Latin American Music Research Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Colonial composers, classical music of latin america, the 1970s, the return to the mainstream, major changes that occurred in the latin music world between 1970 and today, popularity and influence latin music internationally, influence of latin music in us society, popular latin artist, reference list.

This paper discusses some of the colonial music composers in Spanish Caribbean. The author examines Tango, Baroque and Latin Jazz as some of the old classical music in the region. Further, the writer highlights the Latin American music during the 1970s mainstream and explains changes that emerged during this period.

Consequently, the paper describes how Latin music influenced the US and the world. The final segment of the pager discusses the achievements of Shakira as a modern popular Latin American musician and describes her contributions towards growth of Latin American music Industry.

Colonial Latin composers provided a benchmark for modern Latin American music. The colonial composers’ influence has led to sprouting of various musical styles, which, in a big way, revolutionized the music world. The prosperity and growth of modern musicians has its roots in the efforts of early Latin musicians; especially the composers. Modern Latin Musicians such as Shakira, Enrique Iglesias and others, on their part, have helped to popularize Latin music styles across the world.

The colonial composers in Latin America, Spain and Portugal, were predominantly Roman Catholics. Their music compositions were tailored towards liturgical celebration. The colonial government in most Latin American countries influenced adoption of Roman rites and music.

Because of religion, popular spiritual music began emerging and impacting strongly on succeeding conventional music (King, 2004, p.275). Besides spiritual music, Portuguese and Spanish colonialists from the homeland also carried conventional music and style along to the colonies. The conventional music and style introduced complemented social, work and leisure aspects of the society.

Gaspar Fernandes is one of the most renowned composers of colonial Latin American music. He was a Portuguese and owing to his enthusiastic approach to music, the Spanish colonial masters appointed him as chapel master in Puebla, Mexico. His music propagated Christian ethics and was purposed towards the spiritual nourishment of the faithful.

Gaspar formed a choir comprising of African musicians that were former slaves. His composition and style focused on and stressed social issues such; ethnicity, race and slavery; the ills that bedeviled the colonial society. Besides, his compositions highlighted the cruelty of enslavement and how the same defined the relations that existed between African and whites in Mexico (King, 2004, p.132). One of Gaspar amiable song was “Eso rigor e repente”.

Joan Cererols is another colonial composer in Latin America. He was a Benedictine monk and he was very enthusiastic about composing Christian music (Buelow, 2004, p.414). Born at Martorell in 1618, he joined Escolania de Montserrat choir school in 1626.

Father Joan, who was fascinated by his talent and skills in understanding vocal entries and polytonal discourse, inspired his interest in music (Buelow, 2004, p.414). These skills made him a unique composer when compared to his compatriots. His ability in composition contributed to popularity of his music. Joan’s notable production included; “Missa pro defunctis” and “Missamartyrum” composed in the 17 th century (Buelow, 2004, p.160).

Latin America was musically influenced by the arrival of Spanish, Portuguese and Roman Catholic missionaries (Moore, 2010, p.74). Some of the genres introduced included; Baroque, Latin jazz and Tango (Moore, 2010, p.74). Baroque was a simple music unlike European Baroque, this was because Latin Americans did not have quality and efficient instruments for training (Moore, 2010, p.74).

Latin Jazz is a classical genre of music that started in Latin America. The composition embraced the old Cuban style, exploited Latin and African rhythms (Moore, 2010, p.88). Consequently, it incorporated harmonies of US, Caribbean, Latin and European origins. Moreover, the composition encompassed a straight rhythm, which differed from mainstream backbeat common with US jazz. The composition enshrined clave, guiro for percussion, timbale and conga (Moore, 2010, p.88). Latin jazz was embraced by small groups or in orchestras.

Lastly, Tango is also closely associated with classical music to have emerged in the region. Tango classical embraced specific instruments which included; violins, Bandon eons, piano and double bass (Moore, 2010, p.96). In addition, clarinet and guitars were common in Tango performances.

During 1970s, Latin American music reflected the music of 1920s (Roberts, 1999, p.188). In the1930s, Latin music was unified in mainstream US popular genres as a musical sub style. However, in 1970s, it emerged stronger in the US society and across the world (Roberts, 1999, p.188).

Increase in Salsa album production was also a common phenomenon in 1970s. This period recorded the highest production of Salsa albums ever created in Latin American Salsa history. For example, albums such as, “Maquino de Tiempo Time” done by Rafael Cotijo’s had a blend of Plena’s and Afro-Rican flavors (Roberts, 1999, p.188).

“Maquino de Tiempo Time” was the first Latin jazz fusion incorporated in Salsa tradition. The fusion strengthened commercial appealing across the region leading to increased production (Roberts, 1999, p.188).

Development in the1970s led to strengthening originality and creativity in Latin American music. Willie Colon for instance was a Bugalu cohort; he instilled and brought new changes in New York salsa, which was lively and innovative. This innovativeness included creative use of sound elements and artistic use of new constituents. He combined Jibaro Music of Puerto Rico, and infused Panamian, Brazilian and Colombian features (Roberts, 1999, p.192).

Creating of new bands was also a key characteristic of 1970s Latin mainstream music. Toro was one of the successful Latin American groups formed in 1972(Roberts, 1999, p.192). It emerged as a popular and influential group, although their music failed to capture Salsa roots. Sequida was also another group formed in 1970s. Sequida branched from New York Salsa. It was a successful and ambitious group, which helped in strengthening salsa during this decade (Roberts, 1999, p.192).

Dramatic changes occurred in Latin Music in 1970s. Salsa musicians became very creative. For example, Yomo incorporated Puerto Rican guitar, Larry Harlow introduced electric piano whereas Cecilia Cruz embraced Brazilian tunes (Roberts, 1999, p.193). Besides, this period increased diversification of Salsa making it transform into smooth and sweet romantic. Thus, salsa ingrained lyrics directed towards romance and love (Roberts, 1999, p.194).

Jazz fusion also underwent various changes; the style was bubbling, renewed and exiting. In addition, integration of new ingredients to Jazz music such as, “free-form improvisation” was common to style up Jazz music (Roberts, 1999, p.191). Various incorporations therefore encouraged fusion of jazz music intensifying the improvisatory aspects to 1990s.

Moreover, fusions albums were popular; although created by similar groups, style differed exponentially. Instead of embracing a codified style, some musical compositions assumed formerly outdates styles.

Rock music in Latin America was throbbing especially in Argentina in 1970s. Its composition varied i.e. the national rocks and homegrown rock such as Almendra (Roberts, 1999, p.198). At the end of 1970s, popularity of rock music was entrenched in the society. The popularity further surged when the government of the time banned English music from being aired in radios (Roberts, 1999, p.198).

The impact of Latin music in the global scene is intense and widespread. Its perplexing sounds and rhythms have gone beyond Caribbean to global. Latin music artistes use Spanish and English, which are diverse modern languages. This has transpired into its preference across cultures and thus entry into wider markets around the world.

Latin American music is has slowly but sure transformed to fuse with other different popular genres across the world. US artistes have heavily borrowed from Latin genres to establish their own compositions (Roberts, 1999, p.195).

Further, the influences of Latin American music find expression around the world through rumba, calypso and tango among other popular Latin genres (Roberts, 1999, p.197). This is because of diversity of culture and colonization. Embracing diversity and originality of style in music merged with unique cultures has contributed to its impact across the world (Roberts, 1999, p.253).

US is endowed with diverse Latin and other Spanish speaking cultures. In recognizing their culture, a lot can be learned through Latin American Music. Away from Latin and Spanish cultures, Latin musical practice and style has influenced US in more than one way. The popularity of the Latin styles is noticeable in classical music.

Although it was heard earlier during ragtime, its influence inspired US and as such, US composers such as Philip Sousa and Victor Herbert. With a distinctive US musical language, the impact of Latin American music has stood resilient. Various elements of Latin music have been incorporated in popular US music and in other types of genres across the US (Roberts, 1999, p.246).

The Cuban musical style was a major influence on US music and society. Cuban music embraces a blend and varying extent of European, African, and units of homogenization origins. The blended style of “Habanera” is popular in US. This style had its origin from Argentinean Tango.

