- Account details

- Follow topics

- Saved articles

- Newsletters

- Help Centre

- Subscriber rewards

You are currently accessing Central Banking via your Enterprise account.

If you already have an account please use the link below to sign in .

If you have any problems with your access or would like to request an individual access account please contact our customer service team.

Phone: 1+44 (0)870 240 8859

Email: [email protected]

Monetary policy

- Monetary Policy

PBoC looks into narrowing interest rate corridor

Central bank elaborates on recent changes to monetary policy framework.

- 12 Aug 2024

Central banks need to avoid ‘overconfidence’, says RBA’s Hauser

Bank of Uganda cuts rates by 25bp

- 09 Aug 2024

Romania cuts rates by 25bp

- 08 Aug 2024

Monetary policy has less impact on private credit – Fed research

Funding, ‘dry powder’ and fund returns for asset class remain high amid policy tightening

- 07 Aug 2024

CBDCs amplify contractionary effects of monetary shocks – BoC paper

However, research finds no substantial change to transmission mechanism

- Financial Stability

Japanese officials pledge vigilance on financial markets

BoJ, finance ministry and regulator hold emergency meeting after country’s biggest fall in equities since 1987

- 06 Aug 2024

Czech National Bank cuts rates to 4.5%

Reduction of 25bp comes after headline inflation falls to 2% target

- 02 Aug 2024

Bank of England cuts rates for first time since 2020

MPC votes for 25bp reduction in split decision after Fed opts to hold

- 01 Aug 2024

LatAm rates round-up: Brazil and Chile hold while Colombia cuts

Central banks maintain cautious stance as disinflation slows across region

Fed holds rates again

Powell says FOMC’s “broad sense” is that US economy is moving to point where cuts would be justified

Azerbaijan holds key policy rate

Inflation still significantly below target levels

- 31 Jul 2024

National Bank of Georgia holds rates

Move comes as inflation remains well below 3% target

BIS Americas chief: region must stay alert to inflation risks

Tombini praises efforts to tackle inflation, while outlining monetary policy challenges

BoJ raises policy rate, outlines plan to reduce bond purchases

Governor says bank will raise rates again if economy and prices move in line with projections

- Financial reporting

Central banks face a capital framework imbalance – should we care?

Most economists say clear recapitalisation frameworks are important. But many central banks still lack them

Armenia cuts rates by 25bp

Decision comes as inflation remains well below 4% target

- 30 Jul 2024

Euro has given France better interest rates – BdF official

Bénassy-Quéré says rates would have been higher if France had stayed outside single currency

- Macroeconomics

Falling r* a ‘mirage’ in open economies – IMF paper

Adding exchange rate to standard model significantly changes predictions, authors find

- 29 Jul 2024

Pakistan cuts rates by 100 basis points

Decision comes after country secures IMF funding amid falling oil prices

Singapore leaves monetary policy unchanged

Decision comes despite moderation in domestic inflation

- 26 Jul 2024

Bank of Russia hikes interest rates by 200bp

Labour shortage continues to grow under war economy

Eddie Yue reappointed as head of Hong Kong Monetary Authority

Chief executive says HKMA will promote stability amid “complex” economic and geopolitical environment

- Monetary policy decisions

Uzbekistan reduces policy rate by 50bp

Central bank delivers first cut since May 2023

You need to sign in to use this feature. If you don’t have a Central Banking account, please register for a trial.

You are currently on corporate access.

To use this feature you will need an individual account. If you have one already please sign in.

Alternatively you can request an individual account

Monetary Policy

Monetary policy refers to the Federal Reserve's actions and communications to promote maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates.

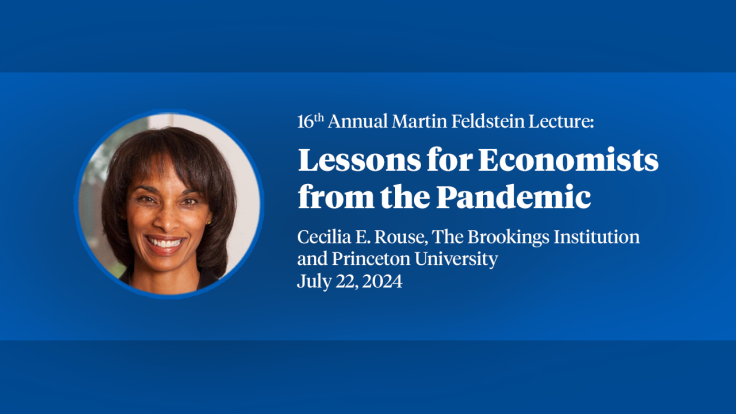

Economist Raghuram Rajan on leading a central bank, creating a digital payment system, and India's future in professional services.

David A. Price

Milton Friedman, the architect of modern monetarism and an advocate for free markets, was an energetic public intellectual who greatly influenced economics.

Julian Kikuchi

President Tom Barkin explores why it has been particularly challenging to predict the path of the economy over the last few years.

Tom Barkin President, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

Economic policy uncertainty rises significantly leading up to an election and stays elevated for a couple months after the election is over.

Marina Azzimonti

What are early studies suggesting about how AI may impact labor productivity?

Andreas Hornstein

Demographic factors can simultaneously work in opposite directions when it comes to r*.

Alexander Wolman discusses the Federal Reserve's establishment of an inflation target in 2012 and how that has fit within the Fed's evolving monetary policy framework. Wolman is vice president for monetary and macroeconomic research at the Richmond Fed.

President Tom Barkin reflects on recent data and shares his view on where the U.S. economy is headed.

Some think such a trap for China is imminent, due to factors such as a surge in deposits, mounting deflationary pressures and high youth unemployment rates.

Russell Wong

Taking into account the uncertainty of the state of the world is the hallmark of good policymaking in economics. Moreover, r* and other stars are just one of many inputs in this process.

Thomas A. Lubik

It's easy to see why people might differ on the path forward for the economy — each forecaster sees the future through his or her own lens.

Tom Barkin President and Chief Executive Officer

The FOMC established its explicit inflation target in January 2012 after a decades-long deliberation. It came in part from the Richmond Fed.

Matthew Wells

President Tom Barkin explores different ways to look at recent data, and then gives his own perspective.

The pattern of r* paths for other countries seem more alike to each other than they are to the U.S.

Thomas A. Lubik , Brennan Merone and Nathan Robino

Recent data have been remarkable. President Tom Barkin shares why he still sees reasons for caution.

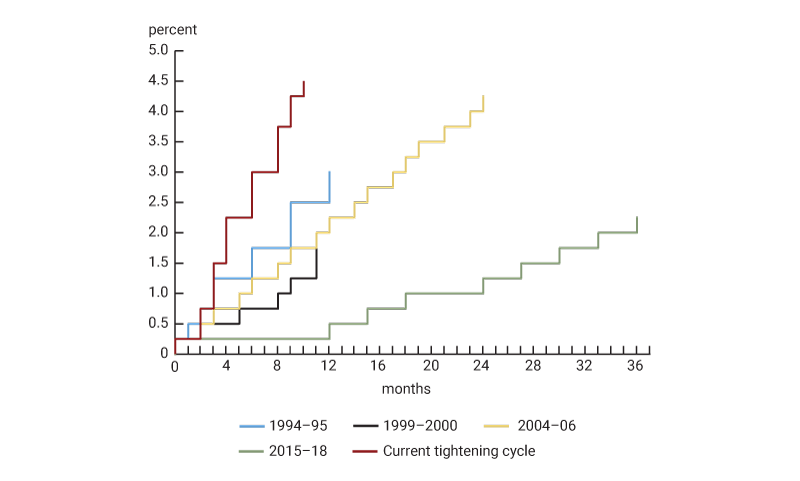

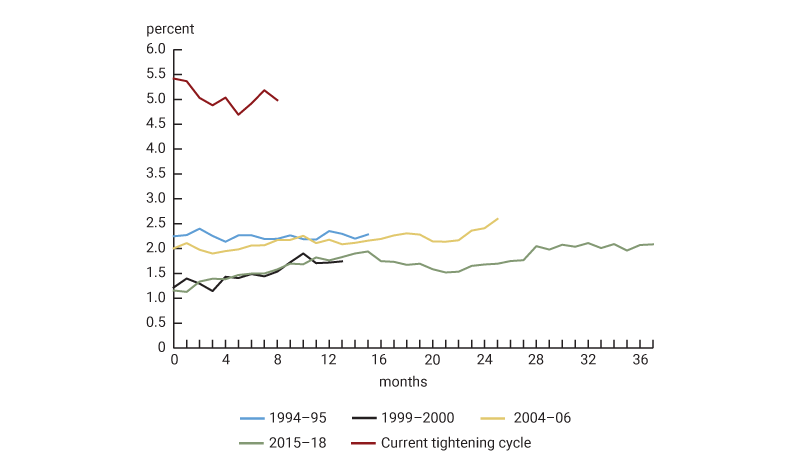

How has the economy navigated previous rate cycles, and how do they compare to the current one?

