True Self Vs False Self

From brokenness to wholeness healing through faith, hope, and love.

Identity and the relentless search for self in any paradigm has been a pertinent part of society since Adam and Eve chose to gain the wisdom that broke the sanctity of their child like innocence (Gen 3, NIV; Bible Gateway, n.d.b ¶1). As such, I know I for one, seek understanding in which I can conceptualise what “the self” means. From secular to spiritual philosophies, “the self” has been separated and conceptualized through its various parts for centuries. Though there is a vast array of ideas that both complement and contradict each other, one thing is certain: if my parts remain unknown to me, un- integrated as it were, I live a life in chaos and rigidity (Siegel, 2010, p. xxvi). There is a sense of uneasiness, where the “true self” and the “false self” are at war with one another (Rohr, 2013, pp. 2-3). This sense is a reality for many, including those who seek the assistance of counselling. In order to find their inner harmony, others come knowing that we have first found ours (Siegel, 2010, p. xxvii).

Therefore, when I, as a counsellor, take the time to conceptualise “the self” and its parts, I can come to integration. A sense of harmony through faith, hope, and love that encompasses the soul by the spirit and through the body, allows my “true self” to be the most dominate aspect of who I am, and as such provides a healing space for others (Siegel, 2010, p. xxvii; Marshall, 2001, p. 234; Alexander, 2007, p.22; Rohr, 2013, pp. 184 – 186; 187; 1 John 3, NIV; 1 Cor 13:13, NIV; 1 Thess 5:8, NIV).

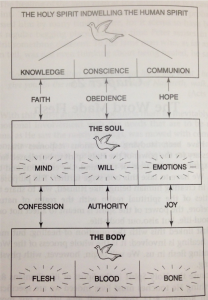

This essay will expand on the abovementioned notions as they relate to Marshall’s (2001) model of spirit, soul, and body (see Appendix One). With a focus on understanding mind, will, and emotions, I hope to offer a self-exploratory theory of what it means to be mindfully present with my “true self” in order to provide space for others to conceptualise their own identity.

UNDERSTANDING WHOLENESS: THE “TRUE SELF”

Understanding “the self” first comes in exploring the definition of what it means to be in one’s “true self”. Personally, I had no concept of my true sense of self until the day I found myself torn in pain, screaming to the heavens in a child-like form “I want to go home”. At the time, I had no idea it was my spirit crying out for my soul to awaken and to return to who I am in Christ: He who is my source and my destiny (Benner, 2012, p.18). Without a true relationship with God (Benner, 2012, p. 83), a sense of identity was unachievable: I was oblivious that I was un-integrated (see “neural integration” Siegel, 2010, p. xii; Siegel, 2012, p. 15; Siegel, 2007, pp. 39-41). In an integrated state the “true self” comprises three sovereign dimensions of spirit, soul, and body, able to distinguish between “me and not me” (Marshall, 2001, p. 234; Abram, 2007, p. 295; Alexander, 2007, p. 19). Further, the “true self” is at peace, willing to meet God in the “depths of [the] soul” (Benner, 2015, p. 101) in order for transformation from the inside out (Bible Gateway, n.d.a, ¶Matthew Henry Commentary; Benner, 2015, p. 101; Alexander, 2007, p. 21).

Yet, how is it that I come to meet God within the depths of my soul? To transform? As abovementioned, Marshall (2001) provides a working model (see Appendix One) which incorporates the notion that we are “thinking, feeling, willing beings” (soul: see also Benner, 2012, pp. 121 -122) in which we relate to both our internal (spirit: see also Benner, 2012, p.22) and external (body: see also Benner, 2012, p. 89) worlds (p. 9). Moreover, where each of these three sovereign dimensions work together in integration to create the “true self” in which faith, hope, and love (1 Cor 13, NIV; Eph 4:4-6, NIV; Col 1:5, NIV; 1 Thess 5:23, NIV; 1 Thess 5:8, NIV) encompass the soul by the spirit and through the body (Marshall, 2011, p. 234; Rohr, 2015, pp. 16-17). However, knowledge of this concept, while holding the basis of transformation or change, is not enough. Quite often it takes an existential crisis of identity in order to accept the invitation to confront the feeling of being “false” (Benner, 2015, p. 51).

Through my own personal experience of disorganised attachments based in trauma and regressed dependence, in which I was unable to become a “person in [my] own right” (Watts, 2009, p. 149), I am able to ascertain the understanding of that which was, and can still be my “false self”. Highly defensive and reactive I sought attachments in seemingly innocent indulgences (Abram, 2007, p. 283; Benner, 2015, p. 75) such as possession, lust, and control. I created a role for myself, acting only in present moments as who others wanted and expected me to be (Alexander, 2007, pp. 121 & 123); suppressing a past filled with unresolved confusion and abandonment and ignoring what I felt, became my identity (Benner, 2015, pp. 72 & 75): there was an extreme “chasm” between my internal and external experiences (Benner, 2015, p.23).

It was only when the walls of this chasm came crashing down with the birth of my daughter, a reflection of pure love, that I realised the “false self” that had been present for so many years, and thus the invitation to acknowledge and heal my broken self came to be. Through continued open reception to the truth in mindful presence (Benner, 2015, pp. 103-104; Siegel, 2010, pp. 1-34), and through internal safety and significance (Siegel, 2012, p. 339; McCann & Pearlman, 1990, p. 158), I came to understand the parts of myself more fully and relationally. Going back to Marshall’s (2001) model (see Appendix One), it is the parts of the soul which open me to who I am in Christ – my “true self” (p. 9) when I am present and allow for receptive healing (Siegel, 2010, pp. 26 & 32).

The mind is the main frame that links the external (body) to the internal (spirit) in order to create subjective experience (Siegel, 2010, pp. 7-8; Marshall, 2001, p. 25). It regulates and interprets input from six main domains (Marshall, 2001, p. 17): our past (memories); the world (human affairs including: culture, economic systems, technology, politics); the devil (exposure to, and attacks from Satan); the flesh (desire, appetites, needs and drives made for self gratification); the human spirit (connection to conscience and intuitive knowledge); and from God (recognised or unrecognised) (Marshall, 2001, pp. 17- 23). However, without the knowledge of the power of these inputs, which is found in mindful presence, behaviours become misguided and the “false self” becomes most dominant (Marshall, 2001, p. 11; Siegel, 2010, pp. 7-9).

This is never more evident than in my own ailment, where there is a “schism” in my mind (Abram, 2007, p. 308) between the “true self” and “false self”, an un-integrated soul (Masterson, 1981, p. 133; Siegel, 2007, pp. 198-199; Cozolino, 2010, pp. 284-285). When triggered my past dominantly takes over and thrusts me into a mind frame where my spirit and my connection with God are severely severed and exacerbated by the devil. I am thrust into a child-like apparition of myself, consumed with fear, reacting in forms of “brittle, vulnerable, self-depreciative, clinging behaviour, and erratic and irrational outbursts of rage” all based in trauma (Masterson, 1981, p. 30).

With emotions in exile, I am unable to trust and am driven into a reactive state where defence mechanisms are protecting the vulnerable and “true self” (Seigel, 2010, p.70; Marshall, 2001, pp. 63 & 64). My own behaviours demonstrating how un-integrated emotions have the ability to distort reality and our subjective experience (Marshall, 2001, pp. 63 & 65). Furthermore, as per my own ailment, implicit memory can trigger emotions that the mind refuses to acknowledge, drawing a wedge between the “false self” and the “true self” into disproportionate sizes and causing a deep wound in need of healing (Marshall, 2001, pp. 65-66). Evidences of wounding can most commonly be seen in relationship, self value, spiritual doubt, despair, and the ability to be present (Marshal, 2001, pp. 66-69; Siegel, 2010, pp. 32-33; Abram, 2007, p. 308). Moreover, sources that inhibit presence and emotional growth, thus the ability to come to our “true self”, stem from trauma based in loss, fear, betrayal, or continued relational miss-attunement (Marshall,2001, p. 67; Siegel, 2010, pp. 42 & 72). Therefore, in order to become more in tune in relationship and indeed with the “true self” one must seek a place of presence where mindfulness leads to integration.

Further to this, without presence we are unable to truly understand or captivate the meaning of freedom (Marshall, 2001, p. 99; Siegel, 2010, p. 12; Abram, 2007, p. 112), and thus our will, that with which we make choices, has the power to distort or hide “true” internal values. This results in behaviours that break the boundaries of moral law and the authority of God (Marshall, 2001, pp. 101, 104 – 105, 107). As such, the “false self” draws towards existential versions of freedom and authority based in absolutes where obedience is stuck in limiting preconceptions and judgments (Marshall, 2001, p. 101; Siegel, 2010, pp. 13 -14; Siegel, 2012, p. 29).

