- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Results/Findings Section in Research

What is the research paper Results section and what does it do?

The Results section of a scientific research paper represents the core findings of a study derived from the methods applied to gather and analyze information. It presents these findings in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation from the author, setting up the reader for later interpretation and evaluation in the Discussion section. A major purpose of the Results section is to break down the data into sentences that show its significance to the research question(s).

The Results section appears third in the section sequence in most scientific papers. It follows the presentation of the Methods and Materials and is presented before the Discussion section —although the Results and Discussion are presented together in many journals. This section answers the basic question “What did you find in your research?”

What is included in the Results section?

The Results section should include the findings of your study and ONLY the findings of your study. The findings include:

- Data presented in tables, charts, graphs, and other figures (may be placed into the text or on separate pages at the end of the manuscript)

- A contextual analysis of this data explaining its meaning in sentence form

- All data that corresponds to the central research question(s)

- All secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

If the scope of the study is broad, or if you studied a variety of variables, or if the methodology used yields a wide range of different results, the author should present only those results that are most relevant to the research question stated in the Introduction section .

As a general rule, any information that does not present the direct findings or outcome of the study should be left out of this section. Unless the journal requests that authors combine the Results and Discussion sections, explanations and interpretations should be omitted from the Results.

How are the results organized?

The best way to organize your Results section is “logically.” One logical and clear method of organizing research results is to provide them alongside the research questions—within each research question, present the type of data that addresses that research question.

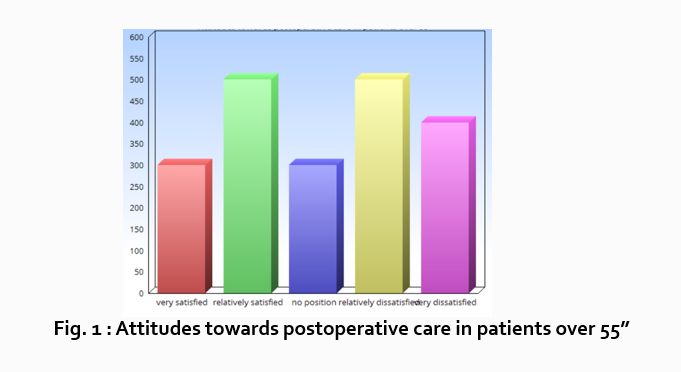

Let’s look at an example. Your research question is based on a survey among patients who were treated at a hospital and received postoperative care. Let’s say your first research question is:

“What do hospital patients over age 55 think about postoperative care?”

This can actually be represented as a heading within your Results section, though it might be presented as a statement rather than a question:

Attitudes towards postoperative care in patients over the age of 55

Now present the results that address this specific research question first. In this case, perhaps a table illustrating data from a survey. Likert items can be included in this example. Tables can also present standard deviations, probabilities, correlation matrices, etc.

Following this, present a content analysis, in words, of one end of the spectrum of the survey or data table. In our example case, start with the POSITIVE survey responses regarding postoperative care, using descriptive phrases. For example:

“Sixty-five percent of patients over 55 responded positively to the question “ Are you satisfied with your hospital’s postoperative care ?” (Fig. 2)

Include other results such as subcategory analyses. The amount of textual description used will depend on how much interpretation of tables and figures is necessary and how many examples the reader needs in order to understand the significance of your research findings.

Next, present a content analysis of another part of the spectrum of the same research question, perhaps the NEGATIVE or NEUTRAL responses to the survey. For instance:

“As Figure 1 shows, 15 out of 60 patients in Group A responded negatively to Question 2.”

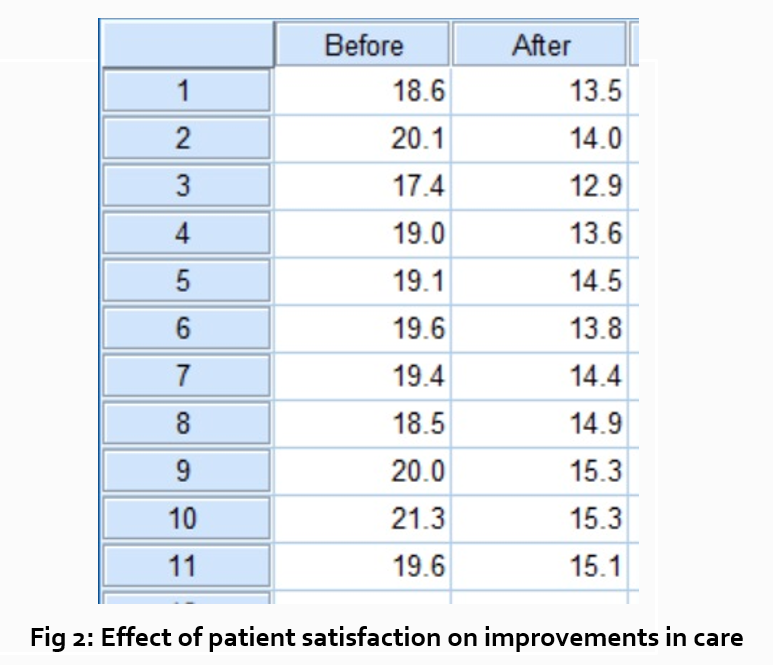

After you have assessed the data in one figure and explained it sufficiently, move on to your next research question. For example:

“How does patient satisfaction correspond to in-hospital improvements made to postoperative care?”