Erin Henry , Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte and Jack Taylor

Thomas Lubik and Christian Matthes discuss how economists wrestle with measuring the natural rate of interest or r-star, why this measure is important for monetary policymakers, and how their model has evolved to better chart the path of interest rates. Lubik is a senior advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and Matthes is a professor of economics at Indiana University.

President Tom Barkin reflects on 2023 and shares his outlook for the year ahead.

The Reserve Bank boards of directors are a key link between the Federal Reserve System and the communities it serves, working to achieve the dual mandate and formulate monetary policy.

President Tom Barkin shares how communities in the Fifth District are working to move the needle on housing.

Paul Ho talks about how countries are connected to each other through international trade and how these connections help spread economic shocks across the globe. Ho is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

President Tom Barkin explores potential paths for the U.S. economy and their implications for monetary policy.

Richmond Fed leaders and Federal Reserve Governor Michelle Bowman heard business and community leaders' perspectives on the state of the local economy.

Richmond Fed president Tom Barkin and Federal Reserve Board Governor Michelle Bowman will lead a discussion about the lingering impact of the pandemic on the economy and the workforce. The general public is invited to listen in, via livestream, as Barkin, Bowman and several special guests explore the challenges and opportunities that exist as the region served by the Richmond Fed continues the transition to a new normal.

President Tom Barkin discusses what he is hearing on the ground from Fifth District contacts, and how it compares to recent data.

President Tom Barkin explores what’s happening in the labor market and how it could impact the path ahead.

The updates result in a less volatile r* series that more closely reflects our prior belief as to where r* likely is.

Thomas A. Lubik and Christian Matthes

Sonya Waddell and Chen Yeh provide an update on credit market conditions, based on recent results of the CFO Survey and other surveys of borrowers and lenders. They also discuss the macroeconomic forces that shape the supply and demand sides of the market, including the current round of monetary policy tightening. Waddell is a vice president and economist and Yeh is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

What is the typical lag between market interest rate increases and increases in CD and MMMF balances? Is the recent increase unusually large, or is more in store?

Alexander L. Wolman

Paul Ho talks about how economists model the interactions between monetary policy and the economy and the challenges of determining the economic effects of policy with precision. Ho is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

President Tom Barkin discusses what’s driving the resilient U.S. economy and where it may be headed next.

How do the Fed's interest rate hikes affect bank lending standards? One way to find out is to directly ask banks whether they've tightened lending standards to borrowers.

John O'Trakoun Senior Policy Economist

President Tom Barkin explores a plausible story for how inflation returns to target.

In his July 1832 veto message of the bill rechartering the Second Bank of the United States, President Andrew Jackson triggered the demise of America's second central bank with a stroke of his veto pen.

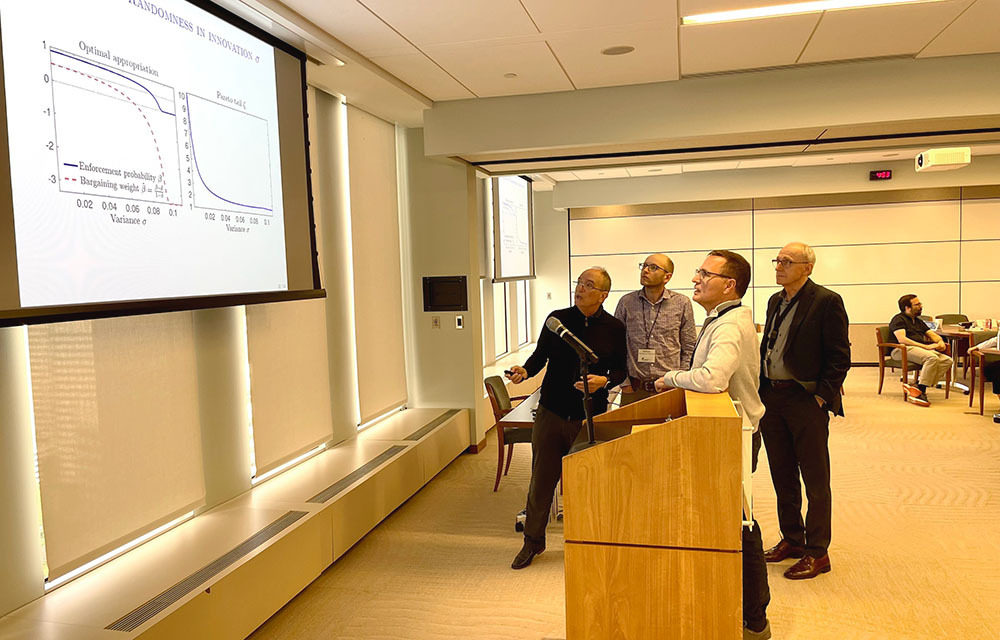

The Richmond Fed hosted CORE Week and also launched the Goodfriend Memorial Lecture in early May.

Even though economists have made huge leaps in understanding how monetary policy impacts the economy, there remains substantial disagreement and imprecision in the estimates.

This paper evaluates the welfare effects of unemployment insurance in general equilibrium using a life-cycle model.

Facundo Piguillem , Hernán Ruffo and Nicholas Trachter

Do relative price changes account for the behavior of inflation in the pandemic and post-pandemic eras?

President Tom Barkin discusses recent data and events and explores potential implications for monetary policy.

In part two of this two-part conversation, Robert Hetzel focuses on the Fed's policies during the Great Inflation and the Great Moderation and after the Great Recession, as well as the role of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond during these periods.

In part one of this two-part conversation, Robert Hetzel discusses the Fed's policy shifts in the two decades following the Treasury-Fed Accord of 1951 and the role of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond during that period.

Market commentors noticed a pattern during Alan Greenspan's tenure as Fed chair from 1987 to 2006. The Fed, it appeared to some, had developed a policy of bailing out stock investors by injecting liquidity into the economy amid large stock market declines. This perceived tendency came to be called the "Greenspan put."

John Mullin

President Tom Barkin discusses how he sees the economy, and the implications for inflation and for policy.

Moves toward stable inflation and maximum employment can be in conflict in the short term.

Felipe F. Schwartzman

Just by allowing the securities in its portfolio to mature, the Fed could reach a normalized size of its balance sheet in two to three years.

Huberto M. Ennis and Tre' McMillan

Tom Barkin discusses the state of inflation and the monetary policy response of the Federal Reserve, as well as his outlook on the national economy. Barkin is president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

President Tom Barkin reflects on monetary policy and the economy in 2022 and shares his thoughts on what’s ahead.

Huberto Ennis explores how the Federal Reserve used its asset purchases to deal with market disruptions and the unprecedented economic issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic. He also discusses why and how the Fed is unwinding these purchases. Ennis is group vice president for macro and financial economics at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The past few years have seen unprecedented real economy shocks, which are particularly hard to deal with for any central bank, and so drove a lot of the inflation in the wake of the pandemic's arrival.

Kartik Athreya Executive Vice President and Director of Research

For the first time in more than a generation, we are grappling with high, broad-based, and persistent inflation. Is there an end in sight?

While the Fed has never been a stranger to criticism, the criticism has been notable and specific during the past year. The subject: inflation.

Kartik B. Athreya

Talking about the future has become a valuable tool of monetary policy, but recent events have prompted a reevaluation.

John O'Trakoun and Pierre-Daniel Sarte discuss the persistence of inflation over the years and what may set apart the current period of elevated prices compared to historical patterns. O'Trakoun is a senior policy economist and Sarte is a senior advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Techniques at the frontiers of econometrics were addressed by economists during a recent research conference.

Kartik Athreya responds to recent critiques of the Federal Reserve and its efforts to combat inflation. Athreya is executive vice president and director of research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The newer a product is, the more likely its price will change and the larger the price change will likely be.

