F. Scott Fitzgerald

(1896-1940)

Who Was F. Scott Fitzgerald?

F. Scott Fitzgerald was a short story writer and novelist considered one of the pre-eminent authors in the history of American literature due almost entirely to the enormous posthumous success of his third book, The Great Gatsby . Perhaps the quintessential American novel, as well as a definitive social history of the Jazz Age, The Great Gatsby has become required reading for virtually every American high school student and has had a transportive effect on generation after generation of readers.

At the age of 24, the success of his first novel, This Side of Paradise , made Fitzgerald famous. One week later, he married the woman he loved and his muse, Zelda Sayre. However by the end of the 1920s Fitzgerald descended into drinking, and Zelda had a mental breakdown. Following the unsuccessful Tender Is the Night , Fitzgerald moved to Hollywood and became a scriptwriter. He died of a heart attack in 1940, at age 44, his final novel only half completed.

Family, Education and Early Life

Fitzgerald's mother, Mary McQuillan, was from an Irish-Catholic family that made a small fortune in Minnesota as wholesale grocers. His father, Edward Fitzgerald, had opened a wicker furniture business in St. Paul, and, when it failed, took a job as a salesman for Procter & Gamble. During the first decade of Fitzgerald's life, his father’s job took the family back and forth between Buffalo and Syracuse in upstate New York. When Fitzgerald was 12, Edward lost his job with Procter & Gamble, and the family moved back to St. Paul in 1908 to live off of his mother's inheritance.

Fitzgerald was a bright, handsome and ambitious boy, the pride and joy of his parents and especially his mother. He attended the St. Paul Academy. When he was 13, he saw his first piece of writing appear in print: a detective story published in the school newspaper. In 1911, when Fitzgerald was 15 years old, his parents sent him to the Newman School, a prestigious Catholic preparatory school in New Jersey. There, he met Father Sigourney Fay, who noticed his incipient talent with the written word and encouraged him to pursue his literary ambitions.

After graduating from the Newman School in 1913, Fitzgerald decided to stay in New Jersey to continue his artistic development at Princeton University. At Princeton, he firmly dedicated himself to honing his craft as a writer, writing scripts for Princeton's famous Triangle Club musicals as well as frequent articles for the Princeton Tiger humor magazine and stories for the Nassau Literary Magazine.

However, Fitzgerald's writing came at the expense of his coursework. He was placed on academic probation, and, in 1917, he dropped out of school to join the U.S. Army. Afraid that he might die in World War I with his literary dreams unfulfilled, in the weeks before reporting to duty, Fitzgerald hastily wrote a novel called The Romantic Egotist . Though the publisher, Charles Scribner's Sons, rejected the novel, the reviewer noted its originality and encouraged Fitzgerald to submit more work in the future.

Fitzgerald was commissioned a second lieutenant in the infantry and assigned to Camp Sheridan outside of Montgomery, Alabama. The war ended in November 1918, before Fitzgerald was ever deployed. Upon his discharge, he moved to New York City hoping to launch a career in advertising lucrative enough to convince his girlfriend, Zelda, to marry him. He quit his job after only a few months, however, and returned to St. Paul to rewrite his novel.

'This Side of Paradise' (1920)

This Side of Paradise is a largely autobiographical story about love and greed. The story was centered on Amory Blaine, an ambitious Midwesterner who falls in love with, but is ultimately rejected by, two girls from high-class families.

The novel was published in 1920 to glowing reviews. Almost overnight, it turned Fitzgerald, at the age of 24, into one of the country's most promising young writers. He eagerly embraced his newly minted celebrity status and embarked on an extravagant lifestyle that earned him a reputation as a playboy and hindered his reputation as a serious literary writer.

'The Beautiful and Damned' (1922)

In 1922, Fitzgerald published his second novel, The Beautiful and Damned , the story of the troubled marriage of Anthony and Gloria Patch. The Beautiful and Damned helped to cement Fitzgerald’s status as one of the great chroniclers and satirists of the culture of wealth, extravagance and ambition that emerged during the affluent 1920s — what became known as the Jazz Age. "It was an age of miracles," Fitzgerald wrote, "it was an age of art, it was an age of excess, and it was an age of satire."

'The Great Gatsby' (1925)

The Great Gatsby is considered Fitzgerald's finest work, with its beautiful lyricism, pitch-perfect portrayal of the Jazz Age, and searching critiques of materialism, love and the American Dream. Seeking a change of scenery to spark his creativity, in 1924 Fitzgerald had moved to Valescure, France, to write. Published in 1925, The Great Gatsby is narrated by Nick Carraway, a Midwesterner who moves into the town of West Egg on Long Island, next door to a mansion owned by the wealthy and mysterious Jay Gatsby. The novel follows Nick and Gatsby's strange friendship and Gatsby's pursuit of a married woman named Daisy, ultimately leading to his exposure as a bootlegger and his death.

Although The Great Gatsby was well-received when it was published, it was not until the 1950s and '60s, long after Fitzgerald's death, that it achieved its stature as the definitive portrait of the "Roaring Twenties," as well as one of the greatest American novels ever written.

'Tender Is the Night' (1934)

In 1934, after years of toil, Fitzgerald finally published his fourth novel, Tender is the Night , about an American psychiatrist in Paris, France, and his troubled marriage to a wealthy patient. The book was inspired by his wife Zelda’s struggle with mental illness. Although Tender is the Night was a commercial failure and was initially poorly received due to its chronologically jumbled structure, it has since gained in reputation and is now considered among the great American novels.

'The Love of the Last Tycoon' (unfinished)

Fitzgerald began work on his last novel, The Love of the Last Tycoon , in 1939. He had completed over half the manuscript when he died in 1940.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Short Stories

Beginning in 1920 and continuing throughout the rest of his career, Fitzgerald supported himself financially by writing great numbers of short stories for popular publications such as The Saturday Evening Post and Esquire . Some of his most notable stories include "The Diamond as Big as the Ritz," "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button," "The Camel's Back" and "The Last of the Belles."

Fitzgerald’s Wife Zelda

F. Scott Fitzgerald married Zelda Sayre on April 3, 1920, in New York City. Zelda was Fitzgerald’s muse, and her likeness is prominently featured in his works including This Side of Paradise , The Beautiful and the Damned , The Great Gatsby and Tender Is the Night . Fitzgerald met 18-year-old Zelda, the daughter of an Alabama Supreme Court judge, during his time in the infantry. One week after the publication of Fitzgerald’s first novel, This Side of Paradise , the couple married. They had one child, a daughter named Frances “Scottie” Fitzgerald, born in 1921.

Beginning in the late 1920s, Zelda suffered from mental health issues, and the couple moved back and forth between Delaware and France. In 1930, Zelda suffered a breakdown. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia and treated at the Sheppard Pratt Hospital in Towson, Maryland. That same year was admitted to a mental health clinic in Switzerland. Two years later she was treated at the Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. She spent the remaining years before her death in 1948 in and out of various mental health clinics.

Later Years

After completing his masterpiece, The Great Gatsby , Fitzgerald's life began to unravel. Always a heavy drinker, he progressed steadily into alcoholism and suffered prolonged bouts of writer's block. After two years lost to alcohol and depression, in 1937 Fitzgerald attempted to revive his career as a screenwriter and freelance storywriter in Hollywood, and he achieved modest financial, if not critical, success for his efforts before his death in 1940.

Fitzgerald died of a heart attack on December 21, 1940, at the age of 44, in Hollywood, California. Fitzgerald died believing himself a failure, since none of his works received more than modest commercial or critical success during his lifetime.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Birth Year: 1896

- Birth date: September 24, 1896

- Birth State: Minnesota

- Birth City: St. Paul

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: American short-story writer and novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald is known for his turbulent personal life and his famous novel 'The Great Gatsby.'

