- < Previous

Home > Schools & Departments > HE > SOSE > Health Sciences Program > Faculty Publications > 38

Health Sciences Faculty Publications

Stressors and coping strategies in the new normal: a case study of teachers in a higher education setting.

Janine Marie Balajadia , Ateneo de Manila University Maria Micole Veatrizze Dy , Ateneo de Manila University Lukas Pariñas , Ateneo de Manila University Christine Leila Taguba , Ateneo de Manila University Alessandra Grace Tan , Ateneo de Manila University Maxine Therese Tuazon , Ateneo de Manila University Jerome Patrick Uy , Ateneo de Manila University Genejane M. Adarlo , Ateneo de Manila University Follow

Document Type

Conference Proceeding

Publication Date

When governments restricted holding in-person classes to contain the spread of COVID-19, many higher education institutions turned to digital technology to continue the education of their students. This abrupt change in the delivery of teaching and learning posed pedagogical and technological challenges to the teachers. And as governments have gradually allowed the return of students to physical classrooms with the decline in COVID-19 cases and the rollout of vaccines, teachers must adapt once more to a different arrangement for teaching and learning. Using the Job Demands-Resources Model as a theoretical framework, this case study examined the stressors (i.e., job demands) encountered by teachers in a higher education setting as students have returned to physical campuses. It also explored their coping strategies (i.e., job resources) that helped them adjust to the demands of using a different arrangement for teaching and learning in the new normal. Thematic analysis of responses to open-ended questions in a survey of 100 teachers in an institution of Catholic higher education in the Philippines showed demands related to teaching as a job and other competing concerns were brought up as stressors when in-person classes resumed after two years of fully online teaching. It also revealed seeking social support, focusing on teaching and research, and practicing self-care as their ways of coping with the demands of the new normal. Findings from this study can contribute to policies that can cater to faculty development.

Recommended Citation

Balajadia, J. M., Dy, M. M. V., Pariñas, L., Taguba, C. L., Tan, A. G., Tuazon, M. T., Uy, J. P., Adarlo, G. (2023). Stressors and Coping Strategies in the New Normal: A Case Study of Teachers in a Higher Education Setting. In N. Callaos, J. Horne, B. Sánchez, M. Savoie (Eds.), Proceedings of the 17th International Multi-Conference on Society, Cybernetics and Informatics: IMSCI 2023, pp. 92-98. International Institute of Informatics and Cybernetics. https://doi.org/10.54808/IMSCI2023.01.92

Since February 28, 2024

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Libraries & Archives

- Ateneo Journals

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- Why contribute?

- Getting started

- Working with publishers and Open Access

- Copyright and intellectual property

- Contibutor FAQ

About Archium

- License agreement

- University website

- University libraries

Home About Help My Account Accessibility Statement

Privacy & Data Protection Copyright

What Students Are Teaching the Rest of Us about the New Normal

With the COVID-19 pandemic taking a toll on students, personally and academically, many of them are modeling how to respond to the new normal.

So many of us in higher education, and across the world, are exhausted, frustrated, and anxious. Two years ago, everything started to shut down—initially for only two weeks, maybe three—so that we could "bend the curve" to get the COVID-19 pandemic under control and return to normal life.

In those first weeks, which became months, we learned that technology could enable virtual learning in many remarkable ways. But even with all this technology, students still struggled to make real connections with their professors and with each other. And everywhere, all the time, was the risk that the coronavirus was out there, ready to get you if you were not careful or if you were just unlucky. Now, even with vaccines, COVID-19 surges continue as we enter year three.

On another level, however, something interesting is happening in higher education. With the COVID-19 pandemic also taking a toll on students, personally and academically, many of them are modeling, for the rest of us, how to respond to the new normal. In the last week of my class in December 2021, I asked 110 undergraduates:

"How would you say the COVID-19 pandemic has changed you as a student and as a person?"

Mixed Responses

Students stated a variety of ways in which they had matured during the pandemic. Many offered some version of "I've learned how to manage stress and independence." They reported becoming much better at learning independently and developing important life skills. They noted that they are now more aware of the impact of their actions on other people and that they have new appreciation for friends, family, school, and being in nature.

Other students were much less positive. Academically, they reported: "Online learning is really hard—and I am not good at it." They're delighted to be on campus and in person, but they also had to adjust to going back to the classroom. Some students replied more personally: "I'm anxious and sad." "I'm pessimistic and cynical." "I'm burned out." "I'm stressed out." "I have new and worse mental health issues."

Still other students offered a mixed response. Several said something like: "I am a better person but a worse student." Although they considered themselves to be sophisticated social media users, they know that they spend too much time with it. One insightful student reflected that the impact of the pandemic on students was "huge and may not be fully understood for years."

How are students managing all this? Overall, students are coping with their exhaustion, frustration, and anxiety in some healthy ways: through self-care, openness, and empathy.

Students are making a deliberate choice for self-care. For many students, "self-care" may have been considered an indulgent luxury before the pandemic. They heard people telling them: "You should be in school full-time and doing an internship and working at a job and conducting research and volunteering and and and. . . . If you are resting, if you are not interested, don't worry, there is always someone else, ready to work harder, work faster, get ahead. They will win and you will lose—so you better keep going."

But students seem to have made a conscious decision that go-go-go is no longer the only route. Students are saying "no" to things—things that are not essential or not rewarding, things that might advance their careers but not their lives. Students are focusing on healthier relationships, nutrition and exercise, and positive attitudes. Some of my students, for example, began taking—or teaching—Zoom yoga classes. Others incorporated long walks in green spaces into their busy schedules.

Flowing from self-care, students are now being more open with their instructors. They'll say: "I didn't have time to do the assignment"—offering no excuses or apologies (or drama) and willing to accept any consequences. They speak candidly about their own health. "I didn't come to class with my cough. I didn't want to put anyone at risk." Or: "I got tested. It's strep, not Covid." In response, instructors don't need doctors' notes: we are more trusting, with bonds forged from our common threats and from our students' trust in us.

Students are increasingly open about their mental health as well. Sometimes this goes back to self-care: "I just needed a day off." Other times students offer unapologetic candor about specific mental health diagnoses—information that instructors don't need and that students might once have thought carried real stigma. "I am being treated for anxiety"—or depression or ADHD or bipolar disorder. "I'm a recovering alcoholic and drug addict." "My therapist said . . ."

Students are also more open about other parts of their lives: "My dad lost his job." "I came out to my Mom." "My boyfriend dumped me," "I'm failing chemistry." Expecting no judgment or special treatment, they simply think it's now normal to share.

Finally, students are responding to the new normal with empathy. Instead of scrutinizing the decisions of others—especially on social media—they accept each other's decisions more generously and with support. Students know that there is a lot they don't know about each other: lives, backgrounds, struggles. Students may not understand Alex's priorities or Sasha's choices, and that's okay. Let Alex be Alex and let Sasha be Sasha.

We can't know whether these lessons will last beyond the pandemic. The next cadre of college and university students—struggling today through their own middle and high school journeys—will have been through pandemic-era online learning at a much younger age. But for now, all of us working in higher education can learn from how students are responding to the new normal with self-care, openness, and empathy.

Jim Quirk teaches in the School of Public Affairs at American University in Washington, DC.

© 2022 Jim Quirk. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 15 February 2018

Blended learning: the new normal and emerging technologies

- Charles Dziuban 1 ,

- Charles R. Graham 2 ,

- Patsy D. Moskal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6376-839X 1 ,

- Anders Norberg 3 &

- Nicole Sicilia 1

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education volume 15 , Article number: 3 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

557k Accesses

389 Citations

117 Altmetric

Metrics details

This study addressed several outcomes, implications, and possible future directions for blended learning (BL) in higher education in a world where information communication technologies (ICTs) increasingly communicate with each other. In considering effectiveness, the authors contend that BL coalesces around access, success, and students’ perception of their learning environments. Success and withdrawal rates for face-to-face and online courses are compared to those for BL as they interact with minority status. Investigation of student perception about course excellence revealed the existence of robust if-then decision rules for determining how students evaluate their educational experiences. Those rules were independent of course modality, perceived content relevance, and expected grade. The authors conclude that although blended learning preceded modern instructional technologies, its evolution will be inextricably bound to contemporary information communication technologies that are approximating some aspects of human thought processes.

