Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Non-Experimental Research

32 Observational Research

Learning objectives.

- List the various types of observational research methods and distinguish between each.

- Describe the strengths and weakness of each observational research method.

What Is Observational Research?

The term observational research is used to refer to several different types of non-experimental studies in which behavior is systematically observed and recorded. The goal of observational research is to describe a variable or set of variables. More generally, the goal is to obtain a snapshot of specific characteristics of an individual, group, or setting. As described previously, observational research is non-experimental because nothing is manipulated or controlled, and as such we cannot arrive at causal conclusions using this approach. The data that are collected in observational research studies are often qualitative in nature but they may also be quantitative or both (mixed-methods). There are several different types of observational methods that will be described below.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is an observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. Thus naturalistic observation is a type of field research (as opposed to a type of laboratory research). Jane Goodall’s famous research on chimpanzees is a classic example of naturalistic observation. Dr. Goodall spent three decades observing chimpanzees in their natural environment in East Africa. She examined such things as chimpanzee’s social structure, mating patterns, gender roles, family structure, and care of offspring by observing them in the wild. However, naturalistic observation could more simply involve observing shoppers in a grocery store, children on a school playground, or psychiatric inpatients in their wards. Researchers engaged in naturalistic observation usually make their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied. Such an approach is called disguised naturalistic observation . Ethically, this method is considered to be acceptable if the participants remain anonymous and the behavior occurs in a public setting where people would not normally have an expectation of privacy. Grocery shoppers putting items into their shopping carts, for example, are engaged in public behavior that is easily observable by store employees and other shoppers. For this reason, most researchers would consider it ethically acceptable to observe them for a study. On the other hand, one of the arguments against the ethicality of the naturalistic observation of “bathroom behavior” discussed earlier in the book is that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy even in a public restroom and that this expectation was violated.

In cases where it is not ethical or practical to conduct disguised naturalistic observation, researchers can conduct undisguised naturalistic observation where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior. However, one concern with undisguised naturalistic observation is reactivity. Reactivity refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior. In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, the concern with reactivity is that when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would. This type of reactivity is known as the Hawthorne effect . For instance, you may act much differently in a bar if you know that someone is observing you and recording your behaviors and this would invalidate the study. So disguised observation is less reactive and therefore can have higher validity because people are not aware that their behaviors are being observed and recorded. However, we now know that people often become used to being observed and with time they begin to behave naturally in the researcher’s presence. In other words, over time people habituate to being observed. Think about reality shows like Big Brother or Survivor where people are constantly being observed and recorded. While they may be on their best behavior at first, in a fairly short amount of time they are flirting, having sex, wearing next to nothing, screaming at each other, and occasionally behaving in ways that are embarrassing.

Participant Observation

Another approach to data collection in observational research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. Participant observation is very similar to naturalistic observation in that it involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. As with naturalistic observation, the data that are collected can include interviews (usually unstructured), notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The only difference between naturalistic observation and participant observation is that researchers engaged in participant observation become active members of the group or situations they are studying. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. Like naturalistic observation, participant observation can be either disguised or undisguised. In disguised participant observation , the researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

In a famous example of disguised participant observation, Leon Festinger and his colleagues infiltrated a doomsday cult known as the Seekers, whose members believed that the apocalypse would occur on December 21, 1954. Interested in studying how members of the group would cope psychologically when the prophecy inevitably failed, they carefully recorded the events and reactions of the cult members in the days before and after the supposed end of the world. Unsurprisingly, the cult members did not give up their belief but instead convinced themselves that it was their faith and efforts that saved the world from destruction. Festinger and his colleagues later published a book about this experience, which they used to illustrate the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1956) [1] .

In contrast with undisguised participant observation , the researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation. Once again there are important ethical issues to consider with disguised participant observation. First no informed consent can be obtained and second deception is being used. The researcher is deceiving the participants by intentionally withholding information about their motivations for being a part of the social group they are studying. But sometimes disguised participation is the only way to access a protective group (like a cult). Further, disguised participant observation is less prone to reactivity than undisguised participant observation.

Rosenhan’s study (1973) [2] of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward would be considered disguised participant observation because Rosenhan and his pseudopatients were admitted into psychiatric hospitals on the pretense of being patients so that they could observe the way that psychiatric patients are treated by staff. The staff and other patients were unaware of their true identities as researchers.

Another example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins on a university-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008) [3] . Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

One of the primary benefits of participant observation is that the researchers are in a much better position to understand the viewpoint and experiences of the people they are studying when they are a part of the social group. The primary limitation with this approach is that the mere presence of the observer could affect the behavior of the people being observed. While this is also a concern with naturalistic observation, additional concerns arise when researchers become active members of the social group they are studying because that they may change the social dynamics and/or influence the behavior of the people they are studying. Similarly, if the researcher acts as a participant observer there can be concerns with biases resulting from developing relationships with the participants. Concretely, the researcher may become less objective resulting in more experimenter bias.

Structured Observation

Another observational method is structured observation . Here the investigator makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation. Often the setting in which the observations are made is not the natural setting. Instead, the researcher may observe people in the laboratory environment. Alternatively, the researcher may observe people in a natural setting (like a classroom setting) that they have structured some way, for instance by introducing some specific task participants are to engage in or by introducing a specific social situation or manipulation.

Structured observation is very similar to naturalistic observation and participant observation in that in all three cases researchers are observing naturally occurring behavior; however, the emphasis in structured observation is on gathering quantitative rather than qualitative data. Researchers using this approach are interested in a limited set of behaviors. This allows them to quantify the behaviors they are observing. In other words, structured observation is less global than naturalistic or participant observation because the researcher engaged in structured observations is interested in a small number of specific behaviors. Therefore, rather than recording everything that happens, the researcher only focuses on very specific behaviors of interest.

Researchers Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan used structured observation to study differences in the “pace of life” across countries (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999) [4] . One of their measures involved observing pedestrians in a large city to see how long it took them to walk 60 feet. They found that people in some countries walked reliably faster than people in other countries. For example, people in Canada and Sweden covered 60 feet in just under 13 seconds on average, while people in Brazil and Romania took close to 17 seconds. When structured observation takes place in the complex and even chaotic “real world,” the questions of when, where, and under what conditions the observations will be made, and who exactly will be observed are important to consider. Levine and Norenzayan described their sampling process as follows:

“Male and female walking speed over a distance of 60 feet was measured in at least two locations in main downtown areas in each city. Measurements were taken during main business hours on clear summer days. All locations were flat, unobstructed, had broad sidewalks, and were sufficiently uncrowded to allow pedestrians to move at potentially maximum speeds. To control for the effects of socializing, only pedestrians walking alone were used. Children, individuals with obvious physical handicaps, and window-shoppers were not timed. Thirty-five men and 35 women were timed in most cities.” (p. 186).