Tango also positively affected US music and altered jazz music as well (Roberts, 1999, p.245). The universality of Salsa is the major explanation for the popularity of Latin American music in US. The influence of Salsa is evident around major cities in US; it has influenced wearing style of most US musicians and public.

Latinos presence in the US and their music has evolved in forming a diverse culture. The Latin American Music has led to the establishment of “National Academy of Arts and Sciences”; an agency that recognizes and gives awards to prominent artist “the Grammys” every year (Waxer, 2002, p.263). The agency has added Latin American Music category assortment process. The category has further been broken down into various classes in appreciation of multiplicity existing in Latin music (Waxer, 2002, p.263).

The Latin American music has also influenced emergence of female singers in the US. Gloria Estafan, a Cuban female singer collaborated with Miami Sound machine in early 1980s (Waxer, 2002, p.263). Since then, women with Spanish heritage such as Selena and Shakira have emerged and shaped the American music industry (Roberts, 1999, p.194).

Emergence of Reggaeton in the music scene is credited to Latin music. Reggaeton hip-hop is one of the leading popular styles in the US music. Reggaeton combines rap like vocals and Latin rhythms. Artistes such as pit Bull and Daddy Yankee have been synonymous with embracing this style across the US (Waxer, 2002, p.263).

Shakira is one of the most popular Latin artistes of our modern times. She was born as Isabel Mebarak Ripoll in 1972 (Krohn, 2007, p.35). Shakira is her professional or stage name. She is a songwriter, dancer and a musician. She emerged in music limelight in 1990s.

Her music life was influenced by her father, whom she used to watch writing stories using his typewriter. At the age of seven, Shakira was writing moving poems, which puzzled some of her friends. Some of her poems culminated to powerful music. Her first song was “Your dark glasses”; his father who had a taste of wearing dark glasses motivated it.

Her early exposure in public life helped her encounter Monica Ariza, a theater producer who later helped her to sharpen her music career. Monica convinced Ciro Vargas, a Sony executive to give Shakira an audition (Krohn, 2007, p.99).

The audition was granted and the talented Shakira mesmerized him and other directors. Impressive performance in the audition made the chief executive to sign Shakira to record her three albums i.e. Shakira’s Magia and Peligro album (Krohn, 2007, p.99). The albums were produced by Sony music in 1990 (Krohn, 2007, p.99).

The latter albums were officially released in 1991.The albums exemplified Shakira’s talent and influenced her exposure in Colombia. However, the album did not fetch enough money commercially. Shakira released her second album “Peligro” in 1992 and it was received with great enthusiasm than the previous “Magia” though it failed commercially because of failed popularization (Krohn, 2007, p.101).

In 1995, Shakira rose to the limelight and strengthened her attractiveness in Latin America through her album “Pies Descalzos” (Krohn, 2007, p. 103). She further recorded three tracks in Portuguese. The influence of this album and her popularity in many states encouraged her to return to Sony thus recording “Pies Descalzo” in 1995(Krohn, 2007, p.103).

Later, she successful performed “Esta Corazon?” and Pies Descalzos” which was available in Latin American markets in 1995 and globally in 1996. It was debuted as number one in more than eight countries around the world.

Shakira’s second self-produced album (produced by herself and Emilio Estan, Jr., as a co-producer) was known as “DondeEstan Los Ladrones?” This album was inspired by loss of her lyrics at the airport (Krohn, 2007, p.35). The album was a hit than “Pies Descalzos”. The success of “DondeEstan Los Ladrones” excited Shakira and she embarked on an English crossover album.

This was important for her to promote herself in a greater market while preserving the popularity of mainstream music and career diversification.”Whenever, Wherever” was the first English lead single in 2001 and 2002. The song is credited for having heavily borrowed from Andean music including Panpipes and Charango in its instrumentation. “Whenever, wherever” was internationally successful as it achieved number one slot in many countries (Krohn, 2007, p.88).

Shakira has encompassed several genres in her music productions. The most notably genres include folk, rock and mainstream pop hence her music is a synthesis of diverse features. Moreover, Shakira is one of the best and highest Latin America selling artists. She has sold over 60 million albums globally (Krohn, 2007).

“Hips don’t lie” was one of the most aired single in US radio history. Consequently, she was one of the first artists in history of commercial charts to claim a pre-eminent spot in top 40 mainstreams and Latin American Charts (Krohn, 2007).

Colonialists helped to develop the Latin American music in a big way. Latin music styles are now appreciated all over the world. By embracing elements from Africans, Europeans and Indians among other cultures, Latin musical styles such as; Salsa, Tango, Baroque, Bassa and Nova have received a lot of attention internationally. Consequently, a good music foundation traced back to the colonial period has contributed to current level of performance by modern Latin American Musicians such as Shakira and Enrique Iglesias.

Buelow, G., J. (2004). A History of Baroque Music . Indiana: Indiana University Press

King, J. (2004). The Cambridge Companion to Modern Latin American Culture . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Krohn, K. (2007). Shakira , Minnesota: Twenty-First Century Books.

Moore, R. (2010). Music in the Hispanic Caribbean. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Roberts, J. (1999). The Latin Tinge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Waxer, L. (2002). Situating Salsa: Global Markets and Local Meanings in Latin Popular Music . New York: Routledge

- Dizzy Gillespie and Louis Armstrong: Jazz Music

- Michael Jackson in Pepsi Advertising

- Gender Roles in Tango: Cultural Aspects

- The Concept of Pop Music

- Latino-American Music:Then and Now

- Analysis of Music Video

- The Story of Christian Music

- Composing and Performing Church Music

- The Classical Music and Their Effects

- Music and Vital Congregations

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 18). Latin American Music. https://ivypanda.com/essays/latin-american-music/

"Latin American Music." IvyPanda , 18 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/latin-american-music/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Latin American Music'. 18 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Latin American Music." July 18, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/latin-american-music/.

1. IvyPanda . "Latin American Music." July 18, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/latin-american-music/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Latin American Music." July 18, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/latin-american-music/.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Made in Latin America: Studies in Popular Music (2016)

Made in Latin America serves as a comprehensive introduction to the history, sociology, and musicology of contemporary Latin American popular music. Each essay, written by a leading scholar of Latin American music, covers the major figures, styles, and social contexts of popular music in Latin America and provides adequate context so readers understand why the figure or genre under discussion is of lasting significance. The book first presents a general description of the history and background of popular music, followed by essays organized into thematic sections: Theoretical Issues; Transnational Scenes; Local and National Scenes; Class, Identity, and Politics; and Gendered Scenes.

Related Papers

Juan-Pablo González

I will take the term “urban popular music” in Latin America to refer to a music that is a massmediated, a mass-culture phenomenon, and an agent of modernization. It is massmediated in the sense that the music industry and technology structure the relationships between musicians and publics, as well as those between music and musicians, who receive their art primarily by listening to recordings. It is mass-circulated because it reaches millions of people simultaneously, globalizing local sensibilities and creating trans-social and transnational alliances. It is modern because of its symbiotic relation with to the culture industry, technology, and communication, from which it develops its capacity to express the present, a fundamental historical moment for the young audience that sustains it.

En Silvia Martinez y Héctor Fouce (eds). Made in Spain. London and New York: Routledge. Pp. 187-195.

Ruben López-Cano

The relationship that Spain has with its ancient colonies in Latin America is a complex one. Unlike the relationship that the United States has with Australia and United Kingdom, for instance, Spain is not a military ally of any of the big Latin American countries. Commercial exchanges are perceived by the common citizen as an affair of the economical elites and the presence of Spanish banks and corporations are seen suspiciously as a neocolonial activity. Asymmetrical economic relations make that immigrants from Latin American countries to are mostly unqualified workers while Spaniards travelling to the Americas do so in search of exoticism or commercial advantages […] Independently of the above considerations, the fact of sharing a common language has facilitated the consumption of cultural products such as literature, music, cinema and television series on both sides without regard to their provenance. Only the characteristics of the product and the entertainment or satisfaction value they offer counts. We have a situation where a web of complex and paradoxical relationships oscillates between the recognition of a common culture and the need of asserting historical differences. It is in this unstable scenario that the diffusion, reception and consumption of Spanish urban popular music takes place. Perhaps for this reason many songs produced in Spain have not been really understood in Ibero-America. Nevertheless some of them have been cultural and vital landmarks for thousands of individuals. They have been a defining element in the mechanisms of construction of the identity and the subjectivity of successive generations in sundry social groups. They are an integral part of the private life of many individuals and of the history of Latin American music. In this article I shall examine some facets of this complex relationship. I will emphasize above all, the processes and types of transnationalism of Spanish music in Latin America in cases that go from the reproduction of stereotypes of Spanish culture to the constitution of real transnational musical scenes lacking any marks of national culture and sharing a mental imagery and worlds of signification.

