Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

Published on September 15, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on July 18, 2023.

Recommendations in research are a crucial component of your discussion section and the conclusion of your thesis , dissertation , or research paper .

As you conduct your research and analyze the data you collected , perhaps there are ideas or results that don’t quite fit the scope of your research topic. Or, maybe your results suggest that there are further implications of your results or the causal relationships between previously-studied variables than covered in extant research.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What should recommendations look like, building your research recommendation, how should your recommendations be written, recommendation in research example, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about recommendations.

Recommendations for future research should be:

- Concrete and specific

- Supported with a clear rationale

- Directly connected to your research

Overall, strive to highlight ways other researchers can reproduce or replicate your results to draw further conclusions, and suggest different directions that future research can take, if applicable.

Relatedly, when making these recommendations, avoid:

- Undermining your own work, but rather offer suggestions on how future studies can build upon it

- Suggesting recommendations actually needed to complete your argument, but rather ensure that your research stands alone on its own merits

- Using recommendations as a place for self-criticism, but rather as a natural extension point for your work

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

There are many different ways to frame recommendations, but the easiest is perhaps to follow the formula of research question conclusion recommendation. Here’s an example.

Conclusion An important condition for controlling many social skills is mastering language. If children have a better command of language, they can express themselves better and are better able to understand their peers. Opportunities to practice social skills are thus dependent on the development of language skills.

As a rule of thumb, try to limit yourself to only the most relevant future recommendations: ones that stem directly from your work. While you can have multiple recommendations for each research conclusion, it is also acceptable to have one recommendation that is connected to more than one conclusion.

These recommendations should be targeted at your audience, specifically toward peers or colleagues in your field that work on similar subjects to your paper or dissertation topic . They can flow directly from any limitations you found while conducting your work, offering concrete and actionable possibilities for how future research can build on anything that your own work was unable to address at the time of your writing.

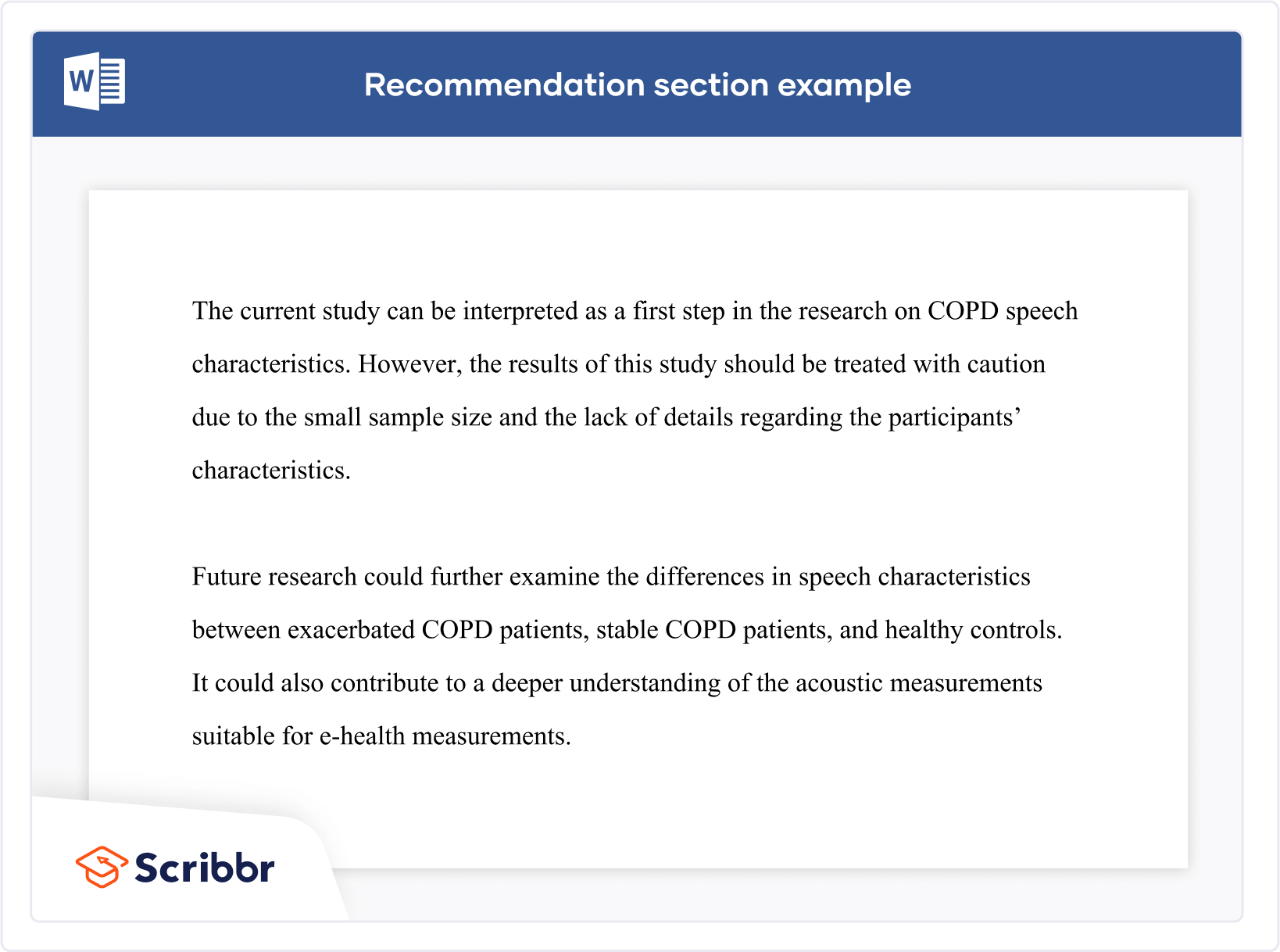

See below for a full research recommendation example that you can use as a template to write your own.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

While it may be tempting to present new arguments or evidence in your thesis or disseration conclusion , especially if you have a particularly striking argument you’d like to finish your analysis with, you shouldn’t. Theses and dissertations follow a more formal structure than this.

All your findings and arguments should be presented in the body of the text (more specifically in the discussion section and results section .) The conclusion is meant to summarize and reflect on the evidence and arguments you have already presented, not introduce new ones.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation should include the following:

- A restatement of your research question

- A summary of your key arguments and/or results

- A short discussion of the implications of your research

For a stronger dissertation conclusion , avoid including:

- Important evidence or analysis that wasn’t mentioned in the discussion section and results section

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion …”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g., “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, July 18). How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/recommendations-in-research/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, how to write a results section | tips & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Recommendations – Examples and Writing Guide

Research Recommendations – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Recommendations

Definition:

Research recommendations refer to suggestions or advice given to someone who is looking to conduct research on a specific topic or area. These recommendations may include suggestions for research methods, data collection techniques, sources of information, and other factors that can help to ensure that the research is conducted in a rigorous and effective manner. Research recommendations may be provided by experts in the field, such as professors, researchers, or consultants, and are intended to help guide the researcher towards the most appropriate and effective approach to their research project.

Parts of Research Recommendations

Research recommendations can vary depending on the specific project or area of research, but typically they will include some or all of the following parts:

- Research question or objective : This is the overarching goal or purpose of the research project.

- Research methods : This includes the specific techniques and strategies that will be used to collect and analyze data. The methods will depend on the research question and the type of data being collected.

- Data collection: This refers to the process of gathering information or data that will be used to answer the research question. This can involve a range of different methods, including surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments.

- Data analysis : This involves the process of examining and interpreting the data that has been collected. This can involve statistical analysis, qualitative analysis, or a combination of both.

- Results and conclusions: This section summarizes the findings of the research and presents any conclusions or recommendations based on those findings.

- Limitations and future research: This section discusses any limitations of the study and suggests areas for future research that could build on the findings of the current project.

How to Write Research Recommendations

Writing research recommendations involves providing specific suggestions or advice to a researcher on how to conduct their study. Here are some steps to consider when writing research recommendations:

- Understand the research question: Before writing research recommendations, it is important to have a clear understanding of the research question and the objectives of the study. This will help to ensure that the recommendations are relevant and appropriate.

