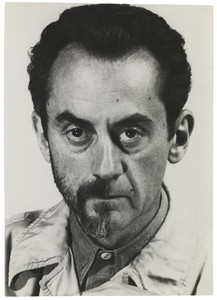

American Photographer, Sculptor, Painter, and Filmmaker

Summary of Man Ray

Man Ray's career is distinctive above all for the success he achieved in both the United States and Europe. First maturing in the center of American modernism in the 1910s, he made Paris his home in the 1920s and 1930s, and in the 1940s he crossed the Atlantic once again, spending periods in New York and Hollywood. His art spanned painting, sculpture, film, prints and poetry, and in his long career he worked in styles influenced by Cubism , Futurism , Dada and Surrealism . He also successfully navigated the worlds of commercial and fine art, and came to be a sought-after fashion photographer. He is perhaps most remembered for his photographs of the inter-war years, in particular the camera-less pictures he called 'Rayographs', but he always regarded himself first and foremost as a painter.

Accomplishments

- Although he matured as an abstract painter, Man Ray eventually disregarded the traditional superiority painting held over photography and happily moved between different forms. Dada and Surrealism were important in encouraging this attitude; they also persuaded him that the idea motivating a work of art was more important than the work of art itself.

- For Man Ray, photography often operated in the gap between art and life. It was a means of documenting sculptures that never had an independent life outside the photograph, and it was a means of capturing the activities of his avant-garde friends. His work as a commercial photographer encouraged him to create fine, carefully composed prints, but he would never aspire to be a fine art photographer in the manner of his early inspiration, Alfred Stieglitz .

- André Breton once described Man Ray as a 'pre-Surrealist', something which accurately describes the artist's natural affinity for the style. Even before the movement had coalesced, in the mid 1920s, his work, influenced by Marcel Duchamp , had Surrealist undertones, and he would continue to draw on the movement's ideas throughout his life. His work has ultimately been very important in popularizing Surrealism.

The Life of Man Ray

Keeping his upbringing and past a mystery, Man Ray thought of himself as a modern day "Thoureau breaking free of all ties and duties to society," an approach he expanded into the avant-garde art world, presenting himself as an "enigma," with an eye toward creating provocative art.

Important Art by Man Ray

L'Enigme d'Isidore Ducasse (The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse)

This early, assisted readymade (a found object slightly altered) was created a year before Man Ray left for France. Marcel Duchamp's influence and assistance are evident in this Dada object, in which a sewing machine is wrapped in an army blanket, and tied with a string. The title comes from French poet Isidore Ducasse (1846-70) and the imagery comes from a quote in his book Les Chants de Maldoror (1869): 'Beautiful as the chance meeting, on a dissecting table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella'. Chance effects were important to the Dada artists, and the piece is very much in that spirit, but it also prefigures the Surrealists' interest in revealing the creative power of the unconscious. The original object was created and then dismantled after the photograph was taken. Ray did not reveal the 'enigma' under the felt and intended the photograph as a riddle for the viewers to solve with the title providing a hint.

Object wrapped in felt and string - National Gallery of Australia, Parkes (reconstructed in 1971)

Le Cadeau (The Gift)

This piece was made in the afternoon on the opening day of Man Ray's first solo show in Paris. It was intended as a gift to the gallery owner, the poet Philippe Soupault, and Ray added it to the show at the last minute. But the object received much attention and disappeared at the end of the opening. Another assisted readymade, Ray took a simple utilitarian object, an iron, and made it evoke different qualities by attaching the tacks. Hence the tacks, which cling and hold, contrast with the iron, which is meant to smoothly glide, and both are rendered useless.

Iron and tacks - The Museum of Modern Art, New York (replica of the lost original)

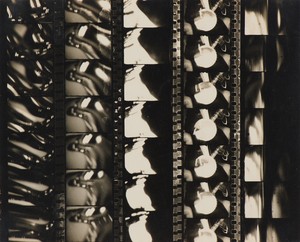

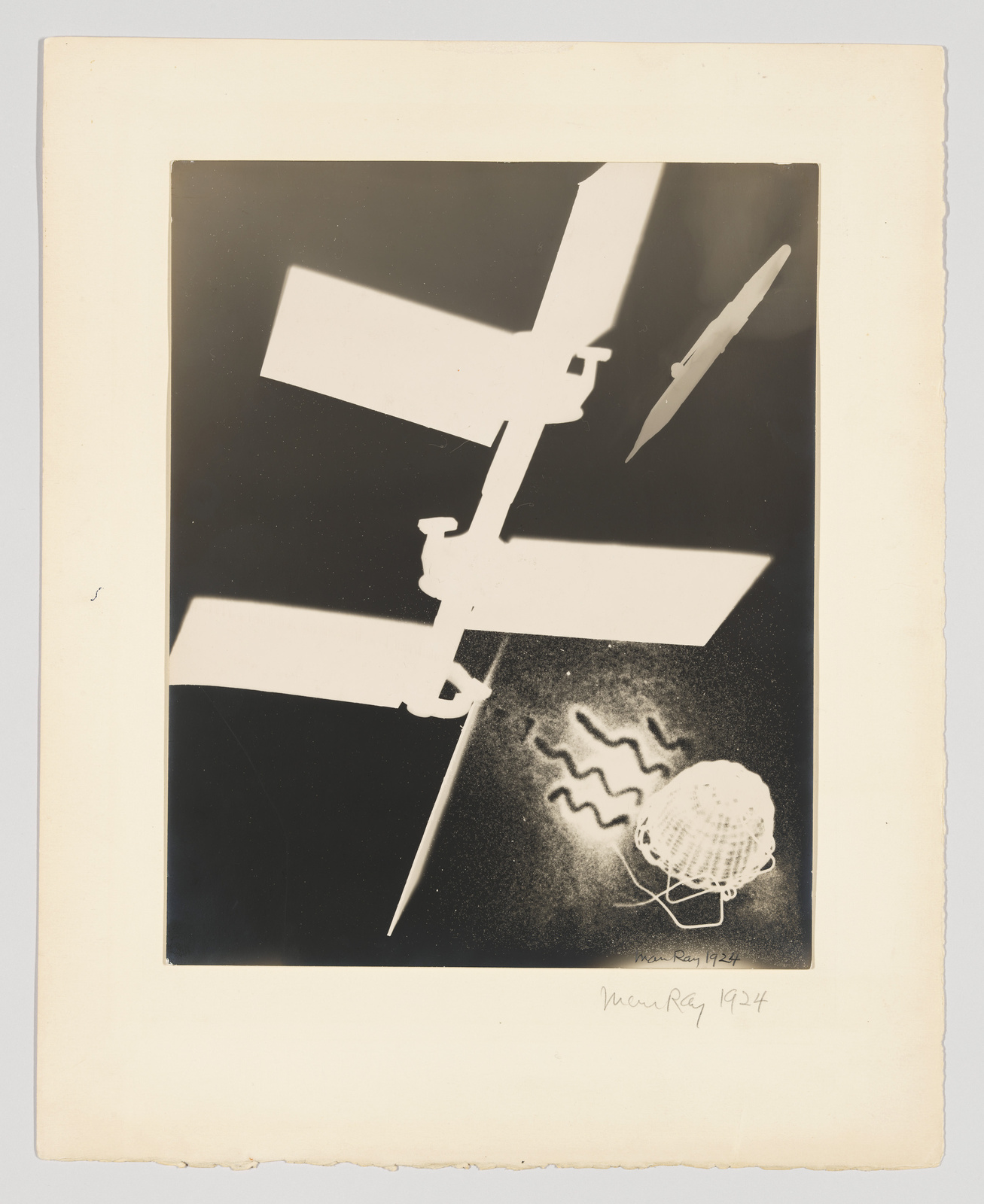

Rayography (The Kiss)

This is one of Man Ray's earliest Rayograms, a process by which objects are laid directly on to a photo-sensitive paper then exposed to light. To create this particular picture, he transferred the silhouette of a pair of hands to the photographic paper then repeated the procedure with a pair of heads (his and his then lover's, Kiki de Montparnasse). Rayograms gave Man Ray an opportunity to be in direct contact with his work and react to his creations immediately by adding one layer upon the next layer. He used inanimate objects as well as his own body to create his earlier pictures, and the pictures sometimes have an autobiographical quality, with many of his photographs portraying his lovers.

Gelatin silver print (photogram) - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

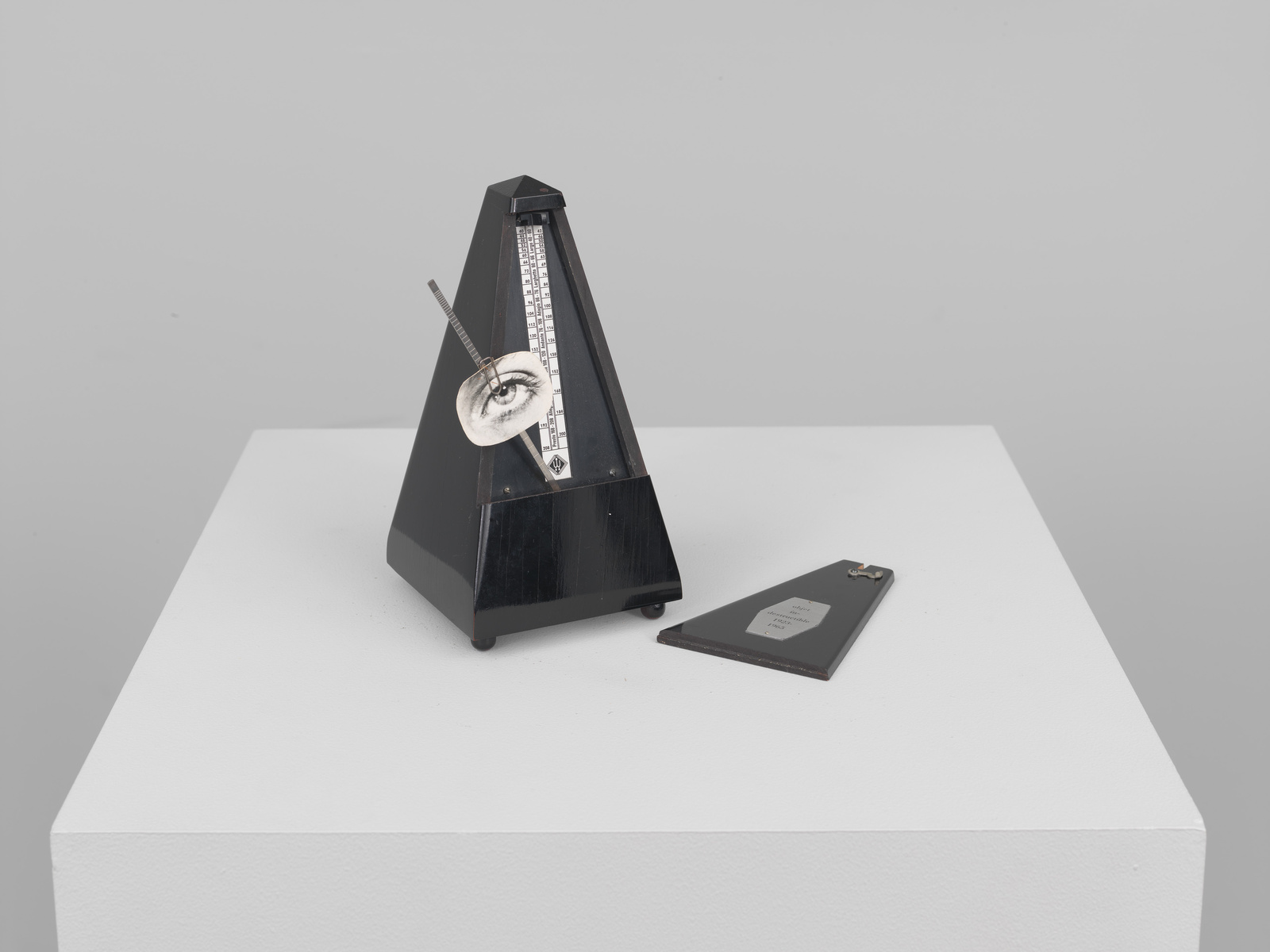

Objet à détruire (Object to be Destroyed)

The piece was first intended as a silent witness in Ray's studio - watching him paint. He had the original idea that "a painter needs an audience, so I also clipped a photo of an eye to the metronome's swinging arm to create the illusion of being watched as I painted." Thus the sculpture served as a silent and constant observer of the artist working. In the second, 1932 version, Ray substituted the eye of the photographer Lee Miller, his former lover, after she left him and married a successful Egyptian businessman. He wanted to attack Miller by "breaking her up" in his works that feature her, and thus this second version was accompanied by the following instructions: "Cut out the eye from a photograph of one who has been loved but is seen no more. Attach the eye to the pendulum of a metronome and regulate the weight to suit the tempo desired. Keep going to the limit of endurance. With a hammer well-aimed, try to destroy the whole at a single blow." It was later reconstructed, made into multiples, and renamed Indestructible Object .