Introduction

Blended learning and research issues.

Blended learning (BL), or the integration of face-to-face and online instruction (Graham 2013 ), is widely adopted across higher education with some scholars referring to it as the “new traditional model” (Ross and Gage 2006 , p. 167) or the “new normal” in course delivery (Norberg et al. 2011 , p. 207). However, tracking the accurate extent of its growth has been challenging because of definitional ambiguity (Oliver and Trigwell 2005 ), combined with institutions’ inability to track an innovative practice, that in many instances has emerged organically. One early nationwide study sponsored by the Sloan Consortium (now the Online Learning Consortium) found that 65.2% of participating institutions of higher education (IHEs) offered blended (also termed hybrid ) courses (Allen and Seaman 2003 ). A 2008 study, commissioned by the U.S. Department of Education to explore distance education in the U.S., defined BL as “a combination of online and in-class instruction with reduced in-class seat time for students ” (Lewis and Parsad 2008 , p. 1, emphasis added). Using this definition, the study found that 35% of higher education institutions offered blended courses, and that 12% of the 12.2 million documented distance education enrollments were in blended courses.

The 2017 New Media Consortium Horizon Report found that blended learning designs were one of the short term forces driving technology adoption in higher education in the next 1–2 years (Adams Becker et al. 2017 ). Also, blended learning is one of the key issues in teaching and learning in the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative’s 2017 annual survey of higher education (EDUCAUSE 2017 ). As institutions begin to examine BL instruction, there is a growing research interest in exploring the implications for both faculty and students. This modality is creating a community of practice built on a singular and pervasive research question, “How is blended learning impacting the teaching and learning environment?” That question continues to gain traction as investigators study the complexities of how BL interacts with cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of student behavior, and examine its transformation potential for the academy. Those issues are so compelling that several volumes have been dedicated to assembling the research on how blended learning can be better understood (Dziuban et al. 2016 ; Picciano et al. 2014 ; Picciano and Dziuban 2007 ; Bonk and Graham 2007 ; Kitchenham 2011 ; Jean-François 2013 ; Garrison and Vaughan 2013 ) and at least one organization, the Online Learning Consortium, sponsored an annual conference solely dedicated to blended learning at all levels of education and training (2004–2015). These initiatives address blended learning in a wide variety of situations. For instance, the contexts range over K-12 education, industrial and military training, conceptual frameworks, transformational potential, authentic assessment, and new research models. Further, many of these resources address students’ access, success, withdrawal, and perception of the degree to which blended learning provides an effective learning environment.

Currently the United States faces a widening educational gap between our underserved student population and those communities with greater financial and technological resources (Williams 2016 ). Equal access to education is a critical need, one that is particularly important for those in our underserved communities. Can blended learning help increase access thereby alleviating some of the issues faced by our lower income students while resulting in improved educational equality? Although most indicators suggest “yes” (Dziuban et al. 2004 ), it seems that, at the moment, the answer is still “to be determined.” Quality education presents a challenge, evidenced by many definitions of what constitutes its fundamental components (Pirsig 1974 ; Arum et al. 2016 ). Although progress has been made by initiatives, such as, Quality Matters ( 2016 ), the OLC OSCQR Course Design Review Scorecard developed by Open SUNY (Open SUNY n.d. ), the Quality Scorecard for Blended Learning Programs (Online Learning Consortium n.d. ), and SERVQUAL (Alhabeeb 2015 ), the issue is by no means resolved. Generally, we still make quality education a perceptual phenomenon where we ascribe that attribute to a course, educational program, or idea, but struggle with precisely why we reached that decision. Searle ( 2015 ), summarizes the problem concisely arguing that quality does not exist independently, but is entirely observer dependent. Pirsig ( 1974 ) in his iconic volume on the nature of quality frames the context this way,

“There is such thing as Quality, but that as soon as you try to define it, something goes haywire. You can’t do it” (p. 91).

Therefore, attempting to formulate a semantic definition of quality education with syntax-based metrics results in what O’Neil (O'Neil 2017 ) terms surrogate models that are rough approximations and oversimplified. Further, the derived metrics tend to morph into goals or benchmarks, losing their original measurement properties (Goodhart 1975 ).

Information communication technologies in society and education

Blended learning forces us to consider the characteristics of digital technology, in general, and information communication technologies (ICTs), more specifically. Floridi ( 2014 ) suggests an answer proffered by Alan Turing: that digital ICTs can process information on their own, in some sense just as humans and other biological life. ICTs can also communicate information to each other, without human intervention, but as linked processes designed by humans. We have evolved to the point where humans are not always “in the loop” of technology, but should be “on the loop” (Floridi 2014 , p. 30), designing and adapting the process. We perceive our world more and more in informational terms, and not primarily as physical entities (Floridi 2008 ). Increasingly, the educational world is dominated by information and our economies rest primarily on that asset. So our world is also blended, and it is blended so much that we hardly see the individual components of the blend any longer. Floridi ( 2014 ) argues that the world has become an “infosphere” (like biosphere) where we live as “inforgs.” What is real for us is shifting from the physical and unchangeable to those things with which we can interact.

Floridi also helps us to identify the next blend in education, involving ICTs, or specialized artificial intelligence (Floridi 2014 , 25; Norberg 2017 , 65). Learning analytics, adaptive learning, calibrated peer review, and automated essay scoring (Balfour 2013 ) are advanced processes that, provided they are good interfaces, can work well with the teacher— allowing him or her to concentrate on human attributes such as being caring, creative, and engaging in problem-solving. This can, of course, as with all technical advancements, be used to save resources and augment the role of the teacher. For instance, if artificial intelligence can be used to work along with teachers, allowing them more time for personal feedback and mentoring with students, then, we will have made a transformational breakthrough. The Edinburg University manifesto for teaching online says bravely, “Automation need not impoverish education – we welcome our robot colleagues” (Bayne et al. 2016 ). If used wisely, they will teach us more about ourselves, and about what is truly human in education. This emerging blend will also affect curricular and policy questions, such as the what? and what for? The new normal for education will be in perpetual flux. Floridi’s ( 2014 ) philosophy offers us tools to understand and be in control and not just sit by and watch what happens. In many respects, he has addressed the new normal for blended learning.

Literature of blended learning

A number of investigators have assembled a comprehensive agenda of transformative and innovative research issues for blended learning that have the potential to enhance effectiveness (Garrison and Kanuka 2004 ; Picciano 2009 ). Generally, research has found that BL results in improvement in student success and satisfaction, (Dziuban and Moskal 2011 ; Dziuban et al. 2011 ; Means et al. 2013 ) as well as an improvement in students’ sense of community (Rovai and Jordan 2004 ) when compared with face-to-face courses. Those who have been most successful at blended learning initiatives stress the importance of institutional support for course redesign and planning (Moskal et al. 2013 ; Dringus and Seagull 2015 ; Picciano 2009 ; Tynan et al. 2015 ). The evolving research questions found in the literature are long and demanding, with varied definitions of what constitutes “blended learning,” facilitating the need for continued and in-depth research on instructional models and support needed to maximize achievement and success (Dringus and Seagull 2015 ; Bloemer and Swan 2015 ).