In my own experience, it has been my spiritual connection with the internal values instilled in me, my conscience, which has drawn my mind from the grasps of the rivalry of God’s law and the law of sin and death (Marshall, 2001, pp. 104-105). The will of the flesh (Marshall, 2001, p. 111) drew me towards an un-integrated soul. Yet deep within me, my connection to the spiritual realms were so strong they allowed my will to acknowledge the “false self” and to seek authority in something grander than an existential existence where I was stuck in preconception and judgment, and where presence was unattainable.

THE WILL TO HEAL

My will was only able to acknowledge the “false self” when I met with a radical encounter with the truth (Benner, 2015, p. 72). It was from this encounter (as abovementioned, as the birth of my daughter) I came to understand the power of the conjunction between my spirit and the Holy Spirit, and as such, I gave in to the internalised values written on my heart, and offered my obedience to the authority of the Cross (Marshall, 2001, pp. 113, 117, & 127). The obedience I offered and still offer today, guides my soul to a state of receptivity where presence makes integration a trait and my “true self” becomes at peace (Siegel, 2010, pp. 31-32).

SEEKING SPIRITUALITY: HEALING THROUGH FAITH, HOPE, AND LOVE

Presence is imperative to healing and in living within our “true self”. That is to say, to truly be aware and receptive and to live in connection with God, we must first offer ourselves in obedience based in love. It is within that, the soul’s will makes choices based on values through the authority of Jesus’ sacrifice (Benner, 2015, p. 13; Marshall, 2001, pp.121-123; Alexander, 2007, p. 73; Bible Gateway, n.d.a, ¶Matthew Henry Commentary; Siegel, 2010, p. 1). With renewed regulation and interpretation through revealed knowledge received in faith, and spoken through confession (Marshall, 2001, pp. 236 & 239), the desires of the mind are reformed. Through the power of the Cross and the Holy Spirit (Rom 10:8-10 cited in Marshall, 2001, pp. 234 & 236) we may free the limitations of our minds from the input of the six main domains that reside there (Marshall, 2001, p. 11). Moreover, we can bring ourselves closer towards loving-kindness and to receive healed wholeness (Marshall, 2001, p. 239; Seigel, 2010, pp. 83-85; Bible Study Tools, 2014, ¶1-8).

With our limitations free in Christ the entanglements of our emotions are released from the pain of our past (Marshall, 2001, p.75). With hope, emotions can be expressed in the safety of the communion with the Holy Spirit, and with that joy may flow (Marshall, 2001, pp. 86, 234 & 246). The power of the Cross and the Holy Spirit creates understanding to our emotions from a new perspective. This then releases them for their intended purpose of healing (Marshall, 2001, p. 86; Siegel, 2010, p. 72). With a new understanding of our past, we free ourselves from limitations of defence mechanisms and move toward living more in our “true self”.

The abovementioned principals of harmony through faith, hope, and love that encompass the soul by the spirit and through the body are just the beginning of the journey. That is to say, the “true self” cannot be fully realised until understanding and integration through continued presence takes place in truth and through truth (Siegel, 2010, p. 91). We must actively seek presence to allow the work of the Cross and the Holy Spirit to integrate our souls, bringing us into our “true self”.

PRACTICAL CHANGE

With the concept of the “true self” in place alongside the notions of what it means to be healed: living in the self whom resides in Christ (John 15, NIV, Rohr, 2013, p. 16) and the “only self that will support authenticity… and provide eternal identity…” (Benner, 2015, p.17), we can knowingly move towards connection, security, and of truly being seen (Siegel, 2010, p. xx). Though it may be a long and slow journey in acknowledging and understanding the dark sides of ourselves (Alexander, 2007, pp. 121 – 122), when we actively seek presence, healing is differentiated, sanctified, and integrated within our lives and relationships (Siegel, 2010, p. xii; Alexander, 2007, p. 125; Collins, 2007, p. 66).

Through my own journey, I have come to understand that there is power in mindfulness through cultivating true presence. My ability to be “conscientious, creative, and contemplative” (Siegel, 2010, p. xxv) comes from focusing my mind “… in specific ways to develop a more rigorous from of present moment awareness that can directly alleviate suffering…” (Siegel, 2007, p. 9; see Mind Your Brain, Inc, 2010, ¶1-5, Wheel of Awareness Practice for “specific ways”).

In saying this there is no better way to portray the concept of healing and freedom as conceptualised in the abovementioned notions, than to come to conclusion through bringing my own journey. My hope is to demonstrate the power of the Cross and the Holy Spirit, as well as integration of mind and emotions, is led by a moral will that intuitively “knows” (Rohr, 2007, p.52; Benner, 2015, pp. 38-40; Siegel, 2007, p. 334; Marshall, 2001, p. 234).

BROKEN BY BETRAYAL; RESTORED IN FAITH, HOPE, AND LOVE

Those who have experienced trauma of any kind understand my plight. There is a desperate search of self, and a desperate need to resolve that which inflicted me and made my mind incoherent for so many years (Siegel, 2010, pp. 189-190; Marshall, 2007, p.86).

It is now, some four years after I first began my journey towards my “true self”, that I have come to somewhat understand what it meant when I was screaming to the heavens to “go home”. I have now come to understand that for the most part of my life I was living in falsity, unable to reconcile or integrate memories, emotions, values, truth, nor what I knew intuitively: it was only when I came to a breaking point that I was able to make the choice to come to truth (Siegel, 2010, p. 91).

Through making a choice, through continually making choices each and every day to be humble and to walk alongside Christ, I am able to acknowledge my fallibility and to seek that which opens me to towards my “true self”.

Although I have, and do, practice a variety of tools and techniques (such as CBT, IPT, EFT, Yoga, DBT, client-centred, and the like) there has been nothing more effective than bringing my wounded child-self filled with implicit pain memories to the foot of the Cross within a mindful state of presence (Siegel, 2010, pp. 1-33; 194-196). It is there, within my safe space, I vision the Cross and allow the Holy Spirit to wash over me. With the knowledge that I am free in the new covenant (Marshall, 2001, pp. 121-131) I am able to “be open not only to how things are, but to how they change moment to moment” (Siegel, 2010, p. 197). This allows me to honour, understand, and to be obedient toward the authority of God and to acknowledge the values I reside in and the forgiveness I must seek for that which torments me.

It is within this that I am able to further recognise the truth, and to mindfully, through written prose, spoken confession (Marshall, 2001, pp. 234-239), and with an open heart to hear, communicate with God, and to allow new thought patterns to emerge. With practice I have come to understand this process as that which instills the new thought patterns within my complete being (Siegel, 2010, pp. 259-260; see also pp. 253-260).

Furthermore, healing has not come without a sense of acceptance, security, guidance, and love from a deep connection within community; I have found a sense of compassionate understanding and relational value within the presence of God and others. And while my own healing has been a development of mindful, spiritual practice over years, I come to acknowledge that healing in others, particularly in the Christ-centered, Bible-based context, comes from my own ability to recognise who I am in Christ. That is, incorporating a sense of faith, hope, and love that encompasses the soul by the spirit and through the body, allows my “true self” to be the most dominate aspect of who I am, and as such provides a healing space for others to find freedom in their “true self”.

Abram, J. (2007). The language of Winnicott: A dictionary of Winnicott’s use of words(2nd ed.). London, Great Britan: Karnac Books.

Alexander, I. (2007). Dancing with God: Transformation through relationship. London, Great Britan: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Benner, D. G. (2012). Spirituality and the awakening self: The sacred journey of transformation. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press.

Benner, D. G. (2015). The gift ofbeing yourself: The sacred call to self-discovery. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Bible Gateway. (n.d.). Gen 3:7–11 – Reformation Study Bible – Bible Gateway. Retrieved from https://www.biblegateway.com/resources/reformation-study- bible/Gen.3.7-Gen.3.11

Bible Study Tools. (2014). The humility of Jesus. Retrieved from http://www .biblestudytools.com/classics/murray-humility/humility-in-the-life-of- jesus.html

Collins, G. R. (2007). Christian counseling: A comprehensive guide. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

Cozolino, L. J. (2010). The neuroscience of psychotherapy: Healing the social brain(2nd ed.). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

McCann, L., & Pearlman, L. (1990). Psychological trauma and the adult survivor: Theory, therapy, and transformation. London, Great Britain: Brunner-Routledg.