Situating Popular Musics: IASPM 16th International Conference Proceedings

Martha Ulhôa

Journal of the American Musicological Society

Carolina Santamaría-Delgado

Latin American music" is such a widely used term that it would seem to be a "no-brainer": look for it in Google and you will find a ready definition. What it really means, however, presents a challenging issue for (ethno)musicologists like myself who, on a daily basis, work within the

Conference, Univ. of Southampton, UK

Carmen Bernand

The Americas may be rightly proud of two of the most important forms of modern 20th-century music: jazz and latin. « Latin » is in fact a label that was branded in the United States and encompasses different kinds of rythms and melodies (such as rumba, samba, tango). In the late 19th century creole forms of music became

Victoria Levine

Juan-Carlos Valencia

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13688790.2014.966417 Latin American popular music continues to reinvent itself, evolve, cross-ferment, seduce and spread throughout the region. Music exhibits an amazing plasticity, its range of meanings may not be infinite but it is highly diverse and dynamic. Popular genres capture the imagination and energize the bodies of people from all walks of life. Yet this plasticity is constrained by aesthetic regimes that attempt to co-opt and fix its meanings. The media, marketing and advertising industries contribute to categorizing music and associating it with very precise groups of people (target populations defined according to demographic, psychographic and behavioral criteria), using but also reinforcing existing hegemonic social understandings of music texts. This paper analyzes how particular popular music genres like Vallenato and Reggaeton are used in Colombian commercial radio stations targeted to specific social groups using criteria that reflect not only strategies of distinction but the coloniality of power.

Latin American Research Review

Oscar Manuel Sanchez Benitez

Jesús A. Ramos-Kittrell

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Routledge Companion to Music Theory Pedagogy

Gabriel Navia

Denise Kripper , Candela Marini

The Invention of Latin American Music: A Transnational History

Pablo Palomino

Jorge Saavedra Utman

Journal of the Society for American Music

Jud Wellington

Joshua Katz-Rosene

Dr. Eva Silot Bravo

Robert Garfias

Julio Mendívil

Alex E Chávez

Popular Music and Society 29(4)

Daniel Party

POPULAR MUSIC AND SOCIETY

Walescka Pino-Ojeda

Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies

Jorge Pérez

Raul R. Romero

Allan Enrique Bolivar Lobato

Mitologizacje państwa w kulturze i literaturze iberyjskiej i polskiej / Mitificación de estado en culturas y literaturas ibéricas y polacas

Alfons Gregori

Deborah Hernández

Popular Music

YEARBOOK FOR TRADITIONAL MUSIC

Fiorella Montero-Diaz

Mareia Quintero Rivera

Mona Suhrbier

Perspectivas de la comunicación

Amparo Marroquín Parducci

Latin American Music Review

Patricia Caicedo , Celeste Mann

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

International Music

- General Resources

- Japan and Korea

- Southeast Asia

- The Indian Subcontinent

- The Middle East

- North America

- Introduction

Recommended Books

Interlibrary loan.

- Australia and the Pacific

- Non-Western Instruments

- Instruments in the Education, Music and Media 3D Collection

- Popular Music This link opens in a new window

- Suggest Materials for Purchase

Reference Entries

Begin you research with these entries at Oxford Music Online.

- Afro-Cuban jazz

- Latin America

- Trinidad and Tobago

Latin America and the Caribbean

NOTE: For additional resources about classical music composed by Latin Americans, see the page Latin American Composers at the Diversity in Classical Music Research Guide.

Users are encouraged to search for items beyond University Libraries' catalog via RILM Abstracts of Music Literature and WorldCat . Materials not available in print or online may be requested through Interlibrary Loan . Please allow up to seven days for electronic delivery and up to fourteen days for delivery of physical items.

- << Previous: North America

- Next: Australia and the Pacific >>

- Last Updated: Aug 22, 2024 2:48 PM

- URL: https://bsu.libguides.com/international-music

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Cultural Nationalism and Ethnic Music in Latin America

In this Book

- William H. Beezley

- Published by: University of New Mexico Press

- View Citation

Music has been critical to national identity in Latin America, especially since the worldwide emphasis on nations and cultural identity that followed World War I. Unlike European countries with unified ethnic populations, Latin American nations claimed blended ethnicities—indigenous, Caucasian, African, and Asian—and the process of national stereotyping that began in the 1920s drew on the themes of indigenous and African cultures. Composers and performers drew on the folklore and heritage of ethnic and immigrant groups in different nations to produce what became the music representative of different countries. Mexico became the nation of mariachi bands, Argentina the land of the tango, Brazil the country of Samba, and Cuba the island of Afro-Cuban rhythms, including the rhumba. The essays collected here offer a useful introduction to the twin themes of music and national identity and melodies and ethnic identification. The contributors examine a variety of countries where powerful historical movements were shaped intentionally by music.

Music has been critical to national identity in Latin America, especially since the worldwide emphasis on nations and cultural identity that followed World War I. Unlike European countries with unified ethnic populations, Latin American nations claimed blended ethnicities—indigenous, Caucasian, African, and Asian—and the process of national stereotyping that began in the 1920s drew on themes of indigenous and African cultures. Composers and performers drew on the folklore and heritage of ethnic and immigrant groups in different nations to produce what became the music representative of different countries. Mexico became the nation of mariachi bands, Argentina the land of the tango, Brazil the country of Samba, and Cuba the island of Afro-Cuban rhythms, including the rhumba. The essays collected here offer a useful introduction to the twin themes of music and national identity and melodies and ethnic identification. The contributors examine a variety of countries where powerful historical movements were shaped intentionally by music.

- Table of Contents

- Half Title, Title, Copyright, Dedication

- pp. vii-viii

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Rise of Cultural Nationalism and Its Musical Expressions

- 1 Music and National Identity in Mexico, 1919-1940

- 2 La Hora Industrial vs. La Hora Intima: Mexican Music and Broadcast Media Before 1934

- Sonia Robles

- 3 Guatemalan National Identity and Popular Music

- 4 Cuban Music: Afro-Cubanism

- Alejo Carpentier

- 5 An Accidental Hero (Cuban Singer in the Special Period)

- Jan Fairley

- 6 Cuzcatlán (El Salvador) and Maria de Baratta’s Nahualismo

- Robin Sacolick

- 7 Cumandá: A Leitmotiv in Ecuadorian Operas? Musical Nationalism and Representation of Indigenous People

- pp. 129-148

- 8 Dueling Bandoneones: Tango and Folk Music in Argentina’s Musical Nationalism

- Carolyne Ryan Larson

- pp. 149-178

- 9 Carnival as Brazil’s “Tropical Opera” Resistance to Rio’s Samba in the Carnivals of Recife and Salvador, 1960s–1970s

- Jerry D. Metz Jr.

- pp. 179-218

- 10 The Opera Manchay Puytu: A Cautionary Tale Regarding Mestizos in Twentieth-Century Highland Bolivia

- E. Gabrielle Kuenzli

- pp. 219-226

- 11 Sounding Modern Identity in Mexican Film

- Janet Sturman and Jennifer Jenkins

- pp. 227-254

- List of Contributors

- pp. 255-258

- pp. 259-262

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

On The Site

Latin american music review.

SUBSCRIPTIONS / RENEWALS

Subscription type, ** single issues **, single issue type, special orders, single articles and discounted back issues.