Metronome with cutout photograph of eye on pendulum - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

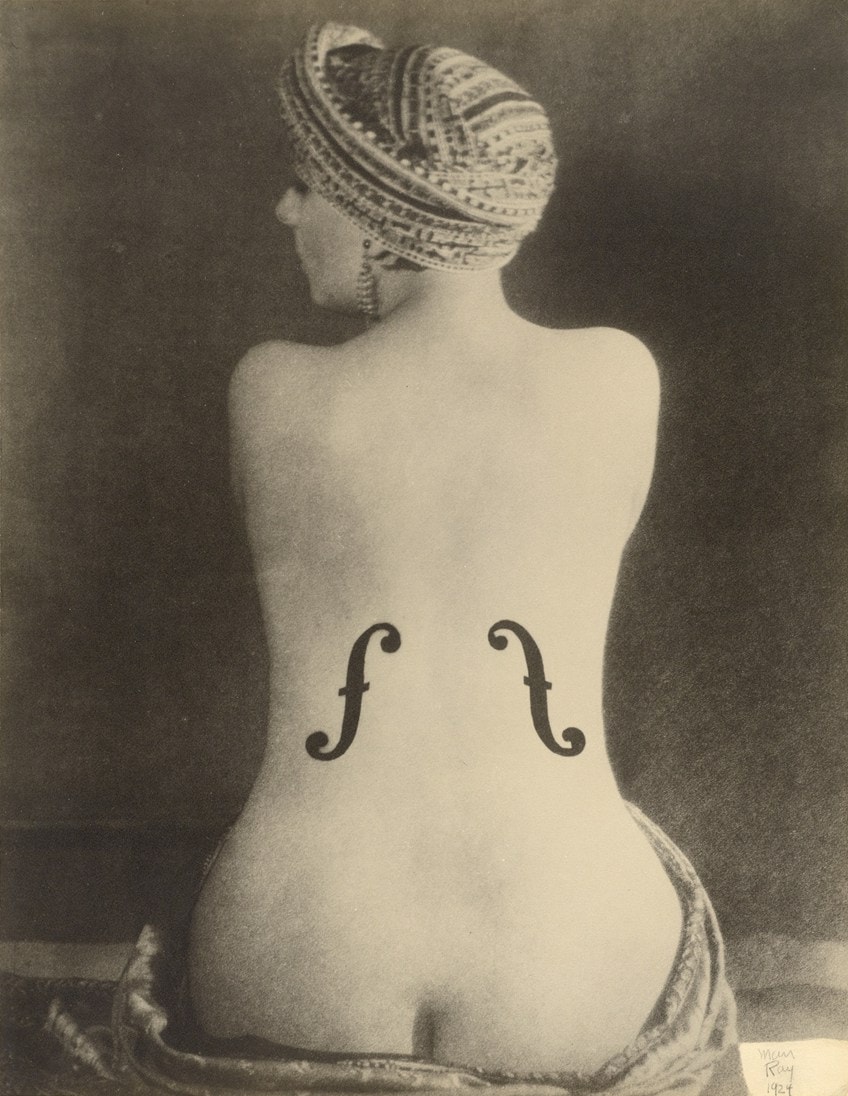

Le Violon d'Ingres (The Violin of Ingres)

Inspired by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres's La Grande Baigneuse , Ray used Kiki de Montparnasse wearing a turban as a model for this piece. He transformed the female body into a musical instrument by painting sound-holes on her back, playing with the idea of objectification of an animate body. Throughout his career Man Ray was fascinated with juxtaposing an object with a female body. Ingres's works were admired by many surrealist artists, including Ray, for his representation of distorted female figures. Ingres's well-known passion for the violin created the colloquialism in French, 'violon d'Ingres' , meaning a hobby. Many describe Le Violon d'Ingres as a visual pun, depicting his muse, Kiki, as Ray's 'violon d'Ingres.' This image is one of many of Man Ray's photographs that have gone on to have a rich afterlife in popular culture. F-holes have become a popular tattoo design amongst musicians, and fashion designers like Viktor and Rolf referenced the image to create their spring 2008 collection.

Gelatin silver print - J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

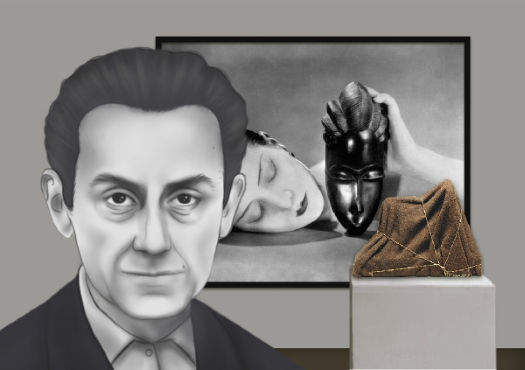

Noire et Blanche (Black and White)

This photograph of Kiki de Montparnasse's head next to an African ceremonial mask bears a title that references both the black and white process of photography as well as skin color. It was created at a time when African art and culture was much in vogue. The oval faces of the two almost look identical in their serene expressions, but he contrasts her soft pale face with the shiny black mask. He simplifies the conflict of society into a problem of lighting and imagery in aesthetics - one oval next to another oval; one laying on its side contrasted with another that is erect; one lit from above and the other from the side.

Les Larmes (Glass Tears)

Looking almost like a film still, this cropped photograph demonstrates Man Ray's interest in cinematic narrative. The model's eyes and mascara-coated lashes are looking upward, invoking the viewers to wonder where she's looking and what is the source of her distress. The piece was created soon after the artist's break-up with his assistant and lover, Lee Miller. Ray created multiple works in an attempt to "break her up" as a revenge on a lover who left him (similar to Indestructible Object ).

A l'heure de l'observatoire: Les Amoureux (Observatory Time: The Lovers)

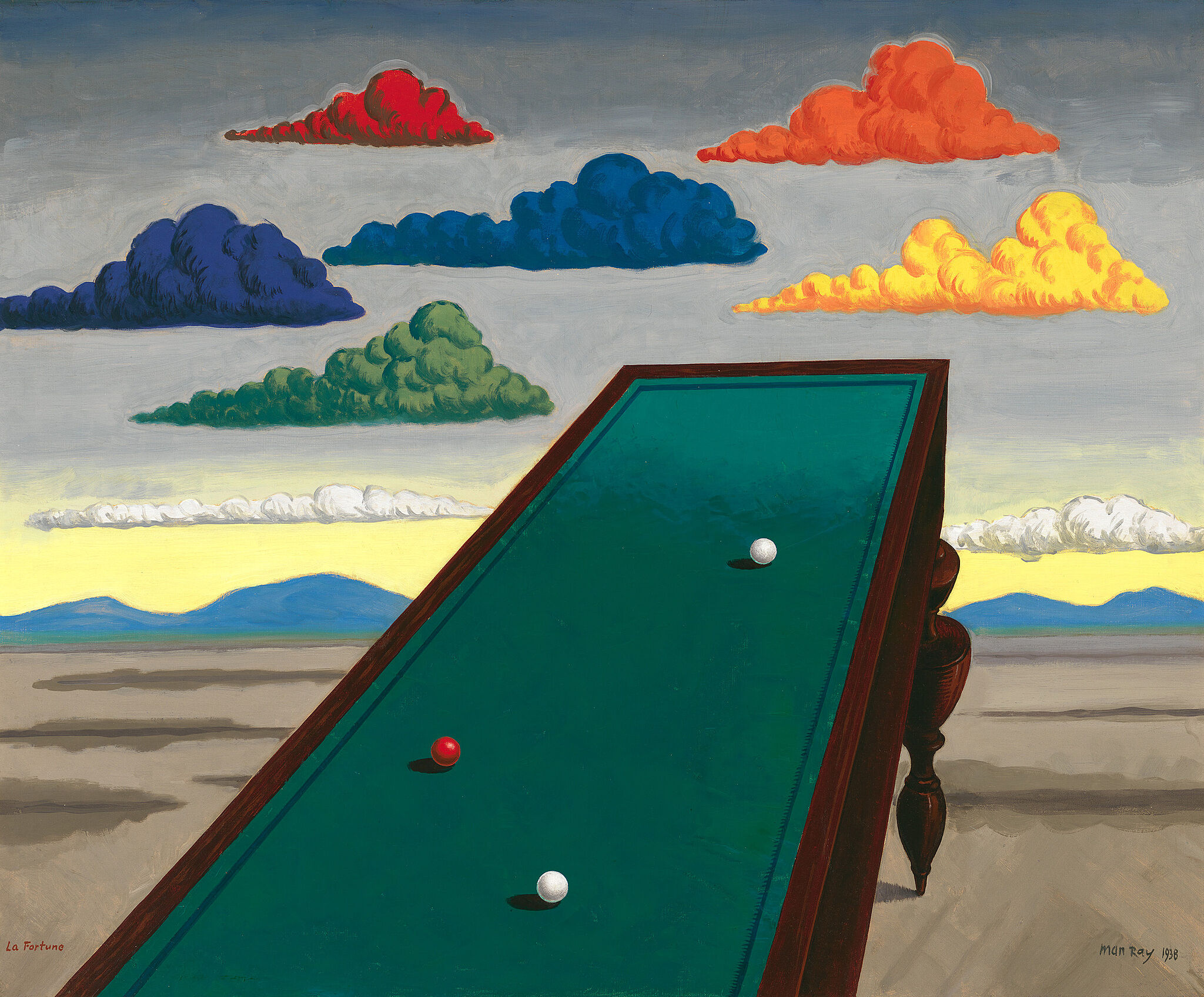

One of Man Ray's most memorable paintings, Observatory Time , is featured in this black-and-white photograph, along with a nude. It includes a depiction of the lips of his departed lover, Lee Miller, floating in the sky above the Paris Observatory. In the photograph, the nude is lying on her side on a sofa underneath the painting, with a chessboard at her feet. Observatory Time hints at what the woman might be dreaming: a nightmare or an erotic fantasy. The lips in the picture were an inspiration for the logo of The Rocky Horror Picture Show , and many other pop culture iconic images. The chessboard appears in many of the artist's works - Duchamp, Picabia and Man Ray all loved playing chess. And Man Ray considered a grid of squares, "the basis for all art... it helps you to understand the structure, to master a sense of order." He also made chess set designs and photographs of chessboards, pieces and players.

Private Collection

Biography of Man Ray

Man Ray was born as Emmanuel Radnitzky in 1890 to a Russian-Jewish immigrant family in Philadelphia. His tailor father and seamstress mother soon relocated the family to the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, where Ray spent most of his childhood. His family changed their surname to Ray due to the fear of anti-Semitism. His name evolved to Man Ray after shortening his nickname, Manny, to Man. He kept his family background secret for most of his career, though the influence of his parents' occupations is evident in many of his works.

In high school, Ray learned freehand drawing, drafting and other basic techniques of architecture and engineering. He also excelled in his art class. Though he hated the special attention from his art teacher, he still frequented art museums and studied the works of the Old Masters on his own. Such self-motivation from the early age proved to be a solid grounding for the versatility he showed throughout his artistic career. Upon graduating from high school in 1908, he turned down a scholarship to study architecture, and began pursuing his career as an artist.

Early Training

In his studio at his parents' house, he worked hard towards becoming a painter while taking odd jobs as a commercial artist. He familiarized himself with the world of art by frequenting art galleries and museums in New York City and became attracted to contemporary avant-garde art from Europe. In 1912, he enrolled in the Ferrer School and began developing as a serious artist. While studying at this school that was founded by libertarian ideals, he met his first influential teachers and artists like Robert Henri, Samuel Halpert, Max Weber, and Adolf Wolff and was surrounded by those with anarchist ideas, which helped shape his own ideology.

After briefly sharing a small studio in Manhattan with Adolf Wolff, Man Ray moved to an artist colony in New Jersey in the spring of 1913 just across the river from Manhattan. He shared a small shack with Samuel Halpert, who inspired Ray as a painter to develop ideas and techniques that would later become a foundation for his career. During this time, he frequented the 291 Gallery in New York City. Ray developed a close personal relationship with the gallery owner and photographer, Alfred Stieglitz , who introduced Ray to the medium. Ray met a Belgian poet, Adon Lacroix (aka Donna Lecoeur) in New York, and they married in 1914. In 1915, Ray met Marcel Duchamp who was visiting the colony with collector Walter Arensberg and they soon developed a lasting friendship. This new friendship helped define Ray's interest in the subject of movement and guided his focus to Surrealism and Dada .

In the early period of Ray's career, he painted in the Cubist style. His first solo show at the Daniel Gallery in 1915 featured thirty paintings and a few drawings. The paintings were a mixture of semi-representational landscapes and abstract paintings of "Arrangements of Forms"; these abstract works showed his developing interest in analytical and cerebral method of working. By this time, he had more inventory of works in his studio than he could keep track of. He started photographing his paintings as documentation and experimenting with the camera as an artistic tool.

With Duchamp, Ray made multiple attempts to promote Dada in New York. They founded the Society of Independent Artists in 1916 and published a single issue of New York Dada in 1920. In the same year they founded the Société Anonyme, Inc. with Katherine Dreier , a prominent art collector. Societe Anonyme was the first museum to devote itself to displaying and promoting modern art in America, preceding The Museum of Modern Art by nine years. However, due to the lack of public enthusiasm for Dada art in New York, and his failed marriage to his first wife, Ray was despondent. With encouragement from Duchamp, Ray moved to Paris in 1921.

Mature Period

Ray lived for the next 18 years in the Montparnasse where he met important thinkers and artists, including James Joyce , Gertrude Stein , Jean Cocteau , and Antonin Artaud . He also met a famous performer, Kiki of Montparnasse, who became his lover and frequent subject in his work for six years. His most influential works such as Indestructible Object (or Object to Be Destroyed), Noire et Blanche (Black and White), Glass Tears, and most of his Rayographs, as well as his fashion photography for Vogue and Vanity Fair were produced during this time.

In 1929 Man Ray hired Lee Miller as an artist assistant. She soon became his lover and the subject in his photographs for three years. Together, they reinvented 'solarization', a photographic process that records images on the negative reversing dark with light and vice versa.