Marshall, T. (2001). Living in the freedom of the spirit. Lancaster, England: Sovereign World. Masterson, J. F. (1981). The narcissistic and borderline disorders: An integrated developmental approach. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

Mind Your Brain, Inc. (2010). Wheel of Awareness. Retrieved from www .drdansiegel.com/resources/wheel_of_awareness/

Rohr, R. (2013). Immortal diamond: The search for our true self. London, Great Britan: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Siegel, D. J. (2007). The mindful brain: Reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). Mindsight: Change your brain and your life. Brunswick, Australia: Scribe Publications.

Watts, J. (2009). Donald Wincott. In J. Watts, K. Cockcroft, & N. Duncan (Eds.),Developmental psychology (2nd ed., pp. 138-152). Cape Town, South Africa: UCT Press.

Appendix One

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- About Chele Yntema

- Services & Specialties

- Complementary Consultation

Photo by Trent Parke/Magnum

You are a network

You cannot be reduced to a body, a mind or a particular social role. an emerging theory of selfhood gets this complexity.

by Kathleen Wallace + BIO

Who am I? We all ask ourselves this question, and many like it. Is my identity determined by my DNA or am I product of how I’m raised? Can I change, and if so, how much? Is my identity just one thing, or can I have more than one? Since its beginning, philosophy has grappled with these questions, which are important to how we make choices and how we interact with the world around us. Socrates thought that self-understanding was essential to knowing how to live, and how to live well with oneself and with others. Self-determination depends on self-knowledge, on knowledge of others and of the world around you. Even forms of government are grounded in how we understand ourselves and human nature. So the question ‘Who am I?’ has far-reaching implications.

Many philosophers, at least in the West, have sought to identify the invariable or essential conditions of being a self. A widely taken approach is what’s known as a psychological continuity view of the self, where the self is a consciousness with self-awareness and personal memories. Sometimes these approaches frame the self as a combination of mind and body, as René Descartes did, or as primarily or solely consciousness. John Locke’s prince/pauper thought experiment, wherein a prince’s consciousness and all his memories are transferred into the body of a cobbler, is an illustration of the idea that personhood goes with consciousness. Philosophers have devised numerous subsequent thought experiments – involving personality transfers, split brains and teleporters – to explore the psychological approach. Contemporary philosophers in the ‘animalist’ camp are critical of the psychological approach, and argue that selves are essentially human biological organisms. ( Aristotle might also be closer to this approach than to the purely psychological.) Both psychological and animalist approaches are ‘container’ frameworks, positing the body as a container of psychological functions or the bounded location of bodily functions.

All these approaches reflect philosophers’ concern to focus on what the distinguishing or definitional characteristic of a self is, the thing that will pick out a self and nothing else, and that will identify selves as selves, regardless of their particular differences. On the psychological view, a self is a personal consciousness. On the animalist view, a self is a human organism or animal. This has tended to lead to a somewhat one-dimensional and simplified view of what a self is, leaving out social, cultural and interpersonal traits that are also distinctive of selves and are often what people would regard as central to their self-identity. Just as selves have different personal memories and self-awareness, they can have different social and interpersonal relations, cultural backgrounds and personalities. The latter are variable in their specificity, but are just as important to being a self as biology, memory and self-awareness.

Recognising the influence of these factors, some philosophers have pushed against such reductive approaches and argued for a framework that recognises the complexity and multidimensionality of persons. The network self view emerges from this trend. It began in the later 20th century and has continued in the 21st, when philosophers started to move toward a broader understanding of selves. Some philosophers propose narrative and anthropological views of selves. Communitarian and feminist philosophers argue for relational views that recognise the social embeddedness, relatedness and intersectionality of selves. According to relational views, social relations and identities are fundamental to understanding who persons are.

Social identities are traits of selves in virtue of membership in communities (local, professional, ethnic, religious, political), or in virtue of social categories (such as race, gender, class, political affiliation) or interpersonal relations (such as being a spouse, sibling, parent, friend, neighbour). These views imply that it’s not only embodiment and not only memory or consciousness of social relations but the relations themselves that also matter to who the self is. What philosophers call ‘4E views’ of cognition – for embodied, embedded, enactive and extended cognition – are also a move in the direction of a more relational, less ‘container’, view of the self. Relational views signal a paradigm shift from a reductive approach to one that seeks to recognise the complexity of the self. The network self view further develops this line of thought and says that the self is relational through and through, consisting not only of social but also physical, genetic, psychological, emotional and biological relations that together form a network self. The self also changes over time, acquiring and losing traits in virtue of new social locations and relations, even as it continues as that one self.

H ow do you self-identify? You probably have many aspects to yourself and would resist being reduced to or stereotyped as any one of them. But you might still identify yourself in terms of your heritage, ethnicity, race, religion: identities that are often prominent in identity politics. You might identify yourself in terms of other social and personal relationships and characteristics – ‘I’m Mary’s sister.’ ‘I’m a music-lover.’ ‘I’m Emily’s thesis advisor.’ ‘I’m a Chicagoan.’ Or you might identify personality characteristics: ‘I’m an extrovert’; or commitments: ‘I care about the environment.’ ‘I’m honest.’ You might identify yourself comparatively: ‘I’m the tallest person in my family’; or in terms of one’s political beliefs or affiliations: ‘I’m an independent’; or temporally: ‘I’m the person who lived down the hall from you in college,’ or ‘I’m getting married next year.’ Some of these are more important than others, some are fleeting. The point is that who you are is more complex than any one of your identities. Thinking of the self as a network is a way to conceptualise this complexity and fluidity.

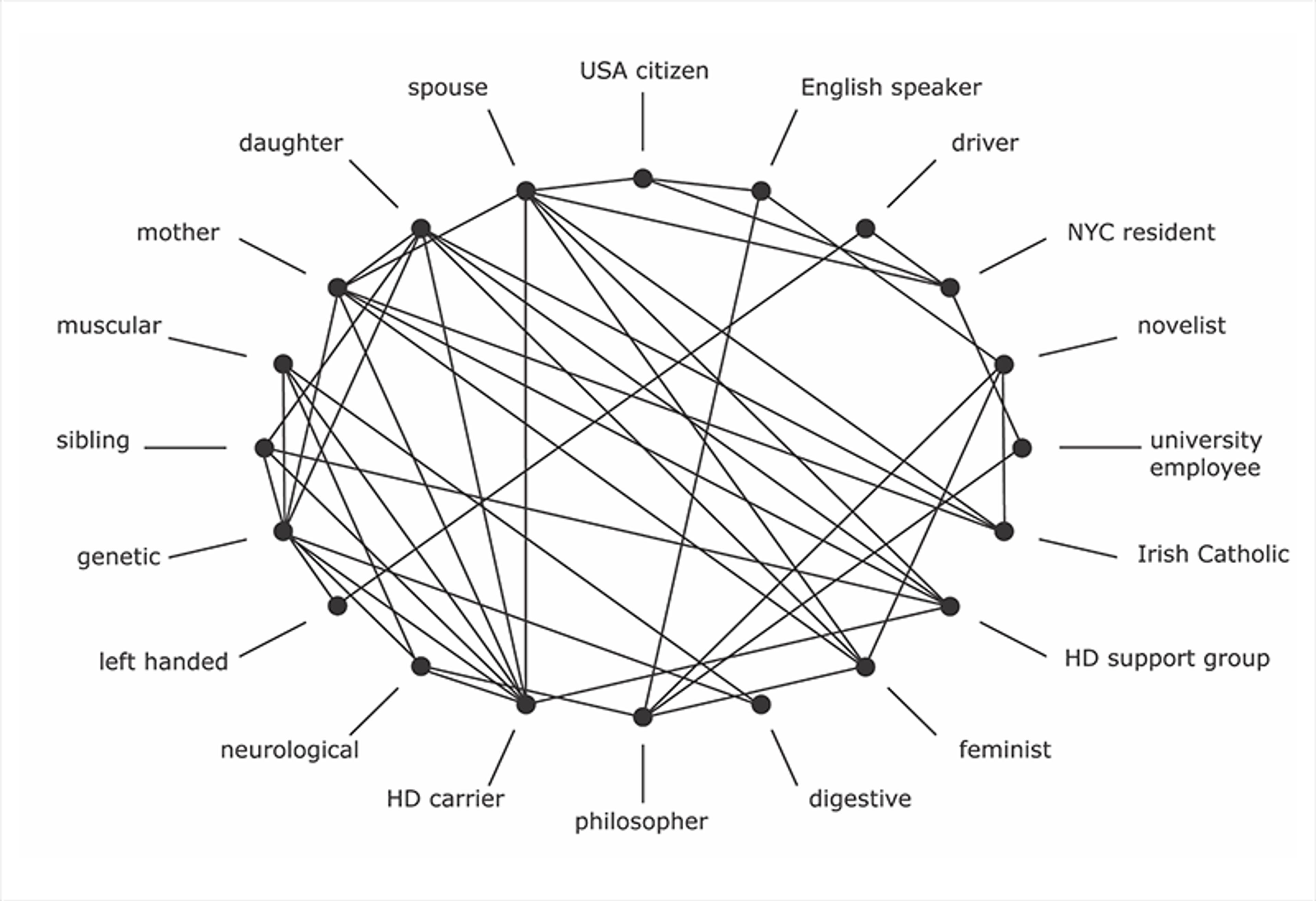

Let’s take a concrete example. Consider Lindsey: she is spouse, mother, novelist, English speaker, Irish Catholic, feminist, professor of philosophy, automobile driver, psychobiological organism, introverted, fearful of heights, left-handed, carrier of Huntington’s disease (HD), resident of New York City. This is not an exhaustive set, just a selection of traits or identities. Traits are related to one another to form a network of traits. Lindsey is an inclusive network, a plurality of traits related to one another. The overall character – the integrity – of a self is constituted by the unique interrelatedness of its particular relational traits, psychobiological, social, political, cultural, linguistic and physical.

