15 Research Methodology Examples

Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch)

Tio Gabunia is an academic writer and architect based in Tbilisi. He has studied architecture, design, and urban planning at the Georgian Technical University and the University of Lisbon. He has worked in these fields in Georgia, Portugal, and France. Most of Tio’s writings concern philosophy. Other writings include architecture, sociology, urban planning, and economics.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Research methodologies can roughly be categorized into three group: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods.

- Qualitative Research : This methodology is based on obtaining deep, contextualized, non-numerical data. It can occur, for example, through open-ended questioning of research particiapnts in order to understand human behavior. It’s all about describing and analyzing subjective phenomena such as emotions or experiences.

- Quantitative Research: This methodology is rationally-based and relies heavily on numerical analysis of empirical data . With quantitative research, you aim for objectivity by creating hypotheses and testing them through experiments or surveys, which allow for statistical analyses.

- Mixed-Methods Research: Mixed-methods research combines both previous types into one project. We have more flexibility when designing our research study with mixed methods since we can use multiple approaches depending on our needs at each time. Using mixed methods can help us validate our results and offer greater predictability than just either type of methodology alone could provide.

Below are research methodologies that fit into each category.

Qualitative Research Methodologies

1. case study.

Conducts an in-depth examination of a specific case, individual, or event to understand a phenomenon.

Instead of examining a whole population for numerical trend data, case study researchers seek in-depth explanations of one event.

The benefit of case study research is its ability to elucidate overlooked details of interesting cases of a phenomenon (Busetto, Wick & Gumbinger, 2020). It offers deep insights for empathetic, reflective, and thoughtful understandings of that phenomenon.

However, case study findings aren’t transferrable to new contexts or for population-wide predictions. Instead, they inform practitioner understandings for nuanced, deep approaches to future instances (Liamputtong, 2020).

2. Grounded Theory

Grounded theory involves generating hypotheses and theories through the collection and interpretation of data (Faggiolani, n.d.). Its distinguishing features is that it doesn’t test a hypothesis generated prior to analysis, but rather generates a hypothesis or ‘theory’ that emerges from the data.

It also involves the application of inductive reasoning and is often contrasted with the hypothetico-deductive model of scientific research. This research methodology was developed by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s (Glaser & Strauss, 2009).

The basic difference between traditional scientific approaches to research and grounded theory is that the latter begins with a question, then collects data, and the theoretical framework is said to emerge later from this data.

By contrast, scientists usually begin with an existing theoretical framework , develop hypotheses, and only then start collecting data to verify or falsify the hypotheses.

3. Ethnography

In ethnographic research , the researcher immerses themselves within the group they are studying, often for long periods of time.

This type of research aims to understand the shared beliefs, practices, and values of a particular community by immersing the researcher within the cultural group.

Although ethnographic research cannot predict or identify trends in an entire population, it can create detailed explanations of cultural practices and comparisons between social and cultural groups.

When a person conducts an ethnographic study of themselves or their own culture, it can be considered autoethnography .

Its strength lies in producing comprehensive accounts of groups of people and their interactions.

Common methods researchers use during an ethnographic study include participant observation , thick description, unstructured interviews, and field notes vignettes. These methods can provide detailed and contextualized descriptions of their subjects.

Example Study

Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street by Karen Ho involves an anthropologist who embeds herself with Wall Street firms to study the culture of Wall Street bankers and how this culture affects the broader economy and world.

4. Phenomenology

Phenomenology to understand and describe individuals’ lived experiences concerning a specific phenomenon.

As a research methodology typically used in the social sciences , phenomenology involves the study of social reality as a product of intersubjectivity (the intersection of people’s cognitive perspectives) (Zahavi & Overgaard, n.d.).

This philosophical approach was first developed by Edmund Husserl.

5. Narrative Research

Narrative research explores personal stories and experiences to understand their meanings and interpretations.

It is also known as narrative inquiry and narrative analysis(Riessman, 1993).

This approach to research uses qualitative material like journals, field notes, letters, interviews, texts, photos, etc., as its data.

It is aimed at understanding the way people create meaning through narratives (Clandinin & Connelly, 2004).

6. Discourse Analysis

A discourse analysis examines the structure, patterns, and functions of language in context to understand how the text produces social constructs.

This methodology is common in critical theory , poststructuralism , and postmodernism. Its aim is to understand how language constructs discourses (roughly interpreted as “ways of thinking and constructing knowledge”).

As a qualitative methodology , its focus is on developing themes through close textual analysis rather than using numerical methods. Common methods for extracting data include semiotics and linguistic analysis.

7. Action Research

Action research involves researchers working collaboratively with stakeholders to address problems, develop interventions, and evaluate effectiveness.

Action research is a methodology and philosophy of research that is common in the social sciences.

The term was first coined in 1944 by Kurt Lewin, a German-American psychologist who also introduced applied research and group communication (Altrichter & Gstettner, 1993).

Lewin originally defined action research as involving two primary processes: taking action and doing research (Lewin, 1946).

Action research involves planning, action, and information-seeking about the result of the action.

Since Lewin’s original formulation, many different theoretical approaches to action research have been developed. These include action science, participatory action research, cooperative inquiry, and living educational theory among others.

Using Digital Sandbox Gaming to Improve Creativity Within Boys’ Writing (Ellison & Drew, 2019) is a study conducted by a school teacher who used video games to help teach his students English. It involved action research, where he interviewed his students to see if the use of games as stimuli for storytelling helped draw them into the learning experience, and iterated on his teaching style based on their feedback (disclaimer: I am the second author of this study).

See More: Examples of Qualitative Research

Quantitative Research Methodologies

8. experimental design.

As the name suggests, this type of research is based on testing hypotheses in experimental settings by manipulating variables and observing their effects on other variables.

The main benefit lies in its ability to manipulate specific variables to determine their effect on outcomes which is a great method for those looking for causational links in their research.

This is common, for example, in high-school science labs, where students are asked to introduce a variable into a setting in order to examine its effect.

9. Non-Experimental Design

Non-experimental design observes and measures associations between variables without manipulating them.

It can take, for example, the form of a ‘fly on the wall’ observation of a phenomenon, allowing researchers to examine authentic settings and changes that occur naturally in the environment.

10. Cross-Sectional Design

Cross-sectional design involves analyzing variables pertaining to a specific time period and at that exact moment.

This approach allows for an extensive examination and comparison of distinct and independent subjects, thereby offering advantages over qualitative methodologies such as case studies or surveys.

