How To Research Your Novel – A Step-By-Step Guide

Are you ready to start your novel? Do you want to make it believable? Not all stories are scientifically sound, but even ones with magic or set in futuristic worlds have a sense of reality that captures their readers. Research is a major part of making any story feel life-like, but it isn’t always easy to know where to start. This guide will show you how!

How to begin researching

Before you start, you need to decide the overall theme or topic of your novel. Do you want to share a life lesson? Do you want to capture a sense of horror? Maybe you want to tell a story about a relationship or a historical event.

You might have an idea what you want to write about already. Whether you do or not, take a moment to ask yourself these questions:

What kind of story do I want to tell?

Is it centered around a real-world experience?

Will it be set in a fictional world or reality?

What genre will it fall in?

Who is your target audience?

Who are the main characters?

If you have all of the answers for these already, great job! But if not, don’t worry. You don’t need them all just yet. You will find the answers as you continue through this guide.

Let’s take the questions one at a time.

This focuses on the theme or topic of your story. It could also mean the atmosphere – is this a comfort story? Something to disturb your readers? Something to provoke thought?

Maybe you want to talk about the effects of pent up thoughts to the human psyche. Or perhaps you want to share a comedic allegory. Whatever it may be, it is what will make your story a story.

Take some time and look at your favorite films, TV series, and novels. What do you love so much about them? What are they about? What message do they tell? Do you see a common theme between them?

Use this information to decide where you’d like your own story to go.

This could be anything from a small interaction you had with someone to a historical event.

While that sounds like it only applies to non-fiction novels, it doesn’t have to. A real-world experience can be translated into an essence or idea – for example, Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game is about military strategy and economic tensions between humans and an alien race, but it is inspired by Cold War tensions between the U.S. and Soviet Union after WWII.

You get to decide.

Are you the type of person who finds a setting is essential to the story, and loves reading about details of places in books? Do you like the idea of making up your own cultures, norms, or an alternative society? If yes, fictional world-building might just be your thing.

If you prefer to keep it in the real world, keep in mind the time period* and location you are aiming for. Placing a smartphone in 1854 wouldn’t work, unless you were writing alternative historical fiction.

On that note, you can also place your story in the “real world” but make changes yourself. Many stories include cities and towns that don’t actually exist. Others are inspired by real places. Veronica Roth’s Divergent series is placed in a dystopian version of Chicago, Illinois – completely unrecognizable from the real city.

*If you do choose to write historical fiction, spend some time researching the years your story will span. Focus on the customs, beliefs, and lifestyles people had back then. Take lots of notes. Set up a timeline of events to help guide your story. Feel free to reach out to experts for specific questions or even read a diary or two from someone who lived during that time.

This question might not be answered until you’ve completed your novel. It can be tricky. There are so many options to choose from, and many niches and subgenres.

If you run into trouble defining which genre your story actually falls into, take a look at genre descriptions like this one for more information. If your story contains elements of multiple genres, select the one it has the most of as the one to define it, or research if there is a subgenre that combines them.

Maybe you want to have this answered before you even start. In that case, look at genre charts now and understand what types of themes and characters occur in each one. This will help you get an idea of what kind of conflict your story will have, what the characters will be like, and what your audience will expect.

Your target audience goes hand-in-hand with your chosen genre. Are you trying to attract mystery-lovers? Horror enthusiasts?

But it also includes certain demographics. Are you writing romance for middle-aged, single women? Self-help for college students? Moral lessons for tweens?

Select an age range that might be interested in your story. Then, break it down into more demographics if necessary – occupation, interests, income level.

You don’t want to write a novel about your fixer-upper journey and how you became debt-free at the age of 32 for retired millionaires. That would be for young adults (just-graduated high school students entering the workforce, college students, young newlyweds) looking to gain independence, buy their first house, pay off loans, and start a new hobby or source of income.

Write down each character and start defining who they are – their personalities, their motivations, their conflicts.

It may help you to do a quick Google search for character charts . They are often a good character-building practice and can help guide you when you feel lost. Many of them include details you won’t need in your novel, but they can help you get to know your characters better.

A good reader will notice when there are unseen details about your characters that they might not know, but you do. Whether you realize it or not, those details will bleed into your story. They make your characters feel much more alive.

Continuing your research

As you dive into the details of your story, you’ll want to make sure the information you collect is accurate, relevant, and from trustworthy sources.

When conducting your research, be sure to use reputable sources and cross-reference your facts. This can be especially important for a work of historical fiction, science fiction, or even fantasy.

Get in contact with an expert – not only will they give you useful information and confirm details, but they can offer a different perspective. If one of your characters is a geologist, talking to a geologist and getting their opinion on your character wouldn’t hurt.

When you’re ready, have other people read your novel and ask them for feedback. You do a lot while writing – you won’t catch everything on your own. Readers can help you find any plot holes or inaccuracies.

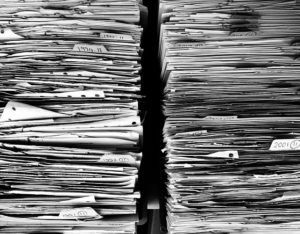

Writing a novel can be hard work and it’s easy to fall into a rabbit hole while learning about new and interesting things. You can make sure you stay on track while gathering information by setting up a timeline or map of your research. Take lots of notes and write down the source of any information you gather to reference back to later.

Start with your characters. Follow a character chart to learn about their personalities, goals, and motivations. The more you understand your characters, the easier it will be to tailor your research to their stories. Then, move on to your setting. Know the location, the climate, the culture. These details will help you fill in your own story and you gather more information.

Trustworthy

You don’t want to have false facts in your story. To get the most out of your research, consider looking at primary sources like diaries, newspaper articles, or interviews with people who experienced something first-hand or are an expert in their field. You can also find credible secondary sources in books, research papers, videos, and even blog posts.

Researching a believable novel

After following these steps, your novel should be believable. The key is relevancy.

For example, if you’re writing a crime novel, look into the criminal justice system. Interview a judge or a police officer. Read up on past crimes to study criminal patterns. Read reports from psychologists to learn different mindsets and apply them to a character.

Focus on your characters and setting, and conduct your research based on what you know about them. Be open to asking questions and always learning more.

And most importantly, have fun with it!

Unleash Your Story

900 State Street, Suite 301C

Erie, PA 16501

(c) 2024 Next Chapter Stories, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

How to Research a Novel: 9 Key Strategies

by Joslyn Chase | 2 comments

Have you ever started a story, gotten halfway through, and realized you don't know key facts about your story's world? Have you ever wondered how to find out the size of spoons in medieval England for your fantasy adventure story? Is that even relevant to your plot, or could you skip that fact? Here's how to research your novel.

As fiction writers, our job is to sit at a keyboard and make stuff up for fun and profit. We conjure most of our material from our imagination, creativity, and mental supply of facts and trivia, but sometimes we need that little bit of extra verisimilitude that research can bring to a project.

When it comes to research, there are key strategies to keep in mind to help you make the most of your time and effort.

9 Strategies to Research a Novel

Readers who’ve posted reviews for my thriller, Nocturne In Ashes , often comment about how well-researched it is. While that can be a positive sentiment, that’s not really what you want readers to notice about your book. The best research shouldn’t call attention to itself or detract readers from the story so I’m always relieved to hear those same reviewers go on to rave about the thrills and suspense.

When you're writing, you want to get the facts right and create a believable world. Doing research for your novel is the way to do that. But you also don't want to get sucked into a research hole, so distracted by the local cuisine of a small town in 1930s France that you never actually write. And you want to hook your readers with a page-turning story , not a dissertation on some obscure topic.

Here are nine key research strategies I’ve learned to write an effective (and exciting!) story.

1. Write first, research later

Research can be a dangerous enterprise because it’s seductive and time spent in research is time taken away from actual writing of the creative process. Getting words on the page is job one, so it’s important to meet your daily writing goal before engaging in research.