Figure 1 below is based on an approach to modelling ecological networks; the nodes represent traits, and the lines are relations between traits (without specifying the kind of relation).

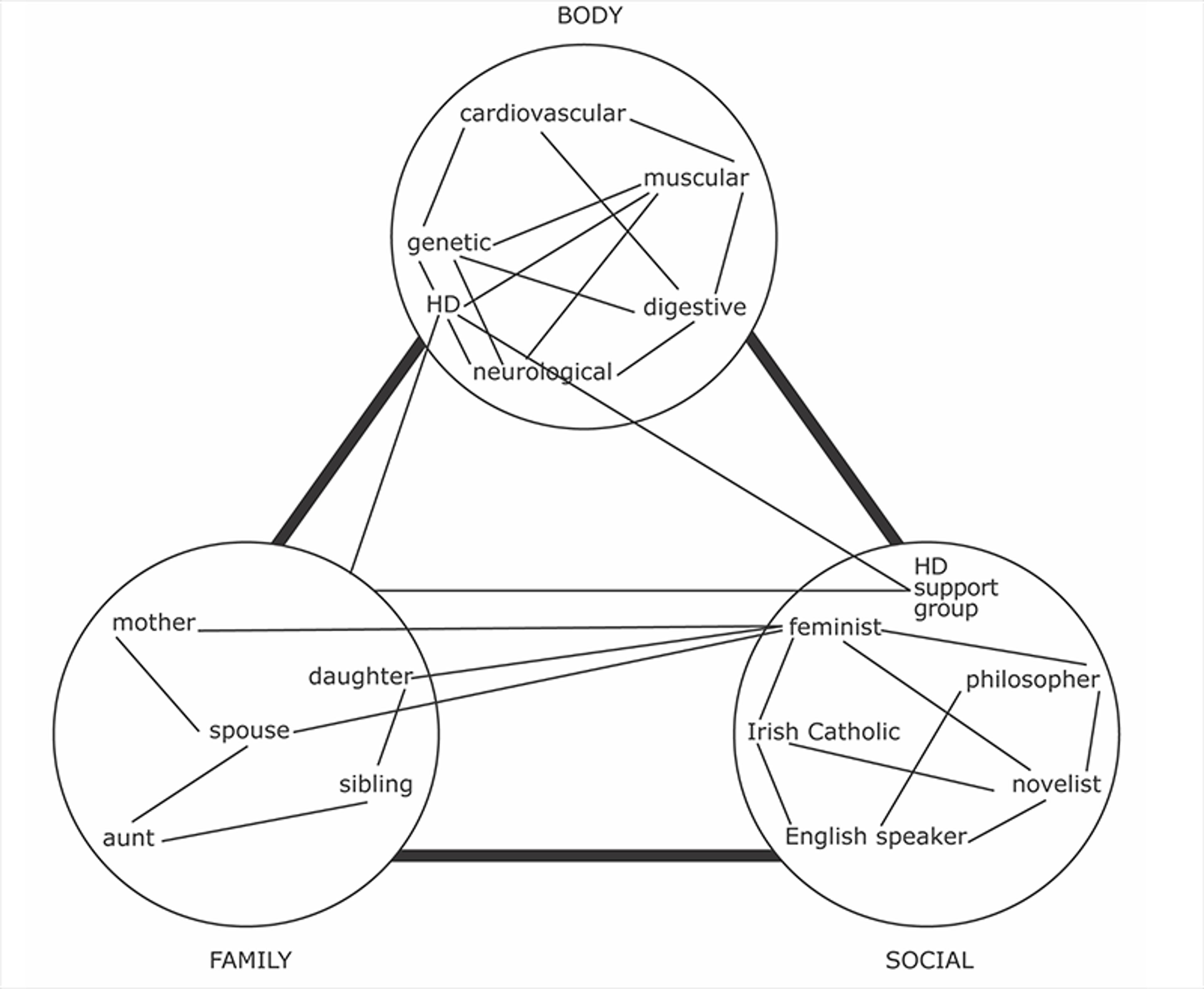

We notice right away the complex interrelatedness among Lindsey’s traits. We can also see that some traits seem to be clustered, that is, related more to some traits than to others. Just as a body is a highly complex, organised network of organismic and molecular systems, the self is a highly organised network. Traits of the self can organise into clusters or hubs, such as a body cluster, a family cluster, a social cluster. There might be other clusters, but keeping it to a few is sufficient to illustrate the idea. A second approximation, Figure 2 below, captures the clustering idea.

Figures 1 and 2 (both from my book , The Network Self ) are simplifications of the bodily, personal and social relations that make up the self. Traits can be closely clustered, but they also cross over and intersect with traits in other hubs or clusters. For instance, a genetic trait – ‘Huntington’s disease carrier’ (HD in figures 1 and 2) – is related to biological, family and social traits. If the carrier status is known, there are also psychological and social relations to other carriers and to familial and medical communities. Clusters or sub-networks are not isolated, or self-enclosed hubs, and might regroup as the self develops.

Sometimes her experience might be fractured, as when others take one of her identities as defining all of her

Some traits might be more dominant than others. Being a spouse might be strongly relevant to who Lindsey is, whereas being an aunt weakly relevant. Some traits might be more salient in some contexts than others. In Lindsey’s neighbourhood, being a parent might be more salient than being a philosopher, whereas at the university being a philosopher is more prominent.

Lindsey can have a holistic experience of her multifaceted, interconnected network identity. Sometimes, though, her experience might be fractured, as when others take one of her identities as defining all of her. Suppose that, in an employment context, she isn’t promoted, earns a lower salary or isn’t considered for a job because of her gender. Discrimination is when an identity – race, gender, ethnicity – becomes the way in which someone is identified by others, and therefore might experience herself as reduced or objectified. It is the inappropriate, arbitrary or unfair salience of a trait in a context.

Lindsey might feel conflict or tension between her identities. She might not want to be reduced to or stereotyped by any one identity. She might feel the need to dissimulate, suppress or conceal some identity, as well as associated feelings and beliefs. She might feel that some of these are not essential to who she really is. But even if some are less important than others, and some are strongly relevant to who she is and identifies as, they’re all still interconnected ways in which Lindsey is.

F igures 1 and 2 above represent the network self, Lindsey, at a cross-section of time, say at early to mid-adulthood. What about the changeableness and fluidity of the self? What about other stages of Lindsey’s life? Lindsey-at-age-five is not a spouse or a mother, and future stages of Lindsey might include different traits and relations too: she might divorce or change careers or undergo a gender identity transformation. The network self is also a process .

It might seem strange at first to think of yourself as a process. You might think that processes are just a series of events, and your self feels more substantial than that. Maybe you think of yourself as an entity that’s distinct from relations, that change is something that happens to an unchangeable core that is you. You’d be in good company if you do. There’s a long history in philosophy going back to Aristotle arguing for a distinction between a substance and its properties, between substance and relations, and between entities and events.

However, the idea that the self is a network and a process is more plausible than you might think. Paradigmatic substances, such as the body, are systems of networks that are in constant process even when we don’t see that at a macro level: cells are replaced, hair and nails grow, food is digested, cellular and molecular processes are ongoing as long as the body is alive. Consciousness or the stream of awareness itself is in constant flux. Psychological dispositions or attitudes might be subject to variation in expression and occurrence. They’re not fixed and invariable, even when they’re somewhat settled aspects of a self. Social traits evolve. For example, Lindsey-as-daughter develops and changes. Lindsey-as-mother is not only related to her current traits, but also to her own past, in how she experienced being a daughter. Many past experiences and relations have shaped how she is now. New beliefs and attitudes might be acquired and old ones revised. There’s constancy, too, as traits don’t all change at the same pace and maybe some don’t change at all. But the temporal spread, so to speak, of the self means that how a self as a whole is at any time is a cumulative upshot of what it’s been and how it’s projecting itself forward.