Educational access

The lack of access to educational technologies and innovations (sometimes termed the digital divide) continues to be a challenge with novel educational technologies (Fairlie 2004 ; Jones et al. 2009 ). One of the promises of online technologies is that they can increase access to nontraditional and underserved students by bringing a host of educational resources and experiences to those who may have limited access to on-campus-only higher education. A 2010 U.S. report shows that students with low socioeconomic status are less likely to obtain higher levels of postsecondary education (Aud et al. 2010 ). However, the increasing availability of distance education has provided educational opportunities to millions (Lewis and Parsad 2008 ; Allen et al. 2016 ). Additionally, an emphasis on open educational resources (OER) in recent years has resulted in significant cost reductions without diminishing student performance outcomes (Robinson et al. 2014 ; Fischer et al. 2015 ; Hilton et al. 2016 ).

Unfortunately, the benefits of access may not be experienced evenly across demographic groups. A 2015 study found that Hispanic and Black STEM majors were significantly less likely to take online courses even when controlling for academic preparation, socioeconomic status (SES), citizenship, and English as a second language (ESL) status (Wladis et al. 2015 ). Also, questions have been raised about whether the additional access afforded by online technologies has actually resulted in improved outcomes for underserved populations. A distance education report in California found that all ethnic minorities (except Asian/Pacific Islanders) completed distance education courses at a lower rate than the ethnic majority (California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office 2013 ). Shea and Bidjerano ( 2014 , 2016 ) found that African American community college students who took distance education courses completed degrees at significantly lower rates than those who did not take distance education courses. On the other hand, a study of success factors in K-12 online learning found that for ethnic minorities, only 1 out of 15 courses had significant gaps in student test scores (Liu and Cavanaugh 2011 ). More research needs to be conducted, examining access and success rates for different populations, when it comes to learning in different modalities, including fully online and blended learning environments.

Framing a treatment effect

Over the last decade, there have been at least five meta-analyses that have addressed the impact of blended learning environments and its relationship to learning effectiveness (Zhao et al. 2005 ; Sitzmann et al. 2006 ; Bernard et al. 2009 ; Means et al. 2010 , 2013 ; Bernard et al. 2014 ). Each of these studies has found small to moderate positive effect sizes in favor of blended learning when compared to fully online or traditional face-to-face environments. However, there are several considerations inherent in these studies that impact our understanding the generalizability of outcomes.

Dziuban and colleagues (Dziuban et al. 2015 ) analyzed the meta-analyses conducted by Means and her colleagues (Means et al. 2013 ; Means et al. 2010 ), concluding that their methods were impressive as evidenced by exhaustive study inclusion criteria and the use of scale-free effect size indices. The conclusion, in both papers, was that there was a modest difference in multiple outcome measures for courses featuring online modalities—in particular, blended courses. However, with blended learning especially, there are some concerns with these kinds of studies. First, the effect sizes are based on the linear hypothesis testing model with the underlying assumption that the treatment and the error terms are uncorrelated, indicating that there is nothing else going on in the blending that might confound the results. Although the blended learning articles (Means et al. 2010 ) were carefully vetted, the assumption of independence is tenuous at best so that these meta-analysis studies must be interpreted with extreme caution.

There is an additional concern with blended learning as well. Blends are not equivalent because of the manner on which they are configured. For instance, a careful reading of the sources used in the Means, et al. papers will identify, at minimum, the following blending techniques: laboratory assessments, online instruction, e-mail, class web sites, computer laboratories, mapping and scaffolding tools, computer clusters, interactive presentations and e-mail, handwriting capture, evidence-based practice, electronic portfolios, learning management systems, and virtual apparatuses. These are not equivalent ways in which to configure courses, and such nonequivalence constitutes the confounding we describe. We argue here that, in actuality, blended learning is a general construct in the form of a boundary object (Star and Griesemer 1989 ) rather than a treatment effect in the statistical sense. That is, an idea or concept that can support a community of practice, but is weakly defined fostering disagreement in the general group. Conversely, it is stronger in individual constituencies. For instance, content disciplines (i.e. education, rhetoric, optics, mathematics, and philosophy) formulate a more precise definition because of commonly embraced teaching and learning principles. Quite simply, the situation is more complicated than that, as Leonard Smith ( 2007 ) says after Tolstoy,

“All linear models resemble each other, each non nonlinear system is unique in its own way” (p. 33).

This by no means invalidates these studies, but effect size associated with blended learning should be interpreted with caution where the impact is evaluated within a particular learning context.

Study objectives

This study addressed student access by examining success and withdrawal rates in the blended learning courses by comparing them to face-to-face and online modalities over an extended time period at the University of Central Florida. Further, the investigators sought to assess the differences in those success and withdrawal rates with the minority status of students. Secondly, the investigators examined the student end-of-course ratings of blended learning and other modalities by attempting to develop robust if-then decision rules about what characteristics of classes and instructors lead students to assign an “excellent” value to their educational experience. Because of the high stakes nature of these student ratings toward faculty promotion, awards, and tenure, they act as a surrogate measure for instructional quality. Next, the investigators determined the conditional probabilities for students conforming to the identified rule cross-referenced by expected grade, the degree to which they desired to take the course, and course modality.

Student grades by course modality were recoded into a binary variable with C or higher assigned a value of 1, and remaining values a 0. This was a declassification process that sacrificed some specificity but compensated for confirmation bias associated with disparate departmental policies regarding grade assignment. At the measurement level this was an “on track to graduation index” for students. Withdrawal was similarly coded by the presence or absence of its occurrence. In each case, the percentage of students succeeding or withdrawing from blended, online or face-to-face courses was calculated by minority and non-minority status for the fall 2014 through fall 2015 semesters.

Next, a classification and regression tree (CART) analysis (Brieman et al. 1984 ) was performed on the student end-of-course evaluation protocol ( Appendix 1 ). The dependent measure was a binary variable indicating whether or not a student assigned an overall rating of excellent to his or her course experience. The independent measures in the study were: the remaining eight rating items on the protocol, college membership, and course level (lower undergraduate, upper undergraduate, and graduate). Decision trees are efficient procedures for achieving effective solutions in studies such as this because with missing values imputation may be avoided with procedures such as floating methods and the surrogate formation (Brieman et al. 1984 , Olshen et al. 1995 ). For example, a logistic regression method cannot efficiently handle all variables under consideration. There are 10 independent variables involved here; one variable has three levels, another has nine, and eight have five levels each. This means the logistic regression model must incorporate more than 50 dummy variables and an excessively large number of two-way interactions. However, the decision-tree method can perform this analysis very efficiently, permitting the investigator to consider higher order interactions. Even more importantly, decision trees represent appropriate methods in this situation because many of the variables are ordinally scaled. Although numerical values can be assigned to each category, those values are not unique. However, decision trees incorporate the ordinal component of the variables to obtain a solution. The rules derived from decision trees have an if-then structure that is readily understandable. The accuracy of these rules can be assessed with percentages of correct classification or odds-ratios that are easily understood. The procedure produces tree-like rule structures that predict outcomes.

The model-building procedure for predicting overall instructor rating

For this study, the investigators used the CART method (Brieman et al. 1984 ) executed with SPSS 23 (IBM Corp 2015 ). Because of its strong variance-sharing tendencies with the other variables, the dependent measure for the analysis was the rating on the item Overall Rating of the Instructor , with the previously mentioned indicator variables (college, course level, and the remaining 8 questions) on the instrument. Tree methods are recursive, and bisect data into subgroups called nodes or leaves. CART analysis bases itself on: data splitting, pruning, and homogeneous assessment.

Splitting the data into two (binary) subsets comprises the first stage of the process. CART continues to split the data until the frequencies in each subset are either very small or all observations in a subset belong to one category (e.g., all observations in a subset have the same rating). Usually the growing stage results in too many terminate nodes for the model to be useful. CART solves this problem using pruning methods that reduce the dimensionality of the system.

