from past experiences. Consider:

- Creating a list of potential ideas to solve the problem

- Grouping and categorizing similar solutions

- Prioritizing potential solutions based on feasibility, cost, and resources required

- Involving others to share diverse opinions and inputs

Evaluating and Selecting Solutions

Evaluate each potential solution, weighing its pros and cons. To facilitate decision-making, use techniques such as:

- SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats)

- Decision-making matrices

- Pros and cons lists

- Risk assessments

After evaluating, choose the most suitable solution based on effectiveness, cost, and time constraints.

Implementing and Monitoring the Solution

Implement the chosen solution and monitor its progress. Key actions include:

- Communicating the solution to relevant parties

- Setting timelines and milestones

- Assigning tasks and responsibilities

- Monitoring the solution and making adjustments as necessary

- Evaluating the effectiveness of the solution after implementation

Utilize feedback from stakeholders and consider potential improvements. Remember that problem-solving is an ongoing process that can always be refined and enhanced.

Problem-Solving Techniques

During each step, you may find it helpful to utilize various problem-solving techniques, such as:

- Brainstorming : A free-flowing, open-minded session where ideas are generated and listed without judgment, to encourage creativity and innovative thinking.

- Root cause analysis : A method that explores the underlying causes of a problem to find the most effective solution rather than addressing superficial symptoms.

- SWOT analysis : A tool used to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to a problem or decision, providing a comprehensive view of the situation.

- Mind mapping : A visual technique that uses diagrams to organize and connect ideas, helping to identify patterns, relationships, and possible solutions.

Brainstorming

When facing a problem, start by conducting a brainstorming session. Gather your team and encourage an open discussion where everyone contributes ideas, no matter how outlandish they may seem. This helps you:

- Generate a diverse range of solutions

- Encourage all team members to participate

- Foster creative thinking

When brainstorming, remember to:

- Reserve judgment until the session is over

- Encourage wild ideas

- Combine and improve upon ideas

Root Cause Analysis

For effective problem-solving, identifying the root cause of the issue at hand is crucial. Try these methods:

- 5 Whys : Ask “why” five times to get to the underlying cause.

- Fishbone Diagram : Create a diagram representing the problem and break it down into categories of potential causes.

- Pareto Analysis : Determine the few most significant causes underlying the majority of problems.

SWOT Analysis

SWOT analysis helps you examine the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats related to your problem. To perform a SWOT analysis:

- List your problem’s strengths, such as relevant resources or strong partnerships.

- Identify its weaknesses, such as knowledge gaps or limited resources.

- Explore opportunities, like trends or new technologies, that could help solve the problem.

- Recognize potential threats, like competition or regulatory barriers.

SWOT analysis aids in understanding the internal and external factors affecting the problem, which can help guide your solution.

Mind Mapping

A mind map is a visual representation of your problem and potential solutions. It enables you to organize information in a structured and intuitive manner. To create a mind map:

- Write the problem in the center of a blank page.

- Draw branches from the central problem to related sub-problems or contributing factors.

- Add more branches to represent potential solutions or further ideas.

Mind mapping allows you to visually see connections between ideas and promotes creativity in problem-solving.

Examples of Problem Solving in Various Contexts

In the business world, you might encounter problems related to finances, operations, or communication. Applying problem-solving skills in these situations could look like:

- Identifying areas of improvement in your company’s financial performance and implementing cost-saving measures

- Resolving internal conflicts among team members by listening and understanding different perspectives, then proposing and negotiating solutions

- Streamlining a process for better productivity by removing redundancies, automating tasks, or re-allocating resources

In educational contexts, problem-solving can be seen in various aspects, such as:

- Addressing a gap in students’ understanding by employing diverse teaching methods to cater to different learning styles

- Developing a strategy for successful time management to balance academic responsibilities and extracurricular activities

- Seeking resources and support to provide equal opportunities for learners with special needs or disabilities

Everyday life is full of challenges that require problem-solving skills. Some examples include:

- Overcoming a personal obstacle, such as improving your fitness level, by establishing achievable goals, measuring progress, and adjusting your approach accordingly

- Navigating a new environment or city by researching your surroundings, asking for directions, or using technology like GPS to guide you

- Dealing with a sudden change, like a change in your work schedule, by assessing the situation, identifying potential impacts, and adapting your plans to accommodate the change.

- How to Resolve Employee Conflict at Work [Steps, Tips, Examples]

- How to Write Inspiring Core Values? 5 Steps with Examples

- 30 Employee Feedback Examples (Positive & Negative)

Extensive Problem Solving

In the choice process, extensive problem solving includes those consumer decisions requiring considerable cognitive activity, thought, and behavioral effort as compared to routinized choice behavior and habitual decision making . [1]

This type of decision making is usually associated with high-involvement purchases and when the customer has limited experience with the product category. [2]

- ^ American Marketing Association. AMA Dictionary.

- ^ Govoni, N.A. Dictionary of Marketing Communications, Sage Publications, (2004)

Comments are closed.

- Book a Demo

Struggling to overcome challenges in your life? We all face problems, big and small, on a regular basis.

So how do you tackle them effectively? What are some key problem-solving strategies and skills that can guide you?

Effective problem-solving requires breaking issues down logically, generating solutions creatively, weighing choices critically, and adapting plans flexibly based on outcomes. Useful strategies range from leveraging past solutions that have worked to visualizing problems through diagrams. Core skills include analytical abilities, innovative thinking, and collaboration.

Want to improve your problem-solving skills? Keep reading to find out 17 effective problem-solving strategies, key skills, common obstacles to watch for, and tips on improving your overall problem-solving skills.

Key Takeaways:

- Effective problem-solving requires breaking down issues logically, generating multiple solutions creatively, weighing choices critically, and adapting plans based on outcomes.