Precise specification of the sampling process in this way makes data collection manageable for the observers, and it also provides some control over important extraneous variables. For example, by making their observations on clear summer days in all countries, Levine and Norenzayan controlled for effects of the weather on people’s walking speeds. In Levine and Norenzayan’s study, measurement was relatively straightforward. They simply measured out a 60-foot distance along a city sidewalk and then used a stopwatch to time participants as they walked over that distance.

As another example, researchers Robert Kraut and Robert Johnston wanted to study bowlers’ reactions to their shots, both when they were facing the pins and then when they turned toward their companions (Kraut & Johnston, 1979) [5] . But what “reactions” should they observe? Based on previous research and their own pilot testing, Kraut and Johnston created a list of reactions that included “closed smile,” “open smile,” “laugh,” “neutral face,” “look down,” “look away,” and “face cover” (covering one’s face with one’s hands). The observers committed this list to memory and then practiced by coding the reactions of bowlers who had been videotaped. During the actual study, the observers spoke into an audio recorder, describing the reactions they observed. Among the most interesting results of this study was that bowlers rarely smiled while they still faced the pins. They were much more likely to smile after they turned toward their companions, suggesting that smiling is not purely an expression of happiness but also a form of social communication.

In yet another example (this one in a laboratory environment), Dov Cohen and his colleagues had observers rate the emotional reactions of participants who had just been deliberately bumped and insulted by a confederate after they dropped off a completed questionnaire at the end of a hallway. The confederate was posing as someone who worked in the same building and who was frustrated by having to close a file drawer twice in order to permit the participants to walk past them (first to drop off the questionnaire at the end of the hallway and once again on their way back to the room where they believed the study they signed up for was taking place). The two observers were positioned at different ends of the hallway so that they could read the participants’ body language and hear anything they might say. Interestingly, the researchers hypothesized that participants from the southern United States, which is one of several places in the world that has a “culture of honor,” would react with more aggression than participants from the northern United States, a prediction that was in fact supported by the observational data (Cohen, Nisbett, Bowdle, & Schwarz, 1996) [6] .

When the observations require a judgment on the part of the observers—as in the studies by Kraut and Johnston and Cohen and his colleagues—a process referred to as coding is typically required . Coding generally requires clearly defining a set of target behaviors. The observers then categorize participants individually in terms of which behavior they have engaged in and the number of times they engaged in each behavior. The observers might even record the duration of each behavior. The target behaviors must be defined in such a way that guides different observers to code them in the same way. This difficulty with coding illustrates the issue of interrater reliability, as mentioned in Chapter 4. Researchers are expected to demonstrate the interrater reliability of their coding procedure by having multiple raters code the same behaviors independently and then showing that the different observers are in close agreement. Kraut and Johnston, for example, video recorded a subset of their participants’ reactions and had two observers independently code them. The two observers showed that they agreed on the reactions that were exhibited 97% of the time, indicating good interrater reliability.

One of the primary benefits of structured observation is that it is far more efficient than naturalistic and participant observation. Since the researchers are focused on specific behaviors this reduces time and expense. Also, often times the environment is structured to encourage the behaviors of interest which again means that researchers do not have to invest as much time in waiting for the behaviors of interest to naturally occur. Finally, researchers using this approach can clearly exert greater control over the environment. However, when researchers exert more control over the environment it may make the environment less natural which decreases external validity. It is less clear for instance whether structured observations made in a laboratory environment will generalize to a real world environment. Furthermore, since researchers engaged in structured observation are often not disguised there may be more concerns with reactivity.

Case Studies

A case study is an in-depth examination of an individual. Sometimes case studies are also completed on social units (e.g., a cult) and events (e.g., a natural disaster). Most commonly in psychology, however, case studies provide a detailed description and analysis of an individual. Often the individual has a rare or unusual condition or disorder or has damage to a specific region of the brain.

Like many observational research methods, case studies tend to be more qualitative in nature. Case study methods involve an in-depth, and often a longitudinal examination of an individual. Depending on the focus of the case study, individuals may or may not be observed in their natural setting. If the natural setting is not what is of interest, then the individual may be brought into a therapist’s office or a researcher’s lab for study. Also, the bulk of the case study report will focus on in-depth descriptions of the person rather than on statistical analyses. With that said some quantitative data may also be included in the write-up of a case study. For instance, an individual’s depression score may be compared to normative scores or their score before and after treatment may be compared. As with other qualitative methods, a variety of different methods and tools can be used to collect information on the case. For instance, interviews, naturalistic observation, structured observation, psychological testing (e.g., IQ test), and/or physiological measurements (e.g., brain scans) may be used to collect information on the individual.

HM is one of the most notorious case studies in psychology. HM suffered from intractable and very severe epilepsy. A surgeon localized HM’s epilepsy to his medial temporal lobe and in 1953 he removed large sections of his hippocampus in an attempt to stop the seizures. The treatment was a success, in that it resolved his epilepsy and his IQ and personality were unaffected. However, the doctors soon realized that HM exhibited a strange form of amnesia, called anterograde amnesia. HM was able to carry out a conversation and he could remember short strings of letters, digits, and words. Basically, his short term memory was preserved. However, HM could not commit new events to memory. He lost the ability to transfer information from his short-term memory to his long term memory, something memory researchers call consolidation. So while he could carry on a conversation with someone, he would completely forget the conversation after it ended. This was an extremely important case study for memory researchers because it suggested that there’s a dissociation between short-term memory and long-term memory, it suggested that these were two different abilities sub-served by different areas of the brain. It also suggested that the temporal lobes are particularly important for consolidating new information (i.e., for transferring information from short-term memory to long-term memory).

The history of psychology is filled with influential cases studies, such as Sigmund Freud’s description of “Anna O.” (see Note 6.1 “The Case of “Anna O.””) and John Watson and Rosalie Rayner’s description of Little Albert (Watson & Rayner, 1920) [7] , who allegedly learned to fear a white rat—along with other furry objects—when the researchers repeatedly made a loud noise every time the rat approached him.

The Case of “Anna O.”

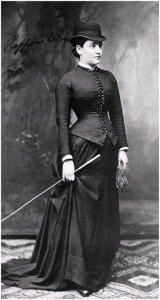

Sigmund Freud used the case of a young woman he called “Anna O.” to illustrate many principles of his theory of psychoanalysis (Freud, 1961) [8] . (Her real name was Bertha Pappenheim, and she was an early feminist who went on to make important contributions to the field of social work.) Anna had come to Freud’s colleague Josef Breuer around 1880 with a variety of odd physical and psychological symptoms. One of them was that for several weeks she was unable to drink any fluids. According to Freud,

She would take up the glass of water that she longed for, but as soon as it touched her lips she would push it away like someone suffering from hydrophobia.…She lived only on fruit, such as melons, etc., so as to lessen her tormenting thirst. (p. 9)

But according to Freud, a breakthrough came one day while Anna was under hypnosis.