So if the piece you’re working on requires research, your first order of the day should be to write something else that doesn’t need research, something you can draw purely from imagination and your own mental well. Fill your word quota, practice your skills, meet your production goals, and THEN move on to research, so you don't derail your writing process with it.

I always have multiple works in progress. I’m writing project A while researching project B and thinking about and planning projects C through M.

2. Research is secondary; telling a good story comes first

After all the precious time boosting your knowledge of historical events or the feel for a subject, this point might hurt: only use a tiny fraction of your research in the story.

Don’t give in to the temptation to dump everything you've learned into the story. Sure, it’s fascinating stuff but you risk burying the story in scientific or historical detail.

A little bit of researched material goes a long way. Only use info related to the issues your character would know about and be concerned with. Leave out the captivating but irrelevant details.

Your research should enhance the story, not dominate it.

3. Write for your fans

Your story should be targeted to the readers who love what you write—your fans. Stop worrying about the five people out there who might read your story and nitpick that your character used the wrong fork or wore the wrong kind of corset.

A lot of writers fake it or write only from the knowledge they do have. They don’t let their lack of esoteric knowledge get in the way of the story. They do research for their novels, grab a few details for the sake of authenticity, and wing the rest.

With the exception of 11/22/63, Stephen King does very little research, but there are few who can write a more riveting story.

4. Don’t obsess over accuracy

Frankly, there are instances and reasons where you don’t really want to be accurate. For example, if you write historical romance, research might show that people of that time period rarely bathed and lost most of their teeth and hair at a young age. That’s probably not how you want to portray your heroine and the man of her dreams.

Sometimes, including a historically or scientifically accurate detail would require pages of explanation to make it credible for today’s audience—almost a surefire way to lose your reader. When in doubt, leave it out.

And no matter how hard you work at it, you’re not likely to cover every detail with one hundred percent accuracy, so don’t obsess over it. Do your best, but remember—story is what matters, not accurate details.

5. Go with the most interesting version

When researching an event, you’ll usually find a number of different accounts, especially when using primary sources, none in perfect agreement with the others. When this happens, do what the History Channel does—go with the most entertaining version of events.

Remember, you’re a storyteller, not a historian. Your goal is to grab and hold your reader’s attention and keep them turning pages. If it makes you feel better, you can include endnotes with references so interested readers can dig deeper into the “facts.”

6. Keep a “bible”

This is especially important if you’re writing a series. You can’t be expected to remember every important detail about the characters and settings you put in book one when, years later, you’re working on book seven.

Record these details in an easy-to-reference format you can come back to later to provide continuity and reader confidence in your ability to tell a coherent story.

7. Don’t fall down the wormhole

I love doing research. It’s fun, fascinating, and absorbing—so absorbing, it can suck you in and keep you from moving on to the writing. You need to be able to draw the line at some point. As Tina Fey says in her book, Bossy Pants , “The show doesn't go on because it's ready; it goes on because it's 11:30.”

Know when it’s time to leave the research and get to the writing. Pro tip: set yourself a time limit or a deadline. Even if you don't “feel” finished with research, you'll have a clear marker for when you have to put the research down and get back to writing.

8. Save simple details for last

Sometimes when you’re writing along in your story, you’ll find yourself needing a simple detail. Make a notation, resolve to come back to it later, and move on. Don’t let this interrupt or distract you from getting the story down on the page.

Later, you can come back and do the minimal research to fill in these little details like a character name , a location, a car model, etc. Shawn Coyne calls this “ice cream work” because it’s fun and feels frivolous after the concentrated work of writing the story itself.

9. Finish THIS project before starting another

One great thing about research is that you learn so much and find the seeds for so many new story ideas. The challenge is to not get distracted from your current project.

Make a note to yourself to pursue these other ideas somewhere down the road. Let those seeds sprout and grow in the back of your mental garden, but keep your focus on the story you’re writing now .

Resources: Where to Actually Research Your Novel

I’ve touched on how to do the research. Here, I’m adding a few suggestions about where to go for the goods.

- Wikipedia, and don’t forget to dig into the links at the bottom of the article

- Reenactor sites for historical battles, uniforms, etc.

- Costuming sites

- Travel guides

- Writer’s Digest Writer’s Guide to Everyday Life in … fill in the blank (these are loaded with details of landscape, clothing, household items, and more)

- Biographies and autobiographies, and don’t overlook their bibliographies and footnotes

- Blog posts of expert and amateur historians

- Journals and diaries

- Weather reports

- Price lists, to find out how much were salaries, groceries, mortgage payments, etc.

- Birth and death certificates, court documents

- Etymology websites

- Museum exhibits and gift shops, including the little touristy booklets, maps, tour guides

- Libraries! Talk to a reference librarian—they’re awesome at plumbing resources.

Novel research rocks!

Research really is intriguing and a lot of fun. There’s so much to discover, but beware because you can get lost in it and never find your way out. You’re better off under-researching than over-researching, so know when to get out and move on.

Also, be aware that your novel's research requirements will differ somewhat based on the genre you’re writing . For instance, with historical fiction, you need to give your readers a travel adventure into the past with sensory details to draw them into the time period.

With science fiction, you need to be able to extrapolate from scientific fact and theory to the fictional premise of your story. In doing so, don’t get bogged down in the journey from point A to point B. Just get to the conclusion. The more you explain, the less credible it sounds to the reader.

With fantasy, it’s the little world-building details that count for so much. Know what your reader expects and craves and meet those demands.

And no matter how much research your book requires, don't discount your personal experience with being human—those emotional, intellectual, and philosophical experiences often cross time and space.

I wish you many happy hours of successful novel research, but don’t forget to write first!

How about you? Do you do research for your novels? Where do you turn for information? Tell us about it in the comments .

Use one of the prompts below or make up your own. Conduct a little research—just enough to add verisimilitude to the scene, a few telling details. Spend five minutes researching two to three facts that will help you set the scene. Then, take the next ten minutes to write a couple of paragraphs to establish the character in the setting.

The death of her father leaves Miss Felicity Brewster alone in regency England and places upon her the burden of fulfilling his last wish—that she marry a safe, respectable gentleman.

Accused of treason, Frendl Ericcson sets out to find his betrayer and restore his honor.

Dr. Vanessa Crane makes a breakthrough in her nanotechnology research. But will her discovery benefit mankind, or destroy it?

With the help of his mortician friend, Victorian-era detective Reginald Piper must use cutting-edge forensic methods to solve a string of murders.

When you are finished, post your work the Pro Practice Workshop here and don’t forget to leave feedback for your fellow writers! Not a member yet? Check out how you can join a thriving group of writers practicing together here.

Joslyn Chase

Any day where she can send readers to the edge of their seats, prickling with suspense and chewing their fingernails to the nub, is a good day for Joslyn. Pick up her latest thriller, Steadman's Blind , an explosive read that will keep you turning pages to the end. No Rest: 14 Tales of Chilling Suspense , Joslyn's latest collection of short suspense, is available for free at joslynchase.com .

I wish I’d read point 6 – keep a bible a couple of years ago before I wrote my 450k word magnum opus, because I’m now writing several supplemental short stories in that universe and I’m forever digging through for minor character’s names, details of meeting places etc

My current WIP is involving a lot more research than I expected. I had to re-write a hunting scene twice, because the first version, which I showed to a real bow-hunter, had him going after the deer right away, and my hunter-friend said to wait a half hour before you start tracking a deer. I don’t hunt myself, so I took his word and re-wrote it, but my gut said it wasn’t right. So I did some surfing and found both his advice, and advice that said you should go after a hip shot right away (basically agreeing with what my gut said should be happening). So was he wrong, were the sources that agreed with me wrong, or was he getting a wrong impression of what was going on? I decided I was overly in love with the opening sentence of the scene and re-wrote the whole thing yet again, using the “simple details” I’d discovered to clarify the deer had taken a hip shot. Minor scene, but a major position: it’s introducing the #2 member of my hero team.