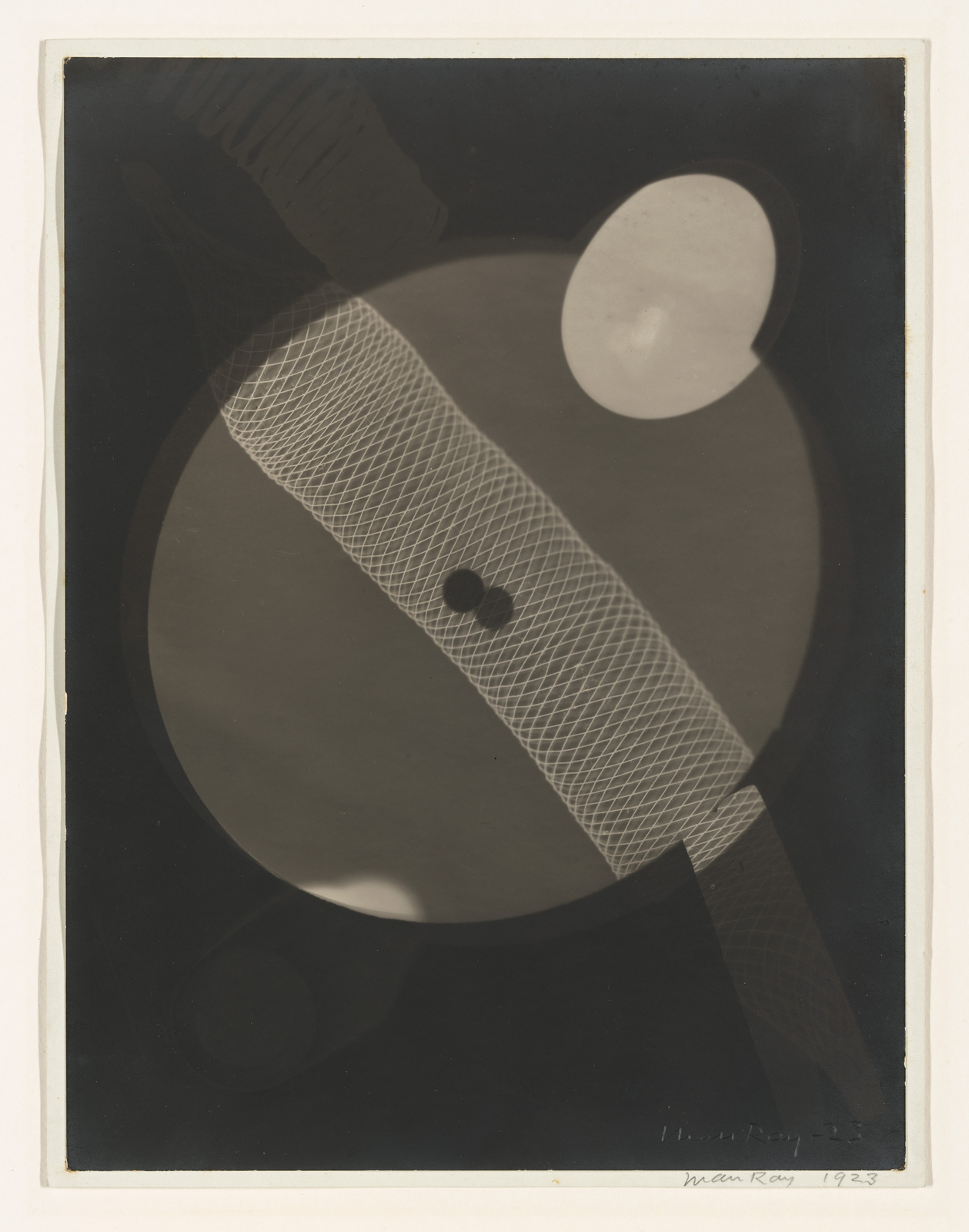

While trying to develop his photographs in the dark room, Ray accidentally discovered a technique called 'shadowgraph' or 'photogram', a process also known as camera-less photography using light sensitive paper. He dubbed this style 'Rayogram' or 'Rayograph'. He explored this technique for more than 40 years, in the process creating many of his most important works including two portfolio books entitled Champs delicieux and Electricite .

Though many of his famous works are in the field of photography, he worked in a variety of media, including painting, writing and film. Between 1923 and 1929 he directed multiple avant-garde short films and collaborated on films with Marcel Duchamp and Fernard Léger . He also collaborated with Paul Eluard to make the books Facile and Les Mains Libres .

Late Years and Death

In 1940, Ray was forced to leave France because of the war, and moved to Los Angeles where he met his last wife, Juliet Browner. They married in 1946.

In the fall of 1944, Ray had his first retrospective at the Pasadena Art Institute, showcasing his paintings, drawings, watercolors and photographs from his thirty-year span as an artist. He had a successful career as a photographer while in Hollywood, but he felt the city lacked stimulus and the kind of appreciation he desired. Even though he was back home in the U.S., Ray thought American critics could not understand him, believing his ability to go from one medium to another and his success in commercial photography confused them.

Ray longed to go back to Montparnasse where he felt at home, eventually returning in 1951. Upon his arrival, he began writing his autobiography to explain himself to the people who he alleged misunderstood and misrepresented his work. The resulting Self-Portrait was published in 1963.

Right up until his death at the age of 86, he continued working on new paintings, photographs, collages and art objects. He died of a lung infection in 1976.

The Legacy of Man Ray

Though often shadowed by his lifelong friend and collaborator, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray played a major role in Dada and Surrealist movements in America as well as in Europe. His multiple attempts to promote avant-garde art movements in New York widened the horizons of the American art scene. His serious yet quirky imagery has influenced a broad audience through different iterations of his work in pop culture. Many of his important works were donated to museums around the world through a trust set up by his wife before her death in 1991. Most importantly, his process-oriented art making and versatility have influenced a number of modern and contemporary artists, from Andy Warhol to Joseph Kosuth , who like Ray strove to continually blur the boundaries between artistic disciplines.

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on Man Ray

- Man Ray: American Artist Our Pick By Neil Baldwin

- Man Ray Our Pick By Guido Comis, Marco Franciolli

- Man Ray/Lee Miller: Partners in Surrealism By Phillip Prodger

- Man Ray in Paris By Erin C. Garcia

- Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens By Wendy A. Grossman

- Self Portrait: Man Ray

- Man Ray: La Photographie N'Est Pas L'Art Our Pick

- In Focus: Man Ray: Photographs From the J. Paul Getty Museum Our Pick By Katherine Ware

- Man Ray: Unconcerned But Not Indifferent By John P. Jacob

- Photographs by Man Ray: 105 Works, 1920-1934 Our Pick By Man Ray

- Man Ray: Portraits. Hollywood-Paris-Hollywood Our Pick By Clement Cheroux

- Man Ray: Photography and Its Double By Alain Sayag, Emmanuelle De I'Ecotais

- Man Ray: Women By Valerio Deho

- The Man Ray Trust Our Pick

- ICP 1998 Man Ray Exhibit website

- Photo Library of Man Ray's work

- Letters and Writings By or Addressed to the Artist

- Mercurial Jester, Revealing and Concealing Our Pick By Karen Rosenberg / The New York Times / November 19, 2009

- Getty Acquires Man Ray Archive Our Pick By Stephanie Cash / Art in America / December 15, 2011

- Art Review; Emmanuel Radnitsky, Before He Was Man Ray Our Pick By Grace Glueck / The New York Times / March 7, 2003

- Art in Review; Marcel Duchamp/Man Ray By Ken Johnson / The New York Times / February 18, 2000

- Man Ray Without The Secrets By Alan Riding / The New York Times / May 14, 1998

- Review/Art; Man Ray's Beginnings By Michael Kimmelman / The New York Times / January 6, 1989

- Photographer Man Ray - A Film by Jean-Paul Fargier (1932) Our Pick

- "Crimes against Photography": Man Ray and the Rayograph Our Pick Overview of the artist - an animated story

- The Adventure of Photography - The Surrealists Our Pick

- Les Mystères du Château du Dé (1929) The Mysteries of the Chateau of Dice is a 1929 film directed by Man Ray

- Retour a la raison (1923)

- Man Ray interview

- A video explaining his process "Rayograph" by MoMA's curator Our Pick MoMA Multimedia

- PBS American Masters: "Prophet of the Avant-Garde" Our Pick September 17, 2005

- Character called "Man Ray" in SpongeBob SquarePants

- "Lips (Heure de l'Observatoire)" was the inspiration for the logo of The Rocky Horror Picture Show

Similar Art

Fountain (1917)

Great Masturbator (1929)

Très rare tableau sur la terre (Very Rare Picture on the Earth) (1915)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Jin Jung

Edited and published by The Art Story Contributors

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What are some of the major film festivals?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Artnet - Man Ray

- Public Broadcasting Service - American Masters - Biography of Man Ray

- International Photography Hall of Fame - Biography of Man Ray Emmanuel Radnitzky

- Masterworks Fine Art Gallery - Man Ray

- Pennsylvania Center for the Book - Biography of Man Ray

- The Art Story - Biography of Man Ray

- BBC - Culture - Fashion photography's reluctant poster boy

- Art in Context - Man Ray – The Life and Works of Artist Emmanuel Radnitzky

- Man Ray - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Man Ray (born August 27, 1890, Philadelphia , Pennsylvania , U.S.—died November 18, 1976, Paris , France) was a photographer, painter, and filmmaker who was the only American to play a major role in both the Dada and Surrealist movements.

The son of Jewish immigrants—his father was a tailor and his mother a seamstress—Radnitzky grew up in New York City , where he studied architecture , engineering , and art , and became a painter . As early as 1911, he took up the pseudonym of Man Ray. As a young man, he was a regular visitor to Alfred Stieglitz ’s “291” gallery, where he was exposed to current art trends and earned an early appreciation for photography. In 1915 Man Ray met the French artist Marcel Duchamp , and together they collaborated on many inventions and formed the New York group of Dada artists. Like Duchamp, Man Ray began to produce ready-mades , commercially manufactured objects that he designated as works of art. Among his best-known ready-mades is The Gift (1921), a flatiron with a row of tacks glued to the bottom.

In 1921 Man Ray moved to Paris and became associated with the Parisian Dada and Surrealist circles of artists and writers. Inspired by the liberation promoted by these groups, he experimented with many media. His experiments with photography included rediscovering how to make “cameraless” pictures, or photograms , which he called rayographs . He made them by placing objects directly on light-sensitive paper, which he exposed to light and developed. In 1922 a book of his collected rayographs, Les Champs délicieux (“The Delightful Fields”), was published, with an introduction by the influential Dada artist Tristan Tzara , who admired the enigmatic quality of Man Ray’s images. In 1929, with his lover, photographer and model Lee Miller , Man Ray also experimented with the technique called solarization , which renders part of a photographic image negative and part positive by exposing a print or negative to a flash of light during development. He and Miller were among the first artists to use the process, known since the 1840s, for aesthetic purposes.

Man Ray also pursued fashion and portrait photography and made a virtually complete photographic record of the celebrities of Parisian cultural life during the 1920s and ’30s. Many of his photographs were published in magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar , Vu , and Vogue . He continued his experiments with photography through the genre of portraiture; for example, he gave one sitter three pairs of eyes, and in Le Violon d’Ingres (1924) he photographically superimposed sound holes, or f holes, onto the photograph of the back of a female nude, making the woman’s body resemble that of a violin . He also continued to produce ready-mades. One, a metronome with a photograph of an eye fixed to the pendulum, was called Object to Be Destroyed (1923)—which it was by anti-Dada rioters in 1957.

Man Ray also made films. In one short film , Le Retour à la raison (1923; Return to Reason ), he applied the rayograph technique to motion-picture film, making patterns with salt, pepper, tacks , and pins. His other films include Anémic cinéma (1926; in collaboration with Duchamp) and L’Étoile de mer (1928–29; “Star of the Sea”), which is considered a Surrealist classic.

In 1940 Man Ray escaped the German occupation of Paris by moving to Los Angeles . Returning to Paris in 1946, he continued to paint and experiment until his death. His autobiography, Self-Portrait , was published in 1963 (reprinted 1999).

Man Ray – The Life and Works of Artist Emmanuel Radnitzky

Man Ray’s art career is noteworthy for the popularity he attained in both Europe and the United States. Man Ray’s artworks included sculptures, paintings, prints, and film, and he created in genres inspired by Futurism, Cubism, and Surrealism throughout his lengthy career. Man Ray’s photography was much sought after in the commercial world, and he gained much success as a fashion photographer. However, it is Man Ray’s photographs of the inter-war period that he is most remembered for.

Table of Contents

- 1.1 Education and Early Training

- 1.2 Mature Period

- 1.3 Later Years

- 2.1 The Gift (1921)

- 2.2 Object to be Destroyed (1923)

- 2.3 The Violin of Ingres (1924)

- 2.4 Glass Tears (1932)

- 2.5 Observatory Time: The Lovers (1936)

- 3.1 Who Was Emmanuel Radnitzky?

- 3.2 What Is Man Ray Known For?

- 3.3 What Happened to Man Ray?

An Exploration of Man Ray’s Art and Life

| American | |

| 27 August 1890 | |

| 18 November 1976 | |

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

A Jewish-Russian immigrant family gave birth to Emmanuel Radnitzky in 1890, but out of concern for anti-Semitism, they shortened their last name to Ray. Man Ray kept his family’s genealogy hidden for the majority of his profession as an artist, yet their presence can be seen in several of his works. Ray studied drafting, freehand sketching, and other fundamental architectural and engineering techniques in high school. He also performed really well in his art classes.

Education and Early Training

Man Ray worked hard in his little studio situated at his parent’s home to become an artist while doing side jobs as a commercial illustrator. He became acquainted with the art world through visiting art museums and art galleries in New York City, and he grew intrigued with the latest avant-garde work from Europe. He studied at the Ferrer School in 1912 and launched his career as a professional artist.

He encountered his first notable professors and artists, such as Samuel Halpert, Robert Henri, and Adolf Wolff, while attending this institution established on libertarian beliefs, and was influenced by individuals with anarchist ideals, which helped form his own worldview.

Man Ray relocated to an artist’s community in New Jersey in 1913, after initially sharing a tiny workspace with Adolf Wolff. He occupied a cramped cottage with artist Samuel Halpert, who encouraged Ray to form concepts and methods that would ultimately become the basis of his work. Throughout this period, he visited New York City’s 291 Gallery. Alfred Stieglitz , the gallerist and photographer who exposed Ray to the field, became a close friend of Ray’s. During this time, Man Ray would meet Marcel Duchamp, who was exploring the community with Walter Arensberg, and they quickly became friends.

Ray’s fascination with movement was shaped by this new connection, which led him to Dada and Surrealism.

Man Ray’s early work was devoted to painting in the Cubist style. In 1915, he had his first solo exhibition at the Daniel Gallery, which included 30 canvases and a few sketches. The artworks were a combination of semi-representational sceneries and abstracted “Arrangements of Forms” works; these conceptual works demonstrated his growing interest in analytic and intellectual methods of creating. He had more pieces in his workshop than he could keep count of by this point. As documentation, he began photographing his canvases and experimented with the camera as another tool capable of producing art.

Man Ray and Duchamp made numerous attempts to popularize Dada in New York.

In 1916, they created the Society of Independent Artists, and in 1920, they created the sole edition of New York Dada . The Société Anonyme, Inc . was created that same year by a notable art patron, Katherine Dreier. The Société Anonyme was the very first museum in the US to dedicate itself to presenting and developing modern art, nine years before The Museum of Modern Art. Yet, Ray was depressed owing to the absence of public excitement for Dada artwork in New York, as well as his damaged relationship with his first wife. Man Ray relocated to Paris in 1921, encouraged by Duchamp.

Mature Period

Man Ray resided at Montparnasse for the following 18 years, where he befriended prominent philosophers and artists such as Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, and Antonin Artaud. Ray also met Kiki of Montparnasse, a renowned performer who became his partner and a recurrent topic in his works for six years.

Throughout this time, he created some of his most significant works, including fashion photography for Vanity Fair and Vogue. Ray unintentionally developed a technique called “photogram” while working to develop his images in the dark room, a procedure also referred to as camera-less photography utilizing light-sensitive paper.

He named this method “Rayograph”, and he experimented with it for approximately 40 years.

Later Years

Man Ray was forced to flee France due to the war in 1940 and relocated to Los Angeles, where he met his final wife, Juliet Browner, who he married in 1946. He presented his debut showcase at the Pasadena Art Institute in the autumn of 1944, displaying paintings, sketches, watercolors, and photos from his 30 years as an artist.