This kind of data may be presented through a figure or set of figures (for instance, a paired T-test table).

Explain the data you present, here in a table, with a concise content analysis:

“The p-value for the comparison between the before and after groups of patients was .03% (Fig. 2), indicating that the greater the dissatisfaction among patients, the more frequent the improvements that were made to postoperative care.”

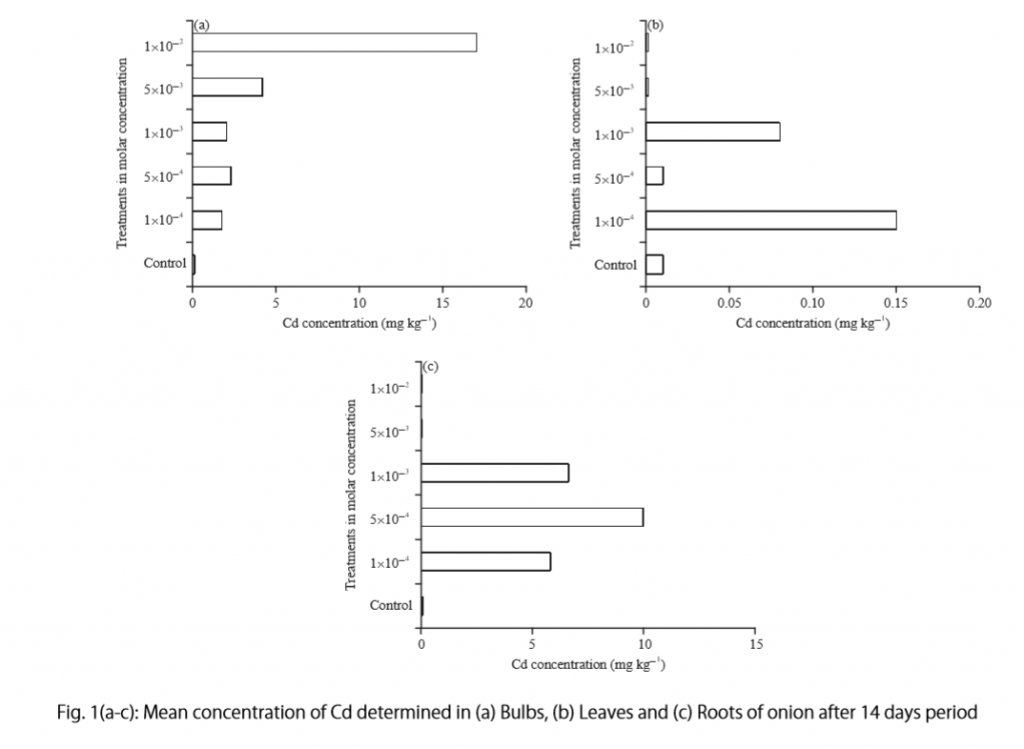

Let’s examine another example of a Results section from a study on plant tolerance to heavy metal stress . In the Introduction section, the aims of the study are presented as “determining the physiological and morphological responses of Allium cepa L. towards increased cadmium toxicity” and “evaluating its potential to accumulate the metal and its associated environmental consequences.” The Results section presents data showing how these aims are achieved in tables alongside a content analysis, beginning with an overview of the findings:

“Cadmium caused inhibition of root and leave elongation, with increasing effects at higher exposure doses (Fig. 1a-c).”

The figure containing this data is cited in parentheses. Note that this author has combined three graphs into one single figure. Separating the data into separate graphs focusing on specific aspects makes it easier for the reader to assess the findings, and consolidating this information into one figure saves space and makes it easy to locate the most relevant results.

Following this overall summary, the relevant data in the tables is broken down into greater detail in text form in the Results section.

- “Results on the bio-accumulation of cadmium were found to be the highest (17.5 mg kgG1) in the bulb, when the concentration of cadmium in the solution was 1×10G2 M and lowest (0.11 mg kgG1) in the leaves when the concentration was 1×10G3 M.”

Captioning and Referencing Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are central components of your Results section and you need to carefully think about the most effective way to use graphs and tables to present your findings . Therefore, it is crucial to know how to write strong figure captions and to refer to them within the text of the Results section.

The most important advice one can give here as well as throughout the paper is to check the requirements and standards of the journal to which you are submitting your work. Every journal has its own design and layout standards, which you can find in the author instructions on the target journal’s website. Perusing a journal’s published articles will also give you an idea of the proper number, size, and complexity of your figures.

Regardless of which format you use, the figures should be placed in the order they are referenced in the Results section and be as clear and easy to understand as possible. If there are multiple variables being considered (within one or more research questions), it can be a good idea to split these up into separate figures. Subsequently, these can be referenced and analyzed under separate headings and paragraphs in the text.