[S]he grumbled about her English “lady-companion,” whom she did not care for, and went on to describe, with every sign of disgust, how she had once gone into this lady’s room and how her little dog—horrid creature!—had drunk out of a glass there. The patient had said nothing, as she had wanted to be polite. After giving further energetic expression to the anger she had held back, she asked for something to drink, drank a large quantity of water without any difficulty, and awoke from her hypnosis with the glass at her lips; and thereupon the disturbance vanished, never to return. (p.9)

Freud’s interpretation was that Anna had repressed the memory of this incident along with the emotion that it triggered and that this was what had caused her inability to drink. Furthermore, he believed that her recollection of the incident, along with her expression of the emotion she had repressed, caused the symptom to go away.

As an illustration of Freud’s theory, the case study of Anna O. is quite effective. As evidence for the theory, however, it is essentially worthless. The description provides no way of knowing whether Anna had really repressed the memory of the dog drinking from the glass, whether this repression had caused her inability to drink, or whether recalling this “trauma” relieved the symptom. It is also unclear from this case study how typical or atypical Anna’s experience was.

Case studies are useful because they provide a level of detailed analysis not found in many other research methods and greater insights may be gained from this more detailed analysis. As a result of the case study, the researcher may gain a sharpened understanding of what might become important to look at more extensively in future more controlled research. Case studies are also often the only way to study rare conditions because it may be impossible to find a large enough sample of individuals with the condition to use quantitative methods. Although at first glance a case study of a rare individual might seem to tell us little about ourselves, they often do provide insights into normal behavior. The case of HM provided important insights into the role of the hippocampus in memory consolidation.

However, it is important to note that while case studies can provide insights into certain areas and variables to study, and can be useful in helping develop theories, they should never be used as evidence for theories. In other words, case studies can be used as inspiration to formulate theories and hypotheses, but those hypotheses and theories then need to be formally tested using more rigorous quantitative methods. The reason case studies shouldn’t be used to provide support for theories is that they suffer from problems with both internal and external validity. Case studies lack the proper controls that true experiments contain. As such, they suffer from problems with internal validity, so they cannot be used to determine causation. For instance, during HM’s surgery, the surgeon may have accidentally lesioned another area of HM’s brain (a possibility suggested by the dissection of HM’s brain following his death) and that lesion may have contributed to his inability to consolidate new information. The fact is, with case studies we cannot rule out these sorts of alternative explanations. So, as with all observational methods, case studies do not permit determination of causation. In addition, because case studies are often of a single individual, and typically an abnormal individual, researchers cannot generalize their conclusions to other individuals. Recall that with most research designs there is a trade-off between internal and external validity. With case studies, however, there are problems with both internal validity and external validity. So there are limits both to the ability to determine causation and to generalize the results. A final limitation of case studies is that ample opportunity exists for the theoretical biases of the researcher to color or bias the case description. Indeed, there have been accusations that the woman who studied HM destroyed a lot of her data that were not published and she has been called into question for destroying contradictory data that didn’t support her theory about how memories are consolidated. There is a fascinating New York Times article that describes some of the controversies that ensued after HM’s death and analysis of his brain that can be found at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/07/magazine/the-brain-that-couldnt-remember.html?_r=0

Archival Research

Another approach that is often considered observational research involves analyzing archival data that have already been collected for some other purpose. An example is a study by Brett Pelham and his colleagues on “implicit egotism”—the tendency for people to prefer people, places, and things that are similar to themselves (Pelham, Carvallo, & Jones, 2005) [9] . In one study, they examined Social Security records to show that women with the names Virginia, Georgia, Louise, and Florence were especially likely to have moved to the states of Virginia, Georgia, Louisiana, and Florida, respectively.

As with naturalistic observation, measurement can be more or less straightforward when working with archival data. For example, counting the number of people named Virginia who live in various states based on Social Security records is relatively straightforward. But consider a study by Christopher Peterson and his colleagues on the relationship between optimism and health using data that had been collected many years before for a study on adult development (Peterson, Seligman, & Vaillant, 1988) [10] . In the 1940s, healthy male college students had completed an open-ended questionnaire about difficult wartime experiences. In the late 1980s, Peterson and his colleagues reviewed the men’s questionnaire responses to obtain a measure of explanatory style—their habitual ways of explaining bad events that happen to them. More pessimistic people tend to blame themselves and expect long-term negative consequences that affect many aspects of their lives, while more optimistic people tend to blame outside forces and expect limited negative consequences. To obtain a measure of explanatory style for each participant, the researchers used a procedure in which all negative events mentioned in the questionnaire responses, and any causal explanations for them were identified and written on index cards. These were given to a separate group of raters who rated each explanation in terms of three separate dimensions of optimism-pessimism. These ratings were then averaged to produce an explanatory style score for each participant. The researchers then assessed the statistical relationship between the men’s explanatory style as undergraduate students and archival measures of their health at approximately 60 years of age. The primary result was that the more optimistic the men were as undergraduate students, the healthier they were as older men. Pearson’s r was +.25.

This method is an example of content analysis —a family of systematic approaches to measurement using complex archival data. Just as structured observation requires specifying the behaviors of interest and then noting them as they occur, content analysis requires specifying keywords, phrases, or ideas and then finding all occurrences of them in the data. These occurrences can then be counted, timed (e.g., the amount of time devoted to entertainment topics on the nightly news show), or analyzed in a variety of other ways.

Media Attributions

- What happens when you remove the hippocampus? – Sam Kean by TED-Ed licensed under a standard YouTube License

- Pappenheim 1882 by unknown is in the Public Domain .

- Festinger, L., Riecken, H., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a modern group that predicted the destruction of the world. University of Minnesota Press. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

- Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301. ↵

- Levine, R. V., & Norenzayan, A. (1999). The pace of life in 31 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30 , 178–205. ↵

- Kraut, R. E., & Johnston, R. E. (1979). Social and emotional messages of smiling: An ethological approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 , 1539–1553. ↵

- Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An "experimental ethnography." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (5), 945-960. ↵

- Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 , 1–14. ↵

- Freud, S. (1961). Five lectures on psycho-analysis . New York, NY: Norton. ↵

- Pelham, B. W., Carvallo, M., & Jones, J. T. (2005). Implicit egotism. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 , 106–110. ↵

- Peterson, C., Seligman, M. E. P., & Vaillant, G. E. (1988). Pessimistic explanatory style is a risk factor for physical illness: A thirty-five year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55 , 23–27. ↵

Research that is non-experimental because it focuses on recording systemic observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything.

An observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs.

When researchers engage in naturalistic observation by making their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied.

Where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior.

Refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior.

In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, it is a type of reactivity when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would.

Researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying.

Researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

Researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation.

When a researcher makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation.

A part of structured observation whereby the observers use a clearly defined set of guidelines to "code" behaviors—assigning specific behaviors they are observing to a category—and count the number of times or the duration that the behavior occurs.