Anchoring and transformation, sameness and change: the cumulative network is both-and , not either-or

Rather than an underlying, unchanging substance that acquires and loses properties, we’re making a paradigm shift to seeing the self as a process, as a cumulative network with a changeable integrity. A cumulative network has structure and organisation, as many natural processes do, whether we think of biological developments, physical processes or social processes. Think of this constancy and structure as stages of the self overlapping with, or mapping on to, one another. For Lindsey, being a sibling overlaps from Lindsey-at-six to the death of the sibling; being a spouse overlaps from Lindsey-at-30 to the end of the marriage. Moreover, even if her sibling dies, or her marriage crumbles, sibling and spouse would still be traits of Lindsey’s history – a history that belongs to her and shapes the structure of the cumulative network.

If the self is its history, does that mean it can’t really change much? What about someone who wants to be liberated from her past, or from her present circumstances? Someone who emigrates or flees family and friends to start a new life or undergoes a radical transformation doesn’t cease to have been who they were. Indeed, experiences of conversion or transformation are of that self, the one who is converting, transforming, emigrating. Similarly, imagine the experience of regret or renunciation. You did something that you now regret, that you would never do again, that you feel was an expression of yourself when you were very different from who you are now. Still, regret makes sense only if you’re the person who in the past acted in some way. When you regret, renounce and apologise, you acknowledge your changed self as continuous with and owning your own past as the author of the act. Anchoring and transformation, continuity and liberation, sameness and change: the cumulative network is both-and , not either-or .

Transformation can happen to a self or it can be chosen. It can be positive or negative. It can be liberating or diminishing. Take a chosen transformation. Lindsey undergoes a gender transformation, and becomes Paul. Paul doesn’t cease to have been Lindsey, the self who experienced a mismatch between assigned gender and his own sense of self-identification, even though Paul might prefer his history as Lindsey to be a nonpublic dimension of himself. The cumulative network now known as Paul still retains many traits – biological, genetic, familial, social, psychological – of its prior configuration as Lindsey, and is shaped by the history of having been Lindsey. Or consider the immigrant. She doesn’t cease to be the self whose history includes having been a resident and citizen of another country.

T he network self is changeable but continuous as it maps on to a new phase of the self. Some traits become relevant in new ways. Some might cease to be relevant in the present while remaining part of the self’s history. There’s no prescribed path for the self. The self is a cumulative network because its history persists, even if there are many aspects of its history that a self disavows going forward or even if the way in which its history is relevant changes. Recognising that the self is a cumulative network allows us to account for why radical transformation is of a self and not, literally, a different self.

Now imagine a transformation that’s not chosen but that happens to someone: for example, to a parent with Alzheimer’s disease. They are still parent, citizen, spouse, former professor. They are still their history; they are still that person undergoing debilitating change. The same is true of the person who experiences dramatic physical change, someone such as the actor Christopher Reeve who had quadriplegia after an accident, or the physicist Stephen Hawking whose capacities were severely compromised by ALS (motor neuron disease). Each was still parent, citizen, spouse, actor/scientist and former athlete. The parent with dementia experiences loss of memory, and of psychological and cognitive capacities, a diminishment in a subset of her network. The person with quadriplegia or ALS experiences loss of motor capacities, a bodily diminishment. Each undoubtedly leads to alteration in social traits and depends on extensive support from others to sustain themselves as selves.

Sometimes people say that the person with dementia who doesn’t know themselves or others anymore isn’t really the same person that they were, or maybe isn’t even a person at all. This reflects an appeal to the psychological view – that persons are essentially consciousness. But seeing the self as a network takes a different view. The integrity of the self is broader than personal memory and consciousness. A diminished self might still have many of its traits, however that self’s history might be constituted in particular.

Plato, long before Freud, recognised that self-knowledge is a hard-won and provisional achievement

The poignant account ‘Still Gloria’ (2017) by the Canadian bioethicist Françoise Baylis of her mother’s Alzheimer’s reflects this perspective. When visiting her mother, Baylis helps to sustain the integrity of Gloria’s self even when Gloria can no longer do that for herself. But she’s still herself. Does that mean that self-knowledge isn’t important? Of course not. Gloria’s diminished capacities are a contraction of her self, and might be a version of what happens in some degree for an ageing self who experiences a weakening of capacities. And there’s a lesson here for any self: none of us is completely transparent to ourselves. This isn’t a new idea; even Plato, long before Freud, recognised that there were unconscious desires, and that self-knowledge is a hard-won and provisional achievement. The process of self-questioning and self-discovery is ongoing through life because we don’t have fixed and immutable identities: our identity is multiple, complex and fluid.

This means that others don’t know us perfectly either. When people try to fix someone’s identity as one particular characteristic, it can lead to misunderstanding, stereotyping, discrimination. Our currently polarised rhetoric seems to do just that – to lock people into narrow categories: ‘white’, ‘Black’, ‘Christian’, ‘Muslim’, ‘conservative’, ‘progressive’. But selves are much more complex and rich. Seeing ourselves as a network is a fertile way to understand our complexity. Perhaps it could even help break the rigid and reductive stereotyping that dominates current cultural and political discourse, and cultivate more productive communication. We might not understand ourselves or others perfectly, but we often have overlapping identities and perspectives. Rather than seeing our multiple identities as separating us from one another, we should see them as bases for communication and understanding, even if partial. Lindsey is a white woman philosopher. Her identity as a philosopher is shared with other philosophers (men, women, white, not white). At the same time, she might share an identity as a woman philosopher with other women philosophers whose experiences as philosophers have been shaped by being women. Sometimes communication is more difficult than others, as when some identities are ideologically rejected, or seem so different that communication can’t get off the ground. But the multiple identities of the network self provide a basis for the possibility of common ground.

How else might the network self contribute to practical, living concerns? One of the most important contributors to our sense of wellbeing is the sense of being in control of our own lives, of being self-directing. You might worry that the multiplicity of the network self means that it’s determined by other factors and can’t be self -determining. The thought might be that freedom and self-determination start with a clean slate, with a self that has no characteristics, social relations, preferences or capabilities that would predetermine it. But such a self would lack resources for giving itself direction. Such a being would be buffeted by external forces rather than realising its own potentialities and making its own choices. That would be randomness, not self-determination. In contrast, rather than limiting the self, the network view sees the multiple identities as resources for a self that’s actively setting its own direction and making choices for itself. Lindsey might prioritise career over parenthood for a period of time, she might commit to finishing her novel, setting philosophical work aside. Nothing prevents a network self from freely choosing a direction or forging new ones. Self-determination expresses the self. It’s rooted in self-understanding.

The network self view envisions an enriched self and multiple possibilities for self-determination, rather than prescribing a particular way that selves ought to be. That doesn’t mean that a self doesn’t have responsibilities to and for others. Some responsibilities might be inherited, though many are chosen. That’s part of the fabric of living with others. Selves are not only ‘networked’, that is, in social networks, but are themselves networks. By embracing the complexity and fluidity of selves, we come to a better understanding of who we are and how to live well with ourselves and with one another.

To read more about the self, visit Psyche , a digital magazine from Aeon that illuminates the human condition through psychology, philosophical understanding and the arts.

Thinkers and theories

Rawls the redeemer

For John Rawls, liberalism was more than a political project: it is the best way to fashion a life that is worthy of happiness

Alexandre Lefebvre

Anthropology

Your body is an archive

If human knowledge can disappear so easily, why have so many cultural practices survived without written records?

Helena Miton

Seeing plants anew

The stunningly complex behaviour of plants has led to a new way of thinking about our world: plant philosophy

Stella Sandford

Sex and sexuality

Sexual sensation

What makes touch on some parts of the body erotic but not others? Cutting-edge biologists are arriving at new answers

David J Linden

Knowledge is often a matter of discovery. But when the nature of an enquiry itself is at question, it is an act of creation

Céline Henne

Human reproduction

When babies are born, they cry in the accent of their mother tongue: how does language begin in the womb?

Darshana Narayanan

Member-only story

You Are Not What You Think You Are — The False Self, The Ego, and The True Self

Or, to be free, free yourself from your self..

Michael Burkhardt

Ascent Publication

I traveled to more than 40 countries, meditated more than 300 hours this year, fell in love, broke up, and work on an uncertain startup business.

In all of these endeavors, I thought a lot about the self.

And how it creates suffering in our lives.

Or in other words, how we create suffering.