The final stage of the analysis involves assessing homogeneousness in growing and pruning the tree. One way to accomplish this is to compute the misclassification rates. For example, a rule that produces a .95 probability that an instructor will receive an excellent rating has an associated error of 5.0%.

Implications for using decision trees

Although decision-tree techniques are effective for analyzing datasets such as this, the reader should be aware of certain limitations. For example, since trees use ranks to analyze both ordinal and interval variables, information can be lost. However, the most serious weakness of decision tree analysis is that the results can be unstable because small initial variations can lead to substantially different solutions.

For this study model, these problems were addressed with the k-fold cross-validation process. Initially the dataset was partitioned randomly into 10 subsets with an approximately equal number of records in each subset. Each cohort is used as a test partition, and the remaining subsets are combined to complete the function. This produces 10 models that are all trained on different subsets of the original dataset and where each has been used as the test partition one time only.

Although computationally dense, CART was selected as the analysis model for a number of reasons— primarily because it provides easily interpretable rules that readers will be able evaluate in their particular contexts. Unlike many other multivariate procedures that are even more sensitive to initial estimates and require a good deal of statistical sophistication for interpretation, CART has an intuitive resonance with researcher consumers. The overriding objective of our choice of analysis methods was to facilitate readers’ concentration on our outcomes rather than having to rely on our interpretation of the results.

Institution-level evaluation: Success and withdrawal

The University of Central Florida (UCF) began a longitudinal impact study of their online and blended courses at the start of the distributed learning initiative in 1996. The collection of similar data across multiple semesters and academic years has allowed UCF to monitor trends, assess any issues that may arise, and provide continual support for both faculty and students across varying demographics. Table 1 illustrates the overall success rates in blended, online and face-to-face courses, while also reporting their variability across minority and non-minority demographics.

While success (A, B, or C grade) is not a direct reflection of learning outcomes, this overview does provide an institutional level indication of progress and possible issues of concern. BL has a slight advantage when looking at overall success and withdrawal rates. This varies by discipline and course, but generally UCF’s blended modality has evolved to be the best of both worlds, providing an opportunity for optimizing face-to-face instruction through the effective use of online components. These gains hold true across minority status. Reducing on-ground time also addresses issues that impact both students and faculty such as parking and time to reach class. In addition, UCF requires faculty to go through faculty development tailored to teaching in either blended or online modalities. This 8-week faculty development course is designed to model blended learning, encouraging faculty to redesign their course and not merely consider blended learning as a means to move face-to-face instructional modules online (Cobb et al. 2012 ; Lowe 2013 ).

Withdrawal (Table 2 ) from classes impedes students’ success and retention and can result in delayed time to degree, incurred excess credit hour fees, or lost scholarships and financial aid. Although grades are only a surrogate measure for learning, they are a strong predictor of college completion. Therefore, the impact of any new innovation on students’ grades should be a component of any evaluation. Once again, the blended modality is competitive and in some cases results in lower overall withdrawal rates than either fully online or face-to-face courses.

The students’ perceptions of their learning environments

Other potentially high-stakes indicators can be measured to determine the impact of an innovation such as blended learning on the academy. For instance, student satisfaction and attitudes can be measured through data collection protocols, including common student ratings, or student perception of instruction instruments. Given that those ratings often impact faculty evaluation, any negative reflection can derail the successful implementation and scaling of an innovation by disenfranchised instructors. In fact, early online and blended courses created a request by the UCF faculty senate to investigate their impact on faculty ratings as compared to face-to-face sections. The UCF Student Perception of Instruction form is released automatically online through the campus web portal near the end of each semester. Students receive a splash page with a link to each course’s form. Faculty receive a scripted email that they can send to students indicating the time period that the ratings form will be available. The forms close at the beginning of finals week. Faculty receive a summary of their results following the semester end.

The instrument used for this study was developed over a ten year period by the faculty senate of the University of Central Florida, recognizing the evolution of multiple course modalities including blended learning. The process involved input from several constituencies on campus (students, faculty, administrators, instructional designers, and others), in attempt to provide useful formative and summative instructional information to the university community. The final instrument was approved by resolution of the senate and, currently, is used across the university. Students’ rating of their classes and instructors comes with considerable controversy and disagreement with researchers aligning themselves on both sides of the issue. Recently, there have been a number of studies criticizing the process (Uttl et al. 2016 ; Boring et al. 2016 ; & Stark and Freishtat 2014 ). In spite of this discussion, a viable alternative has yet to emerge in higher education. So in the foreseeable future, the process is likely to continue. Therefore, with an implied faculty senate mandate this study was initiated by this team of researchers.

Prior to any analysis of the item responses collected in this campus-wide student sample, the psychometric quality (domain sampling) of the information yielded by the instrument was assessed. Initially, the reliability (internal consistency) was derived using coefficient alpha (Cronbach 1951 ). In addition, Guttman ( 1953 ) developed a theorem about item properties that leads to evidence about the quality of one’s data, demonstrating that as the domain sampling properties of items improve, the inverse of the correlation matrix among items will approach a diagonal. Subsequently, Kaiser and Rice ( 1974 ) developed the measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) that is a function of the Guttman Theorem. The index has an upper bound of one with Kaiser offering some decision rules for interpreting the value of MSA. If the value of the index is in the .80 to .99 range, the investigator has evidence of an excellent domain sample. Values in the .70s signal an acceptable result, and those in the .60s indicate data that are unacceptable. Customarily, the MSA has been used for data assessment prior to the application of any dimensionality assessments. Computation of the MSA value gave the investigators a benchmark for the construct validity of the items in this study. This procedure has been recommended by Dziuban and Shirkey ( 1974 ) prior to any latent dimension analysis and was used with the data obtained for this study. The MSA for the current instrument was .98 suggesting excellent domain sampling properties with an associated alpha reliability coefficient of .97 suggesting superior internal consistency. The psychometric properties of the instrument were excellent with both measures.

The online student ratings form presents an electronic data set each semester. These can be merged across time to create a larger data set of completed ratings for every course across each semester. In addition, captured data includes course identification variables including prefix, number, section and semester, department, college, faculty, and class size. The overall rating of effectiveness is used most heavily by departments and faculty in comparing across courses and modalities (Table 3 ).

The finally derived tree (decision rules) included only three variables—survey items that asked students to rate the instructor’s effectiveness at:

Helping students achieve course objectives,

Creating an environment that helps students learn, and

Communicating ideas and information.

None of the demographic variables associated with the courses contributed to the final model. The final rule specifies that if a student assigns an excellent rating to those three items, irrespective of their status on any other condition, the probability is .99 that an instructor will receive an overall rating of excellent. The converse is true as well. A poor rating on all three of those items will lead to a 99% chance of an instructor receiving an overall rating of poor.

Tables 4 , 5 and 6 present a demonstration of the robustness of the CART rule for variables on which it was not developed: expected course grade, desire to take the course and modality.

In each case, irrespective of the marginal probabilities, those students conforming to the rule have a virtually 100% chance of seeing the course as excellent. For instance, 27% of all students expecting to fail assigned an excellent rating to their courses, but when they conformed to the rule the percentage rose to 97%. The same finding is true when students were asked about their desire to take the course with those who strongly disagreed assigning excellent ratings to their courses 26% of the time. However, for those conforming to the rule, that category rose to 92%. When course modality is considered in the marginal sense, blended learning is rated as the preferred choice. However, from Table 6 we can observe that the rule equates student assessment of their learning experiences. If they conform to the rule, they will see excellence.