Enter the journal volume and issue numbers in the available fields. See Recent Issues tab for journal details. **IMPORTANT** For single article and back issue orders, please email [email protected] to confirm availability PRIOR to payment.

- Project Muse

Journal Information

- ISSN: 0163-0350

Description

SEMIANNUAL · 6 x 9 · 128 PAGES/ISSUE · ISSN 0163-0350 · E-ISSN 1536-0199

Robin D. Moore, Editor

Latin American Music Review/Revista de Música Latinoamericana explores the historical, ethnographic, and sociocultural dimensions of Latin American music in Latin American social groups, including the Puerto Rican, Mexican, Cuban, and Portuguese populations in the United States. Articles are written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese.

Recent Issues

Volume 45, issue 1, spring/summer 2024.

Ellas también lo escuchan: El gusto por el corrido de narcotráfico entre las mujeres en Tijuana by Ana Leticia Hernández Julián

“Cacharpayita”: Un antiguo himno devocional en los oasis del desierto, Norte de Chile by Tiziana Palmiero and Alberto Díaz Araya

Archivo, mito y agenda oculta en La música en Cuba: Relectura de “Una conjura (ficcional) en la Catedral de La Habana” by Margarita Pearce

Articulación de una ideología anticomunista en el discurso musical cubano by Maylin Ortega Zulueta

Distortion and Subversion: Punk Rock Music and the Protests for Free Public Transportation in Brazil (1996–2011), by Rodrigo Lopes de Barros reviewed by Andrew Snyder

Sounding Latin Music, Hearing the Americas, by Jairo Moreno reviewed by Hannah Burgé Luviano

The Cambridge Companion to Caribbean Music, by Nanette de Jong, ed. reviewed by Peter Manuel

New York and the International Sound of Latin Music 1940–1990 , by Benjamin Lapidus Salsa Consciente: Politics, Poetics, and Latinidad in the Meta-Barrio , by Andrés Espinoza Agurto reviewed by Sarah Town

Chilean New Song and the Question of Culture in the Allende Government: Voices for a Revolution, by Natália A. Schmiedecke reviewed by Luis Achondo

Volume 44, Issue 2, Fall/Winter 2023

El computador virtuoso: Music, Technology, and the Market in Popular Unity’s Chile by Natália A. Schmiedecke and Danilo P. Avila

Canciones de comparasas de afrodescendientes del carnaval de Buenos Aires (1870–1902): Inventario y análisis de sus letras y formas musicales by Ezequiel Adamovsky

Queer Ecologies and Apocalyptic Soundings: The Caribbean Artivism of Rita Indiana by Ruthie Meadows

A Modernist Tradition: Brazilian Composer César Guerra-Peixe in the 1950s by Frederico Barros

Yengakatu, les belles chansons: Anthologie des chants wayãpi du haut Oyapock, by Jacky Maluka Pawe, Luc Taitetu Lassouka, Jérémie Wilaya Mata, and Jean-Michel Beaudet reviewed by Miguel Olmos Aguilera

Between Norteño and Tejano Conjunto: Music, Tradition and Culture at the U.S.-Mexico Border, by Luis Díaz-Santana Garza reviewed by Kim Anne Carter Muñoz

The Sweet Penance of Music: Musical Life in Colonial Santiago de Chile, by Alejandro vera reviewed by Paulo Castagna

Cinesonidos: Film Music and National Identity during Mexico’s Época de Oro , by Jacqueline Avila reviewed by Cary Peñate

De Nueva España a Méxcio: El universo musical mexicano entre centenarios , by Javier Marín-López reviewed by Kevin Parme

Volume 44, Issue 1, Spring/Summer 2023

Reimagining Latin Music New York City: The Impact of Rafael Petitón Guzmán by John Bimbiras and Paul Austerlitz

Candid Carnival: Song Videos and Social Media Intimacies in the Peruvian Andes by Violet Cavicchi Muñoz

Ensamblando las notas de un mercado sonoro: Las Primeras grabaciones comerciales en la Ciudad de México (1892-1903) by Jaddiel Diaz Frene

Singing Our Way to Freedom: A Review Essay reviewed by Peter J. García and Carlos Carrasco

Rafael Petitón Guzmán: A Dominican Musical Treasure on the World Stage, by The Dominican Studies Institute Orchestra reviewed by Darío Tejeda

Antonio Carlos Jobim, by Isabelle Leymarie reviewed by Maria Beatriz Cyrino Moreira

Tan lejos y tan cerca: El compositor interpreta su obra para guitarra , by Alex Rodríguez reviewed by Hermann Hudde

Naná Vasconcelos’s Saudades , by Daniel B. Sharp reviewed by Steven F. Butterman

Modernity and Colombian Identity in the Music of Carlos Vives y La Provincia, , by Juan Sebastián Ochoa, Carolina Santamaría-Delgado, and Carlos Eduardo Cataño reviewed by Juan Sebastián Rojas

Volume 43, Issue 2, Fall/Winter 2022

Music Entrepreneurs in Contemporary Havana: The Children of Transition by Freddy Monasterio

Tópicos musicales de escena y salón en el templo: Arrepentimiento, loor y exaltación en las canciones religiosas de Pedro Ximénez (Sucre, Bolivia, 1833–1856) by Zoila Vega Salvatierra

Apogee and Decline of Chilean Cathedral Music in the Nineteenth Century: Revisiting the Historiographical Canon by Valeska Cabrera and Mario Poblete

Lieder aus Chile/Canciones de Chile, by Violeta Parra reviewed by Steven Loza

Elite Art Worlds: Philanthropy, Latin Americanism, and Avant-Garde Music, by Eduardo Herrera reviewed by Jesse Bruer

The Music of Antonio Carlos Jobim, by Peter Freeman reviewed by Maria Beatriz Cyrino Moreira

Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz , by Christopher Washburne reviewed by Sue Miller

The Cultural Work: Maroon Performance in Paramaribo, Suriname , by Corinna Campbell reviewed by Yvonne Daniel

Capricho para pianoforte, en forma de cielito, by Juan Pedro Esnaola reviewed by Silvina Luz Mansilla

Volume 43, Issue 1, Spring/Summer 2022

Actitud decolonial, linajes y saberes otros en la música y las letras de Los Jaivas by Israel Holas Allimant y Sergio Holas

Álbumes musicales de mujeres, marcas de uso y escena cultural by Laura Jordán González y Fernanda Vera Malhue

La red Musical atlántica: Circulación de instrumentos musicales entre España y Nueva Granda (1778–1804) by Oriol Brugarolas y Lluís Bertran

Música ritual de un pueblo huave, by Roberto Campos Velázquez reviewed by Robert L. Kendrick

Bossa Mundo: Brazilian Music in Transnational Media, by K. E. Goldschmitt reviewed by Martha Tupinambá de Ulhoa

The Invention of Latin American Music: A Transnational History, by Pablo Palomino reviewed by Daniel F. Castro Pantoja

Heavy Metal Music in Argentina: In Black We Are Seen, by Emiliano Scaricaciottoli, Nelson Varas-Díaz, and Daniel Nevárez Araújo reviewed by Guillermo A. Luppi

Marasa Twa (three-album triology). Water Prayers for Bass Clarinet, by Dr. Merengue, and The Vodou Horn , by Paul Austerlitz reviewed by Rebecca D. Sager

Styling Blackness in Chile: Music and Dance in the African Diaspora, by Juan Eduardo Wolf reviewed by Laura Jordán González

Volume 42, Issue 2, Fall/Winter 2021

José Ángel Lamas (1775-1814) y el arte útil de Antiguo Régimen en Venezuela by David Coifman Michailos

Revisitando a Robert Stevenson: Entre cartas, viajes, y la musiología latinoamericana del siglo XX by Laura Fahrenkrog

Carlos Chávez in Mabel Dodge Luhan’s “Whirling around Mexico” by Christina Taylor Gibson

Cariocas de New Orleans: Brazilian Interpretations of North American Jazz by Rafael do Nascimento Cesar

Mariachi Reyna de Los Ángeles (CD), by Mariachi Reyna de Los Ángeles reviewed by Monica Fogelquist