Could it wait until later? Possibly, but I’m seriously considering serializing this thing, so the beginning chapters might be getting published before the end chapters of the first book get written, and I’m hoping for seven books out of this (probably close to 1M words total).

The Devil is in the details!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Best Resources for Writers Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

- Out Here At The Edge Of The World

- Effra: a novel

- Manuscript downloads

How to research a novel: the 7 most up-to-date tips

Much of the advice available on researching novels is now dated. So this blog post includes the best modern tips on how to research fiction, with a case study included.

There I’ll show you step-by-step how I used the tools described below to construct a chapter in one of my novels. Once you’ve read through the tips and the Case Study you can even jump here to preview an ebook version of the completed product, which will give you a chance to assess how effective these tips are.

But first, for those who like to skim, let’s sum up the 7 basic pieces of advice on novel research.

How to research a novel

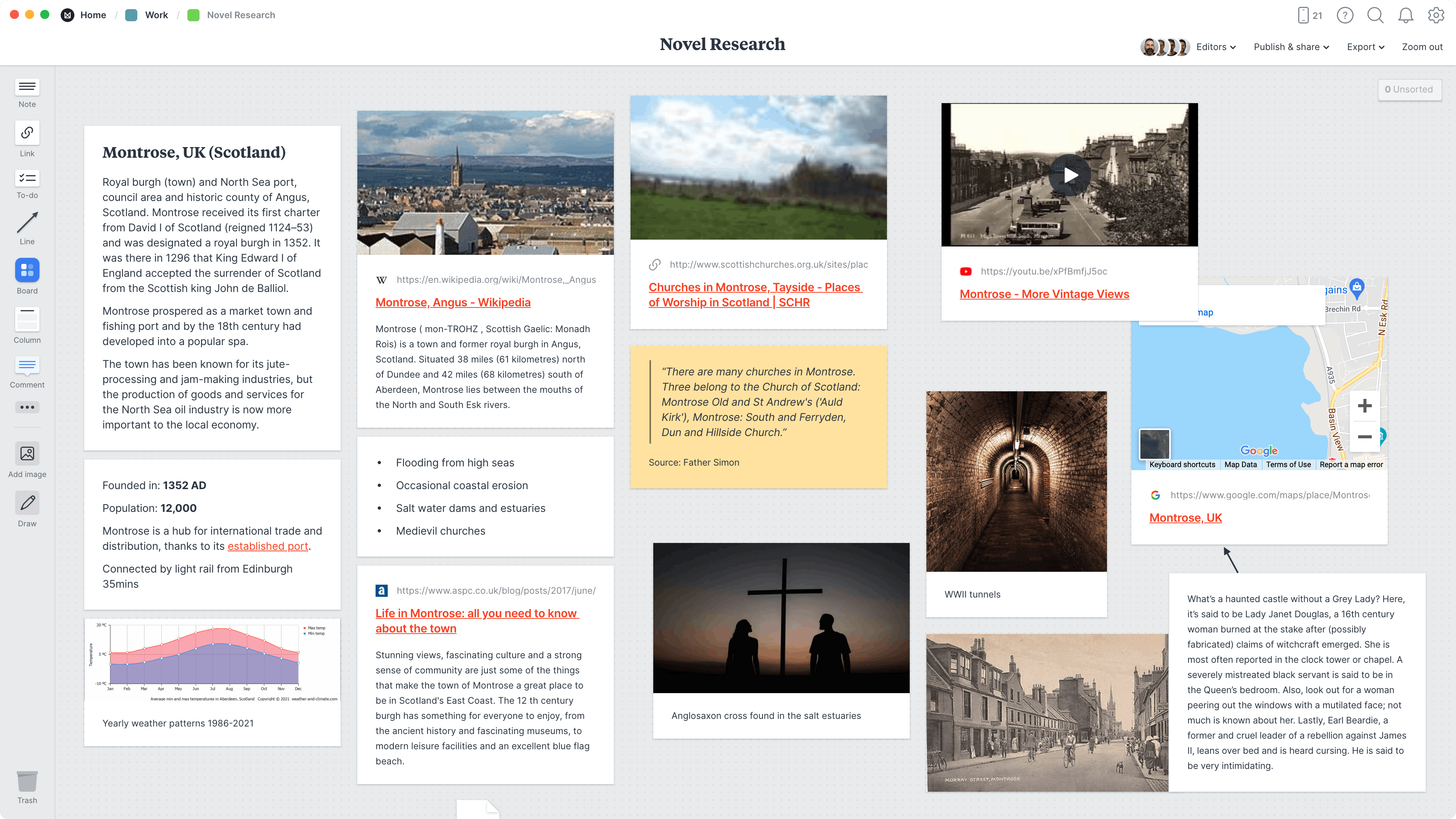

- Use Pinterest as you research your novel by building a visual reference guide

- Use tools like Google Street View to add a dash of realism to descriptions

- Wikipedia is good for researching cultures, places and times for historical novels

- Use Instagram hashtags to research specific locations in your novel

- You can use your dreams as a research tool!

- Remember to step through the screen as you research

- Post questions on Quora and Reddit to tap the real experience of strangers

1. Use Pinterest when researching your novel

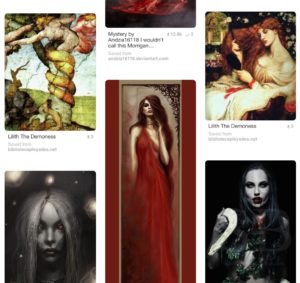

Pinterest isn’t just great for collecting ideas for your next bathroom renovation or helping you find a really great bridesmaids dress – it’s also an invaluable tool for fiction writers looking to build a mental picture of what they’ll write about.

The key to Pinterest is that it’s a visual medium. So what you’re doing when using Pinterest to research a novel is collating images that will enrich your mental picture of the world you’re writing . The visual side of what you write is really important, and collecting images into Pinterest boards will give your imagination a real boost.

Tip: the best advice here is to go all-in on Pinterest. If you use it half-heartedly you run the risk of being excessively influenced by one or two images. But if you invest the time in collecting lots of diverse images that inform each part of your upcoming novel, then it’s more likely that the visuals that you write into the book will be greater than the sum of the parts that inspired them. So go for it: create some boards and start pinning picture that you find.

How to build a visual reference guide with Pinterest

There are two way you can approach Pinterest for novel research. The simplest is just to create a Pinterest account for yourself (or use your current one) then have it on hand as you browse the net so that you can pin images that inspire you as you stumble across them. The other more proactive way is to spend time researching in order to build a visual reference guide for each part of your book. To do this create boards for each aspect of your book that you feel needs more visual input – then search (both inside Pinterest and out) to build a visual library of images that speak to you. You can then refer back to these when writing to help spark your creativity.

Use Pinterest to create a mood board for each chapter

You can also collate images in Pinterest when researching your novel simply to help put your finger on a particular mood. A mood board for Bram Stoker’s Dracula, for instance, might include a board entirely filled with images of crumbling castles. But it could also include a mood board filled with photos of Romanian peasant village life to inform other scenes, and boards with images of upper-class Victorian life for the scenes that take place in London.

Use Pinterest to create a visual guide for each character

Drawing a blank when you try to picture an important character? Don’t stress. Just jump on Google Images and search all of the phrases that you have for your character. Are they tall, dark and brooding – Google that! Now look through any images that gel with what you had in mind and add them to the relevant board. Then rinse and repeat. By the end you’ll have a great sense of how your character looks.

2. Use Google products to research your novel

As the Google suite of products has expanded, so too have the tools available to authors. Don’t overlook the research techniques that Google now puts at your disposal.