An in-depth examination of an individual.

A family of systematic approaches to measurement using qualitative methods to analyze complex archival data.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Effective Guidelines for Conducting Observation Research

Table of Contents

Have you ever wondered how psychologists gather authentic data about human behavior without influencing it? One key method they use is observation , a foundational approach that can yield deep insights when done correctly. In this post, we’ll walk through the essential guidelines for conducting effective observation research, ensuring that you can confidently plan, execute, and interpret your studies.

Understanding the Types of Observation

Before diving into data collection, it’s crucial to understand the different types of observation methods available. Each type serves a unique purpose and can affect the outcome of your study.

Structured vs. Unstructured Observation

Structured observation involves specific criteria and a systematic approach to recording behavior, while unstructured observation is more open-ended, allowing the observer to record all that occurs without a predetermined scheme.

Participant vs. Non-participant Observation

In participant observation, the researcher becomes a part of the group being observed, which can provide an inside view of the group’s dynamics. Non\-participant observation , on the other hand, requires the observer to remain detached from the group.

Covert vs. Overt Observation

When observers do not reveal their research intentions to the subjects, it is known as covert observation. This can help in capturing unaltered behavior but poses ethical questions. Overt observation is where the subjects are aware they are being observed, which can influence their behavior but is ethically transparent.

Preparing for Data Collection

Preparation is key to successful observation research. There are several steps you need to take before you begin collecting data.

Choosing the Right Setting and Subjects

Select a setting that is natural for the subjects and conducive to observing the behaviors of interest. The subjects should also be representative of the population you’re studying.

Developing the Observation Guide

Create an observation guide that details what behaviors or events are to be observed and recorded. This will ensure consistency and reliability in your data collection.

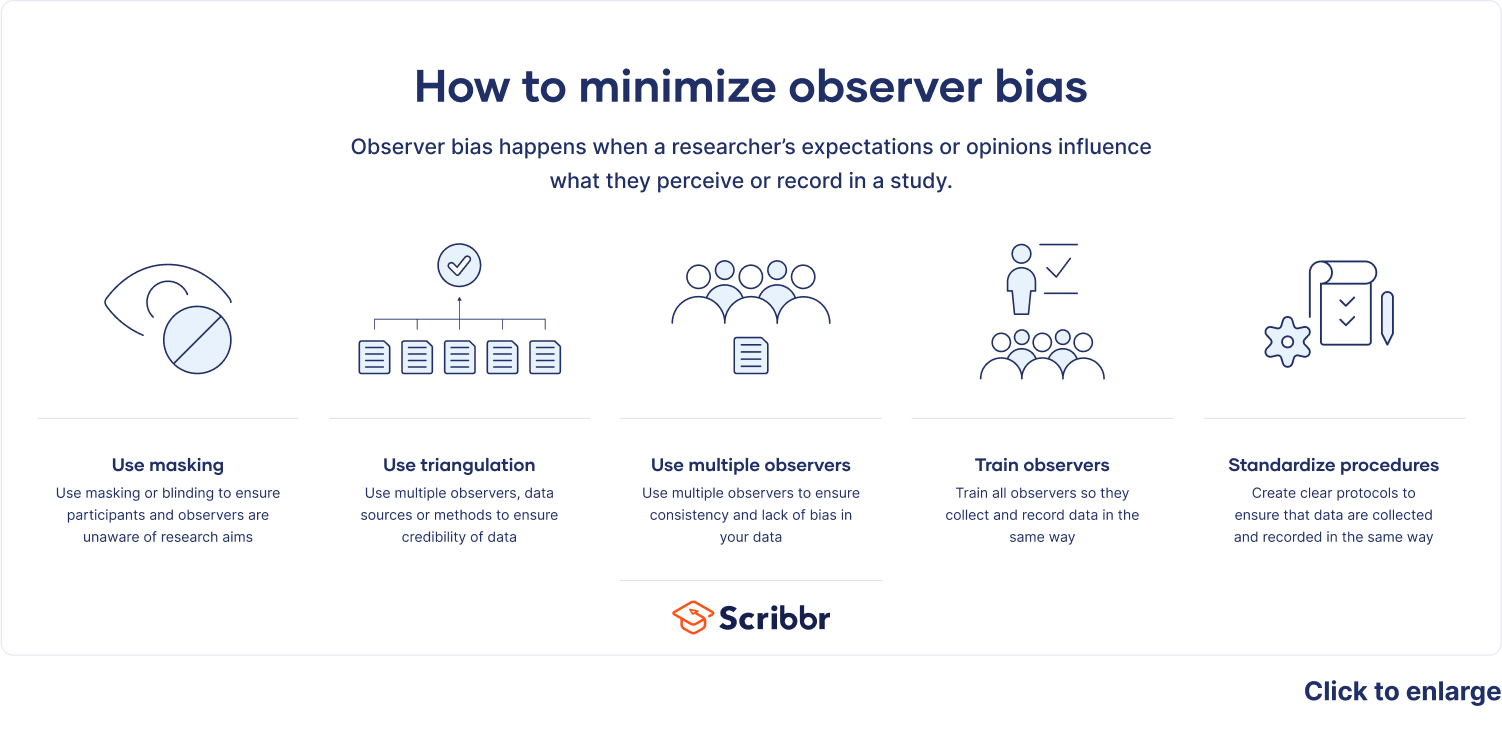

Training Observers

Ensure that all observers are thoroughly trained to use the observation guide and understand the nuances of the research. This reduces the risk of observer bias .

Executing the Observation Study

With preparation out of the way, it’s time to begin the actual observation. This phase is critical, as it’s where the data you’ll be analyzing is collected.

Recording Observations

Meticulous note-taking is a must. Use audio or video recording if possible, to capture details that might be missed in real-time.

Staying Unobtrusive

Whether you’re participating or not, staying unobtrusive helps in maintaining the integrity of the observed behaviors.

Being Ethical

Always adhere to ethical guidelines . If the observation is covert, ensure that it doesn’t intrude on privacy and is justified by the study’s potential benefits.

Analyzing and Interpreting Observational Data

Once you’ve gathered your data, the next step is to make sense of it. This phase is as important as the data collection itself.

Coding and Organizing Data

Develop a coding system to categorize the behaviors observed. This helps in organizing the data for analysis.

Identifying Patterns and Themes

Look for recurring behaviors or events that signify underlying patterns or themes in your data.

Maintaining Objectivity

It’s essential to remain objective during analysis. Avoid imposing your biases or expectations on the data.

Reporting Your Findings

Reporting your findings with clarity and honesty is the final step in the research process. Your report should be detailed enough to allow others to replicate the study if they wish.

Describing the Methodology

Detail the observation method used, the setting, and the subjects, so the context of the study is clear.

