25 Thesis Statement Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

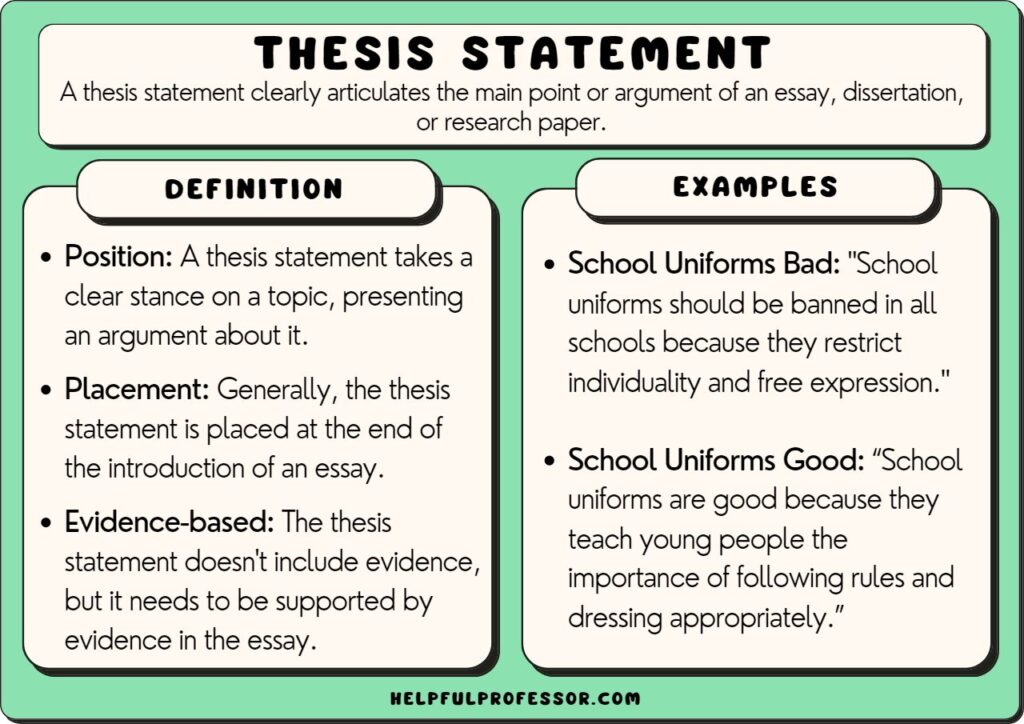

A thesis statement is needed in an essay or dissertation . There are multiple types of thesis statements – but generally we can divide them into expository and argumentative. An expository statement is a statement of fact (common in expository essays and process essays) while an argumentative statement is a statement of opinion (common in argumentative essays and dissertations). Below are examples of each.

Strong Thesis Statement Examples

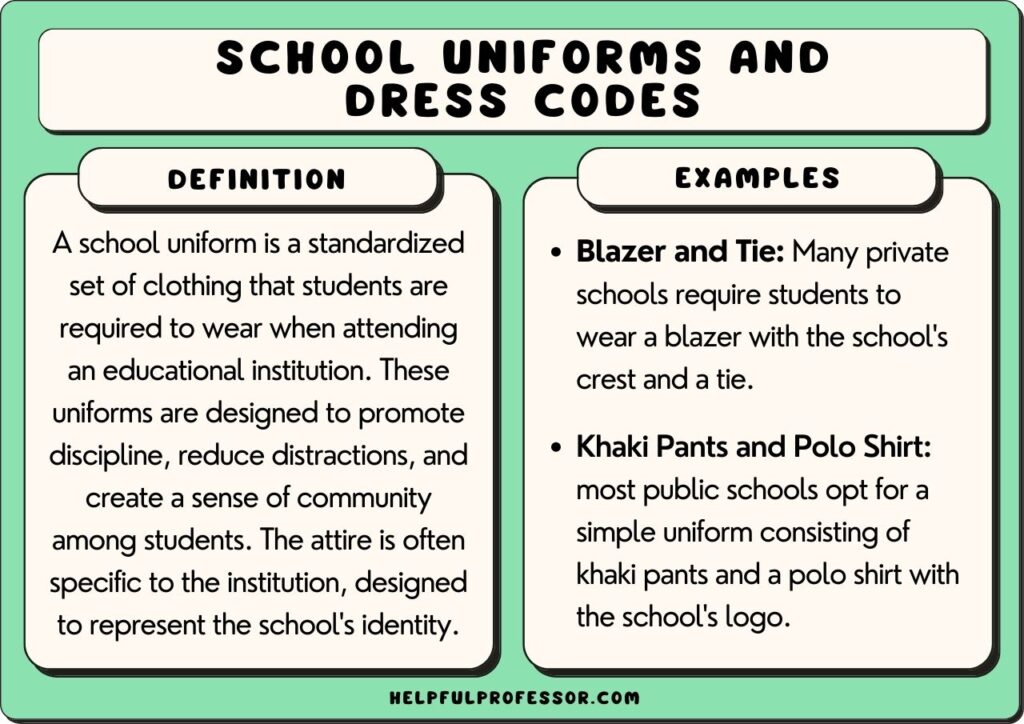

1. School Uniforms

“Mandatory school uniforms should be implemented in educational institutions as they promote a sense of equality, reduce distractions, and foster a focused and professional learning environment.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay or Debate

Read More: School Uniforms Pros and Cons

2. Nature vs Nurture

“This essay will explore how both genetic inheritance and environmental factors equally contribute to shaping human behavior and personality.”

Best For: Compare and Contrast Essay

Read More: Nature vs Nurture Debate

3. American Dream

“The American Dream, a symbol of opportunity and success, is increasingly elusive in today’s socio-economic landscape, revealing deeper inequalities in society.”

Best For: Persuasive Essay

Read More: What is the American Dream?