- Useful problem-solving strategies range from leveraging past solutions to brainstorming with groups to visualizing problems through diagrams and models.

- Core skills include analytical abilities, innovative thinking, decision-making, and team collaboration to solve problems.

- Common obstacles include fear of failure, information gaps, fixed mindsets, confirmation bias, and groupthink.

- Boosting problem-solving skills involves learning from experts, actively practicing, soliciting feedback, and analyzing others’ success.

- Onethread’s project management capabilities align with effective problem-solving tenets – facilitating structured solutions, tracking progress, and capturing lessons learned.

What Is Problem-Solving?

Problem-solving is the process of understanding an issue, situation, or challenge that needs to be addressed and then systematically working through possible solutions to arrive at the best outcome.

It involves critical thinking, analysis, logic, creativity, research, planning, reflection, and patience in order to overcome obstacles and find effective answers to complex questions or problems.

The ultimate goal is to implement the chosen solution successfully.

What Are Problem-Solving Strategies?

Problem-solving strategies are like frameworks or methodologies that help us solve tricky puzzles or problems we face in the workplace, at home, or with friends.

Imagine you have a big jigsaw puzzle. One strategy might be to start with the corner pieces. Another could be looking for pieces with the same colors.

Just like in puzzles, in real life, we use different plans or steps to find solutions to problems. These strategies help us think clearly, make good choices, and find the best answers without getting too stressed or giving up.

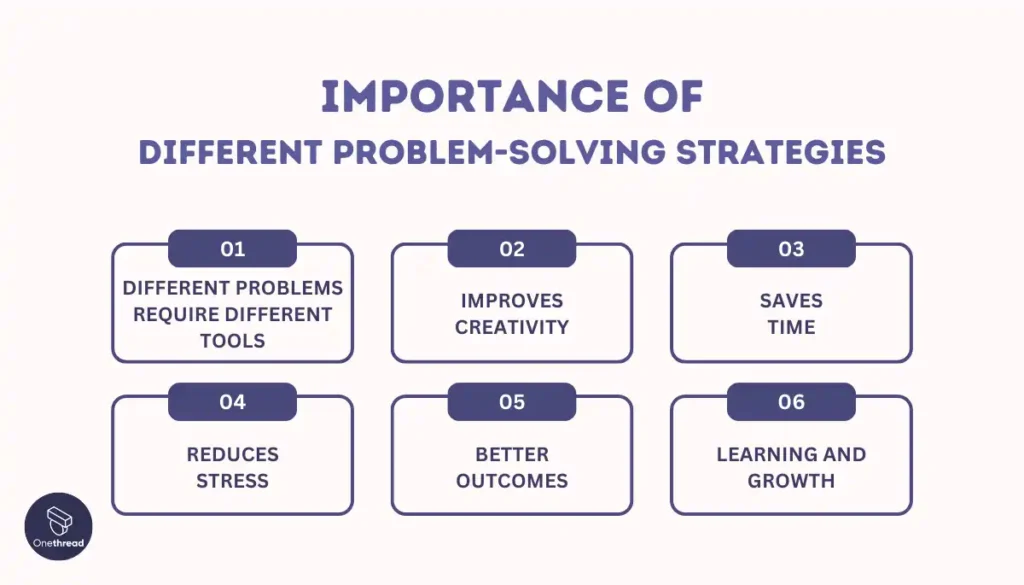

Why Is It Important To Know Different Problem-Solving Strategies?

Knowing different problem-solving strategies is important because different types of problems often require different approaches to solve them effectively. Having a variety of strategies to choose from allows you to select the best method for the specific problem you are trying to solve.

This improves your ability to analyze issues thoroughly, develop solutions creatively, and tackle problems from multiple angles. Knowing multiple strategies also aids in overcoming roadblocks if your initial approach is not working.

Here are some reasons why you need to know different problem-solving strategies:

- Different Problems Require Different Tools: Just like you can’t use a hammer to fix everything, some problems need specific strategies to solve them.

- Improves Creativity: Knowing various strategies helps you think outside the box and come up with creative solutions.

- Saves Time: With the right strategy, you can solve problems faster instead of trying things that don’t work.

- Reduces Stress: When you know how to tackle a problem, it feels less scary and you feel more confident.

- Better Outcomes: Using the right strategy can lead to better solutions, making things work out better in the end.

- Learning and Growth: Each time you solve a problem, you learn something new, which makes you smarter and better at solving future problems.

Knowing different ways to solve problems helps you tackle anything that comes your way, making life a bit easier and more fun!

17 Effective Problem-Solving Strategies

Effective problem-solving strategies include breaking the problem into smaller parts, brainstorming multiple solutions, evaluating the pros and cons of each, and choosing the most viable option.

Critical thinking and creativity are essential in developing innovative solutions. Collaboration with others can also provide diverse perspectives and ideas.

By applying these strategies, you can tackle complex issues more effectively.

Now, consider a challenge you’re dealing with. Which strategy could help you find a solution? Here we will discuss key problem strategies in detail.

1. Use a Past Solution That Worked

This strategy involves looking back at previous similar problems you have faced and the solutions that were effective in solving them.

It is useful when you are facing a problem that is very similar to something you have already solved. The main benefit is that you don’t have to come up with a brand new solution – you already know the method that worked before will likely work again.

However, the limitation is that the current problem may have some unique aspects or differences that mean your old solution is not fully applicable.

The ideal process is to thoroughly analyze the new challenge, identify the key similarities and differences versus the past case, adapt the old solution as needed to align with the current context, and then pilot it carefully before full implementation.

An example is using the same negotiation tactics from purchasing your previous home when putting in an offer on a new house. Key terms would be adjusted but overall it can save significant time versus developing a brand new strategy.