Presenting the Data

Present your data in a way that is both accessible and comprehensible, using visuals like charts or graphs where appropriate.

Discussing the Implications

Discuss what your findings mean in the broader context of the research question, and suggest areas for further study.

Observation research is a powerful method in psychology, allowing researchers to gather data in natural settings and gain insights that might otherwise be inaccessible. By following these guidelines, from choosing the right type of observation to effectively analyzing and reporting data, you can enhance the validity and reliability of your observational studies. It’s a meticulous process, but with careful planning and execution, your observations can lead to significant contributions in the field of psychology.

What do you think? How might the presence of an observer alter the behavior of the subjects, and how can this impact be minimized? Are there ethical considerations that might limit the use of observation research, and how should they be addressed? Share your thoughts and let’s delve into the complexities of observation research together.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

Research Methods in Psychology

1 Introduction to Psychological Research – Objectives and Goals, Problems, Hypothesis and Variables

- Nature of Psychological Research

- The Context of Discovery

- Context of Justification

- Characteristics of Psychological Research

- Goals and Objectives of Psychological Research

2 Introduction to Psychological Experiments and Tests

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Extraneous Variables

- Experimental and Control Groups

- Introduction of Test

- Types of Psychological Test

- Uses of Psychological Tests

3 Steps in Research

- Research Process

- Identification of the Problem

- Review of Literature

- Formulating a Hypothesis

- Identifying Manipulating and Controlling Variables

- Formulating a Research Design

- Constructing Devices for Observation and Measurement

- Sample Selection and Data Collection

- Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Hypothesis Testing

- Drawing Conclusion

4 Types of Research and Methods of Research

- Historical Research

- Descriptive Research

- Correlational Research

- Qualitative Research

- Ex-Post Facto Research

- True Experimental Research

- Quasi-Experimental Research

5 Definition and Description Research Design, Quality of Research Design

- Research Design

- Purpose of Research Design

- Design Selection

- Criteria of Research Design

- Qualities of Research Design

6 Experimental Design (Control Group Design and Two Factor Design)

- Experimental Design

- Control Group Design

- Two Factor Design

7 Survey Design

- Survey Research Designs

- Steps in Survey Design

- Structuring and Designing the Questionnaire

- Interviewing Methodology

- Data Analysis

- Final Report

8 Single Subject Design

- Single Subject Design: Definition and Meaning

- Phases Within Single Subject Design

- Requirements of Single Subject Design

- Characteristics of Single Subject Design

- Types of Single Subject Design

- Advantages of Single Subject Design

- Disadvantages of Single Subject Design

9 Observation Method

- Definition and Meaning of Observation

- Characteristics of Observation

- Types of Observation

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Observation

- Guides for Observation Method

10 Interview and Interviewing

- Definition of Interview

- Types of Interview

- Aspects of Qualitative Research Interviews

- Interview Questions

- Convergent Interviewing as Action Research

- Research Team

11 Questionnaire Method

- Definition and Description of Questionnaires

- Types of Questionnaires

- Purpose of Questionnaire Studies

- Designing Research Questionnaires

- The Methods to Make a Questionnaire Efficient

- The Types of Questionnaire to be Included in the Questionnaire

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaire

- When to Use a Questionnaire?

12 Case Study

- Definition and Description of Case Study Method

- Historical Account of Case Study Method

- Designing Case Study

- Requirements for Case Studies

- Guideline to Follow in Case Study Method

- Other Important Measures in Case Study Method

- Case Reports

13 Report Writing

- Purpose of a Report

- Writing Style of the Report

- Report Writing – the Do’s and the Don’ts

- Format for Report in Psychology Area

- Major Sections in a Report

14 Review of Literature

- Purposes of Review of Literature

- Sources of Review of Literature

- Types of Literature

- Writing Process of the Review of Literature

- Preparation of Index Card for Reviewing and Abstracting

15 Methodology

- Definition and Purpose of Methodology

- Participants (Sample)

- Apparatus and Materials

16 Result, Analysis and Discussion of the Data

- Definition and Description of Results

- Statistical Presentation

- Tables and Figures

17 Summary and Conclusion

- Summary Definition and Description

- Guidelines for Writing a Summary

- Writing the Summary and Choosing Words

- A Process for Paraphrasing and Summarising

- Summary of a Report

- Writing Conclusions

18 References in Research Report

- Reference List (the Format)

- References (Process of Writing)

- Reference List and Print Sources

- Electronic Sources

- Book on CD Tape and Movie

- Reference Specifications

- General Guidelines to Write References

Share on Mastodon

Observational Method

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 02 February 2024

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Wang Jisheng 2 &

- Zhang Kan 2

Observational method is the basic research method of psychology that determines the psychological characteristics of an observed person by purposefully and systematically observing and recording his or her speech and behavior. Observational method has long been adopted by people. Confucius said, “It used to be that with people, when I heard what they said I trusted their conduct would match; now I listen to what they say and observe their conduct.” (The Analects of Confucius · Gongye Chang). It is referring to the use of observational method to know people. After psychology became an independent discipline, the observational method has also developed greatly.

The greatest feature of the observational method is the direct observation and recording of the mental and behavioral activities of the observed person in natural or simulated situations. The raw data collected by observational method need to be classified, coded, frequency statistics counted, and qualitative statistics analyzed...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Further Reading

Kantowitz BH, Roediger HL, Elmes DG (2015) Experimental psychology, 10th edn. Cengage Learning, Boston

Google Scholar

Zhang X-M (2014) Shu Hua. Beijing Normal University Publishing Group, Experimental Psychology. Beijing

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Beijing, China

Wang Jisheng & Zhang Kan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Zhang Kan .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 Encyclopedia of China Publishing House

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Jisheng, W., Kan, Z. (2024). Observational Method. In: The ECPH Encyclopedia of Psychology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6000-2_476-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6000-2_476-1

Received : 04 January 2024

Accepted : 05 January 2024

Published : 02 February 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-6000-2

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-6000-2

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Privacy Policy

Home » Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Table of Contents

Observational Research

Definition:

Observational research is a type of research method where the researcher observes and records the behavior of individuals or groups in their natural environment. In other words, the researcher does not intervene or manipulate any variables but simply observes and describes what is happening.

Observation

Observation is the process of collecting and recording data by observing and noting events, behaviors, or phenomena in a systematic and objective manner. It is a fundamental method used in research, scientific inquiry, and everyday life to gain an understanding of the world around us.

Types of Observational Research

Observational research can be categorized into different types based on the level of control and the degree of involvement of the researcher in the study. Some of the common types of observational research are:

Naturalistic Observation

In naturalistic observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of individuals or groups in their natural environment without any interference or manipulation of variables.

Controlled Observation

In controlled observation, the researcher controls the environment in which the observation is taking place. This type of observation is often used in laboratory settings.

Participant Observation

In participant observation, the researcher becomes an active participant in the group or situation being observed. The researcher may interact with the individuals being observed and gather data on their behavior, attitudes, and experiences.