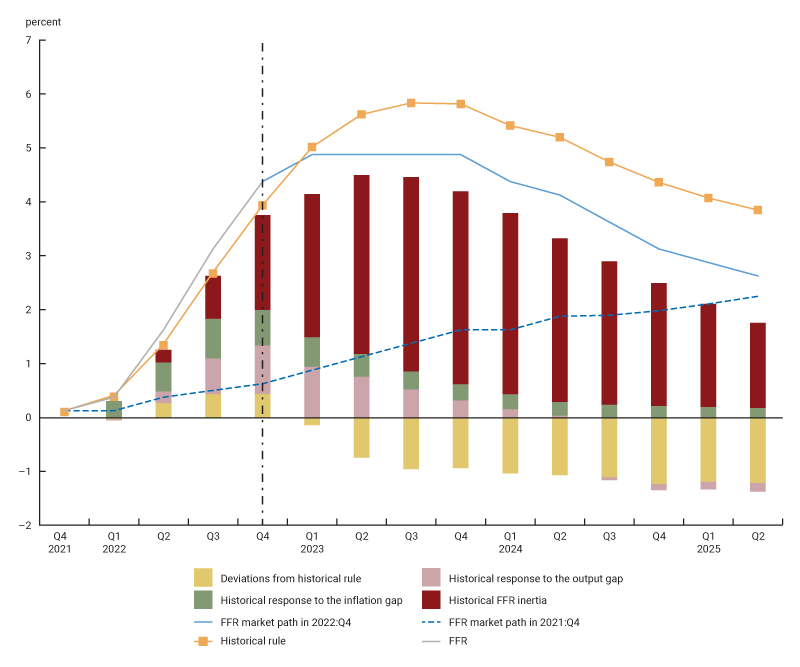

Declining gasoline prices have contributed to an easing of inflation and lower inflation expectations, working in tandem with the FOMC's efforts to bring price levels down. But how hard is monetary policy tapping on the brakes of the economy?

President Tom Barkin considers the forces behind today’s high inflation and offers his outlook for the economy.

Learn about key trends and considerations related to balance sheet management and interest rate risk practices in a highly dynamic economic environment.

Greg Dodt and Mina Oldham

This theory may be obscure, even to economists, but it can have quite an impact on inflation.

One can argue whether the FOMC's response to inflation has been strong enough, but financial markets and surveys suggest that the Fed retains credibility for low inflation in the long run.

While the Fed has experience buying assets to respond to crises, questions remain around unwinding those actions

Today's inflationary snarls reflect both supply shocks and policy stimulus.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell has stressed that monetary policy is a blunt instrument and using it to bring down inflation could entail some short-term pain. This risk, though, must be compared with outcomes that would confront the Fed and the economy were clear action not forthcoming.

Columbia University economist on inflation, capital controls, and finding research topics.

Given the critical role that Reserve Bank presidents play in formulating monetary policy, the Federal Reserve has taken steps to ensure that the presidential selection process is transparent, fair, and inclusive.

Chris Murphy

How might a CBDC alter the banking system? How does credit easing affect bank runs? These and other questions were addressed during a recent Richmond Fed conference.

John Mullin and Matthew Wells

Inflation has hit most other advanced economies in addition to the United States. What can we learn from their experiences?

Thomas A. Lubik and Alexander L. Wolman

Persistence in inflation depends on the time period studied.

Conner Mulloy , John O'Trakoun and Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte

President Tom Barkin outlines how he expects inflation to come down.

John O'Trakoun offers an update on where inflation stands, how it is affecting the economy, and what steps the Federal Reserve is taking to bring it down. O'Trakoun is a senior policy economist at the Richmond Fed and primary author of the Bank's Macro Minute blog.

Decomposing the 2012-2019 inflation shortfall, and its surge starting in 2021, we find that sectoral shocks were major contributors to the inflation deviations from target.

Francisco Ruge-Murcia and Alexander L. Wolman

As the Fed works to contain inflation, many ask whether we are headed into a recession. President Barkin shares his perspective.

Perhaps history can be a guide on whether central banks should issue digital currencies.

Huberto M. Ennis , Zhu Wang and Russell Wong

When COVID-19 hit, it put consumers and businesses in unprecedented difficulty. Given the magnitude of the unique shock hitting the economy, the Fed acted to ensure that broader financial conditions did not further hurt consumers and businesses.

Among the topics covered at the Marvin Goodfriend conference were Fed bond facilities' impact on corporate credit risk and how trade leads to a global Phillips curve.

Alex Wolman and Robert King reflect on the life and legacy of Marvin Goodfriend. Throughout his career, Goodfriend wrote a number of influential papers on monetary policy and played a key role in the development of the Richmond Fed's Research Department.

Inflation hasn’t been a hot topic for decades. Now that it’s back, it’s clear consumers and businesses dislike it. Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin discusses why and how the Fed is working to contain it.

The concept of interest rate smoothing behavior by central banks is now standard, but it was not in the early 1980s when Marvin Goodfriend made the concept into a distinct phenomenon to be explained.

Michael Dotsey , Andreas Hornstein and Alexander L. Wolman

This paper builds on the analysis of Marvin Goodfriend and examines how the Fed can better engage in a rules-based monetary policy going forward.

John B. Taylor

An examination of Marvin Goodfriend and Robert G. King's "The Incredible Volcker Disinflation" paper.

Thomas J. Sargent

This essay reviews the Volcker and Greenspan policy accomplishments at the Fed, as well as Marvin Goodfriend's contributions during this timespan.

Robert L. Hetzel

Like many economists who came of age in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Marvin Goodfriend learned how models were affected by the assumption of rational expectations.

Mark W. Watson

Marvin Goodfriend drew a number of conceptual and policy implications from his analysis of inflation scares, which have become part of the central banks' approaches to monetary policy.

Athanasios Orphanides and John C. Williams

This essay discusses the ideas and contributions in Marvin Goodfriend and Robert G. King's 1988 paper and relates it to some of Goodfriend's other research on banking and monetary policy.

Douglas W. Diamond

This essay details Marvin Goodfriend's work around central bank secrecy and the evolution of transparency over the years.

Lars E.O. Svensson

This essay reviews Marvin Goodfriend's path to making the case that the U.S. should adopt an explicit inflation targeting system.

Robert G. King and Yang K. Lu

This essay explains why central banks have targeted a 2 percent target inflation rate instead of literal price stability.

Vitor Gaspar and Frank Smets

An examination of Marvin Goodfriend's research on the relationship between the zero lower bound and interest rate policy.

Ben S. Bernanke

In 1997, Marvin Goodfriend published two papers that advocated a new approach to monetary policy analysis.

Michael Woodford

This essay considers whether the 1951 Treasury-Fed Accord should be amended in order to address new challenges to Fed independence.

Charles Plosser

The development of a symbiotic relationship between academic research and central bank policymaking led to a consensus on a new framework for monetary policymaking, which remains with us today.

Mark Gertler

An analysis of the roles of central bank lending and central bank credit policy, what can go wrong with central bank lending, and how to fix these problems.

Kartik B. Athreya and Stephen D. Williamson

This essay recounts the history of interest on reserves at the Fed, showcasing the influence of Marvin Goodfriend's ideas and how those ideas were adapted as policymakers learned from the implementation of policy.

Huberto M. Ennis and John A. Weinberg

Marvin Goodfriend's views on the proper role of a central bank and his defense of the federal structure of the Federal Reserve System.

Michael D. Bordo and Edward S. Prescott

Based on different sets of reasonable assumptions, we analyze several different scenarios for the future of this critical policy-relevant lever.

Huberto M. Ennis and Kyler Kirk

President Tom Barkin explores the conditions we may face once we navigate through the current inflation storm.

President Tom Barkin discusses how the Federal Reserve is working to contain inflation and reflects on the post-pandemic era economy.

President Tom Barkin reflects on lessons learned last year and looks forward at what this year could look like for the U.S. economy.

The Fed's Overnight Reverse Repo facility has seen significant activity since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kyler Kirk and Russell Wong

For the Fed, good communication is an important tool

For policymakers and market participants, inflation can be challenging to predict.

President Tom Barkin talks about the merits of outcome-based, rather than date-based, forward guidance.

The annualized PCE inflation rate over the period March through July is 6.5 percent, the highest five-month rate since November 1981.

Not everyone experiences the same inflation. What does that mean for monetary policy?

Sometimes money gets used when it should not, and we investigate why using surveys plus measures.

Janet Hua Jiang , Peter Norman , Daniela Puzzello , Bruno Sultanum and Randall Wright

The new language — which has been in each FOMC statement since September — represents a significant shift in the committee's thinking.

With a revised strategy, the Fed responds to challenges facing central banks today

The "modern monetary theory" tenet that governments can continuously print money to fund deficits ignores the fact that governments ultimately must satisfy creditors.