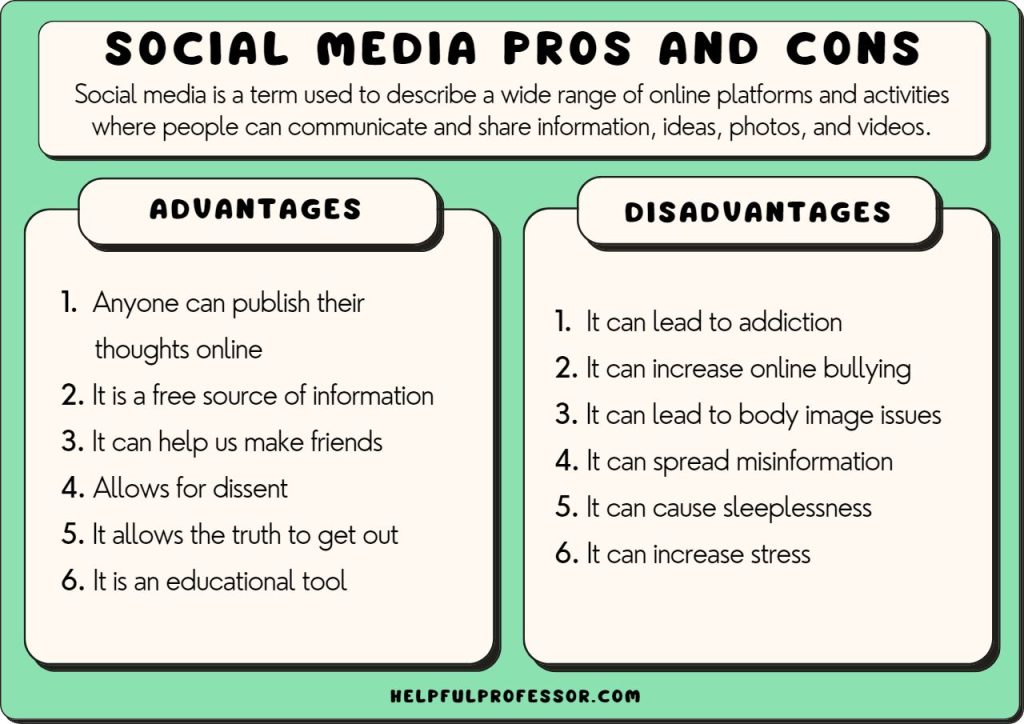

4. Social Media

“Social media has revolutionized communication and societal interactions, but it also presents significant challenges related to privacy, mental health, and misinformation.”

Best For: Expository Essay

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Social Media

5. Globalization

“Globalization has created a world more interconnected than ever before, yet it also amplifies economic disparities and cultural homogenization.”

Read More: Globalization Pros and Cons

6. Urbanization

“Urbanization drives economic growth and social development, but it also poses unique challenges in sustainability and quality of life.”

Read More: Learn about Urbanization

7. Immigration

“Immigration enriches receiving countries culturally and economically, outweighing any perceived social or economic burdens.”

Read More: Immigration Pros and Cons

8. Cultural Identity

“In a globalized world, maintaining distinct cultural identities is crucial for preserving cultural diversity and fostering global understanding, despite the challenges of assimilation and homogenization.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay

Read More: Learn about Cultural Identity

9. Technology

“Medical technologies in care institutions in Toronto has increased subjcetive outcomes for patients with chronic pain.”

Best For: Research Paper

10. Capitalism vs Socialism

“The debate between capitalism and socialism centers on balancing economic freedom and inequality, each presenting distinct approaches to resource distribution and social welfare.”

11. Cultural Heritage

“The preservation of cultural heritage is essential, not only for cultural identity but also for educating future generations, outweighing the arguments for modernization and commercialization.”

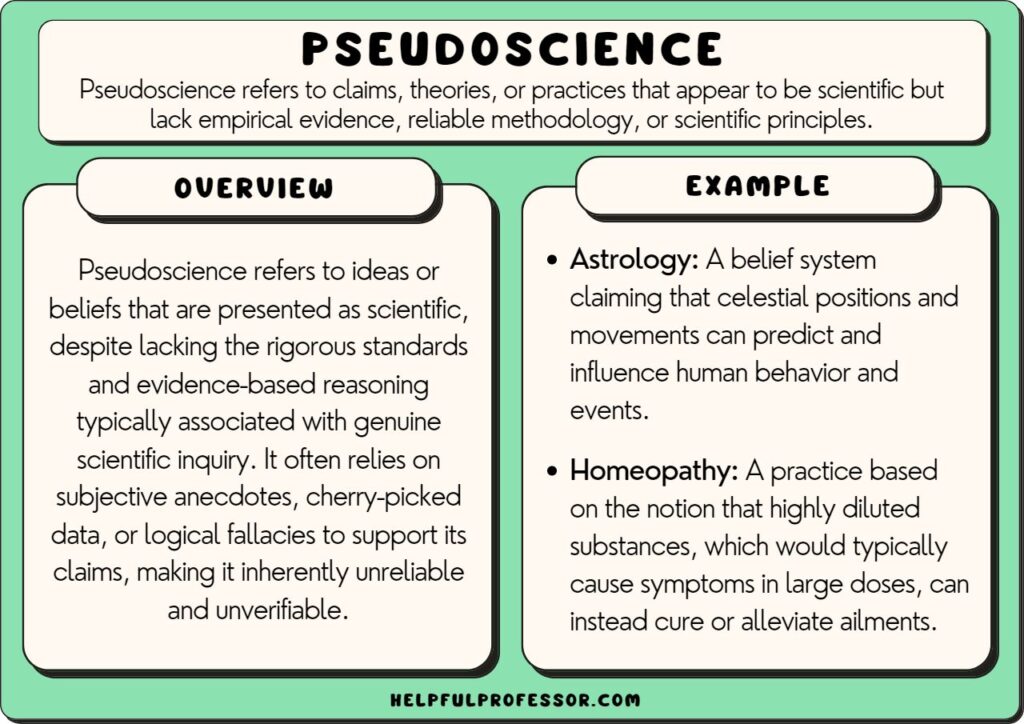

12. Pseudoscience

“Pseudoscience, characterized by a lack of empirical support, continues to influence public perception and decision-making, often at the expense of scientific credibility.”

Read More: Examples of Pseudoscience

13. Free Will

“The concept of free will is largely an illusion, with human behavior and decisions predominantly determined by biological and environmental factors.”

Read More: Do we have Free Will?

14. Gender Roles

“Traditional gender roles are outdated and harmful, restricting individual freedoms and perpetuating gender inequalities in modern society.”

Read More: What are Traditional Gender Roles?

15. Work-Life Ballance

“The trend to online and distance work in the 2020s led to improved subjective feelings of work-life balance but simultaneously increased self-reported loneliness.”