2. Brainstorm Solutions

This involves gathering a group of people together to generate as many potential solutions to a problem as possible.

It is effective when you need creative ideas to solve a complex or challenging issue. By getting input from multiple people with diverse perspectives, you increase the likelihood of finding an innovative solution.

The main limitation is that brainstorming sessions can sometimes turn into unproductive gripe sessions or discussions rather than focusing on productive ideation —so they need to be properly facilitated.

The key to an effective brainstorming session is setting some basic ground rules upfront and having an experienced facilitator guide the discussion. Rules often include encouraging wild ideas, avoiding criticism of ideas during the ideation phase, and building on others’ ideas.

For instance, a struggling startup might hold a session where ideas for turnaround plans are generated and then formalized with financials and metrics.

3. Work Backward from the Solution

This technique involves envisioning that the problem has already been solved and then working step-by-step backward toward the current state.

This strategy is particularly helpful for long-term, multi-step problems. By starting from the imagined solution and identifying all the steps required to reach it, you can systematically determine the actions needed. It lets you tackle a big hairy problem through smaller, reversible steps.

A limitation is that this approach may not be possible if you cannot accurately envision the solution state to start with.

The approach helps drive logical systematic thinking for complex problem-solving, but should still be combined with creative brainstorming of alternative scenarios and solutions.

An example is planning for an event – you would imagine the successful event occurring, then determine the tasks needed the week before, two weeks before, etc. all the way back to the present.

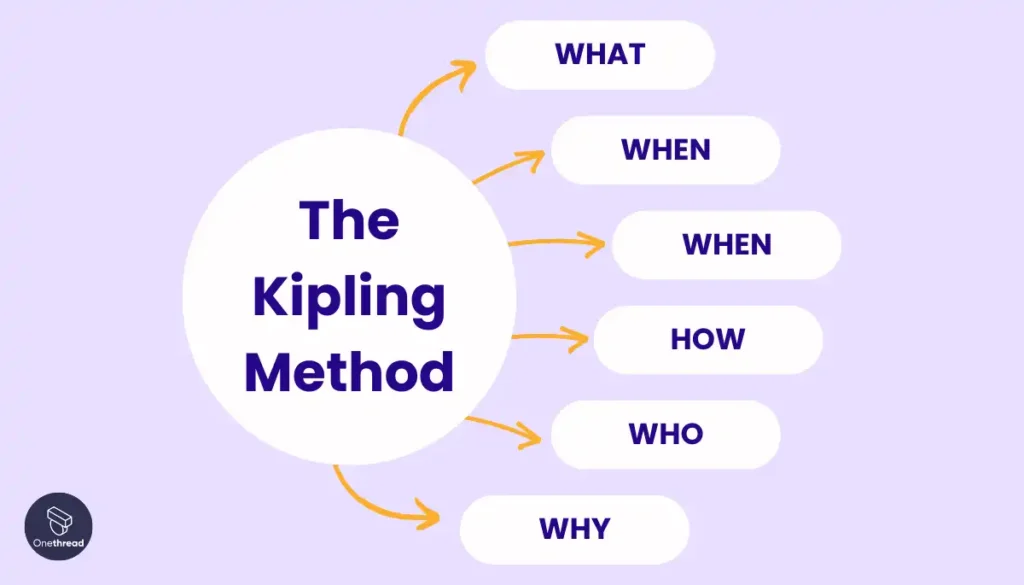

4. Use the Kipling Method

This method, named after author Rudyard Kipling, provides a framework for thoroughly analyzing a problem before jumping into solutions.

It consists of answering six fundamental questions: What, Where, When, How, Who, and Why about the challenge. Clearly defining these core elements of the problem sets the stage for generating targeted solutions.

The Kipling method enables a deep understanding of problem parameters and root causes before solution identification. By jumping to brainstorm solutions too early, critical information can be missed or the problem is loosely defined, reducing solution quality.

Answering the six fundamental questions illuminates all angles of the issue. This takes time but pays dividends in generating optimal solutions later tuned precisely to the true underlying problem.

The limitation is that meticulously working through numerous questions before addressing solutions can slow progress.

The best approach blends structured problem decomposition techniques like the Kipling method with spurring innovative solution ideation from a diverse team.

An example is using this technique after a technical process failure – the team would systematically detail What failed, Where/When did it fail, How it failed (sequence of events), Who was involved, and Why it likely failed before exploring preventative solutions.

5. Try Different Solutions Until One Works (Trial and Error)

This technique involves attempting various potential solutions sequentially until finding one that successfully solves the problem.

Trial and error works best when facing a concrete, bounded challenge with clear solution criteria and a small number of discrete options to try. By methodically testing solutions, you can determine the faulty component.

A limitation is that it can be time-intensive if the working solution set is large.

The key is limiting the variable set first. For technical problems, this boundary is inherent and each element can be iteratively tested. But for business issues, artificial constraints may be required – setting decision rules upfront to reduce options before testing.

Furthermore, hypothesis-driven experimentation is far superior to blind trial and error – have logic for why Option A may outperform Option B.

Examples include fixing printer jams by testing different paper tray and cable configurations or resolving website errors by tweaking CSS/HTML line-by-line until the code functions properly.

6. Use Proven Formulas or Frameworks (Heuristics)

Heuristics refers to applying existing problem-solving formulas or frameworks rather than addressing issues completely from scratch.

This allows leveraging established best practices rather than reinventing the wheel each time.

It is effective when facing recurrent, common challenges where proven structured approaches exist.

However, heuristics may force-fit solutions to non-standard problems.

For example, a cost-benefit analysis can be used instead of custom weighting schemes to analyze potential process improvements.

Onethread allows teams to define, save, and replicate configurable project templates so proven workflows can be reliably applied across problems with some consistency rather than fully custom one-off approaches each time.