This study addressed increasingly important issues of student success, withdrawal and perception of the learning environment across multiple course modalities. Arguably these components form the crux of how we will make more effective decisions about how blended learning configures itself in the new normal. The results reported here indicate that blending maintains or increases access for most student cohorts and produces improved success rates for minority and non-minority students alike. In addition, when students express their beliefs about the effectiveness of their learning environments, blended learning enjoys the number one rank. However, upon more thorough analysis of key elements students view as important in their learning, external and demographic variables have minimal impact on those decisions. For example college (i.e. discipline) membership, course level or modality, expected grade or desire to take a particular course have little to do with their course ratings. The characteristics they view as important relate to clear establishment and progress toward course objectives, creating an effective learning environment and the instructors’ effective communication. If in their view those three elements of a course are satisfied they are virtually guaranteed to evaluate their educational experience as excellent irrespective of most other considerations. While end of course rating protocols are summative the three components have clear formative characteristics in that each one is directly related to effective pedagogy and is responsive to faculty development through units such as the faculty center for teaching and learning. We view these results as encouraging because they offer potential for improving the teaching and learning process in an educational environment that increases the pressure to become more responsive to contemporary student lifestyles.

Clearly, in this study we are dealing with complex adaptive systems that feature the emergent property. That is, their primary agents and their interactions comprise an environment that is more than the linear combination of their individual elements. Blending learning, by interacting with almost every aspect of higher education, provides opportunities and challenges that we are not able to fully anticipate.

This pedagogy alters many assumptions about the most effective way to support the educational environment. For instance, blending, like its counterpart active learning, is a personal and individual phenomenon experienced by students. Therefore, it should not be surprising that much of what we have called blended learning is, in reality, blended teaching that reflects pedagogical arrangements. Actually, the best we can do for assessing impact is to use surrogate measures such as success, grades, results of assessment protocols, and student testimony about their learning experiences. Whether or not such devices are valid indicators remains to be determined. We may be well served, however, by changing our mode of inquiry to blended teaching.

Additionally, as Norberg ( 2017 ) points out, blended learning is not new. The modality dates back, at least, to the medieval period when the technology of textbooks was introduced into the classroom where, traditionally, the professor read to the students from the only existing manuscript. Certainly, like modern technologies, books were disruptive because they altered the teaching and learning paradigm. Blended learning might be considered what Johnson describes as a slow hunch (2010). That is, an idea that evolved over a long period of time, achieving what Kaufmann ( 2000 ) describes as the adjacent possible – a realistic next step occurring in many iterations.

The search for a definition for blended learning has been productive, challenging, and, at times, daunting. The definitional continuum is constrained by Oliver and Trigwell ( 2005 ) castigation of the concept for its imprecise vagueness to Sharpe et al.’s ( 2006 ) notion that its definitional latitude enhances contextual relevance. Both extremes alter boundaries such as time, place, presence, learning hierarchies, and space. The disagreement leads us to conclude that Lakoff’s ( 2012 ) idealized cognitive models i.e. arbitrarily derived concepts (of which blended learning might be one) are necessary if we are to function effectively. However, the strong possibility exists that blended learning, like quality, is observer dependent and may not exist outside of our perceptions of the concept. This, of course, circles back to the problem of assuming that blending is a treatment effect for point hypothesis testing and meta-analysis.

Ultimately, in this article, we have tried to consider theoretical concepts and empirical findings about blended learning and their relationship to the new normal as it evolves. Unfortunately, like unresolved chaotic solutions, we cannot be sure that there is an attractor or that it will be the new normal. That being said, it seems clear that blended learning is the harbinger of substantial change in higher education and will become equally impactful in K-12 schooling and industrial training. Blended learning, because of its flexibility, allows us to maximize many positive education functions. If Floridi ( 2014 ) is correct and we are about to live in an environment where we are on the communication loop rather than in it, our educational future is about to change. However, if our results are correct and not over fit to the University of Central Florida and our theoretical speculations have some validity, the future of blended learning should encourage us about the coming changes.

Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M., Davis, A., Freeman, A., Hall Giesinger, C., & Ananthanarayanan, V. (2017). NMC horizon report: 2017 higher Education Edition . Austin: The New Media Consortium.

Google Scholar

Alhabeeb, A. M. (2015). The quality assessment of the services offered to the students of the College of Education at King Saud University using (SERVQUAL) method. Journal of Education and Practice , 6 (30), 82–93.

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2003). Sizing the opportunity: The quality and extent of online education in the United States, 2002 and 2003. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED530060.pdf

Allen, I. E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., & Straut, T. T. (2016). Online report card: Tracking online education in the United States, 1–4. Retrieved from http://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/onlinereportcard.pdf

Arum, R., Roksa, J., & Cook, A. (2016). Improving quality in American higher education: Learning outcomes and assessments for the 21st century . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Aud, S., Hussar, W., Planty, M., Snyder, T., Bianco, K., Fox, M. A., & Drake, L. (2010). The condition of education - 2010. Education, 4–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/e492172006-019

Balfour, S. P. (2013). Assessing writing in MOOCs: Automated essay scoring and calibrated peer review. Research and Practice in Assessment , 2013 (8), 40–48.

Bayne, S., Evans, P., Ewins, R.,Knox, J., Lamb, J., McLeod, H., O’Shea, C., Ross, J., Sheail, P. & Sinclair, C, (2016) Manifesto for teaching online. Digital Education at Edinburg University. Retrieved from https://onlineteachingmanifesto.wordpress.com/the-text/

Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Borokhovski, E., Wade, C. A., Tamim, R. M., Surkes, M. A., & Bethel, E. C. (2009). A meta-analysis of three types of interaction treatments in distance education. Review of Educational Research , 79 (3), 1243–1289. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309333844 .

Article Google Scholar

Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Schmid, R. F., Tamim, R. M., & Abrami, P. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education: From the general to the applied. Journal of Computing in Higher Education , 26 (1), 87–122.

Bloemer, W., & Swan, K. (2015). Investigating informal blending at the University of Illinois Springfield. In A. G. Picciano, C. D. Dziuban, & C. R. Graham (Eds.), Blended learning: Research perspectives , (vol. 2, pp. 52–69). New York: Routledge.

Bonk, C. J., & Graham, C. R. (2007). The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs . San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Boring, A., Ottoboni, K., & Stark, P.B. (2016). Student evaluations of teaching (mostly) do not measure teaching effectiveness. EGERA.

Brieman, L., Friedman, J. H., Olshen, R. A., & Stone, C. J. (1984). Classification and regression trees . New York: Chapman & Hall.

California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office. (2013). Distance education report.

Cobb, C., deNoyelles, A., & Lowe, D. (2012). Influence of reduced seat time on satisfaction and perception of course development goals: A case study in faculty development. The Journal of Asynchronous Learning , 16 (2), 85–98.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika , 16 (3), 297–334 Retrieved from http://psych.colorado.edu/~carey/courses/psyc5112/readings/alpha_cronbach.pdf .

Article MATH Google Scholar

Dringus, L. P., and A. B. Seagull. 2015. A five-year study of sustaining blended learning initiatives to enhance academic engagement in computer and information sciences campus courses. In Blended learning: Research perspectives. Vol. 2. Edited by A. G. Picciano, C. D. Dziuban, and C. R. Graham, 122-140. New York: Routledge.

Dziuban, C. D., & Shirkey, E. C. (1974). When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Some decision rules. Psychological Bulletin , 81(6), 358. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036316 .

Dziuban, C., Hartman, J., Cavanagh, T., & Moskal, P. (2011). Blended courses as drivers of institutional transformation. In A. Kitchenham (Ed.), Blended learning across disciplines: Models for implementation , (pp. 17–37). Hershey: IGI Global.

Chapter Google Scholar

Dziuban, C., & Moskal, P. (2011). A course is a course is a course: Factor invariance in student evaluation of online, blended and face-to-face learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education , 14 (4), 236–241.