When in Hollywood, Ray had a great career as a photographer, but he thought the city was lacking stimulation and the type of recognition he sought.

Despite being back in the United States, Ray believed that his capacity to transition from one discipline to another, as well as his competence in commercial photography, perplexed American critics. Ray yearned to return to Montparnasse, where he was most at ease, and did so in 1951. Following his arrival, he started to write his autobiography in order to defend himself against those he claimed misinterpreted and distorted his works.

He worked on producing paintings, photos, and collages until his passing at 86 years of age.

Important Examples of Man Ray’s Photography and Art

Man Ray’s photographs and other artworks regularly bridged the gap between art and realism. It was a way of chronicling works that never had a life outside of the image, as well as documenting the behavior of his avant-garde colleagues. His job as a commercial photographer inspired him to produce beautiful prints, yet he never aspired to produce fine art photography like his early influence, Alfred Stieglitz.

The Gift (1921)

| 1921 | |

| Tacks and iron | |

| 15 x 9 x 11 | |

| The Museum of Modern Art |

This unique and spontaneous piece was created on the first day of Man Ray’s solo display in Paris. Ray included it in the exhibit at the last minute as a present for the curator, Philippe Soupault. However, the item drew a lot of attention and vanished at the close of the opening.

To create the piece, he took a plain practical object, an iron, and transformed it by adding tacks on it.

As a result, the tacks, which grip and adhere to the surface, conflict with the iron, which is designed to move easily, and in the process, both are rendered unusable. During his career, he created several individual replicas of the piece, and in his final years, Ray created two limited edition reproductions.

Object to be Destroyed (1923)

| 1923 | |

| Metronome and photo | |

| 21 x 11 x 11 | |

| The Museum of Modern Art, New York |

This Man Ray art piece is composed of two elements: one component is a metronome, while a little cutout photo of a woman’s eye completes the composition. The metronome in question is a mass-produced item that may be found in many houses. It was most likely secondhand when Man Ray reconstructed it as an art piece, as it is dented, damaged, lacking minor components, and balances on mismatched feet, despite the fact that its motor is in good working condition.

Its box is composed of wood, while its interior components are metal, and featured a detachable front panel. It is labeled a “readymade”, keeping in the (at-the-time) comparatively new tradition pioneered by Marcel Duchamp of using commonplace produced items in art pieces that were generally altered very little, when at all.

Man Ray swapped out the eye of his former girlfriend, artist Lee Miller, in the subsequent 1932 iteration because she had left him and remarried a rich Egyptian entrepreneur.

The Violin of Ingres (1924)

| 1924 | |

| Gelatin silver print | |

| 29 x 22 | |

| J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

In this example of Man Ray’s artworks, Man Ray employed Kiki de Montparnasse as his model. By using paint to create sound holes on her back, he converted the feminine body into a musical instrument, toying with the concept of objectification of an alive being. Man Ray was obsessed with contrasting an item with a feminine body throughout his career.

The image was originally inspired by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ paintings.

Many artists who worked in the style of Surrealism, including Ray, loved Ingres’ rendering of twisted feminine forms. This is one of several images by Man Ray that have had a long lifespan in popular culture. and Viktor F-holes have emerged as a trendy tattoo motif among band members, and fashion designers such as Rolf and Viktor drew inspiration from the picture while designing their spring 2008 range.

Glass Tears (1932)

| 1932 | |

| Gelatin silver print | |

| 50 x 40 | |

| J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

This very cropped shot, which looks almost like a still frame from a movie, displays Man Ray’s fascination with cinematic storytelling. The model’s eyes are gazing skyward, leading onlookers to ponder where she’s looking and what’s causing her pain. The work was made shortly after the artist’s divorce from his girlfriend, Lee Miller. Ray made a number of pieces in an effort to “break her apart” as retaliation for a girlfriend who abandoned him. This was a common theme in many of his works. The figure is, in reality, a mannequin with glass bead tears glued on her face.

With this piece, Man Ray is once again pursuing his fascination with reality and the imaginary by questioning the nature of still-life photography.

Observatory Time: The Lovers (1936)

| 1936 | |

| Oil painting | |

| 100 x 250 | |

| Private Collection |

This painting has been regarded as the definitive Surrealist artwork , a superb instance of isomorphism, the utilization of biological forms strangely and subtly relating to humanity in a type of precise, lifelike illusionism – the overarching subject in popular Surrealist art during its 1930s peak. Its title embodies Gertrude Stein’s intent on incorporating “time in the arrangement”. Man Ray achieved the dramatic, sweeping message in his works every time.

The larger canvases compelled him to be more methodical in his gestures and pulled him away from the haphazard style that eventually hurt his image as an artist.

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky, Man Ray’s art was intended to offend, entertain, perplex, mystify, and stimulate introspection. He is regarded as an avant-garde artist and a crucial figure in the Surrealism and Dada movements. Man Ray’s numerous endeavors to establish avant-garde artistic groups in New York broadened the American art world’s possibilities. Through several variations of his works in pop culture, his meaningful yet humorous imagery has affected a wide audience for many years.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was emmanuel radnitzky.

Emmanuel Radnitzky is better known to most people as Man Ray the artist. There is a rather sad and unfortunate reason his parents changed his name at an early age, and it has to do with his family history. He is from a family of Jewish-Russian immigrants and he grew up in a period and place where there was much hate for the Jewish people. So, his family decided from an early age that it would be better for him if his name was not something that would hinder his future prospects and cause unnecessary grief for him.

What Is Man Ray Known For?

Man Ray’s photography is the main aspect of his work. Although he was known for being able to create art in many different styles and mediums, it is Man Ray’s photographs that brought him into the public eye. Man Ray’s photography and art encompassed many movements, such as Dada and the Surrealism movement. Throughout his long career, Man Ray made sculptures, paintings, prints, and films in genres inspired by Futurism, Cubism , and Surrealism. By investigating the nature of still-life photography, Man Ray explored his obsession with reality and the fantastical.

What Happened to Man Ray?

Man Ray proceeded to display his artworks in his later years, including displays in London, New York, Paris, and other locations in the years before his passing. On the 18th of November, 1976, he died in his adored Paris. He was 86 years old at the time. His groundbreaking paintings may be seen in museums all around the world, and he is recognized for his stylistic charm and uniqueness. It was his accomplishment to regard the camera like he used a paintbrush, as a basic tool at the disposal of the imagination.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20 th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Man Ray – The Life and Works of Artist Emmanuel Radnitzky.” Art in Context. September 2, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/man-ray/

Meyer, I. (2022, 2 September). Man Ray – The Life and Works of Artist Emmanuel Radnitzky. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/man-ray/

Meyer, Isabella. “Man Ray – The Life and Works of Artist Emmanuel Radnitzky.” Art in Context , September 2, 2022. https://artincontext.org/man-ray/ .

Similar Posts

Winslow Homer – The Life and Paintings of the Famous Watercolor Artist

Fernando Botero – A Look at Fernando Botero Paintings

Tom of Finland Art – A Look at the Influence of Touko Laaksonen on Art

Laurent de Brunhoff – The Celebrated French Author and Illustrator

Gil Elvgren – The Creator of the Ionic Pin Up Paintings

Facts About Paul Klee – The Artistic Alchemist

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

Gagosian Quarterly

- Philanthropy

- Studio Visits

- Recent Issues

November 19, 2018

Man Ray Visual Poet and Wit

At the 2018 frieze masters fair in london, gagosian’s stand presented more than ninety works by man ray. objects and assemblages, collages, oils, prints, drawings, and photographs were displayed in a deliberately crowded, surrealist fashion. here co-curator richard calvocoressi traces the development of the artist’s wide-ranging work and looks at his legendary three-year collaboration with lee miller..

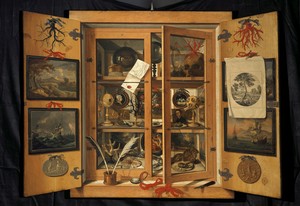

Installation view, Man Ray , Gagosian stand at Frieze Masters, London, 2018

Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

See all Articles

Man Ray (1890–1976) was a leading figure in the Dada and Surrealist movements. Born Emmanuel Radnitzky to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents in Philadelphia, he moved to New York with his family in 1897 and shortened his name to Man Ray around 1912. In 1921 he moved to Paris, where he remained until the outbreak of World War II. Returning to the United States in 1940, he went to live in Hollywood, where in 1946 he married the dancer and model Juliet Browner in a double wedding ceremony with their friends Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. In 1951 he returned to Paris, occupying the same studio apartment near the Jardin du Luxembourg until his death a quarter of a century later.

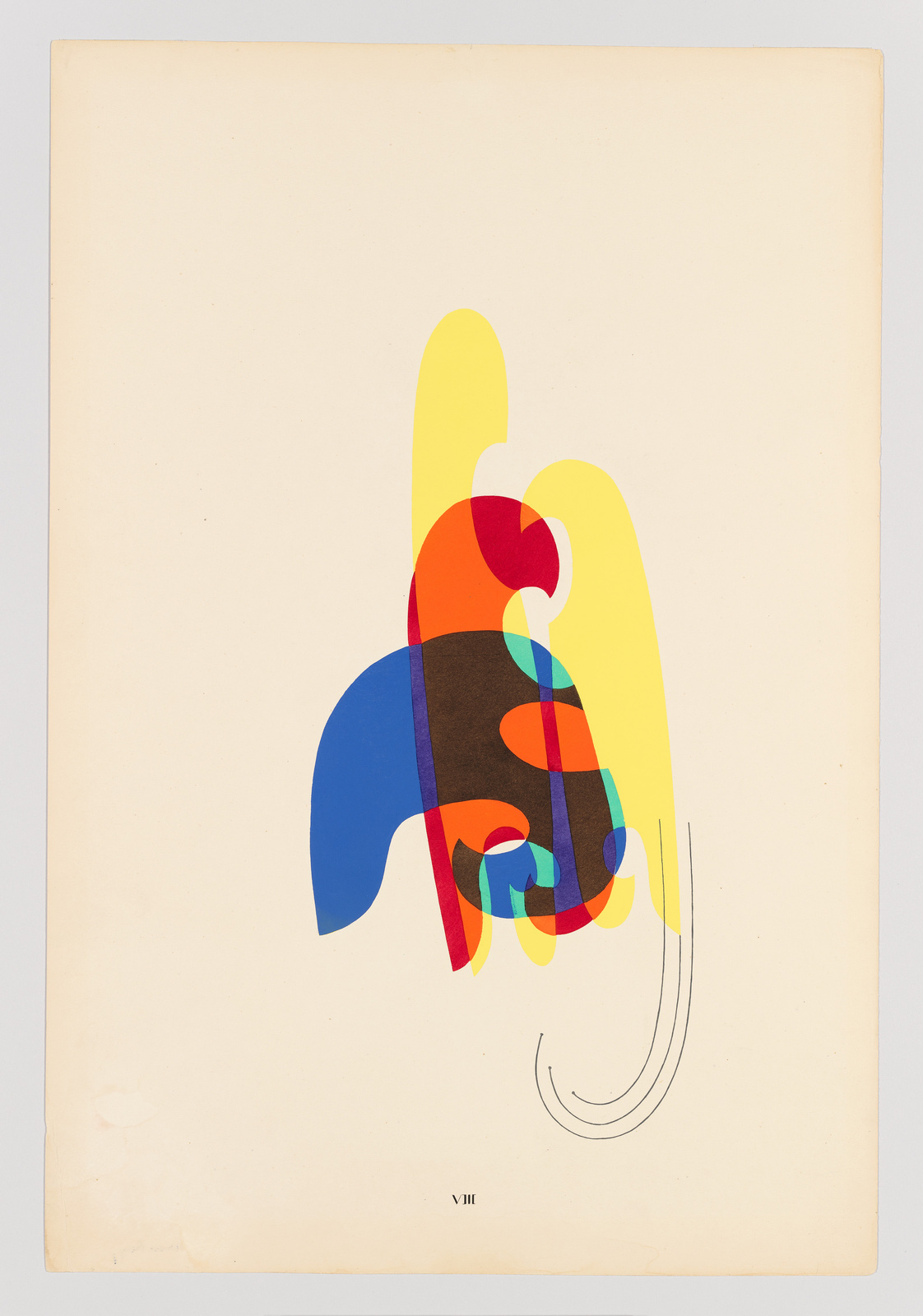

Man Ray worked across a diverse range of mediums, including painting, drawing, objects, photography, artist’s books, and film. Like that of his close friend and fellow iconoclast Francis Picabia, his style as a painter underwent sudden changes and reversals. Neither artist prioritized chronology, consistency, materials, or technical expertise, although Man Ray’s skill with the mechanical airbrush, a tool common in commercial art, was almost as remarkable as his innovative experiments in photography. His earliest mature paintings demonstrate an interest in the planar structures and fragmentation of Cubism. He was later inspired by Marcel Duchamp, who arrived in New York in 1915 and whose work, including Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912), Man Ray had seen at the famous Armory Show in 1913. Under Duchamp’s influence, he began making paintings and collages with invented mechanical forms—sometimes favoring a type of colored paper used in technical draftsmanship—in the satirical spirit of Dada.

Collage (and its offshoot, photomontage) was one of several means favored by Dada artists to depersonalize the artwork. This was also the period of Duchamp’s readymades, ordinary household objects raised to the status of art but exhibiting no evidence of the artist’s touch—the ultimate in depersonalization. Man Ray’s “rayographs”— photographs produced without a camera, by placing random objects on light-sensitive paper and exposing them to light—similarly challenge notions of originality and individual authorship.