Try One thread

Experience One thread full potential, with all its features unlocked. Sign up now to start your 14-day free trial!

7. Trust Your Instincts (Insight Problem-Solving)

Insight is a problem-solving technique that involves waiting patiently for an unexpected “aha moment” when the solution pops into your mind.

It works well for personal challenges that require intuitive realizations over calculated logic. The unconscious mind makes connections leading to flashes of insight when relaxing or doing mundane tasks unrelated to the actual problem.

Benefits include out-of-the-box creative solutions. However, the limitations are that insights can’t be forced and may never come at all if too complex. Critical analysis is still required after initial insights.

A real-life example would be a writer struggling with how to end a novel. Despite extensive brainstorming, they feel stuck. Eventually while gardening one day, a perfect unexpected plot twist sparks an ideal conclusion. However, once written they still carefully review if the ending flows logically from the rest of the story.

8. Reverse Engineer the Problem

This approach involves deconstructing a problem in reverse sequential order from the current undesirable outcome back to the initial root causes.

By mapping the chain of events backward, you can identify the origin of where things went wrong and establish the critical junctures for solving it moving ahead. Reverse engineering provides diagnostic clarity on multi-step problems.

However, the limitation is that it focuses heavily on autopsying the past versus innovating improved future solutions.

An example is tracing back from a server outage, through the cascade of infrastructure failures that led to it finally terminating at the initial script error that triggered the crisis. This root cause would then inform the preventative measure.

9. Break Down Obstacles Between Current and Goal State (Means-End Analysis)

This technique defines the current problem state and the desired end goal state, then systematically identifies obstacles in the way of getting from one to the other.

By mapping the barriers or gaps, you can then develop solutions to address each one. This methodically connects the problem to solutions.

A limitation is that some obstacles may be unknown upfront and only emerge later.

For example, you can list down all the steps required for a new product launch – current state through production, marketing, sales, distribution, etc. to full launch (goal state) – to highlight where resource constraints or other blocks exist so they can be addressed.

Onethread allows dividing big-picture projects into discrete, manageable phases, milestones, and tasks to simplify execution just as problems can be decomposed into more achievable components. Features like dependency mapping further reinforce interconnections.

Using Onethread’s issues and subtasks feature, messy problems can be decomposed into manageable chunks.

10. Ask “Why” Five Times to Identify the Root Cause (The 5 Whys)

This technique involves asking “Why did this problem occur?” and then responding with an answer that is again met with asking “Why?” This process repeats five times until the root cause is revealed.

Continually asking why digs deeper from surface symptoms to underlying systemic issues.

It is effective for getting to the source of problems originating from human error or process breakdowns.

However, some complex issues may have multiple tangled root causes not solvable through this approach alone.

An example is a retail store experiencing a sudden decline in customers. Successively asking why five times may trace an initial drop to parking challenges, stemming from a city construction project – the true starting point to address.

11. Evaluate Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT Analysis)

This involves analyzing a problem or proposed solution by categorizing internal and external factors into a 2×2 matrix: Strengths, Weaknesses as the internal rows; Opportunities and Threats as the external columns.

Systematically identifying these elements provides balanced insight to evaluate options and risks. It is impactful when evaluating alternative solutions or developing strategy amid complexity or uncertainty.

The key benefit of SWOT analysis is enabling multi-dimensional thinking when rationally evaluating options. Rather than getting anchored on just the upsides or the existing way of operating, it urges a systematic assessment through four different lenses:

- Internal Strengths: Our core competencies/advantages able to deliver success

- Internal Weaknesses: Gaps/vulnerabilities we need to manage

- External Opportunities: Ways we can differentiate/drive additional value

- External Threats: Risks we must navigate or mitigate

Multiperspective analysis provides the needed holistic view of the balanced risk vs. reward equation for strategic decision making amid uncertainty.

However, SWOT can feel restrictive if not tailored and evolved for different issue types.

Teams should view SWOT analysis as a starting point, augmenting it further for distinct scenarios.

An example is performing a SWOT analysis on whether a small business should expand into a new market – evaluating internal capabilities to execute vs. risks in the external competitive and demand environment to inform the growth decision with eyes wide open.

12. Compare Current vs Expected Performance (Gap Analysis)

This technique involves comparing the current state of performance, output, or results to the desired or expected levels to highlight shortfalls.

By quantifying the gaps, you can identify problem areas and prioritize address solutions.

Gap analysis is based on the simple principle – “you can’t improve what you don’t measure.” It enables facts-driven problem diagnosis by highlighting delta to goals, not just vague dissatisfaction that something seems wrong. And measurement immediately suggests improvement opportunities – address the biggest gaps first.

This data orientation also supports ROI analysis on fixing issues – the return from closing larger gaps outweighs narrowly targeting smaller performance deficiencies.

However, the approach is only effective if robust standards and metrics exist as the benchmark to evaluate against. Organizations should invest upfront in establishing performance frameworks.

Furthermore, while numbers are invaluable, the human context behind problems should not be ignored – quantitative versus qualitative gap assessment is optimally blended.

For example, if usage declines are noted during software gap analysis, this could be used as a signal to improve user experience through design.

13. Observe Processes from the Frontline (Gemba Walk)

A Gemba walk involves going to the actual place where work is done, directly observing the process, engaging with employees, and finding areas for improvement.

By experiencing firsthand rather than solely reviewing abstract reports, practical problems and ideas emerge.

The limitation is Gemba walks provide anecdotes not statistically significant data. It complements but does not replace comprehensive performance measurement.

An example is a factory manager inspecting the production line to spot jam areas based on direct reality rather than relying on throughput dashboards alone back in her office. Frontline insights prove invaluable.