Thinking about Music from Latin America: Issues and Questions, by Juan Pablo González reviewed by Amanda Minks

Moving Otherwise: Dance, Violence, and Memory in Buenos Aires, by Victoria Fortuna reviewed by Wanda Balbé and Camila Losada

Machine Gun Voices: Favelas and Utopia in Brazilian Gangster Funk, by Paul Sneed reviewed by Derek Pardue

Sounds of Crossing: Music, Migration, and the Aural Poetics of Huapango Arribeño, by Alex E. Chávez reviewed by Kevin Parme

Cultural Nationalism and Ethnic Music in Latin America, Edited by William H. Beezley reviewed by Viviana Parody

Volume 42, Issue 1, Spring/Summer 2021

Escribir, componer, improvisar: Prácticar creativas desde la perspectiva de jóvenes raperos de La Plata by Ana Abrina Mora

Whistling, Gender, and the Aesthetic Turn in Mexico City by Anthony W. Rasmussen

Back to the Neighborhood: Musical Contributions to the Study of Locality in latin American Cities by Christian Spencer-Espinosa

Zapateado en sones de Xantolo y sones Huastecos: Sensacíon fiscamente encarnada by Raquel Paraiso y Román Güemes Jiménez

The Latin American Songbook in the Twentieth Century: From Folklore to Militancy, by Tania da Costa Garcia reviewed by J. Ryan Bodiford

Bandas de música: Contextos interpretativos y repertorios, Edited by Nicolás Rincón Rodríguez and David Ferreiro Carballo reviewed by Ketty Wong

Sound, Image, and National Imaginary in the Construction of Latin/o American Identities, edited by Héctor Fernández L’Hoeste and Pablo Vila reviewed by Jacqueline Avila

A todas las imágenes del mundo: Antología del canto a lo divino, by Daniel González y Danilo Petorvich (investigación y recopilación) reviewed by Ignacio Ramos Rodillo

Música popular y sociedad en el Perú contemporáneo, Edited by Raúl Renato Romero reviewed by Jonathan Ritter

¿Músico pagado toca mal son? Unas miradas hacia el mercado laboral del son jarocho, by Randall Kohl reviewed by Alexandro D. Hernández

Submissions and Reviews

Latin American Music Review publishes original articles in the fields of musicology and ethnomusicology, broadly defined, applied to Latin American musical expressions. Manuscripts, notes, and bibliographies should be typed double-spaced with ample margins, free of identifying information, and submitted electronically as Microsoft Word (.doc) or Rich Text (.rtf) files at https://lamr.scholasticahq.com/ . The total length of the article, including notes and bibliography, should be approximately 8,000–12,000 words. If score examples, photographs, or other diagrams are to be included, please attach them separately as graphic files (.tif or .jpg) with as high a resolution as possible (300 dpi minimum). Along with the article, please submit two short abstracts of 75–100 words each—one in English, and the other in Spanish or Portuguese. Underneath each abstract, please designate 4–6 keywords that pertain to your article. Also submit a brief biographical sketch of the author of approximately 75–100 words, submitted as a separate word document. Articles and reviews may be submitted in English, Spanish, or Portuguese, and formatting for punctuation, quotations, and capitalization should follow the conventions for scholarship in the language of the article. Formats for notes and bibliography are those of the Chicago Manual of Style . Communications and books and CDs for review should be sent to the editor, Robin Moore, School of Music, 1 University Station E3100, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712-0435.

La Revista de Música Latinoamericana publica artículos originales en los campos de musicología y etnomusicología, ampliamente definidos, dedicados a las expresiones musicales latinoamericanas. Los manuscritos, notas y bibliografías se deben redactar a espacio doble y márgenes suficientes, sin información identificativa, como archivos de tipo Microsoft Word (.doc) o Rich Text (.rtf) que se puede mandar al https://lamr.scholasticahq.com/ . El tamaño total del artículo, incluyendo las notas y la bibliografia, debe ser aproximadamente 8,000–12,000 palabras. Si se deben incluir imágenes (partituras, fotos u otras figuras), favor de adjuntarlos como archivos gráficos (.tif o .jpg) separados, con la resolución más alta posible (mínimo de 300 dpi). Con el artículo, favor de incluir dos breves reseñas—una en español o portugués, y otra en inglés (75–100 palabras cada uno). Debajo de cada reseña, favor de incluir 4–6 palabras clave que pertenecen a su artículo. También incluya una biografía del autor de 75–100 palabras, presentado como documento separado. Las materias se pueden entregar en inglés, español o portugués, y el formato para puntuación, citas y uso de mayúscula se debe seguir las normas para publicaciones en el idioma del artículo. En cuanto al estilo de notas y bibliografía, véase el Chicago Manual of Style o utilice el estilo Harvard. Otras comunicaciones, libros y CDs enviados para reseñas se deben mandar al editor, Robin Moore, School of Music, 1 University Station E3100, University of Texas, Austin TX 78712-0435.

Editorial Correspondence and Review Copies: Robin D. Moore, Latin American Music Review, School of Music, MRH 3.204, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712-1208. (Email: [email protected] ).

BOOK, CD, & DVD REVIEW GUIDELINES

Reviews should be 800–1,200 words. Fewer than 800 words is also acceptable, and may be more appropriate for CD and DVD reviews. Given space limitations, we ask that you do not exceed 1,200 words .

BOOK REVIEWS

We recommend that you do not summarize chapter by chapter. The main goal of the review is to situate the publication vis-à-vis existing literature. Brief discussion of content is acceptable, but we stress that content needs to be evaluated in terms of its contribution to current work on Latin American music. You may wish to address the following:

- What are the author’s goals? Are they achieved?

- How does the publication contribute to the existing literature and current work on Latin American Music?

- What is the Target Audience? Who—specialists, music scholars, music instructors, graduate students, undergraduate students, performance students, the general public, etc.—would find the publication useful?

- Are the author’s arguments supported with compelling evidence?

- What is the author’s methodology?

- Brief comments on writing style; for example, is the writing clear? does the author employ technical language?

- Does the publication include musical examples/analyses?

- Does the publication include multi-media materials, such as an accompanying CD, mp3 downloads, or supporting website?

- A brief statement of the publication’s strongest and less-satisfactory aspects.

You may wish to address the following:

- Comments on the liner notes: How useful are they? Who is the author? How is the material presented? its organization, conceptualization, languages, etc.

- How does the CD contribute to exiting sources of similar genre, period, region, style, etc.

- Is the music already commercially available?

- What is the recording quality? Are these field recordings?

- What are the goals of the CD?

- How useful is the CD for pedagogical or research purposes?

- Does the CD include additional video/online resources?

DVD REVIEWS

These should be treated as book reviews: Situate the DVD in relation to existing materials on Latin American music scholarship, the goals of the DVD, the target audience, its utility for pedagogical and research purposes, etc.

- Times New Roman font and submitted as MS Word document.

- Please include bibliographic/discographic information at the beginning of the review. Place your name and affiliation at the end of the review.

- For citations, use a simple parenthetical style: “citation” (129). References should be kept to a minimum and included only when absolutely necessary. If citing an outside reference use: “citation” (Author, 2010: 213). Again, we ask that outside references be kept to a minimum.

Please send reviews to the assistant editor at : [email protected]

GUIA PARA RESENHAR LIBROS, CDS, & DVDS

Resenhas devem ser 800–1,200 palavras. Menos de 800 palavras está aceitável, e talvez mais apropriado por resenhas de CD ou DVD. Por causa de limitações de espaço, pedimos que não ultrapasse 1,200 palavras .

Resenha de livros

Recomendamos que não resume capitulo por capitulo. O objetivo principal da resenha é situar o livro vis-à-vis a literatura existente. Breve discussão do conteúdo está aceitável, mas enfatizamos que o conteúdo precisa ser avaliado pela sua contribuição ao trabalho atual sobre a música da America latina. Consideria (Talvez gostaria/desejaria?atingir/tratar-se dos seguintes aspectos/questões/pontos:

- Quais são os objetivos do/a autor/a? Foram realizados?