Michael U. Krause , Thomas A. Lubik and Karl Rhodes

President Tom Barkin spoke about the potential for COVID-19 to leave long-lasting scars on the economy—and how policy can help.

Richmond Fed Research Director Kartik Athreya reflected on how — or if — monetary policy choices influence financial stability.

Conducting a statistical analysis of U.S. economic data, economists from the Richmond Fed and the University of Bern find no evidence of hysteresis, the idea that seemingly temporary economic shocks can have permanent effects.

Luca Benati and Thomas A. Lubik

We study new transaction-level data of discount window borrowing in the U.S. from 2010–17, merged with quarterly data on bank financial conditions (balance sheet and revenue).

Huberto M. Ennis and Elizabeth Klee

Economists at the Richmond Fed, the University of Virginia, UC Irvine, and Purdue analyze how monetary policy affects lending relationships for small businesses and vice versa.

Hailey Phelps and Russell Wong

We construct and calibrate a monetary model of corporate finance with endogenous formation of lending relationships. The equilibrium features money demands by firms that depend on their access to credit and a pecking order of financing means.

Zachary Bethune , Guillaume Rocheteau , Russell Wong and Cathy Zhang

Richmond Fed president Tom Barkin spoke about the outlook for inflation at a webinar hosted by the Money Marketeers of New York University.

The Fed is using emergency lending powers it invoked during the Great Recession to respond to COVID-19 — but it cast a wider net this time.

The Federal Reserve's purchases of agency mortgage-backed securities — launched in response to financial disruptions caused by COVID-19 — appear to have restored smooth market function supporting the continued flow of credit to mortgage borrowers.

Borys Grochulski

The market for repurchase agreements has repeatedly adapted to changing circumstances.

The process of guiding inflation expectations higher is not likely to be easy. Indeed, the historical record suggests that making up for periods of below-target inflation will be challenging.

John A. Weinberg (Emeritus)

This gallery offers a record of some of the unprecedented economic changes that Americans experienced at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jacob Crouse , David A. Price , Rachel Rodgers , Jessie Romero and Luna Shen

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, public debt has increased dramatically and private debt seems likely to increase as well.

Thomas A. Lubik and Felipe F. Schwartzman

The U.S. presidential election of 1896 provides an excellent natural experiment to measure the impact of exchange-rate uncertainty on bank balance sheets and the broader economy.

Scott Fulford , Karl Rhodes and Felipe F. Schwartzman

On Sept. 17, 2019, the repo rate spiked as high as 9 percent at one point during the trading day and ended up averaging 5.25 percent over the entire day. The size of the spike was extremely unusual.

Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin spoke November 13, 2019 at the Greensboro Chamber of Commerce’s Economic Forecast Luncheon in Greensboro, N.C.

Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin spoke November 5, 2019 at the Greater Baltimore Committee Economic Outlook conference in Baltimore, Md.

Over the last few years, the FOMC has embarked on a process of monetary policy "normalization," which includes raising interest rates above zero and reducing the size of the Fed's balance sheet.

Policymakers and commentators argue that the pursuit of attractive quarterly results often takes precedence over building long-term value. Monetary policymakers need to understand this part of the economic environment.

Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin spoke September 26, 2019 to the Richmond chapter of the Risk Management Association.

Laura Liu , Christian Matthes , Katerina Petrova and Jessie Romero

Knowing about the components of the nation's money supply and its evolving role in the economy is important for monetary policy.

Mike Finnegan

Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin spoke July 11, 2019, at the Global Interdependence Center’s Rocky Mountain Economic Summit.

National markets in many U.S. industries seem to be increasingly dominated by large companies. Some policymakers have argued that this growing market concentration is a sign of weakening competition, but concentration by itself does not necessarily translate into market power.

Tim Sablik and Nicholas Trachter

This brief makes the case that research and policy should focus on four aspects of economic fluctuations: a short-term component (cycles of less than two years), a business cycle component (cycles between two and eight years), a medium-term component (cycles up to thirty-two years), and a long-term component (the trend).

Renee Haltom , Thomas A. Lubik , Christian Matthes and Fabio Verona

Huberto M. Ennis and Tim Sablik

Modeling the U.S. economy on computers has come a long way since the 1950s. It's still a work in progress

Thomas A. Lubik , Christian Matthes and David A. Price

Laura Liu , Christian Matthes and Katerina Petrova

Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin spoke to community and business leaders in Roanoke, Virginia, about strategies to boost economic growth.

President Tom Barkin spoke at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va. on May 7, 2018.

Although very uncommon now, the Fed used to intervene regularly in foreign exchange markets

The storied showdown between Fed Chairman Bill Martin and President Lyndon Johnson wasn't just about personalities. It was a fundamental dispute over the Fed's policymaking role

Helen Fessenden

Regis Barnichon , Christian Matthes and Tim Sablik

Thomas A. Lubik , Christian Matthes and Tim Sablik

Renee Haltom and Alexander L. Wolman

As a way to understand the origins of this expectation, in this Economic Brief we look at the relationship between the federal funds rate and the average net interest margin for U.S. banks since the mid-1980s. We find that the relationship is not as clear-cut as one might suspect.

Huberto M. Ennis , Helen Fessenden and John R. Walter

Real interest rates — nominal rates adjusted for inflation — are what matter for saving, borrowing, and investing.

Andreas Hornstein , Joe Johnson and Karl Rhodes

FOMC meetings are set up to bring a wide range of perspectives to bear

Jeffrey M. Lacker

Huberto M. Ennis and David A. Price

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker addressed the Global Interdependence Center in Sarasota, Florida.

Jeffrey M. Lacker President, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey Lacker addressed the Greater Richmond Chamber of Commerce.

The Richmond Fed has a long tradition of concern for price stability

Does the hawk-dove distinction still matter in the modern Fed?

Disinflation is when inflation is falling. The Fed sometimes deliberately brings about disinflation, but there is a risk of it becoming outright deflation.

Renee Haltom Vice President and Regional Executive

Marianna Kudlyak , Thomas A. Lubik and Karl Rhodes

Economists ponder whether demographic change will reduce the potency of the Fed's interest rate moves

Stanford University economist on the effects of economic uncertainty, the role of management practices in economic performance, and fostering good management

Thomas A. Lubik and Karl Rhodes

Huberto M. Ennis

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker addressed business leaders during a luncheon hosted by the Rotary Club of Charlotte in Charlotte, N.C.

Renee Haltom and Jeffrey M. Lacker

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke on May 30, 2014 during the Hoover Institution’s Central Banking Conference at Stanford University.

Pooyan Amir-Ahmadi , Christian Matthes and Mu-Chun Wang

This paper studies equilibrium pricing in a product market for an indivisible good where buyers search for sellers.

Guido Menzio and Nicholas Trachter

Timothy Cogley , Christian Matthes and Argia M. Sbordone

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke about the economic outlook Jan. 17, 2014, in remarks to the Richmond chapter of the Risk Management Association.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke about the economic outlook in remarks to business and community leaders in Asheboro, N.C.

Nicholas Trachter , Francesco Lippi and Stefania Ragni

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker discussed U.S. monetary policy at the Swedbank Economic Outlook Seminar on Sept. 26 in Stockholm.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker discussed Federal Reserve history at Christopher Newport University on Aug. 29 in Newport News, Va.

Lacker speaks at the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce's Annual Economic Outlook Conference.

Carlos Carvalho and Felipe F. Schwartzman

Lacker Speaks at Shadow Open Market Committee Symposium in New York

Speech before the West Virginia Economic Outlook Conference Nov. 15, 2012

Lacker Addresses Business and Government Leaders in Roanoke, Va.

Speech before the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy Oct. 12, 2012

Speech before Money Marketeers Sept. 18, 2012

This Economic Brief argues that the current fiscal position is not sustainable. Though financial markets seem unconcerned, for the time being, about U.S. fiscal health, as evidenced by low rates on Treasury securities, lawmakers should not be complacent.

Renee Haltom and John A. Weinberg

Lacker Addresses Richmond Risk Management Association.

Aaron Steelman Publications Director

Lacker on Understanding the Interventionist Impulse of the Modern Central Bank ,CATO Institute Monetary Conference

Andreas Hornstein , Thomas A. Lubik and Jessie Romero

Several recent research efforts have found that stimulative fiscal policy — government spending or tax cuts — can have unusual effects when nominal interest rates are as low as they are today. In particular, some studies have found that the government spending "multiplier" can be much larger at the zero lower bound.

Renee Haltom and Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte

Lacker Addresses Dulles Regional Chamber of Commerce, Chantilly, Va.