14. Analyze Competitive Forces (Porter’s Five Forces)

This involves assessing the marketplace around a problem or business situation via five key factors: competitors, new entrants, substitute offerings, suppliers, and customer power.

Evaluating these forces illuminates risks and opportunities for strategy development and issue resolution. It is effective for understanding dynamic external threats and opportunities when operating in a contested space.

However, over-indexing on only external factors can overlook the internal capabilities needed to execute solutions.

A startup CEO, for example, may analyze market entry barriers, whitespace opportunities, and disruption risks across these five forces to shape new product rollout strategies and marketing approaches.

15. Think from Different Perspectives (Six Thinking Hats)

The Six Thinking Hats is a technique developed by Edward de Bono that encourages people to think about a problem from six different perspectives, each represented by a colored “thinking hat.”

The key benefit of this strategy is that it pushes team members to move outside their usual thinking style and consider new angles. This brings more diverse ideas and solutions to the table.

It works best for complex problems that require innovative solutions and when a team is stuck in an unproductive debate. The structured framework keeps the conversation flowing in a positive direction.

Limitations are that it requires training on the method itself and may feel unnatural at first. Team dynamics can also influence success – some members may dominate certain “hats” while others remain quiet.

A real-life example is a software company debating whether to build a new feature. The white hat focuses on facts, red on gut feelings, black on potential risks, yellow on benefits, green on new ideas, and blue on process. This exposes more balanced perspectives before deciding.

Onethread centralizes diverse stakeholder communication onto one platform, ensuring all voices are incorporated when evaluating project tradeoffs, just as problem-solving should consider multifaceted solutions.

16. Visualize the Problem (Draw it Out)

Drawing out a problem involves creating visual representations like diagrams, flowcharts, and maps to work through challenging issues.

This strategy is helpful when dealing with complex situations with lots of interconnected components. The visuals simplify the complexity so you can thoroughly understand the problem and all its nuances.

Key benefits are that it allows more stakeholders to get on the same page regarding root causes and it sparks new creative solutions as connections are made visually.

However, simple problems with few variables don’t require extensive diagrams. Additionally, some challenges are so multidimensional that fully capturing every aspect is difficult.

A real-life example would be mapping out all the possible causes leading to decreased client satisfaction at a law firm. An intricate fishbone diagram with branches for issues like service delivery, technology, facilities, culture, and vendor partnerships allows the team to trace problems back to their origins and brainstorm targeted fixes.

17. Follow a Step-by-Step Procedure (Algorithms)

An algorithm is a predefined step-by-step process that is guaranteed to produce the correct solution if implemented properly.

Using algorithms is effective when facing problems that have clear, binary right and wrong answers. Algorithms work for mathematical calculations, computer code, manufacturing assembly lines, and scientific experiments.

Key benefits are consistency, accuracy, and efficiency. However, they require extensive upfront development and only apply to scenarios with strict parameters. Additionally, human error can lead to mistakes.

For example, crew members of fast food chains like McDonald’s follow specific algorithms for food prep – from grill times to ingredient amounts in sandwiches, to order fulfillment procedures. This ensures uniform quality and service across all locations. However, if a step is missed, errors occur.

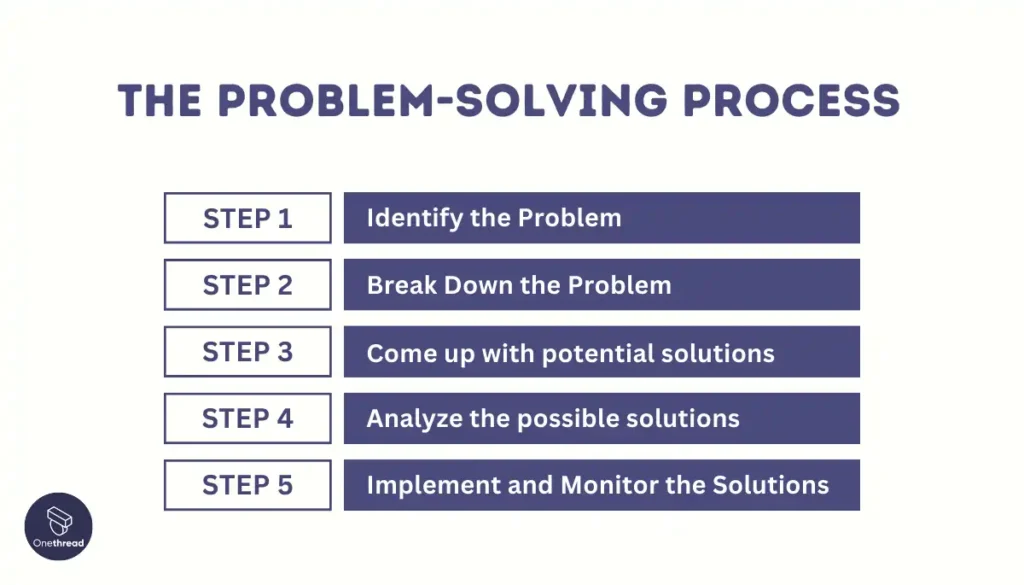

The Problem-Solving Process

The problem-solving process typically includes defining the issue, analyzing details, creating solutions, weighing choices, acting, and reviewing results.

In the above, we have discussed several problem-solving strategies. For every problem-solving strategy, you have to follow these processes. Here’s a detailed step-by-step process of effective problem-solving:

Step 1: Identify the Problem

The problem-solving process starts with identifying the problem. This step involves understanding the issue’s nature, its scope, and its impact. Once the problem is clearly defined, it sets the foundation for finding effective solutions.

Identifying the problem is crucial. It means figuring out exactly what needs fixing. This involves looking at the situation closely, understanding what’s wrong, and knowing how it affects things. It’s about asking the right questions to get a clear picture of the issue.