Measure distance and travel times

When Character A needs to get to Location B it can help – if you’re writing in the real world, rather than a fantasy location – to ask Google for directions, in order to get a realistic sense of travel times. Writing about a road trip that you haven’t actually taken yourself? Avoid alienating readers that know the place by getting your distances and details right. And when it gets really crucial you can even use a point-to-point measuring tool in Google Maps by right clicking with you mouse on the map. That sniper shot across New York’s Central Park in your latest thriller is going to be that much more realistic when you know the space is exactly 845 metres wide.

Use Google Street View for flashes of veracity

Another great tip is dropping the little yellow figure on to the map to see exactly what any given street looks like from street level. You can really lift a scene – especially one set in a real place that you’ve never been to – by having your character note landmarks that are actually there. Maybe have them reflect on a church, or a distinctive building – or even notice some street art on a mural. Google Street View will help you add this layer of authenticity.

Find real shops and restaurants for particular scenes

In a similar vein to the point above, you can also easily set key scenes in real places with a little internet research. This can be a neat way to add veracity to a book, but it’s also a good way to step beyond your own visual limitations. What I mean is that you probably have a fairly straightforward scene in your head if you were to picture a generic cafe or restaurant – so by finding a real place online, you can really freshen a scene with a dose of reality. Top tip: menus are generally available via Google too!

Install Google Keep on your phone for taking notes on the go

Researching books isn’t just about collecting facts, it’s about having enough impressions and ideas to bring your scenes and characters – and their thoughts – to life for a reader. So if you see something unusual or striking in your day-to-day, jot it down and have your character notice it themselves in some scene, for that extra dash of realism. A notebook and pen in your back pocket is ideal for this – but better still is installing Google Keep on your phone so you can take your notes down there. You can organise them into handy sections, they’ll be automatically backed up to the cloud, and you can even record voice notes for when you’re on the move.

Use baby name databases for character names

There are a lot of internet baby name databases designed to help parents choose a moniker for bubs – and most include the meaning and origin of each name, which is very helpful if you want your character names to resonate with your themes. Have a strong female Middle Eastern character? Find an Arabic woman’s name that means ‘brave’. Or you can easily do a little Googling to find out, for example, what working class men’s names were popular in Victorian England. After all you cockney jewel thief main character won’t ring true when he is called Tarquin or Eustace if real cockneys of the time were called Frankie or Bill.

3. Use Wikipedia to research places and cultures for historical novels

Wikipedia is an invaluable tool for historical novelists. Its accounts of various historic periods, places, people, cultures and religions are a veritable rabbit hole that you can fall down, with convenient hyper-links to each related topic. Just be sure to copy out the parts that are most useful, so you don’t lose them as you venture deeper in…

4. Use Instagram to research places for your novel

Instagram is naturally a useful resource when building a mood board for any given character or scene (see the tips on using Pinterest above) but perhaps its greatest use for novelists planning a book is in helping authors visualise places that they’ve never been. Travel photographers here are a goldmine. Simply search for a certain location or place by hashtag, and follow anyone who regularly posts from that place for a steady stream of genuine visuals. For instance when researching for my young adult series set near Afghanistan and Iran I found a series of fantastic young Iranian photographers who regular posted pics that totally expanded my awareness of what those places really look like.

5. Use your dreams as a research tool

Okay here I’m not talking about your deepest wishes and desires – I’m talking about your actual nighttime dreams. These are a tremendous resource of material for any work of fiction and, unlike all of the internet research resources listed above, your dreams are utterly unique to you. If you’re lucky enough to have good dream recall, then get in the habit of jotting down in a notepad beside your bed what you can remember when you wake. If you do that before they fade you’ll find them invaluable material for any creative work – especially novels.

6. Remember to step through the screen

Okay, hopefully you’re finding these tips useful, but before we go on let’s remember one important thing. The internet has no smell and it doesn’t have a sense of touch. So there’s a real risk when you research a novel that the material you uncover is one-dimensional. Remember, your job as a writer is to make people feel an experience, not simply visualise or think about it. So be sure to step through the computer screen when you research and try to imagine what the things you are finding out about actually feel like in real life.

7. Use Quora and Reddit to research your novel

Quora and Reddit are online communities where you’ll get great traction by posting questions – so they’re another great tool for fiction research, especially on hard facts like ‘How far can a soldier march in one night?’ or ‘What’s the maximum operating altitude for a hot air ballon?’. And because those communities are full of random experts in all sorts of curious corners of knowledge, you can tap them for specialist details that you simply can’t source elsewhere: ‘What rights did women have in 17th Century Spain?’ perhaps (for those historical novelists again), or ‘What was considered elderly in Viking culture?’.

Top tip: identify these questions early on and post them at the start of your research journey to give people time to respond.

Use Quora and Reddit for the feels

Most importantly though, unlike any of the other research tools above, you can use these platforms to find out what an experience is actually like . Be sure to ask things like ‘What does it feel like being in your first firefight?’ or ‘What’s it like being swept up by an avalanche?’. This is the kind of level of realism that can make your novel shine.

Some Dos and Don’ts when researching a novel

To wrap up this part of what has hopefully been a useful post – and before we get in to a Case Study that gives an actual example of how this sort of research can play out, let’s look at some final dos and don’ts of the novel research game:

- Do use internet research to spark your imagination.

- Don’t use internet research to just assemble a collection of other people’s ideas.

- Do let research morph into actual writing. You need to take your inspiration where it comes.

- Don’t forget to back up your research (and manuscript). A simple upload to a free cloud service like Google Drive will save you heartache when your laptop harddrive fries or you leave it on the train.

- Do store your research in one place. Even a simple word doc with links at the start to all relevant social media accounts (e.g. Pinterest, Quora) followed by notes broken into sections will do.

- Do use your local library – but as a last resort. A physical trip there is likely a waste of your time, however pleasant. Find out what books you want to borrow by searching online, then order them through your library’s website.

Case study: Researching a novel in the age of Google

One of the things that only strikes you about writing a book after you’ve sat down and started is how crucial it is to write from immediate experience. It can be a real struggle to describe something you haven’t seen, smelled, heard and observed personally – and to stop it being a hollow and phoney reduction of other books and movies you’ve digested. Anyone who reads it is likely to sniff out that it’s phoney right away, and biff the book.

With this in mind, I thought I’d describe the process of writing a fiction chapter entirely via Google products – Google Maps, Streetview, Earth and Images – plus some extra research on Wikipedia.

It’s something that should have sounded a death knell for the chapter in question – but in this case, I think it worked. In fact, it’s probably my favourite out of the whole 87,000 word novel. (For those interested in seeing how using this approach played out, the chapter in question can be found in Effra, A Novel here)

It was a funny passage though. I decided to write it at a point where almost everything in the book had been planned. I had the logic of the plot and the themes and the development of the main characters all planned out in a kind of delicate arrangement (it only lacked a finale – that would come later). In my head it looked like a model of DNA – different threads wrapping around each other, all building towards a greater purpose. And I was pretty pleased with that image, because for a LONG time it had looked like a ball of wool that a cat’s played with. But then something funny happened. I’d sorted the logic of what happened and why and to whom – and the excitement died.

It felt like any reader who was familiar with basic story-telling would feel they were being hurried to a foregone conclusion. I was being careful to write a tight story, one without a lot of fat in it, but as a consequence you could see the bones. You could sense the logic. The story felt inevitable – and because it felt inevitable, it was no longer exciting. I’m a big believer in the reader providing at least half the story – after all, you make the pictures in your head, you provide the emotion – but a reader who feels like a story is inevitable, gets bored. Why should you care about a story that doesn’t let you play along, that seems intent on having things march along the way it wants, and expects you to just tag along for the ride?

So I decided to write something that would let the story breathe. Something completely pointless, that the reader would enjoy reading and I would enjoy writing (I think those two flow into each other): I sent my main characters on holiday.