To create a caption, consider the research question being asked and change it into a phrase. For instance, if one question is “Which color did participants choose?”, the caption might be “Color choice by participant group.” Or in our last research paper example, where the question was “What is the concentration of cadmium in different parts of the onion after 14 days?” the caption reads:

“Fig. 1(a-c): Mean concentration of Cd determined in (a) bulbs, (b) leaves, and (c) roots of onions after a 14-day period.”

Steps for Composing the Results Section

Because each study is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to designing a strategy for structuring and writing the section of a research paper where findings are presented. The content and layout of this section will be determined by the specific area of research, the design of the study and its particular methodologies, and the guidelines of the target journal and its editors. However, the following steps can be used to compose the results of most scientific research studies and are essential for researchers who are new to preparing a manuscript for publication or who need a reminder of how to construct the Results section.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the target journal or publisher provides authors and read research papers it has published, especially those with similar topics, methods, or results to your study.

- The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches.

- Note length limitations on restrictions on content. For instance, while many journals require the Results and Discussion sections to be separate, others do not—qualitative research papers often include results and interpretations in the same section (“Results and Discussion”).

- Reading the aims and scope in the journal’s “ guide for authors ” section and understanding the interests of its readers will be invaluable in preparing to write the Results section.

Step 2 : Consider your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements and catalogue your results.

- Focus on experimental results and other findings that are especially relevant to your research questions and objectives and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses.

- Catalogue your findings—use subheadings to streamline and clarify your report. This will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Create appendices that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers.

- Decide how you will structure of your results. You might match the order of the research questions and hypotheses to your results, or you could arrange them according to the order presented in the Methods section. A chronological order or even a hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. Consider your audience, evidence, and most importantly, the objectives of your research when choosing a structure for presenting your findings.

Step 3 : Design figures and tables to present and illustrate your data.

- Tables and figures should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the main text of the paper.

- Information in figures should be relatively self-explanatory (with the aid of captions), and their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for readers to understand the findings without reading all of the text.

- Use tables and figures as a focal point to tell a clear and informative story about your research and avoid repeating information. But remember that while figures clarify and enhance the text, they cannot replace it.

Step 4 : Draft your Results section using the findings and figures you have organized.

- The goal is to communicate this complex information as clearly and precisely as possible; precise and compact phrases and sentences are most effective.

- In the opening paragraph of this section, restate your research questions or aims to focus the reader’s attention to what the results are trying to show. It is also a good idea to summarize key findings at the end of this section to create a logical transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows.

- Try to write in the past tense and the active voice to relay the findings since the research has already been done and the agent is usually clear. This will ensure that your explanations are also clear and logical.

- Make sure that any specialized terminology or abbreviation you have used here has been defined and clarified in the Introduction section .

Step 5 : Review your draft; edit and revise until it reports results exactly as you would like to have them reported to your readers.

- Double-check the accuracy and consistency of all the data, as well as all of the visual elements included.

- Read your draft aloud to catch language errors (grammar, spelling, and mechanics), awkward phrases, and missing transitions.

- Ensure that your results are presented in the best order to focus on objectives and prepare readers for interpretations, valuations, and recommendations in the Discussion section . Look back over the paper’s Introduction and background while anticipating the Discussion and Conclusion sections to ensure that the presentation of your results is consistent and effective.

- Consider seeking additional guidance on your paper. Find additional readers to look over your Results section and see if it can be improved in any way. Peers, professors, or qualified experts can provide valuable insights.

One excellent option is to use a professional English proofreading and editing service such as Wordvice, including our paper editing service . With hundreds of qualified editors from dozens of scientific fields, Wordvice has helped thousands of authors revise their manuscripts and get accepted into their target journals. Read more about the proofreading and editing process before proceeding with getting academic editing services and manuscript editing services for your manuscript.

As the representation of your study’s data output, the Results section presents the core information in your research paper. By writing with clarity and conciseness and by highlighting and explaining the crucial findings of their study, authors increase the impact and effectiveness of their research manuscripts.

For more articles and videos on writing your research manuscript, visit Wordvice’s Resources page.

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

- How it works

How to Write the Dissertation Findings or Results – Steps & Tips

Published by Grace Graffin at August 11th, 2021 , Revised On June 11, 2024

Each part of the dissertation is unique, and some general and specific rules must be followed. The dissertation’s findings section presents the key results of your research without interpreting their meaning .

Theoretically, this is an exciting section of a dissertation because it involves writing what you have observed and found. However, it can be a little tricky if there is too much information to confuse the readers.

The goal is to include only the essential and relevant findings in this section. The results must be presented in an orderly sequence to provide clarity to the readers.

This section of the dissertation should be easy for the readers to follow, so you should avoid going into a lengthy debate over the interpretation of the results.

It is vitally important to focus only on clear and precise observations. The findings chapter of the dissertation is theoretically the easiest to write.

It includes statistical analysis and a brief write-up about whether or not the results emerging from the analysis are significant. This segment should be written in the past sentence as you describe what you have done in the past.