Structured Observation

In structured observation, the researcher defines a set of behaviors or events to be observed and records their occurrence.

Unstructured Observation

In unstructured observation, the researcher observes and records any behaviors or events that occur without predetermined categories.

Cross-Sectional Observation

In cross-sectional observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of different individuals or groups at a single point in time.

Longitudinal Observation

In longitudinal observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of the same individuals or groups over an extended period of time.

Data Collection Methods

Observational research uses various data collection methods to gather information about the behaviors and experiences of individuals or groups being observed. Some common data collection methods used in observational research include:

Field Notes

This method involves recording detailed notes of the observed behavior, events, and interactions. These notes are usually written in real-time during the observation process.

Audio and Video Recordings

Audio and video recordings can be used to capture the observed behavior and interactions. These recordings can be later analyzed to extract relevant information.

Surveys and Questionnaires

Surveys and questionnaires can be used to gather additional information from the individuals or groups being observed. This method can be used to validate or supplement the observational data.

Time Sampling

This method involves taking a snapshot of the observed behavior at pre-determined time intervals. This method helps to identify the frequency and duration of the observed behavior.

Event Sampling

This method involves recording specific events or behaviors that are of interest to the researcher. This method helps to provide detailed information about specific behaviors or events.

Checklists and Rating Scales

Checklists and rating scales can be used to record the occurrence and frequency of specific behaviors or events. This method helps to simplify and standardize the data collection process.

Observational Data Analysis Methods

Observational Data Analysis Methods are:

Descriptive Statistics

This method involves using statistical techniques such as frequency distributions, means, and standard deviations to summarize the observed behaviors, events, or interactions.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis involves identifying patterns and themes in the observed behaviors or interactions. This analysis can be done manually or with the help of software tools.

Content Analysis

Content analysis involves categorizing and counting the occurrences of specific behaviors or events. This analysis can be done manually or with the help of software tools.

Time-series Analysis

Time-series analysis involves analyzing the changes in behavior or interactions over time. This analysis can help identify trends and patterns in the observed data.

Inter-observer Reliability Analysis

Inter-observer reliability analysis involves comparing the observations made by multiple observers to ensure the consistency and reliability of the data.

Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate analysis involves analyzing multiple variables simultaneously to identify the relationships between the observed behaviors, events, or interactions.

Event Coding

This method involves coding observed behaviors or events into specific categories and then analyzing the frequency and duration of each category.

Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis involves grouping similar behaviors or events into clusters based on their characteristics or patterns.

Latent Class Analysis

Latent class analysis involves identifying subgroups of individuals or groups based on their observed behaviors or interactions.

Social network Analysis

Social network analysis involves mapping the social relationships and interactions between individuals or groups based on their observed behaviors.

The choice of data analysis method depends on the research question, the type of data collected, and the available resources. Researchers should choose the appropriate method that best fits their research question and objectives. It is also important to ensure the validity and reliability of the data analysis by using appropriate statistical tests and measures.

Applications of Observational Research

Observational research is a versatile research method that can be used in a variety of fields to explore and understand human behavior, attitudes, and preferences. Here are some common applications of observational research:

- Psychology : Observational research is commonly used in psychology to study human behavior in natural settings. This can include observing children at play to understand their social development or observing people’s reactions to stress to better understand how stress affects behavior.

- Marketing : Observational research is used in marketing to understand consumer behavior and preferences. This can include observing shoppers in stores to understand how they make purchase decisions or observing how people interact with advertisements to determine their effectiveness.

- Education : Observational research is used in education to study teaching and learning in natural settings. This can include observing classrooms to understand how teachers interact with students or observing students to understand how they learn.

- Anthropology : Observational research is commonly used in anthropology to understand cultural practices and beliefs. This can include observing people’s daily routines to understand their culture or observing rituals and ceremonies to better understand their significance.

- Healthcare : Observational research is used in healthcare to understand patient behavior and preferences. This can include observing patients in hospitals to understand how they interact with healthcare professionals or observing patients with chronic illnesses to better understand their daily routines and needs.

- Sociology : Observational research is used in sociology to understand social interactions and relationships. This can include observing people in public spaces to understand how they interact with others or observing groups to understand how they function.

- Ecology : Observational research is used in ecology to understand the behavior and interactions of animals and plants in their natural habitats. This can include observing animal behavior to understand their social structures or observing plant growth to understand their response to environmental factors.

- Criminology : Observational research is used in criminology to understand criminal behavior and the factors that contribute to it. This can include observing criminal activity in a particular area to identify patterns or observing the behavior of inmates to understand their experience in the criminal justice system.

Observational Research Examples

Here are some real-time observational research examples:

- A researcher observes and records the behaviors of a group of children on a playground to study their social interactions and play patterns.

- A researcher observes the buying behaviors of customers in a retail store to study the impact of store layout and product placement on purchase decisions.

- A researcher observes the behavior of drivers at a busy intersection to study the effectiveness of traffic signs and signals.

- A researcher observes the behavior of patients in a hospital to study the impact of staff communication and interaction on patient satisfaction and recovery.

- A researcher observes the behavior of employees in a workplace to study the impact of the work environment on productivity and job satisfaction.

- A researcher observes the behavior of shoppers in a mall to study the impact of music and lighting on consumer behavior.

- A researcher observes the behavior of animals in their natural habitat to study their social and feeding behaviors.

- A researcher observes the behavior of students in a classroom to study the effectiveness of teaching methods and student engagement.

- A researcher observes the behavior of pedestrians and cyclists on a city street to study the impact of infrastructure and traffic regulations on safety.

How to Conduct Observational Research

Here are some general steps for conducting Observational Research:

- Define the Research Question: Determine the research question and objectives to guide the observational research study. The research question should be specific, clear, and relevant to the area of study.

- Choose the appropriate observational method: Choose the appropriate observational method based on the research question, the type of data required, and the available resources.

- Plan the observation: Plan the observation by selecting the observation location, duration, and sampling technique. Identify the population or sample to be observed and the characteristics to be recorded.

- Train observers: Train the observers on the observational method, data collection tools, and techniques. Ensure that the observers understand the research question and objectives and can accurately record the observed behaviors or events.

- Conduct the observation : Conduct the observation by recording the observed behaviors or events using the data collection tools and techniques. Ensure that the observation is conducted in a consistent and unbiased manner.

- Analyze the data: Analyze the observed data using appropriate data analysis methods such as descriptive statistics, qualitative analysis, or content analysis. Validate the data by checking the inter-observer reliability and conducting statistical tests.

- Interpret the results: Interpret the results by answering the research question and objectives. Identify the patterns, trends, or relationships in the observed data and draw conclusions based on the analysis.

- Report the findings: Report the findings in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate visual aids and tables. Discuss the implications of the results and the limitations of the study.