Read More: Work-Life Balance Examples

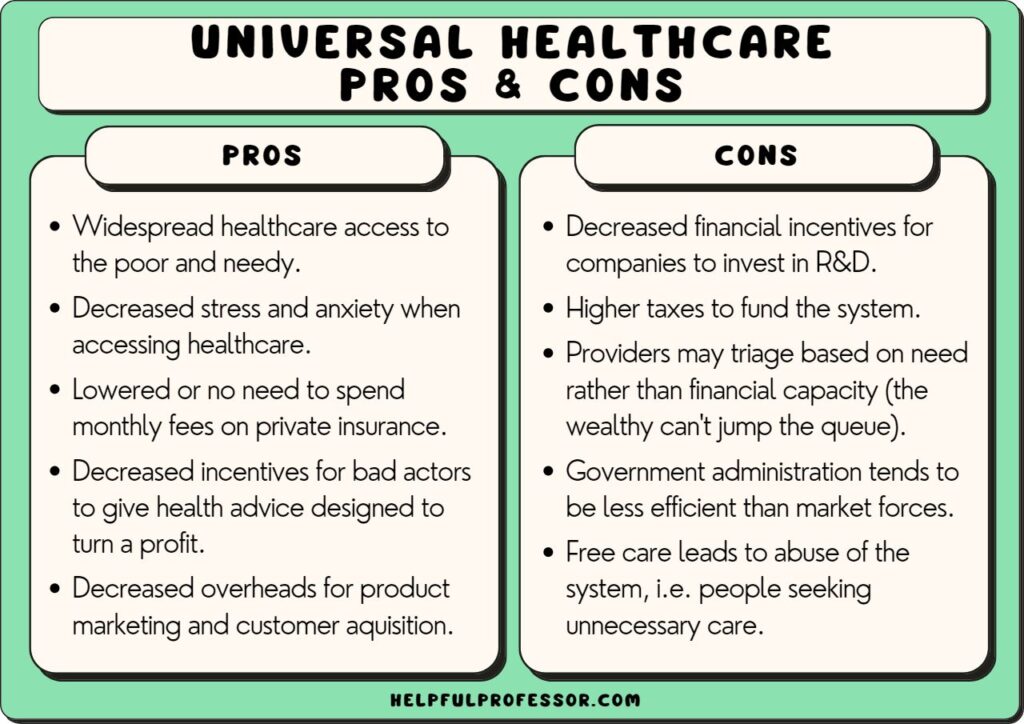

16. Universal Healthcare

“Universal healthcare is a fundamental human right and the most effective system for ensuring health equity and societal well-being, outweighing concerns about government involvement and costs.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Universal Healthcare

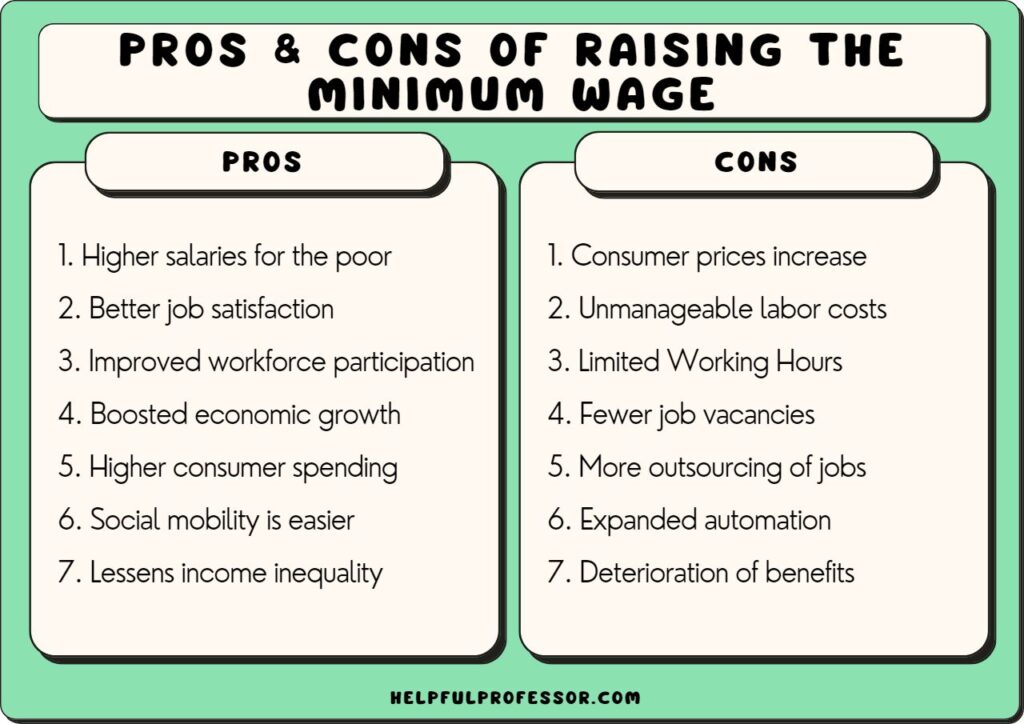

17. Minimum Wage

“The implementation of a fair minimum wage is vital for reducing economic inequality, yet it is often contentious due to its potential impact on businesses and employment rates.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Raising the Minimum Wage

18. Homework

“The homework provided throughout this semester has enabled me to achieve greater self-reflection, identify gaps in my knowledge, and reinforce those gaps through spaced repetition.”

Best For: Reflective Essay

Read More: Reasons Homework Should be Banned

19. Charter Schools

“Charter schools offer alternatives to traditional public education, promising innovation and choice but also raising questions about accountability and educational equity.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Charter Schools

20. Effects of the Internet

“The Internet has drastically reshaped human communication, access to information, and societal dynamics, generally with a net positive effect on society.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of the Internet

21. Affirmative Action

“Affirmative action is essential for rectifying historical injustices and achieving true meritocracy in education and employment, contrary to claims of reverse discrimination.”

Best For: Essay

Read More: Affirmative Action Pros and Cons

22. Soft Skills

“Soft skills, such as communication and empathy, are increasingly recognized as essential for success in the modern workforce, and therefore should be a strong focus at school and university level.”

Read More: Soft Skills Examples

23. Moral Panic

“Moral panic, often fueled by media and cultural anxieties, can lead to exaggerated societal responses that sometimes overlook rational analysis and evidence.”

Read More: Moral Panic Examples

24. Freedom of the Press

“Freedom of the press is critical for democracy and informed citizenship, yet it faces challenges from censorship, media bias, and the proliferation of misinformation.”

Read More: Freedom of the Press Examples

25. Mass Media

“Mass media shapes public opinion and cultural norms, but its concentration of ownership and commercial interests raise concerns about bias and the quality of information.”

Best For: Critical Analysis

Read More: Mass Media Examples

Checklist: How to use your Thesis Statement

✅ Position: If your statement is for an argumentative or persuasive essay, or a dissertation, ensure it takes a clear stance on the topic. ✅ Specificity: It addresses a specific aspect of the topic, providing focus for the essay. ✅ Conciseness: Typically, a thesis statement is one to two sentences long. It should be concise, clear, and easily identifiable. ✅ Direction: The thesis statement guides the direction of the essay, providing a roadmap for the argument, narrative, or explanation. ✅ Evidence-based: While the thesis statement itself doesn’t include evidence, it sets up an argument that can be supported with evidence in the body of the essay. ✅ Placement: Generally, the thesis statement is placed at the end of the introduction of an essay.

Try These AI Prompts – Thesis Statement Generator!

One way to brainstorm thesis statements is to get AI to brainstorm some for you! Try this AI prompt:

💡 AI PROMPT FOR EXPOSITORY THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTUCTIONS]. I want you to create an expository thesis statement that doesn’t argue a position, but demonstrates depth of knowledge about the topic.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR ARGUMENTATIVE THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTRUCTIONS]. I want you to create an argumentative thesis statement that clearly takes a position on this issue.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR COMPARE AND CONTRAST THESIS STATEMENT I am writing a compare and contrast essay that compares [Concept 1] and [Concept2]. Give me 5 potential single-sentence thesis statements that remain objective.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Number Games for Kids (Free and Easy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Word Games for Kids (Free and Easy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Outdoor Games for Kids

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 50 Incentives to Give to Students

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on January 11, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on August 15, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . It usually comes near the end of your introduction .