This step is important because it guides the rest of the problem-solving process. Without a clear understanding of the problem, finding a solution is much harder. It’s like diagnosing an illness before treating it. Once the problem is identified accurately, you can move on to exploring possible solutions and deciding on the best course of action.

Step 2: Break Down the Problem

Breaking down the problem is a key step in the problem-solving process. It involves dividing the main issue into smaller, more manageable parts. This makes it easier to understand and tackle each component one by one.

After identifying the problem, the next step is to break it down. This means splitting the big issue into smaller pieces. It’s like solving a puzzle by handling one piece at a time.

By doing this, you can focus on each part without feeling overwhelmed. It also helps in identifying the root causes of the problem. Breaking down the problem allows for a clearer analysis and makes finding solutions more straightforward.

Each smaller problem can be addressed individually, leading to an effective resolution of the overall issue. This approach not only simplifies complex problems but also aids in developing a systematic plan to solve them.

Step 3: Come up with potential solutions

Coming up with potential solutions is the third step in the problem-solving process. It involves brainstorming various options to address the problem, considering creativity and feasibility to find the best approach.

After breaking down the problem, it’s time to think of ways to solve it. This stage is about brainstorming different solutions. You look at the smaller issues you’ve identified and start thinking of ways to fix them. This is where creativity comes in.

You want to come up with as many ideas as possible, no matter how out-of-the-box they seem. It’s important to consider all options and evaluate their pros and cons. This process allows you to gather a range of possible solutions.

Later, you can narrow these down to the most practical and effective ones. This step is crucial because it sets the stage for deciding on the best solution to implement. It’s about being open-minded and innovative to tackle the problem effectively.

Step 4: Analyze the possible solutions

Analyzing the possible solutions is the fourth step in the problem-solving process. It involves evaluating each proposed solution’s advantages and disadvantages to determine the most effective and feasible option.

After coming up with potential solutions, the next step is to analyze them. This means looking closely at each idea to see how well it solves the problem. You weigh the pros and cons of every solution.

Consider factors like cost, time, resources, and potential outcomes. This analysis helps in understanding the implications of each option. It’s about being critical and objective, ensuring that the chosen solution is not only effective but also practical.

This step is vital because it guides you towards making an informed decision. It involves comparing the solutions against each other and selecting the one that best addresses the problem.

By thoroughly analyzing the options, you can move forward with confidence, knowing you’ve chosen the best path to solve the issue.

Step 5: Implement and Monitor the Solutions

Implementing and monitoring the solutions is the final step in the problem-solving process. It involves putting the chosen solution into action and observing its effectiveness, making adjustments as necessary.

Once you’ve selected the best solution, it’s time to put it into practice. This step is about action. You implement the chosen solution and then keep an eye on how it works. Monitoring is crucial because it tells you if the solution is solving the problem as expected.

If things don’t go as planned, you may need to make some changes. This could mean tweaking the current solution or trying a different one. The goal is to ensure the problem is fully resolved.

This step is critical because it involves real-world application. It’s not just about planning; it’s about doing and adjusting based on results. By effectively implementing and monitoring the solutions, you can achieve the desired outcome and solve the problem successfully.

Why This Process is Important

Following a defined process to solve problems is important because it provides a systematic, structured approach instead of a haphazard one. Having clear steps guides logical thinking, analysis, and decision-making to increase effectiveness. Key reasons it helps are:

- Clear Direction: This process gives you a clear path to follow, which can make solving problems less overwhelming.

- Better Solutions: Thoughtful analysis of root causes, iterative testing of solutions, and learning orientation lead to addressing the heart of issues rather than just symptoms.

- Saves Time and Energy: Instead of guessing or trying random things, this process helps you find a solution more efficiently.

- Improves Skills: The more you use this process, the better you get at solving problems. It’s like practicing a sport. The more you practice, the better you play.

- Maximizes collaboration: Involving various stakeholders in the process enables broader inputs. Their communication and coordination are streamlined through organized brainstorming and evaluation.

- Provides consistency: Standard methodology across problems enables building institutional problem-solving capabilities over time. Patterns emerge on effective techniques to apply to different situations.

The problem-solving process is a powerful tool that can help us tackle any challenge we face. By following these steps, we can find solutions that work and learn important skills along the way.

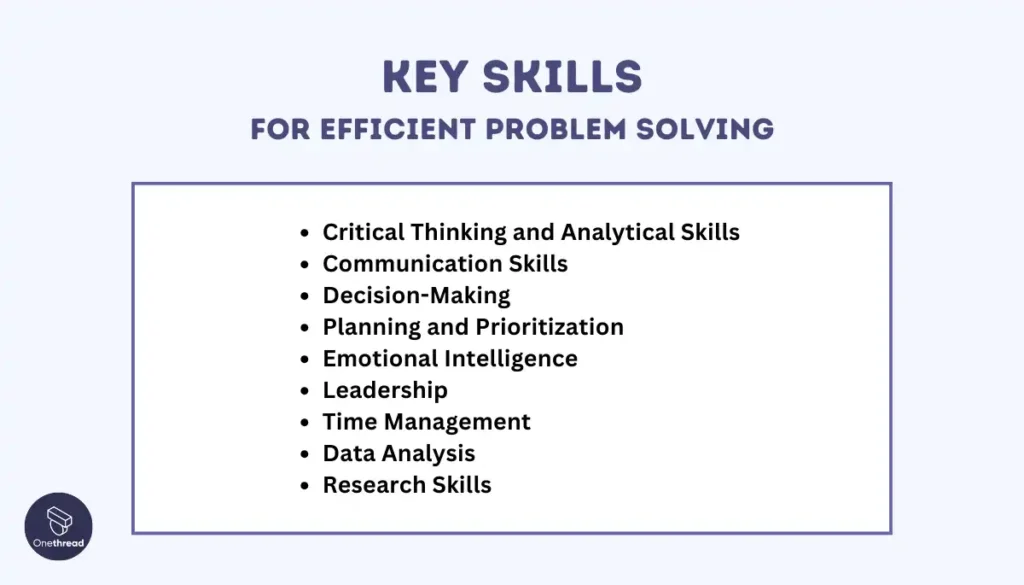

Key Skills for Efficient Problem Solving

Efficient problem-solving requires breaking down issues logically, evaluating options, and implementing practical solutions.