- Como contribuir o livro à literatura acadêmica e/ou à pesquisa atual/contemporânea da música latinoamericana?

- Quem é o público-alvo? A publicação é mais útil quem, especialistas, acadêmicos, professores/as de música, alunos graduando ou pós-graduando, estudantes de programas acadêmicos ou de performance, o público geral, etc. ?

- Os argumentos de autor/a são apoiado com provas convincentes?

- Qual é a metodologia do/a autor/a?

- Breves comentários sobre o estilo de escrever; por exemplo, o texto está nítido? O/A autor/a usa linguagem técnica?

- A publicação incluir exemplos de partituras e análises?

- A publicação incluir materiais multimídia, como CD, mp3 downloads, ou uma web site que acompanha a publicação?

- Comentários sobre os fortes e menos bons aspectos.

Resenha de CDs

Considere (Talvez gostaria/desejaria?atingir/tratar-se dos seguintes aspectos/questões/pontos:

- Comentários sobre a encarte do álbum: São úteis? Quem é o/a autor/a? Como está apresentada o material?, sua organização, conceitualização, linguagens, etc.?

- Como contribuir o CD aos fontes existentes do mesmo gênero, período, região, estilo, etc.?

- A música já estava disponível antes desse novo CD?

- Informações sobre a qualidade da gravação? São gravações do campo?

- Quais são os objetivos do CD?

- O CD está útil para fins pedagógicas ou de pesquisa?

- O CD incluir recursos adicionais, como vídeo ou online?

Resenhas de DVD , devem ser tratados como resenhas de livro: Situe o DVD em relação das materiais já existentes sobre pesquisa em música latinoamericana, os objetivos do DVD, o público-alvo, e a utilidade do DVD por fins pedagógicas e acadêmicos, etc.

- Times New Roman font e entregado como documento de MS Word

- Por gentileza incluir a informação bibliográfica/discográfica no início da resenha. Coloque o seu nome e afiliação profissional no final da resenha.

- Para citações, use um estilo parentética simplificado, ex.: “citação” (129). Referências devem ser mínimas e incluídas só se for absolutamente necessário. Caso de citar uma referência externo use: “citation” (Autor/a, 2010: 213). De novo, pedimos que referencias externas sejam mínimas.

Por favor, enviar resenhas a assistente editor: [email protected]

Peer-Review Process and Publication Ethics

Peer-Review Process

Articles submitted to the Latin American Music Review/Revista de Música Latinoamericana are initially reviewed by the editors, who determine whether the manuscript will be sent to outside reviewers. If chosen for review, the manuscript is then evaluated in a double-blind process by at least two outside reviewers, including members of the journal’s Editorial Board and/or other experts in relevant fields as selected by the editors. This peer review process is designed to ensure that the LAMR publishes only original, accurate, and timely articles that contribute new knowledge, insights or valuable perspectives to our discipline.

Reviewers play a vital role in ensuring the quality of papers published in the journal.

Questions addressed by reviewers include:

- Is the topic within the scope of the journal?

- Does the topic contribute in useful ways to existing scholarship/knowledge?

- Is the scholarship adequately documented and is relevant literature reviewed?

- Are the research aims and methodological choices made by author clear and justified?

- Is the article well organized and clearly written?

Reviewers make one of three recommendations: acceptance (that can also be accepted with revision), revise & resubmit (that implies a new submission by the author that can be reviewed by the same colleagues or two new revisors), and rejected. Reviewers are asked to include comments explaining the recommendation to provide authors with suitable feedback to improve the article. Our aim is to create a constructive process that benefits the journal and the authors while respecting the time and efforts of all volunteer reviewers.

Review Timetable

We understand that the timeliness of decisions and publication is a major concern of authors. The typical manuscript is reviewed by one of the editors and sent out to reviewers within a couple of weeks after submission. Reviewers typically have six weeks to prepare their review (a second round of reviews may be solicited if the initial reviewers disagree). Then a couple of weeks are typically required to reconcile reviewer comments (and identify any significant copyediting issues for papers that were accepted or accepted with slight revisions). Thus, it is quite possible that an author could hear back in less than two months from the time of submission. However, the realities of the peer-review process (especially our reliance on the work of international scholars) sometimes extend our timeline. You will receive a response as expeditiously as possible. If you are seeking publication for a tenure packet, please allow ample review time and let us know this is a consideration. Authors receive the reviewers’ comments and are often asked to revise the manuscript in line with the reviewers’ and/or editor’s suggestions. If the revised article is accepted for publication, the editor then determines the journal issue in which it will appear. Authors can help speed the process by ensuring they follow the submission requirements and, if accepted, addressing the reviewers comments and any copy-editing requirements in a timely fashion.

Publication Ethics The editor(s) and editorial board of the Latin American Music Review are committed to the following:

- We will make our best efforts to ensure that our peer-review processes and editorial decisions are fair and unbiased, and that manuscripts are judged solely on their merits by individuals with appropriate levels of expertise in the subject area.

- We have the right to reject a manuscript at any point in the process if, after an unbiased evaluation, it is the opinion of the editor(s) it does not contribute significantly to existing scholarship, does not align with the journal’s mission or editorial policies, or would be in conflict with the journal’s legal requirements.

- We treat submitted manuscripts as confidential documents and will not discuss them or share information about them with anyone outside the editorial staff, editorial board, potential reviewers, or the publisher.

- We expect transparency on the part of editors and reviewers regarding potential conflicts of interest and will assign manuscripts to individuals who are not expected to have such conflicts.

- submitting only original, unpublished works;

- respecting the intellectual property rights of others;

- adhering to the journal’s policies regarding simultaneous submissions;

- acknowledging sources;

- appropriately crediting all authors, other research participants, and funding sources;

- disclosing any potential conflicts of interest; and

- notifying the editors and/or publisher of any significant errors discovered after submission or publication.

- We will promptly investigate any credible allegation of unethical or illegal practices related to an article we have published. When warranted, we will issue corrections, retractions, and/or apologies, working with the author(s) as appropriate to find the best resolution.

- Concerns may be reported directly to the editor(s) or publisher by email at [email protected]

Latin American Music Review is indexed in the Academic Search Premier, Hispanic American Periodicals Index (HAPI), IBR (International Bibliography of Book Reviews), IBZ (International Bibliography of Periodical Literature), The Music Index .

Published Semiannually

Advertising Rates Full Page: $300.00 Half Page Horizontal: $250.00 Agency Commission: 15%

Mechanical Requirements Full Page: 4.5 x 7.5 in. Half Page: 4.5 x 3.75 in. Trim Size: 6 x 9 in. Halftones: 300 dpi

| Spring/Summer | March 15 | April 1 |

| Fall/Winter | September 15 | October 1 |

Acceptance Policy All advertisements are limited to material of scholarly interest to our readers. If any advertisement is inappropriate, we reserve the right to decline it.

- All copy is subject to editorial approval.

- Publisher’s liability for error will not exceed cost of space reserved.

- If requested, all artwork will be returned to advertiser.

- Invoices and tear sheets will be issued shortly after journal publication.

- We prefer to have ads as Portable Document Format (PDF) files.

These files can be e-mailed directly to [email protected] .

Stay connected for our latest books and special offers.

We live in an information-rich world. As a publisher of international scope, the University of Texas Press serves the University of Texas at Austin community, the people of Texas, and knowledge seekers around the globe by identifying the most valuable and relevant information and publishing it in books, journals, and digital media that educate students; advance scholarship in the humanities and social sciences; and deepen humanity’s understanding of history, current events, contemporary culture, and the natural environment.

Music and Resistance in Colonial Latin America

This season, we have been exploring the theme of music as resistance : the ways in which music has given voice to those who have been chronically underrepresented. Our explorations have included a panel discussion which unpacked how music can push back again persecution, oppression, and injustice; a recent article from Laury Gutiérrez on Antonia Bembo , the remarkable Italian baroque composer who created her own musical language during her self-imposed exile in France; and the remarkable history of Holocaust music and Francesco Lotoro , the man on a mission to catalog it.