This article will provide detailed information about how to write the findings of a dissertation .

When to Write Dissertation Findings Chapter

As soon as you have gathered and analysed your data, you can start to write up the findings chapter of your dissertation paper. Remember that it is your chance to report the most notable findings of your research work and relate them to the research hypothesis or research questions set out in the introduction chapter of the dissertation .

You will be required to separately report your study’s findings before moving on to the discussion chapter if your dissertation is based on the collection of primary data or experimental work.

However, you may not be required to have an independent findings chapter if your dissertation is purely descriptive and focuses on the analysis of case studies or interpretation of texts.

- Always report the findings of your research in the past tense.

- The dissertation findings chapter varies from one project to another, depending on the data collected and analyzed.

- Avoid reporting results that are not relevant to your research questions or research hypothesis.

Does your Dissertation Have the Following?

- Great Research/Sources

- Perfect Language

- Accurate Sources

If not, we can help. Our panel of experts makes sure to keep the 3 pillars of the Dissertation strong.

1. Reporting Quantitative Findings

The best way to present your quantitative findings is to structure them around the research hypothesis or questions you intend to address as part of your dissertation project.

Report the relevant findings for each research question or hypothesis, focusing on how you analyzed them.

Analysis of your findings will help you determine how they relate to the different research questions and whether they support the hypothesis you formulated.

While you must highlight meaningful relationships, variances, and tendencies, it is important not to guess their interpretations and implications because this is something to save for the discussion and conclusion chapters.

Any findings not directly relevant to your research questions or explanations concerning the data collection process should be added to the dissertation paper’s appendix section.

Use of Figures and Tables in Dissertation Findings

Suppose your dissertation is based on quantitative research. In that case, it is important to include charts, graphs, tables, and other visual elements to help your readers understand the emerging trends and relationships in your findings.

Repeating information will give the impression that you are short on ideas. Refer to all charts, illustrations, and tables in your writing but avoid recurrence.

The text should be used only to elaborate and summarize certain parts of your results. On the other hand, illustrations and tables are used to present multifaceted data.

It is recommended to give descriptive labels and captions to all illustrations used so the readers can figure out what each refers to.

How to Report Quantitative Findings

Here is an example of how to report quantitative results in your dissertation findings chapter;

Two hundred seventeen participants completed both the pretest and post-test and a Pairwise T-test was used for the analysis. The quantitative data analysis reveals a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the pretest and posttest scales from the Teachers Discovering Computers course. The pretest mean was 29.00 with a standard deviation of 7.65, while the posttest mean was 26.50 with a standard deviation of 9.74 (Table 1). These results yield a significance level of .000, indicating a strong treatment effect (see Table 3). With the correlation between the scores being .448, the little relationship is seen between the pretest and posttest scores (Table 2). This leads the researcher to conclude that the impact of the course on the educators’ perception and integration of technology into the curriculum is dramatic.

Paired Samples

| Mean | N | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRESCORE | 29.00 | 217 | 7.65 | .519 | |

| PSTSCORE | 26.00 | 217 | 9.74 | .661 |

Paired Samples Correlation

| N | Correlation | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRESCORE & PSTSCORE | 217 | .448 | .000 |

Paired Samples Test

| Paired Differences | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | |||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Pair 1 | PRESCORE-PSTSCORE | 2.50 | 9.31 | .632 | 1.26 | 3.75 | 3.967 | 216 | .000 |

Also Read: How to Write the Abstract for the Dissertation.

2. Reporting Qualitative Findings

A notable issue with reporting qualitative findings is that not all results directly relate to your research questions or hypothesis.

The best way to present the results of qualitative research is to frame your findings around the most critical areas or themes you obtained after you examined the data.

In-depth data analysis will help you observe what the data shows for each theme. Any developments, relationships, patterns, and independent responses directly relevant to your research question or hypothesis should be mentioned to the readers.

Additional information not directly relevant to your research can be included in the appendix .

How to Report Qualitative Findings

Here is an example of how to report qualitative results in your dissertation findings chapter;

The last question of the interview focused on the need for improvement in Thai ready-to-eat products and the industry at large, emphasizing the need for enhancement in the current products being offered in the market. When asked if there was any particular need for Thai ready-to-eat meals to be improved and how to improve them in case of ‘yes,’ the males replied mainly by saying that the current products need improvement in terms of the use of healthier raw materials and preservatives or additives. There was an agreement amongst all males concerning the need to improve the industry for ready-to-eat meals and the use of more healthy items to prepare such meals. The females were also of the opinion that the fast-food items needed to be improved in the sense that more healthy raw materials such as vegetable oil and unsaturated fats, including whole-wheat products, to overcome risks associated with trans fat leading to obesity and hypertension should be used for the production of RTE products. The frozen RTE meals and packaged snacks included many preservatives and chemical-based flavouring enhancers that harmed human health and needed to be reduced. The industry is said to be aware of this fact and should try to produce RTE products that benefit the community in terms of healthy consumption.

Looking for dissertation help?

Research prospect to the rescue then.