Key skills include critical thinking to understand root causes, creativity to brainstorm innovative ideas, communication abilities to collaborate with others, and decision-making to select the best way forward. Staying adaptable, reflecting on outcomes, and applying lessons learned are also essential.

With practice, these capacities will lead to increased personal and team effectiveness in systematically addressing any problem.

Let’s explore the powers you need to become a problem-solving hero!

Critical Thinking and Analytical Skills

Critical thinking and analytical skills are vital for efficient problem-solving as they enable individuals to objectively evaluate information, identify key issues, and generate effective solutions.

These skills facilitate a deeper understanding of problems, leading to logical, well-reasoned decisions. By systematically breaking down complex issues and considering various perspectives, individuals can develop more innovative and practical solutions, enhancing their problem-solving effectiveness.

Communication Skills

Effective communication skills are essential for efficient problem-solving as they facilitate clear sharing of information, ensuring all team members understand the problem and proposed solutions.

These skills enable individuals to articulate issues, listen actively, and collaborate effectively, fostering a productive environment where diverse ideas can be exchanged and refined. By enhancing mutual understanding, communication skills contribute significantly to identifying and implementing the most viable solutions.

Decision-Making

Strong decision-making skills are crucial for efficient problem-solving, as they enable individuals to choose the best course of action from multiple alternatives.

These skills involve evaluating the potential outcomes of different solutions, considering the risks and benefits, and making informed choices. Effective decision-making leads to the implementation of solutions that are likely to resolve problems effectively, ensuring resources are used efficiently and goals are achieved.

Planning and Prioritization

Planning and prioritization are key for efficient problem-solving, ensuring resources are allocated effectively to address the most critical issues first. This approach helps in organizing tasks according to their urgency and impact, streamlining efforts towards achieving the desired outcome efficiently.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence enhances problem-solving by allowing individuals to manage emotions, understand others, and navigate social complexities. It fosters a positive, collaborative environment, essential for generating creative solutions and making informed, empathetic decisions.

Leadership skills drive efficient problem-solving by inspiring and guiding teams toward common goals. Effective leaders motivate their teams, foster innovation, and navigate challenges, ensuring collective efforts are focused and productive in addressing problems.

Time Management

Time management is crucial in problem-solving, enabling individuals to allocate appropriate time to each task. By efficiently managing time, one can ensure that critical problems are addressed promptly without neglecting other responsibilities.

Data Analysis

Data analysis skills are essential for problem-solving, as they enable individuals to sift through data, identify trends, and extract actionable insights. This analytical approach supports evidence-based decision-making, leading to more accurate and effective solutions.

Research Skills

Research skills are vital for efficient problem-solving, allowing individuals to gather relevant information, explore various solutions, and understand the problem’s context. This thorough exploration aids in developing well-informed, innovative solutions.

Becoming a great problem solver takes practice, but with these skills, you’re on your way to becoming a problem-solving hero.

How to Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills?

Improving your problem-solving skills can make you a master at overcoming challenges. Learn from experts, practice regularly, welcome feedback, try new methods, experiment, and study others’ success to become better.

Learning from Experts

Improving problem-solving skills by learning from experts involves seeking mentorship, attending workshops, and studying case studies. Experts provide insights and techniques that refine your approach, enhancing your ability to tackle complex problems effectively.

To enhance your problem-solving skills, learning from experts can be incredibly beneficial. Engaging with mentors, participating in specialized workshops, and analyzing case studies from seasoned professionals can offer valuable perspectives and strategies.

Experts share their experiences, mistakes, and successes, providing practical knowledge that can be applied to your own problem-solving process. This exposure not only broadens your understanding but also introduces you to diverse methods and approaches, enabling you to tackle challenges more efficiently and creatively.

Improving problem-solving skills through practice involves tackling a variety of challenges regularly. This hands-on approach helps in refining techniques and strategies, making you more adept at identifying and solving problems efficiently.

One of the most effective ways to enhance your problem-solving skills is through consistent practice. By engaging with different types of problems on a regular basis, you develop a deeper understanding of various strategies and how they can be applied.

This hands-on experience allows you to experiment with different approaches, learn from mistakes, and build confidence in your ability to tackle challenges.

Regular practice not only sharpens your analytical and critical thinking skills but also encourages adaptability and innovation, key components of effective problem-solving.

Openness to Feedback

Being open to feedback is like unlocking a secret level in a game. It helps you boost your problem-solving skills. Improving problem-solving skills through openness to feedback involves actively seeking and constructively responding to critiques.

This receptivity enables you to refine your strategies and approaches based on insights from others, leading to more effective solutions.

Learning New Approaches and Methodologies

Learning new approaches and methodologies is like adding new tools to your toolbox. It makes you a smarter problem-solver. Enhancing problem-solving skills by learning new approaches and methodologies involves staying updated with the latest trends and techniques in your field.

This continuous learning expands your toolkit, enabling innovative solutions and a fresh perspective on challenges.

Experimentation

Experimentation is like being a scientist of your own problems. It’s a powerful way to improve your problem-solving skills. Boosting problem-solving skills through experimentation means trying out different solutions to see what works best. This trial-and-error approach fosters creativity and can lead to unique solutions that wouldn’t have been considered otherwise.