While cross-sectional design can be extremely useful in taking a ‘snapshot in time’, as a standalone method, it is not useful for examining changes in subjects after an intervention. The next methodology addresses this issue.

The prime example of this type of study is a census. A population census is mailed out to every house in the country, and each household must complete the census on the same evening. This allows the government to gather a snapshot of the nation’s demographics, beliefs, religion, and so on.

11. Longitudinal Design

Longitudinal research gathers data from the same subjects over an extended period to analyze changes and development.

In contrast to cross-sectional tactics, longitudinal designs examine variables more than once, over a pre-determined time span, allowing for multiple data points to be taken at different times.

A cross-sectional design is also useful for examining cohort effects , by comparing differences or changes in multiple different generations’ beliefs over time.

With multiple data points collected over extended periods ,it’s possible to examine continuous changes within things like population dynamics or consumer behavior. This makes detailed analysis of change possible.

12. Quasi-Experimental Design

Quasi-experimental design involves manipulating variables for analysis, but uses pre-existing groups of subjects rather than random groups.

Because the groups of research participants already exist, they cannot be randomly assigned to a cohort as with a true experimental design study. This makes inferring a causal relationship more difficult, but is nonetheless often more feasible in real-life settings.

Quasi-experimental designs are generally considered inferior to true experimental designs.

13. Correlational Research

Correlational research examines the relationships between two or more variables, determining the strength and direction of their association.

Similar to quasi-experimental methods, this type of research focuses on relationship differences between variables.

This approach provides a fast and easy way to make initial hypotheses based on either positive or negative correlation trends that can be observed within dataset.

Methods used for data analysis may include statistic correlations such as Pearson’s or Spearman’s.

Mixed-Methods Research Methodologies

14. sequential explanatory design (quan→qual).

This methodology involves conducting quantitative analysis first, then supplementing it with a qualitative study.

It begins by collecting quantitative data that is then analyzed to determine any significant patterns or trends.

Secondly, qualitative methods are employed. Their intent is to help interpret and expand the quantitative results.

This offers greater depth into understanding both large and smaller aspects of research questions being addressed.

The rationale behind this approach is to ensure that your data collection generates richer context for gaining insight into the particular issue across different levels, integrating in one study, qualitative exploration as well as statistical procedures.

15. Sequential Exploratory Design (QUAL→QUAN)

This methodology goes in the other direction, starting with qualitative analysis and ending with quantitative analysis.

It starts with qualitative research that delves deeps into complex areas and gathers rich information through interviewing or observing participants.

After this stage of exploration comes to an end, quantitative techniques are used to analyze the collected data through inferential statistics.

The idea is that a qualitative study can arm the researchers with a strong hypothesis testing framework, which they can then apply to a larger sample size using qualitative methods.

When I first took research classes, I had a lot of trouble distinguishing between methodologies and methods.

The key is to remember that the methodology sets the direction, while the methods are the specific tools to be used. A good analogy is transport: first you need to choose a mode (public transport, private transport, motorized transit, non-motorized transit), then you can choose a tool (bus, car, bike, on foot).

While research methodologies can be split into three types, each type has many different nuanced methodologies that can be chosen, before you then choose the methods – or tools – to use in the study. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses, so choose wisely!

Altrichter, H., & Gstettner, P. (1993). Action Research: A closed chapter in the history of German social science? Educational Action Research , 1 (3), 329–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965079930010302

Audi, R. (1999). The Cambridge dictionary of philosophy . Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press. http://archive.org/details/cambridgediction00audi

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2004). Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research . John Wiley & Sons.

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research . Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall.

Faggiolani, C. (n.d.). Perceived Identity: Applying Grounded Theory in Libraries . https://doi.org/10.4403/jlis.it-4592

Gauch, H. G. (2002). Scientific Method in Practice . Cambridge University Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2009). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . Transaction Publishers.

Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques . New Age International.

Kuada, J. (2012). Research Methodology: A Project Guide for University Students . Samfundslitteratur.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues , 2, 4 , 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2006). The Development of Constructivist Grounded Theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 5 (1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500103

Mingers, J., & Willcocks, L. (2017). An integrative semiotic methodology for IS research. Information and Organization , 27 (1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2016.12.001

OECD. (2015). Frascati Manual 2015: Guidelines for Collecting and Reporting Data on Research and Experimental Development . Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/frascati-manual-2015_9789264239012-en

Peirce, C. S. (1992). The Essential Peirce, Volume 1: Selected Philosophical Writings (1867–1893) . Indiana University Press.

Reese, W. L. (1980). Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion: Eastern and Western Thought . Humanities Press.

Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis . Sage Publications, Inc.

Saussure, F. de, & Riedlinger, A. (1959). Course in General Linguistics . Philosophical Library.

Thomas, C. G. (2021). Research Methodology and Scientific Writing . Springer Nature.

Zahavi, D., & Overgaard, S. (n.d.). Phenomenological Sociology—The Subjectivity of Everyday Life .

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 6 Types of Societies (With 21 Examples)

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Public Health Policy Examples

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Cultural Differences Examples

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link Social Interaction Types & Examples (Sociology)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Table of Contents

Research Report

Definition:

Research Report is a written document that presents the results of a research project or study, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions, in a clear and objective manner.

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the findings of the research to the intended audience, which could be other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public.

Components of Research Report

Components of Research Report are as follows:

Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for the research report and provides a brief overview of the research question or problem being investigated. It should include a clear statement of the purpose of the study and its significance or relevance to the field of research. It may also provide background information or a literature review to help contextualize the research.

Literature Review

The literature review provides a critical analysis and synthesis of the existing research and scholarship relevant to the research question or problem. It should identify the gaps, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the literature and show how the current study addresses these issues. The literature review also establishes the theoretical framework or conceptual model that guides the research.