Pain and suffering are two completely different experiences. Pain is unavoidable. Suffering is self-created. — Noah Levine

A big realization I had during my meditation practices is that we are the creators of our life experiences. It is never the outside situation or person, which is responsible for our mental and emotional state.

It is always our way of reacting to the situation.

We choose to be angry, sad, or to be forgiving, and joyful.

Our self, our sense of I, is the conscious or unconscious dirigent of our thoughts and emotions.

The less aware we are about this, the less in control we are in our lives.

Written by Michael Burkhardt

Slow Travel | Meditation | Founding Member, CMO @Omdena

Text to speech

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

The true self. critique, nature, and method.

- 1 Department of Psychology and Psychotherapy, University of Witten/Herdecke, Witten, Germany

- 2 Department of Psychology, Integrated Curriculum for Anthroposophic Psychology (ICURAP), University of Witten/Herdecke, Witten, Germany

- 3 Department of Medicine, Integrated Curriculum for Anthroposophic Medicine (ICURAM), Witten/Herdecke University, Witten, Germany

- 4 Department of Medicine, Institute of Integrative Medicine, Witten/Herdecke University, Witten, Germany

The history of philosophy gives us many different accounts of a true self, connecting it to the essence of what a person is, the notion of conscience, and the ideal human being. Some proponents of the true self can also be found within psychology, but its existence is mostly rejected. Many psychological studies, however, have shown that people commonly believe in the existence of a true self. Although folk psychology often includes a belief in a true self, its existence is disputed by psychological science. Here, we consider the critique raised by Strohminger et al., stating that the true self is (1) radically subjective and (2) not observable, hence cannot be studied scientifically ( Strohminger et al., 2017 ). Upon closer investigation, the argument that the self is radically subjective is not convincing. Furthermore, rather than accepting that the true self cannot be studied scientifically, we ask: What would a science have to look like to be able to study the true self? In order to answer this question, we outline the conceptual nature of the true self, which involves phenomenological and narrative aspects in addition to psychological dimensions. These aspects together suggest a method through which this concept can be investigated from the first-person perspective. On a whole, we propose an integrative approach to understanding and investigating the true self.

Introduction

Let us start with a quote: “Many people like to think they have an inner “true” self. Most social scientists are skeptical of such notions. If the inner self is different from the way the person acts all the time, why is the inner one the “true” self?” ( Baumeister and Bushman, 2013 , p. 75). This is how the notion of a true self is introduced in a recent textbook on social science. It is suggested that there is a conflict between folk psychology and science, where the true self is a notion that does not hold up to closer scrutiny. This view has recently been reinforced by a number of studies conducted by Strohminger and Nichols (2014) and Strohminger et al. (2017) , showing that belief in a true self is indeed common while questioning its actual existence. Is the view we have of our “true self” merely a reflection of the socio-cultural environment in which we exist? And can someone have a “true self” that is good, even if they continually act in ways that are harmful?

Positing a chimera of an inherently good “true self,” existing so deeply within the structure of someone’s psyche that it may never make an appearance in reality may seem completely unwarranted. Not only does this put the true self beyond scientific observation, it also makes it seem like a hopelessly optimistic dream. Hence, although it is empirically clear that people make use of the concept of a true self – in the sense of that which cannot change without someone becoming less of what they really are – there are weighty reasons to doubt whether the true self exists beyond the widespread belief in it. Since this belief is so common, could it be that it is in fact grounded in reality?

This is the question that we will explore in the following, outlining not only a suggestion for what the structure of the true self might be but also sketching out a method for investigating it. In doing this, we will also provide counter-arguments to the critique of the aforementioned true self. In our view, the true self can be viewed as having a kind of spiritual existence. It can appear in time but also exists beyond time. It may even be absent at different moments in time without ceasing to exist. Complete absence of the true self would, however, make it impossible to investigate. We take it that we are dealing with an essence of the Hegelian kind, i.e. an essence, the essence of which is to appear (and indeed, can there be an essence that never appears?). In other words, the true self cannot be so chimeric as to never enter the stage of actual life. However, such an object of study cannot be investigated adequately using conventional philosophical or psychological methods alone. We propose that the true self may be approached through a first-person method combining both philosophical reflection and introspective observation, as we will outline in section “Outline of a Comprehensive First-Person Method for Studying the True Self.” Before introducing this method, we will look into the history and nature of the self and the true self in philosophy and psychology (section “Introduction”). This will follow with a response to critiques of the true self (section “The Problem of Radical Subjectivity and Observability of the True Self”).

A Short Historical Account of the Self and the True Self

The self, one of the most central as well as critically discussed concepts in philosophy and psychology, has a long history. The idea that one has an underlying self in addition to a surface personality can be traced back to the notion that one has a soul that is potentially immortal. In the Egyptian culture, only the Pharaoh possessed an immortal, divine soul (akh) while alive. Only at the moment of death could other Egyptians gain such a soul ( Waage, 2008 ). In Ancient Greek culture, Socrates was known for having heard an inner voice that indicated to him what he should ( Memorabilia 1.1.4, 4.3.12, 4.8.1, Apology 12) and should not do ( Apology 31c-d, 40a-b, Euthydemus 272e-273a). This was part of what lead to his demise, as he was accused of following other gods. The inner voice was a daimonion , a divine being (particular) to Socrates and not one of the gods condoned by the Athenian city-state. Such a private divine being is now commonly understood to refer to conscience in the Christian tradition ( Schinkel, 2007 , p. 97), which is connected to the moral essence – the true self – of an individual. The idea of a person’s moral essence was developed further in Greek thought. For example, it was connected to the performance of specific virtues by Aristotle. Aristotle also suggested that “the true self of each” is the divine intellect or nous (NE, 1178, a2).

However, when answering the question “who are you?”, it was for a long time customary to name one’s ancestors. In ancient Rome, the firstborn son was the property of the pater familias until the death of the father. During the funeral procession, the son wore the father’s death mask ( Salemonsen, 2005 ). It may be noted that the word “mask” ( lat. persona) is related to the word “person,” suggesting that we can take on different identities but also that there is an underlying essence. Augustus is known for writing the first autobiography, inaugurating a genre defined by the idea that certain events and thoughts are more important than others when seeking to understand who someone is. Arguably, the Judeo-Christian religions also contributed to the view that all human beings have a divine core, regardless of background: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). In the Renaissance, Pico della Mirandola emphasized the notion of agency in his “Oration on human dignity”, making God exclaim that it is a matter of will whether the human being shall become animal or divine, mortal or immortal:

I have placed you at the very center of the world, so that from that vantage point you may with greater ease glance round about you on all that the world contains. We have made you a creature neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, in order that you may, as the free and proud shaper of your own being, fashion yourself in the form you may prefer. It will be in your power to descend to the lower, brutish forms of life; you will be able, through your own decision, to rise again to the superior orders whose life is divine ( della Mirandola, 1996 , p. 7).

For Kant, the self is that which provides transcendental unity to our thoughts and perceptions, in short, to all our experiences ( Kant, 1904 ). Although the self cannot be known as it is in itself, in Kantian ethics, the individual is fully autonomous, free, when it acts according to rational principles ( Kant, 1968 ). The individual manifests the kingdom of heaven on earth to the extent that ethical principles are adhered to as if they were natural laws. As a reaction to this, some philosophers, such as Sartre, point out that this view disregards the communal and social aspects of the self as well as its individuality and authenticity ( Sartre, 2014 ). Rejecting Sartre’s notion of authenticity, Foucault denied that there is any self that is given to us; claiming that we should rather view the self as a work of art:

I think that from the theoretical point of view, Sartre avoids the idea of the self as something that is given to us, but through the moral notion of authenticity, he turns back to the idea that we have to be ourselves – to be truly our true self. I think that the only acceptable practical consequence of what Sartre has said is to link his theoretical insight to the practice of creativity – and not that of authenticity. From the idea that the self is not given to us, I think that there is only one practical consequence: we have to create ourselves as a work of art ( Focault, 1997 , p. 262).

Foucault points out that Sartre’s notion of authenticity reintroduces a given measure for someone’s true self. Foucault thinks we should be more radical in our rejection of any given content or measure of what constitutes the true self. Any such content or measure we must create ourselves. One may remark that even creative acts contain an element of or at least relate to something given, for example an inspiration or a framework of understanding. The idea of creating a self does not need to be thought of as a pure/arbitrary invention of something incomprehensible. Creative acts may be understood instead as the encounter between something given and subjective energy. In part, the subject identifies with the given, subjects itself to it, and in part, the subject recognizes the given as itself.