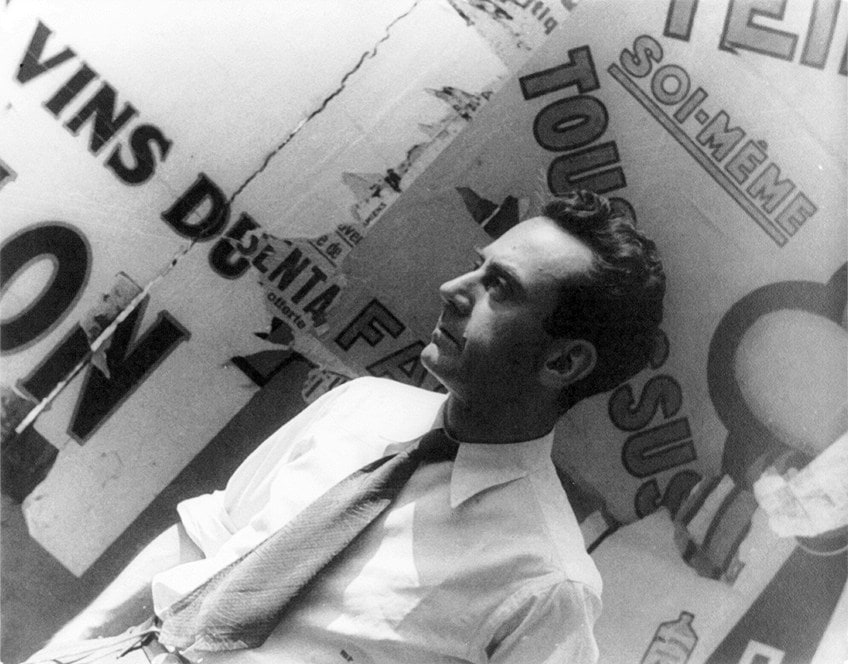

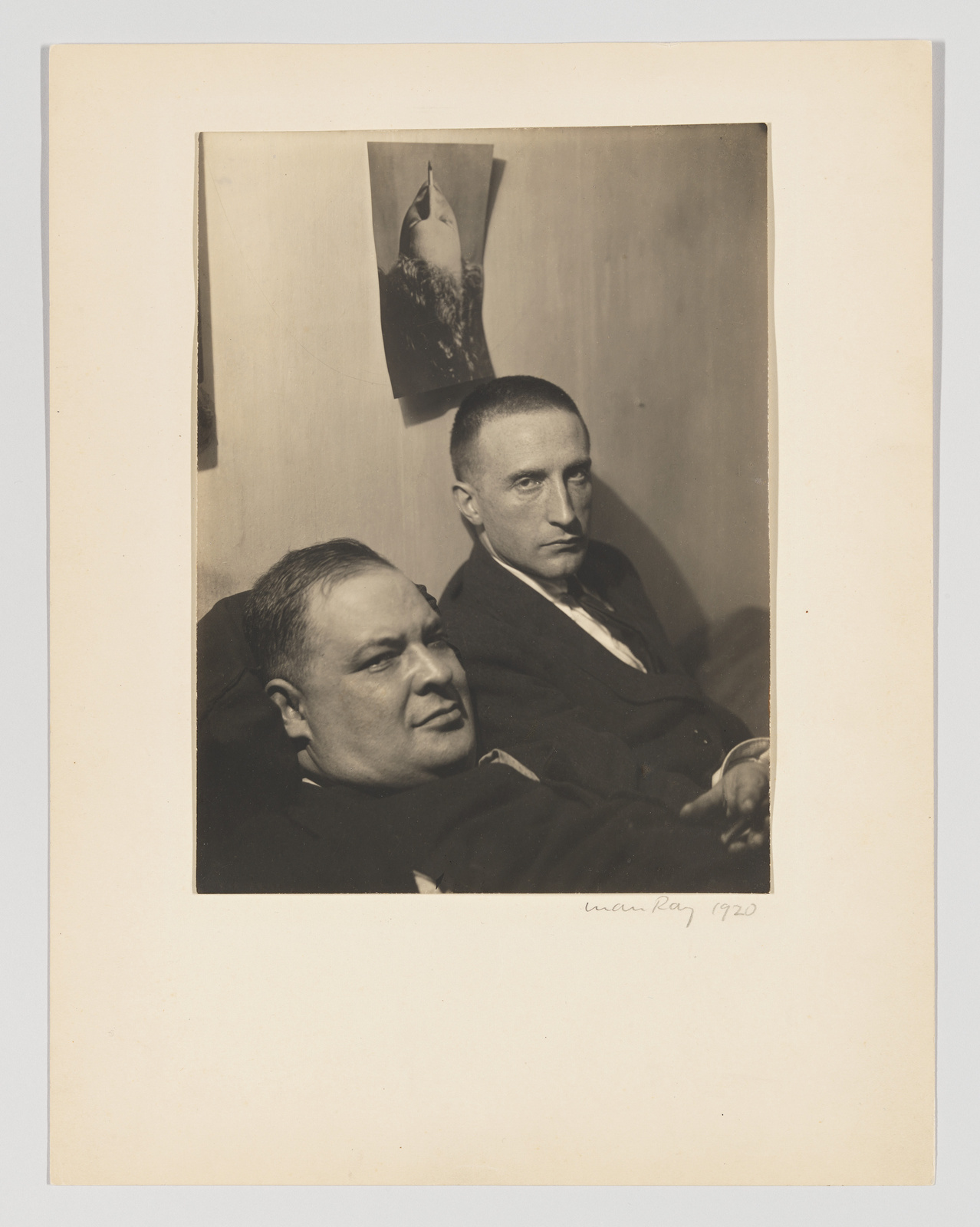

The first rayograph dates from 1922, soon after Man Ray arrived in Paris. Initially, he took photographs as a way to document his paintings, but he became increasingly interested in the possibilities of photography as a medium in its own right. His more experimental work, which utilized techniques such as solarization and double exposure, alternated with stylish and seductive fashion photography and incisive portraiture. Striking for their clear, bright lighting, unusual angles, and cropping, his close-up studio portraits of artists, writers, and musicians—including Pablo Picasso and Yves Tanguy, James Joyce and Aldous Huxley, Arnold Schoenberg and Igor Stravinsky—were in such demand that Man Ray had little time for painting during the 1920s. Yet today he is celebrated perhaps above all for his nudes. Whether their subjects—including Kiki de Montparnasse, Suzy Solidor, Jacqueline Goddard, Lee Miller, Meret Oppenheim, Ady Fidelin, and Nusch Éluard—are anonymous or named, the nudes are at once erotic and theatrical, the models apparently willing to collude with the photographer’s fantasy, which sometimes involved scenarios of a sadomasochistic nature. (The Marquis de Sade was one of Man Ray’s heroes.)

Richard Calvocoressi speaks about Man Ray’s Surrealist objects, including the 1921 work Cadeau ( Gift ), an iron with tacks glued to its plate

Many of the Surrealist objects produced by Man Ray exist in the form of replicas. Man Ray was not alone in reproducing his earlier work; René Magritte, for instance, painted copies or variations of certain key images throughout his career. But in Man Ray’s case the originals did not always survive, either because they were made of cheap materials and not designed to last—their ephemerality was part of the point—or because the artist would dismantle them after photographing them. Since he conscientiously photographed all of his work, it was possible to reconstruct these objects, and he had no compunction about doing so. In the 1960s and 1970s, limited editions of his best-known earlier pieces proliferated, suggesting a disregard on Man Ray’s part for their uniqueness. To give a few examples, Lampshade was originally conceived in 1919 in paper. A number of unique replicas and variants in metal or paper were made in subsequent years, culminating in the edition of 100 in painted aluminum published in Paris by Éditions MAT (founded by the Nouveau Reáliste artist Daniel Spoerri) in 1964. The anagrammatized Phare de la harpe (1967) is a variant of Man Ray’s famous Cadeau ( Gift , 1921), a flatiron with a row of tacks glued to the plate, which itself was reissued in a limited edition in 1970. The equally famous Object to Be Destroyed (1923), consisting of a metronome with a photograph of an eye attached, has a complicated history. In 1932, following the breakup of his affair with Lee Miller, Man Ray remade the work with Miller’s eye, titling it Object of Destruction. This version was destroyed, by a group of students, at an exhibition in Paris in 1956. Nine years later it was remade and editioned in Paris by MAT and retitled Indestructible Object ; and in 1970 and 1974 further editions were brought out in Turin and New York, respectively, under the title Perpetual Motif .

In the last example, the identity of the object shifts in response to changing circumstances. But, unlike the readymade, which is aesthetically neutral, or, in Duchamp’s own words, “visually indifferent,” the effect of the altered found object in Man Ray’s hands is that of an ingenious visual poem or pun; his titles, too, often include verbal puns. Pain peint, for example—a cast baguette painted blue—is a pun on the close aural similarity between the French for “bread” and “painted.” Sometimes Man Ray inscribed words on the object itself, as in Magritte’s paintings, wherein the relationship between an object, its representation, and its name is ambiguous or arbitrary. The title Featherweight, or Poids plume, deceives the spectator into thinking that the object weighs little, when in fact its painted lead base makes it surprisingly heavy.

Usually formed of two or more disparate elements assembled by the artist—a clay pipe and a blown glass bubble ( Ce qui manque à nous tous ), for example—Man Ray’s objects resemble games, puzzles, or toys: the concept of play was fundamental to his whole approach. They can be jokey, mysterious, or disturbing, as in L’énigme d’Isidore Ducasse (1920/1971). A classic example of the Surrealist idea of displacement, this work consists of a sewing machine wrapped in a blanket and tied with string, evoking the poet Ducasse’s unforgettable mental image of “the accidental encounter, on a dissecting table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella.” The addition of string or cord is typical of Man Ray. Vénus restaurée (1971; originally Torse , 1936), consisting of a plaster cast of the Medici Venus trussed up in rope, is even more suggestive of bondage. The ornamental wooden egg pierced by a knitting needle in Domesticated Egg (1944/1973) recalls the sadistic contraptions of Alberto Giacometti’s brief Surrealist phase. But on the whole the sexual content in Man Ray is joyful and uninhibited. “ Joie, jouer, jouir ” is how Duchamp summed up his anarchic and liberating art. 1

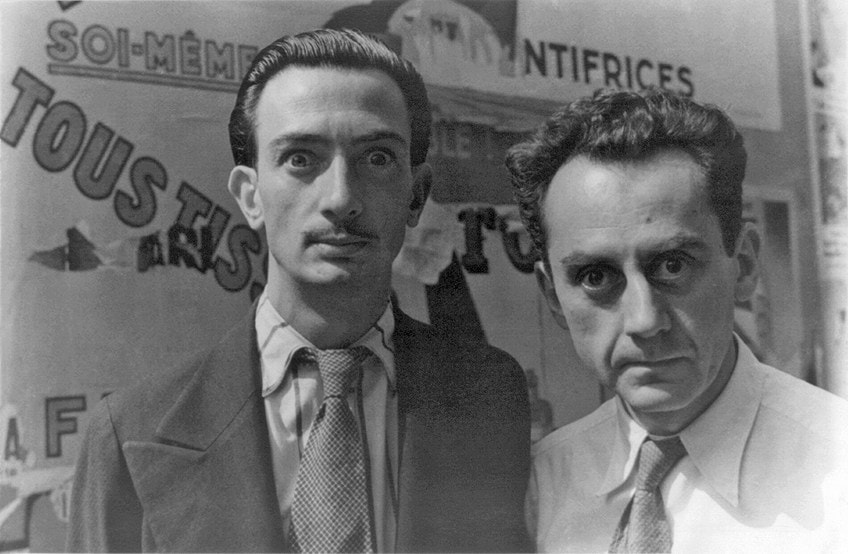

In Gagosian’s presentation of works by Man Ray at the 2018 Frieze Masters fair in London, six photographs by Lee Miller (1907–1977) joined a group of photographs by Man Ray from the period of their legendary collaboration (1929–32), including portraits by each of the other. 2 As a model for American Vogue , Miller was photographed by the leading fashion and portrait photographers of the day, including Edward Steichen. Knowing of her interest in photography, Steichen suggested to Miller that she make contact with Man Ray in Paris while she was visiting France and Italy in 1929. Thus it was that she became Man Ray’s pupil, assistant, collaborator, and, finally, lover—a relationship that was to last until her return to New York three years later. Man Ray was devastated when Miller left, incorporating images of her lips in his painting À l’heure de l’observatoire — les amoureux and one of her eyes in his Object of Destruction.

Richard Calvocoressi speaks about Man Ray’s collaboration with photographer Lee Miller

Miller later acknowledged that Man Ray had taught her everything: fashion, portraiture, “the whole technique of what he did.” Together they pioneered the technique of solarization—an exposure of the negative to a sudden flash of light during the developing process that sharpens contours and creates a halo or aura around objects. In 1931 she collaborated with Man Ray on his Electricité portfolio of ten rayographs commissioned by La Compagnie Parisienne de Distribution d’Électricité—a commission which she had persuaded him to accept. Otherwise Miller did not follow Man Ray down the route of formal experimentation but chose instead to reveal the world of people and objects in a more intense or startling way. Her most enduring images arose out of her work as a combat photographer with the US forces in Europe in World War II.

After she became the lover of Roland Penrose, the English Surrealist artist, exhibition organizer, writer, and collector, Miller reestablished her friendship with Man Ray, which lasted until his death. In 1937 Penrose, Miller, Man Ray, and his then lover Ady Fidelin holidayed in the South of France with Picasso, Dora Maar, and other friends. After the war, in 1955, Man Ray and his wife Juliet Browner went to stay with Miller and Penrose (by then married) at their home in Sussex. In 1975 Penrose organized the exhibition Man Ray: Inventor, Painter, Poet at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London and published a monograph on Man Ray’s work.

1 The author acknowledges the research of Edouard Sebline, published in the Sotheby’s Paris catalogues Modernités (October 19, 2017) and Collection Arthur Brandt (October 21, 2017).

2 Gagosian’s stand at Frieze Masters, curated by Max Teicher, Richard Calvocoressi, and Simon Stock, was awarded the Vetter’s Choice for late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century presentations.

Artwork © Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/ADAGP, Paris 2018; p hotos: Lucy Dawkins; videos: Emma Charles; Frieze Masters, Regent’s Park, London, October 4–7, 2018

Related Articles

A Flat on Rue Victor-Considerant

Lee Miller and Tanja Ramm’s friendship took them from New York to Paris and back, in front of and behind many cameras, and into the Surrealist avant-garde. Here, Gagosian director Richard Calvocoressi speaks with Ramm’s daughter, art historian Margit Rowell, about discovering her mother’s early life, her memories of Miller, and the collaborative work of photographers and models.

For Sale: Baby Shoes. Never Worn.

Sydney Stutterheim meditates on the power and possibilities of small-format artworks throughout time.

Now available Gagosian Quarterly Spring 2020

The Spring 2020 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #412 (2003) on its cover.

The Films of Man Ray: Mysterious Encounters of Realities and Dreams

Timothy Baum muses on Man Ray’s foray into filmmaking in the 1920s, the subject of the exhibition Man Ray: T he Mysteries of Château du Dé at Gagosian, San Francisco.

Now available Gagosian Quarterly Winter 2019

The Winter 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a selection from Christopher Wool’s Westtexaspsychosculpture series on its cover.

Gagosian Quarterly Talks Exiles in Paradise

Lawrence Weschler profiles the European exiles in Los Angeles during the 1930s and ’40s, examining how cultural visionaries, from Man Ray to Arnold Schoenberg, navigated the dramatic change in setting.