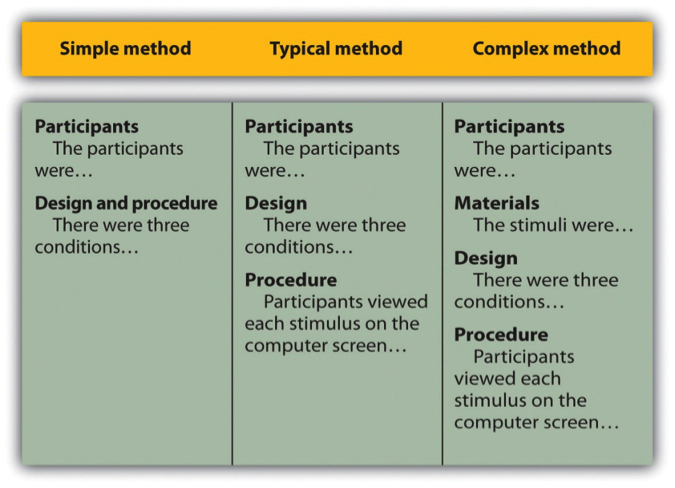

Methodology

The methodology section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used to collect and analyze data. It should include information on the sample or participants, data collection instruments, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques. The methodology should be clear and detailed enough to allow other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the study in a clear and objective manner. It should provide a detailed description of the data and statistics used to answer the research question or test the hypothesis. Tables, graphs, and figures may be included to help visualize the data and illustrate the key findings.

The discussion section interprets the results of the study and explains their significance or relevance to the research question or problem. It should also compare the current findings with those of previous studies and identify the implications for future research or practice. The discussion should be based on the results presented in the previous section and should avoid speculation or unfounded conclusions.

The conclusion summarizes the key findings of the study and restates the main argument or thesis presented in the introduction. It should also provide a brief overview of the contributions of the study to the field of research and the implications for practice or policy.

The references section lists all the sources cited in the research report, following a specific citation style, such as APA or MLA.

The appendices section includes any additional material, such as data tables, figures, or instruments used in the study, that could not be included in the main text due to space limitations.

Types of Research Report

Types of Research Report are as follows:

Thesis is a type of research report. A thesis is a long-form research document that presents the findings and conclusions of an original research study conducted by a student as part of a graduate or postgraduate program. It is typically written by a student pursuing a higher degree, such as a Master’s or Doctoral degree, although it can also be written by researchers or scholars in other fields.

Research Paper

Research paper is a type of research report. A research paper is a document that presents the results of a research study or investigation. Research papers can be written in a variety of fields, including science, social science, humanities, and business. They typically follow a standard format that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion sections.

Technical Report

A technical report is a detailed report that provides information about a specific technical or scientific problem or project. Technical reports are often used in engineering, science, and other technical fields to document research and development work.

Progress Report

A progress report provides an update on the progress of a research project or program over a specific period of time. Progress reports are typically used to communicate the status of a project to stakeholders, funders, or project managers.

Feasibility Report

A feasibility report assesses the feasibility of a proposed project or plan, providing an analysis of the potential risks, benefits, and costs associated with the project. Feasibility reports are often used in business, engineering, and other fields to determine the viability of a project before it is undertaken.

Field Report

A field report documents observations and findings from fieldwork, which is research conducted in the natural environment or setting. Field reports are often used in anthropology, ecology, and other social and natural sciences.

Experimental Report

An experimental report documents the results of a scientific experiment, including the hypothesis, methods, results, and conclusions. Experimental reports are often used in biology, chemistry, and other sciences to communicate the results of laboratory experiments.

Case Study Report

A case study report provides an in-depth analysis of a specific case or situation, often used in psychology, social work, and other fields to document and understand complex cases or phenomena.

Literature Review Report

A literature review report synthesizes and summarizes existing research on a specific topic, providing an overview of the current state of knowledge on the subject. Literature review reports are often used in social sciences, education, and other fields to identify gaps in the literature and guide future research.

Research Report Example

Following is a Research Report Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Academic Performance among High School Students

This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students. The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The findings indicate that there is a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students. The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers, as they highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities.

Introduction:

Social media has become an integral part of the lives of high school students. With the widespread use of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat, students can connect with friends, share photos and videos, and engage in discussions on a range of topics. While social media offers many benefits, concerns have been raised about its impact on academic performance. Many studies have found a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance among high school students (Kirschner & Karpinski, 2010; Paul, Baker, & Cochran, 2012).

Given the growing importance of social media in the lives of high school students, it is important to investigate its impact on academic performance. This study aims to address this gap by examining the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students.

Methodology:

The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The questionnaire was developed based on previous studies and was designed to measure the frequency and duration of social media use, as well as academic performance.

The participants were selected using a convenience sampling technique, and the survey questionnaire was distributed in the classroom during regular school hours. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

The findings indicate that the majority of high school students use social media platforms on a daily basis, with Facebook being the most popular platform. The results also show a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students.

Discussion:

The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. The negative correlation between social media use and academic performance suggests that strategies should be put in place to help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. For example, educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this study provides evidence of the negative impact of social media on academic performance among high school students. The findings highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. Further research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which social media use affects academic performance and to develop effective strategies for addressing this issue.

Limitations:

One limitation of this study is the use of convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future studies should use random sampling techniques to increase the representativeness of the sample. Another limitation is the use of self-reported measures, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Future studies could use objective measures of social media use and academic performance, such as tracking software and school records.

Implications:

The findings of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. Educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. For example, teachers could use social media platforms to share relevant educational resources and facilitate online discussions. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. They could also engage in open communication with their children to understand their social media use and its impact on their academic performance. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students. For example, schools could implement social media policies that restrict access during class time and encourage responsible use.

References:

- Kirschner, P. A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2010). Facebook® and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1237-1245.

- Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Journal of the Research Center for Educational Technology, 8(1), 1-19.

- Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(10), 652-657.

- Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., & Cheever, N. A. (2013). Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 948-958.

Note*: Above mention, Example is just a sample for the students’ guide. Do not directly copy and paste as your College or University assignment. Kindly do some research and Write your own.

Applications of Research Report

Research reports have many applications, including:

- Communicating research findings: The primary application of a research report is to communicate the results of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public. The report serves as a way to share new knowledge, insights, and discoveries with others in the field.

- Informing policy and practice : Research reports can inform policy and practice by providing evidence-based recommendations for decision-makers. For example, a research report on the effectiveness of a new drug could inform regulatory agencies in their decision-making process.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research in a particular area. Other researchers may use the findings and methodology of a report to develop new research questions or to build on existing research.

- Evaluating programs and interventions : Research reports can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and interventions in achieving their intended outcomes. For example, a research report on a new educational program could provide evidence of its impact on student performance.

- Demonstrating impact : Research reports can be used to demonstrate the impact of research funding or to evaluate the success of research projects. By presenting the findings and outcomes of a study, research reports can show the value of research to funders and stakeholders.

- Enhancing professional development : Research reports can be used to enhance professional development by providing a source of information and learning for researchers and practitioners in a particular field. For example, a research report on a new teaching methodology could provide insights and ideas for educators to incorporate into their own practice.