Your thesis will look a bit different depending on the type of essay you’re writing. But the thesis statement should always clearly state the main idea you want to get across. Everything else in your essay should relate back to this idea.

You can write your thesis statement by following four simple steps:

- Start with a question

- Write your initial answer

- Develop your answer

- Refine your thesis statement

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a thesis statement, placement of the thesis statement, step 1: start with a question, step 2: write your initial answer, step 3: develop your answer, step 4: refine your thesis statement, types of thesis statements, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about thesis statements.

A thesis statement summarizes the central points of your essay. It is a signpost telling the reader what the essay will argue and why.

The best thesis statements are:

- Concise: A good thesis statement is short and sweet—don’t use more words than necessary. State your point clearly and directly in one or two sentences.

- Contentious: Your thesis shouldn’t be a simple statement of fact that everyone already knows. A good thesis statement is a claim that requires further evidence or analysis to back it up.

- Coherent: Everything mentioned in your thesis statement must be supported and explained in the rest of your paper.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The thesis statement generally appears at the end of your essay introduction or research paper introduction .

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts and among young people more generally is hotly debated. For many who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education: the internet facilitates easier access to information, exposure to different perspectives, and a flexible learning environment for both students and teachers.

You should come up with an initial thesis, sometimes called a working thesis , early in the writing process . As soon as you’ve decided on your essay topic , you need to work out what you want to say about it—a clear thesis will give your essay direction and structure.

You might already have a question in your assignment, but if not, try to come up with your own. What would you like to find out or decide about your topic?

For example, you might ask:

After some initial research, you can formulate a tentative answer to this question. At this stage it can be simple, and it should guide the research process and writing process .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Now you need to consider why this is your answer and how you will convince your reader to agree with you. As you read more about your topic and begin writing, your answer should get more detailed.

In your essay about the internet and education, the thesis states your position and sketches out the key arguments you’ll use to support it.

The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education because it facilitates easier access to information.

In your essay about braille, the thesis statement summarizes the key historical development that you’ll explain.

The invention of braille in the 19th century transformed the lives of blind people, allowing them to participate more actively in public life.

A strong thesis statement should tell the reader:

- Why you hold this position

- What they’ll learn from your essay

- The key points of your argument or narrative

The final thesis statement doesn’t just state your position, but summarizes your overall argument or the entire topic you’re going to explain. To strengthen a weak thesis statement, it can help to consider the broader context of your topic.

These examples are more specific and show that you’ll explore your topic in depth.

Your thesis statement should match the goals of your essay, which vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing:

- In an argumentative essay , your thesis statement should take a strong position. Your aim in the essay is to convince your reader of this thesis based on evidence and logical reasoning.

- In an expository essay , you’ll aim to explain the facts of a topic or process. Your thesis statement doesn’t have to include a strong opinion in this case, but it should clearly state the central point you want to make, and mention the key elements you’ll explain.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

Follow these four steps to come up with a thesis statement :

- Ask a question about your topic .

- Write your initial answer.

- Develop your answer by including reasons.

- Refine your answer, adding more detail and nuance.

The thesis statement should be placed at the end of your essay introduction .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, August 15). How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/thesis-statement/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Thesis Statement–Examples

What is a thesis statement? A thesis statement summarizes the main idea of a paper or an essay. Similar to the statement of the problem in research, it prepares the reader for what is to come and ties together the evidence and examples that are presented and the arguments and claims that are made later.

A good thesis statement can provoke thought, arouse interest, and is always followed up by exactly what it promises—if the focus or direction of your essay changes over time, you should go back to your statement and adapt it as well so that it clearly reflects what you are explaining or discussing.

Where does the thesis statement go in my paper?

Your thesis statement should be placed near the end of your introduction—after you have given the reader some background and before you delve into the specific evidence or arguments that support your statement.

Can you give me a thesis statement template?

Depending on the type of essay you are writing, your thesis statement will look different. The important thing is that your statement is specific and clearly states the main idea you want to get across. In the following, we will discuss different types of statements, show you a simple 4-step process for writing an effective thesis statement, and finish off with some not-so-good and good thesis statement examples.

Table of Contents:

- Types of Thesis Statements

- How to Write a Thesis Statement Step by Step

- Not-So-Good and Good Thesis Statements

Types of Thesis Statements

Depending on whether your paper is analytical, expository, or argumentative, your statement has a slightly different purpose.

Analytical thesis statements

An analytical paper breaks down an issue or an idea into its components, evaluates the pieces, and presents an evaluation of this breakdown to the reader. Such papers can analyze art, music, literature, current or historical events, political ideas, or scientific research. An analytical thesis statement is therefore often the result of such an analysis of, for example, some literary work (“Heathcliff is meant to be seen as a hero rather than a horrible person”) or a process (“the main challenge recruiters face is the balance between selecting the best candidates and hiring them before they are snatched up by competitors”), or even the latest research (“starving yourself will increase your lifespan, according to science”). In the rest of the paper, you then need to explain how you did the analysis that led you to the stated result and how you arrived at your conclusion, by presenting data and evidence.

Expository thesis statements

An expository (explanatory) paper explains something to the audience, such as a historical development, a current phenomenon, or the effect of political intervention. A typical explanatory thesis statement is therefore often a “topic statement” rather than a claim or actual thesis. An expository essay could, for example, explain “where human rights came from and how they changed the world,” or “how students make career choices.” The rest of the paper then needs to present the reader with all the relevant information on the topic, covering all sides and aspects rather than one specific viewpoint.

Argumentative thesis statements

An argumentative paper makes a clear and potentially very subjective claim and follows up with a justification based on evidence. The claim could be an opinion, a policy proposal, an evaluation, or an interpretation. The goal of the argumentative paper is to convince the audience that the author’s claim is true. A thesis statement for such a paper could be that “every student should be required to take a gap year after high school to gain some life experience”, or that “vaccines should be mandatory”. Argumentative thesis statements can be bold, assertive, and one-sided—you have the rest of the paper to convince the reader that you have good reasons to think that way and that maybe they should think like that, too.

How to Write a Thesis Statement Step-by-Step

If you are not quite sure how you get from a topic to a thesis statement, then follow this simple process—but make sure you know what type of essay you are supposed to write and adapt the steps to the kind of statement you need.

First , you will have to select a topic . This might have been done for you already if you are writing an essay as part of a class. If not, then make sure you don’t start too general—narrow the subject down to a specific aspect that you can cover in an essay.

Second , ask yourself a question about your topic, one that you are personally interested in or one that you think your readers might find relevant or interesting. Here, you have to consider whether you are going to explain something to the reader (expository essay) or if you want to put out your own, potentially controversial, opinion and then argue for it in the rest of your (argumentative) essay.

Third , answer the question you raised for yourself, based on the material you have already sifted through and are planning to present to the reader or the opinion you have already formed on the topic. If your opinion changes while working on your essay, which happens quite often, then make sure you come back to this process and adapt your statement.