- Consider the research methods: Consider the most appropriate research methods that could be used to collect and analyze data that will address the research question. Identify the strengths and weaknesses of the different methods and how they might apply to the specific research question.

- Provide specific recommendations: Provide specific and actionable recommendations that the researcher can implement in their study. This can include recommendations related to sample size, data collection techniques, research instruments, data analysis methods, or other relevant factors.

- Justify recommendations : Justify why each recommendation is being made and how it will help to address the research question or objective. It is important to provide a clear rationale for each recommendation to help the researcher understand why it is important.

- Consider limitations and ethical considerations : Consider any limitations or potential ethical considerations that may arise in conducting the research. Provide recommendations for addressing these issues or mitigating their impact.

- Summarize recommendations: Provide a summary of the recommendations at the end of the report or document, highlighting the most important points and emphasizing how the recommendations will contribute to the overall success of the research project.

Example of Research Recommendations

Example of Research Recommendations sample for students:

- Further investigate the effects of X on Y by conducting a larger-scale randomized controlled trial with a diverse population.

- Explore the relationship between A and B by conducting qualitative interviews with individuals who have experience with both.

- Investigate the long-term effects of intervention C by conducting a follow-up study with participants one year after completion.

- Examine the effectiveness of intervention D in a real-world setting by conducting a field study in a naturalistic environment.

- Compare and contrast the results of this study with those of previous research on the same topic to identify any discrepancies or inconsistencies in the findings.

- Expand upon the limitations of this study by addressing potential confounding variables and conducting further analyses to control for them.

- Investigate the relationship between E and F by conducting a meta-analysis of existing literature on the topic.

- Explore the potential moderating effects of variable G on the relationship between H and I by conducting subgroup analyses.

- Identify potential areas for future research based on the gaps in current literature and the findings of this study.

- Conduct a replication study to validate the results of this study and further establish the generalizability of the findings.

Applications of Research Recommendations

Research recommendations are important as they provide guidance on how to improve or solve a problem. The applications of research recommendations are numerous and can be used in various fields. Some of the applications of research recommendations include:

- Policy-making: Research recommendations can be used to develop policies that address specific issues. For example, recommendations from research on climate change can be used to develop policies that reduce carbon emissions and promote sustainability.

- Program development: Research recommendations can guide the development of programs that address specific issues. For example, recommendations from research on education can be used to develop programs that improve student achievement.

- Product development : Research recommendations can guide the development of products that meet specific needs. For example, recommendations from research on consumer behavior can be used to develop products that appeal to consumers.

- Marketing strategies: Research recommendations can be used to develop effective marketing strategies. For example, recommendations from research on target audiences can be used to develop marketing strategies that effectively reach specific demographic groups.

- Medical practice : Research recommendations can guide medical practitioners in providing the best possible care to patients. For example, recommendations from research on treatments for specific conditions can be used to improve patient outcomes.

- Scientific research: Research recommendations can guide future research in a specific field. For example, recommendations from research on a specific disease can be used to guide future research on treatments and cures for that disease.

Purpose of Research Recommendations

The purpose of research recommendations is to provide guidance on how to improve or solve a problem based on the findings of research. Research recommendations are typically made at the end of a research study and are based on the conclusions drawn from the research data. The purpose of research recommendations is to provide actionable advice to individuals or organizations that can help them make informed decisions, develop effective strategies, or implement changes that address the issues identified in the research.

The main purpose of research recommendations is to facilitate the transfer of knowledge from researchers to practitioners, policymakers, or other stakeholders who can benefit from the research findings. Recommendations can help bridge the gap between research and practice by providing specific actions that can be taken based on the research results. By providing clear and actionable recommendations, researchers can help ensure that their findings are put into practice, leading to improvements in various fields, such as healthcare, education, business, and public policy.

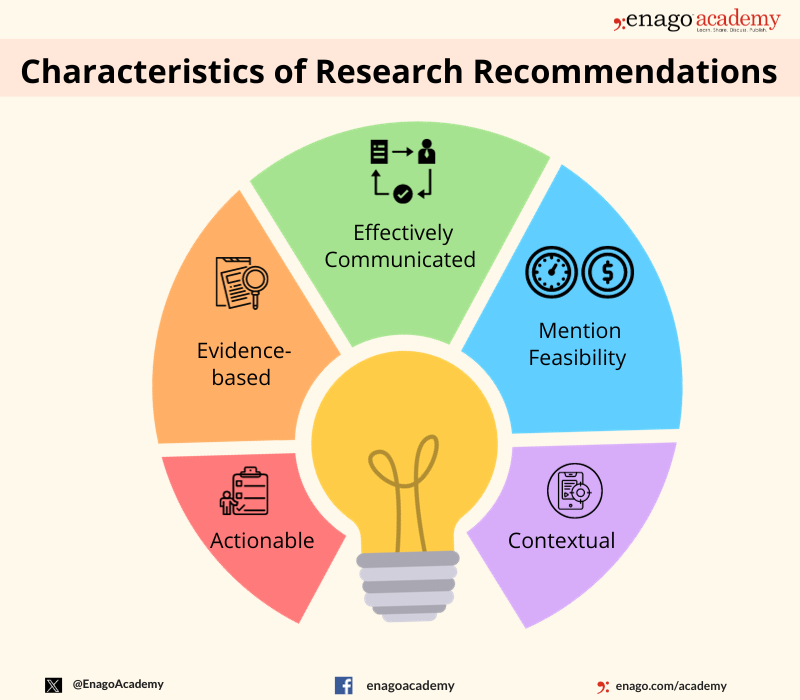

Characteristics of Research Recommendations

Research recommendations are a key component of research studies and are intended to provide practical guidance on how to apply research findings to real-world problems. The following are some of the key characteristics of research recommendations:

- Actionable : Research recommendations should be specific and actionable, providing clear guidance on what actions should be taken to address the problem identified in the research.

- Evidence-based: Research recommendations should be based on the findings of the research study, supported by the data collected and analyzed.

- Contextual: Research recommendations should be tailored to the specific context in which they will be implemented, taking into account the unique circumstances and constraints of the situation.

- Feasible : Research recommendations should be realistic and feasible, taking into account the available resources, time constraints, and other factors that may impact their implementation.

- Prioritized: Research recommendations should be prioritized based on their potential impact and feasibility, with the most important recommendations given the highest priority.

- Communicated effectively: Research recommendations should be communicated clearly and effectively, using language that is understandable to the target audience.

- Evaluated : Research recommendations should be evaluated to determine their effectiveness in addressing the problem identified in the research, and to identify opportunities for improvement.

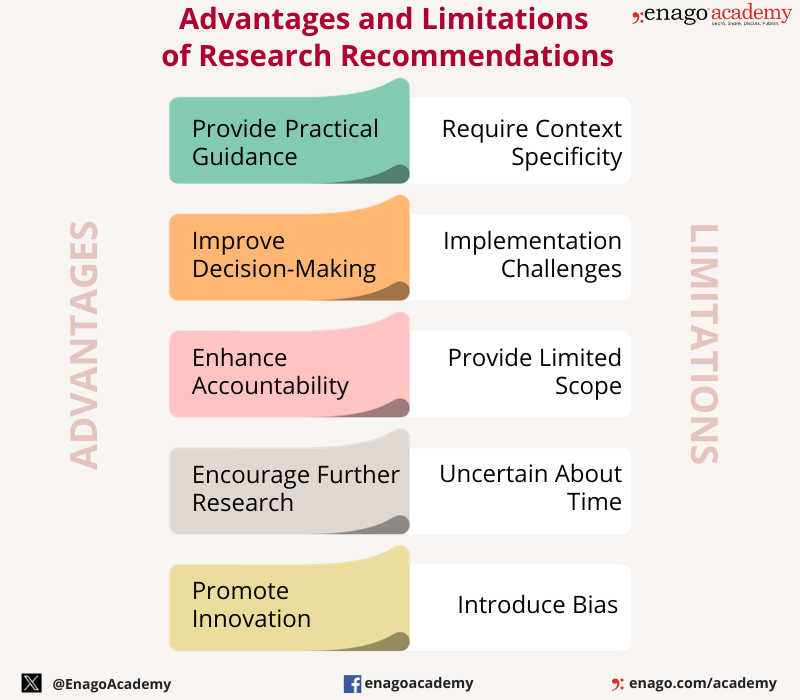

Advantages of Research Recommendations

Research recommendations have several advantages, including:

- Providing practical guidance: Research recommendations provide practical guidance on how to apply research findings to real-world problems, helping to bridge the gap between research and practice.