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with dissertations across a variety of disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

What to Avoid in Dissertation Findings Chapter

- Avoid using interpretive and subjective phrases and terms such as “confirms,” “reveals,” “suggests,” or “validates.” These terms are more suitable for the discussion chapter , where you will be expected to interpret the results in detail.

- Only briefly explain findings in relation to the key themes, hypothesis, and research questions. You don’t want to write a detailed subjective explanation for any research questions at this stage.

The Do’s of Writing the Findings or Results Section

- Ensure you are not presenting results from other research studies in your findings.

- Observe whether or not your hypothesis is tested or research questions answered.

- Illustrations and tables present data and are labelled to help your readers understand what they relate to.

- Use software such as Excel, STATA, and SPSS to analyse results and important trends.

Essential Guidelines on How to Write Dissertation Findings

The dissertation findings chapter should provide the context for understanding the results. The research problem should be repeated, and the research goals should be stated briefly.

This approach helps to gain the reader’s attention toward the research problem. The first step towards writing the findings is identifying which results will be presented in this section.

The results relevant to the questions must be presented, considering whether the results support the hypothesis. You do not need to include every result in the findings section. The next step is ensuring the data can be appropriately organized and accurate.

You will need to have a basic idea about writing the findings of a dissertation because this will provide you with the knowledge to arrange the data chronologically.

Start each paragraph by writing about the most important results and concluding the section with the most negligible actual results.

A short paragraph can conclude the findings section, summarising the findings so readers will remember as they transition to the next chapter. This is essential if findings are unexpected or unfamiliar or impact the study.

Our writers can help you with all parts of your dissertation, including statistical analysis of your results . To obtain free non-binding quotes, please complete our online quote form here .

Be Impartial in your Writing

When crafting your findings, knowing how you will organize the work is important. The findings are the story that needs to be told in response to the research questions that have been answered.

Therefore, the story needs to be organized to make sense to you and the reader. The findings must be compelling and responsive to be linked to the research questions being answered.

Always ensure that the size and direction of any changes, including percentage change, can be mentioned in the section. The details of p values or confidence intervals and limits should be included.

The findings sections only have the relevant parts of the primary evidence mentioned. Still, it is a good practice to include all the primary evidence in an appendix that can be referred to later.

The results should always be written neutrally without speculation or implication. The statement of the results mustn’t have any form of evaluation or interpretation.

Negative results should be added in the findings section because they validate the results and provide high neutrality levels.

The length of the dissertation findings chapter is an important question that must be addressed. It should be noted that the length of the section is directly related to the total word count of your dissertation paper.

The writer should use their discretion in deciding the length of the findings section or refer to the dissertation handbook or structure guidelines.

It should neither belong nor be short nor concise and comprehensive to highlight the reader’s main findings.

Ethically, you should be confident in the findings and provide counter-evidence. Anything that does not have sufficient evidence should be discarded. The findings should respond to the problem presented and provide a solution to those questions.

Structure of the Findings Chapter

The chapter should use appropriate words and phrases to present the results to the readers. Logical sentences should be used, while paragraphs should be linked to produce cohesive work.

You must ensure all the significant results have been added in the section. Recheck after completing the section to ensure no mistakes have been made.

The structure of the findings section is something you may have to be sure of primarily because it will provide the basis for your research work and ensure that the discussions section can be written clearly and proficiently.

One way to arrange the results is to provide a brief synopsis and then explain the essential findings. However, there should be no speculation or explanation of the results, as this will be done in the discussion section.

Another way to arrange the section is to present and explain a result. This can be done for all the results while the section is concluded with an overall synopsis.

This is the preferred method when you are writing more extended dissertations. It can be helpful when multiple results are equally significant. A brief conclusion should be written to link all the results and transition to the discussion section.

Numerous data analysis dissertation examples are available on the Internet, which will help you improve your understanding of writing the dissertation’s findings.

Problems to Avoid When Writing Dissertation Findings

One of the problems to avoid while writing the dissertation findings is reporting background information or explaining the findings. This should be done in the introduction section .

You can always revise the introduction chapter based on the data you have collected if that seems an appropriate thing to do.

Raw data or intermediate calculations should not be added in the findings section. Always ask your professor if raw data needs to be included.

If the data is to be included, then use an appendix or a set of appendices referred to in the text of the findings chapter.

Do not use vague or non-specific phrases in the findings section. It is important to be factual and concise for the reader’s benefit.

The findings section presents the crucial data collected during the research process. It should be presented concisely and clearly to the reader. There should be no interpretation, speculation, or analysis of the data.

The significant results should be categorized systematically with the text used with charts, figures, and tables. Furthermore, avoiding using vague and non-specific words in this section is essential.

It is essential to label the tables and visual material properly. You should also check and proofread the section to avoid mistakes.

The dissertation findings chapter is a critical part of your overall dissertation paper. If you struggle with presenting your results and statistical analysis, our expert dissertation writers can help you get things right. Whether you need help with the entire dissertation paper or individual chapters, our dissertation experts can provide customized dissertation support .

FAQs About Findings of a Dissertation

How do i report quantitative findings.