Fourth and last, reword the answer to your question into a concise statement . You want the reader to know exactly what is coming, and you also want to make it sound as interesting as possible so that they decide to keep reading.

Let’s look at this example process to give you a better idea of how to get from your topic to your statement. Note that this is the development of a thesis statement for an argumentative essay .

- Choose a specific topic: Covid-19 vaccines

Narrow it down to a specific aspect: opposition to Covid-19 vaccines

- Ask a question: Should vaccination against Covid-19 be mandatory?

- Answer the question for yourself, by sorting through the available evidence/arguments:

Yes: vaccination protects other, more vulnerable people; vaccination reduces the spread of the disease; herd immunity will allow societies to go back to normal…

No: vaccines can have side-effects in some people; the vaccines have been developed too fast and there might be unknown risks; the government should stay out of personal decisions on people’s health…

- Form your opinion and reword it into your thesis statement that represents a very short summary of the key points you base your claim on:

While there is some hesitancy around vaccinations against Covid-19, most of the presented arguments revolve around unfounded fears and the individual freedom to make one’s own decisions. Since that freedom is offset by the benefits of mass vaccination, governments should make vaccines mandatory to help societies get back to normal.

This is a good argumentative thesis statement example because it does not just present a fact that everybody knows and agrees on, but a claim that is debatable and needs to be backed up by data and arguments, which you will do in the rest of your essay. You can introduce whatever evidence and arguments you deem necessary in the following—but make sure that all your points lead back to your core claim and support your opinion. This example also answers the question “how long should a thesis statement be?” One or two sentences are generally enough. If your statement is longer, make sure you are not using vague, empty expressions or more words than necessary .

Good and Bad Thesis Statement Examples

Not-so-good thesis statement : Everyone should get vaccinated against Covid-19.

Problem: The statement does not specify why that might be relevant or why people might not want to do it—this is too vague to spark anyone’s interest.

Good : Since the risks of the currently available Covid-19 vaccines are minimal and societal interests outweigh individual freedom, governments should make Covid-19 vaccination mandatory.

Not-so-good thesis statement : Binge drinking is bad for your health.

Problem: This is a very broad statement that everyone can agree on and nobody needs to read an article on. You need to specify why anyone would not think that way.

Good : Binge drinking has become a trend among college students. While some argue that it might be better for your health than regular consumption of low amounts of alcohol, science says otherwise.

Not-so-good thesis statement : Learning an instrument can develop a child’s cognitive abilities.

Problem: This is a very weak statement—”can” develop doesn’t tell us whether that is what happens in every child, what kind of effects of music education on cognition we can expect, and whether that has or should have any practical implications.

Good thesis statement : Music education has many surprising benefits on children’s overall development, including effects on language acquisition, coordination, problem-solving, and even social skills.

You could now present all the evidence on the specific effects of music education on children’s specific abilities in the rest of your (expository) essay. You could also turn this into an argumentative essay, by adding your own opinion to your statement:

Good thesis statement : Considering the many surprising benefits that music education has on children’s overall development, every child should be given the opportunity to learn an instrument as part of their public school education.

Not-so-good thesis statement : Outer space exploration is a waste of money.

Problem: While this is a clear statement of your personal opinion that people could potentially disagree with (which is good for an argumentative thesis statement), it lacks context and does not really tell the reader what to expect from your essay.

Good thesis statement : Instead of wasting money on exploring outer space, people like Elon Musk should use their wealth to solve poverty, hunger, global warming, and other issues we are facing on this earth.

Get Professional Thesis Editing Services

Now that you know how to write the perfect thesis statement for your essay, you might be interested in our Wordvice AI Proofreader . And after drafting your academic papers, be sure to get proofreading that includes manuscript editing , thesis editing , or dissertation editing services before submitting your work to journals for publication.

We have many more articles for you on all aspects of academic writing , tips and tricks on how to avoid common grammar mistakes , and resources on how to strengthen your writing style in general.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement: 4 Steps + Examples

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of a thesis statement, writing a good thesis statement: 4 steps, common pitfalls to avoid, where to get your essay edited for free.

When you set out to write an essay, there has to be some kind of point to it, right? Otherwise, your essay would just be a big jumble of word salad that makes absolutely no sense. An essay needs a central point that ties into everything else. That main point is called a thesis statement, and it’s the core of any essay or research paper.

You may hear about Master degree candidates writing a thesis, and that is an entire paper–not to be confused with the thesis statement, which is typically one sentence that contains your paper’s focus.

Read on to learn more about thesis statements and how to write them. We’ve also included some solid examples for you to reference.

Typically the last sentence of your introductory paragraph, the thesis statement serves as the roadmap for your essay. When your reader gets to the thesis statement, they should have a clear outline of your main point, as well as the information you’ll be presenting in order to either prove or support your point.

The thesis statement should not be confused for a topic sentence , which is the first sentence of every paragraph in your essay. If you need help writing topic sentences, numerous resources are available. Topic sentences should go along with your thesis statement, though.

Since the thesis statement is the most important sentence of your entire essay or paper, it’s imperative that you get this part right. Otherwise, your paper will not have a good flow and will seem disjointed. That’s why it’s vital not to rush through developing one. It’s a methodical process with steps that you need to follow in order to create the best thesis statement possible.

Step 1: Decide what kind of paper you’re writing

When you’re assigned an essay, there are several different types you may get. Argumentative essays are designed to get the reader to agree with you on a topic. Informative or expository essays present information to the reader. Analytical essays offer up a point and then expand on it by analyzing relevant information. Thesis statements can look and sound different based on the type of paper you’re writing. For example:

- Argumentative: The United States needs a viable third political party to decrease bipartisanship, increase options, and help reduce corruption in government.

- Informative: The Libertarian party has thrown off elections before by gaining enough support in states to get on the ballot and by taking away crucial votes from candidates.

- Analytical: An analysis of past presidential elections shows that while third party votes may have been the minority, they did affect the outcome of the elections in 2020, 2016, and beyond.

Step 2: Figure out what point you want to make

Once you know what type of paper you’re writing, you then need to figure out the point you want to make with your thesis statement, and subsequently, your paper. In other words, you need to decide to answer a question about something, such as:

- What impact did reality TV have on American society?

- How has the musical Hamilton affected perception of American history?

- Why do I want to major in [chosen major here]?

If you have an argumentative essay, then you will be writing about an opinion. To make it easier, you may want to choose an opinion that you feel passionate about so that you’re writing about something that interests you. For example, if you have an interest in preserving the environment, you may want to choose a topic that relates to that.

If you’re writing your college essay and they ask why you want to attend that school, you may want to have a main point and back it up with information, something along the lines of:

“Attending Harvard University would benefit me both academically and professionally, as it would give me a strong knowledge base upon which to build my career, develop my network, and hopefully give me an advantage in my chosen field.”