In this final article in our Music as Resistance series, musicologist Daniel Zuluaga presents a bird’s eye view of music of the Americas during the colonial period. His essay raises questions and considers the obstacles that emerge when considering the opposing forces of resistance and assimilation.

By Daniel Zuluaga

For most of the Spanish colonial period in the Americas, musical performance was a core element in the interaction between the continent’s Indigenous populations, imported slave force, and colonizers. Spanish musical traditions were a powerful evangelical tool for the early missionaries. They also represented a link to the homeland for some, a pathway to a new profession for others, and a marker of differentiation through culture, education, and religion, for most of the distinct groups that comprised colonial society.

In addressing the idea of music and resistance in the Americas during the colonial period, there are three major obstacles that concern chronology, geography, and documentation. Let’s start with the chronology. A good number of the urban settlements that became important cultural centres in the colonies, such as Bogotá, Lima, or Puebla, were established as early as the 1530s. On the opposite end, the Spanish colonial period comes to an end, albeit incomplete, in the early 1820s.

These boundaries represent a time frame of nearly 300 years and encompass three well-defined major eras in European music — the Renaissance, Baroque and Classical periods. And yet musical production in the Americas is often misaligned, stylistically speaking, with these eras. It also lags with regard to vanguard trends in Europe, so that in the 1620s, for instance, composers are still writing abundant material that echoes Spanish cancioneros from the mid-to-late sixteenth century rather than, say, monody or early opera.

Partly to make the chronology manageable, researchers have tended to focus on early Spanish-Indigenous musical interactions. More recent studies have examined the later history of such interactions and the assimilation at the urban and rural levels of Spanish musical traditions, uncovering self-sufficient communities, musically speaking, developing separately from Spanish jurisdiction.

A second obstacle is geography. The region extends from Patagonia in the south to most of what is today the United States. This vast colonial society was underpinned by several key administrative institutions: two sixteenth-century viceroyalties, that of Nueva España , comprising Central and North America, and that of Perú , covering most of South America, expanded in the eighteenth century to include new districts for Nueva Granada (Colombia, Ecuador, Panamá and Venezuela) and Río de la Plata (Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay). Further subdivision into political or religious jurisdictions underscores the Spanish intent to use cities as centres of cultural and economic development and to resettle Indigenous populations into reducciones .

The heterogeneous nature and massive scale of the territory impacted musical culture, whereby the urban entities that are better known to us today are only a partial image of music-making in the continent. Their complement is the largely unscrutinised rural musical culture. Interestingly, it is this heterogeneity which provided the most fertile soil for the active incorporation and successful assimilation of Spanish musical practice into the native communities.

The third obstacle is documentation. One of the main issues in the study of colonial music is the lack of clarity in the geography of music-making in the region. Our current knowledge favours the urban culture over the rural, although that is slowly changing. This is a consequence of better record availability at urban centres, often also linked to the role of the Catholic Church as a main patron of the arts.

Where documentation of another nature survives, there is a sense that music-making was pervasive. For instance, documentation of import duties between 1512 and 1516, charged by customs offices in Puerto Rico to all merchandise brought into the continent, show the regular import of guitars, vihuelas, and instrument strings, pointing to commonplace music-making since the earliest days of the Spanish presence.

In this context, the idea of resistance in the form of music suggests several questions, none of which is easily answered. How do we engage with the profoundly traumatic aspects of the continent’s history under the Spanish empire? How to interpret the contradictions present in the musical repertoire, where a song text depicting the sorrows of slavery is set to music that invites dancing and singing? What was the perception (and reception) that the different groups, Indigenous, Black, and Spanish, had towards each other’s music?

Currently there are no definitive answers to such questions, but they still allow us to posit some ideas that can help further the conversation. Thanks to the research of musicologists such as Geoff Baker, a key figure in colonial music, we know that the Spaniards’ early view of Indigenous music was tolerant and, if anything, apt to be changed and used for the religious conversion of local populations.

Against the tolerant views stood a cohort that saw Indigenous music and dance as a tool for perpetuating their religious practices, either covertly or out in the open, and sought to ban it. While in theory we get the sense that for every voice that was tolerant, there was another vehemently against it, in practice the result varied by both chronology and geography, with some areas and periods more prone to try to move local populations away from their musical traditions by force, often by repressive churchmen.

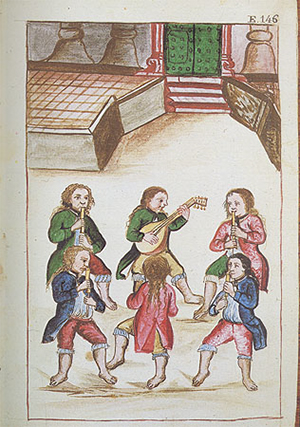

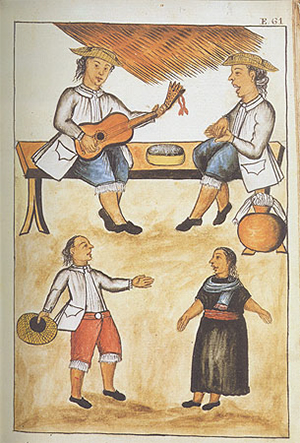

At the other end of the spectrum, we find the music such as that copied by the Spanish bishop Baltasar Martínez Compañón, who in the 1780s, travelled through his archdiocese in Truxillo, in Northern Perú, recording the lives, traditions and music of its inhabitants in nine volumes of watercolours. The few scores he copied succinctly show an amalgam of native and European traditions that undoubtedly reflects living musical practice.

As to the contradictions, the answer probably lies in developing our awareness as listeners: that many of the surviving songs that seemingly portray rural or local music making more likely reflect musical practice rooted in Spanish institutions and the corresponding performance practice, as appropriated and adapted by local populations. It serves us well to remember that written music presumes at least a medium level of musical literacy, which was more common in the proximity of urban centres.

To the point raised in the first question, we should remember that cultural interaction in the Colonial Americas was not one between equal parties. The Spanish conquest and colonization of the continent, like most endeavours of the sort, was an extremely violent, exploitative process. The main purpose of the colonizers was never other than the economic exploitation of the newly conquered territories and the evangelization of Indigenous populations. Paraphrasing Geoff Baker once again, it is key to keep in mind that when one speaks of colonizers, one also speaks of the colonized, which can be seen as a euphemism for enslavement, oppression, and suffering.

In the popular imagination we still have the tendency to think about music in colonial Latin America as exotic. The evidence points elsewhere: to numerous divergent practices that have strong roots in imported Spanish musical practices. Thus, a clear definition of resistance, at least in this context, remains unattainable.

However, if I were to point to one element that illustrates the idea of music as resistance in the colonial Americas, I would ask the reader to look more closely at the humble guitar. In a sense, this instrument is an embodiment of many of the ideas in this essay, one that has bridged the aforementioned obstacles of chronology, geography, and (lack of) documentation. Its ubiquity in musical practice throughout the entire continent, in urban and rural settings, both then and now, speaks of adaptation, appropriation, and assimilation in a manner that reinforced the development of the distinctive musical practices of the Indigenous, Black, criollo, and Spanish populations in colonial Latin America—populations who took this instrument and made it their own.

Daniel Zuluaga has made the history and performance practice of early plucked instruments the central tenet of his career as a professional performer and researcher on the baroque guitar, lute, and theorbo. A JUNO Award winner (2016) and a Grammy Award nominee (2018), he is a specialist in Latin American Baroque music. His programming and leadership in the interpretation of this repertoire has earned him numerous critical accolades. He collaborates regularly with leading orchestras in the US and Canada as performer and director, including Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Les Violons du Roy, L’Harmonie des Saisons and Portland Baroque Orchestra. An avid researcher, Mr. Zuluaga holds a PhD in musicology from the University of Southern California and has been recipient of grants and awards from the Fulbright Commission, the American Musicological Society and the Canada Council for the Arts.