When to use Observational Research

Here are some situations where observational research can be useful:

- Exploratory Research: Observational research can be used in exploratory studies to gain insights into new phenomena or areas of interest.

- Hypothesis Generation: Observational research can be used to generate hypotheses about the relationships between variables, which can be tested using experimental research.

- Naturalistic Settings: Observational research is useful in naturalistic settings where it is difficult or unethical to manipulate the environment or variables.

- Human Behavior: Observational research is useful in studying human behavior, such as social interactions, decision-making, and communication patterns.

- Animal Behavior: Observational research is useful in studying animal behavior in their natural habitats, such as social and feeding behaviors.

- Longitudinal Studies: Observational research can be used in longitudinal studies to observe changes in behavior over time.

- Ethical Considerations: Observational research can be used in situations where manipulating the environment or variables would be unethical or impractical.

Purpose of Observational Research

Observational research is a method of collecting and analyzing data by observing individuals or phenomena in their natural settings, without manipulating them in any way. The purpose of observational research is to gain insights into human behavior, attitudes, and preferences, as well as to identify patterns, trends, and relationships that may exist between variables.

The primary purpose of observational research is to generate hypotheses that can be tested through more rigorous experimental methods. By observing behavior and identifying patterns, researchers can develop a better understanding of the factors that influence human behavior, and use this knowledge to design experiments that test specific hypotheses.

Observational research is also used to generate descriptive data about a population or phenomenon. For example, an observational study of shoppers in a grocery store might reveal that women are more likely than men to buy organic produce. This type of information can be useful for marketers or policy-makers who want to understand consumer preferences and behavior.

In addition, observational research can be used to monitor changes over time. By observing behavior at different points in time, researchers can identify trends and changes that may be indicative of broader social or cultural shifts.

Overall, the purpose of observational research is to provide insights into human behavior and to generate hypotheses that can be tested through further research.

Advantages of Observational Research

There are several advantages to using observational research in different fields, including:

- Naturalistic observation: Observational research allows researchers to observe behavior in a naturalistic setting, which means that people are observed in their natural environment without the constraints of a laboratory. This helps to ensure that the behavior observed is more representative of the real-world situation.

- Unobtrusive : Observational research is often unobtrusive, which means that the researcher does not interfere with the behavior being observed. This can reduce the likelihood of the research being affected by the observer’s presence or the Hawthorne effect, where people modify their behavior when they know they are being observed.

- Cost-effective : Observational research can be less expensive than other research methods, such as experiments or surveys. Researchers do not need to recruit participants or pay for expensive equipment, making it a more cost-effective research method.

- Flexibility: Observational research is a flexible research method that can be used in a variety of settings and for a range of research questions. Observational research can be used to generate hypotheses, to collect data on behavior, or to monitor changes over time.

- Rich data : Observational research provides rich data that can be analyzed to identify patterns and relationships between variables. It can also provide context for behaviors, helping to explain why people behave in a certain way.

- Validity : Observational research can provide high levels of validity, meaning that the results accurately reflect the behavior being studied. This is because the behavior is being observed in a natural setting without interference from the researcher.

Disadvantages of Observational Research

While observational research has many advantages, it also has some limitations and disadvantages. Here are some of the disadvantages of observational research:

- Observer bias: Observational research is prone to observer bias, which is when the observer’s own beliefs and assumptions affect the way they interpret and record behavior. This can lead to inaccurate or unreliable data.

- Limited generalizability: The behavior observed in a specific setting may not be representative of the behavior in other settings. This can limit the generalizability of the findings from observational research.

- Difficulty in establishing causality: Observational research is often correlational, which means that it identifies relationships between variables but does not establish causality. This can make it difficult to determine if a particular behavior is causing an outcome or if the relationship is due to other factors.

- Ethical concerns: Observational research can raise ethical concerns if the participants being observed are unaware that they are being observed or if the observations invade their privacy.

- Time-consuming: Observational research can be time-consuming, especially if the behavior being observed is infrequent or occurs over a long period of time. This can make it difficult to collect enough data to draw valid conclusions.

- Difficulty in measuring internal processes: Observational research may not be effective in measuring internal processes, such as thoughts, feelings, and attitudes. This can limit the ability to understand the reasons behind behavior.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Triangulation in Research – Types, Methods and...

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Ethnographic Research -Types, Methods and Guide

Qualitative Research Methods

Textual Analysis – Types, Examples and Guide

Learn More Psychology

- Psychology Issues

Observational Psychology

Introduction to observational psychology with an overview of bandura's social learning theory, modern issues in observational psychology and an evaluation of the approach..

Permalink Print |

- Behavioral Psychology

- Biological Psychology

- Body Language Interpretation

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Dream Interpretation

- Freudian Psychology

- Memory & Memory Techniques

- Role Playing: Stanford Prison Experiment

- Authoritarian Personality

- Memory: Levels of Processing

- Cold Reading: Psychology of Fortune Telling

- Stages of Sleep

- Personality Psychology

- Why Do We Forget?

- Psychology of Influence

- Stress in Psychology

- Body Language: How to Spot a Liar

- Be a Better Communicator

- Eye Reading: Body Language

- Motivation: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

- How to Interpret your Dreams Guide

- How to Remember Your Dreams

- Interpreting Your Dreams

- Superstition in Pigeons

- Altruism in Animals and Humans

- Stimulus-Response Theory

- Conditioned Behavior

- Synesthesia: Mixing the Senses

- Freudian Personality Type Test

- ... and much more

- Unlimited access to analysis of groundbreaking research and studies

- 17+ psychology guides : develop your understanding of the mind

- Self Help Audio : MP3 sessions to stream or download

Best Digital Psychology Magazine - UK

Best online psychology theory resource.

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory . New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1977.

Which Archetype Are You?

Are You Angry?

Windows to the Soul

Are You Stressed?

Attachment & Relationships

Memory Like A Goldfish?

31 Defense Mechanisms

Slave To Your Role?

Are You Fixated?

Interpret Your Dreams

How to Read Body Language

How to Beat Stress and Succeed in Exams

Psychology Topics

Learn psychology.

- Access 2,200+ insightful pages of psychology explanations & theories

- Insights into the way we think and behave

- Body Language & Dream Interpretation guides

- Self hypnosis MP3 downloads and more

- Behavioral Approach

- Eye Reading

- Stress Test

- Cognitive Approach

- Fight-or-Flight Response

- Neuroticism Test

© 2024 Psychologist World. Home About Contact Us Terms of Use Privacy & Cookies Hypnosis Scripts Sign Up

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Naturalistic Observation?

Illustration by Brianna Gilmartin, Verywell

- How Naturalistic Observation Works

- Pros and Cons

- Data Collection Methods

How Often Is Data Collected?

Naturalistic observation is a research method that involves observing subjects in their natural environment. This approach is often used by psychologists and other social scientists. It is a form of qualitative research , which focuses on collecting, evaluating, and describing non-numerical data.