Step 3: Determine what information you’ll use to back up your point

Once you have the point you want to make, you need to figure out how you plan to back it up throughout the rest of your essay. Without this information, it will be hard to either prove or argue the main point of your thesis statement. If you decide to write about the Hamilton example, you may decide to address any falsehoods that the writer put into the musical, such as:

“The musical Hamilton, while accurate in many ways, leaves out key parts of American history, presents a nationalist view of founding fathers, and downplays the racism of the times.”

Once you’ve written your initial working thesis statement, you’ll then need to get information to back that up. For example, the musical completely leaves out Benjamin Franklin, portrays the founding fathers in a nationalist way that is too complimentary, and shows Hamilton as a staunch abolitionist despite the fact that his family likely did own slaves.

Step 4: Revise and refine your thesis statement before you start writing

Read through your thesis statement several times before you begin to compose your full essay. You need to make sure the statement is ironclad, since it is the foundation of the entire paper. Edit it or have a peer review it for you to make sure everything makes sense and that you feel like you can truly write a paper on the topic. Once you’ve done that, you can then begin writing your paper.

When writing a thesis statement, there are some common pitfalls you should avoid so that your paper can be as solid as possible. Make sure you always edit the thesis statement before you do anything else. You also want to ensure that the thesis statement is clear and concise. Don’t make your reader hunt for your point. Finally, put your thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph and have your introduction flow toward that statement. Your reader will expect to find your statement in its traditional spot.

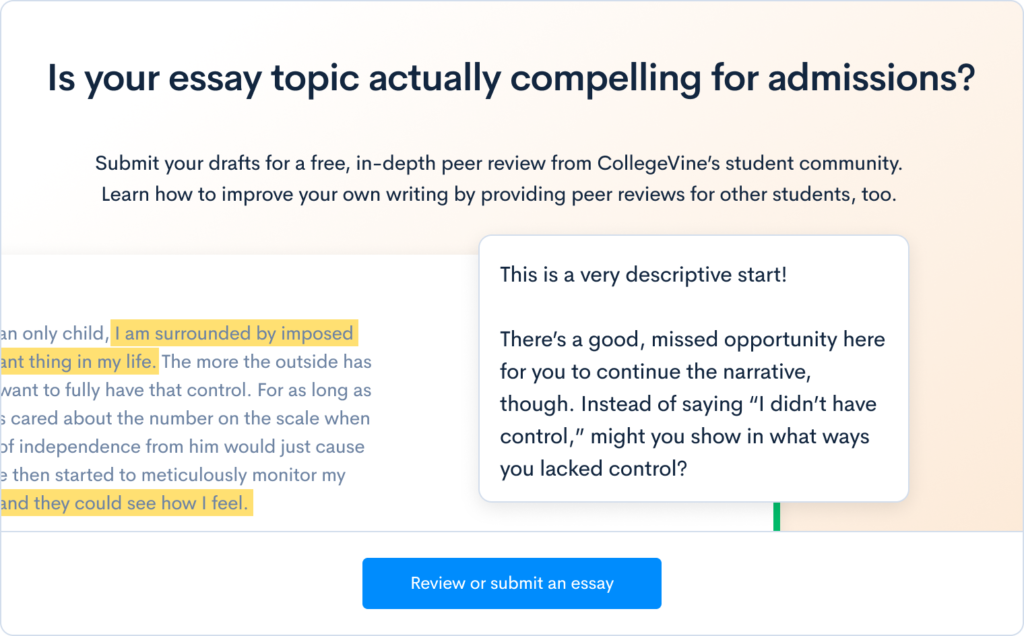

If you’re having trouble getting started, or need some guidance on your essay, there are tools available that can help you. CollegeVine offers a free peer essay review tool where one of your peers can read through your essay and provide you with valuable feedback. Getting essay feedback from a peer can help you wow your instructor or college admissions officer with an impactful essay that effectively illustrates your point.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

25 Thesis Statement Examples That Will Make Writing a Breeze

Understanding what makes a good thesis statement is one of the major keys to writing a great research paper or argumentative essay. The thesis statement is where you make a claim that will guide you through your entire paper. If you find yourself struggling to make sense of your paper or your topic, then it's likely due to a weak thesis statement.

Let's take a minute to first understand what makes a solid thesis statement, and what key components you need to write one of your own.

A thesis statement always goes at the beginning of the paper. It will typically be in the first couple of paragraphs of the paper so that it can introduce the body paragraphs, which are the supporting evidence for your thesis statement.

Your thesis statement should clearly identify an argument. You need to have a statement that is not only easy to understand, but one that is debatable. What that means is that you can't just put any statement of fact and have it be your thesis. For example, everyone knows that puppies are cute . An ineffective thesis statement would be, "Puppies are adorable and everyone knows it." This isn't really something that's a debatable topic.

Something that would be more debatable would be, "A puppy's cuteness is derived from its floppy ears, small body, and playfulness." These are three things that can be debated on. Some people might think that the cutest thing about puppies is the fact that they follow you around or that they're really soft and fuzzy.

All cuteness aside, you want to make sure that your thesis statement is not only debatable, but that it also actually thoroughly answers the research question that was posed. You always want to make sure that your evidence is supporting a claim that you made (and not the other way around). This is why it's crucial to read and research about a topic first and come to a conclusion later. If you try to get your research to fit your thesis statement, then it may not work out as neatly as you think. As you learn more, you discover more (and the outcome may not be what you originally thought).

Additionally, your thesis statement shouldn't be too big or too grand. It'll be hard to cover everything in a thesis statement like, "The federal government should act now on climate change." The topic is just too large to actually say something new and meaningful. Instead, a more effective thesis statement might be, "Local governments can combat climate change by providing citizens with larger recycling bins and offering local classes about composting and conservation." This is easier to work with because it's a smaller idea, but you can also discuss the overall topic that you might be interested in, which is climate change.

So, now that we know what makes a good, solid thesis statement, you can start to write your own. If you find that you're getting stuck or you are the type of person who needs to look at examples before you start something, then check out our list of thesis statement examples below.

Thesis statement examples

A quick note that these thesis statements have not been fully researched. These are merely examples to show you what a thesis statement might look like and how you can implement your own ideas into one that you think of independently. As such, you should not use these thesis statements for your own research paper purposes. They are meant to be used as examples only.

- Vaccinations Because many children are unable to vaccinate due to illness, we must require that all healthy and able children be vaccinated in order to have herd immunity.

- Educational Resources for Low-Income Students Schools should provide educational resources for low-income students during the summers so that they don't forget what they've learned throughout the school year.

- School Uniforms School uniforms may be an upfront cost for families, but they eradicate the visual differences in income between students and provide a more egalitarian atmosphere at school.

- Populism The rise in populism on the 2016 political stage was in reaction to increasing globalization, the decline of manufacturing jobs, and the Syrian refugee crisis.

- Public Libraries Libraries are essential resources for communities and should be funded more heavily by local municipalities.