Thomas A. Lubik and Jessie Romero

Willem Van Zandweghe and Alexander L. Wolman

Renee Haltom and Juan Carlos Hatchondo

Renee Haltom and Huberto M. Ennis

Huberto M. Ennis and Alexander L. Wolman

Thomas A. Lubik and Stephen Slivinski

John R. Walter and Renee Haltom

Robert L. Hetzel and Stephen Slivinski

Michael Dotsey and Andreas Hornstein

Yash P. Mehra and Devin Reilly

Reviews the Bank's operations and includes the article entitled "The Financial Crisis: Toward an Explanation and Policy Response"

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke March 9, 2007 at the U.S. Monetary Policy Forum 2007 in Washington, D.C.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke December 1, 2006 at The Philadelphia Fed Policy Forum in Philadelphia, Pa.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke October 30, 2006 at the Baltimore Convention Center in Baltimore, Md.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke February 14, 2006 at the West Virginia University's Acordia/Royal & SunAlliance Distinguished Lecture Series in Morgantown, Va.

Reviews the Bank's operations and includes the article entitled "Inflation and Unemployment: A Layperson's Guide to the Phillips Curve"

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke October 20, 2005 at the Winthrop University in Rock Hill, S.C.

Cover Story: Homeward Bound Housing markets work just fine for most people. But certain markets in the Fifth District aren't producing homes and apartments that working families can afford.

As usual I’ll begin with a recap of recent developments in the economy to put the outlook in perspective. Then I’ll comment on the outlook — as others see it and I see it — and finally I’ll conclude with a few remarks about monetary policy.

J. Alfred Broaddus President

Robert G. King and Alexander L. Wolman

It is a pleasure to be with you this morning. The theme of this session is “How Banks Compete.” I want to develop a variation on this theme and consider how the intensity of competition in banking has increased over the years, and some of the challenges this change presents.

It's a pleasure to be back with you once again. I don't know exactly how many years you've honored me by inviting me back, but it's an appreciable number, and I always enjoy being with you. I guess I should say most of the time.

It's a pleasure to be here today and to have this opportunity to comment on conducting monetary policy in a low inflation environment.

Yash P. Mehra

This has been a very useful conference in my view, and I am honored by this opportunity to be a part of it.1 As some of you may know, I was the second choice for this slot, but that doesn't bother me at all because the first choice was Don Brash, the Governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and a pathbreaker in bringing both transparency and accountability to central banking in practice.

Aubhik Khan , Robert G. King and Alexander L. Wolman

Marvin Goodfriend and Robert G. King

The paper explores the relationship between financial stability, deflation, and monetary policy. A discussion of narrow liquidity, broad liquidity, market liquidity, and financial distress provides the foundation for the analysis.

Marvin Goodfriend

Reviews the Bank's operations and includes the article entitled "What Assets Should the Federal Reserve Buy?"

Reviews the Bank's operations and includes the article entitled "The Role of a Regional Bank in a System of Central Banks"

Needless to say, it's a great pleasure for both Margaret and me to have this opportunity to return to IU, where we spent four very happy years between mid-1966 and mid-1970.

Reviews the Bank's operations and includes the article entitled "Monetary Policy Comes of Age: A 20th Century Odyssey"

Mr. Broaddus wishes to thank his long-time colleague, Timothy Cook, for substantial assistance in preparing the address.

Reviews the Bank's operations and includes the article entitled "Foreign Exchange Operations and the Federal Reserve"

Thank you very much for that kind introduction. It is very nice indeed to be here in the Shenandoah Valley.

- About the Levy Economics Institute

- Board of Governors

- Board of Advisors

- Staff Directory

- Employment at the Levy Institute

- Visit the Levy Institute

- Research Programs:

- The State of the US and World Economies

- Monetary Policy and Financial Structure

- The Distribution of Income and Wealth

- • Levy Institute Measure of Economic Well-Being

- • Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty

- Gender Equality and the Economy

- Employment Policy and Labor Markets

- Immigration, Ethnicity, and Social Structure

- Economic Policy for the 21st Century

- • Federal Budget Policy

- • Explorations in Theory and Empirical Analysis

- • INET–Levy Institute Project

- Equality of Educational Opportunity in the 21st Century

- Special Projects:

- Ford-Levy Institute Project

- Levy Institute M.S. in Economic Theory and Policy

- Greek Labor Institute Partnership

- Minsky Archive

- Multiplier Effect

- Levy Institute M.S. in Economic Policy and Theory

- Economics Program at Bard

- Bard Program in Economics and Finance

- Greek Labour Institute Partnership

- Economists for Peace and Security

- Economists for Full Employment

- Current Research Topics:

- Greek economic crisis

- Labor force participation

- Income inequality

- Employment policy

- Job guarantee

- Climate Change and Economic Policy

- Financial instability

- Stock-flow consistent (SFC) modeling

- Time deficits

- Fiscal austerity

- Research Project Reports

- Strategic Analysis

- Public Policy Briefs

- Policy Notes

- Working Papers

- LIMEW Reports

- e-pamphlets

- Book Series

- Conference Proceedings

- Biennial Reports

- Public Policy Brief Highlights

- In Translation Δημοσιεύσεις στα Ελληνικά

- Press Releases

- In the Media

- Request an Interview

- Sign Up for eNews

- Research Programs

Research Topics

- Request an Interview

Publications on Monetary policy

Foreign deficit and economic policy: the case of mexico, exchange-rate stability causes deterioration of the productive sphere and destabilizes developing economies, euro interest rate swap yields: some ardl models, euro interest rate swap yields: a garch analysis, unconventional monetary policy or automatic stabilizers, a financial post-keynesian comparison , monetary policy and the gender and racial employment dynamics in brazil, cbdc next-level: a new architecture for financial “super-stability” , chinese yuan interest rate swap yields, the causes of pandemic inflation, the dynamics of monthly changes in us swap yields, a keynesian perspective, seven replies to the critiques of modern money theory, still flying blind after all these years, the federal reserve’s continuing experiments with unobservables, are concerns over growing federal government debt misplaced, multifactor keynesian models of the long-term interest rate, a keynesian approach to modeling the long-term interest rate, keynes’s theories of the business cycle, evolution and contemporary relevance, some empirical models of japanese government bond yields using daily data, a stock-flow consistent quarterly model of the italian economy, the impact of technological innovations on money and financial markets, an empirical analysis of long-term brazilian interest rates, a simple model of the long-term interest rate, the empirics of canadian government securities yields, statement of senior scholar l. randall wray to the house budget committee, us house of representatives, reexamining the economic costs of debt, the impact of the bank of japan’s monetary policy on japanese government bonds’ low nominal yields, an analysis of the daily changes in us treasury security yields, when to ease off the brakes (and hopefully prevent recessions), fiscal stabilization in the united states, lessons for monetary unions, an institutional analysis of china’s reform of their monetary policy framework, two harvard economists on monetary economics, lauchlin currie and hyman minsky on financial systems and crises, unconventional monetary policies and central bank profits, seigniorage as fiscal revenue in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, twenty years of the german euro are more than enough, australian government bonds’ nominal yields, an empirical analysis, the dynamics of japanese government bonds’ nominal yields, an inquiry concerning long-term us interest rates using monthly data, the dynamics of government bond yields in the eurozone.

This paper investigates the determinants of nominal yields of government bonds in the eurozone. The pooled mean group (PMG) technique of cointegration is applied on both monthly and quarterly datasets to examine the major drivers of nominal yields of long-term government bonds in a set of 11 eurozone countries. Furthermore, autoregressive distributive lag (ARDL) methods are used to address the same question for individual countries. The results show that short-term interest rates are the most important determinants of long-term government bonds’ nominal yields, which supports Keynes’s (1930) view that short-term interest rates and other monetary policy measures have a decisive influence on long-term interest rates on government bonds.

The Long-run Determinants of Indian Government Bond Yields

This paper investigates the long-term determinants of Indian government bonds’ (IGB) nominal yields. It examines whether John Maynard Keynes’s supposition that short-term interest rates are the key driver of long-term government bond yields holds over the long-run horizon, after controlling for various key economic factors such as inflationary pressure and measures of economic activity. It also appraises whether the government finance variable—the ratio of government debt to nominal income—has an adverse effect on government bond yields over a long-run horizon. The models estimated here show that in India, short-term interest rates are the key driver of long-term government bond yields over the long run. However, the ratio of government debt and nominal income does not have any discernible adverse effect on yields over a long-run horizon. These findings will help policymakers in India (and elsewhere) to use information on the current trend in short-term interest rates, the federal fiscal balance, and other key macro variables to form their long-term outlook on IGB yields, and to understand the implications of the government’s fiscal stance on the government bond market.