It can be useful if conducting lab research would be unrealistic, cost-prohibitive, or would unduly affect the subject's behavior. The goal of naturalistic observation is to observe behavior as it occurs in a natural setting without interference or attempts to manipulate variables.

This article discusses how naturalistic observation works and the pros and cons of doing this type of research. It also covers how data is collected and examples of when this method might be used in psychology research.

How Does Naturalistic Observation Work?

People do not necessarily behave in a lab setting the way they would in a natural environment. Researchers sometimes want to observe their subject's behavior as it happens ("in the wild," so to speak). Psychologists can get a better idea of how and why people react the way that they do by watching how they respond to situations and stimuli in real life.

Naturalistic observation is different than structured observation because it involves looking at a subject's behavior as it occurs in a natural setting, with no attempts at intervention on the part of the researcher.

For example, a researcher interested in aspects of classroom behavior (such as the interactions between students or teacher-student dynamics) might use naturalistic observation as part of their research.

Performing these observations in a lab would be difficult because it would involve recreating a classroom environment. This would likely influence the behavior of the participants, making it difficult to generalize the observations made.

By observing the subjects in their natural setting (the classroom where they work and learn), the researchers can more fully observe the behavior they are interested in as it occurs in the real world.

Naturalistic Observation Pros and Cons

Like other research methods, naturalistic observation has advantages and disadvantages.

More realistic

More affordable

Can detect patterns

Inability to manipulate or control variables

Cannot explain why behaviors happen

Risk of observer bias

An advantage of naturalistic observation is that it allows the investigators to directly observe the subject in a natural setting. The method gives scientists a first-hand look at social behavior and can help them notice things that they might never have encountered in a lab setting.

The observations can also serve as inspiration for further investigations. The information gleaned from naturalistic observation can lead to insights that can be used to help people overcome problems and lead to healthier, happier lives.

Other advantages of naturalistic observation include:

- Allows researchers to study behaviors or situations that cannot be manipulated in a lab due to ethical concerns . For example, it would be unethical to study the effects of imprisonment by actually confining subjects. But researchers can gather information by using naturalistic observation in actual prison settings.

- Can support the external validity of research . Researchers might believe that the findings of a lab study can be generalized to a larger population, but that does not mean they would actually observe those findings in a natural setting. They may conduct naturalistic observation to make that confirmation.

Naturalistic observation can be useful in many cases, but the method also has some downsides. Some of these include:

- Inability to draw cause-and-effect conclusions : The biggest disadvantage of naturalistic observation is that determining the exact cause of a subject's behavior can be difficult.

- Lack of control : Another downside is that the experimenter cannot control for outside variables .

- Lack of validity : While the goal of naturalistic observation is to get a better idea of how it occurs in the real world, experimental effects can still influence how people respond. The Hawthorne effect and other demand characteristics can play a role in people altering their behavior simply because they know they are being observed.

- Observer bias : The biases of the people observing the natural behaviors can influence the interpretations that experimenters make.

It is also important to note that naturalistic observation is a type of correlational research (others include surveys and archival research). A correlational study is a non-experimental approach that seeks to find statistical relationships between variables. Naturalistic observation is one method that can be used to collect data for correlational studies.

While such methods can look at the direction or strength of a relationship between two variables, they cannot determine if one causes the other. As the saying goes, correlation does not imply causation.

Data Collection Methods

Researchers use different techniques to collect and record data from naturalistic observation. For example, they might write down how many times a certain behavior occurred in a specific period of time or take a video recording of subjects.

- Audio or video recordings : Depending on the type of behavior being observed, the researchers might also decide to make audio or videotaped recordings of each observation session. They can then later review the recordings.

- Observer narrative : The observer might take notes during the session that they can refer back to. They can collect data and discern behavior patterns from these notes.

- Tally counts : The observer writes down when and how many times certain behaviors occurred.

It is rarely practical—or even possible—to observe every moment of a subject's life. Therefore, researchers often use sampling to gather information through naturalistic observation.

The goal is to make sure that the sample of data is representative of the subject's overall behavior. A representative sample is a selection that accurately depicts the characteristics that are present in the total subject of interest. A representative sample can be obtained through:

- Time sampling : This involves taking samples at different intervals of time (random or systematic). For example, a researcher might observe a person in the workplace to notice how frequently they engage in certain behaviors and to determine if there are patterns or trends.

- Situation sampling : This type of sampling involves observing behavior in different situations and settings. An example of this would be observing a child in a classroom, home, and community setting to determine if certain behaviors only occur in certain settings.

- Event sampling : This approach involves observing and recording each time an event happens. This allows the researchers to better identify patterns that might be present. For example, a researcher might note every time a subject becomes agitated. By noting the event and what was occurring around the time of each event, researchers can draw inferences about what might be triggering those behaviors.

Examples of Naturalistic Observation

Imagine that you want to study risk-taking behavior in teenagers. You might choose to observe behavior in different settings, such as a sledding hill, a rock-climbing wall, an ice-skating rink, and a bumper car ride. After you operationally define "risk-taking behavior," you would observe your teen subjects in these settings and record every incidence of what you have defined as risky behavior.

Famous examples of naturalistic observations include Charles Darwin's journey aboard the HMS Beagle , which served as the basis for his theory of natural selection, and Jane Goodall's work studying the behavior of chimpanzees in their natural habitat.

Naturalistic observation can play an important role in the research process. It offers a number of advantages, including often being more affordable and less intrusive than other types of research.

In some cases, researchers may utilize naturalistic observation as a way to learn more about something that is happening in a certain population. Using this information, they can then formulate a hypothesis that can be tested further.

Mehl MR, Robbins ML, Deters FG. Naturalistic observation of health-relevant social processes: the electronically activated recorder methodology in psychosomatics . Psychosom Med. 2012;74(4):410-7. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182545470

U.S. National Library of Medicine. Rewriting the book of nature - Darwin and the Beagle voyage .

Angrosino MV. Naturalistic Observation . Left Coast Press.

DiMercurio A, Connell JP, Clark M, Corbetta D. A naturalistic observation of spontaneous touches to the body and environment in the first 2 months of life . Front Psychol . 2018;9:2613. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02613

Pierce K, Pepler D. A peek behind the fence: observational methods 25 years later . In: Smith PK, Norman JO, eds. The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Bullying. 1st ed . Wiley; 2021:215-232. doi:10.1002/9781118482650.ch12

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Aust Prescr

- v.41(3); 2018 Jun

Observational studies and their utility for practice

Julia fm gilmartin-thomas.

2 Research Department of Practice and Policy, University College London, School of Pharmacy, London

1 Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne

Ingrid Hopper

Randomised controlled clinical trials are the best source of evidence for assessing the efficacy of drugs. Observational studies provide critical descriptive data and information on long-term efficacy and safety that clinical trials cannot provide, at generally much less expense.