Dziuban, C., Moskal, P., Hermsdorfer, A., DeCantis, G., Norberg, A., & Bradford, G., (2015) A deconstruction of blended learning. Presented at the 11 th annual Sloan-C blended learning conference and workshop

Dziuban, C., Picciano, A. G., Graham, C. R., & Moskal, P. D. (2016). Conducting research in online and blended learning environments: New pedagogical frontiers . New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Dziuban, C. D., Hartman, J. L., & Moskal, P. D. (2004). Blended learning. EDUCAUSE Research Bulletin , 7 , 1–12.

EDUCAUSE. (2017) 2017 key issues in teaching & learning. Retrieved from https://www.EDUCAUSE.edu/eli/initiatives/key-issues-in-teaching-and-learning

Fairlie, R. (2004). Race and the digital divide. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy , 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1538-0645.1263 .

Fischer, L., Hilton, J., Robinson, T. J., & Wiley, D. (2015). A Multi-institutional Study of the Impact of Open Textbook Adoption on the Learning Outcomes of Post-secondary Students . Journal of Computing in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-015-9101-x .

Floridi, L. (2008). A defence of informational structural realism. Synthese , 161 (2), 219–253.

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Floridi, L. (2014). The 4th revolution: How the infosphere is reshaping human reality . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garrison, D. R., & Vaughan, N. D. (2013). Blended learning in higher education , (1st ed., ). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Print.

Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education , 7 , 95–105.

Goodhart, C.A.E. (1975). “Problems of monetary management: The U.K. experience.” Papers in Monetary Economics. Reserve Bank of Australia. I.

Graham, C. R. (2013). Emerging practice and research in blended learning. In M. G. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of distance education , (3rd ed., pp. 333–350). New York: Routledge.

Guttman, L. (1953). Image theory for the structure of quantitative variates. Psychometrika , 18 , 277–296.

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Hilton, J., Fischer, L., Wiley, D., & Williams, L. (2016). Maintaining momentum toward graduation: OER and the course throughput rate. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning , 17 (6) https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i6.2686 .

IBM Corp. Released (2015). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 23.0 . Armonk: IBM Corp.

Jean-François, E. (2013). Transcultural blended learning and teaching in postsecondary education . Hershey: Information Science Reference.

Book Google Scholar

Jones, S., Johnson-Yale, C., Millermaier, S., & Pérez, F. S. (2009). U.S. college students’ internet use: Race, gender and digital divides. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 14 (2), 244–264 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01439.x .

Kaiser, H. F., & Rice, J. (1974). Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Journal of Educational and Psychological Measurement , 34(1), 111–117.

Kaufmann, S. (2000). Investigations . New York: Oxford University Press.

Kitchenham, A. (2011). Blended learning across disciplines: Models for implementation . Hershey: Information Science Reference.

Lakoff, G. (2012). Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Lewis, L., & Parsad, B. (2008). Distance education at degree-granting postsecondary institutions : 2006–07 (NCES 2009–044) . Washington: Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2009/2009044.pdf .

Liu, F., & Cavanaugh, C. (2011). High enrollment course success factors in virtual school: Factors influencing student academic achievement. International Journal on E-Learning , 10 (4), 393–418.

Lowe, D. (2013). Roadmap of a blended learning model for online faculty development. Invited feature article in Distance Education Report , 17 (6), 1–7.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., & Baki, M. (2013). The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers College Record , 115 (3), 1–47.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Kaia, M., & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning . Washington: US Department of Education.

Moskal, P., Dziuban, C., & Hartman, J. (2013). Blended learning: A dangerous idea? The Internet and Higher Education , 18 , 15–23.

Norberg, A. (2017). From blended learning to learning onlife: ICTs, time and access in higher education (Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University).

Norberg, A., Dziuban, C. D., & Moskal, P. D. (2011). A time-based blended learning model. On the Horizon , 19 (3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748121111163913 .

Oliver, M., & Trigwell, K. (2005). Can ‘blended learning’ be redeemed? e-Learning , 2 (1), 17–25.

Olshen, Stone , Steinberg , and Colla (1995). CART classification and regression trees. Tree-structured nonparametric data analysis. Statistical algorithms. Salford systems interface and documentation. Salford Systems .

O'Neil, C. (2017). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy . Broadway Books.

Online Learning Consortium. The OLC quality scorecard for blended learning programs. Retrieved from https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/consult/olc-quality-scorecard-blended-learning-programs/

Open SUNY. The OSCQR course design review scorecard. Retrieved from https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/consult/oscqr-course-design-review/

Picciano, A. G. (2009). Blending with purpose: The multimodal model. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks , 13 (1), 7–18.

Picciano, A. G., Dziuban, C., & Graham, C. R. (2014). Blended learning: Research perspectives , (vol. 2). New York: Routledge.

Picciano, A. G., & Dziuban, C. D. (2007). Blended learning: Research perspectives . Needham: The Sloan Consortium.

Pirsig, R. M. (1974). Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance: An inquiry into values . New York: Morrow.

Quality Matters. (2016). About Quality Matters. Retrieved from https://www.qualitymatters.org/research

Robinson, T. J., Fischer, L., Wiley, D. A., & Hilton, J. (2014). The Impact of Open Textbooks on Secondary Science Learning Outcomes . Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14550275 .

Ross, B., & Gage, K. (2006). Global perspectives on blended learning: Insight from WebCT and our customers in higher education. In C. J. Bonk, & C. R. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs , (pp. 155–168). San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Rovai, A. P., & Jordan, H. M. (2004). Blended learning and sense of community: A comparative analysis with traditional and fully online graduate courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning , 5 (2), 1–13.

Searle, J. R. (2015). Seeing things as they are: A theory of perception . Chicago: Oxford University Press.

Sharpe, R., Benfield, G., Roberts, G., & Francis, R. (2006). The undergraduate experience of blended learning: A review of UK literature and research. The Higher Education Academy, (October 2006).

Shea, P., & Bidjerano, T. (2014). Does online learning impede degree completion? A national study of community college students. Computers and Education , 75 , 103–111 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.02.009 .

Shea, P., & Bidjerano, T. (2016). A National Study of differences between distance and non-distance community college students in time to first associate degree attainment, transfer, and dropout. Online Learning , 20 (3), 14–15.

Sitzmann, T., Kraiger, K., Stewart, D., & Wisher, R. (2006). The comparative effectiveness of web-based and classroom instruction: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology , 59 (3), 623–664.

Smith, L. A. (2007). Chaos: a very short introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, translations and boundary objects: Amatuers and professionals in Berkely’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science , 19 (3), 387–420.

Stark, P. & Freishtat, R. (2014). An evaluation of course evaluations. ScienceOpen. Retrieved from https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~stark/Preprints/evaluations14.pdf .

Tynan, B., Ryan, Y., & Lamont-Mills, A. (2015). Examining workload models in online and blended teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology , 46 (1), 5–15.

Uttl, B., White, C. A., & Gonzalez, D. W. (2016). Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation , 54 , 22–42.

Williams, J. (2016). College and the new class divide. Inside Higher Ed July 11, 2016.

Wladis, C., Hachey, A. C., & Conway, K. (2015). Which STEM majors enroll in online courses, and why should we care? The impact of ethnicity, gender, and non-traditional student characteristics. Computers and Education , 87 , 285–308 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.06.010 .

Zhao, Y., Lei, J., Yan, B., Lai, C., & Tan, H. S. (2005). What makes the difference? A practical analysis of research on the effectiveness of distance education. Teachers College Record , 107 (8), 1836–1884. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2005.00544.x .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of several investigators and course developers from the Center for Distributed Learning at the University of Central Florida, the McKay School of Education at Brigham Young University, and Scholars at Umea University, Sweden. These professionals contributed theoretical and practical ideas to this research project and carefully reviewed earlier versions of this manuscript. The Authors gratefully acknowledge their support and assistance.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Central Florida, Orlando, Florida, USA

Charles Dziuban, Patsy D. Moskal & Nicole Sicilia

Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA

Charles R. Graham

Campus Skellefteå, Skellefteå, Sweden

Anders Norberg

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The Authors of this article are listed in alphabetical order indicating equal contribution to this article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Patsy D. Moskal .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Student Perception of Instruction

Instructions: Please answer each question based on your current class experience. You can provide additional information where indicated.