Just for a short one – a train trip to the countryside for a day. The sort of thing I had done dozens of times from London. And anyway, I needed my characters to get close, and holidays are one way that happens. Perhaps by the time I finished the chapter, sparks would appear…

But where to go? This is where technology came in. I was writing about a trip out of London from a desk in suburban Auckland, and I wasn’t about to hop on a plane for research reasons, the way ‘real’ writers should. I had to do it over the net.

I needed them to visit a town a few hours, max, from London. It had to be on a train line – the characters had no car. It had to be small. And it had to be pretty.

I loaded Google Maps.

From London I scrolled around in a circle, and found the main train lines. Traced along the lines until I found towns – hunting for a small one somewhere nice. Sussex? Surrey? Kent… Kent would be good. Down the line I went, ’til I found Wye.

Well Wye not? Did it look nice? Up came Google Earth, I found the place and zoomed in – trees, fields, a line of hills – it was perfect. But what the hell was that?

The town had looked the right size, so using the tilt tool I’d raised the horizon up to a person’s perspective. That way I could see the place in the same way my characters would. I moved Google Earth to the train station where they’d disembark – and form their first impressions – and hit the 3D button for extra realism.

Up came the hills (or downs, rather), only to reveal a strange symbol carved in chalk – which would be visible from where they’d be standing.

This was perfect. My book had a theme of old things coming up through the surface of the modern – so this seemed like a gift from the gods. I would research what this strange symbol was via Wikipedia, and have my characters check it out as part of their day trip. Done.

Incidentally, anyone who’s read the book or this chapter will probably realise that the process of researching it matches closely to how the narrative evolves. The two characters start off not knowing where to go – they roll out a (real) map – choose the place, then pile out of the station and spot the carved chalk symbol. Everything they do just rolled out of the process of researching the town of Wye over a few days, and I wrote it as I went.

From the station I had them walk up the hill to the carved symbol, then I realised they would soon need some lunch. Out came Google Earth again – I needed to find them a pub. On Google Earth I spotted the next small town over (Crundale I think), and using the distance measure tool, I worked out that it was realistically walkable. Then I switched to Google Maps to get closer. That looked like a pub… I switched to Google Streetview and confirmed it – went back to Google Search to find the pub’s name, and had them walk over there across the downs. Phew.

Hey but what did those downs look like from ground level? At that point I started searching Google images for “Crundale” and “Wye” and found this idyllic shot of people walking between the two towns.

Perfect. What a relaxing image. It had exactly the feel I’d wanted to create in this chapter in the first place – that drifting holiday looseness. So where was the image from? Oh – the website of walking club for older gay men. Ha! And now that I looked closer at the people making their way down the hill, I realised I had a minor character in the making…

The portly gent in the floppy hat seemed just right. Plus, in all this research, I’d stumbled across the fact that Wye and Crundale are hotspots for rare English meadow butterflies. I imagined the gay walker in the photo as an amateur lepidopterist, and the character at the pub, David, was born.

I could go on and on about this chapter – actually I already have – so I’ll cut it short and just say that the whole experience generated a lot of writers luck. The butterfly thing matched with a mention I’d made in the book already; one of the streets in Wye had the same spooky name as a local Brixton lane; I’ve already mentioned the chalk carving: the whole thing just flowed and I wrote at top speed for two days. By the time I got my characters back home to London they, and I, were exhausted and the chapter’s ending – the sparks I’d hoped might be there – they just fell in to place naturally.

So to sum it up – and I’d like to hear what you think on this too – I reckon writing from internet research is dangerous.

For one thing, the internet doesn’t smell (except maybe if you pick that crud out of your mousewheel; I’m not sniffing that – and you shouldn’t either). It doesn’t have breezes or seasons, or move between dawn and dusk – there’s just one constant, backlit ever-day. In short, it’s not tactile in the ways I think you should draw on when writing. And on top of that, the experiences you do have are through someone else. You experience via someone else’s words, camera, website, Google-van, satellite, whatever – seeing things in a way they’ve been seen before – and I think you risk that derivative quality creeping into your writing.

Yet I like how my chapter came out.

And hell, the internet is incredibly powerful – you can get a street view of almost any place in the world, for crying out loud, without spending your life savings flying round the world researching like a ‘real’ writer. So I think that as a literary research tool, it’s here to stay.

But I think it’s crucial that when you use these tools you blend the things you gather with real experiences you’ve had –things that you’ve smelled, seen and thought – or you risk it coming out flat and flavourless.

14 tips for improving your writing that editors will never tell you

Ceos: please don’t think you’re doing ‘thought leadership’, you might also like, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

The Creative Penn

Writing, self-publishing, book marketing, making a living with your writing

How To Research Your Novel … And When To Stop

posted on January 18, 2017

I love book research. It's one of the most fun parts of the book creation process for me , but I definitely need to make sure I don't disappear down the rabbit-hole of research and forget to actually write!

If you’d like more help, check out my book: How to Write a Novel.

Is research really necessary?

If you're writing non-fiction, research will most likely be the basis of your book. For fiction, it can provide ideas on which to build your characters and plot.

You can go into the research phase with no concrete agenda , as I often do, and emerge with a clear idea of how your story will unfold. Or, if you have pre-existing ideas, research allows you to develop them further . In terms of reader expectation , research is critical in genres like historical fiction, as it will help you to create an accurate world and ground the story in reality.

When people read a story, they want to sink into your fictional world. If you introduce something that jolts the reader, the ‘fictive dream' is interrupted. For many genres, research can help you avoid this.

Most of my J.F.Penn thrillers are set in the present day and I like to have 95% reality in terms of places, historical accuracy and actual events. Then I push the edges of that reality a little further and see what happens.

How to research your novel

Research can take many forms. Here are some of my methods for gathering information.

(1) Research through reading and watching

“Books are made out of books” – Cormac McCarthy

Your research process can happen online at the various book retailers or Goodreads, but I also like to take it into the physical world by heading to libraries and bookstores, as you never quite know what you might discover. I think of it as serendipity in the stacks!

If you're writing fiction, it’s important to read extensively in your genre in order to understand the reader expectations, but many authors also find it helpful to read a wide range of non-fiction books on the topics they're interested in.

You can also read magazines and journals; browse images on Pinterest and Flickr; and watch documentaries and films on TV and YouTube. Fill the creative well!

If you have concerns about plagiarism, take note of this quote from Austin Kleon’s book Steal Like an Artist .

“Stealing from one person is plagiarism. Stealing from 100 is research.”

For example, if you read five books on the history of The Tudors and you've written notes on all of them, then you turn that into something new, that’s considered research and is an entirely natural part of the writing process. It only slips into plagiarism if you copy lines from another work and pass them off as your own , and of course, that’s something we would never want to do.

(2) Research through travel

One of my favorite ways to carry out research is to travel to places where I intend to set a novel .

This may not fit your budget, but it’s not always as expensive as you might expect, particularly if you travel during off-season periods. For my recent thriller End of Days , we did a research trip to Israel. You can join me for a walk around the Old City of Jerusalem in this video made on site .

Information on different locations can be found on our own doorstep and museum exhibitions are the perfect example of this. Follow your curiosity – maybe one museum exhibit leads you to another and each sparks your imagination somehow.

We're also very lucky in that we live in a time where it’s possible to research travel destinations online, so you can write about a place even if you haven't been there . You can find clips on YouTube, watch travel documentaries, read travel blogs, and even get a feel for walking around a location via Google maps.

(3) Research on Pinterest (or other visual social media)

We can find inspiration on Pinterest by browsing other people’s boards, but it’s also the perfect place to gather our own research and easily record it. I have Pinterest Boards for most of my J.F.Penn thriller novels now .

For fiction authors, the visual medium can be particularly valuable for sparking ideas and bringing our fictional worlds into reality. You can even share this inspiration with your readers.