- Cyber Bullying With more and more teens using smartphones and social media, cyber bullying is on the rise. Cyber bullying puts a lot of stress on many teens, and can cause depression, anxiety, and even suicidal thoughts. Parents should limit the usage of smart phones, monitor their children's online activity, and report any cyber bullying to school officials in order to combat this problem.

- Medical Marijuana for Veterans Studies have shown that the use of medicinal marijuana has been helpful to veterans who suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Medicinal marijuana prescriptions should be legal in all states and provided to these veterans. Additional medical or therapy services should also be researched and implemented in order to help them re-integrate back into civilian life.

- Work-Life Balance Corporations should provide more work from home opportunities and six-hour workdays so that office workers have a better work-life balance and are more likely to be productive when they are in the office.

- Teaching Youths about Consensual Sex Although sex education that includes a discussion of consensual sex would likely lead to less sexual assault, parents need to teach their children the meaning of consent from a young age with age appropriate lessons.

- Whether or Not to Attend University A degree from a university provides invaluable lessons on life and a future career, but not every high school student should be encouraged to attend a university directly after graduation. Some students may benefit from a trade school or a "gap year" where they can think more intensely about what it is they want to do for a career and how they can accomplish this.

- Studying Abroad Studying abroad is one of the most culturally valuable experiences you can have in college. It is the only way to get completely immersed in another language and learn how other cultures and countries are different from your own.

- Women's Body Image Magazines have done a lot in the last five years to include a more diverse group of models, but there is still a long way to go to promote a healthy woman's body image collectively as a culture.

- Cigarette Tax Heavily taxing and increasing the price of cigarettes is essentially a tax on the poorest Americans, and it doesn't deter them from purchasing. Instead, the state and federal governments should target those economically disenfranchised with early education about the dangers of smoking.

- Veganism A vegan diet, while a healthy and ethical way to consume food, indicates a position of privilege. It also limits you to other cultural food experiences if you travel around the world.

- University Athletes Should be Compensated University athletes should be compensated for their service to the university, as it is difficult for these students to procure and hold a job with busy academic and athletic schedules. Many student athletes on scholarship also come from low-income neighborhoods and it is a struggle to make ends meet when they are participating in athletics.

- Women in the Workforce Sheryl Sandberg makes a lot of interesting points in her best-selling book, Lean In , but she only addressed the very privileged working woman and failed to speak to those in lower-skilled, lower-wage jobs.

- Assisted Suicide Assisted suicide should be legal and doctors should have the ability to make sure their patients have the end-of-life care that they want to receive.

- Celebrity and Political Activism Although Taylor Swift's lyrics are indicative of a feminist perspective, she should be more politically active and vocal to use her position of power for the betterment of society.

- The Civil War The insistence from many Southerners that the South seceded from the Union for states' rights versus the fact that they seceded for the purposes of continuing slavery is a harmful myth that still affects race relations today.

- Blue Collar Workers Coal miners and other blue-collar workers whose jobs are slowly disappearing from the workforce should be re-trained in jobs in the technology sector or in renewable energy. A program to re-train these workers would not only improve local economies where jobs have been displaced, but would also lead to lower unemployment nationally.

- Diversity in the Workforce Having a diverse group of people in an office setting leads to richer ideas, more cooperation, and more empathy between people with different skin colors or backgrounds.

- Re-Imagining the Nuclear Family The nuclear family was traditionally defined as one mother, one father, and 2.5 children. This outdated depiction of family life doesn't quite fit with modern society. The definition of normal family life shouldn't be limited to two-parent households.

- Digital Literacy Skills With more information readily available than ever before, it's crucial that students are prepared to examine the material they're reading and determine whether or not it's a good source or if it has misleading information. Teaching students digital literacy and helping them to understand the difference between opinion or propaganda from legitimate, real information is integral.

- Beauty Pageants Beauty pageants are presented with the angle that they empower women. However, putting women in a swimsuit on a stage while simultaneously judging them on how well they answer an impossible question in a short period of time is cruel and purely for the amusement of men. Therefore, we should stop televising beauty pageants.

- Supporting More Women to Run for a Political Position In order to get more women into political positions, more women must run for office. There must be a grassroots effort to educate women on how to run for office, who among them should run, and support for a future candidate for getting started on a political career.

Still stuck? Need some help with your thesis statement?

If you are still uncertain about how to write a thesis statement or what a good thesis statement is, be sure to consult with your teacher or professor to make sure you're on the right track. It's always a good idea to check in and make sure that your thesis statement is making a solid argument and that it can be supported by your research.

After you're done writing, it's important to have someone take a second look at your paper so that you can ensure there are no mistakes or errors. It's difficult to spot your own mistakes, which is why it's always recommended to have someone help you with the revision process, whether that's a teacher, the writing center at school, or a professional editor such as one from ServiceScape .

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

How to write a thesis statement, what is a thesis statement.

Almost all of us—even if we don’t do it consciously—look early in an essay for a one- or two-sentence condensation of the argument or analysis that is to follow. We refer to that condensation as a thesis statement.

Why Should Your Essay Contain a Thesis Statement?

- to test your ideas by distilling them into a sentence or two

- to better organize and develop your argument

- to provide your reader with a “guide” to your argument

In general, your thesis statement will accomplish these goals if you think of the thesis as the answer to the question your paper explores.

How Can You Write a Good Thesis Statement?

Here are some helpful hints to get you started. You can either scroll down or select a link to a specific topic.

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned

Almost all assignments, no matter how complicated, can be reduced to a single question. Your first step, then, is to distill the assignment into a specific question. For example, if your assignment is, “Write a report to the local school board explaining the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class,” turn the request into a question like, “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” After you’ve chosen the question your essay will answer, compose one or two complete sentences answering that question.

Q: “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” A: “The potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class are . . .”

A: “Using computers in a fourth-grade class promises to improve . . .”

The answer to the question is the thesis statement for the essay.

[ Back to top ]

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned

Even if your assignment doesn’t ask a specific question, your thesis statement still needs to answer a question about the issue you’d like to explore. In this situation, your job is to figure out what question you’d like to write about.

A good thesis statement will usually include the following four attributes:

- take on a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree

- deal with a subject that can be adequately treated given the nature of the assignment

- express one main idea

- assert your conclusions about a subject

Let’s see how to generate a thesis statement for a social policy paper.

Brainstorm the topic . Let’s say that your class focuses upon the problems posed by changes in the dietary habits of Americans. You find that you are interested in the amount of sugar Americans consume.

You start out with a thesis statement like this:

Sugar consumption.

This fragment isn’t a thesis statement. Instead, it simply indicates a general subject. Furthermore, your reader doesn’t know what you want to say about sugar consumption.

Narrow the topic . Your readings about the topic, however, have led you to the conclusion that elementary school children are consuming far more sugar than is healthy.

You change your thesis to look like this:

Reducing sugar consumption by elementary school children.

This fragment not only announces your subject, but it focuses on one segment of the population: elementary school children. Furthermore, it raises a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree, because while most people might agree that children consume more sugar than they used to, not everyone would agree on what should be done or who should do it. You should note that this fragment is not a thesis statement because your reader doesn’t know your conclusions on the topic.