If we pause and summarize here, we can see that there is a whole host of ideas connected to the self in the Western canon (for a discussion of self, no-self and true self accounts in Asian traditions, see Siderits et al., 2010 ):

1. The self is a kind of essence, substance, or a soul that may or may not survive death

2. The self is the voice of conscience, the source of moral or authentic action

3. The self is divine, possibly created by God

4. The self is related to the past, to ancestry, and outward identity such as one’s work

5. The self has a story connected to it that can be represented in a biography

6. The self provides unity to cognition and experience

7. The self is a free, autonomous agent

8. The self is essentially connected to other human beings and culture

9. The self has to be created

As we can see from this short and non-exhaustive list, the self is complex and may be conceived in conflicting ways. For example: Is the self-created by God or the individual? Is the self completely autonomous or is it thoroughly culturally determined? Is the self an essence or is it a story? None of these are necessarily contradictory, but much work is required to flesh out a comprehensive conception of the self. Do all these characteristics have something in common? This question is not easy to answer. If we cannot find a common characteristic in all the different definitions, we may have to concede that the self is simply a name for a host of unrelated ideas or aspects of human existence. On a closer look, each item on the list can potentially be said to be the true self. Even one’s outward identity could arguably be seen to constitute a true self. Imagine a puer aeternus , a Peter Pan-like existence: someone who is reluctant about identifying with anything at all, preferring to stay adolescent indefinitely. For such a person, actually identifying with something could be said to be a realization of their true self (their true self would not necessarily be the specific outward identity but could be manifested by taking on a concrete and not fantastical identity). There is one way of conceiving what the nature of the true self is, which we will elaborate in the following, that does not imply that we have to make a choice about which specific self represents the true one. This is the conception of the true self as a whole that unifies the different selves. Moreover, the true self can not only be viewed as a whole but also as the manifestation of a specific moral self that has grown out of the past. The true self, on this conception, has both distanced itself from the past and integrated it, moving toward an ideal that is in one sense given, internally and from the past, but in another sense must also be created, or is only just coming into existence from the future.

The True Self in Philosophy and Psychology

Although the existence of the self is controversial in philosophy ( Metzinger, 2003 ; Siderits et al., 2010 ; Ganeri, 2012 ), there are a number of influential philosophers who claim that there at least a minimal or core self exists. Such a view can be found both among traditional thinkers, such as Descartes, Leibniz, Kant, Hegel, Husserl, etc., and contemporary ones ( MacIntyre, 1981 ; Taylor, 2012 ; Zahavi, 2017 ). Charles Taylor has specifically addressed the notion of a true self in the context of a discussion of negative and positive freedom ( Taylor, 1985 ; Sparby, 2014 ). Negative freedom is the idea that one can realize one’s true self insofar as there are no external restrictions on the self (and perhaps no internal restrictions such as fear). But where does the understanding of what actually counts as being the true self come from? If it comes, for instance, from a totalitarian state, then the “true self” may indeed be a false self since someone other than the self determines it. Hence it would follow that actualizing a true self is typically seen to include self-determination. It could of course be that content of a state prescribed true self accords by coincidence with the true self recognized by a person. This would not stop the person from actualizing the true self as long as the recognition is internally constituted through reflection and moral deliberation. However, if someone can determine themselves radically, does this not mean that the content of the true self is arbitrary? We believe that such problems can be solved with ideas as such “being-with-oneself in otherness” ( Sparby, 2016 ). For example, acting according to one’s true self does not exclude acting according to principles as long as these principles are recognized as stemming from the true self. Finding one’s true self may involve finding oneself in another person, community, culture, etc. This does not mean that the true self is simply something given. Even creative processes can involve something approaching the self “from the outside”, such as an inspiration. Again, the true self can be viewed as a whole, as something transcending the subject-object dichotomy, allowing for such events where something comes to the self seemingly from an external source (e.g. the voice of conscience), a source which is, however, more adequately conceived of as belonging to the self in a deeper, higher or more inclusive sense. It is of course possible that the voice of conscience might be an expression of an internalized dogmatic morality. However, this does not make it unreliable in principle. It means that what it dictates has to be viewed in light of an investigation of what its source might be, considering cultural factors specifically.

Is a person always acting in accordance with their true self if they act according to their self? The problem here is that the self is not only multifaceted but also contradictory given that different aspects are in conflict with each other. For example, the human being can act out of principle or according to their desires. Both may be viewed or at least experienced as essential parts of one’s identity, although these parts do not always harmonize. If one acts according to one’s desire, another desire may not be fulfilled. If one acts morally, desires may fail to be satisfied at all. If one acts in a case where there is a moral dilemma, the true self seems to be constituted by that act. But what if I act based on wrong information, inherited cultural views, or delusion? Indeed, as we shall see, one of the main critiques of the true self is its radical subjectivity. The beliefs and actions that we ascribe to the true self depend on our worldview that is ultimately a reflection of the culture we belong to.

The field of psychology has contributed to our understanding of the self by gathering empirical support for the view that we are indeed ruled by external forces, such as unconscious desires, bias, and social conditioning. It has been shown that the experience of living a meaningful life is associated with having cognitive access to one’s true self, and yet psychological research remains either skeptical or agnostic about the existence of it ( Schlegel et al., 2013 ) despite the belief in a true self seems to be independent of personality type and culture ( De Freitas et al., 2018 ). However, one can indeed find representatives of notions of a true self also in psychology. The true self is sometimes referred to as the I-self or self-as-process as opposed to the me-self or self-as-object ( Ryan and Rigby, 2015 ). The former “concerns the conceptions, images, roles, statuses, and attributes associated with an identity,” while the latter “concerns the inherent integrative tendencies of people to understand, grow, and create coherence in their experiences” ( Ryan and Rigby, 2015 , p. 246). The psychoanalyst Winnicott made explicit use of the concept of a true self, contrasting it with the false self ( Winnicott, 1965 ). His view of the true self can be summarized as the self that is spontaneous, alive, and creative – the false self would then be a persona that lacks those characteristics ( Rubin, 1998 , p. 102). Numerous other terms are used for the true self such as the real self, the ideal self, the authentic self, the intrinsic self, the essential self, and the deep self [see overview of sources in Strohminger et al. (2017) ]. Strohminger et al. have shown that people on average understand moral traits to be most fundamental to a person in addition to personality, memories, and desires, while characteristics related to perceptual abilities (e.g. near-sightedness) and psychical traits are perceived as having the least impact on who someone essentially is ( Strohminger and Nichols, 2014 ). The essential differences between the self and the true self according to Strohminger et al. are that the self (1) encompasses the entire range of personal features, (2) is valence independent (it is inherently neither good nor bad) but (3) is perspective (first- or third-person) dependent, and (4) is cross-culturally variable, while the true self has an emphasis on (1) moral features, is (2) valence-dependent or positive by default, (3) perspective independent, and (4) cross-culturally stable ( Strohminger et al., 2017 , p. 3).

Strohminger et al. have also provided a particularly powerful formulation of the argument against the true self, which is quoted in full since it is the critique used as the background to our suggestion of what the nature of the true self is and how it can be studied:

Is the true self also a scientific concept, one that can be used to describe how the mind actually works? Is there, in other words, a true self? The evidence reviewed here points to two properties relevant to this question. One: the true self depends on the values of the observer. If someone thinks homosexual urges are wrong, she will say the desire to resist such urges represents the true self ( Newman et al., 2014 ). And if she scores high in psychopathy, she will assign less weight to moral features in her conceptualization of personal identity ( Strohminger and Nichols, 2014 ). What counts as part of the true self is subjective, and strongly tied to what each individual person herself most prizes.

Two: The true self is, shall we say, evidence-insensitive. Resplendent as the true self is, it is also a bashful thing. Yet people have little trouble imbuing it with a host of hidden properties. Indeed, claims made on its behalf may completely contradict all available data, as when the hopelessly miserable and knavish are nonetheless deemed good “deep down”. The true self is posited rather than observed. It is a hopeful phantasm.

These two features—radical subjectivity and unverifiability—prevent the true self from being a scientific concept. The notion that there are especially authentic parts of the self, and that these parts can remain cloaked from view indefinitely, borders on the superstitious. This is not to say that lay belief in a true self is dysfunctional. Perhaps it is a useful fiction, akin to certain phenomena in religious cognition and decision-making ( Gigerenzer and Todd, 1999 ; Boyer, 2001 ). But, in our view, it is a fiction nonetheless ( Strohminger et al., 2017 , p. 7).