How to write Research Report

Here are some steps you can follow to write a research report:

- Identify the research question: The first step in writing a research report is to identify your research question. This will help you focus your research and organize your findings.

- Conduct research : Once you have identified your research question, you will need to conduct research to gather relevant data and information. This can involve conducting experiments, reviewing literature, or analyzing data.

- Organize your findings: Once you have gathered all of your data, you will need to organize your findings in a way that is clear and understandable. This can involve creating tables, graphs, or charts to illustrate your results.

- Write the report: Once you have organized your findings, you can begin writing the report. Start with an introduction that provides background information and explains the purpose of your research. Next, provide a detailed description of your research methods and findings. Finally, summarize your results and draw conclusions based on your findings.

- Proofread and edit: After you have written your report, be sure to proofread and edit it carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, and make sure that your report is well-organized and easy to read.

- Include a reference list: Be sure to include a list of references that you used in your research. This will give credit to your sources and allow readers to further explore the topic if they choose.

- Format your report: Finally, format your report according to the guidelines provided by your instructor or organization. This may include formatting requirements for headings, margins, fonts, and spacing.

Purpose of Research Report

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the results of a research study to a specific audience, such as peers in the same field, stakeholders, or the general public. The report provides a detailed description of the research methods, findings, and conclusions.

Some common purposes of a research report include:

- Sharing knowledge: A research report allows researchers to share their findings and knowledge with others in their field. This helps to advance the field and improve the understanding of a particular topic.

- Identifying trends: A research report can identify trends and patterns in data, which can help guide future research and inform decision-making.

- Addressing problems: A research report can provide insights into problems or issues and suggest solutions or recommendations for addressing them.

- Evaluating programs or interventions : A research report can evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions, which can inform decision-making about whether to continue, modify, or discontinue them.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies.

When to Write Research Report

A research report should be written after completing the research study. This includes collecting data, analyzing the results, and drawing conclusions based on the findings. Once the research is complete, the report should be written in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

In academic settings, research reports are often required as part of coursework or as part of a thesis or dissertation. In this case, the report should be written according to the guidelines provided by the instructor or institution.

In other settings, such as in industry or government, research reports may be required to inform decision-making or to comply with regulatory requirements. In these cases, the report should be written as soon as possible after the research is completed in order to inform decision-making in a timely manner.

Overall, the timing of when to write a research report depends on the purpose of the research, the expectations of the audience, and any regulatory requirements that need to be met. However, it is important to complete the report in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

Characteristics of Research Report

There are several characteristics of a research report that distinguish it from other types of writing. These characteristics include:

- Objective: A research report should be written in an objective and unbiased manner. It should present the facts and findings of the research study without any personal opinions or biases.

- Systematic: A research report should be written in a systematic manner. It should follow a clear and logical structure, and the information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand and follow.

- Detailed: A research report should be detailed and comprehensive. It should provide a thorough description of the research methods, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research report should be accurate and based on sound research methods. The findings and conclusions should be supported by data and evidence.

- Organized: A research report should be well-organized. It should include headings and subheadings to help the reader navigate the report and understand the main points.

- Clear and concise: A research report should be written in clear and concise language. The information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand, and unnecessary jargon should be avoided.

- Citations and references: A research report should include citations and references to support the findings and conclusions. This helps to give credit to other researchers and to provide readers with the opportunity to further explore the topic.

Advantages of Research Report

Research reports have several advantages, including:

- Communicating research findings: Research reports allow researchers to communicate their findings to a wider audience, including other researchers, stakeholders, and the general public. This helps to disseminate knowledge and advance the understanding of a particular topic.

- Providing evidence for decision-making : Research reports can provide evidence to inform decision-making, such as in the case of policy-making, program planning, or product development. The findings and conclusions can help guide decisions and improve outcomes.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research on a particular topic. Other researchers can build on the findings and conclusions of the report, which can lead to further discoveries and advancements in the field.

- Demonstrating expertise: Research reports can demonstrate the expertise of the researchers and their ability to conduct rigorous and high-quality research. This can be important for securing funding, promotions, and other professional opportunities.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies. Producing a high-quality research report can help ensure compliance with these requirements.

Limitations of Research Report

Despite their advantages, research reports also have some limitations, including:

- Time-consuming: Conducting research and writing a report can be a time-consuming process, particularly for large-scale studies. This can limit the frequency and speed of producing research reports.

- Expensive: Conducting research and producing a report can be expensive, particularly for studies that require specialized equipment, personnel, or data. This can limit the scope and feasibility of some research studies.

- Limited generalizability: Research studies often focus on a specific population or context, which can limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or contexts.

- Potential bias : Researchers may have biases or conflicts of interest that can influence the findings and conclusions of the research study. Additionally, participants may also have biases or may not be representative of the larger population, which can limit the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Accessibility: Research reports may be written in technical or academic language, which can limit their accessibility to a wider audience. Additionally, some research may be behind paywalls or require specialized access, which can limit the ability of others to read and use the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Approach – Types Methods and Examples

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Literature Review – Types Writing Guide and...

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

Still have questions? Leave a comment

Add Comment

Checklist: Dissertation Proposal

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Examples: Edited Papers

Need editing and proofreading services, research methodology guide: writing tips, types, & examples.

- Tags: Academic Research , Research

No dissertation or research paper is complete without the research methodology section. Since this is the chapter where you explain how you carried out your research, this is where all the meat is! Here’s where you clearly lay out the steps you have taken to test your hypothesis or research problem.

Through this blog, we’ll unravel the complexities and meaning of research methodology in academic writing , from its fundamental principles and ethics to the diverse types of research methodology in use today. Alongside offering research methodology examples, we aim to guide you on how to write research methodology, ensuring your research endeavors are both impactful and impeccably grounded!

Ensure your research methodology is foolproof. Learn more

Let’s first take a closer look at a simple research methodology definition:

Defining what is research methodology

Research methodology is the set of procedures and techniques used to collect, analyze, and interpret data to understand and solve a research problem. Methodology in research not only includes the design and methods but also the basic principles that guide the choice of specific methods.

Grasping the concept of methodology in research is essential for students and scholars, as it demonstrates the thorough and structured method used to explore a hypothesis or research question. Understanding the definition of methodology in research aids in identifying the methods used to collect data. Be it through any type of research method approach, ensuring adherence to the proper research paper format is crucial.

Now let’s explore some research methodology types:

Types of research methodology

1. qualitative research methodology.