- World War I

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Libra

- St. Paul Academy

- Newman School

- Princeton University

- Interesting Facts

- Fitzgerald’s namesake (and second cousin three times removed on his father's side) was Francis Scott Key, who wrote the lyrics to the "Star-Spangled Banner."

- Fitzgerald died believing himself a failure, since none of his works received more than modest commercial or critical success during his lifetime.

- Although 'The Great Gatsby' was well-received when it was published, it was long after Fitzgerald's death that it was regarded as one of the greatest American novels ever written.

- Death Year: 1940

- Death date: December 21, 1940

- Death State: California

- Death City: Hollywood

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: F. Scott Fitzgerald Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/f-scott-fitzgerald

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: July 9, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- What little I've accomplished has been by the most laborious and uphill work, and I wish now I'd never relaxed or looked back—but said at the end of The Great Gatsby: 'I've found my line—from now on this comes first.'

- Often I think writing is a sheer paring away of oneself leaving always something thinner, barer, more meager.

- In a real dark night of the soul, it is always three o'clock in the morning, day after day.

- It was an age of miracles, it was an age of art, it was an age of excess and it was an age of satire.

- Having once found the intensity of art, nothing else that can happen in life can ever again seem as important as the creative process.

- My characters are all Scott Fitzgerald.

- I didn't know till 15 that there was anyone in the world except me, and it cost me plenty.

- I never at any one time saw [Gatsby] clear myself—for he started as one man I knew and then changed into myself—the amalgam was never complete in my mind.

- Show me a hero and I'll write you a tragedy.

- There are no second acts in American lives.

- Riding in a taxi one afternoon between very tall buildings under a mauve and rosy sky; I began to bawl because I had everything I wanted and knew I would never be so happy again.

- I left my capacity for hoping on the little roads that led to Zelda's sanitarium.

- Isn't Hollywood a dump—in the human sense of the word. A hideous town ... full of the human spirit at a new low of debasement.

- I was in love with a whirlwind and I must spin a net big enough to catch it.

Watch Next .css-16toot1:after{background-color:#262626;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous Authors & Writers

A Huge Shakespeare Mystery, Solved

Shakespeare Wrote 3 Tragedies in Turbulent Times

The Mystery of Shakespeare's Life and Death

Was Shakespeare the Real Author of His Plays?

20 Shakespeare Quotes

William Shakespeare

The Ultimate William Shakespeare Study Guide

Suzanne Collins

Alice Munro

Agatha Christie

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

F. Scott Fitzgerald

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 27, 2023 | Original: June 1, 2010

American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940) rose to prominence as a chronicler of the jazz age . Born in St. Paul, Minn., Fitzgerald dropped out of Princeton University to join the U.S. Army. The success of his first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920), made him an instant celebrity. His third novel, The Great Gatsby (1925), was highly regarded, but Tender is the Night (1934) was considered a disappointment.

Struggling with alcoholism and his wife’s mental illness, Fitzgerald attempted to reinvent himself as a screenwriter. He died before completing his final novel, The Last Tycoon (1941), but earned posthumous acclaim as one of America’s most celebrated writers.

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota , Fitzgerald had the good fortune—and the misfortune—to be a writer who summed up an era. The son of an alcoholic failure from Maryland and an adoring, intensely ambitious mother, he grew up acutely conscious of wealth and privilege—and of his family’s exclusion from the social elite. After entering Princeton in 1913, he became a close friend of Edmund Wilson and John Peale Bishop. He spent most of his time writing lyrics for Triangle Club theatrical productions and analyzing how to triumph over the school’s intricate social rituals.

10 Things You May Not Know About F. Scott Fitzgerald

Explore 10 surprising facts about the glamorous and tragic life of one of the 20th century’s most celebrated writers.

How Coffee Fueled Revolutions—and Revolutionary Ideas

From the Ottoman Empire to the American and French Revolutions, coffeehouses have offered a place for (sober) people to discuss new waves of thought.

8 Ways ‘The Great Gatsby’ Captured the Roaring Twenties—and Its Dark Side

From new money to consumer culture to lavish parties, F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel depicted the heyday of the 1920s—and foreshadowed the doom that would follow.

He left Princeton without graduating and used it as the setting for his first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920). It was perfect literary timing. The twenties were beginning to roar, bathtub gin and flaming youth were on everyone’s lips, and the handsome, witty Fitzgerald seemed to be the ideal spokesman for the decade .

With his stunning southern wife, Zelda, he headed for Paris and a mythic career of drinking from hip flasks, dancing until dawn, and jumping into outdoor fountains to end the party. Behind this façade was a writer struggling to make enough money to match his extravagant lifestyle and still produce serious work. His second novel, The Beautiful and the Damned (1922), which recounted an artist’s losing fight with dissipation, was flawed. His next, The Great Gatsby (1925), the story of a gangster’s pursuit of an unattainable lost love, was close to a masterpiece.

The Fitzgeralds’ frenetic ascent to literary fame was soon tinged with tragedy. Scott became an alcoholic and Zelda, jealous of his fame (or in some versions, thwarted by it), collapsed into madness. They crept home in 1931 to an America in the grip of the Great Depression —a land no longer interested in flaming youth except to pillory them for their excesses.

The novel with which he had grappled for years, Tender Is the Night , about a psychiatrist destroyed by his wealthy wife, was published in 1934 to lukewarm reviews and poor sales. Fitzgerald retreated to Hollywood . He made a precarious living as a scriptwriter and struggled to control his alcoholism. Miraculously he found the energy to begin another novel, The Last Tycoon (1941), about a complex gifted movie producer. He had finished about a third of it when he died of a heart attack. Obituaries generally dismissed him.

HISTORY Vault: America the Story of Us

America The Story of Us is an epic 12-hour television event that tells the extraordinary story of how America was invented.

Not until the early 1950s did interest in Fitzgerald revive, and when it did, it became a veritable scholarly industry. A closer look at his life and career reveals a writer with an acute sense of history, an intellectual pessimist who doubts Americans’ ability to survive their infatuation with material success.

At the same time, he conveyed in his best novels and short stories the sense of youthful awe and hope America’s promises created in many people. Few historians have matched the closing lines of The Great Gatsby , when the narrator reflects on how the land must have struck Dutch sailors’ eyes 300 years earlier: “For a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity to wonder.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Movies & TV

- Featured Categories

Sorry, there was a problem.

Image unavailable.

- Sorry, this item is not available in

- Image not available

- To view this video download Flash Player

Biography - F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Great American Dreamer (A&E DVD Archives)

- VHS Tape from $17.80

| Format | DVD |

| Language | English |

| Number Of Discs | 1 |

| UPC | 733961714401 |

| Global Trade Identification Number | 00733961714401 |

Product details

- Product Dimensions : 7.75 x 5.75 x 0.53 inches; 4 ounces

- Media Format : DVD

- ASIN : B0002V7NVG

- Number of discs : 1

- #171,798 in DVD

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 64% 36% 0% 0% 0% 64%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 64% 36% 0% 0% 0% 36%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 64% 36% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 64% 36% 0% 0% 0% 0%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 64% 36% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1896-1940)

Return to barrier breakers.

This grandson of Irish immigrants is ranked among the great American writers of the 20th century. He attended Princeton but left in 1917 to join the Army during World War I. He is most noted for his many novels and short stories that depicted life in the 1920s, the roaring ’20s, the “jazz age.” The Great Gatsby, probably his most noted work, was published in 1925. This decade of extravagance was also lived to the fullest by Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda. Alcoholism, debt and Zelda’s insanity added to the chaos and unhappiness of their lives.