- Improving decision-making: Research recommendations help decision-makers make informed decisions based on the findings of research, leading to better outcomes and improved performance.

- Enhancing accountability : Research recommendations can help enhance accountability by providing clear guidance on what actions should be taken, and by providing a basis for evaluating progress and outcomes.

- Informing policy development : Research recommendations can inform the development of policies that are evidence-based and tailored to the specific needs of a given situation.

- Enhancing knowledge transfer: Research recommendations help facilitate the transfer of knowledge from researchers to practitioners, policymakers, or other stakeholders who can benefit from the research findings.

- Encouraging further research : Research recommendations can help identify gaps in knowledge and areas for further research, encouraging continued exploration and discovery.

- Promoting innovation: Research recommendations can help identify innovative solutions to complex problems, leading to new ideas and approaches.

Limitations of Research Recommendations

While research recommendations have several advantages, there are also some limitations to consider. These limitations include:

- Context-specific: Research recommendations may be context-specific and may not be applicable in all situations. Recommendations developed in one context may not be suitable for another context, requiring adaptation or modification.

- I mplementation challenges: Implementation of research recommendations may face challenges, such as lack of resources, resistance to change, or lack of buy-in from stakeholders.

- Limited scope: Research recommendations may be limited in scope, focusing only on a specific issue or aspect of a problem, while other important factors may be overlooked.

- Uncertainty : Research recommendations may be uncertain, particularly when the research findings are inconclusive or when the recommendations are based on limited data.

- Bias : Research recommendations may be influenced by researcher bias or conflicts of interest, leading to recommendations that are not in the best interests of stakeholders.

- Timing : Research recommendations may be time-sensitive, requiring timely action to be effective. Delayed action may result in missed opportunities or reduced effectiveness.

- Lack of evaluation: Research recommendations may not be evaluated to determine their effectiveness or impact, making it difficult to assess whether they are successful or not.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and...

Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

Appendix in Research Paper – Examples and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

The Ultimate Guide to Crafting Impactful Recommendations in Research

Are you ready to take your research to the next level? Crafting impactful recommendations is the key to unlocking the full potential of your study. By providing clear, actionable suggestions based on your findings, you can bridge the gap between research and real-world application.

In this ultimate guide, we'll show you how to write recommendations that make a difference in your research report or paper.

You'll learn how to craft specific, actionable recommendations that connect seamlessly with your research findings. Whether you're a student, writer, teacher, or journalist, this guide will help you master the art of writing recommendations in research. Let's get started and make your research count!

Understanding the Purpose of Recommendations

Recommendations in research serve as a vital bridge between your findings and their real-world applications. They provide specific, action-oriented suggestions to guide future studies and decision-making processes. Let's dive into the key purposes of crafting effective recommendations:

Guiding Future Research

Research recommendations play a crucial role in steering scholars and researchers towards promising avenues of exploration. By highlighting gaps in current knowledge and proposing new research questions, recommendations help advance the field and drive innovation.

Influencing Decision-Making

Well-crafted recommendations have the power to shape policies, programs, and strategies across various domains, such as:

- Policy-making

- Product development

- Marketing strategies

- Medical practice

By providing clear, evidence-based suggestions, recommendations facilitate informed decision-making and improve outcomes.

Connecting Research to Practice

Recommendations act as a conduit for transferring knowledge from researchers to practitioners, policymakers, and stakeholders. They bridge the gap between academic findings and their practical applications, ensuring that research insights are effectively translated into real-world solutions.

Enhancing Research Impact

Purpose | Description |

|---|---|

Relevance | Recommendations showcase the relevance and significance of your research findings. |

Visibility | Well-articulated recommendations increase the visibility and impact of your work. |

Collaboration | Recommendations foster collaboration and knowledge-sharing among researchers. |

By crafting impactful recommendations, you can amplify the reach and influence of your research, attracting attention from peers, funding agencies, and decision-makers.

Addressing Limitations

Recommendations provide an opportunity to acknowledge and address the limitations of your study. By suggesting concrete and actionable possibilities for future research, you demonstrate a thorough understanding of your work's scope and potential areas for improvement.

Identifying Areas for Future Research

Discovering research gaps is a crucial step in crafting impactful recommendations. It involves reviewing existing studies and identifying unanswered questions or problems that warrant further investigation. Here are some strategies to help you identify areas for future research:

Explore Research Limitations

Take a close look at the limitations section of relevant studies. These limitations often provide valuable insights into potential areas for future research. Consider how addressing these limitations could enhance our understanding of the topic at hand.

Critically Analyze Discussion and Future Research Sections

When reading articles, pay special attention to the discussion and future research sections. These sections often highlight gaps in the current knowledge base and propose avenues for further exploration. Take note of any recurring themes or unanswered questions that emerge across multiple studies.

Utilize Targeted Search Terms

To streamline your search for research gaps, use targeted search terms such as "literature gap" or "future research" in combination with your subject keywords. This approach can help you quickly identify articles that explicitly discuss areas for future investigation.

Seek Guidance from Experts

Don't hesitate to reach out to your research advisor or other experts in your field. Their wealth of knowledge and experience can provide valuable insights into potential research gaps and emerging trends.

Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

Broaden Your Horizons | Explore various topics and themes within your field to identify subjects that pique your interest and offer ample research opportunities. |

Leverage Digital Tools | Utilize digital tools to identify popular topics and highly cited research papers. These tools can help you gauge the current state of research and pinpoint areas that require further investigation. |

Collaborate with Peers | Engage in discussions with your peers and colleagues. Brainstorming sessions and collaborative exchanges can spark new ideas and reveal unexplored research avenues. |

By employing these strategies, you'll be well-equipped to identify research gaps and craft recommendations that push the boundaries of current knowledge. Remember, the goal is to refine your research questions and focus your efforts on areas where more understanding is needed.

Structuring Your Recommendations

When it comes to structuring your recommendations, it's essential to keep them concise, organized, and tailored to your audience. Here are some key tips to help you craft impactful recommendations:

Prioritize and Organize

- Limit your recommendations to the most relevant and targeted suggestions for your peers or colleagues in the field.

- Place your recommendations at the end of the report, as they are often top of mind for readers.

- Write your recommendations in order of priority, with the most important ones for decision-makers coming first.

Use a Clear and Actionable Format

- Write recommendations in a clear, concise manner using actionable words derived from the data analyzed in your research.

- Use bullet points instead of long paragraphs for clarity and readability.

- Ensure that your recommendations are specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timely (SMART).

Connect Recommendations to Research

Element | Description |

|---|---|

Research Question | Clearly state the research question or problem addressed in your study. |

Conclusion | Summarize the key findings and conclusions drawn from your research. |

Recommendation | Provide specific, actionable suggestions based on your research findings. |

By following this simple formula, you can ensure that your recommendations are directly connected to your research and supported by a clear rationale.

Tailor to Your Audience

- Consider the needs and interests of your target audience when crafting your recommendations.

- Explain how your recommendations can solve the issues explored in your research.

- Acknowledge any limitations or constraints of your study that may impact the implementation of your recommendations.

Avoid Common Pitfalls

- Don't undermine your own work by suggesting incomplete or unnecessary recommendations.