Qualitative research methodology is aimed at understanding concepts, thoughts, or experiences. This approach is descriptive and is often utilized to gather in-depth insights into people’s attitudes, behaviors, or cultures. Qualitative research methodology involves methods like interviews, focus groups, and observation. The strength of this methodology lies in its ability to provide contextual richness.

2. Quantitative research methodology

Quantitative research methodology, on the other hand, is focused on quantifying the problem by generating numerical data or data that can be transformed into usable statistics. It uses measurable data to formulate facts and uncover patterns in research. Quantitative research methodology typically involves surveys, experiments, or statistical analysis. This methodology is appreciated for its ability to produce objective results that are generalizable to a larger population.

3. Mixed-Methods research methodology

Mixed-methods research combines both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem. This approach leverages the strengths of both methodologies to provide a deeper insight into the research question of a research paper .

Research methodology vs. research methods

The research methodology or design is the overall strategy and rationale that you used to carry out the research. Whereas, research methods are the specific tools and processes you use to gather and understand the data you need to test your hypothesis.

Research methodology examples and application

To further understand research methodology, let’s explore some examples of research methodology:

a. Qualitative research methodology example: A study exploring the impact of author branding on author popularity might utilize in-depth interviews to gather personal experiences and perspectives.

b. Quantitative research methodology example: A research project investigating the effects of a book promotion technique on book sales could employ a statistical analysis of profit margins and sales before and after the implementation of the method.

c. Mixed-Methods research methodology example: A study examining the relationship between social media use and academic performance might combine both qualitative and quantitative approaches. It could include surveys to quantitatively assess the frequency of social media usage and its correlation with grades, alongside focus groups or interviews to qualitatively explore students’ perceptions and experiences regarding how social media affects their study habits and academic engagement.

These examples highlight the meaning of methodology in research and how it guides the research process, from data collection to analysis, ensuring the study’s objectives are met efficiently.

Importance of methodology in research papers

When it comes to writing your study, the methodology in research papers or a dissertation plays a pivotal role. A well-crafted methodology section of a research paper or thesis not only enhances the credibility of your research but also provides a roadmap for others to replicate or build upon your work.

How to structure the research methods chapter

Wondering how to write the research methodology section? Follow these steps to create a strong methods chapter:

Step 1: Explain your research methodology

At the start of a research paper , you would have provided the background of your research and stated your hypothesis or research problem. In this section, you will elaborate on your research strategy.

Begin by restating your research question and proceed to explain what type of research you opted for to test it. Depending on your research, here are some questions you can consider:

a. Did you use qualitative or quantitative data to test the hypothesis?

b. Did you perform an experiment where you collected data or are you writing a dissertation that is descriptive/theoretical without data collection?

c. Did you use primary data that you collected or analyze secondary research data or existing data as part of your study?

These questions will help you establish the rationale for your study on a broader level, which you will follow by elaborating on the specific methods you used to collect and understand your data.

Step 2: Explain the methods you used to test your hypothesis

Now that you have told your reader what type of research you’ve undertaken for the dissertation, it’s time to dig into specifics. State what specific methods you used and explain the conditions and variables involved. Explain what the theoretical framework behind the method was, what samples you used for testing it, and what tools and materials you used to collect the data.

Step 3: Explain how you analyzed the results

Once you have explained the data collection process, explain how you analyzed and studied the data. Here, your focus is simply to explain the methods of analysis rather than the results of the study.

Here are some questions you can answer at this stage:

a. What tools or software did you use to analyze your results?

b. What parameters or variables did you consider while understanding and studying the data you’ve collected?

c. Was your analysis based on a theoretical framework?

Your mode of analysis will change depending on whether you used a quantitative or qualitative research methodology in your study. If you’re working within the hard sciences or physical sciences, you are likely to use a quantitative research methodology (relying on numbers and hard data). If you’re doing a qualitative study, in the social sciences or humanities, your analysis may rely on understanding language and socio-political contexts around your topic. This is why it’s important to establish what kind of study you’re undertaking at the onset.

Step 4: Defend your choice of methodology

Now that you have gone through your research process in detail, you’ll also have to make a case for it. Justify your choice of methodology and methods, explaining why it is the best choice for your research question. This is especially important if you have chosen an unconventional approach or you’ve simply chosen to study an existing research problem from a different perspective. Compare it with other methodologies, especially ones attempted by previous researchers, and discuss what contributions using your methodology makes.

Step 5: Discuss the obstacles you encountered and how you overcame them

No matter how thorough a methodology is, it doesn’t come without its hurdles. This is a natural part of scientific research that is important to document so that your peers and future researchers are aware of it. Writing in a research paper about this aspect of your research process also tells your evaluator that you have actively worked to overcome the pitfalls that came your way and you have refined the research process.

Tips to write an effective methodology chapter

1. Remember who you are writing for. Keeping sight of the reader/evaluator will help you know what to elaborate on and what information they are already likely to have. You’re condensing months’ work of research in just a few pages, so you should omit basic definitions and information about general phenomena people already know.

2. Do not give an overly elaborate explanation of every single condition in your study.

3. Skip details and findings irrelevant to the results.

4. Cite references that back your claim and choice of methodology.

5. Consistently emphasize the relationship between your research question and the methodology you adopted to study it.

To sum it up, what is methodology in research? It’s the blueprint of your research, essential for ensuring that your study is systematic, rigorous, and credible. Whether your focus is on qualitative research methodology, quantitative research methodology, or a combination of both, understanding and clearly defining your methodology is key to the success of your research.

Once you write the research methodology and complete writing the entire research paper, the next step is to edit your paper. As experts in research paper editing and proofreading services , we’d love to help you perfect your paper!

Here are some other articles that you might find useful:

- Essential Research Tips for Essay Writing

- How to Write a Lab Report: Examples from Academic Editors

- The Essential Types of Editing Every Writer Needs to Know

- Editing and Proofreading Academic Papers: A Short Guide

- The Top 10 Editing and Proofreading Services of 2023

Frequently Asked Questions

What does research methodology mean, what types of research methodologies are there, what is qualitative research methodology, how to determine sample size in research methodology, what is action research methodology.

Found this article helpful?

One comment on “ Research Methodology Guide: Writing Tips, Types, & Examples ”

This is very simplified and direct. Very helpful to understand the research methodology section of a dissertation

Leave a Comment: Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Your vs. You’re: When to Use Your and You’re

Your organization needs a technical editor: here’s why, your guide to the best ebook readers in 2024, writing for the web: 7 expert tips for web content writing.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Get carefully curated resources about writing, editing, and publishing in the comfort of your inbox.