Daniel Zuluaga’s recommended recordings for further listening:

- Fiesta Criolla Ensemble Elyma, Gabriel Garrido (K617) on Naxos Music Library and YouTube

- Las Ciudades de oro L’Harmonie des saisons (ATMA Classique) on Spotify and YouTube

- Juan Gutierrez de Padilla Ars longa de la Habana, Teresa Paz (Almaviva) on Spotify and YouTube

- Padilla: Sun of Justice Los Angeles Chamber Singers’ Cappella, Peter Rutenberg, dir. on Spotify

- Codex Martínez Compañón Capilla de Indias, Tiziana Palmeira (K617) on Spotify and YouTube

All images are from the Codex Trujillo, or Codex Martinez Compañon .

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Music in Colonial Latin America

Introduction.

- Puerto Rico

- Dictionaries

- Encyclopedias

- Handbooks and Bibliographies

- Textbooks and Companions

- Other Databases

- Music Theory Treatises

- Scholarship on Music Theory

- Music Education

- Transatlantic Exchanges

- Social and Cultural Studies

- Secular and Vernacular Music

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Andean Music

- Brazilian Popular Music, Performance, and Culture

- The Musical Tradition in Latin America

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Afro-Andeans

- Economies in the Era of Nationalism and Revolution

- Violence and Memory in Modern Latin America

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Music in Colonial Latin America by Jesús A. Ramos-Kittrell LAST REVIEWED: 23 June 2023 LAST MODIFIED: 23 June 2023 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199766581-0281

While European influences were important in musical culture of the colonial period, the movement of practices from among the different ethnic groups makes music in colonial Latin America a robust landscape of investigation. European music was surely a means to negotiate racial tensions. However, recorded evidence also shows that non-European elements participated in this exchange. Additionally, there are recorded accounts of “folk” or “popular” musical expressions happening in society. And while the wealth of notated European music sources made religious repertories the immediate point of focus in early scholarship, the flux of musical practices in the public sphere suggests that “European assimilation” or “imposition” might be unfitting one-way labels to understand the complex exchanges that shaped the colonial musical experience. For this reason, more recent studies have begun to incorporate approaches from cultural studies and social history to address this frame of activity. The following list pays attention to music from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries (although some sources spill into the nineteenth century). The bibliography begins with sources giving a general overview of music history in Latin America. This section, General Overviews , offers information on firsthand secondary source material for the study of colonial music, followed by general studies focused on specific countries. The next section points to useful Reference Works (the information contained in this segment does not attempt to be exhaustive; rather, it is meant to guide the reader to sources where more detailed information and further bibliographic materials may be found). After that, the bibliography organizes sources in five sections: Ecclesiastical Music Studies , Music Theory and Education , Transatlantic Exchanges , Social and Cultural Studies , and Secular and Vernacular Music .

General Overviews

Due to an early interest in European music by American scholars, some of the first publications on colonial Latin American music feature inventories or compilations of surviving music sources ( Spiess and Stanford 1969 , Stevenson 1970 , and Stevenson 1974 ), although some of these publications do offer general historical information to situate the sources found. Other early sources provide the first historical studies of music in Latin America, and these bring attention to the colonial period ( Slonimsky 1945 —the reader may use caution in reading into the cultural biases in this source). The importance of cities (main hubs for the experience of modernity) was also the focus of other early studies ( Stevenson 1952 , Stevenson 1968 ). In these studies, Tenochtitlan and Peru were considered the pinnacles of pre-Hispanic civilization. Studies in Spanish also emerged and attempted to redress Euro-American readings of Latin American music history ( Béhague 1979 ). Out of an interest to cope with the rhetoric of progress, these Latin American music studies emerged to map a history of Latin American culture when this very idea was being debated in and outside of the United States. More recently, scholars have begun to focus on a more comprehensive view of music history in light of the richness and difference in cultural perspective that has permeated colonial music studies ( Waisman 2019 , Gómez, et al. 2009–2016 , and Vera 2020 —see the introduction).

Aretz, Isabel. América Latina en su música . Paris: UNESCO, 1977.

A view by Latin American scholars of musical development in Latin America since the conquest. Chapters written by different authors. Three chapters devoted to the colonial period. The source is somewhat influenced by primitivist views informing ideas of national culture.

Béhague, Gerard. Music in Latin America: An Introduction . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1979.

A general history of music in Latin America with attention to Western art music produced in Latin America. Considered to be the first comprehensive and thoroughly documented historical book on the subject.

Gómez, Maricarmen, Álvaro Torrente, and José Máximo Leza, eds. Historia de la música en España e Hispanoamérica . Vols. 2–4. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2009–2016.

A multivolume collection featuring historical analyses carried out by different researchers. The collection offers a rich panorama of historical context, practices, repertoire, and personalities.

Hague, Eleanor. Latin American Music: Past and Present . Santa Ana, CA: Fine Arts Press, 1934.

This is brief and generalizing view of the so-called civilizing process of cultural encounter, with attention of the idea of cultural fusion.

Mendoza de Arce, Daniel. Music in Ibero-America to 1850: A Historical Survey . Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2001.

A survey study of music in Ibero-America at large, with a focus on institutions, in twelve chapters. Seven chapters devoted to the colonial period.

Slonimsky, Nicolas. Music of Latin America . New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1945.

A European-based view of history, composers, and characteristics of music from twenty Latin American countries.

Spiess, Lincoln B., and E. Thomas Stanford. An Introduction to Certain Musical Archives . Detroit: Information Coordinators, 1969.

A preliminary inventoried list of musical holdings at the cathedrals of Mexico City and Puebla. Due to the limited access given to the authors by cathedral authorities, and to the constraints of working space, the list is rather short and not representative of the actual musical sources found in these churches. This was, nonetheless, one of the first efforts to account for musical holdings in ecclesiastical institutions.

Stevenson, Robert. Music in Aztec and Inca Territory . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968.

A survey study of music in these two territories, including pre-Hispanic music, the study of musical cultures (European and Indigenous) at the time of encounter, and the development of musical practices.

Stevenson, Robert. Renaissance and Baroque Musical Sources in the Americas . Washington, DC: General Secretariat, Organization of American States, 1970.

List of music sources in different Latin American repositories, which as of 1970 had not been accounted for in previous catalogues. Repositories include the cathedrals of Bogotá, Cuzco, Guatemala City, Oaxaca, Puebla, and Sucre; National Libraries in Lima, Mexico City, and other archives in archbishoprics, former colleges, and museums.

Stevenson, Robert. Christmas Music from Baroque Mexico . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

DOI: 10.1525/9780520317932

A partial study of Christmas music sources, some acquired by Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, others seemingly in private hands at that point. As with his volume from 1970, Stevenson’s effort was to unearth repertory. Bibliographic information to locate some of this material is not forthcoming in the book.

Waisman, Leonardo. Una historia de la música colonial hispanoamericana . Buenos Aires: Gourmet Musical Ediciones, 2019.

Monograph focused solely on the history of colonial music in Latin America. The book gives due attention to music in Jesuitic missions and grapples with the different academic paradigms that have permeated research in colonial music studies.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Latin American Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abortion and Infanticide

- African-Descent Women in Colonial Latin America

- Agricultural Technologies

- Alcohol Use

- Ancient Andean Textiles

- Andean Contributions to Rethinking the State and the Natio...

- Andean Social Movements (Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru)

- Anti-Asian Racism

- Antislavery Narratives

- Arab Diaspora in Brazil, The

- Arab Diaspora in Latin America, The

- Argentina in the Era of Mass Immigration

- Argentina, Slavery in

- Argentine Literature

- Army of Chile in the 19th Century

- Asian Art and Its Impact in the Americas, 1565–1840

- Asian-Peruvian Literature

- Atlantic Creoles

- Baroque and Neo-baroque Literary Tradition

- Beauty in Latin America

- Bello, Andrés

- Black Experience in Colonial Latin America, The

- Black Experience in Modern Latin America, The

- Bolaño, Roberto

- Borderlands in Latin America, Conquest of

- Borges, Jorge Luis

- Bourbon Reforms, The

- Brazilian Northeast, History of the

- Buenos Aires

- California Missions, The

- Caribbean Philosophical Association, The

- Caribbean, The Archaeology of the

- Cartagena de Indias

- Caste War of Yucatán, The

- Caudillos, 19th Century

- Cádiz Constitution and Liberalism, The

- Central America, The Archaeology of

- Children, History of