- Avoid using recommendations as a place for self-criticism or introducing new information not covered in your research.

- Ensure that your recommendations are achievable and comprehensive, offering practical solutions for the issues considered in your paper.

By structuring your recommendations effectively, you can enhance the reliability and validity of your research findings, provide valuable strategies and suggestions for future research, and deliver impactful solutions to real-world problems.

Crafting Actionable and Specific Recommendations

Crafting actionable and specific recommendations is the key to ensuring your research findings have a real-world impact. Here are some essential tips to keep in mind:

Embrace Flexibility and Feasibility

Your recommendations should be open to discussion and new information, rather than being set in stone. Consider the following:

- Be realistic and considerate of your team's capabilities when making recommendations.

- Prioritize recommendations based on impact and reach, but be prepared to adjust based on team effort levels.

- Focus on solutions that require the fewest changes first, adopting an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) approach.

Provide Detailed and Justified Recommendations

To avoid vagueness and misinterpretation, ensure your recommendations are:

- Detailed, including photos, videos, or screenshots whenever possible.

- Justified based on research findings, providing alternatives when findings don't align with expectations or business goals.

Use this formula when writing recommendations:

Observed problem/pain point/unmet need + consequence + potential solution

Adopt a Solution-Oriented Approach

Element | Description |

|---|---|

Tone | Write recommendations in a clear, confident, and positive tone. |

Action Plan | Include an action plan along with the recommendation to add more weightage. |

Approach | Display a solution-oriented approach throughout your recommendations. |

Foster Collaboration and Participation

- Promote staff education on current research and create strategies to encourage adoption of promising clinical protocols.

- Include representatives from the treatment community in the development of the research initiative and the review of proposals.

- Require active, early, and permanent participation of treatment staff in the development, implementation, and interpretation of the study.

Tailor Recommendations to the Opportunity

When writing recommendations for a specific opportunity or program:

- Highlight the strengths and qualifications of the researcher.

- Provide specific examples of their work and accomplishments.

- Explain how their research has contributed to the field.

- Emphasize the researcher's potential for future success and their unique contributions.

By following these guidelines, you'll craft actionable and specific recommendations that drive meaningful change and showcase the value of your research.

Connecting Recommendations with Research Findings

Connecting your recommendations with research findings is crucial for ensuring the credibility and impact of your suggestions. Here's how you can seamlessly link your recommendations to the evidence uncovered in your study:

Grounding Recommendations in Research

Your recommendations should be firmly rooted in the data and insights gathered during your research process. Avoid including measures or suggestions that were not discussed or supported by your study findings. This approach ensures that your recommendations are evidence-based and directly relevant to the research at hand.

Highlighting the Significance of Collaboration

Research collaborations offer a wealth of benefits that can enhance an agency's competitive position. Consider the following factors when discussing the importance of collaboration in your recommendations:

- Organizational Development: Participation in research collaborations depends on an agency's stage of development, compatibility with its mission and culture, and financial stability.

- Trust-Building: Long-term collaboration success often hinges on a history of increasing involvement and trust between partners.

- Infrastructure: A permanent infrastructure that facilitates long-term development is key to successful collaborative programs.

Emphasizing Commitment and Participation

Element | Description |

|---|---|

Treatment Programs | Commitment from community-based treatment programs is crucial for successful implementation. |

Researchers | Encouragement of community-based programs to participate in various types of research is essential. |

Collaboration | Seeking collaboration with researchers to build information systems that enhance service delivery, improve management, and contribute to research databases is vital. |

Fostering Quality Improvement and Organizational Learning

In your recommendations, highlight the importance of enhancing quality improvement strategies and fostering organizational learning. Show sensitivity to the needs and constraints of community-based programs, as this understanding is crucial for effective collaboration and implementation.

Addressing Limitations and Implications

If not already addressed in the discussion section, your recommendations should mention the limitations of the study and their implications. Examples of limitations include:

- Sample size or composition

- Participant attrition

- Study duration

By acknowledging these limitations, you demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of your research and its potential impact.

By connecting your recommendations with research findings, you provide a solid foundation for your suggestions, emphasize the significance of collaboration, and showcase the potential for future research and practical applications.

Crafting impactful recommendations is a vital skill for any researcher looking to bridge the gap between their findings and real-world applications. By understanding the purpose of recommendations, identifying areas for future research, structuring your suggestions effectively, and connecting them to your research findings, you can unlock the full potential of your study. Remember to prioritize actionable, specific, and evidence-based recommendations that foster collaboration and drive meaningful change.

As you embark on your research journey, embrace the power of well-crafted recommendations to amplify the impact of your work. By following the guidelines outlined in this ultimate guide, you'll be well-equipped to write recommendations that resonate with your audience, inspire further investigation, and contribute to the advancement of your field. So go forth, make your research count, and let your recommendations be the catalyst for positive change.

Q: What are the steps to formulating recommendations in research? A: To formulate recommendations in research, you should first gain a thorough understanding of the research question. Review the existing literature to inform your recommendations and consider the research methods that were used. Identify which data collection techniques were employed and propose suitable data analysis methods. It's also essential to consider any limitations and ethical considerations of your research. Justify your recommendations clearly and finally, provide a summary of your recommendations.

Q: Why are recommendations significant in research studies? A: Recommendations play a crucial role in research as they form a key part of the analysis phase. They provide specific suggestions for interventions or strategies that address the problems and limitations discovered during the study. Recommendations are a direct response to the main findings derived from data collection and analysis, and they can guide future actions or research.

Q: Can you outline the seven steps involved in writing a research paper? A: Certainly. The seven steps to writing an excellent research paper include:

- Allowing yourself sufficient time to complete the paper.

- Defining the scope of your essay and crafting a clear thesis statement.

- Conducting a thorough yet focused search for relevant research materials.

- Reading the research materials carefully and taking detailed notes.

- Writing your paper based on the information you've gathered and analyzed.

- Editing your paper to ensure clarity, coherence, and correctness.

- Submitting your paper following the guidelines provided.

Q: What tips can help make a research paper more effective? A: To enhance the effectiveness of a research paper, plan for the extensive process ahead and understand your audience. Decide on the structure your research writing will take and describe your methodology clearly. Write in a straightforward and clear manner, avoiding the use of clichés or overly complex language.

Sign up for more like this.

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of exploration. In an era marked by rapid technological advancements and an ever-expanding knowledge base, refining the process of generating research recommendations becomes imperative.

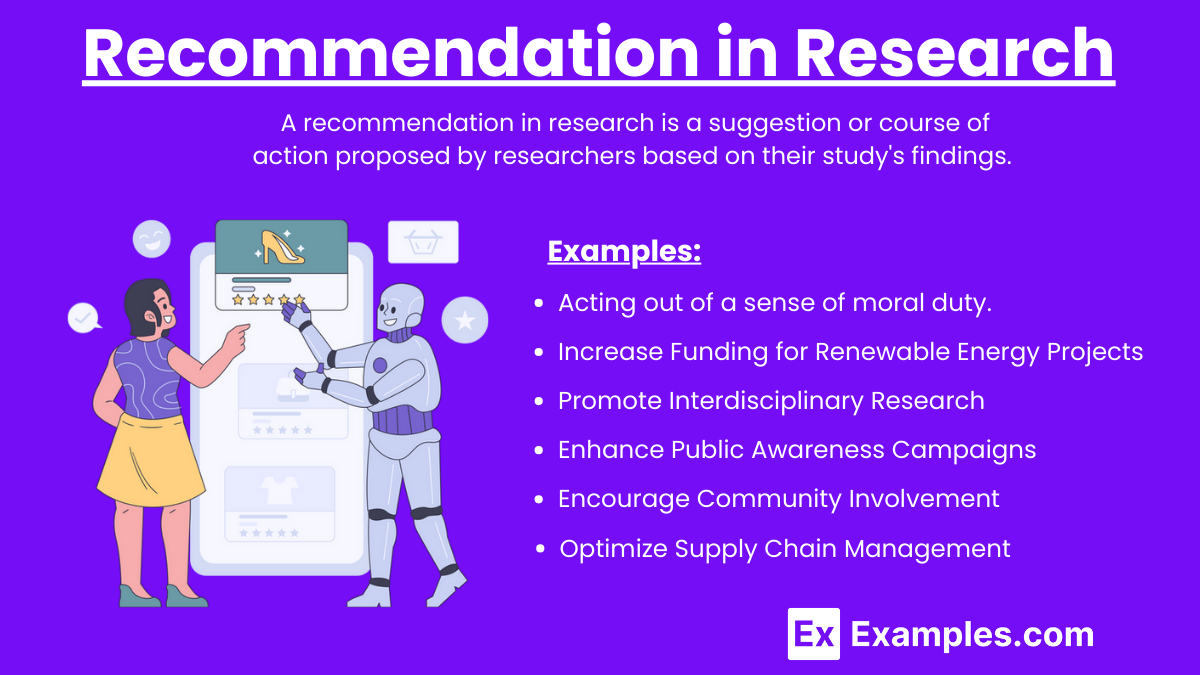

But, what is a research recommendation?