How to Copyright Your Book?

If you’ve thought about copyrighting your book, you’re on the right path.

© 2024 All rights reserved

- Terms of service

- Privacy policy

- Self Publishing Guide

- Pre-Publishing Steps

- Fiction Writing Tips

- Traditional Publishing

- Additional Resources

- Dissertation Writing Guide

- Essay Writing Guide

- Academic Writing and Publishing

- Citation and Referencing

- Partner with us

- Annual report

- Website content

- Marketing material

- Job Applicant

- Cover letter

- Resource Center

- Case studies

What Is Research Methodology?

I f you’re new to formal academic research, it’s quite likely that you’re feeling a little overwhelmed by all the technical lingo that gets thrown around. And who could blame you – “research methodology”, “research methods”, “sampling strategies”… it all seems never-ending!

In this post, we’ll demystify the landscape with plain-language explanations and loads of examples (including easy-to-follow videos), so that you can approach your dissertation, thesis or research project with confidence. Let’s get started.

Research Methodology 101

- What exactly research methodology means

- What qualitative , quantitative and mixed methods are

- What sampling strategy is

- What data collection methods are

- What data analysis methods are

- How to choose your research methodology

- Example of a research methodology

What is research methodology?

Research methodology simply refers to the practical “how” of a research study. More specifically, it’s about how a researcher systematically designs a study to ensure valid and reliable results that address the research aims, objectives and research questions . Specifically, how the researcher went about deciding:

- What type of data to collect (e.g., qualitative or quantitative data )

- Who to collect it from (i.e., the sampling strategy )

- How to collect it (i.e., the data collection method )

- How to analyse it (i.e., the data analysis methods )

Within any formal piece of academic research (be it a dissertation, thesis or journal article), you’ll find a research methodology chapter or section which covers the aspects mentioned above. Importantly, a good methodology chapter explains not just what methodological choices were made, but also explains why they were made. In other words, the methodology chapter should justify the design choices, by showing that the chosen methods and techniques are the best fit for the research aims, objectives and research questions.

So, it’s the same as research design?

Not quite. As we mentioned, research methodology refers to the collection of practical decisions regarding what data you’ll collect, from who, how you’ll collect it and how you’ll analyse it. Research design, on the other hand, is more about the overall strategy you’ll adopt in your study. For example, whether you’ll use an experimental design in which you manipulate one variable while controlling others. You can learn more about research design and the various design types here .

Need a helping hand?

What are qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods?

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods are different types of methodological approaches, distinguished by their focus on words , numbers or both . This is a bit of an oversimplification, but its a good starting point for understanding.

Let’s take a closer look.

Qualitative research refers to research which focuses on collecting and analysing words (written or spoken) and textual or visual data, whereas quantitative research focuses on measurement and testing using numerical data . Qualitative analysis can also focus on other “softer” data points, such as body language or visual elements.

It’s quite common for a qualitative methodology to be used when the research aims and research questions are exploratory in nature. For example, a qualitative methodology might be used to understand peoples’ perceptions about an event that took place, or a political candidate running for president.

Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and research questions are confirmatory in nature. For example, a quantitative methodology might be used to measure the relationship between two variables (e.g. personality type and likelihood to commit a crime) or to test a set of hypotheses .

As you’ve probably guessed, the mixed-method methodology attempts to combine the best of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies to integrate perspectives and create a rich picture. If you’d like to learn more about these three methodological approaches, be sure to watch our explainer video below.

What is sampling strategy?

Simply put, sampling is about deciding who (or where) you’re going to collect your data from . Why does this matter? Well, generally it’s not possible to collect data from every single person in your group of interest (this is called the “population”), so you’ll need to engage a smaller portion of that group that’s accessible and manageable (this is called the “sample”).

How you go about selecting the sample (i.e., your sampling strategy) will have a major impact on your study. There are many different sampling methods you can choose from, but the two overarching categories are probability sampling and non-probability sampling .

Probability sampling involves using a completely random sample from the group of people you’re interested in. This is comparable to throwing the names all potential participants into a hat, shaking it up, and picking out the “winners”. By using a completely random sample, you’ll minimise the risk of selection bias and the results of your study will be more generalisable to the entire population.

Non-probability sampling , on the other hand, doesn’t use a random sample . For example, it might involve using a convenience sample, which means you’d only interview or survey people that you have access to (perhaps your friends, family or work colleagues), rather than a truly random sample. With non-probability sampling, the results are typically not generalisable .

To learn more about sampling methods, be sure to check out the video below.

What are data collection methods?

As the name suggests, data collection methods simply refers to the way in which you go about collecting the data for your study. Some of the most common data collection methods include:

- Interviews (which can be unstructured, semi-structured or structured)

- Focus groups and group interviews

- Surveys (online or physical surveys)

- Observations (watching and recording activities)

- Biophysical measurements (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, etc.)

- Documents and records (e.g., financial reports, court records, etc.)

The choice of which data collection method to use depends on your overall research aims and research questions , as well as practicalities and resource constraints. For example, if your research is exploratory in nature, qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups would likely be a good fit. Conversely, if your research aims to measure specific variables or test hypotheses, large-scale surveys that produce large volumes of numerical data would likely be a better fit.

What are data analysis methods?

Data analysis methods refer to the methods and techniques that you’ll use to make sense of your data. These can be grouped according to whether the research is qualitative (words-based) or quantitative (numbers-based).

Popular data analysis methods in qualitative research include:

- Qualitative content analysis

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Narrative analysis

- Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA)

- Visual analysis (of photographs, videos, art, etc.)

Qualitative data analysis all begins with data coding , after which an analysis method is applied. In some cases, more than one analysis method is used, depending on the research aims and research questions . In the video below, we explore some common qualitative analysis methods, along with practical examples.

- Descriptive statistics (e.g. means, medians, modes )

- Inferential statistics (e.g. correlation, regression, structural equation modelling)

How do I choose a research methodology?

As you’ve probably picked up by now, your research aims and objectives have a major influence on the research methodology . So, the starting point for developing your research methodology is to take a step back and look at the big picture of your research, before you make methodology decisions. The first question you need to ask yourself is whether your research is exploratory or confirmatory in nature.

If your research aims and objectives are primarily exploratory in nature, your research will likely be qualitative and therefore you might consider qualitative data collection methods (e.g. interviews) and analysis methods (e.g. qualitative content analysis).