The best way to present your quantitative findings is to structure them around the research hypothesis or research questions you intended to address as part of your dissertation project. Report the relevant findings for each of the research questions or hypotheses, focusing on how you analyzed them.

How do I report qualitative findings?

The best way to present the qualitative research results is to frame your findings around the most important areas or themes that you obtained after examining the data.

An in-depth analysis of the data will help you observe what the data is showing for each theme. Any developments, relationships, patterns, and independent responses that are directly relevant to your research question or hypothesis should be clearly mentioned for the readers.

Can I use interpretive phrases like ‘it confirms’ in the finding chapter?

No, It is highly advisable to avoid using interpretive and subjective phrases in the finding chapter. These terms are more suitable for the discussion chapter , where you will be expected to provide your interpretation of the results in detail.

Can I report the results from other research papers in my findings chapter?

NO, you must not be presenting results from other research studies in your findings.

You May Also Like

Finding it difficult to maintain a good relationship with your supervisor? Here are some tips on ‘How to Deal with an Unhelpful Dissertation Supervisor’.

This brief introductory section aims to deal with the definitions of two paradigms, positivism and post-positivism, as well as their importance in research.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Table of Contents

Research Report

Definition:

Research Report is a written document that presents the results of a research project or study, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions, in a clear and objective manner.

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the findings of the research to the intended audience, which could be other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public.

Components of Research Report

Components of Research Report are as follows:

Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for the research report and provides a brief overview of the research question or problem being investigated. It should include a clear statement of the purpose of the study and its significance or relevance to the field of research. It may also provide background information or a literature review to help contextualize the research.

Literature Review

The literature review provides a critical analysis and synthesis of the existing research and scholarship relevant to the research question or problem. It should identify the gaps, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the literature and show how the current study addresses these issues. The literature review also establishes the theoretical framework or conceptual model that guides the research.

Methodology

The methodology section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used to collect and analyze data. It should include information on the sample or participants, data collection instruments, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques. The methodology should be clear and detailed enough to allow other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the study in a clear and objective manner. It should provide a detailed description of the data and statistics used to answer the research question or test the hypothesis. Tables, graphs, and figures may be included to help visualize the data and illustrate the key findings.

The discussion section interprets the results of the study and explains their significance or relevance to the research question or problem. It should also compare the current findings with those of previous studies and identify the implications for future research or practice. The discussion should be based on the results presented in the previous section and should avoid speculation or unfounded conclusions.

The conclusion summarizes the key findings of the study and restates the main argument or thesis presented in the introduction. It should also provide a brief overview of the contributions of the study to the field of research and the implications for practice or policy.

The references section lists all the sources cited in the research report, following a specific citation style, such as APA or MLA.

The appendices section includes any additional material, such as data tables, figures, or instruments used in the study, that could not be included in the main text due to space limitations.

Types of Research Report

Types of Research Report are as follows:

Thesis is a type of research report. A thesis is a long-form research document that presents the findings and conclusions of an original research study conducted by a student as part of a graduate or postgraduate program. It is typically written by a student pursuing a higher degree, such as a Master’s or Doctoral degree, although it can also be written by researchers or scholars in other fields.

Research Paper

Research paper is a type of research report. A research paper is a document that presents the results of a research study or investigation. Research papers can be written in a variety of fields, including science, social science, humanities, and business. They typically follow a standard format that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion sections.

Technical Report

A technical report is a detailed report that provides information about a specific technical or scientific problem or project. Technical reports are often used in engineering, science, and other technical fields to document research and development work.

Progress Report

A progress report provides an update on the progress of a research project or program over a specific period of time. Progress reports are typically used to communicate the status of a project to stakeholders, funders, or project managers.

Feasibility Report

A feasibility report assesses the feasibility of a proposed project or plan, providing an analysis of the potential risks, benefits, and costs associated with the project. Feasibility reports are often used in business, engineering, and other fields to determine the viability of a project before it is undertaken.

Field Report

A field report documents observations and findings from fieldwork, which is research conducted in the natural environment or setting. Field reports are often used in anthropology, ecology, and other social and natural sciences.

Experimental Report

An experimental report documents the results of a scientific experiment, including the hypothesis, methods, results, and conclusions. Experimental reports are often used in biology, chemistry, and other sciences to communicate the results of laboratory experiments.

Case Study Report

A case study report provides an in-depth analysis of a specific case or situation, often used in psychology, social work, and other fields to document and understand complex cases or phenomena.

Literature Review Report

A literature review report synthesizes and summarizes existing research on a specific topic, providing an overview of the current state of knowledge on the subject. Literature review reports are often used in social sciences, education, and other fields to identify gaps in the literature and guide future research.

Research Report Example

Following is a Research Report Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Academic Performance among High School Students

This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students. The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The findings indicate that there is a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students. The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers, as they highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities.

Introduction:

Social media has become an integral part of the lives of high school students. With the widespread use of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat, students can connect with friends, share photos and videos, and engage in discussions on a range of topics. While social media offers many benefits, concerns have been raised about its impact on academic performance. Many studies have found a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance among high school students (Kirschner & Karpinski, 2010; Paul, Baker, & Cochran, 2012).