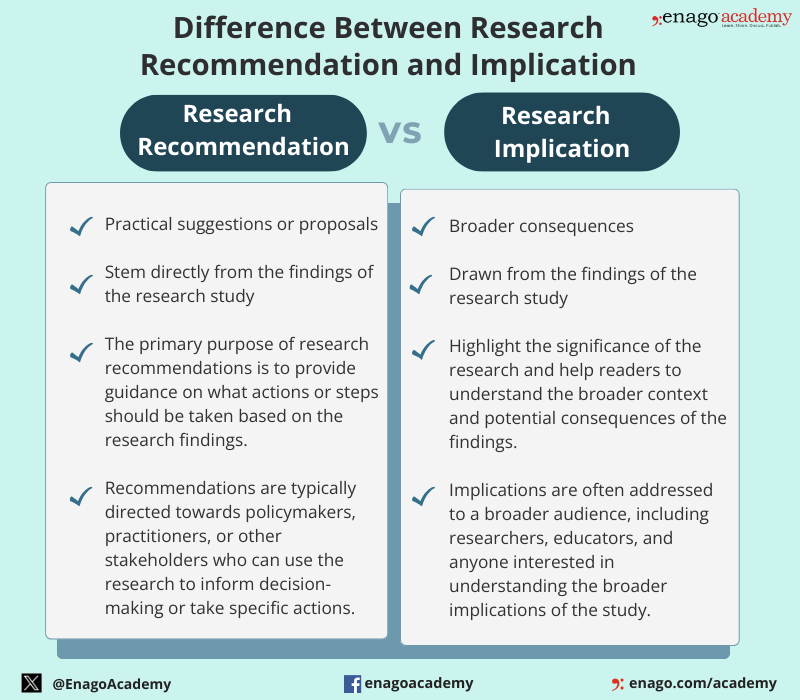

Research recommendations are suggestions or advice provided to researchers to guide their study on a specific topic . They are typically given by experts in the field. Research recommendations are more action-oriented and provide specific guidance for decision-makers, unlike implications that are broader and focus on the broader significance and consequences of the research findings. However, both are crucial components of a research study.

Difference Between Research Recommendations and Implication

Although research recommendations and implications are distinct components of a research study, they are closely related. The differences between them are as follows:

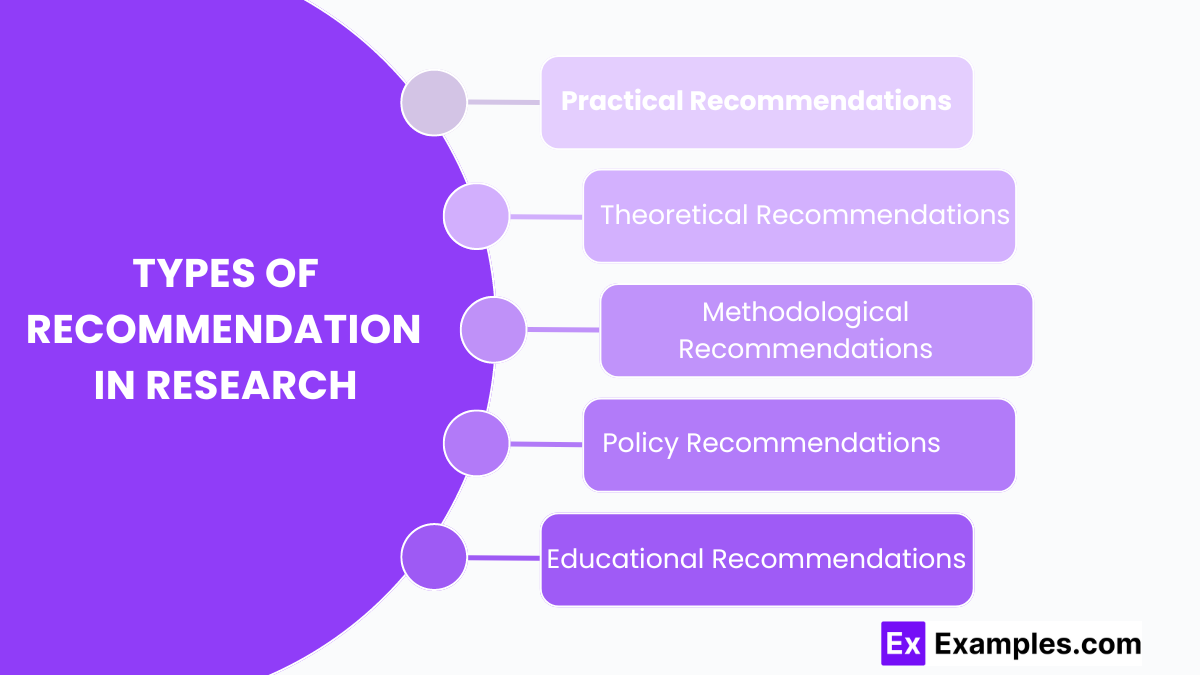

Types of Research Recommendations

Recommendations in research can take various forms, which are as follows:

| Article Recommendations | Suggests specific research articles, papers, or publications |

| Topic Recommendations | Guides researchers toward specific research topics or areas |

| Methodology Recommendations | Offers advice on research methodologies, statistical techniques, or experimental designs |

| Collaboration Recommendations | Connects researchers with others who share similar interests or expertise |

These recommendations aim to assist researchers in navigating the vast landscape of academic knowledge.

Let us dive deeper to know about its key components and the steps to write an impactful research recommendation.

Key Components of Research Recommendations

The key components of research recommendations include defining the research question or objective, specifying research methods, outlining data collection and analysis processes, presenting results and conclusions, addressing limitations, and suggesting areas for future research. Here are some characteristics of research recommendations:

Research recommendations offer various advantages and play a crucial role in ensuring that research findings contribute to positive outcomes in various fields. However, they also have few limitations which highlights the significance of a well-crafted research recommendation in offering the promised advantages.

The importance of research recommendations ranges in various fields, influencing policy-making, program development, product development, marketing strategies, medical practice, and scientific research. Their purpose is to transfer knowledge from researchers to practitioners, policymakers, or stakeholders, facilitating informed decision-making and improving outcomes in different domains.

How to Write Research Recommendations?

Research recommendations can be generated through various means, including algorithmic approaches, expert opinions, or collaborative filtering techniques. Here is a step-wise guide to build your understanding on the development of research recommendations.

1. Understand the Research Question:

Understand the research question and objectives before writing recommendations. Also, ensure that your recommendations are relevant and directly address the goals of the study.

2. Review Existing Literature:

Familiarize yourself with relevant existing literature to help you identify gaps , and offer informed recommendations that contribute to the existing body of research.

3. Consider Research Methods:

Evaluate the appropriateness of different research methods in addressing the research question. Also, consider the nature of the data, the study design, and the specific objectives.