Photo: The American Irish by William V. Shannon

Fitzgerald on the Web:

USC: F.Scott Fitzgerald Centenary A very complete treatment of Fitzgerald including essays and articles, voice and film clips, bibliographies, a Fitzgerald history, and more.

F. Scott Fitzgerald Biography Biography with links to many other Fitzgerald sites.

Books about Fitzgerald:

Tate, Mary Jo and Matthew J. Bruccoli. F. Scott Fitzgerald A to Z. Checkmark Books, 1999.

Additional Fitzgerald Materials:

- Famous Authors Series, F. Scott Fitzgerald

- F. Scott Fitzgerald (A & E Biography)

F.Scott Fitzgerald: A&E Biography Video Guide

- Word Document File

What educators are saying

Description, questions & answers, geekedoutteacher.

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography

Success came swiftly to F. Scott Fitzgerald, and it was the tragedy of his life that after the popularity of his short stories and the praise he merited with The Great Gatsby, he did not mature to carry out the still bigger hooks which he sate in his mind. The causes of his failure have been sensitively analyzed by ARTHUR MIZENBR in his compassionate biography, of which this is the third and final installment. He shows the loyal encouragement which Fitzgerald received from his editor. Max Perkins; his friendships with Hemingway, Edmund W ilson . and John Peale Bishop; and what Zelda and her illness meant to the novelist. The complete book, under the title The Far Side of Paradise, will he published by Houghton Mifflin on February I.

by ARTHUR MIZENER

IN the spring of 1924 Fitzgerald and Zelda Neck suddenly decided that their life in Great Neck was impossible, financially and socially, and that they would go to France and “live on practically nothing a year.” They were escaping, Fitzgerald thought, “from extravagance and clamor and from all the wild extremes among which we had dwelt for five hectic years, from the tradesmen who laid for us and the nurse who bullied us and the couple who kept our house for us and knew us all too well. We were going to the Old World to find a new rhythm for our lives, with a true conviction that we had left our old selves behind forever and with a capital of just over seven thousand dollars.” They would find, as Fitzgerald knew all too well by the time he wrote that, that they could not so easily leave their old selves behind, but for the moment they were full of optimism.

By June they had found a satisfactory place to live at St. Raphael, a large and handsome place with extensive gardens called the Villa Marie. There they settled for the summer. They bought a Renault “a six ehevaux,” Fitzgerald grew a mustache and gradually surrendered to the French barbers’ idea of how his hair ought to be cut, and they soaked in the sun long hours on the beach. For a while t hings went along so well that Fitzgerald wrote Perkins optimistically, “We are idyllicly settled here and the novel is going fine— it ought to be done in a month. . . .”They were planning to go home in the autumn when Gatsby was finished.

But in July there was a serious crisis in their lives. When they had first come to St. Raphaël they had met a French aviator by the name of René Silvé. He was a dark, romantic fellow with a classically handsome profile and curly black hair and he almost immediately fell deeply and openly in love with Zelda. This was a familiar experience for Fitzgerald though he never altogether accustomed himself to it. But when Zelda in her turn began to show an interest in Silve it was another matter. The affair came to a quick and violent climax and, apparently after one or two noisy and undignified scenes set off by Fitzgerald, Rene departed.

The effect of this experience on Fitzgerald was enormous. He had given himself completely to his feelings about Zelda, and if those feelings changed during the course of their marriage, he never imagined that he loved her less or she him. He had never acquired the twenties’ habit of tolerating casual affairs. He remained all his life essentially the boy who was shocked as an undergraduate by his classmates’ casual sex life. Sexual matters were always deadly serious to him, a final commitment to the elaborate structure of personal sentiments he built around anyone he loved, above all around Zelda. His attitude was the attitude of Gatsby toward Daisy, who was for him, after he had taken her, as Zelda was for Fitzgerald, a kind of incarnation. “The emotions of my youth,” he said, “culminated in one emotion,” his feeling for Zelda. It was the damage done to this structure of sentimerits which was most disturbing in the Sllvé a flair.

A month after the crisis he noted that they were “close together” again and in September that the “trouble [was] clearing away.” But long afterwards lie wrote in his Notebooks: “That September 1924 I knew something had happened that could never be repaired.”

By some odd quirk Fitzgerald found that this crisis scarcely a fleeted his ability to work. “It’s been a fair summer,” he wrote Max Perkins. “ I’ve been unhappy but ray work hasn’t suffered from it. J am grown at last.” That last sentence was one he was to repeat half hopefully and half ironically for the rest of his life. In August he had gone on the wagon and begun to get a great deal of good work done on his novel. Early in November he sent it off to Scribner’s, though he was anxiously revising almost up to the day of publication; he was particularly dissatisfied with Chapters VI and VII. “I can’t quite place Daisy’s reaction,” he wrote Perkins. As late as February 18, 1925, he cabled Perkins, HOLD UP GALLEY FORTY FOR BIG CHANGE. This change involved cutting five or six pages from the heart of the quarrel between Gatsby and Tom and rewriting the whole passage.

Meanwhile Zelda had been reading Roderick Hudson and as a result they decided to spend the winter in Rome. Fitzgerald wrote a Post story as quickly as he could after dispatching the novel, in order to provide ready money, and they got away about, the middle of the month. It was not a happy winter. Fitzgerald was in a state of tension after three months of hard work on his novel and there were unresolved difficulties in their relation left over from the previous summer. It was not until after Christmas, when Fitzgerald again went on the wagon, that they were at peace. “Zelda and I,” Fitzgerald wrote John Bishop, “sometimes indulge in terrible four day rows that always start with a drinking party but we’re still enormously in love and about the only truly happily married people I know.” They clung hard to this conviction and made it true for themselves. But they hated Rome. They were always cold and they never could habituate themselves to the petty thievery which they found was a standard part of all relations with landlords, waiters, and taxi drivers in Italy.

In January both Fitzgeralds were sick and they decided to go to Capri to recover. Scott merely had grippe and was soon better but Zelda had a painful attack of colitis which she could not shake off. She was, with periods of temporary improvement, ill for a full year with it.

Fitzgerald himself was full of optimistic talk about starting a new novel, especially to Perkins, whom he always imagined he deceived more than he did about his periods of idleness; he did almost nothing during this spring except to worry about Zelda’s illness and about the reception of Gatsby and, in his anxiety, to drink more heavily than, as he knew, he should. He was behind financially, as he always was after a spell of working on a book; he had borrowed to the limit against the expected royalties on Gatsby and owed Reynolds three stories, only one of which he actually got. written during the spring.

The reception of his novel worried him most; he had committed all his forces in it and he realized that he was now old enough to be judged without qualification for his youth, lie had made a supreme effort with Gatsby; it was for him a test case of whether, in spite of his popularity and the critics’ hesitations about his earlier work, he could develop into a good novelist. As he waited, therefore, for its publication he became more and more nervous, not simply over whether it would be a financial success but over whether it would be considered good by the people whose judgments he respected.

Just before Gatsby was to appear—publication date was April 10 — they decided to return to Paris, driving north from Marseilles in their car (the car, as usual, broke down, at Lyons, and they went the rest of the way by train). April 10 caught them in the south of France and Fitzgerald, Ins anxiety now beyond all reason, cabled Perkins on April 11, less than twenty-four hours after publication, ANY NEWS.

EARLY in May, 1925, the Fitzgeralds reached Paris and there they rented an apartment at 14 rue de Tilsitt for the rest of the year, SALES SITUATION DOUBTFUL, Perkins cabled about Gatsby. EXCELLENT REVIEWS. The sales continued to be, by Fitzgerald’s standards, mediocre, though the reviews were the best he had ever had. By the time Gatsby was published, his debt to Scribner’s was something over $6200; by October the sales were just short of 20,000 copies, a sale slightly below what would have covered this debt. By February a few thousand more copies had been sold and the book was dead.