Conversely, if your research aims and objective are looking to measure or test something (i.e. they’re confirmatory), then your research will quite likely be quantitative in nature, and you might consider quantitative data collection methods (e.g. surveys) and analyses (e.g. statistical analysis).

Designing your research and working out your methodology is a large topic, which we cover extensively on the blog . For now, however, the key takeaway is that you should always start with your research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread). Every methodological choice you make needs align with those three components.

Example of a research methodology chapter

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of a research methodology from an actual dissertation, as well as an overview of our free methodology template .

Learn More About Methodology

Triangulation: The Ultimate Credibility Enhancer

Triangulation is one of the best ways to enhance the credibility of your research. Learn about the different options here.

Research Limitations 101: What You Need To Know

Learn everything you need to know about research limitations (AKA limitations of the study). Includes practical examples from real studies.

In Vivo Coding 101: Full Explainer With Examples

Learn about in vivo coding, a popular qualitative coding technique ideal for studies where the nuances of language are central to the aims.

Process Coding 101: Full Explainer With Examples

Learn about process coding, a popular qualitative coding technique ideal for studies exploring processes, actions and changes over time.

Qualitative Coding 101: Inductive, Deductive & Hybrid Coding

Inductive, Deductive & Abductive Coding Qualitative Coding Approaches Explained...

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

199 Comments

Thank you for this simple yet comprehensive and easy to digest presentation. God Bless!

You’re most welcome, Leo. Best of luck with your research!

I found it very useful. many thanks

This is really directional. A make-easy research knowledge.

Thank you for this, I think will help my research proposal

Thanks for good interpretation,well understood.

Good morning sorry I want to the search topic

Thank u more

Thank you, your explanation is simple and very helpful.

Very educative a.nd exciting platform. A bigger thank you and I’ll like to always be with you

That’s the best analysis

So simple yet so insightful. Thank you.

This really easy to read as it is self-explanatory. Very much appreciated…

Thanks for this. It’s so helpful and explicit. For those elements highlighted in orange, they were good sources of referrals for concepts I didn’t understand. A million thanks for this.

Good morning, I have been reading your research lessons through out a period of times. They are important, impressive and clear. Want to subscribe and be and be active with you.

Thankyou So much Sir Derek…

Good morning thanks so much for the on line lectures am a student of university of Makeni.select a research topic and deliberate on it so that we’ll continue to understand more.sorry that’s a suggestion.

Beautiful presentation. I love it.

please provide a research mehodology example for zoology

It’s very educative and well explained

Thanks for the concise and informative data.

This is really good for students to be safe and well understand that research is all about

Thank you so much Derek sir🖤🙏🤗

Very simple and reliable

This is really helpful. Thanks alot. God bless you.

very useful, Thank you very much..

thanks a lot its really useful

in a nutshell..thank you!

Thanks for updating my understanding on this aspect of my Thesis writing.

thank you so much my through this video am competently going to do a good job my thesis

Thanks a lot. Very simple to understand. I appreciate 🙏

Very simple but yet insightful Thank you

This has been an eye opening experience. Thank you grad coach team.

Very useful message for research scholars

Really very helpful thank you

yes you are right and i’m left

Research methodology with a simplest way i have never seen before this article.

wow thank u so much

Good morning thanks so much for the on line lectures am a student of university of Makeni.select a research topic and deliberate on is so that we will continue to understand more.sorry that’s a suggestion.

Very precise and informative.

Thanks for simplifying these terms for us, really appreciate it.

Thanks this has really helped me. It is very easy to understand.

I found the notes and the presentation assisting and opening my understanding on research methodology

Good presentation

Im so glad you clarified my misconceptions. Im now ready to fry my onions. Thank you so much. God bless

Thank you a lot.

thanks for the easy way of learning and desirable presentation.

Thanks a lot. I am inspired

Well written

I am writing a APA Format paper . I using questionnaire with 120 STDs teacher for my participant. Can you write me mthology for this research. Send it through email sent. Just need a sample as an example please. My topic is ” impacts of overcrowding on students learning

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t write your methodology for you. If you’re looking for samples, you should be able to find some sample methodologies on Google. Alternatively, you can download some previous dissertations from a dissertation directory and have a look at the methodology chapters therein.

All the best with your research.

Thank you so much for this!! God Bless

Thank you. Explicit explanation

Thank you, Derek and Kerryn, for making this simple to understand. I’m currently at the inception stage of my research.

Thnks a lot , this was very usefull on my assignment

excellent explanation

I’m currently working on my master’s thesis, thanks for this! I’m certain that I will use Qualitative methodology.

Thanks a lot for this concise piece, it was quite relieving and helpful. God bless you BIG…

I am currently doing my dissertation proposal and I am sure that I will do quantitative research. Thank you very much it was extremely helpful.

Very interesting and informative yet I would like to know about examples of Research Questions as well, if possible.

I’m about to submit a research presentation, I have come to understand from your simplification on understanding research methodology. My research will be mixed methodology, qualitative as well as quantitative. So aim and objective of mixed method would be both exploratory and confirmatory. Thanks you very much for your guidance.

OMG thanks for that, you’re a life saver. You covered all the points I needed. Thank you so much ❤️ ❤️ ❤️

Thank you immensely for this simple, easy to comprehend explanation of data collection methods. I have been stuck here for months 😩. Glad I found your piece. Super insightful.

I’m going to write synopsis which will be quantitative research method and I don’t know how to frame my topic, can I kindly get some ideas..

Thanks for this, I was really struggling.

This was really informative I was struggling but this helped me.

Thanks a lot for this information, simple and straightforward. I’m a last year student from the University of South Africa UNISA South Africa.

its very much informative and understandable. I have enlightened.

An interesting nice exploration of a topic.

Thank you. Accurate and simple🥰

This article was really helpful, it helped me understanding the basic concepts of the topic Research Methodology. The examples were very clear, and easy to understand. I would like to visit this website again. Thank you so much for such a great explanation of the subject.

Thanks dude

Thank you Doctor Derek for this wonderful piece, please help to provide your details for reference purpose. God bless.

Many compliments to you

Great work , thank you very much for the simple explanation

Thank you. I had to give a presentation on this topic. I have looked everywhere on the internet but this is the best and simple explanation.

thank you, its very informative.

Well explained. Now I know my research methodology will be qualitative and exploratory. Thank you so much, keep up the good work

Well explained, thank you very much.

This is good explanation, I have understood the different methods of research. Thanks a lot.