Normalizing the Fed Funds Rate

The fed’s unjustified rationale.

In December 2015, the Federal Reserve Board (FRB) initiated the process of “normalization,” with the objective of gradually raising the federal funds rate back to “normal”—i.e., levels that are “neither expansionary nor contrary” and are consistent with the established 2 percent longer-run goal for the annual Personal Consumption Expenditures index and the estimated natural rate of unemployment. This paper argues that the urgency and rationale behind the rate hikes are not theoretically sound or empirically justified. Despite policymakers’ celebration of “substantial” labor market progress, we are still short some 20 million jobs. Further, there is no reason to believe that the current exceptionally low inflation rates are transitory. Quite the contrary: without significant fiscal efforts to restore the bargaining power of labor, inflation rates are expected to remain below the Federal Open Market Committee’s long-term goal for years to come. Also, there is little empirical evidence or theoretical support for the FRB’s suggestion that higher interest rates are necessary to counter “excessive” risk-taking or provide a more stable financial environment.

From Antigrowth Bias to Quantitative Easing

The ecb’s belated conversion.

This paper investigates the European Central Bank’s (ECB) monetary policies. It identifies an antigrowth bias in the bank’s monetary policy approach: the ECB is quick to hike, but slow to ease. Similarly, while other players and institutional deficiencies share responsibility for the euro’s failure, the bank has generally done “too little, too late” with regard to managing the euro crisis, preventing protracted stagnation, and containing deflation threats. The bank remains attached to the euro area’s official competitive wage–repression strategy, which is in conflict with the ECB’s price stability mandate and undermines its more recent, unconventional monetary policy initiatives designed to restore price stability. The ECB needs a “Euro Treasury” partner to overcome the euro regime’s most serious flaw: the divorce between central bank and treasury institutions.

Maximizing Price Stability in a Monetary Economy

In this paper we analyze options for the European Central Bank (ECB) to achieve its single mandate of price stability. Viable options for price stability are described, analyzed, and tabulated with regard to both short- and long-term stability and volatility. We introduce an additional tool for promoting price stability and conclude that public purpose is best served by the selection of an alternative buffer stock policy that is directly managed by the ECB.

The Empirics of Long-Term US Interest Rates

US government indebtedness and fiscal deficits increased notably following the global financial crisis. Yet long-term interest rates and US Treasury yields have remained remarkably low. Why have long-term interest rates stayed low despite the elevated government indebtedness? What are the drivers of long-term interest rates in the United States? John Maynard Keynes holds that the central bank’s actions are the main determinants of long-term interest rates. A simple model is presented where the central bank’s actions are the key drivers of long-term interest rates through short-term interest rates and various monetary policy measures. The empirical findings reveal that short-term interest rates, after controlling for other crucial variables such as the rate of inflation, the rate of economic activity, fiscal deficits, government debts, and so forth, are the most important determinants of long-term interest rates in the United States. Public finance variables, such as government fiscal balances or government indebtedness, as a share of nominal GDP appear not to have any discernable effect on long-term interest rates.

Japan’s Liquidity Trap

Japan has experienced stagnation, deflation, and low interest rates for decades. It is caught in a liquidity trap. This paper examines Japan’s liquidity trap in light of the structure and performance of the country’s economy since the onset of stagnation. It also analyzes the country’s liquidity trap in terms of the different strands in the theoretical literature. It is argued that insights from a Keynesian perspective are still quite relevant. The Keynesian perspective is useful not just for understanding Japan’s liquidity trap but also for formulating and implementing policies that can overcome the liquidity trap and foster renewed economic growth and prosperity. Paul Krugman (1998a, b) and Ben Bernanke (2000; 2002) identify low inflation and deflation risks as the cause of a liquidity trap. Hence, they advocate a credible commitment by the central bank to sustained monetary easing as the key to reigniting inflation, creating an exit from a liquidity trap through low interest rates and quantitative easing. In contrast, for John Maynard Keynes (2007 [1936]) the possibility of a liquidity trap arises from a sharp rise in investors’ liquidity preference and the fear of capital losses due to uncertainty about the direction of interest rates. His analysis calls for an integrated strategy for overcoming a liquidity trap. This strategy consists of vigorous fiscal policy and employment creation to induce a higher expected marginal efficiency of capital, while the central bank stabilizes the yield curve and reduces interest rate volatility to mitigate investors’ expectations of capital loss. In light of Japan’s experience, Keynes’s analysis and proposal for generating effective demand might well be a more appropriate remedy for the country’s liquidity trap.

Financial Regulation in the European Union

Edited by rainer kattel, jan kregel, and mario tonveronachi.

Have past and more recent regulatory changes contributed to increased financial stability in the European Union (EU), or have they improved the efficiency of individual banks and national financial systems within the EU? Edited by Rainer Kattel, Tallinn University of Technology, Director of Research Jan Kregel, and Mario Tonveronachi, University of Siena, this volume offers a comparative overview of how financial regulations have evolved in various European countries since the introduction of the single European market in 1986. The collection includes a number of country studies (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Estonia, Hungary, Slovenia) that analyze the domestic financial regulatory structure at the beginning of the period, how the EU directives have been introduced into domestic legislation, and their impact on the financial structure of the economy. Other contributions examine regulatory changes in the UK and Nordic countries, and in postcrisis America.

Published by: Routledge

Is Monetary Financing Inflationary?

A case study of the canadian economy, 1935–75.

Historically high levels of private and public debt coupled with already very low short-term interest rates appear to limit the options for stimulative monetary policy in many advanced economies today. One option that has not yet been considered is monetary financing by central banks to boost demand and/or relieve debt burdens. We find little empirical evidence to support the standard objection to such policies: that they will lead to uncontrollable inflation. Theoretical models of inflationary monetary financing rest upon inaccurate conceptions of the modern endogenous money creation process. This paper presents a counter-example in the activities of the Bank of Canada during the period 1935–75, when, working with the government, it engaged in significant direct or indirect monetary financing to support fiscal expansion, economic growth, and industrialization. An institutional case study of the period, complemented by a general-to-specific econometric analysis, finds no support for a relationship between monetary financing and inflation. The findings lend support to recent calls for explicit monetary financing to boost highly indebted economies and a more general rethink of the dominant New Macroeconomic Consensus policy framework that prohibits monetary financing.

The Euro’s Savior?

Assessing the ecb’s crisis management performance and potential for crisis resolution, modern money theory: a primer on macroeconomics for sovereign monetary systems, second edition, by l. randall wray.

In a completely revised second edition, Senior Scholar L. Randall Wray presents the key principles of Modern Money Theory, exploring macro accounting, monetary and fiscal policy, currency regimes, and exchange rates in developed and developing nations. Wray examines how misunderstandings about the nature of money caused the recent global financial meltdown, and provides fresh ideas about how leaders should approach economic policy. This updated edition also includes new chapters on tax policies and inflation.

Published by: Palgrave Macmillan

Is a Very High Public Debt a Problem?

This paper has two main objectives. The first is to propose a policy architecture that can prevent a very high public debt from resulting in a high tax burden, a government default, or inflation. The second objective is to show that government deficits do not face a financing problem. After these deficits are initially financed through the net creation of base money, the private sector necessarily realizes savings, in the form of either government bond purchases or, if a default is feared, “acquisitions” of new money.

Lending Blind

Shadow banking and federal reserve governance in the global financial crisis.

The 2008 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) transcripts provide a rare portrait of how policymakers responded to the unfolding of the world’s largest financial crisis since the Great Depression. The transcripts reveal an FOMC that lacked a satisfactory understanding of a shadow banking system that had grown to enormous proportions—an FOMC that neither comprehended the extent to which the fate of regulated member banks had become intertwined and interlinked with the shadow banking system, nor had considered in advance the implications of a serious crisis. As a consequence, the Fed had to make policy on the fly as it tried to prevent a complete collapse of the financial system.

Reforming the Fed's Policy Response in the Era of Shadow Banking

Minsky, monetary policy, and mint street, challenges for the art of monetary policymaking in emerging economies.

This paper examines the emerging challenges to the art of monetary policymaking using the case study of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in light of developments in the Indian economy during the last decade (2003–04 to 2013–14). The paper uses Hyman P. Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis as the conceptual framework for evaluating the endogenous nature of financial instability and its potential impact on monetary policymaking, and addresses the need to pursue regulatory policy as a tool that is complementary to monetary policy in light of the agenda of reforms put forward by Minsky. It further reviews the extensions to the Minskyan hypothesis in the areas of setting fiscal policy, managing cross-border capital flows, and developing financial institutional infrastructure. The lessons learned from the interplay of policy choices in these areas and their impact on monetary policymaking at the RBI are presented.