(4) Let synchronicity emerge

When I started End of Days , I only had the title and I knew it would have to have some kind of apocalyptic event, but it also needed to be original.

I found two books: The End , an overview of Bible prophecy and the end of days, and also The End: What Science and Religion Tell Us About the Apocalypse , a mix of scientific information and how different religions see the end of the world.

From these two books, I gathered a wealth of ideas including the quote for the beginning of the book from Revelation 20:1-6

“Then I saw an angel coming down from heaven holding in his hand the key to the bottomless pit and a great chain. And he sees the dragon, that ancient serpent who is the devil and Satan and bound him for a thousand years and threw him into the pit, and shut it and sealed it over him until the thousand years were ended .”

The serpent element sparked my curiosity so I started Googling art associated with serpents. I discovered Lilith, called the first wife of Adam and a demon closely associated with serpents.

Then I found this quote from the Talmud (Jewish scripture) about Lilith:

“The female of Samael is called ‘serpent, woman of harlotry, end of all flesh, end of days.'”

Yes, it actually calls her End of Days. Talk about synchronicity!

[This type of thing seems to happen with every novel I write, which makes me agree with a lot of what Elizabeth Gilbert says in Big Magic about ideas. It's a great book!]

Lilith and Samael emerged as my antagonists from this research, which also gave me rich story ideas for the plot. All this came from my willingness to go down the research rabbit hole.

(5) Research possible settings

The next stage was to consider a setting for my story and how I could use snakes in a much bigger way.

The setting is always a very important element of my books , so I looked initially at places sacred to serpent worship. I found an amazing documentary on YouTube about the Appalachian Christians, who use serpents in their worship, and from there the backstory of Lilith grew. I theorized that if she came from a group who were not afraid of serpents, then this might explain how she gets involved in the end of days conspiracy.

From one initial Google search on serpent worship, I had an outline for the plot of my novel .

This should give you an idea of how powerful research can be, taking you from an initial spark of creativity through to a completed book.

How to organize and manage your research

Your research will be far more effective if you keep track of it as you progress. You can put a couple of lines into your phone or write a few notes in a journal as you go along, but at some point, you need to organize this information so you can get writing.

There is no right or wrong approach to managing your research, just choose the option that works best for you and it will likely evolve as your writing career progresses. Some people use physical files, like a filing system, or a pin board .

When to stop researching

Research can be a lot of fun, but at some point you have to stop researching and start writing. Remember, research can become a form of procrastination and the more you research, the more information you will find to include.

Therefore, as soon as you have enough information to write a scene about a place, event or person in your novel, then maybe you should stop and do some writing about it. Keep a balance between consumption and creation , input and output.

Another way to approach this is to set a time limit . For example, if you know you need to start writing on a particular date to hit a (self-imposed) deadline, then work backwards to allow yourself a research period before this.

You can always do additional research as you write, but the important thing is that the book is underway.

Get started with what you have, fill in the blanks later.

Should you use an Author's Note about your research?

At the end of all of my books, I add an Author's Note which includes information on where my research came from and links to my videos and images along the way. It’s certainly not a requirement to do this but it can be beneficial to both you and the reader . My readers often comment on it when they email about the books.

We're all unique and that’s what sets our books apart so don’t be afraid to approach research in the way that suits you best. Whether you use research to spark initial ideas or to drive your narrative forward, the time invested in it will ultimately reap rewards in terms of the quality of your finished book.

Do you love the research process? Do you have any questions or tips to offer? Please leave a comment below and join the conversation.

If you’d like more help on researching, plotting or writing your book, check out my book: How to Write a Novel.

Reader Interactions

September 15, 2022 at 10:39 am

I’m writing a novel about immigrants to NY in the first decade of the previous century. I’ve done quite a bit of general research, but I’m stuck with specific details that are necessary to determine for the story, but which I can’t find answers to. Where does one go/Who does one turn to for the missing details? I’m pretty frustrated.

[…] to procrastinate from actually getting words onto paper or fingers onto keyboard. Joanna Penn of The Creative Penn has a great little […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Connect with me on social media

Sign up for your free author blueprint.

Thanks for visiting The Creative Penn!

How to research for a book: 9 ways to prepare well

Deciding how to research for a book is a personal process, with much depending on your subject. Read 9 tips on how to research a novel:

- Post author By Jordan

- No Comments on How to research for a book: 9 ways to prepare well

How to research for a book: Scope, process, tools

- Define the scope of research

- List headline research you’ll need

- Do a ‘quick and dirty’ search

- Lean on .edu and library resources

- Speak to pros and specialists

- Shadow an expert if applicable

- Read authors on how to research a book

- Have a system for storing research

- Stop when you have enough to write

1. Define the scope of research

Research for a novel easily gets out of hand. You’re writing about Tudor England, for example. The next thing you know you’ve read every doorstop ever written about Anne Boleyn.

Define the scope of research you need to do, first.

This is particularly crucial if you’re new to researching novels.

‘Scope creep’ (where the task becomes bigger and bigger, and the focus dimmer) is a common challenge in research.

If, for example, you’re writing a novel featuring the Tudors (rulers of England between 1485 and 1603), ask questions such as:

- What duration within this era will my story span? (e.g. ‘the last five years of Henry VIII’s life’)

- What information is vital to know? If, for example, you’re writing about a monarch firing a particular associate, this will narrow down your research

- What broad picture elements do I need? (For example, a timeline of key background social or political events within a historical period)

Narrow down what you need to learn to the essentials necessary to begin writing.

2. List headline research you’ll need

Once you know the scope of your research, list the big, main events and subjects you’ll need to cover.

For a historical figure subject like Henry VIII, you might have a list of research to do like this:

- Timeline of major events in the king’s life

- Personality – accounts of what the king was like

- Appearance – descriptions of what the king looked like

- Controversy – king’s many wives, execution of Anne Boleyn, etc.

Make a document with a section per each of the core areas of the story you’ll need to research.

Populate these sections with article snippets, links to educational resources.

(Google, for example ‘Henry VIII reign .edu’ to find information from credible learning institutions.)

3. Do a ‘quick and dirty’ search

In learning how to research for a book, learn how to work smart, not hard. Research the way a student with an assignment hand-in due the next day would, to start.

Use Wikipedia (a no-no in academia). You can find broad information and an idea of what to look for to verify and fact-check later on .edu and library websites , or in physical book copies.

Search amateur history blogs, too. There are many subject enthusiasts who have devoted hours to digging up interesting historical and other information and share their learnings for free in blog articles.

If you’re writing about a real place, use Google Maps to do a street-view virtual tour. You can explore cities you’ve never been to before. Read more more on researching place when you are unable to get there.

Note details to include in scene-setting and worldbuilding such as specific landmarks and architectural details.

Get a professional edit

A good editor will help pinpoint major factual inaccuracies and other issues.

4. Lean on .edu and library resources

When deciding how to research for a book, whether it’s fiction or non-fiction, favour credible resources.

You can even find fantastic primary source scans and recordings. Some examples of excellent, free online research resources:

- British Pathé : Pathé News, a producer of newsreels and documentaries from 1910 to 1970 in the UK has a rich and varied archive. It includes original footage (trigger warning: disturbing footage of aircraft explosion) of the Hindenburg Disaster.

- Tudor History: Historical .org websites such as this website on the Tudors provide a wealth of research information .

- The Smithsonian has regular online webinars, exhibitions and more where you can learn about a diverse range of natural history topics from experts.

If online research feels overwhelming, consider taking a course in online research skills.

The University of Toronto also put together this thorough list of questions to guide doing research online .

5. Speak to pros and specialists

Learning how to research a novel is made much easier by experts who are happy to share their knowledge.

If you are researching a specific place, language, historical figure, biological or medical issue or another detail, make a list of experts to reach out to.

Explain your fiction or non-fiction project and why you’d value their insights. You’ll be surprised how many are only too happy to contribute accurate, informed knowledge.