Great work…very well explanation

Thanks Derek. Kerryn was just fantastic!

Great to hear that, Hyacinth. Best of luck with your research!

Its a good templates very attractive and important to PhD students and lectuter

Thanks for the feedback, Matobela. Good luck with your research methodology.

Thank you. This is really helpful.

You’re very welcome, Elie. Good luck with your research methodology.

Well explained thanks

This is a very helpful site especially for young researchers at college. It provides sufficient information to guide students and equip them with the necessary foundation to ask any other questions aimed at deepening their understanding.

Thanks for the kind words, Edward. Good luck with your research!

Thank you. I have learned a lot.

Great to hear that, Ngwisa. Good luck with your research methodology!

Thank you for keeping your presentation simples and short and covering key information for research methodology. My key takeaway: Start with defining your research objective the other will depend on the aims of your research question.

My name is Zanele I would like to be assisted with my research , and the topic is shortage of nursing staff globally want are the causes , effects on health, patients and community and also globally

Thanks for making it simple and clear. It greatly helped in understanding research methodology. Regards.

This is well simplified and straight to the point

Thank you Dr

I was given an assignment to research 2 publications and describe their research methodology? I don’t know how to start this task can someone help me?

Sure. You’re welcome to book an initial consultation with one of our Research Coaches to discuss how we can assist – https://gradcoach.com/book/new/ .

Thanks a lot I am relieved of a heavy burden.keep up with the good work

I’m very much grateful Dr Derek. I’m planning to pursue one of the careers that really needs one to be very much eager to know. There’s a lot of research to do and everything, but since I’ve gotten this information I will use it to the best of my potential.

Thank you so much, words are not enough to explain how helpful this session has been for me!

Thanks this has thought me alot.

Very concise and helpful. Thanks a lot

Thank Derek. This is very helpful. Your step by step explanation has made it easier for me to understand different concepts. Now i can get on with my research.

I wish i had come across this sooner. So simple but yet insightful

really nice explanation thank you so much

I’m so grateful finding this site, it’s really helpful…….every term well explained and provide accurate understanding especially to student going into an in-depth research for the very first time, even though my lecturer already explained this topic to the class, I think I got the clear and efficient explanation here, much thanks to the author.

It is very helpful material

I would like to be assisted with my research topic : Literature Review and research methodologies. My topic is : what is the relationship between unemployment and economic growth?

Its really nice and good for us.

THANKS SO MUCH FOR EXPLANATION, ITS VERY CLEAR TO ME WHAT I WILL BE DOING FROM NOW .GREAT READS.

Short but sweet.Thank you

Informative article. Thanks for your detailed information.

I’m currently working on my Ph.D. thesis. Thanks a lot, Derek and Kerryn, Well-organized sequences, facilitate the readers’ following.

great article for someone who does not have any background can even understand

I am a bit confused about research design and methodology. Are they the same? If not, what are the differences and how are they related?

Thanks in advance.

concise and informative.

Thank you very much

How can we site this article is Harvard style?

Very well written piece that afforded better understanding of the concept. Thank you!

Am a new researcher trying to learn how best to write a research proposal. I find your article spot on and want to download the free template but finding difficulties. Can u kindly send it to my email, the free download entitled, “Free Download: Research Proposal Template (with Examples)”.

Thank too much

Thank you very much for your comprehensive explanation about research methodology so I like to thank you again for giving us such great things.

Good very well explained.Thanks for sharing it.

Thank u sir, it is really a good guideline.

so helpful thank you very much.

Thanks for the video it was very explanatory and detailed, easy to comprehend and follow up. please, keep it up the good work

It was very helpful, a well-written document with precise information.

how do i reference this?

MLA Jansen, Derek, and Kerryn Warren. “What (Exactly) Is Research Methodology?” Grad Coach, June 2021, gradcoach.com/what-is-research-methodology/.

APA Jansen, D., & Warren, K. (2021, June). What (Exactly) Is Research Methodology? Grad Coach. https://gradcoach.com/what-is-research-methodology/

Your explanation is easily understood. Thank you

Very help article. Now I can go my methodology chapter in my thesis with ease

I feel guided ,Thank you

This simplification is very helpful. It is simple but very educative, thanks ever so much

The write up is informative and educative. It is an academic intellectual representation that every good researcher can find useful. Thanks

Wow, this is wonderful long live.

Nice initiative

thank you the video was helpful to me.

Thank you very much for your simple and clear explanations I’m really satisfied by the way you did it By now, I think I can realize a very good article by following your fastidious indications May God bless you

Thanks very much, it was very concise and informational for a beginner like me to gain an insight into what i am about to undertake. I really appreciate.

very informative sir, it is amazing to understand the meaning of question hidden behind that, and simple language is used other than legislature to understand easily. stay happy.

This one is really amazing. All content in your youtube channel is a very helpful guide for doing research. Thanks, GradCoach.

research methodologies

Please send me more information concerning dissertation research.

Nice piece of knowledge shared….. #Thump_UP

This is amazing, it has said it all. Thanks to Gradcoach

This is wonderful,very elaborate and clear.I hope to reach out for your assistance in my research very soon.

This is the answer I am searching about…

realy thanks a lot

Thank you very much for this awesome, to the point and inclusive article.

Thank you very much I need validity and reliability explanation I have exams

Thank you for a well explained piece. This will help me going forward.

Very simple and well detailed Many thanks

This is so very simple yet so very effective and comprehensive. An Excellent piece of work.

I wish I saw this earlier on! Great insights for a beginner(researcher) like me. Thanks a mil!

Thank you very much, for such a simplified, clear and practical step by step both for academic students and general research work. Holistic, effective to use and easy to read step by step. One can easily apply the steps in practical terms and produce a quality document/up-to standard

Thanks for simplifying these terms for us, really appreciated.

Thanks for a great work. well understood .

This was very helpful. It was simple but profound and very easy to understand. Thank you so much!

Great and amazing research guidelines. Best site for learning research

hello sir/ma’am, i didn’t find yet that what type of research methodology i am using. because i am writing my report on CSR and collect all my data from websites and articles so which type of methodology i should write in dissertation report. please help me. i am from India.

how does this really work?

perfect content, thanks a lot

As a researcher, I commend you for the detailed and simplified information on the topic in question. I would like to remain in touch for the sharing of research ideas on other topics. Thank you

Impressive. Thank you, Grad Coach 😍

Thank you Grad Coach for this piece of information. I have at least learned about the different types of research methodologies.

Very useful content with easy way