Analyzing Competitors’ Success

Analyzing competitors’ success is like being a detective. It’s a smart way to boost your problem-solving skills. Improving problem-solving skills by analyzing competitors’ success involves studying their strategies and outcomes. Understanding what worked for them can provide valuable insights and inspire effective solutions for your own challenges.

Challenges in Problem-Solving

Facing obstacles when solving problems is common. Recognizing these barriers, like fear of failure or lack of information, helps us find ways around them for better solutions.

Fear of Failure

Fear of failure is like a big, scary monster that stops us from solving problems. It’s a challenge many face. Because being afraid of making mistakes can make us too scared to try new solutions.

How can we overcome this? First, understand that it’s okay to fail. Failure is not the opposite of success; it’s part of learning. Every time we fail, we discover one more way not to solve a problem, getting us closer to the right solution. Treat each attempt like an experiment. It’s not about failing; it’s about testing and learning.

Lack of Information

Lack of information is like trying to solve a puzzle with missing pieces. It’s a big challenge in problem-solving. Because without all the necessary details, finding a solution is much harder.

How can we fix this? Start by gathering as much information as you can. Ask questions, do research, or talk to experts. Think of yourself as a detective looking for clues. The more information you collect, the clearer the picture becomes. Then, use what you’ve learned to think of solutions.

Fixed Mindset

A fixed mindset is like being stuck in quicksand; it makes solving problems harder. It means thinking you can’t improve or learn new ways to solve issues.

How can we change this? First, believe that you can grow and learn from challenges. Think of your brain as a muscle that gets stronger every time you use it. When you face a problem, instead of saying “I can’t do this,” try thinking, “I can’t do this yet.” Look for lessons in every challenge and celebrate small wins.

Everyone starts somewhere, and mistakes are just steps on the path to getting better. By shifting to a growth mindset, you’ll see problems as opportunities to grow. Keep trying, keep learning, and your problem-solving skills will soar!

Jumping to Conclusions

Jumping to conclusions is like trying to finish a race before it starts. It’s a challenge in problem-solving. That means making a decision too quickly without looking at all the facts.

How can we avoid this? First, take a deep breath and slow down. Think about the problem like a puzzle. You need to see all the pieces before you know where they go. Ask questions, gather information, and consider different possibilities. Don’t choose the first solution that comes to mind. Instead, compare a few options.

Feeling Overwhelmed

Feeling overwhelmed is like being buried under a mountain of puzzles. It’s a big challenge in problem-solving. When we’re overwhelmed, everything seems too hard to handle.

How can we deal with this? Start by taking a step back. Breathe deeply and focus on one thing at a time. Break the big problem into smaller pieces, like sorting puzzle pieces by color. Tackle each small piece one by one. It’s also okay to ask for help. Sometimes, talking to someone else can give you a new perspective.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is like wearing glasses that only let you see what you want to see. It’s a challenge in problem-solving. Because it makes us focus only on information that agrees with what we already believe, ignoring anything that doesn’t.

How can we overcome this? First, be aware that you might be doing it. It’s like checking if your glasses are on right. Then, purposely look for information that challenges your views. It’s like trying on a different pair of glasses to see a new perspective. Ask questions and listen to answers, even if they don’t fit what you thought before.

Groupthink is like everyone in a group deciding to wear the same outfit without asking why. It’s a challenge in problem-solving. It means making decisions just because everyone else agrees, without really thinking it through.

How can we avoid this? First, encourage everyone in the group to share their ideas, even if they’re different. It’s like inviting everyone to show their unique style of clothes.

Listen to all opinions and discuss them. It’s okay to disagree; it helps us think of better solutions. Also, sometimes, ask someone outside the group for their thoughts. They might see something everyone in the group missed.

Overcoming obstacles in problem-solving requires patience, openness, and a willingness to learn from mistakes. By recognizing these barriers, we can develop strategies to navigate around them, leading to more effective and creative solutions.

What are the most common problem-solving techniques?

The most common techniques include brainstorming, the 5 Whys, mind mapping, SWOT analysis, and using algorithms or heuristics. Each approach has its strengths, suitable for different types of problems.

What’s the best problem-solving strategy for every situation?

There’s no one-size-fits-all strategy. The best approach depends on the problem’s complexity, available resources, and time constraints. Combining multiple techniques often yields the best results.

How can I improve my problem-solving skills?

Improve your problem-solving skills by practicing regularly, learning from experts, staying open to feedback, and continuously updating your knowledge on new approaches and methodologies.

Are there any tools or resources to help with problem-solving?

Yes, tools like mind mapping software, online courses on critical thinking, and books on problem-solving techniques can be very helpful. Joining forums or groups focused on problem-solving can also provide support and insights.

What are some common mistakes people make when solving problems?

Common mistakes include jumping to conclusions without fully understanding the problem, ignoring valuable feedback, sticking to familiar solutions without considering alternatives, and not breaking down complex problems into manageable parts.

Final Words

Mastering problem-solving strategies equips us with the tools to tackle challenges across all areas of life. By understanding and applying these techniques, embracing a growth mindset, and learning from both successes and obstacles, we can transform problems into opportunities for growth. Continuously improving these skills ensures we’re prepared to face and solve future challenges more effectively.

Let's Get Started with Onethread

Onethread empowers you to plan, organise, and track projects with ease, ensuring you meet deadlines, allocate resources efficiently, and keep progress transparent.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy .

Giving modern marketing teams superpowers with short links that stand out.

- Live Product Demo

© Copyright 2023 Onethread, Inc

What Are Problem-Solving Skills? Definition and Examples

- Share on Twitter Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn Share on LinkedIn