You can also find specialist knowledge in online forums devoted to specific subjects.

6. Shadow an expert if applicable

There’s no single ‘right way’ in how to research for a book.

You could take a leaf out of the method actor’s book, for example, and actually job shadow an expert [ Ed note: Once COVID no longer sets stringent limits on contact ].

Depending on the subject or industry, you may have variable degrees of success. For example, shadowing a medical professional has other issues involved, such as patient privacy/confidentiality.

In a roundtable discussion on preparing for roles, British actress Vanessa Kirby described job-shadowing on an obstetrics ward to research a role. Because she had never had a child herself, she wanted to give an authentic performance of a woman in labour (around the 18:15 timestamp).

Writing is very much like acting in this respect: You need to be able to fill in the blanks in your own imagination to prepare.

7. Read authors on how to research for books

In deciding how to research for a book, one also needs to decide how/where to use (or alter) source material. It’s helpful to read authors who write historical fiction and other research-heavy genres. What do they say about process?

Hilary Mantel, for example says this about taking creative license with historical facts:

History is a process, not a locked box with a collection of facts inside. The past and present are always in dialogue – there can hardly be history without revisionism. Hilary Mantel: ‘History is a process, not a locked box’, via The Guardian

8. Have a system for storing research

Research for a book easily becomes cluttered.

How do you keep research tidy and manageable, so that you have the information you need when you need it?

Organise your research for a novel with these apps and tools:

- Google Docs: Outline mode creates a clickable outline of your document in a left-hand panel – perfect for jumping between different categories of research.

- Evernote: This handy app makes it easy to snip bits of articles from your browser into collections to sort and store.

- Sytem folders: Create a folder on your operating system for your project, and subfolders for each research topic.

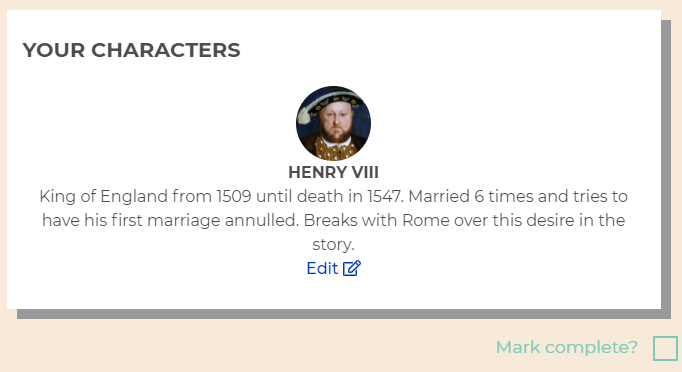

- Novel Novel Dashboard: You can also fill out character profiles and other prompts on Now Novel using historical sources (see an example below).

9. Stop when you have enough to write

In deciding how to research for a book, it’s important to set a stop point.

Ask yourself how much you really need to begin writing. Need to know what would have been served at a royal dinner in the year 1600? Make a note to add this detail later and describe the details of the occasion you can make up to keep going with your draft.

Balancing research and writing will ensure your research is fit to its purpose – finishing your book with relevant and precise detail.

Need help researching your book? Watch our webinar on writing research (and enjoy future live webinars and Q&A sessions too) when you subscribe to a Now Novel plan.

Related Posts:

- 5 easy ways to research your novel

- Historical fiction: 7 elements of research

- Book ideas: 12 fun ways to find them

- Tags how to research your novel

Jordan is a writer, editor, community manager and product developer. He received his BA Honours in English Literature and his undergraduate in English Literature and Music from the University of Cape Town.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Write and Finish Your Book

Publish your book.

- 1-on-1 Manuscript Review

- 1-on-1 Query Letter Review

How to do Research for a Novel

March 30, 2022 10 min read Fiction Historical Fiction

There is an abundance of information in books and online about how to research for a novel. Many writing books only discuss the topic peripherally, in sections focusing on character, theme, setting, or viewpoint. There are mentions of research in chapters examining the craft of writing, or planning.

Research, it is claimed, is a poor substitute for what you have experienced yourself. Online sources indicate how to keep notes, 5 steps to research, 7 steps or 7 tips, 21 steps, 9 key strategies, or other such itemized approaches.

But this article is about the process of research through direct and indirect experience , a case study with a focus on indirect experience.

So, what is direct and indirect experience, anyway?

Direct experience is life experience. You have gone places and done things in your life, and this is researching your topic through direct experience. If you have direct experience, how do you begin transcribing those experiences and making them interesting, coherent, and structured enough for a novel ?

Indirect experience can be studying life during a specific time in history where direct experience is not possible. So, in that case, what do you do? Where do you start?

Direct Experience

To take your memories and create the basis for a novel, you can begin by looking at your own unique past.

Novels created from direct experience can be very unique.

I lived and worked in Ecuador, South America for a year. This formed the basis of my first two novels, Poor Man’s Galapagos , and Abundance of the Infinite .

In Poor Man’s Galapagos , Tómas Harvey is an irrigation engineering student living on a small, impoverished island in Ecuador. His father is a renowned British travel writer who has travelled to many of the places I have visited. Many of the characters are conglomerations of people I knew there.

I was once locked in the university where I worked, along with students who were protesting against the president of the country. Tear gas bombs were being tossed inside by an armoured military vehicle. Burning tires lined the streets to prevent entry into the small town of Portoviejo. This forms the opening for my novel.

Abundance of the Infinite is about a psychologist who travels from Toronto to a small coastal fishing town in Ecuador. It is a story about the blurred line between lucid dreams and reality in a place so utterly foreign as the tropical rainforest through which I, and the main character, travelled.

Even with direct experience, some research is still required. This leads in to the next section…

Indirect Experience

In my latest novel, Intervals of Hope, the main character Nicholas lives with his mother and brother in London, England between the world wars. His father served with the First Battalion, First Canadian Regiment in the trenches of the Great War, and worked in the coal mines of South Leeds. This may seem, at first glance, like daunting research.

In beginning this research, I had the looming question later posed to me in the book launch . How many other books are out there set in the same time and place, and what makes mine different? So these are questions you should keep in mind.

As I answered in my book launch, there were some crime novels that took place in England between the wars, and some mass-market type books with scenes in that time period such as Ken Follett's Fall of Giants and Winter of the World . These were published within the last decade or so. A London Family Between the Wars , published in 1940, was written as a memoir but had a lot of interesting details.

So, I didn’t find a lot of interesting literary fiction set between the wars that explored the fascist movement in Britain at the time, the conditions leading England to war, the stories of the coal miners (although George Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier was appealing), as well as the reality of those who chose to escape their countries in a time of war, and the homing call for them to return and fight.

A key to the uniqueness of Intervals of Hope is the examination of the father-son relationship during that tumultuous time, given that the main character’s father was a WWI veteran, and the novel’s examination of the effect his father’s legacy had on his son as WWII loomed and ultimately took shape.

Copious Reading

As the novel starts in London, England between the wars, that's where I started my research. I read books such as the history of London (which was long and quite dry, highly recommended for insomniacs) and In the News , a book of newspaper clippings from 1930-1939. And George Orwell's The Road to Wigan Pier about life in the coal mines of South Leeds.

A 1930s scrapbook showed common household items and magazines of the time. And Inside Europe by John Gunther, the October 1938 edition. That is a rare book, published just before WWII broke out, so it showed what the state of Europe was at that time without any skewed historical lens.

So, where does your novel start? Perhaps your non-fiction research can start there.

Look for unconventional books, rare books that can help you put a unique spin on the world you are attempting to create.

But what of fictional influences? I read other books of fiction before and during the writing of the novel, and these are listed below.

What fiction has influenced you to write the novel you are working on? Re-reading them might provide some fresh insights and inspiration, and infuse your book with renewed vitality.