To reiterate, the problem facing the true self-view is that it is a conception tied to the values of a person, which are determined subjectively according to the structure of their personality, and by the culture and social environment in which that person exists. What the authors mean by “radical subjectivity” is, however, not clear. Does it mean that the values that a person uses to measure whether they live up to their true self are arbitrary, that the true self is based on a radical existential choice not grounded in anything, or that it is determined by biological, cultural, or social factors that happen to affect the person? These are issues that need to be untangled and answered. Furthermore, a good response is needed when arguing that the true self is not observable and therefore fictional. In particular, does it make sense to speak of a true self if that self never manifests? Can a person be called inherently good if they commit heinous crimes and consistently act in ways that are harmful to others, taking pleasure in their suffering?

In order to argue in favor of the existence of the true self, one must address the critique that it is a radically subjective notion and that it is unverifiable. Since we take the view that the self is not a thing with clearly defined borders but rather an organizing principle of a continual process, speaking of “the existence” of a true self can be misleading. Nevertheless, one may claim that there is such an organizing principle and that the true self is neither radically subjective nor unverifiable. Before turning to that, we will provide a preliminary delineation of the true self that we will flesh out as we address the critique above.

A Thin and Thick Conception of the True Self and Their Unity

Two conceptions of the true self are implicit in what has been said above, which we will refer to as the thin and thick conception of the true self. One way to characterize them is to say that the thin conception is static: unchangeable, timeless, always the same. The thick conception is dynamic: developing, spread out over long changes of time, and continually emerging. The current objective in the following is to unite these two conceptions (in fact, to show how they are interdependent) and to investigate how such an account may be able to respond to the critique raised against the true self that we will focus on in section “The Problem of Radical Subjectivity and Observability of the True Self”.

The thin conception of the true self is the idea that the self has a deeper and more essential nature; the true self is identical to this essential part of the self. Some of the properties attached to the self are accidental while others are essential. Someone can change their job and although they may have identified with their job, they do not really cease to be who they truly are when they change jobs. The true self as the essential self can consist of either one essential property or a set of properties. Sometimes, this is also referred to as the minimal self, which can be defined as the simple quality of subjective experience; the most fundamental experience of what it is like to be this or that subject ( Zahavi, 2017 ). However, as pointed out by Fasching, the essential self’s nature may be exactly a bare existence ; not recognizable by any property. It simply is and we know it as something that can identify itself with potentially anything but can never be reduced to any specific property ( Fasching, 2016 ). A similar view is presented by Ramm, who, using first-person experiments, argues that the self in itself both lacks sensory qualities and is single ( Ramm, 2017 ).

If we conceive of the true self along these lines, the result would be rather indeterminate. There would be nothing more to it than what is common to all other selves: a simple and unique existence potentially aware of itself as such. Any identification of the self with a particular property, such as being a human, acting morally, or having been born in a certain place, would be fully irrelevant to the true self. But this seems wrong – or at least too indeterminate. Not only would it be at odds with typical conceptions of the true self, it would also conceptualize the true self in the form of a ghost with no bearing on its environment. This leads us to the thick conception of the true self [compare Galen Strawson’s conception of the self, which differentiates between the self as a distinct mental entity and a subject of experience and the self as an agent, personality and diachronic continuity ( Strawson, 1997 )]. The thick conception of the true self connects it to certain substantial and moral properties such as being able to form memories or making an existential choice. Hence the thick conception where the true self consists of more determinate characteristics than bare existence is in accordance with how the true self is typically conceived in folk psychology. Is there a specific property or set of properties the self can identify with to become a true self or at least a “truer” self? Can one make a choice or live in a way that does not represent the ideal version of that individual? This certainly seems to be the case. But what is the measure according to which an act or a way of life can be judged as being in accordance with one’s true self? Who or what decides what counts as a proper measure? What is it based on? Where does the true self come from? It will later be discussed how the true self is essentially related to both the past and the future. It will also be suggested that a certain conception of the true self can unite both the thin and thick version of it. Before turning to that, however, we turn to some discussions surrounding the true self in philosophy and psychology.

The Problem of Radical Subjectivity and Observability of the True Self

Here we will consider the two problems connected to the idea of the true self as identified by Nichols et al. above.

Radical Subjectivity

As we have seen, the problem of radical subjectivity relates to the notion that how someone conceives of their true self is dependent on what values they have. As we have stated earlier, there are more ways of interpreting what the claim that the true self is “radically subjective” means. It can mean that the true self is based on: (1) something completely arbitrary, (2) an ungrounded existential choice or (3) external factors, such as culture and biology. Although Strohminger et al. do not state explicitly which interpretation they have in mind, we think, based on the examples they give (sexual preference and psychopathy), that the third option is more likely. A person’s sexual preference is rarely considered to be a choice but is rather understood to be based on biology and culture; psychopathy is hardly conceivable as a choice, but, again, is widely believed to be contingent upon biological, cultural or other environmental factors.

This, however, may seem surprising: Does not “radical subjectivity” mean something that involves arbitrariness or some form of creative or spontaneous choice? Since Strohminger et al. speak of the “radical subjectivity” of the true self as tied to what someone prizes or values, there might be some merit to the interpretation of it as being indeterminate in some way (not based on factors external to the self). But then again, the examples they mention point in another direction. So is the critique of the “true self” as radically subjective based on (1) the idea that it is radically arbitrary, random or contingent (what someone happens to value) or (2) the idea that the external factors that a person has happened to be exposed to due to the geographical location of their life and their inheritance has determined what they value?

It is highly unlikely that someone would hold the view that what someone values is completely arbitrary, based on something akin to the random result of throwing dice. For example, we value food because of biological needs, friendship because of social needs, and certain ideas because we find them enlightening. However, when we are presented with a moral choice or dilemma or when we are challenged with coming up with a plan for our next steps in life, our choice might seem subjective in the sense that it is creative or ultimately relies on a decision. But if it is creative, this does not mean that it is arbitrary – as we argued above in relation to Foucault. And if it is ultimately based on a decision, this does not mean that we do not have good reasons for acting the way we do, although we might have reasons to act in other ways as well. So the choice itself might be spontaneous, but that does not mean that it is arbitrary in the sense of not being grounded in reasons. And insofar as it is not clear to us what reasons are the best when considering a moral dilemma or committing to a life path, we could regard the choice as creative – but again, such creativity does not have to be arbitrary. What we are left with is the notion that someone’s idea of their true self is radically subjective because it is based on what they happen to value, which in turn is based on the features of their personality. We will consider this in more depth.

Depending on one’s sexual preference or whether one has a personality disorder such as psychopathy, one may conceive of the core of one’s personality differently. This boils down to a claim there are a variety of different conceptions of the self and that therefore how someone defines their true self is subjective. Such a view, however, fails to consider the possibility that one may be right or wrong about their true self. If there were a true self, it would indeed be possible to make such mistakes. We cannot take it for granted that there is no true self based simply on the fact that people value things differently and conceive of their true nature accordingly. Even if I value money and claim that I am affluent, I would be mistaken about this claim if I have no money. Even though people value things differently, and the specific values someone has influence how they conceive of their essential nature, it does not follow that one’s true self is merely an extension of what one happens to value.

However, it is still a significant point that one’s conception of oneself tends to co-vary with one’s cultural background. Could it not be the case that someone’s true self harmonizes with what a specific culture dictates, while someone else in that culture could have a completely different true self; one that runs counter to the common views and values? How would someone know if they were mistaken, i.e. simply influenced by their culture, when it comes to viewing what their true identity is? The true self may indeed be fully individual. How does one uncover it? Perhaps, this is possible exactly by making mistakes or taking on or trying out identities that are not in accordance with one’s true nature.

It seems strange or even wrong to say that by changing one’s identity or taking on a different role, one suddenly lives according to one’s true self. This indeed identifies the true self with the me-self – the true self would be a specific role, identity, job, etc. – which seems counterintuitive; should the true self not be a deep self, the self-as-process? If I change my identity and consider the new identity my true self, it implies that the former identity was a false self. But was it not the case that one aspect of the true self is exactly an underlying identity, one that cannot change simply by changing from one’s surface identity to another? Without such an underlying identity it would not make sense to say that the former identity was a false self, because there is nothing to connect the two identities.

Indeed, the true self may be conceived of as that which unifies different conceptions of the more concrete selves (the me-selves) through a narrative ( Polkinghorne, 1991 ; Gallagher, 2000 ; Schechtman, 2011 ), where the variations and mistakes are not necessarily plain errors, but rather essential parts of the process. By manifesting a unity within the different conceptions of the me-self, the true self is also manifested. This manifestation is not necessarily tied to a specific identify, a me-self, being right or wrong, true or false. The measure of the degree of manifestation is the degree of unity created by the processual self-conception. Since the self is also influenced and potentially challenged by different cultures, ethical norms, and worldviews, the unity increases to the extent the different cultures are encompassed, i.e. to the extent that difference is recognized and integrated in the true self.