The ECB and the Single European Financial Market

A proposal to repair half of a flawed design, economic policy in india, for economic stimulus, or for austerity and volatility.

The implementation of economic reforms under new economic policies in India was associated with a paradigmatic shift in monetary and fiscal policy. While monetary policies were solely aimed at “price stability” in the neoliberal regime, fiscal policies were characterized by the objective of maintaining “sound finance” and “austerity.” Such monetarist principles and measures have also loomed over the global recession. This paper highlights the theoretical fallacies of monetarism and analyzes the consequences of such policy measures in India, particularly during the period of the global recession. Not only did such policies pose constraints on the recovery of output and employment, with adverse impacts on income distribution; but they also failed to achieve their stated goal in terms of price stability. By citing examples from southern Europe and India, this paper concludes that such monetarist policy measures have been responsible for stagnation, with a rise in price volatility and macroeconomic instability in the midst of the global recession.

A Sustainable Monetary Framework for an Independent Scotland

This September, voters in Scotland will decide whether to break away from the United Kingdom. If supporters of independence carry the day, pivotal choices that affect the scope of Scotland’s economic sovereignty and its future relationship to the UK will need to be made, particularly with respect to the question of its currency. As the disaster in the eurozone makes clear, it is essential to get these arrangements right.

In this policy brief, Philip Pilkington outlines a monetary framework designed to meet the macroeconomic challenges that would be faced by a newly separate Scotland. His conclusion: while it would be in Scotland’s best interests to continue using the sterling in the short run, making the transition to issuing its own, freely floating currency would place the country on a more stable economic footing.

Shadow Banking

Policy challenges for central banks.

Central banks responded with exceptional liquidity support during the financial crisis to prevent a systemic meltdown. They broadened their tool kit and extended liquidity support to nonbanks and key financial markets. Many want central banks to embrace this expanded role as “market maker of last resort” going forward. This would provide a liquidity backstop for systemically important markets and the shadow banking system that is deeply integrated with these markets. But how much liquidity support can central banks provide to the shadow banking system without risking their balance sheets? I discuss the expanding role of the shadow banking sector and the key drivers behind its growing importance. There are close parallels between the growth of shadow banking before the recent financial crisis and earlier financial crises, with rapid growth in near monies as a common feature. This ebb and flow of shadow-banking-type liabilities are indeed an ingrained part of our advanced financial system. We need to reflect and consider whether official sector liquidity should be mobilized to stem a future breakdown in private shadow banking markets. Central banks should be especially concerned about providing liquidity support to financial markets without any form of structural reform. It would indeed be ironic if central banks were to declare victory in the fight against too-big-to-fail institutions, just to end up bankrolling too-big-to-fail financial markets.

Modern Money Theory and Interrelations between the Treasury and the Central Bank

The case of the united states.

One of the main contributions of Modern Money Theory (MMT) has been to explain why monetarily sovereign governments have a very flexible policy space that is unconstrained by hard financial limits. Not only can they issue their own currency to pay public debt denominated in their own currency, but they can also easily bypass any self-imposed constraint on budgetary operations. Through a detailed analysis of the institutions and practices surrounding the fiscal and monetary operations of the treasury and central bank of the United States, the eurozone, and Australia, MMT has provided institutional and theoretical insights into the inner workings of economies with monetarily sovereign and nonsovereign governments. The paper shows that the previous theoretical conclusions of MMT can be illustrated by providing further evidence of the interconnectedness of the treasury and the central bank in the United States.

Wright Patman’s Proposal to Fund Government Debt at Zero Interest Rates

Lessons for the current debate on the us debt limit, options for china in a dollar standard world, a sovereign currency approach, exit keynes the friedmanite, enter minsky's keynes, the fed rates that resuscitated wall street, how the fed reanimated wall street, the low and extended lending rates that revived the big banks.

Walter Bagehot’s putative principles of lending in liquidity crises—to lend freely to solvent banks with good collateral but at penalty rates—have served as a theoretical basis for thinking about the lender of last resort for close to 100 years, while simultaneously providing justification for central bank real-world intervention. If we presume Bagehot’s principles to be both sound and adhered to by central bankers, we would expect to find the lending by the Fed during the global financial crisis in line with such policies. Taking Bagehot’s principles at face value, this paper aims to examine one of these principles—central bank lending at penalty rates—and to determine whether it did in fact conform to this standard. A comprehensive analysis of these rates has revealed that the Fed did not, in actuality, follow Bagehot’s classical doctrine. Consequently, the intervention not only generated moral hazard but also set the stage for another crisis. This working paper is part of the Ford Foundation project “A Research and Policy Dialogue Project on Improving Governance of the Government Safety Net in Financial Crisis” and continues the investigation of the Fed’s bailout of the financial system—the most comprehensive study of the raw data to date.

Lessons from an Unconventional Central Banker

The global financial crisis has generated renewed interest in the 1951 Treasury – Federal Reserve Accord and its lessons for central bank independence. A broader interpretation of the Accord and of Marriner S. Eccles’s role at the Federal Reserve should teach central bankers that independence can be crucial for fighting inflation, but also encourage them to be more supportive of government efforts to fight deflation and mass unemployment.

Marriner S. Eccles and the 1951 Treasury – Federal Reserve Accord

Lessons for central bank independence.

The 1951 Treasury – Federal Reserve Accord is an important milestone in central bank history. It led to a lasting separation between monetary policy and the Treasury’s debt-management powers, and established an independent central bank focused on price stability and macroeconomic stability. This paper revisits the history of the Accord and elaborates on the role played by Marriner Eccles in the events that led up to its signing. As chairman of the Fed Board of Governors since 1934, Eccles was also instrumental in drafting key banking legislation that enabled the Federal Reserve System to take on a more independent role after the Accord. The global financial crisis has generated renewed interest in the Accord and its lessons for central bank independence. The paper shows that Eccles’s support for the Accord—and central bank independence—was clearly linked to the strong inflationary pressures in the US economy at the time, but that he was as supportive of deficit financing in the 1930s. This broader interpretation of the Accord holds the key to a more balanced view of Eccles’s role at the Federal Reserve, where his contributions from the mid-1930s up to the Accord are seen as equally important. For this reason, the Accord should not be seen as the eternal beacon for central bank independence but rather as an enlightened vision for a more symmetric policy role for central banks, with equal weight on fighting inflation and preventing depressions.

A Meme for Money

This paper argues that the usual framing of discussions of money, monetary policy, and fiscal policy plays into the hands of conservatives.That framing is also largely consistent with the conventional view of the economy and of society more generally. To put it the way that economists usually do, money “lubricates” the market mechanism—a good thing, because the conventional view of the market itself is overwhelmingly positive. Acknowledging the work of George Lakoff, this paper takes the position that we need an alternative meme, one that provides a frame that is consistent with a progressive social view if we are to be more successful in policy debates. In most cases, the progressives adopt the conservative framing and so have no chance. The paper advances an alternative framing for money and shows how it can be used to reshape discussion. The paper shows that the Modern Money Theory approach is particularly useful as a starting point for framing that emphasizes use of the monetary system as a tool to accomplish the public purpose.

It is not so much the accuracy of the conventional view of money that we need to question, but rather the framing. We need a new meme for money, one that would emphasize the social, not the individual. It would focus on the positive role played by the state, not only in the creation and evolution of money, but also in ensuring social control over money. It would explain how money helps to promote a positive relation between citizens and the state, simultaneously promoting shared values such as liberty, democracy, and responsibility. It would explain why social control over money can promote nurturing activities over the destructive impulses of our “undertakers” (Smith’s evocative term for capitalists).

Managing Global Financial Flows at the Cost of National Autonomy

China and india.

The narrative as well as the analysis of global imbalances in the existing literature are incomplete without the part of the story that relates to the surge in capital flows experienced by the emerging economies. Such analysis disregards the implications of capital flows on their domestic economies, especially in terms of the “impossibility” of following a monetary policy that benefits domestic growth. It also fails to recognize the significance of uncertainty and changes in expectation as factors in the (precautionary) buildup of large official reserves. The consequences are many, and affect the fabric of growth and distribution in these economies. The recent experiences of China and India, with their deregulated financial sectors, bear this out.

Financial integration and free capital mobility, which are supposed to generate growth with stability (according to the “efficient markets” hypothesis), have not only failed to achieve their promises (especially in the advanced economies) but also forced the high-growth developing economies like India and China into a state of compliance, where domestic goals of stability and development are sacrificed in order to attain the globally sanctioned norm of free capital flows.