Fitzgerald had written Bishop, “We want to come back but we want to come back with money saved and so far we haven’t saved any.” He had hoped Gatsby would make him the kind of money he wanted. This was to hope for a miracle, but Fitzgerald yvas an optimistic young man and events had conspired, by producing a series of brilliant successes for him, to convince him that if he did his best he would attain fame and fortune. Such expectations were a part of the pattern he had been brought up on, and if he had outgrown much of his upbringing, he had not lost his conviction that money in large quantities yvas the proper reward of virtue.

He showed his usual mixture of naïveté and insight about this attitude. From the day he announced he would be satisfied with a sale of 20,000 copies of This Side of Paradise he had continued to assume that a novelist should gel very large returns for his work, “If,’ he wrote Perkins about Gatsby , “[my next novel] will support me with no more intervals of trash I’ll go on as a novelist. If not I’m going to quit, come home, go to Hollywood and learn the movie business . . . there’s no point in trying to be an artist if you can’t do your best. ‘ This is a sensible statement — Fitzgerald knew what he could command in Hollywood —except that Fitzgerald’s idea of “support is fantastic.

His writing, even without the “trash,” had supported him more than adequately up to this time. Omitting what he got from everything that might be thought trash and including only his novels and the six best short stories he had so far written, he had averaged between $16,000 and $17,000 a year during his career as a writer (his total income from 1920 to 1924 inclusive was $113,000, a little better than $22,500 a year).

This income ought to have supported them, and Fitzgerald knew it. “I can’t reduce our scale of living,” he continued in his letter to Perkins, “and I can’t stand this financial insecurity. . . . I had my chance back in 1920 to start my life on a sensible scale and lost it and so I’ll have to pay the penalty. . . . Yours in great depression.” Put why did he feel his chance had been lost at the start? A man who intends to be a serious writer in the twentieth century knows that he will be lucky to average a quarter of Fitzgerald’s income over a lifetime; and it is hard to believe anyone could be so subject to extravagance that he would have to sacrifice his whole career to it, especially when he is a man — as Fitzgerald was — powerfully driven to succeed in that career and at the same time tortured — as again Fitzgerald was — by debt.

The answer to these questions lies in Fitzgerald’s imaginative involvement with wealth and in the way its effect was reinforced by the belief in “airing the desire for unadulterated gaiety” which he and Zelda shared. It was difficult enough that Fitzgerald’s imagination drove him to try to live like a man of inherited wealth and that their extravagance and inefficiency always made that life cost more than it needed to. It was worse that, until tragedy struck them, they sought innocently and sincerely for that “orgiastic future” that haunted Gatsby. Fitzgerald’s imagination saw the meaning of their experience. No one will ever improve on Gatsby’s attempt to imitate the life of inherited wealth or his devotion to the “orgiastic future” as a commentary on Fitzgerald’s life. And his imagination could realize and evaluate this attitude because he was committed to it in practice. Ill’s financial dilemma was more than the penalty he paid for having failed to start his life on a sensible scale; it was what he paid for the theme of his finest work.

Fitzgerald later described this summer of 1925 in Paris as one of “1000 parties and no work ”; he was worried about his drinking. It was easy to make a joke of it, as Hemingway, of whom they were beginning to see a great deal, did in The Torrents of Spring: “It was at this point in the story, reader, that Mr. F. Scott Fitzgerald came to our home one afternoon, and after remaining for quite a while suddenly sat down in the fireplace and would not (or was it could not, reader?) get up and let the fire burn something else so as to keep the room warm.” Fitzgerald was beginning to be drunk for periods of a week or ten days and to sober up in places like Brussels without any notion of how he had got there.

But the time was not all spent like that. There was a scheme according to which Fitzgerald and Hemingway and Dean Gauss met once a week for lunch and discussed some serious topic, setting the topic for the next meeting at the end of each session so that they could prepare themselves. Fitzgerald also had the satisfaction of Gatsby’s critical reception. In addition to the handsome reviews, he got many personal letters of great enthusiasm. “It is just four o’clock in the morning,” Deems Taylor wrote him, “and I’ve got to be up at seven, and I’ve just finished The Great Gatsby, and it can’t possibly be as good as I think it is.” Similar letters came from Woollcott and Nathan, from Cabell and Seldes, from Van Wyck Brooks and Paul Rosenfekl. Even better were the letters from Willa Gather and Mrs. Wharton and T. S. Eliot; these overwhelmed the Fitzgerald who stood in awe of distinguished writers: he got the Gausses out of bed at one in the morning to come over and celebrate Willa Gather’s letter. The letter from Mrs. Wharton, with its modesty and its informed comments on the book, meant more to him than all the others, for Mrs. Wharton was a remote and awful figure to ihe young rebels of Paris.

In the fall Owen Davis had made a dramatic version of The Great Gatsby and on February 2, 1926, it opened at the Ambassador Theatre in New York, with James Rennie as Gatsby and Florence Eldridge as Daisy. “. . . as it was something of a sneers d’estime ,” Fitzgerald wrote Harold Ober of the play, “and put in my pocket seventeen or eighteen thousand . . . I should be, and am, well contented.” The play’s success also made possible the sale of Gatsby to the movies, from which Fitzgerald received $15,000 or $20,000 more. These windfalls were welcome, for during 1925 and 1926 his total production was seven short stories and a couple of articles.

DURING this winter of 1925-1926 Fitzgerald devoted himself to getting Hemingway recognized. At least a year earlier he had recommended Hemingway to Perkins’s attention; now he started to work on all his friends. Glenway Wescott has recalled how Fitzgerald urged him to do something to help Hemingway’s career.

He thought T would agree that The Apple of the Eye and The Great Gatshy were rather inflated market values just then. What could I do to help launch Hemingway? Why didn’t I write a laudatory essay on him? With this questioning, Fitzgerald now and then impatiently grasped and shook my elbow. There was something more than ordinary art-admiration about it, but on the other hand it was no mere matter of affection for Hemingway. . . . I was touched and flattered by Fitzgerald’s taking so much for granted. It simply had not occurred to him that unfriendliness or pettiness on my part might inhibit my enthusiasm about the art of a new colleague and rival.

It did not inhibit Fitzgerald, who hastened to write his own laudatory essay, “How to Waste Material,” for The Bookman.

Hemingway had just finished The Torrents of Spring and had completed the first draft of The Sun Also Rises (the final draft was ready in April).

His publishers, Boni & Liveright, were embarrassed by The Torrents of Spring: Sherwood Anderson was one of their most valuable authors, and The Torrents of Spring is a parody of Anderson. Hut they did not want to lose The Sun Also Rises , and Hemingway would be legally free lo take it elsewhere if they rejected The Torrents of Spring. It is hardly surprising that Boni & Liveright were convinced Hemingway deliberately wrote The Torrents of Spring as part of a plot, devised by him and Fitzgerald, to free him from them. In the end, however, they decided to reject Hemingway’s parody.

Fitzgerald had certainly hoped the matter would work out this way, but there is no reason to suppose Hemingway wrote ihe book for this purpose. “[Ernest’s] book,” Fitzgerald wrote Perkins, “is almost a vicious parody on Anderson. You see I agree with Ernest that Anderson’s Ias1 two books have let even body down who believed in him I think they’re cheap, faked, obscurantic and awful.”

This was Hemingway’s motive. “I have known all along,” he wrote Fitzgerald, “that they could not and would not be able to publish it as it makes a bum out of their present ace and best seller Anderson. Now in 10th printing. I did not, however, have that in mind in any way when I wrote it.” When Boni & Liveright finally rejected The Torrents of Spring , Hemingway turned down offers from several other publishers and signed with Scribner’s.