4. Identify Data Collection Techniques:

Gather dataset from diverse authentic sources. Include information such as keywords, abstracts, authors, publication dates, and citation metrics to provide a rich foundation for analysis.

5. Propose Data Analysis Methods:

Suggest appropriate data analysis methods based on the type of data collected. Consider whether statistical analysis, qualitative analysis, or a mixed-methods approach is most suitable.

6. Consider Limitations and Ethical Considerations:

Acknowledge any limitations and potential ethical considerations of the study. Furthermore, address these limitations or mitigate ethical concerns to ensure responsible research.

7. Justify Recommendations:

Explain how your recommendation contributes to addressing the research question or objective. Provide a strong rationale to help researchers understand the importance of following your suggestions.

8. Summarize Recommendations:

Provide a concise summary at the end of the report to emphasize how following these recommendations will contribute to the overall success of the research project.

By following these steps, you can create research recommendations that are actionable and contribute meaningfully to the success of the research project.

Download now to unlock some tips to improve your journey of writing research recommendations.

Example of a Research Recommendation

Here is an example of a research recommendation based on a hypothetical research to improve your understanding.

Research Recommendation: Enhancing Student Learning through Integrated Learning Platforms

Background:

The research study investigated the impact of an integrated learning platform on student learning outcomes in high school mathematics classes. The findings revealed a statistically significant improvement in student performance and engagement when compared to traditional teaching methods.

Recommendation:

In light of the research findings, it is recommended that educational institutions consider adopting and integrating the identified learning platform into their mathematics curriculum. The following specific recommendations are provided:

- Implementation of the Integrated Learning Platform:

Schools are encouraged to adopt the integrated learning platform in mathematics classrooms, ensuring proper training for teachers on its effective utilization.

- Professional Development for Educators:

Develop and implement professional programs to train educators in the effective use of the integrated learning platform to address any challenges teachers may face during the transition.

- Monitoring and Evaluation:

Establish a monitoring and evaluation system to track the impact of the integrated learning platform on student performance over time.

- Resource Allocation:

Allocate sufficient resources, both financial and technical, to support the widespread implementation of the integrated learning platform.

By implementing these recommendations, educational institutions can harness the potential of the integrated learning platform and enhance student learning experiences and academic achievements in mathematics.

This example covers the components of a research recommendation, providing specific actions based on the research findings, identifying the target audience, and outlining practical steps for implementation.

Using AI in Research Recommendation Writing

Enhancing research recommendations is an ongoing endeavor that requires the integration of cutting-edge technologies, collaborative efforts, and ethical considerations. By embracing data-driven approaches and leveraging advanced technologies, the research community can create more effective and personalized recommendation systems. However, it is accompanied by several limitations. Therefore, it is essential to approach the use of AI in research with a critical mindset, and complement its capabilities with human expertise and judgment.

Here are some limitations of integrating AI in writing research recommendation and some ways on how to counter them.

1. Data Bias

AI systems rely heavily on data for training. If the training data is biased or incomplete, the AI model may produce biased results or recommendations.

How to tackle: Audit regularly the model’s performance to identify any discrepancies and adjust the training data and algorithms accordingly.

2. Lack of Understanding of Context:

AI models may struggle to understand the nuanced context of a particular research problem. They may misinterpret information, leading to inaccurate recommendations.

How to tackle: Use AI to characterize research articles and topics. Employ them to extract features like keywords, authorship patterns and content-based details.

3. Ethical Considerations:

AI models might stereotype certain concepts or generate recommendations that could have negative consequences for certain individuals or groups.

How to tackle: Incorporate user feedback mechanisms to reduce redundancies. Establish an ethics review process for AI models in research recommendation writing.

4. Lack of Creativity and Intuition:

AI may struggle with tasks that require a deep understanding of the underlying principles or the ability to think outside the box.

How to tackle: Hybrid approaches can be employed by integrating AI in data analysis and identifying patterns for accelerating the data interpretation process.

5. Interpretability:

Many AI models, especially complex deep learning models, lack transparency on how the model arrived at a particular recommendation.

How to tackle: Implement models like decision trees or linear models. Provide clear explanation of the model architecture, training process, and decision-making criteria.

6. Dynamic Nature of Research:

Research fields are dynamic, and new information is constantly emerging. AI models may struggle to keep up with the rapidly changing landscape and may not be able to adapt to new developments.

How to tackle: Establish a feedback loop for continuous improvement. Regularly update the recommendation system based on user feedback and emerging research trends.

The integration of AI in research recommendation writing holds great promise for advancing knowledge and streamlining the research process. However, navigating these concerns is pivotal in ensuring the responsible deployment of these technologies. Researchers need to understand the use of responsible use of AI in research and must be aware of the ethical considerations.

Exploring research recommendations plays a critical role in shaping the trajectory of scientific inquiry. It serves as a compass, guiding researchers toward more robust methodologies, collaborative endeavors, and innovative approaches. Embracing these suggestions not only enhances the quality of individual studies but also contributes to the collective advancement of human understanding.

Frequently Asked Questions

The purpose of recommendations in research is to provide practical and actionable suggestions based on the study's findings, guiding future actions, policies, or interventions in a specific field or context. Recommendations bridges the gap between research outcomes and their real-world application.

To make a research recommendation, analyze your findings, identify key insights, and propose specific, evidence-based actions. Include the relevance of the recommendations to the study's objectives and provide practical steps for implementation.

Begin a recommendation by succinctly summarizing the key findings of the research. Clearly state the purpose of the recommendation and its intended impact. Use a direct and actionable language to convey the suggested course of action.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Promoting Research

Graphical Abstracts Vs. Infographics: Best practices for using visual illustrations for increased research impact

Dr. Sarah Chen stared at her computer screen, her eyes staring at her recently published…

- Publishing Research

10 Tips to Prevent Research Papers From Being Retracted

Research paper retractions represent a critical event in the scientific community. When a published article…

- Industry News

Google Releases 2024 Scholar Metrics, Evaluates Impact of Scholarly Articles

Google has released its 2024 Scholar Metrics, assessing scholarly articles from 2019 to 2023. This…

- Career Corner

- Reporting Research

How to Create a Poster That Stands Out: Tips for a smooth poster presentation

It was the conference season. Judy was excited to present her first poster! She had…

- Diversity and Inclusion

6 Reasons Why There is a Decline in Higher Education Enrollment: Action plan to overcome this crisis

Over the past decade, colleges and universities across the globe have witnessed a concerning trend…

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

How to Effectively Cite a PDF (APA, MLA, AMA, and Chicago Style)

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- AI in Academia

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer Review Week 2024

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

Which among these features would you prefer the most in a peer review assistant?

- How it works

How To Write Recommendations In A Research Study

Published by Alvin Nicolas at July 12th, 2024 , Revised On July 12, 2024

The ultimate goal of any research process is not just to gather knowledge, but to use that knowledge to make a positive impact. This is where recommendations come in. A well-written recommendations section in your research study translates your findings into actionable steps and guides future research on the topic.

This blog is your ultimate guide to understanding how to write recommendations in a research study. But before that, let’s see what is recommendation in research.

What Is Recommendation In Research

In a research study, the recommendation section refers to a suggested course of action based on the findings of your research . It acts as a bridge between the knowledge you gained and its practical implications.

Recommendations take your research results and propose concrete steps on how to use them to address a problem or improve a situation. Moreover, you can suggest new avenues and guide future research in building upon your work. This will improve the credibility of your research. For studies that include real-world implications, recommendations are a great way to provide evidence-based suggestions for policymakers or practitioners to consider.

Difference Between Research Recommendations and Implication

Research recommendations and implications often confuse researchers. They cannot easily differentiate between the two. Here is how they are different.

| Research Recommendation | Research Implication |

|---|---|

| Focuses on actionable steps | Focuses on actionable steps |

| Translate findings into practical applications | Highlights the significance of the research |

| Specific actions | Broad predictions |

| Based on the research findings and existing literature | Based on the research findings and connections to other research areas |

Where To Add Recommendations

Recommendations are mostly part of your conclusion and discussion sections. If you are writing a practical dissertation , you can include a separate section for your recommendations.