With the global financial crisis and the specter of recession haunting most advanced economies, the high-growth economies in Asia have drawn much less attention than they deserve. This oversight leaves the analysis incomplete, not only by missing an important link in the prevailing network of global trade and finance, but also by ignoring the structural changes in these developing economies—many of which are related to the pattern of financialization and turbulence in the advanced economies.

Using Minsky to Simplify Financial Regulation

Improving governance of the government safety net in financial crisis, control of finance as a prerequisite for successful monetary policy, a reinterpretation of henry simons’s “rules versus authorities in monetary policy".

Henry Simons’s 1936 article “Rules versus Authorities in Monetary Policy” is a classical reference in the literature on central bank independence and rule-based policy. A closer reading of the article reveals a more nuanced policy prescription, with significant emphasis on the need to control short-term borrowing; bank credit is seen as highly unstable, and price level controls, in Simons’s view, are not be possible without limiting banks’ ability to create money by extending loans. These elements of Simons’s theory of money form the basis for Hyman P. Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis. This should not come as a surprise, as Simons was Minsky’s teacher at the University of Chicago in the late 1930s. I review the similarities between their theories of financial instability and the relevance of their work for the current discussion of macroprudential tools and the conduct of monetary policy. According to Minsky and Simons, control of finance is a prerequisite for successful monetary policy and economic stabilization.

Shadow Banking and the Limits of Central Bank Liquidity Support

How to achieve a better balance between global and official liquidity.

Global liquidity provision is highly procyclical. The recent financial crisis has resulted in a flight to safety, with severe strains in key funding markets leading central banks to employ highly unconventional policies to avoid a systemic meltdown. Bagehot’s advice to “lend freely at high rates against good collateral” has been stretched to the limit in order to meet the liquidity needs of dysfunctional financial markets. As the eligibility criteria for central bank borrowing have been tweaked, it is legitimate to ask, How elastic should the supply of central bank currency be?

Even when the central bank has the ability to create abundant official liquidity, there should be some limits to its support for the financial sector. Traditionally, the misuse of the fiat money privilege has been limited by self-imposed rules that central bank loans must be fully backed by gold or collateralized in some other way. But since the onset of the crisis, we have seen how this constraint has been relaxed to accommodate the demand for market support. My suggestion is that there has to be some upper limit, and that we should work hard to find guidelines and policies that can limit the need for central bank liquidity support in future crises.

In this paper, I review the recent expansion of central bank liquidity support during the crisis, before discussing the collateral polices related to central banks’ lender-of-last-resort and market-maker-of-last-resort policies and their rationale. I then examine the relationship between the central bank and the treasury, and the potential threat to central bank independence if they venture into too much risky balance sheet expansion. A discussion about the exceptional growth of the shadow banking system follows. I introduce the concept of “liquidity illusion” to describe the fragility upon which much of the sector is based, and note that market growth has been based largely on a “fair-weather” view that central banks will support the market on rainy days. I argue that we need a better theoretical framework to understand the growth in the shadow banking system and the role of central banks in providing liquidity in a crisis.

Recently, the concept of “endogenous finance” has been used to explain the strong procyclical tendencies of the global financial system. I show that this concept was central to Hyman P. Minsky’s theory of financial instability, and suggest that his insights should be integrated into the ongoing search for a better theoretical framework for understanding the growth of the shadow banking system and how we can limit official liquidity support for this system. I end the paper with a summary and a discussion of some of the policy issues. I note that the Basel III “package” will hopefully reduce the need for central bank liquidity support in the future, but suggest that further structural reforms of the financial sector are needed to ease the tension between freewheeling private credit expansion and the limited ability or willingness of central banks to provide unlimited official liquidity support in a future crisis.

The European Central Bank and Why Things Are the Way They Are

A historic monetary policy pivot point and moment of (relative) clarity.

Not since the Great Depression have monetary policy matters and institutions weighed so heavily in commercial, financial, and political arenas. Apart from the eurozone crisis and global monetary policy issues, for nearly two years all else has counted for little more than noise on a relative risk basis.

In major developed economies, a hypermature secular decline in interest rates is pancaking against a hard, roughly zero lower-rate bound (i.e., barring imposition of rather extreme policies such as a tax on cash holdings, which could conceivably drive rates deeply negative). Relentlessly mounting aggregate debt loads are rendering monetary- and fiscal policy–impaired governments and segments of society insolvent and struggling to escape liquidity quicksands and stubbornly low or negative growth and employment trends.

At the center of the current crisis is the European Monetary Union (EMU)—a monetary union lacking fiscal and political integration. Such partial integration limits policy alternatives relative to either full federal integration of member-states or no integration at all. As we have witnessed since spring 2008, this operationally constrained middle ground progressively magnifies economic divergence and political and social discord across member-states.

Given the scale and scope of the eurozone crisis, policy and actions taken (or not taken) by the European Central Bank (ECB) meaningfully impact markets large and small, and ripple with force through every major monetary policy domain. History, for the moment, has rendered the ECB the world’s most important monetary policy pivot point.

Since November 2011, the ECB has taken on an arguably activist liquidity-provider role relative to private banks (and, in some important measure, indirectly to sovereigns) while maintaining its long-held post as rhetorical promoter of staunch fiscal discipline relative to sovereignty-encased “peripheral” states lacking full monetary and fiscal integration. In December 2011, the ECB made clear its intention to inject massive liquidity when faced with crises of scale in future. Already demonstratively disposed toward easing due to conditions on their respective domestic fronts, other major central banks have mobilized since the third quarter of 2011. The collective global central banking policy posture has thus become more homogenized, synchronized, and directionally clear than at any time since early 2009.

Waiting for the Next Crash

The minskyan lessons we failed to learn.

Senior Scholar L. Randall Wray lays out the numerous and critical ways in which we have failed to learn from the latest global financial crisis, and identifies the underlying trends and structural vulnerabilities that make it likely a new crisis is right around the corner. Wray also suggests some policy changes that would shore up the financial system while reinvigorating the real economy, including the clear separation of commercial and investment banking, and a universal job guarantee.

Will the Recovery Continue?

Effective demand in the recent evolution of the us economy.

We present strong empirical evidence favoring the role of effective demand in the US economy, in the spirit of Keynes and Kalecki. Our inference comes from a statistically well-specified VAR model constructed on a quarterly basis from 1980 to 2008. US output is our variable of interest, and it depends (in our specification) on (1) the wage share, (2) OECD GDP, (3) taxes on corporate income, (4) other budget revenues, (5) credit, and the (6) interest rate. The first variable was included in order to know whether the economy under study is wage led or profit led. The second represents demand from abroad. The third and fourth make up total government expenditure and our arguments regarding these are based on Kalecki’s analysis of fiscal policy. The last two variables are analyzed in the context of Keynes’s monetary economics. Our results indicate that expansionary monetary, fiscal, and income policies favor higher aggregate demand in the United States.

Was Keynes’s Monetary Policy, à Outrance in the Treatise , a Forerunnner of ZIRP and QE? Did He Change His Mind in the General Theory?

At the end of 1930, as the 1929 US stock market crash was starting to have an impact on the real economy in the form of falling commodity prices, falling output, and rising unemployment, John Maynard Keynes, in the concluding chapters of his Treatise on Money , launched a challenge to monetary authorities to take “deliberate and vigorous action” to reduce interest rates and reverse the crisis. He argues that until “extraordinary,” “unorthodox” monetary policy action “has been taken along such lines as these and has failed, need we, in the light of the argument of this treatise, admit that the banking system can not , on this occasion, control the rate of investment, and, therefore, the level of prices.”

The “unorthodox” policies that Keynes recommends are a near-perfect description of the Japanese central bank’s experiment with a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) in the 1990s and the Federal Reserve’s experiment with ZIRP, accompanied by quantitative easing (QE1 and QE2), during the recent crisis. These experiments may be considered a response to Keynes’s challenge, and to provide a clear test of his belief in the power of monetary policy to counter financial crisis. That response would appear to be an unequivocal No .

It's Time to Rein In the Fed

Scott Fullwiler and Senior Scholar L. Randall Wray review the roles of the Federal Reserve and the Treasury in the context of quantitative easing, and find that the financial crisis has highlighted the limited oversight of Congress and the limited transparency of the Fed. And since a Fed promise is ultimately a Treasury promise that carries the full faith and credit of the US government, the question is whether the Fed should be able to commit the public purse in times of national crisis.