Take a position on the topic. After reflecting on the topic a little while longer, you decide that what you really want to say about this topic is that something should be done to reduce the amount of sugar these children consume.

You revise your thesis statement to look like this:

More attention should be paid to the food and beverage choices available to elementary school children.

This statement asserts your position, but the terms more attention and food and beverage choices are vague.

Use specific language . You decide to explain what you mean about food and beverage choices , so you write:

Experts estimate that half of elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar.

This statement is specific, but it isn’t a thesis. It merely reports a statistic instead of making an assertion.

Make an assertion based on clearly stated support. You finally revise your thesis statement one more time to look like this:

Because half of all American elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar, schools should be required to replace the beverages in soda machines with healthy alternatives.

Notice how the thesis answers the question, “What should be done to reduce sugar consumption by children, and who should do it?” When you started thinking about the paper, you may not have had a specific question in mind, but as you became more involved in the topic, your ideas became more specific. Your thesis changed to reflect your new insights.

How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

1. a strong thesis statement takes some sort of stand..

Remember that your thesis needs to show your conclusions about a subject. For example, if you are writing a paper for a class on fitness, you might be asked to choose a popular weight-loss product to evaluate. Here are two thesis statements:

There are some negative and positive aspects to the Banana Herb Tea Supplement.

This is a weak thesis statement. First, it fails to take a stand. Second, the phrase negative and positive aspects is vague.

Because Banana Herb Tea Supplement promotes rapid weight loss that results in the loss of muscle and lean body mass, it poses a potential danger to customers.

This is a strong thesis because it takes a stand, and because it's specific.

2. A strong thesis statement justifies discussion.

Your thesis should indicate the point of the discussion. If your assignment is to write a paper on kinship systems, using your own family as an example, you might come up with either of these two thesis statements:

My family is an extended family.

This is a weak thesis because it merely states an observation. Your reader won’t be able to tell the point of the statement, and will probably stop reading.

While most American families would view consanguineal marriage as a threat to the nuclear family structure, many Iranian families, like my own, believe that these marriages help reinforce kinship ties in an extended family.

This is a strong thesis because it shows how your experience contradicts a widely-accepted view. A good strategy for creating a strong thesis is to show that the topic is controversial. Readers will be interested in reading the rest of the essay to see how you support your point.

3. A strong thesis statement expresses one main idea.

Readers need to be able to see that your paper has one main point. If your thesis statement expresses more than one idea, then you might confuse your readers about the subject of your paper. For example:

Companies need to exploit the marketing potential of the Internet, and Web pages can provide both advertising and customer support.

This is a weak thesis statement because the reader can’t decide whether the paper is about marketing on the Internet or Web pages. To revise the thesis, the relationship between the two ideas needs to become more clear. One way to revise the thesis would be to write:

Because the Internet is filled with tremendous marketing potential, companies should exploit this potential by using Web pages that offer both advertising and customer support.

This is a strong thesis because it shows that the two ideas are related. Hint: a great many clear and engaging thesis statements contain words like because , since , so , although , unless , and however .

4. A strong thesis statement is specific.

A thesis statement should show exactly what your paper will be about, and will help you keep your paper to a manageable topic. For example, if you're writing a seven-to-ten page paper on hunger, you might say:

World hunger has many causes and effects.

This is a weak thesis statement for two major reasons. First, world hunger can’t be discussed thoroughly in seven to ten pages. Second, many causes and effects is vague. You should be able to identify specific causes and effects. A revised thesis might look like this:

Hunger persists in Glandelinia because jobs are scarce and farming in the infertile soil is rarely profitable.

This is a strong thesis statement because it narrows the subject to a more specific and manageable topic, and it also identifies the specific causes for the existence of hunger.

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Career Planning

- Finding a Job

How To Use a Thesis Statement for Employment

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ADHeadshot-Cropped-b80e40469d5b4852a68f94ad69d6e8bd.jpg)

What Is a Thesis Statement for Employment?

How a thesis statement for employment works, examples of a thesis statement for employment.

Think back to when you learned to write an essay. Most likely, your teacher talked about the importance of a thesis statement, which sums up your essay. A thesis statement can also be helpful during a job search.

Through a thesis statement, you can clarify your background as a candidate, what you want in a role, and how you'd fit in at a given company. This is, of course, valuable information for recruiters and hiring managers.

A thesis statement for employment is a brief description of yourself, your characteristics, and your skills.

Your thesis statement for employment is used to demonstrate your interest in a job and show how you would benefit an organization. Learn how to go about developing one.

Key Takeaways

- A thesis statement for employment is a brief description of yourself, your characteristics, and your skills. It’s used to show how you would benefit an organization.

- You can use your thesis statement on your resume, in cover letters, in interviews, and during networking events.

- A thesis statement should be brief, direct, and tailored to each position you apply for.

A thesis statement for employment is a one- or two-sentence statement of your qualifications.

Crafting this statement may take some time and thought. (That was likely true back when you were routinely writing essays, too.) Once you have developed a thesis statement, it'll come in handy at many points in your job search. You can use it:

- Within your cover letters —place your thesis statement in the first paragraph, where you explain why you're applying for the role.

- On your resume —include the thesis statement in your objective or summary section.

- During job interviews —to help explain why you're the right person for the job.

- When you're networking —with a thesis statement in mind, it's easy to respond when someone asks what type of job you want.

Your thesis statement should intrigue potential employers, so they want to learn more about you and your credentials. Keep in mind that your thesis statement should be dynamic, evolving to fit the needs of the role at hand.

The first step to developing your thesis statement is to think about the positions you want to apply for, what you have to offer a company, and why employers should hire you.

Here are some tips for developing a strong thesis statement:

- Be direct : Your thesis statement should be simple and to the point, as hiring managers don’t have time to figure out what you’re trying to say. This isn’t the time to show off your extensive vocabulary. The same strategies you used to craft an elevator pitch will come in handy when you're thinking through your thesis statement.

- Tailor your statement : Start by developing a general thesis statement, and then tweak it to target the job you're applying for. You may have an IT certification and also be a strong presenter, but if you're applying for a job as a computer technician, the IT certification is more important to mention. If you're applying for a position as a sales representative at a software company, you'll want to emphasize your presentation skills.

- Frame your skills as benefits to the company : One goal of a thesis statement is to make it readily apparent to a hiring manager how hiring you will be beneficial. For example, you might say that your management skills will help you develop and train an exceptional sales team that will meet or exceed company sales goals. You may need to research a company to find its goals and priorities.

A summary statement is similar to a thesis statement, but it focuses on factual experience without the emphasis on benefits. For example, you might say, "Executive assistant with seven years of experience maintaining schedules, arranging travel, and handling correspondence."

If you’re not sure what to include in your thesis statement, these examples can help:

- I'm writing to apply for the administrative assistant position at ABC company. My strong communication and organizational skills, and my ability to create order out of chaos make me an excellent match for this position.