Though the feeling between them later became less friendly, Fitzgerald never lost his deep admiration for Hemingway’s talent; he paid generous tribute to it in “Handle with Care”: . . a third contemporary had been an artistic conscience to me—I had not imitated his infectious style, because my own style, such as it is, was formed before he published anything, but there was an awful pull toward him when I was on a spot.” As soon as Hemingway had signed with Scribner’s Fitzgerald began to fuss over his work like a maiden aunt. He was particularly worried about The San Also Rises , and Hemingway took to teasing him about his own plans for The World’s Fair.

The Fitzgeralds came back lo America in December, 1926, with the intention of settling down and living a more orderly life, so they started off bv visiting Fitzgerald’s parents, who were now living in Washington, and Zelda’s family in Montgomery. Early in the new year, however, Fitzgerald got a chance to fulfill his old threal to go to Hollywood and learn the movie business; John Considine of United Artists asked him to come out to do a “fine modern college story for Constance Talmadge” (“one of the hectic flapper comedies, in which Constance Talmadge has specialized for years,” the newspapers called it). After some jockeying Fitzgerald agreed to go for $6500 down and $8500 on the acceptance of the story, for they needed the money too much lo refuse the offer even if il was likely to interrupt their program of orderly living.

There was a whirl of parties, night clubs, and practical jokes. At a tea of Lois Moran’s Fitzgerald made himself what one gossip columnist described as “conspicuous by |his] presence” by collecting watches and jewelry from the guests and boiling the whole collection in a couple of cans of tomato soup on the kitchen stove.

When Fitzgerald finally completed his story for Constance Talmadge it was rejected. “At that time,” he said years later, “I had been generally acknowledged for several years as the top American writer both seriously and, as far as prices went, popularly. I . . . was confident to the point of conceit. Hollywood made a big fuss over us and the ladies all looked very beautiful to a man of thirly. I honestly believed that with no effort on my part I was a sort of magician with words. . . . Total result — a great time and no work. I was to be paid only a small amount unless they made my picture — they didn’t.”

As soon as the script was finished the Fitzgeralds left Hollywood. It was reported that they stacked all the furniture in the center of their room at the Ambassador, put their unpaid bills on top of it, and departed; when they got on the train they crawled on tHeir hands and knees the length of the car to reach their compartment, to escape inconspicuously. . . . BOOTLEGGERS GONE OUT OF BUSINESS COTTON CLUB CLOSED ALL FLAGS AT HALF MAST . . . BOTTLES OF LOVE TO YOU BOTH, Lois Moran wired them.

THE orderly life, which had been in abeyance during these months, was now revived. With the help of Fitzgerald’s college friend, John Biggs, they found a beautiful old Greek-revival mansion outside Wilmington called Ellerslie. Fitzgerald settled down to an honest struggle to complete his new novel. Me was realistic enough to warn Perkins against any publicity about it, but wired him: EXPECT TO DELIVER NOVEL TO LIBERTY IN JUNE. They made an effort to become a part of the social life in Wilmington and, as they always did when they tried, they charmed everyone and were soon firmly established there.

But Ellerslie did not work out very well. Under the stress of the accumulated disorder of their lives their personal relations were deteriorating into what Fitzgerald later called an “organized cat and dog fight.” Their social success in Wilmington was the signal for that destructive impulse which was the product of Fitzgerald’s unhappiness to assert itself, and he began to be rude to people.

As a part of their struggle for tranquillity they had their parents come for visits. Zelda spent two busy months building a marvelous dollhouse for Scottie, their little girl, now six years: old; she made a set of charming lampshades decorated with découpages of all the houses they had ever lived in; she painted the garden furniture with decorative and ingenious maps of France. They celebrated Christmas, 1927, with an elaborate tree. Fitzgerald put himself on a drinking schedule, though there were occasions like the one where, having made a friend a cocktail and asserted he was not drinking, he idly poured himself a glass of gin and drank it off and then said with evident surprise: “Did I just drink a glass of gin? — I believe 1 did.

He had done a good deal of work on his book during the summer of 1927. He was full of optimism and talked confidently of how what he was now calling The World’s Fair would “before so very long begin to appear in Liberty. The work, however, petered out during the fall, and when Perkins inquired in February, Fitzgerald wrote in despair: “Novel not yet finished. Christ I wish it were!” Work came to a complete stop when they decided to spend tin1 summer of 1928 abroad.

Their immediate reason for going was Zelda s dancing. She had determined suddenly to become a ballet dancer and, almost from one day to the next, had taken to dancing with an intensity which, as one of their friends said, was like the dancing madness of the middle ages. She began to go to Philadelphia two or three times a week to study with Catherine Littlefield and would come home to practice several hours a day in the living room, which was cleared for the purpose. There was something peculiar about this ext rente concentration on dancing and Fitzgerald afterwards said that looking back he thought he could trace evidences of her insanity at least as early as 1927, when she had begun to show a number of disturbing signs, such as going through long periods of unbroken silence.

They arrived in Paris in a haze of alcohol, without reservations or plans. A friend who met them finally got them a place to stay— it was not easy in Paris the summer of 1928. Scottic, who was excited by Paris, kept pointing out the sights as they drove through the city but neither of them was capable of responding. The summer was like that. Twice Fitzgerald wound up in jail. Zelda was starting to take lessons with Egarova and they quarreled over her dancing, for there was some drive in Fitzgerald to destroy her concentration. He appeared unable to endure Zelda s successful - if neurotic — display of will when he fell that selfindulgence and dissipation were ruining him. “It is the loose-ends,” as Zelda said long after, with which men hang themselves.”

Just before they returned to America they had a bitter quarrel during which unbelievable charges were made by both of them. This quarrel led to a break between them which was never really repaired. Late in September, “in a blaze,” as Fitzgerald said, “of work & liquor” (he was trying to finish up “The Captured Shadow for the Post ), they came home to Ellerslie. “Thirty-two years old,” Fitzgerald wrote in his Ledger, “and sore as hell about it.” They were broke, though Fitzgerald’s incomeincluding a $6000 advance on his novel — had been $29,737 in 1927 and was running close to that in 1928.

Back at Ellerslie Fitzgerald tried to settle down to his book. In November he wrote Perkins that he was going to send him two chapters a month of the final version until, by February, he would have sent it all. “I think this will help me get it straight in my own mind, he said; “ —I’ve been alone with it too long.” The November chapters were sent, and probably the December ones; but that w as all. Four years later he asked Perkins to ret urn “that discarded beginning that I gave you. . . .”

In the spring of 1929 their two-year lease on Ellerslie ended and, writing the whole thing off ns a bad investment, they set off for Europe once more. Fitzgerald explained to Perkins that he could not work in Delaware but that, once abroad, he would finish the novel by October.

He became more difficult as he became more unhappy over his inability to get control of himself. He understood their trouble, but this knowledge only made his predicament more painful to him. He fancied that people were beginning to avoid him and that there was even in Hemingway’s attitude a certain coldness. He took to brooding darkly over compliments until he had persuaded himself they were ironic and insulting. On the strength of a remark of Gertrude Stein’s comparing “his flame” with Hemingway’s, he wrote Hemingway a belligerent letter about his air of superiority. Hemingway replied with painstaking care.

Fitzgerald’s attitude throughout his quarrels with Hemingway shows how extensive the breakdown in his discipline was and how embittered he had become. In his suffering he struck out, blindly and unreasonably, at the people and things that mattered most to him.

IT WAS a heartbreaking time for Zelda too; she had been encouraged about her dancing that summer and she had reached the time when she ought to have been getting some professional offers. It was the moment of success or failure. All winter she kept hoping the people who came to the studio were emissaries of Diaghilev ready to offer her at least, bit parts in one of his ballets; and each time they turned out to be people from the Folies Rergeres “who thought they might make her into an American shimmy dancer.” In February, “because it was a trying winter and to forget bad times,” they took a sight-seeing trip to Algiers.