Timothy Findley's The Wars . This was an interesting literary novel exploring the effects that WWI had on an empathetic main character. I once met with a publisher who said that Intervals of Hope shouldn't be published because The Wars was done so well. I disagree with his assessment, as under that presumption all writers should put their pens down based on the excellence of what's been done before.

Joseph Boyden's Three Day Road. Joseph drew upon family stories from his grandfather and uncle, who served as soldiers during WWI. For Intervals of Hope , I was provided with e ighty-five letters, which were sent home during WWI by my great-grandfather. These letters were discovered in a family attic, and form part of the novel.

Ken Follett's Fall of Giants and Winter of the World. This is a mass-market, sprawling epic focused on an assortment of characters in WWI and WWII. With the epic scope, the inner life of the characters was not explored in great detail, which is what I was after in my novel. However, these books provided interesting aspects of these times.

Want to write better short stories? Sign up for a 1-on-1 consultation with our short story expert, Author Tevis Shkodra .

Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls . Robert Jordan was an explosives expert with a mission to destroy a bridge in the Spanish Civil War. Pablo, the anti-fascist guerilla leader, and his wife Pilar are excellent secondary characters. A real inspiration.

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller. A very funny book set in Italy during World War II, this is the story of a bombardier, Yossarian, a hero who is furious because thousands of people he has never met are trying to kill him.

Roddy Doyle's A Star Called Henry about Henry Smart in the Irish Rebellion, which was quite comical at times. Well written, lively, not one I would have sought out but a reading suggestion from the publisher as I was engaging in rewrites. This is a real study in unique and bold characterization.

Stephen Crane's Red Badge of Courage was published thirty years after the American Civil War had ended, by a man who was born after the war. It was acclaimed for its realism by veterans of the war. So maybe you are attempting something similar with your novel, and it may be worth a read.

All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, about WWI from the German perspective. The idealism of youth turns sour from what they see and experience. Another story similar to The Wars , exploring the effect of war on the individual.

There was also a book on Canadians who deserted the battlefields during WWI, which I found interesting and which forms part of the conflict that two of the characters face in the novel.

So, that was my reading list. What is yours? Think about allocating space on your bookshelf for a reading list pertaining to your current novel. Refer to your books from time to time. Seek inspiration from them when needed. Immerse yourself in the world you are attempting to create.

Reading for research and inspiration is essential, to which any author can attest. Read what has been done before. Learn why it is considered great.

But what else gives authenticity and life to your novel?

Interviewing

In the course of writing Intervals of Hope , I wanted to get some details right. So, I contacted a man named George Sharp who lived in London, England between the wars. I was able to read his story online, and ask him questions about his life at that time.

Unlike the novel’s main character, George was a police officer. But he provided a lot of good input, clarifications, and details, and he seemed interested in sharing his memories and experience.

A key element of the novel is the father-son relationship. But originally, the father was not fully formed. He was a stale character , lacking any substance that would make for conflict between him and his son.

But then, I read about a man named Gordon Schottlander in a local newspaper. Gordon was a veteran of WWII who lived in London, England between the wars, and his father was a soldier in WWI. This paralleled the novel’s main character. So, I reached out to Gordon and he graciously agreed to be interviewed for the book. We had many wonderful conversations that I will always remember.

He attended the book launch. He read the book, and enjoyed it. There will be an interview with him and the publisher online, which is scheduled for early next month. Gordon was highly-trained as a British Commando, a special operations force formed by Churchill to engage in secretive and dangerous missions.

He was a commissioned officer who stormed the beaches on D-Day. He is an amazing and humble man and it's been a blessing to know him. And a lot of his story comes through in the book.

Gordon sharing his experiences with me enriched the novel in countless ways: his wartime experiences , living in London in the 1930s, and Gordon's relationship with his father. This is part of what provides the book with authenticity and makes it unique.

Look for opportunities that you may have to interview those who have lived the life of your characters, or can provide you with unique perspectives that will enrich your novel and bring it to life.

Letters and Correspondence

When searching for historical documents, look to libraries and public archives. Seek them out within your own family.

Look to others you know, or individuals you can contact about your subject. Pursue opportunities to obtain unknown historical documents.

While writing Intervals of Hope , I learned that e ighty-five letters sent home during WWI by my great-grandfather, Wilfrid Littlejohn, had been discovered in a family attic. Wilfrid was in E Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Brigade and was one of the first Canadians to be sent overseas and among the last to return. He was one of 70 out of 1000 men in his regiment to have survived.

The letters were sent home to Wilfrid's parents, his brother, and his aunt from the trenches, hospitals and camps. Some sections of the letters were scribbled over by censors who would review the letters prior to sending them.

Letters were censored during WWI to prevent the enemy from obtaining secret information about upcoming battles , numbers of troops in specific locations, etc. so I had to surmise what might be in those sections.

When I received the letters, they were digitized and arranged chronologically. So, I read through and then transcribed them. When looking at what to include in the novel, I went through what effect certain letters would be on the main character at specific points in his life, knowing what was happening in his country in the 1930s in England, and what was occurring in Germany, Italy, Spain, and Japan.

Seek out opportunities to find such documents to be utilized within your novel, or as reference or research material. Such documents can prove to be invaluable.

Travel can not only add realism to your novel through details, but it can also inspire you to get to the business of writing!

I travelled to London England many times and went around the city as the main character would have, visiting most of the places he frequented in the book. I took notes as I walked around, carefully documenting my surroundings and how these may have been perceived by the characters in the novel.

This helped inspire the story by allowing me to experience part of the life of the main character, and others.

Final Thoughts

Good research lends credibility to your work, and gives the reader the feeling of direct experience. Imagine your readers feeling that they have lived the life of your characters as they read your book, and have therefore had a direct experience. What about that for a goal?

As a last word, given direct or indirect experience, you will still need to:

- Read copiously. You should be interested enough in the research to read many books about your subject. Even boring books (for example, a book about the history of London, England) can also feed into your writing.

- Interview , if possible, to derive from first hand experiences of people who were there.

- Communicate with others who know about your subject.

- Research on your own . When researching online, know that some sources such as Wikipedia can be changed and are therefore potentially unreliable. I have found information on Wikipedia that could not be corroborated elsewhere.

- Travel to the places in your novel, if possible.

- Look at resources that are rarely used . In researching for an upcoming novel, I obtained a researcher card at the Toronto Library Archives and used a microfiche to get countless documents about my subject. I was able to learn about the basis for the main character of my novel.

- Don't get bogged down in research while you're writing . Focus on telling the story. Write out your scenes. See where more research is needed, and then add details utilizing research.

Now, get that novel going!

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in So You Want to Write? Blog

How to Leverage Social Media for Effective Book Marketing

August 29, 2024 5 min read

The 6 Basics In Your Successful Query Letter

July 12, 2024 5 min read

You did it, you’ve written your book. First of all, congratulations! Hopefully we will see it on store shelves very soon. The path to getting your book published can be daunting, and one of the key steps is mastering the art of the query letter. This letter is your introduction to literary agents and publishers, offering a snapshot of your book and a taste of your writing style. Your query letter is the key that can open the door to your publishing dreams.

In this article, we will explore five basic elements of a successful query letter that’ll give you the best chance of getting that book published.

9 Ways to Market Your First Book

May 30, 2024 6 min read

Have you ever wondered why some first-time authors gain a lot of attention while others don't? The secret often lies in how well they market their books.

For new authors, getting the hang of marketing can make a big difference. Having a solid plan to promote your book can really boost its success.

Take a course or find your coach today!

Helping Writers Become Authors

Write your best story. Change your life. Astound the world.

- Start Here!

- Story Structure Database

- Outlining Your Novel

- Story Structure

- Character Arcs

- Archetypal Characters

- Scene Structure

- Common Writing Mistakes

- Storytelling According to Marvel

- K.M. Weiland Site

Novel Research: 12 Ways to Ace Your Book