Man Ray’s LA

Timothy Baum explores this period of transition in response to an exhibition of Man Ray’s vintage gelatin silver photographs from his “Hollywood” period.

Gagosian Quarterly Spring 2018

The Spring 2018 Gagosian Quarterly with a cover by Ed Ruscha is now available for order.

Art and Food

Mary Ann Caws and Charles Stuckey discuss the presence of food and the dining table in the history of modern art.

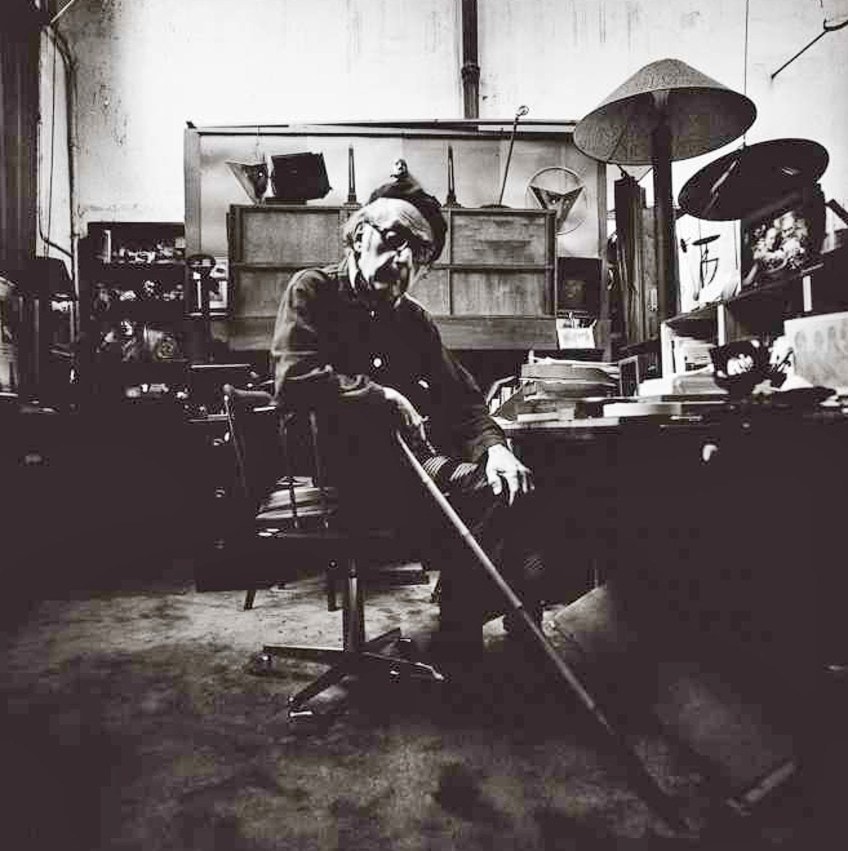

In the early 1980s, Ira Nowinski visited a studio frozen in time.

Sprayed: An Interview with Peter Stevens

Harnessing the gestural, unpredictable, projectile qualities of spray paint, artists have repurposed it as an alternative to the brush, to create hazy textures, drips, puddles, and graffiti-like text. Peter Stevens discusses this history of spray paint as an artistic medium with Alison McDonald.

David Cronenberg: The Shrouds

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in France. Film writer Miriam Bale reports on the motifs and questions that make up this latest addition to the auteur’s singular body of work.

Man Ray 1890–1976

Wikipedia entry, introduction.

Man Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitzky; August 27, 1890 – November 18, 1976) was an American visual artist who spent most of his career in Paris. He was a significant contributor to the Dada and Surrealist movements, although his ties to each were informal. He produced major works in a variety of media but considered himself a painter above all. He was best known for his pioneering photography, and was a renowned fashion and portrait photographer. He is also noted for his work with photograms, which he called "rayographs" in reference to himself.

Wikidata identifier

View the full Wikipedia entry

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed August 4, 2024.

Getty record

The influential and prolific American photographer and painter adopted the pseudonym Man Ray around 1909. He was a prominent force of Dada and Surrealism, and the only American to play a significant role in the development of those movements. His visits to Alfred Stieglitz's gallery, 291 introduced him to a wide variety of European contemporary artists, such as Picasso, Rodin, and Braque. Like many other artists of his time, he was also greatly influenced by the avant-garde Armory show in New York City in 1913. His paintings from this period show his fascination with the flatness of Modernism and his interest in the patterns of shapes rather than a realistic rendering of subject matter. During his trip to Paris in 1921, Man Ray began to experiment with photography, and may have been introduced to the photogram by Tristan Tzara. He adopted the method and called his works "rayographs," photographic images composed of ordinary objects placed on photo sensitive paper exposed to light. Together with his muse Lee Miller, he developed the solarization process which he used in his fashion and nude photography. With the onset of World War II, he lived in California and concentrated on painting and making objects. He returned to Paris in 1951, where he remained until his death. Man Ray was one of the first artists to make photographs seen as important works of art, equal to that of painting and sculpture.

Country of birth

United States

Artist, assemblage artist, cinematographer, engraver, landscapist, painter, photographer, sculptor

ULAN identifier

Man Ray, Man Rei, Emmanuel Radenski, Emmanuel Radensky, Emmanuel Radnitsky, Emmanuel Radnitzky, Ray [rejected], Emmanuel Rudnitsky, Emmanuel Rudnitzky, Emmanuel Rudnizky, マン·レイ

View the full Getty record

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License . Accessed August 4, 2024.