When they got back to Paris from their trip, Zelda, lighting off the knowledge of failure, went back to dancing harder than ever. She appeared frighteningly tensed up. Early in April, at a large luncheon at their apartment in the rue Pergalese, she became so nervous for fear she would be late for her dancing lesson that an old friend offered, in the middle of luncheon, to take her to it. In the cab she was badly overwrought, shook uncontrollably, and tried to change into her ballet costume as they drove along. When they got into a traffic jam, she leapt out and started running. This episode was so disturbing that Zelda was persuaded to stop her lessons for a rest. Rut she soon returned to them, and, on April 23, she broke down completely.

At first in her illness she would not see Fitzgerald at all, carrying over into her hallucinations many of the fantastic suspicions which had been a growing pari of their quarrels from as far back as the fall of 1928. This suspicion of him gradually faded out. But her general condition did not improve; there were long periods of madness interspersed with periods of relative lucidity throughout the summer. During the calmer times she painted a little and wrote a great deal, producing a libretto for a ballet and three short stories. There is something at once pathetic and frightening about the persistence of her will to produce during I his period.

When Zelda did not improve, Fitzgerald decided to take her to Switzerland, where, he was told, the finest psychiatric care in Europe was to be had. They went to Montreux, where a number of specialists were called in; they agreed on the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Fitzgerald was told that out of every four such cases one made a complete recovery, and two made partial ones. But there followed a summer and fall of dreadful anxiety; with no letup except for a single hour in September, the terrible hallucinations and the violent eczema which characterized Zelda s case continued through 1930, and Fitzgerald remembered with special horror “that Christmas in Switzerland” when Scottie came on from Paris and he tried to make it gay for her. There is a faint echo of what Zelda must have gone through in her description of Alabama’s delirium in Save Me the Waltz.

Apart from fortnightly trips to see Scottie, who had been left in Paris with a governess in order that her education might not be interrupted, he stayed close to Zelda in Switzerland most of the time. “[Nervous trouble],” said Zelda with that simple courage which characterized her attitude toward her illness, “is worse always on the people who care than on the person who’s ill.” It was Fitzgerald’s nature to feel deeply the suffering of the person he most loved. Moreover, despite the doctors’ assurances that Zelda’s trouble went back a long way and that nothing he could have done would have prevented it, Fitzgerald had a deep feeling of guilt about it. He knew how much he was to blame for the irregularity of their lives; he knew what he had contributed to that “complete and never entirely renewed break of confidence” which had occurred in Paris in 1928; he knew—however unreasonable Zelda may have been about her dancing—how much harder he had made it for her. When the doctors told him that he “must not drink anything, not even wine, for a year, because drinking in the past was one of the things that haunted [Zelda] in her delirium, they were the voice of his own conscience.

Late in January, 1931, Zelda got well enough to spend whole days out skiing, and Fitzgerald’s hopes that she was “almost well — really well” rose. She continued to improve until by spring she was able to travel a little. Toward the end of ihe summer they ventured farther, to Munich and Vienna. By September Zelda was well enough to go home, and they motored — “that is, we sat nervously in our six horse-power Renault” — to Paris and sailed for America, where they went to Montgomery with some idea of settling down quietly there. For a month or so they played golf and tennis and house-hunted, and Fitzgerald, as on all such homely occasions, found life dull.

When Metro-Goklwyn-Mayer asked him to do a revision on a script of Katherine Brush’s RedHeaded Woman, he was glad to go to Hollywood.

While Fitzgerald was in Hollywood, Judge Sayre died. At first Zelda seemed to take the shock well, but her father was important to her and his death was bound to affect her gravely. The first sign of trouble was an attack of asthma. Fitzgerald took her to St. Petersburg hoping the climate might help her, but she grew worse, and then, at the end of January, she broke down mentally again. This breakdown was a stunning blow to them. They had fought hard to believe Zelda was really well and their personal relations had recently been much happier. By this time he had read enough about schizophrenia to know that each attack made a final recovery less likely. He was a long way from giving up, but he was frightened and depressed.

He took Zelda to Baltimore for treatment and returned to Montgomery to await word from the doctors. A little more than a month later — it was written in six weeks, mostly while she was in the hospital — Zelda sent Perkins the manuscript ot her novel, Save Me the Waltz (“we danced a Wiener waltz, and just simply swop’ around”). Like everything else she wrote, it was a brilliant piece of amateur work written at remarkable and disturbing speed. A suspicion of Scott — the result of that fierce desire to succeed on her own and outdo him which haunted their devotion — made her send the book directly to Perkins.

Zelda did not improve, and that spring Fitzgerald moved himself and Scottie from Montgomery to Baltimore. Here they settled down as near Zelda as possible.

ALL this disappointment and suflering had its effect on Fitzgerald. His drinking increased, and it made him subject to fits of nervous temper and depression and less capable of providing the regulai life Zelda needed. It also affected his work, for in spite of his attempts to persuade himself then, and later, that he could work only with the help of gin. be was as inefficient as most people when he had been drinking.

Yet in spite of these handicaps, he managed to make a home and a life for the three of them in the intervals when Zelda was well enough to leave the sanitarium. He was fighting to save Zelda and to save himself, for the two things seemed to him inextricable. Over and above his love for Zelda and his desire to save her, he had invested too much ot his emotional capital in the relation he and Zelda had built together to be anything but an emotional bankrupt if that relation failed. “I should, said one of the people who knew him best at this time, “have felt he was much more to blame [about Zelda] if he had grown a little bored by, or indiflerent to, her tragedy . . . than if he had grappled with it daily, and failed, as he did. No one could watch that struggle and not be convinced of the reality of his concern and suffering. He was, of course, a man in conflict with two terrible demons, — insanity and drink . . . but he appeared to be giving blow for blow; there was hope in him and Hashes of confidence.

It was a dogged fight, with many lost battles, a last stand of the Fitzgerald who had believed that “Life is something you dominated if you were any good.” In the end he lost both his objectives, and he knew for all his “flashes of confidence” how desperate the battle was.

He got down at last to steady work on his novel, Tender Is the Sight. The evidence suggests that the version of the novel he had projected about 1929 and had got some work done on was now diastically revised again.

He wrote Perkins in January, 1932. “I am replanning [my novel] to include what’s good in what I have, adding 41,000 new words and publishing. Don’t tell Ernest or anyone — let them think what they want.” That supercilious Hemingway ghost who spent all his time thinking Fitzgerald would never write seriously again was a projection of his own conscience with which he haunted himself, it was one of his sharpest spurs. “Am going on the water wagon from the first of February to the first of April,” he wrote Perkins a little later, “but don’t, tell Ernest because he has long convinced himself that I am an incurable alcoholic. . . .” Like this one, many of Fitzgerald’s fantasies began to get nearer the surface at this time and to threaten to intrude on his daily life.

But his book was going so well that in momentary enthusiasm he wired Perkins: THINK NOVEL CAN SAFELY HE PLACED ON YOUlt LIST FOR SPRING. Zelda’s third breakdown ended this hope.

In spite of illness and alcohol, Fitzgerald got the manuscript of Doctor Diver s Holiday to Perkins the following October. Fie distrusted a title with the word doctor in it because he thought it might frighten readers off, but he did not think of Tender Is the Sight until just before 1 he novel began to run in Scribner’s Magazine , and even then its adoption was delayed because Perkins thought it had no connection with the story. But Perkins was enthusiastic about the book.