Given the growing importance of social media in the lives of high school students, it is important to investigate its impact on academic performance. This study aims to address this gap by examining the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students.

Methodology:

The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The questionnaire was developed based on previous studies and was designed to measure the frequency and duration of social media use, as well as academic performance.

The participants were selected using a convenience sampling technique, and the survey questionnaire was distributed in the classroom during regular school hours. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

The findings indicate that the majority of high school students use social media platforms on a daily basis, with Facebook being the most popular platform. The results also show a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students.

Discussion:

The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. The negative correlation between social media use and academic performance suggests that strategies should be put in place to help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. For example, educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this study provides evidence of the negative impact of social media on academic performance among high school students. The findings highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. Further research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which social media use affects academic performance and to develop effective strategies for addressing this issue.

Limitations:

One limitation of this study is the use of convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future studies should use random sampling techniques to increase the representativeness of the sample. Another limitation is the use of self-reported measures, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Future studies could use objective measures of social media use and academic performance, such as tracking software and school records.

Implications:

The findings of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. Educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. For example, teachers could use social media platforms to share relevant educational resources and facilitate online discussions. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. They could also engage in open communication with their children to understand their social media use and its impact on their academic performance. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students. For example, schools could implement social media policies that restrict access during class time and encourage responsible use.

References:

- Kirschner, P. A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2010). Facebook® and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1237-1245.

- Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Journal of the Research Center for Educational Technology, 8(1), 1-19.

- Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(10), 652-657.

- Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., & Cheever, N. A. (2013). Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 948-958.

Note*: Above mention, Example is just a sample for the students’ guide. Do not directly copy and paste as your College or University assignment. Kindly do some research and Write your own.

Applications of Research Report

Research reports have many applications, including:

- Communicating research findings: The primary application of a research report is to communicate the results of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public. The report serves as a way to share new knowledge, insights, and discoveries with others in the field.

- Informing policy and practice : Research reports can inform policy and practice by providing evidence-based recommendations for decision-makers. For example, a research report on the effectiveness of a new drug could inform regulatory agencies in their decision-making process.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research in a particular area. Other researchers may use the findings and methodology of a report to develop new research questions or to build on existing research.

- Evaluating programs and interventions : Research reports can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and interventions in achieving their intended outcomes. For example, a research report on a new educational program could provide evidence of its impact on student performance.

- Demonstrating impact : Research reports can be used to demonstrate the impact of research funding or to evaluate the success of research projects. By presenting the findings and outcomes of a study, research reports can show the value of research to funders and stakeholders.

- Enhancing professional development : Research reports can be used to enhance professional development by providing a source of information and learning for researchers and practitioners in a particular field. For example, a research report on a new teaching methodology could provide insights and ideas for educators to incorporate into their own practice.

How to write Research Report

Here are some steps you can follow to write a research report:

- Identify the research question: The first step in writing a research report is to identify your research question. This will help you focus your research and organize your findings.

- Conduct research : Once you have identified your research question, you will need to conduct research to gather relevant data and information. This can involve conducting experiments, reviewing literature, or analyzing data.

- Organize your findings: Once you have gathered all of your data, you will need to organize your findings in a way that is clear and understandable. This can involve creating tables, graphs, or charts to illustrate your results.

- Write the report: Once you have organized your findings, you can begin writing the report. Start with an introduction that provides background information and explains the purpose of your research. Next, provide a detailed description of your research methods and findings. Finally, summarize your results and draw conclusions based on your findings.

- Proofread and edit: After you have written your report, be sure to proofread and edit it carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, and make sure that your report is well-organized and easy to read.

- Include a reference list: Be sure to include a list of references that you used in your research. This will give credit to your sources and allow readers to further explore the topic if they choose.

- Format your report: Finally, format your report according to the guidelines provided by your instructor or organization. This may include formatting requirements for headings, margins, fonts, and spacing.

Purpose of Research Report

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the results of a research study to a specific audience, such as peers in the same field, stakeholders, or the general public. The report provides a detailed description of the research methods, findings, and conclusions.

Some common purposes of a research report include:

- Sharing knowledge: A research report allows researchers to share their findings and knowledge with others in their field. This helps to advance the field and improve the understanding of a particular topic.

- Identifying trends: A research report can identify trends and patterns in data, which can help guide future research and inform decision-making.

- Addressing problems: A research report can provide insights into problems or issues and suggest solutions or recommendations for addressing them.

- Evaluating programs or interventions : A research report can evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions, which can inform decision-making about whether to continue, modify, or discontinue them.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies.

When to Write Research Report

A research report should be written after completing the research study. This includes collecting data, analyzing the results, and drawing conclusions based on the findings. Once the research is complete, the report should be written in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

In academic settings, research reports are often required as part of coursework or as part of a thesis or dissertation. In this case, the report should be written according to the guidelines provided by the instructor or institution.