e.g. oil on canvas

e.g. gift of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney

Invalid year range

Years must be in the form YYYY

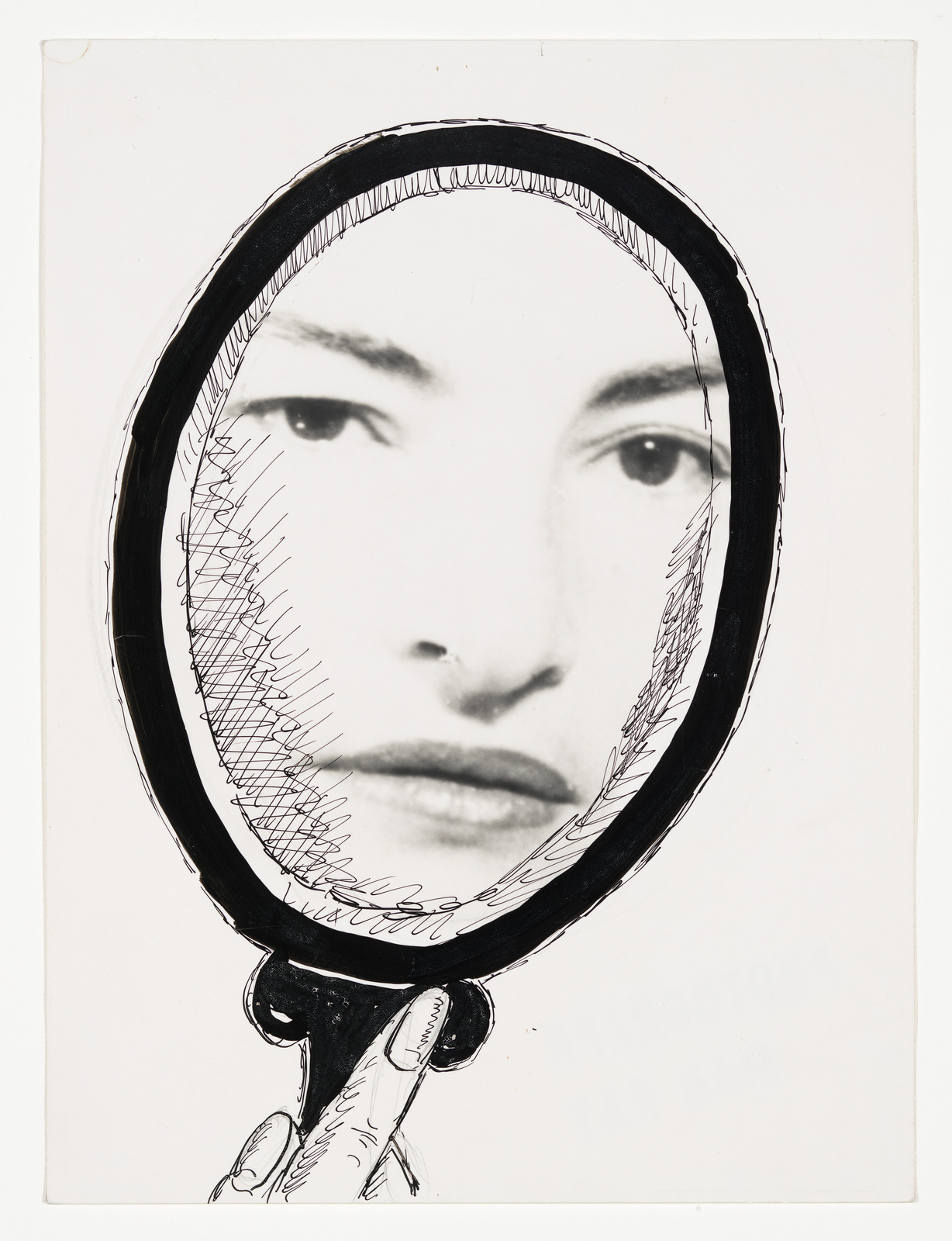

Man Ray Juliet in the Mirror c. 1940s

On view Floor 7

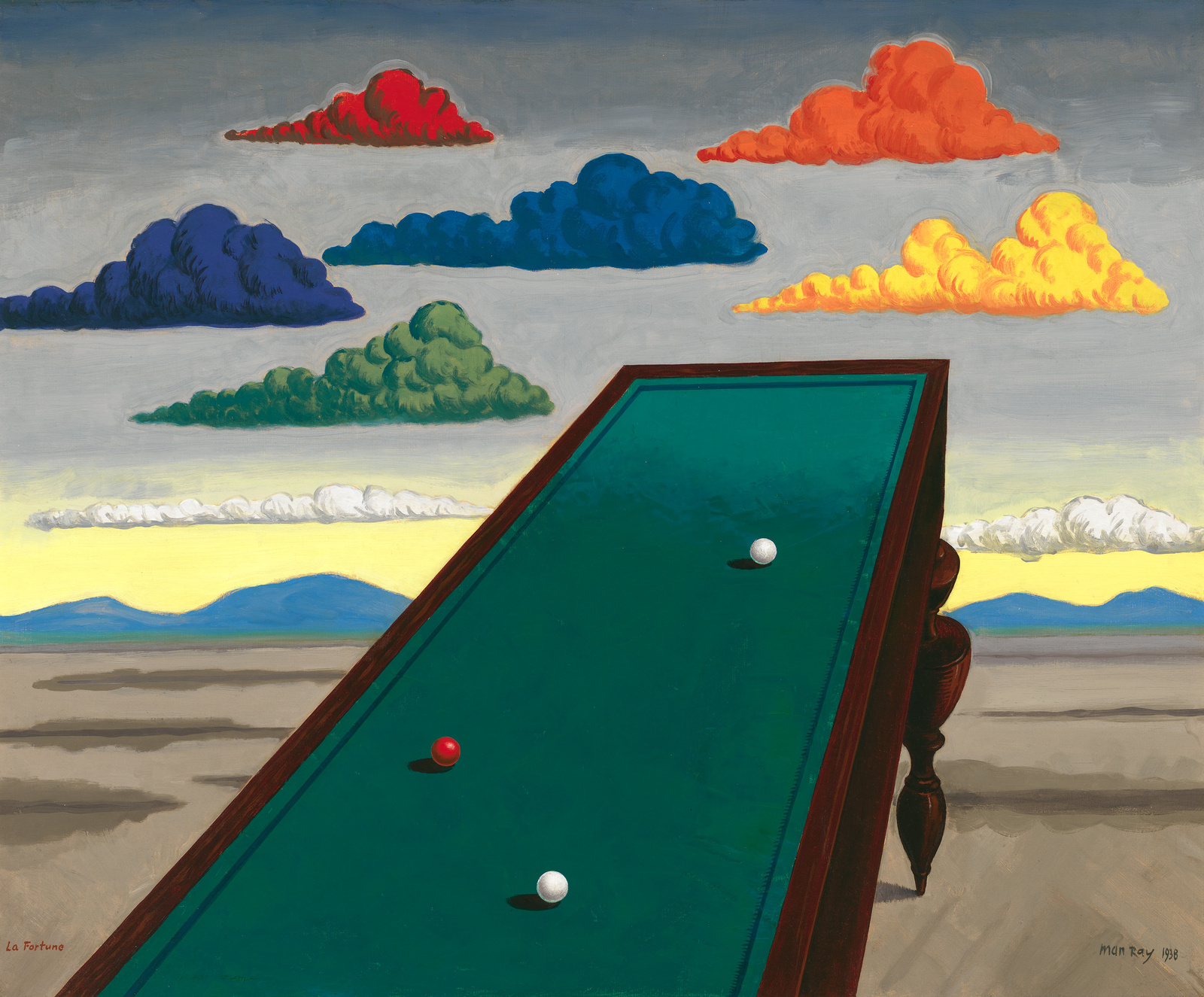

Man Ray La Fortune 1938

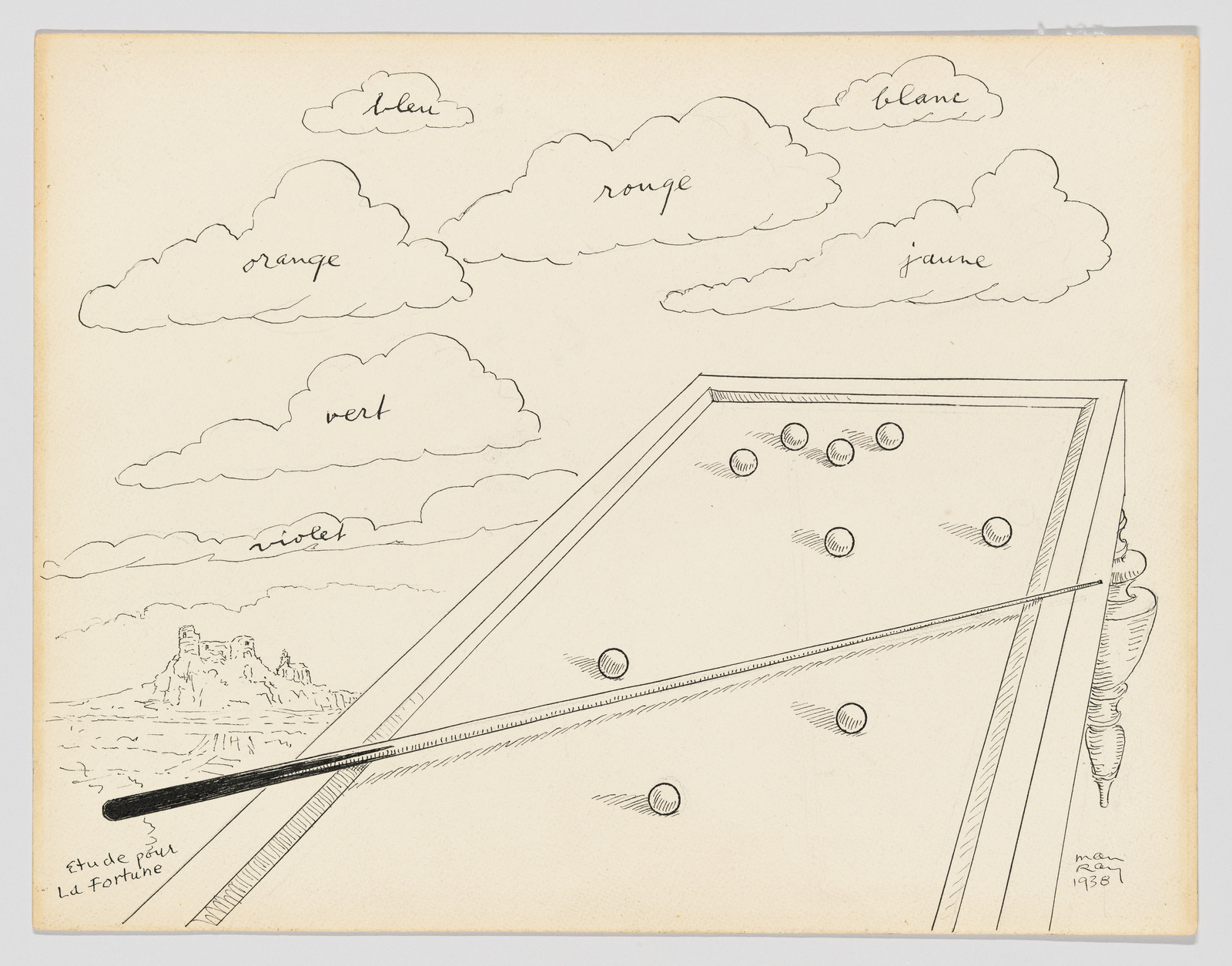

Man Ray Etude Pour La Fortune 1938

Man Ray Erotique Voilee 1933

Man Ray Untitled 1931

Man Ray Mime 1926

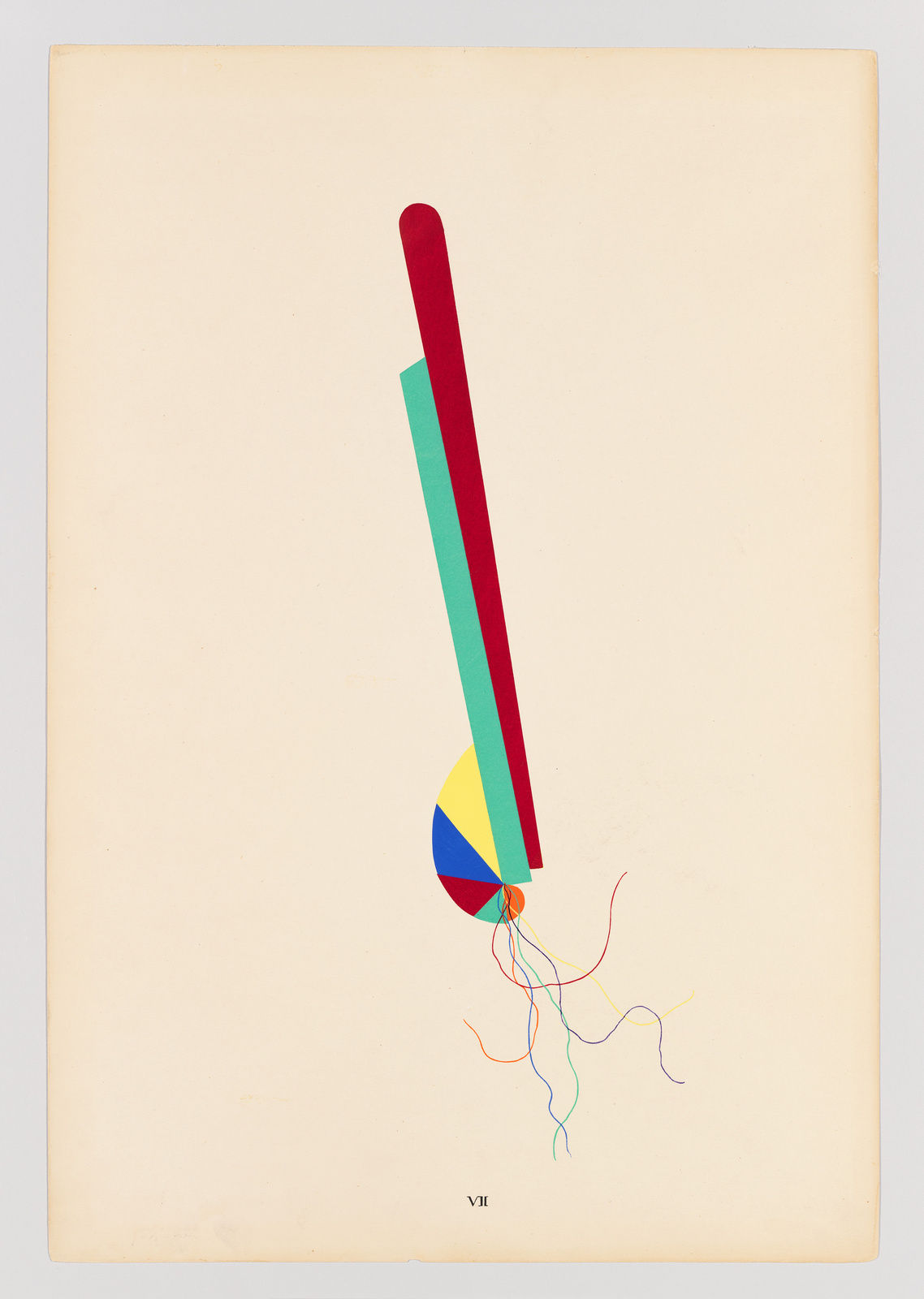

Man Ray Long Distance 1926

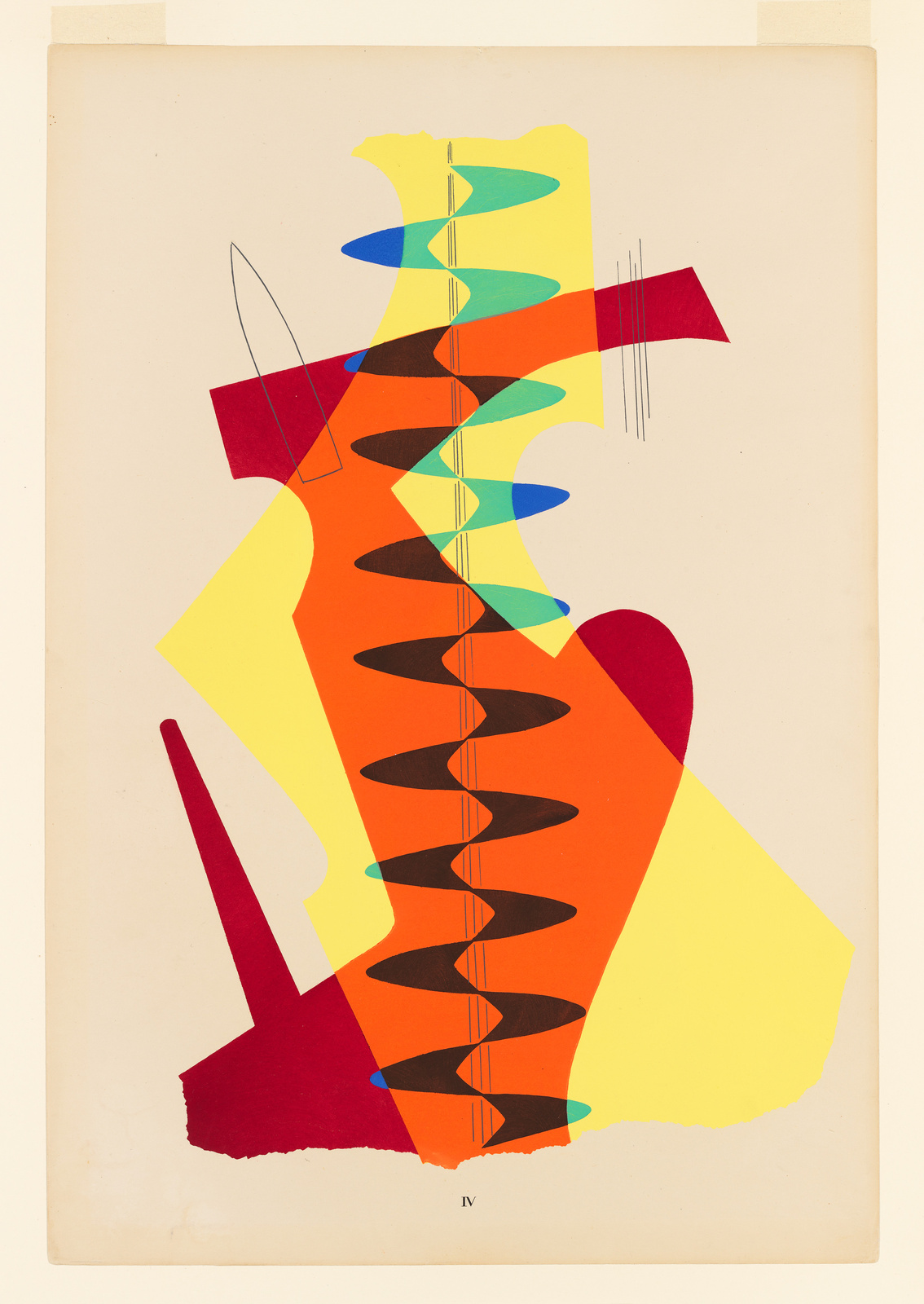

Man Ray Orchestra 1926

Man Ray The Meeting 1926

Man Ray Legend 1926

Man Ray Decanter 1926

Man Ray Jeune fille 1926

Man Ray Shadows 1926

Man Ray Concrete Mixer 1926

Man Ray Dragonfly 1926

Man Ray Rayograph 1924

Man Ray Contrasted Circular Forms with Pair of Optical Black Dots 1923

Man Ray Objet indestructible 1923/1965

Man Ray Metal Laboratory Objects 1922

Man Ray Joseph Stella and Marcel Duchamp 1920

Man Ray New York 1917/1966

Man Ray IV The Meeting 1916–1917

Man Ray Five Figures 1914

Man Ray Woman Asleep 1913

Exhibitions

At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism

May 7, 2022–Feb 26, 2023

The Whitney’s Collection: Selections from 1900 to 1965

Nick Mauss: Transmissions

Mar 16–May 14, 2018

Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection

Apr 2, 2016–Apr 2, 2017

The Whitney's Collection

Sept 28, 2015–Apr 4, 2016

America Is Hard to See

May 1–Sept 27, 2015

Real/Surreal

Oct 6, 2011–Feb 12, 2012

Breaking Ground: The Whitney’s Founding Collection

Apr 28–Sept 18, 2011

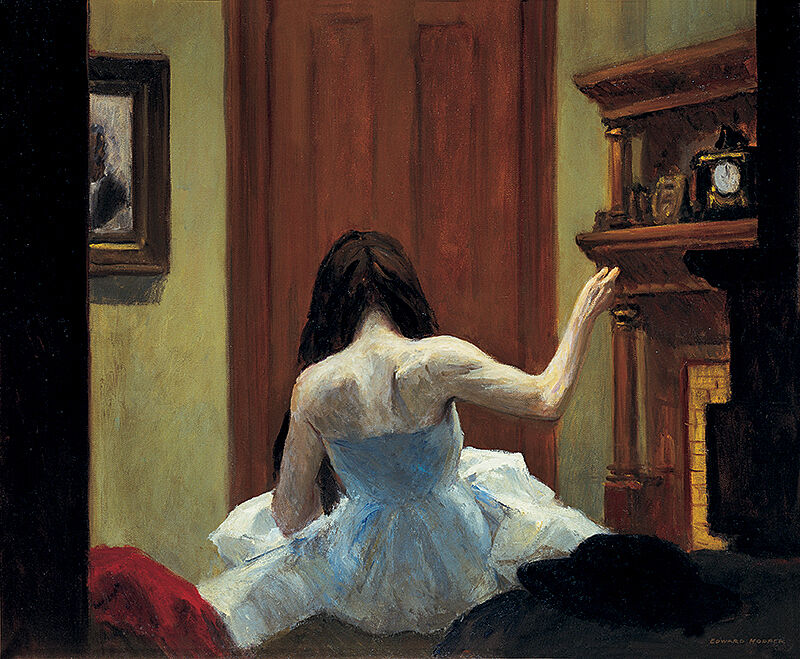

Modern Life: Edward Hopper and His Time

Oct 28, 2010–Apr 10, 2011

Picasso and American Art

Sept 28, 2006–Jan 28, 2007

Full House: Views of the Whitney’s Collection at 75

June 29–Sept 3, 2006

Highlights from the Permanent Collection: From Hopper to Mid-Century

Feb 25, 2000–May 20, 2006

Human Interest: K8 Hardy on Sturtevant

Surreal World

- Images & permissions

- Open access

A 30-second online art project: Peter Burr, Sunshine Monument

Learn more at whitney.org/artport

Man Ray, The Gift

Man Ray, Gift , c. 1958 (replica of 1921 original), painted flatiron and tacks, 15.3 x 9 x 11.4 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Man Ray and The Gift

The American artist Man Ray (born Emanuel Radnitzky) arrived in Paris in 1921. Within a year, the artist had his first solo show at a Parisian gallery. Among the works he exhibited was one unlisted sculpture: the object, which he called The Gift , was an everyday flatiron with brass tacks glued in a column down its center. According to Man Ray in his autobiography Self-Portrait , the object was made quickly, in a bout of inspiration, the day of the gallery opening.