By now serious financial difficulties were beginning to accumulate for him. With his decline in popularity as the proletarian decade got under way and with his concentration on the writing of Tender Is the Night . he turned out only nine stories in 1932 and 1933 — six in the first year and three in the second. As t he depression became more serious, the prices for Ids Post stories began to fall from the old $4000 to $3300 or $3000 and, occasionally, to $2500. His book royalties in these years totaled $50. The result was an income less than hall what it had been in 1931, and this includes over $5000 iu advances on Tender Is the Night. From this tune until he went to Hollywood in 1937 Fitzgerald continued to fall behind financially .

Unwiliing to give up hope, Fitzgerald was still trying to help Zelda, and whenever he could would take her from the sanitarium for long walks. One warm spring day, as they were silting under the trees. Zelda, hearing a train approaching on a nearby branch line, leapt up and started to run toward it to throw herself under it. Fitzgerald caught her just short of the embankment as the train passed. With the increase of such dangerous impulses they tried, on the advice of the doctors, a sanitarium in upstate New York. But Zelda only grew worse there and in May had to be brought back to Baltimore in a catatonic state.

For the next six years, except for brief periods of relative stability, she was confined to various hospitals and gradually, along with his other hopes, Fitzgerald began to give up his belief in herevenlual recovery. “I left my capacity for hoping,” he said, “on the little roads that led to Zelda’s sanitarium.” Little by little he evolved an altitude which would protect hint against the terrible temptation to believe in her reasonableness and to try to persuade her to be well. “Zelda,” he kept telling himself, “is a case, not a person.” For the rest of his life, however, he kept having to light this battle over again, for the psychological wrench involved in writing off the investment of love and happiness and effort they had both made in their relation was more than he could ever quite manage.

Through all this, he was struggling with the proofs of Tender Is the Night Sick — he was more and more in the hospital now for two or three days at a stretch getting himself straightened out - and tired as he was, the proofs seemed to him endless. But he finally fought his way through them and Tender Is the Night was published on April T2, 1934.

Fitzgerald waited anxiously for the rex lews of Tender Is the Night. It was not just a matter of being taken serimtslv or even of making monex now. It was a question of his ability to believe in himself. When the character of the reviews and the sales — Tender fa the A ight sold around l.‘h000 copies — became clear, his morale dropped lower than it ever had before. This was the biggest battle he had lost yet.

He was working now in a night mare of discouragement about his writing and of despair about Zelda — she grew worse rather than belter all year and of worry over finances. In June he spent what he called “a crazv week in New York" and collapsed when he got home, lie was in the hospital for some lime, got out in July, and then had to go back again, lie was beginning to find himself in dangerous financial st rails. “The bills really begin,” he noted in his Ledger in Julx : in September it was ‘finances now serious’ and in November “l)ebt bad.”

EVER since he had got into financial straits, Fitzgerald had thought of trying to get to Hollywood again. During 1936 he had worked to find a job there, and in August he got an offer to go out and do a story “of adolescents around seventeen,”

The contract was to be for four weeks at $1500. Because of a bad shoulder he had to refuse, but by the following April he had another feeler. In June, 1937, he arrangement was completed. He was to go In MGM for six months at $1000 a week with an opt ion for twelve mont hs more at $1250. This option was in due course picked up. Since one of his main motives for going to Hollywood — though not the only one — was to pay his debts, the first thing he did was to make an arrangement with his agent, Harold Ober, to do so. His plan was to deposit his salary with Ober, who would then give him $400 a month, to support himself, keep Scottie in school and Zelda in the sanitarium. Pile rest was to be set aside for taxes and pax mtails against his debts to Ober and Perkins and, later, Scribner’s. These debts amounted, according to his own estimate, to something like $30,000 at the time. He maintained substantially this arrangement until his debts were paid.

But though the clearing of these “terrible debts” was very important to him, he also felt something of the old fascination of Hollywood and the old desire to conquer it. It was a place that he had never got the best of. It was this feeling of excitement that stayed with him, so that when he was making jottings for The Last Tycoon he reminded himself of “my own fears when I landed in Los Angeles with the feeling of new worlds to conquer in 1937. . . .” And it was with this ambition to conquer that he tackled his job. He spent much of his spare time having pictures run off for him and studying other writers’ scripts, and he kept a file of noles on the pictures lie had seen. As late as November, when he had finished a revision of A Yank at Oxford and was hard at work on Three Comradea , he called himself “a semi-amateur” at movie construction (“though I won’t be that much longer”), lie was determined, this time, to do a good job, to give everything he had. For a while he kept completely sober, and as long as lie was under contract to MGM he only went on an occasional bust.

In April, 1938, they ran into censorship trouble over Infidelity and, with most of a good and difficult script already done, Fitzgerald had to drop it. It was never revived. For the duration of his contract with MGM he worked on The Women and Madame Curie. Because of his disappoint ment wit h his movie work he began to think of his writing again.

He had not got a screen credit for his work on The Women and he had been replaced on Madame Cane after two months. ‘Pints, as he came to the end of his contract, he had not had a credit since Three Comradea and the contract was not renewed.

The summer of 1939 was for Fitzgerald a struggle against illness and financial troubles. He was unable to get a job in pictures until September, when he worked — unsuccessfully for a week at United Artists on Raffles. “I am so tired of being old and sick,” he wrote a friend it bout the outbreak of the war; — would much rather be a scared young man peering out over a hunk of concrete or mud toward something I hated. . . .”

But toward the end of the month he got himself together and went to work on the novel for which he had been planning and making notes for more than a year. Collier’s had shown real interest in the idea and had agreed to pay him $25,000 or $30,000 for the serial rights if he would submit fifteen thousand words that they liked.

The possibility that he might be financially able to devote six months to a novel and be released from the drudgery of dull movies was wonderful to him, and his mind began to work in the old way to focus and arrange the host of impressions of Hollywood which had, since 1932, been gathering in the back of his mind like the elements of a myth. The hundreds of pages of notes for The Last Tycoon , from which Edmund Wilson made a selection for Ins edition of the book, constitute an inexhaustibly perceptive portrait of a place and time which is far richer than the relativelv small portion of these notes Fitzgerald got organized in the six chapters of the novel he completed before he died. They show how intact his talent was and how much it had matured, for all his physical and nervous exhaustion.

He went to work with all the energy he could muster. By the end of November he had completed six thousand words — probably the first chapter — and asked Eittauer for a decision. It was very little to go on and Eittauer wanted to DEFER VERDICT UNTIL FURTHER DEVELOPMENT OF STORY. But Fitzgerald was in his usual financial difficulties he had borrowed money in order to send his daughter to Vassar. He cut off negotiations with Collier’s abruptly and wired Perkins: PLEASE RUSH COPY AIR MAIL TO SATURDAY EVENING POST. . . . I GUESS THERE ARE NO GREAT MAGAZINE EDITORS LEFT. . . . But like Collier’s the Post wanted more to go on, and there was no more, so that nothing came of this plan either.

He worked on the novel as steadily as he could until April, when he took another movie job. By that time he had worked out in some detail nearly all of the six chapters which were completed at his deat h.

He finished the movie script, called Cosmopolitan, at the end of June: there was a month and a half of revising and dickering to see if Shirley Temple could be interested in the part of Victoria (the Honoris of the story), and then the script was shelved. Except for some minor doctoring jobs, this was the last picture Fitzgerald did.

Though Fitzgerald had been working steadily through the summer, he had not been well, and he began drinking again as soon as Cosmopolitan was completed. He was far from well even wlien be was not drinking. With ihe money he collected from his picture work in September and October, he was able to devote himself to his novel and he determined to finish it.