In other settings, such as in industry or government, research reports may be required to inform decision-making or to comply with regulatory requirements. In these cases, the report should be written as soon as possible after the research is completed in order to inform decision-making in a timely manner.

Overall, the timing of when to write a research report depends on the purpose of the research, the expectations of the audience, and any regulatory requirements that need to be met. However, it is important to complete the report in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

Characteristics of Research Report

There are several characteristics of a research report that distinguish it from other types of writing. These characteristics include:

- Objective: A research report should be written in an objective and unbiased manner. It should present the facts and findings of the research study without any personal opinions or biases.

- Systematic: A research report should be written in a systematic manner. It should follow a clear and logical structure, and the information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand and follow.

- Detailed: A research report should be detailed and comprehensive. It should provide a thorough description of the research methods, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research report should be accurate and based on sound research methods. The findings and conclusions should be supported by data and evidence.

- Organized: A research report should be well-organized. It should include headings and subheadings to help the reader navigate the report and understand the main points.

- Clear and concise: A research report should be written in clear and concise language. The information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand, and unnecessary jargon should be avoided.

- Citations and references: A research report should include citations and references to support the findings and conclusions. This helps to give credit to other researchers and to provide readers with the opportunity to further explore the topic.

Advantages of Research Report

Research reports have several advantages, including:

- Communicating research findings: Research reports allow researchers to communicate their findings to a wider audience, including other researchers, stakeholders, and the general public. This helps to disseminate knowledge and advance the understanding of a particular topic.

- Providing evidence for decision-making : Research reports can provide evidence to inform decision-making, such as in the case of policy-making, program planning, or product development. The findings and conclusions can help guide decisions and improve outcomes.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research on a particular topic. Other researchers can build on the findings and conclusions of the report, which can lead to further discoveries and advancements in the field.

- Demonstrating expertise: Research reports can demonstrate the expertise of the researchers and their ability to conduct rigorous and high-quality research. This can be important for securing funding, promotions, and other professional opportunities.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies. Producing a high-quality research report can help ensure compliance with these requirements.

Limitations of Research Report

Despite their advantages, research reports also have some limitations, including:

- Time-consuming: Conducting research and writing a report can be a time-consuming process, particularly for large-scale studies. This can limit the frequency and speed of producing research reports.

- Expensive: Conducting research and producing a report can be expensive, particularly for studies that require specialized equipment, personnel, or data. This can limit the scope and feasibility of some research studies.

- Limited generalizability: Research studies often focus on a specific population or context, which can limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or contexts.

- Potential bias : Researchers may have biases or conflicts of interest that can influence the findings and conclusions of the research study. Additionally, participants may also have biases or may not be representative of the larger population, which can limit the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Accessibility: Research reports may be written in technical or academic language, which can limit their accessibility to a wider audience. Additionally, some research may be behind paywalls or require specialized access, which can limit the ability of others to read and use the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates...

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and...

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

Writing a Research Paper Conclusion | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on October 30, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on April 13, 2023.

- Restate the problem statement addressed in the paper

- Summarize your overall arguments or findings

- Suggest the key takeaways from your paper

The content of the conclusion varies depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument through engagement with sources .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: restate the problem, step 2: sum up the paper, step 3: discuss the implications, research paper conclusion examples, frequently asked questions about research paper conclusions.

The first task of your conclusion is to remind the reader of your research problem . You will have discussed this problem in depth throughout the body, but now the point is to zoom back out from the details to the bigger picture.

While you are restating a problem you’ve already introduced, you should avoid phrasing it identically to how it appeared in the introduction . Ideally, you’ll find a novel way to circle back to the problem from the more detailed ideas discussed in the body.

For example, an argumentative paper advocating new measures to reduce the environmental impact of agriculture might restate its problem as follows:

Meanwhile, an empirical paper studying the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues might present its problem like this:

“In conclusion …”

Avoid starting your conclusion with phrases like “In conclusion” or “To conclude,” as this can come across as too obvious and make your writing seem unsophisticated. The content and placement of your conclusion should make its function clear without the need for additional signposting.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Having zoomed back in on the problem, it’s time to summarize how the body of the paper went about addressing it, and what conclusions this approach led to.

Depending on the nature of your research paper, this might mean restating your thesis and arguments, or summarizing your overall findings.

Argumentative paper: Restate your thesis and arguments

In an argumentative paper, you will have presented a thesis statement in your introduction, expressing the overall claim your paper argues for. In the conclusion, you should restate the thesis and show how it has been developed through the body of the paper.

Briefly summarize the key arguments made in the body, showing how each of them contributes to proving your thesis. You may also mention any counterarguments you addressed, emphasizing why your thesis holds up against them, particularly if your argument is a controversial one.

Don’t go into the details of your evidence or present new ideas; focus on outlining in broad strokes the argument you have made.

Empirical paper: Summarize your findings

In an empirical paper, this is the time to summarize your key findings. Don’t go into great detail here (you will have presented your in-depth results and discussion already), but do clearly express the answers to the research questions you investigated.

Describe your main findings, even if they weren’t necessarily the ones you expected or hoped for, and explain the overall conclusion they led you to.