All responses are anonymous. Responses to these questions are important to help improve the course and how it is taught. Results may be used in personnel decisions. The results will be shared with the instructor after the semester is over.

Please rate the instructor’s effectiveness in the following areas:

Organizing the course:

Excellent b) Very Good c) Good d) Fair e) Poor

Explaining course requirements, grading criteria, and expectations:

Communicating ideas and/or information:

Showing respect and concern for students:

Stimulating interest in the course:

Creating an environment that helps students learn:

Giving useful feedback on course performance:

Helping students achieve course objectives:

Overall, the effectiveness of the instructor in this course was:

What did you like best about the course and/or how the instructor taught it?

What suggestions do you have for improving the course and/or how the instructor taught it?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dziuban, C., Graham, C.R., Moskal, P.D. et al. Blended learning: the new normal and emerging technologies. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 15 , 3 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0087-5

Download citation

Received : 09 October 2017

Accepted : 20 December 2017

Published : 15 February 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0087-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Blended learning

- Higher education

- Student success

- Student perception of instruction

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Learning curves in covid-19: student strategies in the ‘new normal’.

- Auckland University of Technology, School of Sport and Recreation, Auckland, New Zealand

In New Zealand, similar to the rest of the world, the COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented disruption to higher education, with a rapid transition to mass online teaching. The 1st year (and 1st semester in particular) of any University degree presents unique challenges for students. Literature suggests these students have significant learning concerns as they adjust to University teaching and assessment requirements. These challenges may be exacerbated with the rapid introduction of online learning environments as they are increasingly disconnected from their peers, and, at a greater risk of struggling with web-based learning technologies.

This study investigated online learning strategies employed by 1st year students and examined the association between these strategies and student achievement. The University’s learning management system (LMS; Blackboard) was used to collect deidentified data related to students’ engagement with online content. The number of times content was clicked was recorded each day for the student’s three courses. These data were collected over a nine-week period for all students ( N = 170) enrolled in the 1st semester of their degree. This nine-week period spanned from the commencement of COVID-19 online learning to the week of final assessments. The relationship between assessment date and online engagement was investigated and linear mixed models were used to determine if engagement with online learning was associated with final course grades.

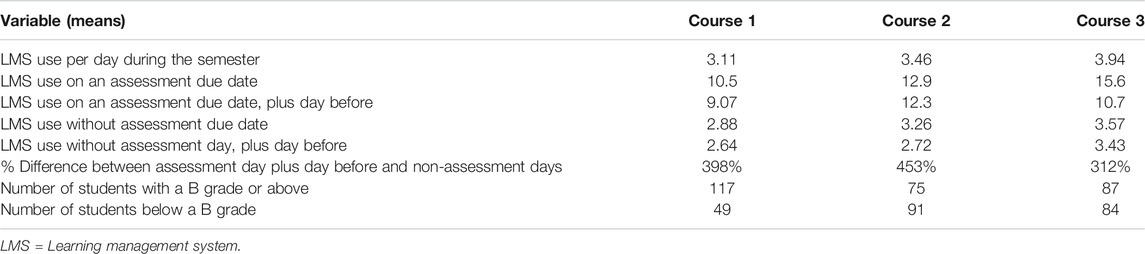

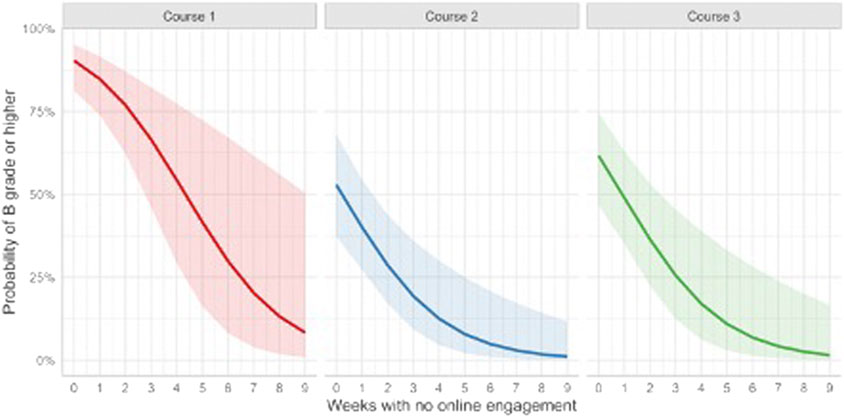

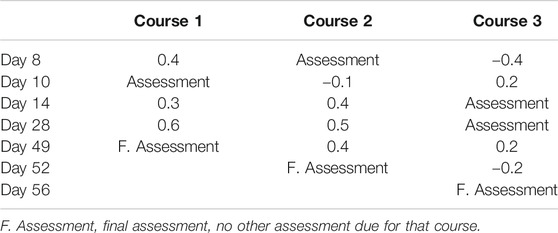

The results suggested that students adopted a learning strategy that coordinated their online LMS engagement with course assessment due date. Students had a 388% (SD 58%) greater specific engagement with the LMS on the assessment due date and the day prior, than throughout the remainder of their course. A further trend was observed whereby when an assessment was due in one course the students used an ‘online bundle learning’ strategy of increased engagement with the two other courses which has positive practical implications for the timing of uploading new teaching material. Finally, a clear relationship between the level of student LMS engagement and student course grade existed. For every additional week of zero LMS engagement, the odds of a student achieving. a grade lower than B were 1.67 times higher (95% CI 1.24, 2.26; p < 0.001), regardless of the course.

The rapid transition to online learning, as a consequence of COVID-19, has highlighted the risks of student disengagement, and the subsequent impact on lower student achievement across multiple courses. In addition, the authors investigated an ‘online learning bundling’ strategy that emerged; where students engaged more with a course when they were online submitting an assessment in a different course. These results emphasize the need for a university to implement greater cross-faculty coordination with reference to course design, uploading of information to LMS and timing of assessments. Improved coordination would provide a more effective online learning environment that maximizes student engagement and therefore achievement.

Introduction

The transition to higher education (HE) is often a complicated and difficult time for students ( Kember, 2001 ). Many new HE students have moved directly from secondary education to HE and are not used to the typical HE environment. This is characterized by less structured class time per week, less direct contact with peers and teachers, and a greater expectation for independent learning. New HE students need to adjust quickly to these different styles of teaching and assessments, while adapting to the demands of a self-directed and independent approach to their academic work. Successfully adjusting to this increased level of independence in the first year is important, as it has a strong influence on total student effort and level of achievement, as well as increasing the likelihood of the student completing the whole course ( Krause, 2001 , 2005 ). Ultimately, it is each students’ ability to adjust and engage in the HE environment that becomes a strong determinant of their level of engagement and achievement.

The HE environment has several non-academic factors that are related to student's success, time management, engagement and participation. Students must learn to cope with the new and often competing demands of the HE environment. For example, the juggle between work-life balance, and the peaks and troughs of workload. Research by Scherer et al. (2017) found that effective time management was a significant predictor of tertiary academic outcomes, as those with poor time management found it hard to plan and were often rushed at the end of a course or at assessment time. Literature highlights that in HE, there is a significantly positive relationship between students with who do manage their time effectively and academic performance ( Khan et al. (2020) ).