Types of Research Recommendations

There are different forms of recommendations in research. Some of them include the following.

| Suggests improvements to the used in your field. | |

| Highlights new areas of research within your broader topic. | |

| Offers information on key articles or publications that provide insights on your . | |

| Suggest ways for researchers with different expertise to collaborate on future projects. |

How To Construct The Recommendations Section

There are different ways in which different scholars write the recommendations section. A general observation is a research question → conclusion → recommendation.

The following example will help you understand this better.

Research Question

How can the education of mothers impact the social skills of kindergarten children?

The role of mothers is a significant contributor towards the social skills of children. From an early age, kids tend to observe how their mother interacts with others and follow in her footsteps initially. Therefore, mothers should be educated and interact with good demeanour if they want their children to have excellent social skills.

Recommendation

The study revealed that a mother’s education plays an important role in building the social skills of children on kindergarten level. Future research could explore how the same continues in junior school level children.

How To Write Recommendations In Research

Now that you are familiar with the definition and types, here is a step-by-step guide on how to write a recommendation in research.

Step 1: Revisit Your Research Goals

Before doing anything else, you have to remind yourself of the objectives that you set out to achieve in your research. It allows you to match your recommendations directly to your research questions and see if you made any contribution to your goals.

Step 2: Analyse Your Findings

You have to examine your data and identify your key results. This analysis forms the foundation for your recommendations. Look for patterns and unexpected findings that might suggest new areas for other researchers to explore.

Step 3: Consider The Research Methods

Ask these questions from yourself: were the research methods effective? Is there any other way that would have been better to perform this research, or were there any limitations associated with the research methods?

Step 4: Prioritise Recommendations

You might have a lot of recommendations in mind, but all are not equal. You have to consider the impact and feasibility of each suggestion. Prioritise these recommendations, while remaining realistic about implementation.

Step 5: Write Actionable Statements

Do not be vague when crafting statements. Instead, you have to use clear and concise language that outlines specific actions. For example, if you want to say “improve education practices,” you could write “implement a teacher training program” for better clarity.

Step 6: Provide Evidence

You cannot just make suggestions out of thin air, and have to ground them in the evidence you have gathered through your research. Moreover, cite relevant data or findings from your study or previous literature to support your recommendations.

Step 7: Address Challenges

There are always some limitations related to the research at hand. As a researcher, it is your duty to highlight and address any challenges faced or what might occur in the future.

Tips For Writing The Perfect Recommendation In Research

Use these tips to write the perfect recommendation in your research.

- Be Concise – Write recommendations in a clear and concise language. Use one sentence statements to look more professional.

- Be Logical & Coherent – You can use lists and headings according to the requirements of your university.

- Tailor According To Your Readers – You have to aim your recommendations to a specific audience and colleagues in the field of study.

- Provide Specific Suggestions – Offer specific measures and solutions to the issues, and focus on actionable suggestions.

- Match Recommendations To Your Conclusion – You have to align your recommendations with your conclusion.

- Consider Limitations – Use critical thinking to see how limitations may impact the feasibility of your solutions.

- End With A Summary – You have to add a small conclusion to highlight suggestions and their impact.

Example Of Recommendation In Research

Context of the study:

This research studies how effective e-learning platforms are for adult language learners compared to traditional classroom instruction. The findings suggest that e-learning platforms can be just as effective as traditional classrooms in improving language proficiency.

Research Recommendation Sample

Language educators can incorporate e-learning tools into existing curriculums to provide learners with more flexibility. Additionally, they can develop training programs for educators on how to integrate e-learning platforms into their teaching practices.

E-learning platform developers should focus on e-learning platforms that are interactive and cater to different learning styles. They can also invest in features that promote learner autonomy and self-directed learning.

Future researchers can further explore the long-term effects of e-learning on language acquisition to provide insights into whether e-learning can support sustained language development.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to write recommendations in a research paper.

- Revisit your research goals

- Analyse your findings

- Consider the research methods

- Prioritise recommendations

- Write actionable statements

- Provide evidence

- Address challenges

How to present recommendations in research?

- Be concise

- Write logical and coherent

- Match recommendations to conclusion

- Ensure your recommendations are achievable

What to write in recommendation in research?

Your recommendation has to be concrete and specific and support the research with a clear rationale. Moreover, it should be connected directly to your research. Your recommendations, however, should not undermine your own work or use self-criticism.

You May Also Like

How to Structure a Dissertation or Thesis Need interesting and manageable Finance and Accounting dissertation topics? Here are the trending Media dissertation titles so you can choose one most suitable to your needs.

Not sure how to start your dissertation and get it right the first time? Here are some tips and guidelines for you to kick start your dissertation project.

Finding it difficult to maintain a good relationship with your supervisor? Here are some tips on ‘How to Deal with an Unhelpful Dissertation Supervisor’.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

Published on 15 September 2022 by Tegan George .

Recommendations in research are a crucial component of your discussion section and the conclusion of your thesis , dissertation , or research paper .

As you conduct your research and analyse the data you collected , perhaps there are ideas or results that don’t quite fit the scope of your research topic . Or, maybe your results suggest that there are further implications of your results or the causal relationships between previously-studied variables than covered in extant research.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

What should recommendations look like, building your research recommendation, how should your recommendations be written, recommendation in research example, frequently asked questions about recommendations.

Recommendations for future research should be:

- Concrete and specific

- Supported with a clear rationale

- Directly connected to your research

Overall, strive to highlight ways other researchers can reproduce or replicate your results to draw further conclusions, and suggest different directions that future research can take, if applicable.

Relatedly, when making these recommendations, avoid:

- Undermining your own work, but rather offer suggestions on how future studies can build upon it

- Suggesting recommendations actually needed to complete your argument, but rather ensure that your research stands alone on its own merits

- Using recommendations as a place for self-criticism, but rather as a natural extension point for your work

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

There are many different ways to frame recommendations, but the easiest is perhaps to follow the formula of research question conclusion recommendation. Here’s an example.

Conclusion An important condition for controlling many social skills is mastering language. If children have a better command of language, they can express themselves better and are better able to understand their peers. Opportunities to practice social skills are thus dependent on the development of language skills.

As a rule of thumb, try to limit yourself to only the most relevant future recommendations: ones that stem directly from your work. While you can have multiple recommendations for each research conclusion, it is also acceptable to have one recommendation that is connected to more than one conclusion.

These recommendations should be targeted at your audience, specifically toward peers or colleagues in your field that work on similar topics to yours. They can flow directly from any limitations you found while conducting your work, offering concrete and actionable possibilities for how future research can build on anything that your own work was unable to address at the time of your writing.

See below for a full research recommendation example that you can use as a template to write your own.

The current study can be interpreted as a first step in the research on COPD speech characteristics. However, the results of this study should be treated with caution due to the small sample size and the lack of details regarding the participants’ characteristics.

Future research could further examine the differences in speech characteristics between exacerbated COPD patients, stable COPD patients, and healthy controls. It could also contribute to a deeper understanding of the acoustic measurements suitable for e-health measurements.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

While it may be tempting to present new arguments or evidence in your thesis or disseration conclusion , especially if you have a particularly striking argument you’d like to finish your analysis with, you shouldn’t. Theses and dissertations follow a more formal structure than this.

All your findings and arguments should be presented in the body of the text (more specifically in the discussion section and results section .) The conclusion is meant to summarize and reflect on the evidence and arguments you have already presented, not introduce new ones.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation should include the following:

- A restatement of your research question

- A summary of your key arguments and/or results

- A short discussion of the implications of your research

For a stronger dissertation conclusion , avoid including:

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion…”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g. “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, September 15). How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/research-recommendations/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, how to write a results section | tips & examples.

Research Implications & Recommendations

A Plain-Language Explainer With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | May 2024

The research implications and recommendations are closely related but distinctly different concepts that often trip students up. Here, we’ll unpack them using plain language and loads of examples , so that you can approach your project with confidence.