Late in November he had a serious heart attack — how serious is shown by the fact that almost for the first time in his life he belittled instead of exaggerating an illness. “I’m still in bed but managing to write and feeling a good deal better. It was a regular heart attack this time and I will simply have to take better care of myself,” he wrote Scoltie. Me stopped drinking altogether, and, spending most of his time in bed, got down to hard work on The Last Tycoon. He knew exactly what he wanted to do: “I want to write scenes that are frightening and inimitable. I don’t want to be as intelligible to my contemporaries as Ernest who as Gertrude Stein said, is bound for the Museums. I am sure I am far enough ahead to have some small immortality if I can keep well.” Much of the actual writing of the book must have been done at this time.

But whether he could have fulfilled the promise of this beginning we can never be sure, Like so much else in bis life, his heroic effort to finish his last novel canto too late; and the luck which might have kept him alive until he had finished was not with him. He had predicted to Perkins in the middle of December that he could complete a first drafl by January 15, and at the rate he was going he might have done so: on December 20 he completed the first episode of Chapter VI. The next day he had a second, fatal heart attack.

Not long before he died Fitzgerald scribbled on an odd scrap of paper a few imperfect lines for a poem he never got time to finish. As if conscious to the last of a need to tell his story, he was writing his own epitaph.

The novel he wanted so desperately to complete was unfinished: the reputation in which he found his justification was only a faint echo (all his life he saved clippings about himself; at the end there were only a few scattered sentences from The Hollywood Reporter to be clipped). And be was, be knew, dy ing. Eike Gat shy, who felt that if Daisy had loved Tom at all “it was just personal.” Fitzgerald loved reputation, the public acknowledgment of genuine achievement, with the impersonal magnanimity of a Renaissance prince. His aim was to give that chaos in his head shape in his books and to see the knowledge that he had done so reflected back to him from the world. He died believing he had failed.

Now we know belter, and il is one of the final ironies of Fitzgerald’s career that lie did not live to enjoy our knowledge. A decade after Fitzgerald’s death, more of his work is in print than at any time during his life, and his reputation as a serious novelist is secure.

( The End )

- World History

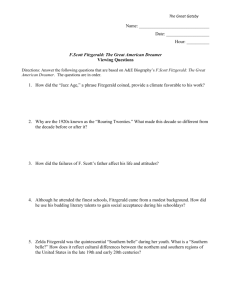

Discussion Questions (from A&E Biography education links) How

Related documents.

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

COMMENTS

This is the A&E biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald, edited slightly to cut out the reveal of the ending of The Great Gatsby.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald were hailed king and Queen of what Age?, Fitzgerald was named after a distant relative, Francis Scott Key, who wrote what famous song?, What talent helped Fitzgerald fit in at prep school? and more.

Francis Scott Fitzgerald was born on September 24, 1896, in St. Paul, Minnesota. Fitzgerald's namesake (and second cousin three times removed on his father's side) was Francis Scott Key , who ...

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 - December 21, 1940), widely known simply as Scott Fitzgerald, [1] was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age, a term he popularized in his short story collection Tales of the Jazz Age.During his lifetime, he published four novels, four story ...

It was Fitzgerald's 1st successful novel. How did Ernest Hemmingway connect to F. Scott Fitzgerald's life? Fitzgerald and Hemmingway were rivals, drinking buddies, and friends; however, they often were at odds with each other and proved to be great competitors. Who was the woman in F. Scott Fitzgerald's life who burned to death at an insane ...

Fitzgerald Biography VIEWING GUIDE 2-page viewing guide for A&E's "The Great American Dreamer" biography video with questions designed to prepare students for reading ANSWER KEY INCLUDED! ... -- F. Scott Fitzgerald-- ...

F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896‑1940) was an American writer, whose books helped defined the Jazz Age. He is best known for his novel "The Great Gatsby" (1925), considered a masterpiece. He was ...

A & E Biographies takes a candid look at this multi-faceted man in the well-researched video presentation of F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Great American Dreamer. Beginning with a history on the roaring twenties, the prime time of Fitzgerald's life and work, this documentary span the era that influenced the man and gives a detailed account of the ...

Quiz yourself with questions and answers for F. Scott Fitzgerald A&E Biography Quiz REVIEW, so you can be ready for test day. Explore quizzes and practice tests created by teachers and students or create one from your course material.

A & E Biography with Marilyn Monroe, Leonardo Da Vinci, Nelson Rockefeller, Ronald Reagan, F. Scott Fitzgerald, George C. patton, Jackie Onassis, Henry VIII, Shirley ...

Description. This is a viewing guide for students to complete while watching the A&E Biography video of F. Scott Fitzgerald. There are also discussion questions to use after watching the documentary. Use this as a pre-reading to The Great Gatsby or when teaching the 1920s. An answer key for the viewing guide is included.

F. Scott Fitzgerald Biography Biography with links to many other Fitzgerald sites. Books about Fitzgerald: Ring, Frances Kroll. Against the Current: As I Remember F. Scott Fitzgerald. Creative Arts Book Co.,1985. Tate, Mary Jo and Matthew J. Bruccoli. F. Scott Fitzgerald A to Z. Checkmark Books, 1999. Additional Fitzgerald Materials: Video tapes:

As students watch A&E's Fitzgerald biography, they can take notes on the fill-in-the-blank worksheet. These notes can then be used to do a comparison between Fitzgerald's life and his works, including The Great Gatsby or Winter Dreams. ... F.Scott Fitzgerald: A&E Biography Video Guide. Rated 4.77 out of 5, based on 23 reviews ...

F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography. With his good looks, his swift success, his love of parties, and his incredible spending. F. Scott Fitzgerald was the personification of "the jazz age. After ...

What ended up disappointing him about this venture? •he went to bootcamp. •the war ended right before he could fight. What was the first name of Fitzgerald's wife? •zelda. Describe the Fitzgerald's marriage. • very alcoholic. • chaotic. Name Fitzgerald's friend/drinking buddy who became his literary rival.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: Facts and Overview. F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940) is thought of as one of the great American novelists. He wrote primarily during the 1920s, and he has brought the Jazz Age ...

Legacy. Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 - December 21, 1940) was an American author of novels and short stories, whose works are the paradigmatic writings of the Jazz Age. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century. Fitzgerald is considered a member of the "Lost Generation" of the 1920s.

Late in January, 1931, Zelda got well enough to spend whole days out skiing, and Fitzgerald's hopes that she was "almost well — really well" rose. She continued to improve until by spring ...

Wolfsheirn's characterization as Jewish, yet the title of his office being "the swastika Holding Company" (171) Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like When, F. Scott Fitzgerald was just a teenager, he realized that he had a talent for writing. He decided to use his talent to write plays, which he produced at his school.

Scott Lawrence Fitzgerald (born November 16, 1963) is an American politician and former newspaper publisher. A Republican, he represents Wisconsin's 5th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives.The district includes many of Milwaukee's northern and western suburbs, such as Waukesha, West Bend, Brookfield, and Mequon.He represented the 13th district in the Wisconsin State ...

10. How did alcoholism play a role in the destruction of Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald's lives? Discussion Questions (from A&E Biography education links) 1. How did the failures of F. Scott's father affect his life and attitudes? 2. Why are the 1920s known as the "Roaring Twenties.". What made this decade so different from the decade.

Fitzgerald and Hemmingway were rivals, drinking buddies, and friends; however, they often were at odds with each other and proved to be great competitors. Who was the woman in F. Scott Fitzgerald's life who burned to death at an insane asylum? His wife, Zelda. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Why is Princeton ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like What was F. Scott Fitzgerald's full name, and who was he named after?, What state was he born in?, Why didn't he fit in at his school? and more. ... A&E Biography - F. Scott Fitzgerald. 20 terms. Celeste_2015_ Preview. Fitzgerald Biography Video Questions. 32 terms. griffithk221 ...