Snyder (1971) often referred to the concept of students understanding the ‘hidden curriculum’ (i.e., students knowing which key assessment points they need to attend and when, in order to achieve). This concept is important when trying to understand how students best strategize or allocate their attention and their time and has been discussed as a potential time-management issue ( Miller and Parlett, 1974 ). However, the concept that is under-researched is the balance between strategic use of time and potentially a miss-management of time, especially for 1st year HE students.

The second non-academic factor associated with academic success is student engagement, which is defined as ‘the quality of effort devoted to educationally purposeful activities that contribute directly to desired outcomes’ ( Chickering and Gamson, 1987 ). One way to consider engagement is that it is a gauge of the strength of the relationship between students and their HE institution. The HE institutions aim is to create an environment that affords learning to happen, but ultimately the final act of engagement lies with the student actions. Understanding and measuring student engagement in HE is a challenge, as it has multi-dimensional mechanisms, such as educational challenge, active learning, student-staff interaction, and support on campus, to name a few.

One weakness of traditionally measuring engagement in HE has been the lack of tools to objectively understand student engagement. The most commonly used tool is the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) which relies on self-reporting survey data. However, ‘active learning’ (i.e., frequency of class participation; Carini et al., 2006 ) has been used in previous research to provide an understanding of HE engagement level. Traditionally, this has been recorded during face-to-face HE program delivered on-campus that typically feature content taught in a classroom at a prescribed time, and supplemented with prescribed readings and assessment ( Broadbent, 2017 ). One of the more recent advancements in trying understanding student's interaction with the virtual environment in is the evolving area of HE is learning analytics (LA). In particular the use of large scale educational data about learners and their contexts. In this area, researchers have presented information about learners and their environment, with an attempt to provide models for future behavior ( Ranjeeth et al., 2020 ). However, it appears that with advances in LA there is still little recorded improvement to student learning, or learning support for students (e.g., Viberg et al., 2018 ). This raises the question about how insights from LA can help facilitate the transfer into learning and teaching practices.

Understanding engagement in online HE learning environments has shown mixed results when compared to face-to-face measures. Research has shown that students that have chosen their University course specifically because it is online are likely to be have been attracted by the high level of flexibility and independence it offers ( Bernard et al., 2004 ). They are confident they have the skills to excel, they enjoy the learning style and have the time management skills required to succeed in the online environment. Indeed, HE students have reported that time management and regular interaction with content and other students were the top skills needed to be successful with online learning ( Roper, 2007 ).

The impact of COVID-19 led to a rapid transition for most HE institutions from face-to-face teaching to online learning environments. While a few HE institutions had online courses or blended courses in place, the majority were not prepared for this rapid change to online delivery and therefore had minimal time to re-design course delivery for this new environment. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of research examining engagement with online learning tools, particularly for those who, due to COVID-19, are suddenly forced to transition from a face-to-face to online environment which was not their initial learning style choice. Many HE institutions use Learning Management Systems (LMS) and this provides an opportunity to explore student engagement via their online learning behaviors. While there are many inter-related factors that influence student engagement, the authors have attempted to respond to the call from Viberg et al. (2018) of combing the science of learning analytics with pedagogical knowledge. Therefore, in order to better support student achievement and enhance the understanding of student engagement behaviors the aims of this study are to; (1) to understand the online learning strategy of 1st year HE students (forced) into an online environment, and (2) to examine how the strategy adopted influences student achievement.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

One hundred and seventy students who were enrolled in three courses as part of the first semester of their undergraduate degree participated in this study. As a response to COVID-19 these students, that were originally enrolled in face-to-face courses, were transferred to online delivery from week three.

Two courses had two assessment points across the semester; one mid-term assessment, and one assessment at the end of semester. While the third course had three assessments. For each course the structure included live online lectures, pre-recorded video content, and weekly online tutorials. The online delivery for the three courses was completed over nine-week period.

Online Engagement

Online engagement and activity was defined as the log data collected by the LMS, e.g., time spent or number of interactions students had with the LMS ( Henrie et al., 2018 ). In this study online engagement was defined as the number of clicks per student recorded on the LMS. For each course online engagement data were extracted from the Blackboard Learning Management System using the in-built reporting feature. For each student, every time content was clicked (e.g., announcements, course materials, assessments) this information was recorded and stored within the LMS. While some engagement research uses log data of time spent logged into a page (e.g., Henrie et al., 2018 ), the authors found that this measure can give a false reading if a page was left open and not attended; thus giving the impression of a very long ‘engagement’ time with the LMS. Retrospective data covering the nine-week period were exported to an Excel spreadsheet, for each of the three courses separately. These data contained a daily breakdown of engagement information for each student (total number of clicks each day), for each of the three courses, across the nine-week period.

Student Achievement

Student achievement was measured using the final course grades that students received at the end of semester. The grading system ranged from 0 to 9, where 9 represented an ‘A+’ grade, 8 represented an ‘A’ grade, and 7 represented an ‘A−’. The lowest passing grade is 1 which represented a ‘C−’, while a 0 was a failure to pass. The final course grade was calculated by averaging the mid-term and final assessment grades.

In the first instance, student online engagement with each of the three courses were summarized using descriptive statistics (mean ± SD). The descriptive analysis was stratified by assessment days, non-assessment days, and the day prior to assessment day. The relationship between an assessment due date and change in online engagement in other courses was examined by calculating the difference between engagement on the due date and the days prior. These differences were presented as Cohen’s D effect sizes with the following thresholds: 0.2 = small effect, 0.5 = medium effect, 0.8 = large effect ( Cohen, 1988 ). All achievement and engagement data was de-identified in order that appropriate ethical standards were maintained.

Lastly, generalized linear mixed models were used to examine if the level of engagement with online content was associated with final course grades. The final grades were dichotomized into ‘B grade or higher’ and ‘Lower than a B grade’ (B grade = 5), as this was the middle grade. This was treated as the outcome variable. Student engagement data was summarized for each student as the number of weeks throughout the nine-week period where students recorded no engagement with the online LMS. This variable, along with the course (three levels) were added as fixed effects, while each student was added as a random effect to account for the repeated measures. These models were specified with a binomial distribution and logit link function and were fit in R software (v 4.0.0) using the lme4 package.

The results section present data to answer the two research aims; (1) To understand the 1st year student’s online learning strategy and engagement and, (2) to examine how the strategy adopted influences student achievement.

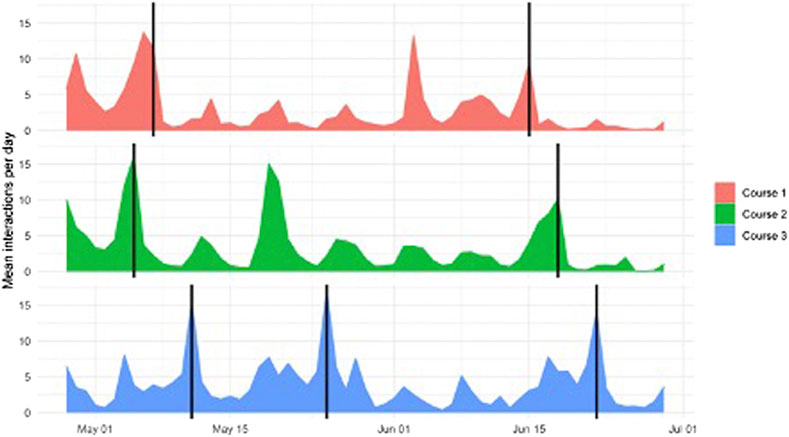

The mean number of online interactions per day, along with the assessment dates for each course, is shown below in Figure 1 . The spikes in student online engagement generally coincide with either the actual course assessment date ( Figure 1 , black vertical lines) or the uploading of key information related to an assessment onto the LMS ( Figure 1 , course 1(red) early June and course 2 (green) mid-May).

FIGURE 1 . The distribution of online engagement across the semester, for each course. The black vertical bars represent the assessment dates for each course.