Samuel Kravitt, A Sister’s Hands Ironing , c. 1931-36, photo, Hancock Shaker Village, Massachusetts (Library of Congress)

What do we make of Man Ray’s relatively simple, yet subversive act of presenting a modified household appliance as a work of art? The flatiron – intended to smooth wrinkles from fabric – has been rendered useless with the addition of a row of brass tacks. We are perhaps expected to react the way the store owner supposedly did when Man Ray purchased these items, by exclaiming, “But you’ll ruin the shirt if you put tacks there!”

Dada, or the nonsense of the everyday

Before arriving in Paris, Man Ray was associated with the New York Dada group, which included the artist Marcel Duchamp. As a loosely-affiliated group of like-minded artists, they were particularly interested in using humor and antagonism to question the definition of a work of art. Re-defining art was prevalent in Duchamp’s Readymades, such as his Bicycle Wheel , a sculpture made by conjoining a bicycle wheel and a stool, two utilitarian objects.

The Surrealist object

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel , 1951 (third version, after lost original of 1913), metal wheel mounted on painted wood stool, 129.5 x 63.5 x 41.9 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Although made in the spirit of Dada, Man Ray’s The Gift prefigured by several years a key artistic practice that would develop within the Surrealist movement: the “Surrealist object,” a type of three-dimensional art work that included found objects, modified objects, and sculpted objects.

The Surrealist object—one of many literary and visual practices in the movement—became prominent beginning in 1936, after its association with a series of extravagant international expositions organized in London and Paris. Surrealism had been first publicly announced in 1924, with the publication of André Breton’s first “Manifesto of Surrealism.” Stridently activist, Surrealists sought to release society from cultural constraints and the need to conform to social norms, which they felt curtailed people’s desires to live as they wished.

Function/Dysfunction

Of the many types of Surrealist objects that were produced, two important features are present in Man Ray’s The Gift . First, an everyday object has been changed so that its original function is denied. Indeed, the artist’s relatively simple addition of tacks transforms a useful device into a destructive one.

Second, Man Ray’s alteration gives a common object a symbolic function. The flatiron, associated with social expectations of propriety and middle-class values, becomes a subversive attack on social expectations. Even if Man Ray’s tack-lined iron is no longer used for pressing clothes, the object resonates with ruinous, violent possibilities.

Denial and destruction

While denial and destruction are qualities are not intrinsic to all Surrealist art, there are striking examples, like The Gift , that show Surrealists working with banal objects to question the viewer’s expectations, and force us to re-evaluate the function of those objects in our lives.

Wolfgang Paalen, Articulated Cloud , umbrella in foam, 1938

Wolfgang Paalen’s work from 1938, Articulated Cloud , an umbrella crafted from spongy foam, denies the object’s intended function by causing water to be absorbed rather than repelled. It also makes the umbrella rather useless for anyone seeking shelter from rain.

Man Ray, Indestructible Object (or Object to Be Destroyed) , 1964 (replica of 1923 original), metronome with cutout photograph of eye on pendulum, 22.5 x 11 x 11.6 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Another object by Man Ray—a metronome with a photograph of a woman’s open eye clipped to it—adds an ominous sense of relentless observation to an ordinary musician’s timing instrument. Man Ray’s title of the piece, Object to Be Destroyed , seems mysterious at first. But when we consider the psychological effects of such obsessive observation—and think about what kind of impulses such regulations might evoke – the artist’s title becomes easier to understand.

No longer a simple time-keeping device, Object To Be Destroyed summons feelings of irritation over being watched, and powerlessness in the face of endless time. There is no means to stop the cycle, except to destroy the object itself.

Don’t touch the art!

The violent implications of The Gift and other Surrealist objects by Man Ray came to fruition in 1957 when Object to Be Destroyed was lost during a Man Ray retrospective. Varying stories exist as to the fate of the sculpture. In his autobiography, Man Ray recounts that a group of students visited the exhibition and caused a scene, during which one of them walked off with the sculpture, and it was never seen again. Numerous historians, however, state that during the exhibition one of the students took the title literally and smashed it with a hammer.

Whether stolen or smashed, Object to Be Destroyed no longer existed. This compelled Man Ray to remake the sculpture, but he pointedly changed the title to Indestructible Object .

Bibliography

Andre Breton, First Manifesto of Surrealism , 1924

Man Ray; Prophet of the Avant-Garde, American Masters Series on PBS.org (September 17th, 2005)

Alias Man Ray: The Art of Reinvention , Exhibition at The Jewish Museum (November 15, 2009 – March 14, 2010)

Important fundamentals

Read Surrealism, an introduction

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Visit Planning

- Plan Your Visit

- Event Calendar

- Current Exhibitions

- Family Activities

- Guidelines and Policies

Access Programs

- Accessibility

- Dementia Programs

- Verbal Description Tours

Explore Art and Artists

Collection highlights.

- Search Artworks

- New Acquisitions

- Search Artists

- Search Women Artists

Something Fun

- Which Artist Shares Your Birthday?

Exhibitions

- Upcoming Exhibitions

- Traveling Exhibitions

- Past Exhibitions

Art Conservation

- Lunder Conservation Center

Research Resources

- Research and Scholars Center

- Nam June Paik Archive Collection

- Photograph Study Collection

- National Art Inventories Databases

- Save Outdoor Sculpture!

- Researching Your Art

Publications

- American Art Journal

- Toward Equity in Publishing

- Catalogs and Books

- Scholarly Symposia

- Publication Prizes

Fellows and Interns

- Fellowship Programs

- List of Fellows and Scholars

- Internship Programs

Featured Resource

- Support the Museum

- Corporate Patrons

- Gift Planning

- Donating Artworks

- Join the Director's Circle

- Join SAAM Creatives

Become a member

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy . We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.

MAN RAY’S EARLY PAINTINGS 1913–1916: THEORY AND PRACTICE IN THE ART OF TWO DIMENSIONS

- Share on Facebook

- Show more sharing options

- Share on WhatsApp

- Print This Page

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share to Flipboard

- Submit to Reddit

- Post to Tumblr

He who resolves never to ransack any mind but his own, will soon be reduced, from mere barrenness, to the poorest of all imitations; he will be obliged to imitate himself, and to repeat what he has before often repeated.

to Students of the Royal Academy,

December 10, 1774

The following year, 1914, saw the creation of Ray’s largest Cubist picture, War (AD MCMXIV) , measuring nearly six feet in width. The soldiers and horses portrayed in this painting are rendered in bulky, overbearing cylindrical forms, seemingly frozen into positions of perpetual combat. While the subject was undoubtedly suggested by the outbreak of war in Europe, Ray claims the inspiration came from reproductions he had seen of Uccello’s famous battle scenes, and, in fact, reference to Renaissance painting is extended to the media employed; the canvas was prepared with fish glue and plaster dissolved in water, to give the general appearance of fresco. 4 But here the comparison with Renaissance painting ends, for unlike Uccello’s paintings, in which all details are subjected to rigid perspectival schema, Ray’s figures are rendered within a sharply defined two-dimensional framework. This approach to the rendition of form differs markedly from the fragmented, intersecting planes in his Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz , a stylistic departure indicative of the direction his painting was to take.

This was a crucial period in Ray’s development toward a more abstract painting. Fifty years later he tried to explain the reasoning behind it. Describing the painting War , he wrote in his autobiography, “I myself had been fascinated by perspective . . . In my paintings [as opposed to his architectural studies], however, I never forgot that I was working on a two-dimensional surface which for the sake of a new reality I would not violate, or as little as possible.” Ray wrote his autobiography in the early ’60s, and it is clear that the wording of this statement was informed by the formalist rhetoric that developed only in the ’40s and ’50s, in the heyday of the Abstract Expressionist period. Nevertheless, as the immediate evolution of his painting indicated, and as the publication of his pamphlet on two-dimensional design later confirmed, Ray was indeed in the process of initiating a change in style that found theoretical support in a fully developed and remarkably early formalist program.

According to his own account, the change can be traced to the time of a camping trip he took to Harriman State Park in New York in the autumn of 1914. Accompanied by his wife, the poet Adon Lacroix, and two other couples, including the occasional poet Alison Hartpence and his wife Helen, Ray set out on a three-day hiking trip through the Ramapo Hills on the New York-New Jersey border. During a conversation with Hartpence on the last day of this outing Ray announced that he planned to execute a series of imaginary landscapes inspired by his trip in the country, but that after that he would no longer paint from nature, which he concluded was only “a hindrance to really creative work.” Instead, he informed his friend, he planned to “. . . turn more and more to man made sources.” And, indeed, by the first few months of 1915 this radical departure manifested itself in a series of still lifes and figure studies executed in the new “flattened manner.” As he explained it in his autobiography:

I changed my style completely, reducing human figures to flat-patterned disarticulated forms. I painted some still-lifes also in flat subdued colors, carefully choosing subjects that in themselves had no aesthetic interest. All idea of composition as I had been concerned with it previously, through my earlier training, was abandoned, and replaced with an idea of cohesion, unity and a dynamic quality as in a growing plant. This I felt, more than actually analyzed . . .

Despite the intuitive approach he claimed, Ray’s new paintings were actually tightly organized compositions, whose calculated designs reveal a well-thought-out analysis of internal forms. In a still life appropriately entitled Arrangement of Forms, No. 1 , a bowl, a covered jar, and a candlestick are so thoroughly fused with the surrounding space and background plane that the viewer is naturally compelled to a reading of the forms in relation to the painting’s overall surface quality. All shading and modeling have been eliminated, and, by means of translucent, overlapping forms, even the recessional edges of the table top are incorporated within a reading of the painting’s two-dimensional framework.

This tendency to flatten the internal forms of compositions, which Paul Wescher likened to a slowly deflating tire, 5 was further intensified in the artist’s first use of collage and collage-related techniques. Ray had recently been exposed to the possibilities of this medium through the Picasso/Braque exhibition at 291, held from December 9, 1914, through January 11, 1915. The effect of these collages coincided exactly with Ray’s formalist concerns: the flat, rectangular pieces of paper reasserted the pictures’ surfaces, forcing a reading of all elements within each pictorial field in relation to the inherent two-dimensional quality of the paintings or drawings. Ray was especially impressed by the sparsity of detail in Picasso’s work: “The stark-black charcoal lines of Picasso with here and there a piece of newspaper pasted on seemed very daring—rather incomprehensible though.” Whether or not he fully understood the implications of this new medium, he quickly proceeded to make use of it.

Ray’s first documented use of collage was in 1914, when he accentuated the torso of a small figure with a piece of gold paper in Chinese Restaurant . Interior , 1915, his first important work in collage, incorporates a thin, rectangular sheet of silvered paper, mounted at a slight angle in the center of the composition. Carl Belz, author of an article that was perhaps the first probing analysis of Ray’s paintings from this period, attributes the apparent contradictions of Interior to “Dada games.” 6 Prompted by the portrayal of a clock weight hanging from a chain in the center of the composition, Belz interprets the number boldly inscribed on the left—“1000”—as an indication of a precise hour: “10 o’clock.” If this number refers instead to the year 1000, then this inscription may not be a totally illogical element. It may refer to 1000 A.D., a date feared by Europeans in the Middle Ages, for it was predicted that on that date the world would come to an end. Ray may have known this historical fact, and by incorporating a reference to war in the same image, he may have been suggesting that the war in Europe would be the modern cause of universal devastation. The clock mechanism then would be an indication that the coming of the end of the world was just a matter of time.

Several of the details in Interior are borrowed from an earlier work; the large, white, heavily outlined form in the background is derived from the horse and rider that appear in the left portion of War , while it has been noted that the three figures on the silvered paper are suggested by other details from this same painting. Thus, like Picasso’s use of newspaper fragments, in strictly formal terms Ray too incorporates into his composition details which assert an inherent two-dimensional quality. However, rather than literally include elements from his environment, he adapts figurative details that have already undergone the flattening process in his earlier work. As Adon Lacroix succinctly put it later in a 1917 catalogue introduction to her husband’s work, “. . . a picture includes a painting and a painting includes a picture and one is both and both are one. The pervading subject in everything is the idea.” From 1914 to 1916 Man Ray explored the full ramifications of the idea of two-dimensionality in an important series of paintings, collages, and collage-inspired paintings.

By the fall of 1915 Ray had prepared enough works in this style for a one-man show at the recently opened Daniel Gallery, located at 47th Street and Fifth Avenue, then the center of New York’s exclusive art gallery district. Daniel, an ex-saloon keeper, was hesitant to assume the expense of framing all the canvases Ray brought in, so the young artist came up with a solution in keeping with his concern for flatness. The paintings were recessed into a temporary wall surface constructed of cheesecloth, making it look as though they had been painted directly on the wall. Of the thirty paintings shown, six were entitled simply Study in Two Dimensions , making it clear that the artist was intent on emphasizing flatness. In fact, it was precisely this theme that most confounded reviewers of the exhibition, who tended to classify the two-dimensional studies with the design experiments of an art student.

Ray recalled that most reviews of this exhibition were “deprecatory or outrightly hostile.” Conservative critics preferred the earlier, more representational portraits and landscapes, which they cited as proof that the artist could paint with skill if he really wanted to. And, as an example of the opposing extreme, they repeatedly singled out his Dance-Interpretation (as it was then entitled), probably because it was conveniently reproduced in the small catalogue accompanying the exhibition. One critic described the painting as “some tailor’s patterns . . . having a good time,” 7 while an anonymous reviewer in the New York Sun made a far more insightful observation: “Mr. Ray appears to have cut certain shapes of dancing figures from a paper roughly. Then he cut the figures again into careless segments and pasted the whole together in fine disregard of the original shapes.” 8 Whether or not Ray constructed this particular work in the fashion described by this reviewer is uncertain, but the analysis is keenly prophetic, in that it describes precisely the technique Ray was to use the very next year in his most important paintings.

This same reviewer in the Sun also thought Ray’s landscapes noteworthy for their “undeniable charm,” but rightly observed that the real purpose of the exhibition was “. . . evidently to test the larger, two dimensional canvases with the public.” In this light there follows an analysis of Ray’s Dance , comparing its two-dimensional quality with Picasso’s presumed use of a fourth:

Our artist [Ray] instead of using the four dimensions of Mr. Picasso uses but two, but art in two dimensions is even more intricate than in four . . . Picasso is always concerned with form and that thing more than form that gives the fourth dimension, but these dancers of Mr. Ray are of tissue paper thinness. They have width and height only.

This reviewer then notes that this flattening effect can be of some value, and proceeds to establish a connection with the art of the past:

. . . from the mural point of view the two dimensions are theoretically more correct than the four that are used by Picasso. The great success of Puvis lay in his ability to keep his great wall spaces flat. What is fair for classic art is fair for the moderns.