Overview: Implications & Recommendations

- What are research implications ?

- What are research recommendations ?

- Examples of implications and recommendations

- The “ Big 3 ” categories

- How to write the implications and recommendations

- Template sentences for both sections

- Key takeaways

Implications & Recommendations 101

Let’s start with the basics and define our terms.

At the simplest level, research implications refer to the possible effects or outcomes of a study’s findings. More specifically, they answer the question, “ What do these findings mean?” . In other words, the implications section is where you discuss the broader impact of your study’s findings on theory, practice and future research.

This discussion leads us to the recommendations section , which is where you’ll propose specific actions based on your study’s findings and answer the question, “ What should be done next?” . In other words, the recommendations are practical steps that stakeholders can take to address the key issues identified by your study.

In a nutshell, then, the research implications discuss the broader impact and significance of a study’s findings, while recommendations provide specific actions to take, based on those findings. So, while both of these components are deeply rooted in the findings of the study, they serve different functions within the write up.

Need a helping hand?

Examples: Implications & Recommendations

The distinction between research implications and research recommendations might still feel a bit conceptual, so let’s look at one or two practical examples:

Let’s assume that your study finds that interactive learning methods significantly improve student engagement compared to traditional lectures. In this case, one of your recommendations could be that schools incorporate more interactive learning techniques into their curriculums to enhance student engagement.

Let’s imagine that your study finds that patients who receive personalised care plans have better health outcomes than those with standard care plans. One of your recommendations might be that healthcare providers develop and implement personalised care plans for their patients.

Now, these are admittedly quite simplistic examples, but they demonstrate the difference (and connection ) between the research implications and the recommendations. Simply put, the implications are about the impact of the findings, while the recommendations are about proposed actions, based on the findings.

The “Big 3” Categories

Now that we’ve defined our terms, let’s dig a little deeper into the implications – specifically, the different types or categories of research implications that exist.

Broadly speaking, implications can be divided into three categories – theoretical implications, practical implications and implications for future research .

Theoretical implications relate to how your study’s findings contribute to or challenge existing theories. For example, if a study on social behaviour uncovers new patterns, it might suggest that modifications to current psychological theories are necessary.

Practical implications , on the other hand, focus on how your study’s findings can be applied in real-world settings. For example, if your study demonstrated the effectiveness of a new teaching method, this would imply that educators should consider adopting this method to improve learning outcomes.

Practical implications can also involve policy reconsiderations . For example, if a study reveals significant health benefits from a particular diet, an implication might be that public health guidelines be re-evaluated.

Last but not least, there are the implications for future research . As the name suggests, this category of implications highlights the research gaps or new questions raised by your study. For example, if your study finds mixed results regarding a relationship between two variables, it might imply the need for further investigation to clarify these findings.

To recap then, the three types of implications are the theoretical, the practical and the implications on future research. Regardless of the category, these implications feed into and shape the recommendations , laying the foundation for the actions you’ll propose.

How To Write The Sections

Now that we’ve laid the foundations, it’s time to explore how to write up the implications and recommendations sections respectively.

Let’s start with the “ where ” before digging into the “ how ”. Typically, the implications will feature in the discussion section of your document, while the recommendations will be located in the conclusion . That said, layouts can vary between disciplines and institutions, so be sure to check with your university what their preferences are.

For the implications section, a common approach is to structure the write-up based on the three categories we looked at earlier – theoretical, practical and future research implications. In practical terms, this discussion will usually follow a fairly formulaic sentence structure – for example:

This research provides new insights into [theoretical aspect], indicating that…

The study’s outcomes highlight the potential benefits of adopting [specific practice] in..

This study raises several questions that warrant further investigation, such as…

Moving onto the recommendations section, you could again structure your recommendations using the three categories. Alternatively, you could structure the discussion per stakeholder group – for example, policymakers, organisations, researchers, etc.

Again, you’ll likely use a fairly formulaic sentence structure for this section. Here are some examples for your inspiration:

Based on the findings, [specific group] should consider adopting [new method] to improve…

To address the issues identified, it is recommended that legislation should be introduced to…

Researchers should consider examining [specific variable] to build on the current study’s findings.

Remember, you can grab a copy of our tried and tested templates for both the discussion and conclusion sections over on the Grad Coach blog. You can find the links to those, as well as loads of other free resources, in the description 🙂

FAQs: Implications & Recommendations

How do i determine the implications of my study.

To do this, you’ll need to consider how your findings address gaps in the existing literature, how they could influence theory, practice, or policy, and the potential societal or economic impacts.

When thinking about your findings, it’s also a good idea to revisit your introduction chapter, where you would have discussed the potential significance of your study more broadly. This section can help spark some additional ideas about what your findings mean in relation to your original research aims.

Should I discuss both positive and negative implications?

Absolutely. You’ll need to discuss both the positive and negative implications to provide a balanced view of how your findings affect the field and any limitations or potential downsides.

Can my research implications be speculative?

Yes and no. While implications are somewhat more speculative than recommendations and can suggest potential future outcomes, they should be grounded in your data and analysis. So, be careful to avoid overly speculative claims.

How do I formulate recommendations?

Ideally, you should base your recommendations on the limitations and implications of your study’s findings. So, consider what further research is needed, how policies could be adapted, or how practices could be improved – and make proposals in this respect.

How specific should my recommendations be?

Your recommendations should be as specific as possible, providing clear guidance on what actions or research should be taken next. As mentioned earlier, the implications can be relatively broad, but the recommendations should be very specific and actionable. Ideally, you should apply the SMART framework to your recommendations.

Can I recommend future research in my recommendations?

Absolutely. Highlighting areas where further research is needed is a key aspect of the recommendations section. Naturally, these recommendations should link to the respective section of your implications (i.e., implications for future research).

Wrapping Up: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered quite a bit of ground here, so let’s quickly recap.

- Research implications refer to the possible effects or outcomes of a study’s findings.

- The recommendations section, on the other hand, is where you’ll propose specific actions based on those findings.

- You can structure your implications section based on the three overarching categories – theoretical, practical and future research implications.

- You can carry this structure through to the recommendations as well, or you can group your recommendations by stakeholder.

Remember to grab a copy of our tried and tested free dissertation template, which covers both the implications and recommendations sections. If you’d like 1:1 help with your research project, be sure to check out our private coaching service, where we hold your hand throughout the research journey, step by step.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

I am taking a Research Design and Statistical Methods class. I am wondering if I can get tutors to help me with my homework to understand more about research and statistics. I want to pass this class. I searched on YouTube and watched some videos but I still need more clarification.

Great examples. Thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to formulate...

How to formulate research recommendations

- Related content

- Peer review

- Polly Brown ([email protected]) , publishing manager 1 ,

- Klara Brunnhuber , clinical editor 1 ,

- Kalipso Chalkidou , associate director, research and development 2 ,

- Iain Chalmers , director 3 ,

- Mike Clarke , director 4 ,

- Mark Fenton , editor 3 ,

- Carol Forbes , reviews manager 5 ,

- Julie Glanville , associate director/information service manager 5 ,

- Nicholas J Hicks , consultant in public health medicine 6 ,

- Janet Moody , identification and prioritisation manager 6 ,

- Sara Twaddle , director 7 ,

- Hazim Timimi , systems developer 8 ,

- Pamela Young , senior programme manager 6

- 1 BMJ Publishing Group, London WC1H 9JR,

- 2 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London WC1V 6NA,

- 3 Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments, James Lind Alliance Secretariat, James Lind Initiative, Oxford OX2 7LG,

- 4 UK Cochrane Centre, Oxford OX2 7LG,

- 5 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York YO10 5DD,

- 6 National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment, University of Southampton, Southampton SO16 7PX,

- 7 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Edinburgh EH2 1EN,

- 8 Update Software, Oxford OX2 7LG

- Correspondence to: PBrown

- Accepted 22 September 2006